Abstract

Introduction

The aim was to investigate whether common pregnancy‐related symptoms—nausea, vomiting, back pain, pelvic girdle pain, pelvic cavity pain, vaginal bleeding, itching of vulva, pregnancy itching, leg cramps, uterine contractions and varicose veins—in the first trimester of pregnancy add to the identification of women at high risk of future pregnancy and birth complications.

Material and methods

Survey data linked to national register data. All women booking an appointment for a first prenatal visit in one of 192 randomly selected General Practices in East Denmark in the period April 2015–August 2016. The General Practices included 1491 women to this prospective study. Two outcomes, pregnancy complications and birth complications, were collected from the Danish Medical Birth Register.

Results

Among the 1413 included women, 199 (14%) experienced complications in later pregnancy. The most serious complication, miscarriage, was experienced by 65 women (4.6%). Other common pregnancy complications were gestational diabetes mellitus (n = 11, 0.8%), gestational hypertension without proteinuria (n = 34, 2.4%), mild to moderate preeclampsia (n = 34, 2.4%) and gestational itching with effect on liver (n = 17, 1.2%). Women who experienced pelvic girdle pain, pelvic cavity pain or vaginal bleeding in the first trimester of pregnancy had a higher risk of pregnancy complications later on in later pregnancy. None of the other examined symptoms showed associations to pregnancy complications. No associations were found between pregnancy‐related physical symptoms in first trimester and birth complications.

Conclusions

Symptoms in early pregnancy do not add much information about the risk of pregnancy or birth complications, although pain and bleeding may give reason for some concern. This is an important message to women experiencing these common symptoms and to their caregivers.

Keywords: birth complications, cohort, first trimester, general practice, pelvic cavity pain, pelvic girdle pain, pregnancy, pregnancy complications, vaginal bleeding

Women who experienced pelvic girdle pain, pelvic cavity pain or vaginal bleeding in the first trimester of pregnancy had a higher risk of later pregnancy complications, but we found no significant associations between any early pregnancy symptoms and birth complications.

Abbreviations

- CI

confidence interval

- GP

General practice

- ICD‐10

International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision

- MBR

medical birth register

- OR

odds ratio

Key message.

Women who experienced pelvic girdle pain, pelvic cavity pain or vaginal bleeding in the first trimester of pregnancy had a higher risk of later pregnancy complications, but we found no significant associations between any early pregnancy symptoms and birth complications.

1. INTRODUCTION

The onset of pregnancy has a number of well‐known challenges and symptoms that can be of concern to pregnant women. Symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, pelvic cavity pain, girdle pain, back pain, sleep disturbances and depression 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 are frequent, underreported and undertreated, maybe because of their common nature or the belief that they are normal, self‐limiting symptoms of pregnancy. However, there is a rise in interest in these symptoms because of their considerable frequency and morbidity. 1 , 6 Approximately 80% of women experience nausea, and vomiting affects 35%–40% in the first trimester. 2 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 Symptoms such as vulvar itching, vaginal infections, vaginal bleeding, pelvic cavity pain and pelvic girdle pain have been observed with frequencies of 25%–60%. 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 Furthermore, sleep complaints are common, even in the first trimester, and are associated with both physical and mental symptoms, 21 which are often not identified or treated. 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 In a previous study we demonstrated that back pain and pelvic cavity pain in the first trimester are associated with postpartum depression. 26 In continuation of this observation, we now aim to investigate whether these common symptoms (nausea, vomiting, back pain, pelvic girdle pain, pelvic cavity pain, vaginal bleeding, itching of vulva, pregnancy itching, leg cramps, uterine contractions and varicose veins) in early pregnancy may be predictive of more general complications in pregnancy and birth, and, hence, are indicative of a need for increased attention.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1. Study design

A prospective cohort study, following pregnant women from the first General Practice (GP) consultation in early pregnancy to childbirth.

2.2. Setting

The healthcare system in Denmark is tax‐funded and care is free of charge for patients. The majority of Danes are registered with a GP who functions as a gatekeeper to specialist secondary care. Citizens are entitled to see a regular GP of their own choosing and thereby register with a practice.

By law, pregnant women are invited to a minimum of three prenatal GP consultations in pregnancy weeks 6–10, 25 and 32. A fourth postnatal care consultation takes place 8 weeks after delivery. The first prenatal visit is attended by almost all pregnant women who wish to keep their pregnancy. In this consultation a thorough and structured record is established (the Pregnancy Health Record), which is then sent to midwives and the hospital department.

2.3. Participants

All GPs working in The Capital Region and Region Zealand, two of the five Danish administrative regions, were eligible to participate. A detailed description of the recruitment process can be found elsewhere. 21 All women booking an appointment for a first prenatal visit in the participating 192 GP' practices between April 1, 2015 and August 15, 2016 were eligible for participation. All women were given oral and written information about the project and were enrolled when signing a consent form.

2.4. Data and material

The data was collected by means of the Pregnancy Health Record and an electronic patient questionnaire. The Pregnancy Health Record is a standardized national two‐page paper form that is initiated and completed by the GP at the first prenatal care visit. The electronic questionnaire developed for this study was sent by e‐mail after the first prenatal care visit. The questionnaire was in Danish. Questionnaires were re‐issued to non‐responders after 2 weeks. If they still did not respond, an e‐mail and text message were sent.

