Abstract

Borrelia hermsii, an agent of relapsing fever, undergoes antigenic variation of serotype-specifying membrane proteins during mammalian infections. When B. hermsii is cultivated in broth medium, one serotype, 33, eventually predominates in the population. Serotype 33 has also been found to be dominant in ticks but not in mammalian hosts. We investigated the biology and genetics of two independently derived clonal populations of serotype 33 of B. hermsii. Both isolates infected immunodeficient mice, but serotype 33 cells were limited in number and were only transiently present in the blood. Probes for vsp33, which encodes the serotype-specifying Vsp33 outer membrane protein, revealed that the gene was located on a 53-kb linear plasmid and that there was only one locus for the gene in serotype 33. The vsp33 probe and probes for other variable membrane protein genes showed that expression of Vsp33 was determined at the level of transcription and that when the vsp33 expression site was active, an expression site for other variable proteins was silent. The study confirmed that serotype 33 is distinct from other serotypes of B. hermsii in its biology and demonstrated that B. hermsii can change its major surface protein through switching between two expression sites.

Parasitic microorganisms have several strategies to evade their host's immune responses. One of these strategies is antigenic variation. A well-characterized example of antigenic variation occurs during relapsing fever, which is caused by several species of Borrelia (3, 7). Borrelia hermsii, an agent of tick-borne relapsing fever, uses at least three mechanisms to vary a surface protein while circulating in blood. According to the scheme described by Deitsch et al. (17), these mechanisms are gene conversion (25, 30, 34), genomic rearrangement (36, 37), and point mutations (35). Modification of transcript levels, a fourth general mechanism of antigenic variation (17), had not previously been demonstrated in relapsing fever Borrelia spp.

The B. hermsii lipoproteins affected in their expression by these genetic changes are of two types: variable large proteins (Vlp) of about 360 amino acids and variable small proteins (Vsp) of about 210 amino acids (11, 13, 14, 37). The vsp genes are orthologs of ospC of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato (15, 16, 27, 28), and vlp genes are orthologs of vlsE of B. burgdorferi (46). Only one of these proteins, either a Vsp or a Vlp, is expressed at any one time by a spirochete (5, 25, 30, 34, 37). The genes for these proteins are located on linear plasmids of 28 to 32 kb in the cell (25, 34, 37). There are also linear plasmids of 12, 53, and 180 kb, as well as multiple circular plasmids of 32 kb in B. hermsii (19, 25, 34, 44). Stevenson et al. did not find vsp or vlp sequences on the circular plasmids of B. hermsii (44).

Most of our studies of relapsing fever have focused on Vsp and Vlp antigenic variation in the mammalian host, but variation also occurs in other environments. Stoenner et al. used serotype-specific antisera to show that a novel serotype predominated in populations of B. hermsii subjected to serial passage in a broth medium (45). This “culture” serotype was not observed to arise in mice infected with B. hermsii (9, 11, 45), but it was possible that it might be favored in the tick, the other host for B. hermsii (9). Indeed, Schwan and Hinnebusch demonstrated that B. hermsii spirochetes with this phenotype predominated in the salivary glands of Ornithodoros hermsi ticks, the vector of B. hermsii, and also when the temperature for in vitro growth was lowered from 37 to 23°C (41).

A phenotype of B. hermsii HS1 that predominated during in vitro growth was first named serotype “C” (11, 45) and then renamed serotype “33” for consistency in terminology with other B. hermsii serotypes (16). This serotype was defined by Vsp33, the variable protein it expressed (4, 11, 45). Surprisingly, the promoter for the vsp33 gene was not like the promoter for other expressed vsp and vlp alleles in B. hermsii (5); it more closely resembled the promoter for ospC in B. burgdorferi (32). The differences between promoters for vsp33 and for other vsp and vlp genes showed that there was a second expression site for vsp genes in B. hermsii. This conclusion was consistent with the findings of Schwan and Hinnebusch (41). The rapid change in expression from mouse-associated serotype 7 to tick-associated serotype 33 suggested reciprocal changes in expression from the two different sites rather than a mutation or DNA rearrangement. For the present study, the first described promoter region or expression site for vlp7 and other vlp and vsp genes is called ES1 (5) and the promoter region or expression site for vsp33 is called ES2 (16).

On the other hand, the frequency of appearance of serotype 33 during in vitro cultivation was more consistent with a mutation rather than a manifestation of a change in gene regulation (45). Indeed, in one lineage of culture-derived serotype 33 there was a major DNA rearrangement in one of its linear plasmids (34). In serotype 33 populations isolated during in vitro cultivation vsp33 expression appears to be constitutive. They produce abundant Vsp33 at 37°C as well as at 23°C (11, 16; unpublished data).

For the present study, we examined two independent isolates of serotype 33 that were selected during in vitro cultivation. The constitutive expression of vsp33 in these two populations in culture distinguishes these cells from the isolate studied by Schwan and Hinnebusch in ticks and mice (41). In this respect, the isolates under study here are likely not typical of isolates in the natural environments for B. hermsii. Nevertheless, the culture-derived variants provide an opportunity to further study the relationship between the two expression sites for vsp genes. The apparently constant expression of Vsp33 also allowed us to assess the possible role of Vsp33 during mammalian infections. The specific questions we considered were the following. (i) Will populations of serotype 33 first isolated in the laboratory and stably expressing Vsp33 infect and proliferate in a mammalian host? (ii) Is the apparent silence of the other expression site for vsp genes in serotype 33 associated with a DNA rearrangement or other genetic change at that site? (iii) Is ES2 for vsp33 transcriptionally silent in other serotypes? (iv) Is expression of vsp33 in serotype 33 associated with a gene duplication, as is the case with genes at the other vsp expression site (14, 25)?

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and culture conditions.

The first isolate of serotype 33 of B. hermsii strain HS1 (ATCC 35209) was described previously (9, 16, 45). It emerged in a cell population of serotype 7 and for the present study was designated serotype 33(7). This lineage had been continually passed in culture for several years. A second lineage of serotype 33 appeared in a culture of serotype 21 of strain HS1 (9) and had undergone approximately 100 generations of growth in culture before the start of the study. This lineage was designated serotype 33(21). For the study, both cell types were cloned by limiting dilution in vitro (45). Serotypes 7, 21, and 26 of strain HS1 were obtained from infected mice and were cultivated once in medium before use in these experiments (35). The B. burgdorferi strain was B31 (ATCC 35210). Spirochetes were cultured at 34°C in Barbour-Stoenner-Kelly (BSK) II medium with 6% rabbit serum (2). Spirochetes in culture medium or mouse plasma were counted in a Petroff-Hauser chamber under phase-contrast microscopy. Culture harvests were prepared and frozen as concentrated cell suspensions at −80°C with 10% (vol/vol) dimethylsulfoxide as previously described (31). E. coli strains InvαF′ (Invitrogen Corp., San Diego, Calif.), XL-1 Blue MRF′ (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.), and EZ Sure (Stratagene) were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth medium. Serotypes were identified by indirect immunofluorescence, polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and Western blot analysis as previously described (11).

Antibodies and antisera.

