Abstract

Background

In England routine vaccinations are recorded in either the patients General Practice record or in series of sub-national vaccine registers that are not interoperable. During the COVID-19 pandemic it was established that COVID vaccines would need to be delivered in multiple settings where current vaccine registers do not exist. We describe how a national vaccine register was created to collect data on COVID-19 vaccines.

Methods

The National Immunisation Management System (NIMS) was developed by a range of health and digital government agencies. Vaccinations delivered are entered on an application which is verified by individual National Health Service number in a centralised system. UKHSA receive a feed of this data to use for monitoring vaccine coverage, effectiveness, and safety.

To validate the vaccination data, we compared vaccine records to self-reported vaccination dose, manufacturer, and vaccination date from the enhanced surveillance system from 11 February 2021 to 24 August 2021.

Results

With the Implementation of NIMS, we have been able to successfully record COVID-19 vaccinations delivered in multiple settings.

Of 1,129 individuals, 97.8% were recorded in NIMS as unvaccinated compared to those who self-reported as unvaccinated. One hundred percent and 99.3% of individuals recorded in NIMS as having at least one dose and two doses of the COVID-19 vaccine were also self-reported as having at least one and two doses, respectively. Of the 100% reporting at least one dose, 98.3% self-reported the same vaccination date as NIMS. A total of 98.8% and 99.3% had the same manufacturer information for their first dose and second dose as that which was self-reported, respectively.

Discussion

Daily access to individual-level vaccine data from NIMS has allowed UKHSA to estimate vaccine coverage and provide some of the world’s first vaccine effectiveness estimates rapidly and accurately.

Keywords: Vaccine registry, Vaccine(s), COVID-19, Vaccine uptake, Vaccine coverage, Immunisation(s)

1. Introduction

Monitoring the rollout and delivery of vaccine programmes is essential to ensure their success and maximise population protection against vaccine-preventable diseases [1], [2]. The United Kingdom (UK) was among the world’s first countries to rollout a COVID-19 immunisation programme and has learnt many lessons applicable to other countries.

In England, routine vaccinations delivered to adults are recorded in the patients General Practice (GP) record. Vaccines delivered to children under 19 years are also recorded in Child Health Information Systems (CHIS), a series of sub-national vaccine registers [3], [4]. Monitoring vaccination data relies on correct coding at the GP level and, for vaccines delivered in non-practice settings (for example, in pharmacies, schools, maternity units), being appropriately coded and transferred to the GP record. Research shows that national vaccine registers are key to monitoring vaccination programmes [1]. The National Immunisations Management System (NIMS) was commissioned by the NHS to improve data flows for the national influenza programme, in which vaccines are delivered across settings including schools, pharmacies, hospitals and in GPs. However, the urgency and scale of the COVID-19 vaccination programme (the largest immunisation programme in British history) made clear vaccines would need to be delivered in multiple settings, including hospitals, GPs, pharmacies, mobile vaccination units (e.g. for delivery in care homes), and mass immunisation sites. A national vaccine register (also known as an immunisation information system) would need to be created rapidly to allow information on vaccinated individuals to be recorded in as close to real time as possible. Vaccination data would need to be retuned in a complete and accurate manner to monitor the rollout of the programme by producing vaccine coverage data, assess vaccine effectiveness, and provide vaccination details in the event of adverse reactions. Consequently, NIMS was built by several health and digital government agencies [5], [6] which includes advice from clinicians, would be used to record COVID-19 vaccinations. Since autumn 2020 NIMS has been used to collect vaccination information at the individual level in a centralised system for the management of both seasonal influenza and COVID-19 vaccinations across England.

This paper describes the use of NIMS at UKHSA and how it is processed and used to estimate vaccine coverage and monitor vaccine effectiveness and safety in England. This paper also discussed the initial validations of NIMS data using questionnaire data used for enhanced surveillance purposes.

