Abstract

Conservation psychology principles can be useful for aligning organizations and scaling up conservation programs to increase impact while strategically engaging partners and communities. We can use findings and recommendations from conservation psychology to inform organizational collaborations between zoos and aquariums to maximize efficiency and coordination. In this study, we developed and evaluated a collaborative conservation initiative for monarch butterflies built with conservation psychology principles. We present our process for collaborative program planning and the resultant collective conservation plan as well as our formative evaluation findings after 1‐year of collaboration. We share best practices for group facilitation and conservation planning along with our evaluation instruments to support future collaborative conservation initiatives.

Keywords: collaboration, community engagement, monarch butterfly, partnership, strategic conservation

Research highlights

The Saving Animals From Extinction Monarch Program facilitated stakeholder engagement and applied behavior change techniques to develop a collaborative plan for monarch conservation.

This evaluation provides insights and tools to promote buy‐in and impact.

A monarch butterfly tagged by the conservation team at Oklahoma City Zoo and Botanical Garden as a part of their participation in the Association of Zoos and Aquariums Saving Animals From Extinction North American Monarch Program.

1. INTRODUCTION

Threats to wildlife are complex problems dependent on widespread action and strategic coordination (United Nations [UN], 2019). From biodiversity crises and pollution, to habitat destruction across landscapes and climate change, these human‐caused threats require human solutions to achieve conservation impact (Schultz, 2011). Yet, conservation leaders have struggled to rally sufficient change to reduce these threats.

Conservation psychology principles could be useful to align organizations and scale up conservation programs to increase impact. From motivational messages designed with psychological research (Pelletier & Sharp, 2008), to social network analysis assessments of resource sharing and stakeholder engagement best practices to build trust (Clayton & Brook, 2005; Mills et al., 2014), use of conservation psychology techniques yields results and recommendations to inform organizational practices and community engagement strategies (McKenzie‐Mohr, 2011). The more people, communities, and/or organizations involved in strategic conservation efforts, the larger the potential for conservation impact (Maynard, Jacobson et al., 2020; Maynard, McCarty et al., 2020; Maynard, Monroe et al., 2020). In this study, we developed and evaluated a collaborative conservation initiative built with conservation psychology principles.

1.1. Collaborative impact

Collaboration is key to increasing conservation impact, but it requires a reframed approach to conservation planning and development. In the past, wildlife conservation projects have often been tied to the brand of individual institutions (Miller et al., 2004), yet conservation problems exceed the reach of a single organization, so partnerships are always needed (Maynard, Jacobson et al., 2020; Maynard, McCarty et al., 2020; Maynard, Monroe et al., 2020). Collaborations across organizations can multiply the audiences and communities reached. For example, collaborative partnerships can promote efficient resource‐sharing, coordinated activities, and extended reach across networks (Austin & Seitanidi, 2012). In this study, we cocreated a collaborative program by convening partners, gathering input from every interested stakeholder for our strategic plan, and linking a collective network focused on the collaboration itself. This paper includes a formative evaluation of this collaborative initiative mobilizing widespread zoos, aquariums and conservation organizations.

As nature‐themed cultural institutions, zoos and aquariums (hereafter referred to as “zoos”) are expected to be involved with the conservation of wildlife and wild places. Conservation psychology principles to frame messages and design communications can be used to engage residents and visitors within zoos in addition to mobilizing organizations to join a partnership (Maynard, Jacobson et al., 2020; Maynard, McCarty et al., 2020; Maynard, Monroe et al., 2020). Such individuals, audiences, and communities need trusted organizations to inspire their involvement. Zoos are trusted community organizations that can meet this challenge (Dickie, 2009). Zoos' audiences expect them to be involved in wildlife conservation and have projects to help save at‐risk species (Che‐Castaldo et al., 2018). With millions of visitors and diverse audiences, zoos can rally their communities to take‐action for wildlife.

Coordinated conservation efforts in zoos are rare; instead, more often zoos and aquariums are working on conservation individually or in small partnerships despite shared goals, missions, and focal species (Maynard, Jacobson et al., 2020; Maynard, McCarty et al., 2020; Maynard, Monroe et al., 2020). Zoos' similar conservation goals and overlapping projects on the same species (Che‐Castaldo et al., 2018) reveal an opportunity for strategic planning and coordination to promote collaboration and improved efficiency. In this study, we developed a collaborative conservation program around one species: the monarch butterfly.

1.2. Monarch butterflies

The monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) is an iconic, long‐distance migratory species spanning North America in two populations split by the Rocky Mountains. Unfortunately, the overwintering populations of monarch butterflies are in steep decline. The Eastern overwintering population has decreased by 80% and the Western population has decreased by over 99% (Pelton et al., 2019; Thogmartin et al., 2017). Insect population decreases are caused by many diverse stresses on the environment and insect conservation requires active intervention and protection (Wagner et al., 2021). In the case of monarch butterflies, multiple confounding factors, including destruction of overwintering habitat, loss of breeding habitat linked to agricultural pesticide use, reduced nectar resources during migrations, and less predictable weather patterns resulting from climate change, are believed to have contributed to current population declines (Belsky & Joshi, 2018; Crone et al., 2019; Pelton et al., 2019).

Rapid decline of the once abundant monarch butterfly has led to movements to list the species for protection. The US Fish & Wildlife Service determined that the species' listing under the Endangered Species Act is warranted by this decline, but they join the long line of other species waiting for federal protection that may or may not be afforded. Monarchs are listed by the IUCN as Near Threatened, and in several US states the butterfly is considered a species of concern (e.g., California Assembly Bill #1671 in 1987) and internationally (e.g., Mexico—Three federal decrees for protection; Canada—listed as a Species of Special Concern nationwide under the Species at Risk Act [SARA] in 2003). Such support for the species' protection at the legislative level emphasizes the urgent need for action throughout its range to ensure its survival. What's more, monarch butterflies are of cultural significance throughout their range, and the number of citizen scientists and home gardens interested in their survival is extraordinarily high, especially for an insect. After opportunities for increased involvement in conservation projects were found across the numerous but disparate efforts in the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) (Che‐Castaldo et al., 2018), the Association of Zoos and Aquariums' Saving Animals From Extinction (AZA SAFE) program was created to rally zoos and aquariums and their communities into even more action for conservation. The AZA SAFE North American Monarch Program is described in this paper.

