Abstract

Background

Documentation of patients' goals of care is integral to promoting goal‐concordant care. In 2017, the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) launched a system‐wide initiative to standardize documentation of patients' preferences for life‐sustaining treatments (LST) and related goals‐of‐care conversations (GoCC) that included using a note template in its national electronic medical record system. We describe implementation of the LST note based on documentation in the medical records of patients with advanced kidney disease, a group that has traditionally experienced highly intensive patterns of care.

Methods

We performed a qualitative analysis of documentation in the VA electronic medical record for a national random sample of 500 adults with advanced kidney disease for whom at least one LST note was completed between July 2018 and March 2019 to identify prominent themes pertaining to the content and context of LST notes.

Results

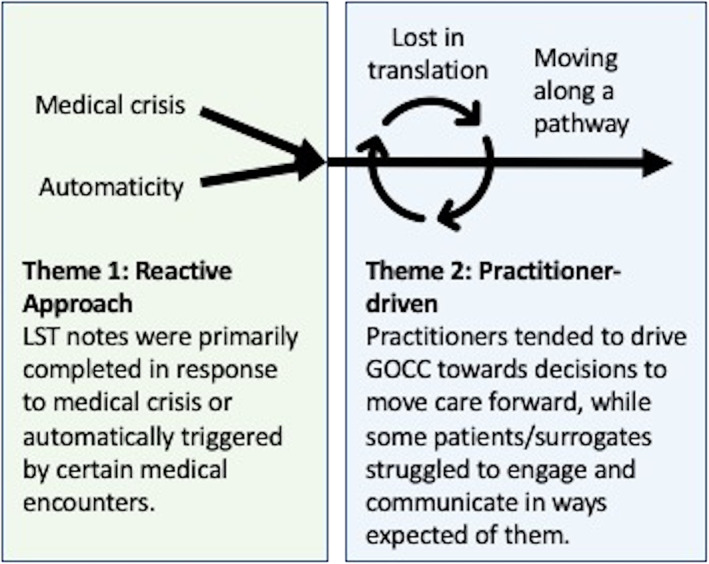

During the observation period, a total of 723 (mean 1.5, range 1–6) LST notes were completed for this cohort. Two themes emerged from the analysis: (1) Reactive approach: LST notes were largely completed in response to medical crises, in which they focused on short‐term goals and preferences rather than patients' broader health and goals, or certain clinical encounters designated by the initiative as “triggering events” for LST note completion; (2) Practitioner‐driven: Documentation suggested that practitioners would attempt to engage patients/surrogates in GoCC to lay out treatment options in order to move care forward, but patients/surrogates sometimes appeared reluctant to engage in GoCC and had difficulty communicating in ways that practitioners could understand.

Conclusions

Standardized documentation of patients' treatment preferences and related GoCC was used to inform in‐the‐moment decision‐making during acute illness and certain junctures in care. There is opportunity to expand standardized documentation practices and related GoCC to address patients'/surrogates' broader health concerns and goals and to enhance their engagement in these processes.

Keywords: advance care planning, kidney disease, nephrology, palliative care, qualitative research

Short abstract

See related Editorial by Naik et al. in this issue.

Key points

A system‐wide initiative to standardize documentation of patients' preferences for treatments intended to prolong life and related goals‐of‐care conservations was primarily implemented to document patients' short‐term care goals and preferences to guide care plans during medical crises and specific types of clinical encounters.

Documentation suggested that patients/surrogates had difficulty engaging in goals‐of‐care conversations and choosing between the options laid out for them by practitioners to move care forward.

Why does this paper matter?

Good documentation of patients' goals of care can support patient autonomy, facilitate decision‐making, and reduce potentially unwanted, costly, and burdensome care. Standardized documentation of patients' preferences for treatments intended to prolong life and related goals‐of‐care conversations can be helpful in guiding in‐the‐moment decision‐making during acute illness and certain healthcare encounters. Our analysis also uncovered opportunities to advance standardized documentation practices and related goals‐of‐care conversations beyond inflection points in care, to address patients' broader health concerns and goals, and in ways that strengthen patient/surrogate engagement in these processes.

INTRODUCTION

Goal‐concordant care is the provision of care that promotes patients' goals and is aligned with what patients hold as most important. 1 The delivery of goal‐concordant care is an important quality metric in health care. 2 Patients' goals and preferences can be recorded in healthcare documents (i.e., advance directives, durable medical power of attorney, and state‐authorized portable orders [SAPO]) with the intent of guiding future care should patients be unable to participate in medical decision‐making. Done well, documentation of patients' goals of care can support patient autonomy, 3 ease clinician and surrogate decision‐making burden, 4 , 5 and reduce potentially unwanted, costly, and burdensome care. 6 , 7

However, existing healthcare documents are imperfect. 8 , 9 , 10 Many patients do not complete an advance directive, 11 and when they do, the documents are not always accessible to clinicians or incorporated into patients' treatment plan. 12 , 13 Advance directives are also not medical orders but statements about preferred care that can be too general to guide treatment decisions in the moment. 14 SAPOs are typically used only by nursing homes and first responders 15 and are less well suited to other clinical contexts. Patients may also have difficulty envisioning future health states and imagining what they might want under those circumstances. 16 The focus on future health states and decision‐making in case of patient incapacity may also miss opportunities to align care with patients' goals and preferences throughout the illness trajectory. 17

