Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has presented a global challenge for anticipating the support and treatment needs of bereaved individuals. However, no studies have examined how mourners have been coping with grief and which strategies may buffer negative mental health consequences. We examined the various coping strategies being used and which strategies best support quality of life. Participants completed self-report measures of demographic and loss-related characteristics, grief symptoms, quality of life (QOL), and coping strategies used. Despite help-seeking being one of the least endorsed coping strategies used, help-seeking was the only coping strategy that buffered the impact of grief on QOL for individuals with high grief severity. Results support predictions that grief may become a global mental health concern requiring increased accessibility and availability of grief therapies and professional supports for bereaved individuals during and in the aftermath of the pandemic.

Keywords: COVID-19, grief, bereavement , quality of life, coping, help-seeking

As of December 2022, there have been over six and a half million confirmed COVID-19 deaths worldwide and over 48,000 in Canada alone, leaving an alarming number of bereaved individuals in the wake of the pandemic (Government of Statistics Canada, 2022; World Health Organization, 2022). It is estimated that for every COVID-19 death, approximately nine people will be affected by grief (Verdery et al., 2020), yielding over 60 million individuals bereaved due to COVID-19 based on current worldwide death tolls. A significant rise in non-COVID-19 deaths was also observed in Canada throughout the pandemic (Statistics Canada, 2022) contributing to an unprecedented number of individuals at risk for disturbed grief. In additional to increased deaths, the circumstances of the pandemic have introduced several factors that may interfere with the grief process and consequently intensify grief symptoms for the larger population of bereaved individuals, including death occurring in isolation or missing the last moments of the deceased, reduced opportunity for mourning rituals due to social distancing measures, co-occurrence of multiple secondary stressors (e.g., social isolation, financial strain), and reduced access to social support and therapeutic services (Eisma & Boelen, 2021; Hamid & Jahangir, 2020; World Health Organization, 2020). For example, in Ontario, government mandates limited the number of people permitted at indoor and outdoor funeral services (10–50 people, respectively) during lock down periods (e.g., March–July 2020 and September–March 2021), forcing individuals to cancel, delay or find alternative solutions, such as virtual services. Conditions surrounding the pandemic have therefore presented a global challenge for anticipating the support and treatment needs of all bereaved individuals, not just those lost to COVID-19 (Bereavement Authority of Ontario, 2020).

Accordingly, researchers, health care professionals, and policy makers have raised significant concerns about the expected rise in prolonged and disabling grief, such as Complicated Grief (CG) or Prolonged Grief Disorder (PGD) during and following the pandemic (e.g., Amy & Doka, 2021; Bertuccio & Runion, 2020; Diolaiuti et al., 2021; Eisma & Boelen, 2021). Sharing similar features to past epidemics and natural disasters (Gesi et al., 2020), the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated several potential risk factors for CG (e.g., the unexpected death of a loved one, social isolation, concomitant stressors; Mayo Clinic, 2021; Piper et al., 2011) leading to increased rates of disabling grief. Although empirical studies are still limited, emerging research has demonstrated elevated levels of grief among Dutch adults who experienced a loss during the pandemic compared to those bereaved before the pandemic (Eisma & Tamminga, 2020). Among Chinese adults, over one third of bereaved individuals met criteria for pathological or complicated grief (Tang & Xiang, 2021) compared to pre-pandemic estimated rates of 10–15%. This is particularly concerning given that CG is associated with a host of other negative mental health outcomes including major depressive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, reduced quality of life, and impairments in social, occupational, and other important areas of functioning (Boelen & Prigerson, 2007; Simon et al., 2007; Stroebe et al., 2007).

In anticipation of the detrimental mental health consequences of grief during and in the aftermath of the pandemic, several calls to action urged clinically oriented researchers to evaluate who may be most at risk for prolonged grief and how we can best support these individuals. Studies have begun to clarify the specific demographic- and loss-related risk factors for more severe grief reactions and related mental health problems, including the experience of an unexpected loss, losing a first-degree relative, having a close and/or conflictual relationship with the deceased, feeling traumatized by the loss, being male and, tentatively, experiencing a non-COVID-19 loss relative to a COVID-19 loss (Eisma et al., 2021; Tang et al., 2021; Tang & Xiang, 2021). While this work sheds light on who may be suffering the most, researchers have yet to evaluate how bereaved individuals are currently coping with their grief, and potential protective factors that may buffer against poor outcomes following a loss during the pandemic.

Given the unique circumstances of the pandemic, such as increased social distancing and reduced access to mental health supports, the process of mourning and coping with grief may be restricted or limited. For example, while greater social support is associated with better grief outcomes, social distancing measures may reduce the positive effects of receiving social support following a loss and potentially worsen grief symptoms (Breen, 2021; Burke et al., 2010; Chen, 2022). Those who live independently or with few people may be particularly at risk of social isolation and may be less able to leverage social support as a coping strategy during the pandemic (Mortazavi et al., 2020; Pietrabissa & Simpson, 2020). Other factors associated with better grief outcomes include greater spirituality and religiousness (Mason et al., 2020), access to grief support groups or mental health treatment (Harrop et al., 2020; Robinson & Pond, 2019), and maintaining an ongoing connection to the deceased while making meaning of the loss (Neimeyer et al., 2006; Root & Exline, 2014). However, at present, there are no quantitative tests or descriptions of how bereaved individuals are coping and if these protective factors are applicable or relevant during the pandemic. Identifying how grievers cope after loss and the strategies that are most helpful during the pandemic is a critical next step given that coping is one of the few grief-related factors that can be targeted by clinical intervention (Stroebe et al., 2006).

Among the possible coping strategies that grievers may use to manage symptoms, researchers and clinicians have voiced specific concerns regarding access and availability of professional help during the pandemic (Amy & Doka, 2021; Eisma et al., 2020; Eisma & Boelen, 2021). Disturbed grief reactions are often best treated with grief-specific support and therapeutic interventions (Harrop et al., 2020; Robinson & Pond, 2019) especially given the significant mental health consequences such as post-traumatic stress, increased suicidal ideation, and significant reductions in overall quality of life (Boelen & Prigerson, 2007; Latham & Prigerson, 2004). In support of the anticipated need for accessible grief treatments (e.g., remotely delivered therapy), it is important to first consider the extent that seeking help is being used as a coping strategy and how it influences grief outcomes during the pandemic. To start identifying how to improve the lives of bereaved individuals, it is important to understand the types of coping strategies this population is using and which strategies provide the most benefit, particularly during a time when individuals may be adapting their coping process to the pandemic context.

