Abstract

The present research focuses on the role of collective, social influence and intraindividual processes in shaping preventive behaviours during the COVID‐19 pandemic. In two correlational studies conducted in Spain, we explored the impact of participation in the ritual of collective applause (carried out daily for over 70 days during the lockdown) and perceived social norms in fostering behavioural adherence to public health measures, as well as the mediating role of perceived emotional synchrony and a sense of moral obligation. The first study (general population, N = 528) was conducted in June 2020, just after the end of the lockdown, and the second study (students, N = 292) was carried out eight months later. The results of the structural equations modelling (SEM) consistently confirmed that active participation in collective applause was linked to more intense emotional synchrony and indirectly predicted self‐reported preventive behaviour. Perceived social norms predicted self‐reported behavioural compliance directly and also indirectly, via feelings of moral obligation. The discussion addresses some meaningful variations in the results and also focuses on the implications of the findings for both theory and psychosocial intervention.

Keywords: collective rituals, emotional synchrony, moral obligation, pandemic, preventive behaviours, social norms

BACKGROUND

One of the major challenges faced by any social group when exposed to a collective threat is the development of a coordinated, cooperative response to it (Cosmides & Tooby, 2013). In the context of COVID‐19 pandemic, it is vital that individuals comply with the norms of prevention, limit the pursuit of their own interests, and eschew free‐riding (Bokemper et al., 2021; Fischer & Karl, 2020). To do this, it is neither sufficient nor feasible for the authorities to regulate citizens’ behaviour through sanctions and policing alone. Rather, what is required is a firm commitment by the population to abide by the new rules in order to ensure long‐term behavioural change (Mols, 2020). In a collective effort to fight the pandemic, numerous researchers and research groups have investigated the potential predictors of a firm adherence to prevention guidelines. In contrast to studies that have focused on the role of intra‐individual variables (e.g. risk perception, disease vulnerability and values), we address the question of what social situations or experiences may be relevant in triggering internal psychosocial processes leading to behavioural change.

In the present study, we focus on two processes that may promote the adoption of preventive behaviours. The first is the phenomenon of participation in shared rituals, specifically collective applause. From February 2020, collective applause became a community ritual in several countries around the world. Although the persistence and duration of the ritual over time varied from one country to another, its form and significance were essentially the same. Clapping was seen as a means of thanking health workers and those providing basic services, as well as a demonstration of cohesion and collective resistance (Booth et al., 2020, March 26; Smith & Gibson, 2020). In Spain, the country in which this study was carried out, the ritual was systematically performed for over 70 days. Every evening, claps could be heard coming from virtually every household in Spain, with large‐scale adherence by the population and lasted until the end of lockdown in June 2020 Spain Plans ‘Thunderous Farewell’ to Nightly Lockdown Balcony Applause, 2020). Both the media and several opinion leaders have explicitly linked the collective applause ritual to a firm commitment to follow the lockdown rules (see Booth et al., 2020, March 26). But do collective rituals really have the power to influence behaviour? And what psychosocial processes explain the impact of rituals? Our study aims to address these questions.

Social influence is the second source of behaviour on which we focus. Previous research has shown that social norms and their perception are powerful predictors of behaviour in many contexts (Cialdini & Goldstein, 2004; Lapinski & Rimal, 2005). Thus, we explore the role of perceived social norms in the behavioural change that took place during the pandemic.

Finally, we introduce the perception of emotional synchrony during the ritual and also the sense of moral obligation as possible mediating variables. By doing this, we aim to explore how the impact of the collective and the social on behaviour is channelled through intra‐individual processes.

Preventive behaviours during a pandemic: the challenge of complying with the guidelines and putting aside individual interests

Preventive behaviour during the COVID‐19 pandemic does not only serve a self‐protection need but it also has a prosocial orientation and represents a form of collective action, since it helps protect the common good and avoid free‐riding (e.g. Bokemper et al., 2021; Gelfand et al., 2021). This tension between individual freedom and collective threat is nothing new and has been at the core of many different issues, including past experiences with voluntary vaccination (Betsch et al., 2013; Giubilini et al., 2018), and it is also vital regarding the current problem at hand: citizens being either willing or reluctant to get the COVID‐19 vaccine (e.g. Böhm, & Betsch, 2021). This highlights the importance of the question of what psychosocial factors prompt people to adopt socially responsible behaviour when faced with a conflict between their individual interests and concern over the common good. Our study aims to explore this, seeking to add to the growing body of knowledge on citizens' preventive actions during the current COVID‐19 pandemic.

Collective rituals

Collective rituals have most likely been part of group functioning since the dawn of humanity and are considered central to coordinated and cooperative performance in large social groups (Durkheim, 1915; Rossano, 2012; Watson‐Jones & Legare, 2016).

Although there is, as yet, no consensus‐based definition of what a ritual actually is (Watson‐Jones & Legare, 2016; Whitehouse & Lanman, 2014), certain universal patterns can be identified. They include the phenomena of synchronized movement, causally opaque action, and arousal (Whitehouse & Lanman, 2014). Collective applause in Spain during lockdown seems to fit this definition, since it was characterized by the movement of clapping, by not having a clear instrumental purpose, by being incomprehensible to those not informed and by constituting an intense emotional experience.

Munn (1973) has defined rituals as a ‘generalised medium of social interaction in which the vehicles for constructing messages are iconic symbols (acts, words, or things) that convert the load of significance or complex sociocultural meanings […] into communicative currency’ (p. 580). In this sense, clapping symbolized feelings of gratitude and support for health workers, and the songs that frequently accompanied the ritual (e.g. ‘Resistiré’ (I will resist) by the Spanish band Duo Dinámico) sought to convey feelings of strength and collective resistance (Booth et al., 2020, March 26; Kirby, 2020, June 6).

Rituals facilitate coordinated and prosocial group activity (Fischer et al., 2014), and through demonstrations of group commitment, foster cooperative behaviour that may even imply individual costs (Watson‐Jones & Legare, 2016; Xygalatas et al., 2013). Shared and coordinated actions create strong emotional bonds between participants, leading to greater emotionality and cooperation (e.g. Wiltermuth & Heath, 2009).

Emotional synchrony

Collective rituals often consist of group mimesis, with everyone involved synchronizing and coordinating their actions by singing, dancing or chanting together (Rossano, 2012). There is evidence that during these synchronized experiences, participants’ emotional and attentional experiences are aligned (e.g. Fischer et al., 2014; Páez et al., 2015; Swann et al., 2012), and this generates the perception of emotional synchrony among them (Páez et al., 2015). The construct of perceived emotional synchrony (Páez et al., 2015) aims to capture the individual experience of what Durkheim (1915) termed emotional effervescence and is conceptualized as a sense of emotional connection, emotional fusion and reciprocal empathy that arises as the result of the reciprocal emotional stimulation and mutual empathy generated during collective gatherings (Páez et al., 2015). Synchrony thus represents a psychological interface, a mediating mechanism that links collective events with individual reactions: a ritual becomes a powerful personal experiences of those who actively take part in it (instead of just being aware of its performance by others) because of its shared nature and the amplifying effect of collective emotions. Therefore, our first hypothesis is formulated as follows:

Hypothesis 1

active participation in the collective applause ritual predicts a more intense perception of emotional synchrony.