1.3. Conservation psychology's key to impact

Conservation psychology can enable increased impact for monarch conservation. Best practices in psychology can improve engagement strategies, communications outcomes, and audiences' motivations (Saunders, 2003). For example, humans struggle to understand complex topics or issues distant from their perspectives, such as climate change and urgent insect decline (Simaika & Samways, 2018). Thankfully, conservation psychology supplies solutions to overcome these cognitive challenges to promote action (Markowitz & Shariff, 2012). We can convert abstract and long‐term consequences of pollinator loss to relatable issues by framing them around people's moral values and utilizing motivational messages based on people's needs (McKenzie‐Mohr, 2011; Simaika & Samways, 2018).

Despite years of conservation attention and general public adoration, monarch populations continue to drop rapidly, and effective monarch conservation may depend on increased use of conservation psychology. People's emotional connection to the species and their past experience observing the butterflies, for example, motivate their passion for the species and their willingness to participate in conservation projects such as citizen science programs (Guiney & Oberhauser, 2009). Monarch butterflies can be an exceptional flagship species based on people's experience seeing them in childhood and awe of their metamorphosis and migration (Preston et al., 2021). Using conservation psychology, best practices can help diverse communities and people with ranging perspectives participate in monarch conservation (Lewis et al., 2019). Those with strong positive emotions and awe are more likely to respond to calls‐to‐action and donate money or labor to conservation organizations (Preston et al., 2021). Additionally, communities' perspectives of the conservation strategies, organizations, and outcomes can influence their support or opposition. “To maximize potential support amongst urban residents in the monarch's breeding range, a conservation strategy for the monarch butterfly should be led by not‐for‐profit organizations, should strive for transboundary cooperation, and should include the communication of anticipated ecological outcomes” (Solis‐Sosa et al., 2019, p. 2). As such, conservation psychology was an integral feature in our planning and implementation of the AZA SAFE North American Monarch Program. This study reports on our process and our evaluation of partners' perceptions after 1 year.

2. METHODS

2.1. Conservation psychology components

We utilized interdisciplinary theories, tools, frameworks, and activities to incorporate conservation psychology principles into our collaborative creation of the SAFE Monarch Program Plan. The review of best practices by the program facilitators informed our agendas and format for conducting group discussions to form the partnerships. First, stakeholder engagement best practices enabled the inclusion and amplification of diverse perspectives as the new group formed. These included preparing for and encouraging the stages of group formation as ideas are shared and decisions are made (Tuckman & Jensen, 1977), conducting visioning exercises and facilitated discussions following the Conservation Planning Specialist Group (Kapos et al., 2008), and working toward true exchange in our collaboration rather than transactions or philanthropic partnerships (Austin & Seitanidi, 2012).

Second, we reviewed conservation planning tools from the Open Standards of Conservation to explore strategic steps and indicators of success for wildlife and impact for the targeted audiences (Margoluis et al., 2009; Salafsky et al., 2008). Identifying milestones and anticipated outcomes prepared us to design surveys and data collection plans to evaluate our progress.

Finally, we reviewed conservation psychology research with evidence supporting influential factors for behavior change. While setting up our program plan to coordinate and enhance conservation activities across diverse organizations, we recognized that using best practices about what motivates people could help our initiative be more effective. The important research theories included dimensions of hope (Snyder, 1994), environmental identity (Clayton, 2003), the theory of planned behavior's emphasis on subjective norms and behavioral intention (Ajzen, 1985), value‐belief‐norm theory's utilization of the awareness of consequences to motivate action (Stern, 2000), the importance of self‐efficacy for complex activities (Bandura, 1977), and the spread of ideas through communities with the diffusion of innovations theory (Rogers, 1995). These influential factors were incorporated into our partner discussions and process for growing a collective identity and commitment to the program. We capitalized on opportunities for partners to share ideas with their own network and scale up the program's reach.

2.2. Collaborative program development process

We followed a series of steps to interact with interested partners and gather input to codevelop our monarch conservation plan (Table 1). We sought to partner with any and all interested organizations working on monarch butterfly conservation. Rather than planning activities that may reinvent the wheel of other organizations' current work, this network aims instead to connect the projects to share resources and document the breadth of the work across the species' range, while identifying gaps that new projects or partners could fill. The SAFE Monarch Network facilitates connection between program partners and enables relationships to grow between monarch conservation focused organizations, zoos, and aquariums.

Table 1.

Steps in the development of our collaborative conservation plan for monarchs, and the timeline for the SAFE Monarch Network

| Steps in the collaborative process | Timeline for SAFE Monarchs |

|---|---|

| Send numerous open invitations to all possible interested organizations, using multiple avenues for seeking interested groups | June−September 2019 |

| Host individual meetings with key organizations and provide direct invitations to participate | June−September 2019 |

| Convene stakeholders and introduce process | September 2019 |

| Document current activities and organizations' goals | October 2019 |

| Conduct collective visioning exercise | November 2019 |

| Review and summarize all current monarch conservation plans (state, national, and international) | December 2019 |

| Conduct analysis of influential external factors and develop strategic theory of change | December 2019 |

| Convene topical working groups in which partners self‐select based on their interests and goals | January 2020 |

| Codevelop goals and project activities, define partner participation parameters | February 2020 |

| Submit draft plan for review and improvement | March 2020 |

| Launch after plan approval from AZA | July 2020 |

Abbreviations: AZA, Association of Zoos and Aquariums; SAFE, Saving Animals From Extinction.

