Abstract

Purpose

Care for older adults with cancer became more challenging during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly in urban hotspots. This study examined the potential differences in healthcare providers’ provision of as well as barriers to cancer care for older adults with cancer between urban and suburban/rural settings.

Methods

Members of the Advocacy Committee of the Cancer and Aging Research Group, with the Association of Community Cancer Centers, surveyed multidisciplinary healthcare providers responsible for the direct care of patients with cancer. Respondents were recruited through organizational listservs, email blasts, and social media messages. Descriptive statistics and chi-square tests were used.

Results

Complete data was available from 271 respondents (urban (n = 144), suburban/rural (n = 127)). Most respondents were social workers (42, 44%) or medical doctors/advanced practice providers (34, 13%) in urban and suburban/rural settings, respectively. Twenty-four percent and 32.4% of urban-based providers reported “strongly considering” treatment delays among adults aged 76–85 and > 85, respectively, compared to 13% and 15.4% of suburban/rural providers (Ps = 0.048, 0.013). More urban-based providers reported they were inclined to prioritize treatment for younger adults over older adults than suburban/rural providers (10.4% vs. 3.1%, p = 0.04) during the pandemic. The top concerns reported were similar between the groups and related to patient safety, treatment delays, personal safety, and healthcare provider mental health.

Conclusion

These findings demonstrate location-based differences in providers’ attitudes regarding care provision for older adults with cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00520-022-07544-y.

Keywords: Older adults, Geriatric oncology, COVID-19, Rural, Urban, Healthcare providers

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on cancer care since the emergence of the virus in late 2019 [1]. To date, there have been more than 606 million confirmed COVID-19 cases and more than 6 million deaths globally [2]. Older adults (age ≥ 65 years) with cancer have been particularly impacted by the pandemic [3–14]. Older survivors of cancer who contract COVID-19 are more likely to present with greater symptom severity and have higher mortality compared to younger cancer survivors [3–5]. Cancer care provision to older adults is further complicated by the fact that older cancer survivors are often underrepresented in research and thus lack tailored, evidence-based guidelines informed by the distinctive needs of this population [15–18].

Consideration of demographic location is needed, given disparities between cancer treatment in urban and rural settings, which have been documented in the literature. Current literature indicates that rural-dwelling cancer survivors are more likely to be older, to experience higher mortality, have more advanced disease progression on presentation, and difficulty accessing adequate cancer care than urban-residing patients [19]. Such disparities are reflected in the prioritization that targets improved rural cancer care by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the National Cancer Institute (NCI) [20–22]. The increased reliance on telemedicine that many healthcare systems have adopted as a result of the pandemic may have furthered these documented disparities, as digital broadband access is less feasible in more rural locations [23–28].

Additionally, investigation by demographic location of cancer care providers’ perspectives in light of COVID-19 is pertinent, considering the devastating effects of the pandemic in urban hotspots [29]. The risk of spread of COVID in these more densely populated areas has had a significant impact on older survivors of cancer, as older adults residing in urban areas are more likely to report disruptions to daily life compared to rural-dwelling older adults [19]. Despite being rich in healthcare infrastructure, barriers to care unique to urban settings exist including language barriers and unwelcoming healthcare facilities [30]. Rural settings also have unique barriers to care including limited access to quality healthcare, struggles with healthcare workforce retention, and lower availability of COVID-19 vaccinations, which negatively impact cancer care provided to older adults [30, 31]. For example, Saelee et al. found that COVID-19 vaccination coverage with the first dose of the primary vaccination series was lower in rural (58.5%) than in urban counties (75.4%); these disparities have increased more than twofold since April 2021 [32]. Thus, examining the location of healthcare providers is essential to understand the potential differences in their provision of and barriers to cancer care for older adults.

Some research has examined healthcare provider perspectives, highlighting the fear, uncertainty, and frustration over inconsistent guidelines and messaging in the early weeks and months of the pandemic, including fear of adequate supply of personal protective equipment (PPE) [33, 34]. To our knowledge, there is currently no literature examining geriatric oncology provider perspectives during the pandemic by location. Clinician perspectives provide insight into factors affecting treatment and survivorship care, decision-making, and priorities due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, the objective of this study was to examine if healthcare providers’ provision of as well as barriers to cancer care for older adults with cancer differs between urban and suburban/rural settings through an online questionnaire.

Materials and methods

In Spring 2020, members of the Advocacy Committee of the Cancer and Aging Research Group (CARG) and the Association of Community Cancer Centers (ACCC) developed a Qualtrics questionnaire for providers of direct care for people with cancer. The online questionnaire included 20 items, three of which were open-ended questions, focusing on the care of older adults with cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic in a variety of settings (see Appendix 1 for questionnaire). Previous efforts highlighting the quantitative and qualitative results have been reported [33, 34]. This paper reports the comparative analysis of the quantitative data by participant-reported urban and suburban/rural settings. Those practicing in suburban and rural settings were combined due to lower sample sizes compared to the urban settings as well as previous literature [35–37]. Zip and census codes were not collected to convert to rural–urban commuting area (RUCA) codes due to the survey’s international distribution [38].

