Abstract

Scope

The gut microbiota plays a prominent role in gut–brain interactions and gut dysbiosis is involved in neuroinflammation. However, specific probiotics targeting neuroinflammation need to be explored. In this study, the antineuroinflammatory effect of the potential probiotic Roseburia hominis (R. hominis) and its underlying mechanisms is investigated.

Methods and results

First, germ‐free (GF) rats are orally treated with R. hominis. Microglial activation, proinflammatory cytokines, levels of short‐chain fatty acids, depressive behaviors, and visceral sensitivity are assessed. Second, GF rats are treated with propionate or butyrate, and microglial activation, proinflammatory cytokines, histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1), and histone H3 acetyl K9 (Ac‐H3K9) are analyzed. The results show that R. hominis administration inhibits microglial activation, reduces the levels of IL‐1α, INF‐γ, and MCP‐1 in the brain, and alleviates depressive behaviors and visceral hypersensitivity in GF rats. Moreover, the serum levels of propionate and butyrate are increased significantly in the R. hominis‐treated group. Propionate or butyrate treatment reduces microglial activation, the levels of proinflammatory cytokines and HDAC1, and promotes the expression of Ac‐H3K9 in the brain.

Conclusion

These findings suggest that R. hominis alleviates neuroinflammation by producing propionate and butyrate, which serve as HDAC inhibitors. This study provides a potential psychoprobiotic to reduce neuroinflammation.

Keywords: histone deacetylase inhibitor, microglia, neuroinflammation, Roseburia hominis, short‐chain fatty acids

Roseburia hominis, a potential probiotic, alleviates neuroinflammation by producing the metabolites propionate and butyrate. The underlying mechanism of its beneficial effects might be the result of histone deacetylase inhibition of microglia by propionate and butyrate. These findings supply a new solution to alleviate neuroinflammation by manipulating the microbiota in neuropsychiatric diseases.

1. Introduction

Neuroinflammation generally refers to the inflammatory response within the central nervous system (CNS), which can be caused by various pathological stimuli, including infection, trauma, ischemia, and toxins. The process is always accompanied by the release of a series of cytokines, such as IL‐1β, IL‐6, IL‐18, and TNF‐α, and chemokines, such as MCP‐1 and CCL5.[ 1 ] Under pathological circumstances, activated microglia produce increased amounts of inflammatory factors, which could aid in pathogen or toxin clearance but also lead to neuronal dysfunction and damage.[ 2 ] Neuroinflammation plays an essential role in the initiation of Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and major depressive disorder.[ 3 , 4 , 5 ] Inhibition of neuroinflammation significantly improved CNS injury and prevented the pathogenesis of relevant neurological disorders.[ 2 , 6 , 7 ] Therefore, suppression of neuroinflammation is one of the most promising methods to treat these neurodegenerative diseases or brain injuries.

The gut microbiota communicates closely with the CNS, thereby modulating brain function and behavior.[ 8 ] Recent studies have reported that intestinal microbiota influence neuroinflammation through the gut‐brain axis.[ 9 ] In our previous study, oral administration of Roseburia hominis (R. hominis), an obligate gram‐positive anaerobic bacterium, significantly improved visceral hypersensitivity in a chronic water avoidance stress‐induced rat model and reduced the level of corticotropin‐releasing hormone in serum,[ 10 ] but whether R. hominis could influence neuroinflammation and its underlying mechanisms remain unknown. R. hominis is characterized by short‐chain fatty acid (SCFA) production.[ 11 ] SCFAs can cross the blood–brain barrier and regulate the immune function of microglia.[ 12 ] However, whether R. hominis can improve neuroinflammation by promoting SCFA production is still unclear.

Germ‐free (GF) animals exhibit abnormal behavior and physiological function. In this study, GF rats were utilized to assess the effect of R. hominis on neuroinflammation by detecting microglial activation. We also evaluated the influence of R. hominis on the serum SCFA levels and the expression of histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1). This study provides a new way to alleviate neuroinflammation by supplementation with the potential psychoprobiotic R. hominis.

