Abstract

BACKGROUND

Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome is an uncommon yet serious adverse drug hypersensitivity reaction with the presentations including rash, fever, lymphadenopathy, and internal organ involvement. Sarcoidosis is a systematic granulomatous disease with unknown etiology. We herein report a case of pulmonary sarcoidosis secondary to allopurinol-induced DRESS.

CASE SUMMARY

A 37-year-old man with a history of hyperuricemia was treated with allopurinol for three weeks at a total dose of 7000 milligrams before developing symptoms including anorexia, fever, erythematous rash, and elevated transaminase. The patient was diagnosed with DRESS and was treated with prednisone for 6 mo until all the symptoms completely resolved. Three months later, the patient presented again because of a progressively worsening dry cough. His chest computed tomography images showed bilateral lung parenchyma involvement with lymph node enlargement, which was confirmed to be nonnecrotizing granuloma by pathological examination. Based on radiologic and pathological findings, he was diagnosed with sarcoidosis and was restarted on treatment with prednisone, which was continued for another 6 mo. Reexamination of chest imaging revealed complete resolution of parenchymal lung lesions and a significant reduction in the size of the mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes. Following a 6-month follow-up of completion of treatment, the patient's clinical condition remained stable with no clinical evidence of relapse.

CONCLUSION

This is the first case in which pulmonary sarcoidosis developed as a late complication of allopurinol-induced DRESS. The case indicated that the autoimmune reaction of DRESS may play an important role in the pathogenesis of sarcoidosis.

Keywords: Pulmonary sarcoidosis, Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms, Autoimmune sequelae, Allopurinol, Case report

Core Tip: Sarcoidosis is a clinical challenge due to its less understood etiology and heterogeneous manifestations in most cases. Here, we report a unique case of pulmonary sarcoidosis that developed as a prolonged symptom of allopurinol-induced drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS). The case indicated that the autoimmune reaction of DRESS may play an important role in the pathogenesis of sarcoidosis.

INTRODUCTION

Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome, also known as drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DIHS), is an uncommon but serious adverse drug hypersensitivity reaction characterized by rash, fever, and lymphadenopathy. Allopurinol and phenytoin are the two most commonly reported drugs that cause DRESS, and the symptoms usually appear approximately 3 to 8 wk after exposure to the offending drug[1-3]. Along with the early onset symptoms reported above, some prolonged symptoms of DRESS, such as thyroid diseases, diabetes mellitus, systemic lupus erythematosus, arthritis, alopecia, and vitiligo, have been recognized as autoimmune diseases of DRESS with unknown immunological mechanisms[4,5].

Sarcoidosis remains a clinical challenge due to its unknown etiology and heterogeneity manifestations caused by the characteristic formation of noncaseating granulomas in different organs. Many risk factors for sarcoidosis have been identified, such as genetic predisposition, granulomatous infection, environmental risk factors, and obesity. However, for most cases, the causes of sarcoidosis are still under revealed. The pathogenesis of sarcoidosis is still not fully understood, but theories suggest that an activated inflammatory cascade triggered by excitatory substances leads to granulomatous inflammation, followed by fibrosis and scarring. The diagnosis of sarcoidosis is based on consistent clinical and radiologic findings, or pathological evidence of noncaseating granulomas, and exclusion of other diseases with similar findings[6,7].

We report a unique case of pulmonary sarcoidosis, which was a prolonged complication of allopurinol-induced DRESS. This report highlights the important role of hypersensitive reactions in pathogenesis of sarcoidosis. Chest computed tomography (CT) is a useful tool for the early detection of chest abnormalities, especially in those patients who have obscure symptoms.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 37-year-old male was hospitalized due to a progressively worsening cough for 14 days.

History of present illness

A 37-year-old male was hospitalized due to a severe cough that worsened over 14 days. He denied symptoms such as fever, expectoration, dyspnea, hemoptysis, recent weight loss, and extrathoracic symptoms.