Participants were asked about the prioritization of treatment for different age groups of patients with cancer, factors associated with the prioritization or rescheduling of cancer treatments, receipt of guidance for decision-making, and the existence or lack of written guidelines regarding the management of older adults with cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic. Other questions explored the top five safety concerns related to COVID-19, barriers associated with the use of telemedicine, and increased barriers observed among older people with cancer. Information about providers’ professional history (years in providing care to patients with cancer, percentage of older patients, medical profession/specialty, cancer program classification and setting) was collected.

Potential respondents were recruited by emails sent through four professional organizations’ listservs and email blasts (CARG, ACCC, Association of Oncology Social Work, and Social Work Hospice and Palliative Care Network) as well as social media messaging (e.g., Facebook, Twitter). Individuals were eligible to participate if they (1) provided care for adults with cancer, (2) participated in the study voluntarily, and (3) understood that the results may be reported in multiple publications.

The online questionnaire was available from April 8, 2020, to May 1, 2020. The study was determined exempt by the University of Cincinnati Institutional Review Board as no identifying information was included in the collected data. The data were analyzed using descriptive statistics (frequencies, percentages), and chi-square tests of independence with IBM SPSS Statistics version 27.0.

Results

Demographic characteristics

Complete data were available from 271 respondents (urban (n = 144), suburban/rural (n = 127)). Most respondents were social workers (46.5% urban, 45.7% suburban/rural) or medical doctors/advanced practice providers (45.8%, 22.0%) in urban and suburban/rural settings, respectively. Suburban/rural providers had significantly more years of professional experience than urban providers (p = 0.033). Suburban/rural providers saw a significantly higher percentage of older adults than urban providers (p = 0.016). Lastly, urban providers worked primarily within academic medical centers or National Cancer Institute Comprehensive Cancer Centers while suburban/urban providers worked within community cancer programs (p < 0.001). (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic information of survey respondents (n = 271)

| Urban (n = 144) n (%) |

Suburban/rural (n = 127) n (%) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| US-based | 126 (87.5) | 124 (97.6) | 0.007 |

| Profession | |||

| Medical doctor and advanced practice providersa | 66 (45.8) | 28 (22.0) | < 0.001 |

| Social worker | 67 (46.5) | 58 (45.7) | |

| Administration/program leader | 4 (2.8) | 16 (12.7) | |

| Nurse navigator/navigator | 9 (6.3) | 5 (4.0) | |

| Multiple | 5 (3.5) | 12 (9.5) | |

| Otherb | 17 (11.8) | 21 (16.5) | |

| Number of years providing care to patients with cancer | |||

| 1–4 | 35 (24.3) | 21 (16.5) | 0.033 |

| 5–10 | 38 (26.4) | 27 (21.3) | |

| 11–20 | 43 (29.9) | 35 (27.6) | |

| 20 + | 28 (19.4) | 44 (34.6) | |

| % of patients are older adults (age ≥ 65 years) | |||

| < 10% | 2 (1.4) | 0 (0) | 0.016 |

| 11–25% | 9 (6.3) | 3 (2.4) | |

| 26–50% | 43 (30.1) | 27 (21.3) | |

| 51–75% | 69 (48.3) | 86 (67.7) | |

| > 75% | 20 (14.0) | 11 (8.7) | |

| Classification | |||

| Academic/NCI comprehensive cancer center | 81 (56.3) | 18 (14.2) | < 0.001 |

| Hospital | 21 (14.6) | 25 (19.7) | |

| Community cancer program | 18 (12.5) | 60 (47.2) | |

| Integrated | 10 (6.9) | 9 (7.1) | |

| Physician-owned oncology practice | 4 (2.8) | 1 (0.8) | |

| Other | 9 (6.3) | 7 (5.5) | |

aOncologists, geriatricians, or advanced practice providers. Oncologists included medical, surgical, radiation, gynecologic, and geriatric specialties

bIncludes oncology nurses, dieticians, case managers, palliative care workers, and medical assistants