Social norms

People abide by social norms for several reasons, one of the most frequent being social adaptation and fitting in (Cialdini & Trost, 1998). In any social context, including a pandemic, individuals are motivated to seek social approval and avoid social sanctions and are therefore attuned to social norms (Cialdini & Goldstein, 2004). Another frequent motive is that people rely on others as a source of information in order to define their social reality and act in an adaptive way (Cialdini & Trost, 1998). Thus, individuals need to know how to behave in times of confusion and uncertainty, such as during the current pandemic. In sum, whatever the reason or combination of motives, social norms guide and constrain behaviour without the force of laws (Cialdini & Trost, 1998).

In the context of COVID‐19, individual health behaviours do not merely embody the individual's choices, instead they acquire collective significance and thus, they become highly moralized (Prosser et al., 2020). Therefore, social factors become especially influential in shaping citizens’ compliance with prevention guidelines. Thus, research has evidenced an important role of different types of social norms, such as collective norms manifested by the prevalence of social distancing or mask wearing in social environment (Barceló & Sheen, 2020), descriptive norms consisting in the belief that most others are engaging in preventive actions (e.g. Reinders Folmer et al., 2021) and also of subjective and injunctive norms expressed by the believe that most important people would approve individual´s preventive actions (e.g. Frounfelker et al., 2021; Raude et al., 2020), on individuals’ adherence to prevention guidelines. Even more, Fischer and Karl (2020) have shown in their meta‐analytic study that the impact of social norms in predicting preventive actions is stronger as compared with the results of previous research within the framework of the theory of planned behaviour.

Social norms are particularly influential when supported by a relevant in‐group (Abrams et al., 1990; Ajzen, 1991; Lapinski & Rimal, 2005), and its influence may be decisive, since norms may vary from one group to another (Cruwys et al., 2020), such as the case of COVID deniers and the citizens who complied with protection guidelines. In this study, we focus on participants’ perceptions of social norms among the people who are important to them. We hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 2

Perceived social norms in the reference group predict self‐reported preventive behaviours.

Collective rituals are a powerful source of positive emotions towards other members of the group or community, which in turn encourages adherence to prosocial norms and the suspension of immediate self‐interest (Rossano, 2012). Emotional synchrony experienced by individuals during collective events has been shown to mediate between participation in rituals and greater social cohesion and integration, as well as higher endorsement of social beliefs and values (Páez et al., 2015). We therefore predict that:

Hypothesis 3

A more intense experience of emotional synchrony predicts a stronger perception of pro‐prevention social norms.

A sense of moral obligation

Among various constructs of morality, a sense of moral obligation seems to represent more purely the motivational route to behaviour. It is defined as ‘a motivational force toward a certain action that later could end in a decision to execute a behaviour’ (Sabucedo et al., 2018, p. 2) and has been theoretically and empirically differentiated from the constructs of personal norms and moral convictions (Sabucedo et al., 2018). A sense of moral obligation may help maintain behaviours that involve personal costs and encourage actions that contribute to collective well‐being. Thus, it plays a crucial role in motivating collective action and certain forms of social participation (Sabucedo et al., 2018; Zlobina et al., 2020). Preventive behaviours may hamper the satisfaction of individual interests, and in this case, a feeling of moral obligation may provide the necessary motivation to engage in them. Therefore, we hold that:

Hypothesis 4

A stronger sense of moral obligation to carry out preventive behaviours predicts greater self‐reported adherence to them.

Previous research has conceived a sense of moral obligation as being determined by intra‐individual characteristics and representing a personal motivation to behave in accordance with a set of moral self‐expectations based on personal values (Sabucedo et al., 2018). In the present study, we argue that the feelings of moral obligation may also crystallize individuals’ social experiences. We speculate that people's experience of emotional synchrony during collective rituals and their perception of social norms will also promote this sense of obligation to engage in preventive behaviours.

In relation to emotional synchrony, we postulate that it shapes individuals’ sense of moral obligation because of the meaning conveyed by the ritual. This prediction is grounded in several theories and studies. First, developmental research has linked moral obligation to feelings of gratitude (Mendonça & Palhares, 2018). As mentioned earlier, the symbolic meaning of the collective applause was to express gratitude towards health workers and those responsible for other basic support services. This suggests that a stronger sense of emotional communion with others participating in the ritual would lead to a stronger sense of moral obligation to engage in preventive behaviours as a means of supporting the efforts of health professionals. Second, in accordance with Kiesler's commitment theory (1971), participation in the collective applause can be interpreted as an indication of greater commitment to the common cause when an individual is, to an extent, bound to the behaviour. We argue that this bounding is experienced through emotional synchrony with others and is reflected in feelings of moral obligation to carry out preventive behaviours.

Hypothesis 5

More intense emotional synchrony predicts a stronger sense of moral obligation.

As regards the role of social norms as a source of moral obligation, we argue that as a part of individuals’ ought (as opposed to actual) self, self‐expectations may be formed in social interactions with relevant people, especially in novel situations, such as the COVID‐19 scenario. In line with Kelman's (1958) theorizing and research on internalization as a result of social influence, we subscribe to the now classic argument that postulates that when social norms are internalized, individual responses become independent from the pressures of the situation (see Abrams, & Levine, 2012; Campbell, 1964; Mols, 2020). Nevertheless, in the present study, we link two narrower and more specific constructs, namely perceived social norms and a sense of moral obligation. We posit that perceived social norms that support preventive measures during the pandemic may become internal behavioural guidelines and be linked to the sense of moral obligation to act accordingly. Previous research has demonstrated that moral obligation mediates the impact of social norms on behaviour (Sia & Jose, 2019). This suggests that moral obligation represents, at least in part, the internalization of certain shared social norms. Therefore:

Hypothesis 6

Perceived social norms predict the sense of moral obligation.

The hypothetical model

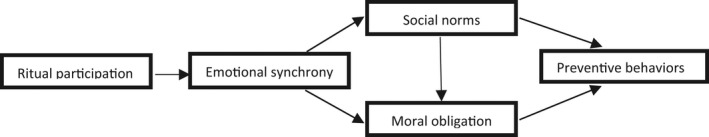

Based on our review of the literature and in light of the hypotheses formulated, we propose a model that links all the variables of the study, namely, participation in the collective applause ritual, emotional synchrony, social norms, moral obligation and self‐reported preventive behaviours. Figure 1 represents our hypothetical model.

FIGURE 1.

Hypothetical model of the predictors of preventive behaviours during the COVID‐19 pandemic

As regards the causality of the proposed relationships between the variables included in the model, previous evidence provides no consistent support for any specific direction. However, we base our model on certain experimental results that suggest that ritual participation is causal factor, at least for the experience of emotional synchrony (see Páez et al., 2015). Similarly, a large body of empirical evidence supports the idea of social norms as predictors of behaviour (Cialdini & Goldstein, 2004; Lapinski & Rimal, 2005).

The present study contributes to the literature in several different ways. Previous studies on the sources of prosocial behaviour have not included collective rituals and emotional synchrony as possible predictors. Moreover, past research on rituals and also on emotional synchrony has mainly analysed cognitive or affective reactions as dependent variables, rarely linking them to behavioural responses (but see Xygalatas et al., 2013). The present study aims to expand existing knowledge on the impact of rituals on self‐reported behaviour and includes variables that may act as mediators in this relationship. As regards social norms, although the existing body of literature is large, most studies tend to link norms directly to behaviour (e.g. Ajzen, 1991, 2011). We, on the other hand, include the motivational construct of a sense of moral obligation as an intermediary between perceived norms and individual actions. We also explore whether experiencing emotional synchrony during collective events increases individuals’ perception of support for the corresponding norms. In sum, in this study, we seek to connect various different processes of social interaction; and we explore the importance of social context for those phenomena that up to now have only been considered from a fundamentally intra‐individual perspective, such as is the case with moral obligation (Sabucedo et al., 2018). Finally, it is important to highlight the potential practical implications of the study, which will be described in the Discussion.

