Abstract

The molecular mechanisms that maintain cellular identities and prevent dedifferentiation or transdifferentiation remain mysterious. However, both processes are transiently used during animal regeneration. Therefore, organisms that regenerate their organs, appendages, or even their whole body offer a fruitful paradigm to investigate the regulation of cell fate stability. Here, we used Hydra as a model system and show that Zic4, whose expression is controlled by Wnt3/β-catenin signaling and the Sp5 transcription factor, plays a key role in tentacle formation and tentacle maintenance. Reducing Zic4 expression suffices to induce transdifferentiation of tentacle epithelial cells into foot epithelial cells. This switch requires the reentry of tentacle battery cells into the cell cycle without cell division and is accompanied by degeneration of nematocytes embedded in these cells. These results indicate that maintenance of cell fate by a Wnt-controlled mechanism is a key process both during homeostasis and during regeneration.

Zic4 maintains epithelial cell fate in <italic>Hydra</italic> tentacles, causing the generation of multi-footed heads when knocked-down.

INTRODUCTION

When cells differentiate during embryonic development or adult regeneration, they acquire specific characteristics, a specialization compensated by a loss of plasticity (1). The protection of the identity of terminally differentiated cells relies on mechanisms that are poorly understood. Therefore, model systems that readily reactivate developmental processes, such as the freshwater polyp Hydra, help decipher the mechanisms underlying the balance between plastic cell fates and stable cell identities. Hydra are simple animals whose body is organized along a single oral/aboral axis. On the oral end, the head structure includes the mouth surrounded by tentacles, while on the aboral end a foot structure is used that allows the animal to attach to solid substrates. The tip of the head, named the hypostome, harbors a head organizer required to maintain apical patterning in intact animals.

In line with predicted auto- and cross-catalytic regulations (2), the head organizer activity is positively regulated by Wnt3/β-catenin signaling (3–5) and restricted by the transcription factor Sp5 (6). When Sp5 expression is knocked down, Wnt3/β-catenin signaling is derepressed along the body column and ectopic head formation occurs (6). During apical regeneration, the head organizer is reestablished from somatic gastric tissue within 10 to 12 hours (7); this de novo organizer instructs the formation of the complete head, including hypostome and tentacles, a role also under the control of Wnt3/β-catenin signaling and restricted by the transcription factor Sp5. Besides Wnt3/β-catenin signaling, signaling via protein kinase C (8) and Notch (9) positively modulate tentacle formation, while casein kinase 1 activity acts negatively (10). Some additional regulators contribute to tentacle formation like the orphan protein ks1 (11, 12), the peptide Hym-301 (13, 14), and the homeodomain transcription factors HyAlx, possibly via protein kinase C (PKC) signaling (15), and Margin, downstream of Wnt signaling (16). However, it is still unclear how cells at the base of the hypostome acquire a tentacle identity.

Hydra polyps are composed of two epithelial cell layers, the epidermis and the gastrodermis, which in the body column are populated with three distinct stem cell populations, the epidermal and gastrodermal epithelial stem cells (ESCs), and the multipotent interstitial stem cells (ISCs) (17). The ESC populations are multifunctional differentiated epithelial cells that proliferate continuously in the body column and terminally differentiate when they reach the apical (head) or basal (foot) regions (18). When epidermal epithelial cells located in the upper body column reach the tentacle zone, they become committed to the tentacle battery cell (TBC) fate and differentiate as TBCs once they enter the tentacle roots (19–21). This process is characterized by a cell cycle arrest in G2, the change of epidermal epithelial cell shape, and the incorporation by each TBC of 10 to 20 mechanosensory cells called nematocytes (or stinging cells), one large located centrally named stenotele surrounded by numerous smaller ones (22, 23). Each nematocyte houses a venom capsule named nematocyst, whose content is discharged when a specialized cilium, the cnidocil, is stimulated (24). More distally, the epidermal layer of tentacles is exclusively made of fully differentiated TBCs that get passively displaced toward the tentacle tips and are ultimately sloughed off after several days (19, 25). At the basal extremity, the epidermal epithelial cells of the basal disc (foot) terminally differentiate as basal disc cells (BDCs), which produce acid mucopolysaccharide (MPS) droplets that facilitate the attachment to substrates (26). Thus, both the tentacles and the foot are made of highly differentiated cells.

Cellular plasticity in Hydra is well documented for cells of the interstitial lineage, namely, gland cells and nerve cells (27–29). Nevertheless, Hydra depleted of their interstitial cell lineage can fully regenerate (30, 31), highlighting the key role of epithelial cells in the reactivation of developmental processes. We actually showed that in such animals, epithelial cells modify their genetic program within a week following depletion of the interstitial cells, indicating their high potential for plasticity (32). However, the ability of terminally differentiated epithelial cells to acquire an alternative identity in Hydra is unknown. Here, we identified a zinc finger transcription factor, Zic4, expressed under the control of Wnt3/β-catenin signaling and Sp5, which contributes to induce tentacle cell fate. When Zic4 is knocked down, the maintenance and proper development of tentacles is impaired and, unexpectedly, the TBCs transdifferentiate into BDCs. The transformed tentacles are able to attach to substrates, thus adopting a functional foot behavior. This marked change in cell identity, because of a decrease in the expression level of a single transcription factor, provides insight into the gene regulatory networks governing the choice between two epithelial cell fates in Hydra. Given the broad conservation of the genetic module that regulates Zic4, this network might also operate in other metazoans.

RESULTS

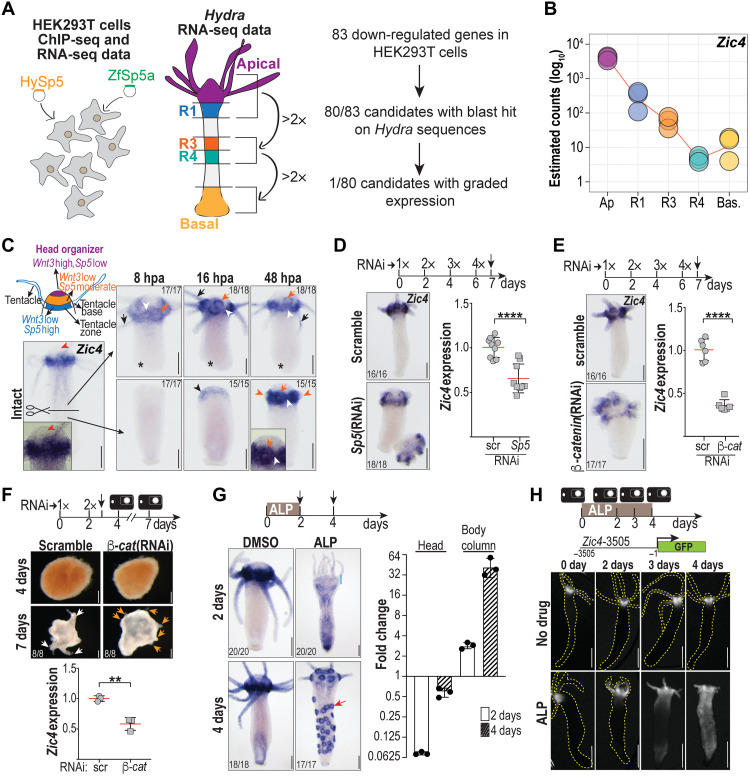

The Zic4 transcription factor gene is an Sp5 target gene

Exploiting RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) and chromatin immunoprecipitation–sequencing (ChIP-seq) data in human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells overexpressing the Hydra and zebrafish Sp5 transcription factors, we have previously identified 83 putative Sp5 direct target genes (6). From the 80 targets detected in the Hydra transcriptome, we identified the zinc finger transcription factor Zic4 as the unique gene displaying an expression pattern that is graded from apical toward the basal end of the animal (Fig. 1, A and B; fig. S1; and dataset S1) (33). We thus focused on this transcription factor to characterize its role and mechanism of action. We found Zic4 predominantly expressed in the tentacle zone of intact animals, reexpressed between 4 and 8 hours post-amputation (hpa) in apical-regenerating tissues (Fig. 1C and fig. S2). Among the four Zic-related genes expressed in Hydra, Zic4 is the only one to display these features (figs. S1 and S2 and table S1).

Fig. 1. Screening strategy to identify Zic4 as an Sp5 target gene.

(A) Procedure to identify Sp5 target genes among 83 human genes down-regulated by Sp5. (B) RNA-seq expression profile of Zic4 in intact Hv_Jussy animals (fig. S2). (C) Scheme depicting Wnt3 and Sp5 apical expression domains. In intact animals, Zic4 is expressed in tentacle zone (white arrowheads), tentacle base (orange arrows), and tentacles (black arrows) but not apically (red arrowheads). After bisection, Zic4 is up-regulated in apical-regenerating tips, here at 16 (black arrowhead) and 48 hpa (orange arrowheads: tentacle rudiments) but not during basal regeneration (asterisks, fig. S2). (D and E) Zic4 down-regulation detected by ISH and qPCR (day 7) in animals knocked down for Sp5 (D) or β-catenin (E) after 4 electroporations (4x) of scramble or specific small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) (fig. S3A). (F) Delayed apical differentiation in reaggregates obtained from animals knocked down for β-catenin after 2 electroporations (2x) of siRNAs. The black vertical arrow indicates dissociation time. At day 7, white arrows point to differentiated heads and orange arrows to apical rudiments (fig. S3B), while Zic4 expression levels measured by qPCR are reduced (bottom). (G) Modulations of Zic4 expression upon ALP treatment detected by ISH and qPCR. On day 2, Zic4 expression is markedly reduced in the apex (blue line); on day 4, Zic4 is up-regulated along the body column forming ectopic tentacle rings (red arrow, fig. S4). (H) GFP fluorescence in Zic4-3505:GFP transgenic animals left untreated (top row) or exposed to ALP (bottom row). In (D) to (G), each data point represents one biological replicate. **P ≤ 0.01; ****P ≤ 0.0001. Error bars indicate SDs. Scale bars, 200 μm.

Zic4 appears positively regulated by Sp5 and Wnt/β-catenin signaling in homeostatic conditions, as Zic4 expression is notably reduced in the tentacle zone after Sp5 or β-catenin knockdown by RNA interference (RNAi) (Fig. 1, D and E, and fig. S3A). To test Zic4 regulation in conditions where organizer activity gets reestablished in multiple spots (34), we performed reaggregation experiments from tissues knocked down for β-catenin (Fig. 1F and fig. S3B). In control conditions, Hydra reaggregates can regenerate and present axes that form tentacles emerging 5 days after the second electroporation (EP2). When β-catenin is down-regulated, the levels of Zic4 are reduced about twofold and the aggregates cannot form tentacles in the manner control animals do. The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway can also be ubiquitously activated by incubating the animals in alsterpaullone (ALP), a treatment that efficiently promotes stabilization of β-catenin in Hydra (35). After a 2-day treatment, we observed a dual regulation for Zic4, first a transient down-regulation in the apical region accompanied by an overall up-regulation along the body column, followed 2 days later by the appearance of an “Octopus” phenotype, characterized by multiple Zic4-expressing rings, each ring corresponding to the base of an ectopic tentacle (Fig. 1G and fig. S4). This dynamic expression pattern of Zic4 both in the tentacle zone and along the body column when Wnt/β-catenin signaling is up-regulated indicates that Zic4 is downstream of Wnt/β-catenin signaling.

