Abstract

Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae is an important cause of localized respiratory tract disease, which begins with colonization of the upper respiratory mucosa. In previous work we reported that the nontypeable H. influenzae HMW1 and HMW2 proteins are high-molecular-weight nonpilus adhesins responsible for attachment to human epithelial cells, an essential step in the process of colonization. Interestingly, although HMW1 and HMW2 share significant sequence similarity, they display distinct cellular binding specificities. In order to map the HMW1 and HMW2 binding domains, we generated a series of complementary HMW1-HMW2 chimeric proteins and examined the ability of these proteins to promote in vitro adherence by Escherichia coli DH5α. Using this approach, we localized the HMW1 and HMW2 binding domains to an ∼360-amino-acid region near the N terminus of the mature HMW1 and HMW2 proteins. Experiments with maltose-binding protein fusion proteins containing segments of either HMW1 or HMW2 confirmed these results and suggested that the fully functional binding domains may be conformational structures that require relatively long stretches of sequence. Of note, the HMW1 and HMW2 binding domains correspond to areas of maximal sequence dissimilarity, suggesting that selective advantage associated with broader adhesive potential has been a major driving force during H. influenzae evolution. These findings should facilitate efforts to develop a subcomponent vaccine effective against nontypeable H. influenzae disease.

Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae is a major cause of localized respiratory tract disease, including otitis media, sinusitis, conjunctivitis, bronchitis, and pneumonia (33). The initial step in the pathogenesis of disease involves colonization of the nasopharynx (19). Colonization with a particular strain may persist for weeks to months, usually without producing symptoms (25, 32). However, in the setting of viral respiratory infection or allergic disease, the organism will often spread contiguously to the middle ear, the sinuses, the conjunctiva, or the lungs. Successful colonization requires that the organism overcome the mucociliary escalator, and adherence to respiratory epithelium plays a fundamental role in achieving this goal.

Among diverse strains of nontypeable H. influenzae, both pilus and nonpilus adhesins have been defined. Approximately 75% of clinical isolates produce proteins that are immunologically and functionally related to the HMW1 and HMW2 adhesins produced by H. influenzae strain 12 (3). HMW1 and HMW2 are nonpilus proteins that were originally identified as the predominant targets of the host immune response during acute otitis media (2). Adherence assays with strain 12 mutants deficient in expression of HMW1 or HMW2 or both suggested that these proteins have adhesive properties, and examination of Escherichia coli transformants expressing either HMW1 or HMW2 confirmed this conclusion (30).

Overall, HMW1 and HMW2 share 71% identity and 80% similarity (3). Interestingly, despite their sequence similarity, these proteins exhibit different cellular binding specifities (10, 29, 30). For example, HMW1 promotes high-level binding to Chang conjunctival cells and HaCaT keratinocytes, while HMW2 promotes low-level or undetectable binding to Chang cells but high-level binding to HaCaT cells. This observation suggests that the two proteins may recognize different receptors on the host cell surface and thus may contain different binding domains. Recent experiments demonstrated that HMW1-mediated binding to Chang cells involves interaction with a glycoprotein receptor containing α2,3-linked sialic acid (27). This binding is inhibited by the lectin Maackia amurensis agglutinin (MAA), which specifically recognizes sialic acid in an α2,3 configuration. Information regarding the host cell receptor with which HMW2 interacts is presently lacking.

HMW1 and HMW2 are encoded by separate chromosomal loci, hmw1 and hmw2, respectively, each consisting of three genes, including hmwA, which codes for the structural protein (HMW1 or HMW2), followed by hmwB and hmwC (4). The hmw1B and hmw2B genes encode the HMW1B and HMW2B proteins, which are 99% identical, while the hmw1C and hmw2C genes encode the HMW1C and HMW2C proteins, which share 97% identity. In order to facilitate interaction with host cells, HMW1 and HMW2 are localized on the surface of the organism in a process that involves cleavage of a 441-amino-acid N-terminal fragment (3). In recent work, we demonstrated that the HMWB and HMWC proteins are required for normal processing and secretion of the structural proteins and established that HMW1B-HMW1C and HMW2B-HMW2C are functionally interchangeable (29).

