Graphical abstract

Keywords: Cotton, GhTULP30, Drought, Seed germination, Stomatal movement

Highlights

-

•

GhTULP30 transcription in cotton was induced by drought and salt stress.

-

•

Ectopic GhTULP30 expression significantly improved yeast cell tolerance to drought and salt.

-

•

GhTULP30 overexpression increased the tolerance of Arabidopsis to drought and salt stress.

-

•

Silencing GhTULP30 affected stomatal movement and decreased tolerance to drought stress.

-

•

Protein experiments exhibited the interaction of GhTULP30 with GhSKP1B and GhXERICO.

Abstract

Introduction

Cotton is a vital industrial crop that is gradually shifting to planting in arid areas. However, tubby-like proteins (TULPs) involved in plant response to various stresses are rarely reported in cotton. The present study exhibited that GhTULP30 transcription in cotton was induced by drought stress.

Objective

The present study demonstrated the improvement of plant tolerance to drought stress by GhTULP30 through regulation of stomatal movement.

Methods

GhTULP30 response to drought and salt stress was preliminarily confirmed by qRT-PCR and yeast stress experiments. Ectopic expression in Arabidopsis and endogenous gene silencing in cotton were used to determine stomatal movement. Yeast two-hybrid and spilt-luciferase were used to screen the interacting proteins.

Results

Ectopic expression of GhTULP30 in yeast markedly improved yeast cell tolerance to salt and drought. Overexpression of GhTULP30 made Arabidopsis seeds more resistant to drought and salt stress during seed germination and increased the stomata closing speed of the plant under drought stress conditions. Silencing of GhTULP30 in cotton by virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) technology slowed down the closure speed of stomata under drought stress and decreased the length and width of the stomata. The trypan blue and diaminobenzidine staining exhibited the severity of leaf cell necrosis of GhTULP30-silenced plants. Additionally, the contents of proline, malondialdehyde, and catalase of GhTULP30-silenced plants exhibited significant variations, with obvious leaf wilting. Protein interaction experiments exhibited the interaction of GhTULP30 with GhSKP1B and GhXERICO.

Conclusion

GhTULP30 participates in plant response to drought stress. The present study provides a reference and direction for further exploration of TULP functions in cotton plants.

Introduction

Crops growing in a complex natural environment are faced with several unfavorable factors such as drought and salinity, which adversely affect crop growth and hinder sustainable agricultural development [1]. Plants subjected to environmental stress such as drought and salt resist stress damage through a series of physiological and biochemical mechanisms, for example, by changing their morphology and metabolism [2]. Drought stress leads to produce ABA, inhibits stomatal opening and decreases leaf photosynthesis, which reduce dry matter production via oxidative stress and reduction in photosynthetic characteristics [3], [4], [5]. The morpho-anatomical traits of plant leaves and the cell membranes stability have important effects on water retention [6]. Water deficit affects stomatal opening and conductance, resulting in reduced carbon import and net photosynthesis [3], [7], which ultimately lead to a substantial loss of crop productivity [8], [9]. Therefore, the genes that respond to environmental stress such as tubby-like proteins should be identified.

The tubby-like protein family, also known as TULP or TLP, was first identified in a delayed obese mouse with retinal degeneration and neurosensory hearing loss [10]{Kleyn, 1996 #4}{Kleyn, 1996 #4}{Kleyn, 1996 #4}. Subsequently, TULPs were reported in numerous plants such as rice [11], Arabidopsis [12], apple [13], and wheat [14]. Although TULPs exhibit a conserved Tub domain at the carboxyl terminus, the amino terminus varies greatly among members. The three-dimensional Tub domain structure comprises 12 antiparallel chains that form a closed β-barrel, surrounding a central hydrophobic α helix at the carboxyl terminus of the protein. The Tub domain selectively binds to a specific membrane phosphatidylinositol (PIP2) [15].

As transcription factors, TULPs are crucial in the plant response to abiotic stresses such as drought and salt. After AtTLP3 and AtTLP9 gene mutation, Arabidopsis increased tolerance to NaCl, mannitol, and abscisic acid (ABA) during seed germination and seedling growth, with the double mutant being more tolerant than the single mutant [12], [16]. CaTLP1 overexpression increased root and leaf development; net photosynthesis; biomass; and tolerance to dehydration, salinity, and oxidative stress in transgenic plants [17]. Overexpression of the apple gene MdTLP7 markedly improved NaCl and extreme temperature tolerance in Escherichia coli and Arabidopsis [18], [19], [20]. Interaction of GhTULP34 with GhSKP1A protein caused a significant reduction in the germination rate of seeds overexpressing GhTULP34 under salt stress, and inhibited root development and stomatal closure under drought stress [21]. CsTLP8 probably activates the ABA signaling pathway and inhibits seed germination and seedling growth under drought and salt stress by affecting the antioxidant enzyme activity [22]. The tomato TULP gene SlTLFP8 affects the epidermal cell size, thereby changing stomatal density, reducing water loss, and improving water efficiency [23].

TULPs are also involved in facilitating the development of male gametophytes and tissue, in response to biological stress. OsTLP2, the expression of which is induced by pathogen inoculation, binds to the PRE4 element in the promoter of OsWRKY13 to regulate the expression of OsWRKY13 and promote the defense response of rice against pathogen invasion [24]. AtTLP2 translocates from the plasma membrane to the nucleus by interacting with NF-YC3 and participates in the regulation of homogalacturonan biosynthesis in seed mucus [25]. AtTLP7 interacts with ASK1, a protein essential for male meiosis, to influence male gametophyte development [16]. Additionally, attlp6 and attlp7 mutant plants exhibited pollen abortion phenomenon to some extent [26].

Cotton is a vital industrial and economic crop because cotton fiber and oil are used as renewable energy sources. Although TULPs are involved in a few vital processes in response to abiotic stress in some plants, research on the role of these genes in cotton is still lacking. The transcriptome and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) data exhibited the remarkable upregulation of GhTULP30 expression under drought and salt stress [21]. Therefore, GhTULP30, a member of the TULPs in cotton, was selected as a candidate gene for research. Ectopic expression of GhTULP30 in yeast increased yeast tolerance to NaCl and mannitol. Under drought and salt stress conditions, Arabidopsis seeds overexpressing GhTULP30 exhibited a high germination rate and rapid closure of the plant stomata. Silencing of GhTULP30 in cotton through the virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) was found to inhibit stomatal closure and cause leaf wilting, cell necrosis, remarkable change in the expression of drought-responsive marker genes and metabolites, as well as a significant reduction in drought tolerance of silenced plants. Additionally, GhTULP30 interacted with GhSKP1B and GhXERICO at the protein level, and some stress-related genes were co-expressed with GhTULP30, indicating the positive regulatory role of GhTULP30 in response of cotton to drought stress. Thus, this study provides a theoretical reference for cotton resistance breeding.

