Abstract

Brucella species are gram-negative, facultatively intracellular bacteria that infect humans and animals. These organisms can survive and replicate within a membrane-bound compartment in phagocytic and nonprofessional phagocytic cells. Inhibition of phagosome-lysosome fusion has been proposed as a mechanism for intracellular survival in both types of cells. However, the biochemical mechanisms and microbial factors implicated in Brucella maturation are still completely unknown. We developed two different approaches in an attempt to gain further insight into these mechanisms: (i) a fluorescence microscopy analysis of general intracellular trafficking on whole cells in the presence of Brucella and (ii) a flow cytometry analysis of in vitro reconstitution assays showing the interaction between Brucella suis-containing phagosomes and lysosomes. The fluorescence microscopy results revealed that fusion properties of latex bead-containing phagosomes with lysosomes were not modified in the presence of live Brucella suis in the cells. We concluded that fusion inhibition was restricted to the pathogen phagosome and that the host cell fusion machinery was not altered by the presence of live Brucella in the cell. By in vitro reconstitution experiments, we observed a specific association between killed B. suis-containing phagosomes and lysosomes, which was dependent on exogenously supplied cytosol, energy, and temperature. This association was observed with killed bacteria but not with live bacteria. Hence, this specific recognition inhibition seemed to be restricted to the pathogen phagosomal membrane, as noted in the in vivo experiments.

Brucella species are gram-negative, facultatively intracellular bacteria that infect humans and animals. These organisms can survive and replicate within a membrane-bound compartment in phagocytic (7, 15, 18, 27) and nonprofessional phagocytic (10, 24, 25) cells. Inhibition of phagosome-lysosome fusion has been proposed as a mechanism for intracellular survival in both types of cells. Hence, several reports have described a decrease in the fusion of Brucella-containing phagosomes with lysosomes within macrophages (2, 12, 15, 21). Pizarro-Cerda et al. (24, 25) also recently reported that virulent Brucella abortus avoids lysosome fusion in HeLa cells and replicates in endoplasmic reticulum-like structures.

It has long been known that several bacteria and parasites can inhibit maturation of their phagosomes into phagolysosomes to enable survival and replication within host cells, but the responsible microbial factors have only been identified in a few cases. This maturation inhibition was found to be associated with proteins secreted in the macrophage cytosol; e.g., Salmonella SpiC protein is exported in the host cell cytosol and inhibits cellular trafficking (30). For other parasites, inhibition is associated with the presence of particular surface molecules on the microorganism membrane or on the phagosomal membrane. Hence in Leishmania, maturation inhibition requires lipophosphoglycan (LPG) expression at the parasite surface (9, 29), and in mycobacteria, the TACO host protein present on the phagosomal membrane inhibits maturation into lysosomes (11). For Legionella pneumophila, dot/icm gene products are required to avoid normal trafficking of the L. pneumophila phagosome (28, 31). Some bacterial factors are known to be involved in the maturation of pathogen-containing phagosomes, but the molecular mechanisms implicated are not understood.

We developed in vitro reconstitution assays to determine the molecular mechanisms that regulate fusion during phagosome trafficking and to gain a better insight into the microbial factors that could alter trafficking of pathogen-containing phagosomes. Few in vitro studies have been performed on phagosome maturation, particularly in late steps of the phagocytic pathway. However, reconstitution of phagosome-lysosome fusion has been obtained by Funato et al. (13) in a semipermeable cell system with paramagnetic bead-containing phagosomes. Elsewhere, Jahraus et al. (16) have reported fusion between latex bead-containing phagosomes and purified lysosomes. However, no studies have been conducted with bacteria, particularly pathogenic bacteria, concerning this late step.

The biochemical mechanisms and microbial factors implicated in Brucella maturation are still completely unknown. Moreover, all experiments concerning Brucella maturation have been conducted in vivo on whole cells through morphological observations with electron microscopy and immunofluorescence. In the present study, we found by fluorescence microscopy that fusion properties of latex bead-containing phagosomes with lysosomes were not modified in the intracellular presence of live Brucella suis. The maturation inhibition seemed to be restricted at the pathogen phagosomal membrane. We developed an in vitro reconstitution assay using a flow cytometry method to elucidate the molecular mechanisms involved in the interaction of B. suis-containing phagosomes with lysosomes from J774 macrophages. We observed a specific association, between killed B. suis-containing phagosomes and lysosomes, which was dependent on exogenously supplied cytosol, energy, and temperature (i.e., normal maturation pattern). This association was observed with killed bacteria but not with live bacteria when using cytosol prepared from noninfected cells. Hence, we concluded that inhibition of this specific association could be due to pathogen-induced phagosomal membrane alterations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

Dextran-rhodamine B (molecular weight of 70,000, neutral); streptavidin–R-phycoerythrin (PE) conjugate; and 6-((6-((biotinoyl)amino)hexanoyl)amino)hexanoic acid, sulfosuccinimidyl ester, sodium salt (biotin-XX, SSE), were purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, Oreg.). R-phycoerythrin-conjugated AffiniPure F(ab′)2 fragment goat anti-human immunoglobulin G, Fcγ fragment specific, was purchased from Immunotech (Marseille, France).