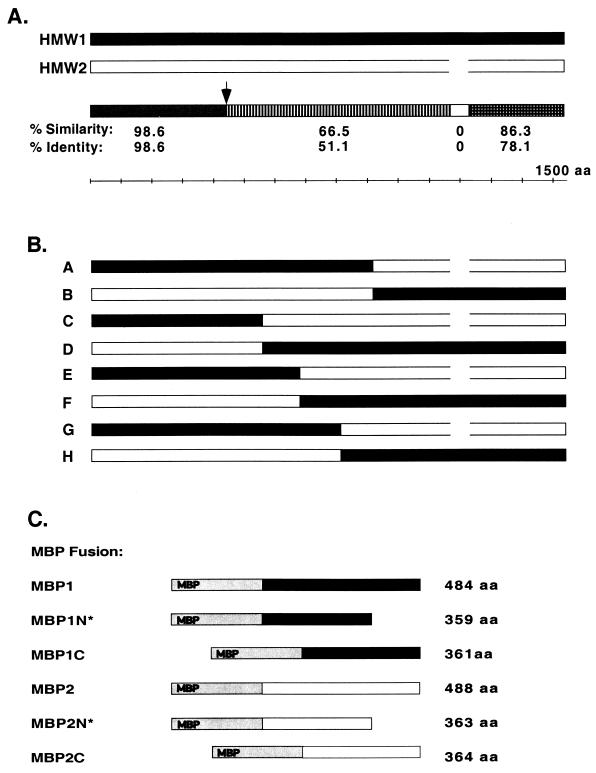

The HMW1 preprotein contains 1,536 amino acids, while the HMW2 preprotein consists of 1,477 amino acids. Comparison of the amino acid sequences reveals ∼99% identity over the first 441 residues and nearly 80% identity over the C-terminal 306 residues (Fig. 1). The middle portions of the proteins share much less homology and are marked by a 62-amino-acid segment in HMW1 that is absent from HMW2 (Fig. 1). Of note, with both HMW1 and HMW2, the cleaved N-terminal 441-amino-acid fragment displays all of the predicted homology to related bacterial proteins, including Bordetella pertussis filamentous hemaglutinin (FHA), Serratia marcescens ShlA (20), Proteus mirabilis HpmA (34), and Vibrio cholerae OmpU (24), among others. Studies of HMW1, FHA, and ShlA indicate that the region of homology plays a critical role in secretion (8, 12, 23, 29).

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the HMW1 and HMW2 proteins, the HMW1-HMW2 chimeric proteins, and the HMW1 and HMW2 MBP fusion proteins. (A) Alignment of the predicted amino acid sequences of HMW1 and HMW2, with a summary of levels of identity and similarity over four contiguous regions. The arrow refers to the point of processing of the HMW1 and HMW2 preproteins, and the open box represents a 62-amino-acid segment present in HMW1 but absent from HMW2. The schematized bars are drawn to scale, and the reference ruler depicts length in increments of 100 amino acids. (B) Chimeric proteins A to H. Bars in black represent sequence derived from the HMW1 protein, while bars in white represent sequence derived from the HMW2 protein. The 62-amino-acid sequence that is absent from HMW2 is shown as a gap. (C) MBP fusion proteins. The six bars show the region of HMW1 (black) or HMW2 (white) fused to MBP (gray), and the numbers to the right of the bars indicate how many amino acid residues from HMW1 or HMW2 are included in the particular fusion protein. The asterisks denote the fusion proteins that correspond to the HMW1 and HMW2 binding domains as defined by analysis of chimeras A to H.

To begin to explore the biological significance of the differing binding specificities of HMW1 and HMW2, in the present study we sought to define the regions of these proteins involved in interaction with the host cell surface. Generation of a series of chimeric proteins and examination of E. coli DH5α producing the resulting proteins suggested that an N-terminal domain of mature HMW1 is responsible for HMW1-mediated adherence and that the corresponding region of HMW2 directs HMW2-mediated adherence. Experiments with purified maltose-binding protein (MBP) fusion proteins confirmed these results, which are relevant to vaccine development and provide insight into the evolution of H. influenzae.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

E. coli DH5α is a nonadherent laboratory strain that served as the host strain for all HMW1 and HMW2 derivatives (22). The plasmid pHMW1-15 contains the entire hmw1 locus cloned into pT7-7, and the plasmid pHMW2-21 contains the entire hmw2 locus, also cloned into pT7-7 (4, 30). The plasmid pHMW1/2 contains coding sequence for the N-terminal 1,024 amino acids of HMW1 fused to the C-terminal 512 amino acids of HMW2, followed by the hmw2B and hmw2C genes; this plasmid was constructed by digesting pHMW1-15 with BsaBI, purifying the 5,850-bp fragment, and fusing this piece to the 4,730-bp BsaBI fragment from pHMW2-21.

To construct chimeras A to H, the initial step involved PCR to generate fragments of hmw1A and hmw2A with 20 bp of overlapping sequence and then recombinant PCR to fuse these fragments and create restriction sites for subsequent cloning. To construct chimeras A, C, E, and G, the relevant PCR-generated fusion was digested with BamHI and DraIII and then ligated to the 10-kb BamHI-DraIII fragment from pHMW1/2. To construct chimeras B, D, and H, the relevant PCR-generated fusion was digested with Eco47III and BanII and then ligated to the 10-kb Eco47III-BanII fragment from pHMW1-15 (Eco47III cleaves within the 5′ region of hmw1A that is absolutely identical to hmw2A). To construct chimera F, the relevant PCR-generated fusion was digested with BanII and then inserted in place of the 568-bp BanII fragment in chimera H.

To generate MBP fusion proteins, fragments of either hmw1A or hmw2A were amplified by PCR and cloned into BamHI-SalI-digested pMALc-2 (New England BioLabs, Beverly, Mass.). The 3′ primers used for PCR included a stop codon in frame with the 3′ end of the relevant hmwA fragment.

E. coli strains were grown on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar or in LB broth and were stored at −80°C in LB broth with 50% glycerol. Plasmids were selected with ampicillin in a concentration of either 50 or 100 μg/ml.

Western blots.

