Abstract

We recently reported that Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes (IRBCs) can adhere to hyaluronic acid (HA), which appears to be a receptor, in addition to chondroitin sulfate A (CSA), for parasite sequestration in the placenta. Further investigations of the nature and specificity of this interaction indicate that HA oligosaccharide fragments competitively inhibit parasite adhesion to immobilized purified HA in a size-dependent manner, with dodecasaccharides being the minimum size for maximum inhibition. Rigorously purified and structurally defined HA dodecasaccharides, free of contamination by CSA or other glycosaminoglycans, effectively inhibited IRBC adhesion to HA but not CSA, providing compelling evidence of a specific interaction between IRBCs and HA.

A characteristic of infection with the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum is the ability of parasite-infected erythrocytes (IRBCs) to adhere to host endothelial cells and accumulate in various organs. During pregnancy, the accumulation of IRBCs in the placenta is a key feature of infection and is associated with adverse outcomes and excess perinatal and maternal mortality (6, 18). Studies in Africa suggest that sequestration of IRBCs in the placenta is mediated in part by adhesion of parasites to the glycosaminoglycan (GAG) chondroitin sulfate A (CSA) present on syncytiotrophoblasts lining the placental blood spaces (2, 11).

We have recently reported that hyaluronic acid (HA) can also support the adhesion of IRBCs in vitro and appears to be an additional receptor for parasite sequestration in the placenta (4). HA is nonsulfated and is the simplest member of the GAG family composed of repeating disaccharide units, -4GlcAβ1-3GlcNAcβ1-, in a linear chain that varies in size from 2,000 to 25,000 disaccharide units. It has been identified on syncytiotrophoblasts (17, 28), and we found that most parasite isolates from infected placentas bound to immobilized HA, whereas isolates from the peripheral blood bound to a lesser extent (4). HA is also present on the surfaces of microvascular endothelial cells (19), raising the possibility that it acts as a receptor for parasite sequestration in other organs.

To further investigate the nature and specificity of the interaction of HA with IRBCs, we generated oligosaccharide fragments, including high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)-purified and structurally defined dodecasaccharides, and examined their abilities to competitively inhibit parasite adhesion to immobilized HA. Some HA preparations can be contaminated with other GAGs, such as CSs, and it was therefore important to exclude the possibility that the adhesion observed could be explained by such contaminants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Partial depolymerization of HA.

HA (from bovine vitreous humor; Sigma) (HA-BVH) was partially depolymerized by controlled digestion with either testicular hyaluronidase (EC 3.2.1.35; from bovine testes; Sigma) or hyaluronate lyase (EC 4.2.2.1; from Streptomyces hyalurolyticus; Sigma). Testicular hyaluronidase digestion was carried out with 100 mg of HA and 4 mg of hyaluronidase at 37°C for 20 h in 10 ml of sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.0), as described previously (4). For the lyase digestion, 55 mg of HA and 500 U of enzyme were dissolved in 6 ml of 50 mM Na phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) containing 100 mM NaCl. Digestion was performed at 37°C and monitored by UV absorption at 232 nm (8).

Separation and purification of HA oligosaccharides.

The reaction mixtures were fractionated on a Bio-Gel P-6 column (1.6 by 90 cm) (7). The major fractions pooled and analyzed by electrospray mass spectrometry (ESMS) (9) were the tetra- to hexadecasaccharides obtained from hyaluronidase digestion, designated A4 to A16, and di- to hexadecasaccharides obtained from lyase digestion, designated B2 to B16.

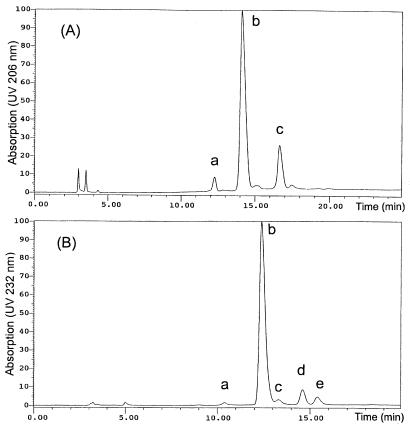

Dodecasaccharide fraction A12 was subfractionated on an amino column (Hypersil APS-2; 4.6 by 250 mm). A linear gradient of NaH2PO4 (solvent A, 0.1 M, and solvent B, 1.0 M; 0 to 25% B in 25 min) was used to elute the oligosaccharides at a flow rate of 1 ml/min with detection at UV 206 nm. For dodecasaccharide fraction B12, a strong anion-exchange column (Spherisorb S5 SAX) was used with a linear gradient of NaCl (solvent A, 0.2 M, and solvent B, 1.5 M; pH 3.5; 0 to 15% B in 20 min) at a flow rate of 1 ml/min and with detection at UV 232 nm. The main dodecasaccharide fractions A12-b and B12-b (Fig. 1) were collected, desalted, and lyophilized. Quantitation of HA was carried out by carbazole assay (4, 5) for glucuronic acid content.