The goals of this study were two-fold: First, to describe and evaluate the types of coping strategies being used among individuals who became bereaved during the COVID-19 pandemic. Given that empirical research on grief during the pandemic is still considerably limited, this study also describes acute grief symptoms specifically among bereaved adults, including related demographic- and loss-related risk factors and quality of life (QOL) outcomes. Second, to explore the extent that different coping strategies may buffer individuals from grief symptoms, we also examined how coping may impact associations between grief and QOL. In other words, we examined interactions between grief symptoms and coping to determine who may be benefiting the most, or least, from various methods of coping.

Methods

Participants

A total of 224 participants were included in this study. Participants were recruited through an undergraduate subject pool (n = 159) at a large urban ethnically/culturally-diverse university, the crowdsourcing platform, Prolific (n = 54), and social media platforms such as Linked In, Facebook, and Instagram (n = 11). Prolific is a reliable UK-based crowdsourcing platform designed for academic research ((Palan & Schitter, 2018; Peer et al., 2017), where research advertisements are published to registered participants who meet specific demographic information (e.g., living in Canada) who can then choose to voluntarily participate in research projects for compensation. Participants were required to be at least 16-years of age, to be living within Canada, and to have experienced the loss of a loved one during the COVID-19 pandemic. Some participants (n = 5) recruited through the university subject pool were not residing in Canada at the time of the survey; however, they were actively enrolled in a Canadian University and temporarily relocated due to the pandemic.

Procedure

Ethics approval was obtained by the university’s ethics review board. Participant recruitment followed a two-step method. First, research advertisements were published on each of the recruitment platforms (i.e., social media, Prolific, and the undergraduate subject pool). The advertisement included a public eligibility survey for interested participants (n = 521). Only those who met inclusion criteria in the first survey were asked to complete the study questionnaires (n = 267). The study questionnaires included questions regarding demographics, grief symptoms, QOL, and grief-specific coping strategies. Data was collected and stored via REDCap, a secure, PHIPA-compliant data management software. Prolific participants for this study were compensated £13.70/hr. Participants recruited through the university undergraduate subject pool were compensated in research credits that contribute to their undergraduate degree. Participants recruited through social media did not receive compensation.

Measures

Demographic Questionnaire

During eligibility screening, participants reported on their age, current location, and whether they had experienced the loss of a loved one during the COVID-19 pandemic. Once inclusion criteria were met, further demographic questions were asked around gender identity, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, job status, living arrangements (i.e., who lives in the home with them), and pre-existing mental health diagnoses. Participants were also asked questions regarding their relationship with the deceased person, the nature of the death (i.e., expected vs. unexpected, COVID-19 related vs. non-COVID-19 related), and whether they experienced a loss prior to COVID-19.

Inventory of Complicated Grief-Revised (ICG-R)

The ICG-R (Prigerson et al., 1995) is a 19-item self-report measure that was used to assess maladaptive symptoms after experiencing the loss of a loved one. Participants were asked to rate how often they experienced various symptoms on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = never, 3 = sometimes, 5 = always). The measure covers symptoms consistent with CG and has been widely used as a screening tool for severity of clinically impairing grief. Higher scores indicate greater impairment. A cut-off score of 25 is used to identify clinically significant grief symptoms. The ICG has been demonstrated to be a reliable measure (a = .94; Prigerson et al., 1995). Reliability in this study was also strong (α = .91). While this measure is used to assess symptoms consistent with a diagnosis of CG, the time criteria for CG (6 months post-loss) precluded establishing clinical criteria for diagnosis among those recently bereaved during the pandemic. Therefore, this measure was used to examine levels of acute grief. Acute grief is one of the strongest predictors of the development of complicated grief (Boelen & Lenfeink, 2020) and, for the purposes here, is the most informative method for ascertaining risk for disturbed grief.

Multicultural Quality of Life Index (MQLI)

The MQLI (Mezzich et al., 2011) is a culturally informed measure used to assess an individual’s self-reported QOL. It contains 10-items, each one addressing a unique factor of QOL including physical well-being, psychological and emotional well-being, self-care and independent functioning, occupational functioning, interpersonal functioning, social and emotional support, community and services support, personal fulfillment, spiritual fulfillment, and global perception of QOL. Participants were asked to rate how satisfied they are with each QOL factor on a 10-point scale from poor to excellent. Final scores were obtained by averaging all 10 areas, with higher scores indicating higher QOL. Validation studies have confirmed the MQLI as a reliable measure (α = 0.92). Reliability for this study was comparable (α = .92)

Coping Assessment for Bereavement and Loss Experiences (C.A.B.L.E.)

The C.A.B.L.E. (Crunk et al., 2021) is a 28-item self-report measure that identifies coping strategies bereaved individuals are using to cope with grief. Using a 5-point scale, participants were asked to indicate the frequency (0 = never, 2 = a few times, 4 = daily) they use specific coping strategies. Participants could also select N/A if a strategy was not applicable or indicate any personal coping strategies that were not listed. In addition to a mean score, initial factor analyses of the CABLE in validation studies indicated six distinct types of coping strategies: help-seeking (e.g., I attended grief therapy sessions from a mental health professional), positive outlook (e.g., I reminded myself of my strengths), spiritual support (e.g., I set aside time to talk to God or my Higher Power about my grief), continuing bonds (e.g., I reviewed photos or videos of my loved one), compassionate outreach (e.g., I cared for or nurtured others) and social support (e.g., I reached out to others for comfort and companionship). The higher the score, the more coping strategies an individual is using in this area. Initial psychometric data revealed good internal consistency for overall coping (a = .88) and adequate to good reliability coefficients for all coping factors (a = .65–.87; Crunk et al., 2021). The total coping reliability coefficient in this study was .92, and reliability coefficients for coping factors ranged from .65–.85.

Results

Sample Characteristics

The characteristics of the sample are presented using descriptive statistics. Specifically, we examined various demographic and loss-related characteristics including age, gender identity, ethnicity, education, previous mental health diagnoses, number of additional people living in the home (metric of the degree of social isolation in proceeding analyses), expectedness of the loss, whether the loss was related to COVID-19, and the relationship to the deceased. With respect to the first goal of the study, we describe grief levels, coping strategies used, and QOL among those bereaved during the pandemic. Table 1 summarizes the demographic and loss-related characteristics of the sample.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and Loss-Related Characteristics.