2. Results

2.1. R. hominis Reduced Neuroinflammation in GF Rats

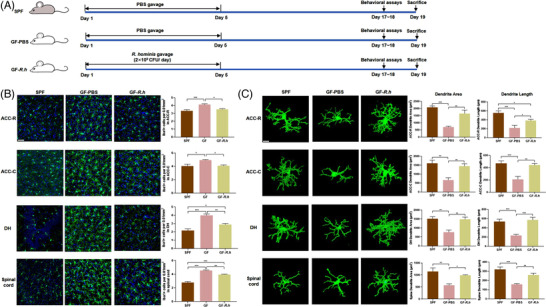

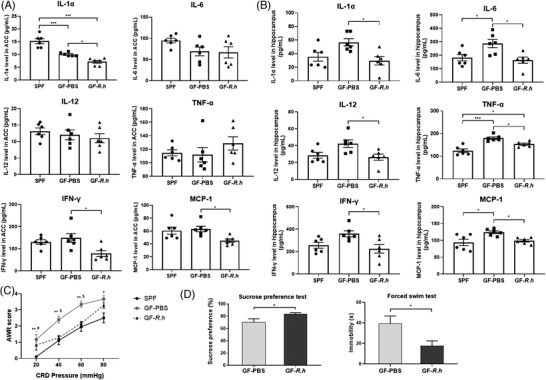

To investigate the effects of R. hominis on neuroinflammation, GF rats were treated with R. hominis or sterile phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS) (Figure 1A). GF rats showed increased numbers of Iba‐1‐positive cells in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC)‐rostral (ACC‐R), ACC‐caudal (ACC‐C), and dorsal hippocampus (DH) brain regions and lumbar spinal cord, and decreased dendrite area and dendrite length of Iba‐1‐positive cells with an amoeboid phenotype compared to SPF rats (Figure 1B,C). Compared to PBS gavage, oral administration of R. hominis at 2 × 109 CFU day‐1 for 5 days significantly reduced the number of microglia in the ACC‐R, ACC‐C, and DH brain regions and lumbar spinal cord (Figure 1B). The activation of microglia in these regions was inhibited by R. hominis treatment, as demonstrated by a significantly smaller dendrite area and shorter dendrite length (Figure 1C). Moreover, the levels of IL‐6, TNF‐α, and MCP‐1 in the hippocampus were significantly higher in GF rats than in SPF rats. The levels of IL‐1α, INF‐γ, and MCP‐1 in the ACC and IL‐1α, IL‐6, IL‐12, TNF‐α, INF‐γ, and MCP‐1 in the hippocampus significantly decreased after R. hominis treatment (Figure 2A,B; Table S1,S2,Supporting Information).

Figure 1.

R. hominis reduced microglial activation in germ‐free rats. A) Experimental design of the R. hominis treatment. B) Representative images of Iba‐1‐stained microglia and the microglia count in the anterior cingulate cortex‐rostral (ACC‐R), ACC‐caudal (ACC‐C), dorsal hippocampus (DH), and spinal dorsal horn L6‐S1 of rats detected by immunofluorescence staining. Scale bar = 50 µm. n = 6–9. Microglia, green; nuclei, blue. One‐way ANOVA with Tukey's post‐hoc test. C) Representative three‐dimensional reconstructions of Iba‐1‐stained microglia and morphological parameters of microglia in the ACC‐R, ACC‐C, DH, and spinal cord. Scale bar = 10 µm. n = 6–9. One‐way ANOVA with Tukey's post‐hoc test. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

Figure 2.

Effects of R. hominis on the levels of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines in the rat brain. Male SPF rats were orally treated with PBS for 5 days. Male GF rats were treated with R. hominis bacterial suspension (2 × 109 CFU day−1, GF‐R.h) or PBS (GF‐PBS) for 5 days. Behavioral experiments were performed 12 days after gavage. Cytokine (IL‐1α, IL‐6, IL‐12, TNF‐α, INF‐γ) and chemokine (MCP‐1) levels were determined 14 days after gavage. A) Levels of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) (n = 6). B) Levels of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines in the hippocampus (n = 6). *, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001. One‐way ANOVA with Tukey's post‐hoc test. C) Comparison of AWR scores among SPF, GF‐PBS, and GF‐R.h rats (n = 6–13). *, SPF versus GF‐PBS, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01; #, SPF versus GF‐R.h, # p < 0.05; $, GF‐PBS versus GF‐R.h, $ p < 0.05. One‐way ANOVA with Tukey's post‐hoc test. AWR, abdominal withdrawal reflex. D) The sucrose preference rate and immobility time between GF‐PBS and GF‐R.h rats (n = 6). *p < 0.05. Unpaired Student's t test.

GF rats presented increased visceral sensitivity compared with SPF rats. R. hominis treatment significantly alleviated visceral hypersensitivity in GF rats (Figure 2C). In addition, R. hominis increased the sucrose preference rate and reduced immobility time in the forced swim test (Figure 2D,E).

2.2. R. hominis Reduced Neuroinflammation through the Production of Propionate and Butyrate in GF Rats

SCFA levels in rat serum were measured 14 days after gavage by ultra‐performance liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC–MS/MS). Serum propionate, butyrate, and isobutyrate levels in GF rats were significantly lower than those in SPF rats, while R. hominis treatment significantly increased the serum propionate and butyrate levels in GF rats. There was no significant variation in acetate, isobutyrate, valerate, or isovalerate levels between GF‐PBS and GF‐R.h rats (Figure 3 ; Table S3, Supporting Information).

Figure 3.

Serum concentration of SCFAs in rats. Male SPF rats were orally treated with PBS for 5 days. Male GF rats were treated with R. hominis bacterial suspension (2 × 109 CFU day−1, GF‐R.h) or PBS (GF‐PBS) for 5 days. Acetate A), propionate B), butyrate C), isobutyrate D), valerate E), and isovalerate F) were measured 14 days after gavage (n = 6). Brown‐Forsythe and Welch ANOVA test with Dunnett's T3 post‐hoc test. *, p < 0.05. SCFAs, short‐chain fatty acids.

