Abstract

We have characterized a host-induced virulence gene, mig-14, that is required for fatal infection in the mouse model of enteric fever. mig-14 is present in all Salmonella enterica subspecies I serovars and maps to a region of the chromosome that appears to have been acquired by horizontal transmission. A mig-14 mutant replicated in host tissues early after infection but was later cleared from the spleens and livers of infected animals. Bacterial clearance by the host occurred concomitantly with an increase in gamma interferon levels and recruitment of macrophages, but few neutrophils, to the infection foci. We hypothesize that the mig-14 gene product may repress immune system functions by interfering with normal cytokine expression in response to bacterial infections.

There are six subspecies of Salmonella enterica that are capable of colonizing both warm- and cold-blooded animals (1, 9). S. enterica subspecies I serovars are strictly associated with infection of warm-blooded animals and can cause a wide a range of diseases, including gastroenteritis, bacteremia, and typhoid fever (11). S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (from here on referred to as serovar Typhimurium) is the causative agent of gastroenteritis in humans and a typhoid-like disease in mice (11). Serovar Typhimurium survives and replicates within phagocytic cells of the reticuloendothelial system, resulting in the release of proinflammatory cytokines in response to bacterial compounds such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and peptidoglycan (11, 16, 17, 20). Two of these inflammatory cytokines, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and gamma interferon (IFN-γ), are required for host clearance of Salmonella infections (11, 12, 16, 18). Treatment of infected animals with IFN-γ decreases the numbers of bacteria found in the spleen early in infection, and injection of anti-TNF-α or anti-IFN-γ abolishes the ability of mice to clear sublethal doses of serovar Typhimurium (12, 26, 27). Recently, it has been reported that modified Salmonella lipid A (an LPS component) can reduce the LPS-mediated expression of TNF-α by human monocytes and E-selectin by endothelial cells (14). These lipid A modifications are regulated by the PhoP/PhoQ virulence regulon (7, 13), suggesting a potential role for PhoP/PhoQ-activated genes not only in intracellular survival but also in lowering cytokine and chemokine production.

In the present study we characterized the virulence properties and evolutionary history of a host-induced serovar Typhimurium factor with potential immunomodulatory functions. A previous study described a PhoP/PhoQ-dependent, macrophage-inducible promoter, fmi-14, which exhibited a 22-fold induction within murine macrophages (36). To identify the open reading frame (ORF) associated with fmi-14, we isolated an adjacent 2.2-kb serovar Typhimurium DNA fragment by recombinational cloning (6). Sequence analysis of this fragment revealed a single ORF (mig-14) encoding a putative 298-amino-acid (aa) soluble polypeptide with limited homology to Bacillus subtilis RecG, an ATP-dependent DNA helicase (27% identity over a 102-aa overlap), and the LysR-like activator AppY from Escherichia coli (30% identity over 59 aa). To disrupt mig-14, a 1.6-kb ClaI fragment containing the 5′ end of mig-14 was cloned into the allelic-exchange vector pRTP-1 (34), and an ΩKanr (aph) cassette (8) was inserted at a unique BclI site within the mig-14 coding sequence. The resulting plasmid was transformed into serovar Typhimurium strain SL1343R (trp rpsL) and gene replacement events were identified by Southern blot hybridization. The mig-14::aph mutation was mobilized into the virulent strain SL1344 (xyl hisG rpsL) by P22-HT-mediated transduction to create the strain RVY-5.

Virulence defects of mig-14 mutants.