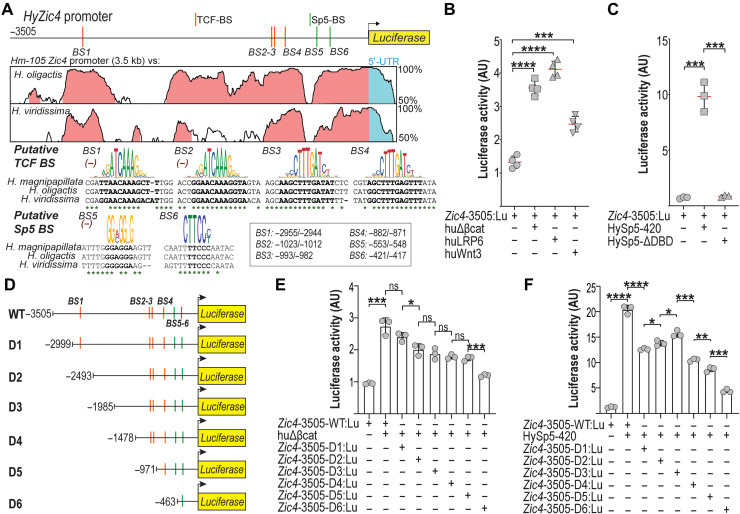

The Zic4 promoter is positively regulated by Wnt/β-catenin and Sp5

To test whether Wnt/β-catenin regulates Zic4 directly, we characterized a 3505–base pair (bp) fragment upstream to the Zic4 transcription start site and produced a Zic4-3505:GFP transgenic line that drives green fluorescent protein (GFP) fluorescence in the tentacle zone mimicking the Zic4 expression pattern (Fig. 1H). Upon ALP treatment, the expression of GFP is enhanced in the upper body column, indicating a positive regulation of the Zic4-3505 promoter via canonical Wnt signaling (Fig. 1H). This regulation is possibly direct as the 3505-bp Zic4 upstream sequences contain four consensus T cell factor/lymphoid enhancer factor (TCF/LEF) binding sites (Fig. 2A). When expressed in HEK293T cells, the Zic4-3505:luciferase construct is up-regulated when human β-catenin, Wnt3, LRP6, or full-length Sp5 are overexpressed (Fig. 2, B and C). We produced a series of deletion mutants of the Zic4-3505 promoter (Fig. 2D) and noted a two-step reduction in the levels of luciferase in HEK293T cells in the presence of active β-catenin when the most upstream TCF-BS1 is deleted and then when the most proximal TCF-BS4 is additionally removed (Fig. 2E). In the presence of Hydra Sp5, we recorded the most significant reductions of luciferase activity when three regions are removed: (i) the most upstream 500 bp (−3505 to −2999), (ii) the −1985 to −1478 region, and (iii) the −978 to −463 region that contains TCF-BS4 and Sp5-BS5 (Fig. 2F). These data demonstrate a positive regulation by Wnt/β-catenin signaling and Sp5 on Zic4 expression, likely direct in the mammalian HEK293T cells. Overall, we concluded that Zic4 is an excellent candidate for a transcription factor directly regulated by Wnt/β-catenin and Sp5, during both homeostasis and regeneration in Hydra.

Fig. 2. Wnt/β-catenin signaling and Sp5 up-regulate HyZic4 expression in HEK293T cells.

(A) Map of the 3505-bp genomic region encompassing the HyZic4 promoter of H. magnipapillata (Hm-105) and phylogenetic footprinting plot comparing this region to the corresponding region in the H. oligactis and H. viridissima genomes. Evolutionarily conserved modules (at least 70% bp identity over a 100-bp sliding window) are shown in pink in the Vista alignment plot. The PMW logo for the TCF and Sp5 binding sites is displayed above each sequence alignment. Nucleotide positions conserved across the three species are marked by asterisks. Orange bars, TCF binding sites (TCF-BS); green bars, Sp5 binding sites (Sp5-BS). When a TCF-BS or Sp5-BS was identified on the negative strand of the HyZic4 promoter region, the reverse complement version of the Positional Weight Matrix (PWM) logo was used as a reference and indicated with the (−) symbol. (B and C) Luciferase activity driven by the HyZic4-3505 promoter in HEK293T cells coexpressing either huΔβ-Cat, a constitutively active form of β-catenin (B), or HySp5 full-length (HySp5-420) or HySp5 lacking its DNA binding domain (HySp5-ΔDBD) (C). (D) Schematic view of the HyZic4 promoter deletion constructs (D1 to D6). (E and F) Luciferase activity driven by the HyZic4 promoter either complete (3505 bp) or deleted as shown in (D) in HEK293T cells coexpressing huΔβ-Cat in (E) or HySp5 in (F).

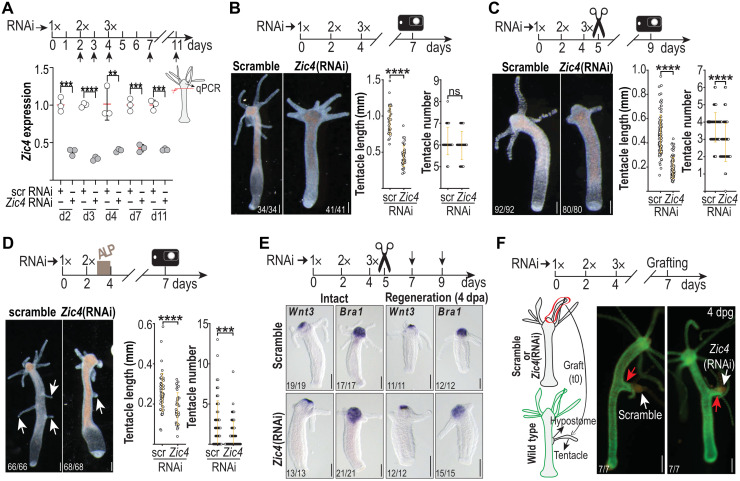

Zic4 is required for tentacle development and tentacle maintenance

To explore Zic4 function, we knocked down Zic4 by RNAi. We measured the efficiency of Zic4 RNAi at different time points during the procedure and detected a significant down-regulation of Zic4 starting 1 day after the first electroporation (EP1) and lasting until at least 11 days after the procedure has been initiated (Fig. 3A). Thereafter, we consistently performed experiments within this time window. Three days after EP3, intact Zic4(RNAi) animals exhibit tentacles with half the length of those in control animals, while the overall tentacle number is not affected (100%; n = 100) (Fig. 3B and fig. S5A). In contrast, apical-regenerating Zic4(RNAi) animals regenerate not only shorter but also 25% fewer tentacles (100%; n = 99) (Fig. 3C and fig. S5B). Overactivation of Wnt signaling through ALP treatment leads normally to ectopic tentacle formation (35). We found that when ALP treatment is combined with Zic4 down-regulation through RNAi, the development of ectopic tentacles along the body column is strongly impaired, pointing out to a strong genetic interaction between Wnt/β-catenin signaling and Zic4 (Fig. 3D and fig. S5C). We also noticed that the expression of two components of the head organizer, Wnt3 and HyBra1 (34), is not affected in intact or regenerating Zic4(RNAi) animals, suggesting that Zic4 is required neither for the maintenance nor for the formation of a functional head organizer (Fig. 3E and fig. S6). When we transplanted apical tissue from control and Zic4(RNAi) animals into actin:GFP transgenic animals, we observed a similar induction of a secondary body axis, a hallmark of a functional head organizer (Fig. 3F). We concluded that Zic4 operates downstream of the head organizer and is required for tentacle maintenance and tentacle formation.

Fig. 3. HyZic4 is required for tentacle maintenance and tentacle development but not for head organizer activity.

(A) Zic4 knockdown efficiency detected by qPCR. Vertical black arrows indicate time points of RNA extraction. Each data point represents one biological replicate. (B to E) Impact of Zic4 knockdown in intact (B, E), apical-regenerating (C, E), and ALP-treated (D) Hv_Basel animals electroporated three times (3x) with siRNAs. Zic4(RNAi) animals exhibit shorter (B to D) and fewer tentacles (C and D). Each data point represents one animal (see more animals in fig. S5). White arrows: ectopic tentacles. **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001; ****P ≤ 0.0001. (E) Wnt3 and Bra1 expression in intact (left) and head-regenerating (right) Zic4(RNAi) animals fixed on day 7 (intact) and day 9 (apical regenerating) (see fig. S6). (F) Homeostatic head organizer activity in Zic4(RNAi) animals . Hypostomal tissue and a tentacle of intact nontransgenic Hv_AEP2 animals electroporated three times (3x) with scramble or Zic4 siRNAs were transplanted laterally onto the body column of a GFP+ hoTG host (white arrows). All hosts have grown ectopic axes (red arrows) 4 days post-grafting (dpg). Scale bars, 200 μm (B to E) and 250 μm (F).

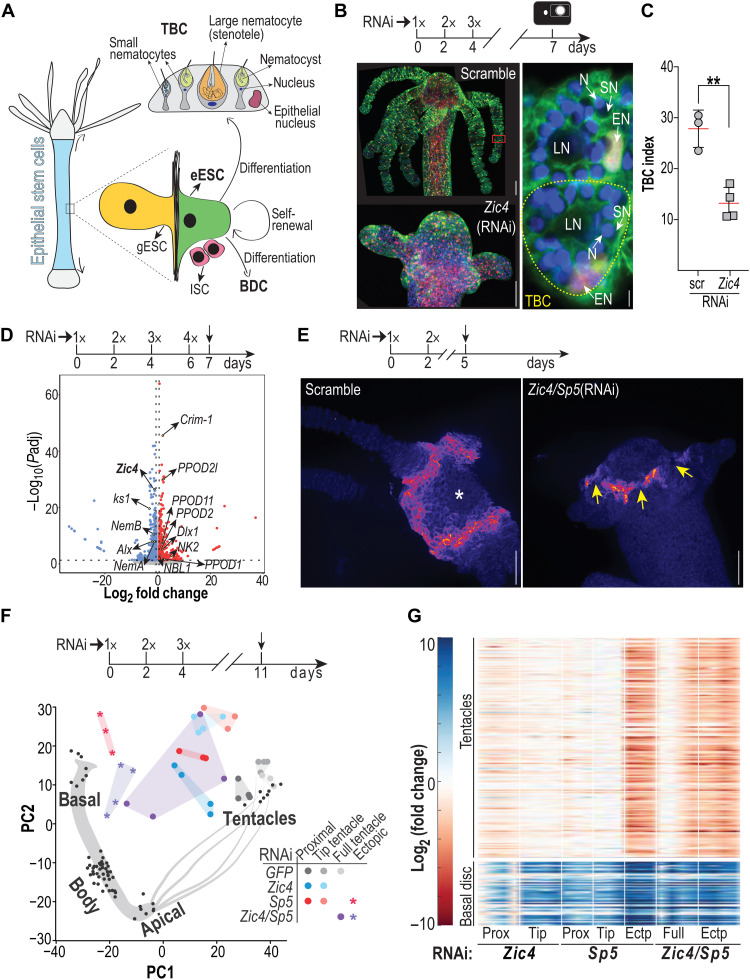

Next, we sought to characterize the cellular behavior that underlies deficient tentacle maintenance and tentacle formation in Zic4(RNAi) animals. The characteristic cells that provide the functionality of the tentacles are the tentacle battery cells (TBCs) in the epidermis, which terminally differentiate in the tentacle roots from the epidermal ESCs that reach this zone when displaced from the body column (Fig. 4A). To monitor the cellular composition of tentacles, we used transgenic Hydra constitutively expressing a tandem cell cycle sensor (TCCS) in epidermal epithelial cells (Fig. 4B). We noted a twofold decrease in the TBC number after Zic4(RNAi) counted either after maceration or on whole mounts (Fig. 4C and fig. S7). Nevertheless, we found that the level of epithelial apoptosis in the apical region and the level of epithelial proliferation in the body column were unchanged after Zic4 knockdown (fig. S8). Similarly, we did not record any obvious change in the displacement behavior of epidermal epithelial cells toward the head region (fig. S9). Thus, the altered size of the tentacles and the lower number of TBCs cannot be explained by decreased proliferation, increased apoptosis, or reduction in the number of cells allocated to tentacles. Ultimately, we postulated that the reduced size of the tentacles could be the result of an overall shape change on the part of the cells that compose them.

