Abstract

Background and Aims

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) is not fully investigated, and how stromal cells contribute to ICC formation is poorly understood. We aimed to uncover ICC origin, cellular heterogeneity, and critical modulators during ICC initiation/progression, and to decipher how fibroblast and endothelial cells in the stromal compartment favor ICC progression.

Approach and Results

We performed single‐cell RNA sequencing (scRNA‐seq) using AKT/Notch intracellular domain–induced mouse ICC tissues at early, middle, and late stages. We analyzed the transcriptomic landscape, cellular classification and evolution, and intercellular communication during ICC initiation/progression. We confirmed the findings using quantitative real‐time PCR, western blotting, immunohistochemistry or immunofluorescence, and gene knockout/knockdown analysis. We identified stress‐responding and proliferating subpopulations in late‐stage mouse ICC tissues and validated them using human scRNA‐seq data sets. By integrating weighted correlation network analysis and protein–protein interaction through least absolute shrinkage and selection operator regression, we identified zinc finger, MIZ‐type containing 1 (Zmiz1) and Y box protein 1 (Ybx1) as core transcription factors required by stress‐responding and proliferating ICC cells, respectively. Knockout of either one led to the blockade of ICC initiation/progression. Using two other ICC mouse models (YAP/AKT, KRAS/p19) and human ICC scRNA‐seq data sets, we confirmed the orchestrating roles of Zmiz1 and Ybx1 in ICC occurrence and development. In addition, hes family bHLH transcription factor 1, cofilin 1, and inhibitor of DNA binding 1 were identified as driver genes for ICC. Moreover, periportal liver sinusoidal endothelial cells could differentiate into tip endothelial cells to promote ICC development, and this was Dll4‐Notch4‐Efnb2 signaling–dependent.

Conclusions

Stress‐responding and ICC proliferating subtypes were identified, and Zmiz1 and Ybx1 were revealed as core transcription factors in these subtypes. Fibroblast–endothelial cell interaction promotes ICC development.

Abbreviations

- AAV8

adeno‐associated virus 8

- CAF

cancer‐associated fibroblast

- CCA

cholangiocarcinoma

- CFL1

cofilin 1

- CNV

copy number variation

- DSS

drug sensitivity score

- EDN

endothelial differential network

- EpCAM

epithelial cell adhesion molecule

- EScore

cell enrichment score

- GSEA

gene‐set enrichment analysis

- Hes1

hes family bHLH transcription factor 1

- ICC

intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma

- ID1

inhibitor of DNA binding 1, HLH protein

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- LASSO

least absolute shrinkage and selection operator

- NICD

Notch intracellular domain

- PPI

protein–protein interaction

- SB

sleeping beauty transposase

- scRNA‐seq

single‐cell RNA sequencing

- TEC

tumor endothelial cell

- TF

transcription factor

- WGCNA

weighted correlation network analysis

INTRODUCTION

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) is the second most common liver malignancy, with increasing incidences and mortality rate.[ 1 ] Many driver genes and critical signaling molecules involved in ICC development have been identified using genomic and genetic studies. These genetic aberrations include activation of Akt,[ 2 ] Notch intracellular domain 1 (Notch1),[ 2 ] Notch2 [ 3 ] and Yap1, and inactivation of Fbxw7.[ 4 ] Activation of oncogenes and inactivation of tumor suppressor genes cooperates to drive cholangiocarcinogenesis. Like other cancers, ICCs are highly heterogeneous. Using exon sequencing and bulk RNA sequencing, Xiang et al. reported that ICC harbors significantly higher degrees of intratumoral heterogeneity than HCC.[ 5 ] Based on ICC patient transcriptomic profiles, “inflammation” (38%) and “proliferation: (62%) ICC subtypes were further identified.[ 1 ]

Similarly, heterogeneity of tumor microenvironment (TME) and roles of stromal cells in liver cancer have also been investigated. Job et al. classified the ICC immune microenvironment into four subtypes and 11 inflamed subtypes.[ 6 ] Zhang et al. reported that lysosomal‐associated membrane protein 3 positive dendritic cells arising from conventional dendritic cells can migrate from tumors to hepatic lymph nodes.[ 7 ] Programmed death ligand 1–positive tumor‐associated macrophages in TME facilitate cholangiocarcinoma progression.[ 8 ] Using single‐cell RNA sequencing (scRNA‐seq), Ma et al. analyzed the evolution of HCC and ICC and revealed that heterogeneity of the tumor is tightly linked to prognosis through the interaction of cancer‐associated fibroblasts (CAFs).[ 9 ] scRNA‐seq also revealed that most CAFs in ICC are vascular, and they induce significant epigenetic alterations in ICC cells through IL‐6 secretion and subsequent up‐regulation of enhancer of zeste 2 polycomb repressive complex 2 subunit (EZH2).[ 10 ]

However, these studies mostly used samples from patients with ICC at late tumor stages, making it difficult to analyze early events during ICC formation and development. In this study, we used scRNA‐seq together with an ICC mouse model (AKT/notch intracellular domain [NICD]) to reveal the ICC cellular heterogeneity, critical modulators during initiation, and interaction of stromal cells with ICC cells at different tumor stages. We sought to explore intratumoral cellular heterogeneity and identify tumor‐initiating progenitors, and the dynamic interaction between endothelial and fibroblast cells in ICC progression.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Bulk RNA and single‐cell data sets

All of the data sets applied in this study are found in Table S1.

Plasmids and ICC mouse model

Plasmids used in this study included pT3‐EF1α‐myr‐AKT1, pT3‐EF1α‐NICD, and pCMV‐SB (sleeping beauty transposase), and were gifts from Dr. Xin Chen of University of California, San Francisco, USA. C57/6J mice (6 weeks of age, Charles River Laboratories) were housed in a barrier facility and fed standard rodent chow. All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Xi’an Jiaotong University Health Science Center, and mice received humane care according to criteria outline in the "GUIDE FOR CARE AND USE OF LABORATORY ANIMALS (EIGHT EDITION)". Hydrodynamic tail vein injection was used to generate the ICC mouse model. Plasmids were amplified and purified using Plasmid MaxiPrep (endotoxin‐free) Kits. Plasmids (15 μg pT3‐EF1α‐myr‐AKT1, 15 μg pT3‐EF1α‐NICD, and 3 μg pCMV‐SB) were then diluted in 2 ml of saline and filtered through a sterile 0.22‐μm filter. Next, mixed plasmids solution (2 ml) was quickly injected into the tail vein of 6‐week‐old C57 mice for 5–7 s. Mice were monitored and tumor formation was examined via palpation daily. Mice were sacrificed 3, 5, 7, 10, 14, 17, or 31 days after plasmid injection. According to histological analysis and American Joint Committee on Cancer pathological staging guidelines, we chose ICC tissues on days 10, 17, and 31 as representatives of early‐stage, middle‐stage, and late‐stage ICC, respectively.

Liver‐specific Zmiz1 and Ybx1 deletion via adeno‐associated virus–single‐guide RNA

Four‐week‐old female C57/6J mice were purchased from Charles River Technology Corp. Adeno‐associated virus 8 (AAV8) was purchased from Shandong WZ Biotech. The virus was injected via the tail vein, 100 µl per mouse, at a concentration of 6 × 109 vector genomes per microliter. Two weeks after AAV8 virus injection, AKT/NICD and pCMV‐SB plasmids were injected to induce ICC. Single‐guide RNA (sgRNA) sequences were as follows: zinc finger, MIZ‐type containing 1 (Zmiz1) sgRNA 1, GGTAGGACCCAGCGAAACGGC; Zmiz1 sgRNA 2, TCAGT ACTTACCAGCAGACTT; Y box protein 1 (Ybx1) sgRNA 1, GTGTAGGCGATGGAGAGACTG; and Ybx1 sgRNA2, AGCAAATGTTACAGGCCCTGG. For both Zmiz1 and Ybx1, we used AAV8 delivering sgRNA1/2, to ensure the knockout efficiency.