Cell culture.

J774A.1 cells (from a murine macrophage-like cell line) were grown in RPMI 1640 medium with glutamax I (Gibco/BRL) containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum at 37°C and 5% CO2.

Bacterium preparation.

The strain used throughout the experiments was B. suis 1330, which constitutively expresses a green fluorescent protein (GFP), prepared as described elsewhere (17, 22). Bacteria were always opsonized with polyclonal murine anti-Brucella antibodies (26). Killed bacteria were obtained by treatment with gentamicin (300 μg/ml) at 37°C for 30 min. Bacterial growth of 0.2% was observed after plating these preparations at 37°C.

Fluorescence microscopy.

Cells were grown on glass coverslips (105 cells/ml) for 1 day. Lysosomes were then labeled by fluid-phase pinocytosis of 0.1-mg/ml dextran-rhodamine (molecular weight of 70,000) for 1 h. Cells were washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and chased for 1 h. Cells were then infected for 45 min with live B. suis GFP at a ratio of 100 bacteria per cell. After three washes in PBS, cells were reincubated in complete medium containing gentamicin at 30 μg/ml. Postinfection was maintained for various times as indicated in the Fig. 2 legend. Then latex beads (diameter, 1 μm) were internalized into the cells for 45 min. After five washes, cells were reincubated for another 5-h period. Finally, cells were fixed for 20 min with 3% paraformaldehyde. Coverslips were mounted in Mowiol medium and examined either by confocal laser scanning microscopy using a Leica DM RB microscope (Leica Microsystèmes SA, Rueil-Mulmaison, France) or by classical fluorescence microscopy with an inverted Leica DM IRB microscope.

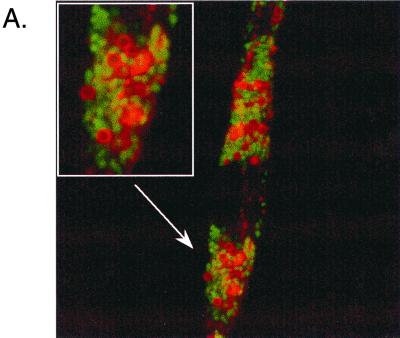

FIG. 2.

Fusion properties of latex bead-containing phagosomes with lysosomes in cells coinfected with live B. suis. Quantitative analysis of fusion was followed by fluorescence microscopy, and J774 macrophages were prepared in the following steps. (i) Lysosomes were loaded with dextran-rhodamine (1-h pulse and 1-h chase). (ii) Cells were infected with live B. suis GFP (45-min infection and postinfection time as indicated in the figure). (iii) Latex beads (diameter, 1 μm) were internalized into the cells (45-min pulse and 5-h chase). (A) Confocal microscopy observation showing a red ring of dextran-rhodamine around latex beads in cells infected with B. suis GFP (3 h postinfection). (B) Quantitative analysis of fusion between latex bead-containing phagosomes and lysosomes in the absence or presence of B. suis in the cell at different times postinfection. Quantitative analysis was performed by classic fluorescence microscopy.

PNS preparation.

In our experiments, two sets of J774A.1 mouse macrophages were prepared. One was infected with B. suis GFP, while the other internalized PE into lysosomes by fluid-phase pinocytosis using specific pulse/chase conditions. Postnuclear supernatants (PNS) were prepared from these cells and used in the in vitro reconstitution assay (Fig. 1A).

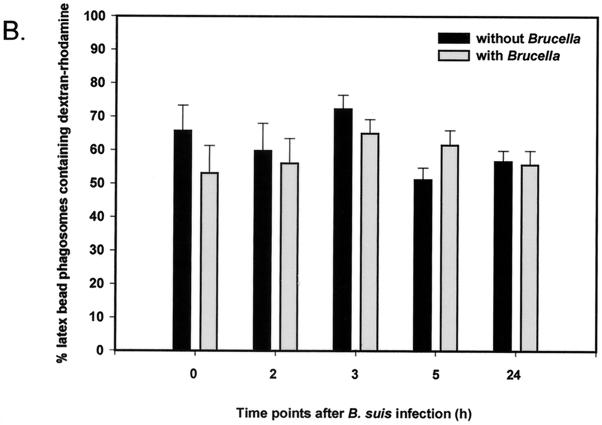

FIG. 1.

Scheme of in vitro assays.

Cells were grown to subconfluence in a 10-cm dish. A total of 40 × 106 cells was necessary for each PNS preparation. In infection experiments, cells were inoculated at a multiplicity of infection of 100 bacteria per cell with late-log-phase cultures of B. suis GFP. After a 45-min infection, cells were washed five times with PBS and further incubated in complete medium containing gentamicin at 30 μg/ml for the indicated postinfection time. Cells were then scraped for PNS preparation.

For lysosome labeling, cells were first scraped and incubated in 0.5 ml of complete medium containing PE at 1 mg/ml for 60 min at 37°C. PE was extracted from red algae (Porphyra tenera) (14). After washing with PBS, macrophages were chased in complete medium for 60 min for specific labeling of lysosomes (16).

