Abstract

Background

Breast cancer is the most common cancer worldwide, and despite remarkable progress in its treatment, the survivors’ quality of life is hampered by treatment-related side effects that impair psychosocial and physiological outcomes. Several studies have established the benefits of physical exercise in breast cancer survivors in recent years. Physical exercise reduces the impact of treatment-related adverse events to promote a better quality of life and functional outcomes.

Aim

This study aims to provide an overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses on the effect of physical exercise on the health-related quality of life, cardiorespiratory fitness, muscle strength, and body composition of breast cancer survivors.

Methods

PubMed and Cochrane databases were searched for systematic reviews and meta-analyses from January 2010 to October 2022. The main focus was ascertaining the effectiveness of physical exercise in breast cancer survivors undergoing curative treatment (surgery and/or radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy). Two reviewers independently screened the literature, extracted the data, and assessed the risk of bias in the included studies.

Results

A total of 101 studies were identified, and 12 were yielded for final analysis. The eligible studies included nine systematic reviews/meta-analyses, one meta-analysis/meta-regression, and two systematic reviews. The number of randomised clinical trials included in each review varied from 11 to 63, and the number of participants was from 214 to 5761. A positive and significant effect of different physical exercise interventions on health-related quality of life was reported in 83.3% (10 studies) of the eligible studies. Physical exercise also improved cardiorespiratory fitness (3 studies; 25%) and showed to be effective in reducing body weight (3 studies; 25%) and waist circumference (4 studies; 33.3%).

Conclusions

Our results suggest that physical exercise is an effective strategy that positively affects breast cancer survivors’ quality of life, cardiorespiratory fitness, and body composition. Healthcare professionals should foster the adoption of physical exercise interventions to achieve better health outcomes following breast cancer treatments.

Systematic review registration

https://inplasy.com/inplasy-2022-11-0053/, identifier INPLASY2022110053.

Keywords: breast cancer, physical exercise, systematic review, meta-analysis, quality of life

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is women’s most prevalent diagnosed malignancy, representing the most common cause of cancer-related death worldwide (1). Indeed, BC was responsible for around 16% of worldwide cancer deaths in women in 2020, and by 2040 the incidence is expected to increase by more than 46% (corresponding to one million deaths per year) (2–4). Although a significant increase in the incidence of BC has been detected in recent decades, the mortality rate follows an inverse trend, mainly due to the adoption of preventive measures, early screening, and advances in anticancer therapies (4).

Despite the remarkable progress in BC clinical management, the journey of BC patients after curative treatment can be hampered by chronic issues such as reduced health-related quality of life (HRQoL), reduced physical fitness and body composition alterations (5–7).

The HRQoL of the survivors is affected by treatment-related side effects that impair psychosocial and physiological outcomes (8–10). Each therapeutic approach has specific adverse effects that may compromise the HRQoL, namely surgery (radical or partial mastectomy, with or without reconstruction, with or without removal of lymph nodes), radiotherapy and several modalities of systemic treatment, such as chemotherapy, hormone therapies and other target therapies (11). Evidence emphasises the benefits of physical exercise (PE) on the HRQoL of BC survivors. Indeed, prescribing PE twice or thrice a week improves patients’ HRQoL and health status (12, 13). However, the level of evidence is still low to moderate on this topic (6).

Two components of physical fitness are cardiorespiratory fitness and muscle strength. Cardiorespiratory fitness, measured as maximal oxygen consumption (VO2 max), is a good measure of the impairment caused by cardiovascular disease. It has also been shown to be lower in BC survivors compared with healthy women, and this reduction is most pronounced after post-adjuvant treatment, which is related to multiple factors (14). BC survivors are typically characterised as possessing risk factors for cardiovascular diseases and an inappropriate lifestyle, including sedentarism (15–17). In addition, one of the significant challenges in clinical practice is cardiotoxicity (17, 18), which is mainly associated with exposure to BC traditional cytotoxic therapies, such as anthracyclines and anti-human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) therapies (19, 20). PE is an essential component of cardiac rehabilitation for adults with cardiovascular diseases. Moreover, observational studies also indicate that PE reduces the risk of subsequent chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular ones (21). Still, there is insufficient evidence of knowledge on the PE effect on cardiac outcomes of BC survivors.

BC survivors suffer from fatigue in 90% of cases, not only during chemotherapy (22) but over a period that may endure for several years (23). Importantly, cancer-related fatigue often elicits a vicious circle of fatigue-induced reductions in PE, causing a significant reduction in muscle mass and muscle strength (including upper and lower limbs) (24). Isometric handgrip maximal strength can be used as an indicator of overall muscle strength, and low values are related to increased all-cause and cancer mortality, including in BC (25, 26). Recent meta-analyses confirmed the effectiveness of exercise in reducing cancer-related fatigue during and after treatment and improving lower body strength, upper body strength, and lean mass during chemotherapy and radiotherapy in patients with cancer (27, 28). A randomised controlled trial (RCT) also showed that resistance training improves upper and lower body maximal muscle strength in older postmenopausal BC survivors, although improvements were not extended to handgrip strength (29).

The journey of most BC survivors is characterised by increases in body weight and waist circumference concerning several factors, such as sedentarism (30–33), emotional stress, mainly depression and anxiety (34, 35), and premature menopause (36). In most BC survivors whose weight is increased after BC diagnosis, the risk of recurrence and death from BC is significantly higher than in normal-weight women (37, 38). Therefore, regular PE can significantly assist in controlling body weight and has already been shown to reduce the risk of BC (39).

Although there are various systematic reviews and meta-analyses on the effect of PE in BC patients on several different outcomes, none focused explicitly on HRQoL, physical fitness and body composition. This study aims to provide an overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses on the effect of PE in BC patients after curative treatment on HRQoL, physical fitness (cardiorespiratory fitness and isometric handgrip maximal strength) and body composition (body weight and waist circumference).

Materials and methods

The present overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (40, 41) and was registered in INPLASY (identifier INPLASY2022110053 and DOI number 10.37766/inplasy2022.11.0053).

Search strategy

A systematic literature search was conducted in PubMed and Cochrane databases from January 2010 to October 2022. The systematic search used the following keywords: (breast cancer), (effectiveness OR efficacy OR effective*), (Exercise OR Physical Activity OR Strength Training OR Strength Exercise OR Resistance Training OR Resistance Exercise OR Weight Training OR Weight Exercise OR Aerobic Training OR Aerobic Exercise OR Endurance Training OR Endurance Exercise OR Combined Training OR Combined Exercise), “Meta-Analysis”, and “Systematic Review”. The search strategy has been included as Supplementary Information .

Eligibility criteria and study selection

For this systematic analysis, were included only systematic reviews and meta-analyses described in full-length articles in English with clinical observations of humans, with a clearly defined clinical question, details of inclusion and exclusion criteria, details of searched databases and relevant search strategies, and a summary of results, per group, for at least one of the desired outcomes. Table 1 reports the inclusion criteria of the study Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcomes, and Settings (PICOS). Eligibility screening was performed through two separate steps: a) titles and abstracts screening and b) full texts screening, and by three independent persons. Each study title and/or full text was screened by two independent reviewers, and discrepancies were excluded. All the retrieved articles were used independently of their outcome (positive, negative, or neutral impact of the physical exercise programs on health-related quality of life, physical fitness, and body composition of breast cancer survivors).

Table 1.