The questionnaire inquired into pregnancy‐related symptoms: nausea, vomiting, back pain, pelvic girdle pain, pelvic cavity pain, vaginal bleeding, itching of vulva, pregnancy itching, leg cramps, uterine contractions, varicose veins and sleep problems. It contained anatomic pictures, for example with arrows pointing to the location of pelvic girdle pain. Responses were categorized as “yes” or “no”.

Other information was used to adjust for potential confounding and was for this purpose arranged into three thematically ordered blocks.

Section I—“Sociodemographic” contains: age, children living at home (no, yes), marital status (married/cohabiting/other, living alone), education (none, short, middle, long), occupation (employed, unemployed, student, other), income (<39,000 €, 40,000–79,999 €, 80,000–119,999 €, ≥120,000 €, do not want to answer) and substance use during pregnancy (smoking, drinking alcohol, use of other drugs) (none, at least one).

Section II—“Physical and mental health” contains: self‐rated health (very good/good, fair/poor/very poor), self‐rated fitness (very good/good, fair/poor/very poor), previous psychological difficulties (no, yes/no healthcare, yes with healthcare), high depression score (Major depression index ≥21): (no, yes), high anxiety score (Anxiety stress scale ≥50): (no, yes), sleep problems (no, yes) and medical doctor‐reported mental diseases: (no, yes), heart disease, lung disease, thyroid disease, diabetes, epilepsy, recurrent urinary tract infections (none, at least one).

Section III—“Reproductive background” contains: parity (0, 1, more than one), previous miscarriages and abortions (0, 1, more than one) and in vitro fertilization (no, yes). Data about substance use, reported mental diseases and somatic diseases and reproductive background were obtained from the Pregnancy Health Record; all other data were from the questionnaires.

2.5. Outcome

This study investigates two outcomes: (1) whether the woman experienced serious pregnancy complications, and (2) whether the woman experienced serious birth complications. We used The Danish Medical Birth Register (MBR) 27 to identify those women in our cohort who experienced serious pregnancy or birth complications. When people in Denmark are evaluated or treated in hospital, their contact will be registered with one or several International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision (ICD‐10) diagnosis codes, used for reimbursements and statistics. We used the unique personal identification number assigned to all individuals residing in Denmark and date of delivery to link the study data to the data from the MBR. Pregnancy complications are defined by the following ICD‐10 codes: DO 10.0–36.1, birth complications by DO 60.1–75.8 and procedure code for acute cesarean MKCA 10A and E. A detailed breakdown of the above diagnoses is found in Table S1. The occurrence of ICD‐10 diagnosis codes can be found in the MBR. We recorded miscarriages as pregnancy complications and stillbirths as birth complications. Withdrawal of consent before answering the first questionnaire was an exclusion criterion for the analysis of pregnancy complications. In addition, miscarriage was an exclusion criterion for the analysis of birth complications.

2.6. Statistical analyses

Characteristics of the study population were compared between women with and those without pregnancy and birth complications, using chi‐square tests. Logistic regression analysis was used to test the associations between the early pregnancy‐related symptoms and serious complications later in pregnancy and at birth. These associations were assessed as odds ratios (OR) unadjusted, adjusted for each of three blocks individually, and adjusted for all three blocks simultaneously. The purpose of these stepwise adjustments was to see whether the additional information could explain the associations apparent in the unadjusted assessment. A p‐value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The statistical analyses were performed with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

2.7. Ethics statement

The study was registered at the Danish Data Protection Agency (Journal 2014‐41‐3018). According to Danish regulations (no. 593 of June 14, 2011), this study does not need approval from a health research ethics committee because it is based solely on register data and questionnaires.

3. RESULTS

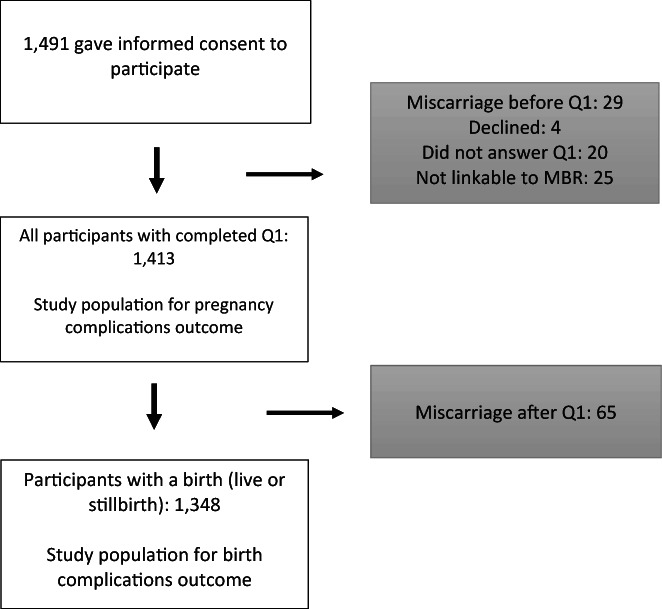

A total of 1491 pregnant women gave informed consent to participate in the study at their first prenatal care visit. A total of 78 women were excluded from the analysis (29 had a miscarriage before answering the questionnaire, four declined, 20 did not answer and 25 could not be linked to the MBR) (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart of the population with possible pregnancy and/or birth complications.

