Abstract

Protein-protein interactions (PPIs) in the nucleus play key roles in transcriptional regulation and ensure genomic stability. Critical to this are histone-mediated PPI networks, which are further fine-tuned through dynamic post-translational modification. Perturbation to these networks leads to genomic instability and disease, presenting epigenetic proteins as key therapeutic targets. This mini-review will describe progress in mapping the combinatorial histone PTM landscape, and recent chemical biology approaches to map histone interactors. Recent advances in mapping direct interactors of histone PTMs as well as local chromatin interactomes will be highlighted, with a focus on mass-spectrometry based workflows that continue to illuminate histone-mediated PPIs in unprecedented detail.

Introduction

Protein-protein interactions (PPIs) regulate all essential cellular processes. One such PPI network is present in the nucleus, where accessibility of the transcription machinery to protein-encoding genes is controlled through a range of regulatory mechanisms. Eukaryotic DNA is packaged in the form of chromatin, where approximately 150 base pairs of DNA is wrapped around an octameric core of histone proteins to form the nucleosome (Fig. 1a).(1) This elegant solution to the challenge of packaging DNA into the nucleus is further fine-tuned through the post-translational modification of histone proteins (hPTMs) and modification of the DNA.(2, 3) hPTMs are present both on the extended unstructured tail regions and in the globular domains of histone proteins and range in size from the installation of a single methyl group, to the attachment of the 8.5 kDa protein ubiquitin (Fig. 1b).(4) hPTMs are installed by “writers”, interrogated by “readers” and removed by “erasers” (Fig. 1c). These modifications can elicit direct biophysical effects, or play key roles in the recruitment of chromatin-associating proteins, and correlate with active and silenced regions of the genome.(5)

Figure 1. The nucleosome and histone post-translational modifications.

a. X-ray crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle (PDB: 1kx5) displaying DNA wrapped around an octameric core of histone proteins H3, H4, H2A, H2B. b. Selected examples of histone PTM chemotypes. c. Histone PTMs are deposited by writers, interrogated by readers, and removed by erasers.

Given the importance of PPI networks within the nucleus it is perhaps unsurprising that dysregulation of such interactions, through mutation or otherwise, results in aberrant transcription and disease, including many cancers.(6) For example, subunits of the chromatin remodeling SWI-SNF (BAF) complex are mutated in approximately 20% of human cancers.(7),(8) Recently, sequencing of patient tumor samples identified >4,000 mutations to the histone proteins themselves, with a large proportion found in understudied globular domains.(9–11) Though many are likely passenger mutations, recent studies have shown that the mutations correlate with poor prognosis and could represent novel oncogenic drivers.(11) Given this clinical relevance, the accurate mapping of nuclear PPIs is critical not only to our understanding of fundamental biology, but also will aid in the identification of targets for therapeutic intervention.(12–14)

This review will highlight recent chemical biology approaches to map the combinatorial hPTM landscape and histone interacting proteins, with a particular focus on recent powerful technologies that add to the chemical biology toolbox, illuminating nuclear PPI networks with unprecedented resolution and accuracy.

The dynamic combinatorial PTM landscape

The crowded cell nucleus represents a significant challenge for the accurate mapping of PPIs. Indeed, the accurate mapping of histone-interacting proteins can only be achieved once our understanding of the hPTM landscape is complete. The quantitative mapping of hPTMs remains challenging due to the abundance of modifiable side chains (Lys, Arg, Ser, Thr, Gln, Glu, Tyr), the wide range of PTM chemotypes, and the presence of linker histones and histone variants.(15, 16) Critical to this goal is the establishment of methods that can traverse the dynamics of PTM deposition, recognition, and removal throughout the cell cycle, or as a result of external stimulus.(17)

Much of our knowledge of the hPTM landscape has been established through mass-spectrometry (MS) based workflows.(18) In recent years improvements in sample preparation, instrument sensitivity, and data processing workflows has dramatically improved the accuracy and throughput of hPTM mapping experiments.

Chemical derivatization has been used to block unmodified and mono-methylated lysine side chains (using propionic anhydride in combination with phenyl isocyanate) such that trypsin will only cleave after arginine residues, facilitating the detection of PTMs on lysine-rich histone tails.(19–21) Middle-down proteomics(22, 23) in combination with histone purification and hydrophilic interaction chromatography (HILIC) has recently become the method of choice for characterization of hPTMs, analyzing peptides roughly 20–60 amino acids in length (Fig. 2). This is achieved through the partial digestion of histone proteins using selected proteases (e.g. GluC, chymotrypsin) that retain the intact PTM-rich histone tails. Challenges remain, however, including fragmentation patterns that are difficult to assign due to the heterogeneity of modifiable residues on a given peptide sequence, as well as several PTMs returning similar mass shifts (e.g. trimethylation and acetylation).(24) Promising work deploying ion mobility such as High-Field Asymmetric Waveform Ion Mobility mass spectrometry (FAIMS) and Trapped Ion Mobility Spectrometry (TIMS) has begun to tackle such challenges.(25–27) A promising middle-down approach termed Affinity-Bead Assisted Mass Spectrometry (Affi-BAMS) was recently developed that forgoes LC and circumvents many of the challenges with LC-MS workflows.(28) Combining bead-based peptide enrichment with Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization (MALDI) MS, the workflow provides a quantitative single target readout and holds promise to deconvolute the heterogeneous PTM landscape (Fig. 2). The top-down proteomic analysis of intact mononucleosomes has also been recently reported (Nuc-MS),(29) which allows direct comparison with ChIP-seq datasets, including the co-localization of the oncogenic mutation H3K27M with euchromatic marks.