THE PRESENT RESEARCH

In order to test our hypotheses and model, we conducted a correlational, survey‐based online study during the first week of June 2020, just after the end of the lockdown in Spain. The target was the general population. Eight months later, in January 2021, we conducted a second study aimed at testing the persistence of the effects found in the first study. Our intention was to determine, among a more specific population of students, whether similar patterns would be found several months after the ritual was no longer performed, in a context characterized by pandemic‐related restrictions which had been in place for over a year.

Materials and procedure

Participants of the first study were contacted through different social media networks following a snowball sampling technique. In the second study, university students were invited to participate voluntarily. No economic or other rewards were offered. Participants in both studies completed an online questionnaire that contained an informed consent form (which all participants signed).

The measures in both studies were identical, except for the modifications made for preventive behaviours (see below).

Participation in a collective ritual

Participants reported the frequency of their participation in the collective applause ritual at the beginning of lockdown (one item) and during the last month of it (one item) (1 = ‘never or almost never’, 5 = ‘every day’). The items correlated highly (first study, r = .72, p < .001; second study, r = .64, p < .001). We then created a dummy variable in which individuals who did not take part in the ritual at the beginning nor at the end of the lockdown were coded as 0, and the rest were coded as 1.

Emotional synchrony

This variable was measured using three items from the Perceived Emotional Synchrony Scale (Páez et al., 2015). Responses options ranged from 1 (‘not at all’) to 5 (‘very strongly’), and Cronbach's alpha was .93 (first study) and .94 (second study).

Perceived social norms

Two items were used to measure participants’ perception (1 = ‘strongly disagree’, 5 = ‘strongly agree’) that most people important to them engaged in preventive behaviours and expected the participants to do so also (r = .56, p < .001 and r = .53, p < .001).

A sense of moral obligation

Four items from the Moral Obligation Scale (Sabucedo et al., 2018) were included in the questionnaire. Participants rated their sense of obligation to engage in preventive behaviours on a 5‐point Likert‐type scale (1 = ‘strongly disagree’, 5 = ‘strongly agree’) (α = .87 and .84, respectively).

Preventive behaviours

In both studies, we asked about the behaviour performed by the participants in the period when they completed the survey. Participants reported the frequency (1 = ‘never or almost never’, 5 = ‘always or almost always’) with which they engaged in preventive actions. In the first study, five behavioural indicators were used (e.g. wearing a face mask, abiding by restrictions for going out). Cronbach's alpha was .63. The second study employed a slightly modified measure consisting of six items adjusted to the current situation (e.g. ‘I avoid going to public places that are not outdoors or that may not be well ventilated’). Cronbach's alpha was .69.

Analytical strategy

In both studies, we tested the measurement model with a confirmatory factor analysis. Then descriptive analyses and correlations were carried out. Finally, to test our proposed model of interrelations between ritual participation, emotional synchrony, perceived social norms, a sense of moral obligation and self‐reported preventive behaviours, structural equation modelling (SEM) was used, following the maximum likelihood (ML) estimation method. We analysed first the hypothetical model employing the path analysis, and then, we tested the final measurement model in which the paths previously found to be non‐significant were excluded. In all the models, we controlled for age and gender. We did it because previous research has reported mixed evidence of the role of these variables. Thus, while several studies have found that older people and women are more likely to adopt preventive actions (e.g. Barceló & Sheen, 2020; Gualda et al., 2021; Haischer et al., 2020), others have shown that young people as compared with the elderly are engaged in more preventive behaviours (e.g. Kim & Crimmins, 2020) or that there are no significant differences between women and men (e.g. Barceló & Sheen, 2020).

We also tested for direct and indirect effects using bootstrap (500 samples, 95% CI). The IBM SPSS Statistics 22 package and IBM SPSS AMOS 25 were used. Sample size was determined using the G*power analysis for χ2 for the goodness‐of‐fit test (Faul et al., 2007). The minimum sample size was 220 with the following specifications: effect size larger than 0.3, alpha significance criterion of .05 (two‐tailed), standard power criterion of 95%, and five‐degree freedom.

STUDY 1

Method

Participants

Participants were 528 Spanish citizens (69% women) aged between 18 and 83 years (M = 42.85 years, SD = 14.55).

Results

Confirmatory factor analyses of the measures indicated that a model met desired cut‐offs for model fit statistics, with the exception of the chi‐square distribution, which was attributed to sample size (x 2 (71) = 136.693, p < .001, RMSEA = .049, CFI = .972, SRMR = .04). All standardized factor loadings were above the desired cut‐off of .30.

The analyses revealed that 385 study participants (72.9%) had actively taken part in the collective applause ritual. Also, as shown in Table 1, we found that the mean score for emotional synchrony was around the scale midpoint with relatively large standard deviation, while the rest of the means were fairly far above the midpoint. All correlations between the variables were significant and positive.

TABLE 1.

Descriptive statistics and correlations among variables in Study 1 (general population)

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Ritual participation | – | ||||||

| 2. Emotional synchrony | .57*** | – | |||||

| 3. Social norms | .12** | .26*** | – | ||||

| 4. Moral obligation | .19*** | .34*** | .40*** | – | |||

| 5. Preventive behaviours | .17*** | .22*** | .38** | .46*** | – | ||

| 6. Gender | −.09* | −.19*** | −.06 | −.09* | −.08* | – | |

| 7. Age | .22*** | .17*** | .20*** | .16*** | .14** | .00 | – |

| M | – | 3.12 | 4.26 | 4.35 | 4.56 | – | 42.80 |

| SD | – | 1.20 | .77 | .81 | .53 | – | 14.61 |

***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05.

The results of the path analysis for the hypothetical model showed that the model provided an excellent fit (see Table 2) and also revealed that all the proposed paths were significant. In order to test the possibility that the participation in collective applause was motivated by norms and sense of moral obligation, we tested the reverse causal model direction where the paths went from norms and obligation to ritual participation (and also to self‐reported behaviours) and from ritual and emotional synchrony directly to preventive actions. This model showed poor fit (CMIN/DF = 25.96, RMSEA = .22, NFI = .91, TLI = .12, CFI = .90). We also performed a model where, apart from the relationships proposed in the hypothetical model, we added the paths from norms and obligation to ritual participation. This model had good fit (CMIN/DF = 1.69, RMSEA = .04, NFI = .99, TLI = .98, CFI = .99) but the introduced paths from social norms and sense of moral obligation to ritual participation were not significant, while all the interrelations proposed in the hypothetical model remained significant. Therefore, we concluded that the model developed in this study was the most adequate.

TABLE 2.

Fit indexes of the models in Study 1 (general population)

| χ2 (df) | p | CMIN/DF | RMSEA | NFI | TLI | CFI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothetical model: path analysis | 5.484 (4) | .24 | 1.37 | .03 | .99 | .99 | .99 |

| Measurement model | 203.19 (105) | .00 | 1.93 | .04 | .94 | .96 | .97 |

Due to the sensitivity of chi‐square statistic to sample size (its value should be nonsignificant at p < .05 in order to indicate that the models fits the data well), other absolute fit indexes were employed. CMIN/DF, values lower than 2 indicate a good fit; RMSEA, values should be lower than .08 to indicate a good fit; NFI, TLI and CFI, values upper to .90 indicate that model has a good fit (Bagozzi & Yi, 1988).

