Abstract

We have previously demonstrated that Chlamydia pneumoniae accelerates plaque formation in apolipoprotein E-deficient (ApoE−/−) mice following intranasal inoculations. In this study, we evaluated the effect of respiratory tract infection with Chlamydia trachomatis on the progression of atherosclerosis in ApoE−/− mice. The study showed that in contrast to infection with Chlamydia pneumoniae, infection of the lung and aorta with C. trachomatis was mild and transient and did not significantly accelerate plaque development.

An association of Chlamydia pneumoniae and atherosclerosis has been well documented by seroepidemiological studies (13) and detection of the organism in atherosclerotic lesions (5, 7, 12). Recent studies with animal models have shown that C. pneumoniae may play a pathogenic role in atherosclerosis. Muhlestein et al. demonstrated that C. pneumoniae infection accelerated plaque development in New Zealand White rabbits with diet-induced hyperlipidemia and that azithromycin treatment prevented the atherogenic effect of C. pneumoniae (11). Hu et al. showed that C. pneumoniae infection also accelerated plaque development in low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-receptor knockout mice fed an atherogenic diet (3). The atherogenic effect was specific to C. pneumoniae; infection with the mouse strain of Chlamydia trachomatis did not produce a similar effect. It has previously been reported that C. pneumoniae infection accelerated plaque development in apolipoprotein E-deficient (ApoE−/−) mice with genetically induced hyperlipidemia (9). In the current study, we evaluated the atherogenic effect of the human strain of C. trachomatis in ApoE−/− mice.

Eight-week-old male pathogen-free ApoE−/− mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, Maine). Four mice were kept per filter-top cage. Mice were fed a regular chow diet and water ad libitum throughout the study. They were mildly sedated by intraperitoneal injections of a mixture of ketamine (Fort Dodge Laboratories, Shenandoah, Iowa) and xylazine (Lloyd Laboratories, Shenandoah, Iowa) and were inoculated intranasally with 3 × 107 inclusion-forming units of C. trachomatis (E/UW-5/OT) at 8, 9, and 10 weeks of age, the same dosage and inoculation schedule used in previous studies with C. pneumoniae (9). The organism was grown in HeLa 229 cells and purified by density gradient centrifugation using diatrizoate meglumine (Hypaque-76; Winthrop-Breon Laboratories, New York, N.Y.) (6). The purified organism was resuspended in sucrose phosphate glutamic acid chlamydial transport medium and frozen at −70°C until use. Control mice were sham inoculated with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Mice were heavily sedated (Avertin, 2,2,2-tribromoethanol; Aldrich, Milwaukee, Wis.), and blood was collected by exsanguination from the femoral arteries at necropsy into a heparinized tube.

Perfusion fixation of the hearts and aortas was performed using 10% buffered formalin administered through the left ventricle. The heart and aorta with its main branches were dissected intact, and the aorta was cleaned of surrounding adventitial tissue. The aortic arch was separated from the heart at the level of the aortic sinus and from the rest of the aorta immediately distal to the first intercostal artery. For PCR analysis, in a separate group of mice, hearts and aortas were perfused with PBS through the left ventricle. Lungs and thoracic and abdominal aortas were removed with a separate set of sterile instruments for each tissue, placed in sterile glass vials, and immediately placed on ice and later frozen at −70°C. The segments of the aortic arches were opened longitudinally along the outer curvature and pinned flat onto black wax. The inner curvature of the aortic arch was chosen for analysis because of the consistency of lesion formation and ease of visualization. These lesions are clearly distinct from lesions associated with ostia along the outer curvature of the aortic arch. The aortas were covered with PBS and illuminated with a dual halogen fiber-optic system. Images of each aortic arch were captured with a high-resolution video camera attached to a stereomicroscope and stored in digital format. En face measurements were then performed using computer-assisted morphometry (Optimas 5.2; Optimas Corp., Bothell, Wash.). All measurements were done in a blind fashion with the investigator unaware of the group of the specimen.

