Abstract

Purpose:

This article describes the development of the LGBTQ Oncofertility Education (LOvE-ECHO). The Enriching Communication skills for Health professionals in Oncofertility (ECHO) team created this new education module in response to the needs of oncology allied health professionals to provide inclusive and affirming care to lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) AYA patients with cancer. The new module is part of the ECHO, a web-based educational training program for oncology allied health professionals to improve communication with AYA about reproductive health.

Methods:

The development of LOvE-ECHO includes five phases—learner needs assessment, content development and revision, piloting, and finalizing. Results from a survey of past ECHO learners and a comprehensive literature review provided the basis of need for this module and identified the most prominent gaps in knowledge and training. Content development and revision were iterative, including input, feedback, and voices from LQBTA youth and survivors, researchers, reproductive health experts, oncology clinicians, and web developer.

Results:

The complete LOvE-ECHO module consists of both didactic and interactive lessons. A glossary of terms and narrated PowerPoint establishes a knowledge base and shared vocabulary. Three interactive cases and a plan for action provide learners opportunities to test their new knowledge and transfer it to their practice.

Conclusion:

The module has received positive feedback to date. It is currently being piloted with new learners who complete a pre-test and post-test, as well as a feedback survey. Analysis of these results will inform revisions to the module.

Keywords: SOGI, LGBTQ, fertility, contraception, sexual health, SGM, allied health professionals

Introduction/Background

Adolescents and Young Adults (AYAs) with cancer face unique challenges compared to older adults, regarding managing their diagnosis and treatment. These obstacles are based on distinct medical and psychosocial needs due to their age and social-emotional development.1 Most practice guidelines are focused on AYA treatment, survivorship, and broadly on fertility and contraception issues, and do not address sexual health needs or assessing sexual dysfunction specific to AYAs with cancer.2,3

The importance of discussing sexual and reproductive health during treatment, and continuing these conversations post-treatment, can influence patient outcomes in a positive way by increasing patient-provider rapport, ultimately providing the patient with higher satisfaction and comfort with their care.4,5 Prior research has shown that AYAs with cancer reported uncertainty, loneliness, and unpreparedness post-treatment when discussing topics such as having a family, dating, sexual partnering, and social and emotional transitions.1,2 Conversations with AYAs with cancer early on in diagnosis and treatment may help to minimize some of these struggles and result in more positive outcomes in relationships and sexual and reproductive health.

Psychosocial experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) AYA with cancer differ from their straight and cisgender peers both during and after diagnosis, as well as treatment due to lack of inclusive and affirming care. Experiences also differ among LGBTQ AYAs based on the diversity within this population. Compared to non-LGBTQ patients, LGBTQ patient populations report lower satisfaction with cancer care treatment, higher rates of psychological distress in survivorship, and higher rates of interpreted discrimination.

Cancer patients who identify as LGBTQ are less likely to disclose their sexual identity with their provider if they do not feel like they are in a safe clinical space and if their provider lacks relevant LGBTQ knowledge and skills related to their care.6 This not only includes cancer treatment care but also sexual, reproductive, and fertility care. Training providers on how to effectively provide relevant and inclusive information to LGBTQ patients will transcend into all areas of health care and increase the overall satisfaction and outcomes of patients, especially LGBTQ AYAs with cancer.

Many disparities in LGBTQ health care and cancer care exist because of barriers to affirming and inclusive care. These intersections include patient discomfort and fear in disclosing sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) information, delaying seeking medical care due to negative past interactions with health care systems and health care professionals, and increased negative mental health risk due to societal heteronormative pressures inside and out of the clinic.4,7,8 Discomfort in seeking medical care due to stigma and discrimination correlates with increased prevalence of cancer, untreated mental health diagnoses such as anxiety, depression, substance abuse, and suicidal ideation, and the greater likelihood for LGBTQ high-risk sexual behaviors leading to sexually transmitted illnesses.7

LGBTQ AYAs with cancer are at increased risk of mental health issues, such as anxiety, depression, low self-worth and self-confidence, and negative body image based on the compounding effects of identity development in a heteronormative and cis-normative environment, and facing a cancer diagnosis and treatment at a developmentally critical age range.2,9