The origins of serotype-specific monoclonal antibodies H4825 (serotype 33), H1826 (serotype 7), and 208 (serotype 21) have been given (10, 12). Monoclonal antibody H9724 to the FlaB protein of B. hermsii bound to all serotypes (8) and served as a positive control. Other serotypes were identified using a battery of fluorescein-conjugated, serotype-specific polyclonal murine antisera (45). A new monoclonal antibody specific for Vsp33 was produced by purifying Vsp33 from B. hermsii as previously described (13). BALB/c mice were then immunized three times at 2-week intervals with 10 μg of protein, and hybridomas were produced as previously described (10, 12). One of the monoclonal antibodies was determined to be an immunoglobulin G2b antibody by methods described previously (12), and it was designated H7995. By Western blot analysis, H7995 bound to Vsp33 but not to Vlp7, Vlp21, or Vsp26.

Mouse infections.

Six-week-old female BALB/c mice were irradiated with 900 rads from a 137Cs gamma radiation source and then inoculated intraperitoneally with spirochetes in 0.1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4. Blood was obtained from the tail vein during the course of the infection and then by lethal cardiac puncture while mice were under anesthesia (45). Thin blood smears were prepared, dried, fixed in methanol, and then examined by direct and indirect immunofluorescence assays as previously described (11, 45). Citrated blood was centrifuged for 2 s at 12,000 × g, and the plasma supernatant was obtained.

Nucleic acid methods.

Total DNA and total RNA were prepared from spirochetes as described previously (30). Plasmid-enriched DNA from B. hermsii was extracted using the Triton X-100 method described by Hinnebusch and Barbour (22). Plasmid DNA from Escherichia coli was extracted using a plasmid extraction kit (Qiagen Inc., Chatsworth, Calif.). Oligonucleotides for probes and primers were synthesized on an Applied Biosystems DNA synthesizer (Foster City, Calif.). Restriction enzymes from Boehringer Mannheim (Indianapolis, Ind.) were used as described in the manufacturer's recommendations. The PCR using primers for the ES1 promoter and for the telomere were used to obtain vsp or vlp genes at this site as described by Restrepo et al. (37). Restriction and PCR fragments were isolated from Pure Elute agarose (Invitrogen Corp., San Diego, Calif.) with an electroelutor (International Biotechnologies, Inc., New Haven, Conn.). Eluted DNA was ligated into pUC18 digested with PstI, SalI, or SmaI or into pBR322 digested with PstI. The ligation products were transformed into E. coli EZ Sure or XL-1 MRF′ Blue-Kan cells (Stratagene). The PCR products were ligated into the pCRII vector and transformed into E. coli INVαF′ cells (Invitrogen Corp.). Transformants were identified by hybridization with oligonucleotides. Sequences of both strands of the inserts were determined by the dideoxy chain termination method on double-stranded templates by using Sequenase (United States Biochemical, Cleveland, Ohio) or by an automated DNA sequencer (ABI) using custom primers.

Electrophoresis and Northern and Southern blot analyses.

One-dimensional agarose gel electrophoresis of restriction fragments was performed as previously described (30). Assessment of rapid reannealment of duplex restriction fragments after heat denaturation was carried out as described by Kitten and Barbour (25). Intact plasmids of B. hermsii were separated by constant field electrophoresis in 0.2% agarose at 0.7 V/cm (6), by field inversion electrophoresis (23), or in two-dimensional agarose gels with transverse alternating-field electrophoresis (TAFE; Beckman Instruments, Fullerton, Calif.) in the first dimension and high-voltage constant field electrophoresis (CFE) in the second dimension as previously described (18, 40). Assessment of rapid reannealment of plasmids after denaturation with alkali was performed as previously described (21). Southern and Northern blotting were performed essentially as described before (30, 39). For Southern blotting with one-dimensional electrophoresis gels, DNA was transferred to 0.45-μm-pore-size Nytran nylon membranes (Schleicher & Schuell). For Southern blottings by TAFE and with two-dimensional gels, DNA was transferred to 0.22-μm-pore-size uncharged nylon membranes. For Northern blotting, RNA was transferred to Immobilon-NC membranes (Millipore). Plasmid probes were labelled with [α-32P]ATP by nick translation (Bethesda Research Laboratories, Gaithersburg, Md.) or with a Random Prime kit (Boehringer Mannheim), and oligonucleotide probes were 5′ end-labeled with [α-32P]ATP with T4 polynucleotide kinase (Boehringer Mannheim) and purified in Nensorb-20 columns (DuPont NEN, Boston, Mass.). Hybridizations were conducted in 6× SSC and washes were conducted in 0.1× SSC–0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–1 mM EDTA for labeled plasmids and 6× SSC–0.1% SDS for labeled oligonucleotides (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate).

DNA sequence accession numbers.

Previously published gene sequences used in this study were the following: vlp21, vlp32, and vlp34 (GenBank accession no. L33914); vlp7 (X53926); ES1, vsp26, and the downstream homology sequence (DHS) block (Z11876); vlp25 (L04787); vsp2 (L33897); and vsp33 (L24911).

DNA probes.

The probes for vsp33 were the following: 33-P, a PCR product using the forward primer 5′-GCAAATATAAAAAATGCGGTT-3′ (nucleotides [nt] 265 to 285 of accession no. L24911) and the reverse primer 5′-TGTTAACAATTCATCAATTGC-3′ (nt 531 to 549), and 33-O, the oligonucleotide 5′-TCTACTTCTTGAACACTTGCAGC-3′ (nt 314 to 292). The probes for ES1 were the following: ES-O, the oligonucleotide 5′-GGTGATAAATTTGATTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT-3′ (nt 6777 to 6806 of accession no. Z11876), and two recombinant plasmids with inserts in pBR322, pE21, which contained a 0.8-kb HindIII fragment with the promoter at ES1 (nt 6391 to 7156 of accession no. Z11876) (5), and p7.41, which contained the 1.4-kb HindIII fragment immediately upstream of the pE21 fragment (nt 4934 to 6391 of accession no. Z11876) (25). The probe for circular plasmids (CP) was purified cp32 circular plasmids of B. burgdorferi B31 as previously described (22); B. hermsii has a similar sequence (GenBank accession no. AF123078). The probe for all known B. hermsii vsp and vlp genes other than vsp33 was oligonucleotide V-O (5′-GCACTTATTCTTTTTCTCAT-3′); this oligonucleotide bound to the antisense strand with the first 20 nt of the vsp and vlp genes from the start codon (nt 6874 to 6893 of accession no. Z11876). Probe 7-P for vlp7 was a PCR product of the forward primer 5′-GTAAATGGAAATTTAGGCAATTCACT-3′ (nt 191 to 216 of accession no. X53926) and reverse primer 5′-GCTAGCTGCGCATCATTCTCTC-3′ (nt 840 to 819). Probe 21-O for vlp21 was the oligonucleotide 5′-CAGGTAAGACCGGAGCA-3′ (nt 4800 to 4816 of accession no. L33914). Probes 25-O1 and 25-O2 for vlp25 were the oligonucleotides 5′-TACTGCGGTTACTCCTGCTGATT-3′ (nt 975 to 953 of accession no. L04787) and 5′-AAGCAGGGAAGGATGGC-3′ (nt 98 to 114 of accession no. L04787), respectively. Probe 2-O for vsp2 was the oligonucleotide 5′-CAAGAACACCTGTATCTTTCG-3′ (nt 259 to 239 of L33897).

Reporter plasmid constructs.

