Abstract

Purpose of Review

Though most of the attention in recent literature on baseball injuries has been paid to throwers, one often overlooked aspect of the game is the effect of the batter’s swing on the shoulder. It is well known that the batter’s lead shoulder can experience significant translational forces during the player’s swing, and that these are increased following a missed swing. The purpose of this paper is to review the background and pathophysiology as well as clinical presentation and treatment of players with Batter’s shoulder.

Recent Findings

Recent studies demonstrate that while nonoperative treatment of Batter’s shoulder is still a viable first line of treatment, favorable outcomes have been reported with arthroscopic posterior labral repair for high level athletes.

Summary

Batter’s injury can cause significant pain and dysfunction in baseball hitters, especially during the follow through phase of swing. While conservative care can be attempted early, outcomes following arthroscopic posterior labral repair are favorable with a high rate of return to play.

Keywords: Shoulder, Batter’s shoulder, Posterior shoulder instability, Glenoid labral tear

Introduction/Background

Baseball is one of the most popular sports in America across all ages. Over the years, much of the emphasis in orthopedic literature has been on the effects of throwing and their implications for shoulder and elbow injuries. However, batters also place a significant amount of posterior-directed force across the lead shoulder during the transition from swing to follow-through phase. Forces are much greater during a swing and miss—when they are not partially transferred to the incoming baseball—which occurs roughly a quarter of the time [1]. These forces can cause an acute posterior glenohumeral subluxation in the lead shoulder, resulting in injury to the posterior glenoid labrum.

Pathophysiology

The hitter’s swing is divided into four phases: windup, pre-swing, swing, and follow through [2]. During the swing phase, a tremendous amount of power from the lower kinetic chain is transferred through the trunk and converted rotational velocity in the hitter’s arms and bat. This motion is what allows for hitters to achieve rotational velocities of 937° per second at the shoulder and 1588° per second at the bat [3].

These forces place a significant amount of posterior-directed force on the lead shoulder of the hitter, which can be up to 500 N [4•]. Lack of contact with the incoming baseball results in failure to dissipate these forces, and may result in generated glenohumeral forces that are in excess of posterior soft tissue structure stabilizers’ capacity to stabilize the shoulder. Additionally, failure to make contact with the baseball results in a lack of activation of adjacent powerful shoulder stabilizing muscles, preventing their ability to control glenohumeral translation [4•]. Furthermore, attempting to reach for a pitch on the outside of the plate results in a higher shoulder adduction angle, increasing torque generated during swinging at these pitches by 13.5% and increasing shear forces across the shoulder [4•, 5•]. For these reasons, Batter’s shoulder is thought to result from the attempted swinging and missing at outside pitches [5•]. Elite-level baseball players can expect to take tens of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of swings in their career, which can amplify the risks of injury.

Clinical Presentation

Typically, players with Batter’s shoulder will present with posterior-based shoulder pain. Often, they may note a specific episode in which they had a sharp pain and feeling of instability in the lead shoulder during a swing. The pain will be worse during the follow-through phase of swing. Hitters will report pain is most severe when swinging and missing at the ball and when attempting to hit outside pitches [6]. Hitters may also note that provocative activities such as push-ups or bench press, in which the arm is in the adducted, internally rotated, and forward-flexed position, will also cause pain [7].

Physical exam should begin with a full assessment of shoulder range of motion, dynamic scapular assessment as well as an assessment of the player’s kinetic chain. Strength testing of the rotator cuff and other periscapular testing should also be performed. On provocative testing, players will usually have a positive posterior load and shift test and a positive Kim and Jerk test [8] The combination of these two specialty tests results in a sensitivity of 97% [8]. Additionally, players may have a positive O’Brien’s test.

Imaging

Imaging studies should begin with plain X-rays of the shoulder, including standard views as well as a well-performed axillary view. These images should be used to rule out obvious pathologies such as fractures or shoulder dislocations. These films should also be analyzed for evidence of previous instability episodes, such as reverse Hill-Sachs lesions, glenoid bone loss, glenoid dysplasia or retroversion, bony avulsions of the posterior capsule, and glenohumeral ligaments.