Compared with chronically ill adolescents, AYAs with cancer reported having fewer sexual experiences, increased risk-taking behaviors, and increased anxiety surrounding their sexuality, suggesting these experiences are specific to AYAs with cancer.2,10 AYAs often experience a disproportionate lack of health insurance coverage, which has been associated with delay in diagnosis and increased likelihood of metastasis of disease when diagnosed compared to those who are insured, ultimately increasing risk of poorer prognosis of disease.11

AYA cancer survivors are at increased risk of psychosexual development challenges in terms of sexual functioning, body and self-image, sexuality, dating, relationships, and fertility.12 LGBTQ AYAs with cancer may be at even higher risk for these psychosocial and psychosexual development risks because of the compounding effects of society's perceived sexual and gender minority identity status.12

Key systemic barriers exist in areas such as medical education, provider personal beliefs and implicit biases, and marginalization between pediatric and adult health care systems. Identifying these barriers is crucial in remodeling the structure of care to one that is inclusive and affirming for every patient.13 Lack of provider knowledge and skill relevant to adequately treat LGBTQ AYA patients is rooted in the heteronormative health care system, and institutions that train health care professionals.

Providers report not being comfortable collecting patient data that dissociates from heterosexual identity, which can disrupt patient/provider rapport and communication, and impedes the provider from delivering whole-patient care. Patients can see the discomfort in physicians' faces, and while this may be due to a lack of knowledge and skill on having conversations and patient relationships with those who identify as LGBTQ, this is experienced by patients as a negative response to who they are.4,13,14

Important skills and knowledge applicable to developing affirming and inclusive care are characterized by education on behavioral traits and actions that the health care professional can introduce into their clinical practice.13 These include modifying stereotyped language to be universal, removing assumptions of sexual orientation, gender identity and pronouns, and being mindful of potential scenarios of microaggressions, direct or indirect.15,16 Health care professionals who create environments of inclusivity and affirming care increase the positivity of their patient-provider relationships, their own confidence in the ability to provide quality, relevant care to their LGBTQ patients, and most importantly, the overall comfort of their patients.4,15,16

The Enriching Communication skills for Health professionals in Oncofertility (ECHO) is a web-based educational training program for oncology allied health professionals on communicating with patients about sexual and reproductive health. The program is designed to enhance timely communication and delivery of relevant information regarding reproductive health to AYA cancer patients. In response to the unique needs of LGBTQ AYA patients with cancer, the ECHO team created a specialty education module, the LGBTQ Oncofertility Education (LOvE-ECHO), using data inputs from a variety of sources, including survey results of former learners, a literature review, feedback from experts in AYA cancer and LGBTQ advocacy, and LGBTQ youth and AYA cancer survivors.

Methods

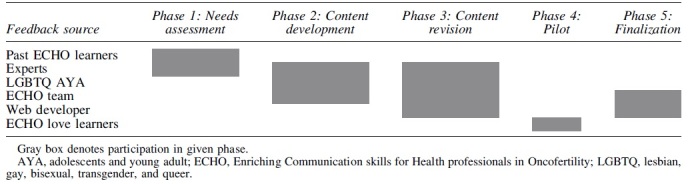

Training development was planned and implemented in 5 phases—(1) Learner Needs assessment; (2) Content development; (3) Content revision; (4) Pilot; and (5) Finalization. Phases 1 through 3 are described here. Tables 1 and 2 illustrates the groups involved in each phase and the iterative nature of this work.

Table 1.

Curriculum Development Iterations: Who Was Involved in Each Phase of Work

|

Table 2.

Development and Feedback

| Phase 2- Content development | |

|---|---|

| Experts Group and individual discussion Written input and feedback |

Content inclusion (i.e., how to create a welcoming environment, practicing cultural humility). Focus on skills and opportunity to practice informing interactive cases and action plan activity. Need for basic knowledge informing glossary and narrated PowerPoint. Focus on different types of allied health professionals. |

| LGBTQ AYA Individual and group feedback sessions |

Need for diversity in people included in cases. Mindfulness about not putting too much into one case, making it seem unrealistic. Include specific topics or issues (i.e., introductions, talking about sex not as one action, and addressing making assumptions). |