Expression of chimeric HMW proteins was detected by preparing sonicates of the E. coli derivatives containing the chimeric plasmids and resolving these samples by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) using 7.5% polyacrylamide gels (15). Proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and probed with serum Gp1031, a guinea pig-derived polyclonal antiserum that was raised against recombinant HMW1 and recognizes both HMW1 and HMW2. Following washing, the membrane was probed with an anti-rabbit secondary antibody conjugated to horse radishperoxidase (HRP). The signal was detected using an enhanced chemiluminescent reagent (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.) and Blue Sensitive X-ray film (Molecular Technologies, St. Louis, Mo.). Sonicates from DH5α/pHMW1-15 and DH5α/pHMW2-21 served as controls.

Whole-cell (dot) immunoblots.

For whole-cell immunoblots, bacteria were grown to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.8 and then washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), fixed for 30 min at room temperature with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, and resuspended in PBS to an OD600 of 0.5. Aliquots (100 μl) were applied to nitrocellulose filters using a dot blot manifold apparatus (Schleicher and Schuell, Keene, N.H.) and then pulled through the filter by vacuum suction. Following blocking for 1 h with 5% skim milk in Tris-buffered saline, surface-exposed protein was detected using an appropriate primary antibody and then an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody and chemiluminescence (Pierce).

Quantitative adherence assays.

Adherence assays were performed with either Chang epithelial cells (Wong-Kilbourne derivative, clone 1-5c-4 [human conjunctiva]; ATCC CCL20.2) or HaCaT cells (derived from human keratinocytes) (5), which were seeded into wells of 24-well tissue culture plates, as previously described (28). Bacteria were inoculated into broth and incubated overnight. Approximately 2 × 107 CFU were inoculated onto epithelial cell monolayers, and plates were gently centrifuged at 165 × g for 5 min to facilitate contact between bacteria and the epithelial surface. After incubation for 30 min at 37°C in 5% CO2, monolayers were rinsed five times with PBS to remove nonadherent organisms and were treated with trypsin-EDTA (0.05% trypsin–0.5 mM EDTA) in PBS to release them from the plastic support. Well contents were agitated, and dilutions were plated on LB agar to yield the number of adherent CFU per monolayer. Percent adherence was calculated by dividing the number of adherent CFU per monolayer by the number of inoculated CFU.

MAA inhibition of bacterial adherence.

To examine inhibition of bacterial adherence by the lectin MAA, HaCaT cells were seeded onto glass coverslips in 24-well tissue culture plates, as previously described. Monolayers were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS at room temperature for 30 min and were then rinsed with PBS. Subsequently, either PBS alone or PBS containing MAA (5 μg/ml) was added to wells and allowed to incubate at 4°C overnight. Approximately 2 × 107 CFU of the relevant strains was inoculated onto monolayers, and plates were gently centrifuged, incubated, and rinsed, as described for quantitative adherence assays. Ultimately, monolayers were stained with Giemsa as previously described (28), and samples were examined by light microscopy to visualize adherent bacteria.

Purification of MBP fusion proteins.

In order to purify MBP fusion proteins, the relevant DH5α derivatives were inoculated into 500 ml of LB broth and incubated with shaking to an OD600 of 0.5. Gene expression was induced with 0.3 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside for 2 h at 37°C, and bacteria were pelleted and then resuspended in 15 ml of column buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 200 mM NaCl, and 1 mM EDTA) and sonicated. Samples were centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C to remove insoluble material, and supernatants were collected and brought up to a volume of 50 ml with column buffer. The resulting samples were incubated overnight at 4°C with 1 ml of amylose resin (New England BioLabs) in the presence of 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. These mixtures were poured into plastic columns and washed with 50 ml of column buffer. Columns were then eluted with column buffer containing maltose, and the protein content in each fraction was quantitated using the Bradford reagent (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). Purified MBP fusion proteins were checked for purity by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, staining with Coomassie blue. Purified MBP was obtained from New England BioLabs for use as a control.

ELISA quantitation of binding by MBP fusion proteins.

In order to assess binding to epithelial cells by MBP fusion proteins, 150-μl volumes of cells in a suspension with 1.8 × 105 cells/ml were seeded into wells of 96-well tissue culture plates, and plates were incubated overnight. Monolayers were rinsed with minimal essential medium (MEM), and dilutions of purified MBP fusion proteins or MBP alone were added to appropriate wells and allowed to incubate for 30 min at 37°C in 5% CO2. Monolayers were rinsed five times with MEM and then incubated for 30 min at 37°C in 5% CO2 with a 1:500 dilution of anti-MBP antibody (New England BioLab). Next, monolayers were rinsed with MEM and incubated for 30 min at 37°C in 5% CO2 with a 1:10,000 dilution of anti-rabbit antibody conjugated to HRP. Subsequently, monolayers were rinsed four times with MEM and two times with PBS, and then binding was detected using the 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine microwell peroxidase substrate (Kirkegaard and Perry Laboratories, Gaithersburg, Md.), measuring absorbance at 650 nm.

RESULTS

Localization of the HMW1 and HMW2 binding domains using chimeric proteins that contain fragments of the two adhesins.