2. Methods

2.1. Nims

NIMS has multiple functions including identifying priority groups eligible for COVID-19 vaccines, sending invitations and reminders for vaccination appointments, monitoring those invited for a vaccination, and recording vaccination data [7]. Point of care applications (PoC apps) available and standardised for vaccination settings to collect vaccination details on individuals who have presented to a vaccination site (e.g. GP, pharmacy, hospital provider, or mass immunisation site) to receive a COVID-19 vaccine. Certain sites such as hospitals have commissioned their own specific PoC apps to be used to collect data on vaccination. Several data items are mandatory to enter in the PoC app, such as the unique patient identifier NHS number, date of vaccination and batch number. Data from the NHS Spine (a centralised IT infrastructure allowing NHS services to exchange information across local and national NHS teams) for every-one resident and registered with a GP in England is used to ensure completeness and accuracy of individual’s information when entering vaccination details [8]. Individuals not registered with a GP practice in England and that do not have an NHS number will be allocated a number upon receiving their vaccine.

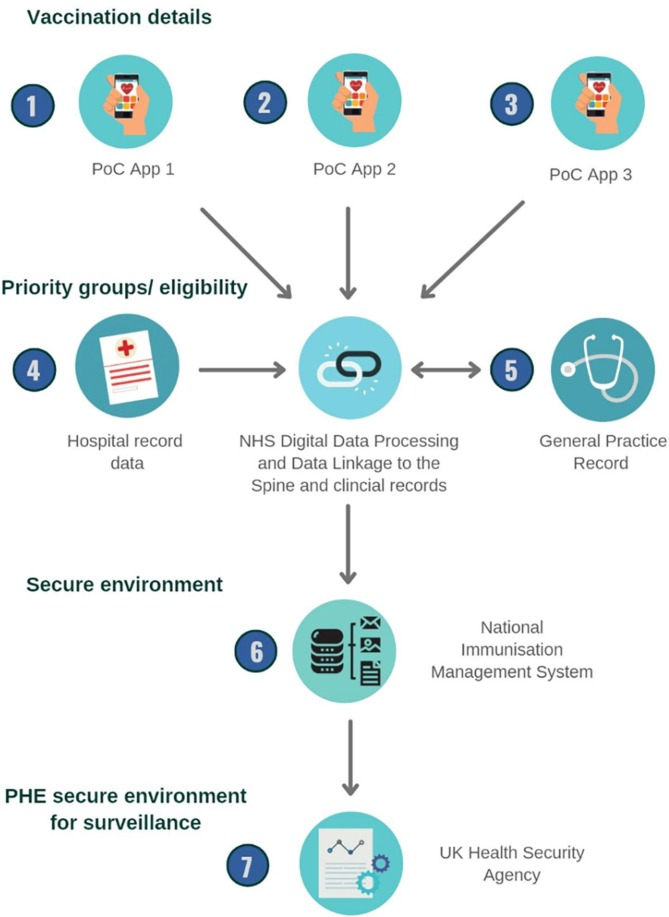

NHS Digital, England’s Digital Health Agency, validate and link the data from GP and hospital records to identify individuals belonging to different cohort groups, such as the clinically extremely vulnerable and pregnant women. NHS Digital then send this data through to NIMS and to the individual’s GP record. The UK Health Protection Agency (UKHSA), formally known as Public Health England, receives these data daily from NIMS in a secure Microsoft Azure cloud environment which is then stored in a SQL database (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Data flows for Vaccination Details from vaccine administration to Public Health England (Diagram created on Canva).

The data from NIMS is provided to UKHSA in two files;

-

a.

A population denominator file of all persons that have an NHS number with accompanying demographic details, including ethnicity as defined in the 2001 census [9]. Individuals that are clinically extremely vulnerable are flagged based on information from their clinical record, and healthcare and social care workers are flagged based on NHS Electronic Staff Records.

-

b.

A vaccination events file of all persons that have had a minimum of one COVID-19 vaccine recorded with accompanying details of the vaccination event, including location of where the vaccine was delivered, date the vaccine was administered, manufacturer information and vaccine batch number.