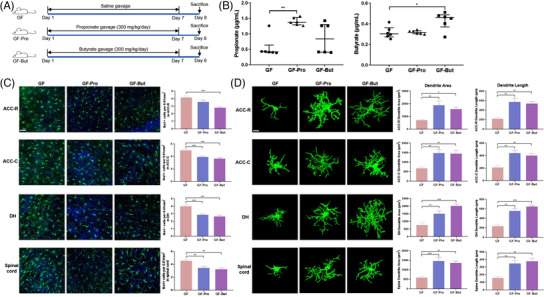

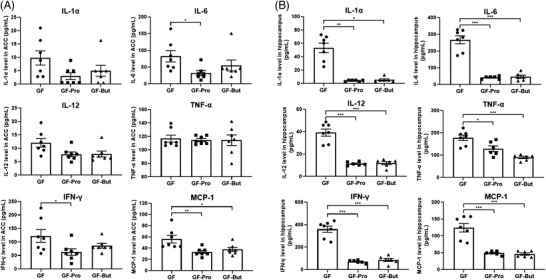

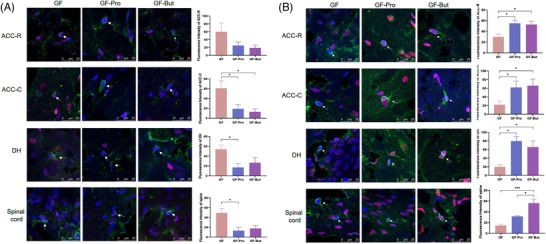

To investigate the effects of propionate and butyrate on neuroinflammation, GF rats were treated with sodium propionate or sodium butyrate (Figure 4A). Oral gavage of sodium propionate significantly increased the serum propionate content (GF vs GF‐Pro:0.55 ± 0.14 µg mL−1 vs 1.40 ± 0.05 µg mL‐1, p < 0.01), and butyrate treatment significantly increased the serum butyrate level in GF rats (GF vs GF‐But:0.32 ± 0.02 µg mL−1 vs 0.43 ± 0.03 µg mL, p < 0.05) (Figure 4B). Oral gavage with sodium propionate or butyrate significantly reduced the number of microglia (Figure 4C) and significantly reduced the dendrite length and area of microglia in GF rats (Figure 4D), suggesting that propionate and butyrate inhibited the activation of microglial cells. Moreover, the levels of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines in GF rats decreased in the ACC and hippocampus after gavage with propionate or butyrate. Specifically, the levels of IL‐6, IFN‐γ, and MCP‐1 in the ACC and IL‐1α, IL‐6, IL‐12, TNF‐α, IFN‐γ, and MCP‐1 in the hippocampus were significantly decreased compared with those in the GF group after administration of sodium propionate. The levels of MCP‐1 in the ACC and IL‐1α, IL‐6, IL‐12, TNF‐α, IFN‐γ, and MCP‐1 in the hippocampus were significantly reduced compared with those in the GF group after administration of sodium butyrate (Figure 5 ; Table S4,S5, Supporting Information).

Figure 4.

Propionate or butyrate reduced microglial activation in germ‐free (GF) rats. A) Experimental design of the propionate and butyrate treatments. B) Serum concentrations of propionate and butyrate in GF, GF‐Pro, and GF‐But rats (n = 6). Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn's multiple comparison post hoc test. C) Representative images of Iba‐1‐stained microglia and the microglia count in the anterior cingulate cortex‐rostral (ACC‐R), ACC‐caudal (ACC‐C), dorsal hippocampus (DH), and spinal dorsal horn L6‐S1 of rats detected by immunofluorescence staining (n = 6). Scale bar = 50 µm. Microglia, green; nuclei, blue. One‐way ANOVA with Tukey's post‐hoc test. D) Representative three‐dimensional reconstructions of Iba‐1‐stained microglia and morphological parameters of microglia in the ACC‐R, ACC‐C, DH, and spinal cord (n = 6). Scale bar = 10 µm. One‐way ANOVA with Tukey's post‐hoc test. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

Figure 5.

Propionate and butyrate significantly reduced the levels of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines in the rat brain. Germ‐free rats were orally administered PBS (GF), sodium propionate (300 mg kg−1, GF‐Pro) or sodium butyrate (300 mg kg−1, GF‐But) for 7 days. Cytokine (IL‐1α, IL‐6, IL‐12, TNF‐α, INF‐γ) and chemokine (MCP‐1) levels were measured after treatment. A) Levels of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines in the ACC (n = 7). B) Levels of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines in the hippocampus (n = 6–7). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001. One‐way ANOVA. GF‐But, GF‐butyrate; GF‐Pro, GF‐propionate.

