Abstract

Objective:

To describe the prevalence of diagnosed depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia in people with HIV (PWH) and the differences in HIV care continuum outcomes in those with and without mental health disorders (MHD).

Design:

Observational study of participants in the NA-ACCORD.

Methods:

PWH (≥18 years) contributed data on prevalent schizophrenia, anxiety, depressive, and bipolar disorders from 2008–2018 based on ICD code mapping. MH multimorbidity was defined as having ≥2 MHD. Log binomial models with generalized estimating equations estimated adjusted prevalence ratios (aPR) and 95% confidence intervals for retention in care (≥1 visit/year) and viral suppression (HIV RNA ≤00 copies/mL) by presence vs. absence of each MHD between 2016–2018.

Results:

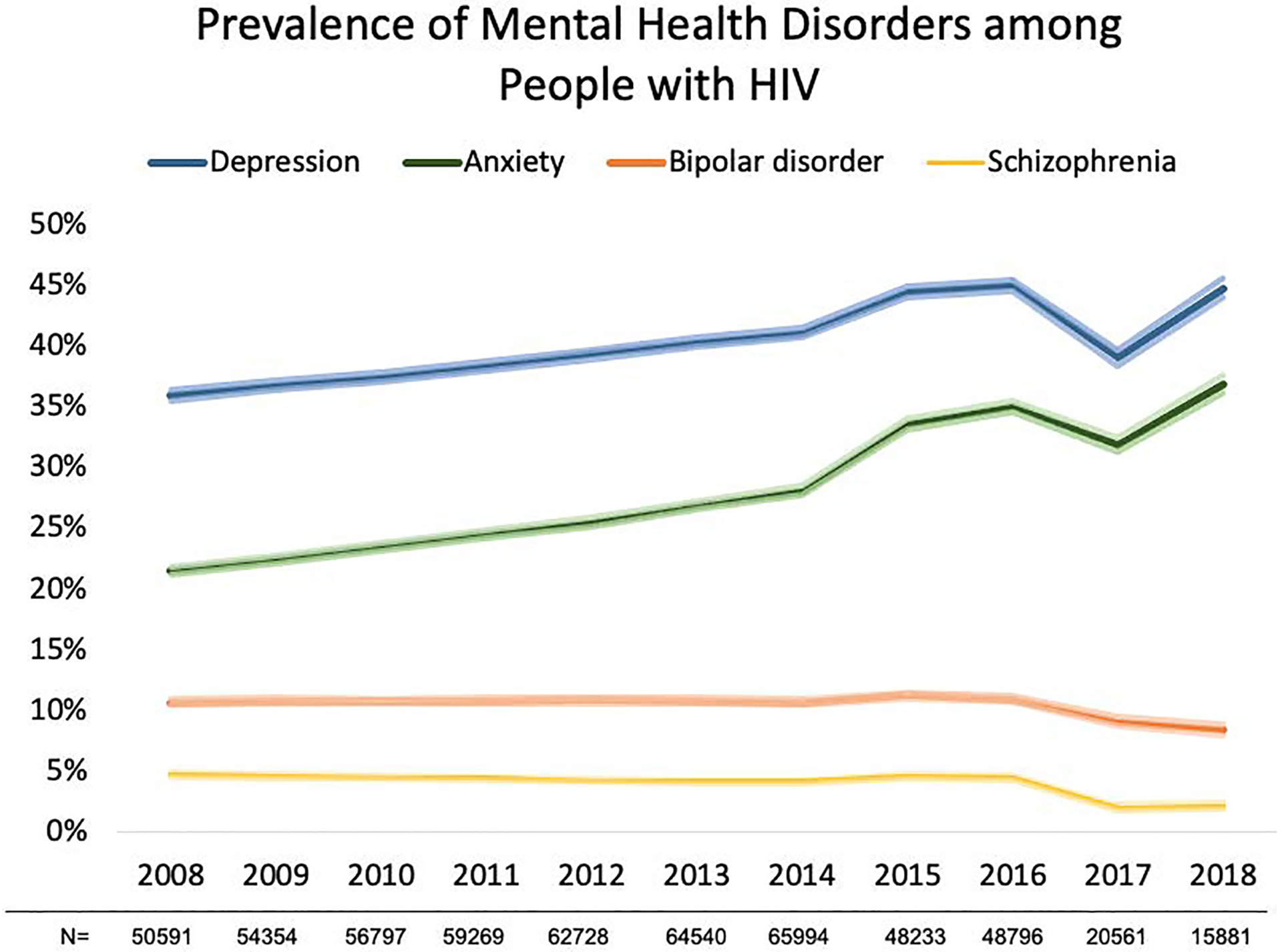

Among 122,896 PWH, 67,643 (55.1%) were diagnosed with ≥1 MHD: 39% with depressive disorders, 28% with anxiety disorders, 10% with bipolar disorder, and 5% with schizophrenia. The prevalence of depressive and anxiety disorders increased between 2008–2018, while bipolar disorder and schizophrenia remained stable. MH multimorbidity affected 24% of PWH. From 2016–2018 (N=64,684), retention in care was marginally lower among PWH with depression or anxiety, however those with MH multimorbidity were more likely to be retained in care. PWH with bipolar disorder had marginally lower prevalence of viral suppression (aPR=0.98 [0.98–0.99]) as did PWH with MH multimorbidity (aPR=0.99 [0.99–1.00]) compared with PWH without MHD.

Conclusion:

The prevalence of MHD among PWH was high, including MH multimorbidity. Although retention and viral suppression were similar to people without MHD, viral suppression was lower in those with bipolar disorder and MH multimorbidity.

INTRODUCTION

With advances in HIV care, chronic disease management including care for co-occurring mental health disorders (MHDs) among people with HIV (PWH) has become a primary focus of attention[1]. MHDs remain a significant source of morbidity and mortality across the world;[2] however, health outcomes of PWH with MHDs remains under studied, particularly within the Treat All era (≥2015)[3]. At the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (ART) (1996), estimates of 12-month prevalence of MHDs among PWH in the US found nearly half of PWH screened positive for ≥1 of: major depression, dysthymia, generalized anxiety disorder, or panic attacks[4]. Studies have reported the prevalence of major depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder (BD), and schizophrenia are more common among PWH compared to the general population[5–13].

MHDs have been associated with adverse outcomes in PWH, including unsuppressed viral load and excess mortality[14–16]. Prior to the Treat All era, adherence to ART in PWH with BD was 48% compared to 91% among PWH without BD[17]. Schizophrenia in PWH has been associated with reduced linkage into care and adherence to treatment[18]. PWH who have effective treatment of their psychiatric symptoms are more successful in their HIV treatment[9, 19], underlining the importance of early screening and evidence-based treatment for MHDs among PWH[20].

HIV and depressive disorders are predicted to be the top two leading causes of burden of disease by 2030[21]. Estimates of the burden of MHDs among PWH are important for guiding policy and programs to ensure access to care, retention in care, viral suppression, and increased wellbeing of PWH. The objective of this study was to describe the prevalence of schizophrenia, anxiety, BD and depressive disorders in PWH in North America, and the relationship of these disorders on HIV care continuum outcomes during the transition to the Treat All era.

