Abstract

Plants are unavoidably exposed to a range of environmental stress factors throughout their life. In addition to the external environmental factors, the production of reactive oxygen species as a product of the cellular metabolic process often causes DNA damage and thus affects genome stability. Homologous recombination (HR) is an essential mechanism used for DNA damage repair that helps to maintain genome integrity. Here we report that the recombinase, PpRecA2, a bacterial RecA homolog from moss Physcomitrium patens can partially complement the function of Escherichia coli RecA in the bacterial system. Transcript analysis showed induced expression of PpRecA2 upon experiencing DNA damaging stressors indicating its involvement in DNA damage sensing and repair mechanism. Over-expressing the chloroplast localizing PpRecA2 confers protection to the chloroplast genome against DNA damage by enhancing the chloroplastic HR frequency in transgenic tobacco plants. Although it fails to protect against nuclear DNA damage when engineered for nuclear localization due to the non-availability of interacting partners. Our results indicate that the chloroplastic HR repair mechanism differs from the nucleus, where chloroplastic HR involves RecA as a key player that resembles the bacterial system.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12298-022-01264-7.

Keywords: Physcomitrium patens, DNA damage, Chloroplastic RecA, Homologous recombination

Introduction

Plants being sessile are exposed to various kinds of genotoxic stresses among which environmental factors like UV-B radiation, excessive soil salinity, heavy metal contamination, chilling, and drought all lead to DNA damage. Additionally, DNA damage by intermediate products like alkylating agents, reactive oxygen species, etc. is of constant occurrence (Roy 2014; Li et al. 2002). Double-stranded DNA breaks (DSDBs) form the majority of the DNA damage occurring in plants. Rapid detection followed by the repair of these DSDBs is pivotal for plant growth and survival (Puchta 2005). Repair of DSDBs is accomplished by the fundamental pathways of homologous recombination (HR) and non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ).

HR is accomplished through an evolutionarily conserved enzymatic pathway (Barbat et al. 2014). DSDBs are located by recombinases, which then execute the task of searching for sequence similarity and strand exchange between the two DNA molecules (Prigge and Bezanilla 2010). RecA recombinase protein functions have been thoroughly studied in bacteria however there are still several unanswered questions about the RecA protein occurring in plants. The RecA protein occurring in plants is targeted to the mitochondria and/or the chloroplasts in contrast to their eukaryotic counterpart, RAD51 protein which is targeted to the nucleus (Rowan et al. 2010; Odahara et al. 2009).

Chloroplast, as well as mitochondrial DNA (cp and mt DNA, respectively), is exposed to a considerable amount of DNA damaging factors like reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the form of superoxide (O2·), the hydroxyl radical (OH·), and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) (Scarpeci et al. 2008). Therefore a stringent DNA repair system should be present in these organelles to maintain genome integrity. Mitochondria and Chloroplast targeted RecA has been reported in several plants (Lin et al. 2006). RecA dependent recombination pathway is present in the chloroplasts of unicellular green algae, Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (Cerutti et al. 1995). Arabidopsis thaliana encodes five different homologs of the bacterial RecA protein. Mutant for one of the genes (AtRECA1) showed variegated leaves with a reduced amount of cpDNA and higher levels of ssDNA in the chloroplast (Rowan et al. 2010). Pea chloroplast lysate consisted of a protein cross-reacting with Escherichia coli RecA antibody (Cerutti et al. 1993) and showed the presence of strand transfer activity similar to that of bacterial RecA (Cerutti and Jagendorf 1993). The moss Physcomitrium patens nuclear genome encodes two types of RecA proteins PpRecA1 and PpRecA2, which are directed to mitochondria and chloroplast, respectively (Odahara et al. 2007; Inouye et al. 2008).

In the current study, we report that the PpRecA2 protein from Physcomitrium patens retained similarity with its bacterial counterpart and could partially complement RecA mutations in E. coli. The PpRecA2 transcript showed several-fold change under DNA-damaging conditions. The PpRecA2 transcripts showed a rhythmic change under continuous light (L) or dark (D) conditions, though the fold change was higher under light conditions. Additionally, the PpRecA2 protein functions specifically in the chloroplast, aiding the recombination reaction. However, the same protein could not cater to the recombination mechanism when targeted to the nucleus as analyzed under an in vitro homologous recombination (IVHR) experiment.

Material and methods

Plant material

Physcomitrium patens (Hedw.) Bruch & Schimp. strain Gransden was grown on BCDAT-agar medium with the culture condition of 22 °C temperature, 70% relative humidity, and 16 h light regime with a photon flux of 100 µmol/m2/s. Protonemal cultures were grown under a similar condition on cellophane-overlaid BCDAT plates.

Bioinformatic analysis of PpRecA2 from Physcomitrium patens

The amino acid sequence of PpRecA2 was obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (AB284535.1). The corresponding protein sequence (PpRecA2), and its N-terminal 80 amino acid chloroplast localization signal deletion mutant (PpRecA2∆CLS) sequence, were used as targets to search for templates against the SWISS-MODEL template library (SMTL). The target sequences were searched with BLAST and HHBlits against the primary amino acid sequences contained in the SMTL. 3-dimensional (3D) models of PpRecA2 and PpRecA2∆CLS, were built using SWISS-MODEL based on Escherichia coli RecA protein (4twz.1.A) and Thermotoga maritima RecA protein (3hr8.1), as templates from the SMTL, Version 2022-10-13, using a standard procedure, respectively. The global and per-residue model quality was assessed for both models using the QMEANDisCo (qualitative model energy analysis-distance constraints) scoring function. QMEANDisCo gives an estimate of the quality of a 3D protein structure model when an experimental reference structure is absent (Studer et al. 2020). In addition, the quality of the predicted structures of PpRecA2 and PpRecA2∆CLS was also assessed by generating the corresponding Ramachandran plots, using the SWISS-MODEL structure assessment tool. A structure is supposed to be of good quality when it contains all the set of torsional angles, ϕ (phi) and ψ (psi) in the allowed region of the Ramachandran plot (Ramachandran et al. 1963).