The plasmids pGOΔ1 and pGOΔ7 and the procedures for producing them have been described previously (42, 43). pGOΔ1 contains the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) gene but not an added promoter; it has a low level of CAT production and chloramphenicol resistance from a cryptic promoter in the plasmid (43). Plasmid pGOΔ7 has the promoter region for vlp7 fused to the cat gene (43). For this study, the promoter regions for vsp33 were amplified from serotype 33 and serotype 7 cells by using PCR and the forward primer 5′-ATTTGTATAGATATTGATAA-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-CTTATTAACATACATTAA-3′. The 126-nt product spanned from positions −109 to +7, where position +1 was the transcriptional start site for vsp33 (16). The promoter region for the vsp2 gene at ES1 in serotype 33 (7) was amplified using the forward primer 5′-CTAAAGGTTCTGAATGC-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-CTTATGCATTAGCATTATACC-3′, which spanned positions −182 to +8, where +1 is the transcriptional start site (5). The products were first cloned into the TA cloning vector (Invitrogen) and then inserted into the EcoRI site of pGOΔ1 as previously described (43). The plasmids containing the putative promoter regions for vsp33 and vsp2 fused to the cat gene were named pGOΔ33 and pGOΔ2, respectively. The E. coli host cells were XL-1 Blue MRF′.

Assays of CAT activity.

The MICs of chloramphenicol for E. coli in LB broth were determined as previously described (43). In vitro CAT activities of cell lysates were assessed using the fluor diffusion assay with [3H]acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) (Dupont NEN) as the acetyl donor as previously described (42).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequences of ES1 from the start of the extended promoter (43) to past the vsp gene for serotype 33(7) and to the subtelomeric region (37) for serotype 33(21) have been assigned GenBank accession no. AF236048 and AF 236049, respectively.

RESULTS

Serotype 33 infects mice but does not persist.

Previous studies demonstrated the presence of serotype 33 cells in clonally derived populations of serotypes 7, 14, and 21 growing in vitro (9, 11, 45). As these cultures were serially passed, the prevalence of serotype 33 increased, and when they were cloned by limiting dilution, clonal populations of serotype 33 were obtained. For this study, we examined two independent switches to serotype 33. The first, serotype 33(7), was from serotype 7 and had been serially passed in the laboratory. The second population, serotype 33(21), was derived from serotype 21 and had undergone comparatively fewer generations of in vitro growth. Serotype 33(21) produced a Vsp the same size as the Vsp of previously characterized serotype 33(7). Both proteins were bound by Vsp33-specific monoclonal antibodies H4825 and H7995 by Western blot analysis.

In the initial description of serotype 33, Stoenner et al., using polyclonal antiserum to the serotype, reported its transient presence in the blood of mice inoculated with broth cultures of other serotypes (45). In a preliminary experiment for the present study, we confirmed the identity of these spirochetes in the blood from the Stoenner et al. study as serotype 33 by using monoclonal antibody H4825 (data not shown). To further define the ability of culture-derived serotype 33 to infect mice and the outcome of the infection, clonal populations of serotypes 33(7) and 33(21) at doses of 107 cells were inoculated intraperitoneally into groups of 10 mice on day zero in two separate experiments. The mice had been irradiated to prevent a specific antibody response against the infecting population (45). The course of the infection was followed by microscopic examination of the blood, and as mice were sacrificed, the blood was collected for immunofluorescence assays and for culture. For the first experiment, the positive control was infection with serotype 26 and blood was examined on days 3, 5, and 8. For the second experiment, the positive control was serotype 7 and blood was examined on days 2, 3, 4, and 12.

The results of the two experiments are shown in Table 1. In both experiments, serotype 33(7) did not produce an early spirochetemia in the mice. However, after 5 to 12 days of observation, spirochetes of other serotypes appeared in the blood in 2 of 10 mice in the first experiment and 3 of 6 mice in the second experiment. These isolates were typed as serotype 7 and serotype 2 in the respective experiments. In contrast to the more highly passaged 33(7) serotype, spirochetes of the 33(21) lineage appeared in the blood of irradiated mice within 2 to 3 days of injection. The cells in the blood were expressing Vsp33 by the criterion of antibody reactivity but occurred at a 10-fold-lower concentration than either serotype 26 or 7. The subsequent disappearance of 33(21) cells from the blood by days 4 to 5 was unlikely the effect of an immune response; mice infected with serotypes 26 or 7 remained spirochetemic throughout this period. Spirochetes that appeared again in the blood of mice infected with 33(21) were other serotypes, namely 1, 21, or 24, when typeable with antibody. Thus, both isolates of serotype 33 were infectious for mice but were less virulent, in terms of spirochete burden and persistence in the blood, than isolates of other serotypes. Serotype 33 populations, even one with a long history of passage in culture, retained the capability of switching to other serotypes.

TABLE 1.

Infections of irradiated mice with two culture-derived isolates serotype 33 of B. hermsii strain HS1

| Expt no. | Serotype | No. of mice infected/no. of mice examined on day of infection (no. of spirochetes/ml of blood in infected mice)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 8 | 12 | ||

| 1 | 33 (7) | 0/10 | 2/2 (105) | 2/10 (105) | |||

| 33 (21) | 10/10 (106) | 0/4 | 4/10 (106) | ||||

| 26 | 10/10 (107) | 3/3 (107) | NDa | ||||

| 2 | 33 (7) | 0/10 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 3/6 (106) | ||

| 33 (21) | 10/10 (105) | 2/4 (105) | 0/4 | 1/3 (106) | |||

| 7 | 10/10 (106) | 4/4 (107) | 3/3 (107) | ND | |||

ND, not done.

The single-copy vsp33 gene is on a 53-kb linear plasmid.

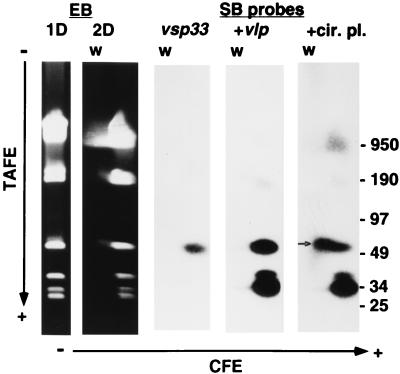

We next determined the genomic location for vsp33, the gene for Vsp33, using two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and Southern blotting. Figure 1 shows the findings for serotype 33(7). The first dimension was a pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Ethidium bromide staining shows the megabase-size chromosome and the large linear plasmid of approximately 180 kb of B. hermsii (19). There are also at least four other plasmids in the range of 25 to 53 kb (19). In the second dimension, with CFE, the linear plasmids and chromosome migrated at approximately the same rate (18). Visible just above a 53-kb linear plasmid is a band that migrated more slowly than the linear replicons in the second dimension; this band is indicated by an arrow.

FIG. 1.

One-dimensional (1D) and two-dimensional (2D) gels with ethidium bromide (EB) staining and Southern blot (SB) analysis of a two-dimensional gel of total DNA of serotype 33 of B. hermsii strain HS1. The blot was sequentially hybridized first with probe 33-P for vsp33, then with probe 7-P for vlp7 (+vlp), and finally with probe CP for the circular plasmid (+cir. pl.). For the two-dimensional gel in 1.0% agarose, electrophoresis was first transverse alternating field (TAFE) and then constant field (CFE). The long arrows show the direction of migration from cathode (−) to anode (+). The migrations of linear molecular size standards (in kilobases) in the TAFE dimension are shown on the right. The small arrow indicates the position of the circular plasmid behind the 53-kb linear plasmid by CFE. The conditions for TAFE at 181 mA in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer were a 4-s pulse for 30 min, 1-s pulse for 9 h, and 5-s pulse for 9 h.