| ECHO team Team and individual discussions Written feedback |

Focus on skills and applicable knowledge. Identify resources for more information. Ensure alignment with ECHO without redundancy. |

| Web developer | Quantity of content. Select modality and tools for content delivery. Ensure alignment with ECHO and reuse of existing web frames, when possible. |

| Phase 3- Content feedback | |

| Experts Group and individual discussion Written input and feedback |

Medical accuracy to cases. (i.e., lack of practice guideline for continuation or discontinuation of gender-affirming hormones). Balance in potential responses to keep them realistic (not grossly offensive). Use the language of the professions in the slide deck and in provider responses in cases. |

| LGBTQ AYA Individual and group feedback sessions |

Suggested edits to length and content of response options (i.e., making response options more nuanced and include more questions). Word choice input on cases to ensure relevance and accessibility. Idea for topics covered in cases, including dating and sex, safer sex, and challenges of inpatient care. |

| ECHO team Team and individual discussions Written feedback |

Line edits. Review for alignment to ECHO. Keep potential responses similar in length. |

| Web developer | Ensure flow of lessons within the module. Order to lessen for ease of use in learning. Increase accessibility of knowledge. Innovative frames for new activities with broader application (i.e., drag-and-drop action plan that the learner can email to themselves). Leveraging available technology, making virtual learning an opportunity and not a limitation. |

Phase 1 needs assessment

Phase 1 included a survey of prior ENRICH/ECHO trainees to (1) identify gaps in knowledge and skills regarding inclusive and affirming care to LGBTQ AYA cancer patients and survivors; (2) assess overall comfort and confidence level requesting and discussing SOGI with LGBTQ AYA patients; and (3) determine level of need for modified and enhanced education in the ECHO program.17 The survey was developed specifically for ECHO and voluntary participants were recruited through the ECHO program. Participation did not require a specific level of experience in working with LGBTQ patients.

The survey contained 28 quantitative items and 4 open-ended items sent electronically to past ECHO learners who completed the training between 2010 and 2019 with a 51% response rate. Survey items were based on a validated survey developed for oncology physicians.18 The survey broadly assessed knowledge and confidence discussing reproductive health with LGBTQ AYA patients with cancer, and confidence in understanding reproductive health and general health needs that may differ from cisgender/heterosexual AYA.

Survey results demonstrated that only one-third of respondents believed that the ECHO program included sufficient training on the needs of LGBTQ AYA patients and survivors.17 Many respondents requested additional training regarding reproductive health for LGBTQ AYA patients and survivors. The confidence in knowledge of LGBTQ health was overall neutral, but a significantly decreased confidence was reported for bisexual/queer and transgender/nonbinary health needs. These results highlighted the need for tailored education when addressing the specific health needs of LGBTQ AYA with cancer and specifically the development of LOvE ECHO.

Literature in five areas was explored based on the areas of focus identified by the survey results, (1) disparities in LGBTQ health care and cancer care; (2) disparities in AYA cancer care; (3) barriers to affirming and inclusive care; (4) skills and knowledge for providing inclusive and affirming care; and (5) relevant theoretical frameworks and theories to inform inclusive and affirming care. There is little literature specific to providers' educational needs and experiences with LGBTQ AYAs with cancer explicit to sexual health care; however, contributions to this module were based on the literature about knowledge of increased vulnerabilities for young adults and young cancer survivors, experiences of LGBTQ cancer survivor, and sexual health needs for youth and LGBTQ adults.1,2,4,8,11

The concepts of and theories behind diversity, inclusion, and equity were the pillars of the affirming and inclusive care implementation offered in LOvE ECHO. This included practices such as recognizing diverse family and support systems, collecting SOGI data, successfully advocating for LGBTQ AYA patients, and creating culturally sensitive health care environments.16,19

Critical Race Theory and Intersectionality also served as the theoretical underpinnings. Critical Race Theory focuses on the structural forces that drive societal inequities and addresses the understanding that passive knowledge is not adequate to enact change and must be paired with both action and active knowledge.20 Intersectionality is a theoretical framework that allows health disparities to be made visible and comprehensible by understanding the various connecting identities that individuals embody.21

Viewing LGBTQ AYA oncology care through an intersectional lens allows the understanding of the multifaceted identity of patients and developing responsive, affirming, and relevant care specific to the individual patient. Critical Race Theory and Intersectionality applied to health care disparities that exist within medicine solidifies the need for systemic change on a broad spectrum and most importantly on the level of the institution and individual health care professional.21

Phases 2 and 3 content development and content revision

Experts across fields, including oncology, sexual and reproductive health, LGBTQ health, health equity, and online and adult learning, reviewed the outline and provided input toward content and structure. A multimethod, multimodule curriculum was developed. The curriculum contained both didactic and interactive modules providing multiple approaches to learning and application of learning.