FIG. 1.

HPLC profiles of HA dodecasaccharides A12 (A) and B12 (B).

ESMS of HA oligosaccharides.

ESMS was carried out on a Q-T of mass spectrometer (Micromass UK Ltd., Wythenshaw, England) in the negative-ion mode (9). A cone voltage of 20 V was used, and the capillary voltage was kept at 4,000 V. As a solvent, ACN-water (1:1) was delivered into the electrospray source by a syringe pump at a flow rate of 5 μl/min. Sample solution (5 μl; 10 to 20 pmol/μl) was injected with a flow injector. Full-scan spectra were acquired over a mass range of 200 to 1,200 Da at 1.5 s/scan and processed and transformed into mass values using the MassLynx data system.

NMR spectroscopy.

Dodecasaccharide fractions A12-b and B12-b obtained from HPLC purification were dissolved in 500 μl of D2O (100.0 atom% D; Aldrich), and acetone was used as an internal standard (δ, 2.225 ppm). One-dimensional (1D) 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were recorded at 20°C with 3,000-Hz sweep widths on a Varian UNITY-600, with 256 scans for A12-b and 64 scans for B12-b, and multiplied by a shifted Gaussian window function prior to Fourier transformation.

Parasite cultures and adhesion assays.

Parasites were maintained in continuous culture as previously described (26) and synchronized every 1 to 2 weeks by sorbitol lysis (15). The P. falciparum isolate CS2 (4) was derived from a clone of Brazilian isolate ItGF6 by selection for adhesion to Chinese hamster ovary cells five times, followed by two cycles of selection to immobilized purified CSA (23).

Adhesion assays were performed using P. falciparum trophozoite IRBCs as previously described (2, 4) at 3 to 5% parasitemia and 0.25 to 0.5% haematocrit. GAGs (all from Sigma) were immobilized onto plastic petri dishes (Falcon 1058; Becton Dickinson, Lincoln Park, N.J.) for 24 h at 4°C. Coating concentrations (in phosphate-buffered saline) were 50 μg/ml with HA-BVH and 5 μg/ml for HA from human umbilical cord (HA-HUC) and CSA from bovine trachea. Prior to performing the assay, the plates were blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin in phosphate-buffered saline. Subsequently, receptor spots were overlaid with parasite suspensions for 20 min at 37°C. Unbound cells were removed by gentle washing with RPMI-HEPES, pH 6.8. Bound cells were fixed with glutaraldehyde, stained with Giemsa stain, and counted by light microscopy. Oligosaccharide fragments were tested for inhibition of adhesion by incubation with parasite suspensions at 200 μg/ml (unless otherwise stated) for 20 min at 37°C prior to adhesion assays.

RESULTS

Inhibition of adhesion with oligosaccharide fragments.

P. falciparum CS2 isolate IRBCs adhere at high levels to immobilized HA and CSA polysaccharides but not to related carbohydrates and GAGs (4). CS2 IRBCs bound at high levels to HA-BVH, as previously reported (4), which is not known to be contaminated by other GAGs (12, 24). Our analysis of HA-BVH by high-resolution NMR gave no detectable signals from CSA or other GAGs (data not shown).

Oligosaccharide fragments of HA ranging from 4 to 16 monosaccharide units in length (A4 to A16), derived from hyaluronidase digests of HA-BVH, were tested as competitive inhibitors of CS2 IRBC adhesion to immobilized HA-BVH (Table 1). The minimum-length fragment causing near-maximum inhibition of adhesion to HA was the dodecasaccharide. Substantial (≥50%) inhibition of adhesion was also observed with the octa- and decasaccharide fractions. Adhesion to CSA was not significantly inhibited by the HA oligosaccharide fragments.

TABLE 1.