Figure 2. Mapping histone PTMs by mass spectrometry.

Mass spectrometry workflows for the quantitative analysis of selected hPTMs on histone H3 and H4 – middle-down proteomics with HILIC chromatography (left) and Affi-BAMS with MALDI-TOF MS (right).

Mapping histone interactors with affinity purification

As our understanding of the dynamic PTM landscape continues to improve, so do the chemical biology approaches to map histone-mediated PPI networks in the nucleus. The majority of early histone interactomics studies were performed using immunoprecipitation-based workflows. Affinity purification-mass spectrometry (AP-MS) targets a particular chromatin-associated protein or PTM, where selected antibodies are added to nuclear lysate or isolated nuclei and interacting proteins are identified after immunoprecipitation and mass spectrometry.(30, 31) For example, Skranja et al. recently reported a comprehensive interactome study centering around the acidic patch, a critical docking site for chromatin-interacting proteins.(32) Performing such experiments in lysate perturbs the native chromatin environment, however, and any immunoprecipitation workflow presents challenges with epitope occlusion.

Recent additions to the AP-MS toolkit include Rapid Immunoprecipitation Mass Spectrometry of Endogenous proteins (qPLEX-RIME)(33), where cells are crosslinked with disuccinimidyl glutarate and formaldehyde, followed by nuclear isolation and immunoprecipitation to identify transient PPIs of the targets of interest. The method facilitates the identification of near native-state chromatin interactomes. Augello et al. later applied qPLEX-RIME to identify CHD1 as a tumor suppressor in prostate cancer and revealing that 33% of its interactome was shared with that of H3K4me3.(34)

Local chromatin interactome mapping

Chromatin interacting proteins often exist as subunits within dynamic complexes, including ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes (e.g. SWI/SNF, 12–15 subunits, >2 MDa),(35) histone acetyltransferase complexes (e.g. p300)(36), and histone methyltransferases (e.g. MLL1 complex)(37). Accurate determination of local histone interactomes is therefore a critical goal within the field, which is further amplified as subunit composition can also be altered through mutation and correlated with disease progression.(12)