2.3. Propionate and Butyrate Inhibited HDAC1 Expression and Increased histone H3 acetyl K9 (Ac‐H3K9) Levels in Microglia in GF Rats

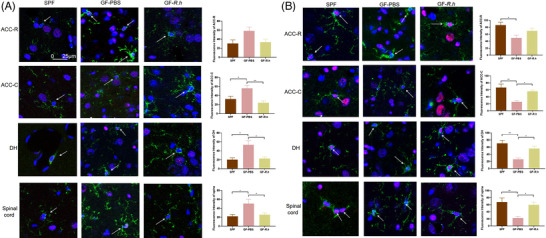

Propionate and butyrate are inhibitors of HDAC in vivo and affect the acetylation level of histones in chromosomes.[ 13 ] Studies from different animal models have shown that altered levels of histone acetylation and deacetylation can lead to abnormal transcription of nociception‐related genes, causing inflammatory or neuropathic pain.[ 14 ] Therefore, we measured HDAC1 and Ac‐H3K9 levels in microglia. The expression of HDAC1 in Iba‐1‐labeled microglia in the DH and lumbar spinal cord was significantly higher in the GF group than in the SPF group (p < 0.05). After gavage with sodium propionate or sodium butyrate, the expression of HDAC1 in microglia in the ACC‐C and DH brain regions and lumbar spinal cord were significantly decreased compared with that in the GF group (Figure 6A). After gavage with sodium propionate, Ac‐H3K9 levels in microglia of the ACC‐C and lumbar spinal cord were significantly increased. Moreover, after supplementation with sodium butyrate, Ac‐H3K9 levels in microglia of ACC‐C, DH, and lumbar spinal cord were significantly increased (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Propionate and butyrate inhibited HDAC1 expression and increased Ac‐H3K9 levels in microglia in GF rats. Germ‐free rats were orally administered PBS (GF), sodium propionate (300 mg kg−1, GF‐Pro) or sodium butyrate (300 mg kg−1, GF‐But) for 7 days. A) The expression of HDAC1 in microglia (n = 6). Microglia, green; HDAC1, red; nuclei, blue. B) The level of Ac‐H3K9 in microglia (n = 6). Microglia, green; Ac‐H3K9, red; nuclei, blue. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

2.4. R. hominis Inhibited HDAC1 Expression and Increased Ac‐H3K9 Levels in Microglia in GF Rats

The HDAC1 and Ac‐H3K9 levels were also measured in microglia of R. hominis‐treated rats. R. hominis treatment significantly reduced the levels of HDAC1 in microglia in the ACC‐C and DH brain regions and lumbar spinal cord (Figure 7A). In addition, Ac‐H3K9 levels in microglia in the ACC‐C, DH, and lumbar spinal cord were significantly increased (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

R. hominis inhibited the HDAC1 expression and increased the Ac‐H3K9 levels of microglia in GF rats. Male SPF rats were orally treated with PBS for 5 days. Male GF rats were treated with R. hominis bacterial suspension (2 × 109 CFU day−1, GF‐R.h) or PBS (GF‐PBS) for 5 days. A) The expression of HDAC1 in microglia (n = 6). Microglia, green; HDAC1, red; nuclear, blue. Scale bar = 25 µm. B) The level of Ac‐H3K9 in microglia (n = 6). Microglia, green; Ac‐H3K9, red; nuclear, blue. Scale bar = 25 µm. *, p < 0.05;**, p < 0.01.

3. Discussion

The gut microbiota influences not only gastrointestinal physiology but also CNS function. During dysbiosis, the microbiota‐gut‐brain axis is dysregulated, which is associated with neuroinflammation.[ 15 ] However, the mechanisms through which gut microbiota influence neuroinflammation are not fully clear. In this study, we demonstrated that R. hominis, a potential probiotic, alleviated neuroinflammation by producing the metabolites propionate and butyrate. Moreover, the underlying mechanism of its beneficial effects might be the result of HDAC inhibition of microglia by propionate and butyrate.

An increasing number of studies have focused on the strong link between gut microbiota and neuroinflammation. In previous research, Clostridium butyricum treatment attenuated microglia‐mediated neuroinflammation by regulating the gut microbiota‐gut‐brain axis.[ 9 ] Agathobaculum butyriciproducens administration improved cognitive function and decreased microglial activation in the hippocampus in a lipopolysaccharide‐induced cognitive deficit model.[ 16 ] In addition, the absence of microbiota colonization causes GF animals to show abnormal behavior and physiological function, such as increased anxiety‐like behaviors[ 17 ] and visceral hypersensitivity.[ 18 ] GF mice showed higher gene expression levels of some cytokines, including TNF‐α, IL‐1α, and IL‐1β, and glial activation in the spinal cord than conventionally raised mice. Microbial colonization normalized the spinal cord inflammatory profile and visceral hypersensitivity of GF mice.[ 18 ] In our study, R. hominis administration mitigated neuroinflammation, depressive behaviors, and visceral hypersensitivity in GF rats. Therefore, R. hominis might serve as an ideal method for treating neurological disorders related to neuroinflammation caused by gut dysbiosis.