Size-dependent inhibition of adhesion to HA by oligosaccharide fragments A4 to A16 and polysaccharidea

| HA saccharide | Inhibition of adhesionb |

|---|---|

| A4 (4-mer) | 21.9 ± 18.3 |

| A6 (6-mer) | 33.5 ± 11.0 |

| A8 (8-mer) | 50.2 ± 3.0 |

| A10 (10-mer) | 65.3 ± 13.9 |

| A12 (12-mer) | 84.3 ± 5.4 |

| A14 (14-mer) | 86.4 ± 5.4 |

| A16 (16-mer) | 87.3 ± 4.2 |

| Polysaccharide | 99.5 ± 0.2 |

HA oligosaccharides A4 to A16 were isolated from testicular hyaluronidase digests of HA-BVH polysaccharide. All saccharides were tested at 200 μg/ml for inhibition of adhesion of CS2 IRBCs to immobilized HA-BVH.

Data are expressed as percentages of control (mean ± standard error of the mean for multiple experiments).

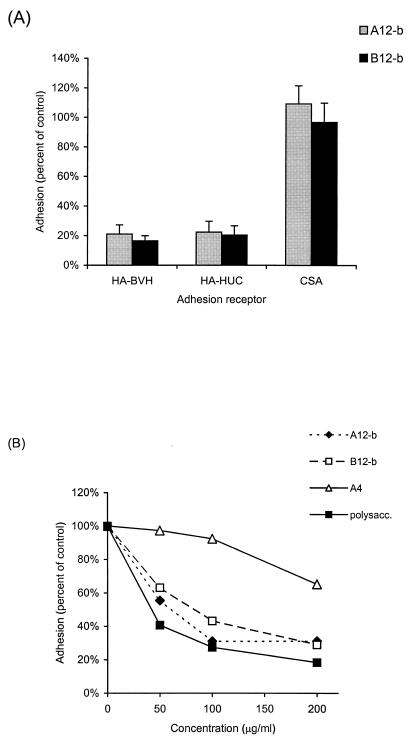

The HPLC-purified and structurally defined dodecasaccharides A12-b and B12-b (Fig. 1) (see below) effectively inhibited adhesion (Fig. 2A) to immobilized HA-BVH and HA-HUC, which contains small amounts of CS (supplier's information). Inhibitions of adhesion by the dodecasaccharides obtained from either hyaluronidase (A12-b) or lyase (B12-b) digestion were very similar, and both inhibited adhesion to HA-BVH and HA-HUC. In contrast, there was no significant inhibition of adhesion to CSA.

FIG. 2.

Inhibition of adhesion of CS2 IRBCs by HA oligosaccharides. (A) Dodecasaccharides A12-b (from testicular hyaluronidase digests) and B12-b (from Streptomyces hyaluronate lyase digests) effectively inhibited adhesion to immobilized HA-BVH or HA-HUC, but not CSA, at 200 μg/ml. The error bars indicate standard deviation. (B) Adhesion to HA was effectively inhibited by increasing concentrations of HA polysaccharide (polysacc.) or dodecasaccharides A12-b and B12-b but not by tetrasaccharide A4 (P < 0.01). Differences in inhibitory activity among polysaccharide, A12-b, and B12-b were of borderline statistical significance.

Dodecasaccharides A12-b and B12-b and HA polysaccharides effectively inhibited adhesion to HA in a dose-dependent manner that was near maximal at 100 μg/ml (Fig. 2B), whereas tetrasaccharides (A4) resulted in much less inhibition (see Fig. 4) at the same concentrations (P < 0.01; Wilcoxon's signed-rank sum test). Polysaccharides generally inhibited adhesion more effectively than the dodecasaccharides A12-b and B12-b, but the differences were small and of borderline statistical significance.

FIG. 4.