We then tested the measurement model based on the hypothetical model and found that it achieved good fit (see Table 2). Using G*Power (Faul et al., 2007), a post hoc power analyses were conducted for each part of the model. In each case, after R 2 values were entered to calculate the effect size, statistical power was shown to be >.99 with an α level of .05.

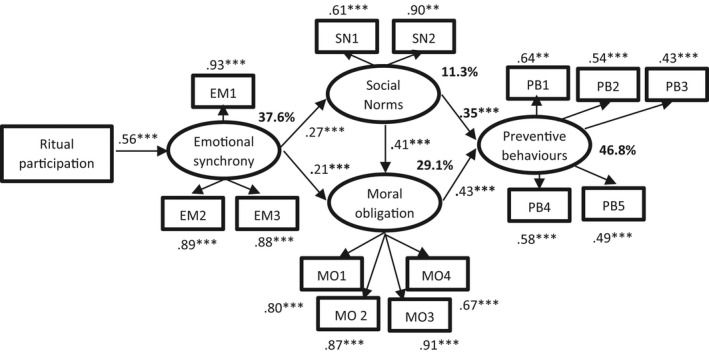

As can be observed in Figure 2, in this final model, all the proposed relationships were significant, and all loadings of manifest variables on the theoretically associated latent variables were high.

FIGURE 2.

Predictors of preventive behaviours in Study 1 (general population). Standardised estimations for the measurement model. ***p < .001. Control variables (age and gender) included in the analysis but not visible in the figure

Finally, as Table 3 shows, all direct and indirect effects were significant.

TABLE 3.

Direct, indirect and total effects of final model in Study 1 (general population)

| Predictor variable | Outcome variable | Direct effect [95% CIs] | Indirect effect [95% CIs] | Total effect [95% CIs] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ritual participation | Synchrony | .56** | – | .56** |

| Norms | – | .15** | .15** | |

| Obligation | – | .18** | .18** | |

| Behaviours | – | .13** | .13** | |

| Emotional synchrony | Norms | .27** | – | .27** |

| Obligation | .21** | .11** | .33** | |

| Behaviours | – | .24** | .24** | |

| Social norms | Obligation | .41** | – | .41** |

| Behaviours | .35** | .18** | .53** | |

| Moral obligation | Behaviours | .43** | – | .43** |

**p < .01.

Discussion

The results of Study 1 supported our predictions. Thus, we found that active participation in the collective applause ritual predicted greater perceived emotional synchrony (Hypothesis 1 supported) and that synchrony predicted perceived social norms (Hypothesis 3 confirmed) and feelings of moral obligation (Hypothesis 5 proved). Also, a significant path was observed from social norms to reported preventive behaviours (Hypothesis 2 supported) and to moral obligation (Hypothesis 6 supported). Finally, a sense of moral obligation was confirmed to be a significant predictor of adherence to prevention guidelines (Hypothesis 4 proved).

The exploration of indirect effects provided evidence of a significant indirect impact of participation in the collective applause ritual on perceived social norms, a sense of moral obligation, and self‐reported preventive behaviours. We also found that, in addition to having a direct impact on feelings of moral obligation, perceived emotional synchrony influenced this variable indirectly via social norms. Emotional synchrony also had a significant indirect effect on behaviours. Social norms had a significant indirect effect on self‐reported maintenance of preventive actions via moral obligation, as well as a direct effect.

In sum, we can state that Study 1 provided solid evidence of both direct and indirect roles of collective and social influence processes on self‐reported preventive behaviours during the lockdown in Spain and also showed that perceived emotional synchrony and sense of moral obligation were important intraindividual mediators in this relationship.

STUDY 2

As mentioned earlier, Study 2 aimed to test the model obtained in Study 1 during a different period of the COVID‐19 pandemic. We reasoned that the effects of participating in the ritual may be dependent on the specific moment and socio‐political context of the COVID‐19 crisis. Study 1 was carried out at the end of the lockdown period in Spain, characterized by acute collective trauma and at the same time, feelings of hope for future definite improvement in the situation. However, the motivating effect of collective applause on prosocial action may be diluted or even reversed over time. Study 2 was conducted almost a year after the beginning of the collective applause, when no substantial progress had been achieved in eliminating the threat (which implied the maintenance of the restrictions and the continued need for preventive behaviours). The aim was to analyse whether the effects of participating in the ritual were still present among Spanish citizens. This time we focused on university students, among other reasons because it was a convenient sample, and also because this segment of population has been identified as being most at risk of contagion.

Method

Participants

Participants were 291 university students (78% women) aged between 18 and 30 years (M = 21.13 years, SD = 2.45).

Results

As in Study 1, confirmatory factor analyses of the measures indicated that the model fitted the data well except for the chi‐square distribution, attributable to sample size (χ2 (71) = 103,456, p < .01, RMSEA = .048, SRMR = .05, CFI = .96), and all standardized factor loadings were above the cut‐off of .30.

We found that 202 study participants (69.4%) reported that they had actively taken part in the collective applause ritual. Descriptives and bivariate correlations are displayed in Table 4. In comparison with Study 1, the participants of this study reported a similar intensity of experienced emotional synchrony during collective applause (p = .113), while the scores on the perceived social norms, on the sense of moral obligation, and on self‐reported preventive behaviours were all significantly lower (p < .05). Also, and unlike in Study 1, the participation in the ritual and perceived emotional synchrony did not show significant correlations with social norms and preventive behaviours.

TABLE 4.

Descriptive statistics and correlations among variables in Study 2 (students)

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Ritual participation | – | ||||||

| 2. Emotional synchrony | .61*** | – | |||||

| 3. Social norms | .07 | .01 | – | ||||

| 4. Moral obligation | .17** | .25*** | .42*** | – | |||

| 5. Preventive behaviours | −.00 | .03 | .47*** | .54*** | – | ||

| 6. Gender | −.03 | −.21*** | −.02 | −.16** | −.00 | – | |

| 7. Age | −.09 | −.12* | .03 | −.09 | .13* | .21*** | – |

| M | – | 3.10 | 4.15 | 4.11 | 3.99 | – | 21.13 |

| SD | – | 1.21 | .70 | .84 | .64 | – | 2.44 |

*** p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05.

We next conducted path analysis to test the fit of the data for the hypothetical model proposed in this research. The model had good fit indexes (see Table 5) and most paths were significant, except for the path from emotional synchrony to perceived social norms. Therefore, we dropped this path from the final (measurement) model in this study. Also, as in Study 1, we conducted a path analysis in which, apart from the relationships proposed in the hypothetical model, we added the paths from norms and obligation to ritual participation. This model had good fit (CMIN/DF = 2.06, RMSEA = .06, NFI = .99, TLI = .99, CFI = .99) but once again, the paths added from social norms and sense of moral obligation to ritual participation were not significant, while all the interrelations proposed in the hypothetical model remained significant except for the path from synchrony to norms.

TABLE 5.

Fit indexes of the models in Study 2 (students)

| χ2 (df) | p | CMIN/DF | RMSEA | NFI | TLI | CFI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothetical model: path analysis | 6.36 (4) | .17 | 1.59 | .05 | .99 | .97 | .99 |

| Final model: measurement model | 226.62 (122) | .00 | 1.85 | .05 | .88 | .93 | .94 |

Due to the sensitivity of chi‐square statistic to sample size (its value should be nonsignificant at p < .05 in order to indicate that the models fits the data well), other absolute fit indexes were employed. CMIN/DF: values lower than 2 indicate a good fit; RMSEA: values should be lower than .08 to indicate a good fit; NFI, TLI and CFI: values upper to .90 indicate that model has a good fit (Bagozzi & Yi, 1988).