All subsequent operations were performed at 4°C. Cells were homogenized in homogenization buffer containing 250 mM sucrose, 0.5 mM EGTA, 0.1% gelatin, 6 mM imidazole (pH 7.4), and a protease inhibitor cocktail (Boehringer Mannheim) (20). The final volume of the homogenate was adjusted to 2 ml with homogenization buffer. Crude PNS was obtained after two centrifugations at 330 × g for 5 min. Concentrated cytosol was prepared from 30 14-cm dishes (109 J774A.1 cells), according to the method described by Blocker et al. (5). Protein concentrations were determined as previously described (6).

In vitro interaction assay.

For each in vitro assay (Fig. 1A), 50 μl of PNS (30 μg of protein) containing B. suis GFP phagosomes was gently mixed with 50 μl of PNS containing PE-labeled lysosomes in the presence of macrophage cytosol prepared from noninfected cells at a final concentration of 1 to 2 mg/ml (8). The medium was adjusted to 10 mM HEPES (pH 7)–1.25 mM MgCl2–1 mM dithiothreitol–50 mM KCl and complemented with 10 μl of an ATP-regenerating system (1:1:1 mixture of 100 mM ATP [pH 7], 800 mM creatine phosphate, and 4 mg of creatine phosphokinase/ml) or 10 μl of an ATP-depleting system (1,500 U of hexokinase [Boehringer]/ml in 0.5 M glucose). The final volume was 170 μl. The incubation was performed at 37°C for 60 min. The biochemical reaction was stopped by transfer to 4°C. The sample volumes were adjusted to 1 ml with PBS and immediately analyzed by flow cytometry.

In vitro fusion assay.

In these experiments (Fig. 1B), PNS was prepared from two sets of cells. One had been infected with B. suis GFP biotinylated by N-hydroxysuccinimide–biotin as described elsewhere (26); the other had internalized streptavidin-PE into lysosomes as follows. Lysosomes were fed for 60 min with streptavidin-PE at 200 μg/ml, and cells were chased for another 60-min period. PNS were prepared as before. The in vitro assays were performed in the presence of avidin (0.25 mg/ml) as the scavenger. After incubation, the membranes were solubilized for 20 min at 37°C with 0.5% Triton X-100 in the presence of avidin at 0.25 mg/ml. Fifty microliters of the total sample was diluted to 1 ml with PBS and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry analysis.

The apparatus used for this analysis was a FACScalibur 3CS (Becton Dickinson) using CellQuest software. The laser excitation wavelength was 488 nm, which allowed excitation of GFP and PE molecules. The filter settings were 530-/30-nm band-pass for fluorescence emission analysis of fluorescein isothiocyanate or GFP (FL1) and 585-/42-nm band-pass for PE (FL2).

RESULTS

Brucella inhibition of phagolysosome formation is restricted to the Brucella phagosome.

Maturation inhibition observed for Brucella phagosomes into phagolysosomes could be dependent on inhibitory factors present on the phagosome or secreted into the host cell cytoplasm. To obtain some information about these agents, we used fluorescence microscopy to study the fusion properties of latex bead-containing phagosomes with lysosomes in J774 macrophages coinfected with live B. suis. Dextran-rhodamine was first internalized into lysosomes, and cells were infected with B. suis GFP for 45 min. At different times postinfection, latex beads were internalized into the cells for 1 h and the fusion properties of latex bead-containing phagosomes with lysosomes were studied at 5 h postinternalization. The transfer of dextran-rhodamine from lysosomes to latex bead-containing phagosomes was clearly observed (Fig. 2A). In contrast, labeling was never observed in B. suis-containing phagosomes. The long period (5 h) after latex bead internalization used in our experiments was necessary to obtain suitable labeling around the beads. Quantitative analysis of fusion in the absence or presence of B. suis is reported in Fig. 2B. At all postinfection times, the fusogenic properties of latex bead-containing phagosomes were not significantly affected. Fusion inhibition was selectively restricted to the B. suis phagosome.

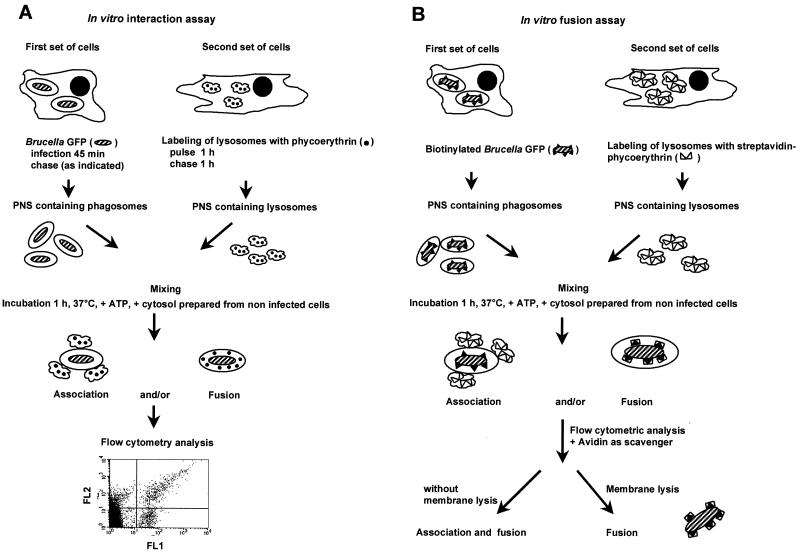

Control of phagosome preparation after cell breakage.