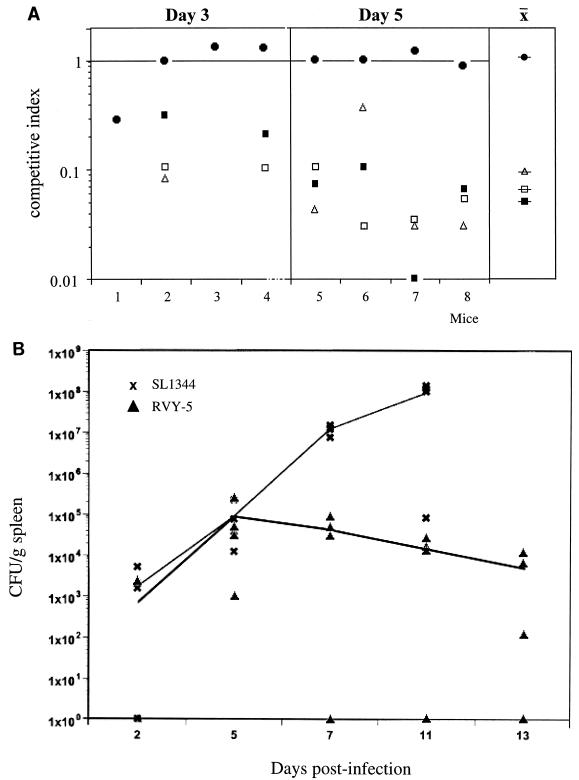

We characterized the virulence defects of RVY-5 by determining the competitive index (CI) of the mutant strains at various time points. The CI is the ratio of RVY-5 to SL1344 present in different organs after challenge with a 1:1 ratio of wild-type to mutant bacteria. Groups of four female BALB/c mice were injected intraperitoneally with an equal mixture of SL1344 and RVY-5 (5 × 102 bacteria total). The mice were killed at days 3 and 5 postinfection; the spleens and livers were collected, homogenized, and plated on selective media to determine the number of CFU of each input strain. At day 3, RVY-5 and SL1344 were equally efficient at colonizing the liver (mean CI = 0.49 ± 0.29) and spleen (mean CI = 0.81 ± 0.27). However, by day 5, RVY-5 showed an ∼10- to 50-fold reduction in its ability to compete with SL1344 (liver mean CI = 0.09 ± 0.07; spleen mean CI = 0.17 ± 0.16). To determine whether the mig-14 mutation would impair the ability of serovar Typhimurium to colonize the gut-associated lymphoid tissue, we performed mixed infections and calculated the CI of RVY-5 after oral inoculation (Fig. 1A). Groups of four mice were inoculated intragastrically with equal numbers (106 bacteria total) of SL1344 and RVY-5. The animals were killed at days 3 and 5 postinfection, and bacteria from the Peyer's patches (PP), mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN), spleen, and liver were recovered on selective plates. At day 3 postinfection, RVY-5 colonized the PP as efficiently as SL1344 (at this time point only two out of the four mice showed bacterial spread beyond the MLN). At day 5, the bacterial load of RVY-5 in the PP was still similar to that of SL1344, yet we observed a 15- to 30-fold decrease in RVY-5's CI in the spleen and liver (Fig. 1A). Since it is possible that the RVY-5 CI in the spleen and liver reflects a delayed kinetics in the seeding of these organs rather than survival defects, we compared the growth kinetics of RVY-5 in the spleen and liver. Mice were infected orally with either 5 × 106 SL1344 organisms or 5 × 106 RVY-5 organisms (four mice per strain per time point). Animals were killed at days 2, 5, 7, 11, and 13 postinfection, and the numbers of CFU per gram of tissue were determined. Early during infection (day 2 and day 5) the bacterial load in the liver and spleen increased at similar rates in mice infected with both RVY-5 and SL1344. At day 5 the mean log10 CFU of SL1344 was 4.71 ± 0.53 (n = 4) and that of RVY-5 was 4.39 ± 1.01 (n × 4). After day 5, the number of CFU per gram of tissue began to decrease in RVY-5-infected mice, and by day 13, the animals displayed a low-level chronic infection with no outward symptoms of disease (spleen log10 CFU of 4.71 ± 0.18 [n = 3] at day 7, 4.24 ± 0.16 [n = 3] at day 11, and 3.89 ± 1.29 [n = 3] at day 13). In