2.3. Extend the table

We followed inclusive, strategic leadership techniques to engage more stakeholders in the planning. We sent invitations directly to known monarch conservation organizations and also open invitations for zoos and aquariums to join, regardless of their past conservation projects. By inviting everyone to the table, we set the stage for broad participation without restrictions due to organization type, size, or budget, and we were able to focus on a positive framing of asking for ideas from all participants. We then documented current monarch conservation activities and gave space for partners to share their goals for their work. These data provided a snapshot of the current practices at the organizations as a baseline from which an evaluation would be compared after the program is implemented to assess growth.

2.4. Build the vision together

We conducted a collaborative visioning exercise with all program partners following the facilitated process recommended by the CPSG. Before meeting, we collected via online survey each partners' view of success in 10 years (Table 2). We convened as a group to discuss the collective ideas, common themes and exemplary quotes with descriptive and active suggestions. To do this, we grouped ideas based on themes and topics, and then completed a participatory exercise to highlight and prioritize descriptive phrases to represent each category of topic. Finally, we combined the prioritized phrases to develop long‐term statements about our aspirational mission for monarch butterflies in the future and our operational mission for conservation programs in AZA zoos and aquariums.

Table 2.

Example survey questions used in different steps of our collaborative program development to collect partner input and ideas before large‐group discussion

| Collaborative process step | Example partner survey questions |

|---|---|

| Documenting current organizational practices | When reviewing your institution's current involvement in monarch conservation or awareness efforts, please check all of the activities that apply to your organization:

|

| Collective visioning exercise |

|

| PESTLE analysis (UNICEF, 2019) |

|

Abbreviations: AZA, Association of Zoos and Aquariums; SAFE, Saving Animals From Extinction.

This step was successful with the help of conservation psychology best practices of stakeholder engagement and large‐group facilitation to get contributions from all partners, similar to the process of structured decision‐making (Martin et al., 2009). By discussing our shared hopes for this program and individuals' vision of outcomes in 10 years, we built a collective appreciation for every contributed idea and buy‐in across the group to work together toward this vision. The groups' final vision statements then were the agreed upon goalposts to support goal‐setting and activity planning exercises to strategize how we would achieve our collective visions.

2.5. Use available resources

To organize our conservation plan, we completed a situational assessment following the procedures of the IUCN SSC CPSG. We reviewed 11 current conservation plans for monarch butterflies written by a variety of agencies and organizations for geographic scopes ranging from international (Communications Department of the Secretariat of the Commission for environmental Cooperation [CEC], 2008; Monarch Joint Venture [MJV], 2018), national (National Fish and Wildlife Foundation [NFWF], 2016), regional (Midwest Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies [MAFWA], 2018; Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies [WAFWA], 2019; Xerces 2019;), and state‐specific plans (Indiana Wildlife Federation [IWF], 2018; Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife Resources [KDFWR], 2018; NMPINGP, 2017; OMPC, 2018; Texas Parks and Wildlife [TPW], 2016). We identified the threats to monarchs and activities proposed to address them in each plan and consolidated these into a draft of the foundation for our SAFE Monarch Program Plan. By using social science techniques of qualitative thematic and content analysis, we grouped related ideas and revealed the integral conservation impact opportunities across the species' range.

We held open discussions to invite input from all Program Partners and document the group's collective expertise. We discussed the current threats, goals, scope, and issues for monarch conservation. For example, we held an interactive discussion about influential factors impacting monarchs using a PESTLE analysis of the political, economic, social, technological, legal, and environmental factors as potential external forces impacting monarchs. Incorporating a discussion of the systematic drivers of threats widened the planning discussion beyond individual organizations' preferred activities to incorporate new opportunities for impact (UNICEF, 2019). We integrated our SAFE program partners' ideas of important factors with common themes in the recovery plans to strengthen the foundation of our Program Plan.

2.6. Cocreate goals and activities

Participants self‐divided into small working groups based on their interests and organizational goals. The small groups met to brainstorm goal statements and potential activities for the partners to achieve these goals. We conducted a prioritization exercise to allow partners to weigh in on activities of most importance and urgency. From these lists, we consolidated similar ideas from across the working groups to result in a menu of 15 activities from which SAFE Monarch Network partners could choose (SAFE, 2020, pp. 32−35).

We discussed and agreed on a definition of participation in the SAFE Monarch Program. As partners join this SAFE program, each Program Partner will select at least one new Organizational Activity to implement and enhance their monarch conservation involvement at their institution or in their community. As such, our initial metric for success is that the number of Program Partners' activities is higher across all partners than their number of conservation and engagement activities before the start of the AZA SAFE North American Monarchs program. The objective of this study was to assess this evaluation indicator after 1 year of implementation.

The draft program plan was shared with all partners for collective review for comments, edits, or improvements. Additionally, AZA partners and committee members outside of the SAFE Monarch Network participants reviewed the proposed plan before approving it to launch the program.

2.7. Formative evaluation methods

We conducted a formative evaluation survey 1 year into our program to assess current participation and opportunities for adaptive management of the SAFE Monarch Program. The survey measured organizations' current activities related to monarch conservation, and documented partners' needs for resources or opportunities to improve the steering committee's support of the partners. Additionally, we measured the respondents' hopefulness and self‐efficacy about monarch conservation efforts to identify areas in which we could better motivate and facilitate growing community engagement for monarch conservation. The survey questions can be found in the Supporting Information Material online. Analysis of the evaluation included frequency counts, average responses to the 5‐point Likert‐scale questions, and paired t tests to assess any change in activities over time.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Program development collaborative process

The collaborative process and invitations generated widespread interest and many organizations participated throughout the strategic planning steps. Once the group defined participation, many were quick to sign on as SAFE Monarch Network partners. To date, 109 organizations are active partners in the program working together for monarch conservation.

3.1.1. Vision

The group collaboration activities generated collective buy‐in for our plans, including these vision statements:

Aspirational vision—Native, pollinator‐friendly planting in gardens, cities, and farmlands will become the norm, and people across North America will create a conservation corridor between Canada and Mexico (Eastern population) and western United States and Baja California, Mexico (Western population), leading to annual celebrations of monarch migration and the comeback of the species.

