Abstract

Objective

Clinicians' fears of taking away patients' hope is one of the barriers to advance care planning (ACP). Research on how ACP supports hope is scarce. We have taken up the challenge to specify ways in which ACP conversations may potentially support hope.

Methods

In an international qualitative study, we explored ACP experiences of patients with advanced cancer and their personal representatives (PRs) within the cluster‐randomised control ACTION trial. Using deductive analysis of data obtained in interviews following the ACP conversations, this substudy reports on a theme of hope. A latent thematic analysis was performed on segments of text relevant to answer the research question.

Results

Twenty patients with advanced cancer and 17 PRs from Italy, the Netherlands, Slovenia, and the United Kingdom were participating in post‐ACP interviews. Three themes reflecting elements that provide grounds for hope were constructed. ACP potentially supports hope by being (I) a meaningful activity that embraces uncertainties and difficulties; (II) an action towards an aware and empowered position; (III) an act of mutual care anchored in commitments.

Conclusion

Our findings on various potentially hope supporting elements of ACP conversations provide a constructive way of thinking about hope in relation to ACP that could inform practice.

Keywords: advance care planning, cancer, end of life, hope, international, qualitative research

1. INTRODUCTION

Advance care planning (ACP) enables patients to define goals and preferences for future medical treatment and care, to discuss these preferences with family and health‐care providers, and to record and review them if appropriate (Rietjens et al., 2017).

Hope in patients with a life‐threatening illness is defined by Johnson as being global in nature, moving from, or alongside, hope for longevity or cure, to hope embedded in relationships (Johnson, 2007). Johnson described 10 essential attributes of hope in terminally ill patients: Positive expectations, personal qualities, spirituality, goals, comfort, help, interpersonal relationships, control, and life review (Johnson, 2007). Various studies confirm that patients are usually hoping for comfort, quality of life, spirituality, and supportive relationships (Broadhurst & Harrington, 2016; Johnson, 2007; Kellehear, 2014; Kylma et al., 2009; Zwakman et al., 2020). Johnson's conceptualization of hope corresponds well to the concept of “reasonable hope” introduced by Weingarten (2010) or “reality‐based” hope that suggests relating to achievable aims in the face of life‐limiting illness (Duggleby & Wright, 2005). Reasonable hope is argued to be relational, consisting of a practice, maintaining that the future is open, uncertain, and influenceable, accepting doubt, contradictions, and despair (Weingarten, 2010). It is a moderate and sensible variant of hope suggesting actions and seems to be particularly suitable in the ACP context.

Hope is widely considered to be essential to well‐being and quality of life and even to life itself (Chochinov et al., 2002; Eliott & Olver, 2009). There is evidence of hope being sustained in palliative and dying patients (Broadhurst & Harrington, 2016; Nierop‐van Baalen et al., 2016; Penson et al., 2007; Sanatani et al., 2008). Worry of health care professionals that ACP may take away hope is one of the main recognised barriers in initiating ACP (Almack et al., 2012; De Vleminck et al., 2013; Jabbarian et al., 2018). ACP conversations include sensitive topics, such as asking patients about their preferences for care if they become unable to make their own decisions. Clinicians often perceive such questions as incompatible with promoting hope and maintaining normality in patients' remaining lifetime (Boyd et al., 2010). However, quantitative studies have indicated that engaging in ACP does not diminish hope or increase hopelessness (Cohen et al., 2020, 2021; Green et al., 2015) nor does ACP disrupt hope for a cure in most patients and their loved ones (Robinson, 2012). ACP may even enhance hope through provision of timely appropriate information (Davison & Simpson, 2006).

Findings from qualitative and concept analysis studies (Broadhurst & Harrington, 2016; Davison & Simpson, 2006; Eliott & Olver, 2009; Johnson, 2007; Nierop‐van Baalen et al., 2016; Penson et al., 2007) provide us with a sufficient understanding of the concept of hope and themes that foster hope in the context of palliative care, but we lack an understanding of potentially effective mechanisms of supporting hope in the context of ACP. The aim of this study was to explore how ACP conversations support different attributes of hope as conceptualised in the medical and nursing literature.

