Abstract

We report a case of 77-year-old woman with fulminant type 1 diabetes (T1D) who developed diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) after the second dose of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine tozinameran. The patient had been diagnosed as having T1D associated with an immune-related adverse event caused by pembrolizumab at the age of 75. After the second dose of tozinameran, she developed DKA and needed intravenous insulin infusion and mechanical ventilation. Although the direct causal relationship between the vaccination and the DKA episode could not be proven in this case, published literatures had suggested the possibility of developing DKA after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in patients with T1D. As the magnitude of the risk of the combination of the known adverse drug reactions of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine and T1D patients’ vulnerability to sick-day conditions is not yet thoroughly assessed, future studies such as a non-interventional study with adequate sample size would be required to address this issue.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, Vaccine, Tozinameran, Type 1 diabetes (T1D), Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA)

Introduction

Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) is a serious acute complication of diabetes mellitus caused by the absolute deficiency of insulin. It is mainly characterized by metabolic acidosis due to excess blood ketone bodies, hyperglycemia, and dehydration. Triggers of DKA include acute onset of type 1 diabetes (T1D), discontinuation of insulin therapy, and the sick days caused by infection and other stresses [1].

Pembrolizumab is a monoclonal antibody against programmed death receptor-1 (PD-1), which is effective against various cancers. Fulminant T1D is one of its immune-related adverse events (irAEs) [2, 3]. The incidence of anti-PD-1 antibody-related T1D is less than 1%; however, these patients can rapidly develop DKA; thus, it is important to diagnose and treat this irAE as early as possible [4, 5].

Patients with diabetes mellitus have an increased susceptibility to infection including pneumonia, urinary tract infection, and skin infection [6–8]. At present, it is not clear whether diabetes may directly increase the risk of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) infection [9]; nevertheless, it is considered as a risk factor of the worse prognosis [10–13]. Thus, SARS-CoV-2 vaccination is recommended for patients with diabetes; however, not much is known about the risk of complication due to the potential sick days after vaccination.

We herein report a case of 77-year-old woman with fulminant T1D who developed DKA as a serious adverse event (SAE) of SARS-CoV-2 tozinameran vaccination (Comirnaty®, BioNTech, Mainz, Germany and Pfizer, New York, NY, USA).

Case report

A 77-year-old woman was transferred to the emergency department by ambulance due to disturbance of consciousness 2 days after the second dose of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine tozinameran.

The patient had a history of type 2 diabetes (T2D) with the background obesity since she was 67 years old, and started insulin therapy when she was 68 years old. At the age of 69, she was operated for left breast cancer, and received chemotherapy consisting of 5-fluorouracil, epidoxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, docetaxel hydrate, letrozole, trastuzumab, tamoxifen citrate, and capecitabine. When she was 73 years old, she was diagnosed as having left lung adenocarcinoma, and received pembrolizumab therapy (200 mg, iv, q3 weeks). Then, she developed hypothyroidism and secondary adrenal insufficiency as irAEs of pembrolizumab at the age of 74. She was also radiated for metastatic brain tumor. After the 11th administration of pembrolizumab, grade 3 adrenal dysfunction and eruption appeared, the subsequent administration had to be discontinued. Although there had been no episode of diabetic ketoacidosis, her serum C-peptide level turned out to be below the detectable level at the age of 75, and she was diagnosed as pembrolizumab-induced fulminant T1D while she was already being treated with insulin for T2D. The total daily insulin dose was 81 units/day, reflecting background obesity with body mass index of 27.7. She was able to continue multiple daily injections of insulin and regular self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG). She had been receiving continuous education of carbohydrate counting, and the healthcare providers did not recognize the signs of dementia through their clinical practice. She was living with her supportive family.

