Abstract

Thioredoxin is a ubiquitous redox control and cell stress protein. Unexpectedly, in recent years, thioredoxins have been found to exhibit both cytokine and chemokine activities, and there is increasing evidence that this class of protein plays a role in the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases. In spite of this evidence, it has been reported that the oral bacterium and periodontopathogen Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans secretes an immunosuppressive factor (termed suppressive factor 1 [SF1] [T. Kurita-Ochiai and K. Ochiai, Infect. Immun. 64:50–54, 1996]) whose N-terminal sequence, we have determined, identifies it as thioredoxin. We have cloned and expressed the gene encoding the thioredoxin of A. actinomycetemcomitans and have purified the protein to homogeneity. The A. actinomycetemcomitans trx gene has 52 and 76% identities, respectively, to the trx genes of Escherichia coli and Haemophilus influenzae. Enzymatic analysis revealed that the recombinant protein had the expected redox activity. When the recombinant thioredoxin was tested for its capacity to inhibit the production of cytokines by human peripheral blood mononuclear cells, it showed no significant inhibitory capacity. We therefore conclude that the thioredoxin of A. actinomycetemcomitans does not act as an immunosuppressive factor, at least with human leukocytes in cultures, and that the identity of SF1 remains to be elucidated.

The inflammation induced by bacterial infection is caused by the release of factors that can stimulate the production of proinflammatory cytokines (3, 5). We have argued that bacteria (particularly commensal organisms) must also have the capacity to encode and secrete proteins able to inhibit the synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines (2, 4, 18); we have been searching for such proteins for the past few years using oral bacteria, such as Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, that are implicated in the pathology of periodontal diseases (4). We have identified for A. actinomycetemcomitans a 2-kDa peptide with the unusual property of being able to directly induce interleukin-6 (IL-6) synthesis without also inducing the production of the proinflammatory cytokines IL-1 and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) (12). We have also discovered a cell cycle-inhibiting peptide, which we have termed gapstatin. This protein has the capacity to inhibit cell cycle progression in G2 (16, 17). However, as yet, we have not isolated any cytokine-inhibiting proteins from this bacterium.

It has been reported that A. actinomycetemcomitans secretes an immunosuppressive factor (suppressive factor 1 [SF1]) that is able to inhibit (i) the proliferation of lymphocytes, (ii) the production of immunoglobulins, and (iii) the synthesis of the cytokines IL-2 and IL-6 (8, 9, 11). This molecule was purified and sequenced, and the conclusion drawn was that the active protein, which was able to block the synthesis of IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, and gamma interferon (IFN-δ), had no homology with known bacterial or host proteins (9). It was also suggested that the antiproliferative protein gapstatin, identified by our group, might be a breakdown product of SF1 (9).

We recently compared the published N-terminal amino acid sequence of SF1 with sequences in the GenBank and SwissProt databases and found SF1 to have homology to thioredoxin (TRX). Furthermore, we identified the full-length open reading frame of SF1 using data from the A. actinomycetemcomitans genome (University of Oklahoma Actinobacillus Genome Sequencing Project). Comparison of this open reading frame with sequences in the databases confirmed that SF1 was in fact TRX. We have cloned the trx gene of A. actinomycetemcomitans, expressed and purified recombinant TRX, and tested this protein for immunosuppressive activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

A. actinomycetemcomitans NCTC 9710 was grown in a CO2-enriched environment on brain heart infusion agar (Oxoid, Hampshire, United Kingdom) supplemented with 5% (vol/vol) horse blood. Bacteria were grown for 48 h, harvested from the plates with sterile saline, and centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 20 min. Escherichia coli stains TOP10 (Invitrogen) and M15(pREP4) (Qiagen) were used in this study. E. coli was routinely grown in nutrient broth 2 (Oxoid). The medium was supplemented with 25 μg of kanamycin per ml for selection of pCR4 (Invitrogen) in TOP10 and for maintenance of M15(pREP4) and additionally with 100 μg of ampicillin per ml for selection of pQE60 (C-terminal six-histidine tag expression vector) in M15(pREP4).