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Gender identity | 222 |

| Man | 151 (68.0) |

| Woman | 68 (30.6) |

| Non-binary | 1 (.5) |

| Other | 2 (.9) |

| Ethnicity | 224 |

| Caucasian | 54 (24.1) |

| First Nation | 2 (.9) |

| Latino/Hispanic | 8 (3.6) |

| Middle Eastern | 23 (10.3) |

| Black | 17 (7.6) |

| Caribbean | 5 (2.2) |

| South Asian | 46 (20.5) |

| East Asian | 19 (8.5) |

| European | 6 (2.7) |

| Mixed ethnicity | 38 (17.0) |

| Other | 6 (2.7) |

| Household income | 217 |

| $0 – $20 k | 48 (22.6) |

| $21 – $40 k | 31 (14.3) |

| $41 – $60 k | 33 (15.2) |

| $61 – $80 k | 32 (14.7) |

| $81 – $100 k | 28 (12.9) |

| $101 k + | 44 (20.3) |

| Pre-existing MH diagnosis | |

| Yes | 42 (18.8) |

| No | 182 (81.3) |

| Expectedness of death | 224 |

| Expected | 64 (28.6) |

| Unexpected | 160 (71.4) |

| Loss related to COVID-19 | 222 |

| Yes | 66 (29.7) |

| No | 156 (70.3) |

| Relationship to the deceased | 211 |

| Parent | 14 (6.6) |

| Sibling | .2 (.9) |

| Grandparent | 85 (40.3) |

| Relative | 68 (32.2) |

| Friend | 38 (18.0) |

| Other | 4 (1.9) |

Demographic and Loss-Related Characteristics

Participants had a mean age of 23.6 years (SD = 7.13), with ages ranging from 17 to 68 years. The majority of participants identified as male (n = 151, 68.0%) with diverse ethnic backgrounds, though the three most-commonly reported were Caucasian (n = 54 24.1%), South Asian (n = 46, 20.5%) and Mixed (n = 38, 17.0%). The number of additional people living in the participant’s home ranged from 0 to 8 (M(SD) = 2.76 (1.49), median = 3). The median annual household income in the sample fell between $41,000–$60,000 CAD. The median education level (outside of the undergraduate subject pool participants) was an undergraduate degree. For participants recruited through the undergraduate subject pool, the median number of completed years was 2. Pre-existing mental health diagnoses were reported in 18.8% of the sample (n = 42).

Most participants reported that the death was unexpected (n = 160, 71.4%) and not related to COVID-19 (n = 156, 70.3%). A majority of the sample lost a grandparent(n = 85, 40.3%), followed by a relative (n = 68, 32.2%), a friend (n = 38, 18.0%), a parent (n = 14, 6.6%), and a sibling (n = 2, .9%). Of the 224 participants included, 36 (16.1%) also experienced a loss within 1 year prior to COVID-19.

Grief Symptoms, Coping Strategies, and Quality of Life

The first main goal of the study was to describe grief symptoms, coping strategies, and QOL among a sample of adults bereaved during the COVID-19 pandemic. Grief symptom levels reported on the ICG-R were M(SD) = 23.93 (13.97) and ranged from 1 to 56, with 45% of the sample (n = 100) reporting clinically significant grief symptoms (>25). Overall QOL scores were M(SD) = 5.97 (1.91) and ranged from 1 to 10. The lowest reported QOL domains were psychological/emotional well-being [M(SD) = 5.25 (2.33)] and personal fulfillment [M(SD) = 5.64 (2.49)]. The highest reported QOL domains were interpersonal functioning [M(SD) = 6.39 (2.31)] and social-emotional support [M(SD) = 6.39 (2.41)]. Average scores on the MQOL were consistent with a clinical population (Mezzich et al., 2011). Overall coping scores were M(SD) = 1.69 (.79) and ranged from .22 to 4.21. The most endorsed coping strategies used were positive outlook [M(SD) = 2.19 (1.01)] and compassionate outreach [M(SD) = 2.66 (.96)] and the least endorsed coping strategies were help-seeking [M(SD) = .96 (1.26)] and social support [M(SD) = 1.64 (.90)]. Means of all study variables, including QOL and coping subscales, are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Means of Study Variables.

| n | M (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Grief symptoms | 222 | 23.93 (13.97) |

| Quality of life | ||

| Overall QOL | 221 | 5.97 (1.91) |

| Physical well-being | 220 | 5.90 (2.21) |

| Psychological/emotional wellbeing | 221 | 5.25 (2.33) |

| Self-care/independent functioning | 220 | 6.22 (2.32) |

| Occupational functioning | 219 | 6.27 (2.48) |

| Interpersonal functioning | 218 | 6.39 (2.31) |

| Social-emotional support | 218 | 6.39 (2.41) |

| Community & services support | 220 | 6.15 (2.52) |

| Personal fulfillment | 219 | 5.64 (2.49) |

| Spiritual fulfillment | 220 | 5.59 (2.68) |

| Global perception of QOL | 219 | 5.78 (2.42) |

| Coping | ||

| Overall coping | 218 | 1.69 (.79) |

| Help seeking | 218 | .96 (1.26) |

| Positive outlook | 218 | 2.19 (1.01) |

| Spiritual support | 218 | 1.71 (1.35) |

| Continuing bonds | 218 | 1.65 (1.05) |

| Compassionate outreach | 212 | 2.66 (.96) |

| Social support | 218 | 1.64 (.90) |

Correlates of Grief Symptoms

With respect to the first goal of the study, we examined how grief symptoms were related to demographic and loss-related characteristics to better understand who may be suffering the most following a loss during the pandemic. Additionally, we examined how grief symptoms were related to bereaved individuals’ use of various coping strategies and their QOL. Bivariate correlations (Table 3), independent samples t-tests, and multiple linear regressions among variables of interest are presented in the following sections.

Table 3.