The Southern blot of the two-dimensional gel was sequentially hybridized with probes for vsp33, vlp7, and a circular plasmid (Fig. 1). The accumulation of bands with successive probes over the three Southern blots is shown. The left blot shows the hybridization of the vsp33-specific probe to the 53-kb linear plasmid. In the center blot, the vlp probe hybridized strongly to linear plasmids of approximately 28 and 40 kb and weakly to the 180-kb plasmid. In a separate experiment, there was no detectable hybridization of the vlp probe to the 53-kb linear plasmid (data not shown). In the right blot, the circular plasmid probe hybridized to the plasmid that migrated more slowly in the second dimension, thus confirming its identity as a circular plasmid. When serotype 33(21) and serotype 7 DNA was used in another blot, the vsp33 probe hybridized only to the 53-kb linear plasmid (data not shown), an indication that a major rearrangement of that plasmid had not occurred in the switch to serotype 33 from serotype 7.

In other serotypes of B. hermsii HS1 there are two copies of the expressed vsp or vlp gene: one at its archival location and one at ES1, located at the end of a linear plasmid of about 28 to 30 kb (25). Usually the archived vsp or vlp gene is on a different plasmid of between 26 and 32 kb. In contrast, the vsp33 gene was found only on a single plasmid, one not previously known to bear vsp or vlp genes. To investigate whether there had been a duplication or some other major rearrangement of the vsp33 gene, the vsp33-specific probe was hybridized with blots of digested DNA from serotypes 33(7), 33(21), and 21. The results with the HindIII digest are shown in Fig. 2. Only a 2.4-kb fragment hybridized with the probe even in DNA from cells expressing Vsp33. Single hybridizing fragments were also seen in Southern blots after digestion with AluI, DraI, EcoRV, HincII, NdeI, NsiI, PstI, RsaI, Sau3A, ScaI, or SpeI (data not shown). Thus, the activation of vsp33's expression site was not the consequence of a major DNA rearrangement of the site. If the digested DNA was first denatured by boiling before the electrophoresis, the hybridizing bands in the blots were smaller than the bands observed with undenatured DNA (data not shown). This was an indication that the restriction fragments did not rapidly reanneal and, thus, were unlikely to be telomeric (25, 37).

FIG. 2.

Southern blot analysis of HindIII-digested total DNA from serotypes 33(7), 33(21), and 21 of B. hermsii that was probed with probe 33-P for vsp33. The agarose concentration was 0.7%, and the locations of the migrations of molecular size markers (in kilobases) are shown on the left.

Serotype 33 but not other serotypes may have expressed Vsp33 under these in vitro conditions because of a change in the promoter for vsp33. To investigate this possibility, the promoter region for vsp33 in serotype 7 cells was cloned and sequenced. The sequence, which included the ribosomal binding sequence, the transcriptional start site, the −10 and −35 elements, and 50 nt further upstream, was identical to the vsp33 promoter in serotype 33(7) (16).

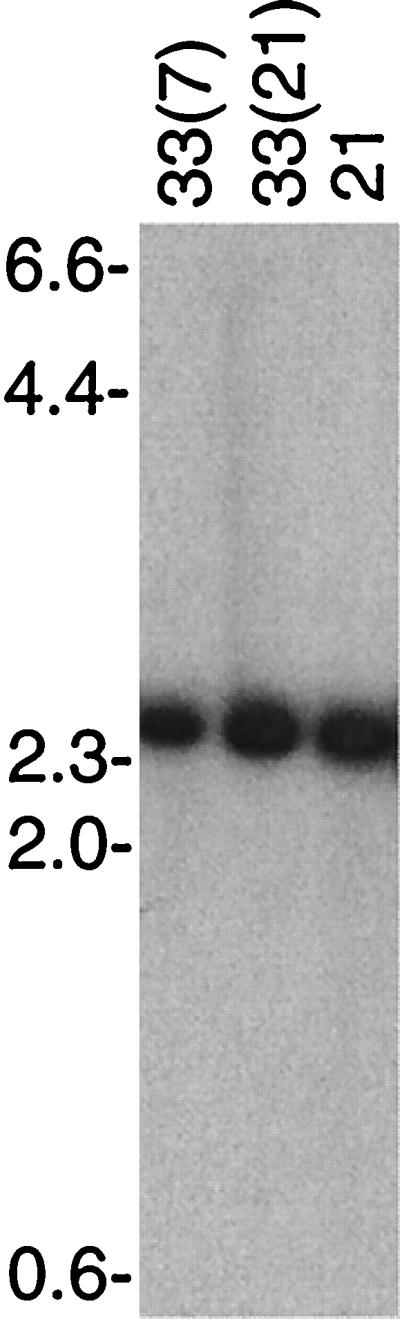

Differences in Vsp expression are determined at the level of transcription.

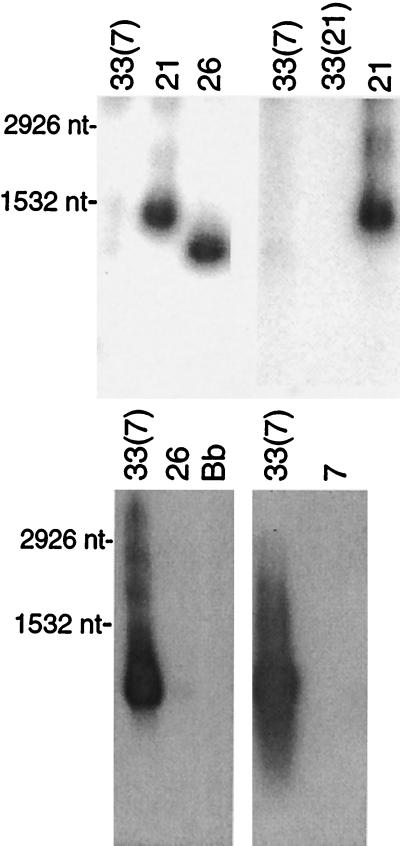

Different Northern blots of RNA from serotypes 33(7), 33(21), 7, 21, and/or B. burgdorferi were probed with labeled oligonucleotides that were specific for either vsp33 or for the conserved 5′ end of vsp and vlp genes at ES1. The results are shown in Fig. 3. The vsp33-specific probe hybridized strongly only to a band in 33(7) with approximately 600 to 700 nt. There was no detectable hybridization of RNA from serotypes 26 or 7 of B. hermsii or from B. burgdorferi as a negative control. When the same RNA and, in addition, RNA from the 33(21) lineage were probed with the oligonucleotide specific for the 5′ end of genes at the first expression site (16), transcription was detected in serotypes 21 and 26 but not in either 33(7) or 33(21). The sizes of the hybridizing bands were consistent with previous results and the known sizes of Vsp26 and Vlp21 (30, 36).

FIG. 3.