AAV1 shRNA mediated liver‐specific Notch4 and Efnb2 knockdown

Four‐week‐old female C57/6J mice (Charles River Laboratories) were injected with Notch4 or ephrin B2 (Efnb2) AAV1‐shRNA in the experimental group and an empty AAV1 vector in the control group. Two weeks later, mice were hydrodynamically injected with AKT/NICD and SB plasmids to induce ICC for 5–7 s via the tail vein. The shRNA sequences were as follows: TCTGAGGTGGAGGTCAATG for Notch4 and CGGGTGTTACAGTAGCCTTAT for Efnb2.

Histology, immunohistochemistry, and immunofluorescence

Mice were euthanized and liver tissues were dissected and rinsed in saline. Aliquots of samples were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C overnight. The samples were paraffin‐embedded and cut into 5‐μm sections for hematoxylin and eosin staining, immunohistochemistry (IHC), or immunofluorescence. Antibodies used for IHC and immunofluorescence are listed in Table S2.

Library preparation and sequencing

A single‐cell suspension was prepared using the 10× Genomics Single Cell v3 Reagent Kit following the manufacturer’s instructions. For further details regarding the materials and methods, please refer to the Supporting Information.

RESULTS

Single‐cell transcriptomic profiling of AKT/NICD‐induced ICC

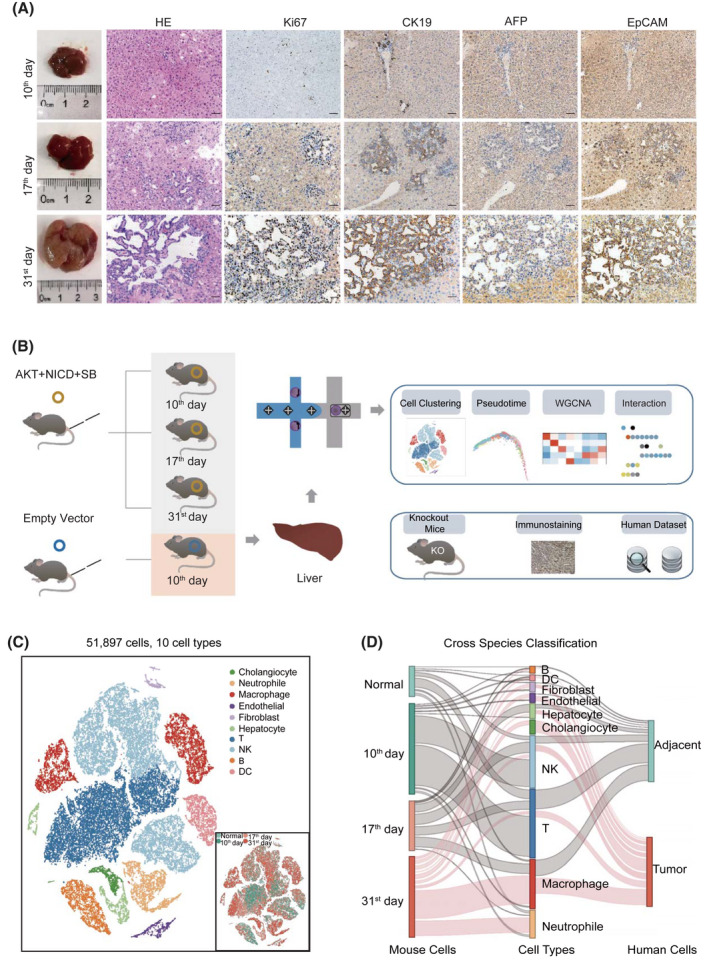

We performed histological examination of mouse ICC tissues collected at seven time points, and found that tumor budding appeared on day 10, and ductal‐like structures were formed on day 17. On day 31, ICC tumor nodules with bile‐like liquid were spread all over the liver surface, indicating an advanced stage of ICC (Figure S1A and Figure 1A). Consistent with our previous observation, ICC tissues were CK19‐positive, with typical glandular structure but no lipid droplets, although AKT is a potent de novo lipogenesis driver in HCC.[ 11 , 12 ] Therefore, we chose mouse ICC tissues collected on days 10, 17, and 31 as representatives of the early, middle, and late stages of ICC development, respectively. Then, we generated droplet‐based scRNA‐seq profiles (Figure 1B). After quality processing, we obtained a scRNA‐seq profile of 51,897 cells, including 2667 epithelial cells, 1422 stromal cells, 16,344 T cells, 6221 macrophages, and other cells (Figure 1C, Figure S1B, and Table S3). To verify whether these cell types identified from mice are consistent with those from human samples, we combined them with a published human ICC single‐cell data set (GSE138709). We found that cell‐type distribution in the normal mouse liver (control mice), or in early and middle stages of ICC (days 10 and 17), were similar to the corresponding cells in human ICC samples. After comparison, the late‐stage ICC cells collected from mice (day 31) were similar with human ICC tissues (Figure 1D and Figure S1C). These results indicated that data collected from mouse ICC were comparable with those from human samples.

FIGURE 1.

Transcriptomic profiling of AKT/Notch intracellular domain (NICD)–induced intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) in mice. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining and immunohistochemistry of mouse liver tissues collected on days 10, 17, and 31 after AKT/NICD plasmid injection. Scale bars represent 50 μm. (B) Overview of the study design. (C) The t‐distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t‐SNE) visualization of 51,897 cells from nine mouse ICC samples. Clusters and sample origins are distinguished by colors. (D) Comparison of cellular profiles between human and mouse ICC data (Sankey diagram). The height of each linkage line reflects the number of cells. The red line between cell types and two data sets represents the ICC cells from mice collected on day 31 and those from human samples. AFP, alpha‐fetoprotein; EpCAM, epithelial cell adhesion molecule; KO, knockout; SB, sleeping beauty transposase; WGCNA, weighted correlation network analysis

