Abstract

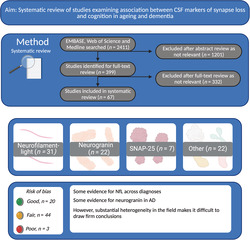

A biomarker associated with cognition in neurodegenerative dementias would aid in the early detection of disease progression, complement clinical staging and act as a surrogate endpoint in clinical trials. The current systematic review evaluates the association between cerebrospinal fluid protein markers of synapse loss and neuronal injury and cognition. We performed a systematic search which revealed 67 studies reporting an association between cerebrospinal fluid markers of interest and neuropsychological performance. Despite the substantial heterogeneity between studies, we found some evidence for an association between neurofilament‐light and worse cognition in Alzheimer's diseases, frontotemporal dementia and typical cognitive ageing. Moreover, there was an association between cerebrospinal fluid neurogranin and cognition in those with an Alzheimer's‐like cerebrospinal fluid biomarker profile. Some evidence was found for cerebrospinal fluid neuronal pentraxin‐2 as a correlate of cognition across dementia syndromes. Due to the substantial heterogeneity of the field, no firm conclusions can be drawn from this review. Future research should focus on improving standardization and reporting as well as establishing the importance of novel markers such as neuronal pentraxin‐2 and whether such markers can predict longitudinal cognitive decline.

Keywords: Alzheimer disease, biomarkers, cerebrospinal fluid, cognition, cognitive aging, dementia

We conducted a systematic review of studies examining the association between cerebrospinal fluid markers and neuropsychological performance. Despite substantial heterogeneity in the field, there was some evidence of an association between cognition and neurofilament‐light and neurogranin. Risk of bias in the field requires improvement (Created with Biorender.com).

1. INTRODUCTION

Dementia is a syndrome characterised by progressive cognitive decline. An estimated 50 million people are living with a form of dementia worldwide, which is expected to reach 82 million by 2030 (World Health Organisation, 2020). The identification of a biomarker which correlates with cognition would have numerous benefits. An earlier indication of the pathophysiological processes underlying cognitive impairment is needed, as neuronal loss precedes detectable cognitive symptoms and so may be used to predict prognosis (Counts et al., 2017; DeKosky & Marek, 2003). Moreover, such markers could benefit our aetiological understanding of dementias as different synaptic markers could reflect different pathophysiological mechanisms. Next, in clinical trials, they could be used as surrogate endpoints for synapse‐targeting pharmacological interventions and could aid in the selection of participants who are in the earliest stages of dementia (Atri, 2011; Yiannopoulou & Papageorgiou, 2013). However, at present, there are no widely used biomarkers that predict cognitive status or cognitive decline in dementias.

Alzheimer's disease, the leading cause of dementia (World Health Organisation, 2020), is characterised by the pathological hallmarks of extracellular deposition of amyloid‐β (Aβ), intracellular accumulation of abnormally hyperphosphorylated tau into neurofibrillary tangles and brain atrophy due to neuronal and synapse loss (Blennow et al., 2006). These hallmarks of AD are present in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and even before detectable symptoms begin to emerge—with Aβ accumulation possibly beginning up to two decades before symptom manifestation (Counts et al., 2017; Jack et al., 2010). Changes in the levels of these pathological proteins in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) have been observed as they aggregate in the brain and so the CSF may be a viable source of potential biomarkers.

