Problem

Using pass/fail (P/F) course grades may motivate students to perform well enough to earn a passing grade, giving them a false sense of competence and not motivating them to remediate deficiencies. The authors explored whether adding a not yet pass (NYP) grade to a P/F scale would promote students’ mastery orientation toward learning.

Approach

The authors captured student outcomes and data on time and cost of implementing the NYP grade in 2021 at the University of Utah School of Medicine. One cohort of medical students, who had experienced both P/F and P/NYP/F scales in years 1 and 2, completed an adapted Achievement Goal Questionnaire–Revised (AGQ-R) in fall 2021 to measure how well the P/NYP/F grading scale compared with the P/F scale promoted mastery orientation and performance orientation goals. Students who received an NYP grade provided feedback on the NYP process.

Outcomes

Students reported that the P/NYP/F scale increased their achievement of both mastery and performance orientation goals, with significantly higher ratings for mastery orientation goals than for performance orientation goals on the AGQ-R (response rate = 124/125 [99%], P ≤ .001, effect size = 0.31). Thirty-eight students received 48 NYP grades in 7 courses during 2021, and 3 (2%) failed a subsequent course after receiving an NYP grade. Most NYP students reported the NYP process enabled them to identify and correct a deficiency (32/36 [89%]) and made them feel supported (28/36 [78%]). The process was time intensive (897 hours total for 48 NYP grades), but no extra funding was budgeted.

Next Steps

The findings suggest mastery orientation can be increased with an NYP grade. Implementing a P/NYP/F grading scale for years 1 and/or 2 may help students transition to programmatic assessment or no grading later in medical school, which may better prepare graduates for lifelong learning.

Problem

Many aspects of grading and assessment can inadvertently cause students to focus on performance rather than mastery of material or skill progression. 1 Because course grades continue to be used by most medical schools to determine advancement, it is unclear whether grading can be structured to motivate students toward a mastery orientation. Such an advance in grading is critical because residency programs use course grades in selection decisions, 2 which may further perpetuate a performance orientation to learning.

Over the past 40 years medical schools have tried to change student motivation by changing course grading. In the 1980s, most medical schools relied on tiered grading (e.g., A-F; honors, high pass, and pass) or numerical rankings in courses to determine advancement and graduation. 3 In the 1990s, many schools moved away from tiered grading to pass/fail (P/F), which increased student wellness and satisfaction with no decrease in performance or residency ratings. 4,5 However, P/F grading can give students a false sense of competence and does not motivate them to remediate deficiencies. 5 To address this concern for clinical courses, some medical schools coupled the change to P/F grading with increased feedback and coaching. P/F clerkship grading motivated students to improve clinically and not just “look good,” 6,7 but whether that motivation was due to the change in grading, more feedback or coaching, or a combination of these factors is unknown. Finally, some medical schools have abandoned course grades altogether for a programmatic assessment model. 8 Students at these schools initially had difficulty transitioning to no grades but eventually were motivated toward excellence. 8 Completely eliminating grades can change long-term motivation, but students may need some sort of grading transition/hybrid model in the short term. Before eliminating grades, we may want to rethink what we want to motivate, measure, and promote with grades.

Ideally, grades should be a proxy for students’ mastery of material. Students with a mastery orientation to learning strive toward excellence by identifying strengths and weaknesses, and they are motivated to seek out opportunities to improve weaknesses. Students with a performance orientation strive to look good by not admitting or addressing weaknesses, and they are primarily motivated to achieve a grade or pass an assessment. 9 We explored whether allowing students more chances to reach a passing grade would promote a mastery orientation because both P/F and tiered grading have limitations for changing motivation. Specifically, we implemented a not yet pass (NYP) grade at the University of Utah School of Medicine.

Approach

Our primary aim was to promote a mastery orientation toward learning with the NYP grade for all students and our secondary aim was to evaluate the impact of the NYP process on the students who received an NYP grade (NYP students) to determine sustainability. The NYP grade refers to a letter grade in a course for a competency (knowledge or professionalism), and the NYP process refers to steps a student needs to complete to turn the NYP grade to a P grade. This study was deemed exempt by the University of Utah Institutional Review Board.

Participants and setting

Participants were University of Utah School of Medicine students with a 2024 expected graduation year (2024 cohort) who had experienced both P/F and P/NYP/F grading in medical school years 1 and 2. The curriculum for years 1 and 2 includes foundational sciences, humanities, and clinical medicine courses. The foundational sciences courses require competency in knowledge (assessed primarily with multiple-choice question quizzes and examinations), and all courses require competency in professionalism (assessed with a rubric completed by faculty and turning in assignments on time). Before academic year 2019–2020, the grading scale was P/F. An NYP grade was added for the foundational sciences courses in academic year 2019–2020. In spring 2021 (year 1 for the 2024 cohort), the P/NYP/F scale was used in all foundational sciences and humanities courses, and students no longer received due date reminders. In fall 2021 (year 2 for the 2024 cohort), the P/NYP/F scale was used in all year 1 and 2 courses. The study period was spring 2021 (year 1) and fall 2021 (year 2), which included 7 P/NYP/F courses for the 2024 cohort. To provide context, students in the 2023 cohort had received 6 failing grades in the same 7 courses (all for knowledge deficiencies).