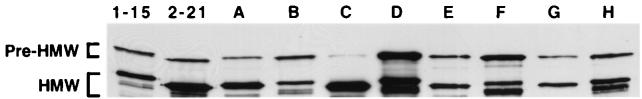

To begin to localize the binding domains of HMW1 and HMW2, we created a pair of complementary chimeric proteins containing the N-terminal portion of one protein and the C-terminal portion of the other. As depicted in Fig. 1, chimera A contains the first 914 amino acids of full-length HMW1 fused to the final 561 amino acids of HMW2, while chimera B contains the first 916 amino acids of full-length HMW2 fused to the final 622 amino acids of HMW1. Since the hmw1BC genes and hmw2BC genes are functionally interchangeable (29), the chimeras were constructed without regard for which hmwBC genes were downstream of the structural gene. As shown in Fig. 2, Western analysis confirmed that both chimeric proteins were synthesized and processed in DH5α (lanes A and B). Whole-cell dot immunoblotting demonstrated surface localization of the chimeras (not shown).

FIG. 2.

Western blot of sonicates of E. coli DH5α transformants producing HMW1, HMW2, or chimeric proteins A to H. Samples were resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and probed with polyclonal antiserum Gp1031. Lanes were loaded as follows: lane 1, wild-type HMW1 (encoded by gene borne on pHMW1-15); lane 2, wild-type HMW2 (encoded by gene borne on pHMW2-21); lane 3, chimera A; lane 4, chimera B; lane 5, chimera C; lane 6, chimera D; lane 7, chimera E; lane 8, chimera F; lane 9, chimera G; lane 10, chimera H. The brackets designate pre-HMW, which refers to the unprocessed high-molecular-weight form, and HMW, which refers to the mature surface-associated form.

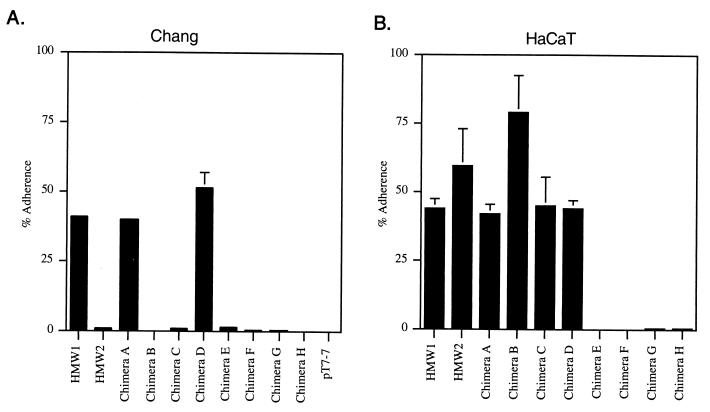

Having constructed these chimeras, we examined their adhesive properties in assays with Chang and HaCaT cells, using DH5α/pHMW1-15 (which contains the hmw1 gene cluster) and DH5α/pHMW2-21 (which contains the hmw2 gene cluster) as controls (4, 30). As shown in Fig. 3, DH5α producing chimera A was capable of high-level adherence to both cell lines, similar to the situation with DH5α/pHMW1-15 (expressing HMW1), while DH5α producing chimera B demonstrated minimal adherence to Chang cells but high-level binding to HaCaT cells, analogous to observations with DH5α/pHMW2-21 (expressing HMW2).

FIG. 3.

Adherence properties of DH5α producing HMW1, HMW2, or the HMW chimeric proteins. Adherence is expressed as a percentage of the original inoculum added to monolayers of Chang cells (A) or HaCaT cells (B). Values represent the mean ± standard error of the mean (error bar) of three measurements from a representative experiment. DH5α/pT7-7 served as a nonadherent control.