The cerebrospinal fluid is a clear liquid which surrounds the brain and provides mechanical support, transfers micronutrients and signalling molecules to neurons and is involved in the removal of unnecessary metabolites (Spector et al., 2015). The CSF is an ideal source for biomarkers associated with cognition as it directly interacts with the extracellular space of the brain and so it can reflect the occurrence of pathophysiological changes (Hampel et al., 2012). In AD, the deposition of extracellular Aβ is reflected by reduced CSF levels of the 42‐amino acid form of Aβ (Aβ42) or the Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio, likely reflecting the reduced clearance of the protein (Potter et al., 2013; Tarasoff‐Conway et al., 2015). In contrast, levels of both total tau (t‐tau) and phosphorylated tau (p‐tau) are increased in the brain and in the CSF in AD (Counts et al., 2017; Ortega et al., 2019; Savage et al., 2014). These core CSF biomarkers of AD have high diagnostic accuracy (Counts et al., 2017; Ortega et al., 2019; Savage et al., 2014) and can predict conversion from MCI to AD (Caminiti et al., 2018; Li et al., 2016; Ortega et al., 2019). Indeed, they are currently accepted in international diagnostic criteria for use in the research diagnosis of AD and pre‐clinical AD (Dubois et al., 2014; Jack et al., 2018). However, despite the utility of these core CSF biomarkers as diagnostic tools, they correlate weakly with cognitive impairment. Studies report weak or no significant associations between cognitive performance and CSF Aβ (Kester et al., 2009; Ottoy et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2009) and moderate‐to‐poor relationships with CSF t‐tau and p‐tau (Buchhave et al., 2009; Ecay‐Torres et al., 2018; Mattsson, Schöll, et al., 2017; Wattmo et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2009). Meanwhile, other neurodegenerative dementias such as frontotemporal dementia (FTD), vascular dementia (VaD) and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) also lack a validated biomarker that associated with cognition. For example, CSF t‐tau and p‐tau can accurately discriminate FTD from controls (Meeter, Vijverberg, et al., 2018) but only have a moderate‐to‐weak correlation with neuropsychological performance (Bian et al., 2008; Borroni et al., 2011; Goossens et al., 2018). Accordingly, there is a need for additional validated CSF biomarkers which correlate with cognition and biomarkers of synapse loss that have been proposed as potential candidates.

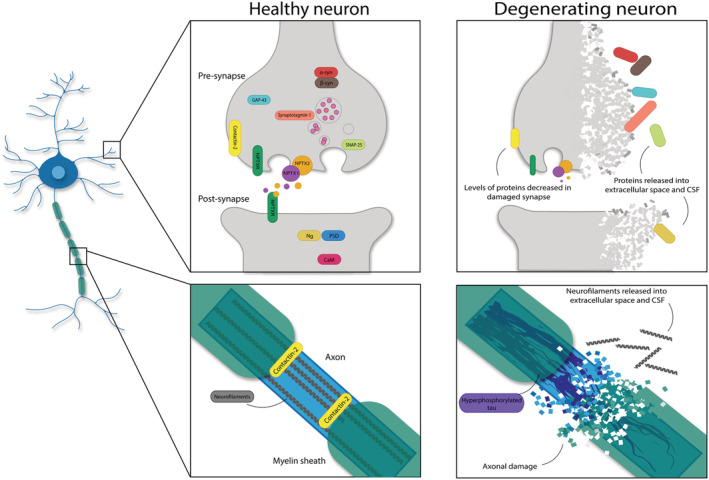

Healthy synapse function enables neuronal signal transmission to occur, which is facilitated by pre‐synaptic and post‐synaptic compartments. Synaptic plasticity, formation, maturation and elimination involve processes essential for learning and memory, namely, long‐term potentiation (LTP) and long‐term depression (LTD) (Bear & Malenka, 1994). LTP refers to the strengthening of synaptic transmission by the addition of new receptors at the post‐synaptic density and the enlargement of dendritic spine heads. Conversely, LTD refers to the weakening of synaptic strength and spine shrinkage/loss (Citri & Malenka, 2008). The total number of synapses in the brain decreases with typical ageing, which is exacerbated in AD and other dementias (Bertoni‐Freddari et al., 1990; DeKosky & Scheff, 1990; Masliah et al., 1994, 2006). What is more, synapse loss is the strongest pathological correlate of cognitive decline in AD (De Wilde et al., 2016; DeKosky & Scheff, 1990; Masliah et al., 1994; Terry et al., 1991). Accordingly, CSF markers of synapse loss would be expected to correlate with cognitive impairment. Indeed, a number of CSF synapse and neuronal marker levels are altered in dementia syndromes and age‐related cognitive decline, some of which will be discussed. Before continuing, it is important to note that any CSF biomarker associated with cognition is primarily a marker of changes in the brain. Such pathophysiological changes may lead to neuronal network breakdown/damage, which may translate into cognitive symptoms at a point in the future. Therefore, the term ‘biomarker for cognition’ is erroneous and should be avoided.