Stress‐responding and proliferating ICC subtype identification

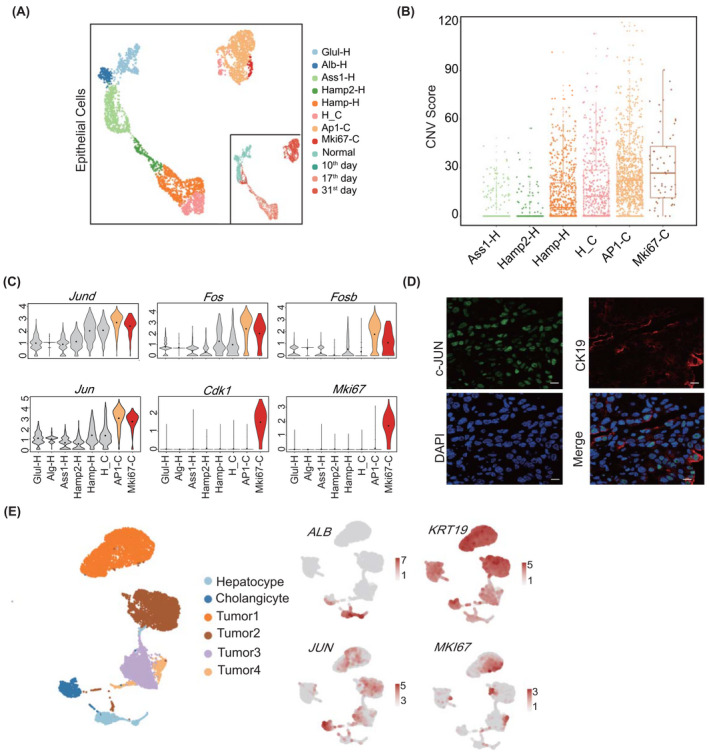

To reveal cellular heterogeneity in ICC tissues, we extracted epithelial cells from all stages and characterized their gene‐expression signatures. We obtained eight subclusters, including five epithelial cell adhesion molecule (Epcam)–Alb+ hepatocyte clusters (Glul‐H, Alb‐H, Ass1‐H, Hamp2‐H, and Hamp‐H), two Epcam+Alb‐Krt19+ biliary clusters (AP1 positive cholangiocyte AP1‐C and Mki67 positive cholangiocyte Mki67‐C), and an Epcam+Alb+Krt19‐ epithelial cluster H_C (Figure 2A and Figure S2A). Cluster distribution analysis (cell enrichment score [Escore]) showed that cells in Glul‐H and Alb‐H were mostly from normal mouse livers, cells in H‐C were from day 17 ICC livers, and cells in AP1‐C and Mki67‐C were from day 31 ICC livers (Figure 2A and Table S4). Using Glul‐H and Alb‐H as normal control cells, we calculated the copy number variation (CNV) in other subtype cells. Compared with Glul‐H and Alb‐H, AP1‐C and Mki67‐C cells showed significantly higher CNV scores, indicating that they were ICC cells (Figure 2B). Of note, AP1‐C cells highly expressed growth receptor genes Fgfr2 and Igf1r, as well as AP1 target genes Jun and Fos, but not Mki67 (Figure 2C and Figure S2A). In contrast, Mki67‐C cells exhibited high expression of DNA replication–related genes Mki67 and Cdk1 (Figure 2C). Because Jun and Fos are stress‐responding genes and Fgfr2 and Igf1r respond to extracellular stimuli,[ 13 , 14 ] we defined AP1‐C cells as the stress‐responding subtype. Likewise, Mki67 and Cdk1 are markers for cell proliferation[ 15 ]; hence, we referred to Mki67‐C as the proliferating subtype. Immunofluorescence showed that Jun (c‐Jun) and Krt19 were co‐expressed in day 31 mouse ICC tissues (Figure 2D). Moreover, we identified these two subtypes in human ICC samples, with stress‐responding subtype corresponding to tumor 2 (KRT19+, JUN+) and proliferating subtype corresponding to tumor 1 (KRT19+, MKI67+) using human ICC data set GSE138709 (Figure 2E).[ 10 ]

FIGURE 2.

Cellular heterogeneity of ICC tissues at different stages. (A) Eight subtypes in liver epithelial cells illustrated using uniform manifold approximation and projection (UAMP) plots and indicated with different colors. Sample origins are distinguished by colors as shown on the right bottom. (B) Copy number variation (CNV) box plots for distinct epithelial cell subtypes, indicating the malignant subtypes AP1‐C and Mki67‐C. For the boxplot, the centerline represents the median; box limits represent upper and lower quartiles; and whiskers represent the data range. (C) Violin plots showing the expression of marker genes in distinct malignant subtypes. (D) Immunofluorescence of c‐Jun (jun proto‐oncogene, Jun) in mice cells collected on day 31. The scale bars represent 10 µm. (E) Validating the two ICC subtypes in human ICC epithelial cells, the color from gray to red represents the expression level from low to high. ALB, albumin; Alb‐H, Alb positive hepatocyte; AP1‐C, AP1 positive cholangiocyte; Ass1‐H, Ass1 positive hepatocyte; Cdk1, cyclin‐dependent kinase 1; CK19, keratin 19 (Krt19); DAPI, 4′,6‐diamidino‐2‐phenylindole; Fos, FBJ osteosarcoma oncogene; Fosb, FBJ osteosarcoma oncogene B; Glul‐H, Glul positive hepatocyte; Hamp‐H, Hamp positive hepatocyte; H_C, cells with hepatocyte and cholangiocyte markers; Hamp2‐H, Hamp2 positive hepatocyte; Jund, jun D proto‐oncogene; Mki67, antigen identified by monoclonal antibody Ki67; Mki67‐C, Mki67 positive cholangiocyte

Distinct epigenetic modification and transcription factors involved in the two ICC subtypes

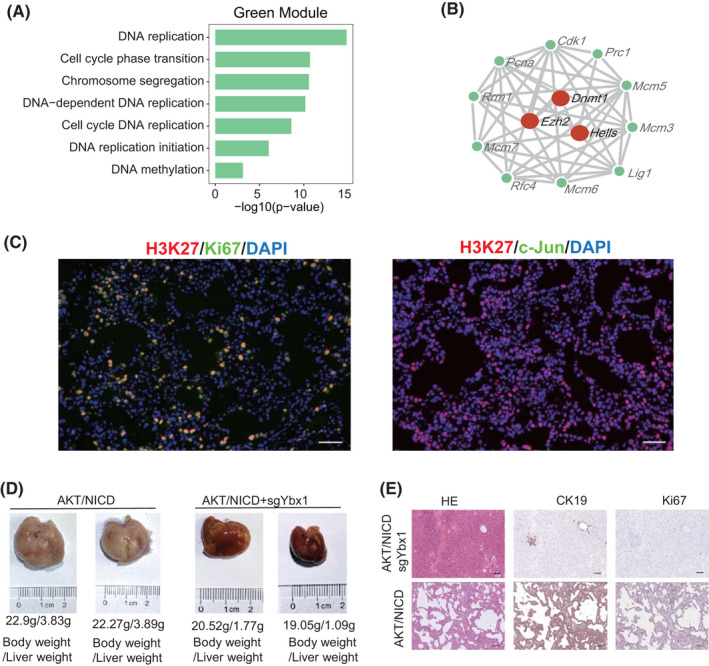

To screen hub genes in these two subtypes, we combined weighted correlation network analysis (WGCNA), least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO), and hypergeometric test (WLH) to analyze the transcription factors (TFs) in the two subtypes (Figure 3A and Supporting Methods). First, we dissected enriched signaling pathways by combining WGCNA with protein–protein interaction (PPI) analysis. Second, we integrated LASSO regression with hypergeometric test to identify critical TFs (Figure 3A). WGCNA analysis generated five gene modules: pink, brown, green, yellow, and turquoise. The turquoise module was positively correlated with the AP1‐C subtype (R = 0.89, p < 0.001; Figure 3B and Table S5). Among AP1‐C subtype‐specific gene modules, stress‐responding mitogen‐activated protein kinase and JNK pathways were enriched (Figure 3C). In addition, histone methylation–related genes Kdm6b, Jmjd1C, and Ash1l interacted with AP1 target genes (Jun, Fos, and Junb) in the WGCNA‐PPI network (Figure 3D), indicating that high level of H3K9 demethylation and H3K4 methylation may promote differentiation of ICC cells toward a stress‐responding subtype.[ 16 , 17 ] We further validated the modified histones via immunofluorescence, and the results showed that c‐Jun was co‐expressed with H3K4 in the stress‐responding subtype (Figure 3E). The result was also validated using the human data set (Figure S2B). Using WLH to analyze hub genes in the turquoise module, we found that Zmiz1 was the core modulator in the AP1‐C subtype (Table S6, Figure S3A, and Figure S4A). Using AAV8‐delivered sgRNA‐mediated CRISPR via tail vein injection, we deleted Zmiz1 in mouse hepatocytes (Figure S3A), and found that ICC formation was significantly blocked and only very minor ICC lesions were formed (Figure 3F,G). These results indicate that Zmiz1 was required for ICC formation.

FIGURE 3.

Transcription factors (TFs) involved in the stress‐responding subtype. (A) Workflow of the TF screening method. (B) WGCNA results showing the gene modules in distinct epithelial cell subtypes. Columns represent cell types. The color from blue to red indicates a low to a high correlation between gene module and cell subtypes (Pearson correlation test). (C) Enrichment analysis using the hub genes in stress‐responding subtype using clusterProfiler. (D) Hub gene network of the stress‐responding subtype, in which red nodes indicate the methylation and AP1‐related genes. (E) Immunofluorescence of H3K4, Ki67, and c‐Jun in AKT/NICD mouse ICC tissues. Scale bar = 50 μm. (F) Gross images of AKT/NICD mice with or without sgZmiz1 injection. (G) Immunohistochemistry of AKT/NICD mouse livers injected with sgZmiz1. Scale bar = 50 μm; magnification = ×200. Actb, actin, beta; Ash1l, ASH1 like histone lysine methyltransferase; Arid4b, AT‐rich interaction domain 4B; Atf3, activating transcription factor 3; Atrx, ATRX chromatin remodeler; Brd2, bromodomain containing 2; Cbx6, chromobox 6; c‐Jun, Jun; Ets2, E26 avian leukemia oncogene 2, 3' domain; Hsp90b1, heat shock protein 90 beta family member 1; H3f3b, H3.3 histone B; Jmjd1c, jumonji domain containing 1C; Ki67, Mki67; Kdm6b, lysine demethylase 6B; Kmt2e, lysine (K)‐specific methyltransferase 2E; MAPK, mitogen‐activated protein kinase; Nfe2l2, nuclear factor, erythroid derived 2, like 2; Ncor1, nuclear receptor co‐repressor 1; Nsd1, nuclear receptor‐binding SET‐domain protein 1; Pbrm1, polybromo 1; PPI, protein–protein interaction; Sptan1, spectrin alpha, non‐erythrocytic 1; Smarca2/4/5, Rela, v‐rel reticuloendotheliosis viral oncogene homolog A (avian); SWI/SNF related, matrix associated, actin dependent regulator of chromatin, subfamily a, member 2/4/5; Sox9, SRY‐box transcription factor 9; Stat3, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; Tnrc6a, trinucleotide repeat containing 6a

