Abstract

Background:

Adropin is a peptide encoded by the energy homeostasis-associated gene (Enho) that is highly expressed in the brain. Aging and stroke are associated with reduced adropin levels in the brain and plasma. We showed that treatment with synthetic adropin provides long-lasting neuroprotection in permanent ischemic stroke. However, it is unknown whether the protective effects of adropin are observed in aged animals following cerebral ischemia/reperfusion. We hypothesized that adropin provides neuroprotection in aged mice subjected to transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO).

Methods:

Aged (18–24 months old) male mice were subjected to 30 min of MCAO followed by 48h or 14 days of reperfusion. Sensorimotor (weight grip test and open field) and cognitive tests (Y-maze and novel object recognition) were performed at defined time points. Infarct volume was quantified by TTC staining at 48h or Cresyl violet staining at 14 days post-MCAO. Blood-brain barrier (BBB) damage, tight junction proteins, and matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) were assessed 48h after MCAO by ELISA and Western blots.

Results:

Genetic deletion of Enho significantly increased infarct volume and worsened neurological function, while overexpression of adropin dramatically reduced stroke volume compared to wild-type controls. Post-ischemic treatment with synthetic adropin peptide given at the onset of reperfusion markedly reduced infarct volume, brain edema, and significantly improved locomotor function and muscular strength at 48h. Delayed adropin treatment (4h after the stroke onset) reduced body weight loss, infarct volume, and muscular strength dysfunction, and improved long-term cognitive function. Post-ischemic adropin treatment significantly reduced BBB damage. This effect was associated with reduced MMP-9 and preservation of tight junction proteins by adropin treatment.

Conclusions:

These data unveil a promising neuroprotective role of adropin in the aged brain after transient ischemic stroke via reducing neurovascular damage. These findings suggest that post-stroke adropin therapy is a potential strategy to minimize brain injury and improve functional recovery in ischemic stroke patients.

Keywords: blood-brain barrier, adropin, ischemic stroke, aged mice, matrix metalloproteinase-9

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Stroke is the second-leading cause of death and the first leading cause of disability in people over 40 years old. Due to the aging of the population, stroke incidence is expected to increase significantly worldwide.1 Timely mechanical thrombectomy and intravenous thrombolysis with tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), the only FDA-approved pharmacological therapy, are the only options for acute stroke interventions in the clinical setting. However, only a small percentage of stroke patients are eligible to receive tPA treatment due to a narrow therapeutic time window.2 Similarly, mechanical clot removal must be performed in a timely manner to be beneficial and is associated with complications such as arterial wall damage and vessel perforation, resulting in intracranial hemorrhage, which limits its application to a relatively small percentage of stroke patients with large vessel occlusions.

Even in successfully recanalized patients, a progressive increase in brain injury is associated with reperfusion. Breakdown of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) after ischemic stroke is a critical pathological process resulting in vasogenic edema and worsening of ischemic stroke outcomes.3 Thus, there is an urgent need to develop novel therapeutic strategies to preserve neurovascular integrity in ischemic stroke treatment.

Adropin is a peptide encoded by the energy homeostasis-associated gene (Enho).4 It is highly expressed in the brain5,6 and has been shown to preserve endothelial barrier function.6,7 Aging or ischemic stroke are associated with reduced levels of adropin in the brain or plasma in rodents6,8 and humans9,10. Our recent findings revealed that genetic deletion of Enho exacerbated ischemic brain injury, while transgenic overexpression of adropin or treatment with synthetic adropin peptide provided long-lasting neuroprotection following permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion (pMCAO).6 Despite the pMCAO animal model representing the majority of clinical stroke cases,11 it is still of great clinical importance to further explore the potential effects of adropin in aged animals following transient MCAO since reperfusion, either occurring spontaneously or following recanalization therapies, happens in stroke patients.

While several potential neuroprotective agents have shown beneficial effects in rodent stroke models, they have failed to translate into a clinical setting. Although several factors explain this translational roadblock, the use of young, healthy animals that are not representative of the clinical stroke patient cohorts is one of the main reasons for the inability to translate basic stroke research into effective stroke therapeutics. Aging is a critical determinant of the brain’s susceptibility to ischemia and dramatically impacts functional recovery after ischemic stroke. Since aging is the chief risk factor for ischemic stroke, the present study was performed exclusively utilizing aged animals to increase the translational relevance of our findings.

In this study, we hypothesized that adropin provides neuroprotection in aged mice subjected to transient MCAO. Utilizing loss- and gain-of-function genetic approaches combined with pharmacological treatment with synthetic adropin peptide, we investigated the effects of adropin on brain infarction and neurological function. Mechanistically, we investigated the impact of adropin on BBB function following ischemic brain injury.

Methods

The original data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. A detailed description of all experimental procedures was provided in the online Supplemental Material. A brief description of the main methodology is provided below.

