Abstract

Introduction

Doctors experience barriers in consultations that compromise engaging with patients on sensitive topics and impede history taking for sexual dysfunction.

Aim

The aim of the study was to identify barriers to and facilitators of sexual history taking that primary care doctors experience during consultations involving patients with chronic illnesses.

Methods

This qualitative study formed part of a grounded theory study and represents individual interviews with 20 primary care doctors working in the rural North West Province, South Africa. The doctors were interviewed on the barriers and facilitators of sexual history taking they experienced during 151 recorded consultations with patients at risk of sexual dysfunction. Interviews were transcribed and line-by-line verbatim coding was done. A thematic analysis was performed using MaxQDA 2018 software for qualitative research. The study complied with COREQ requirements.

Outcome

Doctors’ reflections on sexual history taking.

Results

Three themes identifying barriers to sexual history taking emerged, namely personal and health system limitations, presuppositions and assumptions, and socio-cultural barriers. The fourth theme that emerged was the patient-doctor relationship as a facilitator of sexual history taking. Doctors experienced personal limitations such as a lack of training and not thinking about taking a history for sexual dysfunction. Consultations were compromised by too many competing priorities and socio-cultural differences between doctors and patients. The doctors believed that the patients had to take the responsibility to initiate the discussion on sexual challenges. Competencies mentioned that could improve the patient-doctor relationship to promote sexual history taking, include rapport building and cultural sensitivity.

Clinical implications

Doctors do not provide holistic patient care at primary health care settings if they do not screen for sexual dysfunction.

Strength and limitations

The strength in this study is that recall bias was limited as interviews took place in a real-world setting, which was the context of clinical care. As this is a qualitative study, results will apply to primary care in rural settings in South Africa.

Conclusion

Doctors need a socio-cognitive paradigm shift in terms of knowledge and awareness of sexual dysfunction in patients with chronic illness.

Pretorius D, Mlambo MG, Couper ID. “We Are Not Truly Friendly Faces”: Primary Health Care Doctors’ Reflections on Sexual History Taking in North West Province. Sex Med 2022;10:100565.

Key Words: Cultural barriers, Patient-doctor relationship, Sexual history taking, Sexual dysfunction, Clinical priorities, Barriers, Vygotsky

INTRODUCTION

South Africa has a history of conservative values where sexuality is often perceived as shameful and heteronormative.1 With the first announcement on AIDS in 1982, sexuality–especially sexual risk behavior and HIV, became part of public discussions. In South Africa, various media and health promotion campaigns were launched after 1991 to improve awareness and prevention of the disease.2 This not only created awareness in doctors and patients around the illness, but also the expectation that health care workers and patients would talk comfortably about sexual health. Sexual health forms the core of the burden of disease in South Africa, and includes women's and men's sexual health, sexually transmitted infections, gender-based sexual exploitation due to poverty and hunger, sexual violence and rape.3,4 The expectation was that the presumed comfort talking about HIV, would also open the door for raising concerns about sexual functioning.5 Lewis and Bor6 postulated that patients often used undifferentiated complaints, chronic disease and/or a request for medication as a so-called “ticket of admission” to discuss sexual functioning; a mere request for a repeat of a script for medication in primary care could trigger a discussion on sexual challenges. However, globally, studies have suggested that sexual history taking was often neglected in the scope of a primary care consultation.7, 8, 9 The question therefore was, what were doctors’ views on taking a sexual history and the factors they experience during routine consultations in primary care that could promote or limit sexual history taking.

Globally, it is known that health care workers attribute the omission of taking a sexual history to feelings of embarrassment and discomfort.9,10 This discomfort often originates from the age and gender discordance between the professionals and patients.11, 12, 13 Other barriers to sexual history taking are time constraints, knowledge of sexual dysfunction and how to initiate a discussion about sexual health.10,11,13, 14, 15 There is also evidence that undergraduate and post graduate training fails to empower doctors with the knowledge and skills to explore and manage sexual dysfunction confidently.16, 17, 18, 19, 20 Cultural and religious factors, either due to the conservative climate they create, or perceived differences and expectations between patient and doctor, can inhibit the free discussion of sexual health.21, 22, 23, 24 Some studies suggested that the doctor's personality could prevent sexual history taking.25, 26, 27 A lack of awareness of or underestimating sexual health challenges, failing to pick up cues patients give or a lack of patient centeredness also contributed to the omission of sexual history taking.28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33 Furthermore, a lack of management options was identified by some researchers as a barrier to sexual history taking.12,34 In addition, the demarcation of sexual medicine can also either inhibit or promote discussion of sexual challenges. In a study conducted in Korea, Taiwan and Singapore, 648 of 810 (80%) of the doctors spontaneously associated men's sexual health as a domain of urology.10 The same study found that doctors often associated men's sexual health in Asia mainly with diabetes (65%) and hypertension (61%) and therefore did not screen routinely for sexual dysfunction.10 A qualitative study with middle aged women in Sweden suggested that women thought that sexual problems fall in the domain of a gynecologist and would thus not raise it with their general practitioner.27 In Africa, women often do not even know that sexual dysfunction is a medical condition, whilst others seek help in traditional medicine that may even be harmful.35,36

Till now, South Africa had no research studies on sexual history taking and the barriers that doctors experienced when taking a sexual history. Most previous studies on the barriers to sexual history taking were quantitative and these surveys relied on recall of what the doctors thought they did, which may differ from actual practice. The current study sought to limit this type of recall bias by first observing consultation practice and then discussing barriers the sexual history taking barriers they experienced during the consultations

This article represents part of a broader study on observed sexual history taking using recorded primary care consultations with patients at risk of sexual dysfunction due to diabetes and hypertension. Following recorded consultations, the doctors had an opportunity to express their opinions and perceptions about factors that either promote or prevent sexual history taking during a routine consultation. The aim of the study was to identify barriers to and facilitators of sexual history taking that primary care doctors experienced during the recorded consultations involving patients with chronic illnesses.