The cis-elements present upstream (2 kb from the start codon) of the PpRecA2 gene were analyzed using PLACE (http://www.dna.affrc.go.jp/PLACE/) (Higo et al. 1999). This might help to predict the related functions of the protein under different conditions.

Phylogenetic analysis

RecA protein sequences were obtained from the GenBank database, and the phylogenetic analysis was carried out with MEGA 11 (molecular evolutionary genetics analysis) version 11.0.13. The evolutionary history was inferred using the Maximum Parsimony method. Bootstrap analysis for 500 replicates was done to provide confidence estimates for the associated taxa clustering together. RecA proteins used in the analysis were as follows: PpRecA2 (this study, AB284535.1); Anabaena variabilis (M29680); Synechococcus sp. PCC7002 (M29495); Bacillus subtilis (P16971); Escherichia coli (X55552); Chlamydia trachomatis (A0A655MWE0); Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (AB048829); Marchantia polymorpha (A0A2R6X3Q3); Arabidopsis thaliana (L15229); Nicotiana tabacum (A0A1S4BNI8); Oryza sativa (Q6ASS3); and Sorghum bicolor (XP_002466766.1).

Stress treatment and real-time quantitative PCR expression analysis

Two weeks old Physcomitrium patens protonema was subjected to different concentrations (0.5, 1, 1.5 µg/ml) of DNA damaging agent Mitomycin C (MMC), and samples were collected from each set at different time points (0, 6, 12, 24 h). The protonemal tissue was also subjected to oxidative stress using 100 mM Methyl viologen (MV) and 100 mM H2O2, separately for 6 h each. Total RNA was isolated from 50 mg of protonemal tissue using a Qiagen plant RNA kit. First-strand cDNA was prepared using 1 µg of isolated total RNA using the GoScript Reverse Transcriptase cDNA synthesis kit (Promega). Real-time PCR was carried out using gene-specific primers (supplementary Table S1) using the Clathrin adapter complex subunit (CAP-50) as an internal control.

Light-dependent oscillation in PpRecA2 transcript level

For checking the expression profile of the PpRecA2 protein to circadian rhythm, 7-day-old protonema tissue was incubated in complete darkness for 48 h followed by incubation in continuous light (L) for 24 h in one set. In the second set, 7-day-old protonema tissue was incubated in presence of light for 48 h followed by incubation in the continuous dark (D) for 24 h. A similar transcript accumulation study was done for PpRecA2 in transgenic tobacco plants, where the CDS was under a constitutive promoter. 100 mg of tissue was collected at 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, and 24 h of L and D treatment, from all the sets of P. patens and at 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, 18 and 24 h of L treatment from all the sets of transgenic tobacco. All the sets were checked for PpRecA2 transcript level accumulation.

Cloning, expression, purification, and immunodetection of PpRecA2 sequences

The coding sequence of the PpRecA2 protein was amplified using gene-specific primers (supplementary table S1). 1383 bp PCR product was cloned in pGEMT-Easy vector (Promega, USA) followed by sequencing. For bacterial expression, PpRecA2 CDS was sub-cloned into pET19b expression vector at the NdeI site and transformed into bacterial host strain, E. coli Rossetta (DE3) pLysS. Protein expression was induced by adding 1 mM isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) to culture grown to the optical density value of 0.6 at 600 nm for 4 h at 30 °C. The harvested cell pellet was resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM β-ME, and 1 mM PMSF) and sonicated using an ultrasonic processor UP100H (Hielscher, Germany). The lysate was centrifuged at 9000g for 10 min at 4 °C. The pellet fraction containing overexpressed PpRecA2 protein was solubilized using 8 M urea for 2 h at room temperature followed by removal of urea by step dialysis. His-tagged PpRecA2 protein was affinity purified using Ni–NTA column (Qiagen, Germany) and analyzed in 12% SDS-PAGE. Western blot analysis was carried out using rabbit anti-His primary antibody.

Generation of the construct for nuclear targeting of PpRecA2 protein

The nuclear localization signal sequence (NLS) from the large T antigen of SV-40 (simian virus 40), 5′ CCC AAA AAG AAG AGA AAG GTA 3′, was fused at the N-terminal of the PpRecA2 sequence (Dingwall and Laskey 1991). The fusion of nucleotide sequence resulted in a fusion protein with PKKKRKV at the N-terminal end of the PpRecA2 protein. Since the PpRecA2 protein had a chloroplast localization signal at the N-terminal end, 240 bp (80 amino acids) were deleted to generate the NLS-PpRecA2 protein.

The NLS-PpRecA2 was also sub-cloned into expression vector pET20b at SacI-XhoI site and transformed into bacterial host strain, E. coli Rossetta (DE3) pLysS. The expression, purification, and immunodetection were the same as described earlier.

Escherichia coli RecA complementation assay

Escherichia coli RecA deficient strain, JM109 cells bearing pET19b, PpRecA2-pET19b, and NLS-PpRecA2-pET20b plasmids separately along with E. coli strain Rossetta (DE3) pLysS, were cultured up to OD600 of 0.4 in LB medium. IPTG was added to a final concentration of 1 mM and the cultures were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min for protein induction. Following this, the cells were treated with different concentrations (0.5, 1.0, 1.5, and 2.0 µM) of MMC at 37 °C for 1 h to 5 h. The cells were harvested at 1-h time intervals, washed, and spread on LB agar plates supplemented with ampicillin and incubated at 37 °C overnight. The colony-forming units were counted and plotted.