METHODS

Study population

The North American AIDS Cohort Collaboration on Research and Design (NA-ACCORD) is a consortium of HIV cohort studies located throughout the United States and Canada [22]. Participants in contributing clinical cohorts who linked into care (i.e., ≥2 HIV care visits in 12 months) were enrolled in the NA-ACCORD. NA-ACCORD participants have similar demographics to the population of PWH in the US[23]. Each participating cohort annually submits data in a standardized format to the Data Management Core (DMC, University of Washington, Seattle WA). The DMC assesses data quality, harmonizes the data, and securely transfers it to the Epidemiology/Biostatistics Core (EBC, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore MD). The EBC identifies cohort-specific “observation-windows” for outcomes to minimize the risk of falsely assuming complete event ascertainment from electronic health records[24]. Each participating cohort has been granted ethics approval by their respective local institutional review boards, as well as by the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

The source population for our nested study were PWH (≥18 years) participating in one of 13 NA-ACCORD-contributing clinical cohorts ascertaining anxiety, depression, BD, and schizophrenia diagnoses. Individual-level selection criteria for our study population included those who were observed in care from Jan 1, 2008 – Dec 31, 2018 (study period).

Mental Health Disorders (MHDs)

Many of the NA-ACCORD clinical cohorts have mental health (MH) screening and treatment within their HIV clinics. Cohorts collected inpatient and outpatient MH diagnoses from health records using a list of ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes for depression, anxiety, BD, and schizophrenia (Supplement Table 1). Each MHDs was defined as having at least one documented diagnosis over the follow-up period. MH multimorbidity was defined as ≥2 MHDs (depression, anxiety, BD, or schizophrenia). A diagnosis of BD excluded classification of this participant as having depression; these two diagnoses were considered mutually exclusive[25]. Treatment data for BD and schizophrenia was obtained at the first time an individual met the criteria for a BD or schizophrenia diagnosis and was prescribed a treatment medication (Supplemental Table 1). Due to the lack of specificity of medications for depression and anxiety, treatment data for these disorders were not included.

HIV Care Continuum Outcomes: Retention in care and viral suppression

Retention in care was defined as having at least one HIV primary care visit within a calendar year. Viral suppression was defined as having an HIV RNA <200 copies/mL at the patient’s last measurement of the year; this cut-off reflected the highest lower limit of quantification among assays used by contributing cohorts.

Covariates of interest

Covariates of interest were included based on review of relevant literature and a priori hypotheses of association with HIV care continuum outcomes. Sex was defined as sex assigned at birth. Race/ethnicity was grouped into non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and other/unknown. HIV acquisition risk group was determined at enrollment into the NA-ACCORD; using a mutually exclusive hierarchy: 1) injection drug use (IDU); 2) men who have sex with men (MSM); 3) heterosexual sexual contact; 4) other/unknown risk. Cigarette smoking was ever/never use. At-risk alcohol use was ever having an alcohol abuse or dependence diagnosis in the medical record. CD4 count and HIV RNA were measured at baseline (i.e., the closest measurement to study entry, within 9 months prior through 3 months after study entry). ART regimen was also assessed at baseline (i.e., the closest record to study entry, ±6 months) and classified as at least two antiviral drugs from at least one drug class (non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs), protease inhibitors (PI), integrase inhibitors, other/unknown).

Comorbidities were assessed at baseline (i.e., prior to study entry through 9 months after entry) using operationalized definitions for treated hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hypercholesterolemia and stage 3 chronic kidney disease (CKD), which have been described elsewhere[26, 27]. Hepatitis B (HBV) and Hepatitis C (HCV) infection were parameterized as ever/never (Supplemental Table 2).

Statistical Analysis

Study entry was defined as the date the cohort began observing patients, MH observation-window open date, patient enrollment into the NA-ACCORD, or January 1, 2008, whichever came last. The MH observation-window was specific to the cohort and defined as the calendar years when the cohort was ascertaining diagnoses for all four MHDs. Study exit was defined as the earliest date the cohort stopped observing patients, MH observation-window close date, the date the patient was lost to follow-up (LTFU, defined as 1.5 years with no CD4 or HIV RNA measurement), date of death, or December 31, 2018, whichever came first.

Pearson chi-square tests and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to assess the differences in demographic and clinical characteristics by each MHDs. Annual prevalence for each MHDs was estimated among those in care in the year, and trends were evaluated from January 1, 2008 – December 31, 2018, with a log binomial model with generalized estimating equations (GEE) with an independent working correlation matrix (as participants could contribute information to multiple years) that included calendar year as a continuous variable to test the hypothesis that there was no change in prevalence from one year to the next. We estimated MHDs as ever having clinical diagnosis of these conditions (cumulative) which can result in increased prevalence with increasing time; however, given the open cohort design of the NA-ACCORD, individuals can enter and exit care, reflecting PWH in clinical care in any given year.

Retention in care and HIV viral suppression were estimated among those observed in care from January 1, 2016, to December 31, 2018 (the most recent years of available data) and stratified by the four MHDs categories and MH multimorbidity; estimates of HIV viral suppression were further restricted to include only those who initiated ART. In alignment with the trends in prevalence of MHDs analysis, log binomial models with GEE (independent working correlation matrix) estimated crude (PR) and adjusted prevalence ratios (aPR) and associated 95% confidence intervals ([–]) for each MHDs in this two-year period. As is recommended when investigating disparities, we did not include variables that may be downstream of MHDs so as to avoid inappropriate attenuation of potential MHDs disparities in retention in care or viral suppression; multivariable models included demographic characteristics (age, sex, race/ethnicity, HIV acquisition risk group, and cohort) in addition to the MHDs of interest[28, 29]. Subgroup analyses were conducted to evaluate whether having an untreated BD or schizophrenia was associated with a difference on retention in care or viral suppression. A sensitivity analysis defining HIV viral suppression as <50 copies/mL was conducted as this was the lower limit of detection across cohorts during the restricted study period (2016–2018) (Supplemental Table 3). All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary North Carolina).

RESULTS

Characteristics of the Study Population

Among 122,896 PWH included in this study between 2008–2018, 67,643 (55%) were diagnosed with at least one of the four assessed MHDs: 47,553 (39%) were diagnosed with depressive disorder, 34,219 (28%) with anxiety disorder, 11,716 (10%) with BD, and 5,022 (5%) with schizophrenia (Supplement Figure 1). In the last two years of observation (2016–2018) (n=64,689), the prevalence of depression was 43%, anxiety was 35%, BD was 10% and schizophrenia was 5% (Figure 1). Among the study population, 1494 (1%) were LTFU, of whom 880 (59%) had a diagnosis of one or more MHDs, and 527 (35%) had an unsuppressed viral load.

Figure 1:

Prevalence (and 95% confidence intervals represented by the lighter color shade) of mental health disorders, 2008–2018.

Trends in annual prevalence for each mental health disorder evaluated with a log binomial model with generalized estimating equations, depressive disorder (p for trend= 0.001), anxiety disorder (p for trend= <0.001), bipolar disorder (p for trend= 0.058), and schizophrenia (p for trend= 0.013).

Fluctuations in annual prevalence in 2017 and 2018 in mental health disorders may be due to less PWH being observed in our study during this time.

A greater proportion of those with depression, anxiety and BD were non-Hispanic white PWH, whereas a greater proportion of those with schizophrenia were non-Hispanic Black PWH compared to those without these diagnoses. The median age at study entry was older among those with schizophrenia (51 years [interquartile range (IQR): 44, 57]) compared to those without schizophrenia (46 years [IQR: 37, 54]). PWH with any of these MHDs were more likely to have a history of IDU as an HIV acquisition risk factor and were more likely to smoke, have HCV coinfection, and hypertension compared to those without these diagnoses. Those with schizophrenia were more likely to have diabetes (Table 1).