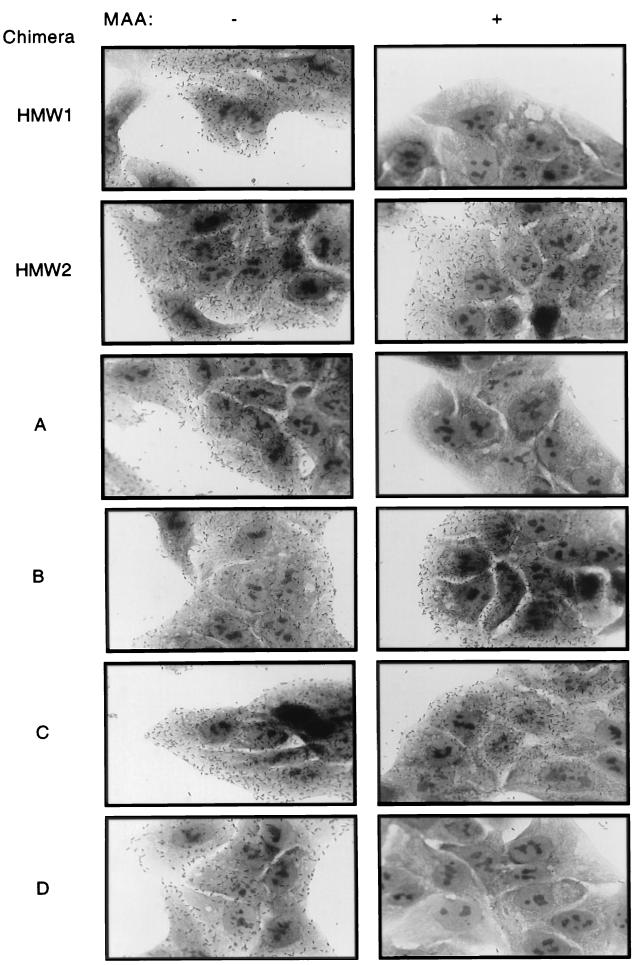

In an effort to distinguish the high-level binding to HaCaT cells by both chimera A and chimera B, we examined the effect of preincubation of monolayers with the lectin MAA. HMW1-mediated adherence to human cells involves interaction with an α2,3-linked sialic acid structure and is inhibited by MAA, while HMW2-mediated adherence is unaffected by this lectin (27). In support of the conclusion that chimera A contains the HMW1 binding domain and chimera B contains the HMW2 binding domain, MAA blocked adherence to HaCaT cells by chimera A but not by chimera B (Fig. 4). Together these results suggest that for both HMW1 and HMW2, the binding domain residues within the first 914 to 916 amino acids of the full-length protein.

FIG. 4.

Light micrographs depicting specific inhibition of HMW1-mediated bacterial adherence to HaCaT cells by pretreatment of monolayers with MAA. HaCaT cells were fixed and pretreated overnight with buffer alone (−) or buffer plus MAA (5 μg/ml) (+). DH5α derivatives producing HMW1, HMW2, or chimeras A to D were incubated with the treated monolayer for 30 min and then rinsed and stained with Giemsa.

To further localize the binding regions of the HMW proteins, we created an additional pair of chimeras. As depicted in Fig. 1, chimera C contains the first 555 amino acids of full-length HMW1 fused to the C-terminal 842 amino acids of HMW2, while chimera D contains the first 553 amino acids of full-length HMW2 fused to the C-terminal 981 amino acids of HMW1. Again Western analysis confirmed that both chimeric proteins were synthesized and processed in DH5α (Fig. 2, lanes C and D), and whole-cell dot immunoblotting demonstrated surface localization (not shown). As shown in Fig. 3, in adherence assays with Chang and HaCaT cells, chimera C resembled HMW2 and chimera D mimicked HMW1. Consistent with these results, MAA inhibited adherence to HaCaT cells by chimera D but not by chimera C (Fig. 4). These results suggest that the HMW1 binding domain is located between amino acids 555 and 914 of full-length HMW1 (corresponding to amino acids 114 to 473 of mature HMW1) and that the HMW2 binding domain lies between amino acids 553 and 916 of full-length HMW2 (corresponding to amino acids 112 to 475 of mature HMW2).

Demonstration that HMW1 and HMW2 adhesive activity may require long stretches of sequence.

In an effort to further map the HMW1 and HMW2 binding domains within the 360- to 364-amino-acid stretches defined by chimeras A to D, we constructed four additional chimeras, representing two different points of fusion. Chimera E contains the first 678 amino acids of HMW1 fused to the C-terminal 800 amino acids of HMW2, and chimera F is the complementary protein with the first 677 amino acids of HMW2 joined to the C-terminal 858 amino acids of HMW1 (Fig. 1). Similarly, chimera G contains the first 798 amino acids of HMW1 fused to the C-terminal 681 amino acids of HMW2, and chimera H is the reciprocal protein with the first 796 amino acids of HMW2 joined to the C-terminal 738 amino acids of HMW1 (Fig. 1). Again, we confirmed that all four chimeric proteins were synthesized, processed, and then surface localized in DH5α (Fig. 2, lanes E to H). Subsequently, we performed adherence assays with Chang and HaCaT cells. As shown in Fig. 3, all four of these chimeras were nonadhesive, suggesting that the HMW1 and HMW2 binding domains require a conformational structure that is disrupted by the described points of fusion. Alternatively, the binding domains may involve discontinuous regions of HMW1 and HMW2 or may be linear epitopes obscured in the chimeric proteins.

Construction of MBP fusion proteins containing portions of the HMW1 or HMW2 binding domain.

In order to confirm our results with the chimeric proteins, we constructed two sets of MBP fusion proteins, one containing portions of the region implicated in HMW1-mediated adherence and the second containing portions of the region suggested to be responsible for HMW2-mediated adherence (Fig. 1C). MBP1 contains amino acids 555 to 1039 of HMW1, corresponding to the HMW1 binding domain as defined by chimeras A to H, plus an additional 125 amino acids C-terminal to the point of fusion of chimeras A and B. MBP1N contains amino acids 555 to 914 of HMW1, representing the minimal region required for HMW1-mediated binding according to analysis of chimeras A to H. MBP1C contains amino acids 678 to 1039 of HMW1 and thus is identical to MBP1 except for the absence of the first 123 amino acids. The N-terminal end of MBP1C is identical to the point of fusion of chimeras E and F. In analogous fashion, MBP2 contains amino acids 553 to 1041 of HMW2, MBP2N contains amino acids 553 to 916 of HMW2, and MBP2C contains amino acids 677 to 1041 of HMW2. All six fusion proteins were overexpressed in E. coli DH5α and then purified by affinity chromatography on amylose columns.