Prioritization and postponement of treatment

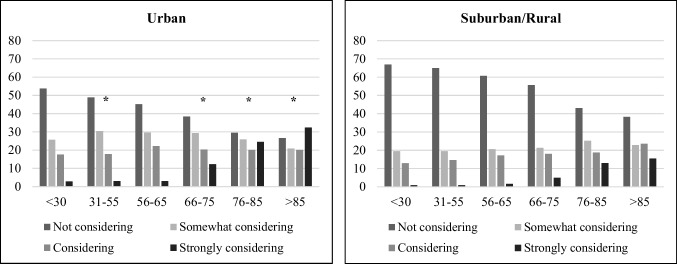

Significant differences were found between urban and suburban/rural providers regarding their considerations in prioritizing treatment for different age groups of patients with cancer. Urban providers reported higher inclinations (10.4%) than suburban/rural providers (3.1%) to prioritize treatment for younger patients over older adults (X2 = 6.09, p = 0.048). Furthermore, when asked about postponing/rescheduling treatment due to COVID-related concerns, based on age group, urban providers reported significantly higher consideration of postponing/rescheduling treatment for adults aged 31–55, 66–75, 76–85, and > 85 than their suburban/rural counterparts (Fig. 1). Specifically, 24.5% and 32.4% of urban-based providers reported “strongly considering” treatment delays among adults aged 76–85 and > 85, respectively, compared to 13.0% and 15.4% of suburban/rural providers (X2 = 6.09, p = 0.048; X2 = 10.85, p = 0.013, respectively). There was no significant difference in postponing/rescheduling treatment due to COVID-related concerns, among patients aged 56–65 between urban and suburban/rural providers.

Fig. 1.

Consideration of postponing or rescheduling cancer treatment by age group among urban and suburban/rural providers. Note: * = p < 0.05. Specific p-values = 0.048, 0.020, 0.048, and 0.013 for 31–55, 66–75, 76–85, and > 85 age groups between urban and suburban/rural providers

Both urban and suburban/rural providers considered comorbidities, cancer stage, frailty, performance status (e.g., patient’s ability to perform certain activities of daily living without help), and age as their top five factors in deciding to postpone/reschedule cancer treatment during the pandemic (Table 2). However, urban providers reported considering comorbidities (77.1% vs. 66.1%, respectively, X2 = 4.00, p = 0.045), life expectancy (47.9% vs. 31.5%, respectively, X2 = 7.57 p = 0.006), family member access (e.g., family member attendance in clinic visits, hospital stays) (39.6% vs. 22.8%, respectively, X2 = 8.74 p = 0.003), and psychosocial status (e.g., emotional and social functioning) (38.2% vs. 25.2%, respectively, X2 = 5.23, p = 0.022) at significantly higher rates than suburban/rural providers.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics taken into account when considering to postpone/reschedule cancer treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic

| Urban n (%) |

Sub/rural n (%) |

Chi-square p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comorbidities | 111 (77.1) | 84 (66.1) | 0.045 |

| Cancer stage | 106 (73.6) | 85 (66.9) | 0.229 |

| Frailty | 102 (70.8) | 86 (67.7) | 0.579 |

| Performance status (patient’s ability to perform certain activities of daily living without help) | 88 (61.1) | 67 (52.8) | 0.165 |

| Age | 78 (54.2) | 55 (43.3) | 0.074 |

| Life expectancy | 69 (47.9) | 40 (31.5) | 0.006 |

| Family member access (family member attendance in clinic visits, hospital stays) | 57 (39.6) | 29 (22.8) | 0.003 |

| Psychosocial status (emotional and social functioning) | 55 (38.2) | 32 (25.2) | 0.022 |

| Transportation | 52 (36.1) | 38 (29.9) | 0.280 |

| Insurance | 10 (6.9) | 4 (3.1) | 0.159 |

| Employment | 5 (3.5) | 2 (1.6) | 0.326 |

| Other | 25 (17.4) | 23 (18.1) | 0.872 |

There was no difference by provider location regarding specific written guidelines regarding the management of older adults with cancer during the COVID-19 crisis (X2 = 2.10, p = 0.43). Specifically, 52.8% and 58.7% of urban and suburban/rural providers, respectively, reported no written guidelines and an additional 29.2% and 29.1% of urban and suburban/rural providers reported uncertainty of any written guidelines.

Safety concerns related to COVID-19

Overall, the top concerns related to COVID-19 reported were similar between the urban- and suburban-/rural-based providers (Table 3). The most common concern was patient safety (81.9%, 85.8%) followed by treatment delays (62.5%, 66.9%), healthcare provider mental health (55.6%, 58.3%), and personal family safety (51.4%, 55.9%) among urban and suburban-/rural-based providers, respectively. Significant differences were observed by location for two safety concerns: supply of PPE and patient mental health. Suburban-/rural-based providers reported significantly higher concerns about the supply of PPE (62.2%) compared to urban-based providers (49.3%) (X2 = 4.54, p = 0.022). Lastly, urban-based providers reported significantly higher concerns about patient mental health (55.6%) than suburban-/rural-based providers (42.5%) (X2 = 4.59, p = 0.032).

Table 3.