History of past illness

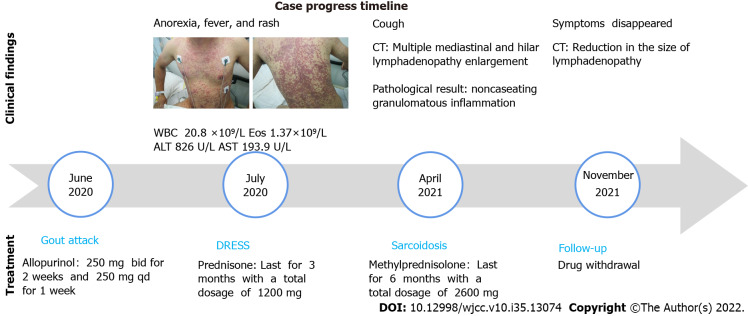

Approximately nine months prior to presentation, the patient was diagnosed with hyperuricemia and was treated with allopurinol (250 mg BID for two weeks and 250 mg QD for one week). He rapidly developed severe symptoms three weeks later, including anorexia, a fever (with a maximum body temperature of 39.5 ℃), and a rash (Figure 1). He was found to have an elevated white cell count of 20.8 × 109/L (3.5-9.5 × 109/L), eosinophil cell count of 1.37 × 109/L (0.02-0.52 × 109/L), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level of 826 U/L (9-50 U/L) and glutamic oxalacetic transaminase (AST) level of 193.9 U/L (15-40 U/L). The patient was diagnosed with an allopurinol-induced drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) and was treated with prednisone for more than three months with a total dosage of 1200 mg. The rash gradually subsided, and the blood test results returned to normal.

Figure 1.

Case progress timeline. The patient’s images after the administration of allopurinol: Erythematous rash eruption with bleeding points around the chest, the dorsal and lower extremities.

Personal and family history

The patient had no family or genetic disease history.

Physical examination

On physical examination, the vital signs were as follows: body temperature, 36.5℃; heart rate, 88 beats per min; respiratory rate, 20 breaths per min; blood pressure, 120/80 mmHg. Dark black pigmentation was observed on the chest and the dorsal. Other physical examinations were unremarkable.

Laboratory examinations

The patient’s uric acid (UA) was 541 umol/L (208-428 umol/L), routine blood, c-reactive protein level, electrolyte panel, liver function studies, renal function tests, coagulation profile, and autoantibody profile were all within normal limits. His Mycobacterium tuberculosis T cell spot (T-SPOT.TB) test was 0, and his sputum was negative for acid-fast bacilli.

Imaging examinations

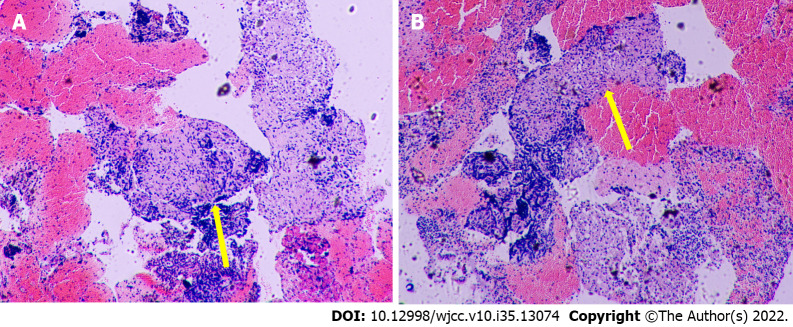

A chest CT scan was performed before the patient presented to our hospital, and it showed bilateral lung involvement, manifesting as diffuse lesions with multiple mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy enlargement (Figure 2). The results of the lung function tests were as follows: FVC (pred %) 108.6, FEV1 (pred %) 97, FEV1/FVC 74.56, and DLco (pred %) 103.4. Transbronchial lung biopsy (TBLB) and EBUS-guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) were performed in our hospital. The pathologic findings showed noncaseating granulomatous inflammation, and special staining tests, including periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining, periodic acid-silver methenamine (PASM), and acid-fast (Ziehl) staining, were negative (Figure 3). No microbial findings or malignant neoplasms were identified.