Twelve LGBTQ young adults and LGBTQ AYA cancer survivors reviewed each of the cases in detail and provided feedback on the presentation, the language, and the learning opportunities presented. Individual and small group feedback sessions were held in which a member of the core development team walked the interviewees through each of the cases and documented feedback, and suggested changes and reactions to the cases and the learning opportunities they offered. Revisions were made to the cases after each of three rounds of interviews. Their feedback, along with that of the experts consulted, the web developer, and the ECHO team, is summarized below in Table 2.

Training content

The LOvE ECHO module comprises 9 lessons, including a pre-/post-test (Lessons 1 and 8) to evaluate learning and an evaluation survey (Lesson 9) to gather feedback from learners. The learning objectives for the module were as follows:

Identify disparities in health and health care for LGBTQ AYAs.

Understand barriers to affirming care and important reproductive health topics for LGBTQ AYA cancer survivors.

Learn what you can do to provide the most relevant and responsive care to AYA LGBTQ cancer survivors and use your role to address system-level barriers to quality care.

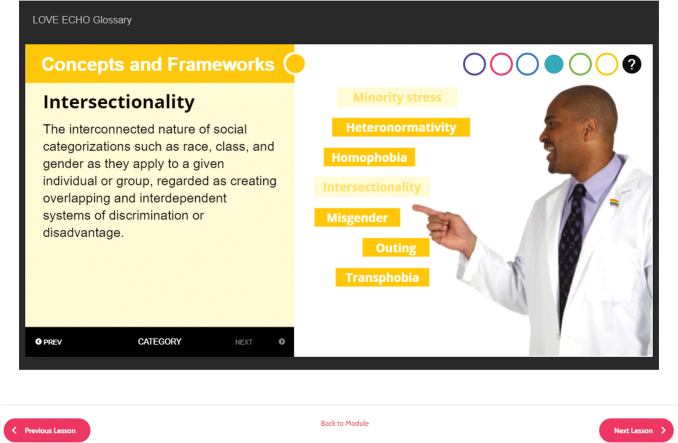

Lesson 2—Activity: interactive glossary

Following the pre-test is the interactive glossary activity in which learners select categories of terms to explore. The glossary includes six categories, each with two to seven terms. Learners select categories and terms to learn the definitions. They may be reviewed multiple times or skipped based on learner knowledge. Figure 1 is a screenshot of one of the categories in the glossary.

FIG. 1.

Glossary screenshot. Color images are available online.

Lesson 3—Lecture: disparities, barriers, and skills

This narrated PowerPoint describes disparities in care and outcomes experienced by LGBTQ AYAs in health care in general and specific to cancer care and survivorship, as well as structural and clinician-related barriers to affirming care. Understanding disparities and barriers provides the foundation for learning skills to provide inclusive and affirming care, and address barriers. The skill section begins with the basics that include practicing cultural humility, collecting SOGI data, creating a welcoming environment, and advocating for patients.

Cultural humility means recognizing that the provider does not know or understand everything from the patient's perspective and the goal is to ask questions, to not make assumptions, and to see the patient as the expert in their own identities and experiences. This differs from the concept of cultural competence in which it is believed that people can learn key features of different cultures and subsequently understand each patient's perspective.22 Skills are then presented on how to discuss sexual and reproductive health, and fertility preservation, including the topics to cover, how conversations may be distinct, and tools for communicating meaningfully.