Operational vision—Zoos and aquariums will become the voice of the conservation movement; their reach goes beyond their gates in every community to lead as a driving force for conservation actions and role models of habitat protection and restoration.

3.1.2. Threats

We found the major threats to North American monarchs causing the decline in the population of both the Eastern and Western populations to be: (1) habitat loss decreasing sources of food and other resources (including breeding, nectaring, migratory, and overwintering habitats), (2) pesticides, (3) climate change, and (4) disease. From these categories of threats, the group developed these threat statements to focus our goal‐setting:

-

1.

A lack of native, pesticide‐free milkweed plants for monarch caterpillars and a lack of wildlife friendly, pesticide‐free pollinator habitat for adult monarchs.

-

2.

A lack of connectivity between pollinator habitats preventing migration and climate change resilience.

3.1.3. Goals

The AZA SAFE North American Monarchs' long‐term goal is to increase AZA zoos' and aquariums' conservation leadership across our communities throughout North America to bolster the habitats for monarch butterflies to recover and sustain these butterflies' populations. The program's goals are:

-

1.

Native milkweed supply becomes increasingly available and promoted in each region, rather than potentially harmful tropical milkweed for the Southern tier of the United State.

-

2.

Monarch SAFE, pesticide‐free milkweed identified, developed, made available, and promoted.

-

3.

Increase the number of milkweed plants across monarch range (1.8 billion milkweed stems needed to support Monarch survival [Thogmartin et al., 2017]).

-

4.

Promote wildlife friendly landscaping in urban, suburban, and rural areas for increased monarch habitat that includes increased monarch SAFE flowering plants for adult butterflies.

-

5.

Increase connectivity to ease migration and resilience‐capability in the face of climate change through the SAFE Monarch Network, support for pro‐monarch legislation, and widespread public engagement in all Program Partners' conservation activities.

3.1.4. Activities

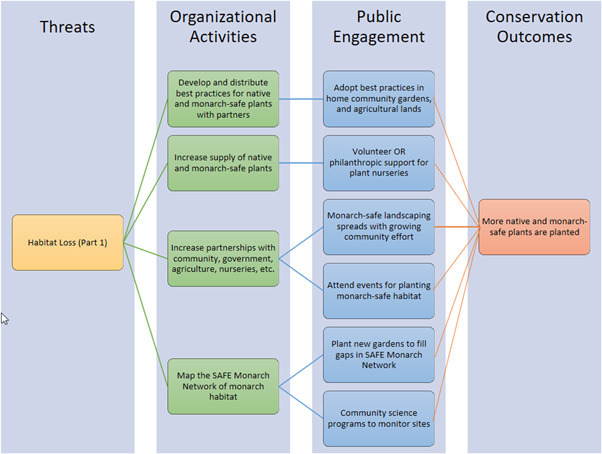

The AZA SAFE North American Monarchs Program Plan aims to facilitate increased organizational activities, followed by increased engagement of the public to address the three major threats to monarch butterflies and create positive conservation outcomes for the species. For each threat, we developed a menu of activities from which program partners can choose for their organization and to promote in their community. Our plan's theory of change explains how our strategies will (1) take new action for monarch conservation, (2) inspire increased action throughout their communities through public engagement, and (3) promote reduction to the threats to monarch butterflies with specific conservation outcomes. Figure 1 demonstrates the theory of change for organizational activities and community engagement to reduce the threat of habitat loss. Additional theories of change for mitigating pesticides and climate change can be found in our program plan (SAFE, 2020).

Figure 1.

Organizational activities, public engagement strategies, and conservation outcomes to reduce habitat loss that threatens North American monarchs. SAFE, Saving Animals From Extinction [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

In addition to the menu of organizational activities that allows partners to self‐select their path to participation in monarch conservation, we used conservation psychology best practices to design social media images and messages to encourage community engagement. In these campaigns, we promoted a menu of ways to participate and positive alternative behaviors to the harmful actions we hope people will increasingly avoid, such as promoting native milkweed over nonnative tropical milkweed (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Example social media image using conservation psychology best practices in the design of the SAFE Monarch Network's Play it SAFE campaign (image designed by the Santa Barbara Zoo). SAFE, Saving Animals From Extinction [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

3.2. Formative evaluation results

The formative evaluation survey received 77 respondents, 4 of which included multiple perspectives from the same partner organization. With 73 distinct organizations represented, the survey response rate was 68% of the 109 participating organizations in the SAFE Monarch Network.

The SAFE Monarch partners participate in a range of monarch conservation activities (Table 3). Education programs and interpretive audience engagement around monarch butterflies and pollinators were the most frequent activities, followed by growing gardens on property and in the community, increasing connectivity to promote climate resilience, promoting partners and resources, developing partnerships, and developing best practices to reduce pesticide use. Despite the COVID‐19 pandemic in 2020, some activities are in practice at more organizations in 2021 than they were in 2019. Overall, the partners have not yet statistically significantly increased their activities for monarch conservation (t 12 = 0.39, p = .70), but they continue to participate and in some cases have added new activities (Table 3).

Table 3.

Frequency of SAFE Monarch Network organizations participating in the range of potential monarch conservation activities

| Monarch conservation activity | 2019 | 2021 | Change (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (N = 71) | % | Yes (N = 73) | % | ||

| Grow pollinator gardens on zoo/aquarium property | 64 | 90.14 | 46 | 63.01 | −27.13 |

| Promote citizen/community science for monarch monitoring | 39 | 54.93 | 26 | 35.62 | −19.31 |

| Promote partners working on monarch conservation | 38 | 53.52 | 30 | 41.10 | −12.43 |

| Provide resources to guide audiences to learn more and help conserve monarchs | 38 | 53.52 | 30 | 41.10 | −12.43 |

| Promote sustainable resource use on behalf of monarchs | 22 | 30.99 | 14 | 19.18 | −11.81 |

| Sell or give away milkweed | 33 | 46.48 | 26 | 35.62 | −10.86 |

| Rear monarch caterpillars for releasea | 15 | 21.13 | 12 | 16.44 | −4.69 |

| Support partners working on monarch conservation through philanthropy | 14 | 19.72 | 16 | 21.92 | 2.20 |