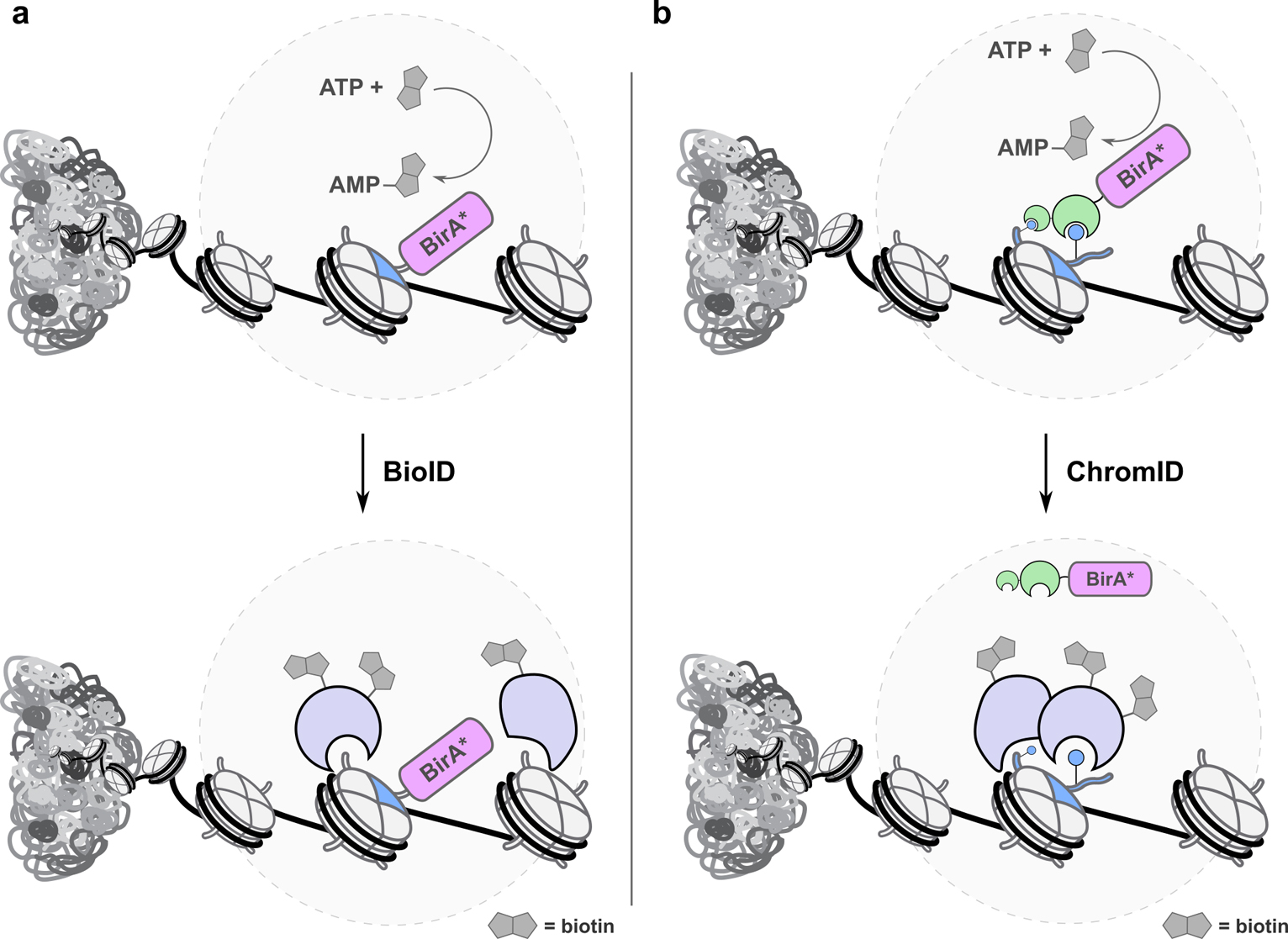

Mapping the local interactomes of histone proteins and hPTMs remains a challenge within epigenetics. Recent work, however, has mapped such networks with improved spatial and temporal control.(38–40) BioID,(41, 42) and extensions thereof (TurboID (BirA*),(43) Split BioID(44, 45)), exploit an engineered promiscuous bacterial biotin ligase (BirA) to generate biotin-AMP esters which react with proximal lysine ε-amino groups (Fig. 3a). The labeling radius for BioID is approximately 15 nm, with the initial requirement of long labeling times (>12 h) being overcome in recent years through directed evolution of BirA to generate a highly efficient biotin ligase deployed in TurboID workflows, decreasing labeling times to <10 min.(46) The technology can be paired with MS workflows, and has been used to map PPI networks across a range of cellular compartments. BioID has been transformative within chemical biology due to its ease of use and efficiency. For example, the interactome of the centromere-specific H3 variant CENP-A has been mapped, with HJURP identified as an interactor critical for CENP-A genomic retention.(47)

Figure 3. Proximity labeling in chromatin.

a. BioID uses an engineered biotin ligase (BirA*) to generate AMP-biotin esters that react with proximal lysines. When fused to a target histone (blue) and combined with quantitative proteomics workflows, local interactomes can be determined. b. ChromID fuses BirA* to selected hPTM reader domains (green), enabling local interactomes to be determined while avoiding direct fusion to histone proteins.

APEX (enhanced ascorbate peroxidase) generates biotin-phenoxy radicals in proximity to a target protein through treatment with hydrogen peroxide.(48) These radicals react with proximal tyrosine residues and interacting proteins can be identified via enrichment and MS.(49) The ascorbate peroxidase has been improved through rounds of directed evolution, allowing treatment times as short as seconds, thus providing a level of temporal control superior to that of BioID.(48) As with BioID, challenges remain, for example treatment with hydrogen peroxide is intractable in certain circumstances, perhaps most critically in investigations into DNA damage and the DNA damage response.

Though BirA and APEX can be appended directly to the N- or C-termini of histones, their molecular weight (>25 kDa) is almost double that of the histone protein under study. This also presents other challenges, for example, the free amino N-terminus of H3 is critical for engagement of a variety of interactors (e.g. the H3K4me3 reader TAF3)(50) and the C-terminus of histone H4 is buried within the nucleosome core. As a result of this, the successful deployment of such methodologies, or extensions thereof, to histone interactomics remains limited.

Given the challenges of generating histone fusion proteins, Villaseñor et al. reported Chrom-ID, which fuses BirA* to isolated histone PTM reader domains to selectively map selected regions of chromatin (e.g. enhancer regions or heterochromatin; Fig. 3b).(51) The approach was thoroughly validated by ChIP-seq and confocal microscopy using reader domain-GFP fusions. The authors then mapped a range of local chromatin interactomes exploiting reader proteins for H3K4me3 and H3K27me3, as well as mapping “bivalent” H3K4me3-H3K27me3 genomic regions with a fused TAF3-CBX7 construct. The bivalent study returned hits including the methyltransferases MLL1&2 and the histone acetyltransferase complex TIP60. The approach holds promise to map PPI networks for a range of hPTMs using natural reader domains, and could also be extended to novel targets through the use of engineered reader domains generated by rational design and/or directed evolution.(52)

In an elegant approach that exploits the availability of numerous antibodies against hPTMs, Santos-Barriopedo et al. employed BirA* fusions to protein-A as a way of performing proximity labeling at specific hPTMs. Cell permeabilization is followed by treatment with the antibody-protein-A-BirA* assembly, with the interactome of H3K9me3 determined.(53)

A recent study has applied μMap, a novel photocatalytic proximity labeling technique, to chromatin. μMap uses iridium photocatalysts to selectively activate diazirine probes within a short radius (approx. 4 nm) of the catalyst upon irradiation with blue light. Previous studies deployed μMap on cell surfaces through conjugation to selected antibodies, or through fusion to established probe molecules.(54, 55) Here, the authors determine comprehensive nucleosome interactomes by surveying the interactome of six histone proteins, along with a range of critical nuclear proteins including Cohesin, CTCF, and RNA polymerase II. Perturbations to the interactomes as a context of mutation or epigenetic drug treatment were also determined, with the presence of the cancer-associated histone mutation H2A E92K resulting in increased local acetylation and aberrant BRD2/3/4 recruitment.(56)

Mapping direct interactors of histones and histone PTMs

The challenge of mapping direct interactors of histones and hPTMs was traditionally attempted through the use of peptide or protein bait molecules, bearing selected PTMs and affinity handles (e.g. biotin). Pioneering studies using peptide probes were reported by Vermeulen at al.(57, 58) which, when combined with SILAC-based quantitative proteomics, returned hPTM interaction networks.