Likewise, the green module was correlated with the proliferating subtype Mki67‐C (R = 0.96, p < 0.001; Figure 3B), and DNA replication pathways were enriched in this module (Figure 4A). Dnmt1, Ezh2, and Hells expression was positively correlated with Cdk1 expression, indicating that H3K27 methylation was involved in differentiation and growth of proliferating ICC cells (Figure 4B). We also validated the co‐expression of H3K27 and Ki67 (Mki67) in the proliferating subtype via immunofluorescence, as well as in the human data set (Figure 4C and Figure S2B). Meanwhile, Ybx1 was identified as a core modulator in this subtype (Table S7). AAV8‐delivered CRISPR/sgYbx1 confirmed the essential role of Ybx1 in ICC initiation, and only tiny ICC lesions formed after Ybx1 deletion (Figure 4D,E and Figure S3B). Indeed, human ICC single‐cell sequencing and bulk RNA sequencing, as well as additional mouse single‐cell data sets (YAP/AKT, KRAS/p19), all illustrated that Zmiz1 was highly expressed in AP1‐positive cells and Ybx1 was highly expressed in Mki67‐positive cells, further confirming their specific role in stress‐responding and proliferating ICC cells, respectively (Figure S4B–E).

FIGURE 4.

Distinct function of TFs involved in the proliferating subtype. (A) Enrichment analysis of the proliferating subtype hub genes using clusterProfiler. (B) Hub gene network of the proliferating subtype, in which red nodes indicate the methylated genes. (C) Immunofluorescence of H3K27 methylation, c‐Jun (Jun), and Ki67 (Mki67) in AKT/NICD mouse ICC tissues. Scale bar = 50μm. (D) Gross images of AKT/NICD mice with or without sgYbx1 injection. (E) Immunohistochemistry of AKT/NICD mouse livers with sgYbx1 injection. Scale bar = 50 μm; Magnification = ×200. Cdk1, yclin‐dependent kinase 1; CK19, Krt19; Dnmt1, DNA methyltransferase (cytosine‐5) 1; Ezh2, enhancer of zeste 2 polycomb repressive complex 2 subunit; Hells, helicase, lymphoid specific; Lig1, ligase I, DNA, ATP‐dependent; Mcm3/5/6/7, minichromosome maintenance complex component 3/5/6/7; Pcna, proliferating cell nuclear antigen; Prc1, protein regulator of cytokinesis 1; Rfc4, replication factor C (activator 1) 4; Rrm1, ribonucleotide reductase M1

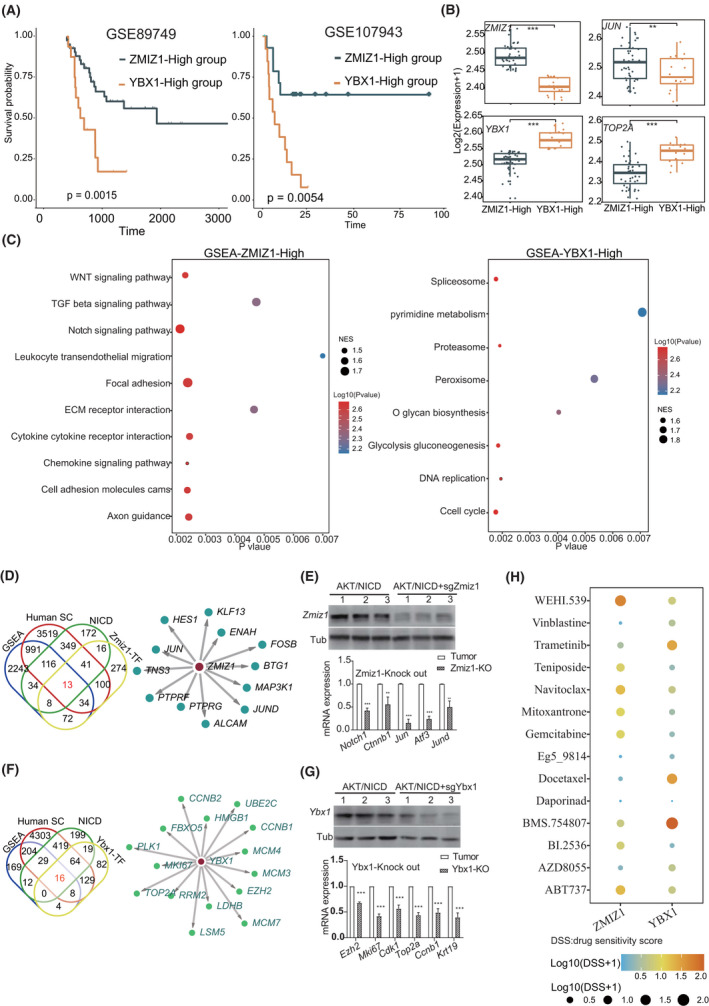

ZMIZ1 and YBX1 act as oncogenes via different downstream genes

Next, we investigated the oncogenic role of ZMIZ1 and YBX1 using data from patients with ICC. We found that ZMIZ1 and YBX1 expression in patients with ICC was significantly related to survival using data sets GSE89749 and GSE107943. Patients with ICC with high ZMIZ1 expression showed higher JUN and demonstrated better prognosis (Figure 5A,B) than those with low ZMIZ1 expression. Of note, NOTCH1, JAG1, and hes family bHLH transcription factor 1 (HES1) were all highly expressed in the ZMIZ1‐high group (Figure S5). In comparison, patients with ICC with high YBX1 expression showed increased MKI67 and EZH2 expression but poor prognosis (Figure 5A,B and Figure S5). The gene‐set enrichment analysis (GSEA) results indicated that ZMIZ1‐high cells in humans corresponded to the stress‐responding subtype in mice, and YBX1‐high cells to the proliferating subtype (Figure 5C). Next, we screened genes regulated by these two TFs in both mouse and human ICC tissues. We first screened common genes from the GSEA pathway and differentially expressed genes from human ICC single‐cell data. Then, we focused on differentially expressed genes and ZMIZ1 target genes from stress‐responding subtype cells of AKT/NICD mouse ICC tissues, and subsequently obtained a 13‐gene ZMIZ1‐regulon (Figure 5D and Table S8). We found that Zmiz1 enhanced expression of AP1 target genes (Jun and Jund), and those genes were significantly down‐regulated in Zmiz1‐deficient mouse liver tissues (Figure 5E). Likewise, we obtained a 16‐gene YBX1 regulon (Figure 5F and Table S8). Ybx1 enhanced the expression of Mki67, Top2a, and Ezh2. The expression of these genes was reduced in the Ybx1‐deficient mouse liver tissues (Figure 5G). Therefore, ZMIZ1 promoted the stress‐responding ICC differentiation by up‐regulating the AP1 target genes, whereas YBX1 promoted ICC proliferation by activating EZH2 and MKI67 expression.

FIGURE 5.