Top 5 concerns related to COVID-19 reported by urban- and suburban-based providers

| Concerns | Urban n (%) |

Suburban/rural n (%) |

Chi-square p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient safety | 118 (81.9) | 109 (85.8) | 0.413 |

| Treatment delay | 90 (62.5) | 85 (66.9) | 0.447 |

| Healthcare provider mental health | 80 (55.6) | 74 (58.3) | 0.653 |

| Patient mental health | 80 (55.6) | 54 (42.5) | 0.032 |

| My family safety | 74 (51.4) | 71 (55.9) | 0.457 |

| Personal safety | 72 (50.0) | 60 (52.8) | 0.651 |

| Supply of personal protective equipment | 71 (49.3) | 79 (62.2) | 0.022 |

| Patient mortality | 67 (46.5) | 47 (37.0) | 0.113 |

| Family of patient safety | 24 (16.7) | 23 (18.1) | 0.754 |

| Research delays | 20 (13.9) | 10 (7.9) | 0.115 |

| Clinical trial accrual | 5 (3.5) | 4 (3.1) | 0.882 |

Barriers to resources and telemedicine

Urban-based providers reported significantly higher observed increase of barriers regarding access to prescriptions (29.9% vs. 16.5%, respectively, X2 = 6.64, p = 0.010). Additionally, urban providers reported higher observed increase of transportation barriers (74.3%) compared to their suburban/rural counterparts (68.5%, p = 0.178). Suburban-/rural-based providers reported higher observed increase of barriers among older adults accessing food (33.9%) and caregiver availability (66.1%) compared to their urban counterparts (31.3% and 62.5%, X2 = 2.09, p = 0.70; X2 = 0.39, p = 0.53, respectively).

There were no significant differences by provider location in reported increase of perceived barriers to using telemedicine with older adults with cancer (Table 4). The most reported perceived barriers were patient access (e.g., no smart phone, internet access) (91%, 92.1%), patient not being tech savvy (89.6%, 92.1%), and patient perception issues of telemedicine (40.3%, 49.6%) among urban- and suburban-/rural-based providers, respectively.

Table 4.

Providers’ reported barriers to using telehealth with older adults with cancer

| Variable | Urban n (%) |

Suburban/rural n (%) |

Chi-square p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient access (e.g., no smart phone or internet access) | 131 (91.0) | 117 (92.1) | 0.734 |

| Patient not tech savvy | 129 (89.6) | 117 (92.1) | 0.470 |

| Patient perception issues | 58 (40.3) | 63 (49.6) | 0.123 |

| Program/institution infrastructure | 43 (29.9) | 37 (29.1) | 0.896 |

| Healthcare worker technology challenges | 35 (24.3) | 40 (31.5) | 0.187 |

| Healthcare worker home-work issues | 23 (16.0) | 23 (18.1) | 0.640 |

| Healthcare worker preference/policy | 19 (13.2) | 12 (9.4) | 0.334 |

| Uncertainty of reimbursement | 17 (11.8) | 16 (12.6) | 0.842 |

| Other barriers | 9 (6.3) | 9 (7.1) | 0.811 |

| No barriers | 4 (2.8) | 0 (0) | 0.058 |

Discussion

This study examined whether healthcare providers’ provision of as well as barriers to care for older adults with cancer differed between urban and suburban/rural settings. Significant differences were found between urban and suburban/rural providers regarding their considerations for prioritizing treatment for different age groups of patients with cancer; urban-based providers were more likely to prioritize treatment for younger patients than older patients. This result is most likely due to the timing of the survey, April 2020, when major urban centers such as New York City were experiencing high numbers of COVID-19 cases. In later months, cases surged in suburban and rural settings [39]. Contrary to the current study’s findings regarding treatment prioritization in urban settings, McGuire and colleagues argued that, in suburban/rural areas, patients may be more vulnerable to the economic and health impacts of a pandemic [40]. They posited that rural healthcare providers are not only fewer in number than their urban counterparts, but also work with fewer resources, less public transportation, and delivery options. Another potential reason for the difference in treatment prioritization by provider location may be related to the ageist approach that older adults with cancer should not receive equal treatment [15, 41, 42]. Previous studies have found that the COVID-19 pandemic has accentuated the exclusion and prejudice against older adults, warranting immediate intervention and education [15, 41, 43, 44]. This ageist perspective observed in the current study may have emerged in part by the lack of written guidelines for the management of older adults with cancer experienced by more than half of the rural- and suburban-based providers. An additional possibility is the perception that older adults are more likely to have comorbidities or be frail and, hence, have increased risk for cancer treatment toxicity during COVID-19 [45]. The current study’s findings support this notion; urban respondents considered comorbidities and life expectancy (77%, 48%) at significantly higher prevalence than their suburban/rural counterparts (66%, 32%, respectively). Additional information about the provider’s patient populations (e.g., median age, cancer stage) and their institution’s response to COVID-19 (e.g., guidelines, hospital strain) as well as their experience (e.g., geriatric specializations, trainings) would provide context for better understanding of the inclinations to prioritize treatment for different age groups of patients with cancer.