Table 1:

Demographic characteristics at study entry among PWH in the NA-ACCORD and under observation for mental health outcomes between 2008–2018 (N=122,896).

| Overall | Depression | Anxiety | Bipolar Disorder | Schizophrenia | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=122,896 | No Depression n=75,343 |

Depression n=47,553 |

No Anxiety n=88,677 |

Anxiety n=34,219 |

No Bipolar Disorder n=111,189 |

Bipolar Disorder n=11,716 |

No Schizophrenia n=117,874 |

Schizophrenia n=5,022 |

||||||||||

| Characteristics | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | N | % | n | % |

| Age | ||||||||||||||||||

| Median (IQR) | 46 (37–54) | 45 (35–53) | 47 (39–55) | 46 (36–54) | 47 (39–54) | 46 (37–54) | 46 (38–53) | 46 (37–54) | 51 (44–57) | |||||||||

| Sex | ||||||||||||||||||

| Male | 104062 | 85% | 63524 | 84% | 40538 | 85% | 74216 | 84% | 29846 | 87% | 94408 | 85% | 9654 | 82% | 99687 | 85% | 4375 | 87% |

| Female | 18832 | 15% | 11819 | 16% | 7013 | 15% | 14458 | 16% | 4374 | 13% | 16770 | 15% | 2062 | 18% | 18184 | 15% | 648 | 13% |

| Race | ||||||||||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 44816 | 36% | 25796 | 34% | 19019 | 40% | 29022 | 33% | 15794 | 46% | 39626 | 36% | 5190 | 44% | 43516 | 37% | 1300 | 26% |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 52196 | 42% | 32902 | 44% | 19295 | 41% | 40677 | 46% | 11519 | 34% | 47384 | 43% | 4812 | 41% | 49163 | 42% | 3033 | 60% |

| Hispanic | 17651 | 14% | 10938 | 15% | 6713 | 14% | 12557 | 14% | 5094 | 15% | 16382 | 15% | 1269 | 11% | 17100 | 15% | 551 | 11% |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 2219 | 2% | 1517 | 2% | 703 | 1% | 1714 | 2% | 505 | 1% | 2125 | 2% | 94 | 1% | 2186 | 2% | 33 | 1% |

| Other/Unknown | 6014 | 5% | 4191 | 6% | 1823 | 4% | 4706 | 5% | 1308 | 4% | 5663 | 5% | 351 | 3% | 5908 | 5% | 106 | 2% |

| HIV acquisition risk | ||||||||||||||||||

| IDU | 21115 | 17% | 10656 | 14% | 10459 | 22% | 12265 | 14% | 8850 | 26% | 16487 | 15% | 4628 | 40% | 18452 | 16% | 2663 | 53% |

| MSM | 42869 | 35% | 28477 | 38% | 14392 | 30% | 32157 | 36% | 10712 | 31% | 39954 | 36% | 2915 | 25% | 42379 | 36% | 490 | 10% |

| Heterosexual contact | 24662 | 20% | 17061 | 23% | 7601 | 16% | 20609 | 23% | 4053 | 12% | 22916 | 21% | 1746 | 15% | 23987 | 20% | 675 | 13% |

| Other/Unknown | 34250 | 28% | 19149 | 25% | 15101 | 32% | 23645 | 27% | 10605 | 31% | 31823 | 29% | 2427 | 21% | 33055 | 28% | 1195 | 24% |

| Smoking | ||||||||||||||||||

| Never | 26585 | 22% | 15963 | 21% | 10621 | 22% | 18691 | 21% | 7892 | 23% | 24978 | 22% | 1607 | 14% | 25991 | 22% | 594 | 12% |

| Ever | 61191 | 50% | 32229 | 43% | 28963 | 61% | 39501 | 45% | 21690 | 63% | 52673 | 47% | 8518 | 73% | 57253 | 49% | 3938 | 78% |

| Not assessed | 35120 | 29% | 27151 | 36% | 7969 | 17% | 30484 | 34% | 4636 | 14% | 33529 | 30% | 1591 | 14% | 34629 | 29% | 491 | 10% |

| Hepatitis C infection | 25009 | 20% | 13459 | 18% | 11551 | 24% | 16323 | 18% | 8686 | 25% | 21006 | 19% | 4003 | 34% | 22814 | 19% | 2195 | 44% |

| Hepatitis B infection | 7004 | 6% | 4196 | 6% | 2808* | 6% | 5084 | 6% | 1920* | 6% | 6268 | 6% | 736* | 6% | 6681 | 6% | 323* | 6% |

| Treated hypertension | 36543 | 30% | 19099 | 25% | 17445 | 37% | 23625 | 27% | 12918 | 38% | 32221 | 29% | 4322 | 37% | 34030 | 29% | 2513 | 50% |

| Diabetes | 12136 | 10% | 6577 | 9% | 5559 | 12% | 8447 | 10% | 3689 | 11% | 10803 | 10% | 1333 | 11% | 11209 | 10% | 927 | 18% |

| CKD stage 2 (eGFR <60) | ||||||||||||||||||

| No | 103064 | 84% | 61511 | 82% | 41553 | 87% | 72926 | 82% | 30138 | 88% | 92597 | 83% | 10467 | 89% | 98721 | 84% | 4343 | 86% |

| Yes | 7978 | 6% | 4669 | 6% | 3309 | 7% | 5792 | 7% | 2186 | 6% | 7295 | 7% | 683 | 6% | 7547 | 6% | 431 | 9% |

| Not assessed | 11854 | 10% | 9163 | 12% | 2691 | 6% | 9958 | 11% | 1896 | 6% | 11288 | 10% | 566 | 5% | 11605 | 10% | 249 | 5% |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 26243 | 21% | 14206 | 19% | 12035 | 25% | 17154 | 19% | 9089 | 27% | 23286 | 21% | 2957 | 25% | 24921 | 21% | 1322 | 26% |

| Statin Use | 20674 | 17% | 11003 | 15% | 9671 | 20% | 13625 | 15% | 7049 | 21% | 18631 | 17% | 2043* | 17% | 19608 | 17% | 1066* | 21% |

| CD4 count (cells/mm3) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Median (IQR) | 431 (251–634) | 428 (247–630) | 435 (258–643) | 421 (240–626) | 454 (279–657) | 430 (250–629) | 439 (265–642) | 423 (234–631) | 412 (237–612) | |||||||||

| <200 | 19986 | 16% | 12521 | 17% | 7465 | 16% | 15293 | 17% | 4693 | 14% | 18317 | 16% | 1669 | 14% | 19212 | 16% | 774 | 15% |

| >=200 | 85238 | 70% | 51917 | 69% | 33321 | 70% | 60584 | 69% | 24654 | 72% | 77174 | 70% | 8064 | 69% | 82142 | 70% | 3096 | 61% |

| Missing | 17571 | 14% | 10905 | 14% | 6727 | 14% | 12799 | 14% | 4873 | 14% | 15689 | 14% | 1983 | 17% | 16519 | 14% | 1153 | 23% |

| HIV RNA (copies/mL) | ||||||||||||||||||

| <200 | 43075 | 35% | 26436 | 35% | 16638 | 35% | 31138 | 35% | 11937 | 35% | 39150 | 35% | 3925 | 34% | 41604 | 35% | 1471 | 29% |

| >=200 | 51433 | 42% | 32139 | 43% | 19294 | 41% | 37676 | 42% | 13757 | 40% | 46465 | 42% | 4968 | 42% | 49448 | 42% | 1985 | 40% |

| Missing | 28388 | 23% | 16768 | 22% | 11621 | 24% | 19862 | 22% | 8526 | 25% | 25565 | 23% | 2823 | 24% | 26821 | 23% | 1567 | 31% |

| Year of ART initiation | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1996–2004 | 33820 | 28% | 17283 | 23% | 16537 | 35% | 22135 | 25% | 11685 | 35% | 29805 | 26% | 4015 | 34% | 31748 | 27% | 2072 | 41% |

| 2005–2009 | 26728 | 22% | 16041 | 21% | 10687 | 22% | 19484 | 22% | 7244 | 21% | 24120 | 22% | 2608 | 22% | 25761 | 22% | 967 | 19% |