Distinct function of ZMIZ1 and YBX1 in ICC. (A) Prognosis of ZMIZ1‐high and YBX1‐high patients in two bulk RNA data sets (GSE89749 and GSE107943). Statistical significance was calculated using the log‐rank test. (B) Expression levels of AP1 and proliferating genes in the ZMIZ1‐high and YBX1‐high group (***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; Wilcoxon rank‐sum test). (C) Dot plot showing the gene‐set enrichment analysis (GSEA) result in the ZMIZ1‐high and YBX1‐high groups. Dot size indicates the normalized enrichment score (NES) values, and colors indicate p values. (D) Venn plot showing targets of ZMIZ1 (left) and the TF network showing the ZMIZ1 regulon. (E) Western blots showing Zmiz1 expression in AKT/NICD and AKT/NICD+sgZmiz1 mice (upper). Expression of Zmiz1 target genes in tumor tissues and Zmiz1‐knockout mice (***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01; Student’s t test). (F) Venn plot showing target genes of YBX1 (left) and the TF network showing the YBX1 regulon. (G) Western blots showing Ybx1 expression in the AKT/NICD and AKT/NICD+sgYbx1 mice (upper). Expression of Ybx1 target genes in tumor tissues and Zmiz1‐knockout mice (***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01; Student’s t test). (H) Dot plot showing the mean drug sensitivity scores (DSSs) using the ZMIZ1 and YBX1 regulon through oncoPredict. Colors from blue to red indicate the Log10 (DSSs + 1) low to high (***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01; Wilcoxon rank‐sum test). Human SC, human single‐cell data

We then assessed the drug sensitivity scores (DSSs) for the two ICC subtypes using the above 13‐gene and 16‐gene ZMIZ1 and YBX1 regulon, respectively, using oncoPredict (Supporting Methods).[ 18 ] The results showed that Vinblastine, AZD8055, Docetaxel, and BMS.754807 showed high cytotoxicity (lower DSSs) in the stress‐responding subtype (fold change < 0.25). BI.2536, Gemcitabine, Teniposide, and Mitoxantrone showed high cytotoxicity in the proliferating subtype (fold change < 0.25; Table S9). Daporinad showed a low DSS (fold change < 0.1) in both subtypes. Therefore, these drugs have the potential to be applied in personalized ICC treatment (Figure 5H).

HES1, CFL1, and ID1 promote ICC initiation

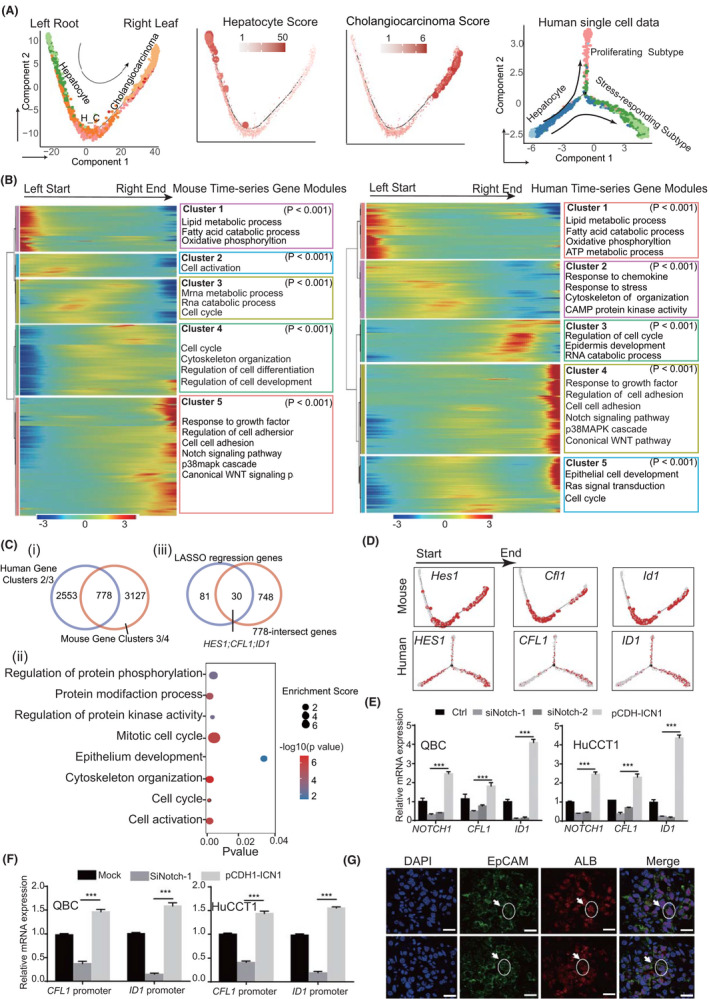

Next, we wanted to seek driver genes in early‐stage ICC. We performed pseudo‐time analysis using both mouse and human ICC scRNA‐seq data (Figure 6A). The hepatocyte and cholangiocarcinoma scores along the pseudo‐time axis indicated that cells gradually evolved from normal hepatocytes to cholangiocarcinoma along the pseudo‐time axis in both human and mouse data sets (Figure 6A and Supporting Methods). Cells expressing both liver and bile duct marker genes (H_C, Epcam+Alb+; Figure 6A) were located in the intermediate position along the pseudo‐time axis in mice. The gene modules also presented a chronologic profile along the time axis in both human and mouse data sets. Interestingly, gene modules 3/4 in mouse data and modules 2/3 in human data were active at the intermediated ICC stage, indicating that these gene modules may contain the early ICC driver genes (Figure 6B). We then intersected the genes in the human and mouse–intermediated modules and obtained 778 genes enriched in protein phosphorylation and cell cycle transition pathways (Figure 6C). We further screened core driver genes involved in ICC initiation using LASSO regression with ICC scores as a dependent variable and the differential genes from the H_C cluster (Epcam+Alb+) as the independent variable. Next, we obtained 30 genes by overlapping the LASSO genes with the 778 genes, in which hes family bHLH transcription factor 1(HES1), cofilin 1(CFL1), and inhibitor of DNA binding 1, HLH protein (ID1) were associated with cell‐cycle progression and epithelium development, and their expression was increased along with the pseudo‐time axis in both mouse and human data (Figure 6C,D). Because HES1 is a known target of NOTCH, we examined whether CFL1 and ID1 were NOTCH targets. Quantitative real‐time PCR and luciferase reporter assay indicated that CFL1 and ID1 transcription was affected by NOTCH1 (Figure 6E,F). Identification of HES1 as the core factor and CFL1 and ID1 as NOTCH1 targets confirmed the critical role of Notch signaling in ICC formation, consistent with the overexpression of Notch signaling‐related proteins in ICC. Interestingly, these genes were initially expressed in H_C (Alb+EpCam+) cells corresponding to middle‐stage ICC (the 17th day), further indicating that these cells could be the early origin cells during ICC formation (Figure 6G).

FIGURE 6.

Genes related to ICC initiation in mouse and human. (A) Pseudo‐time analysis of epithelial cells using mouse and human ICC single‐cell data. Hepatocyte and cholangiocarcinoma scores were determined according to the average expression of their marker genes. Colors from gray to red and dot size indicate the value from low to high. (B) Differentially expressed genes (rows) along the pseudo‐time (columns) were clustered hierarchically into five groups in mice and human data. Pathway enrichment scores were calculated using clusterProfiler. (C) (i) Veen plots showing 778 genes from intermediated gene modules along the pseudo‐time axis both in mouse and human data. (ii) Dot plot showing the enriched pathways of 778 genes; dot size indicates enrichment score (GeneRatio/BgRatio in clusterProfiler), and color indicates the p values. Pathway enrichment scores were calculated using clusterProfiler. (iii) 30 genes obtained by overlapping the LASSO genes with the 778 genes. (D) Gene‐expression level of the three genes along the pseudo‐time axis. Colors from gray to red represent their expression level low to high. (E) mRNA expression of CFL1 and ID1 in ICC cell lines QBC and HuCCT1 cells after NOTCH1 silencing or overexpression (***p < 0.001; Student’s t test). (F) Relative luciferase activity detected in QBC and HuCCT1 cells 48 h after transfection. ICC cells were transfected with luciferase reporter plasmid, then with NOTCH1 shRNA or infected with the pCDH‐ICN1 lentivirus (***p < 0.001; Student’s t test). (G) Immunofluorescence of double‐positive (Alb+Epcam+) cells in liver tissues of mice collected on day 17. The dotted circle outlines the cells. The scale bars represent 20 μm. CAMP, cyclic adenosine monophosphate; LASSO, least absolute shrinkage and selection operator