Provider concerns regarding COVID-19 were similar regardless of provider location. The most reported concerns were patient safety, treatment delays, and personal/family safety. Significant differences were observed regarding patient mental health (higher in urban-based providers) and supply of PPE (higher in suburban-/rural-based providers). These differences may be attributed to limited resources by location. COVID-19 surged in urban areas with limited mental healthcare support (both informal and formal) despite increased demand during the data collection period. Telemedicine challenges at that period may have also negatively impacted patient mental health [46–48]. At the same time, the need for PPE was concentrated and subsequently prioritized to those areas of surge, away from suburban/rural areas, leaving these providers with less PPE than the urban-based providers [49, 50].

Barriers to using telemedicine were commonly experienced by both urban and suburban/rural providers. This finding was expected and understandable given the sudden proliferation of telemedicine among adults with cancer. The use of telemedicine by some estimates grew 30-fold in the USA and almost 100-fold in the Medicare population in the second quarter of 2020 compared to before the pandemic [51, 52]. Before COVID-19, research found that older adults are more receptive to technology use than was typically assumed [53–55]. For example, over two-thirds of older adults use the internet daily and more than half have home broadband service [56]. However, as evidenced by this study and others, older adults using technology may have barriers to telemedicine use, including internet and device access, design challenges, privacy and trust concerns, and cost [57–60]. For example, Lam and colleagues found many older adults may be unable to take part in health-related video visits because of disabilities or inexperience with technology [60]. Again, the timing of this survey may have influenced the reported barriers regarding telemedicine. In Spring 2020, the roll-out of telemedicine was rapidly implemented to ensure adequate continuity of care while minimizing exposure to COVID-19. As telemedicine care becomes more widely used, it provides an important opportunity to expand telemedicine care to older, rural patients who live a greater distance from tertiary medical centers, or to those older adults who may have transportation or mobility limitations. Regardless of location, modifications to telemedicine geriatric assessment as well as video visits [61] are important for promoting positive patient outcomes and patient-provider relationships, facilitating clear communication, and observing non-verbal communication [62–65].

Limitations

The first limitation was that suburban and rural provider’s responses were combined to facilitate adequate sample size compared to the sample size of urban-based providers. There could be differences between the two settings such as resources and the impact of COVID-19 at the time of the survey. In addition, there was an uneven distribution of healthcare providers (MDs and APPs versus social workers) based on location, which may skew the findings to a psychosocial lens rather than a treatment decision-making lens. Similarly, significantly more suburban/rural providers than urban providers were US-based, which can bias comparisons between urban and suburban/rural provider responses. Lastly, several of the survey items asked explicitly about caring for older adults. Therefore, respondents who did not primarily care for older adults were asked to answer specifically about this age group. This focus on older adults with cancer may skew the findings away from experiences related to the general population of patients with cancer.

Conclusion

This study explored differences in urban and suburban/rural settings in the care provision of as well as barriers to cancer care for older adults during COVID-19. Results demonstrated location-based differences in providers’ attitudes regarding care provision for older adults with cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic. Targeted educational efforts may help reduce ageist views regarding the treatment of older adults with cancer in urban areas. Interventions to develop more robust infrastructure in the time of public health crisis will enable the systems to provide optimum equitable care for all patients with cancer. Otherwise, it is likely that the most vulnerable patients, such as older adults, will continue to be underserved and disadvantaged.

Supplementary information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The societies and groups (Cancer and Aging Research Group, Association of Community Cancer Centers, Association of Oncology Social Work, and Social Work Hospice and Palliative Care Network) who helped distribute the survey to their members.

Abbreviations

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- NCI

The National Cancer Institute

- PPE

Personal protective equipment

- CARG

Cancer and Aging Research Group

- ACCC

Association of Community Cancer Centers

- RUCA

Rural-urban commuting area

- MDs

Medical doctors

- APPs

Advanced practice providers

Author contribution

Janell Pisegna: conceptualization, methodology, writing — original draft, writing — review and editing; Karlynn BrintzenhofeSzoc: conceptualization, data collection, methodology, writing — original draft, writing — review and editing; Armin Shahrokni: conceptualization, data collection, methodology, writing — original draft, writing — review and editing; Beverly Canin: conceptualization, methodology, writing — original draft, writing — review and editing; Elana Plotkin: conceptualization, data collection, methodology, writing — original draft, writing — review and editing; Leigh Boehmer: conceptualization, data collection, methodology, writing — original draft, writing — review and editing; Leana Chien: conceptualization, writing — original draft, writing — review and editing; Mariuxi Viteri Malone: conceptualization, writing — original draft, writing — review and editing; Amy MacKenzie: data collection, methodology, writing — original draft; Jessica Krok-Schoen: conceptualization, data collection, methodology, analyses, writing — original draft, writing — review and editing.

Funding

This project was supported in part by the grant no. P30 CA008748 from the National Institute of Health.

Data Availability

Due to its proprietary nature, supporting data cannot be made openly available.

Declarations

Ethics approval

The study was determined exempt by the University of Cincinnati Institutional Review Board as no identifying information was included in the collected data.