Fig. 4. Zic4(RNAi) leads to an up-regulation of genes normally expressed in epithelial cells of the basal disc.

(A) Illustration of the three stem cell populations that constitute Hydra tissues: epidermal and gastrodermal epithelial stem cell (eESC and gESC); interstitial stem cell (ISC). Epithelial ESCs give rise to TBCs in tentacle roots, to basal disc cells (BDCs) when they reach the basal disc. A mature TBC typically contains one large nematocyte (LN) and 10 to 20 small nematocytes (SNs), each housing a venom capsule named nematocyst. (B) Magnified view of TBCs in transgenic TCCS Hydra that express cytoplasmic/nuclear GFP and nuclear mCherry in epidermal epithelial cells. Red square: enlarged TBCs, one being outlined with a yellow dashed line; EN, epithelial nuclei; N, DAPI-stained nuclei; LN, SN: as in (A). (C) TBC index counted as the number of TBCs per 100 gastrodermal epithelial cells on macerated apical regions from scramble and Zic4(RNAi) animals taken 3 days after EP3 (3x). (D) Volcano plot representing differentially expressed genes in apical tissue of scramble and Zic4(RNAi) animals. (E) ks1 expression in the tentacle zone of scramble and Zic4/Sp5(RNAi) animals taken 3 days after EP2 (2x). Yellow arrows: Cells in the tentacle zone that no longer express ks1; asterisk: mouth opening. (F) RNA-seq performed on complete or dissected regions of tentacles and projection into a PCA space, generated by positional RNA-seq. (G) Heatmap showing differential expression of tentacle and basal disc markers. Full, whole tentacles; Prox, proximal tentacle region; Tip, distal tentacle region; Ectp, ectopic structures. **P ≤ 0.01. Scale bars, 100 and 5 μm for enlarged view (B and E).

Genes specifically expressed in the basal disc get up-regulated in tentacles upon Zic4 knockdown

To evidence molecular markers downstream of Zic4, we performed comparative RNA-seq analysis on apical regions of scramble and Zic4(RNAi) animals. One day after EP4, the comparison reveals a notable decrease in the transcript level of four tentacle markers ks1, HyAlx, Nematocilin A, and Nematocilin B (Fig. 4D and dataset S2) (12, 15, 36, 37), consistent with the Zic4(RNAi)–induced loss of TBCs. While nematocilins are expressed in the nematocytes anchored in the TBCs, ks1 and HyAlx have been identified as genes exclusively expressed in TBCs, responsible for tentacle development in case of ks1 (12) and tentacle patterning in case of HyAlx (15). As expected, hybridization chain reaction (HCR) RNA–fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) experiments showed a striking decrease in ks1 expression upon down-regulation of Zic4 and Sp5 (Fig. 4E). Furthermore, we noted an up-regulation of genes normally expressed in the basal disc, including the peroxidases PPOD1, PPOD2, PPOD2l, and PPOD11, the homeogenes Dlx1 and NK2, the transmembrane bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) regulator Crim-1, and the BMP antagonist NBL1 (Fig. 4D and table S2). These findings suggest that Zic4 controls tentacle identity by repressing basal gene expression.

To further investigate gene expression changes that occur in tentacles of animals knocked down for Zic4 and/or Sp5, we used proximal and distal tentacle tissue for RNA-seq analysis (fig. S10, A and B). When projected into a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) space, generated from the positional sequencing of different body parts, the overall identity of the RNAi tentacles samples seems to shift only marginally from the location of the intact tentacles (fig. S10 and dataset S3). However, when the identity map is constructed with epithelia-specific genes, we noted a clear shift from tentacle toward basal identity in all RNAi samples (Fig. 4F). All investigated conditions show an increase in the expression of basal markers, combined with a decrease of tentacle marker genes (Fig. 4G and dataset S4), with the strongest modulations not only in the tentacles of Zic4/Sp5(RNAi) animals but also in ectopic structures of Sp5(RNAi) animals. These results, which confirm the basal transformation of TBCs, suggest a key role for Zic4 as we recorded the highest level of Zic4 silencing after Zic4/Sp5(RNAi) when compared to Sp5(RNAi) or Zic4(RNAi) (fig. S11).

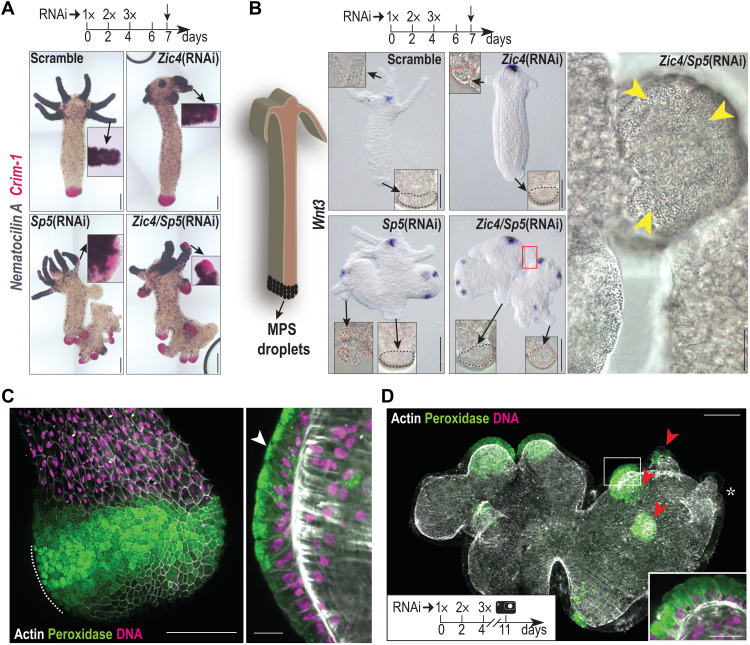

Tentacles transform into basal discs upon Zic4/Sp5(RNAi)

Using in situ hybridization (ISH) approaches, we could monitor the spatial distribution of changes in gene expression. In Zic4(RNAi), Sp5(RNAi), and Zic4/Sp5(RNAi) animals, we found 3 days after EP3 tentacle regions that express Crim-1, a gene exclusively expressed in epidermal BDCs according to the single-cell analysis (38), but no longer Nematocilin A, as well as ectopic structures along the body column that do not express Wnt3 but express Crim-1 (Fig. 5A and figs. S12 and S13). In the same conditions, we observed MPS droplets typical of BDCs in tentacle cells as well as in the structures ectopically formed along the body column when Zic4 and/or Sp5 are knocked down (Fig. 5B). This phenotype is enhanced in Zic4/Sp5(RNAi) animals that develop complete ectopic basal discs, which are morphologically and functionally indistinguishable from those of control animals (100%, n = 70) (movies S1 and S2). We could monitor the BDC identity by detecting peroxidase activity (Fig. 5C). Just 5 days after EP3, the tentacles of Zic4/Sp5(RNAi) animals display similar localized peroxidase patterns and include cells almost indistinguishable from BDCs (Fig. 5D). We observed a similar tentacle to basal disc transformation upon β-catenin silencing (fig. S14), likely because of Zic4 down-regulation. We were able to monitor this tissue transformation in two distinct Hydra strains, Hv_AEP and Hv_Basel, although with a stronger penetrance in the former (see figs. S12 and S13). For this reason, we decided to perform all subsequent experiments in Hv_AEP2 animals.

Fig. 5. Full tentacle to basal disc transformation upon Zic4/Sp5(RNAi).

(A) Nematocilin A (purple) and Crim-1 (pink) expression in Hv_AEP2 knocked down as indicated. See figs. S12 and S13. (B) Wnt3 expression and ectopic differentiation of basal tissue in Hv_Basel knocked down as indicated. See figs. S12 and S13. Black outline: original basal discs; red outline: ectopic basal tissue; red square: enlarged ectopic basal disc; yellow arrowheads: mucopolysaccharide (MPS) droplets. (C) High levels of peroxidase activity are typical for BDCs. The panel shows a Z projection of tissue surface layers, while the enlargement shows a midplane optical section along the dashline. Note the characteristic inverted triangle shape of the basal disc mucous cells with apically concentrated peroxidase granules (white arrowhead) and basally positioned nucleus. (D) Representative Zic4/Sp5(RNAi) animal 7 days after EP3. The mouth position in the original head is indicated with an asterisk. The original tentacles (red arrowheads) are now transformed to foot-like structures. Inset shows the cellular morphology in an optical section of one of them. Scale bars, 200 μm (A and B), 50 μm (C and D), and 20 μm [enlargements in (B) and (D)].

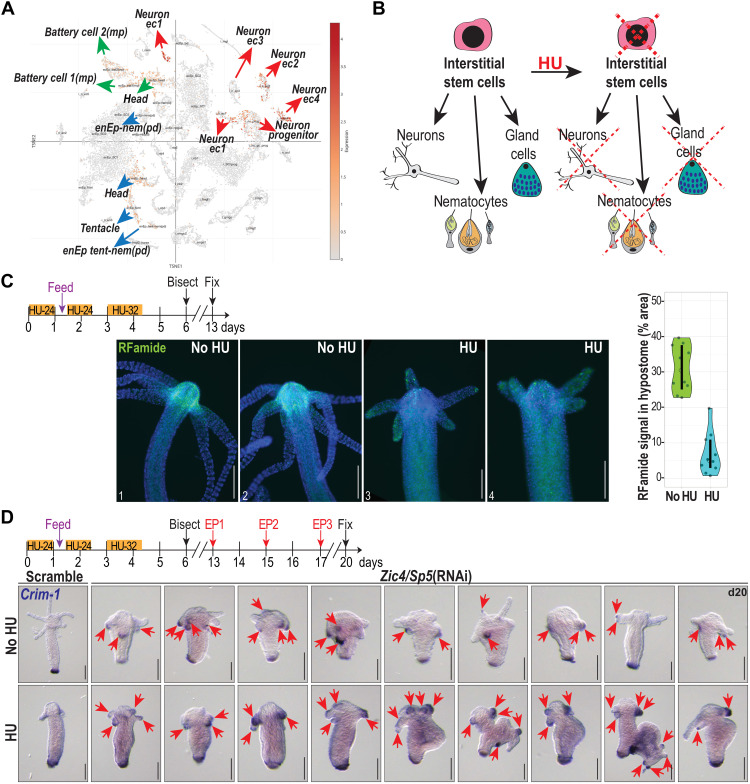

Formation of ectopic basal discs upon Zic4/Sp5(RNAi) also occurs in neuron-depleted animals

Upon examination of Zic4 expression in single-cell RNA-seq data (38), we could detect, on top of the epithelial expression, some nerve cell populations that express relatively high amounts of Zic4 (Fig. 6A). To assess the role of these Zic4-expressing cells in the observed phenotype, we eliminated them by submitting the animals to a three-course hydroxyurea (HU) treatment, a procedure that eliminates in a few days all interstitial cycling cells and progressively their progeny (Fig. 6B) (39, 40). Forty hours after the last HU exposure, animals were bisected to regenerate their head in the absence of interstitial cells. We could see a marked decrease in the number of RFamide+ nerve cells, one of the interstitial cell lineage progeny, in HU-treated animals having regenerated their head after 1 week (Fig. 6C). However, the down-regulation of Zic4 and Sp5 in these nerve-depleted animals resulted 3 days after EP3 in the transformation of tentacles in basal disc structures as evidenced with the ectopic expression of Crim-1 (Fig. 6D). Thus, the tentacle phenotype induced by a low Zic4 expression is identical in animals with and without interstitial cells, implying that the epithelial cells are primarily involved in the observed transformation.