To address some of these limitations, in 2017 the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) launched the Life‐Sustaining Treatment (LST) Decisions Initiative (LSTDI), a system‐wide campaign to standardize documentation of patients' preferences for treatments intended to prolong life and related goals‐of‐care conversations (GoCC) from which clarification of these preferences emerged. 18 The VA is the largest integrated health system in the United States, serving over 9 million patients per year at its 1243 facilities, including 170 medical centers, 130 nursing facilities, and 1063 outpatients clinics. As part of the LSTDI, the VA implemented a standardized Life‐sustaining Treatment (LST) note template in its electronic medical record that can be used to document patients' goals and treatment preferences. Once LST notes are completed, patients' documented treatment preferences are executed as medical orders across the entire health system until discontinued or updated. The LST note was developed over several years through the collective input of subject matter and human factors engineering experts in and outside the VA and pilot testing in clinical settings. 19 To support the use of LST notes, the VA developed a dedicated policy handbook (1004.03) and appointed executive teams at each medical center to guide implementation; created an array of educational modules and materials and organized staff training in GoCC and LST note completion; and distributed cognitive aids (e.g. pocket cards) in clinical spaces to reinforce learning and use. Although LST notes can be completed for any patient in any VA care setting and at any time, to promote LST note completion in seriously ill patients, certain clinical scenarios were designated as “triggering events,” such as when patients express wishes regarding treatments intended to prolong life or are perceived to be at high‐risk for a life‐threatening event or at the time of specific healthcare encounters (e.g. admissions, invasive procedures, hospice referral).

The LSTDI offers a unique opportunity to learn about the possibilities and challenges of implementing a system‐wide intervention to improve documentation of patients' treatment preferences and related GoCC. An understanding of how LST notes are used by healthcare practitioners can help to not only guide process improvement within the LSTDI but also inform the design and implementation of other large‐scale programs to promote goal‐concordant care in other health systems. We conducted a quality improvement project to qualitatively analyze documentation pertaining to implementation of LST notes among patients with advanced kidney disease, a group that has traditionally had limited engagement in advance care planning coupled with highly intensive patterns of end‐of‐life care. 20 , 21 , 22

METHODS

Study population

We identified all patients (N = 109,264) who had at least one LST note recorded in the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) between July 2018 and March 2019. Among these, we identified a subset of 5807 (5.3%) with advanced kidney disease, defined as having at least 1 International Classification Disease (ICD)‐10 diagnostic code for end‐stage renal disease or stage 5 chronic kidney disease or a dialysis procedure code in VA inpatient or outpatient files during the year before their first LST note during the observation period. To support feasibility and the exploratory nature of our inquiry and to ensure that the study sample was representative of the wider population of veterans with advanced kidney disease, we assembled a random sample of 500 patients (8.6%) stratified by regional VA Service Network for qualitative analysis of text notes in their electronic medical record.

Approval was not required by the VA Puget Sound Institutional Review Board because this study was undertaken as part of a quality improvement project.

Patient characteristics

We used the CDW to ascertain each patient's age, sex, race, ethnicity, rural vs. urban residence, income, marital status, and most recent Care Assessment Need (CAN) Scores (a validated risk prediction score for 90‐day and 1‐year risk of hospitalization and mortality that is based on structured demographic and clinical data in the electronic medical record) 23 at the time of their first LST note during the observation period. We also ascertained whether patients had at least two ICD‐10 codes for end‐stage liver disease, cancer, cardiovascular disease, or dementia during the year prior; a specialty palliative care consultation or emergency room visit in the year prior; and been hospitalized in the month before their index LST note.

LST note characteristics

The LST note template consists of eight fields, four of which are mandatory and require responses to questions with specific options (Table S1). Practitioners must check boxes to indicate whether patients had decision‐making capacity at the time of note completion (“yes” or “no”), their goals of care (“to be cured” of illness, “to prolong life”, “to improve or maintain function, independence and quality of life”, “to be comfortable”, “to obtain support for family/caregiver” or “other”), who provided informed consent to complete the LST note (“patient”, “surrogate” or “other”), and resuscitation preferences (“full code”, “do not resuscitate” or “do not resuscitate with exceptions”). In addition to these mandatory fields, there are also optional fields in which practitioners can include information on preferences for mechanical and noninvasive ventilation, artificial nutrition and hydration, hospital and intensive care unit transfers, and other interventions. Practitioners can also add free‐text comments to LST notes. We ascertained practitioner entries to prespecified fields for each patient's index LST note and the clinical setting in which the note was completed.

Qualitative data collection

From the CDW, we retrieved all clinical notes, including LST notes, for all episodes of care at VA facilities during the year before the initial LST note within the observation period through the date of death or March 31, 2019 (whichever came first). Using a previously published approach, 24 , 25 , 26 we used Lucene text‐search software 27 to mine all acquired notes for information on the content and context of LST notes.

First, S.P.Y.W. (a nephrologist and experienced qualitative researcher) reviewed all acquired notes collected for a random sample of 90 veterans selected for chart review and abstracted passages containing information documented in narrative form on the circumstances in which LST notes were completed and related GoCC, defined as “conversations between a health care practitioner and a patient or surrogate for the purpose of determining the patient's values, goals, and preferences for care, and, based on those factors, making decisions about whether to initiate, limit, or discontinue LST.” 19 , 28 , 29 Our prior experience using this technique indicated that a single abstractor of chart passages is sufficient in reliably identifying relevant passages on a select subject matter. 30 Based on review of abstracted passages, S.P.Y.W. developed a compendium of note titles, words, and phrases used to document GoCC (Table S2). A second author (A.M.O, a nephrologist and experienced qualitative researcher) provided input on the search strategy after reviewing all acquired notes alongside the subset of notes identified by Lucene software for 10 patients. S.P.Y.W. then used the final set of search terms to query the acquired progress notes for the remaining patients selected for chart review to identify all potentially relevant notes for review and abstraction.