| 2010–2018 | 48644 | 40% | 32385 | 43% | 16259 | 34% | 36322 | 41% | 12322 | 36% | 44853 | 40% | 3791 | 32% | 47515 | 40% | 1129 | 22% |

| Not initiate ART | 13690 | 11% | 9622 | 13% | 4068 | 9% | 10726 | 12% | 2964 | 9% | 12391 | 11% | 1299 | 11% | 12835 | 11% | 855 | 17% |

| HIV treatment regimen at ART initiation | ||||||||||||||||||

| NNRTI | 14770 | 12% | 10107 | 13% | 4663 | 10% | 10841 | 12% | 3929 | 12% | 13655 | 12% | 1115 | 10% | 14495 | 12% | 275 | 5% |

| PI | 6609 | 5% | 3913 | 5% | 2696 | 6% | 4689 | 5% | 1920 | 6% | 6023 | 5% | 586 | 5% | 6408 | 5% | 201 | 4% |

| Integrase Inhibitor | 42922 | 35% | 25933 | 35% | 16989 | 36% | 30968 | 35% | 11954 | 35% | 39322 | 36% | 3600 | 31% | 41553 | 35% | 1369 | 27% |

| Other/Unknown | 44343 | 36% | 25402 | 34% | 18941 | 40% | 31021 | 35% | 13322 | 39% | 39266 | 35% | 5077 | 43% | 42029 | 36% | 2314 | 46% |

| Never on HAART | 13690 | 11% | 9622 | 13% | 4068 | 9% | 10726 | 12% | 2964 | 9% | 12391 | 11% | 1299 | 11% | 12835 | 11% | 855 | 17% |

P-values calculated using chi-squared tests for all categorical or binary variables and t-tests for all continuous variables.

All p-values are <0.001, unless specified with (*).

Due to large numbers of participants statistical significance was common, however clinical significance was considered as a difference in 5% between comparison groups and these differences are bolded.

Age, sex, race/ethnicity, and HIV transmission acquisition group are time-fixed variables, measured at enrollment into the NA-ACCORD.

IDU: injection drug use, MSM: Men who have sex with men, NNRTI: non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, PI: Protease inhibitor.

PWH with any of these four MHDs were more likely to have initiated ART prior to 2005 compared to PWH without each MHDs (Table 1), suggesting those with longer durations of HIV care may also be more likely to have a diagnosed MHDs. There were no significant differences in CD4 count or HIV RNA levels at study entry between those with and without depression, anxiety, or BD. PWH with schizophrenia were more likely to have missing CD4 or HIV RNA measurements at study entry and to have never initiated ART (Table 1).

Prevalence of MHDs and the effects on the HIV Care Continuum

Depression

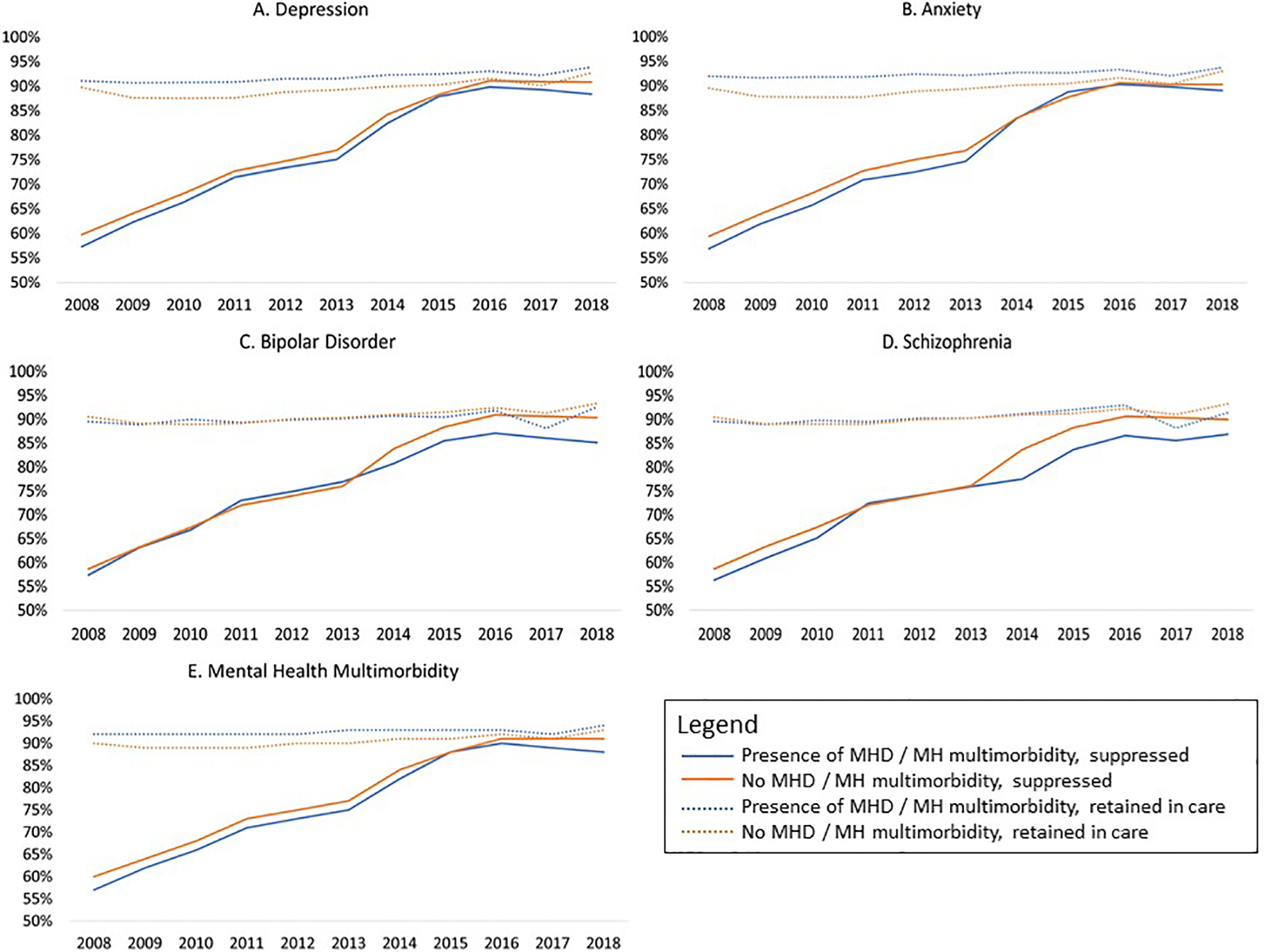

The prevalence of depressive disorder increased from 35.9% [35.5–36.4%] in 2008 to 44.8% [44.0–45.5%] in 2018 (p=0.001 for annual trend) (Figure 1). Those with depression had a higher annual prevalence of retention in care, and lower annual prevalence of viral suppression, compared with those without depression from 2008–2018 (p<0.01) (Figure 2a). In adjusted models however, PWH with depression had a 2% [0.97–0.98%] lower prevalence of retention in care and a statistically nonsignificant 1% [0.99–1.00%] lower prevalence of viral suppression than those without depression in recent years (2016–2018) (Table 2).

Figure 2:

Trends in retention in care and viral suppression by a) depression diagnoses, b) anxiety diagnoses, c) bipolar disorder diagnosis, and c) schizophrenia diagnosis, 2008–2018 (N=122,896)

Retention is defined as 2 or more HIV care visits between 2016–2018.

Suppression defined as having a viral load ≤200 copies/mL between 2016–2018.