Bivariate Correlations Among Study Variables.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 21 | 22 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | — | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Household income | .19** | — | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 3. Education | .12 | .13 | — | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 4. Previous MH diagnoses | .03 | .08 | −.51** | — | |||||||||||||||||||

| 5. Grief symptoms (ICG-R) | −.11 | −.16* | −.17 | .08 | — | ||||||||||||||||||

| 6. Mean QOL | .14* | .10 | .19 | −.12 | −.37** | — | |||||||||||||||||

| 7. Physical wb | .11 | .16 | .12 | .08 | −.28** | .78** | — | ||||||||||||||||

| 8. Psych/emotional wb | .17* | .18 | .11 | −.17* | −.35** | .81** | .80** | — | |||||||||||||||

| 9. Self-care/independent fx | .17* | .07 | .06 | −.11 | −.34** | .81** | .69** | .60** | — | ||||||||||||||

| 10. Occupational fx | .16* | .09 | .12 | −.06 | −.35** | .79** | .64** | .58** | .75** | — | |||||||||||||

| 11. Interpersonal fx | .03 | .07 | .09 | −.10 | −.31** | .82** | .56** | .64** | .67** | .70** | — | ||||||||||||

| 12. Social-emotional support | .06 | .01 | .09 | −.09 | −.30** | .79** | .57** | .58** | .56** | .55** | .73** | — | |||||||||||

| 13. Community/services supp | .20** | .10 | .14 | −.03 | −.30** | .76** | .50** | .54** | .49** | .53** | .54** | .64** | — | ||||||||||

| 14. Personal fulfillment | .08 | .13 | .20 | −.09 | −.33** | .85** | .61** | .65** | .64** | .58** | .62** | .64** | .63** | — | |||||||||

| 15. Spiritual fulfillment | .02 | −.01 | .32* | −.08 | −.12 | .66** | .37** | .43** | .43** | .38** | .43** | .41** | .49** | .57** | — | ||||||||

| 16. Global perception of QOL | .13 | .11 | .25* | −.18** | −.33** | .84** | .59** | .66** | .65** | .55** | .60** | .60** | .61** | .76** | .60** | — | |||||||

| 17. Overall coping | −.08 | −.16* | −.30* | .10 | .33** | .03 | −.01 | −.07 | .05 | .02 | .04 | .03 | −.02 | .01 | .15* | .02 | — | ||||||

| 18. Help-seeking | −.11 | −.12 | −.37** | .13* | .22** | −.06 | −.08 | −.08 | −.04 | −.03 | −.01 | −.02 | −.11 | −.06 | .03 | −.09 | .80** | — | |||||

| 19. Positive outlook | .01 | −.14* | −.21 | .03 | .19** | .23** | .19** | .10 | .28** | .23** | .18** | .17* | .11 | .18* | .20** | .22** | .73** | .43** | — | ||||

| 20. Spiritual support | −.04 | −.12 | −.15 | .06 | .20** | −.03 | −.05 | −.07 | −.01 | −.04 | −.07 | −.09 | −.07 | −.06 | .20** | −.03 | .68** | .44** | .35** | — | |||

| 21. Continuing bonds | −.02 | −.15* | −.03 | .01 | .45** | −.09 | −.15* | −.17* | −.12 | −.12 | −.05 | −.03 | −.01 | −.09 | .07 | −.08 | .76** | .48** | .45** | .45** | — | ||

| 22. Compassionate outreach | −.03 | −.01 | −.14 | .00 | .05 | .18** | .20* | .05 | .19** | .16* | .14* | .13 | .14* | .13 | .12 | .17* | .41** | .11 | .36** | .12 | .30** | — | |

| 23. Social support | −.14* | −.09 | −.26* | .14* | .24** | .05 | .04 | −.03 | .05 | −.01 | .09 | .10 | −.01 | .04 | .07 | .03 | .71** | .45** | .55** | .33** | .52** | .32** | — |

MH = mental health, ICG-R = Inventory of Complicated Grief – Revised, QOL = Quality of Life, wb = well-being, fx = functioning. **p < .001, *p < .05.

Demographic and Loss-Related Characteristics

First, we examined how grief symptoms were related to demographic characteristics. Grief levels were negatively correlated with household income (r = −.16, p = .022) such that lower income individuals reported higher levels of grief. Grief symptoms were unrelated to age, gender identity, ethnicity, degree of social isolation, or pre-existing mental health diagnoses. Next, we examined how grief symptoms were related to specific loss-related characteristics including expectedness of the death, whether the loss was COVID-19 related, and relationship to the deceased. Grief levels were higher among individuals who reported the loss as unexpected (M = 25.69, SD = 1.10) versus expected (M = 19.57, SD = 1.67;t = 3.02, p = .003), but did not differ based on whether the loss was related to COVID-19 (t = −1.17, p = .245). A multiple linear regression predicting grief symptoms based on relationship to the deceased was significant (F (5, 203) = 3.70, p = .003, R2 = .08); losing a parent (B = 13.76, t = 3.47, p < .001) or friend (B = 7.83, t = 2.87, p = .005) was related to higher grief symptoms.

Coping and Quality of Life

Next, we examined how grief symptoms were related to individuals’ use of various coping strategies and QOL. Grief levels were positively correlated with total coping (r = 0.33, p < .001) and all coping subscales except compassionate outreach such that those with higher levels of grief also reported using more coping strategies. Grief levels were negatively correlated with overall QOL (r = −0.37, p < .001) and all domains of QOL except spiritual fulfillment. That is, higher levels of grief were related to lower QOL.

Correlates of Coping Strategies Used

With respect to the first goal of the study, we also explored demographic correlates of coping strategies used using bivariate correlations and independent samples t-tests. Younger individuals endorsed more social support coping (r = −.14, p = .04); however, age and degree of social isolation were not related to overall coping or any other specific coping strategy. Females endorsed significantly more coping overall (t = 1.99, p .048) and coping through spiritual support (t = 2.10, p = .04), continuing bonds (t = 2.77, p = .006), and compassionate outreach (t = 2.95, p = .004) compared to males. Males and females endorsed similar levels of coping through having a positive outlook, help-seeking, and social support. Lower income individuals endorsed more coping through having a positive outlook (r −.14, p = .045) and continuing bonds (r = .15, p = .03). Individuals with a pre-existing mental health diagnosis endorsed more coping through help-seeking (t = −1.98, p = .049) and social support (t = −2.13, p = .038) compared to those without a pre-existing mental health diagnosis.

