Abstract

Efforts to make research environments more inclusive and diverse are beneficial for the next generation of Great Lakes researchers. The global COVID-19 pandemic introduced circumstances that forced graduate programs and academic institutions to re-evaluate and promptly pivot research traditions, such as weekly seminar series, which are critical training grounds and networking opportunities for early career researchers (ECRs). While several studies have established that academics with funded grants and robust networks were better able to weather the abrupt changes in research and closures of institutions, ECRs did not. In response, both existing and novel partnerships provided a resilient network to support ECRs at an essential stage of their career development. Considering these challenges, we sought to re-frame the seminar series as a virtual collaboration for ECRs. Two interdisciplinary graduate programs, located in different countries (Windsor, Canada, and Detroit, USA) invested in a year-long partnership to deliver a virtual-only seminar series that intentionally promoted: the co-creation of protocols and co-led roles, the amplification of justice, equity, diversity and inclusion throughout all aspects of organization and representation, engagement and amplification through social media, the integration of social, scientific and cultural research disciplines, all of which collectively showcased the capacity of our ECRs to lead, organize and communicate. This approach has great potential for application across different communities to learn through collaboration and sharing, and to empower the next generation to find new ways of working together.

Keywords: Great Lakes, Seminar series, Early career researchers, Interdisciplinarity, Collaboration, Education

Introduction

Research environments that are intentionally inclusive and diverse provide a competitive edge, research excellence and positive societal impact (Powell, 2018, Swartz et al., 2019). In an effort to redefine and promote research excellence, new approaches for training must be re-imagined and boldly pursued. Focusing on early-career guidance is essential in providing critical training in the environmental and sustainability sciences (Lim et al., 2017). Thus, prompted by but not solely due to the current and ongoing global pandemic, we sought to reframe and re-envision a traditional element of research environments: the seminar series.

To do this, we intentionally brought together two different but complementary graduate programs: Environmental Science at the Great Lakes Institute for Environmental Research (GLIER; STEM disciplines) and Transformative Research in Urban Sustainability Training (T-RUST; interdisciplinary inclusive of social, natural & physical sciences/STEM). We worked over several months to co-deliver a single, virtual seminar series entitled “Transformative Change in Environmental Sustainability” (together with the complementary hashtag #GLIERTRUSTvirtual). This initially stemmed from a casual partnership between two faculty with similar interests and then developed into a formal partnership between T-RUST and GLIER, which are located on opposite sides of the Detroit River in the Laurentian Great Lakes Basin. T-RUST is based out of Wayne State University in Detroit, Michigan, USA whereas GLIER is based out of the University of Windsor, Ontario, Canada. At the outset, under the cloud of the COVID-19 pandemic, graduate students who for the most part had never personally met or worked together previously formed an organizing committee to deliver a year-long, entirely virtual seminar series. Faculty mentors (Febria, Kashian, Mundle) initiated group meetings to bring together graduate students from both the GLIER and T-RUST programs late in the summer of 2020 when it was clear that all teaching would continue online for the Fall.

At every opportunity, we challenged ourselves to consider how the traditional seminar series could best serve early career researchers (ECRs) at a time when networking and training opportunities that support their professional development, including international collaborations, were reduced or removed altogether (Herman et al., 2021). The definition of ECR varies widely across contexts; here we defined ECRs to include those early in their training and professional career, which included graduate students, postdoctoral researchers, science practitioners, and faculty members within the first five years of their academic appointment. Our focus on ECRs was inclusive of the organizing team (herein referred to as ‘ECR organizers’), the seminar attendees and invited speakers. Thus, a focus on ECR training and network development was a primary focus of this effort.