Qualitative analysis

We used an inductive approach to content analysis to analyze abstracted chart passages. Inductive content analysis is an unstructured method of inquiry that facilitates discovery of previously unidentified factors pertaining to a phenomenon. 31 First, S.P.Y.W. reviewed all passages for each patient, openly coding for emergent themes pertaining to the content and context of LST notes and documented GoCC. A.M.O. independently reviewed the abstracted passages for a subset of 66 patients, and using a consensus‐based approach, worked with S.P.Y.W. to refine theme definitions and constructs and resolve any uncertainties in interpretation of passages. Using the final codebook, T.O. (health educator with training in qualitative research) independently reviewed the abstracted passages for all 500 patients and confirmed that no new codes had emerged (i.e., data saturation). 32 To support interpretation of the data from diverse perspectives, 33 S.P.Y.W., A.M.O., M.B.F., (nurse and ethicist), and J.C. (epidemiologist and policy analyst) met regularly to review and discuss emergent themes, assemble themes into larger thematic categories, and provide input on the final thematic schema. Throughout the process, we recorded analytical and theoretical memos to capture our thought processes and observations of the data. Prominent themes presented were selected on the basis of the consistency with which they appeared in passages. 34 We used Atlas.ti qualitative analysis software v.8 (GmbH; Berlin, Germany) to facilitate organization of codes, memos, and abstracted passages.

RESULTS

For the 500 patients (age 72 ± 11 years; 97.4% male; 33.6% black) included in the chart review (Table S3), a total of 723 (mean 1.5, range 1–6) LST notes were completed during the observation period (Table S4). Most LST notes were completed in the inpatient setting (58.4%) or emergency department (9.8%).

Two prominent themes emerged from qualitative analysis reflecting the content and context of LST notes (Figure 1): (1) Reactive approach: LST notes were usually completed in response to health crisis or other inciting medical events; and (2) Practitioner‐driven: Within documentation in clinical progress notes surrounding LST notes, practitioners described efforts to engage patients/surrogates in GoCC to identify options to move care forward. Exemplary quotes from the medical records of unique patients are presented in Tables 1, 2, 3, 4.

FIGURE 1.

Prominent themes reflecting the content and context of standardized notes to document patients' preferences for life‐sustaining treatments (LST) and related goals‐of‐care conversations (GoCC)

TABLE 1.

Theme: Reactive approach – Crisis‐oriented

| Quote | Exemplar passages from notes | Note title; setting; service (day) |

|---|---|---|

| 1a |

PATIENT'S GOALS OF CARE Goals are not listed in order of priority “I want to garden, sightsee and enjoy the sun in [state] with my wife” ‐To improve or maintain function, independence, quality of life PLAN FOR LIFE‐SUSTAINING TREATMENTS [blank] CARDIOPULMONARY RESUSCITATION Full code: Attempt CPR. |

LST; Outpatient; Home‐based primary care |

| 1b |

PATIENT'S GOALS OF CARE Goals are not listed in order of priority. Did not address comprehensive goals, goal for this admission is to go home. PLAN FOR LIFE‐SUSTAINING TREATMENTS [blank] CARDIOPULMONARY RESUSCITATION Full code: Attempt CPR. |

LST; Inpatient; Medicine |

| 1c |

PATIENT'S GOALS OF CARE Goals are not listed in order of priority. ‐To prolong life ‐To improve or maintain function, independence, quality of life ‐To be comfortable PLAN FOR LIFE‐SUSTAINING TREATMENTS Limit life‐sustaining treatment as specified in circumstances OTHER than cardiopulmonary arrest: No artificial nutrition (enteral or parenteral) No invasive mechanical ventilation (e.g. endotracheal or tracheostomy tube) CARDIOPULMONARY RESUSCITATION Full code: Attempt CPR. |

LST; Inpatient; Medicine |

|

1d |

his quality of life has worsened because he is so fatigued the rest of the day after HD and he is no longer able to work or to play golf, the two things he loved…he “knows his time is limited…” Patient has started to think about his goals for his medical care going forward and about what an acceptable quality of life means to him. He is starting to place limits on life‐sustaining treatments (newly DNAR, no mechanical ventilation) and is contemplating next steps. | Progress; Inpatient; Palliative Care (0) |

|

PATIENT'S GOALS OF CARE Goals are not listed in order of priority. ‐To improve or maintain function, independence, quality of life ‐To be comfortable PLAN FOR LIFE‐SUSTAINING TREATMENTS [blank] CARDIOPULMONARY RESUSCITATION DNAR/DNI: Do not attempt CPR. |

LST; Inpatient; Palliative Care (0) | |

|

1e |

He states he will not have hemodialysis if needed. | Progress; Outpatient; Cardiology (0) |

|

PATIENT'S GOALS OF CARE: Goals are not listed in order of priority. ‐To be comfortable PLAN FOR LIFE‐SUSTAINING TREATMENTS [blank] CARDIOPULMONARY RESUSCITATION DNR: Do not attempt CPR. |

LST; Inpatient; Rehabilitative Medicine (+121) | |

| 1f | Patient is scheduled for another dialysis session today after which plan is for discharge…He will occasionally say he wants to stop dialysis…This conversation can be had in the outpatient setting with palliative care. | Progress; Inpatient; Medicine |

| 1g |

PATIENT'S GOALS OF CARE: Goals are not listed in order of priority. ‐Family relations are his most important variable ‐To prolong life ‐To improve or maintain function, independence, quality of life PLAN FOR LIFE‐SUSTAINING TREATMENTS Limit life‐sustaining treatment as specified in circumstances OTHER than cardiopulmonary arrest: No artificial nutrition (enteral or parenteral) Limit artificial hydration as follows: accepts trial of IVF No invasive mechanical ventilation (e.g. endotracheal or tracheostomy tube) CARDIOPULMONARY RESUSCITATION DNR: Do not attempt CPR. |

LST; Outpatient; Palliative Care |

Abbreviations: LST, life‐sustaining treatment; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; ICU, intensive care unit; HD, hemodialysis; IVF, intravenous fluids.

TABLE 2.