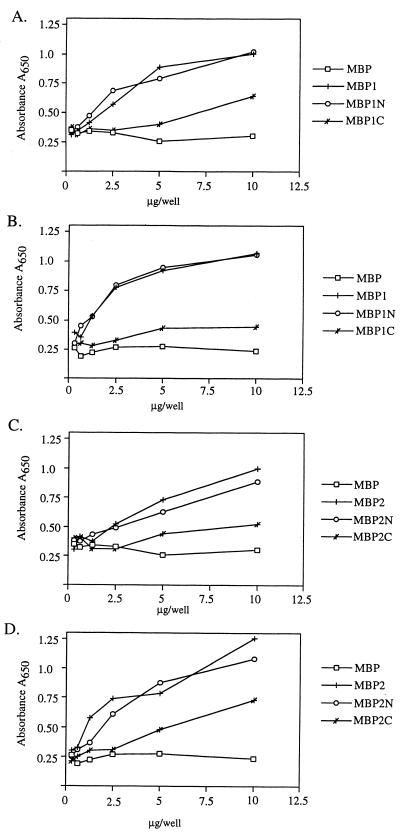

Demonstration that MBP fusion proteins containing the HMW1 or HMW2 binding domain have adhesive activity.

To assess the adhesive properties of the purified MBP fusion proteins, we quantitated binding to monolayers of Chang and HaCaT cells using an ELISA. As shown in Fig. 5 A and B, MBP1 and MBP1N demonstrated significant concentration-dependent binding to both cell lines. MBP1C demonstrated reduced binding that increased modestly with increasing concentrations. Purified MBP alone served as a negative control and was capable of minimal binding, with no significant change at concentrations between 2.5 μg/ml and 10 μg/ml. Similar to observations with the HMW1 derivatives, binding by MBP2 and MBP2N was significant and concentration dependent with both Chang and HaCaT cells, and binding by MBP2C was relatively reduced (Fig. 5C and D). These data corroborate our results with DH5α producing the chimeric proteins and provide evidence that the 124 amino acids between residues 555 and 678 in HMW1 and the 125 amino acids between residues 553 and 677 in HMW2 are essential for full-level adhesive activity.

FIG. 5.

Binding properties of MBP fusions. Binding by the purified MBP fusion proteins and MBP alone was quantitated by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using either Chang or HaCaT cells. Proteins were added at increasing concentrations to a 96-well plate containing epithelial cell monolayers, monolayers were rinsed, and binding was detected by sequential incubation with anti-MBP antibody, HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody, and the 3,3′, 5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine microplate reagent. Absorbance was read at 650 nm. (A) HMW1-derived MBP fusion proteins binding to Chang cells; (B) HMW1-derived MBP fusion proteins binding to HaCaT cells; (C) HMW2-derived MBP fusion proteins binding to Chang cells; (D) HMW2-derived MBP fusion proteins binding to HaCaT cells.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we generated a series of complementary chimeric proteins to localize the binding domains of the HMW1 and HMW2 adhesins. In pursuing this approach, we exploited the sequence similarity between HMW1 and HMW2, reasoning that chimeric proteins might fold well enough to preserve the conformations required for adherence. With both HMW1 and HMW2, our results localized the binding domain to an ∼360-amino-acid stretch near the N terminus of the mature protein. Interestingly, chimeric proteins with points of fusion within this ∼360-amino-acid region were nonadhesive, suggesting that the binding domain may be a conformational structure or may require the surrounding residues for proper exposure. As another possibility, the binding domain may be formed by discontinuous segments that interact to form a binding pocket.

Binding studies with two sets of MBP fusion proteins, one containing segments of HMW1 and the second containing segments of HMW2, confirmed our results with the chimeric proteins, implicating the same ∼360-amino-acid region. Of note, elimination of 123 amino acids from the N terminus of the HMW1 binding domain and 124 amino acids from the N terminus of the HMW2 binding domain resulted in diminished binding as measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. On the other hand, compared with purified MBP, the resulting proteins remained capable of low-level binding that increased modestly in a concentration-dependent manner, suggesting that some portion of the binding domain was still intact. Together these findings argue that, for both HMW1 and HMW2, formation of a conformational structure dependent on a long stretch of sequence is required for full-level adherence.

It is interesting that bacteria expressing the HMW2 binding domain demonstrated only minimal adherence to Chang cells, while the purified MBP fusion proteins containing the HMW2 binding domain were capable of high-level binding to these cells. One possible explanation for this apparent discrepancy is that HMW2 receptor molecules on the surface of Chang cells are relatively obscured, making them unavailable to whole bacteria but accessible to soluble purified protein. Alternatively, compared with adhesin on the surface of the organism, purified protein may have a slightly greater affinity for the host cell receptor structure. Still another possibility is that the assays for bacterial adherence and protein binding have different sensitivities.

