Abstract

Studying individuals who recently experienced a romantic reltionship breakup allows us to investigate mood disturbances in otherwise healthy individuals. In our study, we aimed to identify distinct depressive symptom trajectories following breakup and investigate whether these trajectories relate to personality traits and cognitive control. Subjects (n = 87) filled out questionnaires (RRS‐NL‐EXT trait rumination and NEO‐FFI neuroticism) and performed cognitive tasks (trail making test, Stroop task) during a period of 30 weeks. To identify distinct depressive symptom trajectories (‘trajectory groups’), we performed K‐means clustering on the consecutive (assessed every 2 weeks) Major Depression Inventory scores. This resulted in four trajectory groups; ‘resilience’, ‘fast recovery’, ‘slow recovery’ and ‘chronic distress’. The ‘slow recovery group’ and the ‘chronic distress group’ were found to have higher neuroticism and trait rumination levels compared to the ‘resilience group’, and the ‘chronic distress group’ also had higher neuroticism levels than the ‘fast recovery group’. Moreover, the ‘chronic distress group’ showed worse overall trail making test performance than the ‘resilience group’. Taken together, our findings show that distinct patterns of depressive symptom severity can be observed following breakup and that personality traits and cognitive flexibility seem to play a role in these depressive symptom patterns.

Keywords: cognitive control, depression, depressive symptom trajectory, neuroticism, relationship breakup, rumination

1. INTRODUCTION

It is known that stressful events are risk factors for the development of depressive symptoms and developing an episode of clinical depression (Kendler et al., 1999). In our laboratory, we aim to understand why some individuals are more vulnerable to develop symptoms of depression whereas others are not. By studying healthy individuals who suffer from a depression‐like state, knowledge can be gained about the transition from healthy behaviour to depressive behaviour and factors that play a role in this transition. One potential stressful event is the breakup of a romantic relationship. Previous cross‐sectional research displayed various symptoms, including symptoms of depression, among people who experienced a relationship breakup (Field et al., 2009; Fisher et al., 2010; Stoessel et al., 2011; Verhallen et al., 2019). Studying individuals who recently experienced a romantic relationship breakup allows us to investigate mood disturbances in otherwise healthy individuals. This way, we can gain new insights into factors that play a role in dealing with stressful events and identify vulnerability factors for developing depressive symptoms during a negative period in life. Potentially, we may translate this knowledge to (prevention of) clinical depression.

Previous research regarding the course of distress after a variety of negative and stressful events has been conducted and display individual differences in the duration, onset and offset and intensity of their symptoms. Nonetheless, individuals usually can be grouped according to typical patterns of distress over time. Generally, four symptom trajectory types can be distinguished across individuals; resilience (low symptoms that stay low over time), recovery (high symptoms decreasing over time), delayed symptoms (symptoms that grow over time) and chronic symptoms (high symptoms that stay high over time) (Bonanno, 2004; Mancini et al., 2015). For instance, studies among people suffering from bereavement, showed that depressive and posttraumatic symptoms can be characterised in distinguishable patterns over time; absence of symptoms, development of symptoms at a later moment in time, recovery and chronic symptoms (Mancini et al., 2015). Also following two disasters, typical trajectories of posttraumatic symptoms (i.e., resilience, recovery and chronic symptoms) were identified (Norris et al., 2009).

Consequently, the first aim of the present study was to explore depressive symptoms over time among people who recently experienced a relationship breakup and describe trajectories of depressive symptom severity. We expected to identify distinct patterns of depressive symptom severity and change. The second aim of this study was to explore the relation between vulnerability factors for depression and the patterns of depressive symptoms identified.

The vulnerability factors investigated here will be introduced below. One vulnerability factor relates to personality trait. Specifically, neuroticism and rumination have been suggested to be involved in mood disorders, including depression (Nolen‐Hoeksema, 2000; Paulus et al., 2016). People who score high on the personality trait neuroticism tend to be less emotionally stable and more emotionally reactive, especially in response to negative events (Costa & McCrae, 1980; Servaas et al., 2013). In addition, being highly neurotic has been associated with biases in information processing and experiencing negative affect and mood problems (Chan et al., 2007). Nolan et al. (1998) measured depressive symptom severity at baseline as well as after a period of eight to 10 weeks in a university sample and found that subjects with high levels of neuroticism at baseline reported higher levels of depressive symptoms at both time points. Furthermore, after marital divorce, people with a resilient trajectory (i.e., absence of symptoms) showed low levels of neuroticism (Knöpfli et al., 2016). Interestingly, Mineka et al. (2020) found that high levels of neuroticism as well as the occurrence of negative events separately increased the risk of developing depression. Rumination implies repetitively paying attention to one's feelings of distress in response to a negative mood (Nolen‐Hoeksema, 1991). A ruminative coping strategy is known to be related to mood disorders. In patients with major depression, rumination was associated with experiencing new episodes of depression (Nolen‐Hoeksema, 2000). A distinction can be made between brooding rumination (i.e., a passive and maladaptive type of rumination) and reflection rumination (i.e., a more adaptive type of rumination) (Treynor et al., 2003). Especially brooding rumination was associated with the occurrence of depressive episodes (Huffziger et al., 2009). Furthermore, during grief, presence of ruminating thoughts about the loss of the loved one was associated with the development of depressive symptoms and maladaptive forms of grief (Eisma et al., 2015). Moreover, following the occurrence of a disturbing life‐event, people with a ruminative response style experienced more severe depressive symptoms after 10 days and seven weeks (Nolen‐Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991). It might be that rumination underlies the considered link between neuroticism and depression, as individuals who score high on neuroticism tend to have a ruminative coping strategy and experience ruminating thoughts following a negative situation (Roelofs et al., 2008).

Rumination has also been linked to cognitive control (i.e., higher‐order cognitive functions that subserve performing goal‐directed behaviour and controlling our behaviour). People with high tendencies to ruminate showed more difficulties with cognitive control, as measured by the capability to switch between memorised words with alternating affective valence (Beckwé et al., 2014). Also, cognitive flexibility (i.e., shifting between different tasks) was reduced in students with a ruminative coping style (Davis & Nolen‐Hoeksema, 2000). Subsequently, an interplay between rumination, cognitive control and depression has been suggested. Possibly, reduced cognitive control makes it more difficult to inhibit ruminating thoughts and switch to more adaptive strategies of dealing with emotionally disturbing situations. Another possibility is that elevated rumination depletes cognitive resources, leading to impaired cognitive control capacity. Possibly, people with impaired cognitive control are more likely to engage in ruminative thinking which consequently results in a depressed mood (Philippot & Agrigoroaei, 2017; Philippot & Brutoux, 2008).

Thus, high levels of neuroticism and rumination as well as cognitive control disturbances seem to be related to (symptoms of) depression in healthy and clinical populations. Possibly, these vulnerability factors also play a role in the affectedness and recovery following romantic relationship breakup. Recapitulating the second aim, we investigated whether neuroticism, rumination and cognitive control functioning are related to the depressive symptom trajectory following breakup. We expected that individuals who are less capable of recovering from the effect of the breakup or display a pattern of persistent symptoms have higher levels of neuroticism and/or rumination and worse cognitive control.