Figure 2.

Chest computed tomography. A-F: On admission, the patient’s chest computed tomography (CT) revealed multiple pulmonary nodules and mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy enlargement; G-L: The chest CT reexamination after six months of drug withdrawal revealed a resolution of the pulmonary nodules and a reduction in the size of the mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy.

Figure 3.

Pathologic findings. A: Right lower paratracheal pulmonary lymph node biopsy; B: Subcarinal pulmonary lymph node biopsy. H&E stain: Hematoxylin and eosin stain. 4× field of Hematoxylin and Eosin stain with a noncaseating granuloma (yellow arrow).

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Based on the radiologic and pathological findings, the diagnosis of sarcoidosis was established.

TREATMENT

The patient was treated with methylprednisolone for another six months with a total dose of 2600 mg (starting at a dose of 40 mg daily with a gradual reduction of the dose). Three months after treatment, chest CT showed resolution of the pulmonary nodules and a reduction in the size of the mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy. Six months later, the patient’s symptoms had diminished, and the treatment was discontinued.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

Six months after drug withdrawal, the chest CT was re-examined and showed no remarkable changes compared with that before drug withdrawal, indicating that the patient's sarcoidosis was still in remission (Figure 2).

DISCUSSION

The current case suggests a potential relationship between DRESS and pulmonary sarcoidosis. The patient had a medical history of 3 wk of treatment with allopurinol and typical symptoms of fever, dermatitis, and hematologic abnormalities that fulfilled the diagnostic criteria of DRESS (RegiSCAR scoring system[8]). He gradually developed a cough after the cessation of DRESS treatment. After all the other causes of granulomas had been ruled out, sarcoidosis was diagnosed based on the evidence of chest radiographic findings and noncaseating granulomas on biopsy[6].

The differential diagnoses of noncaseating granulomas are briefly listed below[9,10]: (1) Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis (HP): The hilar lymph nodes are not affected, and granulomas are mainly located in the peribronchiolar region. Due to the predominance of CD8+ suppressor lymphocytes in HP, bronchoalveolar lavage can provide some diagnostic basis; (2) Chronic Beryllium Disease (CBD) and Silicosis: CBD is usually referred to as “sarcoidosis of known cause”. It is important to take an accurate exposure and occupational history to exclude conditions such as berylliosis or silicosis; (3) The sarcoid-like reaction: Noncaseating granulomas may be seen in a number of settings, including malignancy (e.g., solid neoplasm, Hodgkin’s disease, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma), drug toxicity and subsequent medical device implantation; and (4) Common variable immunodeficiency (CVID): The presence of low serum immunoglobulin levels, a history of recurrent infection, the presence of areas of organizing pneumonia and follicular bronchiolitis may be helpful in the diagnosis. Our patient did not meet the abovementioned criteria and was finally diagnosed with pulmonary sarcoidosis.

There may still be arguments about whether the cause of sarcoidosis in this particular patient was DRESS. The fact that it happened chronologically over a short period prevents us from ruling out DRESS as the culprit of sarcoidosis, and there is much evidence that DRESS has both rapid onset and delayed onset clinical manifestations. Therefore, a proper history review is necessary to determine the potential causality between clinical situations.

The current literature has reported that sarcoidosis is probably the result of immune responses to genetic features, infections (e.g., mycobacteria, propionibacteria, and herpes zoster), and various environmental triggers (inorganic particles, insecticides, and moldy environments)[7]. Meanwhile, the association between drug exposure and sarcoidosis-like reactions has been documented. TNF-alpha antagonists, interferon or peg-interferon therapeutics, and immune checkpoint inhibitors[11] are related to drug-induced sarcoidosis. The immunopathological mechanism plays an important role in the development and accumulation of granulomas in sarcoidosis, which includes CD4+ T cells interacting with antigen-presenting cells and secreting a wide range of chemokines such as interleukin 2 (IL-2), tumor necrosis factor α(TNF-α), and interferon γ (IFN-γ)[7]. This case emphasizes that the causative inducing factors of sarcoidosis can also be causing the syndrome of DRESS and are not necessarily due to long-term exposure to such special drugs.