Animals, MCAO Model, and Adropin Treatment

All animal procedures were approved by the University of Florida Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol # 201907934) and performed in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and the ARRIVE guidelines 2.0.12 Eighteen- to 24-month-old male C57BL/6 (obtained from National Institute on Aging), adropin deficient (Enho−/−)13, transgenic overexpression of adropin (AdrTg)4, and their corresponding wild-type control mice (Enho+/+, the control littermates to Enho−/−; WT, the control littermates to AdrTg) were used in this study. An a priori sample size calculation was performed using the G*Power v.3.1 software and detailed in the Methods section in the online Supplemental Material. Twenty mice per group were assigned to receive stroke surgery. Transient focal cerebral ischemia was induced by intraluminal occlusion of the right middle cerebral artery (MCAO) for 30 min, as previously described by our group.14 We strictly monitored CBF in all mice included in the study and found no differences in CBF values between genotypes or treatment groups (Figure S1). Sham-operated animals received the same surgical procedures except for the MCA occlusion. For the treatment with vehicle or adropin, mice were injected with a single dose of vehicle (0.1% BSA in saline) or synthetic adropin peptide (900 nmol/kg; i.v.) at the start of reperfusion or 4 hours after the onset of cerebral ischemia. In aged mice, this model results in about 40% mortality within 48 hours after MCAO and about 50% mortality within 14 days. There were no statistical differences in mortality between genotypes or treatment groups. A total of 160 aged male mice were used for our MCAO experiments, and 10 mice (5 males and 5 females) were used to compare brain adropin levels between the sexes. Before the endpoint of the experiments, 61 mice died, and 3 mice were excluded at the time of euthanasia (one had a subarachnoid hemorrhage, and two had abdominal tumors).

Measurement of Brain Infarction and Edema

Brain infarction at 48h and 14 days after stroke was measured by 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) staining and Cresyl violet staining, respectively, as described previously6 and detailed in the extended Methods section in the online Supplemental Material.

Neurobehavioral Tests

The open field6 and weight grip test15 were performed to assess locomotor function and muscular strength of forepaws before (baseline) and at several defined time points (48h, 7d, and 14d) post-MCAO. The Y-maze16 and novel object recognition (NOR) test6 were used to assess spatial memory and cognitive function on day 14 after stroke, respectively. See Supplemental Material for details.

Protein Extraction and Immunoblotting

Proteins were extracted from brain homogenates as previously described6, and 50 μg of protein were separated on 4–20% SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Details of the immunoblotting technique, antibody incubations, and signal detection are provided in the extended Methods section in the online Supplemental Material.

ELISAs

The permeability of the BBB was examined by the extravasation of immunoglobulin G (IgG) and albumin from the blood into the brain parenchyma using commercial ELISA kits (Cat. Nos. E90–131 and E99–134, respectively; Bethyl Laboratories, Inc., Montgomery, TX) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and detailed in the extended Methods section in the online Supplemental Material.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism version 6 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Statistical comparison of the means between two groups was performed by unpaired Student’s t-test (parametric) or Mann-Whitney test (nonparametric). Differences in means among multiple groups were accomplished by one-way or two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test. Values were expressed as mean ± SEM, and a p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Genetic deficiency of Enho exacerbates brain infarction and neurological deficits, while transgenic overexpression of adropin attenuates brain damage in aged mice after ischemic stroke