contrast, SL1344 replicated exponentially until the deaths of the animals occurred, between days 7 and 11 (log10 CFU of 7.06 ± 0.12 [n = 4] at day 7 and 7.28 ± 1.38 [n = 4] at day 11). These experiments indicated that RVY-5 was capable of replicating in mice early during infection but was unable to overcome the host defenses at later stages. The bacterial load in mice infected with RVY-5 continued to decrease, so that 45 days after the oral inoculation with >106 CFU, no bacteria could be recovered from infected tissues (data not shown), suggesting that RVY-5 was cleared from tissues rather than persisting as a chronic infection. The oral 50% lethal dose (LD50) for RVY-5 in BALB/c mice was determined by infection with 10-fold dilutions of either SL1344 or RVY-5 and monitored for 45 days. The oral LD50 (31) for RVY-5 was 1.21 × 108 bacteria per mouse, while the LD50 for SL1344 was less than 1 × 103 bacteria per mouse, suggesting that the competition experiments had underestimated the virulence defects of mig-14 mutants. One possible explanation for the discrepancy between the CI and the LD50 measurements is that the mig-14 mutation may be partially complemented in trans by coinfection with wild-type serovar Typhimurium. In support of this, we have observed that in mixed infections performed with higher infectious doses, mig-14 mutants replicate at rates similar to those of wild-type bacteria (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Virulence defects of mig-14 mutants. (A) Growth defects of RVY-5 in mixed infections. Groups of four mice were infected orally with a 1:1 mixture of SL1344 (wild type) and RVY-5 (mig-14::aph) (106 CFU per mouse). At days 3 and 5 postinfection, PP (●), MLN (□), spleens (S) (■), and livers (L) (▵) were collected and the number of CFU for each strain was determined. The CI for RVY-5 was calculated as the ratio of RVY-5 to SL1344 recovered from the various organs. At day 3 postinfection, both strains colonized the PP, but RVY-5 was less efficient at colonizing the MLN, S, and L. At day 5, the CI for RVY-5 in the PP was about 1, while the CI in the MLN, L, and S ranged from 0.1 to 0.01 (x = mean CI at day 5). (B) In vivo growth kinetics of RVY-5. Groups of four mice were infected orally with either SL1344 or RVY-5 (5 × 106 organisms per mouse) and the numbers of CFU per gram of spleen were determined at days 2, 5, 7, 11, and 13 (see text). For days 5, 7, and 11 the statistical difference in the mean log10 CFU per gram of spleens infected with either SL1344 or RVY-5 was determined with the Student t test. At day 5, the mean CFU per gram of spleen for SL1344 and RVY-5 were not significantly different (P > 0.2). At day 7 and day 11, the differences in mean CFU per gram of spleen were significant (P < 0.001). Data shown are representative of at least three independent experiments.