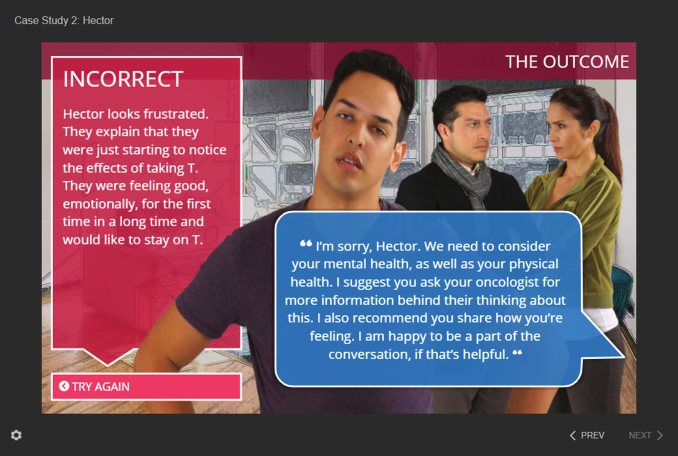

Lessons 4, 5, and 6—Interactive cases

Three interactive cases provide the learner an opportunity to practice what they have learned. The learner is introduced to an AYA LGBTQ cancer survivor, including their diagnosis and what has brought them in, followed by a specific scenario in which the learner chooses how to respond. Two different responses for each scenario are offered; one that is inclusive and affirming and one that is not. When the learner selects an option, the patient and/or caregiver response is revealed followed by an example response by the provider. Presenting the complete exchange is important for learners to understand how what they say and how they say it, may impact patients in each scenario. It also provides learners an example of how to respond when they have not treated a patient or family in an affirming or respectful manner. The series of screenshots in Figure 2 illustrate how these are displayed.

FIG. 2.

Provider response example screenshot. Color images are available online.

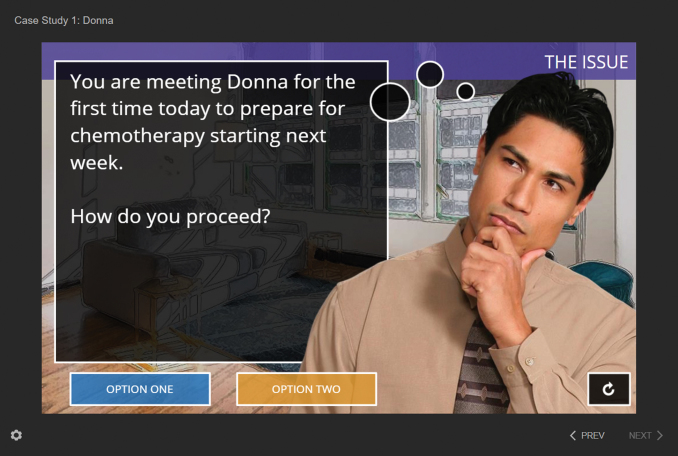

Case 1 is the shortest case with just one scenario focusing on best practices in introductions (Fig. 3). Learners meet Donna, a white cisgender woman who identifies as queer and recently had surgery for sarcoma. She is accompanied by two people at her appointment. Learners are asked how they would introduce themselves when meeting Donna for the first time. They learn to offer their name, role, and pronouns, ask both name and pronouns of the patient, and ask who is with the patient or to be introduced to those accompanying the patient without making assumptions about their relationships.

FIG. 3.

Introductions screenshot. Color images are available online.

Case 2 introduces Hector, a young Latino transman being treated for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. The learner works with Hector to navigate fertility preservation and affirming hormones after a difficult conversation with his oncologist in the first two scenarios. In the third scenario, Hector explains that he cannot continue with inpatient stays for treatment based on his last experience. The learner chooses how to handle this issue and what to say to Hector and his family.

In case 3, learners meet Horace, a young Black cisgender gay man diagnosed with colorectal cancer. Horace is about to begin intense treatment starting with surgery. Learners have the opportunity to talk about sexual health, body image, and dating in the three scenarios presented in this case. All three cases focus on the fundamentals—not making assumptions, ending heterosexual and cisgender normativity, the need for an intersectional perspective in care, and a safe environment. They each provide different opportunities for being mindful of the impact of language used and recognizing its power, practicing humility, and remembering their mission of work as allied health professionals.