NYP process

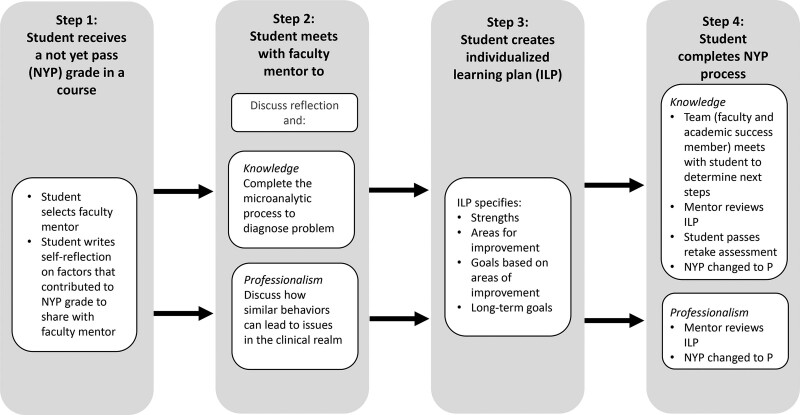

The NYP grade criteria and process were outlined in each course syllabus. We intentionally designed a supportive NYP process to help students pass a course after receiving an NYP grade because the grade alone was not likely to promote growth. 6,7 Steps for the NYP process are outlined in Figure 1. After receiving the NYP grade and meeting with a faculty mentor, the student creates an individualized learning plan (ILP) with the faculty mentor to address the specific deficiency that led to the NYP grade. The timing of the process is driven by the student. For knowledge NYP grades, students are typically engaged in their subsequent course and can choose to focus primarily on that course, waiting for a break in the curriculum to complete the last step in the NYP process (completion of ILP and passing a retake assessment). Professionalism NYP grades are usually resolved within a few weeks of the NYP process. Students are limited to 1 NYP grade at a time within a competency.

Figure 1.

The not yet pass (NYP) process at the University of Utah School of Medicine in 2021. Students complete steps 1 to 3 within a few weeks of receiving the NYP grade. For knowledge NYP grades, step 4 occurs when the student feels ready to retake the assessment; for professionalism NYP grades, step 4 is typically completed within a few weeks of receiving the NYP grade. Abbreviation: P, pass.

Goal orientation aim

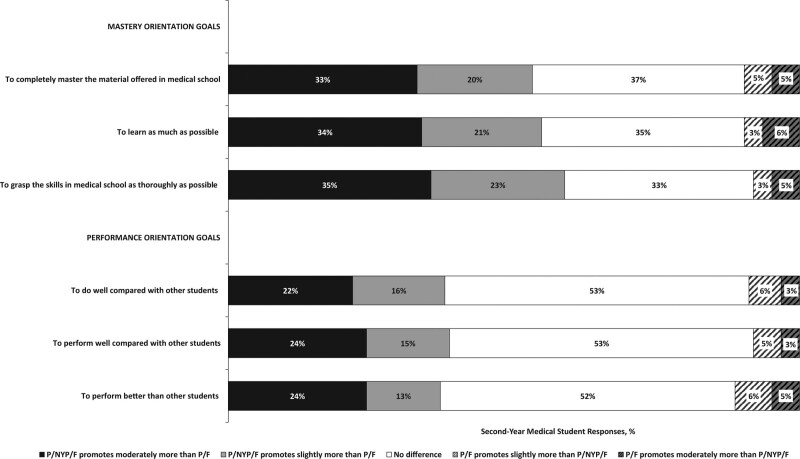

Medical students in the 2024 cohort completed an adapted Achievement Goal Questionnaire–Revised (AGQ-R) 10 via a fall 2021 end-of-course survey. Scores from the AGQ-R have validity evidence, 9 but our adaptations may change the validity argument. We revised response options so that students could compare how well each goal statement was promoted with the P/NYP/F grading scale compared with the P/F grading scale. We excluded AGQ-R avoidance scale items because of redundancy with approach scale items and confusing wording (e.g., “I am striving to avoid an incomplete understanding”). 10 Responses were converted to ratings, with 1 indicating P/NYP/F slightly or moderately promotes more than P/F, 0 indicating no difference, and 1 indicating P/F slightly or moderately promotes more than the P/NYP/F scale. To determine whether a mastery orientation was promoted to a higher extent than a performance orientation, we compared mean ratings for the 3 mastery orientation goals with the mean ratings of the 3 performance orientation goals (Figure 2) with the Wilcox signed rank test. A 1-tailed test, P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Figure 2.