Endothelial cells and fibroblasts interact with each other to promote ICC progression

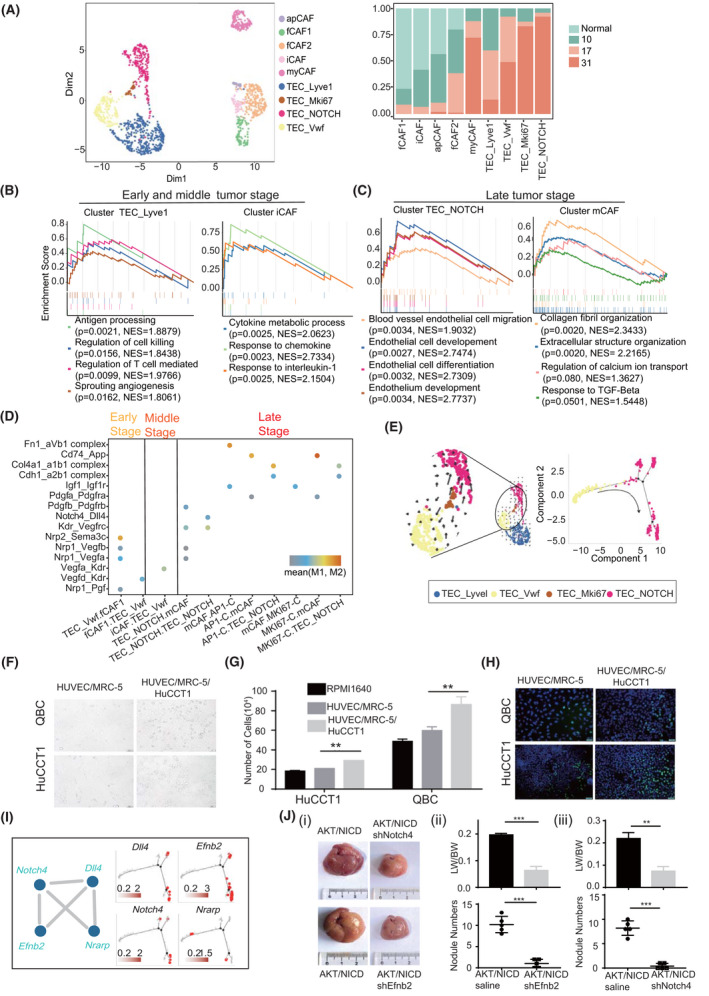

Fibroblasts can interact with endothelial cells and thereby promote the proliferation and invasion of cancer cells.[ 19 ] To explore their roles during ICC initiation and progression, we reclustered tumor endothelial cells (TECs) and grouped them into four subtypes: TEC‐Lyve1, TEC‐Vwf, TEC‐Mki67, and TEC‐NOTCH. Likewise, fibroblasts were grouped into five subtypes: fCAF1, fCAF2, iCAF, apCAF, and myCAF (Table S10, Figure 7A, and Figure S6A). Interestingly, endothelial cells Lyve1‐TEC and fibroblasts fCAF, iCAF, and apCAF were enriched in the early‐stage ICC (EScore > 1; Table S11 and Figure 7A); TEC‐Vwf cells were enriched in the middle‐stage and late‐stage ICC (EScore > 1; Table S11 and Figure 7A); and TEC_Mki67, TEC‐NOTCH, and fibroblast subtype myCAF were enriched in the late‐stage ICC (EScore > 1; Table S11 and Figure 7A). In addition, endocytosis and pro‐inflammatory chemokines were enriched in the early endothelial subtypes, and pro‐inflammatory ILs and antigen‐presenting molecules were enriched in TEC_Lyve1 and iCAF (Figure 7B). These results indicate that both endothelial cells and fibroblasts in early and middle stages have pro‐inflammatory roles in ICC development. In comparison, angiogenesis signaling was enriched in TEC‐NOTCH and fibrosis pathways were enriched in myCAF, suggesting that endothelial cells and fibroblasts promoted tumor growth in late stages of ICC (Figure 7C).

FIGURE 7.

Endothelial cells and fibroblasts promote ICC development. (A) Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) of endothelial cells and fibroblasts. Sample origins are distinguished via colors as shown on the right. GSEA plot showing gene functions in endothelial cell and fibroblast subtypes at early and middle stages (B) and late stage (C) of ICC. NES and p values were calculated using GSEA. (D) Dot plot showing the L–R pairs between endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and ICC cells at different tumor stages. Rows represent the L–R pairs, and columns represent cell subset–cell subset pairs. The color gradient from black/blue to red indicates mean values of the L–R pairs from low to high, and the circle size indicates the significance of the pairs. p values were calculated via a permutation test using CellPhoneDB. (E) RNA velocities visualized on the UMAP projection showing the differentiation trajectory from TEC_Vwf to TEC_NOTCH. (F) QBC and HuCCT1 cells were co‐cultured with HUVECs and human embryonic lung fibroblast MRC‐5 cells at a ratio of 1:1:1 for 24 h to establish a conditioned medium. Scale bar = 50 μm; magnification = ×200. (G) QBC and HuCCT1 cells were cultured in the conditioned medium and Roswell Park Memorial Institute 1640 medium (1:1) for 24 h, and cell numbers were determined (**p < 0.01; Student’s t test). (H) 5‐Ethynyl‐2’‐deoxyuridine (EDU) staining to detect the proliferation of QBC and HuCCT1 cells cultured in the conditioned medium for 24 h. (I) Genes in the WGCNA‐PPI subnetwork in TEC‐NOTCH and their pseudo‐time profile. (J) (i) Gross images of AKT/NICD mice injected with shNotch4 or shEfnb2 AAV1. Transparent and convex nodules with yellow liquid are ICC lesions. (ii) Quantification of ICC nodule numbers and the ratio of liver weight (LW) to body weight (BW) in two groups of mice with or without shEfnb2 (ii)/shNotch4 (iii) (n = 5, ***p < 0.001; Student’s t test)

Of note, both TEC‐Vwf and TEC‐NOTCH were classified as periportal liver sinusoidal endothelial cells due to high Mgp, Pecam1, and Vwf expression, but low Lyve1 expression in these cells (Figure S6A).[ 20 ] TEC‐Vwf cells were primarily observed in the middle and late tumor stages (EScore > 1; Table S11), showing high expression of Kdr (Vegfr2) but low expression of Dll4 (Figure S6A). TEC‐NOTCH cells dominated the late‐stage ICC and demonstrated active Notch signaling with high expression of Notch4 and Dll4 (Figure S6A), indicating that TEC‐NOTCH cells were tip endothelial cells.[ 21 ] In middle‐stage ICC, fCAF2 and iCAF with high expression of Vegfd and Vegfa interacted with TEC‐Vwf overexpressing Kdr (Figure 7D and Figure S6A). Because the Vegf/Vegfr (Kdr) cascade promotes the expression of Dll4 and induces the formation of tip endothelial cells,[ 21 ] TEC‐NOTCH cells could be differentiated from TEC‐Vwf cells. Cell velocity and pseudo‐time analysis further confirmed the origin of TEC‐NOTCH cells (Figure 7E). In the late tumor stage, TEC‐NOTCH interacted with myCAF cells through Pdgfb/Pdgfrb (Figure 7D). In addition, TGF‐β and calcium signaling were activated in myCAF (Figure 7C). Because PDGF cooperates with TGF‐β and activates calcium signaling to promote fibrosis,[ 22 ] we proposed that TEC‐NOTCH promotes the differentiation of fibroblasts into myCAF. In addition, myCAF promoted ICC progression through Igf1/Igf1r signaling (Figure 7D). Moreover, enriched adhesion molecules integrin a1b1 and a2b1 complex, as well as the collagen synthesis protein Col4a1, indicated that myCAF and TEC_NOTCH cells interacted with both AP1‐C and MKI67‐C ICC cells (Figure 7D). Critically, endothelial‐fibroblast‐ICC (HUVEC/MRC‐5/HuCCT1) co‐culture–derived conditioned medium significantly promoted ICC cell growth (Figure 7F–H). Collectively, these data suggested a frequent communication between stromal and ICC cells in the late tumor stage and the interaction of endothelial cells with fibroblasts to promote ICC cell growth.

