Abstract

Efforts to control Onchocerca volvulus, the etiologic agent of river blindness, have been limited to vector control and drug treatment to eliminate microfilariae, with no means available to prevent infection. The goal of this study was to develop a vaccine against this infection using recombinant antigens that are expressed in the early larval stages of the parasite. Five recombinant antigens, Ov7, Ov64, OvB8, Ov9M, and Ov73k, were identified by screening adult and larval cDNA libraries with antibodies from immune humans, chimpanzees, or rabbits. When mice were immunized with the five individual recombinant antigens, statistically significant reductions in parasite survival were induced in mice immunized with Ov7, OvB8, or Ov64, when administered in alum but not when injected in Freund's complete adjuvant (FCA). Live larvae recovered from control and immunized mice were analyzed to determine their developmental stages. A decrease in the percentage of larvae molting from the third stage to the fourth stage was observed with mice immunized with Ov7, Ov64, or OvB8 in alum but not with mice immunized with Ov9 and Ov73k or with mice immunized with any of the five antigens in FCA. Mice immunized with a cocktail of the three protective antigens developed protective immunity equal to that seen with mice immunized with individual antigens. This study has identified, for the first time, three recombinant antigens capable of inducing protective immunity to O. volvulus. Furthermore, since the antigens functioned with alum as the adjuvant, this vaccine could potentially be used clinically to prevent river blindness in humans.

Onchocerca volvulus, the etiologic agent of river blindness, infects about 20 million people in Africa and South America and is a leading cause of infectious blindness globally (21). Infections with O. volvulus are initiated by the feeding of an infected blackfly on a human, during which time infective third-stage larvae (L3) are released onto the skin and subsequently develop into adult worms. Vector- and chemotherapy-based control methods are used in many regions of endemicity (21), but because of many factors including the development of drug resistance, the high cost of the programs, and inaccessibility of the 10 to 15 years of required treatment with ivermectin to much of the infected population, these control methods have limited applicability.

Human populations in which the infection is endemic have provided evidence that naturally acquired immunity against O. volvulus infection can occur. Within regions where onchocerciasis is endemic, 1 to 5% of the population who have been exposed to the infection display no signs or symptoms of the infection; these individuals are considered to be immune to the disease and have been termed putatively immune (PI) individuals (16, 20, 52). In addition, the number of microfilariae found in the skin of infected individuals tends to level off between 20 and 40 years of age, which suggests an acquired means of limiting infections (14). Efforts to understand the mechanism of protective immunity in humans have yielded conflicting results. Some studies have concluded that protective immunity in the PI individuals was correlated with diminished specific immunoglobulin E (IgE), IgG, and IgG subclass responses and an enhanced production of interleukin 2 (IL-2) and gamma interferon (IFN-γ) in response to adult worm antigens. This profile suggested that protective immunity was dependent on Th1 responses (32, 36, 42, 47, 48). In other studies, PI individuals produced IL-2, IL-5, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor in response to adult worm antigens and thus exhibited a mixed Th1 and Th2 response (10). Different results were obtained when cytokine responses to larval antigens were compared to responses to adult or microfilarial antigens. The PI individual response to larval antigens demonstrated a significant elevation of both IL-5 and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor in comparison to levels in infected individuals. Additionally, a subgroup of PI individuals also had a significantly elevated IFN-γ response to larval antigens. These findings suggested that the response of PI individuals to larval antigens was Th2 in the group as a whole, with a mixed Th1-Th2 response in a subgroup. In contrast, the response to adult and microfilarial antigens in the same PI population was limited to IL-5 (51). This finding further confounds the answer to the question of what type of immune response is associated with protective immunity in humans.

Protective immunity to larval O. volvulus has been demonstrated in two animal models, chimpanzees and mice. These animals were immunized with irradiated L3 because this form of immunization was proven effective elsewhere in several filarial host-parasite systems (3, 5, 41, 46, 54). One out of four chimpanzees immunized with irradiated O. volvulus L3 and then infected with untreated L3 demonstrated protective immunity based on the number of microfilariae found in the skin (44). A mouse model for the study of immunity to larval O. volvulus also demonstrated that immunization with irradiated larvae induced protective immunity, killing approximately 50 to 80% of challenge larvae. Diffusion chambers were used in the mouse model to contain the larvae and thus afford an efficient method for recovery of the parasites and for analysis of the micro environment in which the parasites were found. Cellular infiltrate into diffusion chambers implanted in immunized mice contained high numbers of eosinophils (33). Protective immunity in the mice to larval O. volvulus was dependent on IL-4 and IL-5 and not IFN-γ (28, 34). These findings clearly demonstrated that the protective immune response induced by irradiated larvae in mice was Th2 dependent.

The objective of the present study was to determine the efficacy of recombinant antigens as vaccine candidates against the larval stages of O. volvulus. Studies with other filarial worms have shown that recombinant antigens can be identified with antibodies from immune serum and that these antigens induced a protective immune response against larval parasites, killing approximately 50% of parasites in the challenge infections (26, 35, 49). The advantage of using defined recombinant antigens lies in the fact that they can be efficiently and reproducibly generated, whereas irradiated larvae or crude native antigen preparations cannot be practically generated and therefore lack clinical utility. Four recombinant antigens (Ov7, Ov64, OvB8, and Ov73k) were selected in the present study for vaccine efficacy testing based on their recognition by antibodies from PI individuals or immunized chimpanzees, and one (Ov9M) was selected based on recognition by antibodies from rabbits immunized with L3 and fourth-stage larvae (L4) (Table 1). Additional criteria for selection of these antigens were their expression in L3 and/or L4 and their high immunogenicity in PI or infected individuals from Liberia, Ecuador, and Cameroon. Ov7 was recognized by 65 to 90% of these individuals, Ov64 was recognized by 88 to 95%, OvB8 was recognized by 31 to 58%, Ov73k was recognized by 90 to 100%, and Ov9M was recognized by 59 to 80% (S. Lustigman, personal communication).

TABLE 1.