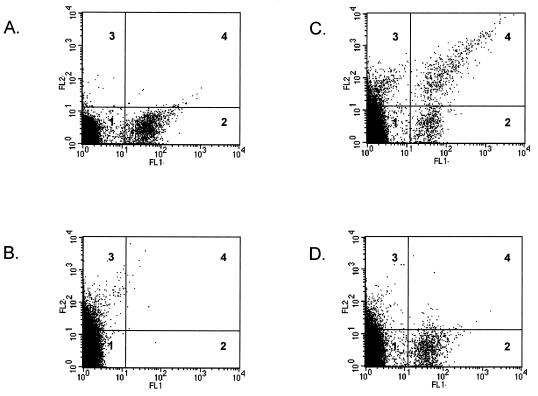

To gain better insight into the reactions and components implicated in phagosome maturation, we developed an in vitro reconstitution assay that allowed us to evaluate the contribution of the three major members of the reaction, i.e., phagosomes, lysosomes, and cytosol. We used a flow cytometry method to analyze formation of the complex. These experiments were performed with phagosomes present in a PNS preparation. To control the integrity of the phagosomal membrane after cell breakage, we used the flow cytometry approach to be able to analyze single organelles. Phagosomes containing B. suis, which constitutively expresses GFP (17, 22), were thus distinguished from cell debris in flow cytometry assays. The accessibility of antibodies against B. suis to the bacteria was used to examine if the phagosomal membrane was still intact after cell breakage. Antibodies against B. suis were detected with a second antibody labeled with PE, a red fluorescent protein, which allowed double fluorescence analysis by flow cytometry. We never observed PE labeling when B. suis GFP-containing phagosomes were incubated with antibodies against B. suis (Fig. 3A). As expected, we obtained double-labeled bacteria under the same conditions but in the presence of Triton X-100 (Fig. 3B). Antibodies were thus unable to reach bacteria in the absence of detergent, showing the integrity of the phagosomal membrane.

FIG. 3.

Control of phagosome preparations after cell breakage by flow cytometry analysis. PNS were prepared from cells infected with B. suis GFP (FL1) and incubated for 10 min at 37°C with human antibodies against B. suis, revealed by a second antibody labeled with PE (FL2) (10 min at 4°C). Incubation was performed in the absence (A) or presence (B) of Triton X-100. PNS were analyzed by dual immunofluorescence. Left, FL1/FL2 dot plot analysis. Right, histogram of relative fluorescence intensity of PE (FL2) in the B. suis GFP region. X represents the mean relative fluorescence intensity.

In vitro recognition of phagosomes and lysosomes.

To study the molecular mechanisms implicated in phagosome maturation in vitro, we developed a biochemical assay in which the different organelles were prepared from two sets of J774A.1 mouse macrophages. One set of cells was infected with B. suis GFP, while the other internalized PE into lysosomes by fluid-phase pinocytosis, using specific pulse/chase conditions. PNS were prepared from these cells and used in the in vitro reconstitution assay. The assay is based on mixing between phagosomes containing B. suis GFP and lysosomes loaded with PE. The formation of double-labeled compartments, monitored by flow cytometry, resulted from the association (and/or fusion) between phagosomes and lysosomes (Fig. 1A).