Taken together, in the present study, we aimed to identify distinct depressive symptom trajectories following a potential negative event (i.e., romantic relationship breakup) and investigate whether these trajectories relate to personality traits (rumination, neuroticism) and cognitive control functioning. To this end, women who experienced a romantic relationship breakup within the preceding 2 months were included in our longitudinal study. Given that previous research revealed higher self‐reported depression scores among the females of the breakup group (Verhallen et al., 2019) and clinical depression rates are higher among women in the general population (Kessler et al., 1993), we included only women in the present study.

2. METHODS

2.1. Experimental design

Women (n = 87) who experienced a romantic relationship breakup within the preceding 2 months were included in our longitudinal study between November 2018 and November 2019. Measurements were conducted between November 2018 and June 2020. Subjects visited our laboratory three times during a period of 30 weeks to fill out questionnaires, perform cognitive tasks and undergo fMRI scanning. The first study visit (T1) was scheduled as soon as possible after the subject decided to participate in the study, in order to perform the first measurements as recent as possible after breakup. At T1, subjects filled out a questionnaire battery and performed two cognitive tasks. The second study visit (T9) took place 16 weeks (±1 week) after the first visit. At T9, subjects performed the same two cognitive tasks as at T1. The third study visit (T16) took place 30 weeks (+3 weeks) after T1. T16 contained the same cognitive tasks as T1 and T9 as well as a functional MRI session. Moreover, at T2–T8 and T10–T15, subjects completed an online questionnaire every 14 days (+2 days/−1 day). Results from the fMRI experiment will be presented elsewhere.

For two subjects, their third visit was conducted earlier than the study protocol allows. For five subjects, the second visit was scheduled a few days (range between −4 and +3 days) outside the time window of the study protocol due to various reasons such as no shows and illness. One subject did not perform T9 and T16, other measurements were obtained. Two subjects dropped out during the study period because of personal circumstances.

Due to the COVID‐19 pandemic and measures taken in the Netherlands, 36 subjects could not visit our laboratory for their third visit. Online questionnaires were filled out as planned.

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects during the first visit prior to conductance of any measurements. The study was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee and conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Subjects received a financial compensation of €75 after the last visit. Subjects who decided to withdraw from the study received financial compensation on a pro rata basis. The study was registered in The Netherlands National Trial Register (NTR).

2.2. Recruitment strategy

We recruited subjects by putting up posters and distributing flyers at the University Medical Center Groningen, faculty buildings of the University of Groningen, the University of Applied Sciences and in public places of the city of Groningen such as supermarkets and cafes. In addition, we promoted the study via (social) media. Following the signup of someone willing to participate, a telephone screening was scheduled to assess study eligibility. Study procedures were orally explained by the researcher. Eligible volunteers received an information letter by e‐mail.

2.3. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All subjects had a romantic relationship breakup maximum 2 months ago at the time of written informed consent. Prior to breakup, the relationship duration was at least 6 months. Other inclusion criteria were: 1) age between 18 and 35 years, 2) Caucasian ethnicity, 3) right‐handed, 4) heterosexual, 5) Dutch as a native language (all self‐reported). Subjects had to be Caucasian and right‐handed as the study included an fMRI session and ethnicity as well as handedness are known to influence brain anatomy. Heterosexuality was chosen as an inclusion criterion to be in line with previous studies concerning breakup (Stoessel et al., 2011; Verhallen et al., 2019). Subjects who met any of the following criteria were excluded from participation: 1) diagnosis of a neurological disorder, 2) diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder, 3) vision problems that could not be corrected adequately, 4) not able to undergo 3 T MRI scanning. MRI exclusion criteria include MRI incompatible implants or (metal) objects in the body, (suspected) pregnancy, claustrophobia and the refusal to be informed of brain abnormalities that could be detected serendipitously during the scan.

Three subjects were excluded after their first visit; new information obtained at the first visit revealed study ineligibility (misunderstanding of the relevant screening question during the telephone screening interview).

2.4. Questionnaire battery

We used the RoQua platform to administer questionnaires during the study (https://www.roqua.nl). At the three visits, subjects filled out the questionnaires by logging in to the RoQua application. In between the three visits, subjects received an invitation by e‐mail to fill out the questionnaires.

2.5. Questionnaires filled out during the first visit

We used the Ruminative Response Scale (RSS)‐NL‐EXT to assess trait rumination (Nolen‐Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991). The RRS‐NL‐EXT is the most recent official Dutch language version of the RRS (Schoofs et al., 2010). Items were scored on a 4‐point Likert scale and scores were summed to obtain a total score for each subject. Total scores theoretically range between 22 and 88. Cronbach's alpha was found to be 0.87. In addition, scores for the brooding rumination and reflection rumination subscales were computed (Treynor et al., 2003). To measure the personality trait neuroticism, subjects filled out the neuroticism domain (12 items) of the Dutch NEO Five Factor Inventory (NEO‐FFI) (Costa & McCrae, 1992). The NEO‐FFI was scored on a 5‐point Likert scale. Scores of the 12 questions were summed according to the scoring guideline. Total scores theoretically range between 12 and 60. Cronbach's alpha was found to be 0.81. We revealed self‐reported relationship quality with the Perceived Relationship Quality Components Inventory (PRQC) (Fletcher et al., 2000). We extracted nine items from the original 18‐item version to end up with a version consisting of items that are clearly distinguishable in the Dutch language. The PRQC was scored on a 7‐point Likert scale. Total scores theoretically range between 9 and 63. Cronbach's alpha was found to be 0.87. We administered an in‐house developed questionnaire about the relationship breakup, consequences of the breakup and feelings about the breakup. Questions were scored on a 10‐point Likert scale or categorical. Moreover, we registered background information of the subjects, such as education, occupation and familial predisposition for psychiatric diseases.

2.6. Repeated questionnaires

We administered the Major Depression Inventory (MDI) 16 times during the 30‐week study period. The MDI is a brief (10 items) questionnaire to measure severity of depressive symptoms, based on the DSM‐IV and ICD‐10 diagnostic criteria (Bech et al., 2001). Subjects filled out the MDI every 14 days during the study. Subjects who had their third visit more than 14 days postponed (as our study protocol allows a time window of plus 3 weeks), filled out an additional MDI. Reliability of the MDI was found to be adequate (Cronbach's alpha of 0.89) and MDI scores correlated sufficiently with scores belonging to the Symptom Checklist‐90 in a Dutch study (Cuijpers et al., 2007). Items were scored on a 6‐point Likert scale and scores were summed to end up with a total score representing depressive symptom severity in the past two weeks. Total scores theoretically range between 0 and 50. Total scores between 0 and 20 correspond to absence of depression, total scores between 21 and 25 correspond to mild depression, total scores between 26 and 30 indicate moderate depression and total scores above 31 indicate severe depression (Bech et al., 2015).

2.7. Cognitive tasks

To assess cognitive control functioning, subjects performed the Stroop Color Naming Task (Stroop, 1935) and the trail making test (TMT) (Tombaugh, 2004).