Generation and analysis of transgenic tobacco plants

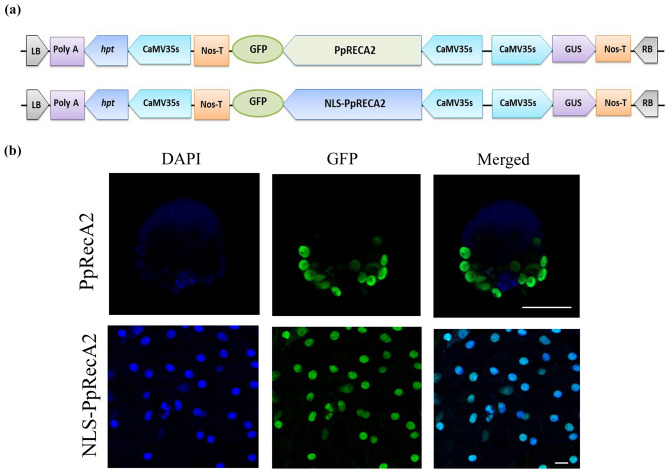

The NLS-PpRecA2 and the native PpRecA2 sequences were sub-cloned at XbaI and SacI sites with a modified green fluorescent protein (mGFP) sequence at the SmaI site of pCAMBIA 1301 under the control of CaMV 35S promoter and Nos terminator.

The constructs (NLS-PpRecA2-mGFP-pCAMBIA1301, PpRecA2-mGFP-pCAMBIA 1301, and empty vector) were mobilized into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain LBA4404 by the freeze–thaw method. Transgenic tobacco lines were obtained by Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated tobacco transformation (Yan and Ping 2013).

Total genomic DNA was isolated from all the putative transgenic tobacco lines along with wild-type plants, according to Dellaporta et al. (1983). PCR amplification for the transgene integration, PpRecA2, and NLS-PpRecA2 coding sequences, and the selection marker, hygromycin phosphotransferase gene (hpt) were carried out with specific primers. The details of the oligonucleotide primers used are given in supplementary table S1.

Sub-cellular localization

Protoplasts were isolated and also root squash slides were prepared from stable tobacco transgenic plants expressing PpRecA2-GFP and NLS-PpRecA2-GFP genes. The empty vector transformed (VT) and non-transformed wild-type (NT) plants were used as controls for both cases. GFP localization was observed under the optical zoom of a confocal microscope (Olympus IX81, Japan) at an excitation wavelength of 475 nm and an emission wavelength of 509 nm.

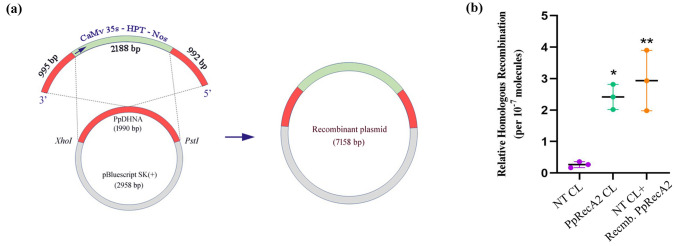

Generation of constructs for in vitro homologous recombination assay

An in vitro homologous recombination (IVHR) reaction was performed to further assess the change in functionality of the protein when differentially targeted. Chloroplast and nuclear lysates were prepared from PpRecA2 and NLS-PpRecA2 transgenic plants, respectively, and used to initiate recombination reactions between donor and receptor DNA molecules harboring homologous sequences in vitro, under suitable reaction conditions. In addition, two separate sets were prepared using wild-type plant organelle (chloroplast and nuclear) lysates, where purified PpRecA2 protein was added externally. Sets containing only wild-type plant organelle lysates were used as control.

The model plasmid for the in vitro homologous recombination (IVHR) was generated based on pBluescript SK(+). The gene PpDhnA (NCBI accession no. AY365466.1) of 1990 bp was cloned into the pBluescript SK(+) vector backbone at XhoI and PstI sites. This construct was used as the receptor DNA molecule in the IVHR assay. Primer details are given in supplementary table S1.

The donor DNA molecule was a linear double-stranded fragment of about 4200 bp size possessing a 2188 bp long sequence consisting of hygromycin phosphotransferase (hpt) gene along with its CaMV35S promoter and Nos terminator (35S-hpt-Nos), flanked by left and right terminal sequence of the PpDhnA gene.

Preparation of chloroplast and nuclear lysate

Isolation of intact chloroplasts was done from leaves of PpRecA2 transformed, (NT) and (VT) tobacco plants (Nakano and Asada 1981). The number of chloroplasts was determined using a hemocytometer. An equal amount of chloroplasts from each experimental set was taken and lysed using an ultrasonic processor UP100H (Hielscher, Germany). Membranes were pelleted by centrifugation at 700×g for 5 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was collected and stored at 4 °C until further use.

Nuclei were isolated according to (Sikorskaite et al. 2013) with minor modifications. An equal amount of nuclei from NLS-PpRecA2 transformed, (NT) and (VT) experimental sets were taken and lysed using an ultrasonic processor. Membranes were removed by centrifugation at 700×g for 5 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was collected and stored at 4 °C until further use.