Theme: Reactive approach – Checklist approach

| Quote | Exemplar passages from notes | Note title; setting; service (day) |

|---|---|---|

| 2a |

PATIENT'S GOALS OF CARE Goals are not listed in order of priority. I give my permission for my husband to have the procedure PLAN FOR LIFE‐SUSTAINING TREATMENTS [blank] CARDIOPULMONARY RESUSCITATION DNR with exception for all interventional radiology procedures including today's diagnostic lumbar puncture. |

LST; Inpatient; Medicine |

| 2b | Today, we discussed provisions of dialysis and his prescription. He was given the opportunity to provide input into his treatment goals and future plan of care. We also completed his life‐sustaining treatment choices preferences and documented them in CPRS. He is aware that he can change these at any time in the future. | Dialysis; Dialysis Unit; Nephrology (0) |

|

PATIENT'S GOALS OF CARE: Goals are not listed in order of priority. ‐To be cured of: Any illnesses that could be treated ‐To prolong life ‐To be comfortable ‐To obtain support for family/caregiver ‐To achieve life goals, including: Would like to improve exercise capacity PLAN FOR LIFE‐SUSTAINING TREATMENTS FULL SCOPE OF TREATMENT in circumstances OTHER than cardiopulmonary arrest. CARDIOPULMONARY RESUSCITATION Full code: Attempt CPR. |

LST; Dialysis Unit; Nephrology (0) | |

| 2c |

PATIENT'S GOALS OF CARE: Goals are not listed in order of priority. ‐Want to find another way for patient to have diuresis, vascular catheter clogged and they wanted to fix it. PLAN FOR LIFE‐SUSTAINING TREATMENTS FULL SCOPE OF TREATMENT in circumstances OTHER than cardiopulmonary arrest. CARDIOPULMONARY RESUSCITATION DNR: Do not attempt CPR. |

LST; Inpatient; Medicine |

| 2d |

PATIENT'S GOALS OF CARE Goals are not listed in order of priority. Find me another facility. I do not want to go back to [nursing home] PLAN FOR LIFE‐SUSTAINING TREATMENTS FULL SCOPE OF TREATMENT in circumstances OTHER than cardiopulmonary resuscitation. CARDIOPULMONARY RESUSCITATION Full code: Attempt CPR. |

LST; Community Living Center; Long‐term care |

| 2e | When asked if patient would want CPR and chest compressions, he stated “No man I already told you that.” When asked if he would want ICU level care including intubation and pressors the patient states “leave me alone man…” We will need to re‐address his code status at a later time. | DNR; Inpatient; Medicine |

| 2f |

Full support: Curative treatment + Full code. Discussion with patient and/or family: per discussion with the patient, he would like to receive acute cardiopulmonary life support in the event of a cardiopulmonary arrest. |

Advance Directive Discussion; Inpatient; Social Work (0) |

|

PATIENT'S GOALS OF CARE Goals are not listed in order of priority. ‐To improve or maintain function, independence, quality of life PLAN FOR LIFE‐SUSTAINING TREATMENTS Limit life‐sustaining treatment as specified in circumstances OTHER than cardiopulmonary arrest: Limit artificial nutrition as follows: Short trial. Would not want long‐term artificial feeding. Limit mechanical ventilation as follows: Short trial. Would not want long‐term ventilatory support. CARDIOPULMONARY RESUSCITATION Full code: Attempt CPR. |

LST; Inpatient; Palliative Care (+1) |

Abbreviations: LST, life‐sustaining treatment; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; CPRS, Computerized Patient Record System; ICU, intensive care unit; DNR, do not resuscitate; DNAR, do not attempt resuscitation; DNI, do not intubate; HD, hemodialysis.

TABLE 3.

Theme: Practitioner‐driven – Moving along the pathway

| Quote | Exemplar passages from notes | Note title; setting; service (day) |

|---|---|---|

| 3a | family meetings held to discuss best path forward for [patient]. He has been anorexic for weeks with significant weight loss, decreasing cognition, refusing medications and persistent hypotension…All of these indicate that veteran's body is wearing down and that his life expectancy is less than 6 months. | Consult; Inpatient; Palliative Care |

| 3b | his [dialysis center] will not accept him on hospice and will likely be unable to dialyze him with SBP in the 80s. Altogether, it seems that the patient's heart failure is preventing dialysis and the most reasonable path forward is home hospice without dialysis. I discussed this with palliative care and we will discuss it as a team this afternoon or tomorrow | Progress; Inpatient; Medicine |

| 3c | Wife brought in orange DNR or medical determination form to complete. Patient would not commit to any decision on his care or the suspension of care. He states it depends on how sick he is. | Progress; Outpatient; Primary Care |

| 3d | [Nephrologist] reviewed [patient's] clinical course over the last several months and stated that dialysis is hurting [patient] and that he would not recommend replacing his dialysis catheter. [Wife] was noticeably silent during this and avoiding eye contact with anyone. [Hospitalist] recommended that veteran be transferred to [hospice ward] and we focus on his comfort. I acknowledged [wife's] silence and affirmed the struggle she has had with this process | Consult; Inpatient; Palliative Care |

| 3e | Palliative Care suggested a family meeting with patient's decision makers/care providers, hospitalist team and palliative care in order for all to be “on the same page” with regard to patient's discharge care plan. | Progress; Inpatient; Social Work (0) |

| They all voiced their opinion that, although they want him to be comfortable, they are not yet ready for comfort‐focused care at the end of life. They wish to pursue physical therapy and continue hemodialysis. | Progress; Inpatient; Palliative Care (+1) | |

| We have previously discussed the hospice philosophy of care, and he is not yet ready to choose this type of care…Please place an Ethics consult today and speak with Chief of Staff to address the ethical dilemma of continuing HD in this patient with ESRD where it is felt that placing another tunneled catheter is not in the patient's best interest. | Consult; Inpatient; Palliative Care (+43) | |