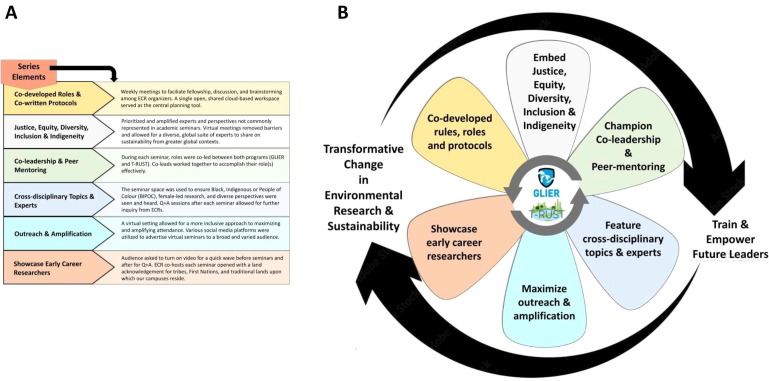

The resultant #GLIERTRUSTvirtual seminar and panel series was launched in September 2020 and continued through April 2021 in response to the cancellation of in-person classes and meetings at both universities, with the goal of providing professional development opportunities for ECRs. The ECR co-organizers co-developed every element as a team from the series theme, invited speakers and panelists, sponsors and the organization of a capstone event featuring their own research at the conclusion of the series. Transdisciplinary seminars spanned a range of cross-cutting disciplines from the natural, physical, social and environmental sciences, and also included panels featuring experts in Indigenous knowledge systems, community engagement, non-profit organizations and industry. By being intentionally international, interdisciplinary, and inclusive, the team explored perspectives and assumptions typically not addressed in disciplinary-based seminar series more tacitly than explicitly. Here we describe key elements featured in the development and delivery of a collaborative, virtual seminar series led by and for ECRs. They included: co-developed rules, roles and protocols, co-leadership and peer mentoring, cross-disciplinarity, justice, equity, diversity, inclusion, Indigeneity, and outreach ( Fig. 1 ). We offer operational insight framed here as key rules for how such an approach can serve as a blueprint for re-energizing the traditional seminar series model moving forward and across all research environments globally.

Fig. 1.

(A) Series elements co-developed and featured throughout the GLIER and T-RUST virtual seminar series which are broadly applicable to other seminar settings, and (B) visualized as a complementary elements designed to train and empower future leaders in environmental research and sustainability. ECR = Early career researcher; GLIER = Great Lakes Institute for Environmental Research; T-RUST = Transformative Research in Urban Sustainability, Q + A = Question and Answer period.

Co-develop roles, rules and protocols

A central vision for this collaboration was co-crafted by the ECR organizers with faculty members facilitating discussion and encouraging consensus-based decision-making. We established regular meetings and democratized our decision-making by allowing members to propose, discuss, and vote on topics, speakers, and seminar organization. The T-RUST program administrator (Wallen) scheduled weekly hour-long virtual meetings to instill and foster fellowship among ECR organizers. Weekly to bi-weekly meetings were designed to encourage students from both programs to jointly discuss a vision for the series, explore shared topics or speakers of interest and to brainstorm ideas for the series. Collectively and collaboratively, students agreed on the theme of “Transformative change in environmental sustainability research” that would span a range of cross-cutting disciplines from the natural, physical, social and environmental sciences. Top of mind, and perhaps reflective of the current social climate, was the intention to include panels on Traditional Ecological Knowledge and research partnerships with non-profits, community groups, and industry from across Canada, the USA, First Nations and Tribal Bands across Turtle Island (North America) as well as research from or based in Africa, India, and Antarctica. Although ECR organizers represented a diverse set of backgrounds, collaboration across disciplines, career stage, and experience meant that our presentations were appealing to a broad audience.

From the co-created vision, we clearly described roles, scripts and protocols co-created by all. Transparent, well-described roles were critical in training ECRs effectively while also ensuring an equitable workload throughout the year and across the series. As part of the visioning exercise, ECR organizers came together to brainstorm roles needed for each seminar and panel discussion, including event hosts, chat facilitators, virtual tech set-up, communications, scheduling, and follow-up. To facilitate shared, equitable co-leadership by all ECRs, we tracked participation that ensured every individual should attempt each role at least once. The shared planning documents ensured transparency in tracking previous position-holders so that newcomers to a particular role had access to a greater support network and additional resources should they have questions about their responsibilities. Additionally, each role description included clear timelines with respect to when certain tasks were to be completed, supplemented by the weekly virtual meetings to provide additional feedback and support if required. For example, individuals tasked with the communications role would create a poster using a shared template, and initiate advertising as scheduled, two weeks before the event. Because ECR organizers rotated through roles, having clearly defined responsibilities facilitated easy transition between roles and encouraged novices in each role to engage team members with any questions to better understand tasks. Having ECR organizers participate in co-creating, updating and improving roles each week increased ownership, improved the role itself and reduced the workload in delivering this year-long series.