Study inclusion criteria, defined by PICOS.

| PICOS Component | Description |

|---|---|

| Population | Adults (age >18y, male or female) breast cancer survivors who have concluded curative treatment (surgery and/or radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy) at least 1 month before the intervention. They could be on hormone therapy (any type) and/or anti-HER2 drugs |

| Intervention | Individual PE interventions or in groups, supervised or unsupervised/home-based (including PE that could be initially taught by an exercise professional, or involve periodical/ongoing supervision), and examining different modes of exercise (aerobic exercise, resistance exercise, and combined exercise) |

| Comparator | No intervention or standard care |

| Outcomes | HRQoL (measured by validated questionnaires); cardiorespiratory fitness (measured by exercise stress test); isometric handgrip maximal strength (assessed by dynamometry); body composition (body weight, BMI and/or waist circumference) |

| Setting | Systematic reviews and meta-analyses |

BMI, body mass index; HRQoL, health-related quality of life; PE, physical exercise.

Data extraction

Two independent reviewers extracted the relevant data from the included studies using a preformatted data extraction sheet. The extracted data included: a) baseline characteristics of the population; b) baseline characteristics of the study as design, sample size, procedure evaluation and used comparators; c) assessed outcomes; d) meta-analyses results; and e) conclusions of the study.

Risk of bias assessment

Included systematic reviews were assessed by two researchers for risk of bias using the Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews v2 (AMSTAR-2) (42). Disagreements in the scoring were solved through discussion and consensus. The following seven AMSTAR-2 domains were considered critical: item 2: review methods established before conducting the review; item 4: comprehensive literature search; item 6: data extraction in duplicate; item 9: risk of bias satisfactorily assessed; item 11: appropriate methods for statistically combining results; item 13: risk of bias considered when interpreting/discussing review results; and item 15: quantitative synthesis – adequate investigation of publication bias (slight study bias) and discussion. An overall rating of confidence in the results of each review, of high, moderate, low, or critically low, was given. This depended on the flaws in the above critical domains or other weaknesses within the systematic review. The quality of the preliminary randomised clinical trials (RCTs), as judged by the authors of the included systematic reviews, was considered, particularly random sequence generation, allocation concealment, and attrition bias.

Results

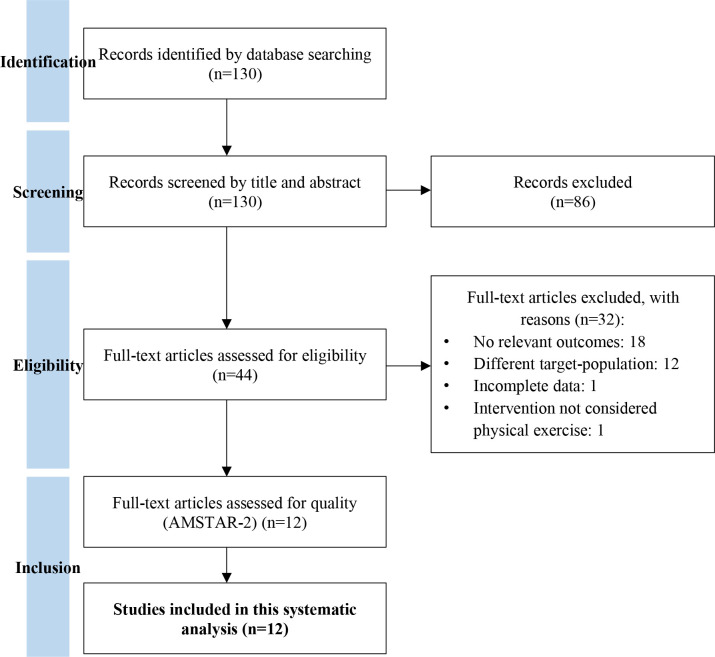

The literature search on PubMed and Cochrane databases yielded 130 studies meeting the search criterion, with 12 studies included in the final version ( Figure 1 , Table 2 ). During the initial screening, 86 records were excluded based on title and abstract. During the second phase of the selection process of the remaining 44 reports, 32 records were excluded because they were not eligible for this study due to not having relevant outcomes (18 reports), having a different target population (12 reports), having incomplete data (1 reports) or for having an intervention not considered PE (1 report). The remaining 12 articles were subjected to quality assessment by AMSTAR-2 (42), considering seven critical domains ( Table 3 ) and included in this systematic analysis. The methodological quality and the overall quality of the studies were low (1 study), moderate (6 studies) and high (5 studies).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart of study selection (41).

Table 2.

Included systematic reviews and meta-analyses methodology and results.

| Study | Objectives & Population | Procedure under evaluation (N)/Comparator(s)/Type and number of studies | Primary outcomes | Meta-Analysis: results, comparison values, and significance | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boing, 2020 (43) |

Investigate PE effect on physical outcomes in BC women receiving any modality of hormone therapy. | Effect of PE on physical outcomes (N=368)/ PE vs usual care; Unsupervised PE vs supervised PE/ 3 RCTs; 2 single-arm pilot studies. |

Cardiorespiratory fitness (VO2max), muscle strength, pain, body fat percentage, bone mineral density. | Cardiorespiratory fitness: SMD = 0.37; p=0.005. Grip strength: SMD = 0.298; p=0.091. |

Three of the five trials demonstrated significant effects separately in improving VO2max. This trend was reflected in the meta-analysis. |

| Abdin, 2019 (44) |

Evaluate PE and specifically consider the effects of different types of exercise and intervention (group vs individual) in adult patients with BC (invasive and in situ carcinoma). | Intervention aiming to increase PE (N=2208)/ Different types of PE interventions/ 17 RCTs. |

Self-reported levels of PE, adherence, cardiorespiratory fitness, QoL, BMI, weight, and fatigue. | Meta-analysis was not performed (due to population heterogeneity, intervention components, outcome measurements, and duration of interventions). | Individual and group interventions have positive outcomes, but some indicators highlight more benefits in group interventions. It was impossible to conclude whether there are differences in outcomes depending on the type of PE. It remains apparent that the lack of clarity of reporting and theory in intervention design is a problem. |

| Hong, 2019 (45) |

Examine PE effect on HRQoL, social function, and physical function; explore the most effective characteristics of PE (type, frequency, duration, time, and total exercise time); and determine optimal PE time for HRQoL improvement in adults diagnosed with BC. | PE intervention (aerobic, resistance, combined, yoga, and Qigong) (N= 1892 in the systematic review; N=1205 [exercise 602 and control 603])/ Not submitted to PE intervention/ 26 RCTs in the systematic review and 18 in the meta-analysis. |

QoL (general, global health, and overall QoL), SF, and PF. | Change in HRQoL: extremely (p = 0.0004) influenced by exercise intervention, with heterogeneity: Tau2 = 0.10; Chi2 = 43.68; df = 17; and I2 = 61%. “Time of session”: significantly (p = 0.041) correlated with an improved QoL. SF outcome: extremely favoured exercise, citing the SMD = 0.20, I2 = 16%, and 95% CI: 0.08 to 0.32. PF outcome: improved by exercise interventions (p < 0.00001); pooled SMD of the enhanced PF was 0.32 (0.20 to 0.44), at a 95% CI, and where the I2 was 32% after the interventions. |

PE interventions (of any type) improve HRQoL and social and physical function in women BC survivors. However, HRQoL improvement was associated with session duration (>45 min). |

| Soares Falcetta, 2018 (46) |

Disclose PE effect (with or without dietary interventions) on body composition, HRQoL, and survival in women after early-stage (I–III) BC treatment. | Studies that performed the intervention after the end of adjuvant treatment (excluding hormone therapy) were included; studies that applied the intervention after 5 years from the diagnosis were excluded. From a total of 60 studies included, only 19 RCTs with a structured or individualised PE program (N=1613; PE 835 and control 778) were assessed. |