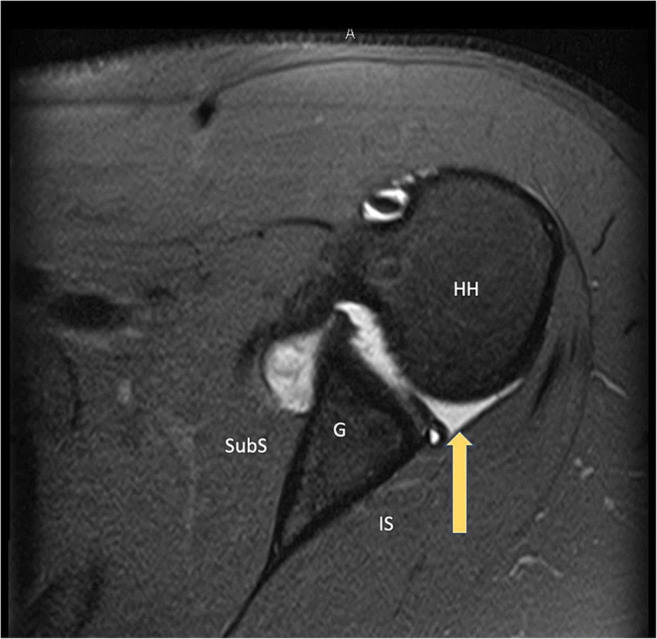

In most cases, MRI arthrogram of the shoulder is warranted as a follow-up study to damage to the posterior labrum, capsule, and capsular ligaments, as well as associated chondral injuries to the glenoid. The presence of Kim lesions, or superficial tears between the posterior glenoid labrum and glenoid articular cartilage without labral detachment, should also be assessed [9]. MR arthrograms are preferred to plain MRI given their increased ability to detect subtle labral pathology (Fig. 1) [10, 11•].

Fig. 1.

MR Arthrogram demonstrating a Batter’s shoulder posterior labral tear. Image from ref. [11•]

CT scan can be useful in the setting of reverse Hill-Sachs lesions, suspected glenoid bone loss, significant glenoid dysplasia, or assessing glenoid of humeral retroversion but are not necessary and are not routinely obtained.

Management

Initial treatment of Batter’s shoulder starts conservatively. Players should immediately begin a period of rest from aggravating activities. Press-type activities in which the shoulder is placed into an adducted flexed and internally rotated position, such as bench press, should also be avoided. Additionally, players should initiate a course of physical therapy with both diagnostic and therapeutic goals. The therapist should start by assessing a player’s shoulder motion, flexibility, scapular dynamics, and rotator cuff strength as well as assessing the entire kinetic chain. Treatments should be aimed at improving shoulder range of motion, rotator cuff strengthening, scapular stabilization and periscapular muscle strengthening, as well as addressing any kinetic chain deficiencies. A minimum of 12 weeks of conservative treatment is completed prior to discussion of surgical intervention. If nonoperative treatment is unsuccessful, surgical management is appropriate. Surgical management consists of arthroscopic posterior labral repair.

Author’s Preferred Surgical Technique

We prefer performing the procedure with the patient in the lateral position as we feel it allows for more complete access to the glenoid labrum. Following administration of regional anesthesia and sedation, an examination under anesthesia is performed to assess both the patient’s range of motion as well as degree of glenohumeral instability and laxity.

After administration of preoperative antibiotics, the appropriate surgical extremity is prepped and draped in sterile fashion. We start the procedure by making a posterior viewing portal. We aim to make this portal slightly more lateral than typical to allow for potential instrumentation and anchor placement through this portal. We utilize a 30° arthroscope for this procedure; however, having a 70° scope available potentially can be useful, especially if there are associated posterior capsular tears that require repair. A diagnostic arthroscopy is performed, during which an anterior portal is established. An additional accessory anterosuperior portal or trans-rotator cuff portal can be established at this time to help facilitate suture passage if desired. The arthroscope is then moved into the anterior portal for better visualization of the posterior labrum and the labrum is elevated manually with an arthroscopic elevator. The labrum bone interface is then prepared with the help of a ball rasp and motorized shaver.

We begin the labral repair by starting at the most inferior aspect of the tear. The focus of the repair should be in restoring the correct anatomical attachment of the posterior band of the inferior glenohumeral ligament (IGHL). We start by establishing a low percutaneously placed portal using a commercially available kit. We find this portal is extremely useful at obtaining the proper drill trajectory for the placement of inferior anchors. It is worth noting, however, that care must be taken when placing this portal as there is risk of injury to the axillary nerve. If a very low anchor is required, we start with a suture first technique, utilizing a single knotless anchor (Arthrex 2.9 mm Pushlock). First, we use a curved suture passer (25 deg Arthrex Lasso) to capture the capsuloligamentous tissue with a heavy nonabsorbable suture at the posterior band of the IGHL. Next, the anatomic attachment of the posterior band of IGHL is determined and the loaded suture anchor is drilled and placed in the posterior band IGHL footprint via our percutaneous portal. After restoration of the IGHL, subsequent anchors are placed in a clockwise direction to secure the rest of the labrum. For this, we like to utilize an anchor first technique by first placing a small all suture type anchor (Arthrex 1.8 mm Knotless FiberTak) in the appropriate position on the glenoid rim. A curved drill guide can be helpful to obtain the appropriate trajectory for anchor placement. The anchor is then inserted and set in the bone. The preloaded tape-style suture is then passed through the capsule-labral complex with a curved suture passer and is then loaded through the anchor through the preloaded looped passing suture. This repair tape-style suture can then be used to manually tension the soft tissue until the capsule-labral complex is reduced. We continue in this manner in a clockwise direction until rest of the labrum has been secured. Before completion of the case, the posterior portal is sutured closed using an arthroscopic technique and a heavy non-absorbable suture (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

A, B Intraoperative photos demonstrating fraying and tearing of the posteroinferior labrum with partial healing of the medialized labrum. C Dynamic assessment of the shoulder reproduces posterior subluxation of the humeral head. D Arthroscopic posterior labral repair utilizing 3 suture anchors in a “suture first” technique