Experiments with short peptide probes remain somewhat removed from the native chromatin environment, however, as histone-interacting proteins often anchor to the nucleosome surface, or engage multiple nucleosome epitopes.(59, 60) This has encouraged recent extensions of this approach where PTM baits are incorporated into nucleosome substrates generated by protein semi-synthesis.(61) Native chemical ligation and expressed protein ligation are routinely used for the traceless installation of hPTMs (e.g. H3K4me3, H3K9me3 & H3K27me3) and other selected chemical moieties to protein N- and C-termini, with histone proteins amongst the most studied targets.(4, 62–64) For example, Local et al. described the semi-synthesis of H3K4me1 and H3K4me3 containing mononucleosomes and used these as baits to deconvolute the PPI networks at active genes and at enhancer elements.(65) The authors identified SWI/SNF as an H3K4me1 interactor, and showed that it more readily remodels monomethylated nucleosomes.

The emergence of UV-labile crosslinking handles in chemical biology has revolutionized the mapping of PPIs. Diazirines have become a privileged class of reagents for protein labeling since their introduction in the 1970’s.(66) Diazirines decompose upon irradiation with UV light to expel molecular nitrogen and generate a highly reactive carbene that will react with proximal proteins, nucleic acids, and other cellular components. These covalent crosslinking strategies offer advantages over the native enrichment strategies described above, particularly for the trapping of weak and transient protein-protein interactions.

Crosslinking strategies to map direct interactors of histone residues or hPTMs deploy chemical probes bearing a hPTM with an adjacent diazirine or benzoylphenylalanine (BPA) moiety, with or without an affinity handle.(67) Such peptide-based probes were used to map the interactors of H3K4me3 through combination with SILAC-based MS.(68) These experiments are performed in nuclear lysate, however, where chromatin is perturbed from its native context.

Recent studies have described modification of native chromatin in live cells and isolated nuclei using split inteins.(69–71) Such approaches allow the traceless modification of histone proteins within native chromatin. Here, the C-intein is fused to a truncated histone and the N-intein is synthesized bearing selected cargo including hPTMs, UV crosslinkers, and affinity handles. Once the N- and C-intein associate, the intein excises itself from the protein sequence and fuses the cargo to a selected histone or nuclear protein. The installation of a range of hPTMs with an adjacent diazirine moiety in isolated nuclei was reported in 2020 (Fig. 4).(69) The first in-situ chromatin interactomes for a range of hPTMs including H3K4 methylation, H3K9 methylation, and H3K27 acetylation were mapped. The approach was also extended to the cancer-associated histone mutation H3K4M, and holds promise for identifying altered interactomes for the >4,000 histone mutations identified in sequenced tumor samples.(10)

Figure 4. In-situ chromatin interactomics.

Protein trans-splicing installs a hPTM or mutation with an adjacent diazirine and biotin affinity handle. Upon UV irradiation, interacting proteins are covalently bound to the modified histone and can be identified by quantitative proteomics.

Intein splicing has also been combined with sortase-mediated enzymatic ligation to generate dually modified nucleosomes bearing PTMs on histones H3 and H2A. Combinatorial strategies enabled the generation of 280 modified nucleosomes, hinting at the possibility of future high-throughput interactomics studies.(72)

Genetic code expansion methodologies

The site-selective incorporation of hPTMs, PTM mimics, and crosslinking handles into histone proteins has been explored using genetic code expansion technologies. Such approaches require the evolution of tRNA/aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase pairs that install an unnatural amino acid of choice at the amber stop codon.(73) In the context of histone interactors, a number of acyl PTMs and crosslinking moieties have been incorporated using genetic code expansion methodologies.(74)

Kleiner et al. installed a diazirine-containing lysine derivative at selected positions within histone proteins and mapped global interactomes of histone H3 and H4 as a function of cell cycle.(75) The dual combination of a crosslinking warhead with a PTM on the same amino acid has also been reported, including crotonylated lysine with a diazirine incorporated into the lysine side chain.(76) This approach, however, carries the risk of perturbing the binding epitope for writers, readers or erasers. A powerful extension of such methodologies is to incorporate a PTM of choice with an adjacent crosslinker into chromatin. Such workflows are yet to be reported in mammalian cells, but the dual modification of histone H3 with acetyl lysine and an adjacent BPA crosslinker was reported in E. coli, and the H3K27ac-BPA modified protein was shown to engage TRIM24.(77)

Dehydroalanine residues can be generated in target proteins in live cells through the incorporation of a phosphoserine residue by genetic code expansion, or through chemical or biochemical transformations. Radical coupling can then be performed with a range of alkyl iodides to install PTMs including methylation, phosphorylation, along with a range of abiological moieties. It should be noted that such strategies erode the stereochemistry at Cα and return a mixture of epimers.(78, 79) Genetic code expansion methodologies have also been combined with sortase-mediated enzymatic ligation to site-selectively install protein ubiquitylation and SUMOylation.(80)

A complimentary strategy uses genetic code expansion methodologies to install photocrosslinking moieties into PTM reader domains, as opposed to the histone proteins themselves. Reader domains including bromodomains and chromodomains have been evaluated using this approach to map the interaction networks of BRD4 and HP1β.(81, 82)

Evolving efficient tRNA/aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase pairs that span the chemical diversity of hPTMs remains a challenge, with critical hPTMs such as trimethyl lysine currently inaccessible. Moreover, the efficient installation of multiple unnatural amino acids also represents a grand challenge in mammalian cells. Pioneering work in E. coli has hinted at the potential to incorporate two or three orthogonal unnatural amino acids to enable the study of PPI networks in live cells.(83, 84)

Future perspectives

1. The challenge of locus-specific interactomics

Each of the methods above describe the mapping of either chromatin-wide interactomes or chromatin regions that are associated with, for example, transcribed genes or silenced regions. Identifying proteins that are present at a selected gene, or genetic element (e.g. enhancers and promoters) remains challenging. If achieved, such a method would illuminate PPI networks in unprecedented detail. The most promising approaches to date deploy dCas9-mediated genomic targeting with BioID or APEX proximity labeling to map local interactomes at repetitive genomic regions such as telomeres.(85–88) Multiple dCas9 fusions are required to engage at the target loci, with locus-specific interactomics beyond the reach of existing technologies.