Fig. 6. Ectopic basal disc formation upon Zic4/Sp5(RNAi) in neuron-depleted animals.

(A) t-Distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) representation of Zic4 expression (red dots) according to (38). ec, ectoderm; enEp, endodermal epithelial cell; tent, tentacle; nem, nematocyte; pd, suspected phagocytosis doublet; mp, multiplet. (B) Cartoon illustrating the elimination of ISCs with HU. (C) Hv_Basel were exposed to HU as indicated and bisected on day 6, the nervous system was detected with an anti-RFamide antibody on day 13, and the RFamide+ signal in the hypostome was quantified. Ten animals are represented as individual dots, with the median and the 95% confidence interval (CI) of the median marked as an open circle and a vertical line, respectively. Median (95% CI) for no HU and HU-treated animals are 30.54% (24.7 to 37.55%) and 5.05% (2.93 to 10.93%), respectively. (D) Intact Hv_Basel animals were exposed to HU as indicated, bisected 2 days later, electroporated (EP) with siRNAs targeting Zic4 and Sp5 on days 13, 15, and 17, and fixed on day 20 to detect the expression of Crim-1 (red arrows) by ISH. Scale bars, 200 μm.

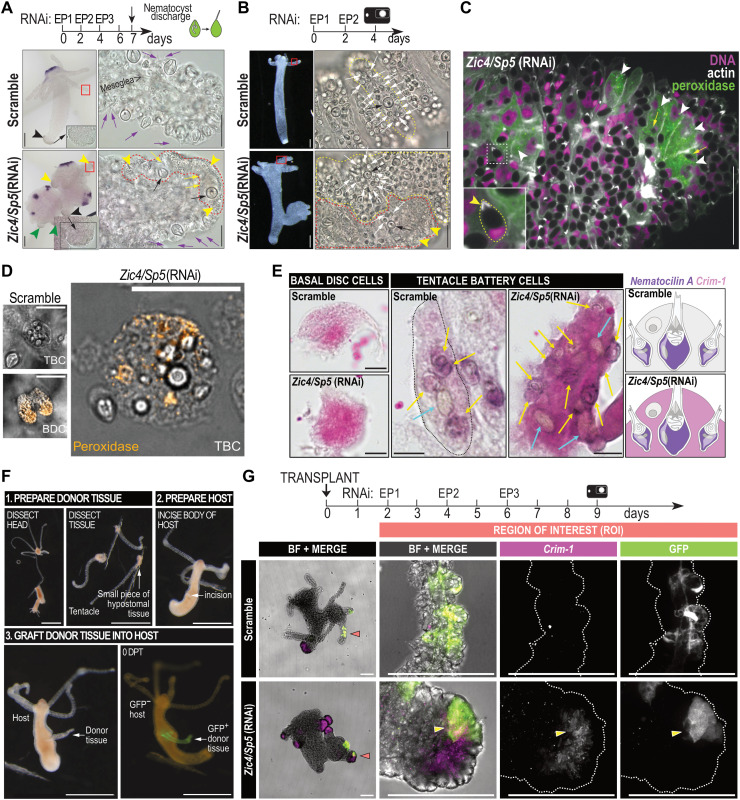

TBCs transdifferentiate into BDCs upon Zic4/Sp5(RNAi)

As a consequence, we hypothesized that the formation of ectopic basal discs in tentacles relies on the transdifferentiation of TBCs. As supporting evidence, we found TBCs in Zic4/Sp5(RNAi) animals, which exhibit a mixed identity, half tentacle, half basal disc already 2 days after EP2 with the typical granular cytoplasm of basal mucus aspect in the close vicinity of degenerating nematocytes (Fig. 7, A and B; fig. S15; and movies S3 to S7). The cytoplasm of TBCs actually contains lipid droplets with peroxidase activity, never observed in apical regions of scramble (RNAi) animals (Fig. 7C and fig. S16, A to D). Upon maceration of the Zic4/Sp5(RNAi) animals, these intermediate cells that transition from a TBC to a BDC fate are clearly visible, harboring simultaneously multiple nematocytes while expressing peroxidases normally found in BDCs (Fig. 7D and fig. S16E). Furthermore, isolated TBCs of apical tissues macerated 2 days after EP2 express the nematocyte marker Nematocilin A together with the BDC marker Crim-1 (Fig. 7E and fig. S17). These results confirm the transdifferentiation process, i.e., TBCs that still contain embedded nematocytes, while starting to express basal disc markers.

Fig. 7. Transdifferentiation of tentacle battery cells into BDCs upon Zic4/Sp5(RNAi).

(A) Wnt3 expression and TBC transformation in Hv_Basel knocked down for Zic4/Sp5 and fixed 3 days after EP3. Black arrowheads: original basal discs; green arrowheads: basal-like cells in ectopic axial structures; red squares: enlarged tentacles; red outline: portion of tentacle epidermis undergoing transformation; purple arrows: discharged nematocytes; yellow arrowheads: abundant MPS droplets in TBCs; yellow arrows: degenerating SNs; black arrows: LNs named stenoteles. (B to E) Disorganized tentacles in Zic4/Sp5(RNAi) Hv_AEP2 animals taken 2 days after EP2 (B) Zic4/Sp5(RNAi) tentacle containing both intact TBCs (yellow outline) with SNs (white arrows) and stenoteles (black arrows), and TBCs undergoing transformation (red dotted line) with few SNs and a granular cytoplasm (yellow arrowheads). (C) Zic4/Sp5(RNAi) tentacle containing TBCs with peroxidase activity (green, white arrowheads). Inset: Typical nondischarged nematocyte with moon-shape nucleus and an actin-dense V-shape structure (white) at the nematocyst apex (arrowhead). Yellow arrows point to degenerating nematocysts characterized by fuzzy outlines. (D) Peroxidase activity detected in BDCs and TBCs from dissected and trypsin-macerated tentacles of Zic4/Sp5(RNAi) animals . (E) Detection by ISH of Nematocilin A (purple) and Crim-1 (pink) expression in macerated apical regions of scramble and Zic4/Sp5(RNAi) animals. Schematic view of TBC organization adapted from (22, 24). (F) Transplantation procedure of a GFP+ tentacle into a GFP− host. (G) Detection of Crim-1 and GFP in transplanted tentacles. Scale bars, 200 μm (A and B), 50 μm (C), 25 μm [(D), and enlarged views in (A) and (B)], 10 μm (E), 1 mm (F), and 100 μm (G).

The cells in the tentacle epidermis originate from the epidermal ESCs located all along the gastric part of the body, which are being passively displaced toward the extremities. To exclude the possibility that in Zic4/Sp5(RNAi) animals the new epithelial cells that reach the tentacles directly differentiate into BDCs without first undergoing differentiation into TBCs, we performed a tracing experiment with GFP-labeled TBCs transplanted onto a nonlabeled host. We excised tentacles from animals expressing GFP in epidermal epithelial cells and transplanted them in the body column of Hydra not expressing GFP (Fig. 7F and movie S8). These chimeric animals were subsequently knocked down for Zic4 and Sp5, and 3 days after EP3, we identified several GFP+ cells, originally TBC cells from the graft, now expressing Crim-1 (Fig. 7G, fig. S18, and movies S9 to S12). This result confirms the transdifferentiation of a formerly TBC into a BDC.

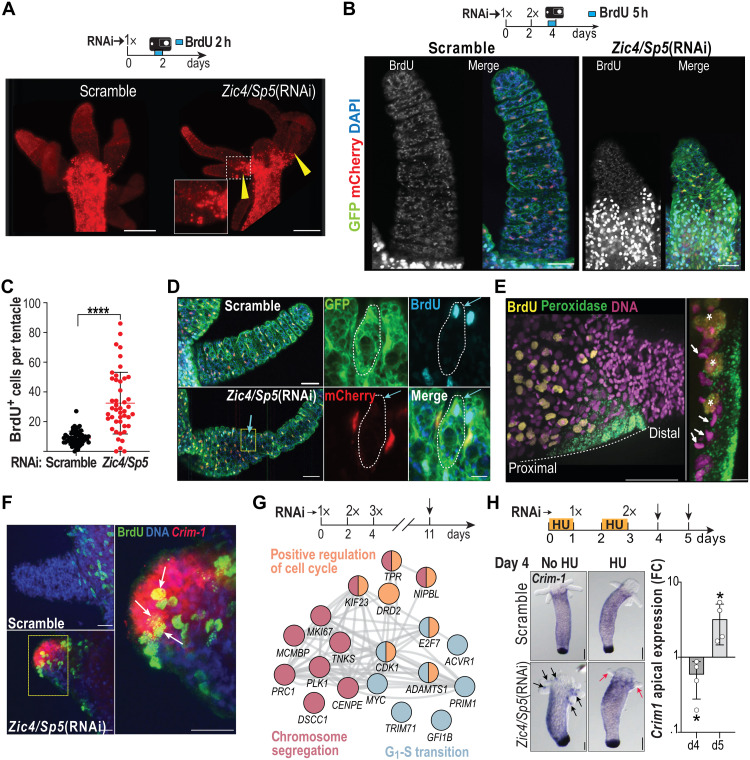

TBCs undergoing transdifferentiation reenter the cell cycle

Next, we investigated whether cells that show signs of transdifferentiation also reenter the cell cycle. We first electroporated the animals once with small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) and exposed them for 2 hours to 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) before fixation. In control animals, BrdU+ nuclei are not detected in the tentacles, while in Zic4/Sp5(RNAi) animals, BrdU+ nuclei are detected in the proximal part of the tentacles (Fig. 8A). To confirm cell cycle reentry of TBCs, we performed a 5-hour BrdU labeling of TCCS transgenic Hydra knocked down for Zic4/Sp5. Two days after EP2, we found the proximal part of tentacles populated with BrdU+ nuclei among TBCs (Fig. 8, B to D), which contain peroxidase+ droplets (Fig. 8E and fig. S19A). The typical organization of TBCs becomes disrupted in the proximal part of tentacles of Zic4/Sp5 animals, with a sharp boundary with the distal part that remains well organized (Fig. 8E). We also found BrdU+ TBCs that strongly express Crim-1 (Fig. 8F and fig. S19B). These results suggest that TBCs that undergo transdifferentiation reenter the cell cycle by activating DNA synthesis. However, we did not find any evidence of increase in mitotic activity when we analyzed the spatial distribution and the density of phosphohistone-positive nuclei (fig. S20).