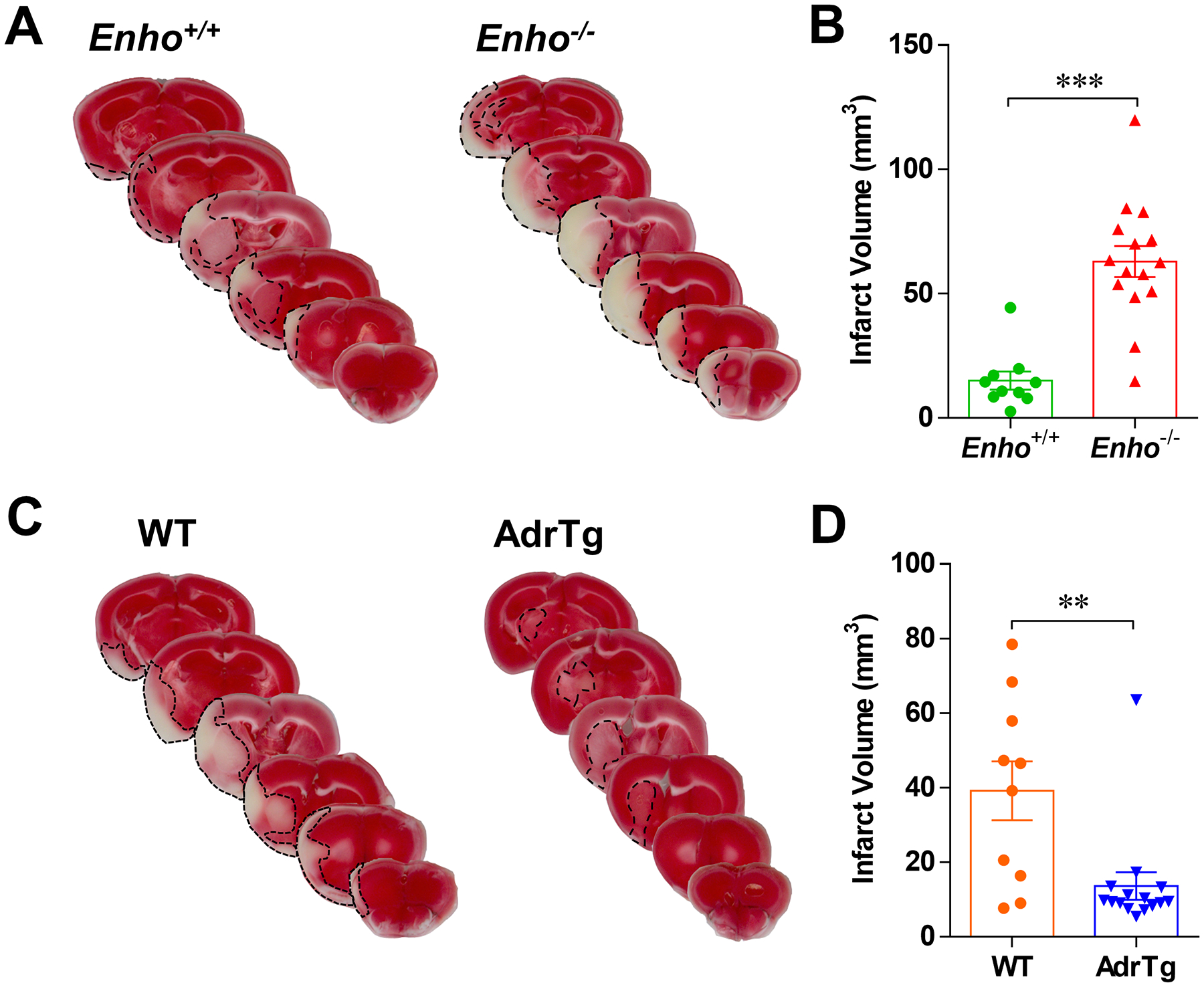

We and others have shown that adropin is highly expressed in the brain,4–6, with no differences in expression levels between sexes (Figure S2). Genetic deletion of Enho exacerbates brain injury, while transgenic overexpression of adropin exerts neuroprotection in mice following pMCAO.6 To further explore the role of adropin in clinically relevant stroke conditions such as spontaneous reperfusion or therapeutic recanalization, we assessed the effects of adropin on stroke outcomes in mice subjected to transient MCAO. Global deficiency of the Enho gene (Enho−/−) in aged (18–24 months) male mice resulted in a significant increase in brain infarct volume compared to aged-matched Enho+/+ controls (Figure 1A and 1B), while transgenic overexpression of adropin (AdrTg) resulted in a smaller brain infarction at 48h post-MCAO than the corresponding WT littermates (Figure 1C and 1D). Notably, brain infarct volume in the Enho+/+ mice (the control littermates to Enho−/−) was smaller compared to the WT animals (the control littermates to AdrTg) (Figure 1B and 1D). These differences in total infarct volume between the control groups might be due to different genetic backgrounds. In this study, the heterozygous adropin-deficient (Enho+/−) mice were generated by crossing C57BL/6-Enhotm1Butl mice with B6.FVB-Tgn(EIIa-Cre)C5379Lmgd mice. Heterozygous carriers of the null allele (C57BL/6- Enhotm1.1Butl, hereafter called Enho+/−) were mated to produce homozygous adropin-deficient (Enho−/−) mice, and the Enho+/+ control littermates.13 However, the AdrTg mice and the corresponding WT controls are on the C57BL/6J background. Strain background differences could result in different infarct volumes in aged Enho+/+ and WT mice following transient MCAO. Compared to the Enho+/+ mice, Enho deficiency significantly reduced grip strength score (where a higher score correlates with a better grip strength) (Figure 2B) and exploratory locomotor function (Figure 2C) as well as altered anxiety-related behavior (assessed by the time spent in the center of the arena) (Figure S3) at 48h after stroke as assessed by the weight grip test and open field test, respectively. There was no significant difference in functional recovery between WT and AdrTg mice, as the grip strength and motor function were impaired, while no significant anxiety-related behavior was observed in these two strains at 48h after MCAO (Figure 2B, Figure 2D, and Figure S3).

Figure 1. Effects of endogenous adropin on infarct volume in aged mice after transient ischemic stroke.

