In the Journal of Hepatology, Marjot et al. reported that hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection was not significantly associated with mortality among coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients in univariable analysis and multivariable analysis [1]. Meanwhile, in the journal of Digestive Diseases and Sciences, a recent meta-analysis based on un-adjusted data demonstrated that COVID-19 patients infected with HBV had significantly higher risk for severity and mortality compared to those not infected with HBV [2]. This indicates whether or not HBV infection was significantly independently associated with COVID-19 severity has been yet unknown. Regarding that age and past medical history [3–5] are known confounding variables for the disease progression of COVID-19 patients, we therefore undertook a confounding variables-adjusted meta-analysis to clarify whether HBV infection was significantly independently associated with COVID-19 severity or not. We also investigated whether hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection was significantly independently associated with COVID-19 severity or not.

We undertook this meta-analysis in alignment with the preferred reporting item for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [6]. We systematically retrieved Scopus, Web of Science, Wiley Library, Springer Link, EMBASE, Elsevier ScienceDirect, PubMed, and Cochrane Library as of October 27, 2022, using the keywords: (“2019-nCoV,” “2019 novel coronavirus,” “SARS-CoV-2,” “severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2,” “COVID-19,” or “coronavirus disease 2019”) and (“hepatitis B virus,” “HBV,” “hepatitis C virus,” “HCV,” or “viral hepatitis”). Hand searches of relevant citations were performed in the references of eligible publications and pertinent reviews. The outcome of interest was defined as severity (such as death, intensive care unit admission, severe/critical illness, requirement for invasive mechanical ventilation, and severity/progression). We included all publications in English providing confounding variables-adjusted data on the relationship between HBV/HCV infection and COVID-19 severity. We excluded duplicate publication, study protocol, commentary, editorial, errata, preprint, case report, review, and literature with un-adjusted data. The exposure group was COVID-19 patients who had HBV/HCV infection, and the comparison group was COVID-19 patients who did not have HBV/HCV infection. Literature retrieval and data extraction were independently undertaken by two authors. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion. If the consensus was not achieved, a third author was invited to settle the matter.

Statistical analysis was conducted using Stata 11.2 software. The pooled effect size was presented as odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (95% CI) and synthesized by a random-effects meta-analysis model. The I2 statistics and Cochrane’s Q test were applied for examining the statistical heterogeneity between studies. Egger’s test was utilized for quantitative analysis of publication bias. Subgroup analyses by male proportion and age were performed. Leave-one-out sensitivity analysis was used for assessing the stability of the overall results.