Cloning of the A. actinomycetemcomitans trx gene.

Chromosomal DNA was extracted from bacteria using a QIAamp blood kit (Qiagen) for DNA purification according to the manufacturer's instructions. This procedure isolated genomic DNA with an average mass of 30 kb. The A. actinomycetemcomitans trx gene, whose sequence was derived from the A. actinomycetemcomitans genome, was amplified by PCR using a forward primer incorporating a BsmFI site (underlined) (5′-GGGACAAAGGAAAAAACATGAGCGAAGTATTAC-3′) and a reverse primer incorporating a BglII restriction site (5′-AGATCTGATATTTTGGTTGATAAATGCGGCC-3′). The resulting amplified fragment was inserted into the vector, pCR4, using a TOPO TA cloning kit (Invitrogen). The sequence of the trx gene was confirmed by cycle sequencing using T3 and T7 primers. The trx gene was excised from pCR4 by digestion with BsmFI and BglII before ligation (using T4 DNA ligase) to similarly digested vector pQE60. The ligation mixture was incubated at 16°C overnight and then transformed into E. coli M15(pREP4).

Expression of trx and purification of recombinant histidine-tagged TRX.

M15(pREP4) cells containing the trx gene were grown in 100 ml of Luria-Bertani medium (containing 100 μg of ampicillin and 25 μg of kanamycin per ml) to an optical density at 600 nm of 1 and then were induced for 4 h at 30°C by the addition of 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG; Sigma). Cells were collected by centrifugation and lysed with a proprietary bacterial lysis medium (B-PER; Pierce). Recombinant histidine-tagged TRX was purified using 1-ml aliquots of nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid–agarose (Qiagen) essentially as described by the manufacturer except that an additional wash step, consisting of 8 ml of a 2-mg/ml solution of polymyxin B in wash buffer, was introduced to remove contaminating lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Recombinant TRX was further purified by gel filtration chromatography using a Superdex 75 column preequilibrated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and attached to a Pharmacia SMART system (Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech, Amersham, United Kingdom).

Enzymatic assay of TRX.

The enzymatic assay of TRX was done as described previously (7). Briefly, the assay relies on TRX being reduced by NADPH and TRX reductase. The reduced TRX then acts to reduce 5′,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB), which is measured spectrophotometrically at 412 nm. For comparative purposes, commercially available preparations of TRX, isolated from the alga Spirulina or from E. coli, were purchased from Sigma.

Culturing of human PBMC.

Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were prepared from buffy coat blood by density gradient centrifugation as described elsewhere (12, 13) and then suspended in RPMI medium supplemented with l-glutamine, 2% fetal calf serum, penicillin, and streptomycin. The cells were transferred into 24-well plates at a density of 2 × 106 cells/ml, and the monocytes were isolated by differential adherence by allowing cells to adhere for 2 h at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2–air. Nonadherent cells were removed and, in some experiments, were exposed separately to TRX. The adherent cells were washed twice with PBS before replacement with the same medium. Cells were stimulated by the addition of various concentrations of concanavalin A (ConA), either alone or in combination with TRX used at between 0.01 and 2 μg/ml (0.8 to 166 nM). To maintain TRX in the reduced state, in some experiments, the protein was treated by incubation with β-mercaptoethanol (50 μM) before being added to cells. In some experiments, cells were stimulated with E. coli LPS (Difco) at a concentration of 10 ng/ml.