Materials and methods

RNA extraction and qRT-PCR

The upland cotton variety CCRI36 (upland cotton with high tolerance to drought and salt stress [27], [28]) was grown in a greenhouse at a temperature of 25℃, with 16/8h of light/dark cycle. When the seedlings grew to the three-leaf stage, they were treated with 200 mM NaCl and 15% PEG6000. The control plants were treated with the corresponding volume of ddH2O. The young plant leaves were collected at 0, 1, 3, 6, and 12 h after the treatment, placed in liquid nitrogen, and refrigerated at − 80℃ for RNA extraction. The RNAprep Pure Plant kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China) was used to separate and extract RNA. The PrimerScript 1st Strand cDNA synthesis kit (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) was used to reverse transcribe RNA into cDNA. The SYBR Premix Ex Taq Kit (TaKaRa) and ABI 7500 real-time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, United States) were used for qRT-PCR analysis. The primers are listed in Table S1. The results were standardized using cotton ubiquitin 7 (UBQ7) as the internal reference gene, and the relative expression of genes was calculated using the 2-ΔΔCt method. Three biological replicates were prepared using the selected 30 plants under the same growth conditions, whereas each biological replicate was used to prepare three technical replicates.

Analysis of gene structure characteristics

TULPs of other species such as Gossypium barbadense, Gossypium arboretum, Theobroma cacao, Arabidopsis, tomato, cucumber and chickpea were obtained from the NCBI database [29]. Amino acid sequence alignment and mapping were analyzed using the default parameters of CLUSTALW [30] and ESPript 3.0 [31], respectively. The phylogenetic tree with p-distance model and 1,000 bootstrap replications was constructed using the maximum likelihood and JTT methods in MEGA 7.0 [32]. MEME and TBtools programs were used for motif analysis and drawing, respectively [33], [34]. The secondary and tertiary protein structures were predicted and analyzed using the Phyre2 database [35]. The PlantCARE database [36] was used to analyze cis-acting elements in a 2000-bp region located upstream of GhTULP30.

Yeast ectopic expression analysis

The coding sequence (CDS) of GhTULP30 in CCRI36 was cloned from mixed cDNA and subcloned between the NotI and BamHI restriction sites of pYES2 plasmid (primers listed in Table S1). Then, the pYES2-GhTULP30 and empty pYES2 plasmids were transformed into yeast (INVSc1). The empty plasmid control and positive transformants were diluted to OD600 ≈ 0.01 and transferred to the liquid SD-Ura induction medium for culture at 30℃. Then, they were cultured in the liquid SD-Ura propagation medium until OD600 ≈ 1. OD600 detection was performed using the ultraviolet (UV) spectrophotometer at 6, 22, 28, 32, and 36 h after culture. Three biological replicates were prepared for each treatment, and three technical replicates were prepared for each sample. The transformant OD600 ≈ 1 was simultaneously transferred to the solid SD-Ura induction medium and subjected to 1:10 serial dilution for four times. The SD-Ura induction medium contained stress-inducing chemicals, namely 2 mM mannitol and 300 mM NaCl.

Genetic transformation and stress treatment in Arabidopsis

The open reading frame of GhTULP30 was subcloned into the pBI121 plasmid, driven by the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter, to construct the 35S:GhTULP30 overexpression vector (Table S1). Subsequently, the Agrobacterium-mediated dipping method was used to transform Arabidopsis [37]. The transgenic-positive Arabidopsis plants were screened on 1/2 MS medium containing 50 ng/μL of kanamycin. RNA was extracted, and the GhTULP30 transcription level was determined through qRT-PCR. Wild-type and transgenic Arabidopsis seeds harvested under the same conditions were sterilized and uniformly arranged on MS media plates of the same composition containing 0, 150 mM NaCl, and 15% PEG6000. The tolerance of seed germination to NaCl and PEG6000 was determined on MS medium containing 0, 150 mM NaCl, and 15% PEG6000. Wild-type and transgenic Arabidopsis seedlings growing uniformly on a normal MS plate were transferred to the soil for normal culture for 1 month and treated with 15% PEG6000. The stomatal opening and closing were observed, and the size of the stomata was measured under a scanning electron microscope (JCM-7000). Each experiment was performed with three biological replicates, and three technical replicates were prepared for each biological replicate.

Cotton VIGS and stress treatment

The 475 bp reverse cDNA fragment of GhTULP30 was subcloned between the EcoRI and XmaI restriction sites of the pTRV plasmid (primers listed in Table S1). The four vectors, namely TRV:GhTLUP30, TRV:CLA1 (Cloroplastos alterados 1 as positive control), TRV:00, and TRVB, were transformed into the A. tumefaciens strain GV3101. The expanded positive monoclonal bacterial solution was diluted with the impregnation buffer containing 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM MES, and 200 µM acetosyringone to OD600 ≈ 1.5. The resulting solution was mixed with TRV:GhTLUP30 and TRVB, TRV:00 and TRVB, and TRV:CLA1 and TRVB at a ratio of 1:1 and injected into the fully unfolded CCRI36 cotyledon [38]. After 24 h of dark treatment, all plants were transferred to the cotton greenhouse (25℃; 16/8h light/dark photoperiod) for cultivation. TRV:GhTLUP30 and TRV:00 plants were irrigated with 15% PEG6000 when TRV:CLA1 plants appeared albino. Subsequently, the analysis of stomatal opening and closing and measurement of stomatal size were performed under a scanning electron microscope (JCM-7000). RNA was extracted from TRV:GhTLUP30 and TRV:00 plants to determine the expression level of GhTLUP30 and stress-related genes. Each experiment involved three biological replicates and three technical replicates.

Cell death analysis and substance content determination

The leaves of VIGS and control plants treated with drought stress were stained with trypan blue and diaminobenzidine (DAB) to observe cell death [39], [40]. The leaves of VIGS and control plants were collected after wilting of these plants to determine the contents of proline, malondialdehyde (MDA), and catalase (CAT). The colorimetric PRO Kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Institute of Bioengineering, China) and UV spectrophotometer were used to determine the proline content, and the wavelength was set at 520 nm. The MDA and CAT contents were determined using the MDA Assay Kit and Micro CAT Assay Kit (Solarbio, Beijing, China), respectively. Three biological and technical replicates were set up for each experiment.

Protein interaction and co-expression analysis

The CDS of GhTULP30 was constructed into the yeast interaction vector pGBKT7 (BD, between the BamHI and NotI restriction sites) for yeast screening library and point-to-point interaction verification. The interaction protein gene was constructed into the yeast interaction vector pGAKT7 (AD, between the BamHI and SacI restriction sites). The positive transformants were screened on the SD/-Trp/-Leu medium, and protein interaction was verified on the SD/-Trp/-Leu/-Ade/-His medium. GhTULP30 and the interaction gene were constructed into the nLUC vector between the SacI and SalI restriction sites and into the cLUC vector between the KpnI and SalI restriction sites. Then, the vectors were transformed into the Agrobacterium strain GV3101 (pSoup-p19). The bacterial liquid was mixed in a ratio of 1:1 and injected into the back of tobacco leaves. After 12 h of dark treatment, they were transferred to light and incubated for 48 h. The leaves were removed and coated with fluorescein (100 mm), treated in the dark for 10 min, and placed in a low-light cooled charge-coupled device imaging apparatus Lumazone_1300B (Roper Bioscience) for observation and photography. The co-expression network data for GhTULP30 were obtained and analyzed using the default parameters of the ccNET database [41].

Results

GhTULP30 structural characteristics

SITLP8, CsTLP8, MdTLP7, and CaTLP1 are involved in the drought and salt stress response; however, the underlying molecular mechanism remains unclear [17], [18], [22], [23]. GhTULP34 is vital for the plant response to NaCl and mannitol stress [21]. Additionally, GhTULP30 is a crucial member of the TULP family, and it participates in response to abiotic stress [21]. Therefore, multiple sequence alignment of the amino acid sequence of GhTULP30 and other plant TULPs was performed (Fig. 1A). GhTULP30 contains an F-Box domain at the N-terminus, indicating that GhTULP30 may function as a subunit of the SCF-type protein complex. All of TULPs contain a conserved Tub domain following the F-Box domain. Additionally, a highly conserved phosphatidylinositol 4, 5-bisphosphate (PIP2) binding site (K175/R177) is present in the Tub domain, which is crucial for the localization of TULPs on the plasma membrane [42]. Therefore, GhTULP30 may be localized on the plasma membrane.