To investigate the role of the tip endothelial cells in ICC progression, we explored hub genes involved in the formation of tip endothelial cells using WGCNA‐PPI analysis. We found that the blue module was correlated with TEC‐NOTCH cells (R = 0.85, p < 0.001; Figure S6B). WGCNA‐PPI analysis showed that two endothelial cell networks were enriched in TEC‐NOTCH cells as follows: the endothelial differential network (EDN) containing Efnb2, Dll4, and Notch4; the endothelial adhesion network containing Itga5, Itga6, and Lama5 (Figure 7I and Figure S6C,D).[ 23 ] EDN may promote tip endothelial cell formation, as Lama5 induces the NOTCH pathway by interacting with integrin.[ 24 ] In addition, expression of Efnb2, Dll4, and Notch4 increased during this process, suggesting that the EDN network might promote the differentiation of TEC‐Vwf into TEC‐NOTCH (Figure 7I). Critically, liver‐specific knockdown of Efnb2 or Notch4 using AAV1‐shRNA led to retarded ICC development, indicating that the EDN network favored ICC development (Figure 7J and Figure S6E).

Moreover, Dll4‐Notch4‐Efnb2 were highly expressed in YAP/AKT and KRAS/p19 mouse ICC cells and human Dll4+Mgp+ ICC cells, further confirming their important roles in promoting endothelial cell differentiation (Figure S6F–H). In addition, EFNB2 was highly expressed in human ICC tissues, and its high expression was associated with a poor prognosis in multiple data sets (Figure S7). Taken together, our data indicate that fibroblasts interact with endothelial cells and promote their differentiation to promote ICC development.

DISCUSSION

In this study, using the ICC mouse model and scRNA‐seq, we identified two distinct ICC cell populations and uncovered central pathways and core TFs governing the development of these two types of ICC cells. In addition, we revealed the pivotal roles of fibroblasts and endothelial cells in ICC progression and how endothelial cells or fibroblasts favor tumor progression. These findings deepen our understanding of ICC formation and evolution, and help improve ICC targeted therapy.

First, we identified two ICC subtypes and uncovered distinct core signaling in those two subtypes. These two subtypes, proliferating and stress‐responding subtypes, showed different methylation patterns and activation of different core TFs. Proliferating ICC cells showed evident H3K27 methylation by Ezh2 and high expression of Ybx1. Considering that Ybx1 regulates Ezh2, our results suggest that the Ybx1‐Ezh2‐H3K27 methylation axis plays a central role in proliferating ICC cells and may serve as a therapeutic target. Furthermore, YB‐1 phosphorylation regulates cell proliferation and oncogenic transformation.[ 25 ] Compared with the proliferating subtypes, stress‐responding ICC cells showed H3K4 methylation and high expression of Zmiz1. Zmiz1 has been identified as a prognostic marker in glioblastoma and other cancer types.[ 26 ] Zmiz1 and Notch1 can cooperatively recruit each other to activate histone markers.[ 27 ] Likewise, Zmiz1 co‐operated with Notch1 to promote the formation of stress‐responding ICC cells in our ICC model. Identification of differential core signaling molecules in these two ICC subpopulations indicates that personalized and combined targeted therapy may be required for different patients.

Second, our study identified critical genes modulating ICC initiation and progression. Using various genetic mouse models alone or with a lineage tracing system, several groups have proven that ICC originates from hepatoblasts or hepatocytes.[ 28 , 29 ] Tschaharganeh et al. reported that loss of p53 facilitates dedifferentiation of mature hepatocytes into nestin‐positive progenitor‐like cells, which then differentiate into HCC or ICC cells.[ 28 ] Tanimizu et al. reported that Notch1 can drive differentiation of hepatoblasts into cholangiocytes by enhancing the expression of liver‐enriched TFs.[ 30 ] In this study, we screened critical genes mediating NOTCH1‐driven ICC initiation and found three genes (Hes1, Cfl1, and Id1) promoting ICC initiation. ID1 is highly expressed in stomach, colon, prostate, ovary, bladder, pancreas, and brain tumors.[ 31 ] Seno et al. reported that Hes1 plays a critical role in the induction of ICC.[ 18 ] CFL1 maintains PL‐D1 expression by repressing ubiquitin‐mediated protein degradation, thereby activating AKT signaling in HCC cells.[ 32 ] The expression levels of these three genes were positively correlated with ICC progression as observed from mouse and human single‐cell data. Meanwhile, these three genes were initially expressed in hepatocyte‐like cells among H_C (Alb+EpCam+) cells primarily isolated from the middle‐stage ICC tissues in mice (17 days), indicating that these cells may be the origin of ICC. However, how these three genes promote ICC progression at the cellular and molecular level warrants further study.

Third, our study revealed that endothelial cells and fibroblasts interact with each other and adapt themselves to promote ICC development. In response to ICC initiation, fibroblasts promote the development of tip endothelial cells through VEGF expression. At the early stages of ICC, endothelial cells and fibroblasts may block ICC progression. Later, endothelial cells are evolved to stem endothelial cells and lose their inflammatory function and alternatively promote the transformation of fibroblasts to myofibroblasts through Pdgfb expression. Myofibroblasts, in turn, highly express growth factors and therefore promote the growth of ICC cells. Abrogation of Dll4‐Notch4‐Efnb2 would block the maturation of endothelial cells and subsequently inhibit fibrosis formation mediated by CAFs. Consistent with our observation, the Dll4‐Notch‐Efnb2 axis mediates mouse embryonic angiogenesis.[ 33 ] Therefore, our study corroborated the potential of the Dll4‐Notch4‐Efnb2 axis as a therapeutic target in ICC treatment.

Our study has several limitations. First, we used a mouse model to identify the critical modulators and required genes for ICC initiation and development rather than human ICC tissues. ICC initiation in mice could be different from that in humans. Thus, the genes or signaling we identified in this study need to be further characterized in human ICC cell lines and tissues, although they have been validated in the human scRNA‐seq data set. Second, the number of ICC cells collected from mouse ICC tissues was lower than we expected, which may have caused some discrepancy in the identification of critical genes. Three reasons may have caused the lower number of ICC cells than immune cells: necrosis of ICC cells in the core ICC tissues; vulnerability of tumor cells compared with immune cells; and the capture immune cells (smaller) by the gel beads in emulsion (10× genomic) rather than tumor cells (larger). However, the imbalance of tumor cell to immune cell does not affect our major conclusions, because our analyses was based on expression profiles of distinct cell types and not dependent on the proportion of each cell type. Finally, we used an ICC mouse model derived from hepatocytes but not cholangiocytes. Therefore, whether these findings obtained here apply to ICC initiated from cholangiocytes needs to be investigated.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Nothing to report.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Kai Ye, Lei Li, Tingjie Wang, Chuanrui Xu, Lei Li and Bingyin Shi were substantial contributions to conception and design. Tingjie Wang, Chuanrui Xu, Zhijing Zhang and Ningxin Dang acquired, analyzed and interpreted the data. Hua Wu, Yu Zhang, Nan Deng, Guangbo Tang, Xiujuan Li and Zihang Li performed animal and cell culture validation. Tingjie Wang, Chuanrui Xu drafted the article. Lei Li and Kai Ye revised the article critically for important intellectual content. Lei Li and Kai Ye final approved the version to be published.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

Wang T, Xu C, Zhang Z, Wu H, Li X, Zhang Y, et al. Cellular heterogeneity and transcriptomic profiles during intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma initiation and progression. Hepatology. 2022;76:1302–1317. 10.1002/hep.32483

Tingjie Wang and Chuanrui Xu contributed equally to this work.

Funding information

Supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32125009, 32070663, 61702406, 82073091, and 81872253), and the Key Construction Program of the National “985” Project, using the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (xzy012020012)

SEE EDITORIAL ON PAGE 1233

Contributor Information

Lei Li, Email: leileilesure@163.com.