Interactions Between Grief and Coping

The second main goal of the study was to explore interactions between grief symptoms and coping on bereaved individuals’ QOL. Therefore, we examined coping as a moderator linking grief and QOL to determine who may be benefiting the most, or least, from different coping strategies based on grief levels. Annual household income was included as a covariate given prior literature demonstrating associations between socioeconomic status and overall QOL (Choi et al., 2015; Holmes, 2005). Significant interactions (p < .05) were probed for conditional effects at varying levels of grief (−1SD below mean, mean, +1SD above mean reflecting low, moderate, and high grief severity, respectively).

Moderation Analyses

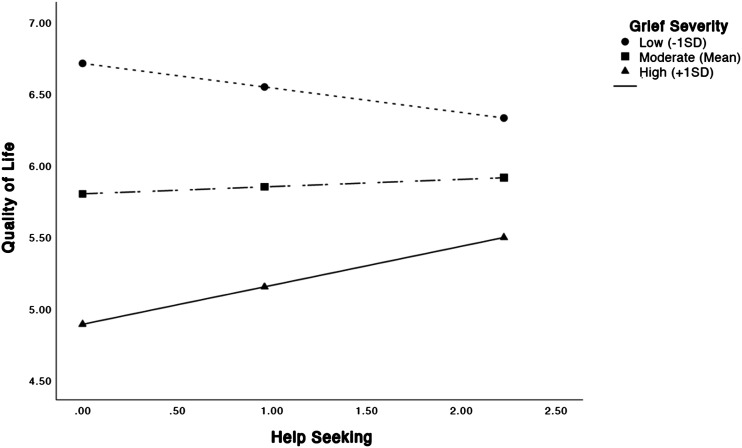

Hayes (2013) PROCESS macro for SPSS was used to examine interactions between grief and coping on bereaved individual’s overall QOL. When examining relationships among total grief symptoms, overall QOL, and overall coping, there was a significant association between grief and QOL (b = −.078, SE = .023, t = −3.46, p < .001, CI: −.12 to −.03) such that those with higher levels of grief symptoms had lower QOL. There was no significant interaction between grief and overall coping (b = .013, SE = .013, t = 1.04, p = .30, CI: −.01 – .04). When considering interactions between grief and specific coping strategies, there was a significant interaction between grief levels and help-seeking on QOL (b = .016, SE = .007, t = 2.15, p = .03, CI: .001–.03). Help-seeking was positively associated with QOL for individuals with high levels of grief (+1SD above mean = 38.22; b = .27, SE = .14, t = 1.98, p = .049, CI: .002–.544). Among individuals with moderate (M = 24.14) or low levels of grief (-1SD below mean = 10.07), help-seeking was unrelated to QOL. In other words, those who endorsed more help-seeking, compared to those who endorsed less, had higher QOL, only among those with high levels of grief. See Figure 1. There were no significant interactions between grief and positive outlook, spiritual support, continuing bonds, compassionate outreach, or social support. Table 4 presents results of all regression analyses.

Figure 1.

Interaction between grief symptoms and help seeking.

Table 4.

Results of Regression Analyses.

| n | F | R2 | b (se) | t | CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | ||||||

| Overall coping | |||||||

| Grief symptoms | 211 | 11.02** | .18 | −.08 (.02) | −3.46* | −.12 | −.03 |

| Overall coping | .12 (.36) | .35 | −.58 | .83 | |||

| Grief x coping | .01 (.01) | 1.04 | −.01 | .04 | |||

| Income | .06 (.07) | .95 | −.07 | .19 | |||

| Help seeking | |||||||

| Grief symptoms | 211 | 9.82** | .16 | −.06 (.01) | −5.78* | −.09 | −.04 |

| Help seeking | −.33 (.21) | −1.58 | −.74 | .08 | |||

| Grief x help seeking | .02 (.01) | 2.15* | .00 | .03 | |||

| Income | .05 (.07) | .81 | −.08 | .19 | |||

| Positive outlook | |||||||

| Grief symptoms | 211 | 17.09** | .25 | −.09 (.02) | −4.21* | −.13 | −.05 |

| Positive outlook | .26 (.24) | 1.09 | −.21 | .74 | |||

| Grief x positive outlook | .01 (.01) | 1.61 | −.00 | .03 | |||

| Income | .07 (.06) | 1.17 | −.05 | .20 | |||

| Spiritual support | |||||||

| Grief symptoms | 211 | 8.65** | .14 | −.06 (.02) | −3.12* | −.08 | −.02 |

| Spiritual support | .12 (.18) | .68 | −.23 | .47 | |||

| Grief x spiritual support | −.00 (.01) | −.18 | −.01 | .01 | |||

| Income | .05 (.07) | .79 | −.08 | .19 | |||

| Continuing bonds | |||||||

| Grief symptoms | 211 | 9.17** | .15 | −.05 (.02) | −2.57* | −.08 | −.01 |

| Continuing bonds | .32 (.24) | 1.32 | −.16 | .80 | |||

| Grief x continuing bonds | −.00 (.01) | −.57 | −.03 | .01 | |||

| Income | .06 (.07) | .87 | −.07 | .19 | |||

| Compassionate outreach | |||||||

| Grief symptoms | 204 | 9.94** | .17 | −.05 (.03) | −2.08* | −.11 | −.00 |

| Compassionate outreach | .30 (.26) | 1.16 | −.21 | .81 | |||

| Grief x compassionate outreach | .00 (.01) | .24 | −.02 | .02 | |||

| Income | .05 (.07) | .75 | −.08 | .18 | |||

| Social support | |||||||

| Grief symptoms | 211 | 10.01** | .16 | −.06 (.02) | −3.74** | −.10 | −.03 |

| Social support | .10 (.30) | .34 | −.01 | .03 | |||

| Grief x social support | .01 (.01) | .79 | −.01 | .03 | |||

| Income | .05 (.07) | .73 | −.08 | .18 | |||

*p < .05, **p < .001.