2. Improvements in mass-spectrometry based interactomics workflows

The vast majority of the examples highlighted in this mini-review exploit workhorse cell lines, where large amounts of protein can be readily obtained for analysis. To better understand the clinical translation to disease, such workflows must be extended to challenging cell lineages, embryos, organoids, and patient samples. This is particularly pertinent for diseases that are linked to epigenetic regulatory proteins that may only be expressed in certain cellular populations. Continuing advances in mass spectrometry hardware will aid with miniaturization of sample requirements, with concomitant improvements in sensitivity overserved through new instrumentation and the use of ultra-high throughput “fast proteomics” workflows.(89)

3. Small-molecule mediated modulation of histone interactomes

Small-molecule modulators of histone-interacting proteins have been extensively studied and applied towards treating serious diseases.(90–92) These compounds generally target histone readers, writers, or erasers, and can be used to probe how the histone interactome changes upon treatment. Indeed, efforts have been made towards combining pan-affinity matrices with chemical proteomics to interrogate the selectivity of HDAC and bromodomain inhibitors.(93, 94) With the selectivity of target engagement in hand, the next step is to use this information to determine changes in histone PTM levels and protein complex composition upon compound treatment. This can be further extended to catalogue the consequences of such changes on the global proteome and accelerate the drug discovery process. These complementary strategies are critical for generating mechanistic insights around the drivers of efficacy for lead compounds, and can identify biomarkers for detection in subsequent in vivo and clinical studies.

Conclusion

Recent work has elucidated nuclear PPI networks in unprecedented detail. The resulting chemical biology toolkit can be applied to a wide range of chromatin-associated proteins – including histone proteins, chromatin-modifying enzymes, and PTM reader domains. Combining these workflows with powerful and ever-improving MS readouts has led to dramatic improvements in data quality and accuracy. Whilst the impact of such methodologies in both academic and industrial settings is dependent on careful and well-designed validation experiments, an ever-improving arsenal of biochemical assays, functional genomics approaches, and experimental and AI-based structural biology (such as AlphaFold) is improving the throughput of hit validation.(95) Future developments will continue to push the boundaries of interactomics workflows through the deployment of novel technologies to a wider range of cell types, tissues, and patient samples, returning novel epigenetic targets for therapeutic intervention.

Perspectives.

Mapping nuclear protein-protein interactions (PPIs) represents a critical goal to understand fundamental biology and identify novel therapeutic opportunities. Pertinent to this is the accurate mapping of histone-mediated PPIs and how these are fine-tuned through post-translational modification.

The current chemical biology toolkit allows the determination of local chromatin interactomes and specific histone interactors in unprecedented detail. Local chromatin interactomes can be explored using proximity labeling techniques, with PTM-specific interactors mapped using UV-activatable crosslinking moieties.

Further developments in protein engineering and genetic code expansion methodologies will improve our ability to install PTMs and crosslinkers with chemical precision in live cells and organisms. Continuing improvements in chemical biology workflows and instrument sensitivity brings the goal of the mapping of locus-specific interactors into view. The wealth of information generated will lead to novel strategies for therapeutic intervention.