Fig. 1.

Structural characteristics of GhTLUP30. (A) Alignment of GhTLUP30 and TULP sequences from other plants. F-box and Tub domains are marked with solid green and purple lines. Black asterisks represent conserved PIP2 binding sites. (B) Three-dimensional GhTLUP30 model. (C) Phylogenetic tree and motif analysis of GhTLUP30, AtTLPs, SlTLFP8, CsTLP8, MdTLP7, and CaTLP1. (D) Cis-acting element analysis of GhTLUP30 promoter region.

The three-dimensional model exhibited that ChTULP30 contains a conserved tubby domain comprising a barrel formed by 12 positive and antiparallel β-sheets, with an α helix in the center of the barrel (Fig. 1B). Subsequently, motif and evolutionary analyses were performed on the amino acid sequences of TULPs from different plants (Fig. 1C), which indicated that GhTULP30 and TULPs from other plants contain the same motifs. The closeness of the evolutionary relationship indicated relatively similar functions. To further understand the regulatory relationship of GhTULP30 at the transcriptional level, a 2000-bp upstream sequence of GhTULP30 was obtained, and a cis-element analysis was performed (Fig. 1D), which indicated that the GhTULP30 promoter region contains many hormones and stress-related elements such as drought response element (MBS), temperature response element (LTR), oxygenase stress element (STRE), anaerobic induction element (ARE), MeJA response elements (TGACG/CGTCA-motif), salicylic acid (SA) response element (TCA-element), and ABA response element (ABRE). Thus, GhTULP30 may respond to stresses such as drought, salt, and hormones and participate in the stress response.

GhTULP30 responds to drought and salt stress in cotton and yeast

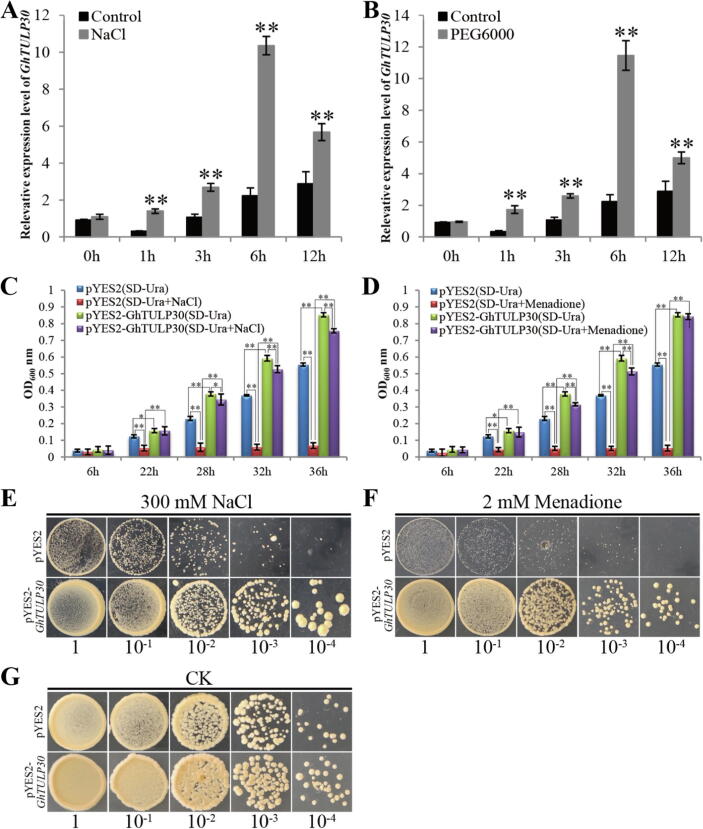

The GhTULP30 transcription levels in CCRI36 under NaCl and PEG6000 conditions were analyzed to further explore the GhTULP30 function under drought and salt stress. GhTULP30 exhibited similar transcription patterns under NaCl and PEG6000 treatments (Fig. 2A and 2B). The GhTULP30 expression levels began increasing after 1 h of treatment and were notably higher than that of the control, reaching the highest level at 6 h and then gradually decreasing, indicating that GhTULP30 expression was induced by drought and salt stress.

Fig. 2.

GhTULP30 responds to drought and salt stress in cotton and yeast. (A and B) qRT-PCR analysis of the GhTULP30 expression level after treatment of CCRI36 with NaCl and PEG6000. (C and D) Growth curves of yeast cells in liquid medium containing NaCl and mannitol after ectopic expression of GhTULP30. Values represent the mean ± SD from three biological replicates. UBQ7 gene was used as a control. (E, F and G) After ectopic expression of GhTULP30, the growth of yeast cells in a control, solid medium containing NaCl and mannitol. 1, 10-1, 10-2, 10-3 and 10-4 indicate the initial concentration of OD600 ≈ 1 yeast diluted at 1:10 for 4 times, respectively. * and ** denote p ≤ 0.05 and 0.01, respectively.

The CDS of GhTULP30 from CCRI36 of upland cotton was cloned to further explore GhTULP30 functions under drought and salt stress conditions. The expression vector pYES2-GhTULP30 was constructed and transformed into yeast (INVSc1). The yeast of pYES2-GhTULP30 was found to grow better than the control empty vector under normal culture conditions, and a significant difference in their growth pattern was reached gradually (Fig. 2C and D). Under the stress conditions of NaCl and mannitol, pYES2-GhTULP30 growth was inhibited; however, pYES2-GhTULP30 grew normally despite reaching a remarkable level compared with the normal medium. Especially under the mannitol stress condition, the pYES2-GhTULP30 growth rate at 36 h was the same as that under normal conditions (Fig. 2C and D). However, the growth of the empty plasmid control in the stress liquid medium was completely blocked. When pYES2 and pYES2-GhTULP30 yeasts were transferred to solid medium for culture, the growth rates of pYES2 and pYES2-GhTULP30 on normal solid medium were similar. However, the pYES2-GhTULP30 growth rate was markedly faster than that of pYES2 on the medium containing NaCl and mannitol. Therefore, GhTULP30 was highly resistant to NaCl and mannitol stresses in yeast.