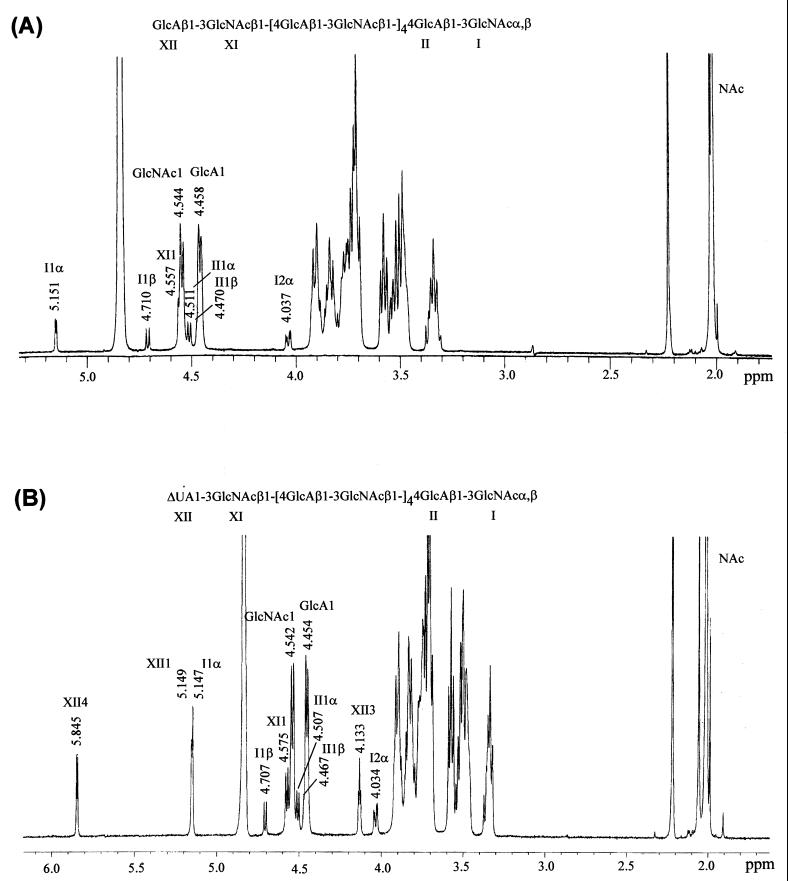

1D 1H NMR spectra of A12-b (A) and B12-b (B). Anomeric and other structural reporter proton resonances are indicated by roman numerals corresponding to the position of the residue in the sequence as shown in the formulae.

Purification and structural determination of HA dodecasaccharides.

ESMS analysis of the oligosaccharide fragments obtained from digestion with hyaluronidase, and used as competitive inhibitors of IE adhesion (Table 1), revealed a general composition of UAn · HexNAcn, where n = 2 to 8 for A4 to A16, respectively (data not shown). Each fraction, particularly in the higher oligomer fractions, contained some minor overlapping components as detected by ESMS and HPLC. The molecular masses detected in ESMS indicated no sulfated oligosaccharides from CS (3) or other GAGs in any of the fractions.

In the case of dodecasaccharide A12, the mass spectrum (not shown) showed a main component with a molecular mass of 2,293.0 Da and a deduced composition of UA6.HexNAc6, together with tetradeca- and decasaccharide as the minor components. The minor components were also observed in HPLC (Fig. 1A), (peaks a and c) and accounted for 23% of the total oligosaccharides in A12 based on absorption of UV at 206 nm.

The major component of dodecasaccharide fraction B12, isolated from lyase digests, had a mass of 2,275.1 Da (data not shown), corresponding to dodecasaccharides with a 4,5-unsaturated uronic acid (ΔUA) at the nonreducing terminus (ΔUA.UA5.HexNAc6) generated by the lyase. In addition to the overlapping components tetradeca- and decasaccharide, two other unusual minor components, HA trideca- and undecasaccharide, were also observed (21). The minor components in B12 (Fig. 1B, peaks a, c, d, and e) amounted to 15% of the total oligosaccharides in B12, based on UV absorption at 232 nm.