Recombinant antigens tested for efficacy in a vaccine against larval O. volvulus

| Clone name | cDNA library | Source of screening antibodies | Identity and/or homology | Protein size and stage-specific expression | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ov7 | Adult | Chimpanzee immunized with irradiated L3 | Onchocystatin, a cysteine protease inhibitor. Homologues in B. malayi (22) and A. viteae (24) | 17 kDa in all stages | 37, 38 |

| L3 and L4 cDNA | PI individual sera from Liberia and Ecuador | ||||

| Ov64 | L3 | PI individual sera from Liberia and Ecuador | Novel, homologues in A. viteae (43), B. malayi (22), and D. immitis (18, 19) | 15 kDa, L3 specific | 29 |

| OvB8 | L3 | PI individual sera from Liberia and Ecuador | Novel, partial cDNA clone with no sequence homology to any other known genes. Homologue in B. malayi based on an ESTa sequence in the B. malayi database | 66 kDa, in all stages | S. Lustigman, unpublished results |

| Ov73k | L4 | PI individual sera from Liberia and Ecuador | Novel, Gln-rich protein. Cross reactivity with a protein in Brugia pahangi | 80 kDa in female, and 53 kDa, in L3 and L4 | 30 |

| L3 | Pool of sera from infected individuals from Ecuador | ||||

| Ov9M | Adult | Rabbit immunized with L3 and L4 | Calponin, homologue in B. malayi based on an EST sequence in the B. malayi database | 45 kDa, in all stages | 25 |

EST, expressed sequence tag.

The five recombinant antigens were tested in the present study to determine their ability to induce in mice the killing of a challenge infection consisting of O. volvulus larvae implanted in a diffusion chamber. The antigens were injected into the mice using either Freund's complete adjuvant (FCA) or alum as the adjuvant. FCA was selected because it preferentially induces Th1 responses, whereas alum preferentially induces Th2 responses (17, 31, 55). It was determined that three of the five antigens induced protective immunity when injected in alum and that combining the three antigens into one vaccine cocktail did not enhance the level of protective immunity that was induced.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Expression of the recombinant proteins.

Ov64 cDNA and the OvB8 clones were expressed in the pGEX-4T-3 vector, Ov7 and Ov9M were expressed in the pGEX-1N vector, and Ov73k was expressed in the pGEX-1T vector (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, N.J.). Large-scale production and purification of each of the recombinant Schistosoma japonicum glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion polypeptides were carried out according to the procedure previously described (38). The recombinant proteins were dialyzed against phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and sterilized by passage through a 45-μm-pore-size filter. Ov7 was also expressed as a secreted polypeptide in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using the pAB125 plasmid vector, a gift from Chiron Corp., Emeryville, Calif. Following a preparation of the plasmid DNA in Escherichia coli, this construct was digested with BamHI and SalI, releasing a fragment containing the yeast expression vector pBS24.1 used to transform yeast spheroplasts, as previously described (9, 50). Transformed yeast cells were selected on a leucine-deficient medium plate. Colonies were picked up and subcultured in leucine-deficient minimal synthetic defined liquid medium (Clontech Laboratories, Inc., Palo Alto, Calif.) containing 8% glucose to prevent induction. The overnight culture was subsequently diluted into YEPD (1% Bacto Yeast Extract and 2% Bacto Peptone plus 1% glucose medium). The secreted Ov7 was purified from the yeast culture supernatant after centrifugation by ion-exchange chromatography (Q-Sepharose Fast Flow; Pharmacia). The culture supernatant was precipitated with 20% (wt/vol) polyethylene glycol 1000 and resuspended in 10 mM Tris, pH 8.0, before being loaded on the Q-Sepharose column. Bound protein was eluted with a linear gradient of 0 to 0.5 M NaCl in 10 mM Tris, pH 8.0. The fractions containing Ov7 were detected by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Western blotting using affinity-purified monospecific human antibodies directed against recombinant Ov7. The specific fractions were collected and dialyzed against 10 mM Tris, pH 8.0.

Electron microscopy.

O. volvulus L3 were placed in culture for 4 days, as previously described (39), to obtain larvae in the process of molting from L3 to L4. The larvae were fixed for 30 min in 0.25% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, containing 1% sucrose, and were then processed for immunoelectron microscopy. For the immunolocalization of the parasite antigens corresponding to the five recombinant antigens, thin sections of embedded worms were incubated with affinity-purified antibodies against each of the individual antigens, followed by incubation with a suspension of 15-nm gold particles coated with protein A, as described previously (25, 37, 40). In addition, thin sections of molting L3 were probed with normal mouse serum and serum obtained from mice immunized with irradiated L3 and which developed protective immunity to challenge infections (33). Sections were incubated with the immune mouse serum, followed by rabbit anti-mouse Ig before reaction with 15-nm gold particles coated with protein A.

Immunization protocols.

Male BALB/cByJ mice, 6 to 8 weeks old, were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine). Animals were housed in Micro-Isolator boxes (Lab Products, Inc., Maywood, N.J.) and were fed autoclavable laboratory rodent chow (Ralston Purina, St. Louis, Mo.) and sterilized acid water (pH 2.7) ad libitum. The animal housing room was temperature, humidity, and light cycle controlled.

In the initial screening of the antigens, 25 μg of each antigen in 0.1 ml of PBS was injected subcutaneously into the nape of the neck with either 0.1 ml of FCA (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) or 0.1 ml of low-viscosity alum, 2 mg/ml in PBS (Reheis Inc., Berkeley Heights, N.J.). A booster immunization followed 14 days later with the same quantity of antigen either in Freund's incomplete adjuvant for mice initially injected with FCA or in alum, as described above. In subsequent experiments, mice were immunized with 2, 25, or 50 μg of the antigens with alum, to determine the optimal dose. Finally, experiments were performed in which a mixture of three antigens was prepared, with 25 μg of each antigen, and the animals were immunized with 75 μg of the antigen mixture in alum, as described above, followed by a booster immunization with the same materials.

Challenge infections in diffusion chambers.

Cryopreserved L3 were prepared in Cameroon by the following method. Black flies (Simulium damnosum) were fed on consenting donors infected with O. volvulus, and after 7 days the developed L3 were collected from dissected flies, cleaned, and cryopreserved in dimethyl sulfoxide and sucrose using Biocool II computerized freezing equipment (FTS Systems Inc., Stone Ridge, N.Y.) as previously described (13). Cryopreserved L3 were thawed by placing tubes containing the L3 on dry ice for 15 min followed by immersion in a 37°C water bath. The L3 were then washed five times in a 1:1 mixture of Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium and NCTC-135 with 100 U of penicillin, 100 μg of streptomycin, 100 μg of gentamicin, and 30 μg of chloramphenicol (Sigma Chemical Co.) per ml.