2. METHODS

As part of the cluster‐randomised controlled ACTION trial assessing the ACTION Respecting Choices (RC) ACP intervention in six European countries (Rietjens et al., 2016), we carried out a qualitative study in four of these countries (Italy, Netherlands, Slovenia, United Kingdom) to explore how patients and their personal representatives (PR) experienced taking part in the ACTION RC ACP intervention (the ACTION qualitative study).

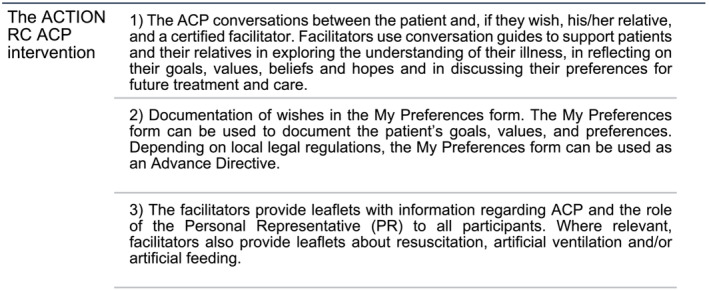

The ACTION RC ACP intervention is an adapted and integrated version of the RC® First Steps and Advanced Steps RC facilitated ACP conversation (more details can be found at www.respectingchoices.org). It consists of three main components, the ACP conversation being one of them (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

The ACTION RC ACP intervention, completed before the ACTION qualitative study

The ACTION qualitative study explored patient and family experience of receiving the ACTION RC ACP intervention and their perspectives on ACP (Pollock et al., 2022). This present paper reports on how taking part in the ACTION RC ACP intervention may support hope as one of the secondary objectives of the ACTION qualitative study.

2.1. Ethical approval

Ethical approval for the qualitative study was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee (REC) of the study coordinating centre and from the relevant local RECs. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

2.2. Sampling and recruitment

Patients with a diagnosis of lung cancer (stage III or IV) or colorectal cancer (stage IV or metachronous metastases) and, if involved, the person the patient nominated as their PR were invited to participate in the ACTION RC ACP intervention and in subsequent semistructured qualitative interviews. For details about the inclusion criteria, recruitment strategy, and the ACTION RC ACP intervention, we refer to the ACTION project article and the research protocol (Korfage et al., 2020; Rietjens et al., 2016). Data for the qualitative interviews were collected between January 2017 and July 2018.

2.3. Data collection and analysis

Semistructured qualitative interviews following the ACTION RC ACP intervention were chosen as being best suited to address the research question and are considered the primary dataset for the analysis. We used detailed narrative summaries of each patient case written in English and summaries of parts of the ACP conversations where patients explicitly reflected on their hopes as a part of the intervention. This allowed us to view each case holistically and to check whether recognised hope‐enhancing aspects were in some way related to patients' explicitly stated hopes.

Patients and their PRs were invited to take part in a semistructured qualitative interview approximately 2 weeks after ACP intervention. A follow‐up interview was requested 3 months later. Drawing on a topic guide developed collaboratively between researchers from the countries taking part in the ACTION qualitative study, participants were asked to tell about their current health circumstances, to discuss experiencing the ACP conversations, to reflect upon nominating and involving a person as their PR, and to consider outcomes of the ACP conversations. Experienced researchers from a range of academic and professional disciplines (sociology, nursing, psychology) carried out qualitative interviews. The ACP conversations and the interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

The concept of hope in the terminally ill is context‐specific and reflects how we think and practice. We did not ask participants directly about how ACP supports their hope or narrow our search on the word “hope” in the interviews, as hope can be less consistently understood across participants. We examined interview transcripts from the ACTION qualitative study using a deductive approach, utilising attributes of hope in terminally ill described by Johnson (2007) as our initial codes. We predetermined what to look for in the data, using a data extraction form (Supporting Information S2) based on Johnson's rich conceptualization (Johnson, 2007). This sensitised us to features of data indicating attributes of hope and provided context for analysis of the data (see Introduction for details on Johnson's essential attributes on hope). Johnson's concept analysis was recognised as a notable work in terms of explicating a wide range of aspects of hope from the perspective of the terminally ill and is in accordance with qualitative studies examining strategies to enhance hope (McClement & Chochinov, 2008).