Roseburia belongs to the gram‐positive obligate anaerobes and includes five species, R. intestinalis, R. hominis, R. inulinivorans, R. faecis, and R. cecicola. Roseburia is an intestinal symbiotic bacterium that accounts for 3–15% of the total fecal bacteria in healthy volunteers.[ 11 ] Our previous study showed that the abundance of Roseburia in the feces of rats after water avoidance stress was significantly lower than that of control rats and that oral gavage with R. hominis significantly alleviated visceral hypersensitivity in the model rats,[ 10 ] which was consistent with this study; however, the mechanisms were not fully understood. We also found that R. hominis can promote intestinal melatonin synthesis by increasing 5‐HT levels and promoting p‐CREB‐mediated Aanat transcription, offering a potential target for ameliorating intestinal diseases.[ 19 ] Interestingly, this study demonstrated that R. hominis alleviated neuroinflammation in addition to exerting its benefits effects on the digestive systems, suggesting that R. hominis had protective effects on multiple organs of the host, and inhibition of neuroinflammation might be one of the mechanisms by which it improves visceral hypersensitivity. Plenty of evidence revealed the relationship between R. hominis and neuropsychiatric disorders. Our previous study found that patients with depression had lower abundance of Roseburia in fecal microbiota compared to healthy controls.[ 20 ] There was strong correlation between lower abundance of fecal R. hominis and higher odds of positive p‐tau status.[ 21 ] Keshavarzian et al.[ 22 ] found that Roseburia was less abundant in fecal samples of patients with Parkinson's disease compared to healthy controls, indicating that lower abundance of Roseburia could have harmful effects in the pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease.

Roseburia can produce SCFAs by decomposing nonabsorbable carbohydrates in the intestine.[ 23 ] High‐fiber diet increased the SCFAs and the butyrate‐producing organisms like Roseburia.[ 24 ] In this study, germ‐free rats with a clean gut bacteria background were used and fed on the same sterile standard pellet. Confounders of diet and other bacteria were ruled out to the fullest. SCFAs are beneficial bacterial metabolites that can regulate intestinal physiology and immune homeostasis by regulating the levels of inflammatory factors.[ 25 ] The main metabolites of R. hominis are propionate and butyrate.[ 11 ] Propionate and butyrate can provide energy for intestinal epithelial tissue and can also be transported into the brain via the systemic circulation.[ 26 ] Our results demonstrated that R. hominis treatment increased the levels of propionate and butyrate in the serum of GF rats, while acetate, isobutyrate, valerate, and isovalerate did not show significant variation. Moreover, supplementation with propionate or butyrate reduced microglial activation and the release of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines in the ACC and hippocampus of GF rats, indicating that R. hominis alleviated neuroinflammation through the production of propionate and butyrate. SCFAs can also affect metabolic functions, including lipid metabolism, glucose metabolism, and appetite,[ 27 , 28 ] which are closely related to the microglial activation and neuroinflammation.[ 29 ] In this study, some metabolic parameters showed no significant variation among GF, GF‐Pro, and GF‐But group (Figure S1, Supporting Information), hinting that SCFAs affect neuroinflammation not through the direct metabolic pathway.

A previous study reported that butyrate could mitigate inflammation by suppressing NF‐κB p65 and AKT signaling and activating the G protein‐coupled receptor 109A.[ 9 , 30 ] Propionate could exert neuroprotective effects by reducing NF‐κB nuclear translocation and IκBα degradation, as well as decreasing COX‐2 and iNOS expression.[ 31 ] In addition, propionate and butyrate are widely known as endogenous HDAC inhibitors, and they can directly suppress the expression of HDACs and promote hyperacetylation of histones.[ 26 ] HDAC1 is involved in brain development and is related to a range of neuropsychiatric diseases, including depression, schizophrenia, and Alzheimer's disease.[ 32 ] Evidence has proven that HDACs can epigenetically regulate the gene expression and inflammatory responses of glial cells during immune activation.[ 33 ] Inhibition of HDACs alleviates microglia‐mediated neuroinflammation, as revealed by several studies. A study showed that inhibiting HDACs with suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid suppressed the activation of glial cells and the accompanying neuroinflammation in the spinal dorsal horn and dorsal root ganglia in a bone cancer pain rat model.[ 34 ] HDAC inhibitors strongly suppress LPS‐induced cytokine release by microglia, and the expression of M1‐ and M2‐associated activation markers is also suppressed, suggesting that HDAC inhibitors suppress innate immune activation in microglia.[ 35 ] Another study explained that HDAC inhibitors suppress the expression of proinflammatory mediators in LPS‐challenged glial cultures by affecting the DNA binding activity of NF‐κB and AP1, two essential transcription factors that are relevant to immune activation.[ 33 ] In this study, propionate and butyrate inhibited HDAC1 expression and increased Ac‐H3K9 levels in microglia in GF rats, and R. hominis treatment had similar effects as propionate and butyrate, suggesting that propionate and butyrate, produced by R. hominis, served as HDAC inhibitors to alleviate neuroinflammation. Moreover, except for the direct inhibition on HDAC, propionate and butyrate interact with several kinds of G protein‐coupled receptors to modulate a series of biological functions.[ 36 ] More studies need to be conducted to explore whether SCFA receptors are involved in the neuroprotection and the underlying mechanisms.