Discussion

This study adds to a growing body of literature describing grief and associated mental health outcomes among adults bereaved during the COVID-19 pandemic. We first aimed to describe grief symptoms, QOL, and coping to understand who may be suffering the most and how bereaved individuals are currently coping throughout the pandemic. In our sample, 45% of participants reported clinically significant symptoms of acute grief which corresponds with other COVID-19 samples. For example, 49% of Chinese adults bereaved during the pandemic endorsed clinically relevant PGD symptoms (Tang et al., 2021). Given that acute grief is indicative of risk for developing disturbed grief (e.g., CG or PGD; Boelen & Lenfeink, 2020) this high proportion of clinical symptoms lends further support to the documented increases in prevalence of grief disorders during the pandemic (Eisma & Tamminga, 2021; Tang et al., 2021; Tang & Xiang, 2021). In support of efforts to identify who is most at risk for severe grief, we also showed that lower income, unexpectedness of the death, and losing a parent or friend was related to higher levels of grief. These findings correspond with the demographic and loss-related risk factors currently identified in the literature on COVID-19 grief (Eisma et al., 2021; Tang et al., 2021) as well as broader reviews of risk factors for severe grief (Burke & Neimeyer, 2012). Additionally, it further supports the idea that marginalized and low-income communities may be disproportionately impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic (Kantamneni, 2020). Despite concerns that greater social isolation and poor social support during the pandemic may affect bereavement outcomes (Mayland et al., 2020; Mortazavi, 2020), this study did not find a relationship between social isolation and either grief severity or coping. Future studies should consider more direct measures of social isolation as a potential risk factor for poor grief reactions during the pandemic when individuals may have reduced access to social support.

Severe grief poses a significant risk for other mental health problems, including anxiety, depression, and PTSD (Boelen & Prigerson, 2007; Tang et al., 2021). While research tends to focus on concomitant psychopathology, mourners are also at elevated risk for reduced QOL which can broadly impair multiple domains of functioning. In our sample, QOL across the 10 domains assessed were comparable to an adult psychiatric population, ranging from 5.25 to 6.39 on the MQLI (Mezzich et al., 2011). Notably, the lowest reported QOL domain was psychological/emotional well-being (i.e., feeling good, comfortable with self) and personal fulfillment (i.e., experiencing a sense of balance, solidarity, and empowerment). These findings highlight the broad clinical consequences of COVID-19 bereavement that may go undetected with the exclusive focus on associated syndromes like anxiety and depression. Interestingly, the highest reported QOL domains in this sample were interpersonal functioning (i.e., able to respond and relate well to family, friends, and groups) and social-emotional support (i.e., availability of people you can trust and who offer help and comfort). Although QOL in these domains were still clinically relevant (Mezzich et al., 2011), these findings raise questions regarding the mental health impact of reduced social interaction on grievers during the pandemic. It will be important to continue evaluating how bereaved individuals are impacted by reduced social interaction and the extent that they are utilizing and/or benefitting from social support to cope with grief.

A major aim of this study was to describe and examine how bereaved adults are currently coping with grief during the pandemic. Amidst restricted access to professional mental health services, limitations on religious/spiritual death rituals, and reduced social support, early commentaries emphasized that coping with grief may become more difficult among this population of bereaved individuals (e.g., Eisma & Boelen, 2021). To our knowledge, no other studies have empirically examined how grievers are coping during the pandemic or the productiveness of endorsed strategies in supporting grief. In this sample, individuals with higher grief severity endorsed more overall coping and all specific coping strategies except compassionate outreach (i.e., engaging in care and compassion for others). This is promising within the pandemic context, demonstrating that individuals burdened with high levels of grief are still engaging in adaptive cognitive, behavioural, and emotional strategies to manage the stress and challenges associated with the bereavement process. Nonetheless, longitudinal studies may be necessary to understand how coping changes over the course of the pandemic. It is possible that grievers with higher levels of distress will engage in certain coping strategies early in the grief process but that continued engagement in these strategies over time will lead to a reduction in symptoms that may subsequently correspond with an inverse relation between coping and grief severity (Crunk et al., 2021).

In this sample, the most endorsed coping strategies used included having a positive outlook and compassionate outreach, which both refer to emotion-focused coping strategies (i.e., distracting behaviours that reduce negative feelings; Lazarus, 1984) and generally reflect a more avoidant style of coping (Carver et al., 1989). In contrast, the least endorsed coping strategies were help-seeking (e.g., attending therapy, seeking help from support groups) and social support, both reflecting more problem-focused or approach-oriented styles of coping. While relatively unsurprising given the reduced access to professional mental health services and social interaction, it corroborates specific concerns about the absence of adequate grief supports throughout the pandemic. Despite being the least endorsed strategies, help-seeking and social support were the only two strategies that were positively correlated with overall QOL, underscoring the importance of these strategies for better grief outcomes. Generally, individuals who engage in a variety of coping strategies, including both approach- and avoidant-oriented coping, adjust better to loss than those who rely on one strategy alone (Cheng et al., 2014). Though this study did not examine coping specifically along an approach-avoidance dimension, limited opportunities to utilize approach strategies (e.g., attending support groups or grief treatment, participating in grieving rituals, seeking social support) may impact how an individual adjusts to loss (Burton et al., 2012).

How mourners cope with grief has a significant influence on their bereavement trajectory and consequently predicts grief outcomes (Stroebe et al., 2006). The second primary goal of this study was to examine the role of various coping strategies in bereaved individuals’ associated mental health consequences; specifically, whether certain coping strategies may buffer grievers from poor QOL outcomes following a loss and for whom these strategies may benefit the most. We found that help-seeking was the only coping strategy that buffered the impact of grief on overall QOL particularly among individuals experiencing high levels of grief. Among mourners with high grief severity, greater help-seeking was related to greater overall QOL compared to those who endorsed less help-seeking. Among individuals with low to moderate grief severity, QOL was similar regardless of the amount of help-seeking they endorsed. This suggests that help-seeking may be a particularly useful method for minimizing negative mental health consequences of more severely bereaved individuals who may otherwise develop pathological grief and/or related psychopathologies. This has been demonstrated in non-COVID samples; that is, grief treatment seems to be most effective for those with more severe grief symptoms (Currier et al., 2008; Stroebe et al., 2006).

While these findings are important for identifying who may benefit from professional grief services, it is particularly concerning considering the significantly elevated levels of disturbed grief during the pandemic, low endorsement of help-seeking among our sample, and the limited availability and accessibility of grief treatments. Earlier in the pandemic, many researchers anticipated the heightened need for more accessible (e.g., remotely delivered), effective interventions for disturbed grief, calling for research to validate such predictions (e.g., Amy & Doka, 2021; Eisma et al., 2020). We provide the first empirical support underscoring the critical need for increasing accessibility and availability of grief-specific interventions to improve bereavement outcomes during the pandemic. This may be particularly relevant for those within lower-income communities who are experiencing higher grief severity and may have greater barriers to accessing effective treatments.