Postoperatively, the patient is placed into a sling for a total of 6 weeks to allow soft tissue healing. During the first 2 weeks, gentle range of motion of the elbow and wrist is encouraged. Additionally, formal therapy can be initiated after the first week to work on gentle submaximal shoulder passive range of motion, avoiding internal rotation. After 2 more weeks, active shoulder range of motion is encouraged in all planes except internal rotation. Strengthening of the shoulder and scapular stabilizers can also begin in protected shoulder positions, which limit shoulder abduction. By 8 weeks, the patient should work to obtain full shoulder range of motion in all planes. At 4 months, gradual shoulder strengthening and sport-specific activities, such as hitting off a tee, can begin. Players can begin taking live batting practice sometime between the 5th and 6th months.

Patient Outcomes

The first published outcome study on Batter’s shoulder evaluated 14 elite baseball players from high school to professional (aged 17–33) and followed them for a median of 1.2 years. They found only 2 of 14 (14%) players were able to return to play following non-operative management. Twelve of the 14 underwent operative treatment with 10 undergoing labral repair, and 2 undergoing a labral debridement only. Of the 10 patients undergoing labral repair, all of them had Kim type III lesions (chondrolabral erosion) and underwent labral repair with an average of 2.2 bioabsorbable suture anchors. Eleven of 12 players treated operatively returned to play at an average of 6 months [12•]. All patients regained near preoperative internal and external range of motion of the shoulder. A more recent study of 5 athletes with acute Batter’s shoulder-type injury found 100% return to play following arthroscopic posterior labral repair [11•]. All players regained full strength and range of motion.

Conclusions

Traumatic posterior glenohumeral instability caused by batting is a rare condition that affects both elite level as well as amateur hitters alike. It is caused by the tremendous rotation forces that are generated in the shoulder while attempting to impart power into the incoming baseball. These rotational forces of the bat are felt by the shoulder in the form of posterior translational forces at the glenohumeral joint, which are imparted onto the posterior labral complex.

Generally, non-operative management is preferred as first-line treatment. If conservative measures fail, arthroscopic posterior labral repair is associated with excellent rates of return to play. However, outcomes data is derived from a small number of small studies. More robust and higher-level studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors do not have existing conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Injuries in Overhead Athletes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance

- 1.Baseball ML. Statcast Hitting MLB.com. https://baseballsavant.mlb.com/league.

- 2.Shaffer B, Jobe FW, Pink M, Perry J. Baseball batting: an electromyographic study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;292(292):285–293. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199307000-00038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Welch CM, Banks SA, Cook FF, Draovitch P. Hitting a baseball: a biomechanical description. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1995;22(5):193–201. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1995.22.5.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.• Kang RW, Mahony GT, Harris T, Dines J. Posterior instability caused by Batter’s shoulder. Clin Sport Med. 2013;32:797-802. This was the first comprehenisve review article on the topic of Batter's shoulder. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.• Philips B, Andrews J, Fleisig G. Batter’s shoulder: posterior instability of the lead shoulder, a biomechanical evaluation. Birmingham, AL; 2000. Dr. Andrews was one of the first surgeons to describe the problem of Batter's shoulder and potental mechanism of injury in detail.

- 6.Dugas JR. The Batter’s shoulder. In: Dines JM, Altchek DW, Andrews J, ElAttrache NS, Wilk KE, Yocum LA, editors. Sports medicine of baseball. 1. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2012. pp. 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hawkins RJ, Koppert G, Johnston G. Recurrent posterior instability (subluxation) of the shoulder. J Bone Jt Surg Ser A. 1984;66(2):169–174. doi: 10.2106/00004623-198466020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim SH, Park JS, Jeong WK, Shin SK. The Kim test: a novel test for posteroinferior labral lesion of the shoulder—a comparison to the Jerk test. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(8):1188–1192. doi: 10.1177/0363546504272687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim SH, Ha KI, Yoo JC, Noh KC. Kim’s lesion: An incomplete and concealed avulsion of the posteroinferior labrum in posterior or multidirectional posteroinferior instability of the shoulder. Arthrosc J Arthrosc Relat Surg. 2004;20(7):712–720. doi: 10.1016/S0749-8063(04)00597-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Magee T. 3-T MRI of the shoulder: Is MR arthrography necessary? Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192(1):86–92. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.• OKeefe KJ, Haupt E, Thomas WC, et al. Batter’s shoulder: clinical outcomes and return to sport. Cureus. 2020;12(4). 10.7759/cureus.7681. This is the most recent case series evaluating surgcal outcomes following arthroscopic posterior labral repair for batter's shoulder. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.• Wanich T, Dines J, Dines D, Gambardella RA, Yocum LA. “Batter’s shoulder”: can athletes return to play at the same level after operative treatment? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(6):1565-1570. 10.1007/s11999-012-2264-0. This was the first case series which systematically evaluated player outcomes following surgical management of Batter's Shoulder. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]