Cytokine assays.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) coating and detection antibodies for IL-10, IFN-γ, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) were from Pharmingen (Oxford, United Kingdom), and those for IL-12 were from BioSource (Watford, United Kingdom). Assay kits for IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α and all cytokine standards were from the National Institute for Biological Standards and Control (NIBSC). The concentrations of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α in the media were measured by two-site ELISAs as described previously (13). IL-8 was measured by a two-site ELISA using a protocol similar to that used for the assay of IL-6 (13). Briefly, Maxisorp II 96-well ELISA plates (Gibco, Paisley, United Kingdom) were coated overnight at 4°C with affinity-purified sheep anti-human IL-8 polyclonal antibodies (NIBSC) at 2 μg/ml in PBS. After the plates were washed with PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 (PBS/T), samples were diluted 1/100 in the same buffer as that used for recombinant human IL-8 standards at 20 to 10,000 pg/ml. Samples and standards were applied to the plates and incubated at 37°C for 2 h. After the plates were washed, biotinylated sheep anti-human IL-8 polyclonal antibodies (NIBSC) were added to the plates and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. After the plates were washed, horseradish peroxidase-conjugated avidin (Dako, Cambridge, United Kingdom) diluted 1/4,000 in PBS/T was added, and the plates were incubated at room temperature for 15 min. Concentrations of IL-8 were then determined using O-phenylenediamine (Sigma) as described previously (13). Assays of GM-CSF, IFN-γ, IL-10, and IL-12 were performed according to the assay kit manufacturer's instructions.

RESULTS

Cloning of A. actinomycetemcomitans trx.

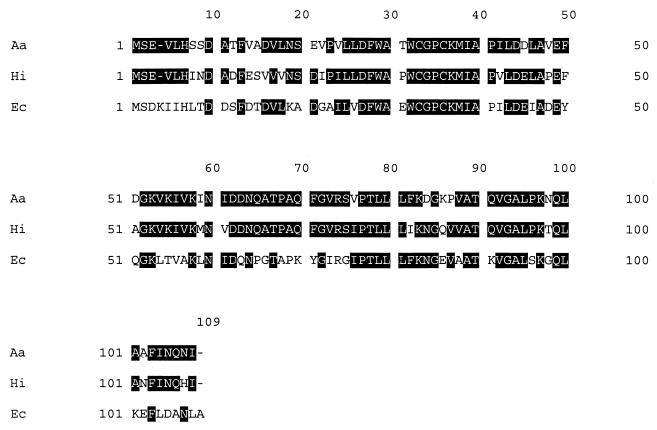

Comparison of the reported N-terminal amino acid sequence (SEVLHSSDATFVADVLNSEVPV) of SF1 from A. actinomycetemcomitans with sequences in the GenBank database revealed that this sequence shared homology with a number of TRXs, the greatest being with that from Haemophilus influenzae (55%). Using the N-terminal amino acid sequence data, we were able to identify the full-length open reading frame (324 bp) of the gene for this protein on one of the contiguous maps produced by the University of Oklahoma Actinobacillus Genome Sequencing Project. We used the sequence data obtained from this map to design primers to enable us to clone by PCR the gene from strain NCTC 9710. DNA sequence analysis of the trx gene cloned from strain NCTC 9710 demonstrated that it was identical to the sequence that we identified in the A. actinomycetemcomitans (strain HK1651) genome database and showed 52% identity and 76% identity, respectively, to the trx genes of E. coli and H. influenzae (Fig. 1). The A. actinomycetemcomitans trx gene codes for a protein of 107 amino acids and with a calculated molecular mass of 11,595 Da.

FIG. 1.

Comparison of the nucleotide sequences of the trx genes of A. actinomycetemcomitans (Aa), H. influenza (Hi), and E. coli (Ec).

Purification and assay of TRX.

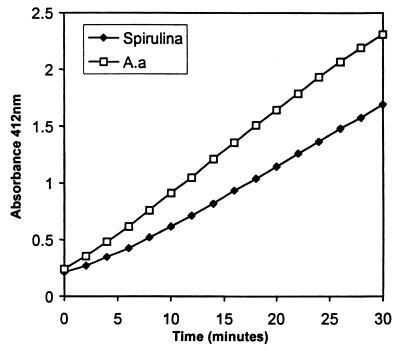

Purified recombinant A. actinomycetemcomitans TRX migrated with an apparent molecular mass of 12 kDa in sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and gel filtration chromatography also revealed that recombinant TRX was a monomer of 12 kDa (results not shown). The recombinant protein was able to reduce DNTB in a manner similar to that of a commercially available preparation of TRX from the alga Spirulina (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Comparison of the enzymatic activities of A. actinomycetemcomitans (A.a) TRX and Spirulina TRX. The graph shows the time course for 10 μM enzyme measured as the absorption at 412 nm of reduced DTNB over 30 min. Results are the means of three replicate assays.