Findings should be interpreted in the context of some methodological limitations. Data were derived through an undergraduate research pool and online voluntary sampling which yielded a relatively young sample. This likely limited the diversity of sociodemographic and loss-related characteristics assessed as correlates of grief severity, including age, income, education, and relationship to the deceased (e.g., most participants lost a grandparent, and none lost a partner or child) which have been captured in more heterogenous samples (Eisma & Tamminga, 2020; Tang et al., 2021; Tang & Xiang, 2021). Nonetheless, this study identified characteristics associated with grief that are relevant among young adults which may assist in a more targeted understanding of COVID-19 bereavement consequences for this population. To further validate findings within the current literature, future studies should consider a more sociodemographically diverse sample and broader range of possible grief correlates. Due to the cross-sectional design, we could only examine associations with acute grief rather than the development of disturbed grief (e.g., CG or PGD), which require symptoms to be present for a prolonged period (6–12 months post-loss, respectively). Although diagnosis of such disorders was precluded in this study, acute grief is a strong longitudinal predictor of CG and PGD and is a reliable method for ascertaining grief severity and risk for disturbed grief. More longitudinal studies are needed to examine the long-term consequences of COVID-19 on the bereavement process and associated mental health outcomes.

Notwithstanding these limitations, this study validates ongoing concerns from grief researchers that grief may become a global mental health concern during the COVID-19 pandemic. The high rate of clinically relevant grief symptoms identified in this study corroborate the documented increases in disordered grief and related mental health problems, highlighting the need for more accessible and available grief supports for improving bereavement outcomes. Among the ways grievers are currently coping, our findings provide preliminary evidence that help-seeking is one of least endorsed strategies being employed despite it being a notable buffer against negative QOL consequences associated with grief. Particularly for those experiencing severe grief, there is an urgent need to increase access to professional grief-related services such as more face-to-face and remotely delivered therapeutic interventions, support groups, and professional self-help resources. Others have noted that currently available supports may not be sufficient due to evidence-based grief treatments not being widely available and the limited number of qualified professionals to deliver such treatments during the pandemic (Eisma et al., 2020). Therefore, leveraging online formats in the development and dissemination of grief treatments will likely be a fruitful approach for delivering effective supports to a growing population of bereaved individuals. Greater emphasis on improving grief supports is needed particularly in more affected regions where COVID-19 is still highly persistent and among underserved populations who may be most vulnerable to the negative consequences of grief.

Author Biographies

Marlee R. Salisbury and Cassandra R. W. Harmsen are both PhD students in Clinical Developmental Psychology at York University, conducting research in the Trauma & Attachment Lab.

Robert T. Muller is a professor of clinical psychology at York University, where he directs the Trauma & Attachment Lab, and leads several multi-site studies examining the treatment of interpersonal trauma. He is also a fellow of the International Society for the Study of Trauma & Dissociation, and author of the psychotherapy books: “Trauma & the Avoidant Client,” and “Trauma & the Struggle to Open Up.”

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Marlee R. Salisbury https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2161-1148

References

- Amy T., Doka K. (2021). A call to action: Facing the shadow pandemic of complicated forms of grief. OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying, 83(1), 164–169. 10.1177/0030222821998464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bereavement Authority of Ontario (2020, December 17). COVID-19 updates archive 2020. Bereavement Authority of Ontario. https://thebao.ca/covid-19-updates-archive-2020/ [Google Scholar]

- Bertuccio R. F., Runion M. C. (2020). Considering grief in mental health outcomes of COVID-19. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(S1), S87–S89. 10.1037/tra0000723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boelen P. A., Prigerson H. G. (2007). The influence of symptoms of prolonged grief disorder, depression, and anxiety on quality of life among bereaved adults: A prospective study. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 257(8), 444–452. 10.1007/s00406-007-0744-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breen L. J. (2021). Harnessing social support for bereavement now and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. Palliative Care and Social Practice, 15, Article 263235242098800. 10.1177/2632352420988009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke L. A., Neimeyer R. A., McDevitt-Murphy M. E. (2010). African american homicide bereavement: Aspects of social support that predict complicated grief, PTSD, and depression. OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying, 61(1), 1–24. 10.2190/OM.61.1.a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton C. L., Yan O. H., Pat-Horenczyk R., Chan I. S., Ho S., Bonanno G. A. (2012). Coping flexibility and complicated grief: A comparison of American and Chinese samples. Depression and Anxiety, 29(1), 16–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R. (2022). Social support as a protective factor against the effect of grief reactions on depression for bereaved single older adults. Death Studies, 46(3), 756–763. 10.1080/07481187.2020.1774943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng C., Lau H.-P. B., Chan M.-P. S. (2014). Coping flexibility and psychological adjustment to stressful life changes: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 140(6), 1582–1607. 10.1037/a0037913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y., Kim J.-H., Park E.-C. (2015). The effect of subjective and objective social class on health-related quality of life: New paradigm using longitudinal analysis. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 13(1), 121. 10.1186/s12955-015-0319-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crunk A.E., Burke L.A., Neimeyer R.A., Robinson E., III, Bai H. (2021). The coping assessment for bereavement and loss experiences (CABLE): Development and initial validation. Death Studies, (45(9), 677–691. 10.1080/07481187.2019.1676323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currier J. M., Neimeyer R. A., Berman J. S. (2008). The effectiveness of psychotherapeutic interventions for bereaved persons: a comprehensive quantitative review. Psychological Bulletin, 134(5), 648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diolaiuti F., Marazziti D., Beatino M. F., Mucci F., Pozza A. (2021). Impact and consequences of COVID-19 pandemic on complicated grief and persistent complex bereavement disorder. Psychiatry Research, 300, Article 113916. 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisma M. C., Boelen P. A. (2021). Commentary on: A call to action: Facing the shadow pandemic of complicated forms of grief. OMEGA -. Journal of Death and Dying, Article, 003022282110162. 10.1177/00302228211016227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisma M. C., Boelen P. A., Lenferink L. I. M. (2020). Prolonged grief disorder following the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Psychiatry Research, 288, 113031. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisma M. C., Tamminga A. (2020). Grief before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: Multiple group comparisons. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 60(6), Article e1-e4. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisma M. C., Tamminga A., Smid G. E., Boelen P. A. (2021). Acute grief after deaths due to COVID-19, natural causes and unnatural causes: An empirical comparison. Journal of Affective Disorders, 278, 54–56. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gesi C., Carmassi C., Cerveri G., Carpita B., Cremone I. M., Dell’Osso L. (2020). Complicated grief: what to expect after the coronavirus pandemic. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government of Canada (2022). Apri 28). COVID-19 daily epidemiology update. infobase. https://health-infobase.canada.ca/covid-19/ [Google Scholar]