Among the 1413 included women, 199 (14%) experienced complications in later pregnancy. The most serious complication, miscarriage, was experienced by 65 women (4.6%). Other common pregnancy complications were gestational diabetes mellitus (n = 11, 0.8%), gestational hypertension without proteinuria (n = 34, 2.4%), mild to moderate preeclampsia (n = 34, 2.4%) and gestational itching with effect on liver (n = 17, 1.2%) (Table S1).

Birth complications were found in 185 (14%) of the 1348 women who gave birth. Four delivered a stillborn (0.3%) and 124 (9.2%) had an acute cesarean section. Other common complications were pyrexia during labor (n = 30, 2.2%), maternal distress during labor and delivery (n = 19, 1.4%), preterm delivery (n = 11, 0.8%) and labor after previous cesarean section (n = 10, 0.7%) (Table S1).

Table 1 compares the sociodemographic characteristics, physical and mental health, lifestyle habits and reproductive background of women with and those without pregnancy and birth complications. Women with pregnancy complications tended to have high depression scores, more often had children living at home, had given birth before and more often had experienced a previous abortion. Women with birth complications more often had children living at home and had given birth before.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of the women in the study and their associations with pregnancy complications and birth complications

| Pregnancy complications (n = 1413) | Birth complications (n = 1348) | All (n = 1413) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NO | YES | P‐value | NO | YES | P‐value | n | % | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |||||

| Age | ||||||||||||

| ≤25 years | 154 | 12.7 | 24 | 12.1 | 0.12 | 152 | 13.1 | 17 | 9.19 | 0.37 | 178 | 12.6 |

| 26–30 years | 424 | 34.9 | 62 | 31.2 | 403 | 34.7 | 69 | 37.3 | 486 | 34.4 | ||

| 31–35 years | 413 | 34.0 | 62 | 31.2 | 389 | 33.5 | 68 | 36.8 | 475 | 33.6 | ||

| ≥36 years | 223 | 18.4 | 51 | 25.6 | 219 | 18.8 | 31 | 16.8 | 274 | 19.4 | ||

| Children living at home | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 481 | 39.6 | 101 | 50.8 | 0.0031 | 448 | 38.5 | 99 | 53.5 | 0.0001 | 582 | 41.2 |

| No | 733 | 60.4 | 98 | 49.3 | 715 | 61.5 | 86 | 46.5 | 831 | 58.8 | ||

| Marital status | ||||||||||||

| Married/cohabiting/other | 1165 | 96.0 | 194 | 97.5 | 0.30 | 1115 | 95.9 | 180 | 97.3 | 0.35 | ||

| Living alone | 49 | 4.0 | 5 | 2.5 | 48 | 4.1 | 5 | 2.7 | 54 | 3.8 | ||

| Education | ||||||||||||

| None | 315 | 26.0 | 52 | 26.1 | 0.93 | 302 | 26.0 | 51 | 27.6 | 0.74 | 367 | 26.0 |

| Short | 148 | 12.2 | 27 | 13.6 | 143 | 12.3 | 27 | 14.6 | 175 | 12.4 | ||

| Middle | 463 | 38.1 | 76 | 38.2 | 444 | 38.2 | 67 | 36.2 | 539 | 38.2 | ||

| Long | 288 | 23.7 | 44 | 22.1 | 274 | 23.6 | 40 | 21.6 | 332 | 23.5 | ||

| Occupation | ||||||||||||

| Employed | 904 | 74.5 | 153 | 76.9 | 0.90 | 869 | 74.7 | 135 | 73.0 | 0.95 | 1057 | 74.8 |

| Unemployed | 66 | 5.4 | 9 | 4.5 | 63 | 5.4 | 10 | 5.4 | 75 | 5.3 | ||

| Student | 170 | 14.0 | 26 | 13.1 | 160 | 13.8 | 27 | 14.6 | 196 | 13.9 | ||

| Other | 74 | 6.1 | 11 | 5.5 | 71 | 6.1 | 13 | 7.0 | 85 | 6.0 | ||

| Income (€) | ||||||||||||

| <39,999 | 151 | 12.4 | 24 | 12.0 | 0.56 | 139 | 12.0 | 25 | 13.5 | 0.87 | 175 | 12.4 |

| 40,000–79,999 | 359 | 29.6 | 70 | 35.1 | 353 | 30.4 | 53 | 28.7 | 429 | 30.4 | ||

| 80,000–119,999 | 402 | 33.1 | 63 | 31.7 | 389 | 33.5 | 61 | 33.0 | 465 | 32.9 | ||

| ≥120,000 | 129 | 10.6 | 19 | 9.6 | 123 | 10.6 | 17 | 9.2 | 148 | 10.5 | ||

| Do not want to answer | 173 | 14.3 | 23 | 11.6 | 159 | 13.7 | 29 | 15.7 | 196 | 13.9 | ||

| Self‐rated health | ||||||||||||

| Very good/good | 966 | 79.6 | 154 | 77.4 | 0.48 | 913 | 78.5 | 152 | 82.1 | 0.26 | 1120 | 79.3 |

| Fair/poor/very poor | 248 | 20.4 | 45 | 22.6 | 250 | 21.5 | 33 | 17.8 | 293 | 20.7 | ||