Embed justice, equity, diversity, inclusion and indigeneity

Diverse, inclusive research communities are more productive, innovative and impactful (Jimenez et al., 2019). We operationalized a commitment to justice, equity, diversity, inclusion and Indigeneity by modelling a more decolonial approach to ECR training. We committed to having open conversations about which experts, perspectives and participation are not commonly represented in academic seminars and sought to ensure they were prioritized and amplified. By design, we sought to harness the rich diversity of expertise and lived experiences represented across the programs, countries and disciplines represented. Faculty mentors intentionally played the role of facilitators, encouraging ECR organizers to take the lead in decision-making. We engaged in layered discussions to explore questions and ideas and encouraged ECRs to mentor one another to generate views and perspectives on ways to move forward collectively. As a starting point, ECRs were introduced to key concepts of conference and seminar organization, including given examples of seminar organization plans from previous years, which prompted thoughtful discussions and debates on how to integrate, acknowledge and amplify different ways of knowing, lived experiences and expertise in a single virtual series. By going virtual, unhindered by the physical limitations of traditional seminars, ECR organizers were able to pursue a diverse, international, and cross-disciplinary suite of expertise to be featured in the series, while also making it possible to consider greater global contexts on issues of sustainability. In the end, the series featured a diverse range of speakers most who self-identified as female and/or BIPOC.

Operationally, we also carefully considered how the seminar series could be delivered in an inclusive manner. We jointly organized all aspects of the series drawing on multiple open-access, cloud, or web-based applications to run the series and prepare forms for the purposes of organizing information from invited speakers, panelists and attendees. These open-access applications were used to run the series to provide optimal planning and organization of each seminar, such as Google Drive (Sheets, Docs, Forms, Slide), Canva, Twitter, and Facebook, to equitably support ECRs and attendees (Halpin and Lockwood, 2019). Additionally, we used applications through our privileged institutional licenses (e.g., Zoom, Microsoft Teams) that made it possible to ensure high productivity and other opportunities during pandemic-related lockdowns (OECD, 2021). Platforms were chosen based on each application’s strengths and weaknesses. For example, Zoom was chosen as the video conferencing tool to display the seminars as it is free, easily accessible, and can bring together users from multiple countries (Chen, 2012). We employed social media to reach a wide audience to promote the series which further allowed us to engage with potential attendees from diverse backgrounds (Chen, 2012). A single open, shared cloud-based workspace (i.e., GoogleSheets) served as the central planning tool with a single planning document that worked effectively as a standard operating protocol (SOP) for the series. A coordinated set of files included a proposed speakers list and a planning spreadsheet for students to sign up for various roles ahead of time (Table 1 ). The SOP contained information and links to the templates required for organizing the seminars; this included a step-by-step guide for seminar hosts, scripts for hosting the seminars, meeting notes, prepared questions, a template for the publicity poster, and pre-prepared tweets for publicizing on social media. It also included links to registration forms that could be updated by whoever held that role for a given seminar. The SOP outlined links to all the documents required for the students to successfully host and coordinate the seminars and was an ideal place where all resources could be kept, updated, and shared with the students.

Table 1.

Roles and role-specific descriptions considered to manage the #GLIERTRUST virtual seminar series. Each role had a minimum of 2 early career researchers (ECRs), with one from each Institution/Program to ensure co-leadership, co-design and co-delivery.

| Role | Description |

|---|---|

| Host(s) | Be the public face and voice of the team for a given seminar. Work from a co-written script, start the seminar with a virtual wave, present the speaker(s), acknowledge key partners, and ask questions to the speaker during the Q&A session, keep to time. During the event, remain in constant communication with the chat facilitators. |

| Technical set-up | Be the technical leads for a given seminar. Carry out technical operations by creating the virtual pre-registration for each seminar, share the talks to the public through social media, be in communication with the Hosts to help prepare for the seminar. Admit and maintain the tally of those who attend each seminar. |

| Communications |

Internal (Scheduling) – Create and post the public registration form to attend the event. Maintain communication with ECRs, faculty and seminar speakers to go over logistics, script and schedule. External (Social Media) – Create graphical content to publish across social networks (e.g., Facebook, Twitter, and websites). |

| Chat facilitator | Track live discussions, take note of questions and transfer relevant information to hosts and seminar speakers. |

| Follow-up | Follow-up emails and comments with the speaker, tally questions and develop a summary of feedback. |

It was important to create an environment that was inclusive and respectful of different schedules and abilities and use the open framework to help mentor ECRs through new, often daunting roles. As graduate students, many were first-time participants in their respective organization and in the production of a seminar series, virtual or otherwise; many had not even visited the physical campus during this time due to pandemic-related lockdowns. This series also required that ECRs take on completely new responsibilities outside of their research. Thus, coordination of the seminars needed to be both collaborative, between experienced and inexperienced ECRs, and easily accessible and not a distraction from their research. To this end, we facilitated brainstorming sessions and ‘dry run’ rehearsals for ECRs to feel more comfortable and confident before going live. Likewise, each individual speaker was sent a standardized form to provide their information including pronouns, preferred photo for posters and amplifications, social media handles and express permission to record and post videos of their event either in part or its entirety. Faculty members ensured equitable distribution of roles, suggesting mentors to pair with novices in each role, and providing the initial scripts or documents upon which ECRs could edit, personalize and update for others to use and contribute to. With each iteration, ECRs became confident in navigating the roles as part of a unified, efficient, and effective team.