Acknowledgements

AJB was a Damon Runyon Postdoctoral Fellow of the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation (DRG-2283-17). Work in the TWM laboratory was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH grant R37-GM086868).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Luger K, Mäder AW, Richmond RK, Sargent DF, Richmond TJ. Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 Å resolution. Nature. 1997;389(6648):251–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bannister AJ, Kouzarides T. Regulation of chromatin by histone modifications. Cell Res. 2011;21(3):381–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kouzarides T Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell. 2007;128(4):693–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muller MM, Muir TW. Histones: at the crossroads of peptide and protein chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2015;115(6):2296–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Venkatesh S, Workman JL. Histone exchange, chromatin structure and the regulation of transcription. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2015;16(3):178–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharma S, Kelly TK, Jones PA. Epigenetics in cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31(1):27–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alfert A, Moreno N, Kerl K. The BAF complex in development and disease. Epigenetics Chromatin. 2019;12(1):19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kadoch C, Crabtree GR. Reversible disruption of mSWI/SNF (BAF) complexes by the SS18-SSX oncogenic fusion in synovial sarcoma. Cell. 2013;153(1):71–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bagert JD, Mitchener MM, Patriotis AL, Dul BE, Wojcik F, Nacev BA, et al. Oncohistone mutations enhance chromatin remodeling and alter cell fates. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2021;17(4):403–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nacev BA, Feng L, Bagert JD, Lemiesz AE, Gao J, Soshnev AA, et al. The expanding landscape of ‘oncohistone’ mutations in human cancers. Nature. 2019;567(7749):473–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bennett RL, Bele A, Small EC, Will CM, Nabet B, Oyer JA, et al. A Mutation in Histone H2B Represents a New Class of Oncogenic Driver. Cancer Discov. 2019;9(10):1438–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng Y, He C, Wang M, Ma X, Mo F, Yang S, et al. Targeting epigenetic regulators for cancer therapy: mechanisms and advances in clinical trials. Signal Transduc. Target. Ther. 2019;4(1):62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ganesan A, Arimondo PB, Rots MG, Jeronimo C, Berdasco M. The timeline of epigenetic drug discovery: from reality to dreams. Clin. Epigenetics. 2019;11(1):174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richards AL, Eckhardt M, Krogan NJ. Mass spectrometry-based protein–protein interaction networks for the study of human diseases. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2021;17(1):e8792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.El Kennani S, Crespo M, Govin J, Pflieger D. Proteomic Analysis of Histone Variants and Their PTMs: Strategies and Pitfalls. Proteomes. 2018;6(3):29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brockers K, Schneider R. Histone H1, the forgotten histone. Epigenomics. 2019;11(4):363–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scott WA, Campos EI. Interactions With Histone H3 & Tools to Study Them. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020;8(701). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aebersold R, Mann M. Mass-spectrometric exploration of proteome structure and function. Nature. 2016;537(7620):347–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garcia BA, Mollah S, Ueberheide BM, Busby SA, Muratore TL, Shabanowitz J, et al. Chemical derivatization of histones for facilitated analysis by mass spectrometry. Nat. Protoc. 2007;2(4):933–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maile TM, Izrael-Tomasevic A, Cheung T, Guler GD, Tindell C, Masselot A, et al. Mass spectrometric quantification of histone post-translational modifications by a hybrid chemical labeling method. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2015;14(4):1148–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sidoli S, Kori Y, Lopes M, Yuan ZF, Kim HJ, Kulej K, et al. One minute analysis of 200 histone posttranslational modifications by direct injection mass spectrometry. Genome Res. 2019;29(6):978–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu C, Coradin M, Porter EG, Garcia BA. Accelerating the Field of Epigenetic Histone Modification Through Mass Spectrometry-Based Approaches. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2020;20:100006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sidoli S, Garcia BA. Middle-down proteomics: a still unexploited resource for chromatin biology. Expert Rev. Proteomics. 2017;14(7):617–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Mierlo G, Vermeulen M. Chromatin Proteomics to Study Epigenetics — Challenges and Opportunities. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2021;20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garabedian A, Baird MA, Porter J, Jeanne Dit Fouque K, Shliaha PV, Jensen ON, et al. Linear and Differential Ion Mobility Separations of Middle-Down Proteoforms. Anal. Chem. 2018;90(4):2918–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shliaha PV, Gorshkov V, Kovalchuk SI, Schwammle V, Baird MA, Shvartsburg AA, et al. Middle-Down Proteomic Analyses with Ion Mobility Separations of Endogenous Isomeric Proteoforms. Anal. Chem. 2020;92(3):2364–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meier F, Park MA, Mann M. Trapped Ion Mobility Spectrometry and Parallel Accumulation-Serial Fragmentation in Proteomics. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2021;20:100138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hamza GM, Bergo VB, Mamaev S, Wojchowski DM, Toran P, Worsfold CR, et al. Affinity-Bead Assisted Mass Spectrometry (Affi-BAMS): A Multiplexed Microarray Platform for Targeted Proteomics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schachner LF, Jooss K, Morgan MA, Piunti A, Meiners MJ, Kafader JO, et al. Decoding the protein composition of whole nucleosomes with Nuc-MS. Nat. Meth. 2021;18(3):303–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zheng J, Chen X, Yang Y, Tan CSH, Tian R. Mass Spectrometry-Based Protein Complex Profiling in Time and Space. Anal. Chem. 2021;93(1):598–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rogawski R, Sharon M. Characterizing Endogenous Protein Complexes with Biological Mass Spectrometry. Chem. Rev. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Skrajna A, Goldfarb D, Kedziora KM, Cousins EM, Grant GD, Spangler CJ, et al. Comprehensive nucleosome interactome screen establishes fundamental principles of nucleosome binding. Nuc. Acids Res. 2020;48(17):9415–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Papachristou EK, Kishore K, Holding AN, Harvey K, Roumeliotis TI, Chilamakuri CSR, et al. A quantitative mass spectrometry-based approach to monitor the dynamics of endogenous chromatin-associated protein complexes. Nat. Commun. 