1.1. Neurofilament‐light

Neurofilaments are classed as type IV intermediate filaments and are primarily located in axons. They play essential roles in radial growth, cytoskeletal support and transmission of electrical impulses along axons (Fuchs & Cleveland, 1998; Petzold, 2005). Neurofilaments are heteropolymers and are composed of four subunits in the CNS: neurofilament‐light (NfL), neurofilament‐medium (NfM), neurofilament‐heavy (NfH) and α‐internexin, of which NfL is the essential component. CSF NfL has been established as a general marker of axonal damage across neurodegenerative diseases as NfL is released into the extracellular fluid following axonal injury (Petzold, 2005). Indeed, CSF NfL levels correlate with brain atrophy (Dhiman et al., 2020; Pereira et al., 2017) and are elevated across dementias, MCI (Olsson et al., 2016; Petzold et al., 2007; Rosengren et al., 1999; Zetterberg et al., 2016) and neurodegenerative diseases such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and Parkinson's disease (PD) (Gaetani et al., 2019).

1.2. Neurogranin (Ng)

Ng is a post‐synaptic peripheral membrane protein involved in LTP and memory formation. Ng binds calmodulin (CaM) in the absence of calcium (Ca2+) and thus regulates CaM availability (Petersen & Gerges, 2015). In the AD brain, full‐length Ng levels are reduced (Kvartsberg et al., 2019; Reddy et al., 2005), whereas CSF levels are increased in AD and MCI (Dulewicz et al., 2020). Elevated CSF Ng levels appear to be specific to AD, rather than reflecting general synapse damage in other neurodegenerative diseases or dementias (Portelius et al., 2018; Wellington et al., 2016).

1.3. Pre‐synaptic and neuronal markers

Cerebrospinal fluid levels of proteins localised at the pre‐synapse and post‐synapse are an obvious choice for a CSF marker of synapse loss/damage. The localization and normal function of such proteins suggest that they could be adequate surrogate markers for synapse loss, as they may be released into the extracellular fluid following synapse damage (Vergallo et al., 2018). Both NfL and Ng are some of the most researched markers. Next, we briefly discuss other pre‐synaptic and neuronal markers with a short description of their function, localization and potential roles in dementia syndromes.

Alpha‐synuclein (α‐syn) is a pre‐synaptic protein, expressed predominately in the neocortex and subcortical areas, including the hippocampus (Emamzadeh, 2016; Kim et al., 2014). Aggregates of hyperphosphorylated, misfolded α‐syn are the main component of Lewy bodies (LBs), the characteristic pathological accumulates of α‐synucleinopathies such as PD, Parkinson's disease dementia (PDD) and DLB (Kim et al., 2014). The normal function of α‐syn is not fully understood; however, it is thought to be involved in vesicle fusion and neurotransmitter release (Kim et al., 2014). The localization and normal function of α‐syn suggests that it could be used as a surrogate marker for synapse loss as it may be released into the extracellular fluid following synapse damage (Vergallo et al., 2018). Studies measuring full‐length α‐syn (rather than LB‐specific fragments) report significant elevations in AD and MCI and those with α‐synucleinopathies (Hansson et al., 2014; Korff et al., 2013; Slaets et al., 2014).

Beta‐synuclein (β‐syn) is a pre‐synaptic protein which is highly enriched in the hippocampus (Uhlén et al., 2015). It is homologous to and co‐localises with α‐syn (Williams et al., 2018). The normal function of β‐syn is unknown, although there is evidence to suggest that it has a role in the inhibition of α‐syn aggregation (Williams et al., 2018). Independent of its pathological form, β‐syn may be a good marker of synapse loss due to its localization at the pre‐synapse.