| [Son] reports feeling torn about the circumstances and wants to “fight” for his father to get better….After more discussions, he eventually agreed to enroll his father in hospice | Consult; Inpatient; Palliative Care (+48) | |

| 3f | Patient remains somewhat confused with limited insight. Reviewed current treatment plan and goals of care. To continue aggressive interventions and reassess. | Progress; Inpatient; Cardiology (0) |

| Plan to have a meeting with family on Monday regarding options for hospice but daughter said that her dad needs dialysis. | Progress; Inpatient; Medicine (+21) | |

| I have discussed hospice option again with daughter today. | Consult; Inpatient; Palliative Care (+74) | |

| [Patient] insists that he wants to live and intends to “fight” his multiple medical comorbidities. | Consult; Inpatient; Mental Health (+75) | |

| I explained what CPR would look like including pain, chest trauma (rib fracture, lung/spleen trauma, electric shock), invasive procedures including with multiple IV access lines, a tube in nose to lung attached to another machine besides his dialysis machine. I explained that this would not be a dignified way to die or comfortable way to die. | Progress; Inpatient; Palliative Care (+96) | |

| Goals of care discussion yesterday, still full code…Continue goals of care discussion every other day. | Progress; Inpatient; Medicine (+98) | |

| Given decline in clinical condition and overall poor prognosis, patient was made DNR in the afternoon after discussion with the patient and his daughter. | Progress; Inpatient; Medical Intensive Care (+104) |

Abbreviations: LST, life‐sustaining treatment; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; DNR, do not resuscitate; HD, hemodialysis; IV, intravenous.

TABLE 4.

Theme: Practitioner‐driven – Lost in translation

| Quote | Exemplar passages from notes | Note title; setting; service |

|---|---|---|

| 4a | [Patient] is a difficult patient to interpret, he clearly does not wish to pursue work up of cancer and is cognizant that this may impact life expectancy. In fact, this morning [patient] reported he was “ready to leave this world” and did not want aggressive medical intervention. He stated he was no suicidal and did not want complete removal of medical therapy at this time. He wants to continue with dialysis, yet he clearly states multiple times he does not wish to prolong things. I offered him palliative care consultation and explained to him what those services were about, he refused to see palliative care and did not wish to pursue end‐of‐life care. | Progress; Inpatient; Medicine |

| 4b | Had a lengthy conversation with [patient] about refusing hemodialysis. He was sitting at side of bed and acknowledged that he refused dialysis but when asked why, he does not have an answer. He continues to say that he does not like needles. | Progress; Community Living Center; Long‐term Care |

| 4c | He is able to articulate what would happen if he stopped dialysis, “I will die,” and he is able to articulate what might happen if he continues to not take his medicines, “I might die,” but is unable to explain why he would want to continue dialysis and not take his medicines…He cannot articulate higher level concepts regarding his health such as diet management, what his actual goals are other than, “I want to live,” he cannot connect the dots between saying “I want to live” and doing things that actually might prevent that. | Consult; Inpatient; Palliative Care |

| 4d | [patient] unfortunately has only a basic grasp on his medical problems and diagnosis. He does know that he has pancreatic cancer that is in his belly. When told it was incurable, he asked if “juice” could help. | Consult; Inpatient; Hematology and Oncology |

| 4e | I explained my concern with her that the infection is not going to be curable, especially without surgical intervention. She became very upset stating she did not want me to mention another surgery at this time…When I asked what are her goals of care, she did not understand my questions…I explained to her a few different options depending on her overall goals of care…[Patient] is not ready to discuss an option that does not involve being in the hospital (or a nursing home) for antibiotic therapy. | Progress; Inpatient; Medicine |

| 4f | He tells me if he cannot get a [kidney transplant] then “I am done,” meaning he wants to stop dialysis…He did a 5K walk at [place] and met [celebrity]. He tells me it was the best day of his life…He bought [sport team] season tickets for next year. I decided not to point out the inconsistency of buying season tickets and wanting to stop dialysis…We discuss stopping dialysis each time, but each time he describes a nice quality of life and enjoying himself. | Progress; Outpatient; Geriatric Medicine |

| 4 g | Call to [city] policy to do a wellness check on veteran. Per officer, veteran “sounded fine.” The officer states that veteran feels dialysis is making him sick and states also that he has concerns about the fluid that is taken out during dialysis treatments. Veteran is also reported to have said he feels his concerns are not being listened to. I called his listed number today and asked for him to call back to discuss his goals of care and care plan. | Telephone; Dialysis Unit; Nephrology |

Abbreviations: LST, life‐sustaining treatment; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; DNR, do not resuscitate; HD, hemodialysis; IV, intravenous.

Reactive approach

LST notes were primarily completed during health crises in which documentation typically focused on code status and short‐term treatment goals (Table 1). Outside crisis settings, LST note completion seemed automatically triggered during designated clinical encounters (Table 2).

Crisis‐oriented

Although LST notes were sometimes completed proactively to address patients' big picture goals and care preferences in advance of illness (Table 1, quote 1a), more commonly these notes were completed in response to medical crisis and tended to address code status, short‐term goals, and immediate treatment plans (quote 1b). In this context, practitioners tended to complete only the mandatory fields in the note template. Practitioners might check a number of boxes within the LST note template to indicate different patient goals and/or treatment preferences, but generally did not include further information about how patients prioritized potentially conflicting or contradictory goals and preferences (quote 1c). More detailed documentation of patients' goals and preferences were not recorded in the LST notes themselves but usually could be found in surrounding progress notes (quote 1d). Major treatment decisions that had been made but were not listed in the note template, such as dialysis, typically did not appear in LST notes when not relevant to the immediate context of care (quote 1e). In the absence of a crisis, practitioners routinely deferred addressing patients' broader health concerns and goals to other settings and practitioners (quote 1f). When addressed, practitioners might include free‐text comments to describe patients' broader concerns and goals in addition to selecting prespecified options in the note template (quote 1g).