2.2. UKHSA NIMS feed

UKHSA imports a daily feed of data into a SQL Server using automated SQL Server Integration Services (SSIS) jobs and stored procedures developed by UKHSA scientists, developers, database engineers and database administrators. Data cleaning and assurance is carried out in the staging area prior to the data being available to end users. UKHSA deduplicates records, processes actions on adding, updating, or deleting data, and validates the NHS numbers using an NHS number check digit and assesses the data for any anomalies. Individuals must have a valid NHS number to be linked to the individual file with the persons demographics. There are processes in place within NHS for individuals who are not registered with a GP and do not have an NHS number to be allocated an NHS number so that unregistered people can access vaccination.

UKHSA set rules for processing the data and derive a series of variables depending on the purpose the data is being used for. Vaccination details such as the dosing information and vaccination manufacturer are provided in Systematised Nomenclature of Medicine Clinical Terms (SNOMED CT) [10]. Vaccine batch numbers are either scanned (using a barcode scanner) or manually entered in the PoC apps. UKHSA undertakes initial data cleaning of batch numbers, and then assign the vaccine manufacturer to individual records using SNOMED CT codes and batch numbers.

Records are then linked to individual postcodes from the GP record to allocate the region each individual resides in, the 2011 ONS rural/urban classification, and the 2019 Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) decile [11]. NHS numbers are used to link to additional datasets such as care home resident lists (maintained by NHS England and provided monthly), COVID-19 community level testing data, and COVID-19 related hospitalisations and deaths [12].

For vaccine coverage purposes, individuals that received a second dose of the vaccine less than 20 days after their first dose are considered as not having a complete course of the COVID-19 vaccine, and only their first dose is used. For vaccine effectiveness and vaccine safety purposes all doses recorded in the NIMS are retained. Individuals recorded as both having been vaccinated and having refused/declined a vaccine were not recorded as having a vaccine as it is not possible to guarantee that the vaccine has been administered.

2.3. Data validation

As part of UKHSA’s role to monitor the COVID-19 pandemic, a case-based enhanced surveillance system was set in place to follow-up vaccine eligible individuals who have had a PCR test for SARS-CoV-2. A questionnaire is administered by nurses over the phone to a random selection of individuals in England and asks for their vaccination details. This study protocol has been published online [13]. We compared the self-reported vaccination dose, manufacturer and vaccination date from the enhanced surveillance system to NIMS data for patients recruited from 11 February 2021 to 24 August 2021.

3. Results

Without the introduction of NIMS, it would have not been possible to rapidly collect individual level data on vaccination uptake in near real time. The daily processing and validation of the data allowed for rapid analyses on vaccine coverage, vaccine effectiveness and safety.

When comparing the UKHSA feed of NIMS to the enhanced surveillance questionnaire, a total of 1,129 individuals had responded to the enhanced surveillance questionnaire by 24 August 2021. Of these individuals, a total of 309 of 316 (97.8 %) of individuals were recorded in NIMS as unvaccinated compared to those who self-reported as unvaccinated. A total of 813 of 813 (100.0 %) of individuals were recorded in NIMS as having at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine compared to those who self-reported as having one dose, of which 297 of 299 (99.3 %) of individuals were recorded in NIMS as having two doses of COVID-19 vaccine compared to those who self-reported having two doses.

Of the 813 people who were recorded in NIMS as having at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, 803/813 (98.8 %) had the same manufacturer information for their first dose as that which was self-reported in the enhanced surveillance questionnaire while 297/299 (99.3 %) people who were recorded in NIMS as having had two doses of the COVID-19 vaccine self-reported the same manufacturer information.