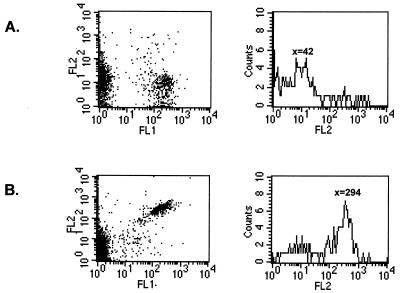

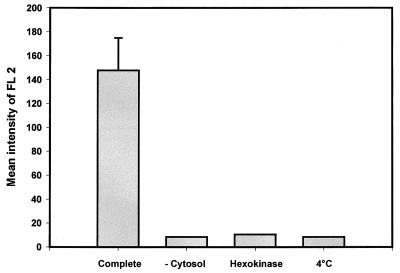

Confocal microscopy observations showed that phagosomes containing live B. suis did not fuse with lysosomes within J774A.1 macrophages, while in contrast, phagosomes containing killed B. suis fused with these compartments (F. Porte, unpublished results). To reproduce this phenomenon in vitro, we developed an assay using gentamicin-killed bacteria. PNS were prepared after 1 h postinfection. Analysis of interactions between B. suis GFP-containing phagosomes and PE-labeled lysosomes was performed by flow cytometry (Fig. 4). In a double analysis of GFP and PE fluorescence (respectively FL1 and FL2), we defined four quadratic regions corresponding to B. suis GFP-containing phagosomes (Fig. 4A, quadrant 2) and PE-labeled lysosomes (Fig. 4B, quadrant 3). When the PNS were incubated together in a complete reconstitution medium in the presence of cytosol and ATP at 37°C for 60 min, we observed a new population of double-labeled organelles in quadrant 4 (Fig. 4C). When the incubation was performed at 4°C, we observed only a marginal number of double-labeled organelles (Fig. 4D). Flow cytometry allowed quantitative analysis of fluorescence, i.e., FL2, corresponding to PE acquired by B. suis GFP-containing phagosomes. Mean relative fluorescence intensities corresponding to different incubation conditions are indicated in Fig. 5. Higher values were obtained when gentamicin-killed bacteria were incubated at 37°C in complete medium (mean value of triplicate assays ± standard deviation, 147.8 ± 27.0). In all other conditions, the values obtained were very low: 8.3 in the absence of cytosol, 10.5 in the presence of an ATP-depleting system, and 8.4 at 4°C. These values were comparable with those obtained in negative controls (PNS with B. suis GFP-containing phagosomes and PNS containing PE-labeled lysosomes alone).

FIG. 4.

In vitro interaction between killed B. suis GFP-containing phagosomes and PE-labeled lysosomes, analyzed by flow cytometry. PNS were prepared from two sets of cells and were immediately analyzed by dual fluorescence. PNS (50 μl) from cells infected with killed B. suis GFP (1 h postinfection) were diluted with 1 ml of PBS (A). PNS (50 μl) from cells pulsed with PE into lysosomes were diluted with 1 ml of PBS (B). Both PNS were incubated together in the presence of cytosol (1 mg/ml) and an ATP-regenerating system at 37°C for 60 min in a final volume of 170 μl; at the end of the reaction, the mix was adjusted to 1 ml with PBS (C). The same assay was performed at 4°C (D). In each assay, 100,000 events were analyzed. Four quadratic regions were defined for each panel: nonlabeled organelles (quadrant 1), killed B. suis GFP-containing phagosomes (quadrant 2), PE-labeled lysosomes (quadrant 3), and double-labeled organelles (quadrant 4).

FIG. 5.

Requirements for the in vitro reconstitution assay. Quantitative analysis of fluorescence intensity (FL2) corresponding to PE acquired in the region of killed B. suis GFP-containing phagosomes was made by flow cytometry. PNS were prepared from cells infected with killed B. suis GFP (1 h postinfection) and from cells pulsed with PE into lysosomes and were incubated together under the following conditions: in complete medium, as described for Fig. 3; in the absence of cytosol; with an ATP-depleting system (hexokinase); or in complete medium at 4°C. At the end of the reaction, the mix was adjusted to 1 ml with PBS. A gate containing B. suis GFP was made in the FL1 histogram, and the mean relative fluorescence intensity of FL2, corresponding to 1,000 events counted in this gate, was given by CellQuest software. The FL2 value in complete medium represents the mean of triplicate assays. The experiments were repeated at least five times.

These results suggest a specific recognition between killed bacterium-containing phagosomes and lysosomes, which was dependent on exogenously supplied cytosol, energy, and temperature.

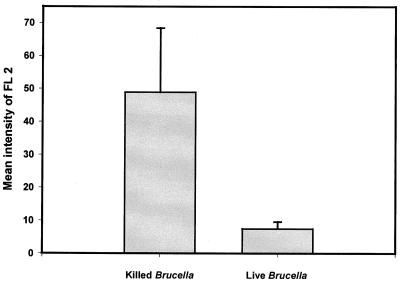

Comparison of phagosome-lysosome interaction between killed and live B. suis.

As noted above, numerous studies have demonstrated that in vivo live Brucella-containing phagosomes do not fuse with lysosomes. It was thus interesting to know whether this phenomenon was due to an absence of recognition of the compartment. A flow cytometry assay was used to study the interaction between live B. suis-containing phagosomes and lysosomes. The experiments were first performed with phagosomes prepared from cells 1 h postinfection. We always observed a decrease in the aggregation reaction in comparison to results obtained with killed B. suis, but the results were highly variable. In an early work, members of our group observed a decrease in bacterial viability within J774 cells during the first hours postinfection (26), which could indicate that some bacteria would be killed by an early phagolysosome fusion process. In order to avoid this drawback, similar experiments were conducted with phagosomes prepared from cells 20 h postinfection, a time at which the intracellular survival curve showed a high rate of bacterial growth (26). The mean relative fluorescence (i.e., FL2), corresponding to PE acquired by live B. suis-containing phagosomes, was compared to values obtained with killed B. suis (Fig. 6). We did not observe a significant association between live B. suis-containing phagosomes and lysosomes, in contrast to the association observed with killed B. suis. As the cytosol used in these studies was prepared from noninfected cells, the phagosome-lysosome interaction inhibition was not linked to the cytosol preparation but rather to phagosomal or bacterial membrane alterations which modified the fusogenic properties of the live B. suis-containing phagosomes.