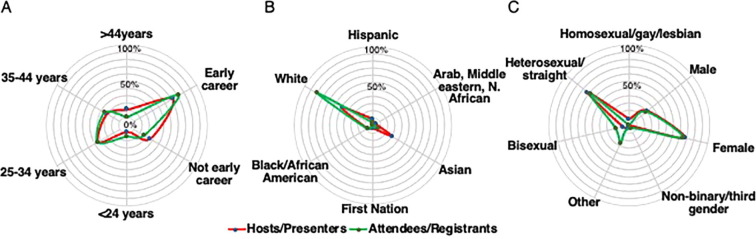

We conducted a post hoc demographic evaluation of hosts, presenters, attendees, and registrants with a survey created through Qualtrics. This survey was used to collect basic demographic information on age, sex, gender, race, ethnicity and whether respondents identified themselves as ECRs. The survey was deployed to all seminar affiliates (n = 451) with 58 respondents, a response rate of 12.8%. Data were pooled into two groups: hosts/presenters and attendees/registrants. Survey data indicate similarities between host/presenters and attendees/registrants, as both groups largely identify as ECRs (Fig. 2 , A), however, the data also reveals that fewer host/presenters identify as white (45%) when compared to the attendee/registrant group (82%) (Fig. 2 , B). With that, these data indicate successful efforts to foster a more diverse environment for ECR hosts and presenters in this seminar series.

Fig. 2.

Visualization of demographic information of GLIER/T-RUST hosts/presenters (red) and attendees/registrants (green) derived from survey data. Survey data is separated by (A) age and self-perception of early career, (B) race and ethnicity, and (C) sex and gender. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Champion co-leadership and peer mentoring

Peer mentored roles provide a template of behavior that offers a model for future interactions and professional networks (Morgenroth et al., 2015). ECR organizers benefited from a peer-to-peer mentorship model, while faculty facilitated collaborations, provided an overarching structure and offered feedback and assistance. For example, ECR organizers took turns as a co-leader of each role required to host a scheduled seminar, while faculty assisted with setting up weekly check-in meetings, providing examples of introductory scripts, and being available to answer questions as needed. To ensure equitable representation and experience across cohorts, one ECR from each program (GLIER, T-RUST) were assigned to and shared a role with a peer. Collectively, ECR organizers and faculty mentors all approached this seminar series with varying familiarity with seminar series, a range of disciplinary backgrounds and skill levels. Each individually brought natural strengths from presentation, writing, communication, technology, or strategic networks to draw on. Co-led roles for each seminar leveraged strengths to ensure that individually and collectively the seminar ran professionally and without technical glitches. The co-leaders were armed with clear descriptions to guide them and with the opportunity to try their role in a virtual rehearsal earlier in the week. ECR co-leads also worked independently on a given task, meeting virtually to discuss ways to accomplish their role(s) effectively. This enabled powerful teamwork across an international boundary, which opened up new networking avenues for ECRs and resumé-relevant, skill-building experience. Co-leading also helped ECR organizers foster critical communication skills, which was deemed important for further graduate school and career-related prospects. This component of the seminar was particularly important for the ECRs during the lengthy pandemic-related period of online learning. ECRs lost more than a year of in-person conferences, presentations, and workshop opportunities thus the collective sentiment among ECR organizers was that having a consistent space to collaborate on new skills, and reach out to scholars they admire, helped make up for some of the lost in-person opportunities due to COVID-19.