2.8. Stroop task

We used an in‐house developed digital version of the Stroop task to measure inhibitory control capacities. We used OpenSesame version 3.2.5 to build and present the task (Mathôt et al., 2012). Subjects performed the Stroop task three times during the study. The task consisted of two conditions: the black condition and the experimental condition. In the black condition, names of colours (yellow, green, red and blue in Dutch) were presented in black and subjects were instructed to identify the name of the colour. In the experimental condition, names of colours (yellow, green, red and blue in Dutch) were presented in either a congruent colour or an incongruent colour and subjects were instructed to identify the presentation colour instead of the word (e.g., the word blue is presented in red and the correct answer would be red). Subjects could indicate their answer by pressing a corresponding button on a keyboard covered with a colour sticker. Subjects were instructed to keep their fingers on the keys (yellow key left middle finger, red key right index finger, blue key right middle finger) and work as fast and accurate as possible. The task consisted of six separate blocks; one block presenting 40 black condition trials and five blocks presenting experimental condition trials (40 trials per block). In total, 100 congruent trials and 100 incongruent trials were presented across the five experimental blocks. Fixation crosses (500 ms) were presented in between the single trials. Maximum response time was set at 4000 ms. In between the blocks, a screen, indicating the start of a new block, was presented to reduce fatigue. Before the start of each block a fixation cross (2000 ms) was presented. Prior to the start of a certain condition (either black or experimental), subjects received written instructions and could practice the corresponding condition (10 trials). Colours were balanced across the task. We used three different versions of the task (shuffled sequences) in order to avoid potential learning effects. Hit rates and reaction times per trial were derived from the OpenSesame logfiles. We calculated interference scores by computing the difference in mean reaction time between the incongruent trials and congruent trials of the experimental condition.

2.9. Trail making test

We used a paper version of the TMT to measure cognitive flexibility. Subjects performed the TMT three times during the study. The TMT consists of two separate parts. In the first part of the task (TMT‐A) subjects were instructed to connect 25 sequentially numbered circles. In the second part of the task (TMT‐B) subjects were instructed to make 13 sequential combinations of numbered and lettered circles, alternating between numbers and letters (Tombaugh, 2004). TMT‐A can be used to measure attention and motor speed. TMT‐B measures cognitive flexibility (Arbuthnott & Frank, 2000). The outcome for both parts of the task is the time needed to complete the task. Mistakes were corrected by the researcher immediately during the task. This way, a higher number of mistakes results in a longer completion time.

3. DATA ANALYSIS

Data was processed and analysed using SPSS Statistics 25, R version 4.0.2 and R Studio version 1.3.1073 for Windows.

3.1. K‐means clustering depression scores

To group our subjects according to their depressive symptom trajectory in a data‐driven manner, we conducted K‐means clustering for longitudinal data using the KmL package in R (Genolini & Falissard, 2011). To this end, 16 consecutive MDI scores were entered into the analysis for every subject. As time since breakup at the day of the first measurement ranged between 10 and 62 days, data were resampled to a 14‐day interval using the MDI score closest, though preceding in time. Data were completed using Not a Number (NaN) to ensure an equal number of data points per subject (e.g., 14 days since the breakup would be one NaN data point at the start and two at the end). Cluster solutions (using 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 clusters) were explored. The optimal cluster solution for our data was determined by checking default cluster criterions (i.e., Calinski & Harabasz, Ray & Turi, Davies & Bouldin) followed by visual inspection (patterns, cluster sizes).

3.2. Questionnaire data analysis

To investigate whether the personality traits neuroticism and rumination were related to the depressive symptom trajectory following breakup, we tested between‐group differences regarding neuroticism (NEO‐FFI total scores) and rumination (RRS‐NL‐EXT total scores) using a one‐way MANOVA. Differences regarding the RRS‐NL‐EXT brooding rumination and reflection rumination subscales were assessed using one‐way ANOVA tests. Additional to the personality trait variables, we assessed differences between the trajectory groups with regard to breakup and relationship variables using a one‐way MANOVA test. For all analyses, homogeneity of variances was checked and in case of violation, Welch's correction was applied. As a post‐hoc test, pairwise group comparisons were performed. Tukey Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) tests or Games‐Howell tests were applied for homogeneous and non‐homogeneous variances, respectively. Additional to investigating trajectory group differences, we assessed associations between depressive symptom severity at the first visit (MDI T1) and breakup and relationship variables among the total sample to better interpret the starting points of the trajectories, using Spearman rank correlations. Furthermore, we calculated the Spearman rank correlation between the RRS‐NL‐EXT total scores and the NEO‐FFI total scores.

3.3. Cognitive task data analysis

One subject scored extremely low on the Stroop task at the first visit due to misunderstanding of the task, therefore this task data was excluded for further analyses.

To investigate the relation between the depressive symptom trajectory and cognitive control functioning, we tested whether the trajectory groups differed with regard to their (repeated) cognitive task performance. We performed linear mixed effects (LME) analyses using the lme4 package in R (Bates et al., 2015). The measures TMT‐A completion time, TMT‐B completion time and Stroop interference score were entered as response variables into separate models. Group and time were entered as fixed effects into the models. Subject was entered as random intercept. Likelihood ratio tests (maximum likelihood estimation) were performed to compare models with and without the effect of interest (i.e., time, group + time or group × time). Restricted maximum likelihood was used to estimate model parameters for the models of interest. Post‐ hoc Tukey tests were performed to compare separate (group and time) contrasts.

In addition, as personality traits and cognitive control functioning were found to be related in previous studies (Beckwé et al., 2014; Davis & Nolen‐Hoeksema, 2000), we performed separate LME analyses with RRS‐NL‐EXT total scores and NEO‐FFI total scores as fixed effects (instead of group) to assess influences of personality traits on cognitive control functioning among our total study sample.

Results were considered significant at p < 0.05.

4. RESULTS

4.1. Study sample

Our total study sample consisted of 87 women. The ages ranged from 18 to 34 (M = 23.72, SD = 3.93). Additional characteristics of the total sample can be found in Supplementary Table S1.