Aged (18–24 months) male mice were subjected to 30 min of transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (tMCAO) followed by 48 hours of reperfusion. Representative images of TTC-stained brain sections and graphical data show that deficiency of the Enho gene resulted in a significant increase in brain infarct volume compared to Enho+/+ controls (A, B). In contrast, transgenic overexpression of adropin (AdrTg) resulted in a smaller brain infarction than the WT littermates (C, D). Unpaired t-test, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. Enho+/+ (n=10), Enho−/− (n=15), WT (n=10), AdrTg (n=15).

Figure 2. Effects of endogenous adropin on neurobehavioral outcomes in aged mice after transient ischemic stroke.

Neurobehavioral tests were performed before (baseline) and 48h after 30 min of MCAO. A schematic illustration of the weight grip test used to measure muscular strength (A, B). Enho deficiency significantly reduced the score (higher score means better grip strength) for mice to grab and lift various weights compared to Enho+/+ controls, while no significant difference was observed in grip strength score between WT and AdrTg mice at 48h after MCAO. Mann-Whitney test, *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. C-D, Locomotor function was assessed by the open field test. Graphical data and representative tracking maps with corresponding heat maps of time spent per location in the open field chamber show that Enho−/− mice had a worse motor function recovery in total distance traveled and travel speed after MCAO than Enho+/+ animals (C). In contrast, there was no significant difference in total distance traveled or travel speed between WT and AdrTg mice (D). Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-tests. *P<0.05 and ***P<0.001. Enho+/+ (n=10), Enho−/− (n=15), WT (n=10), AdrTg (n=15).

Post-stroke treatment with synthetic adropin peptide reduces infarct volume and brain edema and improves neurological deficits in aged mice

Next, we assessed the effects of synthetic adropin peptide on infarct volume, brain edema, and neurological functions in mice subjected to transient MCAO. Post-ischemic treatment with adropin at the start of reperfusion significantly reduced cortical and subcortical infarct volume (Figures 3B and 3C). Also, brain edema formation was significantly reduced by adropin treatment compared to the vehicle group (Figure 3D). Notably, adropin-treated mice exhibited better grip strength (Figure 4A) and superior recovery of motor function (Figure 4B, 4C, and 4D), while no obvious anxiety-related behavior was observed at 48h after stroke compared to the vehicle controls (Figure S3). Collectively, these data strongly suggest that synthetic adropin peptide has protective effects on reducing infarct volume, decreasing brain edema, and improving neurological deficits in a clinically relevant ischemic stroke model in aged mice.

Figure 3. Post-ischemic treatment with synthetic adropin peptide reduces infarct volume and brain edema in aged mice after transient ischemic stroke.

Schematic drawings of the intraluminal filament MCAO surgery and the experimental timeline (A). Representative images of TTC-stained brain sections and graphical data show that adropin treatment significantly reduced infarct volume in the cerebral cortex, striatum, and whole hemisphere (B). Analysis of infarct area per 1-mm slice shows that the decrease in brain infarction by adropin treatment was seen throughout the cortex, and the area of infarct in the striatal slices 5 and 6 from adropin-treated mice were significantly smaller than the slices from vehicle animals (C). The area of the ipsilateral and contralateral hemispheres from a total of six coronal sections was measured, and brain edema was expressed as a ratio of the area of the ipsilateral hemisphere/contralateral hemisphere. Mice receiving adropin peptide show a much smaller brain edema formation than the vehicle animals (D). Unpaired t-test for panels B (ii) and D, and two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-tests for panel C. **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. Vehicle (n=14), Adropin (n=11).

Figure 4. Post-ischemic treatment with synthetic adropin peptide improves neurological function in aged mice after transient ischemic stroke.

Adropin treatment significantly improved grip strength 48h after stroke compared to vehicle animals (A). Mann-Whitney test, *P<0.05 and ***P<0.001. Graphical data and representative tracking maps with corresponding heat maps of time spent per location in the open field chamber show that adropin-treated mice recovered much better in total distance traveled and travel speed after MCAO than vehicle animals (B-D). Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-tests. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. Vehicle (n=14), Adropin (n=11).

Delayed treatment with synthetic adropin peptide reduces infarct volume and improves long-term neurological impairments in aged mice after ischemic stroke

To further determine the efficacy of adropin in the treatment of ischemic stroke in clinically relevant settings, we delayed the adropin treatment for 4h after the onset of cerebral ischemia and evaluated its long-term effects on neurological deficits induced by stroke in aged mice (Figure 5A). As shown in Figure 5B, delayed treatment with adropin consistently reduced brain infarction 14 days after stroke assessed by Cresyl violet staining. Compared to the vehicle-treated mice, adropin treatment attenuated the body weight loss on days 7 and 14 after stroke (Figure 5C). Although stroke induced locomotor function impairment, there was no significant difference in the total distance traveled or the time spent in the center of the behavioral chamber over 14 days between vehicle- and adropin-treated mice, but adropin-treated mice exhibited better recovery in grip strength function at 48h after stroke compared to vehicle animals (Figure 5D and Figure S3). Notably, Y-maze and NOR tests revealed that adropin-treated mice displayed a much better recovery in spatial memory function and long-term recognition memory performance at 14 days after stroke compared to the animals given the vehicle (Figures 5E and 5F). Collectively, these data strongly suggest that adropin has promising protective effects on reducing infarct volume and improving long-term neurological deficits in ischemic stroke.