Table 2:

The impact of Mental Health Disorders on the HIV care continuum among PWH on ART (2016–2018)

| n | % | PRa | 95% CI | aPRb | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retained in Care (N=54,606) | |||||||

| No depression | 30463 | 56% | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Depression | 24143 | 44% | 1.03 | 1.03–1.04 | 0.98 | 0.97–0.98 | |

| No anxiety | 35068 | 64% | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Anxiety | 19538 | 36% | 1.03 | 1.02–1.03 | 0.98 | 0.97–0.98 | |

| No bipolar disorder | 48943 | 90% | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Bipolar disorder | 5663 | 10% | 1.01 | 1.00–1.01 | 1.00 | 1.00–1.01 | |

| No schizophrenia | 52304 | 96% | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Schizophrenia | 2302 | 4% | 1.01 | 1.00–1.03 | 1.00 | 1.00– 1.01 | |

| No MH Disorder | 20724 | 38% | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| One MH Disorder | 17101 | 31% | 1.02 | 1.02–1.03 | 1.01 | 1.01– 1.01 | |

| MH Multimorbidityc | 16781 | 31% | 1.04 | 1.04–1.05 | 1.02 | 1.02– 1.02 | |

| Suppressed HIV RNA (≤200 copies/mL) (N=20,231) | |||||||

| No depression | 12625 | 62% | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Depression | 7606 | 38% | 0.99 | 0.98– 0.99 | 1.01 | 1.00–1.02 | |

| No anxiety | 13901 | 69% | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Anxiety | 6330 | 31% | 1.00 | 1.00– 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.00–1.01 | |

| No bipolar disorder | 18572 | 92% | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Bipolar disorder | 1659 | 8% | 0.95 | 0.94–0.97 | 0.98 | 0.98–0.99 | |

| No schizophrenia | 19865 | 98% | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Schizophrenia | 366 | 2% | 0.96 | 0.93–0.99 | 1.00 | 0.98–1.01 | |

| No MH Disorder | 9136 | 45% | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| One MH Disorder | 6282 | 31% | 0.97 | 0.97–0.98 | 0.99 | 0.99–1.00 | |

| MH Multimorbidityc | 4813 | 24% | 0.98 | 0.97–0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99–1.00 | |

PR = unadjusted prevalence ratio from a log binomial regression model

aPR = adjusted prevalence ratio from a log binomial regression model, adjusted for decade of age, race/ethnicity (due to small numbers, Asian/PI was collapsed into the other/unknown category), sex, HIV acquisition risk group, and cohort.

Mental health multimorbidity included those with ≥2 MH comorbidities

Values with P<0.05 are bolded.

Anxiety

The prevalence of anxiety disorder increased from 21.5% [21.1–21.8%] in 2008 to 36.9% [36.1–37.6%] in 2018 (p=0.001 for annual trend) (Figure 1). Those with anxiety had higher annual proportion of retention in care compared to those without anxiety between 2008–2017 (p<0.01). From 2008 to 2013, those with anxiety had a consistently lower viral suppression compared to those without anxiety (p<0.001), however viral suppression was similar by anxiety diagnosis from 2014–2018 (Figure 2b). In adjusted models PWH with anxiety had a 2% [0.97–0.98] lower prevalence of retention in care than those without anxiety in recent years (2016–2018). Those with anxiety had no difference in the prevalence of viral suppression compared to those without anxiety in both crude and adjusted models (Table 2).

Bipolar Disorder

Unlike depression and anxiety, the prevalence of BD decreased over calendar time, from 10.7% [10.4–10.9%] in 2008 to 8.4% [7.9–8.8%] in 2018 (p=0.058 for annual trend) (Figure 1). There was minimal difference in annual trends of the proportions retained in care among those with and without BD from 2008–2018. Those with and without BD had similar proportions virally suppressed from 2008–2013, but from 2014–2018 the proportion suppressed was lower in those with BD compared to those without BD (p<0.001) (Figure 2c). Those with BD had no difference in the prevalence of retention in care compared to those without (2016–2018) in adjusted models. Those with BD had a 5% [0.94–0.97] lower prevalence of viral suppression than those without BD; however, this changed to a 2% [0.98–0.99] lower prevalence of viral suppression among those with BD after adjustment for demographic characteristics (Table 2).

Schizophrenia

The prevalence of schizophrenia declined over time, from 4.7% [4.5%−4.9%] in 2008 to 2.1% [1.9%−2.3%] in 2018 (p=0.013 for annual trend) (Figure 1). Those with schizophrenia had similar retention in care to those without from 2008–2014, and a higher proportion retained in care in 2015–2016 (p<0.01). Those with and without schizophrenia had similar viral suppression until 2013; from 2014–2017 those with schizophrenia were less likely to be virally suppressed compared to those without schizophrenia (p<0.001) (Figure 2d). In adjusted models PWH with schizophrenia had no difference in the prevalence of retention in care compared to those without schizophrenia (2016–2018). Those with schizophrenia had a 4% [0.93–0.99] decrease in the prevalence of viral suppression compared to those without schizophrenia, and this attenuated to no difference after adjustment for demographic characteristics (Table 2).