Research Methods and Design

This was a grounded theory study to describe sexual history taking in primary care chronic consultations with patients at risk of sexual dysfunction.37 The individual interviews method was selected as it provides a broad basis of information; uncovers subtleties in attitudes and allows personal opinions from participants which may not be raised in a group.38,39 The researcher interviewed the doctors individually at the end of the recorded consultations to debrief them and to explore barriers to and facilitators of sexual history taking that they experienced during these recorded consultations.

Setting

The study was carried out in the rural Dr Kenneth Kaunda Health District in the North West Province, South Africa. In this district, just over 700 000 inhabitants are served by 1 regional and 3 district hospitals, as well as 9 community health centers and 27 clinics.40 Twenty-eight doctors worked in primary care at the time of the data collection and each doctor consulted up to 25 patients per day. The doctors in primary care consists of Family Physicians, registrars in Family Medicine, a few career senior medical officers, and the medical interns, who after graduating, are physicians in a vocational training program. The composition of these doctors (specialist/registrar/medical officer/intern-patient ratio-is consistent between and within the provinces. As these doctors do not report to the university and the findings of the study were reported in the form of articles, there was no conflict of interest or power imbalance in terms of reporting lines or disclosure of results, respectively.

Study Population and Sampling

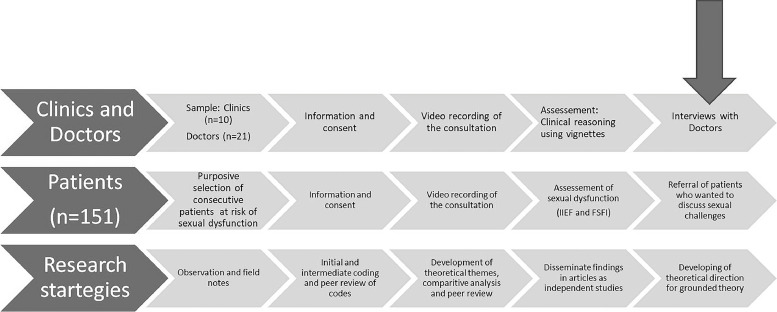

One-hundred-and-fifty-one consecutive consultations with patients theoretically at risk of sexual dysfunction due to diabetes and hypertension (Figure 1) formed the basis of this study. All the doctors working in primary care were recruited for this study. Family Physicians were excluded as they work with the researcher and the researcher-participant relationship as well as the nature of the study could be compromised if they were included. Twenty-one doctors consented to participate in the study. One doctor was subsequently excluded from the interviews due to illness.

Figure 1.

The research process from recruitment to reporting.

Data Collection

Written informed consent was obtained from the doctors for a face-to-face interview after the recording of the routine consultation; initial consent blinded the focus on sexual history taking. Solo doctors were interviewed at the end of the working day following the recording of the consultations. At the group practice, the interviews were only conducted after the completion of the recordings which took 12 working days, to avoid the doctors speaking to each other. Interviews were then scheduled at the convenience of the doctor either during lunch breaks or the end of the working day.

An interview guide gave the same opening statement for all the interviews. In the opening statement, the researcher gave the doctors an overview of the prevalence of sexual dysfunction in patients with diabetes and hypertension as well as research findings on patients’ wishes to discuss sexual dysfunction with their doctors. The focus of the research study namely, sexual history taking for sexual dysfunction was unblinded at that point. The doctors were then asked to share their experiences during the recording of the consultations and were offered the opportunity to view their recordings. The researcher asked probing questions about the barriers and facilitators of sexual history taking, as well as training the doctors had regarding these. A short summary of the interview at the end of the session gave the doctors the opportunity to clarify the content of the discussion. Field notes were recorded during the entire study.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to present demographic characteristics. A trained research assistant and a transcriber both transcribed the interviews to improve accuracy because of poor sound quality. The researcher verified the transcriptions, after which they were analyzed using MaxQDA 201841 qualitative software. The research team reviewed the coding categories (member check) and data saturation and any differences in coding were discussed until consensus was reached and the final themes were generated. The researcher did the coding in 3 phases with continuous re-assessment of the meaning of the data.42 Initial in vivo line-by-line coding was done using the doctors’ words to develop categories of the data. Focused coding followed to identify relationships between the categories, after which theoretical themes emerged. Content analysis was also performed to determine the response frequency of specific sub-themes. Excerpts from participants formed the core of the data. This study contributed to the development of the theoretical direction for a theory on sexual history taking.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee (Medical) of the University of Witwatersrand (M160557), and the Directorate: Policy, Planning, Research, Monitoring and Evaluation of the Department of Health, North West Province, South Africa. The Facility managers also granted permission to conduct the study. The research focus was blinded for participants, but they were given the option to withdraw after it was unblinded. In addition to the study being voluntary for participants, and due to the sensitive nature of the study as well as the small number of doctors, consideration was given to confidentiality and anonymity.43 Doctors often rotated through these settings, and because specific times and dates were not reported, traceability or linking doctors to their setting at the time of data collection was not possible.