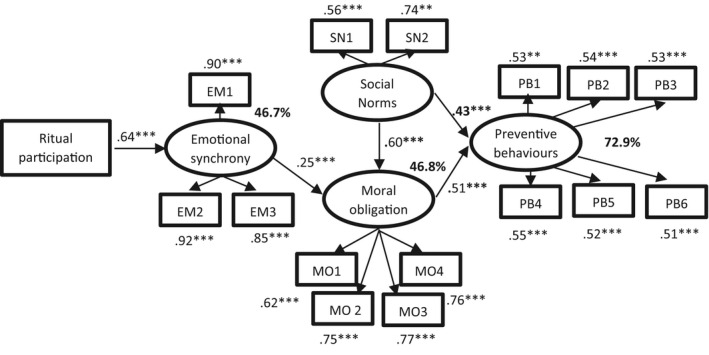

We then performed an analysis of the measurement model. As can be observed in Table 5, it showed acceptable fit. Post hoc power analyses using G*Power revealed that in each case, after R 2 values were entered to calculate the effect size, statistical power was >.99 with an α level of .05. Figure 3 shows the resulting model where all the proposed relationships were significant.

FIGURE 3.

Predictors of preventive behaviours in Study 2 (students). Standardised estimations for the measurement model. *** p < .001. Control variables (age and gender) included in the analysis but not visible in the figure. Non‐significant paths are not shown

Finally, as can be observed in Table 6, the test for direct and indirect effects evidenced that all effects were significant.

TABLE 6.

Direct, indirect and total effects of final model in Study 2 (students)

| Predictor variable | Outcome variable | Direct effect [95% CIs] | Indirect effect [95% CIs] | Total effect [95% CIs] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ritual participation | Synchrony | .64** | – | .64** |

| Obligation | – | .16** | .16** | |

| Behaviours | – | .08** | .08** | |

| Emotional synchrony | Obligation | .25** | – | .25** |

| Behaviours | – | .13** | .13** | |

| Social norms | Obligation | .60** | – | .60** |

| Behaviours | .43** | .31** | .74** | |

| Moral obligation | Behaviours | .51** | – | .51** |

**p < .01.

Discussion

Study 2 generally supported the hypothetical model developed in this research. It evidenced that the impact of participating in collective applause ritual was alive eight months after. Thus, we found that emotional synchrony felt when the ritual was performed acted as significant predictor of individuals’ current sense of moral obligation to keep preventive behaviours and that active participation in collective applause continued to exert significant indirect effect on both moral obligation and current self‐reported behaviour more than half a year later. At the same time, this study revealed that taking part in the ritual and the intensity of emotional synchrony were not significantly related to social norms. Although Study 2 was conducted with a different sample, this result seems to realistically reflect the dynamic nature of social perception, as we shall discuss in greater detail below.

GENERAL DISCUSSION

The general approach guiding this research falls within the framework of the study of collective and social influence processes and their impact on individual responses.

The main propositions reflected in our hypothetical model were generally confirmed in both studies. The models achieved good fit, all loadings of manifest variables on the corresponding latent variables were high, and the variance explained for the dependent measures was important, especially in the case of preventive behaviours in Study 2 (72.9%). Comparing the scores in both studies, we observed that the percentage of people who reported having participated in the collective applause ritual was almost identical and also that their intensity of emotional synchrony was similar. This suggests that the samples can be considered comparable in terms of their experience of ritual participation and ensures the validity of the research from this point of view. On the other hand, we found that levels of reported behavioural adherence to disease‐related measures, perceived social norms and feelings of moral obligation to maintain preventive behaviours were lower in Study 2 (student sample) compared to Study 1 (general population). This may be due to socio‐demographic differences between the samples. Nonetheless, this pattern resembles the findings of some longitudinal studies that have evidenced a gradual reduction in adherence to protective behaviours over time, especially regarding physical distancing (e.g. Petherick et al., 2021) and also a decline in perceived social norms and moral obligation (Reinders Folmer et al., 2021). In light of this, we can assume that the differences in mean scores realistically reflect the temporal dynamics of reactions to the pandemic. We discuss the consistent patterns established and also the paths that were not confirmed or that varied across the studies.

Firstly, as regards the role of collective rituals, we found that rituals indirectly yet significantly foster preventive behaviour through various cognitive‐affective processes. The inclusion in our study of the variable of emotional synchrony (Páez et al., 2015) helped identify one of the possible mechanisms through which collective processes may mould individual reactions. As we predicted, those Spanish citizens who actively took part in the collective applause ritual experienced more intense feelings of emotional synchrony; in turn, synchrony indirectly predicted self‐reported behavioural adherence to prevention guidelines. This relationship between group events and individual responses was mediated by participants’ perception of the social reality (social norms), as well as by motivational processes (sense of moral obligation).

With respect to the path from social influence to preventive actions, our results reliably confirmed that the social norms perceived in participants’ referent groups predicted their current self‐reported behaviour. This finding is consistent with general research on the relationship between social norms and behaviour (e.g. Cialdini & Goldstein, 2004; Lapinski & Rimal, 2005) and also with other studies conducted in the context of the COVID‐19 pandemic (e.g. Fischer & Karl, 2020; Frounfelker et al., 2021; Goldberg et al., 2020; Raude et al., 2020; Reinders Folmer et al., 2021). Furthermore, we found that the impact of social norms on behaviour was stronger in Study 2. This result is similar to that described by Raude et al. (2020), who found evidence of the increasingly important role played by social norms during the course of the pandemic.

In Study 1, we also showed that emotional synchrony was a significant predictor of perceived social norms and that participation in the ritual influenced norms perception indirectly through emotional synchrony. This suggests that experiencing greater emotional communion with others present at the ritual magnified the belief that more persons important to an individual endorsed preventive behaviour. This relationship between synchrony and the perception of social norms may reflect the subjective origin of this perception, possibly rooted in social projection (Lapinski & Rimal, 2005). In contrast, in Study 2, the relationship between synchrony and social norms was not significant. This vanishing of the effect of past emotional experience on current social perception seems to realistically reflect the dynamic nature of social influence: when the experience of participating in the ritual was recent, feeling emotional communion with others enhanced the perception that significant others supported prevention norms, whereas several months later, this effect was no longer present. This finding also highlights the fact that the impact of rituals is temporary for some phenomena, such as social norms, but, as we shall see below, it may be more lasting for other variables, such as sense of moral obligation.

The inclusion of feelings of moral obligation to comply with health authorities’ guidance added a motivational dimension of required behavioural change. Indeed, our results confirmed that in both studies a sense of moral obligation predicted self‐reported behavioural engagement with prevention measures. Likewise, while this manuscript was being drafted, a similar finding was published linking obligation to mask wearing and staying home during the pandemic in China (Yang & Ren, 2020). This serves to strengthen our conclusion regarding the importance of sense of moral obligation as a motivational source of socially responsible actions that likely imply individual costs. This finding also highlights the fact that preventive behaviours have a prosocial and moral quality and do not exclusively pursue a self‐protection goal (Bokemper et al., 2021; Bonell et al., 2020; Fischer & Karl, 2020; Gelfand et al., 2021).