Overall survival and disease-free survival (5 years after treatment or until the maximum follow-up study). Secondary endpoints: weight loss (kg), BMI (kg/m2), waist-hip ratio, percentage of body fat (%), and HRQoL. AEs, such as PE-induced lesions, were also considered. |

Weight reduction: mean diff -0.27 (-1.16;0.63); n=835 (experimental group) and n=787 (control group); BMI reduction: -0.36 (-0.83;0.11); n=797 (experimental group) and n=752 (control group); HRQoL (general) for different scales: SMD=0.76 (0.19-1.34); n= 421 (experimental group) and n=388 (control group). |

Heterogeneous types of intervention showed significant effects on anthropometric measures and HRQoL. Only one study had mortality as an outcome, showing PE as a protective intervention. Despite these findings, publication bias and poor methodological quality were presented. PE should be advised for BC survivors since it has no AEs and can improve anthropometric measures and QoL. |

| Singh, 2018 (47) |

Evaluate PE safety, feasibility, and effect among women with stage II+ BC. | Randomised, controlled PE trials were included, involving at least 50% of women diagnosed with stage II+ BC. From the 61 trials included in this systematic review, 60 RCTs evaluated PE safety and the risk of AEs. |

The risk of bias was assessed, and AEs severity was classified using the Common Terminology Criteria. Feasibility was evaluated by computing median (range) recruitment, withdrawal, and adherence rates. Meta-analyses were performed to evaluate PE safety and effects on health outcomes only. The influence of intervention characteristics (mode, supervision, duration, and timing) on PE outcomes were also explored. | Significant effects of PE on HRQoL, fitness, fatigue, strength, anxiety, depression, BMI, and waist circumference compared with usual care (stand mean diff range: 0.17-0.77, p<0.05). There were no differences in AEs between PE and usual care (risk difference: <0.01 ([95% CI: -0.01, 0.01], p=0.38). The median recruitment rate was 56% (1%-96%), the withdrawal rate was 10% (0%-41%), and the adherence rate was 82% (44%-99%). Safety and feasibility outcomes were similar, irrespective of PE mode, supervision, duration, or timing. |

The findings support PE safety, feasibility, and effects for those with stage II+ BC, suggesting that national and international exercise guidelines appear generalisable to women with local, regional, and distant BC. |

| Lahart, 2018 (6) |

Assess the effects of PE interventions after adjuvant therapy for women with BC. | Randomised and quasi-randomised trials comparing PE interventions vs control (e.g., usual or standard care, no PE, no exercise, attention control, placebo) after adjuvant therapy (i.e., after completion of chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy, but not hormone therapy) in women with BC. The study included 63 trials that randomised 5761 women to a physical activity intervention (n = 3239) or a control (n = 2524). |

Outcomes of HRQoL, PE, and cardiorespiratory fitness. The overall effect size with 95% CIs was calculated for each outcome; GRADE was used to assess the quality of evidence for the most critical outcomes. GRADE working group grades of evidence: High quality: Further research is unlikely to change the confidence in the effect estimate. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to impact the confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to impact the confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: There is high uncertainty about the estimate. |

Changes from baseline to the end of intervention after a median follow-up of 12 weeks: 1 – HRQoL: 14 studies were assessed, comprising 1459 participants. The illustrative comparative risk (95% CI) was 0.78 standard deviations higher (0.39 to 1.17 higher) in the physical activity group and -2.40 to 1.25 standard deviation units in the control group. Quality of evidence (GRADE): low. 2 – Emotional function/mental health: 15 studies were assessed, comprising 1579 participants. The illustrative comparative risk (95% CI) was 0.31 standard deviations higher (0.09 to 0.53 higher) in the physical activity group and -0.39 to 3.47 standard deviation units in the control group. Quality of evidence (GRADE): low. 3 – Perceived physical function: 13 studies were assessed, comprising 1433 participants. The illustrative comparative risk (95% CI) was 0.60 standard deviations higher (0.23 to 0.97 higher) in the physical activity group and -1.34 to 1.66 standard deviation units in the control group. Quality of evidence (GRADE): moderate. 4 – Anxiety change: 4 studies were assessed, comprising 235 participants. The illustrative comparative risk (95% CI) was 0.37 standard deviations lower (0.63 to 0.12 lower) in the physical activity group and -1.44 to 0.73 standard deviation units in the control group. Quality of evidence (GRADE): low. 5 – Depression change: 7 studies were assessed, comprising 816 participants. The illustrative comparative risk (95% CI) was 0.34 standard deviations lower (0.63 to 0.05 lower) in the physical activity group and -1.51 to 1.83 standard deviation units in the control group. Quality of evidence (GRADE): low. 6 – Fatigue change: 13 studies were assessed, comprising 1289 participants. The illustrative comparative risk (95% CI) was 0.30 standard deviations lower (0.61 to 0 lower) in the physical activity group and -1.81 to 1.83 standard deviation units in the control group. Quality of evidence (GRADE): low. 7 – Cardiorespiratory change: 9 studies were assessed, comprising 863 participants. The illustrative comparative risk (95% CI) was 0.83 standard deviations higher (0.40 to 1.27 higher) in the physical activity group and -1.45 to 2.38 standard deviation units in the control group. Quality of evidence (GRADE): very low. |

There were no conclusions regarding BC-related and all-cause mortality or BC recurrence. However, PE interventions may have small-to-moderate beneficial effects on HRQoL, emotional or perceived physical and social function, anxiety, cardiorespiratory fitness, and self-reported and objectively measured physical activity. The positive results reported in the current review must be interpreted cautiously owing to the very low-to-moderate quality of evidence, heterogeneity of interventions and outcome measures, imprecision of some estimates, and risk of bias in many trials. Future studies with a low risk of bias are required to determine the optimal combination of physical activity modes, frequencies, intensities, and durations needed to improve specific outcomes among women who have undergone adjuvant therapy. |

| Zhang, 2019 (48) |

Assess the PE effect on the HRQoL among people with BC. | Effect of PE on HRQoL compared with that of usual care for people with BC. N = 36 RCT (3914 participants) |

PE was categorised into three modes: aerobic, resistance, and a combination of aerobic and resistance. The outcome measure was the QoL. |

Meta-analysis was not performed. This Systematic review revealed that all three PE intervention modes significantly affected the QoL between groups. |

PE is a safe and effective way to improve HRQoL in BC patients. Combined training was associated with a significant improvement in HRQoL. In future research, more high-quality, multicenter trials evaluating the effect of exercise in BC patients are needed. |

| Gebruers, 2019 (49) |

Characterise PE programs and their effects on (1) physical performance outcomes, (2) experienced fatigue, and (3) HRQoL in patients during the initial treatment for BC. | N = 28 RCT (2525 participants) | The primary outcome was the PE effect on physical performance, HRQoL, and perceived fatigue. | Meta-analysis was not performed. | Most training interventions provided an improvement in physical performance and a decrease in perceived fatigue. HRQoL was the outcome variable least susceptible to improvement. |

| Kannan, 2022 (50) |

Investigate PE effect on QoL and upper quadrant pain in women with PMPS (post-mastectomy pain syndrome) | PE intervention (aerobic exercise, resistance training, aqua fitness) No PE intervention N=10 RCT (4 RCT with 451 patients to evaluate PE effect on QoL; 6 RCT with 406 patients to evaluate PE effect on upper quadrant pain) |