We confirmed that the virulence defect of RVY-5 was not due to polar effects of the Ω interposon on the expression of other genes by introducing mig-14 on an episomal element into RVY-5. mig-14 was amplified by PCR and inserted as an EcoRI fragment into the miniF-derived vector pBDJ121 (Ampr) (gift of B. Jones). The resulting plasmid, pMIG14, was transformed into RVY-5 by electroporation. Groups of five mice were infected intragastrically with 106 CFU of SL1344, RVY-5, or RVY-5(pMIG14). SL1344 and RVY-5(pMIG14) killed all mice within 6 to 10 days, whereas all mice infected with RVY-5 survived.

Pathology and cytokine profiles of RVY-5-infected mice.

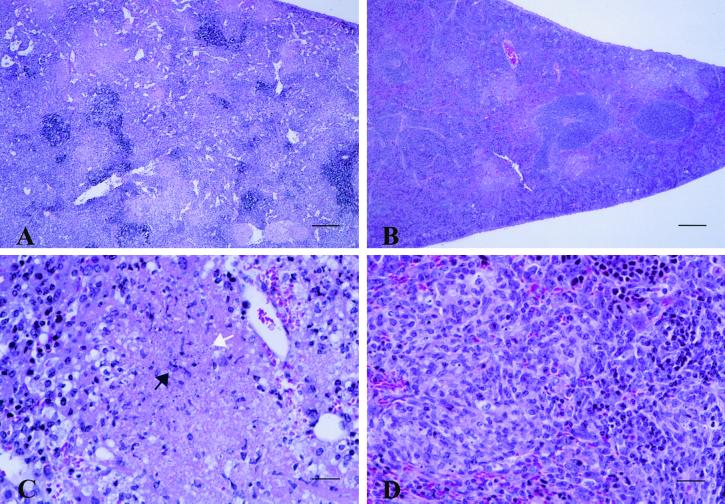

We assessed the virulence properties of RVY-5 in tissue culture models of infection and have determined that mig-14 is not required for invasion or replication within cultured or primary macrophages (data not shown). However, RVY-5 has a survival defect in the spleens and livers of infected animals during the later stages of infection, suggesting that RVY-5 may be more susceptible to clearance by the host after the immune system has been stimulated. We investigated the pathology of RVY-5 infections by collecting spleens, livers, MLN, and PP from mice infected with 106 RVY-5 or SL1344 organisms at 2, 6, and 11 days after oral inoculation. The tissues were fixed in 10% buffered neutral formalin solution, processed for routine histology, and examined by light microscopy. In both groups of mice, the most consistent and striking lesions were found in the spleen (Fig. 2) and liver (not shown). At day 2 postinfection, rare to scattered neutrophil accumulations surrounding central necrotic cell debris were found in the splenic red pulp in four out of five mice infected with SL1344 and in three out of five mice infected with RVY-5 (data not shown). However, at day 6, the splenic lesions induced by RVY-5 were strikingly different from lesions induced by SL1344. SL1344-infected mice had severe coalescing splenic necrosis, while RVY-5-infected mice had lower numbers of inflammatory foci composed of mononuclear and fibroblastic cells, few neutrophils, and minimal necrosis (Fig. 2). The severe parenchymal necrosis and the lack of resolution of splenic and liver abscesses in the SL1344-infected mice most likely contributed to the mortality observed after day 6 postinoculation.

FIG. 2.

Histopathology of mice infected with SL1344 and RVY-5. At day 6 postinfection, the overall splenic architecture is disrupted in mice infected with SL1344 (A). Necrotic cell debris (white arrow) predominates and rare viable neutrophils (black arrow) are present (C). In contrast, at 6 days postinfection, normal splenic architecture is largely maintained in the spleens of RVY-5-infected mice (B) and the affected areas contain chronic inflammatory cells consisting of mononuclear cells (lymphocytes, macrophages, and plasma cells), fibroblasts, few neutrophils, and minimal necrosis (D). Spleens were removed from infected mice, fixed in 10% buffered neutral formalin, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with hemotoxylin-eosin. (Bars = 200 μm in panels A and B [×10], and 25 μm in panels C and D [×80].)

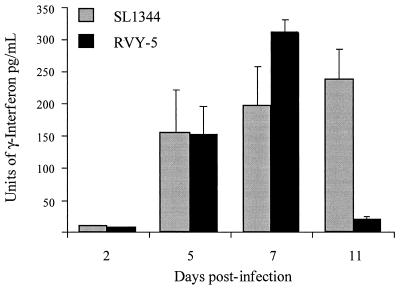

We examined the role of host response to serovar Typhimurium infection by examining the serum cytokine profiles of mice infected with either RVY-5 or SL1344 (Fig. 3). Blood was collected in a terminal bleed from the hearts of infected animals on days 2, 5, 7, and 11 postinfection. The number of CFU in the spleen and the levels of inflammatory cytokines (IFN-γ and TNF-α) in the circulating blood were determined with a capture cytokine enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Genzyme). The levels of TNF-α in the sera of RVY-5- and SL1344-infected mice were not significantly different between days 2 and 7 postinfection (data not shown). In contrast, mice infected with SL1344 and RVY-5 displayed a differential IFN-γ response. As previously reported (19, 30), SL1344-infected mice showed steadily increasing levels of IFN-γ until the deaths of the animals occurred (days 7 and 11). Interestingly, mice infected with RVY-5 showed IFN-γ levels significantly higher than those of serum from SL1344-infected mice (day 7), even though the bacterial load of RVY-5 was 100- to 1,000-fold lower than that of SL1344. These results suggest that infected mice were able to mount a stronger IFN-γ response to RVY-5 than to SL1344.

FIG. 3.

Serum IFN-γ profiles of infected mice. Blood was collected from the hearts of infected mice on days 2, 5, 7, and 11 after the oral infection, and cytokine enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for IFN-γ was performed on the serum. Spleens were removed and homogenized and CFU per gram of spleen were determined. On day 2 all animals displayed serum cytokine levels largely below the threshold of sensitivity of the detection kit. By day 5, mice infected with RVY-5 and SL1344 had similar levels of cytokines and bacterial loads in the spleen (log10 CFU, 3.48 ± 0.9 [n = 4] for SL1344 and 3.31 ± 0.81 [n = 4] for RVY-5). At day 7, RVY-5-infected mice displayed significantly higher levels of IFN-γ than mice infected with SL1344 even though the bacterial loads present in lymphoid organs were significantly lower (log10 CFU per gram of spleen, 5.75 ± 0.5 [n = 4] for SL1344 and 2.75 ± 0.06 [n = 4] for RVY-5). By day 11, concomitantly with clinical recovery, there was a drastic decrease in cytokine production in mice infected with RVY-5.