- Hamid W., Jahangir M. S. (2020). Dying, death and mourning amid COVID-19 pandemic in Kashmir: A qualitative study. OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying, 85(3), 003022282095370–003022282095715. 10.1177/0030222820953708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrop E., Morgan F., Longo M., Scott H., Seddon K., Sivell S., Nelson A., Byrne A. (2020). The impacts and effectiveness of support for people bereaved through advanced illness: A systematic review and thematic synthesis. Palliative Medicine, 34(7), 871–888. 10.1177/0269216320920533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A. F. (2013). Mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. In Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (1, p. 20). New York: Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes S. (2005). Assessing the quality of life—reality or impossible dream? International Journal of Nursing Studies, 42(4), 493–501. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2004.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantamneni N., theUnited States (2020). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on marginalized populations in the United States: A research agenda. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 119, 103439. 10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latham A. E., Prigerson H. G. (2004). Suicidality and bereavement: Complicated grief as psychiatric disorder presenting greatest risk for suicidality. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 34(4), 350–362. 10.1521/suli.34.4.350.53737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason T. M., Tofthagen C. S., Buck H. G. (2020). Complicated grief: Risk factors, protective Factors, and interventions. Journal of Social Work in End-of-Life & Palliative Care, 16(2), 151–174. 10.1080/15524256.2020.1745726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayland C. R., Harding A. J., Preston N., Payne S. (2020). Supporting adults bereaved through COVID-19: A rapid review of the impact of previous pandemics on grief and bereavement. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 60(2), Article e33-e39. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.05.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayo Clinic (2021, June 19). Complicated grief. Mayo Clinic.https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/complicated-grief/symptoms-causes/syc-20360374 [Google Scholar]

- Mezzich J. E., Cohen N. L., Ruiperez M. A., Banzato C. E., Zapata-Vega M. I. (2011). The multicultural quality of life index: Presentation and validation. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 17(2), 357–364. 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01609.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortazavi S. S., Assari S., Alimohamadi A., Rafiee M., Shati M., isolation (2020). Fear, loss, social isolation and incomplete grief due to COVID-19: A recipe for a psychiatric pandemic. Basic and Clinical Neuroscience, (11(2), 225. 10.32598/bcn.11.covid19.2549.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neimeyer R. A., Baldwin S. A., Gillies J. (2006). Continuing bonds and reconstructing meaning: Mitigating complications in bereavement. Death Studies, 30(8), 715–738. 10.1080/07481180600848322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palan S., Schitter C. (2018). Prolific. ac—A subject pool for online experiments. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, 17, 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Peer E., Brandimarte L., Samat S., Acquisiti A. (2017). Beyond the Turk: Alternative platforms for crowdsourcing behavioral research. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 70, 153–163. [Google Scholar]

- Pietrabissa G., Simpson S. G. (2020). Psychological consequences of social isolation during COVID-19 outbreak. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 2201. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper W. E., Ogrodniczuk J. S., Joyce A. S., Weideman R. (2011). Risk factors for complicated grief. In Piper W. E., Ogrodniczuk J. S., Joyce A. S., Weideman R. (Eds.), Short-term group therapies for complicated grief: Two research-based models (pp. 63–106). American Psychological Association. 10.1037/12344-003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prigerson H. G., Maciejewski, P. K., Reynolds III C. F., Bierhals A. J., Newsom J. T., Fasiczka A., Frank E., Doman J., Miller M. (1995). Inventory of Complicated Grief: A scale to measure maladaptive symptoms of loss. Psychiatry Research, 59(1–2), 65–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson C., Pond D. R. (2019). Do online support groups for grief benefit the bereaved? Systematic review of the quantitative and qualitative literature. Computers in Human Behavior, 100, 48–59. 10.1016/j.chb.2019.06.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Root B. L., Exline J. J. (2014). The role of continuing bonds in coping with grief: Overview and future directions. Death Studies, 38(1), 1–8. 10.1080/07481187.2012.712608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon N. M., Shear K. M., Thompson E. H., Zalta A. K., Perlman C., Reynolds C. F., Frank E., Melhem N. M., Silowash R. (2007). The prevalence and correlates of psychiatric comorbidity in individuals with complicated grief. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 48(5), 395–399. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2007.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada . (2022, June 9). Provisional death counts and excess mortality. Statistics Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/220609/dq220609e-eng.htm [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe M., Schut H., Stroebe W. (2007). Health outcomes of bereavement. Lancet, 370(9603), 1960–1973. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61816-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe M. S., Folkman S., Hansson R. O., Schut H. (2006). The prediction of bereavement outcome: Development of an integrative risk factor framework. Social Science & Medicine, 63(9), 2440–2451. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang S., Xiang Z. (2021). Who suffered most after deaths due to COVID-19? Prevalence and correlates of prolonged grief disorder in COVID-19 related bereaved adults. Globalization and Health, 17(1), 19. 10.1186/s12992-021-00669-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang S., Yu Y., Chen Q., Fan M., Eisma M. C. (2021). Correlates of mental health after COVID-19 bereavement in mainland China. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 61(6), e1-e4. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdery A. M., Smith-Greenaway E., Margolis R., Daw J. (2020). Tracking the reach of COVID-19 kin loss with a bereavement multiplier applied to the United States. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(30), 17695–17701. 10.1073/pnas.2007476117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2022, April 28). WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard. World Health Organization. https://covid19.who.int/ [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization , (2020, October 5). COVID-19 disrupting mental health services in most countries. WHO survey. https://www.who.int/news/item/05-10-2020-covid-19-disrupting-mental-health-services-in-most-countries-who-survey#:∼:text=Countriesreportedwidespreaddisruptionof,orpostnatalservices(61%25) [Google Scholar]