FIG. 6.

Comparison of phagolysosome association with killed and live B. suis. Quantitative analysis of fluorescence intensity, FL2, corresponding to PE acquired in the region of B. suis GFP-containing phagosomes was made by flow cytometry. PNS from cells infected with killed and live bacteria were prepared 1 and 20 h postinfection, respectively. PNS from cells pulsed with PE into lysosomes were prepared as usual. The in vitro assays were performed in complete medium as described in the text, except that 5 μl of PNS with B. suis GFP-containing phagosomes and 15 μl of PNS containing PE-labeled lysosomes were used and that 25 μl of the total sample was adjusted to 1 ml with PBS before flow cytometry analysis. The mean relative fluorescence intensity of FL2 was given by CellQuest software. The assays were done in triplicate (P = 0.02). The mean intensity of FL2 at 4°C was subtracted from the data shown. The experiments were repeated three times.

Absence of in vitro fusion revealed by experiments using the avidin-biotin affinity system.

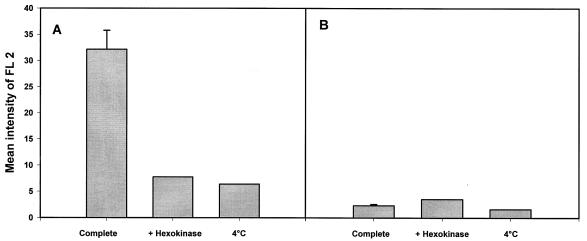

The above experiments revealed a specific interaction, but we could not conclude that there was fusion leading to content mixing between organelles (Fig. 1A). To investigate this possibility, experiments were performed using biotinylated B. suis GFP-containing phagosomes and lysosomes fed with streptavidin-PE. Vesicle fusion was assessed by flow cytometry analysis of streptavidin-PE associated with biotinylated bacteria after membrane lysis. A streptavidin-biotin interaction would occur only in fused organelles and reveal a true mixing of the compartments (Fig. 1B). Experiments were thus performed with killed Brucella. As a control, association was studied after a biochemical assay in the absence of detergent (Fig. 7A). The results were similar to those obtained previously, i.e., energy- and temperature-dependent recognition of killed Brucella-containing phagosomes by lysosomes. Then we added detergent in the assay to solubilize membranes in the presence of avidin as the scavenger, with the aim of measuring possible fusion activity. But we never observed a fusion reaction in our experimental conditions (Fig. 7B).

FIG. 7.

Interaction but not fusion between killed B. suis-containing phagosomes and lysosomes, detected by using the streptavidin-biotin affinity system described for Fig. 1B. Killed bacteria were labeled with N-hydroxysuccinimide–biotin, and PNS from cells infected with these bacteria was prepared 1 h postinfection. For lysosome labeling, cells were pulsed for 60 min with streptavidin-PE and chased for another 60 min. PNS were prepared as usual. The in vitro assays were performed as described in the text, in the presence of avidin as the scavenger. Quantitative analysis of fluorescence intensity (FL2), corresponding to streptavidin-PE acquired in the region of B. suis GFP-containing phagosomes, was made by flow cytometry in the absence (A) and presence (B) of detergent. The assays were carried out in complete medium (in triplicate), with an ATP-depleting system (hexokinase), or in complete medium at 4°C.

DISCUSSION

Brucella species can survive and replicate in the hostile environment of the cell by preventing fusion of their membrane-bound compartment with lysosomes. Several studies have been performed by electron microscopy and immunofluorescence on phagocytes and nonprofessional phagocytes. Recent studies by Pizarro-Cerda et al. (25) with epithelial cells clearly show that the virulent B. abortus strain 2308 multiplies in a compartment devoid of the acid hydrolase cathepsin D, which is present in the lysosomal compartment. On the contrary, latex bead-containing phagosomes acquire this marker 2 h postinternalization (25). In our fluorescence microscopy experiments, using a fluid-phase marker for lysosome labeling, we never observed fusion between live B. suis-containing phagosomes and lysosomes. On the contrary, latex bead-containing phagosomes clearly fused with lysosomes, but the postinternalization time required to obtain good labeling for quantitative analysis was higher (5 h as compared to 2 h in epithelial cells). To date, the mechanisms by which Brucella avoids phagosome-lysosome fusion are completely unknown. Macrophages were coinfected with latex beads and Brucella to obtain information about the nature of microbial factors that could be implicated. We showed that the fusion properties of latex bead-containing phagosomes with lysosomes were not modified in the presence of Brucella at all times after infection. These observations indicated that fusion inhibition was restricted to the pathogen phagosome and that the host cell fusion machinery was not altered by the presence of live Brucella in the cell. We thus hypothesized that Brucella did not secrete into the macrophage cytosol some inhibitor molecule that could interfere with normal cellular trafficking.

To date, only a few studies have described factors present on the phagosomal membrane which prevent phagolysosome biogenesis. Among them, studies have been performed by Desjardins and Descoteaux and others on Leishmania LPG (9, 29). The authors propose a model in which LPG inserts into the phagosomal membrane and prevents fusion by modifying the lipid bilayer. For live mycobacteria, the TACO protein is actively retained on the phagosomal membrane and prevents lysosomal delivery of the pathogen (11). However, it is still unknown how TACO is retained on the membrane. The microbial factors responsible for maturation inhibition of Brucella-containing phagosomes are presently unknown.