The patient had been administered 0.3 mL of the COVID-19 mRNA tozinameran vaccine intramuscularly at the local clinic, 23 days prior (lot number: EY 2173) and 2 days prior (lot number: FA5715) to the hospitalization. No adverse event was recorded after the first dose of tozinameran. On the prior day to the second dose of the vaccination, she visited a local clinic complaining of rhinorrhea, and was prescribed oral desloratadine (5 mg per day). She left the clinic without any remarkable acute adverse events after the second dose of tozinameran, and according to the SMBG record downloaded from the blood glucose meter she was using, the blood glucose levels were 154 mg/dL in the morning, 338 mg/dL in the afternoon, and 449 mg/dL in the evening. On the next day, she visited the clinic with low-grade fever of 37.2 °C, poor appetite, and rhinorrhea. The physician provided her intravenous administration of ceftazidime hydrate (500 mg per day) and 200 mL of infusion solution, based on the diagnosis of acute bronchitis and dehydration. She was also prescribed oral cefcapene pivoxil hydrochloride hydrate (300 mg per day), cloperastine hydrochloride (60 mg per day), ambroxol hydrochloride (45 mg per day), and acetaminophen (400 mg per dose). There was no SMBG record on this day, and no information was obtained from the patient or her family regarding the insulin injections. Two days after the second dose, she stayed in bed and could not eat. The recorded blood glucose level was as high as 543 mg/dL in the afternoon; however, whether she injected insulin or not on this day remained unclear, too. Late in the evening, her family called an ambulance when they found her unconscious.

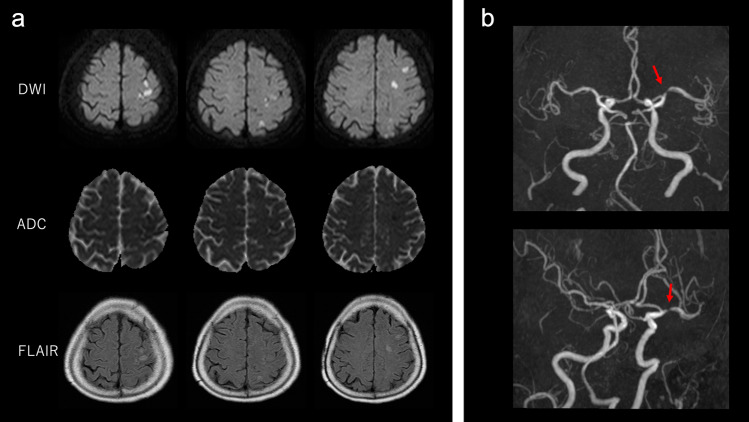

When the patient arrived at the hospital, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) was 6/15, with right conjugate deviation; pulse was 120 beats/minute; blood pressure was 90/60 mmHg; respiratory rate was 30 breaths/minute, with Kussmaul breathing; blood oxygen saturation was unmeasurable by pulse oximeter; and body temperature was 38.2 °C. Laboratory investigation revealed a metabolic acidosis with arterial blood pH of 6.85, pO2 114.6 mmHg, and pCO2 25.7 mmHg with oxygen inhalation (Table 1). Serum glucose level was 683 mg/dL and total ketone body level was 7,820 μmol/L. White blood cells (WBCs) were 15,000/μL, segmented neutrophils were 72.6%, and C-reactive protein level was 37.61 mg/dL. Urinalysis showed no findings suggestive of a urinary tract infection. Rapid urinary antigen detection kit for Streptococcus pneumoniae and nasopharyngeal SARS-CoV-2 PCR were negative. Brain–chest–abdomen computed tomography (CT) was performed, but there was no lesion that could be the focus of infection. Blood cultures and urine cultures showed no significant bacterial growth. The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit with a diagnosis of DKA. She was intubated and ventilated because of her deteriorated respiratory condition. We started intravenous insulin infusion (0.1 units/kg/h), intravenous fluid infusion, and empirical antibiotic treatment. The average total daily insulin dose was 102 units/day during day 2 to day 6 after the hospitalization. Although her blood glucose levels were normalized on day 2, her level of consciousness did not improve. To rule out the possibility of meningitis, a lumber puncture was performed, but cerebrospinal fluid analysis was normal. Multiple subacute cerebral infarctions in the territory of the left middle cerebral artery was confirmed by brain magnetic resonance (MR) imaging (Fig. 1). MR angiography presented left middle cerebral artery M1 stenosis suggestive of atherothrombotic stroke (Fig. 1), and antiplatelet treatment was initiated. The patient’s GCS and serum C-reactive protein levels gradually improved within 1 week, though mild right hemiplegia still remained. After being extubated on day 11, oral feeding was initiated. She underwent extensive neurorehabilitation until she regained a power grade of 4/5 in right limbs, and finally she was discharged from the hospital to her home on the 34th day after admission.