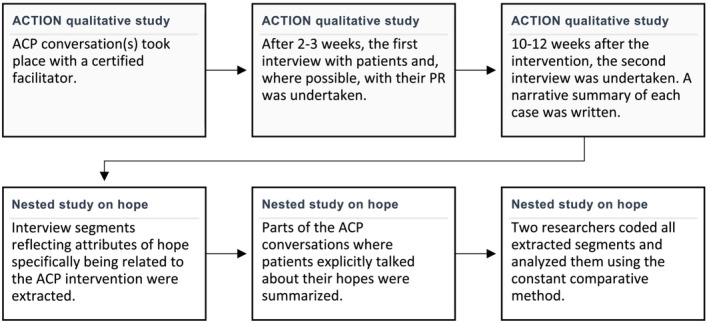

Our analytical approach (Figure 2) involved researchers from each participating country rereading the transcripts in their native language, before extracting and translating relevant interview segments. We did not have resources to translate all interviews into English.

FIGURE 2.

Flow‐chart of data collection and analysis procedure

Analysis was conducted largely in English to facilitate discussions between teams. English was the language of the ACTION study, and all researchers were fluent in written and spoken English. The codes were categorised into themes at a latent level (Braun et al., 2016; Braun & Clarke, 2006) by identifying coherent patterns in relation to hope supporting elements of ACP across sites and countries. The first two authors took the lead in analysis and interpretation of data. Analysis and data were discussed during regular meetings and email correspondence between researchers from all teams. Reflexivity was often employed, through each of us sharing our understandings of different conceptualizations of hope and implications for practice, which improved our conceptual thinking and the rigour of this study. To ensure the quality of our report, we followed a checklist COREQ (Tong et al., 2007) for reporting of qualitative studies.

3. RESULTS

Twenty patients, including 17 patients with their PR, participated in interviews following the intervention, four from Italy, five from Slovenia and the Netherlands, and six from the United Kingdom. Fourteen patients engaged in two interviews and six in a single interview. Sixteen patients had advanced lung cancer, and four had advanced colorectal cancer. Patients were aged from 50 to 88, with mean age 66. Eleven patients were men and nine were women. Twelve PRs were partners of patients and five were adult children (sample characteristics are provided in Table S1).

When asked directly about hope during the ACP conversation, participants expressed hope for longevity or even a possible cure. Other themes of hope mainly addressed close relationships, comfort, and quality of life.

When asked about the ACP conversations, participants referred to some attributes of hope in the palliative care setting as suggested by Johnson (2007), such as sense of control, inner strength and interpersonal relationships, as being enhanced or strengthened by the ACP conversation. Exploring relevant statements further, ACP is argued to be a hope‐enhancing strategy by virtue of themes presented in the following.

3.1. ACP as a meaningful activity that embraces uncertainties and difficulties

ACP provides tools to deal with difficult situations related to feared images of illness progression that may give people grounds for hope in the midst of sadness. Some participants claimed that the ACP conversation had a short‐term effect in a sense of raised distress. Excerpt 1:

At first, I was not happy about it [ACP conversation], quite the opposite; I had a moment where I thought to myself, “Damn, there are so many things to fight right now, and the sadness. We would be better off without this.” Well, it became clear with time, after a few days had passed and feelings have faded that this is good, you take the information you need and you move on. (Personal Representative 4, 1st Interview, Italy)

Excerpt 2:

PR: So yes, that's pretty hard of course, but you cannot avoid it. We both prefer to know that, also from each other, how we feel about it. Because it gives you control.

Patient: … Yes, clarity is the most important. Clarity about how you see things. (Patient and Personal Representative 4, 1st Interview, Netherlands)

The ACP experience often described by participants consisted of an immediate feeling of discomfort discussing end of life (EOL) followed by perceiving it as directly relevant and meaningful for their situation. We came to understand ACP as a meaningful activity that contributed to participants' sense of what existed at the moment, including current feelings, uncertainties and multiple perspectives, in order to prepare themselves for challenges that lay ahead of them.