Feature cross-disciplinary topics and experts

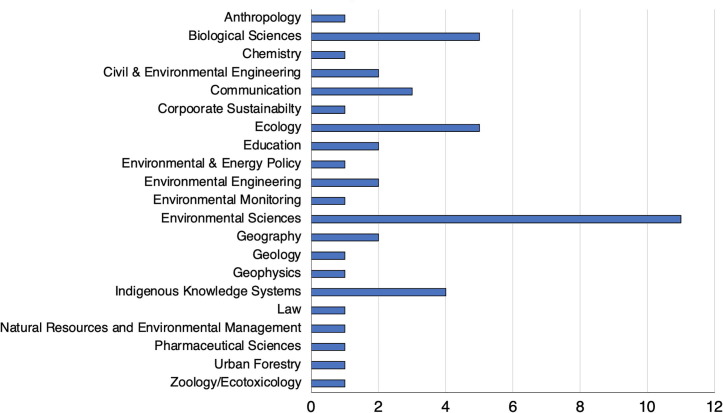

The planning group worked to include a wide-range of seminar topics, seminar styles, and speakers throughout the year, bearing in mind a commitment to challenging academic cultural norms (Stone-Mediatore, 2007). This included hosting seminars that engaged academic pedagogies across all disciplines, as well as ensuring our audience would hear from a range of voices and perspectives, particularly from marginalized groups The group’s commitment to a dynamic seminar series stemmed partly from the cross-disciplinary nature of the group itself as the GLIER and T-RUST programs encompass a wide range of disciplines. ECRs from traditional STEM disciplines such as biology and engineering were represented in equal measure by students in social sciences, including education, anthropology and communication. The groups connected through a commitment to elevating and discussing sustainability issues and learning from the disciplinary differences, particularly engaging research methodologies, questions and collaborations that bridged science and sustainability in the Great Lakes and beyond. As a result, we featured nearly two dozen different disciplines across our speakers (Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 3.

Disciplinary expertise featured by the seminar speakers and panelists in the GLIER T-RUST series.

Furthermore, entering into the 2020–21 academic year, after a summer of COVID-19 shutdowns, widespread racial justice protests worldwide, and an intense election season in the United States, it was imperative to be intentional about using the seminar space to ensure that Black, Indigenous or People of Colour (BIPOC), female-led research, and diverse perspectives were seen and heard. The group engaged as many voices as possible from these groups, and worked to include questions related to social justice in the discussion period when applicable to the seminar topic. Therefore, it was important to capitalize on a shared interest to engage historically marginalized perspectives in academic institutions. Generating unique conversations by pushing the envelope with regard to seminar topics kept ECR organizers engaged while also expanding our audience base. Among the most highly attended panels was Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Indigenous-University relationships. We were fortunate to host Indigenous knowledge holders and scholars from across the Great Lakes basin and Turtle Island/North America. Another well-attended panel series sought to address the complex issue of industrial challenges during times of heightened environmental awareness. Overall, this element of the seminar series was successful in bringing diverse perspectives and their lived experiences to respectfully discuss issues and topics; this provided a meaningful model for ECRs.

By framing the seminar series as an opportunity for training and engaging with ECRs, the speakers and panelists were all encouraged to shorten their seminar to allow for ample time for ECR-focused questions on career pathways, training opportunities and general life advice. An intentional pause in between segments allowed attendees to leave however most attendees stayed for the full hour. This informal, sometimes unrecorded element of the seminar was ECR driven and was included in the early discussions with all speakers, followed with pre-prepared questions so that all invited guests were provided the opportunity to reflect in advance. This was perhaps the highlight of the series for ECRs as they were able to engage on a personal level with experts they looked up to and sought to connect with professionally.

Maximize outreach and amplification

Engaging in this collaboration as a learning opportunity was intentional, as was an interest in tracking impact and outreach as relative metrics of success. Traditionally, the success of an academic seminar series is largely attributed to the number of chairs filled and level of engagement with a given speaker. However, a virtual setting allowed for a more inclusive approach to participation. We maximized the ability for speakers to connect with ECRs by shortening the traditional seminar length (i.e., 1 h shortened to 30 min) to make way for equal parts seminar and open discussion. Further, we tracked the number of registrants and attendees at each event. We averaged 60 attendees per event with no fewer than 43 attendees at a single event. Our most well attended event was the Traditional Ecological Knowledge Panel with 110 attendees. We attributed successful attendance to be partly due to a pre-registration feature for all seminars and the option to register for all talks. To reciprocate knowledge exchange and fellowship, a follow-up email was sent to speakers in gratitude, and to share follow-up questions and feedback. Moreover, the broad outreach was in part made possible by amplifying the virtual seminars via social media platforms. It was valuable to track the impact of the seminar series to help ECR organizers reflect on which topics resonated with their academic communities and the public.

In going virtual we wanted to ensure that anyone, anywhere could attend. Creating a virtual seminar series allowed for greater participation opportunities for both attendance and invited speakers from across the globe, including greater accessibility for people physically unable to travel, or with limited access to university buildings for seminars. Moreover, the pandemic has required a historic level of adjustment in the lives of ECRs. However, through this series we have harnessed the benefits to this new realm of online learning. Ensuring that the seminar series was accessible was a top priority and approaches we used were complemented by a growth in viewers. Attendees spanned from across Canada, United States, Turkey, South Africa, Indonesia, India, United Kingdom, Sri Lanka, and Pakistan. As the seminar series progressed, the number of participants also increased. To ensure asynchronous and ongoing engagement, we created a public YouTube channel (http://tiny.cc/gliertrustvirtual) for the seminar series to increase and maintain ongoing accessibility to the series which included the option of closed captioning. The YouTube channel will continue to remain available as a future resource for all.