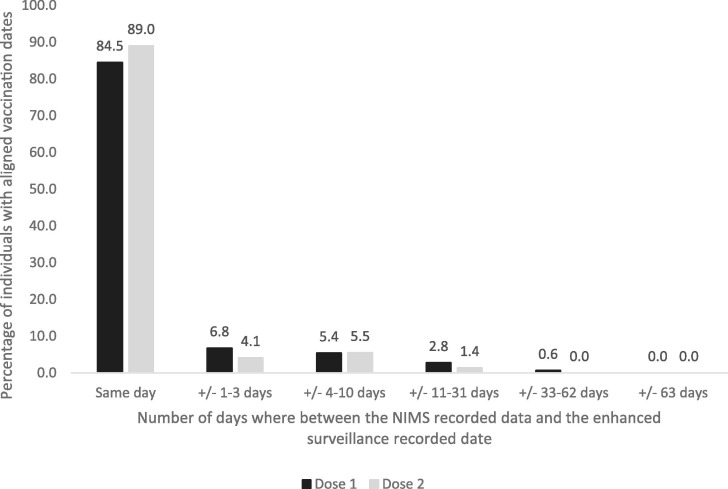

Of the 813 people who had a first vaccination according to both NIMS and the enhanced surveillance questionnaire, 799/813 (98.3 %) self-reported a vaccination date for their first dose. There was good agreement between the vaccination dates; 675/799 (84.5 %) had the same date of vaccination according to NIMS and the enhanced surveillance questionnaire while 729/799 (91.2 %) people self-reported a date which was within 3 days of the date recorded in NIMS (median difference: 0 days, IQR: 0–0 days). Of the 299 people who had a second vaccination date recorded in NIMS, 291/299 (97.3 %) self-reported a vaccination date for their second dose. A total of 259/291 (89.0 %) self-reported the same date as that which was recorded in NIMS whilst 271/291 (93.1 %) self-reported a date which was within 3 days of the date recorded in NIMS (median difference: 0 days, IQR: 0–0 days) (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Total percent of people whose vaccination dates recorded on NIMS were on the same day or up to beyond 63 days apart compared to results from the enhance surveillance questionnaire.

4. Discussion

NIMS has been highly beneficial for public health agencies, NHS England and Improvement and UKHSA, in supplying, delivering and evaluating the COVID-19 vaccination programme. This centralised system records details on vaccinations from across the country, delivered in all types of settings in quasi real-time. UKHSA receives daily outputs from NIMS allowing for rapid monitoring of trends in age-specific vaccine coverage and identifying sub-populations with poor coverage to be targeted quickly. This information has been used to provide evidence to policy makers and the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation, an independent expert group that advises the UK government on immunisation recommendations [14]. Official statistics on vaccine coverage are also produced using the NIMS and a previous study has highlighted the strengths and limitations of using NIMS for vaccine coverage purposes [15]. Furthermore, UKHSA have been able to link COVID-19 testing data to NIMS for rapid vaccine effectiveness surveillance among defined cohorts, which historically has not been easy to conduct [16], [17]. In the past, vaccine effectiveness studies for infections such as influenza have relied on a variety of data sources such as sentinel surveillance systems data, swabbing forms or data recorded in GP datasets obtained by telephone or postal letters [18], [19]. Vaccine effectiveness for childhood immunisations have used aggregated national coverage estimates and local CHIS data derived from multiple sources and requires several user permissions and the linkage of several datasets [20], [21], [22]. The results comparing NIMS data to the case-based enhanced surveillance system data indicate high accuracy of the information recorded in NIMS. These comparisons should continue to be monitored to ensure that the quality of the data doesn’t change.

Finally, NIMS data is retained in a highly secure server environment shared directly within UKHSA under The Health Service (Control of Patient Information) Regulations 2002; specifically regulation 3(1)(d)(iii) and (iv) – “monitoring and managing the delivery, efficacy and safety of immunisation programmes and adverse reactions to vaccines and medicines” [23], and under Section 251 of the 2006 National Health Service Act. This allows the common law duty of confidentiality to be set aside in specific circumstances, such as for vaccination programmes where anonymised information is not sufficient, such as monitoring adverse reactions to vaccines and the delivery of efficacy and safety of immunisation programmes [24].UKHSA have a Data Sharing Agreement (DSA) which aligns with current Caldicott Principles [25] and sets a legal framework for using the data within the organisation. Those who wish to use the data must meet the DSA principles and apply for access to the data with an acceptable explanation of how the data will be used. The data are then shared in a secure SQL environment and all work is conducted on a secure server. Having access to NIMS and the appropriate sharing agreements has allowed for important surveillance and joint research collaborations to be conducted such as the risk of thrombocytopenia and thromboembolism after covid-19 vaccinations [26].