Kai Ye, Email: kaiye@xjtu.edu.cn.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The datasets analyzed in this study are available from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository under the following accession numbers: GSE138709, GSE154170 (GSM5023597 and GSM4665447), GSE115469, TCGA‐CHOL, GSE107943, GSE76297, GSE89749, GSE109774 and Sequence Read Archive (SRA) with the accession number PRJNA743579 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA743579). The other data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. More information about the data were available in the supplementary material.

REFERENCES

- 1. Banales JM, Marin JJG, Lamarca A, Rodrigues PM, Khan SA, Roberts LR, et al. Cholangiocarcinoma 2020: the next horizon in mechanisms and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17:557–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fan B, Malato Y, Calvisi DF, Naqvi S, Razumilava N, Ribback S, et al. Cholangiocarcinomas can originate from hepatocytes in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:2911–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wang J, Dong M, Xu Z, Song X, Zhang S, Qiao YU, et al. Notch2 controls hepatocyte‐derived cholangiocarcinoma formation in mice. Oncogene. 2018;37:3229–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Song X, Xu H, Wang P, Wang J, Affo S, Wang H, et al. Focal adhesion kinase (FAK) promotes cholangiocarcinoma development and progression via YAP activation. J Hepatol. 2021;75:888–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Xiang X, Liu Z, Zhang C, Li Z, Gao J, Zhang C, et al. IDH mutation subgroup status associates with intratumor heterogeneity and the tumor microenvironment in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Adv Sci. 2021;8:e2101230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Job S, Rapoud D, Dos Santos A, Gonzalez P, Desterke C, Pascal G, et al. Identification of four immune subtypes characterized by distinct composition and functions of tumor microenvironment in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology. 2020;72:965–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhang Q, He Y, Luo N, Patel SJ, Han Y, Gao R, et al. Landscape and dynamics of single immune cells in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell. 2019;179:829–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Loeuillard E, Yang J, Buckarma EeeLN, Wang J, Liu Y, Conboy C, et al. Targeting tumor‐associated macrophages and granulocytic myeloid‐derived suppressor cells augments PD‐1 blockade in cholangiocarcinoma. J Clin Invest. 2020;130:5380–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ma L, Wang L, Khatib SA, Chang C‐W, Heinrich S, Dominguez DA, et al. Single‐cell atlas of tumor cell evolution in response to therapy in hepatocellular carcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatol. 2021;75:1397–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhang M, Yang H, Wan L, Wang Z, Wang H, Ge C, et al. Single‐cell transcriptomic architecture and intercellular crosstalk of human intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatol. 2020;73:1118–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Li L, Che L, Tharp KM, Park HM, Pilo MG, Cao D, et al. Differential requirement for de novo lipogenesis in cholangiocarcinoma and hepatocellular carcinoma of mice and humans. Hepatology. 2016;63:1900–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Li L, Pilo GM, Li X, Cigliano A, Latte G, Che LI, et al. Inactivation of fatty acid synthase impairs hepatocarcinogenesis driven by AKT in mice and humans. J Hepatol. 2016;64:333–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Moncada R, Barkley D, Wagner F, Chiodin M, Devlin JC, Baron M, et al. Integrating microarray‐based spatial transcriptomics and single‐cell RNA‐seq reveals tissue architecture in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas. Nat Biotechnol. 2020;38:333–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen HX, Sharon E. IGF‐1R as an anti‐cancer target—trials and tribulations. Chin J Cancer. 2013;32:242–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhang H, Zhang X, Li X, Meng W‐B, Bai Z‐T, Rui S‐Z, et al. Effect of CCNB1 silencing on cell cycle, senescence, and apoptosis through the p53 signaling pathway in pancreatic cancer. J Cell Physiol. 2018;234:619–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Viscarra JA, Wang Y, Nguyen HP, Choi YG, Sul HS. Histone demethylase JMJD1C is phosphorylated by mTOR to activate de novo lipogenesis. Nat Commun. 2020;11:796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gregory GD, Vakoc CR, Rozovskaia T, Zheng X, Patel S, Nakamura T, et al. Mammalian ASH1L is a histone methyltransferase that occupies the transcribed region of active genes. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:8466–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Matsumori T, Kodama Y, Takai A, Shiokawa M, Nishikawa Y, Matsumoto T, et al. Hes1 is essential in proliferating ductal Cell‐mediated development of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 2020;80:5305–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Leung CS, Yeung T‐L, Yip K‐P, Wong K‐K, Ho SY, Mangala LS, et al. Cancer‐associated fibroblasts regulate endothelial adhesion protein LPP to promote ovarian cancer chemoresistance. J Clin Invest. 2018;128:589–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. MacParland SA, Liu JC, Ma X‐Z, Innes BT, Bartczak AM, Gage BK, et al. Single cell RNA sequencing of human liver reveals distinct intrahepatic macrophage populations. Nat Commun. 2018;9:4383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chen W, Xia P, Wang H, Tu J, Liang X, Zhang X, et al. The endothelial tip‐stalk cell selection and shuffling during angiogenesis. J Cell Commun Signal. 2019;13:291–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ying H‐Z, Chen Q, Zhang W‐Y, Zhang H‐H, Ma Y, Zhang S‐Z, et al. PDGF signaling pathway in hepatic fibrosis pathogenesis and therapeutics. Mol Med Rep. 2017;16:7879–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Emmerich P, Matkowskyj KA, McGregor S, Kraus S, Bischel K, Qyli T, et al. VCAN accumulation and proteolysis as predictors of T lymphocyte‐excluded and permissive tumor microenvironments. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:3127. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Estrach S, Cailleteau L, Franco CA, Gerhardt H, Stefani C, Lemichez E, et al. Laminin‐binding integrins induce Dll4 expression and Notch signaling in endothelial cells. Circ Res. 2011;109:172–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Evdokimova V, Ruzanov P, Anglesio MS, Sorokin AV, Ovchinnikov LP, Buckley J, et al. Akt‐mediated YB‐1 phosphorylation activates translation of silent mRNA species. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:277–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mathios D, Hwang T, Xia Y, Phallen J, Rui Y, See AP, et al. Genome‐wide investigation of intragenic DNA methylation identifies ZMIZ1 gene as a prognostic marker in glioblastoma and multiple cancer types. Int J Cancer. 2019;145:3425–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pinnell N, Yan R, Cho H, Keeley T, Murai M, Liu Y, et al. The PIAS‐like coactivator Zmiz1 is a direct and selective cofactor of Notch1 in T cell development and leukemia. Immunity. 2015;43:870–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tschaharganeh D, Xue W, Calvisi D, Evert M, Michurina T, Dow L, et al. p53‐dependent Nestin regulation links tumor suppression to cellular plasticity in liver cancer. Cell. 2014;158:579–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Holczbauer Á, Factor VM, Andersen JB, Marquardt JU, Kleiner DE, Raggi C, et al. Modeling pathogenesis of primary liver cancer in lineage‐specific mouse cell types. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:221–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tanimizu N, Miyajima A. Notch signaling controls hepatoblast differentiation by altering the expression of liver‐enriched transcription factors. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:3165–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lasorella A, Benezra R, Iavarone A. The ID proteins: master regulators of cancer stem cells and tumour aggressiveness. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:77–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yao B, Li Y, Chen T, Niu Y, Wang Y, Yang Y, et al. Hypoxia‐induced cofilin 1 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression by regulating the PLD1/AKT pathway. Clin Transl Med. 2021;11:e366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Travisano SI, Oliveira VL, Prados B, Grego‐Bessa J, Piñeiro‐Sabarís R, Bou V, et al. Coronary arterial development is regulated by a Dll4‐Jag1‐EphrinB2 signaling cascade. Elife. 2019;8:e49977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed in this study are available from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository under the following accession numbers: GSE138709, GSE154170 (GSM5023597 and GSM4665447), GSE115469, TCGA‐CHOL, GSE107943, GSE76297, GSE89749, GSE109774 and Sequence Read Archive (SRA) with the accession number PRJNA743579 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA743579). The other data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. More information about the data were available in the supplementary material.