RESULTS

Participants’ Demographics

Fourteen male and 6 female doctors participated in the study. The age range for men was 25–67 (mean 41) years and for women 28–34 (mean 29) years. The mean work experience for women was 4 years compared to 13 years for men. There were variations in terms of first language speakers: 6 (30%) spoke Afrikaans, 6 (30%) French, 3 (15%) Setswana, 2 English (10%), and 1 each Sesotho, Spanish, and Mandarin. Patient-doctor consultations are mainly in English. Ten doctors (50%) received their medical training in South Africa. Five of the women (83%) confirmed that they were always comfortable to talk about sexual dysfunction versus 11 of the men (79%).

Summary of Themes and Sub-Themes

Three themes represented barriers to sexual history taking, namely personal limitations, consultation process, and socio-cultural barriers (Table 1). The patient doctor relationship was mentioned as a facilitator of sexual history taking.

Table 1.

Summary of themes and sub-themes

| Themes | Sub-themes |

|---|---|

| Personal and health system limitations as a barrier to history taking for sexual dysfunction. | Forgotten subject. Doctors do not even think of sexual dysfunction. (17 responses) |

| Insufficient training Insufficient training, knowledge and/or skill to deal with sexual dysfunction screening or management. (12 responses) |

|

| Lack of resources The prescribed medication lists that do not have medicine for sexual dysfunction. (9 responses) |

|

| Presuppositions and assumptions as a barrier to history taking for sexual dysfunction. | Competing clinical priorities Doctors’ understanding of the priority tasks linked to addressing the clinical needs of their patients. (12 responses) |

| Perception of patient responsibility Doctor expected the patient to take responsibility for the discourse on sexual functioning. (15 responses) |

|

| Positive focus The doctors’ attempts to focus on positive aspects of the illness and management. (3 responses) |

|

| Socio-cultural differences as a barrier to history taking for sexual dysfunction. | Doctor-patient characteristic differences Personal characteristics that differ between patients and doctors. (4 responses) |

| Taboo topic Value system prevents doctor talking about sexual matters. (2 responses) |

|

| Patient- doctor Relationship as a facilitator of history taking for sexual dysfunction. | Rapport building The ability to connect with the patient. (6 responses) |

| Cultural sensitivity Cultural backgrounds differ and influence patients on the way they narrate their symptoms. (2 responses) |

Theme 1

: Personal and health system limitations as a barrier to sexual history taking for sexual dysfunction

The doctors had consensus on the personal limitations theme. They expressed their perspectives that sexual dysfunction was a forgotten subject, and that they had insufficient training for the task.

Sub-theme 1.1

-Forgotten subject as a personal limitation:

Doctors admitted that they do not even think of sexual dysfunction.

“I think we forget about it. It's not good. Neh? It's not good. [I] do not know why we don't ask the patients about it.”

(Dr 13, 27-year-old man).

“No ….we do not do it [chuckles] I do not even think of it [sexual history taking]…I regularly ask about HIV and STI, but not about sexual dysfunction.”

(Dr 05, 46-year-old man).

“So they [patients] don't really over share and with the doctors I don't…you're not really trained to go ask a sexual history every time, so it's usually last and forgotten.”

(Dr 09, 31-year-old woman).

Sub-theme 1.2

-Insufficient training as a personal limitation:

The doctors believed they had insufficient training, knowledge and/or skills to deal with sexual dysfunction screening or management.

“Yes. Because in my book [textbook] it's a small paragraph. I went to read it out because a patient asked me when I was in the peripheral clinics, and then I told him I'd help him, but what I knew… it's very limited.”

(Dr 08, 34-year-old woman).

“I know nothing of sexual dysfunction…perhaps a little more about erectile dysfunction.”

(Dr 11, 26-year-old woman).

“If it's an erectile dysfunction, then that I have some idea but to be honest, anything other than that, not really…not really. To be honest, I haven't had any training and that… like I would maybe try and provide support from my knowledge as like, you know, human being to human being, but on a medical level …We were taught it, ja…more for sexually…infectious diseases.”

(Dr 01, 37-year-old man).

“We did learn about this. [Interruption]…. Very little. I think that if one was more vigilant …. I think that the more you deal with this, you'll be more competent and then you'll be more into it.”

(Dr 12, 31-year-old woman).

Sub-theme 1.3

-Lack of resources as a barrier in the consultation process:

The doctors do not have drugs available that they can offer to patients with sexual dysfunction.

“At Urology for example, some men have erectile dysfunction. Then all we can say is ‘Sorry. We don't have the medication here so if you want it, here is a private script. You will have to buy it yourself’. But then you have to do certain tests to see that he doesn't get a heart attack.”

(Dr 12, 31-year-old woman).

“I am an old hand at it. It is the old people who complain, and I tell them, you had your chance, you must rest now [laughs]. We cannot help them, and they cannot afford a private script.”

(Dr 16, 67-year-old man).

Theme 2

: Presuppositions and assumptions as a barrier to sexual history taking for sexual dysfunction.

Attitude and personal priority setting are barriers to sexual history taking due to competing priorities, the patient's role and responsibility as well as a need to convey positive messages.

Sub-theme 2.1

-Competing clinical priorities as a barrier in the consultation process:

Doctors felt that they needed to give priority to tasks linked to addressing the clinical needs of their patients, especially in a context of perceived limited time.

“I don't think it is a priority because at that stage there are more important issues that first need to be addressed and I think the patients feel the same.”

(Dr 12, 31-year-old man).

“We manage end organ damage. We will pick it up. It is just not priority. If it was important, patients will complain about it.”

(Dr 15, 46-year-old man).

“I think that's why now we are not doing the proper thing… We have to do that, but I think the queues and number of patients makes it difficult for us.”

(Dr 07, 47-year-old man).

Sub-theme 2.2

-Perception of patient responsibility as a consultation barrier:

The doctor expected the patient to take responsibility of the discourse on sexual functioning.