Fig. 8. Transdifferentiating tentacle battery cells reenter the cell cycle.

(A to F) BrdU immunodetected in scramble or Zic4/Sp5(RNAi) animals exposed to BrdU either for 2 hours after a single electroporation (A) or for 5 hours after two electroporations (B to F). (A) BrdU+ nuclei in the proximal part of tentacles (yellow arrowheads). (B) Immunodetection of GFP, mCherry, and BrdU in tentacles of scramble and Zic4/Sp5(RNAi) transgenic TCCS animals. Distal area of tentacles at the top. Note the numerous BrdU+ epithelial cells in the proximal part of tentacles after Zic4/Sp5(RNAi). (C) Number of BrdU+/GFP+ cells in the vicinity of tentacle roots and along the tentacles as shown in (B). At least 12 animals per condition were analyzed and tentacles that were superposing partially or totally with other tentacles were excluded. Each dot represents a tentacle. ****P ≤ 0.0001. Error bars indicates SDs. (D) BrdU+ TBC (blue arrows) from a Zic4/Sp5(RNAi) animal enlarged on the right (white outlines). (E) Peroxidase+ droplets (green) in BrdU+ TBCs; right: enlarged section along the dotted line, asterisks: BrdU+ and peroxidase+ cells (yellow), white arrows: nematocyte nuclei. See also fig. S19A. (F) Crim-1+/BrdU+ tentacle cells (white arrows). See also fig. S19B. (G) Subnetwork of cell cycle genes up-regulated in tentacles across all RNAi conditions (depicted in Fig. 4F); color-coding indicates GO terms, edges genetic/physical interactions, colocalization, and/or coexpression. (H) Left: Lack of ectopic Crim-1 expression (black arrows) in tentacles of Zic4/Sp5(RNAi) animals after HU treatment (red arrows). See fig. S21. Right: Crim-1 expression levels detected by qPCR in apical regions of Zic4/Sp5(RNAi) animals 1 and 2 days after EP2. *P ≤ 0.05; ****P ≤ 0.0001. Error bars indicate SDs. Scale bars: 250 μm (A), 50 μm (B, D, and E), 25 μm (F), 200 μm (H), 10 μm enlargement in (D), and 20 μm enlargement in (E).

To collect evidence on the molecular mechanism that possibly drives cell cycle reentry, we analyzed the Gene Ontology (GO) term of the genes consistently up-regulated when Zic4 and/or Sp5 are knocked down, and we identified biological functions linked to cell cycle, i.e., G1-S transition, positive regulation of the cell cycle, and chromosome segregation (Fig. 8G and dataset S5), confirming that epithelial cell cycling is enhanced upon Zic4 and/or Sp5 silencing. To test whether cell cycling is necessary for tentacle transdifferentiation, we inhibited DNA synthesis with two pulses of HU. We observed that ectopic Crim-1 spots no longer form in tentacles of HU-treated Zic4/Sp5(RNAi) animals, at least transiently (Fig. 8H and fig. S21) , in agreement with the transient HU-induced blockade of DNA synthesis (40). Together, these data indicate that upon Zic4/Sp5 silencing, TBCs do not maintain their typical tentacle organization, reenter the cell cycle but do not divide, and fully transform within less than 7 days into BDCs.

DISCUSSION

The Hydra apical organizer relies on Wnt/β-catenin signaling as well as Sp5 and Zic4 activities

This study places the Zic4 function under the regulation of the head organizer. The results obtained in intact and regenerating animals indicate that distinct levels of Wnt/β-catenin signaling as well as Sp5 and Zic4 activity define three regions in the apical region and trigger the formation of two distinct structures, the region of the mouth opening at the tip of the hypostome and the tentacle zone at the base of the hypostome. At the tip of the hypostome, Wnt/β-catenin signaling is high, while Zic4 and Sp5 are low. In the intermediate region (the dome), Wnt/β-catenin signaling is expected to be moderate given the lower level of Wnt3 expression, the moderate level of Sp5 expression, and the low level of Zic4. Last, the tentacle zone is characterized by low Wnt/β-catenin signaling, high Sp5, and high Zic4 expression, a condition that promotes tentacle formation (Fig. 9A). This molecular definition of the head organizer actually fits the anatomical description of the Hydra head based on cellular analyses, with the inner hypostome (region surrounding the mouth opening), the outer hypostome (intermediate region), and the tentacle zone (20).

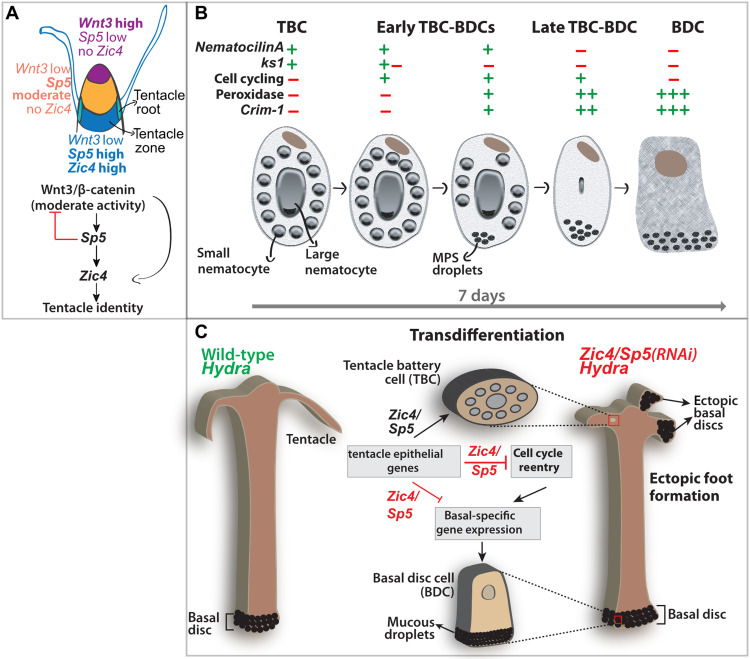

Fig. 9. Working model about the role of Zic4 and Sp5 in epithelial fate stability and tentacle formation.

(A) Zic4 acts downstream of Wnt/β-catenin signaling and Sp5 to maintain and promote epithelial tentacle identity. The direct mode of regulation of Zic4 by Wnt/β-catenin signaling needs to be verified in Hydra. (B) Proposed staging of the 7-day transdifferentiation process. (C) Upon Zic4/Sp5(RNAi), TBCs reenter the cell cycle, up-regulate basal disc–specific genes, and transdifferentiate into BDCs, resulting in the transformation of a full tentacle into a basal disc.

The Zic4 expression in the tentacle zone, the tentacle roots, and the proximal region of tentacles together with the short tentacle phenotype obtained in intact Zic4(RNAi) Hydra and the lack of tentacles in ALP-treated or regenerating Zic4(RNAi) Hydra indicate that Zic4 acts at three distinct levels: (i) in the tentacle zone, where Zic4 contributes to commit epidermal epithelial cells to the TBC fate as deduced from the loss of ks1-expressing cells upon Zic4/Sp5(RNAi); (ii) in the tentacle roots, where Zic4 is necessary to differentiate TBCs as deduced from the down-regulation of ks1 and HyAlx after Zic4(RNAi); and (iii) in the proximal region of tentacles where Zic4 is required to maintain the differentiated status of TBCs, as deduced from the loss of TBCs after Zic4/Sp5(RNAi). These spatially distinct activities of Zic4 correspond to the established three distinct phases of tentacle formation—TBC commitment in the tentacle zone, TBC differentiation in tentacle roots, and tentacle elongation (15). These Zic4 activities are supported by RNA-seq and whole-mount ISH analyses of two epithelial markers, ks1 and HyAlx, down-regulated in Zic4(RNAi) and/or Zic4/Sp5(RNAi) animals.

Zic4 actively prevents the basal disc differentiation program in tentacles

In addition to the active role of Zic4 in tentacle formation and maintenance, we also identified a suppressive role for Zic4, evidenced by the transdifferentiation of TBCs in BDCs when Zic4 is down-regulated (Fig. 9B). This process is rapid as within a week, a cluster of adjacent transdifferentiated cells in tentacles can form and behave as a fully functional basal disc, able to attach on solid substrates. We could monitor this change of cell identity in epidermal epithelial cells of tentacles that display all the features of terminally differentiated TBCs. In original tentacles of Zic4(RNAi) and Zic4/Sp5(RNAi) Hydra as well as in transplanted tentacles containing GFP+-labeled TBCs submitted to Zic4/Sp5(RNAi), we identified different types of mixed cell identities. As markers of cell fate change, we found that fully differentiated TBCs first lose expression of ks1 and HyAlx while entering the cell cycle without dividing, subsequently express Crim-1, form droplets with peroxidase activity at the apical pole, and finally rapidly organize into a compact mass of adjacent transformed cells. In parallel, nematocytes embedded in the TBCs disappear as observed histologically and confirmed by the loss of Nem-A expression, while the typical tentacle architecture becomes disorganized with the disappearance of the large extracellular space between TBCs (Fig. 9B).

These results enable us to propose a five-step scenario to switch a TBC to a BDC where the coexpression of basal markers in cells that still exhibit a typical TBC organization supports the criteria of transdifferentiation (1). We inferred from this scenario that Zic4 actively prevents the basal disc differentiation program in the proximal region of tentacles. However, we cannot exclude that a low level of Zic4 activity in the tentacle zone also leads epidermal epithelial cells that are still cycling there and committed to becoming TBCs but not yet differentiated to transform into BDCs. In addition, it should be noted that we never observed cell division among tentacle BrdU-positive cells, and we never detected mitotic activity in tentacles of Zic4(RNAi) or Zic4/Sp5(RNAi) Hydra. Therefore, we concluded that cells that reenter S phase undergo endoreplication, a process observed in developmental as well as injury and stress contexts associated with regeneration (41–43). Endoreplication allows cells to speed-up protein production without spending time dividing, therefore accelerating regeneration. Previous studies have identified transdifferentiation in Hydra, but never in epithelial cells, rather in cells that belong to the interstitial lineages, e.g., between neuronal subtypes (27), or ganglion cells converting into epidermal sensory cells (29), or zymogen gland cells transforming into granular mucous cells (28). As Zic4 is also expressed in nerve cells, it remains to be investigated whether Zic4 activity in neurons acts as a safeguard to protect their fate.

The basal disc epithelial cell fate appears as a default state in Hydra

The main finding of this study is that Zic4 acts as a master regulator that controls the choice between two epidermal cell fates: tentacle battery cells when Zic4 level is high on the one hand, and basal mucous cells when Zic4 level is low on the other. When Zic4 expression is reduced, the gene expression profile of these cells indicates not only a lower expression of TBC markers but also a concomitant up-regulation of BDC markers. Therefore, the BDC status appears as a default state of epidermal epithelial terminal differentiation in Hydra (Fig. 9C), possibly reflecting an ancestral differentiation fate of multifunctional epithelial cells in early metazoans. The fact that ectopic basal disc tissue can also develop at any place along the body column, mostly when Sp5 or Zic4 and Sp5 are knocked down, indicates that different constraints apply on the epithelial differentiation programs, with BDC differentiating in many places along the body axis and TBC differentiating only in tentacles. Several studies reported tentacle inhibition in Hydra (9, 10, 12, 13, 15); however, ectopic basal disc formation was never noticed in these contexts, suggesting that the transient genetic perturbations leading to tentacle inhibition were downstream of Zic4 and/or Sp5 activity, thus keeping active the Zic4-dependent repression of BDC differentiation.