Consent to participate

Electronic consent was received by participants prior to questionnaire completion.

Consent for publication

Participants were informed that the questionnaire results would be used for publications and provided their consent.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Janell L. Pisegna, Email: janell.pisegna@cuanschutz.edu

Karlynn BrintzenhofeSzoc, Email: karlynn.brintzenhofeszoc@louisville.edu.

Armin Shahrokni, Email: shahroka@mskcc.org.

Beverly Canin, Email: caninbeverly@gmail.com.

Elana Plotkin, Email: EPlotkin@accc-cancer.org.

Leigh M. Boehmer, Email: lboehmer@accc-cancer.org

Leana Chien, Email: lchien@coh.org.

Mariuxi Viteri Malone, Email: mariux.viteri@gmail.com.

Amy R. MacKenzie, Email: Amy.Mackenzie@jefferson.edu

Jessica L. Krok-Schoen, Email: Jessica.krok@osumc.edu

References

- 1.Broom A, Kenny K, Page A, Cort N, Lipp ES, Tan AC, et al. The paradoxical effects of COVID-19 on cancer care: current context and potential lasting impacts. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26(22):5809–5813. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-2989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization (2022) WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/. Accessed 20 July 2022

- 3.Jain V, Yuan J-M. Predictive symptoms and comorbidities for severe COVID-19 and intensive care unit admission: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Public Health. 2020;65:533–546. doi: 10.1007/s00038-020-01390-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murthy S, Gomersall CD, Fowler RA. Care for critically ill patients with COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;323(15):1499–1500. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Onder G, Rezza G, Brusaferro S. Case-fatality rate and characteristics of patients dying in relation to COVID-19 in Italy. JAMA. 2020;323(18):1775–1776. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu K, Chen Y, Lin R, Han K. Clinical features of COVID-19 in elderly patients: a comparison with young and middle-aged patients. J Infect. 2020;80(6):e14–e18. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang H, Zhang L. Risk of COVID-19 for patients with cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(4):e181. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30149-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arentz M, Yim E, Klaff L, Lokhandwala S, Riedo FX, Chong M, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of 21 critically ill patients with COVID-19 in Washington State. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1612–1614. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang T, Du Z, Zhu F, Cao Z, An Y, Gao Y, et al. Comorbidities and multi-organ injuries in the treatment of COVID-19. The Lancet. 2020;395(10228):e52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30558-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu J, Ouyang W, Chua ML, Xie C. SARS-CoV-2 transmission in patients with cancer at a tertiary care hospital in Wuhan, China. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(7):1108–1110. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.0980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liang W, Guan W, Chen R, Wang W, Li J, Xu K, et al. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(3):335–337. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30096-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Y, Wang Y, Chen Y, Qin Q. Unique epidemiological and clinical features of the emerging 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) implicate special control measures. J Med Virol. 2020;92(6):568–576. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pothuri B, Secord AA, Armstrong DK, Chan J, Fader AN, Huh W, et al. Anti-cancer therapy and clinical trial considerations for gynecologic oncology patients during the COVID-19 pandemic crisis. Gynecol Oncol. 2020;158(1):16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2020.04.694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kutikov A, Weinberg DS, Edelman MJ, Horwitz EM, Uzzo RG, Fisher RI. A war on two fronts: cancer care in the time of COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(11):756–758. doi: 10.7326/M20-1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Falandry C, Filteau C, Ravot C, Le Saux O. Challenges with the management of older patients with cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Geriatr Oncol. 2020;11(5):747–749. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2020.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Daratsos L (2019) End-of-life care. In: Caring for patients with mesothelioma: principles and guidelines. Springer, pp 163–75

- 17.Hurria A, Levit LA, Dale W, Mohile SG, Muss HB, Fehrenbacher L, et al. Improving the evidence base for treating older adults with cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology statement. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(32):3826–3833. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.0319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Krok-Schoen JL, Canin B, Parker I, MacKenzie AR, Koll T, et al. The underreporting of phase III chemo-therapeutic clinical trial data of older patients with cancer: a systematic review. J Geriatr Oncol. 2020;11(3):369–379. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2019.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kenzik KM, Rocque GB, Landier W, Bhatia S. Urban versus rural residence and outcomes in older patients with breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2020;29(7):1313–1320. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-19-1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levit LA, Byatt L, Lyss AP, Paskett ED, Levit K, Kirkwood K, et al. Closing the rural cancer care gap: three institutional approaches. JCO Oncol Pract. 2020;16(7):422–430. doi: 10.1200/OP.20.00174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henley SJ, Anderson RN, Thomas CC, Massetti GM, Peaker B, Richardson LC. Invasive cancer incidence, 2004–2013, and deaths, 2006–2015, in nonmetropolitan and metropolitan counties—United States. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2017;66(14):1. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6614a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blake KD, Moss JL, Gaysynsky A, Srinivasan S, Croyle RT. Making the case for investment in rural cancer control: an analysis of rural cancer incidence, mortality, and funding trends. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2017;26(7):992–997. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-0092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Niranjan SJ, Hardy C, Bowman T, Bryant J, Richardson M, Tipre M, et al. Rural cancer health during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Cancer Educ. 2020;35(5):862–863. doi: 10.1007/s13187-020-01858-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DeGuzman PB, Bernacchi V, Cupp CA, Dunn B, Ghamandi BJF, Hinton ID, et al. Beyond broadband: digital inclusion as a driver of inequities in access to rural cancer care. J Cancer Surviv. 2020;14(5):643–652. doi: 10.1007/s11764-020-00874-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anderson M (2019) Mobile technology and home broadband. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2019/06/13/mobile-technology-and-home-broadband-2019/. Accessed 10 Jul 2022