Analysis of the ∼360-amino-acid stretches in HMW1 and HMW2 that mediate adherence to epithelial cells reveals no significant overall homology to other known adhesins. However, it is noteworthy that this region in HMW2 contains an arginine-glycine-aspartic acid (RGD) motif at amino acids 785 to 787, raising the possibility that this tripeptide contributes to HMW2 adhesive activity. Experiments with B. pertussis have demonstrated that the RGD motif located at amino acids 1097 to 1099 in FHA mediates binding to macrophages, apparently via interaction with the leukocyte integrin referred to as LRI-IAP (11, 21). Arguing against the hypothesis that the HMW2 RGD motif influences adherence, examination of the sequence of the HMW2-like protein from H. influenzae strain 5 reveals no RGD tripeptide (S. Barenkamp, personal communication).

In recent work, we have found that most nontypeable H. influenzae isolates expressing HMW adhesins produce both an HMW1-like protein and an HMW2-like protein (31; J. W. St. Geme III and K. Burmeister, unpublished data). Furthermore, experiments with a number of epidemiologically distinct strains indicate that the hmw gene clusters are present in identical physical locations on the chromosome (St. Geme and Burmeister, unpublished data). Together these observations suggest that the development of two hmw loci occurred relatively early in the evolution of H. influenzae, presumably via gene duplication. The retention of two distinct HMW adhesins over time argues that both are important to the pathogenic potential of the organism and is reminiscent of the situation with the Neisseria Opa proteins. Both Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Neisseria meningitidis express a number of different Opa proteins that function as adhesins (13, 14, 16, 35). These proteins are phase variable (18, 26), and switching from one Opa protein to another alters the binding and invasion characteristics of the organism (7, 9, 14, 17, 36). Similar to observations with the Opa proteins, we have recently demonstrated that both HMW1 and HMW2 are subject to phase variation, with potential influences of this variation on ultimate cellular interactions (6).