| Advocate for monarch conservation legislation/governance practices | 7 | 9.86 | 9 | 12.33 | 2.47 |

| Monitor monarch populations by zoo/aquarium staff | 23 | 32.39 | 26 | 35.62 | 3.22 |

| Teach conservation education programs about monarchs/pollinators | 49 | 69.01 | 60 | 82.19 | 13.18 |

| Plant pollinator gardens in our community | 31 | 43.66 | 46 | 63.01 | 19.35 |

| Engage visitors via onsite interpretation programs about monarchs/pollinators | 43 | 60.56 | 60 | 82.19 | 21.63 |

| Supporting protection and restoration of overwintering sites | New activities selected during Plan development | 16 | 21.92 | NA | |

| Reviewing and documenting current pesticide use on your property/community gardens | 20 | 27.40 | |||

| Developing best practices for pesticide alternatives and implement on your property/community gardens | 30 | 41.10 | |||

| Promoting best practices for pesticide alternatives and reduced use to audiences, visitors, and community | 14 | 19.18 | |||

| Increasing connectivity and enabling climate resilience with more pollinator habitat | 33 | 45.21 | |||

| Modelling how to reduce fossil fuel consumption on behalf of monarchs | 7 | 9.59 | |||

| Participating in monarch disease monitoring (e.g., OE) | 11 | 15.07 | |||

| Increasing partnerships with community, local organizations, schools, agencies, nurseries, agriculture, etc. | 30 | 41.10 | |||

| Mapping the SAFE Monarch habitat in your property and/or community | 11 | 15.07 | |||

| Fundraising and/or gaining sponsorships using monarchs or pollinators | 17 | 23.29 | |||

Note: We added 10 activities after completing the collaborative conservation planning process (SAFE, 2020), so these activities only have frequency data for 2021. Note that activities increased for some activities but decreased for others, resulting in changes to what activities were emphasized, but no overall difference in activity level from 2019 to 2021.

Abbreviation: SAFE, Saving Animals From Extinction.

Rearing monarchs for release is not considered a conservation activity for the SAFE Monarch Program (SAFE, 2020), but we are monitoring this activity to assess opportunities to guide partners toward activities with more potential for positive impact.

In addition to recording the frequencies of potential conservation activities, we asked our partners in our evaluation about their access to native plants and seeds for their region, or whether they need help or resources to get started. Access to plants is essential for our partners to be able to take action to address the threats to monarchs and create more habitat for the butterflies. Twenty‐nine partners grow such plants themselves, while 11 asked for help getting started growing milkweed and nectar plants at their institutions. Additionally, 47 partners buy seeds and plants for their pollinator gardens, but 9 organizations asked for help finding sources for purchasing native plants in their region. Our evaluation revealed the organizations who have established resources and the others who will benefit from mentorship in growing practices or advice on expert nurseries. In this way, the survey facilitates collaboration and mentorship in the SAFE Monarch Network.

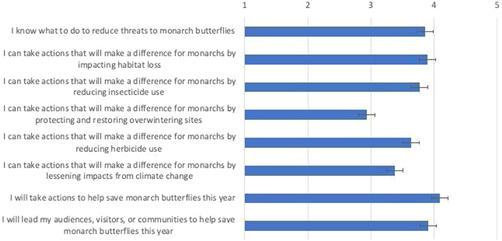

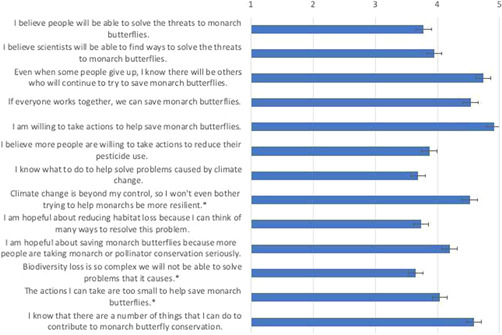

The SAFE Monarch Network partners had an average self‐efficacy of 3.68 out of 5 (standard deviation [SD] = 0.23) and an average hope score of 4.17 out of 5 (SD = 0.10). The respondents are the most confident in their individual ability to take action this year and their capacity to impact the threat of habitat loss (Figure 3). On the other hand, the partners have the lowest self‐efficacy scores for protecting and restoring overwintering sites and mitigating climate change. The respondents have the highest hopes related to people's willingness to take action for butterflies, the number of available activities to impact their threats, and the potential to save monarchs if everyone works together (Figure 4). Partners were the least hopeful about statements focused on biodiversity loss, climate change, habitat loss, and pesticide use.

Figure 3.

Self‐efficacy findings (Bandura, 1977) from one to five for Saving Animals From Extinction (SAFE) Monarch partners regarding types of actions they can take for monarch conservation [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Figure 4.

SAFE Monarch partners' current level of hope (Snyder, 1994) regarding a variety of threats and activities for monarch conservation. *Negative statement which was reverse coded before analysis [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Finally, the formative evaluation assessed the SAFE Monarch partners' needs and barriers as potential opportunities for future support (Table 4). While 8 out of 73 organizations stated they are doing everything they can, for the other partners a lack of time was the largest barrier to participation in monarch conservation efforts. Networking opportunities, training, and chances to practice conservation actions were the next most common, followed by increased support from their leaders and their need for more funding and staff.

Table 4.