Modulation of cytokine synthesis.

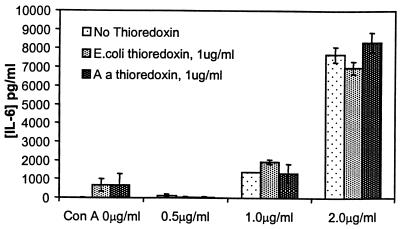

TRX by itself did not stimulate the synthesis of cytokines by human PBMC. Both TRX from A. actinomycetemcomitans and TRX from E. coli were compared for their capacities to inhibit ConA-induced synthesis of IL-6 by adherent human PBMC over the concentration range of 0.01 to 2 μg/ml. No inhibition was seen at any concentration, and the results in Fig. 3 show the comparison of both TRXs at 1 μg/ml. Similar results were found when cells were stimulated with LPS (results not shown).

FIG. 3.

Effect of the addition of 1 μg of A. actinomycetemcomitans (Aa) TRX or E. coli TRX per ml to human PBMC on IL-6 synthesis stimulated by various concentrations of ConA. Results are expressed as the mean and standard deviation (n = 3).

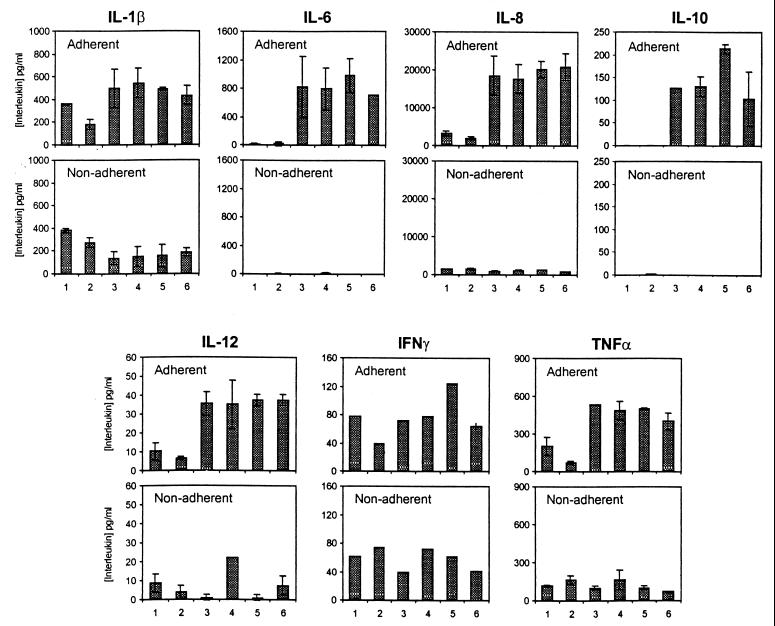

It is possible that A. actinomycetemcomitans TRX is able to inhibit the synthesis of only certain cytokines. Assays of six additional cytokines routinely measured in our laboratory were performed with samples of media from adherent and nonadherent human peripheral blood leukocytes activated separately by ConA in the presence of A. actinomycetemcomitans TRX. Again, over the concentration range of 0.01 to 2 μg/ml, TRX failed to inhibit cytokine synthesis by either cell fraction. The effect of exposing cells to 1 μg of A. actinomycetemcomitans TRX per ml is shown in Fig. 4.

FIG. 4.

Synthesis of a range of cytokines by adherent and nonadherent human PBMC stimulated with various concentrations of ConA in the presence or absence of 1 μg of TRX per ml. Results are expressed as the mean and standard deviation (n = 3, except for IFN-γ, where n = 2). Bars: 1, no additions; 2, TRX at 2 μg/ml; 3, ConA at 1 μg/ml; 4, ConA at 1 μg/ml plus TRX at 0.5 μg/ml; 5, ConA at 1 μg/ml plus TRX at 2 μg/ml; 6, ConA at 1 μg/ml plus TRX at 2 μg/ml and 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol.