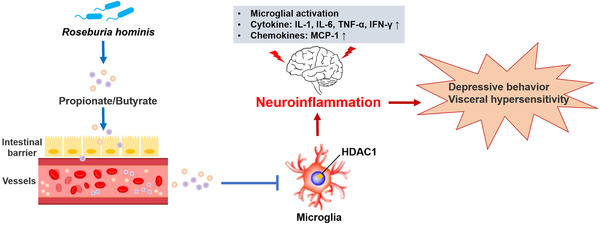

In conclusion, R. hominis mitigated neuroinflammation by producing propionate and butyrate, which serve as HDAC inhibitors (Figure 8 ) and potential psychoprobiotics. These findings supplied a new solution to alleviate neuroinflammation by manipulating the microbiota in neuropsychiatric diseases, which enriches the theory of the microbiota‐gut‐brain axis from a new perspective.

Figure 8.

Proposed model of the effect of Roseburia hominis on neuroinflammation. R. hominis, a potential probiotic, alleviated neuroinflammation by producing the metabolites propionate and butyrate. The underlying mechanism of its beneficial effects might be the result of HDAC inhibition of microglia by propionate and butyrate.

4. Experimental Section

Animal Model and Grouping

Male GF Sprague‐Dawley (SD) rats and SPF SD rats (7 weeks old, 350 g ± 20 g) were maintained as previously described.[ 10 ] GF rats were housed separately in standard polypropylene cages with a wire mesh top, kept under standard conditions. They were fed a sterile standard pellet diet which mainly contained corn, bean pulp, and wheat bran. All ethical guidelines of studies on animals were followed carefully. The study was divided into two parts. In the first experiment, male SPF rats were administered sterile PBS by gavage for 5 days, serving as a control. Male GF rats were randomized into two groups, which were treated with fresh R. hominis bacterial suspension (2 × 109 CFU day‐1, GF‐R.h) or PBS (GF‐PBS) by intragastric administration for 5 days. Behavioral experiments were performed 12 days after gavage. Two weeks after gavage, rats were anesthetized and sacrificed by intraperitoneal injection of 1% sodium pentobarbital. In the second experiment, GF rats were randomized into three groups. Referred to the previous study[ 19 ] as well as the relevant literature,[ 37 ] rats were orally administered sodium propionate (300 mg kg−1) as GF‐Pro group, sodium butyrate (300 mg kg−1) as GF‐But group, and PBS as control, respectively, for 7 days. Then, all the rats were anesthetized and sacrificed by intraperitoneal injection of 1% sodium pentobarbital. All protocols were approved by the Laboratory Animal Welfare Ethics branch of the Biomedical Ethics Committee of Peking University (Approval No. LA2020509).

Dosage Information of R. hominis

R. hominis was prepared as previously described.[ 10 ] Briefly, bacteria were cultured in synthetic yeast casitone fatty acid medium. R. hominis was harvested by centrifugation at 5000 rpm for 5 min and resuspended in sterile PBS after cultivation at 37 °C for 16 h. A fresh bacterial cell suspension was prepared daily, and GF rats were orally administered a concentration of 2 × 109 CFU per day or PBS of the same volume for 5 days.

Immunofluorescence Staining

The fluorescence intensity of Ac‐H3K9 and HDAC1 in microglia was assessed by double immunofluorescence staining. Briefly, rats were sedated and transcardially perfused with normal saline solution. The brains and spinal cords were removed and fixed in 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde. Thirty‐five micrometer parasagittal sections of the brain and cross‐sectional sections of the L6‐S1 spinal cord were incubated with antibodies against Iba‐1 (Abcam ab5076, 1:200), histone Ac‐H3K9 (Abcam ab10812, 1:400), and HDAC1 (Abcam ab19845, 1:400). Microglia were marked by Iba‐1 in the ACC‐R, ACC‐C, DH, and spinal dorsal horn L6‐S1 of rats, and the fluorescence intensity of Ac‐H3K9 and HDAC1 in microglia was assessed by immunofluorescence staining. Section imaging was performed with a Leica SP8 confocal laser scanning microscope with a 40× objective (NA 1.32) and 0.75 zoom (Leica Biosystems, IL, USA). Two‐dimensional merge, three‐dimensional max image processing, and fluorescence intensity were assessed by using Leica LAS X software.

The number of Iba‐1‐positive cells was assessed by Leica LAS X software (Iba‐1 antibody, Wako 019–19741, 1:200). The data were presented as the mean number of cells in a 368 µm × 368 µm field of view. For three‐dimensional reconstruction, Z stacks were imaged with 1‐µm steps in the z direction with a resolution of 1024 × 1024 pixels and analyzed using IMARIS software (Bitplane, Oxford Instrument Company, Concord, MA, USA). Semiautomated reconstruction of microglial cell bodies and processes was performed, and the dendrite area and process length were quantified. Three cells per slice per region from six animals per group were analyzed.