Figure 5. Delayed treatment with synthetic adropin peptide reduces infarct volume and improves long-term neurobehavioral outcomes in aged mice after ischemic stroke.

A, Experimental timeline for aged (18–24 months) mice subjected to 30 min of MCAO followed by 14 days reperfusion. Mice received one bolus injection of vehicle or synthetic adropin peptide (900 nmol/kg; i.v.) via the retro-orbital venous sinus at 4h after cerebral ischemia, and behavioral tests were performed at defined time points. B, Representative images of Cresyl violet-stained brain sections and graphical data show that delayed adropin treatment reduced brain infarct volume. Unpaired t-test. C, Body weight loss was observed over 14 days after stroke, and adropin treatment significantly attenuated it at day 7 compared to vehicle-treated mice. Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-tests, **P<0.01. D, There was no significant difference in the total distance traveled over 14 days between vehicle- and adropin-treated groups. However, mice given adropin exhibited better recovery in grip strength function at 48h after stroke compared to vehicle animals. Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-tests for the open field test and Mann-Whitney test for the weight grip test, **P<0.01. E, Spatial memory function was assessed by Y-maze. Graphical data and representative tracking paths with corresponding heatmaps show that adropin-treated mice displayed a significant increase in the exploration time in the novel arm compared to the vehicle animals at 14 days after stroke. Unpaired t-test, *P<0.05. F, Cognitive function was evaluated by novel object recognition (NOR) test. Graphical data, representative tracking paths, and heatmaps show that adropin-treated mice had better recovery in long-term recognition memory performance than the vehicle group. Unpaired t-test. Vehicle (n=9), Adropin (n=12).

Post-stroke treatment with synthetic adropin peptide reduces neurovascular injury and MMP-9 activation in the ischemic brain

To explore the possible mechanisms of neuroprotection by adropin in the aged ischemic brain, we investigated the effects of adropin on stroke-induced BBB opening since adropin has been shown to preserve endothelial barrier integrity in vitro and in vivo.6,7,17 As shown in Figures 6A and 6B, stroke resulted in a significant increase of IgG and albumin extravasation, two sensitive markers of BBB disruption, into the ischemic brain, while adropin treatment dramatically reduced the observed extravasation of these plasma proteins. Further findings revealed that adropin treatment attenuated the stroke-induced loss of structural components of BBB in the ischemic cerebral cortex, as seen by an increase of zona occludens (ZO)-1 and a dramatic increase of occludin (Figure 6C). Because increased MMP-9 activation after stroke is a crucial mediator of BBB disruption,18 we next measured MMP-9 levels in the ischemic cortex of sham-, vehicle- and adropin-treated mice. Stroke significantly increased MMP-9 levels of both the pro- and active forms, which were attenuated by adropin treatment (Figure 6D). Taken together, these findings suggest that adropin mediates neuroprotection, possibly by reducing MMP-9-mediated proteolysis of BBB structural components in ischemic stroke.

Figure 6. Post-ischemic treatment with synthetic adropin peptide reduces neurovascular injury and MMP-9 activation in the ischemic brain.

Aged (18–24 months) male mice received one bolus injection of vehicle or synthetic adropin peptide (900 nmol/kg; i.v.) at the start of reperfusion and were euthanized at 48h post-MCAO, cerebral cortex and striatum from ipsilateral and contralateral sides were collected for molecular analysis. Stroke significantly increased the extravasation of plasma proteins IgG (A) and albumin (B) into the ischemic cerebral cortex or striatum, and adropin treatment dramatically reduced the observed extravasation of these plasma proteins. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test, *P<0.05 and **P<0.01. C, Representative Western blots and densitometric analysis show that stroke resulted in a dramatic degradation of tight junction proteins zona occludens (ZO)-1 and occludin in the ischemic cerebral cortex, and adropin treatment slightly prevented the loss of ZO-1 and significantly reduced the loss of occludin. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test, *P<0.05 and ***P<0.001. D, Representative Western blots and densitometric analysis show that stroke significantly increased MMP-9 levels of pro- and active forms in the ischemic cerebral cortex and that adropin treatment significantly reduced MMP-9 levels. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test, *P<0.05. Sham (n=4), Vehicle (n=14), Adropin (n=11).