In vitro homologous recombination (IVHR) assay

100 µl of the organelle lysates from the transgenic and wild-type plants were used for each reaction. ATP and MgCl2 were added to a final concentration of 10 mM. All the reaction sets contained 100 ng of the donor DNA molecule and 750 ng of receptor DNA molecule each. The final reaction volume was adjusted to 150 µl. The reaction mix was incubated at RT for 5 min followed by the addition of SDS to a final concentration of 0.5% to reduce the nuclease activity of chloroplast lysate. The reaction was carried out in dark for 40 min at room temperature. Finally, the IVHR reaction was terminated by adding SDS and EDTA to a final concentration of 1.5% and 50 mM, respectively. DNA was purified by a standard phenol–chloroform purification process and transformed into competent E. coli Top10 cells. Transformed cells were allowed to grow on ampicillin and hygromycin selection plates. Colony-forming units were counted for each reaction set and the IVHR event was confirmed by PCR analysis. The efficiency of HR was calculated based on the number of donor and acceptor molecules supplied and the number of recombinant molecules generated in the form of colonies on selection plates.

Results

Sequence analysis of RecA2 protein from Physcomitrium patens shows some degree of resemblance with bacterial RecA protein

The 3D model of the PpRecA2 protein from Physcomitrium patens showed about 71% query coverage, with a 51.87% sequence identity with E. coli RecA protein (4twz.1), as shown in supplementary figure S1a. The 3D model of the PpRecA2∆CLS sequence showed about 88% query coverage, with a 51.61% sequence identity with T. maritima RecA protein (3hr8.1), as shown in supplementary figure S1b. There was a substantial amount of resemblance in the secondary structure formation between these two sequences, as shown by the presence of regular repetitive α-helices and β-sheets, denoted by blue and green color, respectively, in supplementary figure S1c-d. The average model confidence was denoted by the QMEANDisCo of 0.73 ± 0.05, for both sequences. As expected, the 80 amino acid long chloroplastic localization signal (CLS) at the N-terminal of PpRecA2 protein from Physcomitrium rarely showed the formation of any secondary structures. Thus, we could infer that this sequence didn’t play any role in protein functioning. The superposed image of the two models showed consistency in their structural topology, supplementary figure S1c. The coding sequence of PpRecA2 was 1383 nucleotides (supplementary figure S3a) that encoded a 460 amino acid protein with a calculated molecular mass of 49.4 kDa (supplementary figure S4b). The Ramachandran plot for both the structures showed the presence of backbone torsion angles for most of the right-handed α-helices on the lower-left quadrant whereas all the β-sheets were made up of almost fully extended strands, with ϕ and ψ angles falling in the upper-left quadrant of the plot. These PpRecA2 and PpRecA2∆CLS models had 86.90% and 93.63% of their amino acids falling in the Ramachandran favored region, respectively (supplementary figure S1a-b inset).

Phylogenetic analysis of the PpRecA2 protein shows a close relationship with RecA proteins

Based on the phylogenetic tree, supplementary figure S2a, it can be hypothesized that the PpRecA2 protein originated early in the evolutionary history like that of Marchantia sp. RecA protein from E. coli is separated from that of the gram-positive bacteria. Escherichia coli RecA protein might also have originated from the same ancestor as that of the RecA protein from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, a photosynthetic green alga. The cyanobacterial RecA protein evolved separately from the bacterial RecA protein. The RecA protein in higher land plants formed a distinct lineage and evolved separately from the bacterial or cyanobacterial group. As we see a distinct difference reflected in the evolutionary history of RecA protein from Physcomitrium patens it becomes sensible to find out if this protein has some distinctive characteristics that originated early in the evolutionary history.

Analysis of the upstream sequence of the PpRecA2 gene

Analysis of the upstream sequence of the coding region of the recombinase PpRecA2 gene shows several cis-elements. Supplementary Table S2 shows the number of cis-elements present in the upstream sequence of this gene. There is presence of an ABRE-like/related element. There are 15 copies of MYB transcription factor recognition/binding elements and 20 copies of MYC transcription factor recognition/binding elements. The presence of these elements predicts the functionality of the protein during abiotic stress-mediated DNA damage repair conditions. There is the presence of 3 copies of each of WBOX related elements viz. WBOXATNPR1 and WBOXNTERF3, which are the site for the binding of salicylic acid-induced WRKY DNA binding proteins. Additionally, there is a low-temperature response element (LTRE1HVBLT49) and core of LTRE i.e. LTRECOREATCOR15, also present, which are related to light signaling during cold and drought stress. There is the presence of an IBOX element, several IBOXCORE elements, and a TBOXATGAPB element, which are related to light-regulated gene expression. Apart from this, a copy of EVENINGAT cis-element is also present which is known for circadian control of gene expression. An extensive representation of the cis-elements in the upstream region of the PpRecA2 gene has been shown in supplementary figure S2b. The abundance of abiotic stress and light-responsive cis-elements and the presence of a circadian cis-element account for their significant role under these conditions.

PpRecA2 transcripts showed differential regulation both under stressed and unstressed conditions

To confirm the involvement of PpRecA2 protein under DNA-damaging conditions, different concentrations (0.5, 1, and 1.5 µg/ml) of Mitomycin C were applied to Physcomitrium protonema. The accumulation of the PpRecA2 transcript was determined at different time points (6, 12, and 24 h). Our results showed that PpRecA2 transcripts increased upon treatment with MMC for a longer duration, as shown in Fig. 1a. Herein, a positive correlation was also observed for PpRecA2 transcripts and MMC concentration. Oxidative stress also induces DNA damage and this was studied using 100 mM MV and 100 mM H2O2 for 6 h under light conditions. PpRecA2 transcripts accumulated to a significant level as compared to unstressed conditions, as shown in Fig. 1b.