An Italian patient who had a “profound fear of pain” described the ACP conversation influencing his fear and image of death by giving him some control over dying. At the same time, he maintained seeing his future as uncertain. Excerpt 3:

One never knows how it will end, everyone knows that more or less. But to be able to understand what could be my possibilities to carry on in dignity from here till … This helps. (Patient 1, 1st interview, Italy)

3.2. ACP as an action towards an aware and empowered position

The participants' accounts on beneficial aspects of the ACP conversation are characterised by a prevailing sense of empowerment. ACP conversation helped some participants to explore ways to cope with the scenario of health decline. Excerpt 4:

… to understand the disease better, what kind of behavior one should have, how to communicate with doctors in a clearer way, because if one knows a little more one can ask better questions. (Patient 1, 1st interview, Italy)

ACP conversation can assist people in a tangible way with the formulation of possibilities for the plan of care at the end of life. A participant from Slovenia stressed the importance of gaining constructive information from a professional perspective as part of the ACP. It is in this space that new thoughts and feelings can be expressed. Excerpt 5:

It was helpful. Of course. We can talk about it at home, but you get a professional perspective from a conversation like this. Before, you did not even think about certain things. Little details can open you up. You start to think in a different way, but not in a radical way. In a way that might be good, I could do that too. It helped a lot. (Patient 1, 1st interview, Slovenia)

ACP conversation can support one's identity as a determined, resilient and organised person. Participants from the UK described having a constructive mind‐set while engaging in the ACP conversation. Excerpt 6 and 7:

… it's like, not the pushing things away, is not it, it's out in the open, and let us talk about it and make us stronger as well, and prepared kind of, you know what I mean? So, we have had this conversation and it's preparing your mind set, really, so yeah, it was useful. (Personal Representative 1, 1st interview, UK)

It's given me the opportunity to think everything, prepare everything, sort of make sure everything is stable for everybody, then they do not have so much hassle in the future. / … /because, as I said, I'm well organized, always, so, I still want to be, leave things well organized. (P 1, 1st interview, UK)

3.3. ACP as an act of mutual care anchored in commitments

For some, ACP embodied mutual care. Caring for loved ones was the most consistently covered dimension in explicitly stated hopes by participants. An ACP conversation is something people do together. Excerpt 8:

… to give people who are in a state of vulnerability and dependency, the feeling of being accepted, heard, and for those around them to feel less lost … It is important because of the feeling that I share these issues with another human being and the fact that he participated [in ACP]. (Patient 2, 1st interview, Italy)

Most of the participant discussed the importance of ACP being a shared activity, helping them to establish or maintain awareness of one another's intentions, feelings and opinions on this matter. Excerpt 9:

In my opinion it works therapeutic, this [ACP] conversation … Otherwise you will not sit down for it together. I really find it helpful. / … /we liked it, as this was a welcome confirmation that we are aligned to each other [with PR]. (Patient 3, Interview 1st, Netherlands)

Facilitating such discussions, however challenging these may be, enabled some of them to relate to emotional aspects of the process, enhanced a sense of partnership, and shared responsibility in facing potential illness progression. Excerpt 10:

Do you think that your conversation with the facilitator in any way influenced the conversations you have with each other?

Patient: Yes, it freed them. I did not allow crying in my presence. I said [to my wife] if you want the best for me, do not cry. However, we did not talk. My son also told her not to cry. After the conversation, we started talking.

PR: It is a lot easier now that we talk openly. We are not hiding anything. It feels good to talk … I feel as if not all the responsibility and suffering is on my shoulders. (Patient and PR 1, 2nd interview, Slovenia).

4. DISCUSSION

Our ideas about hope are reflected in our behaviour. A question arises regarding how we think about ACP conversations that include sensitive topics, such as end of life care, in relation to hope. This paper argues that ACP may support hope as posed in the literature on hope in dying (Johnson, 2007). Considering how ACP is hope‐supporting has practical explanatory value, it might affect ACP practice. We acknowledge hope in patients with advanced illness as being multifaceted and achievable no matter how poor one's prognosis (Johnson, 2007). Especially valuable for circumstances that are believed to diminish hope is a concept of “reasonable hope” (Weingarten, 2010). Patients and their family members in our study harboured a range of hopes. Usually hope for living a “normal” life as long as possible prevailed. Other themes of (reasonable) hopes mainly addressed close relationships, comfort and quality of life. We used Johnson's conceptualization of hope (Johnson, 2007) to examine interview data from a new perspective. We did so to find a variety of hope‐supporting mechanisms within the experience of ACP we would otherwise have overlooked, such as enhancing control, personal qualities (namely courage) and strengthening relationships. Our results show that for some participants, ACP has the potential to enhance hope through promoting a proactive stance and helping to feel empowered to meet difficulties that lie ahead while embracing uncertainty. Hope in this sense is not about the positive outcome but refers to preparations and making sense of the current condition. Referring to Weingarten's concept of reasonable hope (Weingarten, 2010), our themes underpin the importance of directing our attention to what is within reach more than what is desirable but unattainable.