Diffusion chambers were constructed from 14-mm-diameter Lucite rings and covered with 5.0-μm-pore-size hydrophilic Durapore membranes (Millipore, Bedford, Massa.) as previously described (7). Twenty-five O. volvulus L3 in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium–NCTC-135 with antibiotics were inserted into each diffusion chamber prior to implantation in mice. The animals were anesthetized with inhaled isoflurane, and a subcutaneous pocket was formed in the rear flank of each mouse. A single diffusion chamber containing 25 live O. volvulus L3 was inserted into each pocket.

Diffusion chambers were recovered 21 days postchallenge. At the time of diffusion chamber recovery, mice were anesthetized with methoxyflurane (Pitman-Moore, Inc., Mundelein, Ill.) and then killed by exsanguination. Serum was then prepared for subsequent antibody analyses. Diffusion chamber contents were analyzed to assess larval survival and the nature of the cellular infiltration into the diffusion chamber. Larvae recovered from diffusion chambers were considered live if they exhibited motility. Live larvae were placed into 70% ethanol containing 5% glycerol at 60°C. Ethanol was allowed to evaporate, leaving the larvae in glycerol. The larvae were then analyzed microscopically to differentiate L3 from L4. The following criteria were used: (i) the anterior end of the L4 is rounded whereas the anterior end of the L3 narrows; (ii) the genital primordium is visible only in the L4; (iii) the posterior end of the L4 exhibits a clearly visible anus, whereas that of the L3 does not; and (iv) the cuticle-body wall of the L4 is significantly thicker than that of the L3 (6). Cells found within the diffusion chambers were collected by centrifugation onto slides using a Cytospin 3 (Shandon Inc., Pittsburgh, Pa.) centrifuge and then stained for differential counts with DiffQuik (Baxter Healthcare Corp., Miami, Fla.).

ELISA.

Serum levels of antigen-specific IgG1, IgG2a, and IgE antibodies were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Fifty microliters of a solution containing 2 μg of recombinant antigen per ml in 50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.8) was placed in the wells of 96-well Maxisorp plates (Nalge Nunc International, Rochester, N.Y.) overnight. After washing, 200 μl of blocking buffer (0.17 M boric acid, 0.12 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.25% bovine serum albumin, 0.05% Tween 20, pH 8.5) (BBS) was added to each well. Individual sera were diluted in BBS, 1/200 for IgG1 and 1/3 for IgG2a and IgE, and then added to the wells, followed by biotinylated anti-mouse IgG1, IgG2a, or IgE (Pharmingen, San Diego, Calif.) diluted 1:250. Extravidin peroxidase diluted 1:1,000 (Sigma) was added to the wells followed by ABTS [2,2′-azinobis(3-ethylbenzthiazolinesulfonic acid); Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Gaithersburg, Md.]. Optical densities were read at 410 nm in a Dynatech MR500 ELISA reader (Dynatech Laboratories, Inc., Chantilly, Va.) after overnight incubation.

Statistical analyses.

Data were analyzed by multifactorial analysis of variance in Systat 5.2 (Systat, Inc., Evanston, Ill.). Probability values of less than 0.05 were considered significant. All experiments were performed a minimum of two times with five to six animals per group, except the measurements of dose response, which were done once. Data from representative experiments are presented in the tables and figures. Percent reduction was calculated as follows: % reduction = [(average worm survival in control mice − average worm survival in immunized mice)/average worm survival in control mice] × 100.

RESULTS

Comparative localization of the recombinant proteins in L3.

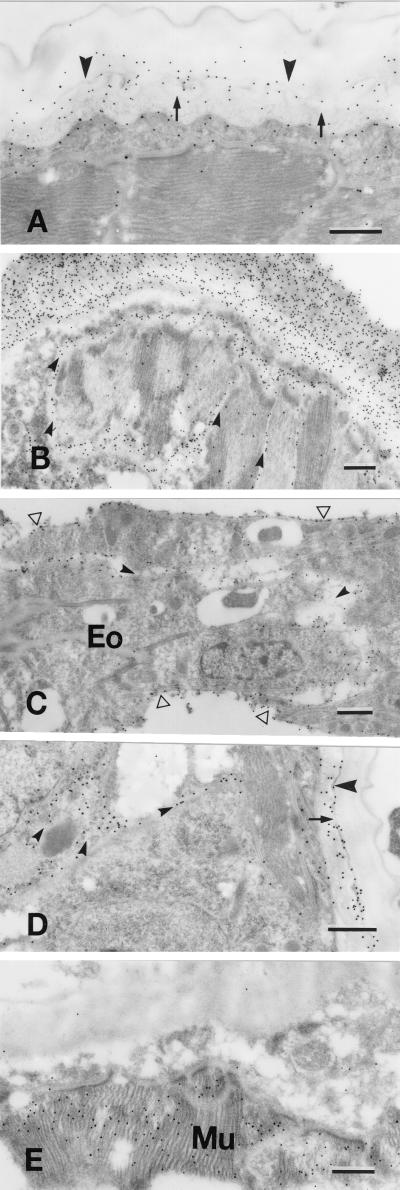

Antibodies from mice which developed protective immunity after immunization with irradiated L3 bound to parasite antigens in the region where the cuticle separates during molting from L3 to L4 (Fig. 1A), the channels connecting the esophagus to the cuticles (Fig. 1B), and the basal lamina surrounding the esophagus and the body cavity (Fig. 1C). Native parasite proteins corresponding to Ov7, Ov64, OvB8, and Ov73k recombinant proteins were found in regions compatible with those identified by the antibodies from the immunized mice (Fig. 2). Specifically, Ov7 (Fig. 2A) and Ov73k (Fig. 2D) were seen in the region of the cuticles where separation occurs and Ov64 (Fig. 2B) was seen in the cuticle. Ov7, Ov64, OvB8, and Ov73k (Fig. 2A to D) were found in the channels connecting the esophagus and the cuticles. Finally, OvB8 (Fig. 2D) was prominent at the basal lamina surrounding the esophagus and the body cavity in molting larvae, and antibodies against Ov9M reacted with the calponin protein in the muscles (Fig. 2E).