The vsp33 gene is transcribed in serotype 33 but not in other serotypes. Northern blot analyses of RNA of serotypes 33(7) and 33(21) of B. hermsii and of B. burgdorferi (Bb) with probes specific for vsp33 (above) or with an oligonucleotide (V-O) that binds to the 5′ end of all other known vsp and vlp genes (below) were carried out. Formaldehyde-denatured total RNA was separated by electrophoresis in 1.5% agarose. (Above) Two separate experiments are shown: 33(7), 21, and 26 on the left and 33(7), 33(21), and 21 on the right. (Below) Two separate experiments are shown: 33(7), 26, and B. burgdorferi (Bb) on the left and 33(7) and 7 on the right. The probe for the left lower blot was 33-O, and the probe for the right lower blot was 33-P. The sizes of 23S (2,926 nucleotides [nt]) and 16S (1,532 nt) of rRNAs of Borrelia are indicated to the left (39).

ES1 is no longer telomeric in serotype 33(7).

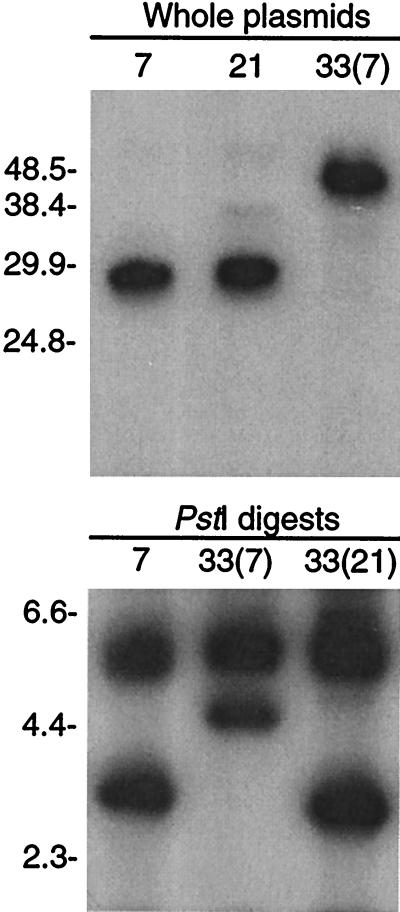

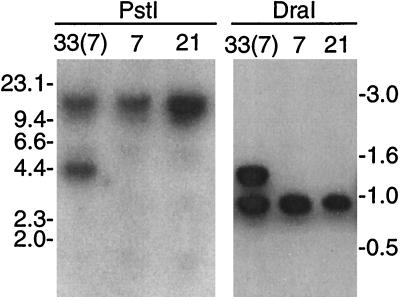

If there was no alteration of the vsp33 expression site on the 53-kb plasmid, constitutive expression of vsp33 by serotype 33 could have been the result of change in a trans-acting factor, such as mutation in a repressor gene. (Experiments with E. coli that addressed this possibility are described below.) But how could the lack of expression from the other vsp expression site be explained? An earlier study indicated that there was a DNA rearrangement at this locus (34). To confirm this, probes for the first expression site were used in Southern blottings of intact plasmids and of restriction enzyme digests (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Southern blot analysis of intact plasmids of serotypes 7, 21, and 33(7) (above) and PstI digests of DNA from serotypes 7, 33(7), and 33(21) (below) with ES1 probes. For the upper blot, the field inversion electrophoresis gel had 1.0% agarose and the p7.41 probe was used. For the lower blot, the constant field electrophoresis gel had 0.7% agarose and the pE21 probe, which includes a PstI site, was used. The migrations of molecular size standards (in kilobases) are shown on the left.

When undigested plasmids were separated by field inversion electrophoresis and then subjected to Southern blot analysis with a probe for ES1, we confirmed that this locus in serotype 33(7) was located on a 40-kb plasmid instead of a 28-kb plasmid (Fig. 4). This plasmid had behaved like a duplex linear molecule with covalently closed ends in two-dimensional gels and after denaturation (18, 19). Serotype 33(7) still had at least one linear plasmid of 28 to 30 kb (25, 34), but plasmids with these sizes did not have this expression site. Serotypes 7 and 21 had the expected 28-kb plasmids with the first expression site. In a separate experiment, plasmid DNA from 33(21) cells was indistinguishable from plasmid DNA from serotype 21 cells in pulsed-field gels; there was not a 40-kb plasmid in serotype 33(21) (data not shown).

A PstI digest of DNA from serotypes 7, 33(7), and 33(21) was probed with a fragment that included ES1 as well as a sequence further upstream (Fig. 4). This probe contained an internal PstI site and thus would be expected to hybridize on the blot to two fragments, one of which would represent the invariable upstream sequence at ES1 and the other would contain part of the variable genes themselves (25). The probe hybridized to 5.0-kb PstI fragments in each of the three DNA samples. This was the invariable upstream region described previously (25). The other hybridizing fragment differed in size between serotypes. In serotype 7 DNA, the second fragment was 2.8 kb in size, as expected (30). In 33(7) DNA, the second hybridizing fragment was 4.4 kb. In contrast, 33(21) cells had a hybridizing PstI fragment of 2.9 kb, the expected size of the fragment for serotype 21, the precursor to 33(21) (30).

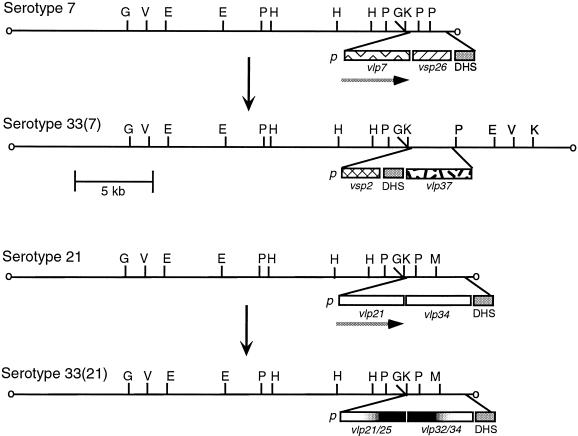

The 4.4-kb PstI fragment of serotype 33(7) was cloned and completely sequenced. Additional physical mapping of the unique 40-kb linear plasmid of serotype 33(7) was carried out, and the results were compared with the maps for the ES1-bearing plasmids in serotypes 7 and 21 (25, 34, 35, 37). For these mapping studies we used probes ES-O, pE21, and p7.41 for the ES1 site, probe 7-P for vlp7, probe 21-O for vlp2, probes 25-O1 and 25-O2 for vlp25, and probe 2-O for vsp2. Figure 5 summarizes the findings.

FIG. 5.

Partial physical maps of expression site plasmids before and after an in vitro switch to serotype 33 from serotype 7 (above) or from serotype 21 (below). For each switch, the changes in restriction maps for the linear plasmid bearing the telomeric expression site for either vlp7 or vlp21 in serotypes 7 or 21, respectively, are shown. The regions containing the putative promoter (p), the vsp or vlp genes, and the repetitive DHS sequence (25) are expanded below each plasmid. The different sequences are indicated by different patterns, such as the cross-hatched pattern for vsp26. The exception is the representation of vlp21 and vlp34 with the same pattern in the lower panel even though they have different sequences. For serotype 33(21), the chimeric vlp genes are indicated by the white-black gradients. Genes that were expressed, vlp7 in serotype 7 and vlp21 in serotype 21, are indicated by the horizontal arrow beneath. The restriction enzymes were BglII (G), EcoRV (V), EcoRI (E), PstI (P), HindIII, KpnI (K), and MspI (M). The restriction maps were determined using plasmid and oligonucleotide probes specific for the ES1 promoter and its 5′ flanking region, as well as oligonucleotide probes specific for vsp2, vlp7, vlp21, and vlp25.