IFN-γ enhances the macrophage's capacity to generate respiratory bursts, increases the rate of lysosomal fusion with bacterium-containing phagosomes, and stimulates the production of nitric oxide (NO) from inducible NO synthase (iNOS) (39). Innate immune responses to intracellular pathogens, such as serovar Typhimurium, begin with interleukin-12 (IL-12) production by infected cells, leading to IFN-γ production by NK cells, which results in iNOS activation in macrophages (4). In vivo depletion of IL-12 with anti-IL-12 antibodies or inhibition of NO production with NG-monomethyl-l-arginine augments serovar typhimurium growth in infected tissues (18, 21–24, 35). NO has been reported to have bacteriostatic properties but is also required for proper macrophage and neutrophil migration into the infected spleen (23). We hypothesize that a robust IFN-γ response to RVY-5 may explain why the mice contained the growth of this mutant but not of its isogenic wild-type parent. It is possible that by interfering with the ability of the host to mount a full IFN-γ response, serovar Typhimurium enhances its survival during chronic infections. Future experiments will be aimed at determining which cytokine/chemokine response pathway may be compromised in mice infected with serovar Typhimurium.

mig-14 is part of a horizontally acquired set of genes.

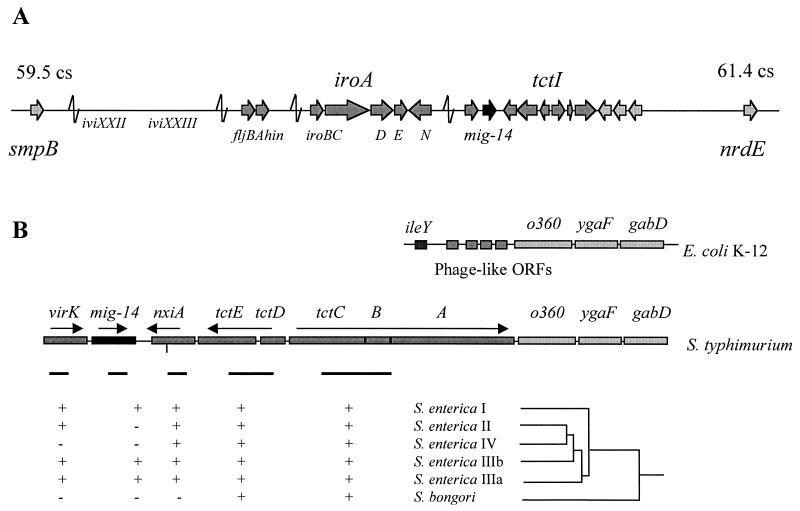

The 2.2-kb DNA fragment containing mig-14 has a 39.9% GC content. This is in marked contrast with the GC content of the Salmonella chromosome (52%) (1). Since virulence genes with a low GC content are often part of larger clusters of virulence genes (pathogenicity islands), we isolated a 9-kb EcoRI fragment of the Salmonella chromosome containing mig-14 and adjacent genes. DNA sequence analysis of this region indicated that mig14 maps to centisome 61 (smpB-nrdE intergenic region) in the S. enterica chromosome. This region of the Salmonella chromosome (centisomes 59 to 61) contains several genetic markers that are absent from the E. coli chromosome and which are responsible for some of Salmonella's unique physiological and biochemical characteristics (Fig. 4). The 9-kb EcoRI fragment contained 10 ORFs adjacent to mig-14. One ORF, present at the 5′ border of mig-14, encodes a putative protein with significant homology to the Shigella flexneri VirK. VirK is required for the posttranslational processing of the intracellular spreading factor IcsA (28). The nine ORFs at the 3′ border of mig-14 encode NxiA, a putative Ni2+-containing hydrogenase; TctE and TctD, two previously described regulators of tricarboxylate transport in S. enterica (38); three ORFs encoding a putative periplasmic membrane protein and two integral membrane proteins that are likely responsible for tricarboxylate transport (37); and three ORFs with high nucleotide homology to the E. coli genes o360, ygaF, and gabD (5) (Fig. 4). mig-14 appears to be the only virulence factor gene in this region since serovar Typhimurium strains bearing mutations in virK, nxiA, and the structural (tctI) and regulatory (tctDE) genes of the tct locus were able to kill mice after an oral challenge with 106 bacteria per animal (reference 2 and data not shown). This was not unexpected since we have observed, through the use of gfp fusions, that neither the tct locus nor nxiA is induced in host cells (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