“Ja, I hope that they will actually bring it up in the conversation. I think… they don't necessarily know that these diseases might affect their sexual health or function. So, I think that makes it difficult.”

(Dr 10, 26-year-old man).

“They come with the main complaint; they stick to the main complaint until you start asking further questions then you'll find out more information from them. ….Hmm…I think it's more of patients not being relevant. I think if it is the main complaint, it's the one that we'll need to explore the sexual health or not.”

(Dr 03, 35-year-old man).

“I think…[laughs]…I don't also ask myself unless they complain about it.”

(Dr 13, 27-year-old man).

Sub-theme 2.4

-A need to convey positive messages as consultation barrier:

Doctors described how they attempt to focus on positive aspects of the illness and management, and thus avoid talking about complications of diseases or side-effects of their treatment.

“…before giving the patient that medication we'll tell the patient this will help you…like we'd rather tell him about the advantages of taking that medication unlike the side effects... Because if they know that it will cause sexual dysfunction, they won't take the medication, they rather be bulls than having a diabetes.”

(Dr 01, 37-year-old man).

“We only talk positive things. Patients must not know too much otherwise they will have all the side effects.”

(Dr 16, 67-year-old man).

“…If I prescribe something like a beta blocker, or [brand name for anti-epileptic treatment], for a patient, I do not discuss with him the fact that it can affect the desire and the performance…I never had patients complaining about those side effects – it is rare.”

(Dr 17, 25-year-old man).

Theme 3

: Socio-cultural differences as barriers to sexual history taking for sexual dysfunction

Socio-cultural barriers like different perspectives, and sexual health as a taboo topic.

Sub-theme 3.1

-Individual differences as a socio-cultural barrier:

Doctors indicated individual characteristics that differ between patients and their doctors are a barrier.

“It is sometimes difficult when it is an older patient and then I am not at ease. One does not want to feel embarrassed, then you avoid it.”

(Dr 05, 46-year-old man).

“With males it becomes easy compared to female patients.”

(Dr 07, 47-year-old man).

A doctor narrated how she communicated with the patient on his preference for a same sex doctor:

“I saw a patient with low libido, the first thing he asked: where is the male doctor? Because I have a secret with you. Like what secret [I asked]. The secret down there. And I was like, okay, it's fine, you can see the male doctor.”

(Dr 08, 34-year-old woman).

Sub-theme 3.2

-A taboo topic as a socio-cultural barrier:

Sexuality was described by some doctors as a taboo topic because of a value system that prevents talking about it.

“It's something that…I don't know, I still grew up with, you don't talk about it. And I know it's much better now, but for me it's just…it's the unconscious decision that I don't…I don't even think about it. And I know you should and when they bring it up, you're there…or I try to deal with it [laughs]. I struggle.”

(Dr 04, 25-year-old man).

“We never ask. Besides, I do not know if it is good to discuss such sensitive issues.”

(Dr 14, 39-year-old man).

Theme 4

: Patient-doctor relationship as a facilitator of sexual history taking

The patient-doctor relationship was described as a facilitator of history taking for sexual dysfunction. It can improve the connection with the patient and enable doctors to be culturally sensitive.

Sub-theme 4.1

-Rapport building as a facilitator of the patient-doctor relationship:

Some doctors described the need to develop rapport to facilitate their ability to connect with their patients.

“Ask them how the marriage is going…then from the side to see how the relationship is going, and then…ja…from there. Or if the patient brings out that…it's usually if the patient brings it out. I haven't really elicited.”

(Dr 08, 34-year-old woman).

“…I find …you know, there's something that I mentioned just in one word, the rapport that you establish in the patient, it's so key. I've realized that when people feel more comfortable, or we try and make them feel more comfortable and you ask leading questions, they will always say, even ‘by the way there is this problem as well’.”

(Dr 15, 46-year-old man).

“The importance of working to establish rapport was emphasized in one respondent's understanding of how patients see doctors: ‘Ja…I think patients are afraid of doctors, you know…they wouldn't say much,… we are not true friendly faces.”

(Dr 06, 40-year-old man).

Sub-theme 4.2

-Cultural sensitivity as a facilitator of the patient-doctor relationship:

One doctor noted that cultural sensitivity was important to facilitate discussion on sexual dysfunction. He referred to how cultural backgrounds differ and influence the way patients narrate their symptoms.

‘…and then that one I've realized, it also depends on the tribe, like which patients you are seeing. If you see a Xhosa man, he'll tell you that, and then if you see a Sotho man, he'll start from A, then the answer is in ABC, until the end, then you get the answer…. So if you know that you are dealing with a Sotho guy, you know that you rather ask this and then the yes or no answer, unlike the explanation, because the explanation will take longer..... The whole story from childbirth [laughs].’

(Dr 03, 35-year-old man).

DISCUSSION

The aim of the study was to identify barriers to and facilitators of history taking for sexual dysfunction that doctors experienced during recorded consultations with patients who have chronic illnesses. Three themes emerged which could be considered as barriers to sexual history taking, namely doctors’ personal and health system limitations, presuppositions and assumptions, and socio-cultural differences. The fourth theme, patient-doctor relationship, could either promote or prevent sexual history taking.

Awareness of Sexual Challenges

The doctors were honest about their personal and health system limitations such as that they did not think about taking a sexual history for sexual dysfunction. The lack of resources to address sexual dysfunction also limited their awareness and willingness to address sexual dysfunction. This was evident in the outcome of the 151 recorded consultations in the broader study which preceded these interviews where no sexual history for sexual dysfunction was taken in any consultation, and only 5 (3%) of doctors attempted a history on sexual risk behaviour.37 A few other studies suggested doctors lack awareness of SD prevalence,30, 31, 32 but no other study suggested that doctors did not think about the need for a sexual history. Not thinking about it has clinical reasoning implications which by itself influence screening and management.