Percentage of 124 University of Utah School of Medicine second-year medical student responses to how well each mastery orientation goal and performance orientation goal was promoted by a pass (P)/not yet pass (NYP)/fail (F) grading scale relative to a P/F grading scale in 2021. Items were adapted from the Achievement Goal Questionnaire–Revised (AGQ-R). 10

Evaluation aim

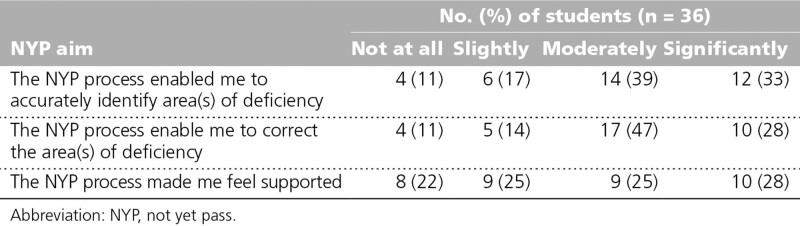

For our secondary aim of evaluating the impact of implementing the NYP grade and process, students were sent an online survey immediately after their NYP was changed to a P or F and were asked to rate how well the NYP process enabled them to accurately identify area(s) of deficiency, correct the area(s) of deficiency, and feel supported, using a scale of not at all, slightly, moderately, or significantly. Numbers and percentages were computed for the ratings. If a student earned multiple NYP grades, we included only their first set of ratings in the analyses. We also tracked subsequent NYP grades and course failures during the study period.

In addition, we reviewed the curriculum operating budget to determine whether there were any extra costs with the NYP process. At the end of spring 2021, staff and faculty mentors were sent an online survey and asked to self-report mean time to manage or mentor 1 student through the NYP process. The NYP students also self-reported time to complete the NYP process with an online survey in Spring 2021. Mean times for staff, faculty mentors, and students were summed and multiplied by the number of NYP grades to determine the total time.

Outcomes

Students’ adapted AGQ-R responses (response rate = 124/125 [99%]) are provided in Figure 2. Students reported the P/NYP/F grading scale promoted achievement of both mastery orientation goals (mean [SD], 0.47 [0.62]) and performance orientation goals (mean [SD], 0.28 [0.59]) but to a higher extent for mastery orientation goals (effect size = 0.31, P ≤ .001). Approximately one-third of the students (33–37%, n = 41–46) reported the addition of the NYP grade had no effect on achieving mastery orientation goals, while about one half (52–53%, n = 64–66) reported the NYP grade had no effect on achieving performance orientation goals; this further suggests that students felt the NYP had a larger effect on mastery-orientation goals.

Thirty-eight students received 48 NYP grades: 22 NYP grades in year 1 courses and 26 in year 2 courses (33 for professionalism and 15 for knowledge). Five of the 38 students received 2 NYP grades, 1 received 3 NYP grades, and 1 received 4 NYP grades. NYP students’ ratings (response rate = 36/38 [95%]) of the NYP process are provided in Table 1. Thirty-two (89%) reported the process enabled them to identify and correct a deficiency, and 28 (78%) reported feeling supported by the process.

Table 1.

Degree to Which 36 Students Who Received an NYP Grade Reported Being Supported and Enabled to Identify and Correct Deficiencies Through the NYP Process, University of Utah School of Medicine, 2021

Thirty-one of the 38 NYP students (82%) resolved their NYP grade and did not have subsequent NYP or F grades within a competency. Six students (16%) received a subsequent NYP grade in the same competency (4 for knowledge and 2 for professionalism). Three students (2%) with a prior NYP knowledge grade failed a course for not meeting the passing criteria after completing the NYP process or not meeting the passing criteria in a subsequent course while having an unresolved NYP grade for the same competency.

Personnel effort (i.e., staff and faculty mentor time) was redistributed to manage the NYP process, but no additional funding was budgeted. Students’ NYP progress was tracked in our learning management system. Students spent a mean (SD) of 4.7 (2.6) hours completing the process for a professionalism NYP grade and 31 (36) hours for a knowledge NYP grade; the latter type was primarily addressed during curriculum breaks to avoid interfering with ongoing coursework. Five mentors spent a mean (SD) of 2.2 (0.95) hours with each student, with more time spent supporting students with knowledge NYP grades. Academic staff spent 0.5 hours on each NYP grade. One staff manager spent 1.5 hours on each professionalism NYP grade, and another staff manager spent 3.5 hours on each knowledge NYP grade. Knowledge NYP grades also required 3 additional hours of proctor staff time. The sum of mean student, mentor, and staff time was 40 hours (means, 31, 2.2, and 7, respectively) for a knowledge NYP grade and 9 hours (4.7 + 2.2. + 2) for a professionalism NYP grade, for a total of 897 hours for the 48 NYP grades.