The mig-14 locus. (A) mig-14 is located in a region of the Salmonella chromosome known to harbor horizontally acquired virulence genes and other Salmonella-specific genes. The map location of ivi genes, iroN, and virK has been previously described (2, 3, 15, 33). (B) mig-14 is flanked by genes encoding a putative nickel transporter (nxiA) and a tricarboxylate transport apparatus (tctI) and homologues of the S. flexneri virK gene and the E. coli ORFs o360, ygaF, and gabD. In E. coli, o360 and ygaF are adjacent to phage-like ORFs and the tRNA ileY (5). DNA hybridization experiments with PCR-generated probes (black bars) spanning internal regions of virK, mig-14, nxiA, tctDE, and tctC indicated that mig-14 is present only in S. enterica subtypes I, IIIa, and IIIb. In contrast, the adjacent gene nxiA is present in all S. enterica subtypes but not S. bongori, while the tctI locus is found in all Salmonella species tested. The dendrogram (not to scale) shows the evolutionary relationship between varied Salmonella serovars as determined by DNA hybridization and multilocus enzyme electrophoresis (32). Representative serovars tested were S. bongori 48:z35:− and 44:r:− and S. enterica subgroup I serovars Typhi, Enteriditis, Choleraesuis, Dublin, and Gallinarum, subgroup II serovars Phoenix and 50:b:z6, subgroup IIIa serovars 48:g1z51:− and 41:z41z23:−, subgroup IIIb serovars 50:k:z and 61::c:z35, and subgroup IV serovars Marina and Chameleon.

In E. coli, o360 is adjacent to small ORFs with homology to phage components and ileY, encoding a tRNA (5). Since several phages and pathogenicity islands have been described to insert at tRNA sites (1, 9, 10), it is possible that the acquisition of S. enterica-specific genes at this locus may have begun by multiple insertions at ileY. Bäumler and Heffron have described this region of the Salmonella chromosome as containing a “mosaic-like structure” in which different segments are present (or absent) in different S. enterica and Salmonella bongori serovars (2). This is in contrast to pathogenicity islands, where large clusters of genes appear to have been acquired as a unit. Sequence analysis of the region spanning virK, mig-14, nxiA, the tctI operon, and the S. enterica homologues of o360 and ygaF indicated the presence of directed and inverted repeats between mig-14, nxiA, and virK. For example, the 3′ end of mig-14 displays two tandem 35-bp direct repeats approximately 300 bp downstream of the putative transcriptional terminator. To test the possibility that each ORF was acquired (or deleted) independently during the evolution of S. enterica, we probed a collection of S. enterica and S. bongori isolates for the presence of different segments of the mig-14 locus (Fig. 4). These DNA hybridization experiments indicated that mig-14 was acquired by S. enterica after its split from the S. bongori lineage but was subsequently deleted in S. enterica subspecies II (Salamae) and IV (Houtenae). Furthermore, the acquisition or deletion of mig-14 appears to have occurred independently of its neighboring genes virK and nxiA.

Mig-14 appears to be a unique virulence factor. Unlike the bulk of virulence genes, mig-14 has no apparent role in the primary metabolism or housekeeping functions of the bacterium, it has been acquired as a mobile genetic element, and its expression is restricted to the intracellular environment of host cells (36). More importantly, mig-14 appears to be a late-acting factor, because the phenotype of the mutant is not apparent until several days postcolonization. The molecular function of Mig-14 is unclear. The limited homology of Mig-14 to DNA-interacting proteins could indicate a potential role in the regulation of gene expression. If this is the case, it can be expected that the expression of other late-acting virulence factors would be under the control of Mig-14 and, indirectly, of PhoP/PhoQ. Future experiments will be aimed at determining the molecular mechanism of Mig-14 function and its potential role in immunomodulation.