Fig. 1.

qRT PCR expression analysis of PpRecA2 transcript level in Physcomitrium patens protonemal tissue after a DNA damaging treatment for 6, 12, and 24 h using indicated concentrations of MMC; b oxidative stress treatment using 100 mM Methyl viologen (MV) and 100 mM H2O2; c continuous light (L) following 48H continuous dark treatment; d continuous dark condition (D) following 48H continuous light treatment; e qRT PCR expression analysis of PpRecA2 transcript level in transgenic tobacco expressing PpRecA2 under CaMV 35S promoter under continuous light (L) following 48H continuous dark treatment. For Physcomitrium patens, CAP50, and for tobacco, Actin was used as an internal control. Data are represented as relative expression levels with respect to 0H or control. Data are depicted as mean ± SD of three independent experiments; (*P < 0.01, **P < 0.001, and ***P < 0.0001 show statistically significant 381 differences with control/ 0H using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons test)

Differential pattern of PpRecA2 expression under L and D conditions

The PpRecA2 transcript accumulation followed a circadian pattern in L and D conditions, with peaks at 6H-L, 9H-D, and 24H-D whereas the transcript build-up was low at 3H-L, 24H-L, 3H-D, and 18H-D, as shown in Fig. 1c and d. This accumulation was compared to the expression of PpRecA2 in tobacco transgenic lines under L conditions, where the CDS was under a constitutive promoter. Our results however showed no significant changes, as shown in Fig. 1e.

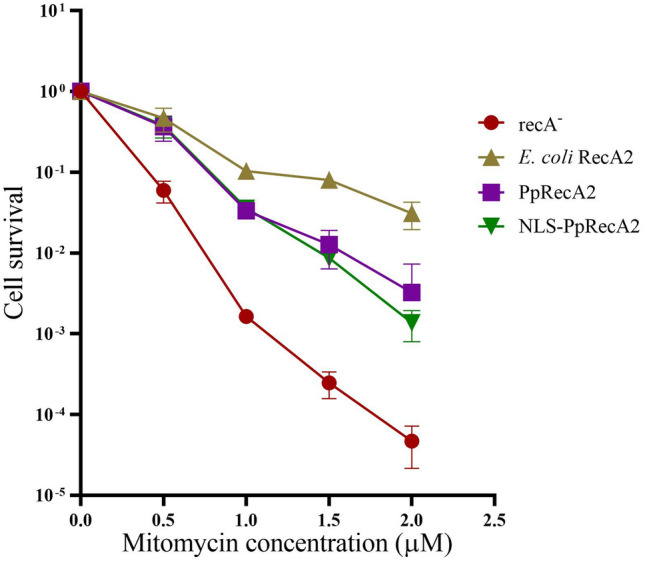

PpRecA2 protein from Physcomitrium patens could complement the bacterial RecA protein

Functional complementation assay for PpRecA2 and its bacterial counterpart was performed with a recA deficient E. coli JM109 strain. The expression cassettes for both PpRecA2 and modified NLS-PpRecA2 were transformed into E. coli JM109 strain and a gradual increase in protein expression after the addition of IPTG was obtained at an interval of 1 h for 5 h (supplementary figure S4–S6). Survival rates of cells were measured after treatment with the DNA cross-linking agent MMC. Upon addition of IPTG, the survival fraction of E. coli JM109 cells expressing the PpRecA2 or NLS-PpRecA2 was higher in comparison to that of the cells bearing an expression cassette lacking the RecA2 gene (Fig. 2). This result confirmed, that PpRecA2 can complement the function of E. coli RecA, which was in accordance with the work of Inouye et al. (2008). Additionally, we confirmed that NLS-PpRecA2 is functionally active in vivo and can retain its ability to protect DNA from MMC-mediated damages.

Fig. 2.

Escherichia coli RecA complementation assay. Comparative survival assay of E. coli Rosetta DE3 cells expressing bacterial RecA, E. coli JM109 (recA mutant) cells, and E. coli JM109 cells expressing PpRecA2 in response to the indicated concentrations of MMC. Error bars, S.D. (n = 3)

Recombinant PpRecA2 protein interacted with chloroplastic lysate to facilitate the recombination process

The entire coding sequence of the PpRecA2 protein was subcloned into the pET19b expression vector, thus generating an N-terminal 6× His tagged recombinant protein. A pictorial representation of the resultant expression cassette is shown in supplementary figure S4a. The recombinant PpRecA2 protein was expressed in bacterial over-expression host cells, E. coli Rossetta (DE3) pLysS, upon being induced with IPTG. An approximately 50.7 kDa protein was expressed in the pellet fraction as observed in 12% SDS–PAGE (Supplementary figure S4b). This protein was urea solubilized and affinity purified using a Ni–NTA agarose column where almost 95% homogenous protein was obtained. The purified protein was detected by western blotting analysis using rabbit anti-His primary antibody (Supplementary figure S4c, d).

For assessing the functional role of PpRecA2 protein in imparting DNA damage protection, tobacco lines over-expressing the native and nuclear-localized forms of PpRecA2 protein were generated. A schematic representation of the plant expression cassette is shown in Fig. 3a. PCR-positive lines for native PpRecA2 and NLS-PpRecA2 were selected (Supplementary figure S7) for studying the sub-cellular localization of the fusion proteins. The untransformed plants did not show any sign of fluorescence under the GFP filter. The micrographs obtained from the fluorescence microscopic data showed membrane-localized GFP fluorescence in empty vector-transformed plants (data not shown). The PpRecA2 protein showed a clear chloroplastic localization in the protoplasts whereas the NLS-PpRecA2 protein was localized to the nucleus, Fig. 3b.

Fig. 3.