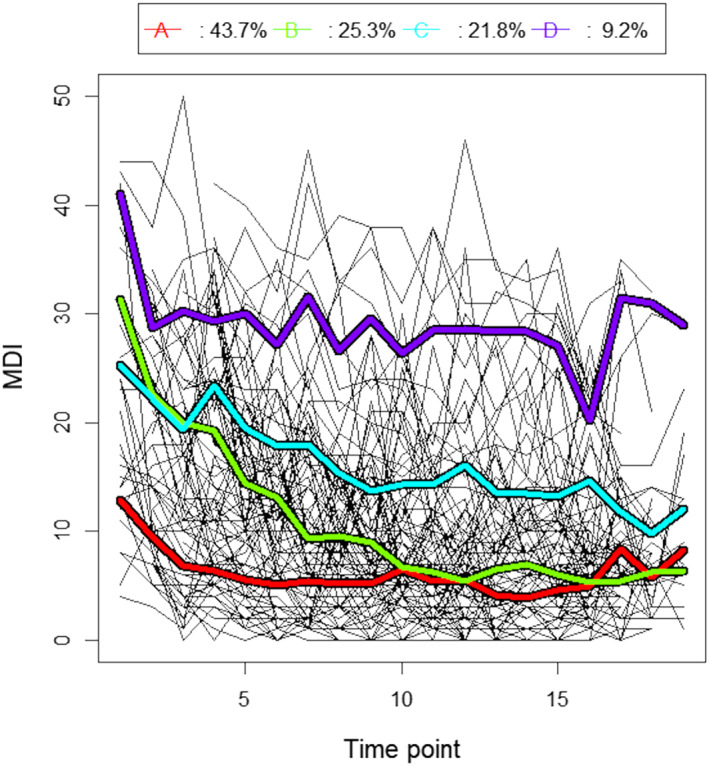

4.2. Identifying depressive symptom trajectory clusters

According to three (Calinski & Harabasz1, Ray & Turi, and Davies & Bouldin) of the KmL cluster criterions (Supplementary Figure S1), the 2‐cluster solution would fit our data most optimally. The two clusters obtained can be dubbed ‘resilience’ and ‘recovery’ (Supplementary Figure S2). The 3‐cluster solution (Supplementary Figure 3) did not score maximally on any of the criterions. Nonetheless, clusters obtained can be characterised as ‘resilience’, ‘recovery’ and ‘almost chronic’. The overlap in classification between the 2‐cluster solution and the 3‐cluster solution can be found in Supplementary Table S2. As for three clusters, the 4‐cluster solution (Figure 1) did not score maximally on any of the criterions; for the Calinski & Harabasz3 criterion the score is similar to that of the 3‐cluster and 5‐cluster solution. In this case, clusters can be described as ‘resilience’, ‘fast recovery’, ‘slow recovery’ and ‘chronic distress’. The overlap in classification between the 3‐cluster solution and the 4‐cluster solution can be found in Supplementary Table S3. The 5‐cluster solution (Supplementary Figure S4) scored maximally on the Calinski & Harabasz3 criterion. It is noteworthy that cluster patterns are similar to the 4‐cluster solution, albeit that the ‘resilience’ cluster got split into two subclusters (see Supplementary Table S4). The 6‐cluster solution (Supplementary Figure S5) scored maximally on the Calinski & Harabasz2 criterion, however resulted in relatively small cluster sizes. In addition, interpretation of the temporal behaviour became less straightforward. For the remaining of this paper, we will focus on the 4‐cluster solution as this provided the clearest interpretation. Alternative cluster solutions are presented in the Supplementary Materials. For a detailed description as to why we chose for the 4‐cluster solution, see the discussion section of this paper.

FIGURE 1.

Four‐cluster solution depressive symptom trajectories, based on consecutive MDI scores. Thin black lines represent individual trajectories. Thick coloured lines represent mean trajectory of the four (red, A ‘resilience’; green, B ‘fast recovery’; blue, C ‘slow recovery’; purple, D ‘chronic distress’) trajectory clusters

4.3. Characteristics trajectory groups

Subsequently, we described characteristics (demographics, background information) of the four clusters (‘trajectory groups’), presented in Table 1. Age did not differ between the groups (F[3, 83] = 0.566, p = 0.639).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics trajectory groups

| Resilience group’ | ‘Fast recovery group’ | ‘Slow recovery group’ | ‘Chronic distress group’ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 38) | (n = 22) | (n = 19) | (n = 8) | |

| Age (years) | 23.13 ± 3.63 | 24.45 ± 4.22 | 23.95 ± 3.82 | 24.00 ± 5.04 |

| Education (%) | ||||

| High school | 36.8 | 45.5 | 36.8 | 25.0 |

| MBO (vocational education) | 5.3 | 13.6 | 0.0 | 25.0 |

| HBO (applied university) | 18.4 | 22.7 | 36.8 | 25.0 |

| University | 39.5 | 18.2 | 26.3 | 25.0 |

| Occupation (%) | ||||

| Student | 71.1 | 59.1 | 42.1 | 62.5 |

| Working | 28.9 | 40.9 | 57.9 | 25.0 |

| None of the above | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 12.5 |

| Previous relationships (%) | ||||

| 0 | 39.5 | 36.4 | 36.8 | 12.5 |

| 1 | 47.4 | 27.3 | 36.8 | 37.5 |

| 2 | 13.2 | 18.2 | 21.1 | 50.0 |

| 3 | 0.0 | 18.2 | 5.3 | 0.0 |

| Previous heartbreak (%) | ||||

| Yes | 60.5 | 72.7 | 73.7 | 100.0 |

| No | 39.5 | 27.3 | 26.3 | 0.0 |

| First‐degree relative psychiatric disease (%) | ||||

| Yes | 10.5 | 9.1 | 21.1 | 25.0 |

| No | 89.5 | 90.9 | 73.7 | 75.0 |

| Unknown | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.3 | 0.0 |

| Second‐degree relative psychiatric disease (%) | ||||

| Yes | 13.2 | 22.7 | 26.3 | 25.0 |

| No | 81.6 | 72.7 | 73.7 | 75.0 |

| Unknown | 5.3 | 4.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

Note: Values are reported as mean ± SD or percentage for the numerical and categorical variables respectively.

4.4. Breakup and relationship parameters trajectory groups

We explored breakup and relationship parameters and group differences herein, using a one‐way MANOVA. See Table 2 for an overview.

TABLE 2.

Breakup and relationship parameters per trajectory group

| ‘Resilience group’ | ‘Fast recovery group’ | ‘Slow recovery group’ | ‘Chronic distress group’ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 38) | (n = 22) | (n = 19) | (n = 8) | |

| Time since breakup (days) | 34.58 ± 14.69 | 41.14 ± 12.79 | 40.53 ± 16.84 | 29.50 ± 13.58 |

| Relationship duration (months) | 41.24 ± 26.45 | 36.32 ± 31.49 | 45.58 ± 26.74 | 39.75 ± 35.57 |

| PRQC | 47.26 ± 9.64 | 51.00 ± 7.19 | 48.74 ± 6.14 | 48.25 ± 12.68 |

| Heartbreak severity* | 4.45 ± 2.13 | 6.36 ± 1.79 | 6.37 ± 2.39 | 7.63 ± 2.33 |

| Interference heartbreak daily activities* | 3.26 ± 1.84 | 5.41 ± 1.99 | 4.58 ± 1.95 | 7.13 ± 2.48 |

| Ruminating thoughts breakup* | 5.26 ± 2.09 | 7.68 ± 2.23 | 7.68 ± 2.16 | 8.38 ± 2.33 |

| Intrusive thoughts ex‐partner* | 4.79 ± 2.51 | 6.82 ± 2.38 | 7.42 ± 2.17 | 8.00 ± 2.62 |

| Unexpectedness breakup* | 4.08 ± 2.58 | 7.00 ± 2.88 | 5.68 ± 2.93 | 6.13 ± 3.60 |

| Who initiated the breakup (%) | ||||

| Subject | 52.6 | 40.9 | 42.1 | 12.5 |

| Ex‐partner | 23.7 | 50.0 | 42.1 | 75.0 |

| Mutual | 23.7 | 9.1 | 15.8 | 12.5 |

| Thinking about ex‐partner (%) | ||||

| Daily | 68.4 | 95.5 | 84.2 | 100.0 |

| Weekly | 31.6 | 4.5 | 15.8 | 0 |

| New romantic partner (%) | ||||

| Yes | 7.9 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| No | 92.1 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Still in touch with ex‐partner (%) | ||||

| Yes | 65.8 | 59.1 | 68.4 | 75.0 |

| No | 34.2 | 40.9 | 31.6 | 25.0 |

| Physical complaints (%) | ||||

| Yes | 18.4 | 59.1 | 36.8 | 75.0 |

| No | 81.6 | 40.9 | 63.2 | 25.0 |

| Increased substance use (%) | ||||

| Yes | 10.5 | 40.9 | 10.5 | 50.0 |

| No | 89.5 | 59.1 | 89.5 | 50.0 |

Note: Values are reported as mean ± SD or percentage for the numerical and categorical variables respectively. Parameters that differed significantly between the groups are indicated with *.