Table 1.

Laboratory findings on admission

| Arterial blood gas analysis (O2 10 L/min) | |||||

| pH | 6.86 | Blood urea nitrogen | 26 | mg/dL | |

| PaO2 | 114.6 | mmHg | Creatinine | 2.46 | mg/dL |

| PaCO2 | 25.7 | mmHg | Sodium | 129 | mEq/L |

| HCO3− | 4.4 | mmol/L | Potassium | 5.8 | mEq/L |

| Base excess | −28.5 | mmol/L | Chloride | 83 | mEq/L |

| Glucose | 687 | mg/dL | Calcium | 9.4 | mg/dL |

| Lactate | 13.7 | mmol/L | C-reactive protein | 37.61 | mg/dL |

| Hematology | Ammonia | 515 | μg/dL | ||

| White blood cell | 15,000 | /μL | Procalcitonin | 4.72 | ng/mL |

| Neutrophil | 72.6 | % | Total ketone body | 7820 | μmol/L |

| Lymphocyte | 17.0 | % | Acetoacetic acid | 2020 | μmol/L |

| Monocyte | 9.4 | % | 3-Hydroxybutyric acid | 5800 | μmol/L |

| Eosinophil | 0.2 | % | HbA1c | 9.2 | % |

| Basophil | 0.8 | % | Congealing fibrinogenolysis system | ||

| Red blood cells | 4.19 × 106 | /μL | PT-INR | 1.20 | |

| Hemoglobin | 12.2 | g/dL | APTT | 30.8 | s |

| Hematocrit | 42.6 | % | Fiblinogen | 682 | mg/dL |

| Platelets | 256 × 103 | /μL | D-Dimer | 10.15 | μg/mL |

| Biochemistry and immunology tests | Urinalysis | ||||

| Total protein | 6.6 | g/dL | Protein | 2+ | |

| Albumin | 3.5 | g/dL | Glucose | 4+ | |

| Total bilirubin | 0.7 | mg/dL | Ketone | 3+ | |

| Creatine kinase | 205 | U/L | Blood | 1+ | |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | 90 | U/L | White blood cell | Negative | |

| Alanine aminotransferase | 34 | U/L | Nitrite | Negative | |

| Lactate dehydrogenase | 351 | U/L | |||

| Alkaline phosphatase | 145 | U/L | |||

| γ-Glutamyl transpeptidase | 47 | U/L | |||

Fig. 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) findings. a Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC), and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images. Brain DWI and FLAIR images show multiple acute cerebral infarctions in the territory of the middle cerebral artery. b MRA revealed left middle cerebral artery (M1) stenosis (red arrow)