Subcellular localization of PpRecA2. a Schematic representation of plant expression cassette of PpRecA2-GFP and NLS-PpRecA2-GFP; b Subcellular localization of PpRecA2 and NLS-PpRecA2 in leaf protoplasts and roots of transgenic tobacco plants

The in vitro experiments were done by using two types of DNA molecules, where a DNA fragment, PpDhnA995-35S-Hpt-Nos-PpDhnA992 containing a 2188 bp long hygromycin phosphotransferase gene flanked by 995 bp and 992 bp long PpDhnA gene left terminal and right terminal sequences, served as one of the recombining DNA fragment having ends homologous to a region of the second DNA molecule, which was a modified plasmid, pBluescript SK(+) vector harboring P. patens full-length PpDhnA gene, Fig. 4a. The IVHR reaction mix was used to transform competent E. coli Top10 cells followed by plating them in presence of hygromycin selection. In case of a positive HR reaction taking place, the hygromycin phosphotransferase gene will be transferred to the pBSK(+)-PpDhnA gene vector generating the recombinant plasmid pBSK(+)-PpDhnA995-35S-Hpt-Nos-PpDhnA992, capable of forming colonies in presence of hygromycin selection. Sets containing nuclear lysates along with purified PpRecA2 showed no colonies. Whereas the sets containing wild-type chloroplast lysate along with purified PpRecA2 showed the highest number of colonies depicting its relative homologous recombination reaction frequency to be almost 11 times and 6 times, that of non-transformed wild-type plants and PpRecA2 transgenic plant chloroplast lysate containing sets, respectively, Fig. 4b.

Fig. 4.

In vitro recombination assay a Schematic representation of in-vitro recombination construct and recombinant product; b relative in vitro homologous recombination reaction frequency of non-transformed wild-type tobacco chloroplast lysate (NT-CL) and PpRecA2 transgenic plant chloroplast lysate (PpRecA2-CL) along with non transformed wild type chloroplast lysate supplemented with bacterially overexpressed and His-purified PpRecA2 (NT CL + Recomb. PpRecA2). Data are depicted as mean ± SD of three independent experiments; (*P < 0.01, **P < 0.001, and ***P < 0.0001 show statistically significant differences with control/0H using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons test)

Discussion

RecA protein taking part in the initiation of HR reactions is an important tool for repairing DNA lesions, a process that has been conserved throughout the plant kingdom. As depicted by the phylogenetic analysis, Physcomitrium patens RecA proteins evolved quite early. In the current study, we could see that the PpRecA2 protein could complement RecA mutant E. coli strain. When we over-expressed PpRecA2/NLS-PpRecA2 proteins in RecA deficient strain JM109 cells and subjected them to the DNA damaging agent, MMC, the bacterial growth remained unaffected. Whereas in the control set, the growth declined within 1 h of the addition of MMC. Thus we could confirm that the PpRecA2 protein was fully functional and could override RecA mutation effects in a prokaryotic cell, even when its chloroplast localization signal of 240 bps at the N-terminal end, was replaced by the NLS of SV-40.

Additionally, the cis-acting regulatory elements predicted the expression of PpRecA2 protein to be governed by abiotic stress-causing oxidative damage to DNA. The promoter region consists of elements that respond to cold and drought-induced DNA damage stress and are involved in subsequent light signaling. Real-time PCR analysis on moss tissue kept under conditions mimicking these stress conditions showed a spike in the transcript level of the protein when the moss protonema was subjected to various types of DNA damaging conditions in the form of the presence of H2O2, MV, and MMC in the growth media and it indicates PpRecA2 protein’ role in the initiation of DNA repair mechanism.

RecA recombinase is closely related to three other groups of ATPases, namely bacterial Sms (also called RadA), bacterial DnaB, and archaeal and bacterial KaiC (Leipe et al. 2000).Interestingly, the cyanobacterial KaiABC gene cluster constitutes the circadian clock in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. (Ishiura et al. 1998; Iwasaki et al. 1999). Results from our studies involving PpRecA2 transcript accumulation in continuous light and dark conditions were somewhat similar to those obtained from studies done on the circadian cycling of KaiC phosphorylation rhythm of Synechococcus elongatus under similar conditions (Woelfle et al. 2007; Kitayama et al. 2008). The KaiC protein generates a circadian oscillation that controls genome-wide gene expression in cyanobacteria, pointing out the possible involvement of the PpRecA2 protein in the same. It has also been reported that RecA and KaiC share significant sequence similarities in a region consisting of about 250 amino acids, which includes the ATP binding domain and DNA binding site (Leipe et al. 2000). Our studies on promoter analysis showed the presence of elements responsive to light (MYB transcription factor recognition/binding elements) and circadian rhythm (EVENINAT element). These elements have been reported to be the binding site of MYB transcription factors, CCA1and LHY (Andronis et al. 2008). The oscillation pattern of PpRecA2 transcript accumulation showed a peak after 9 h of continuous dark treatment which dampened to the lowest after 18 h, then the levels started increasing again. This pattern was to some extent similar to the accumulation pattern of PpCCA1a and PpCCA1b, observed under similar conditions (Holm et al. 2010). These MYB transcription factors have been shown to control several genes like PpLhcb2, a chloroplast localized protein, whose expression shows a circadian rhythm (Aoki et al. 2004). Thus we could predict the PpRecA2 gene to be a circadian clock gene, whose expression may be under the control of rhythmic oscillations of certain light-regulated transcription factors like PpCCA1a and PpCCA1b. This was in agreement with the previously reported role of the kaiC gene in circadian control and its homology to the recA gene.