To understand phagosomal trafficking and elucidate the molecular mechanisms and microbial factors implicated in phagosome maturation, we developed an in vitro reconstitution assay using a flow cytometry method that was already used for studying homotypic interactions between early endosomes (8). We observed an association between gentamicin-killed Brucella-containing phagosomes and lysosomes (i.e., normal phagosome maturation), which was dependent on exogenously supplied cytosol, energy, and temperature. However, we did not observe a significant association between live Brucella-containing phagosomes and lysosomes. Our results indicated that the phagosome-lysosome recognition observed with killed bacteria was an active phenomenon, dependent on energy and factors present in the cytosol. However, live bacteria were able to prevent this recognition. Since the cytosol and lysosomes were prepared with noninfected cells, we suggested that this inhibition could be due to modifications of the phagosomal membrane. Furthermore, this modification required an active bacterial metabolism.

However, the in vitro assay did not lead to fusion and mixing between compartments. We tried two different methods to obtain this information. First, we used fluorescence resonance energy transfer without success (not shown). Secondly, as shown in Fig. 7, B. suis GFP was labeled with biotin and lysosomes fed with streptavidin-PE. We thus obtained specific recognition with killed B. suis, but we never observed fusion. In conclusion, we developed an in vitro assay that allowed us to separate two steps in the phagosome-lysosome interaction: (i) a specific recognition step and (ii) a fusion step leading to content mixing between organelles. The results suggested that Brucella impaired the first step, i.e., recognition.

In the literature, some in vitro studies have been conducted with different organelles of the endocytic pathway. Stahl's group has published major contributions concerning fusion between phagosomes and endosomes (1, 3, 4, 19, 23), as well as between phagosomes and lysosomes (13). In earlier studies, they reported that it was not possible to reconstitute phagosome-lysosome fusion in vitro (19). Later, however, by using a semipermeable cell system, Funato et al. (13) obtained such a fusion with paramagnetic bead-containing phagosomes, and their results suggest that fusion occurs via microtubule-dependent transport. It thus appears very difficult to reconstitute fusion in a completely in vitro system. On the other hand, Jahraus et al. (16) report in vitro fusion of latex bead-containing phagosomes with lysosomes. Nevertheless, under their in vitro conditions, lysosomes were not very fusogenic in comparison with early and late endosomes. Still, no study has been performed concerning interactions between pathogen-containing phagosomes and lysosomes, so for the first time, we present an in vitro reconstitution assay concerning such an interaction.

In conclusion, we have shown that in the whole cell, maturation inhibition of live B. suis-containing phagosomes was restricted to the pathogen phagosomal membrane and that the host cell fusion machinery was not altered by the presence of the bacteria. The in vitro assay allowed us to observe a specific recognition between killed B. suis-containing phagosomes and lysosomes which was dependent on exogenously supplied cytosol, energy, and temperature. This step, which could precede fusion in the whole cell, was not observed with live B. suis-containing phagosomes, partially confirming in vivo results on the inhibition of fusion of live Brucella-containing phagosomes with lysosomes. Inhibition seemed to be restricted to the pathogen membrane, as we have observed in vivo. The in vitro assay will be useful in further studies on molecular mechanisms implicated in bacterial virulence.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank A. Gross for helpful discussions about fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis and D. O'Callaghan for the kind gift of murine anti-Brucella antiserum.