QoL, upper quadrant pain | Effect of PE on QoL: a statistically significant effect of the intervention on general [SMD 0.87 (95%CI: 0.36-1.37); p = 0.001], physical [SMD 0.34 (95%CI: 0.01-0.66); p = 0.044] and mental health components [SMD 0.27 (95%CI: 0.03-0.51); p = 0.027], when compared to the control condition. Effect of PE on upper quadrant pain: more significant reduction in pain severity in the intervention group than the control group [SMD -1.00 (95%CI: -1.48 to -0.52); p < 0.001) |

Meta-analysis revealed statistically significant effects of exercise compared to control in improving overall QoL and pain. Exercise is a low-cost and safe intervention and could, therefore, be considered an essential component of QoL and pain management among women with PMPS |

| Salam, 2022 (51) |

Evaluate the effects of post-diagnosis PE on depression, physical functioning, and mortality in breast cancer survivors | PE intervention (home-based/unsupervised; supervised aerobic resistance, strengthening and core exercises, yoga, gymnastics) No physical activity (i.e., a regular care group or non-physical intervention) N=26 RCT (13 studies for the effect of PE on depression, 8 for the effect of PE on physical functioning/QoL, 7 for the effect of PE on mortality; some studies were investigating both depression, physical functioning, and mortality, therefore, entered twice for the statistical analysis) |

Depression (measurements with CES-D, HADS, BDI, POMS and Greene Climacteric Scale), physical functioning/QoL (SF-36 and EORTC QLQ-C30 subscales), mortality | Effect of PE on depression (N= 689 participants in the PE group vs 480 participants in the control group): differences in the depression scores were statistically significant compared with controls (SMD -0.24, 95% CI -0.43 to -0.05, P = 0.012), with moderate statistical heterogeneity identified (P = 0.011, I2 = 54%) Effect of PE on physical functioning/QoL (N= 689 participants in the PE group vs 480 participants in the control group): statistically significant differences between the PE and control groups (SMD 0.37, 95% CI 0.03-0.72, P = 0.032), with moderate statistical heterogeneity (P = 0.01, I2 = 62%) Effect of PE on mortality (N=15,853 participants): the overall effect of physical activity was statistically significant (HR 0.63, 95% CI 0.55-0.71, p < 0.00001), with no evidence of statistical heterogeneity (p = 0.27, I2 = 15%). |

There is sufficient evidence to support the effectiveness of PE and physical activity in addressing cancer-related health outcomes, including fatigue, quality of life, physical function, anxiety, and depressive symptoms |

| Wang, 2022 (52) |

Evaluate the benefits of aquatic physical therapy as a rehabilitation strategy for women with BC |

Aquatic exercise (8 weeks) Usual care and all forms of intervention except aquatic exercise N=2 RCT (52 patients on PE-group vs 51 patients in the control group) |

Fatigue, waist circumference | Effect of aquatic PE on fatigue: statistically significant differences among groups (MD = -2.14, 95% CI: -2.82, -1.45, p<0.01), with 0% of heterogeneity. Effect of aquatic PE on waist circumference: no statistically significant differences between groups (MD = -3.49, 95% CI: -11.56, 4.58, p = 0.4) |

Aquatic physical therapy significantly relieved fatigue. However, compared with usual care, aquatic physical therapy did not improve physical index (waist circumference), which might be due to the short intervention time, which is not enough to produce a significant statistical difference |

| Ye, 2022 (53) |

Investigate the effects of Baduanjin exercise on the QoL and psychological status of postoperative patients with BC |

Baduanjin exercise No PE (i.e., a regular care group or non-physical intervention) N=7 RCT (450 participants) |

QoL (measurements with FACT-B and SF-36 scores), anxiety (measurements with SAS and SDS scales) | Effect of Baduanjin on QoL (FACT-B): Exercise-group with higher values of QoL than the control group (WMD with 95% CI = 5.70 (3.11, 8.29), P < 0.0001) Effect of Baduanjin on QoL (SF-36): PE improved QOL in the dimensions of role-physical (WMD with 95% CI = 11.49 [8.86, 14.13], P < 0.00001, I2 = 0%) and vitality (WMD with 95% CI = 8.58 [5.60, 11.56], P < 0.00001, I2 = 0%), but no statistical difference was found for physical functioning, bodily pain, social functioning, general health, and mental health (physical functioning: WMD with 95% CI = 0.97 (−1.57, 3.50), P = 0.45, I2 = 0%; bodily pain: WMD with 95% CI = 0.81 (−1.97, 3.58), P = 0.57, I2 = 0%; social functioning: WMD with 95% CI = −0.50 (−16.91, 15.90), P = 0.95, I2 = 62%; general health: WMD with 95% CI = 2.97 (−0.05, 5.99), P = 0.05, I2 = 0%; role-mental: WMD with 95% CI = 3.03 (−3.18, 9.24), P = 0.34, I2 = 5%; mental health: WMD with 95% CI = 7.47 (−1.01, 15.94), P = 0.08, I2 = 75%). Effect of Baduanjin on anxiety: depression scores for the exercise group were lower than those of the control group (WMD with 95% CI = -4.45(-5.62, -3.28), P < 0.00001). |

Results showed that Baduanjin interventions improved the QOL of postoperative patients with BC compared to those without Baduanjin. Subgroup analysis found that Baduanjin exercise improved physical function and vitality in postoperative patients with BC. In terms of anxiety and depression relief, Baduanjin exercise also had a significant effect. |

BC, Breast cancer; PE, Physical exercise; AEs, Adverse events; BMI, Body Mass Index; SMD, standardized mean difference; HRQoL, Health-Related Quality of life; RCT, randomized clinical trials; SF, social function; PF, physical function; df, degrees of freedom; HRQoL, Health-related quality of life.

Table 3.

Quality assessment (AMSTAR-2) of the included systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

| AMSTAR 2 criteria* | Boing, 2020 | Abdin, 2019 | Hong,2019 | Falcetta,2018 | Singh,2018 | Lahart,2018 | Zhang,2019 | Gebruers,2019 | Kannan, 2022 | Salam, 2022 | Ye,2022 | Wang, 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item 2 | Y | Y | PY | Y | PY | Y | PY | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y |

| Item 4 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Item 6 | Y | Y | ? | ? | PY | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Item 9 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Item 11 | Y | NMC | ? | Y | Y | Y | NMC | NMC | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Item 13 | Y | Y | Y | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | Y | PY | Y | Y |

| Item 15 | PY | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | PY | Y | Y | PY | Y | Y |

N, no; NMC, no meta-analysis conducted; PY, partial yes; Y, yes.

*AMSTAR-2 Criteria (42):

Item 2: Did the review report explicitly state that the review methods were established before conducting the review, and did the report justify any significant deviations from the protocol?

Item 4: Did the review authors use a comprehensive literature search strategy?

Item 6: Did the review authors perform data extraction in duplicate?

Item 9: Did the review authors use a satisfactory technique for assessing the risk of bias (RoB) in individual studies included in the review?

Item 11: If meta-analysis was justified, did the review authors use appropriate methods for statistical.

Item 13: Did the authors consider RoB in individual studies when interpreting/discussing the review results?

Item 15: If they performed quantitative synthesis, did the review authors carry out an adequate investigation of publication bias (slight study bias) and discuss its likely impact on the results of the review?

Description of included studies

The studies selected for this review consisted of 9 systematic reviews/meta-analyses, 1 meta-analysis/meta-regression, and 2 systematic reviews. Of the 12 included studies, 3 were conducted across Europe (2 from the United Kingdom and 1 from Belgium), 2 in South America (Brazil), 4 in Asia (5 from China and 1 from Saudi Arabia), and 1 in Australia. Overall, the number of databases used in each review ranged from 4 to 10, the number of studies included varied from 5 to 63, and the number of participants was from 214 to 5761.