A significant effect of group was found (Wilk's Λ = 0.472, F = 2.724, p < 0.001). Multiple breakup parameters, assessed at the first visit, differed significantly between the groups. Corresponding statistics are reported in Table 3. Post‐hoc Tukey HSD tests revealed that the ‘resilience group’ and the ‘fast recovery group’ differed regarding unexpectedness of the breakup (p = 0.001), heartbreak severity (p = 0.006), interference heartbreak with daily activities (p = 0.001), intrusive thoughts ex‐partner (p = 0.012) and ruminating thoughts breakup (p < 0.001). The ‘resilience group’ and the ‘slow recovery group’ differed regarding heartbreak severity (p = 0.010), intrusive thoughts ex‐partner (p = 0.001) and ruminating thoughts breakup (p = 0.001). The ‘resilience group’ and the ‘chronic distress group’ differed regarding heartbreak severity (p = 0.001), interference heartbreak with daily activities (p < 0.001), intrusive thoughts ex‐partner (p = 0.005) and ruminating thoughts breakup (p = 0.002). The ‘slow recovery group’ and the ‘chronic distress group’ differed regarding interference heartbreak with daily activities (p = 0.015). No breakup‐related differences were found between the ‘fast recovery group’ and the ‘slow recovery group’ and between the ‘fast recovery group’ and the ‘chronic distress group’. Time since breakup and relationship parameters (duration, PRQC) did not differ between the groups.

TABLE 3.

Statistics one‐way MANOVA breakup and relationship parameters

| F(3, 83) | p | |

|---|---|---|

| Time since breakup | 1.995 | 0.121 |

| Relationship duration | 0.361 | 0.782 |

| PRQC | 0.857 | 0.467 |

| Heartbreak severity* | 7.912 | <0.001 |

| Interference heartbreak daily activities* | 11.347 | <0.001 |

| Ruminating thoughts breakup* | 10.015 | <0.001 |

| Intrusive thoughts ex‐partner* | 7.896 | <0.001 |

| Unexpectedness breakup* | 5.328 | 0.002 |

Note: Parameters that differed significantly between the groups are indicated with *.

Associations between depressive symptom severity at the first visit and breakup and relationship parameters among the total sample can be found in Supplementary Table S5.

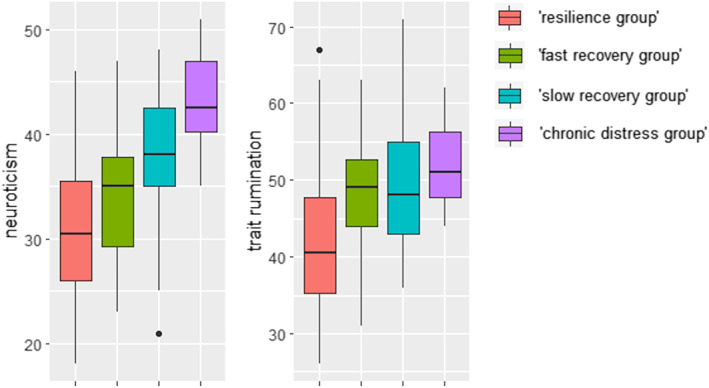

4.5. Trajectory group differences in neuroticism and rumination levels

Among our total sample, neuroticism scores were found to correlate highly with trait rumination scores (r s = 0.509, p < 0.001). To investigate the possible influence of personality traits, we tested, using a one‐way MANOVA, whether the trajectory groups differed regarding neuroticism and trait rumination. Neuroticism and trait rumination levels per trajectory group are shown in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Neuroticism and trait rumination levels among the four (‘resilience’ n = 38, ‘fast recovery’ n = 22, ‘slow recovery’ n = 19, ‘chronic distress’ n = 8) trajectory groups

A significant effect of group was found (Wilk's Λ = 0.684, F = 5.714, p < 0.001). We found group differences for both neuroticism (F[3, 83] = 10.907, p < 0.001) and trait rumination (F[3, 83] = 4.831, p = 0.004). Post‐hoc Tukey tests revealed that neuroticism differed between the ‘resilience group’ and the ‘slow recovery group’ (p = 0.002), the ‘resilience group’ and the ‘chronic distress group’ (p < 0.001) and the ‘fast recovery group’ and the ‘chronic distress group’ (p = 0.004). Trait rumination differed between the ‘resilience group’ and the ‘slow recovery group’ (p = 0.021) and between the ‘resilience group’ and the ‘chronic distress group’ (p = 0.041).

Furthermore, a between‐group difference was found for the brooding rumination subscale, which remained significant after Welch's correction for non‐homogenous variances (F [3, 26.473] = 9.789, p < 0.001), whereas the reflection rumination subscale did not differ between the groups (F[3, 83] = 0.283, p = 0.837). A post‐hoc Games‐Howell test revealed that the ‘resilience group’ significantly scored lower on the brooding rumination subscale than the ‘chronic distress group’ (p = 0.001).

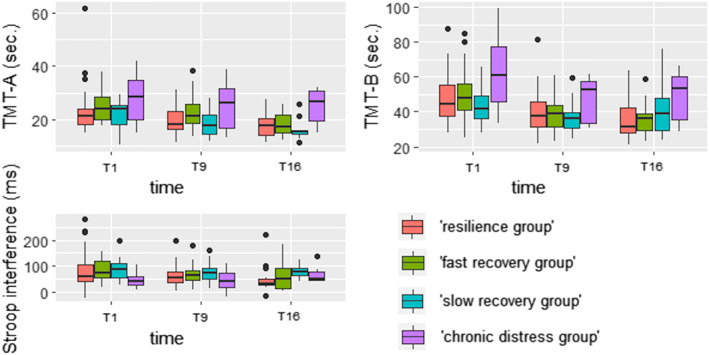

4.6. Trajectory group differences in cognitive control functioning

To investigate the possible involvement of cognitive control functioning, we tested whether the trajectory groups differed regarding (repeated) TMT and Stroop performance. TMT‐A, TMT‐B and Stroop performance per trajectory group is displayed in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Repeated TMT and Stroop task performance among the four (‘resilience’ n = 38, ‘fast recovery’ n = 22, ‘slow recovery’ n = 19, ‘chronic distress’ n = 8) trajectory group. TMT: trail making test

We performed LME analyses for the response variables TMT‐A, TMT‐B and Stroop interference to assess cognitive control functioning at three points in time during the study period and trajectory group differences herein.