Priorities and Shared Decision Making: Presuppositions and Assumptions

The presuppositions and assumptions theme suggested a lack of evidence and shared decision making. Doctors did not consider sexual history taking as a clinical priority; they expected the patient to initiate the sexual health discussion and withheld information from patients regarding side effects of medicine by focusing on only positive outcomes. Salter et al.44 found in a qualitative study that the doctor played an important role in listening to patients and understanding their priorities in order to set mutually agreed upon goals for management of the illness. The assumption that sexual dysfunction is not a priority does not only suggest ignorance of sexual functioning as a biomarker of vascular and neurological complications,45 but also negate shared decision making. Despite a systematic review concluding that doctors did goal or priority setting in the intervention of multi-morbidity,46 the doctors in the current study wanted to shift the task to the patient. Similarly, doctors expected patients to raise problems about the side effects of medication, even though the doctors failed to tell the patients the truth.

Patients Must take the Lead

Interestingly, the results showed that the doctors believed patients must take the responsibility to initiate the discussion on sexual dysfunction. Thus, it seems the doctors were hiding behind their own reasons not to address sexual dysfunction, but at the same time were expecting the patients, who faced their own socio-cultural barriers, to bridge this gap for them in the consultation by initiating the discussion. Doctors 12 and 15 thought patients shared their thoughts on sexual challenges and if it was important to patients, they would raise it. Although previous studies have referred to these barriers being raised by either patients or doctors, the current study shows the interdependency of these factors in the patient-doctor dynamics, as well as that doctors focus mainly on presenting complaints. This expectation for the patient to lead the focus of the consultation must be considered in the context of the acknowledgement of an absence of openness in the doctor-patient interaction, described by Dr 06 as doctors ‘not [being] true friendly faces’. One is left asking, if there is not a cordial relationship established in the consultation, is it reasonable to expect a patient to raise sexual health concerns or is it more appropriate that the doctor, equipped with professional skills, will explore sexual dysfunction as a co-morbidity or a sign of complicated disease. This is critical in terms of sexual health, but clearly has much broader implications too.

Learning and Practice

Doctors are guided by policies and protocols that refer mostly to control targets; history taking for reproductive health and sexually transmitted infections is mentioned but not for sexual dysfunction specifically.47, 48, 49 The Society for Endocrinology and Metabolic Disease of South Africa (SEMDSA) national guidelines recommend that all adult men with type 2 diabetes must be screened regularly for erectile dysfunction by either taking a comprehensive sexual function history or using a questionnaire.47 They make no recommendations for women living with diabetes in terms of their sexual wellbeing. A previous study suggests that training on sexual history taking at tertiary training institutions also focuses more on risk reduction and not dysfunction.50 Globally there is consensus that present training on the scope of sexual health does not prepare students for practice and there is a growing need for better training in the undergraduate years.50,51 Role-modelling plays an important role in screening practices during training years.52 Alimena and Lewis53 found that when students believed that their medical school trained them well on screening techniques, and they observed a preceptor doing a screening for sexual dysfunction, they had a higher frequency of screening attempts. This means that training in the formative professional years for a doctor may facilitate a permanent mind shift towards recognizing the importance of sexual wellbeing.

The Role of Culture in Learning

Thoughts, feelings, and perceptions regarding sexual health are not only shaped by politics and social events, but also by knowledge and several layers of culture, religion, community values and beliefs.5 Age and gender differences are often raised as a problem related to sexual health issues, but not other diseases or illness. Gender roles and age gap interaction is culturally defined and rooted in upbringing.54 Culture shapes our understanding of sexuality, and our attitudes.54 Upbringing in a socio-cultural reality determines life perceptions and the decisions we make, while education instils the scientific knowledge and practice.55 Our perceptions about sexuality form during childhood when expression of sexuality is often met with sanctioning for self-exploration of the genital area; met with silence and secrecy in adolescence; for some it is even difficult to discuss sex and sexuality in the safety of the family home.28,56,57 Being a professional later, the unwritten expectation is that the doctor raised in this sexually restricted environment will automatically be professional and spontaneously discuss sexual problems. These socio-cultural barriers, which are often the basis of a difference in values between doctors and patients, then become a convenient, though unacceptable excuse for not dealing with the sexual challenges patients experience in chronic illness.

It appeared as if the barriers doctors experienced in their professional interaction with patients are sufficient justification not to think about history taking for sexual dysfunction, and thus no solution or change strategy was suggested to deal with competing priorities, time constraints or lack of resources in the current study. To cope under severe service delivery demands, a form of regulated improvisation58 results in doctors spontaneous falling back on engaging in ‘just another routine consultation’, where they do not have to address inner values or cultural conflicts on sexual dysfunction. Verplanken et al.59 summarized this as a form of automaticity where a person will repeat a specific response to a dilemma when facing the same behavioral choice–in this example, ignoring sexuality.