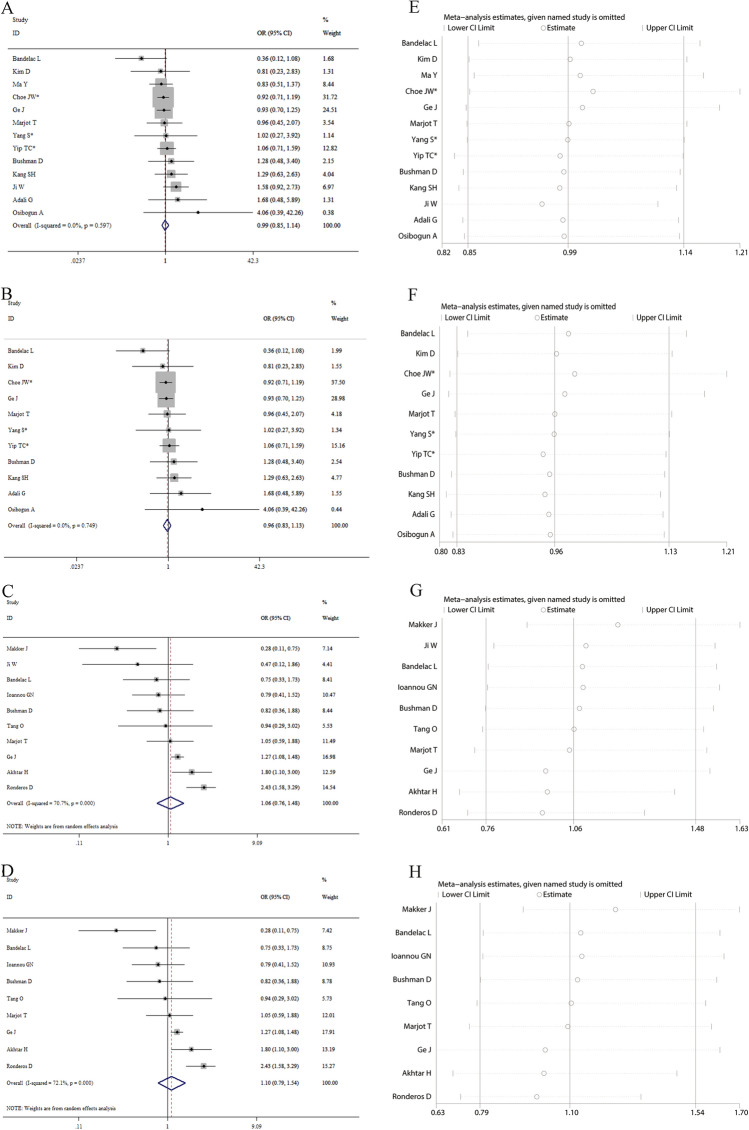

Our findings on the basis of confounding variables-adjusted data showed that HBV infection was not significantly independently linked to the odds risk for COVID-19 severity (pooled OR 0.99, 95% CI 0.85–1.14; Fig. 1A) and mortality (pooled OR 0.96, 95% CI 0.83–1.13; Fig. 1B). We also found that HCV infection was not significantly independently linked to the odds risk for COVID-19 severity (pooled OR 1.06, 95% CI 0.76–1.48; Fig. 1C) and mortality (pooled OR 1.10, 95% CI 0.79–1.54; Fig. 1D). Subgroup analyses by age and male proportion yielded consistent results: age (HBV: pooled OR 1.00, 95% CI 0.87–1.16 for age < 60 years, and 0.70, 95% CI 0.37–1.31 for age ≥ 60 years; HCV: pooled OR 1.24, 95% CI 0.89–1.74 for age < 60 years, and 0.91, 95% CI 0.49–1.72 for age ≥ 60 years) and proportion of males (HBV: pooled OR 1.01, 95% CI 0.86–1.18 for < 50%, and 0.91, 95% CI 0.66–1.25 for ≥ 50%; HCV: pooled OR 1.37, 95% CI 0.80–2.33 for < 50%, and 0.87, 95% CI 0.55–1.38 for ≥ 50%). Sensitivity analysis exhibited that removing each individual study one time did not obviously influence the overall results (Fig. 1E for HBV and severity, Fig. 1F for HBV and mortality, Fig. 1G for HCV and severity, and Fig. 1H for HCV and mortality), which suggested that our results were reliable and robust. No publication bias was detected in Egger’s test (P = 0.389 for HBV and 0.194 for HCV).

Fig. 1.

A total of eighteen studies were included in this meta-analysis. Among them, there were thirteen studies with 89,088 cases reporting adjusted effect sizes on the relationship between hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) severity and ten studies with 64,328 cases reporting adjusted effect sizes on the relationship between hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and COVID-19 severity. Forest plots indicated that HBV/HCV infection was not significantly independently associated with the odds risk for severity and morality of COVID-19 patients (A for HBV and severity, B for HBV and mortality, C for HCV and severity, and D for HCV and mortality, respectively). Leave-one-out sensitivity analysis demonstrated that sequentially eliminating each individual study had no significant influences on the overall results (E for HBV and severity, F for HBV and mortality, G for HCV and severity, and H for HCV and mortality, respectively), which suggested that our results were robust and reliable. * indicated the combined effect sizes were estimated on the basis of the data from subgroups

Only one included study investigated the relationship between HBV infection and COVID-19 severity in the subgroup by antiviral agent treatment, and only two included studies explored the relationship between HBV infection and COVID-19 severity in the subgroup by different HBV status. None of the included studies investigated the relationship between HBV/HCV infection and COVID-19 severity in the subgroups by vaccination status, medications, and SARS-CoV-2 variations. Therefore, the effects of other confounding variables such as HBV/HCV status, vaccination status, medications, and SARS-CoV-2 variations [7–9] on the relationship between HBV/HCV infection and COVID-19 severity could not be evaluated currently.

In conclusion, our meta-analysis of confounding variables-adjusted data indicated that HBV/HCV infection was not significantly independently associated with COVID-19 severity. Future well-designed studies are needed to verify our findings.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Li Shi, Xueya Han, Ying Wang, Mengke Hu, Peihua Zhang, Jiahao Ren, Yang Li, Shuwen Li, Hongjie Hou, Ruiying Zhang, Xuan Liang, Jian Wu, Liqin Shi and Wenwei Xiao (All are from Department of Epidemiology, School of Public Health, Zhengzhou University) for their kind help in literature search and data collection.

Author’s contribution

HY conceptualized the study. JX and HF performed literature search, JX and YW performed data extraction. JX and FL analyzed the data. HY and JX wrote the manuscript. All the authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82273696) and Henan Young and Middle-aged Health Science and Technology Innovation Talent Project (No. YXKC2021021). The funders have no role in the data collection, data analysis, preparation of manuscript and decision to submission.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are included in this article and available from the corresponding author upon reasonable requests.

Declarations

Competing interests

All authors report that they have no potential conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Marjot T, Buescher G, Sebode M, Barnes E, Barritt AS, Armstrong MJ, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2021;74:1335–1343. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yu Y, Li X, Wan T. Effects of Hepatitis B Virus Infection on Patients with COVID-19: A Meta-Analysis. Dig Dis Sci. (Epub ahead of print). 10.1007/s10620-022-07687-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Ji D, Qin E, Xu J, Zhang D, Cheng G, Wang Y, et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver diseases in patients with COVID-19: A retrospective study. J Hepatol. 2020;73:451–453. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.03.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marjot T, Moon AM, Cook JA, Abd-Elsalam S, Aloman C, Armstrong MJ, et al. Outcomes following SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with chronic liver disease: An international registry study. J Hepatol. 2021;74:567–577. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iavarone M, D'Ambrosio R, Soria A, Triolo M, Pugliese N, Del Poggio P, et al. High rates of 30-day mortality in patients with cirrhosis and COVID-19. J Hepatol. 2020;73:1063–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cornberg M, Eberhardt CS. Protected or not protected, that is the question - First data on COVID-19 vaccine responses in patients with NAFLD and liver transplant recipients. J Hepatol. 2021;75:265–266. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krassenburg LAP, Maan R, Ramji A, Manns MP, Cornberg M, Wedemeyer H, et al. Clinical outcomes following DAA therapy in patients with HCV-related cirrhosis depend on disease severity. J Hepatol. 2021;74:1053–1063. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cornberg M, Buti M, Eberhardt CS, Grossi PA, Shouval D. EASL position paper on the use of COVID-19 vaccines in patients with chronic liver diseases, hepatobiliary cancer and liver transplant recipients. J Hepatol. 2021;74:944–951. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are included in this article and available from the corresponding author upon reasonable requests.