Showcase early career researchers

We sought to foster and create a welcoming environment. After more than a year of virtual programming, research, and teaching, we understood and empathized with the genuine fatigue experienced across the research community. Thus, ECR organizers strived to create a welcoming environment for the seminar speakers and panelists especially when most are accustomed to having video feeds turned off. Many could relate and came to expect a sea of black screens and names displayed in such settings. A simple but highly effective way to foster an inclusive environment was to invite all audience members to turn on their video for a quick wave and the inclusion of preferred pronouns alongside their on-line names. This is not something that was explicitly asked of the students but the faculty led by example and soon more and more participants were found to follow suit. In addition, ECR organizers serving as co-hosts for a given event were encouraged to open each gathering with a simple but meaningful land acknowledgment of Tribes and First Nations and the traditional lands upon which our campuses reside. Again, with each iteration, ECRs became more comfortable and confident in intentionally fostering a welcoming environment for those who attended. Through these small actions, ECR organizers and participants alike commented on feeling welcome, and presenters commented on being happily surprised and shared their appreciation for such a meaningful moment and the ability to see the variety of people who attended.

Transformative change in environmental research and sustainability: Training and empowering future leaders

An ECR-led series such as the one we delivered created an environment where the ECR organizers relied on each other to ensure a successful outcome and fostered numerous and ongoing opportunities for peer-mentorship. ECR organizers were responsible for every aspect of planning and implementation leading to a true sense of transformative change in their training as future leaders (Fig. 1). In contrast, a traditional seminar series often follows the same format: faculty members organize the seminar series and student engagement is often limited to the invitation of a few speakers and occasionally to assist with hosting. Seldom are university seminars series supported and run by the ECRs, and even less by ECRs in a collaborative fashion across disciplines and countries.

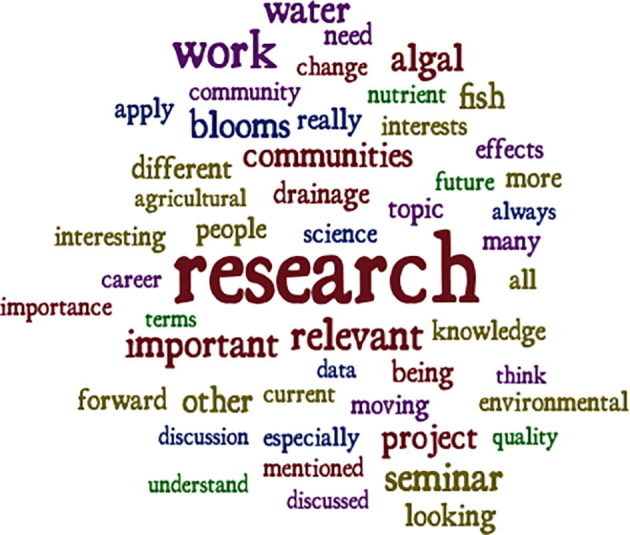

Peer-mentoring was a critical opportunity that ECR organizers really valued. Consistent with other studies, our collective experience was that peer-mentoring improved a number of career-relevant skills: confidence, communication, problem-solving skills, and other aspects of graduate student research life (Weaver et al., 2021). The unanticipated degree of personal and emotional support was particularly valuable during the pandemic. Moreover, we found dialogue through peer feedback as a critical aspect for learning (Gut et al., 2014, Zhu and Carless, 2018), particularly as ECRs seeking to improve professionally. Thus, a consistent focus throughout our series was the importance of supporting ECR organizers in taking lead roles and providing ample opportunities for peers to provide input and suggestions for improvement. ECR organizers felt they were provided excellent opportunities for professional development and to engage in both formal and informal networking with professionals in their field(s) of interest. This helped students hone professional development skills and had the opportunity to observe and learn from diverse topics and individuals featured in the series. Co-creation of panel scripts and advertising such as drafting email announcements, social media posts and flyers facilitated collaboration and “low-stakes” opportunities for ECR organizers to practice, receive feedback or ask questions as they moved through a real professional setting. To the question: “In what way was this speaker, topic and discussion relevant to you? How can you apply this seminar to your work moving forward”, ECR organizers submitted reflections (n = 71) which confirmed thematic elements of connection of the seminar series to their own research (Fig. 4 ).

Fig. 4.

Thematic word cloud generated from anonymous individual reflections in response to the question “In what way was this speaker, topic and discussion relevant to you? How can you apply this seminar to your work moving forward?” (n = 71). Words that were mentioned most frequently appear more prominently and colours are used to distinguish words from one another.