When patients and doctors discuss sexuality or sexual functioning, the doctors need to be culturally sensitive and manage their personal feelings. Good communication skills is the best predictor of sexual history taking60 and therefore a professional approach, good communication skills and a sound knowledge of sexual dysfunction can limit these perceived barriers. A Spanish Intersex Clinic reported how important it was for doctors to display empathy, handle fear and uncertainty, and how it shaped their behavior and clinical judgement on sexual health matters.61 The doctors who referred to rapport building and communication in the interviews, unfortunately did not demonstrate it in practice during the recorded videos. It thus seems as if there is a disconnect between knowing good practice and doing it. Not talking about sexual health seems to be related to the way these doctors related to and communicated with patients in general.37

Learning and Clinical Judgement

Thinking of clinical judgement, the knowledge of the doctors became important. The doctors’ perception that the patient must take responsibility is anchored in the belief of how sexual dysfunction should present. There was also a lack of knowledge about sexual dysfunction as a co-morbidity. Doctors’ responses suggested that they did not know the prevalence of sexual dysfunction in patients with diabetes and hypertension and believed that sexual dysfunction was limited to old age; some even displayed a condescending attitude, such as the participant who stated that ‘old people had had their chance to enjoy sex and must rest in their old age.’ Beliefs and knowledge are closely related in that beliefs become knowledge if confirmed by some scientific or normative standard. It is thus possible for doctors to think they know something and still to be wrong or just to believe they do not need more factual evidence of the perceived truths on sexual dysfunction and patient engagement.61,62 The doctors in the North West Province, South Africa, were not unique in this. A recent study of interviews with 35 primary care doctors in Trinidad and Tobago also found that doctors reported insufficient medical training and knowledge of sexual dysfunction presenting in middle and old age, had conflicting personal beliefs, and that socio-cultural factors prevented spontaneous discussions on sexuality.63

Vygotsky's Learning Theory

Learning theories such as Vygotsky's sociocultural theory suggest that learning is facilitated by the social milieu in which 1 is raised and then later inter-psychological learning takes place, where other people who are more knowledgeable or role models, shape one's thoughts and perceptions.64,65 This sociocultural theory describes a so-called zone of proximal development where optimal learning takes place which may be for doctors during their medical training years. It is during these optimal training years that the importance of a reflective understanding of the patient and diagnosis rather than just managing disease must be established.66 If doctors are trained in hypothetico-deductive history taking and scholarly reflection, combined with good communication skills, then sexual history taking and thus, patient care can improve. But most of all, it is important that in the transition phase between leaving home and becoming a professional, a doctor is taught that their sociocultural beliefs may not be the truth for all, and that patient care supersedes personal beliefs.

Strengths, Limitations and Rigor

The strength of the study is that recall bias was limited. This research study complied with the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ).67,68 Trustworthiness was secured using comprehensive data in the form of excerpts from doctors and constantly comparing the data. All the opinions were reflected irrespective if it was only 1 or more doctors expressing it. The methodology is repeatable. As these were the last data to analyze in the broader research project, and the researcher has already identified patterns indicating a theoretical direction, the researcher relied on member checks and research supervisors to present the data organized in a balanced and meaningful way. The results as discussed are limited to primary care doctors in the North West Province, South Africa, and may differ in other primary health care settings. The interviews were conducted sometimes during lunch breaks and mostly at the end of a working day, when doctors were tired, which could contribute to a loss of depth in some of the interviews. However, valuable information was gathered which revealed new ways of thinking about barriers in sexual history taking.

CONCLUSION

Doctors need a socio-cognitive and sociocultural paradigm shift in terms of the prevalence and importance of sexual dysfunction in patients with chronic illness. It is on the shoulders of educators during the undergraduate years of training to facilitate this change. If it does not happen during this optimal learning period, it is unlikely to change. Most importantly, in terms of sexual health, this requires nurturing of the understanding that sexual functioning is a core factor in psychosocial wellbeing and quality of life. Thus, it is important that training programs not only address diagnostic criteria and consultation skills but also emphasize comprehensive patient care, which include sexual wellbeing.

STATEMENT OF AUTHORSHIP

The following authors contributed the articles speaking to the research question the researcher raised: Conception and design: Pretorius D, Mlambo MG, Couper I; Acquisition of data: Pretorius D. Analysis and interpretation of data: Pretorius D, Mlambo MG, Couper I and code review with the assistance of Dreyer A, Ruch A, Lion Cachet, C and Erumeda N to improve rigor. Drafting the articles: Pretorius D. Revising for intellectual content: Couper I, Mlambo MG, Pretorius D. Final approval of the completed documents: Mlambo MG, Couper I, Pretorius D.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I thank Silindile Mbatha, research assistant and Abigail Dreyer, Neetha Erumeda, and Aviva Ruch for reviewing the coding and analysis.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Funding: None.

References

- 1.Bhana D, Crewe M, Aggleton P. Sex, sexuality and education in South Africa. Sex Educ. 2019;19:361–370. [Google Scholar]

- 2.A History of Official Government HIV/AIDS Policy in South Africa | South African History Online [Internet]. [cited 2020 Aug 19]. Available at: https://www.sahistory.org.za/article/history-official-government-hivaids-policy-south-africa

- 3.Modjadji P. Communicable and non-communicable diseases coexisting in South Africa. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9:e889–e890. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00271-0. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/langlo/article/PIIS2214-109X(21)00271-0/fulltext [cited 2021 Nov 3]. Available at: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsakok I. Food Security in the Context of COVID-19: The Public Health Challenge. The Case of the Republic of South Africa [Internet]. Africa Portal. Morocco: Policy Centre for the New South; 2020. [cited 2021 Nov 3]. Available at:https://www.africaportal.org/publications/food-security-context-covid-19-public-health-challenge-case-republic-south-africa