Outcomes analysis

The detailed summary and primary outcomes of the eligible studies are presented in Table 2 . Overall, the studies herein analysed depicted a positive and significant effect of different PE interventions on the health outcomes of BC survivors, namely on HRQoL (10 studies; 83.3%), improved cardiorespiratory fitness (3 studies; 25%), reducing bodyweight (3 studies; 25%) and waist circumference (4 studies; 33.3%).

Health-related quality of life

A meta-analysis published by Hong et al. evaluated 18 trials to assess the effect of PE intervention on the HRQoL of BC survivors and showed that the HRQoL was significantly improved by PE intervention (45). The authors found no relationship between HRQoL and PE characteristics (type, frequency, and total time) except for the exercise session duration. Specifically, the trials with “time of session” data were categorised into 3 subgroups, namely, shorter time (≤ 45 min, 7 trials), medium time (> 45 to ≤ 60 min, 7 trials), and longer time (> 60 to 90 min, 4 trials), and subgroup analysis was performed. Results revealed that the medium and longer-time sessions enhanced the HRQoL of BC patients, the latter further positively associated with increased QoL, as the patients engaged in longer-time sessions achieved the most significant improvement (>60 to 90 min, p = 0.005). In another study that also evaluated HRQoL, Soares-Falcetta et al. analysed 23 studies and reported a positive effect of PE on the improvement of BC patient HRQoL (p < 0.01) (46). The authors also revealed that heterogeneous types of physical intervention benefit the HRQoL in women after early-stage (I-III) BC treatment. Importantly, it was impossible to identify the best one due to the heterogeneity of the PE interventions among the analysed studies, varying from exercise counselling to structured and supervised exercise programs. Hence, the authors compared PE as a single group (46).

The meta-analysis by Singh et al. analysed 40 studies to compare PE (aerobic, resistance, or other - not specified as aerobic or resistance) with usual care and found a moderate pro-exercise effect on HRQoL (p<0.01) (47). Specifically, supervised PE had a more significant beneficial effect on the HRQoL of the participants (p < 0.01), compared to unsupervised interventions, and when the PE involved more than one exercise mode, compared with only one mode.

HRQoL was assessed in 22 studies in Lahart et al. meta-analysis, in which PE induced a small-to-moderate significant improvement in HRQoL compared to the control group (6). The results also indicated that this improvement did not persist for three months or longer after the intervention, which had an overall duration ranging from 4 to 24 months, with most lasting 8 or 12 weeks (37 of 63 RCTs). In a recent systematic review by Gebruers et al., 28 RTCs, comprising 2,525 participants, were analysed (49). Evidence showed that PE intervention improved HRQoL and decreased fatigue in BC survivors (49). In the systematic revision by Zhang et al., the effect of different types of PE on the HRQoL was investigated, particularly aerobic, resistance, and a combination of both (48). The authors concluded that all types of PE were effective in fostering HRQoL of BC survivors, though combined training was associated with a significantly higher improvement. The results suggest that supervised PE enhances attendance rates, motivation, and the overall HRQoL. Likewise, Abdin and colleagues revised 17 RCTs and concluded that both individual and mostly group interventions promote favourable health outcomes and overall HRQoL (44).

The meta-analysis by Kannan et al. also demonstrated a positive effect of different PE interventions on the HRQoL of female survivors of BC with post-mastectomy pain, a common condition among BC survivors (50). For that, the authors evaluated 4 RCTs, comprising 406 women under aerobic exercise (treadmill at an intensity of 60%–80% heart rate maximum), resistance training (exercises for the large muscles of the upper and lower limbs progressing from two sets of 12 repetitions at 50–60% one repetition maximum (RM) to three sets of 10 repetitions at 60–80% 1RM, over 2 years) or aquafitness, in sessions ranging from 30 to 60 min, performed two to five times per week for a duration of 3 months to 2 years. The pooled evidence demonstrated a statistically significant effect (p = 0.001) of these PE interventions on HRQoL.

Similarly, a pool of 8 studies was evaluated by Salam and colleagues (51), combining a total of 241 BC survivors under prescribed PE, ranging from moderate-to-vigorous intensity exercises (e.g. yoga, walking, cycling, tai chi chuan and cycling). When compared to the control group (177 participants under no PE), active participants, in a frequency ranging from once to 6 times/week in 15-to-75 min sessions, displayed significantly better HRQoL (p = 0.032) (51).

Lastly, Baduanjin, a Chinese series of 8 movements combing breathing and body movement, was also demonstrated to improve the psychological status of postoperative patients with BC (53). For that, the authors pooled 7 RCTs, including 450 postoperative BC patients undergoing 30 min-sessions of Baduanjin 2 to 5 times/week, and evaluated the impact on QoL. Both FACT-B (p < 0.0001) and SF-36 (p < 0.00001) scores revealed a significant increase with Baduanjin exercise (53).

Cardiorespiratory fitness

The study of Boing et al. analysed the effect of PE on BC survivors receiving hormone therapy, tamoxifen, and aromatase inhibitors (43). This study analysed five RCTs on cardiorespiratory fitness and concluded that three of the five trials separately demonstrated significant effects in improving VO2 max, as shown in the meta-analysis (p < 0.01). The Lahart et al. study included 23 RCTs comprising 1265 women and reported that PE significantly increased cardiorespiratory fitness (6). This study also demonstrated that the significant improvement in cardiorespiratory fitness values at post-intervention follow-up was maintained for PE compared with the control in the subgroup analysis only for postmenopausal women, for both aerobic exercise and combined aerobic and resistance exercise interventions (SMD 0.44, 95% CI 0.30 to 0.58, 23 studies, 1265 women, moderate-quality evidence). The analysis performed by Abdin et al. revealed that both individual, but mostly group, interventions had a beneficial effect on health outcomes concerning fatigue and cardiorespiratory fitness (44).

Upper body strength

Singh et al. assessed the effect of PE on upper-body strength, and the analysis revealed a moderate effect in favour of exercise, particularly after resistance PE (SMD=0.68 [95%CI: 0.05, 0.85]; p<0.01) rather than aerobic or combined PE (47). Zhang et al. also concluded that PE prescription incorporating more than 150 min of high-intensity training per week significantly improved upper body strength and was associated with a low incidence of adverse events in BC patients (48). Grip strength, defined as the strength that muscles apply against resistance at maximum effort during handgrip, was also assessed in the study by Boing et al. (43). This test is commonly used to verify muscular strength and correlated health in BC survivors, and it showed to be marginally improved in the PE group compared to the control group, though not significantly (43).

Body composition

Soares-Falcetta et al. analysed 54 studies addressing the effect of PE, whether by supervision or by structured programs, including aerobic and resistance training, on the reduction of weight and BMI (46). The follow-up ranged from 1 to 101 months, and the duration of the intervention occurred from 4 weeks to 24 months. PE was associated with weight reduction (p=0.02) and lower BMI (p<0.01) (46). In addition, the evidence disclosed by the meta-analysis by Singh et al., in which 8 studies compared PE with usual care, suggests a moderated benefit for waist circumference reduction (SMD=0.22, p=0.03) (47). On the other hand, a sub-analysis of 15 trials showed no significant difference in weight reduction (SMD=0.08, p=0.22) (47), whereas a sub-analysis of 13 trials revealed a slight, though not significant, benefit in BMI (SMD=0.11, p=0.11) (47). Regarding body fat percentage, a meta-analysis by Boing et al., which included 4 RCTs, also reported an overall reduction in body fat after the intervention; however, this reduction was not significant (43).