Finally, it was important for us to end the series by giving ECRs their turn to shine. Seminars and panels are undoubtedly a great way for anyone at any stage of their career to connect with others by providing a platform to share ideas and showcase their own research. For ECRs, these opportunities are even more valuable as they seek to establish themselves in the academic community. The #GLIERTRUSTvirtual series concluded with a showcase of the ECRs in both programs. ECRs were invited to submit abstracts for talks to present as a 3-minute lightning talk. This end-of-year showcase event was open to all ECRs from both programs and all previous seminar speakers, faculty and the public were invited to attend. ECRs were given centre stage to share their research and also fully run all elements of the event from start to finish. The three minute format, designed as an “elevator pitch”, challenged students to effectively explain their projects and emphasize their importance in relation to environmental sustainability to the broader community. Administrators from both universities provided welcoming remarks and faculty mentors gave a short plenary showcasing our approach for the series. Garnering one of the highest attendances of the whole series, it was clear validation for the ECR organizers that their year-long efforts did not go unnoticed.

Conclusions

ECRs entering the research community throughout and beyond this pandemic are in a critical phase of their career development, and yet ECRs are also often touted as the source of inspiration, innovation and are essential to facing complex environmental sustainability challenges (Lim et al., 2017). However, one of the top disruptions for ECRs has been the inability to attend conferences and engage in key training opportunities (Herman et al., 2021), which ultimately compound negative impacts on their research trajectory and impact. With the disruption of the pandemic came the opportunity to reset, re-think and re-formulate traditional modalities of training and networking to intentionally serve ECRs at a critical time. In response to calls for senior scientists and those in positions of privilege to support ECRs during such a challenging time (Maas et al., 2020), key faculty mentors (Febria, Mundle and Kashian) found great support in aligning efforts to empower ECRs during this difficult time. Recognizing that the immediate impacts on marginalized members of the research community, including women, parents (Fulweiler et al., 2021, Gewin, 2020, Kramer, 2020) and underrepresented groups (Jimenez et al., 2019), we took this opportunity to demonstrate how individual labs, departments, institutions, and funding agencies can take a wide range of measures to help curb losses in ECR momentum and training opportunities.

Among research institutions and funding agencies, the effective training and advancement of ECRs is an important hallmark of success, excellence, and positive societal impact. By taking on diverse leadership roles, students demonstrated to their faculty mentors that they were capable of collaborating with others, even people we have never met. We demonstrated to ourselves that we were capable of working in a team environment to accomplish a common goal and taking turns to lead. The co-host role specifically required a great deal of interaction with the speakers, an opportunity none of the ECRs have attempted before. The varied roles offered an opportunity to be professional and are often those experiences that employers often do not see on a job application. The ECRs reflected that the soft skills learned through this experience were as important – if not more – than technical skills learned in the same time period. The overall experience of running a virtual seminar series was an effective way of showcasing ECRs and the success of the seminar speaks volumes to the skillset of those involved and was appreciated by all those who attended. Re-envisioning the purpose, scope, and mode of delivery for the traditional seminar series was one opportunity for positive change within our research communities that may just be one of few adjustments that we hope will remain to help amplify research excellence, support professional development and ensure lasting, positive impact and connections in our local and global research ecosystem.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank all the panelists and guest seminar speakers who not only shared their expertise with us but also provided valuable advice for the betterment of our careers and training (in alphabetical order): Genevieve Ali, Myrle Ballard, Paul Bauman, Erin Dunlop, Valoree Gagnon, Helen Jarvie, Supriyo Kumar Das, Patrick Doran, Pauline Gerrard, Donna Givens, Clint Jacobs, Connie Lilley, Carol Miller, Bridie McGreavy, Rahul Mitra, Jalonne Newsome-White, Justin Onwenu, Court Sandau, Claire Sanders, Janani Sivarajah, Katie Stammler, Ed Verhamme, Paul Weidman, Dilber Yunus. We also thank the University of Windsor School of Environment ECRs who also participated in the organization of the first half of the series (in alphabetical order): Matt Anderson, Jenny Gharib, Jamie Lilley, Don Uzarski, and T-RUST ECR Brendan O’Leary. Wayne State University authors were in part supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 1735038. University of Windsor students enrolled in the GLIER graduate program participated in this as part of their graduate course GLIE8500 – Multidisciplinary Graduate Course at GLIER or School of Environment graduate programs. We thank GLIER, School of the Environment, and the Faculty of Science for support of the series.