A recurrent theme in Salmonella pathogenesis is the presence of mobile genetic elements that enhance the bacterium's pathogenic properties by conferring a broader host range or resistance to the host's immune system (1, 25, 29). A region of genetic “plasticity” in the chromosome, such as that encountered at centisome 61, may have permitted the rapid acquisition and deletion of virulence factors, such as Mig-14, as S. enterica species adapted to new warm-blooded hosts.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The EcoRI fragment of the Salmonella chromosome containing mig-14 and adjacent genes has been deposited in GenBank under accession no. AF020810.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge members of the Falkow laboratory for helpful discussions and Bruce Stocker for supplying S. enterica and S. bongori serovar collections.

This work was supported by PHS grant AI26195.

R.H.V. and D.M.C. contributed equally to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bäumler A J. The record of horizontal gene transfer in Salmonella. Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:318–322. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01082-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bäumler A J, Heffron F. Mosaic structure of the smpB-nrdE intergenic region of Salmonella enterica. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2220–2223. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.8.2220-2223.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bäumler A J, Norris T L, Lasco T, Voigt W, Reissbrodt R, Rabsch W, Heffron F. IroN, a novel outer membrane siderophore receptor characteristic of Salmonella enterica. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1446–1453. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.6.1446-1453.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biron C A, Gazzinelli R T. Effects of IL-12 on immune responses to microbial infections: a key mediator in regulating disease outcome. Curr Biol. 1995;7:485–496. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(95)80093-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blattner F R, Plunkett G, 3rd, Bloch C A, Perna N T, Burland V, Riley M, Collado-Vides J, Glasner J D, Rode C K, Mayhew G F, Gregor J, Davis N W, Kirkpatrick H A, Goeden M A, Rose D J, Mau B, Shao Y. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science. 1997;277:1453–1474. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cirillo D M, Valdivia R H, Monack D M, Falkow S. Macrophage-dependent induction of the Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 type III secretion system and its role in intracellular survival. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:175–188. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ernst R K, Guina T, Miller S I. How intracellular bacteria survive: surface modifications that promote resistance to host innate immune responses. J Infect Dis. 1999;179(Suppl. 2):S326–S330. doi: 10.1086/513850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fellay R, Frey J, Krisch H. Interposon mutagenesis of soil and water bacteria: a family of DNA fragments designed for in vitro insertional mutagenesis of gram negative bacteria. Gene. 1987;52:147–154. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Groisman E A, Ochman H. How Salmonella became a pathogen. Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:343–349. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01099-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Groisman E A, Ochman H. Pathogenicity islands: bacterial evolution in quantum leaps. Cell. 1996;87:791–794. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81985-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gulig P A. Pathogenesis of systemic disease. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Vol. 2. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 2774–2787. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gulig P A, Doyle T J, Clare-Salzler M J, Maiese R L, Matsui H. Systemic infection of mice by wild-type but not Spv−Salmonella typhimurium is enhanced by neutralization of gamma interferon and tumor necrosis factor alpha. Infect Immun. 1997;65:5191–5197. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.12.5191-5197.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gunn J S, Belden W J, Miller S I. Identification of PhoP-PhoQ activated genes within a duplicated region of the Salmonella typhimurium chromosome. Microb Pathog. 1998;25:77–90. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1998.0217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo L, Lim K B, Gunn J S, Bainbridge B, Darveu R P, Hackett M, Miller S I. Regulation of lipid A modifications by Salmonella typhimurium virulence genes phoP-phoQ. Science. 1997;276:250–253. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5310.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heithoff D M, Conner C P, Hanna P C, Julio S M, Hentschel U, Mahan M J. Bacterial infection as assessed by in vivo gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:934–939. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.3.934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones B D. Host responses to pathogenic Salmonella infection. Genes Dev. 1997;11:679–687. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.6.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones B D, Falkow S. Salmonellosis: host immune responses and bacterial virulence determinants. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:533–561. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jouanguy E, Doffinger R, Dupuis S, Pallier A, Altare F, Casanova J L. IL-12 and IFN-gamma in host defense against mycobacteria and salmonella in mice and men. Curr Opin Immunol. 1999;11:346–351. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(99)80055-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karem K L, Kanangat S, Rouse B T. Cytokine expression in the gut associated lymphoid tissue after oral administration of attenuated Salmonella vaccine strains. Vaccine. 