We also provided evidence supporting the idea that sense of moral obligation has social roots: in both studies, obligation was predicted by emotional synchrony felt during ritual participation and by perceived social norms. In light of this, we can draw several possible conclusions. First, our analyses suggest that the experience of emotional synchrony with others in the community felt during a collective ritual is internalized in the form of intrinsic obligation. This pattern, consistently found in both studies, seems to uncover one of the psychosocial mechanisms linking the collective and the individual. It is worth noting that, unlike with social norms, not only was the effect of the synchrony felt during collective applause on feelings of moral obligation significant when the memory of ritual participation was fresh but was also present eight months later. We can conclude that powerful emotional experiences felt during community‐based gatherings represent a possibly understudied source of internal prosocial motivation. To the best of our knowledge, no previous research has yet explored this issue; therefore, we believe that our study makes a relevant contribution in this sense.

Second, the identification of perceived social norms as an important predictor of the feelings of moral obligation may help operationalize in a more specific way the theoretical process by which social norms are internalized (e.g. Abrams, & Levine, 2012; Campbell, 1964; Kelman, 1958; Mols, 2020). The sense of moral obligation has been conceptualized as an individual´s feeling of ‘what ought be done’, based on personal values (Vilas & Sabucedo, 2012, p. 371); our results suggest that this also reflects the internalization of social norms regarding what is ‘the right thing to do’ (Mols, 2020, p. 39). Said internalization may be modulated by the degree of congruence between the content of group norms and the individual´s own values or moral convictions. Thus, according to Kelman (1958), internalization occurs when behavioural change is intrinsically rewarding because it matches one´s personal principles. Future research may delve into this issue.

Implications and applications

In modern societies, there are normative and practical limits to repressive interventions, since these may clash with democratic rights (Jørgensen et al., 2020). Moreover, the efficacy and ethics of the use of ‘nudge tactics’ are also questionable (e.g. Mols, 2020). It is therefore crucial to identify the psychosocial mechanisms that may promote behavioural change and encourage compliance with socially‐responsible behaviours in the contexts of collective threat, including the current and also future pandemics (Del Rio & Guarner, 2010; Zhang et al., 2019).

One of the contributions made by this study is that it provides empirical evidence that the collective applause ritual, viewed as a community effort to combat adversity, triggered directly and indirectly affective and cognitive responses which served to foster self‐reported preventive behaviours. In addition to this theoretical input, having conducted the research in the context of the COVID‐19 pandemic lends the findings a significant applied value. Although past experience has shown that collective rituals are not always benign for others (Nazi rituals are perhaps the most salient example of this), the idea that initiating or promoting collective rituals may help encourage desired behaviours in times of social emergency is nevertheless a useful one.

One possible caveat to this proposal may be that the collective applause ritual analysed in this study arose in a fairly natural and powerful way, spilling over national borders and resonating with the experiences of individuals in many different countries (Booth et al., 2020, March 26). The question is, would a more ‘artificial’ introduction of a ritual designed by socio‐political stakeholders have the same effect as that observed in our study? Or would the impact of the ritual be supressed if participation or the ritual itself were not valued by the community? (Rossano, 2012). Another consideration concerns the effectiveness of a ritual when it becomes or is perceived to be a mere virtue‐signalling, especially if the ritual is related to an issue which is highly moralized, as is the case of COVID‐related responses (Prosser et al., 2020). Further research is needed to answer these questions. Nevertheless, a meta‐analysis of experimental studies on the physical synchrony induced among participants has confirmed its stable positive effect on prosocial behaviour and social bonding (Mogan et al., 2017). Since synchronization is a key characteristic of collective rituals (Whitehouse & Lanman, 2014), this finding seems to lend support to the idea of the effectiveness of interventions based on collective rituals. Moreover, it allows us to believe that the trends found in our study can be extrapolated to other situations and contexts.

As regards the role of social norms and sense of moral obligation as factors that promote compliance with desired behaviours, our results lend further support to the interventions strategies proposed in other studies. First, in line with what has been suggested by other researchers (e.g. Van Bavel et al., 2020; Bonell et al., 2020), including information about social norms in persuasion campaigns may be more effective than, for example, using authoritarian messages or those based on fear or disgust. Second, social norms interventions communicating about collective change in behaviour among important others have been shown to play a central role for shifting norms that strengthen behavioural adherence (e.g. Bokemper et al., 2021; Sparkman & Walton, 2019). Third, framing the behavioural adherence to certain norms as a question of moral obligation may increase people's motivation to continue engaging in these actions despite the costs involved (Everett et al., 2020).

Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be mentioned. In relation to the study design, its correlational and cross‐sectional nature precludes any definite conclusion regarding causal relationships between the variables. Despite this, however, as we state in the Introduction, there is certain empirical evidence that supports a causal direction from participation in rituals to cognitive and affective reactions (Páez et al., 2015; Rossano, 2012). There is also a robust line of research that establishes causality from social norms to behaviour (Cialdini & Goldstein, 2004; Lapinski & Rimal, 2005). At the same time, it is important to acknowledge that although we constructed our model in one causal direction, the relationships among the variables may be more complex or involve other variables not contemplated in the study.

Relatedly, we acknowledge that the two studies methodologically differed in terms of temporal closeness to the collective applause ritual. Thus, the first study was conducted immediately after the end of the ritual which was carried out daily for over two months. Therefore, the experience of participation was fresh, and the measures of taking part in the ritual, feelings of emotional synchrony, self‐reported preventive behaviours, perception of social norms and sense of moral obligation alluded to the same time period. On the other hand, in the second study which was carried out eight months later, the measures referred to collective applause participation and emotional synchrony alluded to the past while the rest of the variables focused on current experience and behaviour.

Another limitation of the correlational method used is that it does not clarify the significance attached to the behaviours analysed in the study. A qualitative approach would enable an in‐depth exploration of how, at a subjective level, the collective expression of feelings of debt and gratitude are internalized as guidelines for preventive behaviours.

Moreover, the snowball sampling technique is associated with possible biases (Atkinson & Flint, 2001), and this may limit the generalization of our conclusions. Nevertheless, we believe that the sample size and the wide range of the variance of sociodemographic characteristics may compensate for the limitations of the sampling method.

Finally, the effects of the participation in collective ritual and of social norms evidenced in our study may be different in other social contexts. For instance, they may be moderated by cultural values such as collectivism and cultural tightness that strengthen normative effects on behaviour (Fischer & Karl, 2020; Gelfand et al., 2021), or by population or community‐level degree of the endorsement of desired activities (Fischer & Karl, 2020).

All in all, social psychologists need to produce as much useful evidence and research as possible to design working recommendations to effectively respond to societal threats. The challenges posed by COVID‐19 may be similar to other future pandemics and also to climate emergency that the global community is facing right now in that it requires individuals to put aside their self‐interests and behave in socially responsible ways in order to protect the common good. Similarly, strict adherence to recommended social norms is a key mechanism in dealing with collective threats because a tremendous amount of coordination is required (Gelfand et al., 2021). The present study sought to advance existing knowledge of collective and social influence processes as potential triggers of individual prosocial reactions. Future research and intervention may design actions focused on enhancing corresponding social norms and also on organizing collective rituals related to a shared purpose (e.g. protecting the Earth). As several authors have argued (Van Bavel et al., 2020; Drury et al., 2020; Mols, 2020), stressing the social over the individual appears to be the best option, and ‘nurturing the social in peoples’ minds is not the problem but it is the solution’ (Yzerbyt, 2020, p. xiv).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None of the authors have any conflict of interest to declare.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Anna Zlobina: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing. María Celeste Dávila: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Zlobina, A. , & Dávila, M. C. (2022). Preventive behaviours during the pandemic: The role of collective rituals, emotional synchrony, social norms and moral obligation. British Journal of Social Psychology, 61, 1332–1350. 10.1111/bjso.12539

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Zenodo.org at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4244608, reference number md5:9a772bfc6855c78a2953216c4bbf4f09.