A. Naroeni was supported by a fellowship from the French government. This work was supported in part by grant PL 980089 from the European Union.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alvarez-Dominguez C, Barbieri A M, Béron W, Wandinger-Ness A, Stahl P. Phagocytosed live Listeria monocytogenes influences rab5-regulated in vitro phagosome-endosome fusion. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:13834–13843. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.23.13834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arenas G N, Staskevich A S, Aballay A, Mayorga L S. Intracellular trafficking of Brucella abortus in J774 macrophages. Infect Immun. 2000;68:4255–4263. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.7.4255-4263.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Béron W, Colombo M I, Mayorga L S, Stahl P D. In vitro reconstitution of phagosome-endosome fusion: evidence for regulation by heterotrimeric GTPases. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1995;317:337–342. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1995.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Béron W, Alvarez-Dominguez C, Mayorga L S, Stahl P D. Membrane trafficking along the phagocytic pathway. Trends Cell Biol. 1995;5:100–104. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)88958-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blocker A, Severin F F, Habermann A, Hyman A A, Griffiths G, Burkhardt J K. Microtubule-associated protein-dependent binding of phagosomes to microtubules. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:3803–3811. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.7.3803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caron E, Liautard J P, Köhler S. Differentiated U937 cells exhibit increased bactericidal activity upon LPS activation and discriminate between virulent and avirulent Listeria and Brucella species. J Leukoc Biol. 1994;56:174–181. doi: 10.1002/jlb.56.2.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chavrier P, van der Sluijs P, Mishal Z, Nagelkerken B, Gorvel J P. Early endosome membrane dynamics characterized by flow cytometry. Cytometry. 1997;29:41–49. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0320(19970901)29:1<41::aid-cyto4>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Desjardins M, Descoteaux A. Inhibition of phagolysosomal biogenesis by the Leishmania lipophosphoglycan. J Exp Med. 1997;185:2061–2068. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.12.2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Detilleux P G, Deyoe B L, Cheville N F. Penetration and intracellular growth of Brucella abortus in nonphagocytic cells in vitro. Infect Immun. 1990;58:2320–2328. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.7.2320-2328.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferrari G, Langen H, Naito M, Pieters J. A coat protein on phagosomes involved in the intracellular survival of mycobacteria. Cell. 1999;97:435–447. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80754-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frenchick P J, Markham J F, Cochrane A H. Inhibition of phagosome-lysosome fusion in macrophages by soluble extracts of virulent Brucella abortus. Am J Vet Res. 1985;46:332–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Funato K, Beron W, Yang C Z, Mukhopadhyay A, Stahl P D. Reconstitution of phagosome-lysosome fusion in streptolysin O-permeabilized cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:16147–16151. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.26.16147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glazer A, Stryer L. Phycofluor probes. Trends Biochem Sci. 1984;9:423–427. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harmon B G, Adams L G, Frey M. Survival of rough and smooth strains of Brucella abortus in bovine mammary gland macrophages. Am J Vet Res. 1988;49:1092–1097. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jahraus A, Tjelle T E, Habermann A, Storrie B, Ullrich O, Griffiths G. In vitro fusion of phagosomes with different endocytic organelles from J774 macrophages. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:30379–30390. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.46.30379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Köhler S, Ouahrani-Bettache S, Layssac M, Teyssier J, Liautard J-P. Constitutive and inducible expression of green fluorescent protein in Brucella suis. Infect Immun. 1999;67:6695–6697. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.12.6695-6697.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liautard J P, Gross A, Dornand J, Köhler S. Interactions between professional phagocytes and Brucella spp. Microbiol SEM. 1996;12:197–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mayorga L S, Bertini F, Stahl P. Fusion of newly formed phagosomes with endosomes in intact cells and in a cell-free system. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:6511–6517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Méresse S, Steele-Mortimer O, Finlay B B, Gorvel J P. The rab7 GTPase controls the maturation of Salmonella typhimurium-containing vacuoles in HeLa cells. EMBO J. 1999;18:4394–4403. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.16.4394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oberti J, Caravano R, Roux J. Attempts of quantitative determination of phagosome-lysosome fusion during infection of mouse macrophages by Brucella suis. Ann Inst Pasteur Immunol. 1981;132D:201–206. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ouahrani-Bettache S, Porte F, Teyssier J, Liautard J P, Köhler S. pBBR1-GFP: a broad-host-range vector for prokaryotic promoter studies. BioTechniques. 1999;26:620–622. doi: 10.2144/99264bm05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pitt A, Mayorga L S, Schwartz A L, Stahl P. Transport of phagosomal components to an endosomal compartment. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:126–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pizarro-Cerda J, Moreno E, Sanguedolce V, Mege J L, Gorvel J P. Virulent Brucella abortus avoids lysosome fusion and distributes within autophagosome-like compartments. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2387–2392. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.5.2387-2392.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pizarro-Cerda J, Méresse S, Parton R G, van der Goot G, Sola-Landa A, Lopez-Goni I, Moreno E, Gorvel J P. Brucella abortus transits through the autophagic pathway and replicates in the endoplasmic reticulum of nonprofessional phagocytes. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5711–5724. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.12.5711-5724.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Porte F, Liautard J P, Köhler S. Early acidification of phagosomes containing Brucella suis is essential for intracellular survival in murine macrophages. Infect Immun. 1999;67:4041–4047. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.8.4041-4047.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Price R E, Templeton J W, Smith III R, Adams L G. Ability of mononuclear phagocytes from cattle naturally resistant or susceptible to brucellosis to control in vitro intracellular survival of Brucella abortus. Infect Immun. 1990;58:879–886. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.4.879-886.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roy C R, Berger K H, Isberg R R. Legionella pneumophila DotA protein is required for early phagosome trafficking decisions that occur within minutes of bacterial uptake. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:663–674. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scianimanico S, Desrosiers M, Dermine J F, Meresse S, Descoteaux A, Desjardins M. Impaired recruitment of the small GTPase rab7 correlates with the inhibition of phagosome maturation by Leishmania donovani promastigotes. Cell Microbiol. 1999;1:19–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.1999.00002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Uchiya K I, Barbieri M A, Funato K, Shah A H, Stahl P D, Groisman E A. A Salmonella virulence protein that inhibits cellular trafficking. EMBO J. 1999;18:3924–3933. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.14.3924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zuckman D B, Hung J B, Roy C R. Pore-forming activity is not sufficient for Legionella pneumophila phagosome trafficking and intracellular growth. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:990–1001. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]