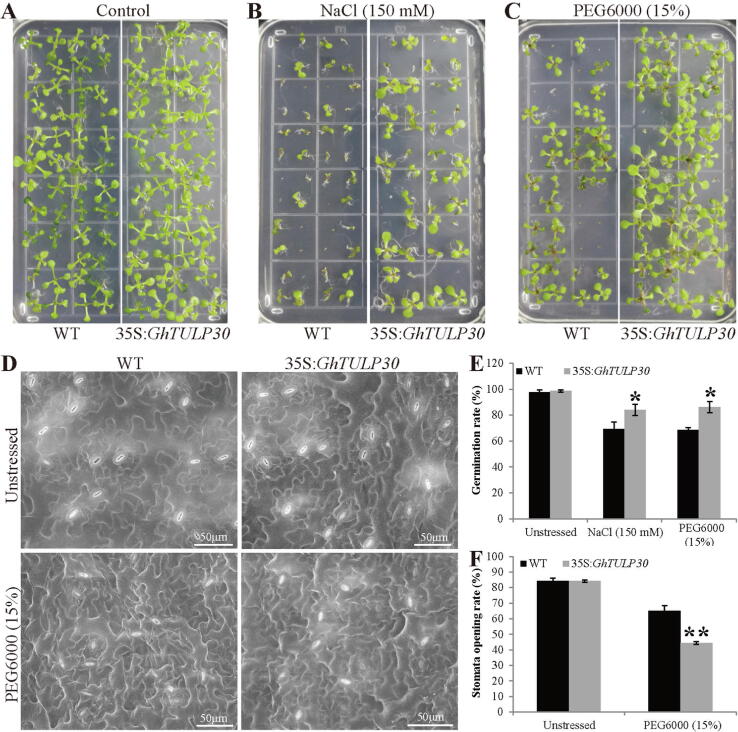

GhTULP30 affects Arabidopsis seed germination and stomatal movement

To verify the hypothesis that GhTULP30 responds to drought and salt stress, the CDS of GhTULP30 was concatenated with the 35S promoter and constructed into the pBI121 overexpression vector, transformed Arabidopsis by using the Agrobacterium-mediated method, and obtained the transgenic plants overexpressing GhTULP30 (Fig. S3). The seed germination rate of the obtained homozygous transgenic Arabidopsis offspring overexpressing GhTULP30 on the normal MS medium was similar to that of the wild type (Fig. 3A and E). The growth of the overexpression plants on the normal medium was better than that of the wild type. The seed germination of both 35S:GhTULP30 and WT were inhibited in the medium containing 150 mM NaCl. However, the germination rate of 35S:GhTULP30 was observably higher than that of the control (Fig. 3B and E). Additionally, 35S:GhTULP30 grew better than the control after germination. The germination experiment was also conducted on the medium containing 15% PEG6000, with the germination rate similar to that under NaCl stress (Fig. 3C and E). Therefore, Overexpression of GhTULP30 improved seed germination and the survival rate of Arabidopsis under NaCl and PEG6000 stress.

Fig. 3.

GhTULP30 affects seed germination and stomatal movement in Arabidopsis. (A, B and C) The germination status of 35S:GhTULP30 and WT Arabidopsis seeds on empty MS medium and MS medium containing NaCl or PEG6000. (D) The stomata of transgenic and WT Arabidopsis were opened and closed after drought stress. The red and blue circles indicate closed and open stomata, respectively. (E) The germination rate of 35S:GhTULP30 and WT Arabidopsis seeds on empty MS medium and MS medium containing NaCl or PEG6000. (F) The stomatal opening ratio of transgenic and WT Arabidopsis under drought stress condition. * and ** denote p ≤ 0.05 and 0.01, respectively.

Studies have shown that TULPs affect stomatal movement in plants [22], [23]. Therefore, the effect of GhTULP30 on stomatal opening and closing in Arabidopsis was also investigated. Under normal growth conditions, the leaf stomatal opening rate of plants overexpressing GhTULP30 grown for one month was the same as that of WT plants (Fig. 3D and F). When 15% PEG6000 was used to simulate drought treatment, many stomata on the leaves of 35S:GhTULP30 and WT plants were closed. Particularly, the 35S:GhTULP30 plants exhibited more closed stomata, reaching a remarkable level compared with the control, which indicated that GhTULP30 promoted stomatal closure and increased plant tolerance to drought stress.

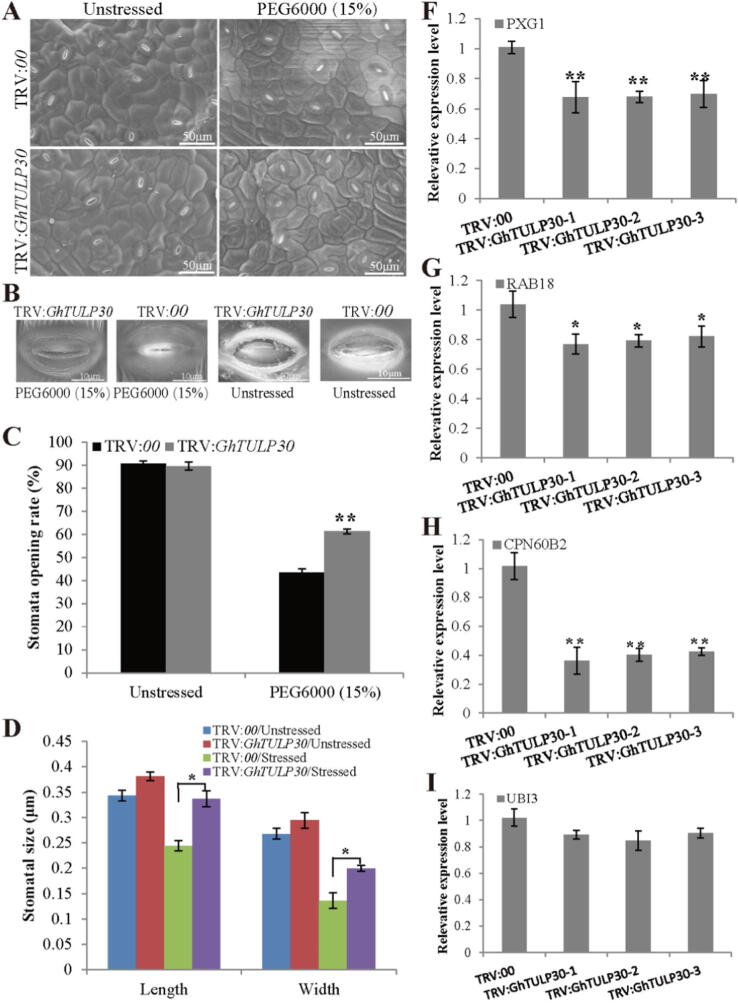

GhTULP30 silencing affects stomatal movement in cotton plants

Stomatal movement and characteristics are vital factors that affect plant response to drought stress [1]. Therefore, the stomatal characteristics and movement of cotton leaves after GhTULP30 silencing were further investigated. Under normal growth conditions, the leaf abaxial stomata of the control and TRV:GhTULP30 plants were normally opened (Fig. 4A and C). After drought treatment, stomatal closure was observed in both control and TRV:GhTULP30 plants. However, the TRV:GhTULP30 plants exhibited fewer closed leaf abaxial stomata compared with controls, and the difference was significant (Fig. 4A and C). Under normal circumstances, the measurements of the leaf abaxial stomatal size exhibited no difference in the length and width between TRV:00 and TRV:GhTULP30 plants. However, when subjected to drought stress, the length and width of the stomata of TRV:GhTULP30 plants were 1.4-fold and 1.5-fold that of TRV:00 plants, respectively, with both reaching a remarkable difference (Fig. 4B and D). Therefore, GhTULP30 silencing inhibited the closure of stomata in cotton plants.

Fig. 4.

Silencing GhTULP30 affects the movement and size of cotton stomata. (A) Stomatal closure of leaves of control and VIGS plants under drought conditions after silencing GhTULP30. The red and blue circles indicate closed and open stomata, respectively. (B) Single stomatal closure in leaves of control and VIGS plants under drought conditions after silencing GhTULP30. (C) Stomatal opening rate of control and VIGS cotton under drought stress. (D) Statistics of stomatal size of control and VIGS cotton plants under drought stress. The expression levels of stress response genes PXG1 (F), RAB18 (G), CPN60B2 (H), and UBI3 (I) in VIGS and WT plants under drought stress. * and ** denote p ≤ 0.05 and 0.01, respectively.