Automaticity

Consistent with the guidance offered by the LSTDI, LST notes seemed automatically triggered by certain types of interactions with the health system such as upcoming procedures, admissions, and hospital transfers (Table 2, quote 2a). It was rare to find practitioners who incorporated completion of LST notes into clinical encounters outside of those advised by the LSTDI, such as part of routine outpatient visits (quote 2b). When completed in response to designated “triggering events,” the need to complete an LST note did not always seem relevant to the patient's presenting health concern (quote 2c). LST notes might be repeatedly entered in the medical record with each of these encounters even when patients' code status had not changed and regardless of how sick they were (quote 2d) or whether they were open to engaging in these conversations (quote 2e). We also observed that LST note completion occurred in parallel with related efforts to complete other healthcare documents. For instance, practitioners completing LST notes seemed to work separately from social workers' efforts to document advance directives with the same patients around the same time of hospital admission (quote 2f).

Practitioner‐driven

Documentation in clinical progress notes surrounding LST notes suggested that practitioners would engage patients/surrogates in GoCC, expecting patients/surrogates to choose between the different treatment options presented to move care forward (Table 3). However, documentation in clinical notes sometimes spoke to communication challenges between patients/surrogates and practitioners. (Table 4).

Moving along a pathway

When patients were seriously ill and/or reached an impasse in their illness, practitioners typically arranged a GoCC with patients/surrogates to lay out possible “paths forward” for care (Table 3, quote 3a). In some cases, there seemed few, if any, options for patients/surrogates to choose between (quote 3b). We saw many examples of documentation in which patients/surrogates were described as unwilling or unable to make a decision (quote 3c) or follow practitioners' recommendations (quote 3d). Some practitioners made multiple attempts to engage patients/surrogates in GoCC to bring patients/surrogates onto the “same page” (quote 3e). In some cases, repeated GoCC sometimes continued until patients/surrogates could finally make a choice and/or accept practitioners' recommendations (quote 3f).

Lost in translation

We found multiple instances where patients/surrogates communicated their goals and preferences in ways that practitioners did not understand (Table 4, quote 4a). Documentation suggested that patients/surrogates sometimes responded to questions in ways that did not make sense (quote 4b) or were unexpected (quote 4c) to practitioners, leaving them wondering whether patients/surrogates had “grasped” the meaning of conversations (quote 4d). Documentation also suggested that patients sometimes did not understand what practitioners were hoping to accomplish in GoCC (quote 4e). Practitioners tended to attribute challenges with understanding patients' goals and preferences to perceived “inconsistencies” in what patients/surrogates had said (quote 4f). On occasion, we found explicit mention of patients/surrogates expressing that they were not being listened to (quote 4g).

DISCUSSION

This study provides an informative window on a system‐wide intervention to support standardized documentation of patients' preferences for treatments intended to prolong life and related GoCC in a large US health system and the content and context of this documentation. Our findings yielded several important insights about the LSTDI that may also be useful to other efforts to design system‐level interventions intended to cultivate broad practice change around documentation of patients' goals and treatment preferences.

Efforts to promote goal‐concordant care have largely centered on advance care planning, which is an anticipatory process that supports patients at any stage of health by clarifying their values, goals, and preferences for future care in the event of serious illness. 35 However, there is controversy about the strength of evidence to support advance care planning, 17 , 36 with some arguing to redirect efforts toward reconfiguring health systems around what is most important to patients and helping patients/surrogates make decisions that best align with their values throughout their illness course. 37 , 38 In this regard, the LSTDI's system‐wide design and emphasis on GoCC to inform care plans in real time seem forward‐thinking and may help to inform the wider discourse around how best to promote goal‐concordant care.

Consistent with the intended goals of the LSTDI, we found that LST notes provided actionable information about patients' goals and treatment preferences and served to guide in‐the‐moment decision‐making, especially during medical crisis. In this capacity, LST notes fill an important gap among existing healthcare documents. At the same time, it is important to distinguish that the LST notes were used as summary documents and not as centralized repositories for documentation of patients' treatment preferences and related GoCC. We found documentation within LST notes was usually limited to general categories of patients' goals and preferences defined by the note template and functioned more as signposts in the medical record for where more detailed documentation about related GoCC in surrounding progress notes could be found. The need to document patients' goals and treatment preferences could be elicited by designated triggering events independent of patients' presenting health concern or predisposition to have these conversations, but could also omit related treatment decisions, such as dialysis, when not specifically prompted within the note template. Our analyses also suggest that there might be missed opportunities to use LST notes to record patients' broader health concerns and goals and to integrate practitioner efforts to complete LST notes with related efforts to complete advance directives. We suspect that these patterns of LST note completion might stem from the LST note template design itself, implementation strategies, and/or practitioner behaviors, and thus point to targets for further action to create more cohesive approaches to GoCC documentation.

Our findings also spotlight approaches to GoCC that may be less amenable to changes to the LSTDI or LST note themselves. Documentation in clinical progress notes surrounding LST notes suggested that related GoCC were primarily driven by practitioners to guide patients/surrogates toward a pathway forward in care when patients' clinical status deteriorated or reached an impasse. However, we found many instances in which patients/surrogates did not seem ready or able to engage in these GoCC and had difficulty communicating their goals and preferences to practitioners. Although patients generally appreciate GoCC, 39 , 40 , 41 many also struggle to tolerate emotionally‐laden discussions and process complex information about prognosis and treatment options when they are seriously ill. 42 In this context, practitioners have a strong role in framing illness and treatment options for seriously ill patients and shaping patients'/surrogates' perception of their options, decision‐making, and end‐of‐life experiences. 43 , 44 , 45 Although the LSTDI incorporated some practitioner communication training in GoCC at its outset, uptake of these skills and their maintenance over time can be highly variable. 46 Outside of efforts targeted at practitioners, there has also been work to develop patient‐ and surrogate‐facing interventions aimed at preparing them for GoCC and cultivating a sense of empowerment to have these conversations. 47 Taken together, our findings provide impetus to expand system‐level efforts to include bolstering practitioner training in serious illness communication and patient/surrogate engagement in GoCC.