| Self‐rated fitness | ||||||||||||

| Very good/good | 348 | 28.8 | 53 | 26.6 | 0.54 | 332 | 28.6 | 57 | 30.8 | 0.53 | 402 | 28.5 |

| Fair/poor/very poor | 865 | 71.3 | 146 | 73.4 | 831 | 71.5 | 128 | 69.2 | 1011 | 71.6 | ||

| Substance use | ||||||||||||

| None | 1121 | 92.3 | 190 | 95.5 | 0.11 | 1074 | 92.4 | 174 | 94.1 | 0.41 | 1311 | 92.8 |

| At least one | 93 | 7.7 | 9 | 4.5 | 89 | 7.7 | 11 | 6.0 | 102 | 7.2 | ||

| MD reported somatic diseases | ||||||||||||

| None | 977 | 80.5 | 159 | 79.9 | 0.85 | 942 | 81.0 | 142 | 76.8 | 0.18 | 1136 | 80.4 |

| At least one | 237 | 19.5 | 40 | 20.1 | 221 | 19.0 | 43 | 23.2 | 277 | 19.6 | ||

| In vitro fertilization | ||||||||||||

| No | 1095 | 90.2 | 178 | 89.5 | 0.74 | 1051 | 90.4 | 162 | 87.6 | 0.24 | 1273 | 90.1 |

| Yes | 119 | 9.8 | 21 | 10.6 | 112 | 9.6 | 23 | 12.4 | 140 | 9.9 | ||

| Previous abortions | ||||||||||||

| None | 759 | 62.5 | 122 | 61.3 | 0.0033 | 734 | 63.1 | 108 | 58.4 | 0.38 | 881 | 62.4 |

| One | 321 | 26.4 | 43 | 21.6 | 297 | 25.5 | 56 | 30.3 | 364 | 25.8 | ||

| More than one | 134 | 11.0 | 34 | 17.0 | 132 | 11.4 | 21 | 11.4 | 168 | 11.9 | ||

| Parity | ||||||||||||

| None | 529 | 43.6 | 106 | 53.3 | 0.0078 | 487 | 41.9 | 111 | 60.0 | <0.0001 | 635 | 44.9 |

| One | 473 | 39.0 | 55 | 27.6 | 453 | 39.0 | 59 | 32.0 | 528 | 37.3 | ||

| More than one | 212 | 175 | 38 | 19.1 | 223 | 19.1 | 15 | 8.1 | 250 | 17.79 | ||

| Psychiatric disease | ||||||||||||

| No | 1128 | 92.9 | 181 | 91.0 | 0.33 | 1074 | 92.3 | 175 | 94.6 | 0.28 | 1309 | 92.6 |

| Yes | 86 | 7.1 | 18 | 9.0 | 89 | 7.7 | 10 | 5.4 | 104 | 7.3 | ||

| Previous psychological difficulties | ||||||||||||

| No | 613 | 50.5 | 108 | 54.3 | 0.58 | 592 | 50.9 | 91 | 49.2 | 0.87 | 721 | 51.0 |

| Yes, no healthcare | 243 | 20.0 | 35 | 17.6 | 228 | 19.6 | 36 | 19.5 | 278 | 19.7 | ||

| Yes, with healthcare | 358 | 29.5 | 56 | 28.1 | 343 | 29.5 | 58 | 31.4 | 414 | 29.3 | ||

| Depression (MDI ≥21) | ||||||||||||

| No | 1041 | 85.8 | 161 | 80.9 | 0.076 | 987 | 84.9 | 155 | 83.8 | 0.70 | 1202 | 85.1 |

| Yes | 173 | 14.3 | 38 | 19.1 | 176 | 15.1 | 30 | 16.2 | 211 | 14.9 | ||

| Anxiety (ASS ≥10) | ||||||||||||

| No | 1107 | 91.2 | 177 | 88.9 | 0.31 | 1065 | 91.6 | 160 | 86.5 | 0.026 | 1284 | 90.9 |

| Yes | 107 | 8.8 | 22 | 11.1 | 98 | 8.4 | 25 | 13.5 | 129 | 9.1 | ||

| Sleep problems | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 966 | 79.6 | 153 | 76.9 | 0.39 | 916 | 78.8 | 147 | 79.5 | 0.83 | 1119 | 79.2 |

| No | 248 | 20.4 | 46 | 23.1 | 247 | 21.2 | 38 | 20.5 | 294 | 20.8 | ||

Table 2 shows the occurrence of self‐reported pregnancy‐related physical symptoms in the first trimester in relation to serious complications later in pregnancy and at birth. The most common symptoms in early pregnancy were nausea (88%), pelvic cavity pain (56.28%), vomiting (40.0%), back pain (37.7%) and pelvic girdle pain (33.4%).

TABLE 2.