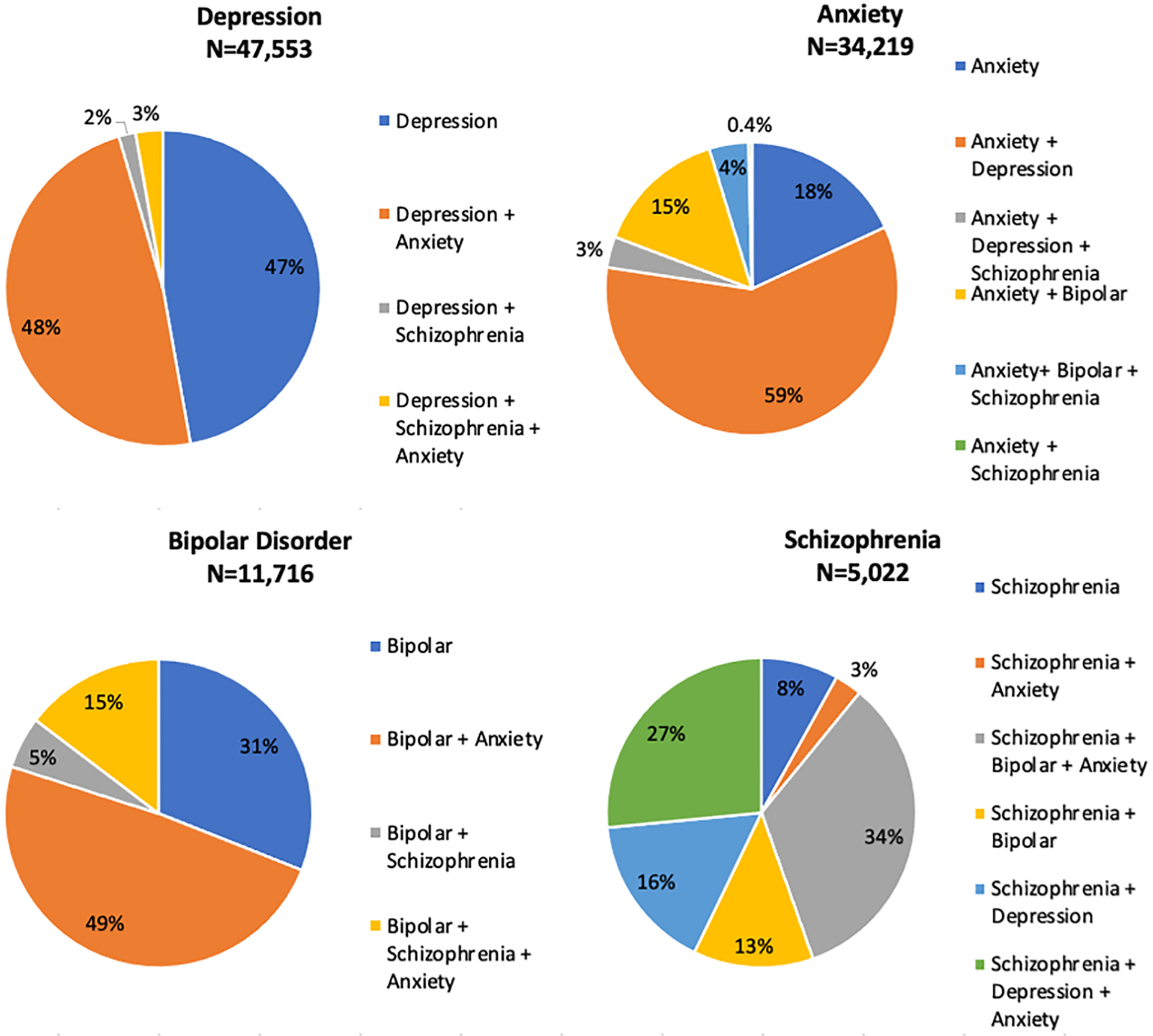

Multimorbidity of MHDs among PWH

From 2008–2018, MH multimorbidity prevalence was 24% (29,243/122,896), with 92% of those with schizophrenia (n=5,022), 82% with anxiety (n=34,219), 69% with BD (n=11,716) and 53% with depression (n=47,553) having a diagnosis of at least one other MHDs (Figure 3). Anxiety was the most common MH comorbidity among those with depression, BD, and schizophrenia. From 2008–2017, the annual proportion of PWH retained in care was similar but consistently higher in those with (vs. without) MH multimorbidity (p<0.001), whereas viral suppression was similar but consistently lower among PWH with MH multimorbidity (p<0.001), with a gap beginning to widen from 2016–2018 (Figure 2e).

Figure 3:

The percentage mental health multimorbidity, by individual mental health comorbidity, 2008–2018.

A diagnosis of BD excluded classification of this participant as having depression; these two diagnoses were considered mutually exclusive

In more recent years (2016–2018), the prevalence of MH multimorbidity was 16% (19,457/64,864) among PWH (Supplement Figure 2). Those with MH multimorbidity had a 4% [1.04–1.05%] higher prevalence of retention in care compared to those without MHDs (2016–2018); however, this attenuated to a 2% [1.02–1.02%] higher retention in care after adjustment for demographic characteristics. Those with MH multimorbidity had a 2% [0.97–0.99%] lower prevalence of viral suppression compared to those without MHDs, and this attenuated to a 1% [0.99–1.00%] lower prevalence in viral suppression after adjustment for demographic characteristics (Table 2).

Treated vs. Untreated BD and Schizophrenia

The majority of PWH diagnosed with BD (89%) and schizophrenia (88%) initiated MH treatment. In adjusted analyses there was a statistically nonsignificant 1% lower prevalence of retention in care and viral suppression among PWH with untreated BD compared to those without BD. Untreated schizophrenia was associated with a statistically nonsignificant 1% higher prevalence of retention in care and no difference in viral suppression when compared to PWH without schizophrenia (Supplemental Table 4).

DISCUSSION

MHDs prevalence is high among PWH in North America; many with an MHDs are also MH multimorbid. We found greater prevalence of MHDs in PWH than that reported in other studies of the general US population [30–32]. A nationally representative survey of over 9,000 US adults found 46.4% had a lifetime prevalence of any MHD, and 27.7% had two or more disorders[30]. We evaluated just four MHDs and found 55.1% of PWH had a MHDs and 23.8% had ≥2 MHDs. The general population lifetime prevalence of having a major depressive disorder was 16.6%, generalized anxiety disorder 5.7% and BD was 3.9%[30]; in our study population of PWH the estimate was 2.3-fold higher (38.7%) for depression, 4.9-fold higher (27.8%) for anxiety, and 2.4-fold higher (9.5%) for BD. The lifetime prevalence of schizophrenia in US adults is approximately 0.4%[31–33], and >10-fold higher (4.1%) in our study population of PWH.

From 2008–2018, the annual prevalence of depression and anxiety increased among PWH in our dynamic study population, which reflects trends in the US general population.[34, 35] This increase is likely multifactorial and may be influenced by a greater clinical recognition over time, increased incidence, or increased duration of depression or anxiety disorder due to delayed diagnosis and treatment[35]. BD and schizophrenia remained stable until recent years, when prevalence decreased among PWH in our study population. Studies from the US general population suggest either stable or decreasing prevalence of both BD and schizophrenia[36–40]. Reasons for these trend shown in both our study population and the US general population are unknown, with suggestions that changing diagnostic criteria may be contributory[36–39].

Although prior studies have demonstrated that PWH with MHDs access health services less often and have worse outcomes along the HIV care continuum[1, 41–43], we did not identify large differences associated with MHDs or MH multimorbidity on retention in care or viral suppression. However, we did find PWH with depression and anxiety had marginally lower retention in care and those with MH multimorbidity had marginally increased retention in care. Guidance suggests more frequent follow-up visits for PWH with MHDs[44, 45], therefore despite small differences observed in retention in care between those with and without MHDs, this may signal greater disparity. We found lower viral suppression among PWH with BD and MH multimorbidity compared to those without these diagnoses. Because of the high prevalence of these MHDs among PWH, it is unlikely “Ending the HIV Epidemic” viral suppression goals will be reached without interventions tailored to those with MHDs [46].

The proportion of PWH in NA-ACCORD achieving viral suppression increased between 2008–2018, however it was lower among those with (vs. without) BD and with (vs. without) schizophrenia. Additionally, retention in care was similar among those with (vs. without) these MHDs. PWH who have BD or schizophrenia experience barriers to viral suppression that exist even when they are successfully retained in care, a gap which has widened during the Treat All era. The explanation for this gap is unknown, however factors of influence may include reduced prescription of ART and/or MH treatment, and decreased adherence to, or drug-drug interactions between, ART and MH treatments[47, 48].

Prior studies have found that retention in HIV care and ART adherence was higher among PWH receiving care for their MHDs[49–52]. Combining HIV and MHDs care visits provides added convenience and incentive and may increase access to both types of care. When evaluating PWH with BD and schizophrenia, we found the majority (~90%) had initiated therapy for these disorders. This may explain the minimal differences in HIV care continuum among those with MHDs vs those without. Our findings highlight the success of HIV care programs to provide PWH with both HIV and MH treatment, but also the ongoing need for improved resources for MH screening, linkage to treatment, and support programs to eliminate the identified gaps. The importance of MH services being integrated into HIV care programs has been emphasized through the COVID-19 pandemic as reports suggest increasing prevalence and worsening symptoms of MHDs[53, 54].

One strength of this work is the use of a large, diverse, and representative cohort of PWH who have linked into HIV care in North America. However, enrollment criteria into the NA-ACCORD includes only individuals successfully linked into HIV care. Those who have never linked into care may be more likely to also have MHDs (albeit potentially less likely to have a clinical diagnosis of MHDs) and would not be included in this study population. A second strength lies in the ascertainment for diagnoses to classify PWH as ever having a MHDs, however, underdiagnosis is MHD common in both people with and without HIV.

Limitations include that we did not have sufficient data to evaluate time-varying severity or management of these MHDs and are therefore likely identifying a heterogenous population of MHD severity and treatment among PWH. The generalizability of increased retention in care among PWH with MHDs and multimorbidity may be limited to clinics similar to those contributing to the NA-ACCORD who provide in-clinic MH screening and treatment. MHDs may have been diagnosed prior to or near the time of HIV diagnosis and age at diagnosis was not available. HIV continuum of care outcome definitions allow for comparison of our results to other studies, however the sensitivity of the definitions may be influencing the small differences seen between groups. Retention in care was measured with in-person visits and virtual care visits were not ascertained. Despite this being a large evaluation of MHDs in PWH, we were constrained by a small sample size for certain analyses within a specific MHD. Finally, we could not describe MHDs in PWH by active drug or alcohol use status, socioeconomic status, family history of MHDs or high stress/traumatic life events, which were not measured.