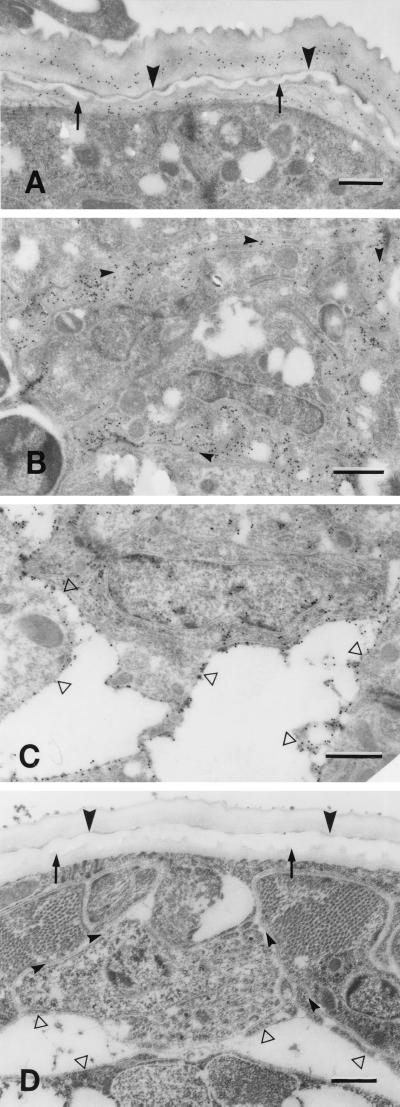

FIG. 1.

Ultrastructural localization by immunoelectron microscopy of parasite proteins recognized by antibodies from mice that developed protective immunity after immunization with irradiated L3. Thin sections of O. volvulus larvae during molting of L3 to L4 in vitro were incubated first with mouse antibodies and then with rabbit anti-mouse Ig antibodies followed by protein A coupled to 15-nm gold particles for indirect antigen localization (bars, 0.5 nm). Note the labeling in the regions where the cuticles of L3 (arrowheads) and L4 (arrows) separate (A), the channels (small arrowheads) connecting the esophagus to the cuticle (B), and the basal lamina (open arrowheads) surrounding the esophagus and the body cavity (C). Labeling was not observed in sections incubated in normal mouse serum (D).

FIG. 2.

Ultrastructural localization by immunoelectron microscopy of the parasite proteins corresponding to Ov7, Ov64, OvB8, Ov73k, and Ov9M recombinant proteins. Thin sections of O. volvulus larvae during molting of L3 to L4 in vitro were incubated first with antibodies raised against GST-Ov7 (A), GST-Ov64 (B), GST-OvB8 (C), GST-Ov73k (D), and GST-Ov9M (E) fusion polypeptides and then with protein A coupled to 15-nm gold particles for indirect antigen localization (bars, 0.5 nm). Note the labeling in the areas of the L4 epicuticle-cuticle (small arrows, panels A and D) and the basal layer of the L3 cuticle (arrowheads, panels A and D) where the separation between cuticles takes place, the cuticle of L3 day 1 (B), channels connecting the esophagus (Eo) and the cuticle (small arrowheads, panels A to D), the basal lamina (open arrowheads) surrounding the esophagus and the body cavity (C and D), and muscles (Mu) (E). Serum raised against GST did not ross-react with any proteins in the larvae (data not shown).

Immunization with individual recombinant antigens.

Mice immunized with either Ov7, Ov64, OvB8, Ov9M, or Ov73k received challenge infections consisting of O. volvulus L3 implanted subcutaneously in diffusion chambers. After 3 weeks, the number of live larvae recovered from each diffusion chamber was counted. Statistically significant reductions in parasite survival were induced by three of the antigens, Ov7, OvB8, and Ov64, when administered in alum. Immunization with Ov7, Ov9M, or Ov73k induced some reduction in parasite survival when injected with FCA; however, the reductions did not reach statistical significance compared to those for controls (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Effect of immunization with recombinant antigens injected with alum or with FCA

| Adjuvant and antigen | Recoverya

|

% L4b

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Immune | % Reduction | Control | Immune | |

| Alum | |||||

| Ov7 | 35 ± 10 | 23 ± 6 | 34c | 91 ± 8 | 63 ± 20d |

| Ov64 | 35 ± 10 | 21 ± 8 | 40c | 91 ± 9 | 74 ± 7d |

| OvB8 | 35 ± 10 | 19 ± 5 | 46c | 91 ± 9 | 74 ± 11d |

| Ov9M | 64 ± 19 | 65 ± 15 | 0 | 90 ± 6 | 95 ± 4 |

| Ov73k | 64 ± 19 | 56 ± 19 | 13 | 90 ± 6 | 86 ± 17 |

| FCA | |||||

| Ov7 | 47 ± 21 | 37 ± 11 | 21 | 98 ± 6 | 96 ± 10 |

| Ov64 | 47 ± 21 | 45 ± 11 | 4 | 98 ± 6 | 100 ± 00 |

| OvB8 | 47 ± 21 | 51 ± 25 | 0 | 98 ± 6 | 100 ± 0 |

| Ov9M | 47 ± 21 | 36 ± 15 | 23 | 98 ± 6 | 100 ± 0 |

| Ov73k | 47 ± 21 | 35 ± 5 | 26 | 98 ± 6 | 97 ± 8 |

Values represent percent live larvae recovered per diffusion chamber (means ± standard deviations).

Values represent percent live larvae recovered per diffusion chamber which molted into L4 (means ± standard deviations).

For recovery of live parasites from control mice compared with that from immunized mice, P < 0.05.

For percentages of live parasites from control mice that were L4 compared with those from immunized mice, P < 0.05.

Live larvae recovered from control and immunized mice were analyzed to determine whether they were L3 or if they had successfully molted into L4. A significant reduction was seen in the percentage of larvae that were recovered as L4 from mice immunized with Ov7, Ov64, or OvB8 (Table 2). The actual number of live L3 recovered from the control mice was compared to the number recovered from mice immunized with these three antigens. It was determined that both groups of mice maintained small, but equal, numbers of L3. The decrease in live parasites recovered from mice immunized with Ov7, Ov64, or OvB8 in alum was therefore a reflection of a decrease in the number of L4 and not L3 in immunized mice.

Analyses were performed to identify immune factors that could be correlated with the development of protective immunity. Diffusion chamber contents were analyzed to determine the cell types that migrated into the microenvironment of the larvae. No differences were observed in the types of cells or in the numbers of cells found in the diffusion chambers either between control and immunized mice or between mice immunized with antigens in FCA and mice immunized with antigens in alum. In all groups, the cells consisted of approximately 45% neutrophils, 40% monocytes, 10% lymphocytes, and 5% eosinophils.