The fact that the HMW adhesins are expressed by the majority of nontypeable H. influenzae strains and the suggestion that these proteins play an important role in colonization and tissue tropism makes them strong candidates as vaccine antigens. In support of their potential as vaccine components, Barenkamp has shown that immunization of chinchillas with purified HMW1 or HMW2 prior to middle ear inoculation with strain 12 is partially protective against development of otitis media (1). Interestingly, the region defined to contain the adhesive domain corresponds to the region of greatest divergence between HMW1 and HMW2, with 40% identity and 58% similarity. This finding suggests that if the adhesive domains are to be used as subcomponents of a vaccine, both adhesins may be necessary. Future studies will explore the strain-to-strain conservation of the adhesive domains and the immunogenicity of these regions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant 1RO1 DC-02873 from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (J.W.S.G.), by a training grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (S.D.), and by funds from Aventis Pasteur (J.W.S.G.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Barenkamp S J. Immunization with high-molecular-weight adhesion proteins of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae modifies experimental otitis media in chinchillas. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1246–1251. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.4.1246-1251.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barenkamp S J, Bodor F F. Development of serum bactericidal activity following nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae acute otitis media. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1990;9:333–339. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199005000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barenkamp S J, Leininger E. Cloning, expression, and DNA sequence analysis of genes encoding nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae high-molecular-weight surface-exposed proteins related to filamentous hemagglutinin of Bordetella pertussis. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1302–1313. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.4.1302-1313.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barenkamp S J, St. Geme J W., III Genes encoding high-molecular-weight adhesion proteins of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae are part of gene clusters. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3320–3328. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.8.3320-3328.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boukamp P, Petrussevska R T, Breitkreutz D, Hornung J, Markham A, Fusenig N E. Normal keratinization in a spontaneously immortalized aneuploid human keratinocyte cell line. J Cell Biol. 1988;106:761–771. doi: 10.1083/jcb.106.3.761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dawid S, Barenkamp S J, St. Geme J W., III Variation in expression of the Haemophilus influenzae HMW adhesins: a prokaryotic mechanism reminiscent of eukaryotes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:1077–1082. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.3.1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Vries F P, van Der Ende A, van Putten J P, Dankert J. Invasion of primary nasopharyngeal epithelial cells by Neisseria meningitidis is controlled by phase variation of multiple surface antigens. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2998–3006. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.2998-3006.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grass S, St. Geme J W., III Maturation and secretion of the non-typable Haemophilus influenzae HMW1 adhesin: roles of the N-terminal and C-terminal domains. Mol Microbiol. 2000;36:55–67. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gray-Owen S D, Lorenzen D R, Haude A, Meyer T F, Dehio C. Differential Opa specificities for CD66 receptors influence tissue interactions and cellular response to Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:971–980. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.6342006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hultgren S J, Abraham S, Caparon M, Falk P, St. Geme III J W, Normark S. Pilus and nonpilus bacterial adhesins: assembly and function in cell recognition. Cell. 1993;73:887–901. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90269-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ishibashi Y, Claus S, Relman D A. Bordetella pertussis filamentous hemagglutinin interacts with a leukocyte signal transduction complex and stimulates bacterial adherence to monocyte CR3 (CD11b/CD18) J Exp Med. 1994;180:1225–1233. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.4.1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacob-Dubuisson F, Buisine C, Willery E, Renauld-Mongeniw G, Locht C. Lack of functional complementation between Bordetella pertussis filamentous hemagglutinin and Proteus mirabilis HpmA hemolysin secretion machineries. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:775–783. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.3.775-783.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.James J F, Lammel C J, Draper D L, Brooks G F. Attachment of Neisseria gonorrhoeae phenotype variants to eukaryotic cells and tissues. In: Danielson D, Normark S, editors. Genetics and immunobiology of pathogenic Neisseria. Umea, Sweden: University of Umea; 1980. pp. 213–216. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kupsch E M, Knepper B, Kuroki T, Heuer I, Meyer T F. Variable opacity (Opa) outer membrane proteins account for the cell tropisms displayed by Neisseria gonorrhoeae for human leukocytes and epithelial cells. EMBO J. 1993;12:641–651. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05697.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lambden P, Heckels J, James L, Watt P. Variations in surface protein composition associated with virulence properties in opacity types of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Gen Microbiol. 1979;114:305–312. doi: 10.1099/00221287-114-2-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Makino S, van Putten J P, Meyer T F. Phase variation of the opacity outer membrane protein controls invasion by Neisseria gonorrhoeae into human epithelial cells. EMBO J. 1991;10:1307–1315. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07649.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murphy G L, Connell T, Barritt D S, Koomey M, Cannon J G. Phase variation of gonococcal protein II: regulation of gene expression by slipped-strand mispairing of a repetitive DNA sequence. Cell. 1989;56:539–547. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90577-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murphy T F, Bernstein J M, Dryja D M, Campagnari A A, Apicella M A. Outer membrane protein and lipooligosaccharide analysis of paired nasopharyngeal and middle ear isolates in otitis media due to nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae: pathogenic and epidemiologic observations. J Infect Dis. 1987;5:723–731. doi: 10.1093/infdis/156.5.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poole K, Schiebel E, Braun V. Molecular characterization of the hemolysin determinant of Serratia marcescens. J Bacteriol. 1988;173:3177–3188. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.7.3177-3188.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Relman D, Tuomanen E, Falkow S, Golenbock D, Saukkonen K, Wright S. Recognition of a bacterial adhesion by an integrin: macrophage CR3 (alpha M beta 2, CD11b/CD18) binds filamentous hemagglutinin of Bordetella pertussis. Cell. 1990;61:1375–1382. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90701-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schonherr R, Tsolis R, Focareta T, Braun V. Amino acid replacements in the Serratia marcescens hemolysin ShlA define sites involved in activation and secretion. Mol Microbiol. 1993;6:1229–1237. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sperandio V, Giron J, Silveira W, Kaper J. The OmpU outer membrane protein, a potential adherence factor of Vibrio cholerae. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4433–4438. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.11.4433-4438.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spinola S M, Peacock J, Denny F W, Smith D L, Cannon J G. Epidemiology of colonization by nontypable Haemophilus influenzae in children: a longitudinal study. J Infect Dis. 1986;154:100–109. doi: 10.1093/infdis/154.1.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stern A, Brown M, Nickel P, Meyer T F. Opacity genes in Neisseria gonorrhoeae: control of phase and antigenic variation. Cell. 1986;47:61–71. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90366-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.St. Geme J W., III The HMW1 adhesin of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae recognizes sialyated glycoprotein receptors on cultured human epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3881–3889. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.9.3881-3889.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.St. Geme J W, III, Falkow S. Haemophilus influenzae adheres to and enters cultured human epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1990;58:4036–4044. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.12.4036-4044.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.St. Geme J W, III, Grass S. Secretion of the Haemophilus influenzae HMW1 and HMW2 adhesins involves a periplasmic intermediate and requires the HMWB and HMWC proteins. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:617–630. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.St. Geme J W, III, Falkow S, Barenkamp S J. High-molecular-weight proteins of nontypable Haemophilus influenzae mediate attachment to human epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:2875–2879. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.7.2875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.St. Geme J W, III, Kumar V V, Cutter D, Barenkamp S J. Prevalence and distribution of the hmw and hia genes and the HMW and Hia proteins among genetically diverse strains of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 1998;66:364–368. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.1.364-368.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trottier S, Stenberg K, von Rosen I A, Svanborg C. Haemophilus influenzae causing conjuctivitis in day-care children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1991;10:578–584. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199108000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Turk D C. The pathogenicity of Haemophilus influenzae. J Med Microbiol. 1984;18:1–16. doi: 10.1099/00222615-18-1-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Uphoff T S, Welch R A. Nucleotide sequencing of the Proteus mirabilis calcium-independent hemolysin genes (hpmA and hpmB) reveals sequence similarity with the Serratia marcescens hemolysin genes (shlA and shlB) J Bacteriol. 1990;172:1206–1216. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.3.1206-1216.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Watt P J, Ward M E. Adherence of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and other Neisseria species to mammalian cells. In: Beachey E, editor. Bacterial adherence. New York, N.Y: Chapman and Hall; 1981. pp. 255–288. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weel J F, Hopman C T, van Putten J P. In situ expression and localization of Neisseria gonorrhoeae opacity proteins in infected epithelial cells: apparent role of Opa proteins in cellular invasion. J Exp Med. 1991;173:1395–1405. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.6.1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]