4.1. Limitations and improvements to NIMS

Currently the data in NIMS can only be linked for individuals with an NHS number where demographic details can be populated from the GP record or hospital record data. Those without an NHS number can opportunistically receive a vaccine and an NHS number will be allocated to that individual at vaccination in the NHS Spine. These individuals’ records will only contain information from their vaccine event. As such, it is possible that some people are missing opportunities to be invited for a vaccination. Though the numbers of individuals without an NHS number is marginal (based on the population of the country compared to the number of individuals with and NHS number), the most vulnerable populations (migrants, asylum seekers, illegal immigrants) are more likely to not have an NHS number, and as such excluding them from the benefit of NIMS may exacerbate health inequalities.

The use of PoC apps has made for more efficient data entry, however, errors due to manual entry are still possible. Many of these errors can only be validated at the vaccination site where the vaccine was delivered. Bar code scanners were introduced to reduce data entry burden and limit manual entry errors, however, the rollout of barcode scanners has been variable across the country. Furthermore, the packaging of current vaccines still do not leave sufficient space for barcodes to be added to individual vials, which contain up to 8–10 doses. Therefore, on some occasions batch numbers have been pre-loaded in an attempt to limit data entry error. PoC apps should be further developed and improved with more input from GPs, nurses and immunisers in order to reduce burden and ensure high data quality.

Finally, though NIMS is based on a unique NHS number, this number is only linked to health services datasets. Linking to non-health related indicators such as occupation, emigration are not possible using the NHS number. Parts of NIMS’ data have attempted to overcome this limitation by linking to other datasets such as the NHS Electronic Staff Record to identify substantive staff employed by the NHS, which is only a subset of frontline healthcare workers. Some countries, such as Denmark, have overcome this barrier as they can use the a Civil Registration System (CPR-registeret) which also collects and updates information on non-health related factors that could affect vaccination uptake such as civil status, emigration etc [27], [28].

4.2. Conlusions

Prior to NIMS, England did not have a national immunisation information system with individual level data for the entire population. Routine immunisations are recorded on GP records and in the CHIS for childhood immunisations up to the child’s 18th birthday and work is being conducted on improving child health data through the Digital Child Health Transformation Programme [29]. Though these systems are capable of monitoring vaccination and sending invitations and reminders for vaccination appointments like NIMS, CHISs and GP systems are currently not all interoperable and risk duplicating or missing individuals, thus impacting accuracy of the data [3].

The 2009 Swine Flu pandemic highlighted the importance of vaccine registers and immunisation information systems [30]. NIMS has served as a foundation for COVID-19 vaccines surveillance since the introduction of the COVID-19 vaccination programme and has begun to be used for seasonal influenza vaccines. Without such a system centrally collecting individual level data UKHSA would not be able to provide vaccine coverage data with the same granularity and accuracy or provide some of the world’s first vaccine effectiveness estimates.

Furthermore, the results from validating NIMS data to self-reported vaccination details from the enhanced surveillance system indicates high accuracy and completeness of the data in NIMS. It is important to note that the self-reported questionnaire is not a gold standard, therefore, the difference in completeness and accuracy observed may also be due to a lack of accuracy in the questionnaire results, rather than NIMS. For example, recall bias or data entry errors in the self-reported forms could also account for some differences between the two systems. Any data quality issues in NIMS can be flagged with NHS Digital who review the queries and amend the data when possible.