In vivo experiments have detected fluorescence of PpRecA1-GFP fusion proteins only in the mitochondria (Odahara et al. 2007) and that of PpRecA2-GFP in the chloroplast (Inouye et al. 2008). Based on these lines of evidence, it has been concluded that the PpRecA2 gene encodes a bacterial-type RecA homolog that functions in the chloroplasts. Reports suggest that the organelle-targeted RecA proteins in moss Physcomitrium patens namely PpRecA1 and PpRecA2 can repair damaged DNA in mitochondria and chloroplast, respectively (Rowan et al. 2010; Odahara et al. 2015; Khazi et al. 2003). Studies have depicted the full-length PpRecA2 protein-formed foci in P. patens chloroplasts. The foci were found to be colocalized with chloroplast nucleoids forming nucleoprotein filaments, suggesting that PpRecA2 is bound to chloroplast DNA (cpDNA) (Inouye et al. 2008; Cerutti et al. 1995). In the present study, we were interested to find out if the chloroplastic PpRecA2 can be used in repairing nuclear DNA in tobacco plants. To achieve this, we cloned the PpRecA2 CDS from moss P. patens and transformed it into a wild-type tobacco plant. We also deleted the chloroplastic target peptide and replaced it with a nuclear localization signal. The differential localization of the PpRecA2 protein was confirmed by externally tagging the recombinant proteins with mGFP. Confocal micrograph analysis showed the localization of the protein in the chloroplast and nucleus, respectively.

Furthermore, in the current study, we verified whether PpRecA2 when overexpressed in its native form or a modified nuclear-targeted form, can initiate DNA repair by recombination in vitro, in presence of suitable substrates. As known, Nicotiana tabacum RecA protein is also present in the chloroplast compartment of tobacco plants (Kavanagh et al. 1999), therefore its effects on the in vitro HR (IVHR) experiments were nullified by using non-transformed or wild-type tobacco chloroplast as control. It was seen that chloroplast localized PpRecA2 protein of the moss favored homologous recombination between the participating DNA molecules, whereas its nuclear-localized form did not show any effect on the DNA molecules used for studying recombination. Our results showed that this protein was rendered completely inactive when targeted to the nucleus, which might be due to the absence of its interacting partners. The interacting protein partners of the PpRecA2 play an important role in accomplishing the mechanism of homologous recombination. These interacting proteins being missing in the nuclear compartment of the transgenic tobacco plants impaired the in vitro HR reactions. IVHR result was in good agreement with previous findings, where P. patens were reported to harbor factors like MutS homolog1 (MSH1A and MSH1B), RECX, RECG, which were found to be organelle targeted and their knockout mutants were incapable of maintaining cpDNA integrity despite having a functional RecA2 protein (Odahara and Sekine 2018; Odahara et al. 2017).

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to DST- FIST and UGC CAS for the instrumental facilities of the Department of Botany, University of Calcutta. This work is supported by a Grant to SR from the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India (Sanction No. BT/PR8377/PBD/16/1046/2013). CC, AD, CB and ShR thanks University Grants Commission, Government of India for Research Fellowship (Sanction No. UGC/1060/Fellow (Univ.) 22/08/2014; 813/(CSIR-UGC NET DEC. 2016); UGC/134/JR. Fellow 03/02/2015; 2061530629 dated 10/12/2015 respectively), TA thanks CSIR for Research Fellowship (Sanction No. 09/0028(11361)/2021-EMRI-I).

Author contribution

SR conceived the original research plans and supervised the experiments; CC and AD performed most of the experiments; CC, AD, CB, and SR designed the experiments and analyzed the data; ShR maintained transgenic tobacco lines; CB and ShR contributed equally to the work; TA provided protonema tissue material. SR conceived the project and wrote the article with contributions from all the authors; SR supervised and complemented the writing.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Chandrima Chakraborty, Email: chandrima_mun@yahoo.co.in.

Arup Das, Email: arup.das.das24@gmail.com.

Chandra Basak, Email: basak.chandra@gmail.com.

Shuddhanjali Roy, Email: roy.shuddhanjali@gmail.com.

Tanushree Agarwal, Email: tans_911@yahoo.co.in.

Sudipta Ray, Email: srbot@caluniv.ac.in.