The prevalence of self‐reported pregnancy‐related physical symptoms, classified by later pregnancy and birth complications in the same pregnancy among the pregnant women in first trimester

| Pregnancy complication (n = 1413) | Birth complications (n = 1348) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NO | YES | NO | YES | All | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Pregnancy symptoms | ||||||||||

| Nausea | 1073 | 88.4 | 170 | 85.4 | 1032 | 88.7 | 162 | 87.6 | 1243 | 88.0 |

| Vomiting | 488 | 40.2 | 77 | 38.7 | 464 | 39.9 | 85 | 46.0 | 565 | 40.0 |

| Back pain | 454 | 37.4 | 78 | 39.2 | 425 | 36.5 | 81 | 43.8 | 532 | 37.7 |

| Pelvic girdle pain | 388 | 32.0 | 84 | 42.2 | 381 | 32.8 | 70 | 37.8 | 472 | 33.4 |

| Pelvic cavity pain | 665 | 54.8 | 129 | 64.8 | 643 | 55.3 | 109 | 58.9 | 794 | 56.2 |

| Vaginal bleeding | 201 | 16.6 | 46 | 23.1 | 188 | 16.2 | 36 | 19.5 | 247 | 17.2 |

| Itching of vulva | 226 | 18.6 | 35 | 17.6 | 215 | 18.5 | 38 | 20.5 | 261 | 18.5 |

| Pregnancy itching | 209 | 17.2 | 26 | 13.1 | 199 | 17.1 | 30 | 16.2 | 235 | 16.6 |

| Leg cramp | 123 | 10.1 | 17 | 8.5 | 116 | 6.0 | 18 | 9.7 | 140 | 9.911 |

| Uterine contractions | 57 | 4.7 | 7 | 3.5 | 55 | 4.3 | 8 | 4.32 | 64 | 4.5 |

| Varicose veins | 34 | 2.8 | 5 | 2.5 | 39 | 2.8 | ||||

Note: Due to low numbers, varicose veins could not be reported as birth complications.

Table 3 shows the associations between pregnancy‐related physical symptoms in the first trimester and pregnancy and birth complications. Pelvic girdle pain (p = 0.003, 95% CI 1.17–2.25), pelvic cavity pain (p = 0.012, 95% CI 1.10–2.14) and vaginal bleeding (P = 0.03, 95% CI 1.04–2.20) in early pregnancy were more common in women who later had pregnancy complications. These associations stayed statistically significant after adjustment for potential confounders grouped into the three blocks. No statistically significant associations were found between early pregnancy‐related symptoms and birth complications.

TABLE 3.

The associations between pregnancy‐related physical symptoms in the first trimester, and pregnancy and birth complications

| Pregnancy complications | Block I: Adjusted for age and sociodemograpic characteristics | Block II: Adjusted for physical and mental health and resources | Block III: Adjusted for reproductive background | Adjusted for all blocks | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | OR [95%CI] | P‐value | OR [95%CI] | P‐value | OR [95%CI] | P‐value | OR [95%CI] | P‐value | OR [95%CI] | P‐value |

| Nausea | 0.77 [0.50–1.19] | 0.24 | 0.82 [0.53–1.28] | 0.39 | 0.76 [0.49–1.19] | 0.23 | 0.74 [0.48–1.15] | 0.19 | 0.75 [0.47–1.18] | 0.20 |

| Vomiting | 0.94 [0.69–1.28] | 0.69 | 0.98 [0.72–1.35] | 0.91 | 0.95 [0.70–1.30] | 0.75 | 0.91 [0.67–1.24] | 0.55 | 0.96 [0.70–1.33] | 0.82 |

| Back pain | 1.08 [0.79–1.47] | 0.63 | 1.09 [0.79–1.50] | 0.58 | 1.09 [0.79–1.49] | 0.60 | 1.04 [0.76–1.42] | 0.83 | 1.06 [0.76–1.47] | 0.74 |

| Pelvic girdle pain | 1.55 [1.14–2.11] | 0.005 | 1.65 [1.20–2.26] | 0.002 | 1.55 [1.13–2.12] | 0.01 | 1.56 [1.14–2.13] | 0.005 | 1.62 [1.17–2.25] | 0.003 |

| Pelvic cavity pain | 1.52 [1.11–2.08] | 0.008 | 1.50 [1.09–2.07] | 0.01 | 1.47 [1.06–2.03] | 0.02 | 1.53 [1.11–2.10] | 0.01 | 1.53 [1.10–2.14] | 0.012 |

| Vaginal bleeding | 1.52 [1.05–2.18] | 0.03 | 1.48 [1.02–2.13] | 0.04 | 1.50 [1.04–2.17] | 0.03 | 1.54 [1.07–2.21] | 0.02 | 1.52 [1.04–2.20] | 0.03 |

| Itching of vulva | 0.93 [0.63–1.38] | 0.73 | 0.96 [0.65–1.43] | 0.85 | 0.91 [0.61–1.36] | 0.65 | 0.92 [0.62–1.37] | 0.69 | 0.93 [0.62–1.39] | 0.73 |

| Pregnancy itching | 0.72 [0.47–1.12] | 0.15 | 0.71 [0.46–1.11] | 0.14 | 0.73 [0.47–1.14] | 0.16 | 0.72 [0.46–1.12] | 0.14 | 0.72 [0.46–1.13] | 0.15 |

| Leg cramp | 0.83 [0.49–1.41] | 0.49 | 0.79 [0.46–1.37] | 0.41 | 0.84 [0.49–1.45] | 0.53 | 0.81 [0.47–1.38] | 0.44 | 0.78 [0.45–1.36] | 0.38 |

| Uterine contractions | 0.74 [0.33–1.65] | 0.46 | 0.80 [0.35–1.82] | 0.59 | 0.79 [0.35–1.79] | 0.57 | 0.76 [0.34–1.69] | 0.50 | 0.80 [0.34–1.84] | 0.59 |