Discussion

We experienced a case of DKA after the second dose of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine tozinameran with fulminant T1D in the background. In this case, the patient experienced sick days following the vaccination, and eventually developed DKA, probably as the result of failure in managing sick days. The family reported that the patient had been staying in bed and had poor oral intake; however, whether the patient injected insulin during this period was unclear. The record of SMBG with limited number of measurements suggested that the patient could not continue the routine self-management after the second dose of the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, and it is very likely that the patient could not inject insulin during this period. Although the HbA1c level was high, considering the age of the patient, the prescribed insulin dosage needed to be adjusted with the priority of hypoglycemia prevention. As there had been no prior episode of DKA, it is likely that the high HbA1c level did not predispose the DKA after the second dose of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. It remains unclear how significantly the insulin resistance caused by the inflammation after SARS-CoV-2 vaccine contributed to the development of DKA; the patient had been treated by insulin prior to the onset of pembrolizumab-induced fulminant T1D, and it was very likely that she had had pre-existing insulin resistance related to the obesity. The patient presented high white blood cell count and high serum CRP levels on admission; however, no clear evidence of bacterial infection such as pneumonia and urinary tract infection was identified; therefore, the inflammation was likely to be caused by SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. Other cause of metabolic acidosis, such as lactic acidosis, diarrhea, and intoxication of acidic chemical compound was not detected; the elevated blood urea nitrogen and creatinine levels were due to the dehydration rather than acute kidney failure, and was less likely to be the cause of metabolic acidosis. As the platelet count was not decreased in this case, complication of Thrombosis with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome (TTS) was not likely to be the cause of cerebral infarction; instead, dehydration could have been the trigger of its onset. It is also important to distinguish an adverse drug reactions (ADR) and an adverse event (AE); an ADR is defined as “an appreciably harmful or unpleasant reaction resulting from an intervention related to the use of a medicinal product” [14], whereas an AE is defined as “any untoward medical occurrence that may present during treatment with a pharmaceutical product but which does not necessarily have a causal relationship with this treatment” [15]. According to these definitions, this DKA episode was not considered to be classified as a serious ADR (SADR) of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination because the direct causal relationship could not be proven, and at the same time, it was considered to be classified as a serious AE (SAE) because the definition of AE refer to any untoward medical occurrence with or without the causal relationship. The effect of the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine on short-term glucose metabolism has not been clarified. Theoretically, the inflammation and hypercytokinemia after the vaccination could increase the insulin resistance, but not so much is known so far for this issue. The most frequently reported systemic reactions after the second dose for vaccine were fatigue (53.9%), headache (46.7%), myalgia (44.0%), chills (31.3%), fever (29.5%), and joint pain (25.6%) [16]. A 24-year-old female with T1D was reported to be complicated by DKA after the second dose of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine elasomeran (Spikevax®, Moderna, Cambridge, MA, USA) [17]. She was using an insulin pump and her HbA1c level was as high as 12.0%, which suggested insufficient glycemic control prior to the vaccination that may have influenced DKA complications after the vaccination. There were two case reports of a 20-year-old male and 24-year-old female with T1D who developed DKA following the second dose of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (Covishield®, AstraZeneca, Cambridge, UK) and BBV152 (Covaxin®, Bharat Biotech, Hyderabad, India), respectively [18]. There was another case report of DKA following the first dose of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine elasomeran; however, this patient had no documented history of T1D prior to the vaccination and appeared to have newly developed T1D [19]. Regarding the actual SARS-CoV-2 infection, there was a case report describing a patient with newly diagnosed T1D with DKA during the infection [20]. DKA was also reported to be a very common complication of confirmed or suspected SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with T1D [21].

Another possible concern is the safety of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in patients who have a history of anti-PD-1 antibody treatment. Anti-PD-1 antibody treatment activates the immune system, and the risk of irAE including T1D, hypothyroidism, hypoadrenocorticism, and hypopituitarism is well known [22]. A previous study reported that there was no significant correlation between the influenza vaccination and an increase in the incidence and severity of irAE [23]; a recent report suggested the safety of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in these patients was similar to the general population [24]. Further investigation regarding the safety of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in patients with the history of anti-PD-1 antibody treatment is required.

SARS-CoV-2 vaccination is proactively recommended for patients with T1D, but there is possibility that DKA may be complicated due to unsuccessful sick-day management. Preparation and early intervention for the potential sick days after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in patients with T1D appears to be important. As the magnitude of the risk of the combination of the known adverse drug reactions of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine and T1D patients’ vulnerability to sick-day conditions is not yet thoroughly assessed, future studies such as a non-interventional study with adequate sample size would be required to address this issue.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Yoko Taniguchi (Taniguchi Clinic, Kyoto, Japan) for supporting the preparation of the manuscript. English editorial assistance was provided by Medical English Service (Kyoto, Japan).

Data availability

There are no associated data available.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

All the authors declared no conflict of interest (COI).