The plasmid bearing ES1 in 33(7) cells differs from that in serotype 7 by the replacement of the expressed vlp7 by vsp2 next to the promoter. The promoter for vsp2 was identical to the promoter for expressed vsp2 in serotype 2 (37). In serotype 7, the repetitive DHS sequence follows vsp26 (25); in 33(7), the DHS block is between vsp2 and a vlp37 gene downstream. Moreover, in 33(7) there are approximately 12 kb between the expression site promoter and the right telomere. In other serotypes, this region is about 1 to 2 kb (37). The addition of these 12 kb to the 28-kb linear plasmid of serotypes 7 and 21 would account for the 40-kb ES1-bearing plasmid in 33(7).

To determine if this rearrangement in serotype 33(7) was the result of a duplication, an oligonucleotide specific for vsp2 was used to probe digests of total DNA from serotypes 33(7), 7, and 21 (Fig. 6). In both the PstI and DraI digests there was an additional band in 33(7) that was hybridized by the probe. The fragments common to the three serotypes contain the archived versions of the sequences. The 4.4-kb PstI fragment unique to 33(7) is the fragment containing ES1 and is identified in Fig. 4.

FIG. 6.

Southern blot analysis of PstI- or DraI-digested total DNA of serotypes 33(7), 7, and 21 that was hybridized with probe 2-O for vsp2. The agarose concentrations were 0.7% for PstI digests and 1.0% for DraI digests. The migrations of molecular size standards (in kilobases) are shown.

In contrast to serotype 33(7)'s different plasmid profile, serotype 33(21)'s plasmid profile by field inversion gel electrophoresis was identical to that of its precursor, serotype 21 (data not shown). The 2.8-kb PstI fragment containing the ES1 promoter (Fig. 4) was cloned and sequenced. The sequence of 3.7 kb of DNA that extended downstream from the second PstI site to the telomere of the plasmid in serotype 33(21) was obtained from a PCR fragment produced with a forward primer for the ES1 promoter and a reverse primer for the conserved telomere (37) (Fig. 5). The ES1 promoter, as well as the 1.5 kb of sequence upstream of the promoter, was identical to that in serotype 21 of strain HS1 (5, 14).

Although the ES1-bearing PstI fragment of 33(21) was the same size as in its precursor, serotype 21 (Fig. 4), there were differences between serotypes 21 and 33(21) in the vlp sequences at this site. In 33(21) the vlp gene adjacent to the ES1 promoter was an in-frame chimera of vlp21 at its 5′ end and vlp25 at its 3′ end (Fig. 5). Downstream of the silent vlp21/25 gene was vlp32/34, a chimera of vlp32 and vlp34 (35).

The ES1 promoter but not the ES2 promoter is functional in E. coli.

The constitutive expression of Vsp33 in the two isolates of serotype 33 was further investigated by cloning and sequencing the promoter region for vsp33 from serotype 7 cells. These cells produce Vlp7 but not Vsp33 at 34°C (11). A difference in the promoter region or in the untranslated portion of the vsp33 gene could account for this finding. However, there were no differences between the promoter region or 5′ gene sequences for vsp33 in serotype 33(7) and serotype 7 (data not shown).

These findings, along with the report of environmental effects on vsp and vlp expression (41), suggested that a repressor, a cis-acting element (43), and/or a transcriptional activator were determinants of expression of this site. This possibility was investigated by placing the promoter regions for vsp33 upstream of a gene for CAT from Staphylococcus aureus to yield pGOΔ33. We also placed cat downstream of the promoter region for vsp2 in serotype 33(7) to create the reporter construct pGOΔ2. These were compared with plasmid pGOΔ1, the control construct (42), and the promoter region for vlp7 fused to the cat gene (43). Plasmids pGOΔ7 and pGOΔ2 contained the ES1 sequences that were functional in serotypes 7 and 2, respectively, and plasmid pGOΔ33 represented ES2.

Using conditions and procedures that were used for transfection of B. burgdorferi (43), we were not successful in transfecting the plasmid constructs into B. hermsii, and obtaining detectable expression with any promoter construct have not been successful (unpublished findings). Therefore, E. coli cells transformed with one of the four constructs were compared in their susceptibility to chloramphenicol and their CAT activities in an in vitro assay with a radiolabel substrate for CAT. The results are shown in Table 2. The promoters for the vlp7 and vsp2 genes at the first expression site were indistinguishable by both assays. They provided high levels of resistance to chloramphenicol and acetylated the antibiotic at a rate comparable to that of the ospA promoter of B. burgdorferi (42). There was no apparent effect on CAT expression in E. coli with one fewer T in the extended promoter for vsp2 in serotype 33 (43). In contrast, the vsp33 promoter region, which was identical in serotype 33 and serotype 7 DNA, was scarcely different in activity from the negative control pGOΔ1 by either the MIC assay or in vitro acetylation assay. The MICs of chloramphenicol for the E. coli with the different plasmids were the same with cultivation at 23°C as they were at 37°C.

TABLE 2.

Chloramphenicol resistance and CAT activity of promoter-reporter plasmids in E. coli

| Reporter plasmid | Promoter | MIC (μg/ml)a | CAT activity (cpm ± 95% CI)b | Relative activityc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pGOΔ1 | None | 10 | 54 ± 6 | 0 |

| pGOΔ33 | vsp33 | 20 | 387 ± 26 | 8 |

| pGOΔ7 | vlp7 | 640 | 3,992 ± 224 | 100 |

| pGOΔ2 | vsp2 | 640 | 4,146 ± 566 | 104 |

MIC of chloramphenicol at 23 and 37°C.

Mean counts per minute ± 95% confidence interval.

CAT activity was adjusted by subtracting the mean value for pGOΔ1; this result was then divided by the adjusted mean activity for pGOΔ7 to produce relative activity.

DISCUSSION

Stoenner's modification of Kelly's broth medium allowed growth from single cells of B. hermsii (45). Thus, the gradual succession of a new serotype in serially diluted broth cultures of infected mouse blood could only have been the result of the selection for the variant as it arose in the clonal population. The rate for the switch to serotype 33 in culture is of the same order as those for the switches among other serotypes in mice (9, 45). Serotype 33 had a known growth advantage over other serotypes during broth cultivation, but until the study of Schwan and Hinnebusch the role for Vsp33 in its natural environment was not known (41). Although the conditions that selected for serotype 33 during laboratory cultivation included mammalian serum and growth temperatures of 34 to 37°C, Schwan and Hinnebusch noted that Vsp33 expression increased in the tick and when the temperature was lowered from 37 to 23°C in vitro (41). The rapid change in expression with a change in the environment was consistent with differential gene regulation rather than a hereditary change.