Frequency of SAFE Monarch Network partners stating which barriers apply to their organization as hindrances to their participation

| Barriers | Count |

|---|---|

| We need more time | 40 |

| We need more opportunities to hang out with other people and organizations interested in monarch conservation | 25 |

| We need more trainings/practice on the conservation actions | 24 |

| We need more support for monarch conservation from our organizational leadership and/or team | 21 |

| We need more funding and/or staff | 19 |

| We need more knowledge about conservation activities for SAFE monarchs | 17 |

| We need more opportunities to try out conservation actions at our organization | 15 |

| We need more support for monarch conservation from our community | 13 |

| We need clearer and simplified conservation actions | 11 |

| We need more visible results from our organization's conservation actions | 10 |

| We need more interest in the topic | 9 |

| We need more understanding about the impact our organization's own actions make | 8 |

| We need more knowledge about the benefits of conservation actions over our current actions | 8 |

| We need more support for monarch conservation from our visitors and audience | 7 |

| We need more incentives (e.g., recognition, rewards, and swag) | 7 |

| We need more understanding about how conservation actions are compatible with our other organizational missions | 5 |

| We need more understanding about why these activities are important | 3 |

| We need more support from friends/family | 1 |

| Nothing—We're doing everything we can | 8 |

Abbreviation: SAFE, Saving Animals From Extinction.

4. DISCUSSION

Motivating people to take action in conservation is complex yet vital. Influential factors range from designing persuasive messages (Pelletier & Sharp, 2008) based on the target audience's values (Stern, 2000), subjective norms (Ajzen, 1985) or identities (Clayton, 2003), to higher‐level considerations of reducing societal barriers to action (McKenzie‐Mohr, 2011) or coordinating across competing organizations (Maynard, Jacobson et al., 2020; Maynard, McCarty et al., 2020; Maynard, Monroe et al., 2020). Conservation psychology illuminates tools to utilize these significant factors as inspiring shortcuts and translations to reach new audiences. The interdisciplinary lens brings insects into focus by emphasizing people's perspectives alongside the problems their actions can solve (Simaika & Samways, 2018).

4.1. Program development collaborative process

The AZA SAFE North American Monarch Program employed conservation psychology best practices in the development of the collaborative program and our behavior change community engagement strategies. We facilitated participation across a substantial number of zoos, aquariums, and partners by using established stakeholder engagement and strategic planning techniques. The conservation psychology discussion points and activities organized our process while working with an exceptional number of individuals and organizations. For example, the online survey questions before each conference call provided 109 partners with opportunities to voice their interests and built buy‐in for the collective plan in which everyone contributed. Integrating conservation psychology into our AZA SAFE program planning steps increased efficiency and our potential for impact by prioritizing inclusion and behavior change opportunities.

By conducting the extensive process to build our collaborative plan, we highlighted an avenue for zoos and aquariums to step up as conservation leaders. We invited all conservation organizations already involved in monarch conservation to join this network, to align and amplify rather than possibly build redundant or contradictory activities. The SAFE Monarch Network grew beyond other zoo conservation initiatives because we invited any interested partner to join us and we recognized each organization's unique potential to directly help the species. As trusted organizations representing far‐reaching visitors and audiences, every zoo and aquarium can achieve conservation impact by mobilizing their respective communities.

The conservation psychology lens sets the program plan up for success by connecting the organizations' activities directly to opportunities for scaled up community engagement and the specific threats to monarchs that they could address. Every activity was tied to options for encouraging widespread communities to join in for the butterflies. Linking threats to our aspirational vision for the species and operational vision for our organizations provided a springboard for clear goals and activities. Strategic behavior change campaigns then mobilized audiences with diverse messages using psychology best practices about healthy habitats, community science, habitat restoration, and more (Simaika & Samways, 2018).

4.2. Formative evaluation

Evaluating the SAFE Monarch Network partners' perceptions and needs in the middle of our program implementation allowed for reflection on potential improvements and adaptive management. While we did not see a statistically significant increase in the number of partners' activities since 2019, the persistence of activities through the COVID‐19 pandemic is heartening. The changes in activities also could be explained by accessible techniques through social distancing protocols and those not limited by changes in staffing. The goal set by our SAFE Monarch Program Plan (2020) is for the number of activities to be higher by the end of the 3‐year implementation. This evaluation helps us monitor the activities that might require additional support for the partners.

Additionally, we found the partners to have higher levels of hope than their self‐efficacy scores about the monarch conservation activities. The barriers they identified further emphasized ways that the SAFE Monarch Network can support the organizations to enhance their capacity to enact monarch conservation activities by capitalizing on their high amount of hopeful motivation. Since hope has been found to consist of will‐power and way‐power (Snyder, 1994), we can focus our next program facilitation efforts on growing capacity for organizations' activities by capitalizing on their extensive agency and hope.

The conservation psychology foundations for this evaluation also distinguished opportunities for increasing collaboration. Some partners shared their current involvement in the Plan's monarch conservation activities, while others expressed their need for advice or resources to get started. These groupings reveal clear opportunities for mentorship via communication support, problem‐solving, and resource sharing between the actively involved organizations with those getting started.

Future evaluation of the SAFE Monarch Program at the 3‐year point will include the assessment of the number of people involved, their types of involvement in monarch conservation actions, and the impact to the threats to monarchs. Expanding on this formative evaluation for more direct metrics about our desired outcomes will further reveal opportunities for improving the program to increase its effectiveness. Future research on the application of conservation psychology for conservation planning could explore such metrics retrospectively to compare different techniques across other AZA SAFE programs focused on different species.

Next steps for the SAFE Monarch Network could build on these evaluation findings to develop a website or platform to facilitate communications, exchanging resources, reporting new activities, and monitoring key indicators. We also plan to map the activities alongside metrics for the monarch habitat and the threats they face to document the relationship between our partners' activities and our desired conservation outcomes. For example, the SAFE Monarch Program hopes to contribute to the network for monarch migration routes across North America so monitoring the geographic relationships between partners' activities will be essential. Through continued adaptive management and monitoring using conservation psychology, we hope to continue to assess monarch butterflies' needs and ways zoos, aquariums, and our partners can help to save this species.

4.3. Recommendations

For zoos, aquariums, or conservationists considering ways to replicate the conservation psychology process for collaborative planning, we have a few recommendations. We encourage you to grow the plan as a collective group. Inclusion of all interested partners from the beginning was integral for our growth. We also welcomed new partners throughout the program's development and implementation with a clear definition for participation. The menu for self‐selecting organizations' activities jumpstarted partners to sign‐on because participation was not dependent on their amount of funds available or their prior status in this species' conservation efforts. Instead, partners defined their participation based on their interest and willingness to commit to new activities for their organization.