If we assume that the default state of BDC is similarly repressed in the tentacles and in the body column, then by analogy with the blocking of this default state by TBCs in the tentacles, we can assume that the epidermal ESCs along the body column may play the same role, preventing BDC differentiation in this region, possibly via Sp5 that is expressed at high levels there. At the molecular level, we can consider two possibilities, either Zic4 directly represses the set of genes involved in basal disc differentiation (active model) or the Zic4-induced tentacle differentiation program suffices to prevent basal disc differentiation (passive model). Once a specific anti-HyZic4 antibody is made available, further ChIP-seq experiments combined with RNA-seq analysis will tell us when and where Zic4 acts as an activator or a repressor. The identification of direct Zic4 and Sp5 target genes in the apical and body column regions would help dissect this cell fate regulation. The transdifferentiation phenotype obtained in animals submitted to the double Zic4/Sp5 knockdown is enhanced and extended to the body column when compared to the single Zic4 knockdown. This result is coherent with an epistatic relationship between Sp5 and Zic4, as well as between Zic4 and HyAlx. The relationship with Notch signaling involved in tentacle formation requires further investigation (9). Furthermore, histone modifications such as H3K27 methylation appear critical when Wnt signaling is activated (44), and it would be interesting to investigate whether Zic4 activity interferes with such epigenetic mechanisms.

The Wnt/β-catenin/Sp5/Zic4 cascade might act as an evolutionarily conserved switch of epithelial cell fate

Hydra genome contains four members of the Zic family, HyZic (also named Zic1) involved in nematocyte differentiation (45) and Zic2/ZNF143 and Zic3 predominantly expressed in the gastrodermal epithelial cells, with Zic3 expressed at higher levels at the base of tentacles (46), pointing to a possible role of Zic3 in tentacle development. In the sea anemone Nematostella, several Zic genes are expressed during tentacle formation in distinct tentacle cell types (47), suggesting that the Zic4 function in tentacle maintenance and tentacle formation is shared among cnidarians. In bilaterians, zinc finger transcription factors play a crucial role in cell fate stability, acting as not only versatile multifunctional proteins, classical DNA binding proteins that regulate the expression of the ascidian Brachyury or the mammalian Oct4 and Nanog (48), but also transcriptional coactivators via their protein-protein interaction with transcription factors such as Gli, TCF, Smad, Pax, Cdx, and SRF as well as chromatin remodeling factors contributing to enhancer functions (48). In vertebrates, the human Zfp521 promotes the conversion of fibroblasts to neural stem cells ex vivo (49), and Zic proteins can inhibit the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway (50), compete with Sp transcription factors on promoter sequences (51), or associate with Geminin in cell cycle regulation (52). The question now is whether, as in Hydra, the genetic circuit involving the Wnt/β-catenin/Sp5/Zic4 cascade acts in other cnidarian or bilaterian organisms as a switch regulating epithelial cell fate.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal culture and drug treatment

All experiments were performed with strains of Hydra vulgaris (Hv) either Basel1, AEP2 (kindly provided by R. Steele), or Hm-105 (53), and the cultures were maintained in Hydra medium (HM) [1 mM NaCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 0.1 mM KCl, 0.1 mM MgSO4, and 1 mM tris (pH 7.6)]. The animals were fed two to three times per week with freshly hatched Artemia nauplii and starved for 4 days before starting the experiments. For ALP treatments, Hv_Basel were treated for 2 days with 5 μM ALP (Sigma-Aldrich) diluted in HM. All experiments were performed in accordance with ethical standards and the Swiss national regulations for the use of animals in research.

Reaggregation assays

Hm-105 animals were electroporated twice with siRNAs targeting β-catenin. One day after EP2, 100 animals were dissociated in 10 ml of dissociation medium (DM) [3.6 mM KCl, 6 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 6 mM Na-citrate, 6 mM pyruvate, 4 mM glucose, and 12.5 mM N-tris(hydroxymethyl)methyl-2-aminoethanesulfonic acid (pH 6.9)] (54, 55) and the cell suspension was centrifuged at 4°C, 1400 rpm for 45 min. The pellet was resuspended in 2 ml of DM, and the suspension was equally distributed into 1.5-ml tubes. After a second round of centrifugation at 4°C, 1400 rpm for 45 min, the tubes were laid down on the bench for 4 hours to detach the reaggregates. The reaggregates were then kept overnight at 18°C in six-well plates filled with 75% DM/HM, then for 4 hours in 50% DM/HM, and afterward transferred to HM.

Lateral transplantation experiments

A transgenic reporter line that expresses a GFP in the epidermis under the control of the actin promoter (actin::GFP kindly provided by T. Bosch) (56) was used as a host to monitor the induction of a secondary body axis. To prepare the donor tissue, Hv_AEP2 animals were electroporated three times with scramble or Zic4 siRNAs. Three days later, host animals were carefully wounded in the central body column with a scalpel. Immediately after wounding, hypostomal tissue of scramble and Zic4(RNAi) animals was excised and inserted with tweezers into these small wounds. The donor and the host tissue were allowed to heal together, and 24 hours after grafting, the animals were carefully transferred into fresh HM.

Whole-mount in situ hybridization

Whole-mount ISH with the bromochloroindolyl phosphate–nitro blue tetrazolium (BCIP-NBT) substrate was performed as recently described in detail (6). All polymerase chain reaction (PCR) products were cloned into pGEM-T-Easy (Promega) to generate riboprobes. Primer sequences are listed in table S2. For the double detection of Nematocilin A/Crim-1 and Wnt3-Crim-1, the Nematocilin A and Wnt3 riboprobes labeled with fluorescein were first developed with BCIP-NBT, while Crim-1 labeled with digoxigenin was developed in a second step with Fast Red. The BCIP-NBT reaction was stopped by washing the animals in NTMT [0.1 M NaCl, 0.1 M tris-HCl (pH 9.5), and Tween 0.1%] six times for 1 min. The samples were then incubated in 100 mM glycine (pH 2.2) supplemented with 0.1% Tween for 10 min, followed by washes in MAB-Buffer1 (1× MAB and 0.1% Tween) four times for 30 s and two times for 10 min. Next, the samples were incubated in MAB-Buffer2 (1× MAB, 10% sheep serum, and 0.1% Tween) for 1 hour, and the anti–DIG-AP antibody (1:4000; Roche) was added for overnight incubation at 4°C. On the next day, the samples were washed in MAB-Buffer2 two times for 1 min, MAB-Buffer1 two times for 1 min, and 0.1 M tris-HCl (pH 8.2) three times for 10 min and developed with Fast Red. To prepare the Fast Red solution, 1 tablet of buffer from the Sigmafast Fast Red TR/Naphthol AS-MX kit (Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in 1 ml of Milli-Q water and the Fast Red tablet was added. NaCl with a final concentration of 0.3 M was added to improve the strain. The reaction was stopped by washing the samples in 0.1 M tris-HCl (pH 8.2) three times for 1 min. The samples were postfixed in 3.7% formaldehyde diluted in Milli-Q water for 10 min, washed in Milli-Q water two times for 1 min, and mounted in Mowiol. All double ISHs were performed using Hv_AEP2.

ISH on macerates

Macerates of head and foot tissue were prepared with the maceration solution (glycerol:acetic acid:water = 1:1:13) as described in the section on immunostaining on macerates. ISH was performed as described in (57) with a few modifications. In short, samples were rehydrated through a series of EtOH, PBS-Tw [0.1% Tween 20 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)] washes (75, 50, and 25%) for 5 min each, followed by washes in PBS-Tw three times for 5 min. The samples were then incubated in heparin (10 μg/ml) for 5 min and kept in hybridization buffer [100 mM dithiothreitol, heparin (100 ng/ml), and 3× SSC] containing 2 μg/ml of each riboprobe for 4 hours at 65°C. The Nematocilin A riboprobe was labeled with digoxygenin, and the Crim-1 riboprobe was labeled with fluorescein. Next, the samples were washed with 2× SSC two times for 20 min at 65°C and kept in 2× SSC overnight at 4°C. On the next day, the samples were washed with MAB-Buffer1 two times for 10 min, MAB-Buffer2 (1× MAB, 10% sheep serum, and 0.1% Tween) for 1 hour and incubated in MAB-Buffer2 with an anti–Fluo-AP antibody (1:4000; Roche) for 4 hours. The samples were then washed with MAB-Buffer1 six times for 15 min, NTMT [0.1 M NaCl, 0.1 M tris-HCl (pH 9.5), and Tween 0.1%] for 5 min, NTMT with 1 mM levamisole two times for 5 min, and the staining solution [0.1 mM tris-HCl (pH 9.5), 0.1 mM NaCl, 7.8% polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), and 1 mM levamisole] containing BCIP-NBT was added. The colorimetric reaction was stopped by washing the samples with NTMT six times for 1 min. The Fast Red staining was performed as described above (see the previous section). The samples were postfixed in 3.7% formaldehyde diluted in Milli-Q water for 10 min, washed in Milli-Q water two times for 1 min, and mounted in Mowiol. All steps were performed at room temperature (RT) except stated otherwise.

Hybridization chain reaction RNA-FISH

The HCR RNA-FISH protocol has been adapted for Hydra based on the manufacturer’s instructions (Molecular Instruments) and provided solutions. All incubations are performed at RT unless otherwise specified. Hydra were relaxed in 2% urethane/HM for 1 min before fixation for 10 min in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA)/PBS (v/v). The fixative was washed away with PBS/0.1% Tween 20 solution (PBST) twice, for 10 min each time. Tissues were then incubated for 1 hour in a 70% ethanol/PBST (v/v) solution, followed by an incubation of 5 min in a 35% ethanol/PBST (v/v) solution at 4°C. Ethanol solutions have been cooled down at 4°C before use. Samples were washed twice for 10 min with PBST before incubation in 250 μl of HCR probe hybridization buffer, without probe, for 30 min at 37°C. Samples were then incubated with 250 μl of HCR probe hybridization buffer containing 2 pmol of ks1 hybridization probe overnight (12 to 16 hours) at 37°C. The probe was synthesized by Molecular Instruments (lot number PR0588). Hybridization probe has been washed out by five washes of 30 min in 500 μl of HCR probe wash buffer at 37°C, followed by two washes of 5 min with a 5× sodium chloride sodium citrate/0.1% Tween 20 (SSCT) solution. Signal was preamplified with 250 μl of amplification buffer for 30 min. Amplifying hairpin RNAs, provided by Molecular Instruments, were heated at 95°C for 1.5 min and allowed to cool down in the dark for 30 min. The preamplification solution was replaced by 250 μl of amplification buffer containing the two hairpins, and samples were incubated overnight (12 to 16 hours) in the dark. Excess was washed out with several washes in 5× SSCT solution in the dark: twice for 5 min, three times for 30 min, once for 30 min with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, 1 μg/ml), and once for 5 min. Samples were mounted on a slide with ProLong Gold Antifade.