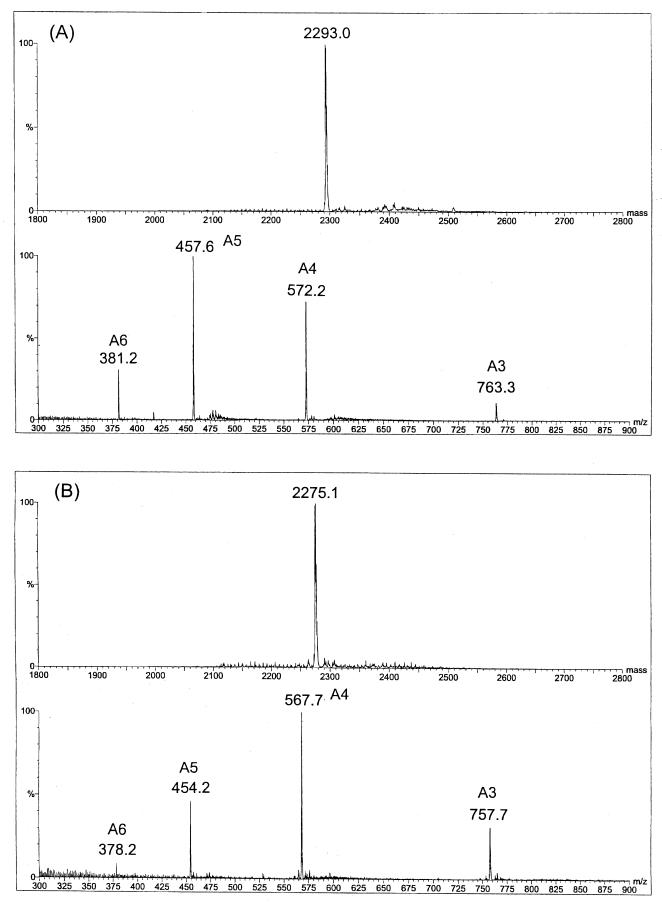

Following purification of the dodecasaccharides by HPLC, the mass spectra of A12-b and B12-b (Fig. 3) clearly indicated a single component, corresponding to HA dodecamers, in both preparations (2,293.0 and 2,275.1 Da, respectively). Similarly, the 1H NMR spectra of these dodecasaccharides further substantiated their purity, as 1H resonances typical of other GAGs (13) were not observed (Fig. 4). The 1D spectrum of A12-b and the assignments of anomeric and other structural reporter group resonances are shown in Fig. 4A. 1H resonances of the terminal disaccharide units and the chemical shift of H2 of GlcNAc residue I of the α-anomer agree closely with published data for an HA tetrasaccharide (16, 30) and octasaccharide (14). The anomeric proton resonances of the internal GlcA residues IV, VI, VIII, and X appear at the same chemical shift at 4.458 ppm. This is also the case for the anomeric proton resonances (4.544 ppm) for the internal GlcNAc residues III, V, VII, and IX, and the anomeric shifts of both residue types are identical to those reported for HA octasaccharide (14). The major differences in the 1H NMR spectrum of B12-b (Fig. 4B) compared to that of A12-b are the unique resonances at 5.854 and 5.149 ppm assigned to H4 and H1 of ΔUA, respectively (8). The anomeric proton of GlcNAc XI is shifted slightly downfield at 4.575 ppm compared to A12-b (GlcNAc XI H1, 4.557 ppm), due to the adjacent ΔUA residue. 1H chemical shifts of other anomeric proton resonances and the chemical shift of GlcNAc H2 of residue I of the α-anomer are identical to those of A12-b.

FIG. 3.

Negative-ion electrospray mass spectra of HPLC-purified dodecasaccharides A12-b (A) and B12-b (B). The acquired spectra showing multiply charged molecular species (A3 to A6, denoting three to six negative charges, respectively) are shown at the bottom of each panel, and transformed spectra showing the molecular mass are shown at the top of each panel.

DISCUSSION

Our results show an increase in the adhesion inhibition activity of HA oligosaccharides with chain length, the dodecasaccharide being the minimum size fragment giving maximum inhibition of IRBC adhesion to immobilized HA. This is similar to our findings with CSA, in which a tetradecasaccharide fraction was required for maximum inhibition of parasite adhesion (3), and to the findings of other studies on protein-binding interactions with HA (29) or heparan sulfate (31). Similarly, dodecasaccharides of heparan sulfate were recently reported to be the minimum size for effective inhibition of P. falciparum adhesion to uninfected erythrocytes in the formation of erythrocyte rosettes (1). Carbohydrate-protein interactions are generally weak and are enhanced by the cooperative effect of multivalent binding sites, which may explain the apparent requirement for longer-chain structures of GAGs for parasite binding.

In this study, we have excluded the possibility that IRBCs could be adhering to CS or other GAG contaminants in our assays rather than to HA. We first established that IRBCs can adhere at high levels to HA-BVH purified by strong anion-exchange chromatography (supplier's information). By our analysis, there was no detectable CS in this preparation, consistent with the findings of others (12, 24). Furthermore, dodecasaccharides purified by HPLC effectively inhibited adhesion of IRBCs to immobilized HA but not to CSA, and these were shown to contain no detectable CS or other GAGs. The generation of dodecamer fragments using HA lyase excluded any possible copurification of other GAG dodecamers, as this enzyme specifically degrades HA (20). Adhesion to HA-HUC was also inhibited by the structurally defined dodecasaccharides, suggesting that IRBCs are not binding to the CS contaminant in that preparation but are interacting specifically with HA. The isolate used in this study, CS2, demonstrates dual specificity for adhesion to both HA and CSA. Inhibition by oligosaccharides of adhesion to HA, but not to CSA, together with our previous finding (4) that trypsin cleavage of CS2 IRBC surface proteins abolished adhesion to HA but not to CSA, suggests the presence of separate binding sites or ligands for adhesion to HA and to CSA.

P. falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein-1 (PfEMP1) has been identified as the parasite protein mediating adhesion of IRBCs to CSA (22), heparan sulfate (1, 10), and other host molecules. It is not known if PfEMP1 is involved in binding to HA, but the structural variation of this protein, which is encoded by a multigene family termed var (25, 27), may well be capable of accommodating HA on a domain of PfEMP1 different or modified from that for CSA binding.

In conclusion, these studies provide further evidence supporting a specific interaction between P. falciparum IRBCs and HA and suggest that the minimum parasite-adhesive motif of HA is a dodecamer sequence. A detailed understanding of the molecular basis of parasite sequestration in various organs, such as the placenta, may aid in the development of novel preventative or therapeutic strategies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Glycosciences Laboratory is supported by a program grant (G9601454) from the United Kingdom Medical Research Council, and the Division of Infection and Immunity is supported by grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barragan A, Fernandez V, Chen Q, von Euler A, Wahlgren M, Spillmann D. The duffy-binding-like domain 1 of Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 (PfEMP1) is a heparan sulfate ligand that requires 12 mers for binding. Blood. 2000;95:3594–3599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beeson J G, Brown G V, Molyneux M E, Mhango C, Dzinjalamala F, Rogerson S J. Plasmodium falciparum isolates from infected pregnant women and children are associated with distinct adhesive and antigenic properties. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:464–472. doi: 10.1086/314899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beeson J G, Chai W, Rogerson S J, Lawson A M, Brown G V. Inhibition of binding of malaria-infected erythrocytes by a tetradecasaccharide fraction from chondroitin sulfate A. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3397–3402. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.7.3397-3402.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beeson J G, Rogerson S J, Cooke B M, Reeder J C, Chai W G, Lawson A M, Molyneux M E, Brown G V. Adhesion of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes to hyaluronic acid in placental malaria. Nat Med. 2000;6:86–90. doi: 10.1038/71582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bitter T, Muir H M. A modified uronic acid carbazole reaction. Anal Biochem. 1962;4:330–334. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(62)90095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brabin B J. An analysis of malaria in pregnancy in Africa. Bull W H O. 1983;61:1005–1016. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chai W, Kogelberg H, Lawson A M. Generation and structural characterization of a range of unmodified chondroitin sulfate oligosaccharide fragments. Anal Biochem. 1996;237:88–102. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chai W, Lawson A M, Gradwell M J, Kogelberg H. Structural characterisation of two hexasaccharides and an octasaccharide from chondroitin sulphate C containing the unusual sequence (4-sulpho)-N-acetylgalactosamine β1-4-(2-sulpho)-glucuronic acid β1-3-(6-sulpho)-N-acetylgalactosamine. Eur J Biochem. 1998;251:114–121. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2510114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chai W, Luo J, Lim C K, Lawson A M. Characterization of heparin oligosaccharide mixtures as ammonium salts using electrospray mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 1998;70:2060–2066. doi: 10.1021/ac9712761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen Q, Barragan A, Fernandez V, Sundstrom A, Schlichtherle M, Sahlen A, Carlson J, Datta S, Wahlgren M. Identification of Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 (PfEMP1) as the rosetting ligand of the malaria parasite P. falciparum. J Exp Med. 1998;187:15–23. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fried M, Duffy P E. Adherence of Plasmodium falciparum to chondroitin sulfate A in the human placenta. Science. 1996;272:1502–1504. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5267.1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grimshaw J, Kane A, Trocha-Grimshaw J, Douglas A, Chakravarthy U, Archer D. Quantitative analysis of hyaluronan in vitreous humor using capillary electrophoresis. Electrophoresis. 1994;15:936–940. doi: 10.1002/elps.11501501137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holm K R, Perlin A S. Nuclear magnetic spectra of heparin in admixture with dermatan sulfate and other glycosaminoglycans. 2-D spectra of the chondroitin sulfates. Carbohydr Res. 1989;186:301–312. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(89)84044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holmbeck S M, Petillo P A, Lerner L E. The solution conformation of hyaluronan: a combined NMR and molecular dynamics study. Biochemistry. 1994;33:14246–14255. doi: 10.1021/bi00251a037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lambros C, Vanderberg J P. Synchronization of Plasmodium falciparum erythrocytic stages in culture. J Parasitol. 