CONCLUSIONS:

This analysis provides novel insight into the prevalence and HIV care continuum outcomes associated with MHDs and multimorbidity in PWH. Due to the high prevalence of MHDs and multimorbidity among PWH, clinicians must remain vigilant with screening for these disorders and providing effective engagement into MH services when needed. Understanding barriers to viral suppression, and effective interventions to overcome such barriers among PWH with MHDs and multimorbidity must continue to be a priority to increase the health and well-being of PWH.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1: Flow chart of study population selection

Supplemental Figure 2: Venn diagram of mental health multimorbidity among people with HIV between 2016–2018 (N=64,864).

Depression and bipolar disorder are considered mutually exclusive; therefore, depression diagnoses were excluded among those with bipolar disorder.

FUNDING

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants U01AI069918, F31AI124794, F31DA037788, G12MD007583, K01AI093197, K01AI131895, K23EY013707, K24AI065298, K24AI118591, K24DA000432, KL2TR000421, N01CP01004, N02CP055504, N02CP91027, P30AI027757, P30AI027763, P30AI027767, P30AI036219, P30AI050409, P30AI050410, P30AI094189, P30AI110527, P30MH62246, R01AA016893, R01DA011602, R01DA012568, R01AG053100, R24AI067039, R34DA045592, U01AA013566, U01AA020790, U01AI038855, U01AI038858, U01AI068634, U01AI068636, U01AI069432, U01AI069434, U01DA036297, U01DA036935, U10EY008057, U10EY008052, U10EY008067, U01HL146192, U01HL146193, U01HL146194, U01HL146201, U01HL146202, U01HL146203, U01HL146204, U01HL146205, U01HL146208, U01HL146240, U01HL146241, U01HL146242, U01HL146245, U01HL146333, U24AA020794, U54GM133807, UL1RR024131, UL1TR000004, UL1TR000083, UL1TR002378, Z01CP010214 and Z01CP010176; contracts CDC-200-2006-18797 and CDC-200-2015-63931 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, USA; contract 90047713 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, USA; contract 90051652 from the Health Resources and Services Administration, USA; the Grady Health System; grants CBR-86906, CBR-94036, HCP-97105 and TGF-96118 from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Canada; Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care, and the Government of Alberta, Canada. Additional support was provided by the National Institute Of Allergy And Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Cancer Institute (NCI), National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute Of Child Health & Human Development , National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), National Institute for MH (NIMH) and National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), National Institute On Aging (NIA), National Institute Of Dental & Craniofacial Research (NIDCR), National Institute Of Neurological Disorders And Stroke , National Institute Of Nursing Research (NINR), National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK).

Conflicts of Interest/Competing interests:

Dr. Althoff is a consultant to the All of Us Research Program and serves on the scientific advisory board for Trio Health. Dr. Gill has received honoraria for ad hoc participation on National HIV advisory Boards to Merck Gilead and ViiV Health. Dr. Rebeiro received honoraria from Gilead and Johnson & Johnson (money paid to individual); funding from NIH/NIAID (money paid to institution). Dr. Eron receives grants and personal fees from ViiV Healthcare, Janssen, and Gilead Sciences and personal fees from Merck, outside the submitted work. All other authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

Availability of data and materials:

Complete data for this study cannot be publicly shared because of legal and ethical restrictions. The NA-ACCORD Principals of Collaboration requires submission and approval of a concept sheet that describes the intended research project for which data are being requested. The NA-ACCORD Executive Committee and the Steering Committee (composed of principle investigators of contributing cohorts) must approve the concept sheet and elect to have their data included for the research project. A signed Data User Agreement is required before data can be released. Guidance for how to obtain NA-ACCORD data are outlined on the NA-ACCORD website (www.naaccord.org/collaboration-policies).