We also encourage interested organizations to follow the process for open discussion, even if you have leaders with extensive knowledge and prior experience on the topic. By listening to all partners and considering every idea for the group's plan, you will build trust and relationships to motivate partners to interact with each other and commit to implementing new activities at their organization. The process can take time to gather input and consider the range of ideas, but a facilitator can help you to rank and prioritize decision‐making later on. AZA institutions have widespread social scientists with expertise in conservation psychology who could help with this process, so consider contacting the AZA Social Science Research and Evaluation Scientific Advisory Group before you get started (Social Science Research and Evaluation Scientific Advisory Group [SSRE], 2020).

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

All the research meets the ethical guidelines and requirements of Zoo Biology. The protocol for partner surveys and data collection were reviewed by the Institutional Review Board at Miami University and the study was given exempt status and approved, allowing for the research to proceed (04706e).

Supporting information

Supporting information.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to the 111 partner organizations which have joined the SAFE Monarch Network so far and codeveloped our interactive conservation program. We want to thank the butterfly and pollinator conservation community and leading organizations for welcoming us to the conversation and sharing resources with us to ensure we build on best practices and work together toward impact for monarch butterflies. Thank you to the AZA SAFE and AZA Wildlife Conservation Committee leadership for their support of this program's development.

Maynard, L. , Howorth, P. , Daniels, J. , Bunney, K.‐L. , Snyder, R. , Jenike, D. , Barnhart, T. , Spevak, E. , Fitzgerald, P. , & Gezon, Z. (2022). Conservation psychology strategies for collaborative planning and impact evaluation. Zoo Biology, 41, 425–438. 10.1002/zoo.21692

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Ajzen, I. (1985). From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In action control (pp. 11–39). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, J. E. , & Seitanidi, M. M. (2012). Collaborative value creation: A review of partnering between nonprofits and businesses: Part 1. Value creation spectrum and collaboration stages. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 41(5), 726–758. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self‐efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84, 191–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky, J. , & Joshi, N. K. (2018). Assessing role of major drivers in recent decline of monarch butterfly population in North America. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 6, 86. 10.3389/fenvs.2018.00086 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Che‐Castaldo, J. P. , Grow, S. A. , & Faust, L. J. (2018). Evaluating the contribution of North American zoos and aquariums to endangered species recovery. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton, S. (2003). Environmental identity: A conceptual and an operational definition. In Clayton S. & Opotow S. (Eds.), Identity and the natural environment: The psychological significance of nature (pp. 45–66). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Clayton, S. , & Brook, A. (2005). Can psychology help save the world? A model for conservation psychology. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 5(1), 87–102. [Google Scholar]

- Communications Department of the Secretariat of the Commission for environmental Cooperation (CEC) . (2008). North American monarch conservation plan. https://www.fs.fed.us/wildflowers/pollinators/Monarch_Butterfly/news/documents/Monarch-Monarca-Monarque.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Crone, E. E. , Pelton, E. M. , Brown, L. M. , Thomas, C. C. , & Schultz, C. B. (2019). Why are monarch butterflies declining in the West? Understanding the importance of multiple correlated drivers. Ecological Applications, 29(7), 01975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickie, L. A. (2009). The sustainable zoo: An introduction. International Zoo Yearbook, 43(1), 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Guiney, M. S. , & Oberhauser, K. S. (2009). Conservation volunteers' connection to nature. Ecopsychology, 1(4), 187–197. [Google Scholar]

- Indiana Wildlife Federation (IWF) . (2018, 10 August). Indiana monarch conservation plan. https://www.indianawildlife.org/lib/uploads/files/Indiana%20Monarch%20Conservation%20Plan_8-10-18.pdf

- Kapos, V. , Balmford, A. , Aveling, R. , Bubb, P. , Carey, P. , Entwistle, A. , & Walpole, M. (2008). Calibrating conservation: New tools for measuring success. Conservation Letters, 1(4), 155–164. [Google Scholar]

- Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife Resources (KDFWR) . (2018). Kentucky monarch conservation plan. https://fw.ky.gov/Wildlife/Documents/ky_monarch_plan.pdf

- Lewis, A. D. , Bouman, M. J. , Winter, A. , Hasle, E. , Stotz, D. , Johnston, M. K. , & Czarnecki, C. (2019). Does nature need cities? Pollinators reveal a role for cities in wildlife conservation. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 7, 220. [Google Scholar]

- Margoluis, R. , Stem, C. , Salafsky, N. , & Brown, M. (2009). Design alternatives for evaluating the impact of conservation projects. New Directions for Evaluation, 122, 85–96. [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz, E. M. , & Shariff, A. F. (2012). Climate change and moral judgement. Nature Climate Change, 2(4), 243–247. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, J. , Runge, M. C. , Nichols, J. D. , Lubow, B. C. , & Kendall, W. L. (2009). Structured decision making as a conceptual framework to identify thresholds for conservation and management. Ecological Applications, 19(5), 1079–1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard, L. , Jacobson, S. K. , Monroe, M. C. , & Savage, A. (2020). Mission impossible or mission accomplished: Do zoo organizational missions influence conservation practices? Zoo Biology, 39(5), 304–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard, L. , McCarty, C. , Jacobson, S. K. , & Monroe, M. C. (2020). Conservation networks: Are zoos and aquariums collaborating or competing through partnerships? Environmental Conservation, 47(3), 166–173. [Google Scholar]

- Maynard, L. , Monroe, M. C. , Jacobson, S. K. , & Savage, A. (2020). Maximizing biodiversity conservation through behavior change strategies. Conservation Science and Practice, 2(6), e193–e314. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie‐Mohr, D. (2011). Fostering sustainable behavior: An introduction to community‐based social marketing. New Society Publishers. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midwest Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies (MAFWA) . (2018, 11 May). Mid‐America monarch conservation strategy 2018−2038. https://www.mafwa.org/wpcontent/uploads/2018/07/MAMCS_June2018_Final.pdf