Assessment of Cytokines and Chemokines

Cytokines, including IL‐1α, IL‐6, IL‐12, IFN‐γ, and TNF‐α, and the chemokine MCP‐1 in the ACC and hippocampus were assessed using a Bio‐Plex Pro Rat Cytokine 23‐Plex Assay (#12005641, Bio–Rad, CA, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. In brief, the protein extracted from the brain was incubated in 96‐well plates embedded with microbeads for 1 h and then incubated with the detection antibody for 30 min. Subsequently, streptavidin‐phycoerythrin was added to each well for 10 min, and the absorbance was read using a Bio‐Plex MAGPIX System (Bio–Rad).

Behavioral Assays

The sucrose preference test and forced swim test were used to assess depressive behavior as previously described.[ 38 ] The abdominal withdrawal reflex (AWR) score to colorectal distension was used to evaluate visceral sensitivity as previously described: 0, no behavioral response; 1, brief head movement followed by immobility; 2, contraction of abdominal muscles; 3, lifting of abdomen; 4, body arching and lifting of pelvic structures.[ 10 ]

Quantification of Serum SCFAs

The concentrations of SCFAs, including acetate, propionate, butyrate, isobutyrate, valerate, and isovalerate, in the serum of rats were detected by UPLC–MS/MS. Briefly, approximately 500 µL of serum was homogenized in 1 mL of 50% aqueous acetonitrile and centrifuged. For derivatization, 40 µL of supernatant was mixed with 20 µL of 200 mM 3‐nitrophenylhydrazine and 20 µL of 120 mM N‐(3‐dimethylaminopropyl)‐N0‐ethylcarbodiimide·HCl‐6% pyridine solution. The mixture was reacted at 40 °C for 30 min, and the solution was diluted to 800 µL with 10% aqueous acetonitrile, of which 10 µL was injected for measurement. An Ultimate 3000 RSLC system (Dionex Inc., Amsterdam, The Netherlands) coupled to a TSQ Quantiva Ultra triple‐quadrupole mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) was used for SCFA detection, and the final data were processed using Xcalibur 3.0.63 software (Thermo Fisher). The data were expressed as µg SCFA mL−1 serum content.

Statistical Methods

Variables were expressed as the means ± standard errors for normally distributed data. Unpaired Student's t‐test was used for two‐group comparisons, and one‐way ANOVA was used for multiple‐group comparisons. Analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software (version 8.0, GraphPad Software Inc., USA). All tests were two‐sided, and p < 0.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

L.S., Q.S., H.Z. contributed equally to this work. L.D., Q.S., and L.S. designed the experiments. L.D. obtained funding. Q.S., L.S., H.Z., Y.Z., and Y.W. conducted the animal experiments and sample analyses. Q.S. and L.S. analyzed and interpreted the data. L.S. and Q.S. wrote the draft of the manuscript. L.D. and S.L. performed critical revisions of the manuscript.

Supporting information

Supporting Information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2019YFA0905600) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82170557). The authors would like to thank the Institute of Acupuncture and Moxibustion China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences for their kind help with the barostat used in the rat model. The authors would also like to thank the Metabolomics Facility at Technology Center for Protein Sciences in Tsinghua University for their expert assistance with the measurement of serum SCFAs.

Song L., Sun Q., Zheng H., Zhang Y., Wang Y., Liu S., Duan L., Roseburia hominis Alleviates Neuroinflammation via Short‐Chain Fatty Acids through Histone Deacetylase Inhibition. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2022, 66, 2200164. 10.1002/mnfr.202200164