In ACP conversations caring interactions can occur, which are argued to be hope‐supporting, new thoughts and commitments can be expressed. It is something challenging that people do together in meeting the demands of possible illness progression. Relationships are recognised as paramount to hope (Johnson, 2007). Weingarten (Weingarten, 2010) argues that reasonable hope flourishes in relationship and refers to actions of one or many people, less to the attribute of an individual.

Health care professionals' efforts to understand how patients and family members respond to ACP is important; especially because their understanding guides their practice. For example, their perceptions of what is good for patients and a desire to protect them and themselves are directly connected to decisions about initiating discussions about EOL care or not (Keating et al., 2010; Prod'homme et al., 2018). This is especially relevant in cultures where ACP is not part of mainstream patient‐centered care and introducing ACP at earlier stages of illness is frequently avoided (Prince‐Paul & DiFranco, 2017).

While ACP might intensify somewhat unpleasant emotions linked to focusing on scenarios related to EOL (Johnson et al., 2016), participants felt the future is uncertain, but working, together, towards controlling some aspects of it felt valuable. Our findings support a relational approach to ACP (Briggs, 2004; Johnson et al., 2016). Participants valued ACP as a relational process that emphasises engagements between patient, PR and healthcare professional over time. ACP can provide an opportunity for patients and their significant others to explore subjective worlds and unknown territories together. Papadatou (2013) refers to “growth” in the context of palliative care as something that “occurs between people in the context of relations that become personal” and our findings show that ACP has a potential to support intimacy and honesty.

Though the facilitated ACP RC intervention was standardised, participants engaged individually with different expectations and objectives, for example, acquiring information about their illness, engaging a family member or making advanced treatment decisions. Understanding ACP as a means by which patients exercise control over choices at the EOL is too narrow, as studies have shown (Johnson et al., 2016; Michael et al., 2014). Our study provides further support that some fundamental and complex relational and emotional needs may be addressed in the process of ACP, which should be taken into account when discussing hope in relation to ACP. For many, agency is put in the service of caring for others; for example, to act on patient's behalf to secure desired outcomes or to spare a family member the difficulties related to decision‐making. Growing intimacy and open communication were reported by some participants as a result of the intervention that is important in the light of the notion that new targets of hope in patients with life‐threatening illness are likely embedded in their intimate relationships (6). There is evidence of the crucial significance of relational dimensions in patients' hoping in the context of palliative care (Benzein et al., 2001; Kylma et al., 2009; Olsman et al., 2016).

Our findings do not say much about the importance of documenting preferences about EoL care for its own sake—instead they indicate other hopes and values patients and their PRs hold. We argue that hope supporting elements of ACP are about enabling a collaborative space where agency for the case of illness progression is supported and intimate and sometimes difficult thoughts and emotions are contained. From this interpersonal realm, hope can be supported. Hope for a cure or longevity is usually held simultaneously with other hopes. Integrating our findings into clinicians' worldview can contribute to their readiness and confidence in offering discussion of ACP. Clinicians should expect and be prepared to tolerate an increase in negative affect while discussing EOL matters while keeping in mind that ACP conversations have hope supporting features. Our findings support clinicians to discuss different possibilities about future care with their patients, explore feelings and multiple perspectives while sustaining uncertainty about the future, giving particular attention to key relationships and shared responsibility.

4.1. Strengths and limitations

Our findings extend observations from previous studies on hope in the context of ACP and contribute international data to this literature. It is important to note that ACTION RC ACP conversations avoid the predominantly biomedical model of discussing end‐of‐life care preferences and are taking into account emotional and psychosocial aspects in such planning as well.

Building expertise in ACP was an intensive process involving careful and critical consideration of the ACTION ACP intervention elements with regard to social context and specifics, which led to deep understanding of the ACP process. Deep contextual knowledge was necessary before moving onto analysis across sites, enhancing rigour of our study. Exploring an evidence‐based ACP intervention in the intercultural context facilitates the application of our findings to other contexts and settings.