Finally, aquatic PE was also investigated for a potential effect on the body composition of BC survivors (52), as opposed to conventional land-based exercise. This form of exercise involves a variety of modalities, including aerobic, stretching, resistance, flexibility and stability training, which by using the unique properties of water (buoyancy, resistance, flow, and turbulence), allows people to perform exercises that they cannot do on land (54). A total of 2 RCTs, with 53 participants on aquatic exercise (8 weeks duration of the interventional program) compared to 51 control participants under usual care, were examined for waist circumference. Meta-analysis failed to show significant differences in waist circumference between groups (p = 0.04), which can be due to the low number of participants and the short intervention time, which was insufficient to produce a significant statistical difference. Thus, more studies are required to fully assess aquation PE’s impact on the health outcomes of BC survivors.

Discussion

In the present review, twelve systematic revisions and meta-analyses were explored to assess the effectiveness of PE in the QoL of BC survivors. The selected studies evaluated many RCTs to disclose how distinct PE methodologies could potentially promote a healthier life, characterised by reduced stress, fatigue, depression, anxiety and an increase in cardiorespiratory fitness. Specifically, the studies examined different modes of exercise (including aerobic exercise, resistance exercise, and combined exercise), types of intervention (individual or group, and supervised or unsupervised/home-based), frequency, and duration of each program training session.

According to the analysis by Zhang and colleagues, the outcome suggests that in almost 90% of the studies, aerobic exercise significantly benefits the QoL in patients with BC compared with the control group (48). Notably, 100% of the studies analysed reported a significant effect of combined training on the QoL in patients with BC compared with the control group (48). The same pattern of benefit in BC patients was observed by Singh et al., as the authors concluded that PE led to favourable effects irrespective of intervention characteristics. Still, the effect’s magnitude depended on the PE mode, degree of supervision, timing (during vs following treatment), and duration of the intervention (47). In another study, the same reflection was shared as the authors stated that not only QoL but also social and physical functions in women with BC were improved if longer training sessions occurred (45).

Overall, all the considered reports disclosed a valuable and significant influence of PE on QoL, and although it is unclear whether the type of program or its precise duration influences the results, more prolonged, in-group, and supervised PE sessions seem to have a higher benefit. Practising exercise has been shown to foster the maintenance of a healthy weight and lifestyle, characterised by improved cardiorespiratory fitness and decreased body weight and BMI, fatigue, depression, and anxiety (55). Furthermore, it can also prevent other chronic diseases for which this population is particularly vulnerable (56). Remarkably, PE prescription is more commonly performed to overcome treatment-induced adverse effects and promote general well-being. In numerous trials in which exercise was included, the results indicate that clinical outcomes are advantageous (57), contradicting previous theories whereby cancer patients were advised to rest and avoid physically challenging activities that could promote additional load and fatigue rather than alleviating cancer-related fatigue (58). Aquatic exercise also arises as a PE intervention to be further researched for the prescription to BC survivors due to its therapeutic potential already used on conditions such as fibromyalgia (59) and stroke (56, 60). Considering this new evidence that PE is vital for the long-term management of QoL (61), the interests and preferences of the patients should not be neglected, and any prescription should consider their physical and psychosocial needs. According to some of the studies considered herein, better outcomes were obtained when BC participants were encouraged to train with other survivors or supervised exercise programs (44). Notably, this can potentiate personal interaction with others, fostering the establishment of relationships, decreasing the sense of isolation and social stigma, and improving self-esteem. Overall, PE contributes to lowering withdrawal rates, boosting motivation and adherence, and the long-term commitment to PE, potentiating an improvement in body composition and QoL. Accordingly, despite the mode, frequency, or intervention of the PE program, it has been shown to be quite effective in reducing body weight, fat percentage, and waist circumference, contributing to health outcomes (49). Resistance or intense PE was the most effective in promoting increased upper body strength (48).

Notably, adverse events derived from PE practice were rarely reported, typically mild and representing acute and normal physiological adaptations to exercise. Nonetheless, the authors acknowledge that some studies do not report adverse events. This highlights the need for the standardised recording of adverse events to be incorporated into the design of RCTs, as it is critical to explore the adverse effects of PE on BC patients in future research.

Recent shreds of evidence have also unveiled several biomarkers (e.g., inflammatory molecules, mitochondria modifications) (62, 63) with monitoring potential to improve the clinical rehabilitative management of BC patients. Interestingly, these actionable biomarkers were shown to be modulated by PE (64), opening the possibility of targeted control of the therapeutic effect of PE on BC survivors. Future studies should also envisage deciphering the biological mechanisms by which PE potentiates an improvement of the QoL in BC patients. It would be of great value to disclose whether this enhancement is a consequence of an improved “state of mind” (due to reduction of stress, anxiety, and depression) or is dependent on a biochemical pathway that is disease-related, or both in a complementary way, paving the way for the creation of new approaches to boost the QoL of people who survived cancer.

Strengths and limitations of the study

In this systematic analysis, we have followed the PRISMA Statement. Although the effect of PE on different outcomes of BC survivors has been increasingly addressed in the literature, this systematic analysis evaluated data focusing specifically on the outcomes of HRQoL, cardiovascular fitness, and increase of upper-body strength and body composition and also includes more recent publications than other published ones. Overall, we showed strong evidence that PE has a potentially positive effect on the HRQoL and health status of BC survivors. These results should instigate the prescription of regular PE programs, after BC diagnosis and survival, by healthcare professionals to enhance survivors’ HRQoL.

Nonetheless, the encouraging results reported herein must be carefully interpreted, as, during the execution of this systematic revision, the authors encountered some difficulties as the multitude of literature on these thematic reports presents highly diverse content, not enabling, for instance, the execution of a meta-analysis. The heterogeneity of interventions and outcome measures, the different comparisons performed, the low to moderate quality of evidence (GRADE scale), the risk of bias in many trials, and the overall lack of long‐term intervention effects do not enable us to draw solid conclusions. Notably, the elaboration of future studies with low-risk bias, improved clarity to describe interventions, and a comparison of data considering the outcomes of PE, is urgently needed. This information will be critical to determine the optimal combination of PE modes, frequencies, intensities, and durations needed to improve specific outcomes among patients who survived BC.

Conclusion

This rigorous and objective systematic revision suggests that PE is an effective strategy that promotes a positive effect on QoL, cardiorespiratory fitness, and physical functions, including the decrease in BMI and weight of BC survivors. Nonetheless, it should be underpinned that the meta-analyses included show relatively moderate effects, often unsustainable in the long term, and the heterogeneity of each assessment detracts from the power of the evidence, thus requiring these conclusions to be perceived cautiously. Future studies should attempt to disclose the impact of different interventions, frequencies, timings, and adverse events of PE on BC survival outcomes, allowing for refinement of the optimal exercise prescription for each set of patients, aiming to improve the overall QoL.

Data availability statement

The original contributions and search strategy presented in the study are included in the article/ Supplementary Material . Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the manuscript. AJ: conceptualisation, search and trials selection, assessment of the risk of bias, data extraction, and writing of the first draft. IL and PA: search and trials selection, data extraction, and review of the first draft. AC, SV: review of the first draft. AA and LH: conceptualisation and review of the first draft. AM: conceptualisation, search and trials selection, assessment of the risk of bias, data extraction, data synthesis, and writing the first draft. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge AICSO and ONCOMOVE for all the technical and logistic support. They would also like to acknowledge the Evidenze Portugal team, which provided the necessary technical support to conclude this work in record time.