Contactin‐2 is a pre‐synaptic and axonal protein (Furley et al., 1990), expressed in frontal and temporal lobes—including hippocampal pyramidal cells (Gautam et al., 2014; Murai et al., 2002). Contactin‐2 is involved in axonal guidance during development, neuronal fasciculation and axonal domain organisation (Masuda, 2017; Wolman et al., 2008). In AD, contactin‐2 levels are reduced in the brain (Chatterjee, Del Campo, et al., 2018; Gautam et al., 2014) and altered in the CSF, although findings are somewhat discrepant with regard to whether CSF levels are elevated or decreased (Chatterjee, Del Campo, et al., 2018; Yin et al., 2009). Contactin‐2 may be a potential marker of general synapse and axonal damage for neurodegenerative diseases as CSF levels are also increased in multiple sclerosis (MS) (Chatterjee, Koel‐Simmelink, et al., 2018).

GAP‐43 is a pre‐synaptic protein widely expressed in the CNS during the development, which reduces with maturation (Holahan, 2017). In adulthood, GAP‐43 is expressed in hippocampal pyramidal cells and association cortices (Chung et al., 2020; Neve et al., 1988; Riascos et al., 2014) and is involved in axonal outgrowth, synaptic plasticity and functions associated with learning and memory (Chung et al., 2020; Holahan, 2017). Levels of GAP‐43 in the frontal cortex are reduced in a number of dementia syndromes (Bogdanovic et al., 2000; Davidsson & Blennow, 1998; Rekart et al., 2004). Moreover, CSF GAP‐43 levels are increased in AD, FTD‐syndromes (Remnestål et al., 2016) and other neurodegenerative diseases such as PD and ALS (Sandelius et al., 2019).

The neuronal pentraxin family includes neuronal pentraxin I (NPTX1), neuronal pentraxin 2 (NPTX2) and neuronal pentraxin receptor (NPTXR) which are highly enriched in excitatory pyramidal neurons of the hippocampus and cerebellum (Chang et al., 2010; Dodds et al., 1997). All three neuronal pentraxins are involved in developmental and adult synaptic plasticity, formation and remodelling, as well as the maintenance of parvalbumin interneuron activity (Chang et al., 2010; Osera et al., 2012). NPTX1/2 are secreted pre‐synaptic proteins, whereas NPTXR is a membrane‐anchored protein (Lee et al., 2017). In the brain and the CSF, NPTX2 levels are reduced in AD, MCI, FTD and aged controls (Soldan et al., 2019; van der Ende et al., 2020, 2019; Xiao et al., 2017).

Neuregulin 1 (nrg1), a substrate of BACE1, is a pre‐synaptic protein thought to be implicated in a number of neurodegenerative diseases and psychiatric/neurodevelopmental disorders such as AD, attention deficit hyperactive disorder (ADHD) and schizophrenia (Shi & Bergson, 2020). Nrg1 is thought to be involved in synaptic transmission and plasticity (Fischbach, 2007); however, at least 31 isoforms have been described which all perform a broad range of functions throughout the body. It is unclear whether Nrg1 in the brain exerts protective or detrimental effects on cognition as both high and low levels of Nrg1 at synapses lead to cognitive impairment in animal models (Agarwal et al., 2014). There are no known human post‐mortem brain studies examining Nrg1 levels in dementias; however, elevations of CSF Nrg1 have been reported in AD and MCI (Mouton‐Liger et al., 2020; Pankonin et al., 2009).

Synaptosomal‐associated protein 25 (SNAP‐25) is a pre‐synaptic protein involved in vesicular exocytosis, LTP and the formation of SNARE complexes (Noor & Zahid, 2017). In post‐mortem brain studies, levels of SNAP‐25 are reduced across dementia syndromes (Connelly et al., 2011; Minger et al., 2001; Mukaetova‐Ladinska et al., 2009; Sinclair et al., 2015). Levels of CSF SNAP‐25 are increased in AD and MCI (Brinkmalm et al., 2014; Galasko et al., 2019; Wang, Zhou, & Zhang, 2018; Zhang, Therriault, et al., 2018), potentially reflecting the release of SNAP‐25 from synapses into the extracellular space. Elevations have also been reported in PD, Creutzfeldt‐Jakob Disease (CJD) (Noor & Zahid, 2017) and a number of psychiatric disorders; hence, CSF SNAP‐25 could be a general marker of synapse damage (Najera et al., 2019).