Group significantly affected TMT‐A, compared to only time as fixed effect (χ 2(3) = 10.05, p = 0.018). Compared to the ‘resilience group’ as a reference, the ‘chronic distress group’ was found to have a significant effect (estimate = 5.52, SE = 2.16, p = 0.013). Compared to T1 as a reference, T9 (estimate = −2.93, SE = 0.55, p < 0.001) and T16 (estimate = −4.88, SE = 0.68, p < 0.001) had significant effects. Variance of the random intercept subject was 25.96 ± 5.10. No group × time interaction was present. Compared to only time as a fixed effect, there was a significant effect of group (χ 2(3) = 8.35, p = 0.039) for TMT‐B. Also, there was a significant group × time interaction (χ 2(6) = 19.06, p = 0.004). Compared to the ‘resilience group’ as a reference, the ‘chronic distress group’ had a significant effect (estimate = 16.22, SE = 5.00, p = 0.002). Compared to T1 as a reference, T9 (estimate = −6.74, SE = 1.63, p < 0.001) and T16 (estimate = −10.69, SE = 2.08, p < 0.001) had significant effects. Compared to the reference of resilience group × T1, the interaction chronic distress group × T9 (estimate = −8.48, SE = 3.90, p = 0.032) and the interaction slow recovery group × T16 (estimate = 10.74, SE = 3.60, p = 0.003) had significant effects. Variance of the random intercept subject was 115.06 ± 10.73. Post‐hoc Tukey contrasts for the group × time interaction model were computed and the contrast slow recovery group T1‐chronic distress group T1 was found to be significant (estimate = −19.64, SE = 5.42, p = 0.021). Group as well as a group × time interaction did not significantly affect Stroop interference.

4.7. Influence neuroticism and rumination on cognitive control functioning

Additional to the relation between depressive symptom trajectory following breakup and cognitive control functioning, we tested whether the personality traits neuroticism and rumination (separately) affected cognitive control functioning using LME analyses. Compared to only time as a fixed effect, neuroticism significantly affected both TMT‐A (χ 2(1) = 8.14, p = 0.004, estimate = 0.07, SE = 0.07) and TMT‐B (χ 2(1) = 9.12, p = 0.003, estimate = 0.51, SE = 0.17). No neuroticsm × time interaction was found. Neuroticism did not affect Stroop interference. Compared to only time as a fixed effect, trait rumination did not significantly affect TMT performance; neither was this the case for Stroop interference. As trait rumination did not show significant contributions, we opted to not combine the two personality trait variables.

5. DISCUSSION

The first aim of the present study was to explore depressive symptoms over time and group subjects based on their depressive symptom (MDI) trajectory following a potential negative event (i.e., romantic relationship breakup). Subsequently, we aimed to use these distinct trajectories in order to investigate involved factors. Therefore, the second aim was to investigate whether personality traits (rumination, neuroticism) and cognitive control functioning are related to the depressive symptom trajectory.

5.1. Depressive symptom trajectories following relationship breakup

In accordance with previous research concerning various disturbing events (Mancini et al., 2015; Norris et al., 2009), we expected to identify distinct depressive symptom patterns, including resilience, recovery, delayed symptoms and chronic symptoms. In the present study, we first explored different cluster solutions. Via the 2‐cluster solution, it was not possible to identify a subgroup showing elevated depressive symptoms throughout the total study period, even though the data on (several) individual subjects showed this pattern. In addition, in the individual traces, some subjects are clearly affected but recover relatively fast. Again, this is not captured in the 2‐cluster solution. The 3‐cluster and 4‐cluster solution provided a similar interpretation on the trajectories. However, the 3‐cluster solution revealed a less clear distinction between subjects who are able to recover and subjects who show a pattern of chronic symptoms and between subjects who recover at a fast and slow pace, respectively. Via the 4‐cluster solution, we characterised four ‘trajectory groups’; a group of women that reported high depression scores during the total study period (i.e., ‘chronic distress group’), two groups that recovered during the study period (i.e., ‘fast recovery group’ and ‘slow recovery group’) and a group that reported low depression scores during the total study period (‘resilience group’). When considering the 5‐cluster solution, we noted (again) a similar pattern to the 4‐cluster solution. However in this case, the ‘resilience’ cluster got split into two subclusters. The 6‐cluster solution resulted in relatively small cluster sizes. Taken together, the 4‐cluster solution provided the clearest interpretation. It was possible to identify distinct interpretable trajectory clusters including a cluster that reported high (above the clinical cut‐off) depression scores during the total study period. Furthermore, the number of subjects per cluster was sufficient for further analyses. Although the 4‐cluster solution did not score maximally on any of the cluster criterions, its score and the related interpretation was similar to that of either the 3‐cluster or 5‐cluster solution and thus was used in subsequent analyses. Note that we did not observe a cluster of subjects showing delayed symptoms during the study period, which is in contrast to our expectations based on studies by Bonanno (2004) and Mancini et al. (2015).

5.2. Breakup and relationship parameters

To better interpret these four distinct trajectories, we explored breakup and relationship parameters, assessed at the first study visit, and trajectory group differences herein. These results corroborate our characterisations of the trajectory groups. The ‘resilience group’ was found to be unaffected by the breakup (i.e., reporting relatively low levels of heartbreak and related negative thoughts). The ‘fast recovery’ and the ‘slow recovery’ groups seemed to be affected by the breakup (i.e., reporting relatively high levels of heartbreak) at the time of the first study visit. The ‘chronic distress group’ was found to be severely affected by the breakup and suffering from several breakup‐related symptoms, such as intrusive thoughts about the ex‐partner and physical complaints.

5.3. Trajectory group differences in neuroticism and rumination levels

Next, we investigated factors that potentially play a role in the four identified trajectory groups. First, we investigated possible influences of personality traits (rumination and neuroticism). In the present study, we found that personality trait was related to depressive symptom trajectory following romantic relationship breakup. In accordance with our expectations, the ‘slow recovery group’ and the ‘chronic distress group’ were found to have higher neuroticism and trait rumination levels compared to the ‘resilience group’ and the ‘chronic distress group’ also had higher neuroticism levels than the ‘fast recovery group’. Interestingly, when distinguishing between adaptive (i.e., reflection) rumination and maladaptive (i.e., brooding) rumination (Treynor et al., 2003), group‐level differences were only found for brooding rumination; the ‘chronic distress group’ had higher brooding rumination levels than the ‘resilience group’. These results suggest that especially the level of neuroticism distinguishes normal/adaptive behaviour (being able to recover) from experiencing prolonged symptoms in response to a relationship breakup. Previous research among patients with clinical depression as well as healthy individuals already pointed towards a relation between personality traits (neuroticism and ruminative behaviour) and elevated depressive symptoms (Huffziger et al., 2009; Nolen‐Hoeksema, 2000; Nolen‐Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991; Paulus et al., 2016). In addition, a previous study among people who experienced a romantic relationship breakup displayed that trait rumination is an important predictor of breakup distress (measured using a grief questionnaire) after a follow‐up period of 7 months (del Palacio‐González et al., 2017). The results of the present study show that the relation between neuroticism, rumination and depressive symptoms is also present in romantic relationship breakup and can be seen as an indicator of recovery in terms of a depression (‐like) state in people without a history of psychiatric disease.