The expression levels of marker genes in response to abiotic stress were further determined as GhTULP30 silencing reduced the tolerance of cotton to drought stress. The PXG1, RAB18, CPN60B2 and UBI3 transcription levels in TRV:GhTULP30 and TRV:00 plants were quantitated by qRT-PCR under drought conditions (Fig. 4F-I). Thus, the PXG1, RAB18 and CPN60B2 expression levels were observably lower in TRV:GhTULP30 plants than in TRV:00 plants. Therefore, GhTULP30 might play a positive regulatory role in cotton response to drought stress.

GhTULP30 silencing reduces drought tolerance in cotton

Drought and salt stress treatment markedly increased the GhTULP30 transcription level. GhTULP30 improved the tolerance of yeast and Arabidopsis to salt and drought stress, suggesting that GhTULP30 played a positive regulatory role in the response of cotton to drought and salt stress. VIGS was used to reduce the GhTULP30 transcription level in CCRI36, thereby confirming the function of GhTULP30 in response to drought and salt stress in cotton. After the albino phenotype appeared in the true leaves of TRV:CLA1 positive control plants, the GhTLUP30 transcription level was measured in TRV:00 and TRV:GhTLUP30 plants, indicating that the GhTLUP30 expression level in VIGS-treated plants decreased by more than 70% (Fig. 5B). To simulate drought and salt stress, 15% PEG6000 was used to irrigate the control and silenced plants. After 1 week, the VIGS plants exhibited an obvious wilting phenotype, whereas the control plants demonstrated relatively better growth (Fig. 5A). Trypan blue staining was performed on true leaves of the same parts of the control and VIGS plants to determine cell mortality and the area of leaf cells after drought treatment (Fig. 5C). The blue spots on the VIGS plant leaves were denser and larger than those of the control plants, indicating higher cell death in TRV:GhTULP30 plant leaves. DAB staining was used to determine peroxidase accumulation in leaf cells of VIGS plants subjected to drought stress. The results were consistent with those of placental blue staining, and the golden yellow precipitate was more obvious on TRV:GhTULP30 plant leaves (Fig. 5C). The contents of proline, MDA, and CAT, which are markers of response to drought, were also determined. The proline and CAT contents in the VIGS plant leaves were found to be significantly reduced, whereas the MDA content was found to be observably increased (Fig. 5D, E, and F). Thus, GhTLUP30 silencing decreased the tolerance of cotton to drought stress.

Fig. 5.

Drought tolerance of cotton decreases after GhTULP30 silencing. (A) Phenotypes of drought-stressed VIGS and control cotton plants. (B) GhTULP30 expression level in VIGS and control cotton plants under drought stress. (C) Trypan blue and DAB staining of VIGS and control leaves after drought stress. (D, E and F) Proline, CAT, and MDA content of VIGS and control cotton plants under drought stress. ** denotes p ≤ 0.01.

GhTULP30 interacts with GhSKP1B and GhXERICO

GhTULP30 was used as bait to screen the TM-1 cDNA library of four-leaf-period for yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) to identify potential proteins that interact with GhTULP30. The GhTULP30 CDS was cloned into the bait vector pGBKT7, and the plasmid was transformed into Y2H Gold yeast to detect GhTULP30 auto-activation. Although the transformant of GhTULP30 grew normally on the SD/-Trp/-Leu medium, it failed to grow on the SD/-Trp/-Leu/-Ade/-His medium, indicating the absence of GhTULP30 auto-activation (Fig. 6A). Two proteins, namely GhSKP1B and GhXERICO, interacting with GhTULP30 were selected by increasing the yeast screening pressure. The CDS of the two genes was cloned, inserted into pGADT7, and transformed into Y2H Gold to verify the interaction results. Their ability to auto-activate was assessed, and they failed to survive on the selection medium SD/-Trp/-Leu/-Ade/-His (Fig. 6A). Then, BD-GhTULP30 was co-transformed into Y2H Gold with AD-GhSKP1B and AD-GhXERICO. Yeasts carrying BD-GhTULP30/AD-GhSKP1B or BD-GhTULP30/AD-GhXERICO grew well on the screening medium (SD/-Leu/-Trp/-His/-Ade) (Fig. 6A). The split-luciferase experiments confirmed the interaction of GhTULP30 with GhSKP1B and GhXERICO (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

Protein interaction and co-expression network analysis. (A) Yeast two-hybrid assay exhibiting auto-activation and interaction of GhTULP30 with GhSKB1B and GhXERICO. (B) Luciferase experiment confirmed the interaction of GhTULP30 with GhSKB1B and GhXERICO. (C) Co-expression network of GhTULP30. Nodes denote individual genes, and edges denote significant co-expression between genes. Pink lines denote positive co-expression relationship with the target protein; blue lines represent negative co-expression relationship with the target protein; and the orange line represents protein interaction with the target protein.

We also analyzed the co-expression network of GhTULP30 using the ccNET database and found a total of 35 genes co-express with GhTULP30 (Fig. 6C, Table S2). Among these genes, 6 XERICO genes were involved in plant response to salt and drought stress, as well as ABA metabolism. The co-expression network also comprised 3 SKP1B, 1 SKP1A, and 2 ASK4 genes, which specifically interact with the F-box domain and are core components of the SCF-type E3 ubiquitin ligase involved in the ABA-dependent stress signaling transduction pathway. Additionally, the NB-ARC domain-containing resistance proteins (Gh_A11G2772 and Gh_Sca004942G02) and 3 NTF3 genes encoding mitogen-activated kinases that are involved in innate immunity were identified. Mitogen-activated kinases are also key proteins affecting plant leaf development and stomatal movement [43]. More importantly, this was consistent with the results of the screened interaction proteins. These results indicated that GhTULP30 is involved in plant response to both abiotic stress, such as drought and salt, and biotic stress.

Discussion

Cotton is a vital economic crop. Upland cotton is the main cultivated species that exhibits low resistance to various stresses. Frequently occurring natural disasters such as drought, salinity, and extreme temperature severely restrict the growth and development of cotton. Therefore, the genes involved in response to adverse conditions in cotton should be identified, and specific gene functions in overcoming stress and growth and development in cotton should be studied to provide breeders with valuable genetic resources.

TULPs constitute a multi-gene family, which ars ubiquitous in plants and respond to environmental stress [44]. GhTULPs are involved in cotton response to environmental stress and tissue development. For example, under salt stress, the germination rate of Arabidopsis seeds overexpressing GhTULP34 is significantly reduced, and under mannitol stress, root development and stomatal closure are inhibited. Additionally, GhTULP34 interacts with the GhSKP1A subunit of the SCF-type complex [21]. The GhTULP30 transcription level was notably increased in response to drought and salt stress in cotton [21]. Thus, the function of GhTULP30 was further studied.