To appropriately monitor the COVID-19 pandemic globally and the impact of COVID-19 vaccines, countries around the world should adopt national immunisation registers of systems that can be rapidly linked to health data. In England, NIMS should continue to be developed to ease data entry burden at immunisation sites. NIMS should also be expanded to allow individuals with no NHS numbers to be better monitored and data linkages could be expanded allowing for linkage to non-healthcare related datasets that may impact access and behaviours to vaccines. Finally, the expansion of NIMS to monitor other routine immunisation programmes would be highly valuable.

5. Summary Table

What is already known on the topic:

|

6. Ethics Approval

Surveillance of covid-19 vaccination data is undertaken under Regulation 3 of The Health Service (Control of Patient Information) Regulations 2002 to collect confidential patient information (https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2002/1438/regulation/3/made) under Sections 3(i) (a) to (c), 3(i)(d) (i) and (ii) and 3(3).

Funding statement

There was no external funding for this study.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank colleagues from System C & Graphnet Care Alliance, NHS Digital and South Central and West CSU for their continued support in providing NIMS data that we needed for surveillance and monitoring vaccine coverage. We would also like to thank the COVID Data Store and ImmForm teams at Public Health England who process the daily NIMS feed at UKHSA. Finally, we thank the UKHSA nurses.

References

- 1.Pebody R. Vaccine registers – experiences from Europe and elsewhere. 2012;17(17):20159. https://doi.org/10.2807/ese.17.17.20159-en. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Johansen K., Lopalco P.L., Giesecke J. Immunisation registers–important for vaccinated individuals, vaccinators and public health. Euro surveillance: Bulletin Europeen sur les maladies transmissibles. Eur. Commun. Disease Bull. 2012 Apr 19;17(16) PMID: 22551460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amirthalingam G., White J., Ramsay M. Measuring childhood vaccine coverage in England: the role of Child Health Information Systems. Euro surveillance : bulletin Europeen sur les maladies transmissibles = European communicable disease bulletin. 2012 Apr 19;17(16) PMID: 22551461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Technical Report Immunisation information systems in the EU and EEA Results of a survey on implementation and system characteristics. 2017.

- 5.Graphnet. National Immunisation Management System (NIMS). 2021. https://www.graphnethealth.com/solutions/immunisation-systems/ [accessed May 21, 2021].

- 6.NHS Digital. Support delivery of vaccinations. 2020. https://digital.nhs.uk/coronavirus/nhs-digital-coronavirus-programme-updates/programme-updates-15-december-2020/support-delivery-of-vaccinations [accessed Jun 08, 2021].

- 7.NHS England. National COVID-19 and Flu Vaccination Programmes: The National Immunisation Management Service. 2021. https://www.england.nhs.uk/contact-us/privacy-notice/national-flu-vaccination-programme/ [accessed Jun 08, 2021].

- 8.NHS Digital. NHS Spine. 2021. https://digital.nhs.uk/services/spine [accessed May 27, 2021].

- 9.NHS Digital. NHS Digital publishes information on ethnicity recording in the NHS to aid planning and research for COVID-12021. https://digital.nhs.uk/news-and-events/latest-news/nhs-digital-publishes-information-on-ethnicity-recording-in-the-nhs-to-aid-planning-and-research-for-covid-19 [accessed May 21, 2021].

- 10.Lee D., Cornet R., Lau F., de Keizer N. A survey of SNOMED CT implementations. J. Biomed. Inform. 2013;2013/02/01/;46(1):87–96 doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Statistics. OfN. English indices of deprivation 2019. 2019. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/english-indices-of-deprivation-2019 [accessed Feb 17, 2021].

- 12.The Health Service (Control of Patient Information) Regulations 2002 Coronavirus. 2002. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2002/1438/regulation/3/made [accessed Jul 26, 2021].

- 13.Public Health England. COVID-19 vaccine surveillance strategy 2021. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-vaccine-surveillance-strategy [accessed Jul 26, 2021].

- 14.Gov.uk. Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation. 2021. https://www.gov.uk/government/groups/joint-committee-on-vaccination-and-immunisation [accessed May 27, 2021].