Bearing in mind that participants' understanding of hope in relation to ACP could be hard to grasp if asked directly, we decided to search cues in their spontaneous talks about the intervention. The primary study, done simultaneously by authors of this substudy, was not designed to study hope. Whereas using this conceptual framework on hope did alert us to a range of important aspects, it might also direct our attention away from some other potentially important aspects. We did not take into consideration potential variances in perception of hope in the different cultures within and between the countries included.

Our approach of coding parts of data explicitly on hope in ACP conversations and extracted data from interviews, allowed us to construct coherent themes that are relevant for participants' explicitly stated hopes, which is important for validity of our findings.

Hope is sometimes discussed as one side of a polarity: Hope‐hopelessness. Addressing hope‐hindering aspects of ACP would create further balance in the discussion. However, hope and hopelessness may be distinct constructs and both could not be covered adequately in this paper. We decided to focus on hope‐supporting themes as only possible using this method of analysis.

A note of caution is also necessary regarding translating data early in the process of analysis. Analysing translated segments meant risking losing some meaning inherent to the data. However, we worked collaboratively to ensure that data were not misinterpreted.

5. CONCLUSION

Despite the challenges of ACP processes for patients with advanced cancer and the difficulties and resistance participants sometimes feel in imagining the future, our study suggests that structured ACP conversation, addressing clinical, emotional, psychological and social aspects of patients' experience might support some hope‐enhancing attributes. By consenting to the concepts of “reasonable hope” and “hope in terminally ill” that suggest a modest and sensible variants of hope, a new way of thinking about hope in relation to ACP is possible. Grounded in authenticity and awareness of a difficult reality, promoting empowerment and connection, ACP conversations can provide grounds for hope.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Supporting Information S1. Sample Characteristics

Supporting Information S2. Supporting Information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This publication is based on the ACTION project that is funded by the 7th Framework Programme for Research and Technological Development (FP7) under grant agreement No 602541. We are grateful to all participating patients and relatives, facilitators, health care professionals and others who gave support and advice throughout the project.

Kodba‐Čeh, H. , Lunder, U. , Bulli, F. , Caswell, G. , van Delden, J. J. M. , Kars, M. C. , Korfage, I. J. , Miccinesi, G. , Rietjens, J. A. C. , Seymour, J. , Toccafondi, A. , Zwakman, M. , Pollock, K. , & ACTION Consortium (2022). How can advance care planning support hope in patients with advanced cancer and their families: A qualitative study as part of the international ACTION trial. European Journal of Cancer Care, 31(6), e13719. 10.1111/ecc.13719

Funding Information This work was supported by the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme FP7/2007‐2013 under grant agreement No 602541. The funding source had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Almack, K. , Cox, K. , Moghaddam, N. , Pollock, K. , & Seymour, J. (2012). After you: Conversations between patients and healthcare professionals in planning for end of life care. BMC Palliative Care, 11(1), 15. 10.1186/1472-684X-11-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benzein, E. , Norberg, A. , & Saveman, B. I. (2001). The meaning of the lived experience of hope in patients with cancer in palliative home care. Palliative Medicine, 15(2), 117–126. 10.1191/026921601675617254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, K. , Mason, B. , Kendall, M. , Barclay, S. , Chinn, D. , Thomas, K. , Sheikh, A. , & Murray, S. A. (2010). Advance care planning for cancer patients in primary care: A feasibility study. The British Journal of General Practice: The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 60(581), e449–e458. 10.3399/bjgp10X544032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V. , & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V. , Clarke, V. , & Weate, P. (2016). Using thematic analysis in sport and exercise research. 191‐205.