| Varicose veins* | 0.89 [0.35–2.32] | 0.82 | 0.93 [0.35–2.45] | 0.88 | 0.89 [0.34–2.34] | 0.81 | 0.91 [0.35–2.36] | 0.84 | 0.84 [0.31–2.27] | 0.73 |

| Birth complications | ||||||||||

| Variable | OR [95%CI] | P‐value | OR [95%CI] | P‐value | OR [95%CI] | P‐value | OR [95%CI] | P‐value | OR [95%CI] | P‐value |

| Nausea | 0.89 [0.56–1.43] | 0.64 | 1.00 [0.62–1.63] | 1.00 | 0.93 [0.57–1.50] | 0.77 | 0.88 [0.55–1.43] | 0.61 | 1.00 [0.61–1.65] | 0.99 |

| Vomiting | 1.28 [0.94–1.75] | 0.12 | 1.31 [0.95–1.82] | 0.10 | 1.24 [0.90–1.70] | 0.19 | 1.27 [0.93–1.74] | 0.14 | 1.31 [0.94–1.82] | 0.11 |

| Back pain | 1.35 [0.99–1.85] | 0.06 | 1.36 [0.98–1.88] | 0.07 | 1.36 [0.99–1.88] | 0.06 | 1.34 [0.97–1.85] | 0.08 | 1.38 [0.98–1.93] | 0.06 |

| Pelvic girdle pain | 1.25 [0.91–1.72] | 0.17 | 1.27 [0.91–1.76] | 0.16 | 1.27 [0.92–1.77] | 0.15 | 1.22 [0.88–1.70] | 0.23 | 1.25 [0.89–1.76] | 0.20 |

| Pelvic cavity pain | 1.16 [0.85–1.59] | 0.36 | 1.06 [0.76–1.47] | 0.73 | 1.01 [0.73–1.41] | 0.94 | 1.17 [0.85–1.61] | 0.34 | 1.01 [0.72–1.42] | 0.96 |

| Vaginal bleeding | 1.25 [0.84–1.86] | 0.26 | 1.27 [0.85–1.90] | 0.25 | 1.22 [0.81–1.82] | 0.34 | 1.26 [0.85–1.88] | 0.25 | 1.26 [0.83–1.90] | 0.28 |

| Itching of vulva | 1.14 [0.77–1.68] | 0.51 | 1.17 [0.79–1.74] | 0.42 | 1.16 [0.78–1.71] | 0.47 | 1.12 [0.76–1.65] | 0.58 | 1.16 [0.77–1.74] | 0.47 |

| Pregnancy itching | 0.94 [0.62–1.43] | 0.76 | 0.90 [0.59–1.39] | 0.64 | 0.92 [0.60–1.41] | 0.72 | 0.91 [0.60–1.39] | 0.67 | 0.89 [0.57–1.38] | 0.60 |

| Leg cramp | 0.97 [0.58–1.64] | 0.92 | 0.93 [0.54–1.60] | 0.80 | 0.97 [0.57–1.66] | 0.92 | 0.95 [0.56–1.62] | 0.86 | 0.92 [0.53–1.60] | 0.7691 |

| Uterine contractions | 0.91 [0.43–1.94] | 0.81 | 1.06 [0.48–2.30] | 0.89 | 1.27 [0.58–2.78] | 0.55 | 0.93 [0.43–1.99] | 0.84 | 1.33 [0.60–2.95] | 0.4885 |

Note: Due to low numbers, varicose veins could not be reported as birth complications.

4. DISCUSSION

Our results indicate that women who experienced pelvic girdle pain, pelvic cavity pain and vaginal bleeding in the first trimester in pregnancy had a higher risk of complications later on in the pregnancy. None of the other symptoms investigated in early pregnancy was associated with later pregnancy complications. There were no associations between birth complications and pregnancy‐related physical symptoms in the first trimester.

Only a few studies have assessed the associations between common symptoms in early pregnancy and outcome. Our finding of an increase in overall risk of antenatal complications in women experiencing pelvic girdle pain and pelvic cavity pain in the first trimester is consistent with a previous prospective cohort study of women recruited through a pregnancy unit in secondary care. 28 Our study is also in accordance with a longitudinal cohort study from the Netherlands which found no association between pelvic girdle pain and obstetric factors, but did find more comorbidity and depressive symptoms in the group with pain. 29 One study exploring sub‐chorionic hematomas among pregnant women with vaginal bleeding showed that the ratio of pregnancy loss was higher among women who had nonspecific pelvic pain. 30 Pain symptoms with a different etiology are, however, likely to be prevalent, which makes pelvic pain less useful as a clinical predictor.