DISCUSSION

TRXs, characterized by the CXXC motif and the so-called TRX fold (10), are intracellular proteins catalyzing dithiol-disulfide oxidoreductions. TRX was initially shown to be a hydrogen donor for the enzyme ribonucleotide reductase, which is vital for DNA synthesis (6). In the mid-1980s, the cytokine adult human T-cell leukemia-derived factor was first described as a protein produced by adult human leukemic T cells able to upregulate the expression of the IL-2 receptor α chain (14). This protein was subsequently shown to be TRX (15). More recently, TRX has been proposed to play a role in the prototypic chronic inflammatory disease rheumatoid arthritis by acting as a synergistic factor for TNF-α-induced IL-6 and IL-8 syntheses (19). TRX has also been reported to have potent chemotactic activity for monocytes, neutrophils, and T cells with a unique mode of action (1). In these reports, the TRX proteins used exhibited maximal activity at concentrations of between 1 and 10 nM.

These findings suggested that TRX is “a protein for all seasons,” with a wide range of activities in many biological systems. Kurita-Ochiai and Ochiai (9) reported that a 14-kDa protein (termed SF1) isolated from A. actinomycetemcomitans exhibited immunosuppressive activity over the concentration range of 0.1 to 1 μg/ml. SF1 was able to block the synthesis of a variety of cytokines. Kurita-Ochiai and Ochiai (9) failed to find a match for their N-terminal sequence of SF1 in the then-current databases. We have also searched the sequence databases with the SF1 sequence and, in contrast to Kurita-Ochiai and Ochiai (9), we found that the N-terminal sequence of SF1 identified it as TRX. In light of the various biological activities ascribed to TRX, this finding was surprising but was not impossible (9). The possibility exists that A. actinomycetemcomitans TRX is sufficiently different, in sequence or structure, from E. coli TRX to allow this protein to have a different mode of action. We have cloned the trx gene and expressed and purified the recombinant protein. The trx gene of A. actinomycetemcomitans demonstrates 52% identity and 76% identity, respectively, with the trx genes of E. coli and H. influenzae. The recombinant protein demonstrated enzymatic activity in the standard assay of this protein.

Recombinant A. actinomycetemcomitans TRX was tested for its capacity to inhibit human monocyte cytokine synthesis by ConA- or LPS-stimulated human PBMC. In initial experiments, the inhibitory effects of TRX from A. actinomycetemcomitans and TRX from E. coli were compared. Neither TRX showed any inhibitory activity over the concentration range of 10 ng/ml to 2 μg/ml (0.8 to 166 nM). In a number of additional experiments, adherent and nonadherent human leukocytes were exposed to a range of ConA concentrations in the presence of TRX at 1 μg/ml (83 nM). These concentrations were approximately 10- to 100-fold higher than those used in other studies, which showed that TRX has or acts in synergy with cytokine activity (1, 19). The production of a range of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines was assayed. In none of these experiments was there any evidence of inhibition of cytokine synthesis by TRX.

We therefore conclude that recombinant TRX from A. actinomycetemcomitans is not an immunosuppressive factor able to inhibit cytokine synthesis and that the sequence derived in the earlier work of Kurita-Ochiai and Ochiai (9) may have been the result of contamination of SF1 with the similarity sized TRX, which is present in high concentrations in the bacterial cytoplasm. The identity of SF1 therefore remains to be elucidated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge financial support for P.T. from the Arthritis Research Campaign.