Communicated by J. Val Klump

References

- Chen G.-M. The impact of new media on intercultural communication in global context. China Media Res. 2012;8(2):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Fulweiler R.W., Davies S.W., Biddle J.F., Burgin A.J., Cooperdock E.H.G., Hanley T.C., Kenkel C.D., Marcarelli A.M., Matassa C.M., Mayo T.L., Santiago-Vàzquez L.Z., Traylor-Knowles N., Ziegler M. Rebuild the Academy: Supporting academic mothers during COVID-19 and beyond. PLoS Biol. 2021;19 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3001100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gewin V. The career cost of COVID-19 to female researchers, and how science should respond. Nature. 2020;583:867–869. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-02183-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gut D.M., Beam P.C., Henning J.E., Cochran D.C., Knight R.T. Teachers’ Perceptions of their Mentoring Role in Three Different Clinical Settings: Student Teaching, Early Field Experiences, and Entry Year Teaching. Mentor. Tutor.: Partnership Learn. 2014;22:240–263. doi: 10.1080/13611267.2014.926664. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Halpin P.A., Lockwood M.K.K. The use of Twitter and Zoom videoconferencing in healthcare professions seminar course benefits students at a commuter college. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 2019;43:246–249. doi: 10.1152/advan.00017.2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman, E., Nicholas, D., Watkinson, A., Rodríguez-Bravo, B., Abrizah, A., Boukacem-Zeghmouri, C., Jamali, H.R., Sims, D., Allard, S., Tenopir, C., Xu, J., Świgoń, M., Serbina, G., Cannon, L.P., 2021. The impact of the pandemic on early career researchers: what we already know from the internationally published literature [WWW Document]. Profesional de la Información. URL https://revista.profesionaldelainformacion.com/index.php/EPI/article/view/86357 (Accessed 7 April 2022).

- Jimenez M.F., Laverty T.M., Bombaci S.P., Wilkins K., Bennett D.E., Pejchar L. Underrepresented faculty play a disproportionate role in advancing diversity and inclusion. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2019;3:1030–1033. doi: 10.1038/s41559-019-0911-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, J., (2020). Women in Science May Suffer Lasting Career Damage from COVID-19. Scientific American. URL: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/women-in-science-may-suffer-lasting-career-damage-from-covid-19/.

- Lim M., Lynch A.J., Fernández-Llamazares Á., Balint L., Basher Z., Chan I., Jaureguiberry P., Mohamed A., Mwampamba T.H., Palomo I., Pliscoff P., Salimov R.A., Samakov A., Selomane O., Shrestha U.B., Sidorovich A.A. Early-career experts essential for planetary sustainability. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2017;29:151–157. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2018.02.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maas B., Grogan K.E., Chirango Y., Harris N., Liévano-Latorre L.F., McGuire K.L., Moore A.C., Ocampo-Ariza C., Palta M.M., Perfecto I., Primack R.B., Rowell K., Sales L., Santos-Silva R., Silva R.A., Sterling E.J., Vieira R.R.S., Wyborn C., Toomey A. Academic leaders must support inclusive scientific communities during COVID-19. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2020;4:997–998. doi: 10.1038/s41559-020-1233-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenroth T., Ryan M.K., Peters K. The motivational theory of role modeling: How role models influence role aspirants’ goals. Rev. General Psychol. 2015;19(4):465–483. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2021). Harnessing the productivity benefits of online platforms: Background paper. OECD Publishing, Paris. URL: https://www.oecd.org/global-forum-productivity/events/Harnessing-the-productivity-benefits-of-online-platforms.pdf (Accessed 3 March 2022).

- Powell K. These labs are remarkably diverse — here’s why they’re winning at science. Nature. 2018;558:19–22. doi: 10.1038/d41586-018-05316-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone-Mediatore S. Challenging Academic Norms: An Epistemology for Feminist and Multicultural Classrooms. NWSA J. 2007;19(2):55–78. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40071205 [Google Scholar]

- Swartz T.H., Palermo A.-G.-S., Masur S.K., Aberg J.A. The Science and Value of Diversity: Closing the Gaps in Our Understanding of Inclusion and Diversity. J. Infect. Dis. 2019;220:S33–S41. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiz174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver J.C., Bertelsen C.D., Dendinger G.R. Career-related peer mentoring: can it help with student development? Mentor. Tutor.: Partnership Learn. 2021;29:238–256. doi: 10.1080/13611267.2021.1912900. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Q., Carless D. Dialogue within peer feedback processes: clarification and negotiation of meaning. Higher Educ. Res. Develop. 2018;37:883–897. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2018.1446417. [DOI] [Google Scholar]