- 5.Edwards WM, Div M, Coleman E. Defining sexual health: a descriptive overview. Arch Sex Behav. 2004;33:189–195. doi: 10.1023/B:ASEB.0000026619.95734.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewis S, Bor R. Nurses’ knowledge of and attitudes towards sexuality and the relationship of these with nursing practice. J Adv Nurs. 1994;20:251–259. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1994.20020251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alarcão V, Ribeiro S, Miranda FL, et al. General Practitioners’ Knowledge, Attitudes, Beliefs, and Practices in the Management of Sexual Dysfunction. Results of the Portuguese SEXOS Study. J Sex Med. 2012;9:2508–2515. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Basson R, Rees P, Wang R, et al. Sexual Function in Chronic Illness. J Sex Med. 2010;7:374–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wimberly YH, Hogben M, Moore-Ruffin J, et al. Sexual history-taking among primary care physicians. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98:1924–1929. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yates M, Low WY, Rosenberg D. Physician attitudes to the concept of ‘men's health. Asia. American J Mens Health. 2008;5:48–55. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abdolrasulnia M, Shewchuk RM, Roepke N, et al. Management of female sexual problems: perceived barriers, practice patterns, and confidence among primary care physicians and gynecologists. J Sex Med. 2010;7:2499–2508. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsai YF. Nurses’ facilitators and barriers for taking a sexual history in Taiwan. Appl Nurs Res. 2004;17:257–264. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Magnan M, Reynolds K. Barriers to Addressing Patient Sexuality Concerns Across... : Clinical Nurse Specialist. Clin Nurse Spec. 2006;20:285–29214. doi: 10.1097/00002800-200611000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kingsberg S. Just ask! Talking to patients about sexual function. Sex Reprod Menopause. 2004;2:199–203. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bachmann G. Female Sexuality and Sexual Dysfunction: Are We Stuck on the Learning Curve? J Sex Med. 2006;3:639–645. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang Z, Choong DS, Ganesan AP, et al. A Survey on the Experience of Singaporean Trainees in Obstetrics/Gynecology and Family Medicine of Sexual Problems and Views on Training in Sexual Medicine. Sex Med. 2020;8:107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.esxm.2019.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kristufkova A, Pinto Da Costa M, Mintziori G, et al. Sexual Health During Postgraduate Training—European Survey Across Medical Specialties. Sex Med. 2018;6:255–262. doi: 10.1016/j.esxm.2018.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olímpio LM, Spessoto LCF, Fácio FN. Sexual health education among undergraduate students of medicine. Transl Androl Urol. 2020;9:510–515. doi: 10.21037/tau.2020.02.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sekoni AO, Gale NK, Manga-Atangana B, et al. The effects of educational curricula and training on LGBT-specific health issues for healthcare students and professionals: a mixed-method systematic review: A. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20 doi: 10.7448/IAS.20.1.21624. [Internet] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clegg M, Pye J, Wylie KR. Undergraduate Training in Evaluation of the Impact on Medical Doctors’ Practice Ten Years After Graduation. Sex Med. 2016;4:e198–e208. doi: 10.1016/j.esxm.2016.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rashidian M, Minichiello V, Knutsen SF, et al. Barriers to sexual health care: a survey of Iranian-American physicians in California, USA. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:263. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1481-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muhamad R, Horey D, Liamputtong P, et al. Managing Women with Sexual Dysfunction: Difficulties Experienced by Malaysian Family Physicians. Arch Sex Behav. 2019;48:949–960. doi: 10.1007/s10508-018-1236-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Traumer L, Jacobsen MH, Laursen BS. Patients’ experiences of sexuality as a taboo subject in the Danish healthcare system: a qualitative interview study. Scand J Caring Sci. 2019;33:57–66. doi: 10.1111/scs.12600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsimtsiou Z, Hatzimouratidis K, Nakopoulou E, et al. Predictors of Physicians’ Involvement in Addressing Sexual Health Issues. J Sex Med. 2006;3:583–588. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kitai E, Vinker S, Kijner F, et al. Erectile dysfunction—the effect of sending a questionnaire to patients on consultations with their family doctor. Fam Pract. 2002;19:247–250. doi: 10.1093/fampra/19.3.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balhara YP, Baruah M, Jumani D, et al. Consensus guidelines on male sexual dysfunction. J Med Nutr Nutraceuticals. 2013;2:5. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sarkadi A, Rosenqvist U. Contradictions in the medical encounter: female sexual dysfunction in primary care contacts. Fam Pract. 2001;18:161–166. doi: 10.1093/fampra/18.2.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Motsomi K, Makanjee C, Basera T, et al. Factors affecting effective communication about sexual and reproductive health issues between parents and adolescents in zandspruit informal settlement, Johannesburg, South Africa. Pan Afr Med J. 2016;25:120. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2016.25.120.9208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McInnes RA. Chronic illness and sexuality. MJA. 2003;179:263–266. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Byrne M, Doherty S, McGee HM, et al. General practitioner views about discussing sexual issues with patients with coronary heart disease: a national survey in Ireland. BMC Fam Pract. 2010;11:40. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-11-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boa R. Female sexual dysfunction. South Afr Med J Suid-Afr Tydskr Vir Geneeskd. 2014;104 doi: 10.7196/samj.8373. 446–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hirooka N, Lapp D. Erectile dysfunction as an initial presentation of diabetes discovered by taking sexual history. BMJ Case Rep. 2012 doi: 10.1136/bcr.12.2011.5289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berman L, Berman J, Felder S, et al. Seeking help for sexual function complaints: what gynecologists need to know about the female patient's experience. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:572–576. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)04695-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brandenburg U, Bitzer J. The challenge of talking about sex: the importance of patient–physician interaction. Maturitas. 2009;63:124–127. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ibine B, Sefakor Ametepe L, Okere M, et al. I did not know it was a medical condition: predictors, severity and help seeking behaviors of women with female sexual dysfunction in the Volta region of Ghana. PLOS ONE. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0226404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scorgie F, Kunene B, Smit JA, et al. In search of sexual pleasure and fidelity: vaginal practices in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Cult Health Sex. 2009;11:267–283. doi: 10.1080/13691050802395915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pretorius D, Couper I, Mlambo M. Sexual History Taking: Perspectives on Doctor-Patient Interactions During Routine Consultations in Rural Primary Care in South Africa. Sex Med. 2021;9 doi: 10.1016/j.esxm.2021.100389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guest G, Namey E, Taylor J, et al. Comparing focus groups and individual interviews: findings from a randomized study. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2017;20:693–708. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stokes D, Bergin R. Methodology or “methodolatry”? An evaluation of focus groups and depth interviews. Qual Mark Res Int J. 2006;9:26–37. [Google Scholar]