- Miller, B. , Conway, W. , Reading, R. P. , Wemmer, C. , Wildt, D. , Kleiman, D. , & Hutchins, M. (2004). Evaluating the conservation mission of zoos, aquariums, botanical gardens, and natural history museums. Conservation Biology, 18(1), 86–93. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, M. , Álvarez‐Romero, J. G. , Vance‐Borland, K. , Cohen, P. , Pressey, R. L. , Guerrero, A. M. , & Ernstson, H. (2014). Linking regional planning and local action: Towards using social network analysis in systematic conservation planning. Biological Conservation, 169, 6–13. [Google Scholar]

- Monarch Joint Venture (MJV) . (2018). Monarch conservation implementation plan. https://monarchjointventure.org/images/uploads/documents/2018_monarch_conservation_implementation_plan_final_2.pdf

- Monarchs Collaborative Steering Committee (MCSC) . (2019, 30 April). Missouri monarch and pollinator conservation plan. https://dnr.mo.gov/education/documents/MOforMonarchs-ConservPlan.pdf

- National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF) . (2016, 9 August). Monarch butterfly business plan. https://www.nfwf.org/monarch/Documents/monarch-business-plan.pdf

- Nebraska Monarch Pollinator Initiative and Nebraska Game and Parks (NMPINGP) . (2017. , September). Conservation strategy for monarchs (Danaeus plexippus) and at‐risk pollinators in Nebraska. https://outdoornebraska.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Monarch-Pollinator-Plan_NE_without-plant-appendix_Sept2017.pdf

- Oklahoma Monarch and Pollinator Collaborative (OMPC) . (2018, April). Oklahoma monarch and pollinator collaborative statewide monarch conservation plan. http://www.okiesformonarchs.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/OMPC-Monarch-Conservation-Plan.pdf

- Pelletier, L. G. , & Sharp, E. (2008). Persuasive communication and proenvironmental behaviours: How message tailoring and message framing can improve the integration of behaviours through self‐determined motivation. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 49(3), 210–217. [Google Scholar]

- Pelton, E. M. , Schultz, C. B. , Jepsen, S. J. , Black, S. H. , & Crone, E. E. (2019). Western monarch population plummets: Status, probable causes, and recommended conservation actions. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 7, 258. 10.3389/fevo.2019.00258 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Preston, S. D. , Liao, J. D. , Toombs, T. P. , Romero‐Canyas, R. , Speiser, J. , & Seifert, C. M. (2021). A case study of a conservation flagship species: The monarch butterfly. Biodiversity and Conservation, 30(7), 2057–2077. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, E. M. (1995). Diffusion of Innovations: Modificiations of a model for telecommunications. In Die diffusion von innovationen in der telekommu (pp. 25–38). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- SAFE Monarch Program Plan . (2020). Association of zoos and aquariums. https://assets.speakcdn.com/assets/2332/program_plan_safe_north_american_monarch_2020-2023.pdf

- Salafsky, N. , Salzer, D. , Stattersfield, A. J. , Hilton‐Taylor, C. R. A. I. G. , Neugarten, R. , Butchart, S. H. , & Wilkie, D. (2008). A standard lexicon for biodiversity conservation: Unified classifications of threats and actions. Conservation Biology, 22(4), 897–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, C. D. (2003). The emerging field of conservation psychology. Human Ecology Review, 137–149. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, P. W. (2011). Conservation means behavior. Conservation Biology, 25(6), 1080–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simaika, J. P. , & Samways, M. J. (2018). Insect conservation psychology. Journal of Insect Conservation, 22(3), 635–642. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, C. R. (1994). The psychology of hope. Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Social Science Research and Evaluation Scientific Advisory Group (SSRE) . (2020). Association of zoos and aquariums. https://www.aza.org/social-science-research-and-evaluation-scientific-advisory-group?locale=en

- Solis‐Sosa, R. , Semeniuk, C. A. , Fernandez‐Lozada, S. , Dabrowska, K. , Cox, S. , & Haider, W. (2019). Monarch butterfly conservation through the social lens: Eliciting public preferences for management strategies across transboundary nations. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 7, 316. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, P. C. (2000). New environmental theories: Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. Journal of Social Issues, 56(3), 407–424. [Google Scholar]

- Texas Parks and Wildlife (TPW) . (2016, April). Texas monarch and native pollinator conservation plan. https://tpwd.texas.gov/publications/pwdpubs/media/pwd_rp_w7000_2070.pdf

- Thogmartin, W. E. , Diffendorfer, J. E. , López‐Hoffman, L. , Oberhauser, K. , Pleasants, J. , Semmens, B. X. , Semmens, D. , Taylor, O. R. , & Wiederholt, R. (2017). Density estimates of monarch butterflies overwintering in central Mexico. PeerJ, 5, e3221. 10.7717/peerj.3221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuckman, B. W. , & Jensen, M. A. C. (1977). Stages of small‐group development revisited. Group & Organization Studies, 2(4), 419–427. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF . (2019). Knowledge exchange: SWOT and PESTEL. https://sites.unicef.org/knowledge-exchange/files/SWOT_and_PESTEL_production.pdf

- United Nations (UN) . (2019). Nature's dangerous decline ‘unprecedented’; species extinction rates ‘accelerating’. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/blog/2019/05/nature-decline-unprecedented-report/

- Wagner, D. L. , Grames, E. M. , Forister, M. L. , Berenbaum, M. R. , & Stopak, D. (2021). Insect decline in the Anthropocene: Death by a thousand cuts. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies (WAFWA) . (2019, January). Western monarch butterfly conservation PLAN 2019–2069. https://www.wafwa.org/Documents/and/Settings/37/Site/Documents/Committees/Monarch/Western/Monarch/Butterfly/Conservation/Plan/2019-2069.pdf

- Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation . (2019). Western monarch call to action. https://xerces.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/19-001_Western-monarch-call-toaction_XercesSociety.pdf

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting information.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.