REFERENCES

- 1.Remien RH, Stirratt MJ, Nguyen N, Robbins RN, Pala AN, Mellins CA. Mental health and HIV/AIDS: the need for an integrated response. AIDS 2019; 33(9):1411–1420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walker ER, McGee RE, Druss BG. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2015; 72(4):334–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO. Consolidated Guidelines on the Use of Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating and Preventing HIV Infection: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach. In. Geneva; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bing EG, Burnam MA, Longshore D, Fleishman JA, Sherbourne CD, London AS, et al. Psychiatric disorders and drug use among human immunodeficiency virus--infected adults in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001; 58(8):721–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brody DJ, Pratt LA, Hughes JP. Prevalence of Depression Among Adults Aged 20 and Over: United States, 2013–2016. In: National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, NCHS Data Brief No. 303 2018 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cook JA, Burke-Miller JK, Steigman PJ, Schwartz RM, Hessol NA, Milam J, et al. Prevalence, Comorbidity, and Correlates of Psychiatric and Substance Use Disorders and Associations with HIV Risk Behaviors in a Multisite Cohort of Women Living with HIV. AIDS Behav 2018; 22(10):3141–3154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Do AN, Rosenberg ES, Sullivan PS, Beer L, Strine TW, Schulden JD, et al. Excess burden of depression among HIV-infected persons receiving medical care in the united states: data from the medical monitoring project and the behavioral risk factor surveillance system. PLoS One 2014; 9(3):e92842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rubin LH, Maki PM. HIV, Depression, and Cognitive Impairment in the Era of Effective Antiretroviral Therapy. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2019; 16(1):82–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beer L, Tie Y, Padilla M, Shouse RL, Medical Monitoring P. Generalized anxiety disorder symptoms among persons with diagnosed HIV in the United States. AIDS 2019; 33(11):1781–1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Depp CA, Moore DJ, Patterson TL, Lebowitz BD, Jeste DV. Psychosocial interventions and medication adherence in bipolar disorder. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2008; 10(2):239–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ribeiro CMF, Gurgel WS, Luna JRG, Matos KJN, Souza FGM. Is bipolar disorder a risk factor for HIV infection? J Affect Disord 2013; 146(1):66–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Sousa Gurgel W, da Silva Carneiro AH, Barreto Rebouças D, Negreiros de Matos KJ, do Menino Jesus Silva Leitão T, de Matos e Souza FG, et al. Prevalence of bipolar disorder in a HIV-infected outpatient population. AIDS Care 2013; 25(12):1499–1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Q, Polimanti R, Kranzler HR, Farrer LA, Zhao H, Gelernter J. Genetic factor common to schizophrenia and HIV infection is associated with risky sexual behavior: antagonistic vs. synergistic pleiotropic SNPs enriched for distinctly different biological functions. Hum Genet 2017; 136(1):75–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haas AD, Ruffieux Y, van den Heuvel LL, Lund C, Boulle A, Euvrard J, et al. Excess mortality associated with mental illness in people living with HIV in Cape Town, South Africa: a cohort study using linked electronic health records. Lancet Glob Health 2020; 8(10):e1326–e1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nanni MG, Caruso R, Mitchell AJ, Meggiolaro E, Grassi L. Depression in HIV infected patients: a review. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2015; 17(1):530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gonzalez JS, Batchelder AW, Psaros C, Safren SA. Depression and HIV/AIDS treatment nonadherence: a review and meta-analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2011; 58(2):181–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moore DJ, Posada C, Parikh M, Arce M, Vaida F, Riggs PK, et al. HIV-infected individuals with co-occurring bipolar disorder evidence poor antiretroviral and psychiatric medication adherence. AIDS Behav 2012; 16(8):2257–2266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walsh C, McCann E, Gilbody S, Hughes E. Promoting HIV and sexual safety behaviour in people with severe mental illness: a systematic review of behavioural interventions. Int J Ment Health Nurs 2014; 23(4):344–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murphy K, Edelstein H, Smith L, Clanon K, Schweitzer B, Reynolds L, et al. Treatment of HIV in outpatients with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder and bipolar disease at two county clinics. Community Ment Health J 2011; 47(6):668–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Owe-Larsson B, Sall L, Salamon E, Allgulander C. HIV infection and psychiatric illness. African Journal of Psychiatry 2009; 12(2):115–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med 2006; 3(11):e442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gange SJ, Kitahata MM, Saag MS, Bangsberg DR, Bosch RJ, Brooks JT, et al. Cohort profile: the North American AIDS Cohort Collaboration on Research and Design (NA-ACCORD). Int J Epidemiol 2007; 36(2):294–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Althoff KN, Buchacz K, Hall HI, Zhang J, Hanna DB, Rebeiro P, et al. U.S. trends in antiretroviral therapy use, HIV RNA plasma viral loads, and CD4 T-lymphocyte cell counts among HIV-infected persons, 2000 to 2008. Ann Intern Med 2012; 157(5):325–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Althoff KN, Wong C, Hogan B, Desir F, You B, Humes E, et al. Mind the gap: observation windows to define periods of event ascertainment as a quality control method for longitudinal electronic health record data. Ann Epidemiol 2019; 33:54–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grande I, Berk M, Birmaher B, Vieta E. Bipolar disorder. Lancet 2016; 387(10027):1561–1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wong C, Gange SJ, Buchacz K, Moore RD, Justice AC, Horberg MA, et al. First Occurrence of Diabetes, Chronic Kidney Disease, and Hypertension Among North American HIV-Infected Adults, 2000–2013. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 64(4):459–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chou R, Dana T, Blazina I, Daeges M, Bougatsos C, Jeanne TL. Screening for Dyslipidemia in Younger Adults: A Systematic Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2016; 165(8):560–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaufman JS. Statistics, Adjusted Statistics, and Maladjusted Statistics. Am J Law Med 2017; 43(2–3):193–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fox MP, Murray EJ, Lesko CR, Sealy-Jefferson S. On the Need to Revitalize Descriptive Epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol 2022; 191(7):1174–1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62(6):593–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saha S, Chant D, Welham J, McGrath J. A systematic review of the prevalence of schizophrenia. PLoS Med 2005; 2(5):e141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kessler RC, Birnbaum H, Demler O, Falloon IR, Gagnon E, Guyer M, et al. The prevalence and correlates of nonaffective psychosis in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Biol Psychiatry 2005; 58(8):668–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Desai PR, Lawson KA, Barner JC, Rascati KL. Identifying patient characteristics associated with high schizophrenia-related direct medical costs in community-dwelling patients. J Manag Care Pharm 2013; 19(6):468–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goodwin RD, Weinberger AH, Kim JH, Wu M, Galea S. Trends in anxiety among adults in the United States, 2008–2018: Rapid increases among young adults. J Psychiatr Res 2020; 130:441–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weinberger AH, Gbedemah M, Martinez AM, Nash D, Galea S, Goodwin RD. Trends in depression prevalence in the USA from 2005 to 2015: widening disparities in vulnerable groups. Psychol Med 2018; 48(8):1308–1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frisher M, Crome I, Martino O, Croft P. Assessing the impact of cannabis use on trends in diagnosed schizophrenia in the United Kingdom from 1996 to 2005. Schizophr Res 2009; 113(2–3):123–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Woogh C Is schizophrenia on the decline in Canada? Can J Psychiatry 2001; 46(1):61–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pilon D, Patel C, Lafeuille MH, Zhdanava M, Lin D, Cote-Sergent A, et al. Prevalence, incidence and economic burden of schizophrenia among Medicaid beneficiaries. Curr Med Res Opin 2021; 37(10):1811–1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leclerc J, Lesage A, Rochette L, Huynh C, Pelletier E, Sampalis J. Prevalence of depressive, bipolar and adjustment disorders, in Quebec, Canada. J Affect Disord 2020; 263:54–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kessler RC, Demler O, Frank RG, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Walters EE, et al. Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders, 1990 to 2003. N Engl J Med 2005; 352(24):2515–2523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burnam MA, Bing EG, Morton SC, Sherbourne C, Fleishman JA, London AS, et al. Use of mental health and substance abuse treatment services among adults with HIV in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001; 58(8):729–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yehia BR, Stephens-Shield AJ, Momplaisir F, Taylor L, Gross R, Dubé B, et al. Health Outcomes of HIV-Infected People with Mental Illness. AIDS Behav 2015; 19(8):1491–1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pence BW, Mills JC, Bengtson AM, Gaynes BN, Breger TL, Cook RL, et al. Association of Increased Chronicity of Depression With HIV Appointment Attendance, Treatment Failure, and Mortality Among HIV-Infected Adults in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry 2018; 75(4):379–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gelenberg AJ. A review of the current guidelines for depression treatment. J Clin Psychiatry 2010; 71(7):e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Keepers GA, Fochtmann LJ, Anzia JM, Benjamin S, Lyness JM, Mojtabai R, et al. The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2020; 177(9):868–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fauci AS, Redfield RR, Sigounas G, Weahkee MD, Giroir BP. Ending the HIV Epidemic: A Plan for the United States. JAMA 2019; 321(9):844–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hanna DB, Buchacz K, Gebo KA, Hessol NA, Horberg MA, Jacobson LP, et al. Trends and disparities in antiretroviral therapy initiation and virologic suppression among newly treatment-eligible HIV-infected individuals in North America, 2001–2009. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 56(8):1174–1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thompson A, Silverman B, Dzeng L, Treisman G. Psychotropic medications and HIV. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 42(9):1305–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Himelhoch S, Brown CH, Walkup J, Chander G, Korthius PT, Afful J, et al. HIV patients with psychiatric disorders are less likely to discontinue HAART. AIDS 2009; 23(13):1735–1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cook JA, Cohen MH, Burke J, Grey D, Anastos K, Kirstein L, et al. Effects of depressive symptoms and mental health quality of life on use of highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-seropositive women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2002; 30(4):401–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tegger MK, Crane HM, Tapia KA, Uldall KK, Holte SE, Kitahata MM. The effect of mental illness, substance use, and treatment for depression on the initiation of highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected individuals. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2008; 22(3):233–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yun LW, Maravi M, Kobayashi JS, Barton PL, Davidson AJ. Antidepressant treatment improves adherence to antiretroviral therapy among depressed HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2005; 38(4):432–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Parisi CE, Varma DS, Wang Y, Vaddiparti K, Ibanez GE, Cruz L, et al. Changes in Mental Health Among People with HIV During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Qualitative and Quantitative Perspectives. AIDS Behav 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Collaborators C-MD. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2021; 398(10312):1700–1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1: Flow chart of study population selection

Supplemental Figure 2: Venn diagram of mental health multimorbidity among people with HIV between 2016–2018 (N=64,864).

Depression and bipolar disorder are considered mutually exclusive; therefore, depression diagnoses were excluded among those with bipolar disorder.

Data Availability Statement

Complete data for this study cannot be publicly shared because of legal and ethical restrictions. The NA-ACCORD Principals of Collaboration requires submission and approval of a concept sheet that describes the intended research project for which data are being requested. The NA-ACCORD Executive Committee and the Steering Committee (composed of principle investigators of contributing cohorts) must approve the concept sheet and elect to have their data included for the research project. A signed Data User Agreement is required before data can be released. Guidance for how to obtain NA-ACCORD data are outlined on the NA-ACCORD website (www.naaccord.org/collaboration-policies).