Discussion

This study demonstrates the neuroprotective effects of adropin in a preclinical model of ischemic stroke in aged mice utilizing loss- and gain-of-function genetic approaches combined with pharmacological treatment with synthetic adropin peptide. The main findings are (1) genetic deletion of Enho enlarges brain infarction and worsens neurological function while transgenic overexpression of adropin improves stroke outcomes following transient MCAO; (2) post-ischemic treatment with synthetic adropin peptide reduces infarct volume, brain edema and improves neurological deficits after stroke; (3) delayed treatment with adropin reduces body weight loss, brain injury, muscular strength dysfunction and improves long-term cognitive function after stroke; (4) adropin treatment reduces BBB damage, degradation of tight junction proteins and MMP-9 levels in the ischemic brain. These results suggest that adropin exerts beneficial effects on cerebral ischemia, and adropin could be used to treat ischemic stroke.

Age is a critical, nonmodifiable risk factor for stroke incidence and post-stroke mortality.19 Our recent findings demonstrated that age is consistently associated with reduced levels of adropin in the brain and plasma in rats8 and humans.9 Reduced levels of adropin were observed in the ischemic mouse brain and plasma,6 and serum adropin levels were significantly lower in stroke patients than those in healthy individuals,10 suggesting that adropin might modulate stroke outcomes. In line with this point, our recent findings revealed that genetic deletion of adropin exacerbates brain injury. In contrast, transgenic overexpression of adropin or synthetic adropin treatment provides long-term neuroprotection by reducing stroke volume and improving neurological function recovery in young and aged mice following pMCAO.6 Considering that reperfusion injury occurs in stroke patients, the current study sought to further explore the potential protective effects of adropin in a transient ischemic stroke model, which would lend further support to the potential value of adropin as a neuroprotectant. Consistent with our findings in the permanent stroke model, genetic deletion of Enho enlarged brain infarction and worsened neurological function while transgenic overexpression of adropin improved stroke outcomes in aged mice following transient MCAO. Importantly, post-ischemic treatment with synthetic adropin peptide reduced infarct volume and brain edema and improved neurological deficits in old mice after MCAO. In addition to the findings that treatment with adropin at the onset of reperfusion exhibits beneficial effects on stroke outcomes in the early phase (48h), our results further revealed that delayed adropin treatment starting at 4 hours after the stroke onset also exerts robust protection as demonstrated by reduced body weight loss, infarct volume, and muscular strength dysfunction. Importantly, delayed adropin administration improved long-term cognitive function in aged mice after transient MCAO. These findings strongly indicate the efficacy of adropin in treating ischemic stroke, suggesting that this peptide can be considered a potential therapeutic strategy to minimize brain injury and improve functional recovery in ischemic stroke patients.

BBB disruption is a pathophysiological event in ischemic stroke that facilitates blood-derived inflammatory cells such as neutrophils to infiltrate into the ischemic brain. The release of neuroinflammatory mediators, including cytokines, chemokines, and MMPs from the activated inflammatory cells, further triggers the injury cascade, resulting in neuronal cell death and exacerbating the damage to the ischemic brain.20 In this study, we found that stroke induced a significant increase of IgG and albumin extravasation, two sensitive markers of BBB disruption, into the ischemic brain, and that adropin treatment dramatically reduced the observed extravasation of these two plasma proteins. These findings are consistent with previous reports that adropin exerts beneficial effects on the preservation of endothelial barrier function in ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke.6,7 Further results revealed that adropin treatment attenuated the stroke-induced loss of structural components of the BBB in the ischemic cerebral cortex, as seen by an increase of ZO-1 and a dramatic increase in occludin levels.

MMP-9 is an important gelatinase that belongs to the MMP family involved in the degradation of tight junction proteins and the extracellular matrix, which is upregulated in ischemic conditions and greatly contributes to BBB disruption.18 We found that stroke significantly increased MMP-9 levels in both pro- and active forms, and these increases were markedly reduced by adropin treatment. Notably, our recent study revealed that adropin treatment dramatically attenuated MMP-9 activation in the ischemic cortex induced by pMCAO, which was associated with decreased levels of neutrophil infiltration and oxidative stress.6 Oxidative stress21,22 and infiltrating neutrophils23,24 are essential contributors to the production and activation of MMP-9, a crucial protease that leads to BBB damage in cerebral ischemia. As a key enzyme responsible for superoxide (O2−.) generation, gp91phox-containing NADPH oxidase (NOX2) was found to be dramatically upregulated in the ischemic mouse brain, associated with remarkable increases in MMP-9 protein levels and enzymatic activity, and the MMP-9 increase was mostly abolished in gp91phox deficient mice.25 We recently reported that post-ischemic treatment with adropin dramatically reduced the stroke-induced increases in MMP-9 activity, neutrophil infiltration, and oxidative stress markers such as gp91phox and 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE, a lipid peroxidation product) in the ischemic mouse brain at 24h after pMCAO.6 High levels of peroxynitrite (ONOO−), formed by the reaction between O2−. and nitric oxide (NO), can S-nitrosylate the cysteine residue in the conserved autoinhibitory region of pro-MMP-9 (inactive form) to form active MMP-9 by a mechanism known as the “cysteine switch”.26 Thus, reduced levels of gp91phox in adropin-treated mice, potentially limits the formation of ONOO−, which in turn increases the NO bioavailability and decreases MMP-9 activity in the ischemic brain. Based on these observations, reduced MMP-9 activation by adropin treatment in ischemic stroke may be regulated by the decreased oxidative stress and/or neutrophil infiltration. Additional studies to investigate how adropin attenuates MMP-9 activation, thus resulting in neurovascular protection, would be needed to fully understand the molecular mechanisms through which adropin protects the ischemic brain.