Our finding that vaginal bleeding in early pregnancy is a risk factor for adverse obstetric and perinatal outcome is well known. Women with vaginal bleeding have twice the risk of low birthweight 31 and an increased risk of antepartum hemorrhage, preterm rupture of membranes, preterm delivery, intrauterine growth restriction and perinatal mortality. 32 , 33 Therefore, it is highly appropriate to refer pregnant women experiencing vaginal bleeding to ultrasound to check up for extrauterine pregnancy or ongoing or missed miscarriage, as stipulated in current Danish guidelines. 34

This study offered a unique opportunity to identify the source population, because almost all pregnant women in Denmark contact their GP in early pregnancy, and first pregnancy consultations are registered in a national database based on reimbursement data provided by GPs. 35 Great effort was put into recruiting and obtaining responses from the pregnant women, and no exclusion criteria were used in recruitment. 35 A recruitment bias might be present, as the GPs might not have recruited all available women, and women who did not read Danish well might not have participated. This deviation from a representative sample of pregnant women in Denmark affects prevalence data but should not affect the studied associations between symptoms and outcomes. Still, this pregnancy study offered a unique opportunity to identify the source population because almost all pregnant women in Denmark contact their GP in early pregnancy, and first pregnancy consultations are registered in a national database based on reimbursement data provided by GPs. There were very few non‐responders among those who agreed to participate, and complete data were obtained from almost all participants who were recruited to the study at the first pregnancy consultation. Furthermore, information on pregnancy and birth complications was studied using the Danish national register, the MBR. The main strength of the MBR is the exhaustive coverage of all births in Denmark. 36

The questionnaires were supposed to be obtained directly after the first pregnancy consultation in weeks 6–10. The fast responders may not have had time to experience any of the pregnancy‐related symptoms, and women who had to receive reminders had more time to experience pregnancy‐related symptoms, but less time to experience pregnancy complications, or may have left the study because of pregnancy complications. Because of this spread, there is an artificial tendency for the presence of symptoms to be associated with fewer pregnancy complications; this biases the associations conservatively. Furthermore, confounding does not seem to explain the associations that we found. We adjusted for a large set of potential confounders and this did not appear to have a significant effect compared with the unadjusted estimates. Hence, we cannot point to specific areas (ie the three thematic blocks) that confound the associations.

The women were asked to grade the severity of the symptoms if they were present, but the grading was not used in the present analysis. Perceptions of severity differ between women, making this information subjective, and fragmenting the analysis would result in weaker inference. Hence, we analyzed the mere presence of the symptom as a more robust indicator with stronger inference.

The codes in the Pregnancy Health Record do not distinguish between incident and prevalent conditions and it was, therefore, not possible to exclude women with preexisting conditions. Our aim is to investigate the value of symptoms as indicators of need for increased attention, and pre‐existing conditions are not to be neglected as targets of this care. We opted to pool the various types of complications into single outcomes of general complications or conditions that possibly need attention. Analyses on the individual complications decrease the frequencies of each of the outcomes and spread the analyses thinly over multiple outcomes. This lowers the power of the individual analysis and calls for multiple testing adjustments, which would generally lower the probability of detecting associations. However, some existing associations may be missed because of an inflated variance in the pooled outcome. As our aim is to investigate the usefulness of symptoms as signs for increased attention, regardless of mechanisms and etiology, we found it pertinent to pool the complications as we view these rather as signs of the doctor indicating there is a problem than an actual diagnosis of disease.

5. CONCLUSION

Symptoms in early pregnancy are common and do not often signal a potential risk of severe pregnancy or birth complications, although pain and bleeding may give some cause for concern. This is a clinically important message for women experiencing symptoms and for their caregivers.

FUNDING INFORMATION

Novo Nordisk Fund, NNF130C0002689; Region Zealand, 15–000342; Danish General Practice Fund, EMN‐2017‐00265; A.P. Møllers Fund, 16–87; Lilly and Herbet Hansens Fund, 082; Jacob and Orla Madsens Fund, 5421. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the funders.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

Supporting information

Table S1

Ertmann RK, Nicolaisdottir DR, Kragstrup J, Overbeck G, Kriegbaum M, Siersma V. The predictive value of common symptoms in early pregnancy for complications later in pregnancy and at birth. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2023;102:33‐42. doi: 10.1111/aogs.14474