Next Steps

Student responses on the adapted AGQ-R indicate the P/NYP/F grading scale promoted both mastery and performance orientation goals but to a greater extent for mastery orientation goals. The impact on both goal types may suggest that goal orientation is not an either/or concept, especially to medical students, who are likely to consider higher achievement in both areas to be positive. In addition, other aspects may exist in medical school that obstruct a mastery orientation, such as class ranking, even when used in conjunction with a P/NYP/F grading scale. Thus, all factors must be considered when attempting to change students’ orientation toward learning.

Given the student outcomes achieved, the NYP process is likely worth sustaining with a few modifications. The small number of students who earned multiple NYP or failing grades after completing the NYP process for knowledge deficiency was concerning because of the possibility that we were no longer supporting those students but instead enabling deficiencies. Our results suggest 2 or more NYP grades within a competency may be a red flag, signaling a need for additional intervention. Effective academic year 2022–2023, there is a limit of 2 NYP grades allowed across years 1 and 2, excluding the first semester of year 1. The first semester courses are being excluded to prevent disadvantaging students who are unable to complete the NYP process during the 2 weeks before they enter the second semester by no longer having the NYP safety net. In addition, students will be notified by a course director when they receive an NYP grade instead of receiving a templated email, which we hope will make the process more supportive. Finally, a question about what students think the school can do to support their success has been added to the NYP reflection prompt.

A limitation of our preliminary evaluation of this innovation is that we only investigated NYP grades in early medical school courses. Whether a P/NYP/F grading scale will continue to promote mastery orientation in clerkships is unknown. In addition, generalizability of the outcomes of this innovation may not become apparent until more data are collected. Finally, the number of NYP grades was higher than expected, so to sustain the program we need more faculty mentors and/or we need to provide a percentage of salary support for mentors’ time.

Grades can perpetuate a fixed mindset in health professions training. Most medical schools use course grades for advancement decisions, most residency programs use those course grades for selection, and, perhaps unsurprisingly, students may think their self-worth is defined by grades. Our results suggest that we do not need to eliminate grades, but we can instead increase mastery orientation with addition of an NYP grade. In addition, a P/NYP/F grading scale in years 1 and/or 2 may help students transition to programmatic assessment or no grading later in medical school. This transition may better prepare graduates for lifelong learning.

Acknowledgments:

The authors would like to thank Dr. Lorelei Lingard for providing valuable feedback on prior drafts of the Problem and Approach sections.

Footnotes

Funding/Support: None reported.

Other disclosures: None reported.

Ethical approval: This study was deemed exempt by the University of Utah Institutional Review Board, September 1, 2021, #00109278.

Contributor Information

Janet Lindsley, Email: janet@biochem.utah.edu.

Kathryn B. Moore, Email: kathryn.moore@neuro.utah.edu.

Tim Formosa, Email: tim@biochem.utah.edu.

Karly Pippitt, Email: Karly.Pippitt@hsc.utah.edu.

References

- 1.Teunissen PW, Bok HG. Believing is seeing: How people’s beliefs influence goals, emotions and behaviour. Med Educ. 2013;47:1064–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Resident Matching Program. 2021 Results of the 2021 NRMP program director survey. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/2021-PD-Survey-Report-for-WWW.pdf. Accessed September 2, 2022.

- 3.Magarian GJ, Mazur DJ. A national survey of grading systems used in medicine clerkships. Acad Med. 1990;65:636–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White CB, Fantone JC. Pass-fail grading: Laying the foundation for self-regulated learning. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2010;15:469–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reed DA ST, Satele DW, et al. Relationship of pass/fail grading and curriculum structure with well-begin among preclinical medical students: A multi-institutional study. Acad Med. 2010;86:1367–1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klamen DL, Williams R, Hingle S. Getting real: Aligning the learning needs of clerkship students with the current environment. Acad Med. 2019;94:53–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seligman L, Abdullahi A, Teherani A, Hauer KE. From grading to assessment for learning: A qualitative study of student perceptions surrounding elimination of core clerkship grades and enhanced formative feedback. Teach Learn Med. 2021;33:314–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harrison CJ, Konings KD, Dannefer EF, Schuwirth LWT, Wass V, van der Vleuten CPM. Factors influencing students’ receptivity to formative feedback emerging from different assessment cultures. Perspect Med Educ. 2016;5:276–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cook DA, Castillo RM, Gas B, Artino AR. Measuring achievement goal motivation, mindsets and cognitive load: Validation of three instruments’ scores. Med Educ. 2017;51:1061–1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elliot AJ, Murayama K. On the measurement of achievement goals: Critique, illustration, and application. J Educ Psychol. 2008;100:613–628. [Google Scholar]