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Disabato D. J., Quan N., Godbout J. P., J. Neurochem. 2016, 139, 136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Leng F., Edison P., Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2021, 17, 157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tischer J., Krueger M., Mueller W., Staszewski O., Prinz M., Streit W. J., Bechmann I., Glia. 2016, 64, 1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kustrimovic N., Marino F., Cosentino M., Curr. Med. Chem. 2019, 26, 3719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Troubat R., Barone P., Leman S., Desmidt T., Cressant A., Atanasova B., Brizard B., El Hage W., Surget A., Belzung C., Camus V., Eur. J. Neurosci. 2021, 53, 151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Li W., Ali T., He K., Liu Z., Shah F. A., Ren Q., Liu Y., Jiang A., Li S., Brain Behav. Immun. 2021, 92, 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gordon R., Albornoz E. A., Christie D. C., Langley M. R., Kumar V., Mantovani S., Robertson A. A. B., Butler M. S., Rowe D. B., O'Neill L. A., Kanthasamy A. G., Schroder K., Cooper M. A., Woodruff T. M., Sci. Transl. Med. 2018, 10, eaah4066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sharon G., Sampson T. R., Geschwind D. H., Mazmanian S. K., Cell 2016, 167, 915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sun J., Xu J., Yang Bo, Chen K., Kong Yu, Fang Na, Gong T., Wang F., Ling Z., Liu J., Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2020, 64, 1900636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhang J., Song L., Wang Y., Liu C., Zhang Lu, Zhu S., Liu S., Duan L., J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 34, 1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tamanai‐Shacoori Z., Smida I., Bousarghin L., Loreal O., Meuric V., Fong S. B., Bonnaure‐Mallet M., Jolivet‐Gougeon A., Future Microbiol. 2017, 12, 157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wenzel T. J., Gates E. J., Ranger A. L., Klegeris A., Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2020, 105, 103493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Silva L. G., Ferguson B. S., Avila A. S., Faciola A. P., J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 96, 5244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Khangura R. K., Bali A., Jaggi A. S., Singh N., Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 795, 36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rutsch A., Kantsjö J. B., Ronchi F., Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 604179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Go J., Chang D.‐Ho, Ryu Y.‐K., Park H.‐Y., Lee In.‐B., Noh J.‐R., Hwang D. Y., Kim B.‐C., Kim K.‐S., Lee C.‐Ho., Nutr. Res. 2021, 86, 96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Crumeyrolle‐Arias M. Le, Jaglin M., Bruneau A., Vancassel S., Cardona A., Daugé V., Naudon L., Rabot S., Psychoneuroendocrinology 2014, 42, 207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Luczynski P., Tramullas M., Viola M., Shanahan F., Clarke G., O'mahony S., Dinan T. G., Cryan J. F., Elife 2017, 6, e25887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Song L., He M., Sun Q., Wang Y., Zhang J., Fang Y., Liu S., Duan L., Nutrients 2021, 14, 117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liu Y., Zhang L., Wang X., Wang Z., Zhang J., Jiang R., Wang X., Wang K., Liu Z., Xia Z., Xu Z., Nie Y., Lv X., Wu X., Zhu H., Duan L., Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 14, 1602.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Verhaar B. J. H., Hendriksen H. M. A., De Leeuw F. A., Doorduijn A. S., Van Leeuwenstijn M., Teunissen C. E., Barkhof F., Scheltens P., Kraaij R., Van Duijn C. M., Nieuwdorp M., Muller M., Van Der Flier W. M., Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 794519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Keshavarzian A., Green S. J., Engen P. A., Voigt R. M., Naqib A., Forsyth C. B., Mutlu E., Shannon K. M., Mov. Disord. 2015, 30, 1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. David L. A., Maurice C. F., Carmody R. N., Gootenberg D. B., Button J. E., Wolfe B. E., Ling A. V., Devlin A. S., Varma Y., Fischbach M. A., Biddinger S. B., Dutton R. J., Turnbaugh P. J., Nature 2014, 505, 559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Morrison D. J., Preston T., Gut Microbes 2016, 7, 189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Machiels K., Joossens M., Sabino J., De Preter V., Arijs I., Eeckhaut V., Ballet V., Claes K., Van Immerseel F., Verbeke K., Ferrante M., Verhaegen J., Rutgeerts P., Vermeire S., Gut 2014, 63, 1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dalile B., Van Oudenhove L., Vervliet B., Verbeke K., Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhang L., Liu C., Jiang Q., Yin Y., Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 32, 159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Perry R. J., Peng L., Barry N. A., Cline G. W., Zhang D., Cardone R. L., Petersen K. F., Kibbey R. G., Goodman A. L., Shulman G. I., Nature 2016, 534, 213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chausse B., Kakimoto P. A., Kann O., Semin Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 112, 137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chen G., Ran X., Li B., Li Y., He D., Huang B., Fu S., Liu J., Wang W., EBioMedicine 2018, 30, 317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Filippone A., Lanza M., Campolo M., Casili G., Paterniti I., Cuzzocrea S., Esposito E., Neuropharmacology 2020, 166, 107977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. D'Mello S. R., Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2020, 50, 74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Faraco G., Pittelli M., Cavone L., Fossati S., Porcu M., Mascagni P., Fossati G., Moroni F., Chiarugi A., Neurobiol. Dis. 2009, 36, 269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. He X. T., Hu X. F., Zhu C., Zhou K. X., Zhao W. J., Zhang C., Han X., Wu C.‐Le., Wei Y. Y., Wang W., Deng J. P., Chen Fa‐M., Gu Z.‐X., Dong Y.‐L., J. Neuroinflammation 2020, 17, 125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kannan V., Brouwer N., Hanisch U.‐K., Regen T., Eggen B. J. L., Boddeke H. W. G. M., J. Neurosci. Res. 2013, 91, 1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sivaprakasam S., Prasad P. D., Singh N., Pharmacol. Ther. 2016, 164, 144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wang D., Liu C.‐D., Li H.‐F., Tian M.‐Li, Pan J.‐Q., Shu G., Jiang Q.‐Y., Yin Yu.‐L., Zhang L., Metabolism. 2020, 102, 154011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Walker A. K., Wing E. E., Banks W. A., Dantzer R., Mol. Psychiatry 2019, 24, 1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.