REFERENCES

- Abrams, D. , & Levine, J. M. (2012). The formation of social norms: Revisiting Sherif’s autokinetic illusion study. Social Psychology: Revisiting the Classic Studies, 57–75. [Google Scholar]

- Abrams, D. , Wetherell, M. , Cochrane, S. , Hogg, M. A. , & Turner, J. C. (1990). Knowing what to think by knowing who you are: Self‐categorization and the nature of norm formation, conformity and group polarization. British Journal of Social Psychology, 29(2), 97–119. 10.1111/j.2044-8309.1990.tb00892.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. (2011). The theory of planned behaviour: Reactions and reflections. Psychology & Health, 26(9), 1113–1127. 10.1080/08870446.2011.613995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, R. , & Flint, J. (2001). Accessing hidden and hard‐to‐reach populations: Snowball research strategies. Social Research Update, 33(1), 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R. P. , & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16(1), 74–94. 10.1007/BF02723327 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barceló, J. , & Sheen, G. C. H. (2020). Voluntary adoption of social welfare‐enhancing behavior: Mask‐wearing in Spain during the COVID‐19 outbreak. PLoS One, 15(12), e0242764. 10.1371/journal.pone.0242764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bavel, J. J. V. , Baicker, K. , Boggio, P. S. , Capraro, V. , Cichocka, A. , Cikara, M. , Crockett, M. J. , Crum, A. J. , Douglas, K. M. , Druckman, J. N. , Drury, J. , Dube, O. , Ellemers, N. , Finkel, E. J. , Fowler, J. H. , Gelfand, M. , Han, S. , Haslam, S. A. , Jetten, J. , … Willer, R. (2020). Using social and behavioural science to support COVID‐19 pandemic response. Nature Human Behaviour, 4(5), 460–471. 10.1038/s41562-020-0884-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betsch, C. , Böhm, R. , & Korn, L. (2013). Inviting free‐riders or appealing to prosocial behavior? Game‐theoretical reflections on communicating herd immunity in vaccine advocacy. Health Psychology, 32(9), 978–985. 10.1037/a0031590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böhm, R. , & Betsch, C. (2021). Prosocial vaccination. Current Opinion in Psychology, 43, 307–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bokemper, S. E. , Cucciniello, M. , Rotesi, T. , Pin, P. , Malik, A. A. , Willebrand, K. , Paintsil, E. E. , Omer, S. B. , Huber, G. A. , & Melegaro, A. (2021). Experimental evidence that changing beliefs about mask efficacy and social norms increase mask wearing for COVID‐19 risk reduction: Results from the United States and Italy. PLoS One, 16(10), e0258282. 10.1371/journal.pone.0258282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonell, C. , Michie, S. , Reicher, S. , West, R. , Bear, L. , Yardley, L. , Curtis, V. , Amlôt, R. , & Rubin, G. J. (2020). Harnessing behavioural science in public health campaigns to maintain ‘social distancing’in response to the COVID‐19 pandemic: Key principles. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 74(8): 617–619. 10.1136/jech-2020-214290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth, W. , Adam, K. , & Rolfe, P. (2020, March 26). In fight against coronavirus, the world gives medical heroes a standing ovation. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/europe/clap‐for‐carers/2020/03/26/3d05eb9c‐6f66‐11ea‐a156‐0048b62cdb51_story.html

- Campbell, E. Q. (1964). The internalization of moral norms. Sociometry, 391–412. 10.2307/2785655 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini, R. B. , & Goldstein, N. J. (2004). Social influence: Compliance and conformity. Annual Review of Psychology, 55(1), 591–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini, R. B. , & Trost, M. R. (1998). Social influence: Social norms, conformity, and compliance. In Gilbert D. T., Fiske S. T., & Lindzey G. (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (4th ed., pp. 151–192). McGraw‐Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Cosmides, L. , & Tooby, J. (2013). Evolutionary psychology: New perspectives on cognition and motivation. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 201–229. 10.1146/annurev.psych.121208.131628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruwys, T. , Stevens, M. , & Greenaway, K. H. (2020). A social identity perspective on COVID‐19: Health risk is affected by shared group membership. British Journal of Social Psychology, 59, 584–593. 10.1111/bjso.12391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Rio, C. , & Guarner, J. (2010). The 2009 influenza A (H1N1) pandemic: What have we learned in the past 6 months. Transactions of the American Clinical and Climatological Association, 121, 128–137. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drury, J. , Reicher, S. , & Stott, C. (2020). COVID‐19 in context: Why do people die in emergencies? It’s probably not because of collective psychology. British Journal of Social Psychology, 59(3), 686–693. 10.1111/bjso.12393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim, E. (1915). The elementary forms of religious life. The Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Everett, J. A. C. , Colombatto, C. , Chituc, V. , Brady, W. J. , & Crockett, M. (2020). The effectiveness of moral messages on public health behavioral intentions during the COVID‐19 pandemic. PsyArXiv. 10.31234/osf.io/9yqs8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Faul, F. , Erdfelder, E. , Lang, A.‐G. , & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 175–191. 10.3758/BF03193146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, R. , & Karl, J. A. (2020). Predicting behavioral intentions to prevent or mitigate COVID‐19: A cross‐cultural meta‐analysis of attitudes, norms, and perceived behavioral control effects. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 13(1), 264–276. 10.1177/19485506211019844 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, R. , Xygalatas, D. , Mitkidis, P. , Reddish, P. , Tok, P. , Konvalinka, I. , & Bulbulia, J. (2014). The fire‐walker’s high: Affect and physiological responses in an extreme collective ritual. PLoS One, 9, e88355. 10.1371/journal.pone.0088355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frounfelker, R. L. , Santavicca, T. , Li, Z. Y. , Miconi, D. , Venkatesh, V. , & Rousseau, C. (2021). COVID‐19 experiences and social distancing: Insights from the theory of planned behavior. American Journal of Health Promotion, 35(8), 1095–1104. 10.1177/08901171211020997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand, M. J. , Jackson, J. C. , Pan, X. , Nau, D. , Pieper, D. , Denison, E. , Dagher, M. , Van Lange, P. A. M. , Chiu, C.‐Y. , & Wang, M. O. (2021). The relationship between cultural tightness–looseness and COVID‐19 cases and deaths: a global analysis. The Lancet Planetary Health, 5(3), e135–e144. 10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30301-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giubilini, A. , Douglas, T. , & Savulescu, J. (2018). The moral obligation to be vaccinated: Utilitarianism, contractualism, and collective easy rescue. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, 21(4), 547–560. 10.1007/s11019-018-9829-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, M. , Gustafson, A. , Maibach, E. , van der Linden, S. , Ballew, M. T. , Bergquist, P. , Kotcher, J. , Marlon, J. R. , Rosenthal, S. A. , & Leiserowitz, A. (2020). Social norms motivate COVID‐19 preventive behaviors. PsyArXiv. 10.31234/osf.io/9whp4 [Preprint] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gualda, E. , Krouwel, A. , Palacios‐Gálvez, M. , Morales‐Marente, E. , Rodríguez‐Pascual, I. , & García‐Navarro, E. B. (2021). Social distancing and COVID‐19: Factors associated with compliance with social distancing norms in Spain. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 727225. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.727225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haischer, M. H. , Beilfuss, R. , Hart, M. R. , Opielinski, L. , Wrucke, D. , Zirgaitis, G. , Uhrich, T. D. , & Hunter, S. K. (2020). Who is wearing a mask? Gender‐, age‐, and location‐related differences during the COVID‐19 pandemic. PLoS One, 15(10), e0240785. 10.1371/journal.pone.0240785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen, F. J. , Bor, A. , & Petersen, M. B. (2020). Compliance without fear: Predictors of protective behavior during the first wave of the COVID‐19 pandemic. PsyArXiv. 10.31234/osf.io/uzwgf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelman, H. C. (1958). Compliance, identification, and internalization three processes of attitude change. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 2(1), 51–60. 10.1177/002200275800200106 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kiesler, C. A. (1971). The psychology of commitment. Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J. K. , & Crimmins, E. M. (2020). How does age affect personal and social reactions to COVID‐19: Results from the national Understanding America Study. PloS Oone, 15(11), e0241950. 10.1371/journal.pone.0241950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby, W. (2020, June 6). Sound of Lockdown: Spain sings in solidarity. Varsity. https://www.varsity.co.uk/music/19396 [Google Scholar]