The pathogenesis of DRESS has yet to be elucidated and encompasses a range of mechanisms, including (1) specific HLA alleles (e.g., HLA-B*58:01 and allopurinol-induced SCARs[12] and HLA-B*15:02 and carbamazepine-induced SJS/TEN); (2) virus reactivation (HHV-6, HHV-7, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), and CMV)[13]; and (3) T-cell-mediated delayed hypersensitivity reactions that target multiple organs and amplify inflammatory responses[14].

DRESS patients are at risk for long-term autoimmune sequelae, including thyroid diseases, type I diabetes mellitus, systemic lupus erythematosus, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, and so forth[4,5,15-17]. However, the potential mechanism of long-term autoimmune diseases in DRESS remains incompletely defined. Several attempts have been made to clarify this mechanism. For example, a recent study reported that higher IFN-γ-induced protein (IP)-10 Levels were contributed to the development of long-term sequelae in DRESS patients[18]. Furthermore, Komatsu et al[19] found that serum levels of IP-10 were significantly higher in sarcoidosis patients, and IP-10 was associated with granuloma formation by facilitating the migration and activation of Th1 cells[20]. Therefore, we decided that pulmonary sarcoidosis can occur as a novel sequelae of DRESS.

CONCLUSION

The current case emphasizes the potential role of DRESS-induced immune abnormalities in the pathogenesis of sarcoidosis. As pulmonary sarcoidosis usually shows no specific clinical symptoms, chest CT scans may still need to be conducted periodically during the follow-up period of DRESS. Glucocorticoid therapy should be reintroduced when symptoms occur and chest CT reveals an abnormal change in sarcoidosis because, at this time, hormone therapy is still effective. The patient may completely recover with prompt treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the patient for providing consent to publish this case report.

Footnotes

Informed consent statement: All study participants, or their legal guardian, provided informed written consent prior to study enrollment.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised following the CARE Checklist (2016).

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: September 14, 2022

First decision: November 4, 2022

Article in press: November 23, 2022

Specialty type: Respiratory system

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Chowdhury D, United Kingdom; Paparoupa M, Germany S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Ma YJ

Contributor Information

Yu-Qi Hu, Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Beijing Chao-Yang Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing 100020, China.

Chen-Yang Lv, Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Beijing Chao-Yang Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing 100020, China; Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, The First Hospital of Fangshan District, Beijing 102499, China.