Analysis of the GhTULP30 structural characteristics revealed that GhTULP30 contains typical F-Box and Tub domains (Fig. 1) and that it is a typical plant TULP [44]. Alignment with amino acid sequences in other species exhibited that GhTULP30 contains a conserved PIP2 binding site (Fig. 1A), suggesting that GhTULP30 may be located on the plasma membrane [22], [42]. The interaction between TULP and PIP2 is reversible. When TULP interacts with the subunit Gαq of the G-protein, TULP is released by the plasma membrane and transported to the nucleus, where it acts as a transcription factor for the regulation of gene expression [15]. Nuclear Factor Y subunit C3 interacts with AtTLP2 and transports it to the nucleus [25]. Under mannitol, salt, and H2O2 stress, plasma membrane releases AtTLP3 into the nucleus [16], and CaTLP1 accumulates in the plant nucleus under osmotic stress [45]. Phylogenetic tree and motif analysis also indicated that GhTULP30 is highly similar to the TULPs present in other species, indicating that they may have similar functions. Additionally, the cis-acting element analysis exhibited that the GhTULP30 promoter region comprises several elements that respond to abiotic stress and hormones (Fig. 1C).

Relieving the reactive oxygen species toxicity is a vital mechanism of plant tolerance to stress. Reactive oxygen species regulates seed germination. Excessive release of reactive oxygen species destroys the macromolecular structures such as protein and DNA in seeds and inhibit seed germination [46]. Studies have exhibited that CaTLP1 improved the tolerance of yeast and Arabidopsis to stress by regulating antioxidant defense genes [17]. The qRT-PCR results in the present study exhibited that the GhTULP30 transcription level was markedly induced by NaCl and PEG6000 (Fig. 2). Ectopic expression of GhTULP30 in yeast notably improved yeast cell tolerance to NaCl and mannitol (Fig. 2). Overexpression of GhTULP30 in Arabidopsis observably increased the germination rate and stomatal closure rate of seeds under drought and salt stress (Fig. 3). Therefore, GhTULP30 improved the tolerance of yeast and Arabidopsis to drought and salt stress and was also related to the accumulation of reactive oxygen species.

Leaf morpho-anatomical traits and stomatal opening affect carbon input and net photosynthesis, ultimately affecting crop productivity [3], [6], [7], [8], [9]. Stomatal size and movement are important factors affecting plant drought tolerance and water use efficiency [47]. Studies have shown that many genes regulate ABA concentration, and ABA affects stomatal opening in guard cells and stomatal density [48], [49]. Meanwhile, ABA also affects stomatal movement in response to drought stress through ion channel activity [50], microtubule pattern and cell wall structure and composition [43]. The movement and size of stomata regulate the response to drought and salt stress [51], [52]. CaTLP1 regulates gene transcription in the stress resistance pathway and induces stomatal closure by interacting with the protein kinase CK1 [17]. SlTLFP8 affects the stomatal size and density of leaf epidermis through endoreduplication, thereby reducing water loss [23]. Therefore, the size of the stomata and the opening and closing state of the cotton leaf epidermis were measured after silencing GhTULP30 (Fig. 4). The silenced plants exhibited less stomatal closure, large stomata size, rapid water loss, and weak drought tolerance. Determination of the expression of stress response-related marker genes exhibited that the gene transcription level was markedly inhibited (Fig. 4), indicating that VIGS plants had reduced tolerance to drought and salt stress.

Proline participates in osmotic adjustment, which reflects stress resistance in plants [28]. The proline content in the VIGS lines decreased notably, indicating that their drought tolerance was reduced. The accumulation of reactive oxygen species increased after the plants were subjected to drought and salt stress, and CAT is the key enzyme for removing reactive oxygen species [53], [54]. When the GhTULP30 expression level was suppressed, the CAT content was observably reduced under drought conditions. Lipids are decomposed by undergoing peroxidation to produce MDA. Thus, MDA reflects the membrane damage caused to plants under stress [55]. The present study exhibited that the MDA content was significantly increased in VIGS plants. Simultaneously, staining with trypan blue and DAB exhibited the severity of leaf cell necrosis in VIGS plants (Fig. 5), indicating the crucial role of GhTULP30 in promoting cotton response to drought stress.

Protein interaction experiments exhibited the interaction of GhTULP30 with GhSKP1B and GhXERICO (Fig. 6). Studies have exhibited that ABA is a prominent regulator of seed germination and directly affects ion transport in guard cells to rapidly alter stomatal aperture in response to changing water availability and abiotic stresses such as drought [56], [57]. GhTULP30 interacts with GhSKP1B, the subunit of the SCF-type complex, and participates in the regulation of ABA-dependent pathways by SCF-type E3 ligase in response to plant drought stress [16], [58]. XERICO is a RING-H2 type zinc finger protein, and the RING domain of c-CBL has E3 ubiquitin protein ligase activity, which interacts with components in the ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation pathway (such as SCF complex), and participates in the ubiquitin degradation of ABA signaling pathway to regulate plant response to drought stress [59], [60]. GhTULP30 interacts with the XERICO protein, and the XERICO RING E3 ligase may contribute to regulating ABA level, affecting plant responses to osmosis and salt stress. Simultaneously, the co-expression network analysis exhibited the co-expression of GhTULP30 with SKP1B and XERICO, indicating its involvement in plant response to abiotic stress. Moreover, Gh_A11G2772, Gh_Sca004942G02, and NTF3, which are involved in the process of biotic stress, were also identified in the co-expression network, indicating that GhTULP30 may also participate in plant response to biotic stress.

Our previous study has exhibited that another member of the TULP family, GhTULP34, plays a negative regulatory role in the response of cotton to abiotic stresses such as drought and salt [21], which is opposite to the function of GhTULP30. Sequence alignment analysis exhibited that the amino acid sequence similarity between GhTULP30 and GhTULP34 is 67.73%. Further motif analysis indicated that GhTULP30 has one less motif than GhTULP34. Additionally, the phylogenetic tree analysis indicated that GhTULP30 and GhTULP34 share a close evolutionary relationship (Fig. S1). Further secondary and 3D model prediction analysis exhibited that the lack of motif8 in GhTULP30 may lead to the lack of a beta strand. Additionally, GhTULP30 has two more small alpha helix than GhTULP34 (Fig. S2). The GhTULP30 promoter region exhibits more cis-acting elements (such as ABRE, LTR, MBS, and Myc) in response to stress than the GhTULP34, and light-responsive elements (such as G-box and GA-motif) than GhTULP34 (Table S3). These differences may be the reasons for the differentiation of GhTULP30 and GhTULP34 in the process of executive function. This phenomenon also occurs in other plants such as Arabidopsis, cucumber, and tomato [12], [16], [21], [22], [23], and further research is required to explore the specific molecular mechanism.

Conclusion

In this study, we found that GhTULP30 expression was induced by drought and salt stress; Ectopic expression significantly improved yeast tolerance, and increased the seed germination rate and stomatal closure rate of Arabidopsis under drought and salt stress conditions; When GhTULP30 was silenced in cotton, the closure of the leaf epidermis stomata was blocked, and the leaf wilting and necrosis were obvious; GhTULP30 interact with GhSKP1B and GhXERICO. In brief, GhTULP30 acts as a molecular sensor, transcription factor, or protein subunit in response to drought stress in cotton (Fig. 7). The present study will provide references and ideas for further exploration of TULP functions.

Fig. 7.

Hypothetical GhTULP30 functional mechanism model. Plant cells receive external stress signals through various sensors. Several secondary messengers such as reactive oxygen species and Ca2+, plant hormones, and signal converters transmit these stress signals and act on related transcription factors. Transcription factors bind to the GhTULP30 promoter region to induce their expression. The GhTULP30-PIP2 complex is reversible in the G-protein signaling pathway. Under drought and salt stress, GhTULP30-PIP2 disintegrates, and GhTULP30 is transferred from the plasma membrane to the nucleus to transmit signals in response to the corresponding stress and affect plant development. The interaction between GhTULP30 and GhXERICO also affects plant response to stress and development. The SCF-type complex and ubiquitination of target proteins regulate drought and salt stress. The SCF-type complex functions within the ubiquitination reaction through combined action with the E1 and E2 enzymes. TULPs bind to SKP and targets through their F-box domain and C-terminal domain, respectively, thereby presenting the ubiquitination target. PIP2, phosphatidylinositol 4, 5-bisphosphate; Tub, Tub domain; F-box, F-box domain; TFs, transcription factors. Ub, ubiquitin. Rbx1, ring-box protein.