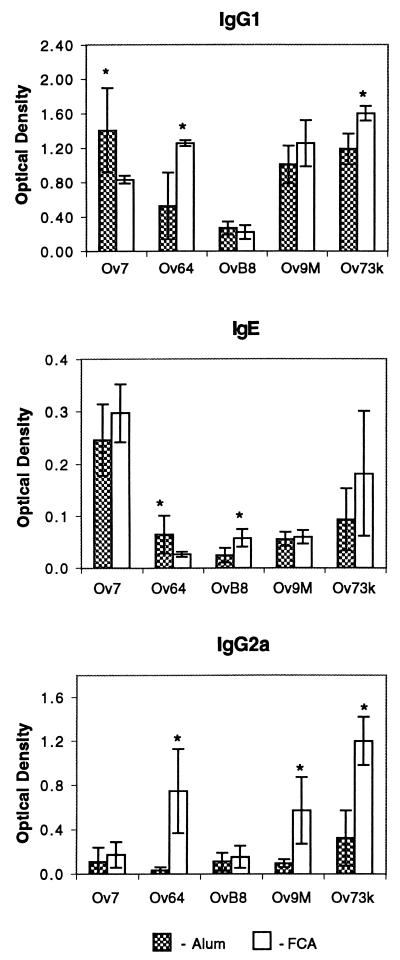

IgG1 and IgE antigen-specific antibody levels were measured to assess Th2 responses, and IgG2a antibody levels were measured to assess Th1 responses. In general, immunized mice responded to the five antigens at levels significantly higher than that seen with control mice for all three antibody classes or subclasses tested. Antigens administered with alum induced Th2-associated antibodies, whereas FCA did not consistently induce antibodies associated with the Th1 response. Differences in antibody responses were noted, however, based on the antigen used in the immunization. Ov7 induced elevated IgG1 and IgE levels regardless of the adjuvant used; IgG2a antibodies were undetectable even when FCA was used as the adjuvant. OvB8 induced weak antibody responses for all antibody isotypes tested with both adjuvants. Ov64, Ov9M, and Ov73k induced IgG1 antibody responses when alum and FCA were used as the adjuvants, and an IgG2a response when FCA was used (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

IgG1, IgE, and IgG2a antibody responses of mice immunized with Ov7, Ov64, OvB8, Ov9M, or Ov73k with either alum or FCA. The mean responses measured for control mice were subtracted from the responses measured for individual immunized mice. Values presented are the means and standard deviations of the measurements from the immunized mice after subtraction of the control values. Asterisks represent significant differences between responses seen for mice immunized with alum and those for mice immunized with FCA.

Immunization with a mixture of recombinant antigens.

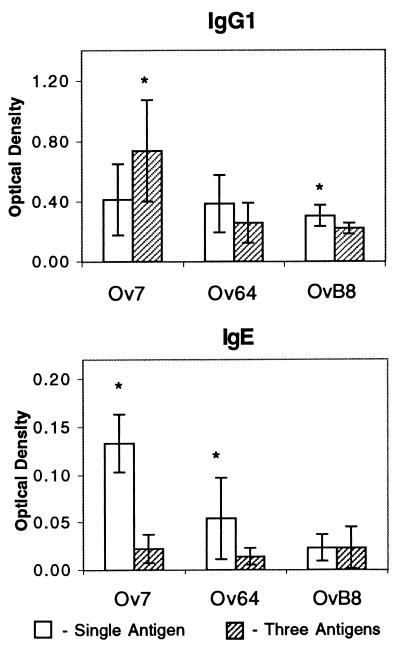

The goal of the next series of experiments was to determine the optimal regimen for immunizing mice with Ov7, Ov64, and OvB8 in alum. The first objective was to determine the optimal dose for immunization with the three antigens. Mice were immunized with the three individual antigens in alum at doses of 2, 25, and 50 μg and challenged as described above. All of the doses tested for the three antigens induced protective immunity at comparable rates. It was next hypothesized that immunization of mice with a mixture of the three protective antigens would lead to a protective immune response that would exceed that induced by any of the antigens individually. Mice were immunized either with individual antigens at 25 μg per dose or with a cocktail composed of equal concentrations of the three antigens, also at 25 μg of each antigen per dose. The dose of 25 μg was selected because it was as effective as 2 and 50 μg at inducing protective immunity and because this dose of the antigens was effective at inducing protective immunity in repeated experiments. Mice immunized with the cocktail of antigens developed protective immunity equal to, but not greater than, that in mice immunized with individual antigens (Table 3). IgG1 and IgE antigen-specific antibody levels were measured in mice immunized with individual antigens or with the cocktail of three antigens. IgG1 responses to Ov7 were significantly elevated in mice immunized with the antigen cocktail compared to responses in mice immunized with Ov7 alone. In contrast, IgG1 levels in response to OvB8 in mice immunized with the cocktail were significantly reduced compared to the levels seen with mice immunized with the single antigen. Significantly lower antigen-specific IgE responses to Ov7 and Ov64 were obtained in mice immunized with the antigen cocktail than in mice immunized with the individual antigens (Fig. 4).

TABLE 3.

Effect of immunization with single antigens or a cocktail of three recombinant antigens in alum on the survival of larvae in challenge infectionsa

| Antigen | Adjuvant | Recovery

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Immune | % Reduction | ||

| Ov7 | Alum | 49 ± 10 | 25 ± 12 | 49b |

| Ov64 | Alum | 49 ± 10 | 31 ± 17 | 37b |

| OvB8 | Alum | 49 ± 10 | 27 ± 17 | 45b |

| Ov7 + Ov64 + OvB8 | Alum | 49 ± 10 | 29 ± 10 | 41b |

Values represent percent live larvae recovered per diffusion chamber (means ± standard deviations).

For recovery of live parasites from control mice compared with that from immunized mice, P < 0.05.

FIG. 4.

IgG1 and IgE antibody responses of mice immunized with Ov7, Ov64, and OvB8, with alum injected individually or as a cocktail of three antigens. The mean responses measured for control mice were subtracted from the responses measured for individual immunized mice. Values presented are the means and standard deviations of the measurements from the immunized mice after subtraction of the control values. Asterisks represent significant differences between responses seen for mice immunized with single antigens and those for mice immunized with three antigens.