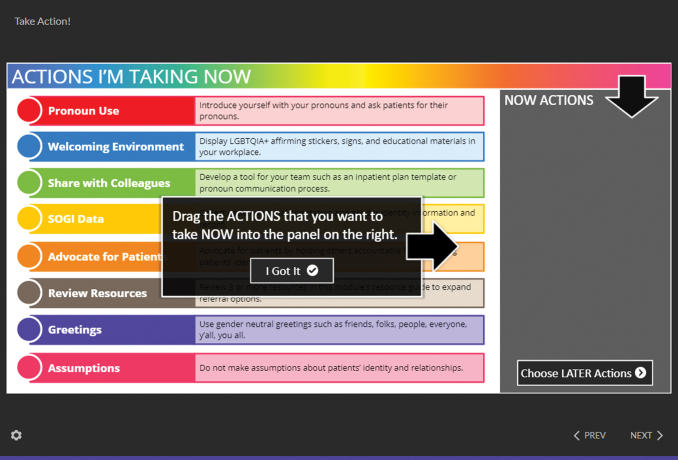

Lesson 7—Activity: take action!

Learners developed a plan for themselves to apply what they learned in the short term and the longer term. “Take Action” includes two pages of a drag-and-drop activity where learners select the actions they plan to implement “Now” and those they plan to act on “Later” as shown in Figure 4. Some items appear in both lists, while others are exclusive to the “Now” or the “Later” plan. Learners are encouraged to work on actions that are easier, requiring nothing more than their own behavior change in the short term and those requiring changes to clinic processes, system-level changes, or inspiring behavior change in others in the longer term. Compiled action plans can be emailed to the learner with one click to encourage follow-through.

FIG. 4.

Take action screenshot. Color images are available online.

Discussion

This article describes the development of a web-based training module to educate oncology health professionals on providing affirming and inclusive reproductive and sexual health care to LGBTQ AYA patients and survivors. Multiple learnings emerged through this work, including the importance for iteration, the need for diverse voices, and the challenges of representing a diverse population in a brief training, in addition to limitations of online versus in-person training. Evaluation data are currently being collected, including a pre-test and post-test focused on knowledge and skills, as well as a feedback assessment about length, breadth, depth, and relevance of the module.

As described above, development of content for the module occurred in multiple iterations. Ideas were brainstormed, outlines drafted, and reviews and edits done leading into the next draft, which was then reviewed and edited. These iterations included different members of the academic team, affiliated investigators and research staff, community members, and the programmer. Each iteration offered the opportunity for improvement in the impact of the module, the accuracy and relevance of the information, and the accessibility of the content.

Iterating with multiple people and groups requires patience and trust; it also requires knowing when to stop iterating. Writing the case studies used in the three interactive cases was an excellent example of iterating for improvement and knowing when to stop. With multiple inputs, it is possible to gather conflicting information or to iterate back to the starting point. Stepping back and reviewing all the input from multiple iterations were key in knowing when to stop and use the three cases we had developed.

Diverse voices were key in this process, including the academic team and community members providing feedback. Clinicians, research staff, researchers, young adults, and AYA cancer survivors of different sexual orientations and gender identities, races, and ethnicities, and core team members from different fields brought a broad range of perspectives, visions, and ideas to this module. Grounding this project in an intersectional perspective not only provided the space for these diverse voices but also gave the training module, especially the interactive cases, the depth required to teach this content on a web-based platform.

Asynchronous web-based training holds its own set of challenges, including (but not limited to) lack of rapport between teacher and learner, the absence of learner-to-learner interaction, inability to tailor delivery to individual learners, lack of direct communication, and question and answer. Recognizing these challenges, multiple modes for learning were included in this module that facilitated both interactive and didactic learning and included materials for learners to keep.

While challenging, this module was developed with diverse input over a relatively short period of time (6 months during the height of the coronavirus disease 2019 [COVID 19] pandemic) and resulted in a rich learning opportunity with the potential to fundamentally change the way allied health professionals provide care to LGBTQ AYA cancer patients and survivors, increasing the inclusivity and affirmative nature, therefore providing better care. The benefit of the online asynchronous learning such as ECHO was also highlighted by the pandemic.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the LGBTQ AYA who provided input and feedback to the content of this module and Rhyan Toledo for their work on the module.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

Funding for this project was supported by the National Cancer Institute/NIH with the LOvE (LGBT Oncofertility Education) ECHO Administrative Supplement to R25: Enriching Communication Skills for Health Professionals in Oncofertility (ECHO).