Human rights statement

All the procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and/or with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and later versions. Informed consent or substitute for it was obtained from all patients for being included in the study. Written informed consent was obtained for the publication of this case report.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kitabchi AE, Umpierrez GE, Miles JM, Fisher JN. Hyperglycemic crises in adult patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1335–1343. doi: 10.2337/dc09-9032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hughes J, Vudattu N, Sznol M, et al. Precipitation of autoimmune diabetes with anti-PD1 immunotherapy. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:55–57. doi: 10.2337/dc14-2349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaudy C, Clévy C, Monestier S, et al. Anti-PD1 pembrolizumab can induce exceptional fulminant type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:e182–e183. doi: 10.2337/dc15-1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ikegami H, Kawabata Y, Noso S. Immune checkpoint therapy and type 1 diabetes. Diabetol Int. 2016;7:221–227. doi: 10.1007/s13340-016-0276-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baden M, Imagawa A, Abiru N, et al. Characteristics and clinical course of type 1 diabetes mellitus related to anti-programmed cell death-1 therapy. Diabetol Int. 2019;10:58–66. doi: 10.1007/s13340-018-0362-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benfield T, Jensen JS, Nordestgaard BG. Influence of diabetes and hyperglycaemia on infectious disease hospitalisation and outcome. Diabetologia. 2007;50:549–554. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0570-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shah BR, Janet EH. Quantifying the risk of infectious diseases for people with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:510–513. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.2.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casqueiro J, Casqueiro J, Alves C. Infections in patients with diabetes mellitus: A review of pathogenesis. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16(Suppl 1):S27–36. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.94253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Selvin E, Juraschek SP. Diabetes epidemiology in the COVID-19 pandemic. Diabetes Care. 2020;43:1690–1694. doi: 10.2337/dc20-1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsunaga N, Hayakawa K, Terada M, et al. Clinical epidemiology of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Japan: Report of the COVID-19 REGISTRY JAPAN. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(11):e3677–e3689. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Onder G, Rezza G, Brusaferro S. Case-fatality rate and characteristics of patients dying in relation to COVID-19 in Italy. JAMA. 2020;323:1775–1776. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumar A, Arora A, Sharma P, et al. Is diabetes mellitus associated with mortality and severity of COVID-19? A meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14:535–545. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang I, Anthonius M, Pranata R. Diabetes mellitus is associated with increased mortality and severity of disease in COVID-19 pneumonia - A systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14:395–403. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coleman JJ, Pontefract SK. Adverse drug reactions. Clin Med (Lond) 2016;16:481–485. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.16-5-481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Phillips R, Hazell L, Sauzet O, Cornelius V. Analysis and reporting of adverse events in randomised controlled trials: a review. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e024537. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bardeles JC, Gee J, Myers T. Reactogenicity following receipt of mRNA-Based COVID-19 vaccines. JAMA. 2021;325(21):2201–2202. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.5374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zilbermint M, Demidowich AP. Severe diabetic ketoacidosis after the second dose of mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccine. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2022 doi: 10.1177/19322968211043552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ganakumar V, Jethwani P, Roy A, et al. Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) in type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) temporally related to COVID-19 vaccination. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2022;16(1):102371. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2021.102371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yano M, Morioka T, Natsuki Y, et al. A case of new-onset type 1 diabetes after Covid-19 mRNA vaccination. Intern Med. 2022 doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.9004-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Potier L, Julla JB, Roussel R, et al. COVID-19 symptoms masking inaugural ketoacidosis of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Metab. 2021;47(1):101162. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2020.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ebekozien OA, Noor N, Gallagher MP, Alonso GT. Type 1 diabetes and COVID-19: preliminary findings from a multicenter surveillance study in the U.S. Diabetes Care. 2020;43:e83–e85. doi: 10.2337/dc20-1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang LS, Sousa RB, Tolaney SM, Hodi FS, Kaiser UB, Min L. Endocrine toxicity of cancer immunotherapy targeting immune checkpoints. Endocr Rev. 2019;40(1):17–65. doi: 10.1210/er.2018-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chong CR, Park VJ, Cohen B, Postow MA, Wolchok JD, Kamboj M. Safety of Inactivated influenza vaccine in cancer patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;70(2):193–199. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Waissengrin B, Agbarya A, Safadi E, Padova H, Wolf I. Short-term safety of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in patients with cancer treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(5):581–583. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00155-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

There are no associated data available.