1979;65:418–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Livant P, Roden L, Krishna N R. NMR studies of a tetrasaccharide from hyaluronic acid. Carbohydr Res. 1992;237:271–281. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(92)84249-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin B J, Spicer S S, Smythe N M. Cytochemical studies of the maternal surface of the syncytiotrophoblast of human early and term placenta. Anat Rec. 1973;178:769–786. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091780408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McGregor I A, Wilson M E, Billewicz W Z. Malaria infection of the placenta in The Gambia, West Africa; its incidence and relationship to stillbirth, birthweight and placental weight. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1983;77:232–244. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(83)90081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mohamadzadeh M, DeGrendele H, Arizpe H, Estess P, Siegelman M. Proinflammatory stimuli regulate endothelial hyaluronan expression and CD44/HA-dependent primary adhesion. J Clin Investig. 1998;101:97–108. doi: 10.1172/JCI1604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohya T, Kaneko Y. Novel hyaluronidase from streptomyces. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1970;198:607–609. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(70)90139-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Price K N, Al T, Baker D C, Chisena C, Cysyk R L. Isolation and characterization by electrospray-ionization mass spectrometry and high-performance anion-exchange chromatography of oligosaccharides derived from hyaluronic acid by hyaluronate lyase digestion: observation of some heretofore unobserved oligosaccharides that contain an odd number of units. Carbohydr Res. 1997;303:303–311. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(97)00171-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reeder J C, Cowman A F, Davern K M, Beeson J G, Thompson J K, Rogerson S J, Brown G V. The adhesion of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes to chondroitin sulfate A is mediated by P. falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:5198–5202. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.5198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rogerson S J, Chaiyaroj S C, Ng K, Reeder J C, Brown G V. Chondroitin sulfate A is a cell surface receptor for Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes. J Exp Med. 1995;182:15–20. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rowen J W, Brunish R, Bishop F W. Form and dimensions of isolated hyaluronic acid. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1956;19:480–489. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(56)90471-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith J D, Chitnis C E, Craig A G, Roberts D J, Hudson-Taylor D E, Peterson D S, Pinches R, Newbold C I, Miller L H. Switches in expression of Plasmodium falciparum var genes correlate with changes in antigenic and cytoadherent phenotypes of infected erythrocytes. Cell. 1995;82:101–110. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90056-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Southwell B R, Brown G V, Forsyth K P, Smith T, Philip G, Anders R. Field applications of agglutination and cytoadherence assays with Plasmodium falciparum from Papua New Guinea. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1989;83:464–469. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(89)90248-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Su X Z, Heatwole V M, Wertheimer S P, Guinet F, Herrfeldt J A, Peterson D S, Ravetch J A, Wellems T E. The large diverse gene family var encodes proteins involved in cytoadherence and antigenic variation of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes. Cell. 1995;82:89–100. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90055-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sunderland C A, Bulmer J N, Luscombe M, Redman C W G, Stirrat G M. Immunohistological and biochemical evidence for a role for hyaluronic acid in the growth and development of the placenta. J Reprod Immunol. 1985;8:197–212. doi: 10.1016/0165-0378(85)90041-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tammi R, MacCallum D, Hascall V C, Pienimaki J P, Hyttinen M, Tammi M. Hyaluronan bound to CD44 on keratinocytes is displaced by hyaluronan decasaccharides and not hexasaccharides. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:28878–28888. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.44.28878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Toffanin R, Kvam B J, Flaibani A, Atzori M, Biviano F, Paoletti S. NMR studies of oligosaccharides derived from hyaluronate: complete assignment of 1H and 13C NMR spectra of aqueous di- and tetra-saccharides, and comparison of chemical shifts for oligosaccharides of increasing degree of polymerisation. Carbohydr Res. 1993;245:113–128. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(93)80064-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walker A, Turnbull J E, Gallagher J T. Specific heparan sulphate saccharides mediate the activity of basic fibroblast growth factor. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:931–935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]