References

- 1. Perez GK, Salsman JM, Fladeboe K, et al. . Taboo topics in adolescent and young adult oncology: strategies for managing challenging but important conversations central to adolescent and young adult cancer survivorship. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2020;40:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Murphy D, Klosky JL, Reed DR, et al. . The importance of assessing priorities of reproductive health concerns among adolescent and young adult patients with cancer. Cancer. 2015;121(15):2529–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cherven B, Sampson A, Bober SL, et al. . Sexual health among adolescent and young adult cancer survivors: a scoping review from the Children's Oncology Group Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Discipline Committee. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):250–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Clarke M, Lewin J, Lazarakis S, Thompson K. Overlooked minorities: the intersection of cancer in lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and/or intersex adolescents and young adults. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2019;8(5):525–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bolte S, Zebrack B. Sexual issues in special populations: adolescents and young adults. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2008;24(2):115–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kamen CS, Alpert A, Margolies L, et al. . “Treat us with dignity”: a qualitative study of the experiences and recommendations of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) patients with cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(7):2525–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hafeez H, Zeshan M, Tahir MA, et al. . Health care disparities among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: a literature review. Cureus. 2017;9(4):e1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rossman K, Salamanca P, Macapagal K. A qualitative study examining young adults' experiences of disclosure and nondisclosure of LGBTQ identity to health care providers. J Homosex. 2017;64(10):1390–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cloyes KG, Candrian C. Palliative and end-of-life care for sexual and gender minority cancer survivors: a review of current research and recommendations. Curr Oncol Rep. 2021;23(4):39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Siembida EJ, Reeve BB, Zebrack BJ, et al. . Measuring health-related quality of life in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors with the National Institutes of Health Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System(®): comparing adolescent, emerging adult, and young adult survivor perspectives. Psychooncology. 2021;30(3):303–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Isenalumhe LL, Fridgen O, Beaupin LK, et al. . Disparities in adolescents and young adults with cancer. Cancer Control. 2016;23(4):424–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Aubin S, Perez S. The clinician's toolbox: assessing the sexual impacts of cancer on adolescents and young adults with cancer (AYAC). Sex Med. 2015;3(3):198–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Eliason MJ, Dibble SL. Provider-patient issues for the LGBT cancer patient. In: Boehmer U, Elk R (Eds). Cancer and the LGBT community: unique perspectives from risk to survivorship. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2015; pp. 187–202. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Murphy M. Hiding in plain sight: the production of heteronormativity in medical education. J Contemp Ethnogr. 2016;45(3):256–89. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Buchting FO, Margolies L, Bare MG, et al. LGBT Best and Promisin Practices Throughout the Cancer Continuum. LGBT HealthLink; 2015. Accessed November, 2021 from https://www.lgbthealthlink.org/projects/cancer-best-practices.

- 16. Margolies L, Scout NFN. LGBT Patient-Centered Out- comes: Cancer Survivors Teach Us How To Improve Care For All. LGBT Cancer Network; 2013. Accessed November, 2021 from https://cancer-network.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/lgbt-patient-centered-outcomes.pdf.

- 17. Quinn GP, Sampson A, Alpert AB, et al. . Clinician training needs in reproductive health counseling for sexual and gender minority AYA with cancer. Fertil Steril. 2020;114(3):e545–6. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sutter ME, Simmons VN, Sutton SK, et al. . Oncologists' experiences caring for LGBTQ patients with cancer: qualitative analysis of items on a national survey. Patient Educ Couns. 2021;104:871–876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Berner AM, Webster R, Hughes D, et al. . Education to improve cancer care for LGBTQ+ patients in the UK. Clin Oncol. 2021;33(4):270–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zewude R, Sharma M. Critical race theory in medicine. CMAJ. 2021;193(20):E739–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Damaskos P, Amaya B, Gordon R, Walters CB. Intersectionality and the LGBT cancer patient. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2018;34(1):30–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Alpert A, Kamen C, Schabath MB, et al. . What exactly are we measuring? Evaluating sexual and gender minority cultural humility training for oncology care clinicians. J Clin Oncol 2020;38(23):2605–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]