- 26.Pew Research Center (2021) Demographics of internet and home broadband usage in the United States. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/internet-broadband/?menuItem=c41259a2-d3a8-480d-9d1b-2fb16bcf0584. Accessed 11 Jul 2022

- 27.Perrin A (2021) Mobile technology and home broadband 2021. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2021/06/03/mobile-technology-and-home-broadband-2021/. Accessed 11 Jul 2022

- 28.Jewett PI, Vogel RI, Ghebre R, Hui JY, Parsons HM, Rao A, Sagaram S, Blaes AH. Telehealth in cancer care during COVID-19: disparities by age, race/ethnicity, and residential status. J Cancer Surviv. 2022;16(1):44–51. doi: 10.1007/s11764-021-01133-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li Q, Bessell L, Xiao X, Fan C, Gao X, Mostafavi A (2021) Disparate patterns of movements and visits to points of interest located in urban hotspots across US metropolitan cities during COVID-19. R Soc Open Sci 8(1):201209 1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Paul R, Arif A, Pokhrel K, Ghosh S. The association of social determinants of health with COVID-19 mortality in rural and urban counties. J Rural Health. 2021;37(2):278–286. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malatzky C, Cosgrave C, Gillespie J. The utility of conceptualisations of place and belonging in workforce retention: a proposal for future rural health research. Health Place. 2020;62(102279):1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.102279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saelee R, Zell E, Murthy BP, Castro-Roman P, Fast H, Meng L, Shaw L, Gibbs-Scharf L, Chorba T. Harris LQ Murthy N (2022) Disparities in COVID-19 vaccination coverage between urban and rural counties—United States, December 14, 2020–January 31. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(9):335–340. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7109a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krok-Schoen JL, Pisegna JL, BrintzenhofeSzoc K, MacKenzie AR, Canin B, Plotkin E, et al. Experiences of healthcare providers of older adults with cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Geriatr Oncol. 2021;12(2):190–195. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2020.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Krok-Schoen JI, Pisegna JL, MacKenzie AR, Canin B, Plotkin E, et al. Survey of cancer care providers’ attitude toward care for older adults with cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Geriatr Oncol. 2021;12(2):196–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2020.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bender JL, Feldman-Stewart D, Tong C, Lee K, Brundage M, Pai H, et al. Health-related Internet use among men with prostate cancer in Canada: cancer registry survey study. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(11):e14241. doi: 10.2196/14241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li CC, Matthews AK, Dossaji M, Fullam F. The relationship of patient-provider communication on quality of life among African-American and White cancer survivors. J Health Commun. 2017;22(7):584–592. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2017.1324540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liou KT, Trevino KM, Meghani SH, Li QS, Deng G, Korenstein D, et al. Fear of analgesic side effects predicts preference for acupuncture: a cross-sectional study of cancer patients with pain in the USA. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(1):427–435. doi: 10.1007/s00520-020-05504-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.United States Department of Agriculture (2019).Rural-urban continuum codes. http://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes.aspx#.U8l7NfldVlw. Accessed 22 Mar 2019