2018;9(1):2311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Augello MA, Liu D, Deonarine LD, Robinson BD, Huang D, Stelloo S, et al. CHD1 Loss Alters AR Binding at Lineage-Specific Enhancers and Modulates Distinct Transcriptional Programs to Drive Prostate Tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2019;35(4):603–17.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mashtalir N, D’Avino AR, Michel BC, Luo J, Pan J, Otto JE, et al. Modular Organization and Assembly of SWI/SNF Family Chromatin Remodeling Complexes. Cell. 2018;175(5):1272–88 e20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ogryzko VV, Schiltz RL, Russanova V, Howard BH, Nakatani Y. The Transcriptional Coactivators p300 and CBP Are Histone Acetyltransferases. Cell. 1996;87(5):953–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jiang H The complex activities of the SET1/MLL complex core subunits in development and disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gene Regul. Mech. 2020;1863(7):194560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qin W, Cho KF, Cavanagh PE, Ting AY. Deciphering molecular interactions by proximity labeling. Nat. Meth. 2021;18(2):133–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seath CP, Trowbridge AD, Muir TW, MacMillan DWC. Reactive intermediates for interactome mapping. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021;50(5):2911–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ummethum H, Hamperl S. Proximity Labeling Techniques to Study Chromatin. Front. Genet. 2020;11(450). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roux KJ, Kim DI, Raida M, Burke B. A promiscuous biotin ligase fusion protein identifies proximal and interacting proteins in mammalian cells. J. Cell. Biol. 2012;196(6):801–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sears RM, May DG, Roux KJ. BioID as a Tool for Protein-Proximity Labeling in Living Cells. Meth. Mol. Biol. 2019;2012:299–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Branon TC, Bosch JA, Sanchez AD, Udeshi ND, Svinkina T, Carr SA, et al. Efficient proximity labeling in living cells and organisms with TurboID. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018;36(9):880–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cho KF, Branon TC, Rajeev S, Svinkina T, Udeshi ND, Thoudam T, et al. Split-TurboID enables contact-dependent proximity labeling in cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117(22):12143–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schopp IM, Amaya Ramirez CC, Debeljak J, Kreibich E, Skribbe M, Wild K, et al. Split-BioID a conditional proteomics approach to monitor the composition of spatiotemporally defined protein complexes. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:15690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.May DG, Scott KL, Campos AR, Roux KJ. Comparative Application of BioID and TurboID for Protein-Proximity Biotinylation. Cells. 2020;9(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zasadzińska E, Huang J, Bailey AO, Guo LY, Lee NS, Srivastava S, et al. Inheritance of CENP-A Nucleosomes during DNA Replication Requires HJURP. Dev. Cell. 2018;47(3):348–62.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hung V, Udeshi ND, Lam SS, Loh KH, Cox KJ, Pedram K, et al. Spatially resolved proteomic mapping in living cells with the engineered peroxidase APEX2. Nat. Protoc. 2016;11(3):456–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee S-Y, Kang M-G, Park J-S, Lee G, Ting Alice Y, Rhee H-W. APEX Fingerprinting Reveals the Subcellular Localization of Proteins of Interest. Cell Rep. 2016;15(8):1837–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van Ingen H, van Schaik FM, Wienk H, Ballering J, Rehmann H, Dechesne AC, et al. Structural insight into the recognition of the H3K4me3 mark by the TFIID subunit TAF3. Structure. 2008;16(8):1245–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Villasenor R, Pfaendler R, Ambrosi C, Butz S, Giuliani S, Bryan E, et al. ChromID identifies the protein interactome at chromatin marks. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020;38(6):728–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Albanese KI, Krone MW, Petell CJ, Parker MM, Strahl BD, Brustad EM, et al. Engineered Reader Proteins for Enhanced Detection of Methylated Lysine on Histones. ACS Chem. Biol. 2020;15(1):103–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Santos-Barriopedro I, van Mierlo G, Vermeulen M. Off-the-shelf proximity biotinylation for interaction proteomics. Nat. Commun. 2021;12(1):5015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Geri JB, Oakley JV, Reyes-Robles T, Wang T, McCarver SJ, White CH, et al. Microenvironment mapping via Dexter energy transfer on immune cells. Science. 2020;367(6482):1091–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Trowbridge AD, Seath CP, Rodriguez-Rivera FP, Li BX, Dul BE, Schwaid AG, et al. Small molecule photocatalysis enables drug target identification via energy transfer. Biorxiv. 10.1101/2021.08.02.454797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Seath CP, Burton AJ, MacMillan DWC, Muir TW. Tracking chromatin state changes using μMap photo-proximity labeling. Biorxiv. 10.1101/2021.09.28.462236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vermeulen M, Eberl HC, Matarese F, Marks H, Denissov S, Butter F, et al. Quantitative interaction proteomics and genome-wide profiling of epigenetic histone marks and their readers. Cell. 2010;142(6):967–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vermeulen M, Mulder KW, Denissov S, Pijnappel WW, van Schaik FM, Varier RA, et al. Selective anchoring of TFIID to nucleosomes by trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 4. Cell. 2007;131(1):58–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Poepsel S, Kasinath V, Nogales E. Cryo-EM structures of PRC2 simultaneously engaged with two functionally distinct nucleosomes. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2018;25(2):154–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Machida S, Takizawa Y, Ishimaru M, Sugita Y, Sekine S, Nakayama JI, et al. Structural Basis of Heterochromatin Formation by Human HP1. Mol. Cell. 2018;69(3):385–97 e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bartke T, Vermeulen M, Xhemalce B, Robson SC, Mann M, Kouzarides T. Nucleosome-interacting proteins regulated by DNA and histone methylation. Cell. 2010;143(3):470–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thompson RE, Muir TW. Chemoenzymatic Semisynthesis of Proteins. Chem. Rev. 2020;120(6):3051–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bagert JD, Muir TW. Molecular Epigenetics: Chemical Biology Tools Come of Age. Ann. Rev. Biochem. 2021;90:287–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nikolov M, Stutzer A, Mosch K, Krasauskas A, Soeroes S, Stark H, et al. Chromatin affinity purification and quantitative mass spectrometry defining the interactome of histone modification patterns. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2011;10(11):M110 005371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Local A, Huang H, Albuquerque CP, Singh N, Lee AY, Wang W, et al. Identification of H3K4me1-associated proteins at mammalian enhancers. Nat. Genet. 2018;50(1):73–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Smith RA, Knowles JR. Letter: Aryldiazirines. Potential reagents for photolabeling of biological receptor sites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1973;95(15):5072–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lin J, Bao X, Li XD. A tri-functional amino acid enables mapping of binding sites for posttranslational-modification-mediated protein-protein interactions. Mol. Cell. 2021;81(12):2669–81 e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li X, Foley EA, Molloy KR, Li Y, Chait BT, Kapoor TM. Quantitative chemical proteomics approach to identify post-translational modification-mediated protein-protein interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134(4):1982–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Burton AJ, Haugbro M, Gates LA, Bagert JD, Allis CD, Muir TW. In situ chromatin interactomics using a chemical bait and trap approach. Nat. Chem. 2020;12(6):520–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Burton AJ, Haugbro M, Parisi E, Muir TW. Live-cell protein engineering with an ultra-short split intein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117(22):12041–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.David Y, Vila-Perello M, Verma S, Muir TW. Chemical tagging and customizing of cellular chromatin states using ultrafast trans-splicing inteins. Nat. Chem. 2015;7(5):394–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Aparicio Pelaz D, Yerkesh Z, Kirchgassner S, Mahler H, Kharchenko V, Azhibek D, et al. Examining histone modification crosstalk using immobilized libraries established from ligation-ready nucleosomes. Chem. Sci. 2020;11(34):9218–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.de la Torre D, Chin JW. Reprogramming the genetic code. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2021;22(3):169–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bao X, Wang Y, Li X, Li X-M, Liu Z, Yang T, et al. Identification of ‘erasers’ for lysine crotonylated histone marks using a chemical proteomics approach. eLife. 2014;3:e02999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kleiner RE, Hang LE, Molloy KR, Chait BT, Kapoor TM. A Chemical Proteomics Approach to Reveal Direct Protein-Protein Interactions in Living Cells. Cell Chem. Biol. 2018;25(1):110–20 e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Xie X, Li XM, Qin F, Lin J, Zhang G, Zhao J, et al. Genetically Encoded Photoaffinity Histone Marks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139(19):6522–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zheng Y, Gilgenast MJ, Hauc S, Chatterjee A. Capturing Post-Translational Modification-Triggered Protein-Protein Interactions Using Dual Noncanonical Amino Acid Mutagenesis. ACS Chem. Biol. 2018;13(5):1137–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wright TH, Bower BJ, Chalker JM, Bernardes GJ, Wiewiora R, Ng WL, et al. Posttranslational mutagenesis: A chemical strategy for exploring protein side-chain diversity. Science. 2016;354(6312). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yang A, Ha S, Ahn J, Kim R, Kim S, Lee Y, et al. A chemical biology route to site-specific authentic protein modifications. Science. 2016;354(6312):623–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fottner M, Brunner AD, Bittl V, Horn-Ghetko D, Jussupow A, Kaila VRI, et al. Site-specific ubiquitylation and SUMOylation using genetic-code expansion and sortase. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2019;15(3):276–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sudhamalla B, Dey D, Breski M, Nguyen T, Islam K. Site-specific azide-acetyllysine photochemistry on epigenetic readers for interactome profiling. Chem. Sci. 2017;8(6):4250–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Arora S, Sappa S, Hinkelman K, Islam K. Engineering a methyllysine reader with photoactive amino acid in mammalian cells. Chem. Commun. 2020;56(81):12210–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dunkelmann DL, Willis JCW, Beattie AT, Chin JW. Engineered triply orthogonal pyrrolysyl-tRNA synthetase/tRNA pairs enable the genetic encoding of three distinct non-canonical amino acids. Nat. Chem. 2020;12(6):535–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Robertson WE, Funke LFH, de la Torre D, Fredens J, Elliott TS, Spinck M, et al. Sense codon reassignment enables viral resistance and encoded polymer synthesis. Science. 2021;372(6546):1057–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Liu X, Chen Y, Zhang Y, Liu Y, Liu N, Botten GA, et al. Multiplexed capture of spatial configuration and temporal dynamics of locus-specific 3D chromatin by biotinylated dCas9. Genome Biol. 2020;21(1):59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Liu X, Zhang Y, Chen Y, Li M, Zhou F, Li K, et al. In Situ Capture of Chromatin Interactions by Biotinylated dCas9. Cell. 2017;170(5):1028–43.e19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Myers SA, Wright J, Peckner R, Kalish BT, Zhang F, Carr SA. Discovery of proteins associated with a predefined genomic locus via dCas9–APEX-mediated proximity labeling. Nat. Meth. 2018;15(6):437–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Qiu W, Xu Z, Zhang M, Zhang D, Fan H, Li T, et al. Determination of local chromatin interactions using a combined CRISPR and peroxidase APEX2 system. Nuc. Acids Res. 2019;47(9):e52–e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Messner CB, Demichev V, Bloomfield N, Yu JSL, White M, Kreidl M, et al. Ultra-fast proteomics with Scanning SWATH. Nat. Biotechnol. 2021;39(7):846–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Xu WS, Parmigiani RB, Marks PA. Histone deacetylase inhibitors: molecular mechanisms of action. Oncogene. 2007;26(37):5541–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Shorstova T, Foulkes WD, Witcher M. Achieving clinical success with BET inhibitors as anti-cancer agents. Br. J. Cancer. 2021;124(9):1478–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wu D, Qiu Y, Jiao Y, Qiu Z, Liu D. Small Molecules Targeting HATs, HDACs, and BRDs in Cancer Therapy. Front. Oncol. 2020;10:560487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bantscheff M, Hopf C, Savitski MM, Dittmann A, Grandi P, Michon AM, et al. Chemoproteomics profiling of HDAC inhibitors reveals selective targeting of HDAC complexes. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29(3):255–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Li X, Wu Y, Tian G, Jiang Y, Liu Z, Meng X, et al. Chemical Proteomic Profiling of Bromodomains Enables the Wide-Spectrum Evaluation of Bromodomain Inhibitors in Living Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141(29):11497–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Jumper J, Evans R, Pritzel A, Green T, Figurnov M, Ronneberger O, et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature. 2021;596(7873):583–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]