References

- Andronis C, Barak S, Knowles SM, Sugano S, Tobin EM. The clock protein CCA1 and the bZIP transcription factor HY5 physically interact to regulate gene expression in Arabidopsis. Mol Plant. 2008 doi: 10.1093/mp/ssm005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki S, Kato S, Ichikawa K, Shimizu M. Circadian expression of the PpLhcb2 gene encoding a major light-harvesting chlorophyll a/b-binding protein in the moss physcomitrella patens. Plant Cell Physiol. 2004 doi: 10.1093/pcp/pch006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerutti H, Jagendorf AT. DNA strand-transfer activity in pea (Pisum sativum L.) chloroplasts. Plant Physiol. 1993;102(1):145–153. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.1.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerutti H, Ibrahim HZ, Jagendorf AT. Treatment of pea (Pisum sativum L.) protoplasts with DNA-damaging agents induces a 39-kilodalton chloroplast protein immunologically related to Escherichia coli RecA. Plant Physiol. 1993;102(1):155–163. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.1.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerutti H, Johnson AM, Boynton JE, Gillham NW. Inhibition of chloroplast DNA recombination and repair by dominant negative mutants of Escherichia coli RecA. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15(6):3003–3011. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.6.3003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellaporta SL, Wood J, Hicks JB. A plant DNA minipreparation: version II. Plant Mol Biol Rep. 1983;1(4):19–21. doi: 10.1007/BF02712670. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dingwall C, Laskey RA. Nuclear targeting sequences—A consensus? Trends Biochem Sci. 1991;16(C):478–481. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(91)90184-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbat JG, Lambert S, Bertrand P, Lopez BS. Is homologous recombination really an error-free process? Front Genet. 2014;5(6):175. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2014.00175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higo K, Ugawa Y, Iwamoto M, Korenaga T. Plant cis-acting regulatory DNA elements (PLACE) database: 1999. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27(1):297–300. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.1.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm K, Källman T, Gyllenstrand N, Hedman H, Lagercrantz U. Does the core circadian clock in the moss Physcomitrella patens (Bryophyta) comprise a single loop? BMC Plant Biol. 2010 doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-10-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inouye T, Odahara M, Fujita T, Hasebe M, Sekine Y. Expression and complementation analyses of a chloroplast-localized homolog of bacterial recA in the moss Physcomitrella patens. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2008;72(5):1340–1347. doi: 10.1271/bbb.80014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiura M, Kutsuna S, Aoki S, Iwasaki H, Andersson CR, Tanabe A, Golden SS, Johnson CH, Kondo T. Expression of a gene cluster kaiABC as a circadian feedback process in cyanobacteria. Science. 1998 doi: 10.1126/science.281.5382.1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki H, Taniguchi Y, Ishiura M, Kondo T. Physical interactions among circadian clock proteins KaiA, KaiB and KaiC in cyanobacteria. EMBO J. 1999 doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.5.1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavanagh TA, Thanh ND, Lao NT, McGrath N, Peter SO, Horváth EM, Dix PJ, Medgyesy P. Homeologous plastid DNA transformation in tobacco is mediated by multiple recombination events. Genetics. 1999;152(3):1111–1122. doi: 10.1093/genetics/152.3.1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khazi FR, Edmondson AC, Nielsen BL. An Arabidopsis homologue of bacterial RecA that complements an E. coli recA deletion is targeted to plant mitochondria. Mol Genet Genomics. 2003;269(4):454–463. doi: 10.1007/s00438-003-0859-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitayama Y, Nishiwaki T, Terauchi K, Kondo T. Dual KaiC-based oscillations constitute the circadian system of cyanobacteria. Genes Dev. 2008 doi: 10.1101/gad.1661808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leipe DD, Aravind L, Grishin NV, Koonin EV. The bacterial replicative helicase DnaB evolved from a RecA duplication. Genome Res. 2000;10(1):5–16. doi: 10.1101/gr.10.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li A, Schuermann D, Gallego F, Kovalchuk I, Tinland B. Repair of damaged DNA by arabidopsis cell extract. Plant Cell. 2002;14(1):263–273. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Z, Kong H, Nei M, Ma H. Origins and evolution of the recA/RAD51 gene family: evidence for ancient gene duplication and endosymbiotic gene transfer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(27):10328–10333. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604232103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano Y, Asada K. Hydrogen peroxide is scavenged by ascorbate-specific peroxidase in spinach chloroplasts. Plant Cell Physiol. 1981;22(5):867–880. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a076232. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Odahara M, Sekine Y. RECX interacts with mitochondrial RECA to maintain mitochondrial genome stability. Plant Physiol. 2018;177(1):300–310. doi: 10.1104/pp.18.00218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odahara M, Inouye T, Fujita T, Hasebe M, Sekine Y. Involvement of mitochondrial-targeted RecA in the repair of mitochondrial DNA in the moss, Physcomitrella patens. Genes Genet Syst. 2007;82(1):43–51. doi: 10.1266/ggs.82.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odahara M, Kuroiwa H, Kuroiwa T, Sekine Y. Suppression of repeat-mediated gross mitochondrial genome rearrangements by RecA in the moss Physcomitrella patens. Plant Cell. 2009;21(4):1182–1194. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.064709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odahara M, Inouye T, Nishimura Y, Sekine Y. RECA plays a dual role in the maintenance of chloroplast genome stability in Physcomitrella patens. Plant J. 2015;84(3):516–526. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odahara M, Kishita Y, Sekine Y. MSH1 maintains organelle genome stability and genetically interacts with RECA and RECG in the moss Physcomitrella patens. Plant J. 2017;91(3):455–465. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigge MJ, Bezanilla M. Evolutionary crossroads in developmental biology: Physcomitrella patens. Development. 2010;137(21):3535–3543. doi: 10.1242/dev.049023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puchta H. The repair of double-strand breaks in plants: mechanisms and consequences for genome evolution. J Exp Bot. 2005;56(409):1–14. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eri025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran GN, Ramakrishnan C, Sasisekharan V. Stereochemistry of polypeptide chain configurations. J Mol Biol. 1963 doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(63)80023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowan BA, Oldenburg DJ, Bendich AJ. RecA maintains the integrity of chloroplast DNA molecules in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot. 2010;61(10):2575–2588. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy S. Maintenance of genome stability in plants: repairing DNA double strand breaks and chromatin structure stability. Front Plant Sci. 2014;5(September):1–6. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarpeci TE, Zanor MI, Carrillo N, Mueller-Roeber B, Valle EM. Generation of superoxide anion in chloroplasts of Arabidopsis thaliana during active photosynthesis: a focus on rapidly induced genes. Plant Mol Biol. 2008;66(4):361–378. doi: 10.1007/s11103-007-9274-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikorskaite S, Rajamäki ML, Baniulis D, Stanys V, Valkonen JPT. Protocol: optimised methodology for isolation of nuclei from leaves of species in the Solanaceae and Rosaceae families. Plant Methods. 2013;9(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/1746-4811-9-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studer G, Rempfer C, Waterhouse AM, Gumienny R, Haas J, Schwede T. QMEANDisCo—distance constraints applied on model quality estimation. Bioinformatics. 2020;36(6):1765–1771. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woelfle MA, Xu Y, Qin X, Johnson CH. Circadian rhythms of superhelical status of DNA in cyanobacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2007;104(47):18819–18824. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706069104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan H, Ping BY. Transgenic plants. Microb Biotechnol Princ Appl Third Ed. 2013;50:521–583. doi: 10.1142/9789814366830_0015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.