5.4. Cognitive control functioning

We investigated group‐level differences in cognitive control functioning. In the present study, we found effects of group on cognitive flexibility (i.e., TMT performance). The ‘chronic distress group’ showed worse overall TMT‐A and TMT‐B performance than the ‘resilience group’, indicating impaired cognitive flexibility as well as impairments related to attention and motor speed. This finding is consistent with the considered relation between cognitive control, rumination and depression (Beckwé et al., 2014; Davis & Nolen‐Hoeksema, 2000), as in the present study higher levels of neuroticism and trait rumination were found in the ‘chronic distress group’ as well. Furthermore, an interaction between group and time was found for TMT‐B performance in the present study. The ‘chronic distress group’ had longer completion times than the ‘slow recovery group’ at the first visit. This difference cannot be explained by differences in depressive symptom state as depression scores did not differ between these two groups at the first visit (see Figure 1); both groups reported high depression scores (on average above the clinical depression cut‐off). Contradictory to our expectations, there was no effect of trajectory group on inhibitory control abilities (i.e., Stroop interference).

5.5. Influence of neuroticism and rumination

As a relation between neuroticism and rumination on the one hand, and cognitive control functioning on the other hand has been established in literature (Beckwé et al., 2014; Davis & Nolen‐Hoeksema, 2000), we interrogated this relation in our study sample. We found an increasing effect of neuroticism on TMT‐A and TMT‐B performance, implying that individuals who score higher on neuroticism display worse cognitive flexibility. Interestingly, no effect of rumination on cognitive performance was present. As in our study higher levels of neuroticism were found among women who displayed prolonged distress following breakup, this result suggests an interplay between high neuroticism, persistent symptoms of depression in response to a breakup and impaired cognitive flexibility. A future step, to investigate this suggested interplay further, could be analysing all variables together using a single statistical model. In the present study, we were not able to perform such a statistical analysis, due to the design of the study (i.e., personality, cognitive performance and depressive symptom severity were assessed once, three times and every two weeks, respectively).

5.6. Limitations

Given that we only included women with an age between 18 and 35 years old in our study, we cannot generalise the results of the present study to the general population of people experiencing a relationship breakup. We focussed on young women in the present study in order to include a homogenous group in terms of age and gender. Previous research already showed differences between the genders regarding depressive symptom severity and other breakup‐related symptoms (Verhallen et al., 2019). Furthermore, males and females are known to have different stress responses (Lin et al., 2008) and clinical depression prevalence rates (Kessler et al., 1993). It would be interesting to conduct a similar study with a larger sample size among both men and women and multiple age groups and compare the results to identify possible gender‐specific and age‐specific aspects.

As subjects were included in our study after the occurrence of the breakup, we do not have information about the period prior to this event. Therefore, although personality traits are considered to be generally stable over time (Costa & McCrae, 1980), we cannot rule out the possibility that the breakup has influenced our personality data and consequently between‐group differences. Indeed, a study by Riese et al. (2014) showed increasing effects of stressful life‐events on the level of neuroticism, especially shortly after the life‐event.

A potential weakness of the present study relates to sample size. We grouped our initial study sample into four subgroups in order to assess the relatedness between depressive symptom pattern following breakup and suggested vulnerability factors. We ended up with relatively small groups to proceed with in subsequent analyses. Especially, the number of subjects showing severe distress during the total study period or showing slow recovery (i.e., ‘at risk individuals’) was found to be low. This is due to the study design in which we tried to observe the natural variation in dealing with disturbing events and translate our findings to the general population. Consequently, we have to be careful in drawing strong conclusions, especially when translating these results to clinical depression.

Last, due to the COVID‐19 pandemic and measures taken in the Netherlands, we ended up with substantial missing cognitive task data for the third study visit. Consequently, the data from the third study visit represents a subsample of our initial group. As the missingness of the data is considered to be completely unrelated to any of the outcome measures of our study, we expect that these (potential) effects are minimal.

6. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the findings of the present study show that distinct patterns of depressive symptom severity can be observed following romantic relationship breakup, including prolonged symptoms of depression. Furthermore, personality traits (rumination, neuroticism) and cognitive flexibility seem to play a role in these depressive symptom patterns. Specifically, our findings point towards an interplay between high levels of neuroticism, impaired cognitive flexibility and persistent symptoms of depression in response to a negative event.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that no conflicts of interest exist.

Supporting information

Figure S1

Figure S2

Figure S3

Figure S4

Figure S5

Table S1

Table S2

Table S3

Table S4

Table S5

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the undergraduate students Danieke Lange and Kayleigh van Bussel who contributed to the recruitment of subjects and data acquisition.

The study was funded by a donation of Mr Hazewinkel to the Research School of Behavioural and Cognitive Neurosciences and Prof G.J. ter Horst.

Verhallen, A. M. , Alonso‐Martínez, S. , Renken, R. J. , Marsman, J.‐B. C. , & ter Horst, G. J. (2022). Depressive symptom trajectory following romantic relationship breakup and effects of rumination, neuroticism and cognitive control. Stress and Health, 38(4), 653–665. 10.1002/smi.3123

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data will not be stored at a public repository due to restrictions from the informed consent (subjects have not given consent to have their data publicly stored) and European data privacy regulations (GDPR). The data are available on request via j.b.c.marsman@umcg.nl.

REFERENCES

- Arbuthnott, K. , & Frank, J. (2000). Trail making test, part B as a measure of executive control: Validation using a set‐switching paradigm. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 22(4), 518–528. 10.1076/1380-3395(200008)22:4;1-0;FT518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates, D. , Mächler, M. , Bolker, B. M. , & Walker, S. C. (2015). Fitting linear mixed‐effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1), 1–48. 10.18637/jss.v067.i01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bech, P. , Rasmussen, N. A. , Olsen, L. R. , Noerholm, V. , & Abildgaard, W. (2001). The sensitivity and specificity of the major depression inventory, using the present state examination as the index of diagnostic validity. Journal of Affective Disorders, 66(2–3), 159–164. 10.1016/S0165-0327(00)00309-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bech, P. , Timmerby, N. , Martiny, K. , Lunde, M. , & Soendergaard, S. (2015). Psychometric evaluation of the major depression inventory (MDI) as depression severity scale using the LEAD (longitudinal expert assessment of all data) as index of validity. BMC Psychiatry, 15(190). 10.1186/s12888-015-0529-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckwé, M. , Deroost, N. , Koster, E. H. W. , De Lissnyder, E. , & De Raedt, R. (2014). Worrying and rumination are both associated with reduced cognitive control. Psychological Research, 78(5), 651–660. 10.1007/s00426-013-0517-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno, G. A. (2004). Loss, trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? The American Psychologist, 59(1), 20–28. 10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan, S. W. Y. , Goodwin, G. M. , & Harmer, C. J. (2007). Highly neurotic never‐depressed students have negative biases in information processing. Psychological Medicine, 37(9), 1281–1291. 10.1017/S0033291707000669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa, P. T. , & McCrae, R. R. (1980). Influence of extraversion and neuroticism on subjective well‐being: Happy and unhappy people. Psychological Assessment, 38(4), 668–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa, P. T. , & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Normal personality assessment in clinical practice: The NEO personality inventory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 4(1), 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers, P. , Dekker, J. , Noteboom, A. , Smits, N. , & Peen, J. (2007). Sensitivity and specificity of the major depression inventory in outpatients. BMC Psychiatry, 7. 10.1186/1471-244X-7-39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis, R. N. , & Nolen‐Hoeksema, S. (2000). Cognitive inflexibility among ruminators and nonruminators. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 24(6), 699–711. [Google Scholar]