The reciprocal relationship between expression of vsp33 and vlp7 and the differences between the ES1 promoter for vlp7 and the ES2 promoter for vsp33 indicated that there was a second expression site for the variable genes in B. hermsii. The present study demonstrated the following. (i) ES2 was on a 53-kb linear plasmid, while ES1 was on a 28-kb linear plasmid. (ii) When ES1 was transcriptionally active, ES2 was not, and vice versa. The mechanisms for the activation of ES2 and silencing of ES1 in serotypes 33(7) and 33(21) are not known. In both 33(7) and 33(21) the ES1 promoter region was identical to the ES1 promoters for vlp and other vsp genes in other serotypes (1, 37, 43). Both serotype 33 lineages had an intact, full-length vsp or vlp gene downstream from the ES1 promoter in their expected locations. ES1 in serotype 33(7) was not telomeric, but ES1 in serotype 33(21) was. The chimeric vlp genes found at ES1 in serotype 33(21) was possibly the result of a recombination between the locus with the tandem of vlp21 and vlp32 and the locus with vlp25 and vlp34 (35). However, this recombination between silent loci was not sufficient for explaining ES1's silence in serotype 33(21). A chimeric vlp gene made up of parts of the vlp7 and vlp21 genes was expressed in B. hermsii (26).

The expression of Vsp33 in serotypes 33(7) and 33(21) was not the result of a duplication of vsp33 or a change in the ES2 promoter itself. Unless there was an undetected change in a cis-acting enhancer element at ES2, the probable explanation for vsp33 transcription in serotype 33 but not in serotype 7 is a change in a trans-acting factor, such as the DNA-binding protein demonstrated in B. burgdorferi (24). The poor activity of the ES2 promoter in E. coli, as demonstrated in this study, and the poor activity of the homologous ospC promoter in both E. coli and B. burgdorferi, as demonstrated by Sohaskey et al. (42, 43), indirectly indicates the role of a trans-acting factor in promoting transcription from vsp33- and ospC-type promoters. A similar phenomenon of constitutive expression of ospC occurred in a mutant of B. burgdorferi that had lost a 17-kb linear plasmid (38). One model to account for these findings is the derepression of a gene for activators of the vsp33 or ospC promoter in the serotype 33 isolates of this study or in the mutant of B. burgdorferi.

The greater strength of the ES1 promoter in comparison to the vsp33 or the ospC promoter in E. coli is understandable. The ES1 promoter for vlp7 in serotype 7 and vsp2 in serotype 33 is very close to the consensus ς70-type prokaryotic promoter. B. burgdorferi has ς70-type sigma factor (20), and this is likely the case for B. hermsii. The putative −10 elements in the promoter regions for vsp33 and ospC have a TA for the first and second positions but not a T at the sixth. Moreover, right in front of the −10 element is a near-consensus −35 element sequence in both genes. This may result in misalignment of the RNA polymerase holoenzyme in the absence of an activator.

While Vsp33 expression is favored in the tick salivary gland and during laboratory cultivation (41, 45), it appears to be disadvantageous for B. hermsii in mammalian blood. Schwan and Hinnebusch found that serotype 33 cells in salivary glands of ticks were infectious, but by the time the spirochetes were detectable in the blood they were expressing another Vlp or Vsp (41). In the present study, the bacteremias with serotype 33 cells were transient in immunodeficient animals, though this may also have been the consequence of other mutations or the loss of plasmids during in vitro cultivation. In the experiment with the highly passaged serotype 33(7), the cells that eventually appeared and proliferated in the blood were of serotypes other than 33. However, a ES2-type promoter located internally on a plasmid may still be active during mammalian infections. Serotypes A and B express vspA and vspB, respectively, in mice from an internal expression site that is highly similar to that of ES2 of B. hermsii (15, 32).

We located the vsp33 gene to a linear plasmid of approximately 53 kb in B. hermsii. Previous studies have shown hybridization of ospC or vsp probes to a linear plasmid of about this size, but these probes were not specific for vsp33 and bound to plasmids of 28 to 32 kb as well to the larger plasmid (27, 28). The 53-kb plasmid also contains guaA and guaB genes in B. hermsii (29). Thus, this plasmid had paralogs of genes that previously had been found only on a 26-kb circular plasmid in B. burgdorferi. In Borrelia turicatae, a plasmid of 53 kb contained a vsp gene with a promoter similar to ES2 as well as a paralog of a gene found on the 26-kb circular plasmids (33). Taken together, these findings suggest that the 53-kb plasmid arose through a duplication or recombination involving a 26-kb circular plasmid. Conversion of the circular plasmid to a linear replicon has been observed in B. hermsii (19).

The present study further characterized differences between serotype 33 and other known serotypes of B. hermsii. Although the switch to serotype 33 cannot be described as antigenic variation in the strictest sense of the definition, it is a major change in the major outer membrane protein of the cells and occurs when environmental conditions alter. This change in surface protein phenotype came about not from a switch in genes at an expression site but through a switch in the activity of two promoters. Thus, the relapsing fever agent B. hermsii exhibits each of the four major mechanisms for altering its surface proteins.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant AI24424 and by the intramural division of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases while A.G.B. was a staff scientist in the Institute.