The findings of this study should be considered with several limitations in mind. First, the medical record includes detailed documentation related to care, communication, and accountability. It also captures care as it unfolds and enables study of a range of clinician types and settings that are relevant to decision‐making across the illness trajectory. This technique has advantages over interviews with patients/surrogates and practitioners after the fact, which are subject to recall bias, and direct observation of clinical encounters, which can influence patient/surrogate and practitioner behaviors (i.e., Hawthorne effect). 48 Nonetheless, what can be learned from the medical record is also limited to what practitioners choose to document, which might not completely or accurately reflect patients' goals and preferences, what transpired in a particular clinical encounter, or patients'/surrogates' perspectives or experiences. Second, our findings may have limited transferability to non‐VA settings. Third, our analysis was restricted to patients with advanced kidney disease who had at least one LST note during the observation period and to GoCC documented around the time an LST note was completed, and therefore may not speak to documentation practices for other patients or for other conversations about patients' goals and treatment preferences separate from LST note completion. Fourth, our findings reflect only the most prominent themes that emerged from the chart notes and are not exhaustive of all themes pertaining to documentation processes related to LST notes. Fifth, owing to the complexity of themes and incomplete documentation in the medical record, our findings do not lend themselves to the kind of precise categorization needed to quantify the frequency of each theme among cohort members or estimate differences in themes between different patient groups.

In conclusion, a system‐wide initiative to standardize documentation of patients' preferences for treatments intended to prolong life and related GoCC was implemented in a reactive fashion to guide in‐the‐moment decision‐making during medical crisis and during “triggering” clinical events. These GoCC also appeared to be highly driven by practitioners who sometimes were not attuned to patients'/surrogate' readiness or ability to engage in these conversations. Our findings point to opportunities to expand standardized documentation practices for patients' treatment preferences and related GoCC beyond inflection points in care, to address patients' broader health concerns and goals, and in ways that strengthen patient/surrogate engagement in these processes.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors disclose no conflict of interests. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the position or policy of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, the United States government, or VA National Center for Ethics in Health Care.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Susan P. Y. Wong, Ann M. O'Hare designed the study, with advice and input from Mary Beth Foglia and Jennifer Cohen. Susan P. Y. Wong, Mary Beth Foglia, Jennifer Cohen acquired the data. All authors took part in data analyses and interpretation. Susan P. Y. Wong wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript. Susan P. Y. Wong acts as guarantor of the manuscript.

SPONSOR'S ROLE

This study was made possible by the VA National Center for Ethics in Health Care and the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. Neither funding source had a role in the design, conduct, or reporting of the study.

Supporting information

Table S1 Fields in the LST template note

Table S2. Query note titles and terms

Table S3. Patient characteristics at time of first LST note

Table S4. Characteristics of first LST note

Wong SPY, Foglia MB, Cohen J, Oestreich T, O'Hare AM. The VA Life‐Sustaining Treatment Decisions Initiative: A qualitative analysis of veterans with advanced kidney disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022;70(9):2517‐2529. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17807

See related Editorial by Naik et al. in this issue.

Funding information Doris Duke Charitable Foundation; VA National Center for Ethics in Health Care