PCR detection of DNA was used for assessment of infection because isolation becomes negative in the chronic stage of infection, while DNA may be detectable by PCR (10). Tissue samples were homogenized, and DNA was extracted as previously described (10). DNA samples were amplified using C. trachomatis-specific primers KL1 and KL2 (8). The amplification product was analyzed for the C. trachomatis-specific DNA sequence by gel electrophoresis through a 1.5% agarose gel according to standard methods (14) and was transferred by Southern blot to a nylon membrane (Qiagen, Chatsworth, Calif.). DNA probes were labeled using the Genius DNA labeling and detection kit. Controls for each amplification consisted of serial dilutions of purified C. trachomatis DNA as positive controls and sterile water (Baxter Healthcare, Deerfield, Ill.) in place of sample DNA as a negative control. Plasma was separated from heparinized blood and frozen at −70°C for serology and lipid measurements.

C. trachomatis-specific antibody titers were determined by the microimmunofluorescence test using formalin-fixed elementary bodies of the same strain as the antigen (15). Antibodies were measured using heavy-chain-specific fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin M (IgM) and IgG (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.). Plasma was titrated for antibodies by serial twofold dilutions. Total plasma cholesterol and triglyceride levels were measured using a commercial enzymatic test kit (Sigma). Measurements were done in triplicate and averaged. Data were expressed as means ± standard errors of the means (SEM). Group data were analyzed by Student's unpaired t test. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Animals were used in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide to the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and the study was approved by the University of Washington Animal Care Committee.

No obvious clinical signs of infection were noted in any of the animals; no mortality was observed. There were no significant differences between the infected and control mice in body weights and serum cholesterol and triglyceride levels (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Body weights and serum lipid profiles of inoculated and control mice

| Age (wk)a | Body wt (g) | Level (mg/dl) of:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Cholesterol | Triglyceride | ||

| 16 | |||

| Infected (n = 20) | 28.4 ± 2.5b | 365 ± 78 | 110 ± 39 |

| Control (n = 20) | 28.6 ± 2.3 | 332 ± 62 | 98 ± 34 |

| 20 | |||

| Infected (n = 25) | 28.7 ± 2.2 | 336 ± 74 | 92 ± 30 |

| Control (n = 18) | 29.4 ± 2.0 | 328 ± 69 | 88 ± 25 |

Differences between infected and control mice in body weights and cholesterol and triglyceride levels were not statistically significant.

Mean ± standard deviation.

PCR was positive in all lungs and in a few aortas during the acute stage, indicating that infection and dissemination had taken place (Table 2). However, chlamydial DNA was no longer detected during the chronic stage, indicating that the organism did not persist. All tissues from control mice tested negative by PCR analysis 3 days (n = 3), 1 week (n = 7), 6 weeks (n = 3), and 10 weeks (n = 7) after the third inoculation.

TABLE 2.

PCR detection of infection with C. trachomatis in the lungs and aorta of ApoE−/− mice inoculated intranasally 3 times at 8, 9, and 10 weeks of age

| Time postinfectiona | No. positive/no. testedb of:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Lungs | Thoracic aorta | Abdominal aorta | |

| 3 days | 5/5 | 2/5 | 2/5 |

| 1 wk | 6/8 | 1/8 | 0/8 |

| 6 wk | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 |

| 10 wk | 0/9 | 0/9 | 0/9 |

After the third inoculation.

Control mice tested at each interval (n, between 3 and 7) were all negative in both lungs and aortas.

All infected 16- and 20-week-old mice seroconverted after the repeated inoculations, indicating that all inoculated mice were infected. Serum IgM titers against C. trachomatis ranged from 1:64 to 1:128 at 16 weeks and from 1:32 to 1:64 at 20 weeks of age. Serum IgM titers were detected in two out of five mice at 3 days and in three out of eight mice at 1 week (range, 1:8 to 1:32) after the inoculations. All sera from the control animals remained antibody negative.