We thank Mehdi Ferdows, Cynthia Freitag, Joe Hinnebusch, Todd Kitten, Blanca Restrepo, and Merry Schrumpf for their early contributions to this study, Herb Stoenner for providing the battery of polyclonal antisera for typing, Sven Bergström for helpful discussions, and Tom Schwan for both advice and critical review of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barbour A G. Antigenic variation of a relapsing fever Borrelia species. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1990;44:155–171. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.44.100190.001103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barbour A G. Isolation and cultivation of Lyme disease spirochetes. Yale J Biol Med. 1984;57:521–525. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barbour A G. Linear DNA of Borrelia species and antigenic variation. Trends Microbiol. 1993;1:236–239. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(93)90139-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barbour A G, Barrera O, Judd R C. Structural analysis of the variable major proteins of Borrelia hermsii. J Exp Med. 1983;158:2127–2140. doi: 10.1084/jem.158.6.2127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barbour A G, Burman N, Carter C J, Kitten T, Bergstrom S. Variable antigen genes of the relapsing fever agent Borrelia hermsii are activated by promoter addition. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:489–493. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb02132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barbour A G, Garon C F. Linear plasmids of the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi have covalently closed ends. Science. 1987;237:409–411. doi: 10.1126/science.3603026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barbour A G, Hayes S F. Biology of Borrelia species. Microbiol Rev. 1986;50:381–400. doi: 10.1128/mr.50.4.381-400.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barbour A G, Hayes S F, Heiland R A, Schrumpf M E, Tessier S L. A Borrelia-specific monoclonal antibody binds to a flagellar epitope. Infect Immun. 1986;52:549–554. doi: 10.1128/iai.52.2.549-554.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barbour A G, Stoenner H. Antigenic variation of Borrelia hermsii. In: Herskowitz I, Simon M I, editors. Genome rearrangement. New York, N.Y: Alan R. Liss, Inc.; 1985. pp. 123–135. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barbour A G, Tessier S L, Hayes S F. Variation in a major surface protein of Lyme disease spirochetes. Infect Immun. 1984;45:94–100. doi: 10.1128/iai.45.1.94-100.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barbour A G, Tessier S L, Stoenner H G. Variable major proteins of Borrelia hermsii. J Exp Med. 1982;156:1312–1324. doi: 10.1084/jem.156.5.1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barbour A G, Todd W J, Stoenner H G. Action of penicillin on Borrelia hermsii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1982;21:823–829. doi: 10.1128/aac.21.5.823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barstad P A, Coligan J E, Raum M G, Barbour A G. Variable major proteins of Borrelia hermsii. Epitope mapping and partial sequence analysis of CNBr peptides. J Exp Med. 1985;161:1302–1314. doi: 10.1084/jem.161.6.1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burman N, Bergstrom S, Restrepo B I, Barbour A G. The variable antigens Vmp7 and Vmp21 of the relapsing fever bacterium Borrelia hermsii are structurally analogous to the VSG proteins of the African trypanosome. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:1715–1726. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cadavid D, Pennington P M, Kerentseva T A, Bergstrom S, Barbour A G. Immunologic and genetic analyses of VmpA of a neurotropic strain of Borrelia turicatae. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3352–3360. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.8.3352-3360.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carter C J, Bergstrom S, Norris S J, Barbour A G. A family of surface-exposed proteins of 20 kilodaltons in the genus Borrelia. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2792–2799. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.7.2792-2799.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deitsch K W, Moxon E R, Wellems T E. Shared themes of antigenic variation and virulence in bacterial, protozoal, and fungal infections. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:281–293. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.3.281-293.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferdows M S, Barbour A G. Megabase-sized linear DNA in the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi, the Lyme disease agent. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:5969–5973. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.15.5969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferdows M S, Serwer P, Griess G A, Norris S J, Barbour A G. Conversion of a linear to a circular plasmid in the relapsing fever agent Borrelia hermsii. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:793–800. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.3.793-800.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fraser C M, Casjens S, Huang W M, Sutton G G, Clayton R, Lathigra R, White O, Ketchum K A, Dodson R, Hickey E K, Gwinn M, Dougherty B, Tomb J F, Fleischmann R D, Richardson D, Peterson J, Kerlavage A R, Quackenbush J, Salzberg S, Hanson M, van Vugt R, Palmer N, Adams M D, Gocayne J, Venter J C, et al. Genomic sequence of a Lyme disease spirochaete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Nature. 1997;390:580–586. doi: 10.1038/37551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hinnebusch J, Barbour A G. Linear plasmids of Borrelia burgdorferi have a telomeric structure and sequence similar to those of a eukaryotic virus. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:7233–7239. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.22.7233-7239.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hinnebusch J, Barbour A G. Linear- and circular-plasmid copy numbers in Borrelia burgdorferi. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5251–5257. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.16.5251-5257.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hinnebusch J, Bergstrom S, Barbour A G. Cloning and sequence analysis of linear plasmid telomeres of the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:811–820. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Indest K J, Philipp M T. DNA-binding proteins possibly involved in regulation of the post-logarithmic-phase expression of lipoprotein P35 in Borrelia burgdorferi. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:522–525. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.2.522-525.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kitten T, Barbour A G. Juxtaposition of expressed variable antigen genes with a conserved telomere in the bacterium Borrelia hermsii. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:6077–6081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.16.6077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kitten T, Barrera A V, Barbour A G. Intragenic recombination and a chimeric outer membrane protein in the relapsing fever agent Borrelia hermsii. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:2516–2522. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.9.2516-2522.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marconi R T, Samuels D S, Schwan T G, Garon C F. Identification of a protein in several Borrelia species related to OspC of the Lyme disease spirochetes. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2577–2583. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.10.2577-2583.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Margolis N, Hogan D, Cieplak W, Jr, Schwan T G, Rosa P A. Homology between Borrelia burgdorferi OspC and members of the family of Borrelia hermsii variable major proteins. Gene. 1994;143:105–110. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90613-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Margolis N, Hogan D, Tilly K, Rosa P A. Plasmid location of Borrelia purine biosynthesis gene homologs. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6427–6432. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.21.6427-6432.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meier J T, Simon M I, Barbour A G. Antigenic variation is associated with DNA rearrangements in a relapsing fever Borrelia. Cell. 1985;41:403–409. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pennington P M, Allred C D, West C S, Alvarez R, Barbour A G. Arthritis severity and spirochete burden are determined by serotype in the Borrelia turicatae-mouse model of Lyme disease. Infect Immun. 1997;65:285–292. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.1.285-292.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pennington P M, Cadavid D, Barbour A G. Characterization of VspB of Borrelia turicatae, a major outer membrane protein expressed in blood and tissues of mice. Infect Immun. 1999;67:4637–4645. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.9.4637-4645.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pennington P M, Cadavid D, Bunikis J, Norris S J, Barbour A G. Extensive interplasmidic duplications change the virulence phenotype of the relapsing fever agent Borrelia turicatae. Mol Microbiol. 1999;34:1120–1132. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Plasterk R H, Simon M I, Barbour A G. Transposition of structural genes to an expression sequence on a linear plasmid causes antigenic variation in the bacterium Borrelia hermsii. Nature. 1985;318:257–263. doi: 10.1038/318257a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Restrepo B I, Barbour A G. Antigen diversity in the bacterium B. hermsii through “somatic” mutations in rearranged vmp genes. Cell. 1994;78:867–876. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(94)90642-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Restrepo B I, Carter C J, Barbour A G. Activation of a vmp pseudogene in Borrelia hermsii: an alternate mechanism of antigenic variation during relapsing fever. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:287–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Restrepo B I, Kitten T, Carter C J, Infante D, Barbour A G. Subtelomeric expression regions of Borrelia hermsii linear plasmids are highly polymorphic. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:3299–3311. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb02198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sadziene A, Thomas D D, Barbour A G. Borrelia burgdorferi mutant lacking Osp: biological and immunological characterization. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1573–1580. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.4.1573-1580.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sadziene A, Thomas D D, Bundoc V G, Holt S H, Barbour A G. A flagella-less mutant of Borrelia burgdorferi. J Clin Investig. 1991;88:82–92. doi: 10.1172/JCI115308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sadziene A, Wilske B, Ferdows M S, Barbour A G. The cryptic ospC gene of Borrelia burgdorferi B31 is located on a circular plasmid. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2192–2195. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.2192-2195.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schwan T G, Hinnebusch B J. Bloodstream- versus tick-associated variants of a relapsing fever bacterium. Science. 1998;280:1938–1940. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5371.1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sohaskey C D, Arnold C, Barbour A G. Analysis of promoters in Borrelia burgdorferi by use of a transiently expressed reporter gene. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6837–6842. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.21.6837-6842.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sohaskey C D, Zückert W R, Barbour A G. The extended promoters for two outer membrane lipoprotein genes of Borrelia spp. uniquely include a T-rich region. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:41–51. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stevenson B, Porcella S F, Oie K L, Fitzpatrick C A, Raffel S J, Lubke L, Schrumpf M E, Schwan T G. The relapsing fever spirochete Borrelia hermsii contains multiple, antigen-encoding circular plasmids that are homologous to the cp32 plasmids of Lyme disease spirochetes. Infect Immun. 2000;68:3900–3908. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.7.3900-3908.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stoenner H G, Dodd T, Larsen C. Antigenic variation of Borrelia hermsii. J Exp Med. 1982;156:1297–1311. doi: 10.1084/jem.156.5.1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang J R, Hardham J M, Barbour A G, Norris S J. Antigenic variation in Lyme disease borreliae by promiscuous recombination of VMP-like sequence cassettes. Cell. 1997;89:275–285. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80206-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]