We thank the Actinobacillus Genome Sequencing Project and B. A. Roe, F. Z. Najar, S. Clifton, T. Ducey, L. Lewis, and D. W. Dyer, who are supported by a USPHS/NIH grant from the National Institute of Dental Research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bertini R, Zack Howard O M, Dong H-F, Oppenheim J J, Bizzarri C, Sergi R, Caselli G, Pagliei S, Romines B, Wilshire J A, Mengozzi M, Nakamura H, Yodoi J, Pekkari K, Gurunath R, Holmgren A, Herzenberg L A, Ghezzi P. Thioredoxin, a redox enzyme released in infection and inflammation, is a unique chemoattractant for neutrophils, monocytes, and T cells. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1783–1789. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.11.1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henderson B, Poole S, Wilson M. Bacteria/host interactions in health and disease: who controls the cytokine network. Immunopharmacology. 1996;35:1–21. doi: 10.1016/0162-3109(96)00144-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henderson B, Poole S, Wilson M. Bacterial modulins: a novel class of virulence factor which causes host tissue pathology by inducing cytokine synthesis. Microbiol Rev. 1996;60:316–341. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.2.316-341.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henderson B, Wilson M. Commensal communism in the mouth. J Dent Res. 1998;77:1674–1683. doi: 10.1177/00220345980770090301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henderson B, Poole S, Wilson M. Bacteria/cytokine interactions in health and disease. London, United Kingdom: Portland Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holmgren A. Thioredoxin. Annu Rev Biochem. 1985;54:237–271. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.54.070185.001321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holmgren A, Bjornstedt M. Thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase. Methods Enzymol. 1995;252:199–208. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)52023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kurita-Ochiai T, Ochiai K, Ikeda T. Immunosuppressive effect induced by Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans: effect on immunoglobulin production and lymphokine synthesis. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1992;7:338–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1992.tb00633.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kurita-Ochiai T, Ochiai K. Immunosuppressive factor from Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans down regulates cytokine production. Infect Immun. 1996;64:50–54. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.1.50-54.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin J L. Thioredoxin—a fold for all reasons. Curr Biol. 1995;3:245–250. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00154-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ochiai K, Kurita T, Nishihara K, Ikeda T. Immunoadjuvant effects of periodontitis-associated bacteria. J Periodontal Res. 1989;24:322–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1989.tb00877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reddi K, Nair S P, White P A, Hodges S, Tabona P, Meghji S, Poole S, Wilson M, Henderson B. Surface-associated material from the bacterium Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans contains a peptide which, in contrast to lipopolysaccharide, stimulates fibroblast interleukin-6 gene transcription. Eur J Biochem. 1996;236:871–876. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.00871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tabona P, Reddi K, Khan S, Nair S P, Crean S J, Meghji S, Wilson M, Preuss M, Miller A D, Poole S, Carne S, Henderson B. Homogeneous Escherichia coli chaperonin 60 induces IL-1β and IL-6 gene expression in human monocytes by a mechanism independent of protein conformation. J Immunol. 1998;161:1414–1421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tagaya Y, Okada M, Sugie K, Kasahara T, Kondo N, Hamuro J, Matsushima K, Dinarello C A, Yodoi J. IL-2 receptor (p55) Tac-inducing factor: purification and characterisation of adult T cell leukemia-derived factor. J Immunol. 1988;140:2614–2620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tagaya Y, Maeda Y, Mitsui A, Kondo N, Matsui H, Hamuro J, Brown N, Arai K I, Yokota T, Wakasugi H, Yodoi J. ATL-drived factor (ADF), an IL-2 receptor/Tac inducer homologous to thioredoxin: possible involvement of dithiol-reduction in the IL-2 receptor induction. EMBO J. 1989;8:757–764. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03436.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.White P A, Wilson M, Nair S P, Kirby A C, Reddi K, Henderson B. Characterization of an antiproliferative surface-associated protein from Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans which can be neutralized by sera from a proportion of patients with localized juvenile periodontitis. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2612–2618. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.7.2612-2618.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.White P A, Wilson M, Patel M, Nair S P, Henderson B, Olsen I. Gapstatin: a bacterial protein with a novel mechanism of cell cycle inhibition. Eur J Cell Biol. 1998;77:228–238. doi: 10.1016/S0171-9335(98)80111-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson M, Seymour R, Henderson B. Bacterial perturbation of cytokine networks. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2401–2409. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.2401-2409.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoshida S, Katoh T, Toshifumi T, Uno K, Matsui N, Okamoto T. Involvement of thioredoxin in rheumatoid arthritis: its costimulatory roles in the TNF-α-induced production of IL-6 and IL-8 from cultured synovial fibroblasts. J Immunol. 1999;163:351–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]