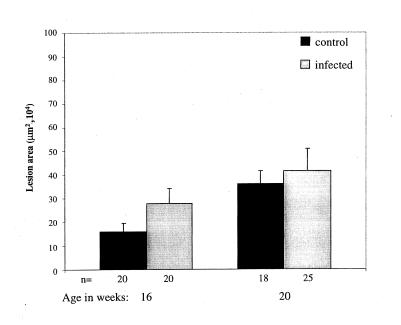

A transient mild effect of infection on the progression of atherosclerosis was observed. At 16 weeks of age, infected mice demonstrated an increase in plaque size (160,005 ± 35,729 μm2 [n = 20] [control] versus 277,200 ± 65,375 μm2 [n = 20, P = 0.11] [infected]) which was not observed at 20 weeks of age (360,991 ± 52,484 μm2 [n = 18] versus 415,436 ± 91,765 μm2 [n = 25, P = 0.64]) (Fig. 1). However, the increase at 16 weeks of age was not statistically significant.

FIG. 1.

C. trachomatis infection did not accelerate atherosclerotic lesion development in ApoE−/− mice. Mice were inoculated intranasally three times with 3 × 107 inclusion-forming units of C. trachomatis (E/UW-5/Cx) per mouse at 8, 9, and 10 weeks of age. Control mice were sham inoculated with saline. The en face lesion area in the aortic arch was measured by computer-assisted morphometry. Bars indicate means ± standard errors of the means.

Infection with the human biovar of C. trachomatis causes less severe and more rapidly resolving respiratory pathology than does infection with C. pneumoniae. After a single inoculation of C. trachomatis in Swiss Webster mice, lung infection and inflammatory changes are cleared within 2 weeks (4). A similar lung pathology was observed with ApoE−/− mice. Mild infiltrates were observed at day 3 and cleared by 2 weeks (data not shown). In contrast in Swiss Webster mice, C. pneumoniae caused inflammatory changes for up to 60 days and resolution of viable organisms from lung tissue was possible 42 days after infection (16). In ApoE−/− mice, chlamydial DNA could be detected by PCR in 7 (58%) out of 12 lungs of mice sacrificed between 6 and 16 weeks after repeated inoculations with C. pneumoniae (10), a time frame in which in the present study C. trachomatis was no longer detected in lung tissue.

Both C. trachomatis and C. pneumoniae infections disseminate from lungs to aorta. However, only C. pneumoniae establishes persistent infection in atherosclerotic lesions in mice (10). Specifically, chlamydial DNA was detected in 9 (75%) of 12 aortas of ApoE−/− mice after 6 weeks following C. pneumoniae infection. In contrast, C. trachomatis causes only short infection of aortas. Importantly, C. pneumoniae, but not C. trachomatis, has been demonstrated in atherosclerotic tissue in humans (5, 7, 12).

In the present study, C. trachomatis did not have significant effects on the development of atherosclerosis in hyperlipidemic ApoE−/− mice. This is in contrast to the results of the evaluation of C. pneumoniae in the same mouse model, where infection resulted in significantly larger lesions at both 16 (1.6-fold increase, P < 0.05) and 20 (2.3-fold increase, P < 0.05) weeks of age (9). Findings of the present study, using a human serovar of C. trachomatis, are consistent with results reported by Hu et al. in LDL-receptor knockout mice, which are prone to atherosclerosis when on a high-fat high-cholesterol diet (3). Mice on an atherogenic diet developed significantly larger lesions after repeated infections with C. pneumoniae but not after infections with the mouse biovar of C. trachomatis. In contrast, both C. pneumoniae (1) and the mouse biovar of C. trachomatis (2) induce myocardial and perivascular inflammation and fibrosis following respiratory tract infection in mice fed a normal chow diet. However, it is important to note that these cardiovascular changes are not necessarily a precursor for the development of atherosclerosis within the vascular system.