- 15.Tessier E., Rai Y., Clarke E., Lakhani A., Tsang C., Makwana A., et al. Characteristics associated with COVID-19 vaccine uptake among adults aged 50 years and above in England (8 December 2020–17 May 2021): a population-level observational study. BMJ Open. 2022;12(3):e055278. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-055278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lopez Bernal J., Andrews N., Gower C., Robertson C., Stowe J., Tessier E., et al. Effectiveness of the Pfizer-BioNTech and Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccines on covid-19 related symptoms, hospital admissions, and mortality in older adults in England: test negative case-control study. BMJ. 2021;373:1088. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stowe J, Andrews N, Gower C, Gallagher E, Utsi L, Simmons R, Thelwall S, Tessier E, Groves N, Dabrera G, Myers R, Campbell C, Amirthalingam G, Edmunds M, Zambon M, Brown K, Hopkins S, Chand M, Ramsay M, Lopez Bernal J. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines against hospital admission with the Delta (B.1.617.2) variant. 2021. https://fpmag.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Effectiveness-of-COVID-19-vaccines-against-hospital-admission-with-the-Delta-B_1_617_2variant.pdf [accessed Jul 20, 2021].

- 18.Pebody R., Warburton F., Ellis J., Andrews N., Potts A., Cottrell S., et al. End-of-season influenza vaccine effectiveness in adults and children. United Kingdom. 2016/17. 2017;22(44):17–00306. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.44.17-00306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walker J.L., Andrews N.J., Amirthalingam G., Forbes H., Langan S.M., Thomas S.L. Effectiveness of herpes zoster vaccination in an older United Kingdom population. Vaccine. 2018/04/19;36(17):2371–2377. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walker J.L., Andrews N.J., Atchison C.J., Collins S., Allen D.J., Ramsay M.E., et al. Effectiveness of oral rotavirus vaccination in England against rotavirus-confirmed and all-cause acute gastroenteritis. Vaccine X. 2019/04/11;1 doi: 10.1016/j.jvacx.2019.100005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parikh S.R., Andrews N.J., Beebeejaun K., Campbell H., Ribeiro S., Ward C., et al. Effectiveness and impact of a reduced infant schedule of 4CMenB vaccine against group B meningococcal disease in England: a national observational cohort study. Lancet. 2016/12/03;388(10061):2775–2882. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31921-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ladhani S.N., Andrews N., Parikh S.R., Campbell H., White J., Edelstein M., et al. Vaccination of Infants with Meningococcal Group B Vaccine (4CMenB) in England. 2020;382(4):309–317. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1901229. PMID: 31971676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.legislation.gov.uk. The Health Service (Control of Patient Informaiton) Regulations 2002: Communicable Disease and other risks to public health. 2002. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2002/1438/regulation/3/made [accessed Jul 20, 2021].

- 24.Legislation. National Health Service Act 2006. 2006. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2006/41/section/251 [accessed Jul 15, 2021].

- 25.The UK Caldicott Guardian Council. 2020. https://www.ukcgc.uk/ [accessed Jul 20, 2021].

- 26.Hippisley-Cox J., Patone M., Mei X.W., Saatci D., Dixon S., Khunti K., et al. Risk of thrombocytopenia and thromboembolism after covid-19 vaccination and SARS-CoV-2 positive testing: self-controlled case series study. BMJ. 2021;374 doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1931. PMID: 34446426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hviid A. Postlicensure epidemiology of childhood vaccination: the Danish experience. Expert Rev. Vaccines. 2006/10/01;5(5):641–649. doi: 10.1586/14760584.5.5.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.International Institute for Vital Registration and Statistic. The Civil Registration System in Denmark. 1996. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/isp/066_the_civil_registration_system_in_denmark.pdf [accessed Jul 27, 2021].

- 29.NHS England. Digital Child Health Transformation Programme. 2021. https://www.england.nhs.uk/digitaltechnology/child-health/ [accessed Jul 26,/2021].

- 30.Johansen K, Lopalco PL, Giesecke J. Special edition: Immunisation registers in Europe and elsewhere. 2012. http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=20151 [accessed Jul 26, 2021].