DISCUSSION

The objective of this study was to test the hypothesis that antigens identified by antibodies from humans or animals with protective immunity to O. volvulus would induce a protective immune response to the homologous parasite in mice. The five antigens used in this study were selected using a variety of criteria including the following: (i) the proteins were expressed in L3 and L4, (ii) they were identified by antibodies found in PI individuals or in immunized animals, (iii) they were recognized by a high percentage of PI and infected individuals from different geographic locations, and (iv) the anatomical locations of these proteins in the larvae were coincident with the binding sites of antibodies from mice with protective immunity to the parasite. Three of the five antigens in alum as the adjuvant induced a protective immune response as determined by the killing of 34 to 46% of challenge larvae in repeated experiments. This level of parasite reduction is comparable to the results obtained for mice immunized with irradiated O. volvulus larvae (33, 34). The present study has thus demonstrated that immunoscreening can identify antigens that function effectively in a vaccine. The three protective antigens were identified by antibodies from PI individuals or an immunized chimpanzee and yet functioned as successful immunogens in mice, a third host species. It was therefore concluded that antigen recognition and action were not host specific but rather that the antigens induced protective immunity regardless of the exposed host species.

It was further concluded that the protective immune response induced by the three recombinant antigens was directed at larvae molting from L3 to L4 or at L4 and was not effective at killing L3. The basis for this conclusion was that there was no decrease in the number of surviving L3 in immunized mice, whereas there was a significant decrease in the number of L4. Evidence from Acanthocheilonema viteae (8, 15), Dirofilaria immitis (4), and Strongyloides stercoralis (11, 12) supports the hypothesis that larval nematodes need to develop in vivo before they become susceptible to immune-mediated killing. Larvae may become more susceptible to the killing process during or after the molt from L3 to L4 or after the larvae have adapted to survival under mammalian host conditions. Based on this conclusion, the level of larval killing in immunized mice would actually be higher than that reported in this study, since all of the remaining L3 would be killed when they molted into L4. Evidence from immunization trials against D. immitis in dogs has shown that the protective immune response killed approximately 50% of challenge larvae at 3 weeks postchallenge but killed 98% at 6 months postchallenge (23). It is therefore probable that the level of protective immunity induced by the recombinant antigens in the present study would be augmented if the challenge infection larvae were recovered at a later time point.

The three protective antigens functioned only when injected with alum and not when injected with FCA, suggesting that the immune-mediated resistance was of the Th2 type and not Th1. This conclusion was based on previous reports which showed that FCA preferentially induced Th1 responses, while alum induced Th2 responses (17, 31, 55). The finding that protective immunity induced by recombinant antigens was dependent on a Th2 response complements the results obtained with irradicated L3 immunization. Immunity to O. volvulus larvae induced by irradiated larvae was dependent on IL-4 and IL-5 (28, 34) and was associated with the presence of eosinophils (34), thus demonstrating a dependence on Th2 immunity. Analyses of the antibody isotype responses and of the composition of the cellular infiltrates failed to confirm that the use of FCA and alum did induce Th1 and Th2 responses, respectively. Alum consistently induced Th2-dependent antibodies, but there was an absence of an increase in eosinophils in the diffusion chambers recovered from immunized mice. Use of FCA as the adjuvant induced only Th1 antibodies with three of the tested antigens. An explanation for the failure to see clear Th1 or Th2 responses induced by the antigens injected with FCA or alum may be that the three protective antigens each had unique capabilities of inducing immunity that were modified to varying degrees by the adjuvants. Immunization of mice against Trichinella spiralis using four different adjuvants, including FCA and alum, revealed that the adjuvants did not modify the immune response qualitatively but did affect the magnitude of the response (45). Each of the three protective antigens identified in the present study had its own inherent immune predisposition. Ov7 induced Th2 responses regardless of the adjuvant, OvB8 induced very weak antibody responses regardless of the adjuvant, and Ov64 induced Th2 responses in the presence of alum and Th1 responses in the presence of FCA. Yet, all three antigens induced protective immunity only when injected with alum.

No conclusion could be drawn from this study regarding the mechanism that the adaptive immune response uses to kill the larvae after immunization with the recombinant antigens. It must be emphasized, however, that each of the protective antigens is biochemically unique and that they are found in different anatomical locations. The killing mechanism induced by each of the antigens may, therefore, be different and specific for each particular target. Evidence from in vitro studies suggests that killing of O. volvulus larvae and prevention of molting of L3 to L4 are mediated by antibody from PI individuals in collaboration with neutrophils (27). Furthermore, monospecific affinity-purified human anti-Ov7 antibody, in the presence of neutrophils, caused a 100% inhibition of molting from L3 to L4 (S. Lustigman, personal communication). Filarial larval growth or developmental retardation in immunized animals has been reported previously for the larvae of A. viteae (8), Brugia malayi (3), D. immitis (1, 2), and Litomosoides carinii (53). A similar mechanism may be operative in vivo in mice immunized with recombinant antigens in the present study.

Combining the three protective antigens in one immunization dose did not induce levels of parasite killing that were greater than that for any of the single-antigen immunizations. The antigens in the present study may not have acted synergistically because one was either immunodominant or immunosuppressive. This hypothesis was supported by the observed alteration in the antibody responses to the three antigens dependent on whether they were injected individually or in a cocktail. This observation suggested that the combination of the three antigens did not allow a complete immune response to develop to any one of them. An alternative explanation for this finding is that the adaptive immune response is capable of killing only a fixed percentage of challenge larvae. The theoretical basis for this hypothesis is that there is stage specificity in the protective immune response. Larvae can be killed only during a limited period of their development, after which the larvae become resistant to attack by the immune response. The fixed number of larvae killed in the immunized mice might reflect the percentage of parasites incapable of developing into an immunologically resistant stage.

In conclusion, this study has demonstrated for the first time that cross-species identification of antigens by immunoscreening is a successful method for the selection of vaccine candidates against O. volvulus. Furthermore, it has shown that the method of delivery of the antigens is critical in determining the efficacy of a particular antigen in a vaccine. Three antigens that, with alum, induced reproducible levels of protective immunity have been identified. Further study is required to determine the optimal delivery method for each of these antigens, as well as the mechanism that each of these antigens induces for the killing of the larval parasites. Finally, the facts that the antigens functioned with alum as the adjuvant and that the three antigens are not homologous with any known human antigens, suggest that this vaccine could be used clinically to prevent river blindness in humans.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by grants from the Edna McConnell Clark Foundation and the National Institutes of Health (AI42328).