The mechanism by which chlamydial infection accelerates the progression of atherosclerosis is unknown. The effect could be indirect from lung infection via the release of proatherogenic cytokines, direct from aortic infection, or a combination of both. However, this study demonstrates that C. trachomatis, like C. pneumoniae, establishes infection of the lung and disseminates to the aorta. Unlike C. pneumoniae, C. trachomatis does not establish persistent infection of the lung or aorta or generate a sustained increase in lesion size. Thus, these results suggest that persistent infection contributes to the immunopathology of the plaque, resulting in accelerated lesion development.

Acknowledgments

We were supported by the U.S. Public Health Service (HL-56036).

We thank Anne Tecklenburg, June Zhang, and Anne Nguyen for expert technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blessing E, Lin T-M, Campbell L A, Rosenfeld M E, Lloyd D, Kuo C-C. Chlamydia pneumoniae induces inflammatory changes in the heart and aorta of normocholesterolemic C57BL/6J mice. Infect Immun. 2000;68:4765–4768. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.8.4765-4768.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fan Y, Wang S, Yang X. Chlamydia trachomatis (mouse pneumonitis strain) induces cardiovascular pathology following respiratory tract infection. Infect Immun. 1999;11:6145–6151. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.11.6145-6151.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu H, Pierce G N, Zhong G. The atherogenic effects of chlamydia are dependent on serum cholesterol and specific to Chlamydia pneumoniae. J Clin Investig. 1999;103:747–753. doi: 10.1172/JCI4582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuo C C, Chen W J. A mouse model of Chlamydia trachomatis pneumonitis. J Infect Dis. 1980;141:198–202. doi: 10.1093/infdis/141.2.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuo C C, Gown A M, Benditt E P, Grayston J T. Detection of Chlamydia pneumoniae in aortic lesions of atherosclerosis by immunocytochemical stain. Arterioscler Thromb. 1993;13:1501–1504. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.13.10.1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuo C C, Grayston J T. Interaction of Chlamydia trachomatis organisms and HeLa 229 cells. Infect Immun. 1976;13:1103–1109. doi: 10.1128/iai.13.4.1103-1109.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuo C C, Shor A, Campbell L A, Fukushi H, Patton D L, Grayston J T. Demonstration of Chlamydia pneumoniae in atherosclerotic lesions of coronary arteries. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:841–849. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.4.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mahony J B, Luinstra K E, Jang D, Sellors J, Chernesky M A. Chlamydia trachomatis confirmatory testing of PCR-positive genitourinary specimen using a second set of plasmid primers. Mol Cell Probes. 1992;6:381–388. doi: 10.1016/0890-8508(92)90031-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moazed T, Campbell L A, Rosenfeld M E, Grayston J T, Kuo C C. Chlamydia pneumoniae infection accelerates the progression of atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:238–241. doi: 10.1086/314855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moazed T, Kuo C C, Grayston J T, Campbell L A. Murine models of Chlamydia pneumoniae infection and atherosclerosis. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:883–890. doi: 10.1086/513986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muhlestein J B, Anderson J L, Hammond E H, Zhao L, Trehan S, Schwobe E, Carlquist J F. Infection with Chlamydia pneumoniae accelerates the development of atherosclerosis and treatment with azithromycin prevents it in a rabbit model. Circulation. 1998;97:633–636. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.7.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramirez J A. Isolation of Chlamydia pneumoniae from the coronary artery of a patient with coronary atherosclerosis. The Chlamydia pneumoniae/Atherosclerosis Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:979–982. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-12-199612150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saikku P, Leinonen M, Mattila K, Ekman M R, Nieminen M S, Makela P H, Huttunen J K, Valtonen V. Serological evidence of an association of a novel Chlamydia, TWAR, with chronic coronary heart disease and acute myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1988;ii:983–986. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)90741-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Vol. 1. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. pp. 6.2–6.19. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang S P, Grayston J T. Immunologic relationship between genital TRIC, lymphogranuloma venereum, and related organisms in a new microtiter indirect immunofluorescence test. Am J Ophthalmol. 1970;70:367–374. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(70)90096-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang Z P, Kuo C C, Grayston J T. A mouse model of Chlamydia pneumoniae strain TWAR pneumonitis. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2037–2040. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.2037-2040.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]