Funding

AICSO provided the publication expenses. LH is supported by UIDB/04501/2020 and UIDP/04501/2020 and MEDISIS (CENTRO-01-0246-FEDER-000018). PA was awarded with a Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology PhD grant (SFRH/BD/143226/2019).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2022.955505/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1. Torre LA, Siegel RL, Ward EM, Jemal A. Global cancer incidence and mortality rates and trends–an update. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev (2016) 25(1):16–27. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ferlay J EM, Lam F, Colombet M, Mery L, Piñeros M, Znaor A, et al. Global cancer observatory: Cancer today. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; (2020). Available at: https://gco.iarc.fr/today. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Arnold M, Morgan E, Rumgay H, Mafra A, Singh D, Laversanne M, et al. Current and future burden of breast cancer: Global statistics for 2020 and 2040. Breast (2022) 66:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2022.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: Globocan estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin (2021) 71(3):209–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Amatya B, Khan F, Galea MP. Optimising post-acute care in breast cancer survivors: A rehabilitation perspective. J Multidiscip Healthc (2017) 10:347–57. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S117362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lahart IM, Metsios GS, Nevill AM, Carmichael AR. Physical activity for women with breast cancer after adjuvant therapy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2018) 1(1):CD011292. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011292.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pedersen B, Delmar C, Lorincz T, Falkmer U, Gronkjaer M. Investigating changes in weight and body composition among women in adjuvant treatment for breast cancer: A scoping review. Cancer Nurs (2019) 42(2):91–105. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Binkley JM, Harris SR, Levangie PK, Pearl M, Guglielmino J, Kraus V, et al. Patient perspectives on breast cancer treatment side effects and the prospective surveillance model for physical rehabilitation for women with breast cancer. Cancer (2012) 118(8 Suppl):2207–16. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McNeely ML, Binkley JM, Pusic AL, Campbell KL, Gabram S, Soballe PW. A prospective model of care for breast cancer rehabilitation: Postoperative and postreconstructive issues. Cancer (2012) 118(8 Suppl):2226–36. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cantarero-Villanueva I, Fernandez-Lao C, Fernandez DEL-PC, Diaz-Rodriguez L, Sanchez-Cantalejo E, Arroyo-Morales M. Associations among musculoskeletal impairments, depression, body image and fatigue in breast cancer survivors within the first year after treatment. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) (2011) 20(5):632–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2011.01245.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Furmaniak AC, Menig M, Markes MH. Exercise for women receiving adjuvant therapy for breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2016) 9:CD005001. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005001.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Campbell A, Mutrie N, White F, McGuire F, Kearney N. A pilot study of a supervised group exercise programme as a rehabilitation treatment for women with breast cancer receiving adjuvant treatment. Eur J Oncol Nurs (2005) 9(1):56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2004.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Duijts SF, Faber MM, Oldenburg HS, van Beurden M, Aaronson NK. Effectiveness of behavioral techniques and physical exercise on psychosocial functioning and health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients and survivors–a meta-analysis. Psychooncology (2011) 20(2):115–26. doi: 10.1002/pon.1728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Peel AB, Thomas SM, Dittus K, Jones LW, Lakoski SG. Cardiorespiratory fitness in breast cancer patients: A call for normative values. J Am Heart Assoc (2014) 3(1):e000432. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jones LW, Haykowsky MJ, Swartz JJ, Douglas PS, Mackey JR. Early breast cancer therapy and cardiovascular injury. J Am Coll Cardiol (2007) 50(15):1435–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.06.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mehta LS, Watson KE, Barac A, Beckie TM, Bittner V, Cruz-Flores S, et al. Cardiovascular disease and breast cancer: Where these entities intersect: A scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation (2018) 137(8):e30–66. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gernaat SAM, Ho PJ, Rijnberg N, Emaus MJ, Baak LM, Hartman M, et al. Risk of death from cardiovascular disease following breast cancer: A systematic review. Breast Cancer Res Treat (2017) 164(3):537–55. doi: 10.1007/s10549-017-4282-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Armenian SH, Lacchetti C, Barac A, Carver J, Constine LS, Denduluri N, et al. Prevention and monitoring of cardiac dysfunction in survivors of adult cancers: American society of clinical oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol (2017) 35(8):893–911. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.5400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zamorano JL, Lancellotti P, Rodriguez Munoz D, Aboyans V, Asteggiano R, Galderisi M, et al. 2016 Esc position paper on cancer treatments and cardiovascular toxicity developed under the auspices of the esc committee for practice guidelines: The task force for cancer treatments and cardiovascular toxicity of the European society of cardiology (Esc). Eur J Heart Fail (2017) 19(1):9–42. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Valachis A, Nilsson C. Cardiac risk in the treatment of breast cancer: Assessment and management. Breast Cancer (Dove Med Press) (2015) 7:21–35. doi: 10.2147/BCTT.S47227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ibrahim EM, Al-Homaidh A. Physical activity and survival after breast cancer diagnosis: Meta-analysis of published studies. Med Oncol (2011) 28(3):753–65. doi: 10.1007/s12032-010-9536-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Whisenant M, Wong B, Mitchell SA, Beck SL, Mooney K. Distinct trajectories of fatigue and sleep disturbance in women receiving chemotherapy for breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum (2017) 44(6):739–50. doi: 10.1188/17.ONF.739-750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jones JM, Olson K, Catton P, Catton CN, Fleshner NE, Krzyzanowska MK, et al. Cancer-related fatigue and associated disability in post-treatment cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv (2016) 10(1):51–61. doi: 10.1007/s11764-015-0450-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mock V, Frangakis C, Davidson NE, Ropka ME, Pickett M, Poniatowski B, et al. Exercise manages fatigue during breast cancer treatment: A randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology (2005) 14(6):464–77. doi: 10.1002/pon.863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhuang CL, Zhang FM, Li W, Wang KH, Xu HX, Song CH, et al. Associations of low handgrip strength with cancer mortality: A multicentre observational study. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle (2020) 11(6):1476–86. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Celis-Morales CA, Welsh P, Lyall DM, Steell L, Petermann F, Anderson J, et al. Associations of grip strength with cardiovascular, respiratory, and cancer outcomes and all cause mortality: Prospective cohort study of half a million uk biobank participants. BMJ (2018) 361:k1651. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k1651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McGovern A, Mahony N, Mockler D, Fleming N. Efficacy of resistance training during adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation therapy in cancer care: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer (2022) 30(5):3701–19. doi: 10.1007/s00520-021-06708-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mustian KM, Alfano CM, Heckler C, Kleckner AS, Kleckner IR, Leach CR, et al. Comparison of pharmaceutical, psychological, and exercise treatments for cancer-related fatigue: A meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol (2017) 3(7):961–8. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.6914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Winters-Stone KM, Dobek J, Bennett JA, Nail LM, Leo MC, Schwartz A. The effect of resistance training on muscle strength and physical function in older, postmenopausal breast cancer survivors: A randomized controlled trial. J Cancer Surviv (2012) 6(2):189–99. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0210-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Eakin EG, Lawler SP, Winkler EA, Hayes SC. A randomised trial of a telephone-delivered exercise intervention for non-urban dwelling women newly diagnosed with breast cancer: Exercise for health. Ann Behav Med (2012) 43(2):229–38. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9324-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Irwin ML, Crumley D, McTiernan A, Bernstein L, Baumgartner R, Gilliland FD, et al. Physical activity levels before and after a diagnosis of breast carcinoma: The health, eating, activity, and lifestyle (Heal) study. Cancer (2003) 97(7):1746–57. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Phillips SM, Dodd KW, Steeves J, McClain J, Alfano CM, McAuley E. Physical activity and sedentary behavior in breast cancer survivors: New insight into activity patterns and potential intervention targets. Gynecol Oncol (2015) 138(2):398–404. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.05.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Blanchard CM, Courneya KS, Stein K, American Cancer Society's SCS, II . Cancer survivors' adherence to lifestyle behavior recommendations and associations with health-related quality of life: Results from the American cancer society's scs-ii. J Clin Oncol (2008) 26(13):2198–204. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.6217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Maass SW, Roorda C, Berendsen AJ, Verhaak PF, de Bock GH. The prevalence of long-term symptoms of depression and anxiety after breast cancer treatment: A systematic review. Maturitas (2015) 82(1):100–8. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rottmann N, Hansen DG, Hagedoorn M, Larsen PV, Nicolaisen A, Bidstrup PE, et al. Depressive symptom trajectories in women affected by breast cancer and their Male partners: A nationwide prospective cohort study. J Cancer Surviv (2016) 10(5):915–26. doi: 10.1007/s11764-016-0538-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Herrero F, San Juan AF, Fleck SJ, Balmer J, Perez M, Canete S, et al. Combined aerobic and resistance training in breast cancer survivors: A randomized, controlled pilot trial. Int J Sports Med (2006) 27(7):573–80. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-865848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Schapira DV, Kumar NB, Lyman GH, Cox CE. Obesity and body fat distribution and breast cancer prognosis. Cancer (1991) 67(2):523–8. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Holmes MD, Kroenke CH. Beyond treatment: Lifestyle choices after breast cancer to enhance quality of life and survival. Womens Health Issues (2004) 14(1):11–3. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2003.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rockhill B, Willett WC, Hunter DJ, Manson JE, Hankinson SE, Colditz GA. A prospective study of recreational physical activity and breast cancer risk. Arch Intern Med (1999) 159(19):2290–6. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.19.2290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (Prisma-p) 2015 statement. Syst Rev (2015) 4:1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The prisma 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (2021) 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. Amstar 2: A critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ (2017) 358:j4008. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Boing L, Vieira MCS, Moratelli J, Bergmann A, Guimaraes ACA. Effects of exercise on physical outcomes of breast cancer survivors receiving hormone therapy - a systematic review and meta-analysis. Maturitas (2020) 141:71–81. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2020.06.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Abdin S, Lavallee JF, Faulkner J, Husted M. A systematic review of the effectiveness of physical activity interventions in adults with breast cancer by physical activity type and mode of participation. Psychooncology (2019) 28(7):1381–93. doi: 10.1002/pon.5101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hong F, Ye W, Kuo CH, Zhang Y, Qian Y, Korivi M. Exercise intervention improves clinical outcomes, but the "Time of session" is crucial for better quality of life in breast cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancers (Basel) (2019) 11(5):706. doi: 10.3390/cancers11050706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Soares Falcetta F, de Araujo Vianna Trasel H, de Almeida FK, Rangel Ribeiro Falcetta M, Falavigna M, Dornelles Rosa D. Effects of physical exercise after treatment of early breast cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat (2018) 170(3):455–76. doi: 10.1007/s10549-018-4786-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Singh B, Spence RR, Steele ML, Sandler CX, Peake JM, Hayes SC. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the safety, feasibility, and effect of exercise in women with stage ii+ breast cancer. Arch Phys Med Rehabil (2018) 99(12):2621–36. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2018.03.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zhang X, Li Y, Liu D. Effects of exercise on the quality of life in breast cancer patients: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Support Care Cancer (2019) 27(1):9–21. doi: 10.1007/s00520-018-4363-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gebruers N, Camberlin M, Theunissen F, Tjalma W, Verbelen H, Van Soom T, et al. The effect of training interventions on physical performance, quality of life, and fatigue in patients receiving breast cancer treatment: A systematic review. Support Care Cancer (2019) 27(1):109–22. doi: 10.1007/s00520-018-4490-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kannan P, Lam HY, Ma TK, Lo CN, Mui TY, Tang WY. Efficacy of physical therapy interventions on quality of life and upper quadrant pain severity in women with post-mastectomy pain syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Qual Life Res (2022) 31(4):951–73. doi: 10.1007/s11136-021-02926-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Salam A, Woodman A, Chu A, Al-Jamea LH, Islam M, Sagher M, et al. Effect of post-diagnosis exercise on depression symptoms, physical functioning and mortality in breast cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized control trials. Cancer Epidemiol (2022) 77:102111. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2022.102111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wang J, Chen X, Wang L, Zhang C, Ma J, Zhao Q. Does aquatic physical therapy affect the rehabilitation of breast cancer in women? a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PloS One (2022) 17(8):e0272337. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0272337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ye XX, Ren ZY, Vafaei S, Zhang JM, Song Y, Wang YX, et al. Effectiveness of baduanjin exercise on quality of life and psychological health in postoperative patients with breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Integr Cancer Ther (2022) 21:15347354221104092. doi: 10.1177/15347354221104092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Batterham SI, Heywood S, Keating JL. Systematic review and meta-analysis comparing land and aquatic exercise for people with hip or knee arthritis on function, mobility and other health outcomes. BMC Musculoskelet Disord (2011) 12:123. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-12-123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Taylor DL, Nichols JF, Pakiz B, Bardwell WA, Flatt SW, Rock CL. Relationships between cardiorespiratory fitness, physical activity, and psychosocial variables in overweight and obese breast cancer survivors. Int J Behav Med (2010) 17(4):264–70. doi: 10.1007/s12529-010-9076-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Pedersen BK, Saltin B. Evidence for prescribing exercise as therapy in chronic disease. Scand J Med Sci Sports (2006) 16 Suppl 1:3–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2006.00520.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. De Luca V, Minganti C, Borrione P, Grazioli E, Cerulli C, Guerra E, et al. Effects of concurrent aerobic and strength training on breast cancer survivors: A pilot study. Public Health (2016) 136:126–32. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2016.03.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Watson T, Mock V. Exercise as an intervention for cancer-related fatigue. Phys Ther (2004) 84(8):736–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Bidonde J, Busch AJ, Webber SC, Schachter CL, Danyliw A, Overend TJ, et al. Aquatic exercise training for fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2014) 10):CD011336. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Park J, Lee D, Lee S, Lee C, Yoon J, Lee M, et al. Comparison of the effects of exercise by chronic stroke patients in aquatic and land environments. J Phys Ther Sci (2011) 23(5):821–4. doi: 10.1589/jpts.23.821 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Elavsky S, McAuley E, Motl RW, Konopack JF, Marquez DX, Hu L, et al. Physical activity enhances long-term quality of life in older adults: Efficacy, esteem, and affective influences. Ann Behav Med (2005) 30(2):138–45. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3002_6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Invernizzi M, Lippi L, Folli A, Turco A, Zattoni L, Maconi A, et al. Integrating molecular biomarkers in breast cancer rehabilitation. what is the current evidence? A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Front Mol Biosci (2022) 9:930361. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2022.930361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lippi L, de Sire A, Mezian K, Curci C, Perrero L, Turco A, et al. Impact of exercise training on muscle mitochondria modifications in older adults: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Aging Clin Exp Res (2022) 34(7):1495–510. doi: 10.1007/s40520-021-02073-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Abbasi F, Pourjalali H, do Nascimento IJB, Zargarzadeh N, Mousavi SM, Eslami R, et al. The effects of exercise training on inflammatory biomarkers in patients with breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cytokine (2022) 149:155712. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2021.155712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions and search strategy presented in the study are included in the article/ Supplementary Material . Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.