- Briggs, L. (2004). Shifting the focus of advance care planning: Using an in‐depth interview to build and strengthen relationships. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 7(2), 341–349. 10.1089/109662104773709503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadhurst, K. , & Harrington, A. (2016). A mixed method thematic review: The importance of hope to the dying patient. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 72(1), 18–32. 10.1111/jan.12765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chochinov, H. M. , Hack, T. , McClement, S. , Kristjanson, L. , & Harlos, M. (2002). Dignity in the terminally ill: A developing empirical model. Social Science & Medicine, 54(3), 433–443. 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00084-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, M. , Althouse, A. , Arnold, R. , Chu, E. , White, D. , & Schenker, Y. (2020). Does advance care planning actually reduce hope in advanced cancer? (TH322A). Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 59(2), 417–418. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.12.060 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, M. G. , Althouse, A. D. , Arnold, R. M. , Bulls, H. W. , White, D. , Chu, E. , Rosenzweig, M. , Smith, K. , & Schenker, Y. (2021). Is advance care planning associated with decreased hope in advanced cancer? JCO Oncol Pract, 17(2), e248–e256. 10.1200/op.20.00039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison, S. N. , & Simpson, C. (2006). Hope and advance care planning in patients with end stage renal disease: Qualitative interview study. BMJ, 333(7574), 886. 10.1136/bmj.38965.626250.55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vleminck, A. , Houttekier, D. , Pardon, K. , Deschepper, R. , Van Audenhove, C. , Vander Stichele, R. , & Deliens, L. (2013). Barriers and facilitators for general practitioners to engage in advance care planning: A systematic review. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care, 31(4), 215–226. 10.3109/02813432.2013.854590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duggleby, W. , & Wright, K. (2005). Transforming hope: How elderly palliative patients live with hope. The Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 37(2), 70–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliott, J. A. , & Olver, I. N. (2009). Hope, life, and death: A qualitative analysis of dying cancer patients' talk about hope. Death Studies, 33(7), 609–638. 10.1080/07481180903011982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green, M. J. , Schubart, J. R. , Whitehead, M. M. , Farace, E. , Lehman, E. , & Levi, B. H. (2015). Advance care planning does not adversely affect Hope or anxiety among patients with advanced cancer. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 49(6), 1088–1096. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.11.293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabbarian, L. J. , Zwakman, M. , van der Heide, A. , Kars, M. C. , Janssen, D. J. A. , van Delden, J. J. , Rietjens, J. A. C. , & Korfage, I. J. (2018). Advance care planning for patients with chronic respiratory diseases: A systematic review of preferences and practices. Thorax, 73(3), 222–230. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-209806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, S. (2007). Hope in terminal illness: An evolutionary concept analysis. International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 13(9), 451–459. 10.12968/ijpn.2007.13.9.27418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, S. , Butow, P. , Kerridge, I. , & Tattersall, M. (2016). Advance care planning for cancer patients: A systematic review of perceptions and experiences of patients, families, and healthcare providers. Psychooncology, 25(4), 362–386. 10.1002/pon.3926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keating, N. L. , Landrum, M. B. , Rogers, S. O. Jr. , Baum, S. K. , Virnig, B. A. , Huskamp, H. A. , Earle, C. C. , & Kahn, K. L. (2010). Physician factors associated with discussions about end‐of‐life care. Cancer, 116(4), 998–1006. 10.1002/cncr.24761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellehear, A. (2014). The inner life of the dying person. Columbia University Press. 10.7312/kell16784 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Korfage, I. J. , Carreras, G. , Arnfeldt Christensen, C. M. , Billekens, P. , Bramley, L. , Briggs, L. , Bulli, F. , Caswell, G. , Červ, B. , van Delden, J. J. M. , Deliens, L. , Dunleavy, L. , Eecloo, K. , Gorini, G. , Groenvold, M. , Hammes, B. , Ingravallo, F. , Jabbarian, L. J. , Kars, M. C. , … Rietjens, J. A. C. (2020). Advance care planning in patients with advanced cancer: A 6‐country, cluster‐randomised clinical trial. PLoS Medicine, 17(11), e1003422. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kylma, J. , Duggleby, W. , Cooper, D. , & Molander, G. (2009). Hope in palliative care: An integrative review. Palliative & Supportive Care, 7(3), 365–377. 10.1017/S1478951509990307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClement, S. E. , & Chochinov, H. M. (2008). Hope in advanced cancer patients. European Journal of Cancer, 44(8), 1169–1174. 