One of the limitations of the current study is that we did not directly measure MMP-9 activity using either gelatin zymography or fluorometric immunocapture assay,27 which would have provided true MMP-9 enzymatic activity. However, we have found that the levels of active MMP-9 form measured by immunoblotting show a positive correlation with the MMP-9 activity in the ischemic mouse brain.6 It will be important to confirm the inhibitory effects of adropin on MMP-9 activity and unveil how MMP-9 is regulated by adropin in the aged mouse brain following ischemic stroke in future studies.

In summary, our findings provide strong evidence that adropin protects against cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury in aged mice, suggesting that adropin may be a promising therapy to improve stroke outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by grants R01NS103094 and R01NS109816 from the NINDS/NIH to ECJ, grant R21NS108138 to AAB, and a Postdoctoral Fellowship from the McKnight Brain Institute, University of Florida, to CY.

Non-Standard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- Enho

energy homeostasis-associated gene

- MCAO

middle cerebral artery occlusion

- pMCAO

permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion

- TTC

2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride

- BBB

blood-brain barrier

- MMP-9

matrix metalloproteinase-9

- Enho −/−

adropin deficient

- AdrTg

transgenic overexpression of adropin

- Enho +/+

control littermates to Enho−/−

- WT

control littermates to AdrTg

- tPA

tissue plasminogen activator

- MCA

middle cerebral artery

- CCA

common carotid artery

- ECA

external carotid artery

- ICA

internal carotid artery

- CBF

cerebral blood flow

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PFA

paraformaldehyde

- NOR

novel object recognition

- IgG

immunoglobulin G

- ZO-1

zona occludens-1

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Collaborators GBDN. Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18:459–480. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30499-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fonarow GC, Smith EE, Saver JL, Reeves MJ, Bhatt DL, Grau-Sepulveda MV, Olson DM, Hernandez AF, Peterson ED, Schwamm LH. Timeliness of tissue-type plasminogen activator therapy in acute ischemic stroke: patient characteristics, hospital factors, and outcomes associated with door-to-needle times within 60 minutes. Circulation. 2011;123:750–758. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.974675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang Y, Rosenberg GA. Blood-brain barrier breakdown in acute and chronic cerebrovascular disease. Stroke. 2011;42:3323–3328. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.608257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumar KG, Trevaskis JL, Lam DD, Sutton GM, Koza RA, Chouljenko VN, Kousoulas KG, Rogers PM, Kesterson RA, Thearle M, et al. Identification of adropin as a secreted factor linking dietary macronutrient intake with energy homeostasis and lipid metabolism. Cell Metab. 2008;8:468–481. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.10.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong CM, Wang Y, Lee JT, Huang Z, Wu D, Xu A, Lam KS. Adropin is a brain membrane-bound protein regulating physical activity via the NB-3/Notch signaling pathway in mice. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:25976–25986. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.576058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang C, Lavayen BP, Liu L, Sanz BD, DeMars KM, Larochelle J, Pompilus M, Febo M, Sun YY, Kuo YM, et al. Neurovascular protection by adropin in experimental ischemic stroke through an endothelial nitric oxide synthase-dependent mechanism. Redox Biol. 2021;48:102197. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2021.102197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu L, Lu Z, Burchell S, Nowrangi D, Manaenko A, Li X, Xu Y, Xu N, Tang J, Dai H, et al. Adropin preserves the blood-brain barrier through a Notch1/Hes1 pathway after intracerebral hemorrhage in mice. J Neurochem. 2017;143:750–760. doi: 10.1111/jnc.14238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang C, DeMars KM, Candelario-Jalil E. Age-Dependent Decrease in Adropin is Associated with Reduced Levels of Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase and Increased Oxidative Stress in the Rat Brain. Aging Dis. 2018;9:322–330. doi: 10.14336/AD.2017.0523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butler AA, Tam CS, Stanhope KL, Wolfe BM, Ali MR, O’Keeffe M, St-Onge MP, Ravussin E, Havel PJ. Low circulating adropin concentrations with obesity and aging correlate with risk factors for metabolic disease and increase after gastric bypass surgery in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:3783–3791. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-2194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gunaydin M, Aygun A, Usta M, Vural A, Ozsahin F. Serum adropin levels in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Medicine Science. 