1996;14:1495–1502. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(96)00118-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khan S A, Everest P, Servos S, Foxwell N, Zahringer U, Brade H, Rietschel E T, Dougan G, Charles I G, Maskell D J. A lethal role for lipid A in Salmonella infections. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:571–579. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00952.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kincy-Cain T, Bost K L. Increased susceptibility of mice to Salmonella infection following in vivo treatment with the substance P antagonist, spantide II. J Immunol. 1996;157:255–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kincy-Cain T, Clements J D, Bost K L. Endogenous and exogenous interleukin-12 augment the protective immune response in mice orally challenged with Salmonella dublin. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1437–1440. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.4.1437-1440.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.MacFarlane A S, Schwacha M G, Eisenstein T K. In vivo blockage of nitric oxide with aminoguanidine inhibits immunosuppression induced by an attenuated strain of Salmonella typhimurium, potentiates Salmonella infection, and inhibits macrophage and polymorphonuclear leukocyte influx into the spleen. Infect Immun. 1999;67:891–898. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.2.891-898.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mastroeni P, Harrison J A, Chabalgoity J A, Hormaeche C E. Effect of interleukin 12 neutralization on host resistance and gamma interferon production in mouse typhoid. Infect Immun. 1996;64:189–196. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.1.189-196.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miao E A, Miller S I. Bacteriophages in the evolution of pathogen-host interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:9452–9454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muotiala A. Anti-IFN-gamma-treated mice—a model for testing safety of live Salmonella vaccines. Vaccine. 1992;10:243–246. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(92)90159-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muotiala A, Makela P H. The role of IFN-gamma in murine Salmonella typhimurium infection. Microb Pathog. 1990;8:135–141. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(90)90077-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakata N C, Sasakawa C, Okada N, Tobe T, Fukuda I, Suzuki T, Komatsu K, Yoshikawa M. Identification and characterization of virK, a virulence-associated large plasmid gene essential for intercellular spreading of Shigella flexneri. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:2387–2395. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ochman H, Groisman E A. Distribution of pathogenicity islands in Salmonella spp. Infect Immun. 1996;64:5410–5412. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.5410-5412.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramarathinam L, Shaban R A, Niesel D W, Klimpel G R. Interferon gamma (IFN-gamma) production by gut-associated lymphoid tissue and spleen following oral Salmonella typhimurium challenge. Microb Pathog. 1991;11:347–356. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(91)90020-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reed L J, Muench H. A simple method for estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am J Hyg. 1938;27:493–497. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reeves M W, Evins G M, Heiba A A, Plikaytis B D, Farmer J J., III Clonal nature of Salmonella typhi and its genetic relatedness to other salmonellae as shown by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis, and proposal of Salmonella bongori comb. nov. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:313–320. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.2.313-320.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanderson K E, Hessel A, Rudd K E. Genetic map of Salmonella typhimurium, edition VIII. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:241–303. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.2.241-303.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stibitz S, Black W, Falkow S. The construction of a cloning vector for gene replacement in Bordetella pertussis. Gene. 1986;50:133–140. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(86)90318-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Umezawa K, Akaike T, Fujii S, Suga M, Setoguchi K, Ozawa A, Maeda H. Induction of nitric oxide synthesis and xanthine oxidase and their roles in the antimicrobial mechanism against Salmonella typhimurium infection in mice. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2932–2940. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.7.2932-2940.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Valdivia R H, Falkow S. Fluorescence-based isolation of bacterial genes expressed within host cells. Science. 1997;277:2007–2011. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5334.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Widenhorn K A, Somers J M, Kay W W. Expression of the divergent tricarboxylate transport operon (tctI) of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:3223–3227. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.7.3223-3227.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Widenhorn K A, Somers J M, Kay W W. Genetic regulation of the tricarboxylate transport operon (tctI) of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:4436–4441. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.8.4436-4441.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Young H A, Hardy K J. Role of interferon-gamma in immune cell regulation. J Leukoc Biol. 1995;58:373–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]