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.02.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael, N. , O'Callaghan, C. , Baird, A. , Hiscock, N. , & Clayton, J. (2014). Cancer caregivers advocate a patient‐ and family‐centered approach to advance care planning. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 47(6), 1064–1077. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nierop‐van Baalen, C. , Grypdonck, M. , van Hecke, A. , & Verhaeghe, S. (2016). Hope dies last … A qualitative study into the meaning of hope for people with cancer in the palliative phase. European Journal of Cancer Care, 25(4), 570–579. 10.1111/ecc.12500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsman, E. , Willems, D. , & Leget, C. (2016). Solicitude: Balancing compassion and empowerment in a relational ethics of hope‐an empirical‐ethical study in palliative care. Medicine, Health Care, and Philosophy, 19(1), 11–20. 10.1007/s11019-015-9642-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadatou, D. (2013). The private worlds of professionals, teams and organizations in palliative care. In Cox G. R. & Stevenson R. G. (Eds.), Final acts: The end of life: Hospice and palliative care (pp. 25–44). Baywood Publishing Company, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Penson, R. T. , Gu, F. , Harris, S. , Thiel, M. M. , Lawton, N. , Fuller, A. F. Jr. , & Lynch, T. J. Jr. (2007). Hope. Oncologist, 12(9), 1105–1113. 10.1634/theoncologist.12-9-1105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock, K. , Bulli, F. , Caswell, G. , Kodba‐Čeh, H. , Lunder, U. , Miccinesi, G. , Seymour, J. , Toccafondi, A. , van Delden, J. J. M. , Zwakman, M. , Rietjens, J. , van der Heide, A. , & Kars, M. (2022). Patient and family caregiver perspectives of advance care planning: Qualitative findings from the ACTION cluster randomised controlled trial of an adapted respecting choices intervention. Mortality, 1‐21, 1–21. 10.1080/13576275.2022.2107424 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prince‐Paul, M. , & DiFranco, E. (2017). Upstreaming and normalizing advance care planning conversations‐a public health approach. Behav Sci (Basel), 7(2), 18. 10.3390/bs7020018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prod'homme, C. , Jacquemin, D. , Touzet, L. , Aubry, R. , Daneault, S. , & Knoops, L. (2018). Barriers to end‐of‐life discussions among hematologists: A qualitative study. Palliative Medicine, 32(5), 1021–1029. 10.1177/0269216318759862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rietjens, J. A. C. , Korfage, I. J. , Dunleavy, L. , Preston, N. J. , Jabbarian, L. J. , Christensen, C. A. , de Brito, M. , Bulli, F. , Caswell, G. , Červ, B. , van Delden, J. , Deliens, L. , Gorini, G. , Groenvold, M. , Houttekier, D. , Ingravallo, F. , Kars, M. C. , Lunder, U. , Miccinesi, G. , … van der Heide, A. (2016). Advance care planning—A multi‐centre cluster randomised clinical trial: The research protocol of the ACTION study. BMC Cancer, 16(1), 264. 10.1186/s12885-016-2298-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rietjens, J. A. C. , Sudore, R. L. , Connolly, M. , van Delden, J. J. , Drickamer, M. A. , Droger, M. , European Association for Palliative Care , van der Heide, A. , Heyland, D. K. , Houttekier, D. , Janssen, D. J. A. , Orsi, L. , Payne, S. , Seymour, J. , Jox, R. J. , & Korfage, I. J. (2017). Definition and recommendations for advance care planning: An international consensus supported by the European Association for Palliative Care. The Lancet Oncology, 18(9), e543–e551. 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30582-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, C. A. (2012). “Our best hope is a cure.” Hope in the context of advance care planning. Palliative & Supportive Care, 10(2), 75–82. 10.1017/S147895151100068X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanatani, M. , Schreier, G. , & Stitt, L. (2008). Level and direction of hope in cancer patients: An exploratory longitudinal study. Supportive Care in Cancer, 16(5), 493–499. 10.1007/s00520-007-0336-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong, A. , Sainsbury, P. , & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32‐item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weingarten, K. (2010). Reasonable hope: Construct, clinical applications, and supports. Family Process, 49(1), 5–25. 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2010.01305.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwakman, M. , van Delden, J. J. M. , Caswell, G. , Deliens, L. , Ingravallo, F. , Jabbarian, L. J. , Johnsen, A. T. , Korfage, I. J. , Mimić, A. , Arnfeldt, C. M. , Preston, N. J. , Kars, M. C. , & On behalf of the ACTION consortium . (2020). Content analysis of advance directives completed by patients with advanced cancer as part of an advance care planning intervention: Insights gained from the ACTION trial. Supportive Care in Cancer, 28(3), 1513–1522. 10.1007/s00520-019-04956-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information S1. Sample Characteristics

Supporting Information S2. Supporting Information

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.