- del Palacio‐González, A. , Clark, D. A. , & O'Sullivan, L. F. (2017). Cognitive processing in the aftermath of relationship dissolution: Associations with concurrent and prospective distress and posttraumatic growth. Stress and Health, 33(5), 540–548. 10.1002/smi.2738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisma, M. C. , Schut, H. A. W. , Stroebe, M. S. , Boelen, P. A. , van den Bout, J. , & Stroebe, W. (2015). Adaptive and maladaptive rumination after loss: A three‐wave longitudinal study. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 54(2), 163–180. 10.1111/bjc.12067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field, T. , Diego, M. , Pelaez, M. , Deeds, O. , & Delgado, J. (2009). Breakup distress in university students. Adolescence, 44(176), 705–727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, H. E. , Brown, L. L. , Aron, A. , Strong, G. , & Mashek, D. (2010). Reward, addiction, and emotion regulation systems associated with rejection in love. Journal of Neurophysiology, 104(1), 51–60. 10.1152/jn.00784.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, G. J. O. , Simpson, J. A. , & Thomas, G. (2000). The measurement of perceived relationship quality components: A confirmatory factor analytic approach. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26(3), 340–354. 10.1177/0146167200265007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Genolini, C. , & Falissard, B. (2011). Kml: A package to cluster longitudinal data. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, 104(3), e112–e121. 10.1016/j.cmpb.2011.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffziger, S. , Reinhard, I. , & Kuehner, C. (2009). A longitudinal study of rumination and distraction in formerly depressed inpatients and community controls. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 118(4), 746–756. 10.1037/a0016946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler, K. S. , Karkowski, L. M. , & Prescott, C. A. (1999). Causal relationship between stressful life events and the onset of major depression. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 156, 837–841. 10.1176/ajp.156.6.837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, R. C. , McGonagle, K. A. , Swartz, M. , Blazer, D. G. , & Nelson, C. B. (1993). Sex and depression in the national comorbidity survey I: Lifetime prevalence, chronicity and recurrence. Journal of Affective Disorders, 29(2–3), 85–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knöpfli, B. , Morselli, D. , & Perrig‐Chiello, P. (2016). Trajectories of psychological adaptation to marital breakup after a long‐term marriage. Gerontology, 62(5), 541–552. 10.1159/000445056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y. , Westenbroek, C. , Bakker, P. , Termeer, J. , Liu, A. , Li, X. , & Ter Horst, G. J. (2008). Effects of long‐term stress and recovery on the prefrontal cortex and dentate gyrus in male and female rats. Cerebral Cortex, 18(12), 2762–2774. 10.1093/cercor/bhn035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancini, A. D. , Bonanno, G. A. , & Sinan, B. (2015). A brief retrospective method for identifying longitudinal trajectories of adjustment following acute stress. Assessment, 22(3), 298–308. 10.1177/1073191114550816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathôt, S. , Schreij, D. , & Theeuwes, J. (2012). OpenSesame: An open‐source, graphical experiment builder for the social sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 44(2), 314–324. 10.3758/s13428-011-0168-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mineka, S. , Williams, A. L. , Wolitzky‐Taylor, K. , Vrshek‐Schallhorn, S. , Craske, M. G. , Hammen, C. , & Zinbarg, R. E. (2020). Five‐year prospective neuroticism‐stress effects on major depressive episodes: Primarily additive effects of the general neuroticism factor and stress. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 129(6), 646–657. 10.1037/abn0000530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan, S. A. , Roberts, J. E. , & Gotlib, I. H. (1998). Neuroticism and ruminative response style as predictors of change in depressive symptomatology. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 22, 445–455. [Google Scholar]

- Nolen‐Hoeksema, S. (1991). Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100(4), 569–582. 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen‐Hoeksema, S. (2000). The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 190(3), 504–511. 10.1037//0021-843X.1093.504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen‐Hoeksema, S. , & Morrow, J. (1991). A prospective study of depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms after a natural disaster: The 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(1), 115–121. 10.1037//0022-3514.61.1.115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris, F. H. , Tracy, M. , & Galea, S. (2009). Looking for resilience: Understanding the longitudinal trajectories of responses to stress. Social Science & Medicine, 68(12), 2190–2198. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.03.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulus, D. J. , Vanwoerden, S. , Norton, P. J. , & Sharp, C. (2016). Emotion dysregulation, psychological inflexibility, and shame as explanatory factors between neuroticism and depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 190, 376–385. 10.1016/j.jad.2015.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippot, P. , & Agrigoroaei, S. (2017). Repetitive thinking, executive functioning, and depressive mood in the elderly. Aging & Mental Health, 21(11), 1192–1196. 10.1080/13607863.2016.1211619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippot, P. , & Brutoux, F. (2008). Induced rumination dampens executive processes in dysphoric young adults. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 39(3), 219–227. 10.1016/j.jbtep.2007.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riese, H. , Snieder, H. , Jeronimus, B. F. , Korhonen, T. , Rose, R. J. , Kaprio, J. , & Ormel, J. (2014). Timing of stressful life events affects stability and change of neuroticism. European Journal of Personality, 28, 193–200. 10.1002/per.1929 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roelofs, J. , Huibers, M. , Peeters, F. , Arntz, A. , & van Os, J. (2008). Rumination and worrying as possible mediators in the relation between neuroticism and symptoms of depression and anxiety in clinically depressed individuals. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46(12), 1283–1289. 10.1016/j.brat.2008.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoofs, H. , Hermans, D. , & Raes, F. (2010). Brooding and reflection as subtypes of rumination: Evidence from confirmatory factor analysis in nonclinical samples using the Dutch ruminative response scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 32(4), 609–617. 10.1007/s10862-010-9182-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Servaas, M. N. , van der Velde, J. , Costafreda, S. G. , Horton, P. , Ormel, J. , Riese, H. , & Aleman, A. (2013). Neuroticism and the brain: A quantitative meta‐analysis of neuroimaging studies investigating emotion processing. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 37(8), 1518–1529. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoessel, C. , Stiller, J. , Bleich, S. , Boensch, D. , Doerfler, A. , Garcia, M. , Richter‐Schmidinger, T. , Kornhuber, J. , & Forster, C. (2011). Differences and similarities on neuronal activities of people being happily and unhappily in love: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Neuropsychobiology, 64, 52–60. 10.1159/000325076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroop, J. R. (1935). Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 18(6), 643–662. 10.1037/h0054651 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tombaugh, T. N. (2004). Trail making test A and B: Normative data stratified by age and education. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 19(2), 203–214. 10.1016/S0887-6177(03)00039-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treynor, W. , Gonzalez, R. , & Nolen‐Hoeksema, S. (2003). Rumination reconsidered: A psychometric analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 27, 247–259. [Google Scholar]

- Verhallen, A. M. , Renken, R. J. , Marsman, J. B. C. , & ter Horst, G. J. (2019). Romantic relationship breakup: An experimental model to study effects of stress on depression (‐like) symptoms. PLoS One, 14(5), e0217320. 10.1371/journal.pone.0217320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1

Figure S2

Figure S3

Figure S4

Figure S5

Table S1

Table S2

Table S3

Table S4

Table S5

Data Availability Statement

The data will not be stored at a public repository due to restrictions from the informed consent (subjects have not given consent to have their data publicly stored) and European data privacy regulations (GDPR). The data are available on request via j.b.c.marsman@umcg.nl.