2019;8:698–702. doi: 10.1002/hipo.23403 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McBride DW, Zhang JH. Precision Stroke Animal Models: the Permanent MCAO Model Should Be the Primary Model, Not Transient MCAO. Transl Stroke Res. 2017. doi: 10.1007/s12975-017-0554-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Percie du Sert N, Hurst V, Ahluwalia A, Alam S, Avey MT, Baker M, Browne WJ, Clark A, Cuthill IC, Dirnagl U, et al. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for reporting animal research. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2020;40:1769–1777. doi: 10.1177/0271678X20943823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ganesh Kumar K, Zhang J, Gao S, Rossi J, McGuinness OP, Halem HH, Culler MD, Mynatt RL, Butler AA. Adropin deficiency is associated with increased adiposity and insulin resistance. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2012;20:1394–1402. doi: 10.1038/oby.2012.31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang C, Yang Y, DeMars KM, Rosenberg GA, Candelario-Jalil E. Genetic Deletion or Pharmacological Inhibition of Cyclooxygenase-2 Reduces Blood-Brain Barrier Damage in Experimental Ischemic Stroke. Front Neurol. 2020;11:887. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deacon RM. Measuring the strength of mice. J Vis Exp. 2013. doi: 10.3791/2610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baratz R, Tweedie D, Wang JY, Rubovitch V, Luo W, Hoffer BJ, Greig NH, Pick CG. Transiently lowering tumor necrosis factor-alpha synthesis ameliorates neuronal cell loss and cognitive impairments induced by minimal traumatic brain injury in mice. J Neuroinflammation. 2015;12:45. doi: 10.1186/s12974-015-0237-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang C, DeMars KM, Hawkins KE, Candelario-Jalil E. Adropin reduces paracellular permeability of rat brain endothelial cells exposed to ischemia-like conditions. Peptides. 2016;81:29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2016.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Candelario-Jalil E, Yang Y, Rosenberg GA. Diverse roles of matrix metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases in neuroinflammation and cerebral ischemia. Neuroscience. 2009;158:983–994. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.06.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boehme AK, Esenwa C, Elkind MS. Stroke Risk Factors, Genetics, and Prevention. Circ Res. 2017;120:472–495. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.308398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang C, Hawkins KE, Dore S, Candelario-Jalil E. Neuroinflammatory mechanisms of blood-brain barrier damage in ischemic stroke. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2019;316:C135–C153. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00136.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haorah J, Ramirez SH, Schall K, Smith D, Pandya R, Persidsky Y. Oxidative stress activates protein tyrosine kinase and matrix metalloproteinases leading to blood-brain barrier dysfunction. J Neurochem. 2007;101:566–576. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04393.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gasche Y, Copin JC, Sugawara T, Fujimura M, Chan PH. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibition prevents oxidative stress-associated blood-brain barrier disruption after transient focal cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21:1393–1400. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200112000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Justicia C, Panes J, Sole S, Cervera A, Deulofeu R, Chamorro A, Planas AM. Neutrophil infiltration increases matrix metalloproteinase-9 in the ischemic brain after occlusion/reperfusion of the middle cerebral artery in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23:1430–1440. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000090680.07515.C8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gidday JM, Gasche YG, Copin JC, Shah AR, Perez RS, Shapiro SD, Chan PH, Park TS. Leukocyte-derived matrix metalloproteinase-9 mediates blood-brain barrier breakdown and is proinflammatory after transient focal cerebral ischemia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H558–568. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01275.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu W, Chen Q, Liu J, Liu KJ. Normobaric hyperoxia protects the blood brain barrier through inhibiting Nox2 containing NADPH oxidase in ischemic stroke. Med Gas Res. 2011;1:22. doi: 10.1186/2045-9912-1-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gu Z, Kaul M, Yan B, Kridel SJ, Cui J, Strongin A, Smith JW, Liddington RC, Lipton SA. S-nitrosylation of matrix metalloproteinases: signaling pathway to neuronal cell death. Science. 2002;297:1186–1190. doi: 10.1126/science.1073634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hawkins KE, DeMars KM, Yang C, Rosenberg GA, Candelario-Jalil E. Fluorometric immunocapture assay for the specific measurement of matrix metalloproteinase-9 activity in biological samples: application to brain and plasma from rats with ischemic stroke. Mol Brain. 2013;6:14. doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-6-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.