We acknowledge the enthusiastic and essential assistance of Anna Marie Galioto, De'Broski Herbert, Laura Kerepesi, and Chun-Chi Wang at Thomas Jefferson University; Jing Liu at the New York Blood Center for the production of the recombinant Ov7 protein in yeast; and the excellent technical assistance of Christine Christian and Margaret Brown in J. McKerrow's laboratory.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abraham D, Grieve R B. Genetic control of murine immune responses to larval Dirofilaria immitis. J Parasitol. 1990;76:523–528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abraham D, Grieve R B. Passive transfer of protective immunity to larval Dirofilaria immitis from dogs to BALB/c mice. J Parasitol. 1991;77:254–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abraham D, Grieve R B, Holy J M, Christensen B M. Immunity to larval Brugia malayi in BALB/c mice: protective immunity and inhibition of larval development. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1989;40:598–604. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1989.40.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abraham D, Grieve R B, Mika-Grieve M. Dirofilaria immitis: surface properties of third- and fourth-stage larvae. Exp Parasitol. 1988;65:157–167. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(88)90119-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abraham D, Grieve R B, Mika-Grieve M, Seibert B P. Active and passive immunization of mice against larval Dirofilaria immitis. J Parasitol. 1988;74:275–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abraham D, Lange A M, Yutanawiboonchai W, Trpis M, Dickerson J W, Swenson B, Eberhard ML. Survival and development of larval Onchocerca volvulus in diffusion chambers implanted in primate and rodent hosts. J Parasitol. 1993;79:571–582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abraham D, Rotman H L, Haberstroh H F, Yutanawiboonchai W, Brigandi R A, Leon O, Nolan T J, Schad G A. Strongyloides stercoralis: protective immunity to third-stage larvae in BALB/cByJ mice. Exp Parasitol. 1995;80:297–307. doi: 10.1006/expr.1995.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abraham D, Weiner D J, Farrell J P. Protective immune responses of the jird to larval Dipetalonema viteae. Immunology. 1986;57:165–169. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barr P J, Gibson H L, Enea V, Arnot D E, Hollingdale M R, Nussenzweig V. Expression in yeast of a Plasmodium vivax antigen of potential use in a human malaria vaccine. J Exp Med. 1987;165:1160–1171. doi: 10.1084/jem.165.4.1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brattig N, Nietz C, Hounkpatin S, Lucius R, Seeber F, Pichlmeier U, Pogonka T. Differences in cytokine responses to Onchocerca volvulus extract and recombinant Ov33 and OvL3–1 proteins in exposed subjects with various parasitologic and clinical states. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:838–842. doi: 10.1086/517317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brigandi R A, Rotman H L, Leon O, Nolan T J, Schad G A, Abraham D. Strongyloides stercoralis host-adapted third-stage larvae are the target of eosinophil-associated immune-mediated killing in mice. J Parasitol. 1998;84:440–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brigandi R A, Rotman H L, Nolan T J, Schad G A, Abraham D. Chronicity in Strongyloides stercoralis infections: dichotomy of the protective immune response to infective and autoinfective larvae in a mouse model. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;56:640–646. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1997.56.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cupp E W, Bernardo M J, Kiszewski A E, Trpis M, Taylor H R. Large scale production of the vertebrate infective stage (L3) of Onchocerca volvulus (Filarioidea: Onchocercidae) Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1988;38:596–600. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1988.38.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duke B O, Moore P J. The contributions of different age groups to the transmission of onchocerciasis in a Cameroon forest village. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1968;62:22–28. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(68)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eisenbeiss W F, Apfel H, Meyer T F. Protective immunity linked with a distinct developmental stage of a filarial parasite. J Immunol. 1994;152:735–742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elson L H, Guderian R H, Araujo E, Bradley J E, Days A, Nutman T B. Immunity to onchocerciasis: identification of a putatively immune population in a hyperendemic area of Ecuador. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:588–594. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.3.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forsthuber T, Yip H C, Lehmann P V. Induction of TH1 and TH2 immunity in neonatal mice. Science. 1996;271:1728–1730. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5256.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frank G R, Grieve R B. Purification and characterization of three larval excretory-secretory proteins of Dirofilaria immitis. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1996;75:221–229. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(95)02533-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frank G R, Tripp C A, Grieve R B. Molecular cloning of a developmentally regulated protein isolated from excretory-secretory products of larval Dirofilaria immitis. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1996;75:231–240. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(95)02534-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gallin M, Edmonds K, Ellner J J, Erttmann K D, White A T, Newland H S, Taylor H R, Greene B M. Cell-mediated immune responses in human infection with Onchocerca volvulus. J Immunol. 1988;140:1999–2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greene B M. Modern medicine versus an ancient scourge: progress toward control of onchocerciasis. J Infect Dis. 1992;166:15–21. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gregory W F, Blaxter M L, Maizels R M. Differentially expressed, abundant trans-spliced cDNAs from larval Brugia malayi. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1997;87:85–95. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(97)00050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grieve R B, Abraham D, Mika-Grieve M, Seibert B P. Induction of protective immunity in dogs to infection with Dirofilaria immitis using chemically-abbreviated infections. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1988;39:373–379. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1988.39.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hartmann S, Kyewski B, Sonnenburg B, Lucius R. A filarial cysteine protease inhibitor down-regulates T cell proliferation and enhances interleukin-10 production. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:2253–2260. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Irvine M, Huima T, Prince A M, Lustigman S. Identification and characterization of an Onchocerca volvulus cDNA clone encoding a highly immunogenic calponin-like protein. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1994;65:135–146. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(94)90122-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jenkins R E, Taylor M J, Gilvary N, Bianco A E. Characterization of a secreted antigen of Onchocerca volvulus with host-protective potential. Parasite Immunol. 1996;18:29–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.1996.d01-10.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson E H, Irvine M, Kass P H, Browne J, Abdullai M, Prince A M, Lustigman S. Onchocerca volvulus: in vitro cytotoxic effects of human neutrophils and serum on third-stage larvae. Trop Med Parasitol. 1994;45:331–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson E H, Schynder-Candrian S, Rajan T V, Nelson F K, Lustigman S, Abraham D. Immune responses to third stage larvae of Onchocerca volvulus in interferon-gamma and interleukin-4 knockout mice. Parasite Immunol. 1998;20:319–324. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.1998.00148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joseph G T, Huima T, Lustigman S. Characterization of an Onchocerca volvulus L3-specific larval antigen, Ov-ALT-1. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1998;96:177–183. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(98)00094-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Joseph G T, McCarthy J S, Huima T, Mair K F, Kass P H, Boussinesq M, Goodrick L, Bradley J E, Lustigman S. Onchocera volvulus: characterization of a highly immunogenic Gln-rich protein. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1997;90:55–68. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(97)00132-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kenney J S, Hughes B W, Masada M P, Allison A C. Influence of adjuvants on the quantity, affinity, isotype and epitope specificity of murine antibodies. J Immunol Methods. 1989;121:157–166. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(89)90156-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.King C L, Nutman T B. Regulation of the immune response in lymphatic filariasis and onchocerciasis. Immunol Today. 1991;12:A54–A58. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5699(05)80016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lange A M, Yutanawiboonchai W, Lok J B, Trpis M, Abraham D. Induction of protective immunity against larval Onchocerca volvulus in a mouse model. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1993;49:783–788. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1993.49.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lange A M, Yutanawiboonchai W, Scott P, Abraham D. IL-4- and IL-5-dependent protective immunity to Onchocerca volvulus infective larvae in BALB/cBYJ mice. J Immunol. 1994;153:205–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li B W, Chandrashekar R, Weil G J. Vaccination with recombinant filarial paramyosin induces partial immunity to Brugia malayi infection in jirds. J Immunol. 1993;150:1881–1885. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luder C G, Schulz-Key H, Banla M, Pritze S, Soboslay P T. Immunoregulation in onchocerciasis: predominance of Th1-type responsiveness to low molecular weight antigens of Onchocerca volvulus in exposed individuals without microfilaridermia and clinical disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 1996;105:245–253. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.d01-747.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lustigman S, Brotman B, Huima T, Prince A M. Characterization of an Onchocerca volvulus cDNA clone encoding a genus specific antigen present in infective larvae and adult worms. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1991;45:65–75. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(91)90028-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lustigman S, Brotman B, Huima T, Prince A M, McKerrow J H. Molecular cloning and characterization of onchocystatin, a cysteine proteinase inhibitor of Onchocerca volvulus. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:17339–17346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lustigman S, Huima T, Brotman B, Miller K, Prince A M. Onchocerca volvulus: biochemical and morphological characteristics of the surface of third- and fourth-stage larvae. Exp Parasitol. 1990;71:489–495. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(90)90075-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lustigman S, McKerrow J H, Shah K, Lui J, Huima T, Hough M, Brotman B. Cloning of a cysteine protease required for the molting of Onchocerca volvulus third stage larvae. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:30181–30189. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.47.30181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oothuman P, Denham D A, McGreevy P B, Nelson G S, Rogers R. Successful vaccination of cats against Brugia pahangi with larvae attenuated by irradiation with 10 krad cobalt 60. Parasite Immunol. 1979;1:209–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1979.tb00707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ottesen E A. Immune responsiveness and the pathogenesis of human onchocerciasis. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:659–671. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.3.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pogonka T, Oberlander U, Marti T, Lucius R. Acanthocheilonema viteae: characterization of a molt-associated excretory/secretory 18-kDa protein. Exp Parasitol. 1999;93:73–81. doi: 10.1006/expr.1999.4445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prince A M, Brotman B, Johnson E H, Jr, Smith A, Pascual D, Lustigman S. Onchocerca volvulus: immunization of chimpanzees with X-irradiated third-stage (L3) larvae. Exp Parasitol. 1992;74:239–250. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(92)90147-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Robinson K, Bellaby T, Wakelin D. Vaccination against the nematode Trichinella spiralis in high- and low-responder mice. Effects of different adjuvants upon protective immunity and immune responsiveness. Immunology. 1994;82:261–267. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schrempf-Eppstein B, Kern A, Textor G, Lucius R. Acanthocheilonema viteae: vaccination with irradiated L3 induces resistance in three species of rodents (Meriones unguiculatus, Mastomys coucha, Mesocricetus auratus) Trop Med Int Health. 1997;2:104–110. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1997.d01-129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Soboslay P T, Geiger S M, Weiss N, Banla M, Luder C G, Dreweck C M, Batchassi E, Boatin B A, Stadler A, Schulz-Key H. The diverse expression of immunity in humans at distinct states of Onchocerca volvulus infection. Immunology. 1997;90:592–599. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00210.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Steel C, Nutman T B. Regulation of IL-5 in onchocerciasis. A critical role for IL-2. J Immunol. 1993;150:5511–5518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Taylor M J, Abdel-Wahab N, Wu Y, Jenkins R E, Bianco A E. Onchocerca volvulus larval antigen, OvB20, induces partial protection in a rodent model of onchocerciasis. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4417–4422. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.11.4417-4422.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tume C B, Ngu J L, McKerrow J L, Seigel J, Sun E, Barr P J, Bathurst I, Morgan G, Nkenfou C, Asonganyi T, Lando G. Characterization of a recombinant Onchocerca volvulus antigen (Ov33) produced in yeast. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;57:626–633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Turaga P S D, Tierney T J, Bennett K E, McCarthy M C, Simonek S C, Enyong P A, Moukatte D W, Lustigman S. Immunity to onchocerciasis: cells from putatively immune individuals produce enhanced levels of interleukin-5, gamma interferon, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor in response to Onchocerca volvulus larval and male worm antigens. Infect Immun. 2000;68:1905–1911. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.4.1905-1911.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ward D J, Nutman T B, Zea-Flores G, Portocarrero C, Lujan A, Ottesen E A. Onchocerciasis and immunity in humans: enhanced T cell responsiveness to parasite antigen in putatively immune individuals. J Infect Dis. 1988;157:536–543. doi: 10.1093/infdis/157.3.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Weiner D J, Abraham D, D'Antonio R. Litomosoides carinii in jirds (Meriones unguiculatus): ability to retard development of challenge larvae can be transferred with cells and serum. J Helminthol. 1984;58:129–137. doi: 10.1017/s0022149x00028637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wong M M, Guest M F, Lavoipierre M J. Dirofilaria immitis: fate and immunogenicity of irradiated infective stage larvae in beagles. Exp Parasitol. 1974;35:465–474. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(74)90052-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yip H C, Karulin A Y, Tary-Lehmann M, Hesse M D, Radeke H, Heeger P S, Trezza R P, Heinzel F P, Forsthuber T, Lehmann P V. Adjuvant-guided type-1 and type-2 immunity: infectious/noninfectious dichotomy defines the class of response. J Immunol. 1999;162:3942–3949. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]