REFERENCES

- 1. Gon G, Leite A, Calvert C, Woodd S, Graham WJ, Filippi V. The frequency of maternal morbidity: a systematic review of systematic reviews. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018;141(Suppl 1):20‐38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lutterodt MC, Kahler P, Kragstrup J, Nicolaisdottir DR, Siersma V, Ertmann RK. Examining to what extent pregnancy‐related physical symptoms worry women in the first trimester of pregnancy: a cross‐sectional study in general practice. BJGP Open. 2019;3(4), s 1‐9. doi: 10.3399/bjgpopen19X101674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lindenskov L, Kristensen FB, Andersen AM, et al. Preventive check‐ups of pregnant women in Denmark. Common ailments in pregnancy. Ugeskr Laeger. 1994;156:2897‐2901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nazik E, Eryilmaz G. Incidence of pregnancy‐related discomforts and management approaches to relieve them among pregnant women. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23:1736‐1750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zib M, Lim L, Walters WA. Symptoms during normal pregnancy: a prospective controlled study. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;39:401‐410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. James S. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392:1789‐1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gadsby R, Barnie‐Adshead AM, Jagger C. A prospective study of nausea and vomiting during pregnancy. Br J Gen Pract. 1993;43:245‐248. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chortatos A, Haugen M, Iversen PO, et al. Pregnancy complications and birth outcomes among women experiencing nausea only or nausea and vomiting during pregnancy in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. O'Brien B, Naber S. Nausea and vomiting during pregnancy: effects on the quality of women's lives. Birth. 1992;19:138‐143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chou FH, Avant KC, Kuo SH, Fetzer SJ. Relationships between nausea and vomiting, perceived stress, social support, pregnancy planning, and psychosocial adaptation in a sample of mothers: a questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2008;45:1185‐1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kuo SH, Wang RH, Tseng HC, Jian SY, Chou FH. A comparison of different severities of nausea and vomiting during pregnancy relative to stress, social support, and maternal adaptation. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2007;52:e1‐e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Einarson TR, Piwko C, Koren G. Quantifying the global rates of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: a meta analysis. J Popul Ther Clin Pharmacol. 2013;20:e171‐e183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lambert J. Pruritus in female patients. Biomed Res Int 2014;2014:541867, 1, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Klufio CA, Amoa AB, Delamare O, Hombhanje M, Kariwiga G, Igo J. Prevalence of vaginal infections with bacterial vaginosis, Trichomonas vaginalis and Candida albicans among pregnant women at the Port Moresby General Hospital Antenatal Clinic. P N G Med J. 1995;38:163‐171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hasan R, Baird DD, Herring AH, Olshan AF, Jonsson Funk ML, Hartmann KE. Patterns and predictors of vaginal bleeding in the first trimester of pregnancy. Ann Epidemiol. 2010;20:524‐531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Glowacka M, Rosen N, Chorney J, Snelgrove Clarke E, George RB. Prevalence and predictors of genito‐pelvic pain in pregnancy and postpartum: the prospective impact of fear avoidance. J Sex Med. 2014;11:3021‐3034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vleeming A, Albert HB, Ostgaard HC, Sturesson B, Stuge B. European guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pelvic girdle pain. Eur Spine J. 2008;17:794‐819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gutke A, Olsson CB, Völlestad N, Öberg B, Wikmar LN, Robinson HS. Association between lumbopelvic pain, disability and sick leave during pregnancy – a comparison of three Scandinavian cohorts. J Rehabil Med. 2014;46:468‐474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kanakaris NK, Roberts CS, Giannoudis PV. Pregnancy‐related pelvic girdle pain: an update. BMC Med. 2011;9:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vermani E, Mittal R, Weeks A. Pelvic girdle pain and low back pain in pregnancy: a review. Pain Pract. 2010;10:60‐71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ertmann RK, Nicolaisdottir DR, Kragstrup J, Siersma V, Lutterodt MC. Sleep complaints in early pregnancy. A cross‐sectional study among women attending prenatal care in general practice. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20:123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Byatt N, Hicks‐Courant K, Davidson A, et al. Depression and anxiety among high‐risk obstetric inpatients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36:644‐649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Geier ML, Hills N, Gonzales M, Tum K, Finley PR. Detection and treatment rates for perinatal depression in a state medicaid population. CNS Spectr. 2015;20:11‐19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gold LH. Postpartum disorders in primary care: diagnosis and treatment. Prim Care. 2002;29:27‐41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wylie L, Hollins Martin CJ, Marland G, Martin CR, Rankin J. The enigma of post‐natal depression: an update. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2011;18:48‐58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ertmann RK, Nicolaisdottir DR, Kragstrup J, Siersma V, Lutterodt MC, Bech P. Physical discomfort in early pregnancy and postpartum depressive symptoms. Nord J Psychiatry. 2019;73:200‐206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bliddal M, Broe A, Pottegard A, Olsen J, Langhoff‐Roos J. The Danish medical birth register. Eur J Epidemiol. 2018;33:27‐36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Al‐Memar M, Vaulet T, Fourie H, et al. Early‐pregnancy events and subsequent antenatal, delivery and neonatal outcomes: prospective cohort study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2019;54:530‐537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Van De Pol G, Van Brummen HJ, Bruinse HW, Heintz AP, Van Der Vaart CH. Pregnancy‐related pelvic girdle pain in The Netherlands. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007;86:416‐422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Karaçor T, Bülbül M, Nacar MC, Kırıcı P, Peker N, Ağaçayak E. The effect of vaginal bleeding and non‐spesific pelvic pain on pregnancy outcomes in subchorionic hematomas cases. Ginekol Pol. 2019;90:656‐661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. van Oppenraaij RH, Jauniaux E, Christiansen OB, Horcajadas JA, Farquharson RG, Exalto N. Predicting adverse obstetric outcome after early pregnancy events and complications: a review. Hum Reprod Update. 2009;15:409‐421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Saraswat L, Bhattacharya S, Maheshwari A, Bhattacharya S. Maternal and perinatal outcome in women with threatened miscarriage in the first trimester: a systematic review. BJOG. 2010;117:245‐257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lykke JA, Dideriksen KL, Lidegaard Ø, Langhoff‐Roos J. First‐trimester vaginal bleeding and complications later in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:935‐944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. The Danish National Board of Health. Bleeding during pregnancy [Blødning i graviditeten ‐ Lægehåndbogen på sundhed.dk]. [https://www.sundhed.dk/sundhedsfaglig/laegehaandbogen/obstetrik/symptomer‐og‐tegn/bloedning‐i‐graviditeten/]

- 35. Ertmann RK, Nicolaisdottir DR, Kragstrup J, et al. Selection bias in general practice research: analysis in a cohort of pregnant Danish women. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2020;38:464‐472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Schmidt M, Schmidt SA, Sandegaard JL, Ehrenstein V, Pedersen L, Sørensen HT. The Danish National Patient Registry: a review of content, data quality, and research potential. Clin Epidemiol. 2015;7:449‐490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1