REFERENCES

- 1. Halpern SD. Goal‐concordant care ‐ searching for the holy grail. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(17):1603‐1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dzau VJ, McClellan MB, McGinnis JM, et al. Vital directions for health and health care: priorities from a National Academy of Medicine Initiative. JAMA. 2017;317(14):1461‐1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Houben CHM, Spruit MA, Groenen MTJ, Wouters EFM, Janssen DJA. Efficacy of advance care planning: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15(7):477‐489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lewis E, Cardona‐Morrell M, Ong KY, Trankle SA, Hillman K. Evidence still insufficient that advance care documentation leads to engagement of healthcare professionals in end‐of‐life discussions: a systematic review. Palliat Med. 2016;30(9):807‐824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tong A, Cheung KL, Nair SS, Kurella Tamura M, Craig JC, Winkelmayer WC. Thematic synthesis of qualitative studies on patient and caregiver perspectives on end‐of‐life care in CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;63(6):913‐927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brinkman‐Stoppelenburg A, Rietjens JA, van der Heide A. The effects of advance care planning on end‐of‐life care: a systematic review. Palliat Med. 2014;28(8):1000‐1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dixon J, Matosevic T, Knapp M. The economic evidence for advance care planning: systematic review of evidence. Palliat Med. 2015;29(10):869‐884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fagerlin A, Schneider CE. Enough: the failure of the living will. Hast Center Rep. 2004;34(2):30‐42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Moore KA, Rubin EB, Halpern SD. The problems with physician orders for life‐sustaining treatment. JAMA. 2016;315(3):259‐260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sabatino CP. The evolution of health care advance planning law and policy. Milbank Quart. 2010;88(2):211‐239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yadav KN, Gabler NB, Cooney E, et al. Approximately one in three US adults completes any type of advance directive for end‐of‐life care. Health Aff. 2017;36(7):1244‐1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Morrison RS, Olsen E, Mertz KR, Meier DE. The inaccessibility of advance directives on transfer from ambulatory to acute care settings. JAMA. 1995;274:478‐482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hardin SB, Yusufaly YA. Difficult end‐of‐life treatment decisions. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1631‐1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sudore RL, Fried TR. Redefining the “planning” in advance care planning: preparing for end‐of‐life decision making. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(4):256‐261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hickman SE, Keevern E, Hammes BJ. Use of the physician orders for life‐sustaining treatment program in the clinical setting: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(2):341‐350. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Morrison RS. Advance directives/care planning: clear, simple, and wrong. J Palliat Med. 2020;23(7):878‐879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Morrison RS, Meier DE, Arnold RM. What's wrong with advance care planning? JAMA. 2021;326:1575‐1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Foglia MB, Lowery J, Sharpe VA, Tompkins P, Fox E. A comprehensive approach to eliciting, documenting, and honoring patient wishes for care near the end of life: the Veterans health Administration's Life‐Sustaining Treatment decisions initiative. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2019;45(1):47‐56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Handbook VHA. 1004.03(2) Life‐Sustaining Treatment Decisions: Eliciting =, Documenting and Honoring patients' Values, Goals and Preferences. Department of Veterans Affairs; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu CY. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(13):1296‐1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wong SP, Kreuter W, O'Hare AM. Healthcare intensity at initiation of chronic dialysis among older adults. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25(1):143‐149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wong SP, Kreuter W, O'Hare AM. Treatment intensity at the end of life in older adults receiving long‐term dialysis. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(8):661‐663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wang L, Porter B, Maynard C, et al. Predicting risk of hospitalization or death among patients receiving primary care in the Veterans Health Administration. Med Care. 2013;51(4):368‐373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wong SPY, McFarland LV, Liu CF, Laundry RJ, Hebert PL, O'Hare AM. Care practices for patients with advanced kidney disease who forgo maintenance dialysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(3):305‐313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Butler CR, Wightman A, Richards CA, et al. Thematic analysis of the health records of a National Sample of US Veterans with advanced kidney disease evaluated for transplant. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(2):212‐219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. O'Hare AM, Butler CR, Taylor JS, et al. Thematic analysis of hospice mentions in the Health Records of Veterans with advanced kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31:2667‐2677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hammond KW, Laundry RJ, O'Leary TM, Jones WP. Use of text search to effectively identify lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts among veterans. 46th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers; 2013:2676‐2683. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bradshaw CL, Gale RC, Chettiar A, et al. Medical record documentation of goals‐of‐care discussions among older veterans with incident kidney failure. Am J Kidney Dis. 2019;75:744‐752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lindvall C, Lilley EJ, Zupanc SN, et al. Natural language processing to assess end‐of‐life quality indicators in cancer patients receiving palliative surgery. J Palliat Med. 2019;22(2):183‐187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wong SP, Vig EK, Taylor JS, et al. Timing of initiation of maintenance dialysis: a qualitative analysis of the electronic medical Records of a National Cohort of patients from the Department of Veterans Affairs. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(2):228‐235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Krippendorff K. Content Analysis: an Introduction to its Methodology. 3rd ed. Sage Publications; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, et al. Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual Quant. 2018;52(4):1893‐1907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Giacomini MK, Cook DJ. Users' guides to the medical literature: XXIII. Qualitative research in health care a. are the results of the study valid? Evidence‐based medicine working group. JAMA. 2000;284(3):357‐362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ryan GW, Bernard HR. Techniques to identify themes. Field Methods. 2003;15(1):85‐109. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sudore RL, Lum HD, You JJ, et al. Defining advance care planning for adults: a consensus definition from a multidisciplinary Delphi panel. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53(5):821‐832 e821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jimenez G, Tan WS, Virk AK, Low CK, Car J, Ho AHY. Overview of systematic reviews of advance care planning: summary of evidence and global lessons. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;56(3):436‐459 e425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jacobsen J, Bernacki R, Paladino J. Shifting to serious illness communication. JAMA. 2022;327(4):321‐322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Periyakoil VS, Gunten CFV, Arnold R, Hickman S, Morrison S, Sudore R. Caught in a loop with advance care planning and advance directives: how to move forward? J Palliat Med. 2022;25(3):355‐360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Saeed F, Sardar MA, Davison SN, Murad H, Duberstein PR, Quill TE. Patients' perspectives on dialysis decision‐making and end‐of‐life care. Clin Nephrol. 2019;91(5):294‐300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Goff SL, Eneanya ND, Feinberg R, et al. Advance care planning: a qualitative study of dialysis patients and families. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(3):390‐400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Davison SN. Facilitating advance care planning for patients with end‐stage renal disease: the patient perspective. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1(5):1023‐1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Jackson VA, Jacobsen J, Greer JA, Pirl WF, Temel JS, Back AL. The cultivation of prognostic awareness through the provision of early palliative care in the ambulatory setting: a communication guide. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(8):894‐900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tulsky JA, Fischer GS, Rose MR, Arnold RM. Opening the black box: how do physicians communicate about advance directives. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129(6):441‐449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kaufman SR. And a time to die. How American Hospitals Shape the End of Life. University of Chicago Press Books; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hussain JA, Flemming K, Murtagh FE, Johnson MJ. Patient and health care professional decision‐making to commence and withdraw from renal dialysis: a systematic review of qualitative research. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(7):1201‐1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Moore PM, Rivera S, Bravo‐Soto GA, Olivares C, Lawrie TA. Communication skills training for healthcare professionals working with people who have cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;2018(7):CD003751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sudore RL, Schillinger D, Katen MT, et al. Engaging diverse English‐ and Spanish‐speaking older adults in advance care planning: the PREPARE randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(12):1616‐1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sedgwick P, Greenwood N. Understanding the Hawthorne effect. BMJ. 2015;351:h4672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Fields in the LST template note

Table S2. Query note titles and terms

Table S3. Patient characteristics at time of first LST note

Table S4. Characteristics of first LST note