Quantitative PCR

The extraction of total RNA was done with E.Z.N.A. Total RNA Kit I (Omega), and complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized using the qScript cDNA SuperMix (Quanta Biosciences). The cDNA samples were diluted to 1.6 ng/μl, and gene-specific primers were designed with Primer3. The primer efficiencies were determined on the basis of standard dilution series. All quantitative PCRs (qPCRs) were performed with the CFX96 Real-Time system (Bio-Rad), and the amplifications were done with the SYBR Select Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). The thermal cycling conditions were composed of 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 2 min, 39 cycles at 95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 65°C for 5 s. Relative gene expression levels were calculated with a model based on PCR efficiency and crossing point deviation (58). TBP was used as an internal reference gene to normalize all data.

RNA interference

RNAi was performed as previously described (6, 59) with minor modifications. In short, Hydra were briefly washed and incubated for 1 hour in Milli-Q water. Twenty animals per condition were then transferred into a 0.4-cm gap electroporation cuvette (Bio-Rad), the remaining Milli-Q water was removed, and 200 μl of siRNA solution was added, i.e., a mix of three distinct gene-specific siRNAs, 1.33 μM each in sterilized Hepes solution (pH 7). Control RNAi animals were electroporated with scramble siRNA (4 μM). For Zic4/Sp5 double knockdown experiments, Zic4 siRNAs were mixed with Sp5 siRNAs (0.7 μM of Zic4 siRNA-1, siRNA-2, and siRNA-3 + 0.7 μM of Sp5 siRNA-1, siRNA-2, and siRNA-3). The electroporation was performed with a Bio-Rad GenePulser Xcell electroporation system, and the following conditions were applied: voltage: 150 V, pulse length: 50 ms, number of pulses: 2, and pulse intervals: 0.1 s. Animals that were directly imaged after RNAi were first relaxed in 2% urethane/HM for 1 min, fixed for 2 hours at RT, and mounted in Mowiol. RNAi animals that were used for drug treatments were kept for 18 hours in HM with 5 μM ALP, followed by fixation for 2 hours at RT. For hoTG electroporations, RNAi animals were electroporated with 40 μg of hoTG plasmid (60) under the same conditions as described above. Hv_Basel were used for all experiments, except stated otherwise.

Reporter constructs

To generate the HyActin:mCherry::HyZic4-3505:EGFP (enhanced green fluorescent protein) construct (subsequently named Zic4-3505:GFP), the HyWnt3 promoter of the plasmid HyActin-RFP::HyWnt3FL-EGFP (a kind gift from T. Holstein) (61) was replaced with a 3505-bp-long HyZic4 promoter fragment that was amplified from Hm-105 genomic DNA. RFP was replaced with mCherry that was codon-optimized for Hydra expression (GenScript). To generate the HyZic4-3505:Luciferase construct (Zic4-3505:Luc), 3505 bp of the Hydra Zic4 promoter were PCR-amplified from Hm-105 genomic DNA and subcloned into a pGL3 reporter construct (a kind gift from Z. Kozmik) (62). pcDNA-Wnt3 (huWnt3) was obtained from Addgene (plasmid no. 35909) (63), pcDNA6-huLRP6-v5 (huLRP6) was kindly provided by B. Williams (64), and pFLAG-CMV-hu-β-CateninΔ45 (huΔβcat) by A. Ruiz i Altaba (65). To generate the construct encoding the TCCS as designed by Sakaue-Sawano et al. (66), we amplified from Hm-105 genomic DNA 180 bp of the N-terminal part of Hydra Geminin-like (A0A8B7E3E1_HYDVU) that contains the destruction box required for the M-G1 phase–specific APC/C ubiquitin ligase and fused it with GFP. As second sensor, we amplified from Hm-105 genomic DNA 579 bp of the N-terminal part of Hydra DNA replication factor 1 (Cdt1, XP_012559344.1) that contains the conserved PIP box (PCNA interacting domain) and fused it to mCherry. Each of the two sensors was subsequently placed under the control of the Hydra actin promoter (1437 bp) and assembled into a unique construct. To prove the functionality of this construct, we electroporated it into Hydra and found that transfected epidermal epithelial stem cells transiently coexpress cytoplasmic/nuclear GFP and nuclear mCherry.

Luciferase assays in human HEK293T cells

HEK293T cells were cultured in DMEM high glucose, 1 mM Na pyruvate, 6 mM l-glutamine, and 10% fetal bovine serum. Cells were seeded into 96-well plates (5000 cells per well) and 18 hours later transfected with an X-tremeGENE HP DNA transfection reagent (Roche). The following plasmid amounts were transfected: 1 ng of pGL4.74[hRluc/TK] (Promega), 40 ng of HyZic4-3505:Luc, 10 ng of huΔβcat, 40 ng of huLRP6, 40 ng of huWnt3, 20 ng of HySp5-420, and 20 ng of HySp5-ΔDBD. The total plasmid amount was adjusted with pTZ18R to 100 ng per well. Extracts were prepared 24 hours after transfection with the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) and transferred to a white OptiPlate-96 (PerkinElmer). Firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were immediately measured on a VICTOR X5 multilabel plate reader (PerkinElmer).

Generation of Hydra transgenic lines

Male and female polyps of the strain Hv_AEP2 were cultured together and fed three times a week, which resulted in the regular production of fertilized eggs. The Zic4-3505:GFP construct was injected into one-cell–stage embryos; out of 424 injected eggs, 71 embryos were hatched, and 1 of 71 embryos showed epidermal GFP expression in the tentacle region. Concerning the transgenic TCCS line, the plasmid encoding the TCCS was injected into one-cell–stage embryos; out of 78 injected eggs, five embryos hatched and one embryo showed epidermal epithelial Geminin-GFP/Cdt1-mCherry expression, nuclear and cytoplasmic GFP, and nuclear mCherry as expected. A stable transgenic TCCS line was derived from this embryo.

Whole-mount immunofluorescence

Intact transgenic TCCS Hydra were relaxed in 2% urethane/HM for 2 min, fixed in 4% PFA for 3 hours, dehydrated in MeOH, and kept at −20°C until processed for immunostaining. To immunodetect GFP, the animals were rehydrated with 75, 50, and 25% MeOH in Milli-Q water for 10 min, washed with PBS five times for 10 min, permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 30 min, and blocked with 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 60 min. Next, samples were incubated in rabbit anti-GFP primary antibody (1:500; Novus Biological) diluted in 2% BSA, 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 60 min at 37°C and then overnight at 4°C. The next day, the samples were washed in PBS four times for 10 min and incubated in anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG)–Alexa 488 (1:500; Thermo Fisher Scientific) diluted in PBS for 4 hours. The samples were then washed in PBS three times for 10 min, stained with DAPI (1 μg/ml; Roche) for 10 min, washed three times for 2 min in PBS, and mounted in Mowiol. All steps were performed at RT, except stated otherwise. For the phospho-histone H3 detection, Hv-AEP2 animals were processed as above, except that fixation in 4% PFA was done overnight at 4°C, and the permeabilization and blocking steps were done in 1% Triton X-100 in PBS. The mouse anti-histone H3 phospho-S10 antibody (Abcam, 14955) was diluted 1:1000 in 2% BSA, 1% Triton X-100 and subsequently detected with the anti-mouse Alexa 555 (Invitrogen, A-31570) diluted 1:500 in PBS. For actin staining, samples were incubated with 200 pM Phalloidin–Atto 565 (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS for 10 min in the dark and then washed 3× in PBST (PBS + 0.1% Tween 20). When needed, tentacles and basal regions were dissected and mounted between coverslips using a ProLong Gold Antifade mounting medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Immunostaining on macerates

Intact transgenic TCCS Hydra were decapitated, and eight heads per replicate were pooled and incubated in 30 μl of maceration solution (glycerol:acetic acid:water = 1:1:13) for 1 to 3 hours and gently pipetted up and down from time to time to dissociate the tissue. Cells were fixed in 4% PFA for 1 hour, then Tween 80 (final 0.5%) was added, and the cell suspension was spread on freshly prepared gelatin-coated slides as described in (67) with a 1.0 × 1.0 Gene Frame (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Samples on the slides were dried for 1 to 2 days, then washed in PBS three times for 10 min, and incubated in 0.5% Triton X-100 in 0.2% citrate buffer (pH 6) for 2 min at RT and then for 7 min at 70°C. After washing in PBS six times for 5 min, the cells were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 30 min, and the unspecific binding was blocked with 2% BSA and 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 60 min. To detect GFP and tubulin, a primary antibody mixture of rabbit anti-GFP (1:500; Novus Biological) and mouse anti-tubulin (1:1000; Sigma-Aldrich) was added, and the cells were first incubated for 1 hour at 37°C and then overnight at 4°C. Primary antibodies were diluted in 2% BSA and 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS. The cells were washed in PBS four times for 10 min and incubated for 4 hours in a mixture of secondary antibodies, anti-rabbit IgG–Alexa 488 (1:500; Thermo Fisher Scientific), and anti-mouse IgG–Alexa 555 (1:500; Thermo Fisher Scientific) diluted in PBS. After several fast washes in PBS, cells were counterstained with DAPI (1 μg/ml; Roche) for 10 min, washed in PBS three times for 30 s, dried, and mounted in Mowiol. All steps were performed at RT, except stated otherwise.

Detection of BrdU labeling

For all conditions of BrdU detection, we used BrdU Labeling and Detection Kit I (reference: 11296736001) from Roche with the anti-BrdU antibody diluted 1:20 in BrdU buffer. All steps were performed at RT, except stated otherwise.

Detection of BrdU labeling in whole-mount transgenic TCCS animals

Transgenic TCCS Hydra were incubated in 5 mM BrdU for 2 or 5 hours, washed five times in HM, relaxed for 2 min in 2% urethane/HM, fixed overnight at 4°C in 4% PFA, washed five times with MeOH, and stored in MeOH at −20°C for several days. For BrdU and GFP immunostaining, the samples were successively rehydrated in 75, 50, and 25% MeOH, each step for 10 min, and then washed in PBS five times for 10 min. Next, the samples were permeabilized in 1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 60 min and washed fast with PBS, and DNA was denatured with 2.5 N HCl for 30 min. After extensive washing in PBS for 20 min, the samples were incubated with a mixture of the mouse anti-BrdU and rabbit anti-GFP (1:500; Novus Biological) antibodies diluted in BrdU buffer for 1 hour at 37°C and overnight at 4°C. The next day, the samples were washed four times for 10 min in PBS, incubated in secondary anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 647 (1:500; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 (1:500; Thermo Fisher Scientific) antibodies for 4 hours, then washed in PBS four times for 10 min, counterstained with DAPI (1 μg/ml; Roche) for 10 min, washed again two times for 3 min in PBS and once with Milli-Q water, and mounted in Mowiol.