- Lapinski, M. K. , & Rimal, R. N. (2005). An explication of social norms. Communication Theory, 15(2), 127–147. 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2005.tb00329.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mendonça, S. E. , & Palhares, F. (2018). Gratitude and moral obligation. In Tudge J. R. H., & Freitas L. B. L. (Eds.), Developing gratitude in children and adolescents (pp. 89–110). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mogan, R. , Fischer, R. , & Bulbulia, J. A. (2017). To be in synchrony or not? A meta‐analysis of synchrony's effects on behavior, perception, cognition and affect. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 72, 13–20. 10.1016/j.jesp.2017.03.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mols, F. (2020). Behaviour change. In Jetten J., Reicher S. D., Haslam S. A., & Cruwys T. (Eds.), Together apart: The psychology of COVID‐19 (pp. 36–40). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Munn, N. (1973). Symbolism in a ritual context: Aspects of symbolic action. In Honigmann J. (Ed.), Handbook of social and cultural anthropology (pp. 579–612). Rand McNally. [Google Scholar]

- Páez, D. , Rimé, B. , Basabe, N. , Wlodarczyk, A. , & Zumeta, L. (2015). Psychosocial effects of perceived emotional synchrony in collective gatherings. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 108(5), 711–729. 10.1037/pspi0000014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petherick, A. , Goldszmidt, R. , Andrade, E. B. , Furst, R. , Hale, T. , Pott, A. , & Wood, A. (2021). A worldwide assessment of changes in adherence to COVID‐19 protective behaviours and hypothesized pandemic fatigue. Nature Human Behaviour, 5(9), 1145–1160. 10.1038/s41562-021-01181-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prosser, A. M. , Judge, M. , Bolderdijk, J. W. , Blackwood, L. , & Kurz, T. (2020). ‘Distancers’ and ‘non‐distancers’? The potential social psychological impact of moralizing COVID‐19 mitigating practices on sustained behaviour change. British Journal of Social Psychology, 59(3), 653–662. 10.1111/bjso.12399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raude, J. , Lecrique, J. M. , Lasbeur, L. , Leon, C. , Guignard, R. , Roscoät, E. D. , & Arwidson, P. (2020). Determinants of preventive behaviors in response to the COVID‐19 pandemic in France: Comparing the sociocultural, psychosocial and social cognitive explanations. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 3345. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.584500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinders Folmer, C. P. , Brownlee, M. A. , Fine, A. D. , Kooistra, E. B. , Kuiper, M. E. , Olthuis, E. H. , de Bruijn, A. L. , & van Rooij, B. (2021). Social distancing in America: Understanding long‐term adherence to COVID‐19 mitigation recommendations. PLoS One, 16(9), e0257945. 10.1371/journal.pone.0257945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossano, M. J. (2012). The essential role of ritual in the transmission and reinforcement of social norms. Psychological Bulletin, 138(3), 529–549. 10.1037/a0027038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabucedo, J. M. , Dono, M. , Alzate, M. , & Seoane, G. (2018). The importance of protesters’ morals: Moral obligation as a key variable to understand collective action. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 418. 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sia, S. K. , & Jose, A. (2019). Attitude and subjective norm as personal moral obligation mediated predictors of intention to build eco‐friendly house. Management of Environmental Quality: An International Journal, 30(2), 678–694. 10.1108/MEQ-02-2019-0038 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L. G. , & Gibson, S. (2020). Social psychological theory and research on the novel coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) pandemic: Introduction to the rapid response special section. The British Journal of Social Psychology, 59(3), 571–583. 10.1111/bjso.12402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spain plans ‘thunderous farewell’ to nightly lockdown balcony applause . (2020, May 15). The Local. https://www.thelocal.es/20200515/spain‐plans‐thunderous‐farewell‐to‐nightly‐lockdown‐balcony‐applause [Google Scholar]

- Sparkman, G. , & Walton, G. M. (2019). Witnessing change: Dynamic norms help resolve diverse barriers to personal change. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 82, 238–252. 10.1016/j.jesp.2019.01.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Swann, W. B. Jr , Jetten, J. , Gomez, A. , Whitehouse, H. , & Bastian, B. (2012). When group membership gets personal: A theory of identity fusion. Psychological Review, 119, 441–456. 10.1037/a0028589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilas, X. , & Sabucedo, J. M. (2012). Moral obligation: A forgotten dimension in the analysis of collective action. Revista De Psicología Social, 27(3), 369–375. 10.1174/021347412802845577 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watson‐Jones, R. E. , & Legare, C. H. (2016). The social functions of group rituals. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 25(1), 42–46. 10.1177/0963721415618486 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehouse, H. , & Lanman, J. A. (2014). The ties that bind us. Current Anthropology, 55, 674–695. 10.1086/678698 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wiltermuth, S. S. , & Heath, C. (2009). Synchrony and cooperation. Psychological Science, 20(1), 1–5. 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02253.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xygalatas, D. , Mitkidis, P. , Fischer, R. , Reddish, P. , Skewes, J. , Geertz, A. W. , Roepstorff, A. , & Bulbulia, J. (2013). Extreme rituals promote prosociality. Psychological Science, 24(8), 1602–1605. 10.1177/0956797612472910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L. , & Ren, Y. (2020). Moral obligation, public leadership, and collective action for epidemic prevention and control: Evidence from the Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19) emergency. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(8), 2731. 10.3390/ijerph17082731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yzerbyt, V. (2020). Foreword. In Jetten J., Reicher S. D., Haslam S. A., & Cruwys T. (Eds.), Together apart: The psychology of COVID‐19 (p. XIV–XV). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C. Q. , Chung, P. K. , Liu, J. D. , Chan, D. K. , Hagger, M. S. , & Hamilton, K. (2019). Health beliefs of wearing facemasks for influenza A/H1N1 prevention: A qualitative investigation of Hong Kong older adults. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health, 31(3), 246–256. 10.1177/1010539519844082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlobina, A. , Dávila, M. C. , & Mitina, O. V. (2020). Am I an activist, a volunteer, both, or neither? A study of role‐identity profiles and their correlates among citizens engaged with equality and social justice issues. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 31(2), 155–170. 10.1002/casp.2491 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Zenodo.org at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4244608, reference number md5:9a772bfc6855c78a2953216c4bbf4f09.