Ai Cui, Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Beijing Chao-Yang Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing 100020, China. cuiai@ccmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Gottlieb M, Figlewicz MR, Rabah W, Buddan D, Long B. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms: An emergency medicine focused review. Am J Emerg Med. 2022;56:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2022.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shiohara T, Mizukawa Y. Drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DiHS)/drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): An update in 2019. Allergol Int. 2019;68:301–308. doi: 10.1016/j.alit.2019.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolfson AR, Zhou L, Li Y, Phadke NA, Chow OA, Blumenthal KG. Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS) Syndrome Identified in the Electronic Health Record Allergy Module. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7:633–640. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2018.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen YC, Chang CY, Cho YT, Chiu HC, Chu CY. Long-term sequelae of drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms: a retrospective cohort study from Taiwan. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:459–465. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kano Y, Tohyama M, Aihara M, Matsukura S, Watanabe H, Sueki H, Iijima M, Morita E, Niihara H, Asada H, Kabashima K, Azukizawa H, Hashizume H, Nagao K, Takahashi H, Abe R, Sotozono C, Kurosawa M, Aoyama Y, Chu CY, Chung WH, Shiohara T. Sequelae in 145 patients with drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome/drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms: survey conducted by the Asian Research Committee on Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reactions (ASCAR) J Dermatol. 2015;42:276–282. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.12770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iannuzzi MC, Rybicki BA, Teirstein AS. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2153–2165. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra071714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spagnolo P, Rossi G, Trisolini R, Sverzellati N, Baughman RP, Wells AU. Pulmonary sarcoidosis. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6:389–402. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30064-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kardaun SH, Sidoroff A, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Halevy S, Davidovici BB, Mockenhaupt M, Roujeau JC. Variability in the clinical pattern of cutaneous side-effects of drugs with systemic symptoms: does a DRESS syndrome really exist? Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:609–611. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernardinello N, Petrarulo S, Balestro E, Cocconcelli E, Veltkamp M, Spagnolo P. Pulmonary Sarcoidosis: Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis. Diagnostics (Basel) 2021;11 doi: 10.3390/diagnostics11091558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tana C, Donatiello I, Caputo A, Tana M, Naccarelli T, Mantini C, Ricci F, Ticinesi A, Meschi T, Cipollone F, Giamberardino MA. Clinical Features, Histopathology and Differential Diagnosis of Sarcoidosis. Cells. 2021;11 doi: 10.3390/cells11010059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen Aubart F, Lhote R, Amoura A, Valeyre D, Haroche J, Amoura Z, Lebrun-Vignes B. Drug-induced sarcoidosis: an overview of the WHO pharmacovigilance database. J Intern Med. 2020;288:356–362. doi: 10.1111/joim.12991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hung SI, Chung WH, Liou LB, Chu CC, Lin M, Huang HP, Lin YL, Lan JL, Yang LC, Hong HS, Chen MJ, Lai PC, Wu MS, Chu CY, Wang KH, Chen CH, Fann CS, Wu JY, Chen YT. HLA-B*5801 allele as a genetic marker for severe cutaneous adverse reactions caused by allopurinol. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:4134–4139. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409500102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miyashita K, Miyagawa F, Nakamura Y, Ommori R, Azukizawa H, Asada H. Up-regulation of Human Herpesvirus 6B-derived microRNAs in the Serum of Patients with Drug-induced Hypersensitivity Syndrome/Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:612–613. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miyagawa F, Asada H. Current Perspective Regarding the Immunopathogenesis of Drug-Induced Hypersensitivity Syndrome/Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DIHS/DRESS) Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22 doi: 10.3390/ijms22042147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aota N, Hirahara K, Kano Y, Fukuoka T, Yamada A, Shiohara T. Systemic lupus erythematosus presenting with Kikuchi-Fujimoto's disease as a long-term sequela of drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome. A possible role of Epstein-Barr virus reactivation. Dermatology. 2009;218:275–277. doi: 10.1159/000187619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cho YT, Yang CW, Chu CY. Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS): An Interplay among Drugs, Viruses, and Immune System. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18 doi: 10.3390/ijms18061243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morito H, Ogawa K, Kobayashi N, Fukumoto T, Asada H. Drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome followed by persistent arthritis. J Dermatol. 2012;39:178–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2011.01236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang CW, Cho YT, Hsieh YC, Hsu SH, Chen KL, Chu CY. The interferon-γ-induced protein 10/CXCR3 axis is associated with human herpesvirus-6 reactivation and the development of sequelae in drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:909–919. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Komatsu M, Yamamoto H, Yasuo M, Ushiki A, Nakajima T, Uehara T, Kawakami S, Hanaoka M. The utility of serum C-C chemokine ligand 1 in sarcoidosis: A comparison to IgG4-related disease. Cytokine. 2020;133:155123. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2020.155123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Narumi S, Hamilton TA. Inducible expression of murine IP-10 mRNA varies with the state of macrophage inflammatory activity. J Immunol. 1991;146:3038–3044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]