Detection of nuclear BrdU labeling in macerated tissues

Live Hv_Basel animals were incubated in 5 mM BrdU/HM (Sigma-Aldrich) for 16 hours and washed in HM two times for 5 min, and 20 body columns were macerated in 100 μl of maceration solution (as described above) for 45 min. The cell suspension was fixed in 4% PFA for 15 min, Tween 80 was added (final 1%) and spread on Epredia SuperFrost Plus Adhesion slides (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with a 1.7 × 2.8 Gene Frame (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The cells were dried for 2 days, washed in PBS three times for 10 min, treated with 2 N HCl for 30 min to denature DNA, then washed in PBS three times for 5 min, and incubated in 2% BSA/PBS for 1 hour and then with the anti-BrdU antibody overnight at 4°C in a wet chamber. On the next day, cells were washed in PBS three times for 10 min, incubated in anti–Alexa Fluor 488 antibody (1:600; Molecular Probes) for 2 hours, washed again in PBS three times for 10 min, DAPI-stained (0.2 μg/ml; Roche) for 10 min, washed in Milli-Q water two times for 5 min, and mounted in Mowiol. Similarly, transgenic TCCS Hydra first exposed to 5 mM BrdU for 5 hours were then decapitated, and six to seven heads per replicate were pooled, dissociated in 75 μl of maceration solution for 4 hours, fixed, and spread on slides as described above. After drying for 3 days, the samples were washed three times for 10 min in PBS, permeabilized for 10 min with MeOH, washed three times for 10 min in PBS, and incubated with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 15 min. After a short rinse in PBS, samples were treated with 2.5 N HCl for 30 min, washed extensively in PBS for 15 min, then incubated with a mixture of mouse anti-BrdU and rabbit anti-GFP antibodies, and detected as for whole mounts.

Detection of cell death

Intact transgenic TCCS Hydra were decapitated, and four to six heads per replicate were pooled and macerated for 3 hours in 40 μl of maceration solution as described above. The cells were fixed in 4% PFA for 1 hour, Tween 80 was added (final 0.5%), and the cell suspension was spread on freshly prepared gelatin-coated slides with a 1.5 × 1.6 cm Gene Frame (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The slides were dried for 1 to 2 days, then washed three times for 10 min in PBS, and incubated in 1% Triton X-100 in 0.2% citrate buffer (pH 6) for 2 min and at 70°C for 10 min. After washing six times for 5 min in PBS, the cells were incubated for 90 min at 37°C in a wet chamber in the dark in the TUNEL (terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase–mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate nick end labeling) mix prepared according to the supplier’s instructions (Sigma-Aldrich, reference: 11684795910). After washing three times for 10 min in PBS, cells were blocked with 2% BSA, 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 30 min, and then incubated for 60 min at 37°C in a mixture of rabbit anti-GFP (1:500; Novus Biological) and mouse anti-tubulin (1:1000; Sigma-Aldrich) antibodies diluted in 2% BSA and 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS. The cells were washed with PBS four times for 10 min and incubated for 3 hours in a mixture containing the anti-rabbit IgG coupled with Alexa 555 (1:400; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and anti-mouse IgG coupled with Alexa 647 (1:400; Thermo Fisher Scientific) secondary antibodies diluted in PBS. After several washes in PBS for 30 min, the cells were stained with DAPI (1 μg/ml; Roche) for 10 min, washed in PBS three times for 15 s, and mounted in Mowiol. All steps were performed at RT, except stated otherwise.

Detection of peroxidase activity in trypsin-macerated tissues

Intact Hv_AEP2 were relaxed in 2% urethane/HM for 1 min, fixed in 4% PFA for 4 hours, and then washed several times in PBS. Macerates were prepared by pooling 20 heads and 20 feet, respectively, and subsequently incubated in 100 μl of 0.05% trypsin-EDTA for 45 min at 37°C. Next, 100 μl of 8% PFA was added, the cell suspension was incubated for 30 min at RT, and then 20 μl of Tween 80 was added, and the cell suspension was spread on slides and dried for 2 to 3 hours. All samples were processed immediately to detect peroxidase activity. The samples were washed in PBS-Tw for 5 min and incubated in Alexa Fluor 647 or 488 tyramide solution [1× tyramide reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, references: B40958 and B40953)] and 0.03% H2O2 in PBS-Tr (0.25% Triton X-100 in PBS) for 20 min. Next, the samples were briefly washed in PBS-Tw and kept in PBS-Tw for 15 min. After one quick wash in PBS, the samples were stained with DAPI (0.2 μg/ml; Roche) for 10 min, washed with Milli-Q water for three times for 1 min, and mounted in Mowiol.

Imaging

ISH images and photos of animals that were fixed after RNAi were taken using an Olympus SZX10 microscope with an Olympus DP73 camera and a Leica DM5500 B microscope with a Leica DFC9000 GT camera. Aggregates were imaged with the Olympus SZX10 microscope. Fluorescent images were collected with the Leica SP8 confocal microscope. Spinning disc confocal microscopy was performed using an Intelligent Imaging Innovations (3i) system that incorporates a Yokogawa CSU-W1 scanner unit and a Nikon Ti inverted microscope. It is equipped with a back-illuminated Prime 95B sCMOS camera (1200 pixels × 1200 pixels, Teledyne Photometrics) and four excitation lasers (3i): 405, 488, 561, and 640 nm. Objectives used were Plan Apochromat 4×/0.2 WD 15.7 (Nikon MRD00045), Plan Apochromat 40×/0.95 OFN25 DIC M/N2 WD 0.14 (Nikon MRD00400), Plan Fluor 60×/0.85 OFN25 DIC N2 (Nikon MRH00602), and Apochromat TIRF 100×/1.49 Oil WD 0.12 (Nikon MRD01991). Microscope was controlled, and images were acquired using SlideBook 6 software (3i). For peroxidase activity detected in macerated tissues, cells were imaged using spinning disc confocal microscopy with bright-field channel (single z slice) and far red channel corresponding to peroxidase detected with Alexa Fluor 647 tyramide. All images were acquired with the same time exposure, and minimal-maximum intensities were adjusted similarly 250 to 487, maximum projection, and then merged.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 9. All statistical tests were two-tailed unpaired. For Fig. 6C, quantification was done in Fiji (68), data were visualized, and summary statistics were calculated using PlotsOfData (69).

RNA-seq analysis

Total RNA was extracted from head and body column tissue of control and Zic4 RNAi animals 1 day after EP4. Twenty Hydra were used per condition, and RNA was extracted with E.Z.N.A. Total RNA Kit I (Omega), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The RNA quality control, library preparation using TruSeqHT Stranded mRNA (Illumina), and sequencing on the Illumina HiSeq 4000 System using the 100-bp single-end read protocol were performed at the iGE3 genomics platform of the University of Geneva. The quality control of the resulting reads was done with FastQC v.0.11.5. Mapping to the H. vulgaris genome [Jussy reference—(32)] and transcript quantification were performed with the Salmon v.1.1.0 software (70). As a prefiltering step, only the transcripts with at least a sum of reads equal or above to 50 inside a same biological condition were kept. Normalization and differential expression analysis were performed with the R/Bioconductor package DESeq2 v.1.26.0 (71). The P values of the differentially expressed genes were corrected for multiple testing error with a 5% false discovery rate (FDR) using the Benjamini-Hochberg correction. Transcripts with a fold change of >1.5 and adjusted P value of <0.05 were considered as differentially expressed.

For RNA-seq of tentacle samples, original and ectopic tentacles were collected 7 days after EP3 from control, Zic4, Sp5, and Zic4/Sp5(RNAi) animals (Hm-105). The RNA was extracted with the Single Cell RNA Purification Kit (Norgen), according to the supplier’s instructions. The resulting RNA quality was assessed using a bioanalyzer or TapeStation RNA HS kit, and concentration was determined using Qubit. cDNA amplification was performed using the SmartSeq2 approach as per the original protocol (72). Full-length cDNA was processed for Illumina sequencing using Tagmentation with an in-house purified Tn5 transposase (73). One nanogram of amplified cDNA was tagmented in TAPS-DMF buffer [10 mMN-[Tris(hydroxymethyl)methyl]-3-aminopropansulfonsäure, [(2-Hydroxy-1,1-bis(hydroxymethyl)ethyl)amino]-1-propansulfonsäure-TAPS (pH 8.5), 5 mM MgCl2, and 10% N,N′-dimethylformamide (DMF)] at 55°C for 7 min. Tn5 was then stripped using SDS (0.04% final concentration), and tagmented DNA was amplified using Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase. The Illumina SmartSeq2 libraries were then demultiplexed, and reads were aligned against the Hydra vulgaris National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) genome guided by transcriptome annotation (NCBI Hydra vulgaris assembly Hydra_RP_1.0, NCBI Hydra vulgaris annotation release 102). Alignments were performed using STAR version 2.5.0 with the following command line parameters:

--outSJfilterReads Unique,

--outFilterType BySJout,

--outFilterMultimapNmax 5,

--alignSJoverhangMin 8,

--alignSJDBoverhangMin 4,

--outFilterMismatchNoverLmax 0.1,

--alignIntronMin 20,

--alignIntronMax 1000000,

--outFilterIntronMotifs RemoveNoncanonicalUnannotated,

--seedSearchStartLmax 50,

--twopassMode Basic,

--genomeChrBinNbits 12,

--genomeSAsparseD 2,

--quantMode GeneCounts.

Libraries with sizes more than 2 SDs below the median library size were discarded from all subsequent analyses. The STAR-produced gene count tables for all samples were library-normalized to obtain counts per million (CPMs) after excluding from the size factor calculation of the top five percentiles of highly expressed genes.

Marker gene selection and PCA projections

The foot- and tentacle-specific markers were selected on the basis of the average expression profiles in the positional RNA-seq data (74). Genes with low expression were first filtered out of this dataset (average CPM ≤ 200 in the body part with the lowest expression), and the remaining values were normalized for each gene to the body position with its maximum expression. Then, genes with a value of 1 in tentacles or foot were only retained in the dataset. The specificity for foot/tentacles was determined as a difference of the weighted sum of the remaining body parts to the investigated position. For example, for calculating tentacle specificity, the following formula would be used: Tspecificity = wtent.CPMtent – (whead.CPMhead + wbody1.CPMbody1 + … + wfoot.CPMfoot), where w is the weight, assigned to each position. The weighting scheme was designed to penalize distant positions more, to avoid picking genes that have similarly high expression in both foot and tentacles. Thus, the position for which the specificity was calculated (tentacles or foot) would be assigned a weight of 9 and the immediately neighboring position a weight of 2, with a +1 increment in the weight for every further neighboring position. Last, genes with a specificity score of ≥5 were retained and considered marker genes for either position.

For the common subspace projection of the positional RNA-seq dataset and dissected tentacles from RNAi animals, the expression values were first log2-transformed after smoothing (fixed pseudocount of 8) to shrink the effect sizes of lowly expressed genes. For dimensionality reduction purposes only, genes with at least a twofold change between the top and bottom fifth percentiles of gene expression and a maximum CPM expression level of >5 in the body segment samples were used. Subsequently, we obtained a unique eigenvector basis by applying PCA on the animal segment data (base R function prcomp with parameters center = TRUE, scale = FALSE). Last, the data from the dissected tissues of RNAi animals were projected back to the eigenvector basis defined from the animal segment data. To select marker genes for the epithelial and interstitial lineages, and generate the respective PCA spaces, we relied on previously published single-cell RNA-seq data (38). Specifically, we used the cluster assignment and associated gene cluster marker analysis (table S7 in the above study) and assigned as tissue origin markers genes satisfying the following criteria: an average log fold change in a cluster of interstitial/epithelial identity of more than 1.5, more than 75% within-cluster positive cells for the gene, and a difference of more than 35% in terms of difference of within cluster and out of cluster percentages of positive cells for the gene.

Genomic and phylogenetic analyses