Compliance with Ethics Requirements

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Zhanshuai Li: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – original draft. Ji Liu: Validation, Formal analysis, Visualization. Meng Kuang: Formal analysis. Chaojun Zhang and Qifeng Ma: Resources, Data Curation. Longyu Huang and Huiying Wang: Resources, Writing – review & editing. Shuli Fan and Jun Peng: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, China (31901508), Hainan Yazhou Bay Seed Lab (B21Y10216 and B21HJ0209) and Science and Technology Innovation Project of Chinese Academy of Agricultural Science (CAAS-ASTIP-2016-ICR).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Cairo University.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2022.06.007.

Contributor Information

Shuli Fan, Email: fsl427@126.com.

Jun Peng, Email: jun_peng@126.com.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Ullah A., Sun H., Yang X., Zhang X. Drought coping strategies in cotton: increased crop per drop. Plant Biotechnol J. 2017;15(3):271–284. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bakhsh A., Hussain T. Engineering crop plants against abiotic stress: current achievements and prospects. Emir J Food Agr. 2015;27:24–39. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iqbal N., Hussain S., Raza M.A., Yang C.-Q., Safdar M.E., Brestic M., et al. Drought tolerance of soybean (Glycine max L. Merr.) by improved photosynthetic characteristics and an efficient antioxidant enzyme activities under a split-root system. Front Physiol. 2019;10 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.00786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cousson A. Two potential Ca(2+)-mobilizing processes depend on the abscisic acid concentration and growth temperature in the Arabidopsis stomatal guard cell. J Plant Physiol. 2003;160:493–501. doi: 10.1078/0176-1617-00904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pinheiro C., Chaves M.M. Photosynthesis and drought: can we make metabolic connections from available data? J Exp Bot. 2011;62:869–882. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petrov P., Petrova A., Dimitrov I., Tashev T., Olsovska K., Brestic M., et al. Relationships between leaf morpho-anatomy, water status and cell membrane stability in leaves of wheat seedlings subjected to severe soil drought. J Agron Crop Sci. 2018;204(3):219–227. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vavasseur A., Raghavendra A.S. Guard cell metabolism and CO2 sensing. New Phytol. 2005;165(3):665–682. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Awan S.A., Khan I., Rizwan M., Zhang X., Brestic M., Khan A., et al. Exogenous abscisic acid and jasmonic acid restrain polyethylene glycol-induced drought by improving the growth and antioxidative enzyme activities in pearl millet. Physiol Plant. 2021;172(2):809–819. doi: 10.1111/ppl.13247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang D., Tong J., He X., Xu Z., Xu L., Wei P., et al. A novel soybean intrinsic protein gene, GmTIP2;3, involved in responding to osmotic stress. Front Plant Sci. 2015;6:1237. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.01237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kleyn P.W., Fan W., Kovats S.G., Lee J.J., Pulido J.C., Wu Y.e., et al. Identification and characterization of the mouse obesity gene tubby: a member of a novel gene family. Cell. 1996;85(2):281–290. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang Z., Zhou Y., Wang X., Gu S., Yu J., Liang G., et al. Genomewide comparative phylogenetic and molecular evolutionary analysis of tubby-like protein family in Arabidopsis, rice, and poplar. Genomics. 2008;92(4):246–253. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lai C.-P., Lee C.-L., Chen P.-H., Wu S.-H., Yang C.-C., Shaw J.-F. Molecular analyses of the Arabidopsis TUBBY-like protein gene family. Plant Physiol. 2004;134:1586–1597. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.037820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu J.-N., Xing S.-S., Zhang Z.-R., Chen X.-S., Wang X.-Y. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the tubby-like protein family in the Malus domestica genome. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1693–1704. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hong M.J., Kim D.Y., Seo Y.W. Interactions between wheat Tubby-like and SKP1-like proteins. Genes Genet Syst. 2015;90(5):293–304. doi: 10.1266/ggs.14-00084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Santagata S., Boggon T.J., Baird C.L., Gomez C.A., Zhao J., Shan W.S., et al. G-protein signaling through tubby proteins. Science. 2001;292(5524):2041–2050. doi: 10.1126/science.1061233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bao Y., Song W.-M., Jin Y.-L., Jiang C.-M., Yang Y., Li B., et al. Characterization of Arabidopsis Tubby-like proteins and redundant function of AtTLP3 and AtTLP9 in plant response to ABA and osmotic stress. Plant Mol Biol. 2014;86(4-5):471–483. doi: 10.1007/s11103-014-0241-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wardhan V., Pandey A., Chakraborty S., Chakraborty N. Chickpea transcription factor CaTLP1 interacts with protein kinases, modulates ROS accumulation and promotes ABA-mediated stomatal closure. Sci Rep. 2016;6:38121. doi: 10.1038/srep38121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu J., Xing S., Sun Q., Zhan C., Liu X., Zhang S., et al. The expression of a tubby-like protein from Malus domestica (MdTLP7) enhances abiotic stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. BMC Plant Biol. 2019;19:60–67. doi: 10.1186/s12870-019-1662-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Du F., Xu J.-N., Li D., Wang X.-Y. The identification of novel and differentially expressed apple-tree genes under low-temperature stress using high-throughput Illumina sequencing. Mol Biol Rep. 2015;42(3):569–580. doi: 10.1007/s11033-014-3802-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Du F., Xu J.-N., Zhan C.-Y., Yu Z.-B., Wang X.-Y. An obesity-like gene MdTLP7 from apple (Malus × domestica) enhances abiotic stress tolerance. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;445(2):394–397. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Z., Wang X., Cao X., Chen B., Ma C., Lv J., et al. GhTULP34, a member of tubby-like proteins, interacts with GhSKP1A to negatively regulate plant osmotic stress. Genomics. 2021;113(1):462–474. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2020.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li S., Wang Z., Wang F., Lv H., Cao M., Zhang N., et al. A tubby-like protein CsTLP8 acts in the ABA signaling pathway and negatively regulates osmotic stresses tolerance during seed germination. BMC Plant Biol. 2021;21:340. doi: 10.1186/s12870-021-03126-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li S., Zhang J., Liu L., Wang Z., Li Y., Guo L., et al. SlTLFP8 reduces water loss to improve water-use efficiency by modulating cell size and stomatal density via endoreduplication. Plant Cell Environ. 2020;43:2666–2679. doi: 10.1111/pce.13867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cai M., Qiu D., Yuan T., Ding X., Li H., Duan L., et al. Identification of novel pathogen-responsive cis-elements and their binding proteins in the promoter of OsWRKY13, a gene regulating rice disease resistance. Plant Cell Environ. 2008;31:86–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2007.01739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang M., Xu Z., Ahmed R.I., Wang Y., Hu R., Zhou G., et al. Tubby-like Protein 2 regulates homogalacturonan biosynthesis in Arabidopsis seed coat mucilage. Plant Mol Biol. 2019;99(4-5):421–436. doi: 10.1007/s11103-019-00827-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reňák D., Dupl’áková N., Honys D. Wide-scale screening of T-DNA lines for transcription factor genes affecting male gametophyte development in Arabidopsis. Sex Plant Reprod. 2012;25(1):39–60. doi: 10.1007/s00497-011-0178-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gu L., Ma Q., Zhang C., Wang C., Wei H., Wang H., et al. The cotton GhWRKY91 transcription factor mediates leaf senescence and responses to drought stress in transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana. Front Plant Sci. 2019;10:1352. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.01352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Z., Wang X., Cui Y., Qiao K., Zhu L., Fan S., et al. Comprehensive genome-wide analysis of thaumatin-like gene family in four cotton species and functional identification of GhTLP19 involved in regulating tolerance to Verticillium dahlia and drought. Front Plant Sci. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.575015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ron E., Michael D., Lash A.E. Gene Expression Omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002:207–210. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thompson J.D., Higgins D.G., Gibson T.J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22(22):4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robert X., Gouet P. Deciphering key features in protein structures with the new ENDscript server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:W320–W324. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kumar S., Stecher G., Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen C., Chen H., Zhang Y., Thomas H.R., Frank M.H., He Y., et al. TBtools: an integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol Plant. 2020;13(8):1194–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2020.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bailey T.L., Williams N., Misleh C., Li W.W. MEME: discovering and analyzing DNA and protein sequence motifs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(Web Server):W369–W373. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kelley L.A., Mezulis S., Yates C.M., Wass M.N., Sternberg M.J.E. The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis. Nat Protoc. 2015;10(6):845–858. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rombauts S., Dehais P., Van Montagu M., Rouze P. PlantCARE, a plant cis-acting regulatory element database. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27(1):295–296. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.1.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clough S., Bent A. Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1998;16:735–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hu Q., Min L., Yang X., Jin S., Zhang L., Li Y., et al. Laccase GhLac1 modulates broad-spectrum biotic stress tolerance via manipulating phenylpropanoid pathway and jasmonic acid synthesis. Plant Physiol. 2018;176(2):1808–1823. doi: 10.1104/pp.17.01628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Choi D.S., Hwang B.K. Proteomics and functional analyses of pepper abscisic acid-responsive 1 (ABR1), which is involved in cell death and defense signaling. Plant Cell. 2011;23:823–842. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.082081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kumar V., Parkhi V., Kenerley C.M., Rathore K.S. Defense-related gene expression and enzyme activities in transgenic cotton plants expressing an endochitinase gene from Trichoderma virens in response to interaction with Rhizoctonia solani. Planta. 2009;230(2):277–291. doi: 10.1007/s00425-009-0937-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.You Q.i., Xu W., Zhang K., Zhang L., Yi X., Yao D., et al. ccNET: Database of co-expression networks with functional modules for diploid and polyploid Gossypium. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(D1):D1090–D1099. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reitz M.U., Bissue J.K., Zocher K., Attard A., Hückelhoven R., Becker K., et al. The subcellular localization of Tubby-like proteins and participation in stress signaling and root colonization by the mutualist Piriformospora indica. Plant Physiol. 2012;160(1):349–364. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.201319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Witoń D., Sujkowska-Rybkowska M., Dąbrowska-Bronk J., Czarnocka W., Bernacki M., Szechyńska-Hebda M., et al. MITOGEN-ACTIVATED PROTEIN KINASE 4 impacts leaf development, temperature, and stomatal movement in hybrid aspen. Plant Physiol. 2021;186(4):2190–2204. doi: 10.1093/plphys/kiab186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang M., Xu Z., Kong Y. The tubby-like proteins kingdom in animals and plants. Gene. 2018;642:16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2017.10.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wardhan V., Jahan K., Gupta S., Chennareddy S., Datta A., Chakraborty S., et al. Overexpression of CaTLP1, a putative transcription factor in chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.), promotes stress tolerance. Plant Mol Biol. 2012;79(4-5):479–493. doi: 10.1007/s11103-012-9925-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ma Z., Bykova N.V., Igamberdiev A.U., Biology D.O., Newfoundland M.U.o., P.F. Centre, et al. Cell signaling mechanisms and metabolic regulation of germination and dormancy in barley seeds. Crop J. 2017;5:459–477. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Suhita D., Raghavendra A., Kwak J., Vavasseur A. Cytoplasmic alkalization precedes reactive oxygen species production during methyl jasmonate- and abscisic acid-induced stomatal closure. Plant Physiol. 2004;134:1536–1545. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.032250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shimizu T., Kanno Y., Suzuki H., Watanabe S., Seo M. Arabidopsis NPF4.6 and NPF5.1 control leaf stomatal aperture by regulating abscisic acid transport. Genes. 2021;12:885. doi: 10.3390/genes12060885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhao P.-X., Miao Z.-Q., Zhang J., Chen S.-Y., Liu Q.-Q., Xiang C.-B., et al. Arabidopsis MADS-box factor AGL16 negatively regulates drought resistance via stomatal density and stomatal movement. J Exp Bot. 2020;71(19):6092–6106. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eraa303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liang C., Li C., Wu J., Zhao M., Chen D., Liu C., et al. SORTING NEXIN2 proteins mediate stomatal movement and response to drought stress by modulating trafficking and protein levels of the ABA exporter ABCG25. Plant J. 2022 doi: 10.1111/tpj.15758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guo X.-Y., Wang Y., Zhao P.-X., Xu P., Yu G.-H., Zhang L.-Y., et al. AtEDT1/HDG11 regulates stomatal density and water-use efficiency via ERECTA and E2Fa. New Phytol. 2019;223(3):1478–1488. doi: 10.1111/nph.15861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Qi S., Lin Q., Feng X., Han H., Liu J., Zhang L., et al. IDD16 negatively regulates stomatal initiation via trans-repression of SPCH in Arabidopsis. Plant Biotechnol J. 2019;17:1446–1457. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Krasensky J., Jonak C. Drought, salt, and temperature stress-induced metabolic rearrangements and regulatory networks. J Exp Bot. 2012;63(4):1593–1608. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Laloi C., Apel K., Danon A. Reactive oxygen signalling: the latest news. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2004;7(3):323–328. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yoshimura K., Miyao K., Gaber A., Takeda T., Kanaboshi H., Miyasaka H., et al. Enhancement of stress tolerance in transgenic tobacco plants overexpressing Chlamydomonas glutathione peroxidase in chloroplasts or cytosol. Plant J. 2004;37(1):21–33. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Roelfsema M., Levchenko V., Hedrich R. ABA depolarizes guard cells in intact plants, through a transient activation of R- and S-type anion channels. Plant J. 2004;37:578–588. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313x.2003.01985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mega R., Abe F., Kim J.-S., Tsuboi Y., Tanaka K., Kobayashi H., et al. Tuning water-use efficiency and drought tolerance in wheat using abscisic acid receptors. Nat Plants. 2019;5(2):153–159. doi: 10.1038/s41477-019-0361-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stone S.L., Callis J. Ubiquitin ligases mediate growth and development by promoting protein death. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2007;10(6):624–632. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ko J., Yang S., Han K. Upregulation of an Arabidopsis RING-H2 gene, XERICO, confers drought tolerance through increased abscisic acid biosynthesis. Plant J. 2006;47:343–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dreher K., Callis J. Ubiquitin, hormones and biotic stress in plants. Ann Bot. 2007;99(5):787–822. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcl255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.