- 40.North West - KK Kaunda District.pdf [Internet]. [cited 2020 Mar 4]. Available at:https://www.hst.org.za/publications/NonHST%20Publications/North%20West%20-%20KK%20Kaunda%20District.pdf

- 41.Analyzing Qualitative Data with MAXQDA | SpringerLink [Internet]. [cited 2021 Nov 24]. Available at: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007%2F978-3-030-15671-8

- 42.Charmaz K. 2nd ed. SAGE; London: 2006. Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis; p. 208. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walls P, Parahoo K, Fleming P, et al. Issues and considerations when researching sensitive issues with men: examples from a study of men and sexual health. Nurse Res. 2010;18:26–34. doi: 10.7748/nr2010.10.18.1.26.c8045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Salter C, Shiner A, Lenaghan E, et al. Setting goals with patients living with multimorbidity: qualitative analysis of general practice consultations. Br J Gen Pract. 2019;69:e479–e488. doi: 10.3399/bjgp19X704129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao B, Hong Z, Wei Y, et al. Erectile Dysfunction Predicts Cardiovascular Events as an Independent Risk Factor: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Sex Med. 2019;16:1005–1017. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Collaborative goal setting with elderly patients with chronic disease or multimorbidity: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17:167. doi: 10.1186/s12877-017-0534-0. Jul 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.SEMDSA 2017 Guidelines for the Management of Type 2 diabetes mellitus. JEMDSA. 2017;22(supplement1):S1–196. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seedat Y, Rayner B, Veriava Y. South African hypertension practice guideline. SAJDVD. 2014;11:288. doi: 10.5830/CVJA-2014-062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.South Africa, Department of Health. Strategic plan: Department of Health, 2015/16 - 2019/20 [Internet]. 2014. Available at: http://pmg-assets.s3-website-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/140715strategicplan.pdf

- 50.Malhotra S, Khurshid A, Hendricks K, et al. Medical School Sexual Health Curriculum and Training in the United States. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100:1097–1106. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31452-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shindel AW, Baazeem A, Eardley I, et al. Sexual Health in Undergraduate Medical Education: Existing and Future Needs and Platforms. J Sex Med. 2016;13:1013–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.04.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wagner G. Sexual medicine in the medical curriculum. Int J Androl. 2005;28(s2):7–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2005.00581.x. [Internet][cited 2021 Jan 15] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alimena S, Lewis J. Screening for Sexual Dysfunction by Medical Students. J Sex Med. 2016;13:1473–1481. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bhavsar V, Bhugra D. Cultural factors and sexual dysfunction in clinical practice. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2013;19:144–152. Mar 1. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bayanov KR. The Function of The System “Education Plus Upbringing” In the Context of The Purpose of a Person. Ryabov VV, editor. SHS Web Conf. 2020;79:03001.

- 56.Olson MD, DeSouza E. The Influences of Socio-Cultural Factors on College Students’ Attitudes toward Sexual Minorities. J Sociol Soc Welf. 2017;44:73–94. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Reid G, Walker L. Sex and secrecy: A focus on African sexualities. Cult Health Sex. 2005;7:185–194. doi: 10.1080/13691050412331334353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Berendzen JC. Coping Without Foundations: On Dreyfus's Use of Merleau-Ponty. Int J Philos Stud. 2010;18:629–649. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Verplanken B. Beyond frequency: Habit as mental construct. Br J Soc Psychol. 2006;45:639–656. doi: 10.1348/014466605X49122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tsimtsiou Z, Hatzimouratidis K, Nakopoulou E, et al. Predictors of Physicians’ Involvement in Addressing Sexual Health Issues. J Sex Med. 2006;3:583–588. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fernández-Garrido S, Medina-Domenech RM. Bridging the Sexes’: Feelings, Professional Communities and Emotional Practices in the Spanish Intersex Clinic. Sci Cult. 2020;0:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ichikawa JJ, Steup M. In: The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy [Internet] Summer 2018. Zalta EN, editor. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University; 2018. The Analysis of Knowledge.https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2018/entries/knowledge-analysis editor. [cited 2020 Nov 27]. Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rabathaly PA, Chattu VK. An exploratory study to assess primary care physicians’ attitudes toward talking about sexual health with older patients in Trinidad and Tobago. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2019;8:626–633. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_325_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chrisman M. The Normative Evaluation of Belief and The Aspectual Classification of Belief and Knowledge Attributions. J Philos. 2012;109:588–612. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shabani K. Applications of Vygotsky’s sociocultural approach for teachers’ professional development. Ewing BF, editor. Cogent Educ. 2016;3 doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2016.1252177. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Malterud K, Reventlow S, Guassora AD. Diagnostic knowing in general practice: interpretative action and reflexivity. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2019;37:393–401. doi: 10.1080/02813432.2019.1663592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pretorius D. University of Witwatersrand; Johannesburg South Africa: 2021. Doctors’ Consultation Skills with regard to Patients’ Sexual Health in Primary Health Care Settings in North West Province. [Google Scholar]