- 39.Schnake-Mahl AS, Bilal U. Person, place, time and COVID-19 inequities. Am J Epidemiol. 2021;190(8):1447–51. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwab058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McGuire AL, Aulisio MP, Davis FD, Erwin C, Harter TD, Jagsi R, et al. Ethical challenges arising in the COVID-19 pandemic: an overview from the Association of Bioethics Program Directors (ABPD) task force. Am J Bioeth. 2020;20(7):15–27. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2020.1764138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fraser S, Lagacé M, Bongué B, Ndeye N, Guyot J, Bechard L, et al. Ageism and COVID-19: what does our society’s response say about us? Age Ageing. 2020;49(5):692–695. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afaa097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ayalon L, Chasteen A, Diehl M, Levy BR, Neupert SD, Rothermund K, et al. Aging in times of the COVID-19 pandemic: avoiding ageism and fostering intergenerational solidarity. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2021;76(2):e49–e52. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbaa051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Swift HJ, Chasteen AL. Ageism in the time of COVID-19. Group Process Intergroup Relat. 2021;24(2):246–252. doi: 10.1177/1368430220983452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Previtali F, Allen LD (2020) Varlamova M. Not only virus spread: the diffusion of ageism during the outbreak of COVID-19. J Aging Soc Policy 32(4–5):506–14 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Lewis EG, Breckons M, Lee RP, Dotchin C, Walker R. Rationing care by frailty during the COVID-19 pandemic. Age Ageing. 2020;50(1):7–10. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afaa171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vahia VN, Shah AB. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health care of older adults in India. Int Psychogeriatr. 2020;32(10):1125–1127. doi: 10.1017/S1041610220001441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thome J, Deloyer J, Coogan AN, Bailey-Rodriguez D, da Cruz E, Silva OA, Faltraco F, et al. The impact of the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental-health services in Europe. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2020;22(7):1–10. doi: 10.1080/15622975.2020.1844290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhai Y. A call for addressing barriers to telemedicine: health disparities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychother Psychosom. 2021;90(1):64–66. doi: 10.1159/000509000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gondi S, Beckman AL, Deveau N, Raja AS, Ranney ML, Popkin R, et al. Personal protective equipment needs in the USA during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2020;395(10237):e90–e91. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31038-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Norwegian Institute of Public Health (2020) Urbanization and preparedness for outbreaks with high-impact respiratory pathogens. https://apps.who.int/gpmb/assets/thematic_papers_2020/tp_2020_4.pdf. Accessed 13 June 2022

- 51.Alexander GC, Tajanlangit M, Heyward J, Mansour O, Qato DM, Stafford RS (2020) Use and content of primary care office-based vs telemedicine care visits during the COVID-19 pandemic in the US. JAMA Open Netw 3(10):e2021476 1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Verma S (2020) Early impact of CMS expansion of Medicare telehealth during COVID-19. Health Affairs. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200715.454789/full/. Accessed 13 June 2022

- 53.Greenwald P, Stern ME, Clark S, Sharma R. Older adults and technology: In telehealth, they may not be who you think they are. Int J Emerg Med. 2018;11(1):1–4. doi: 10.1186/s12245-017-0162-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brignell M, Wootton R, Gray L. The application of telemedicine to geriatric medicine. Age Ageing. 2007;36(4):369–374. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afm045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Anderson M, Perrin A, Jiang J, Kumar M (2019) 10% of Americans don’t use the internet. Who are they? Pew Research Center.https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/04/02/7-of-americans-dont-use-the-internet-who-are-they/. Accessed 13 June 2022

- 56.Anderson M, Perrin A (2017) Tech adoption climbs among older adults. Pew Research Center.https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2017/05/17/tech-adoption-climbs-among-older-adults/. Accessed 13 June 2022

- 57.Hargittai E, Piper AM, Morris MR. From internet access to internet skills: digital inequality among older adults. Univ Access Inf Soc. 2019;18(4):881–890. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kruse C, Fohn J, Wilson N, Patlan EN, Zipp S, Mileski M. Utilization barriers and medical outcomes commensurate with the use of telehealth among older adults: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2020;8(8):e20359. doi: 10.2196/20359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Roberts ET, Mehrotra A. Assessment of disparities in digital access among Medicare beneficiaries and implications for telemedicine. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(10):1386–1389. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.2666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lam K, Lu AD, Shi Y, Covinsky KE. Assessing telemedicine unreadiness among older adults in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(10):1389–1391. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.2671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brick R, Padgett L, Jones J, Wood KC, Pergolotti M, Marshall TF, Lyons KD (2022) The influence of telehealth-based cancer rehabilitation interventions on disability: a systematic review. J Cancer Survivorship 1–26. 10.1007/s11764-022-01181-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.DiGiovanni G, Mousaw K, Lloyd T, Dukelow N, Fitzgerald B, D'Aurizio H, et al. Development of a telehealth geriatric assessment model in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. J Geriatr Oncol. 2020;11(5):761–763. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2020.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wall SA, Knauss B, Compston A, Redder E, Folefac E, Presley C, et al. Multidisciplinary telemedicine and the importance of being seen. J Geriatr Oncol. 2020;11(8):1349–1351. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Klil-Drori S, Phillips N, Fernandez A, Solomon S, Klil-Drori AJ, Chertkow H. Evaluation of a telephone version for the montreal cognitive assessment: establishing a cutoff for normative data from a cross-sectional study. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2021;35(3):374–381. doi: 10.1177/08919887211002640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Guidarelli C, Lipps C, Stoyles S, Dieckmann NF, Winters-Stone KM. Remote administration of physical performance tests among persons with and without a cancer history: Establishing reliability and agreement with in-person assessment. J Geriatr Oncol. 2022;13(5):691–697. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2022.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Due to its proprietary nature, supporting data cannot be made openly available.