Synaptotagmin‐1 is a pre‐synaptic protein involved in synaptic vesicle exocytosis and synaptic transmission (Baker et al., 2015; Jahn & Fasshauer, 2012). Across dementia syndromes, synaptotagmin‐1 levels are reduced in the brain (Bereczki et al., 2018; Davidsson & Blennow, 1998; Yoo et al., 2001) and elevated in the CSF (Öhrfelt et al., 2016, 2019; Tible et al., 2020).

Visinin‐like protein‐1 (VILIP‐1) is a neuronal calcium sensor protein which is widely expressed in neurons and involved in signalling pathways related to synaptic plasticity (Braunewell, 2012). In AD and FTD, VILIP‐1 expression is reduced in the temporal/entorhinal cortices (Braunewell et al., 2001; Kirkwood et al., 2016) and the superior frontal gyrus, respectively (Kirkwood et al., 2016). Additionally, in the CSF, a recent meta‐analysis reported elevated CSF VILIP‐1 levels in AD and MCI due to AD (Dulewicz et al., 2020).

To date, there is no summary of the evidence examining the relationship between CSF markers of synapse loss and neuronal damage and cognition in ageing and disease. Hence, we conducted a systematic review examining the scientific literature for associations between these markers and cognition in healthy ageing and dementia syndromes. We searched for papers examining any type of dementia or cognition in typical ageing to characterise the cross‐diagnostic specificity of markers. Levels of CSF Aβ or tau were not considered as this was beyond the scope of the current review. We searched for correlates of both cross‐sectional cognition only.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

The protocol for this review was prospectively registered on PROPSERO (CRD42020164456).

2.1. Search strategy

The initial search was conducted in December 2019 within MEDLINE, EMBASE and Web of Science. The most recent update search was conducted on 4 January 2021. Search terms can be found in the supporting information Table S1. Reference lists of studies and reviews were manually searched to identify additional studies. No restrictions were applied for language or date of publication. Only published studies in peer reviewed journals were included; conference abstracts were excluded.

2.2. Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria were that the study: (i) included a population with a diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease, MCI, FTD, any other type of dementia or a cognitively unimpaired (CU) sample; (ii) measured a cerebrospinal fluid marker of synapse loss and/or neuronal damage, excluding Aβ or tau; (iii) assessed cognition using a validated tool; and (iv) directly examined the relationship between the CSF marker and cognition.

Exclusion criteria included studies (i) where participants were diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder, (ii) review articles, (iii) conference abstracts, (iv) animal studies and (v) studies which only examined CSF Aβ or tau.

Two researchers (T.S.S. and D.A.G.) independently screened studies for inclusion/exclusion and resolved any discrepancies through discussion.

2.3. Data extraction

T.S.S. and D.A.G. independently extracted data from eligible studies using Covidence software. This included the following: year of publication, demographics, sample size, medication status, apolipoprotein E (ApoE) status, mean/median CSF marker levels with the appropriate measure of variation and other related information. Researchers were not blinded to authors, journals or institutions. Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion and joint data extraction. Authors were contacted for additional clarification and to request missing data wherever possible.

2.4. Risk of bias assessment

The Cochrane network advise against quality scales which generate a summary score and instead suggest placing importance on how each study performed on individual criterion (Boutron et al., 2020). Therefore, we assessed the risk of bias in study design and reporting using the National Institute of Health Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross‐Sectional Studies (National Institutes of Health, 2014). T.S.S. and D.A.G. independently assessed risk of bias, and any discrepancies were resolved by discussion.

2.5. Synthesis of results

Correlation coefficients were selected as the standardised metric of the review. After extraction of results, a meta‐analysis was not conducted due to substantial differences in study methodologies and a lack of reporting of correlation coefficients in published reports. Therefore, we grouped studies according to the CSF marker being measured due to a number of studies pooling participants across diagnostic groups in statistical analysis.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Search results

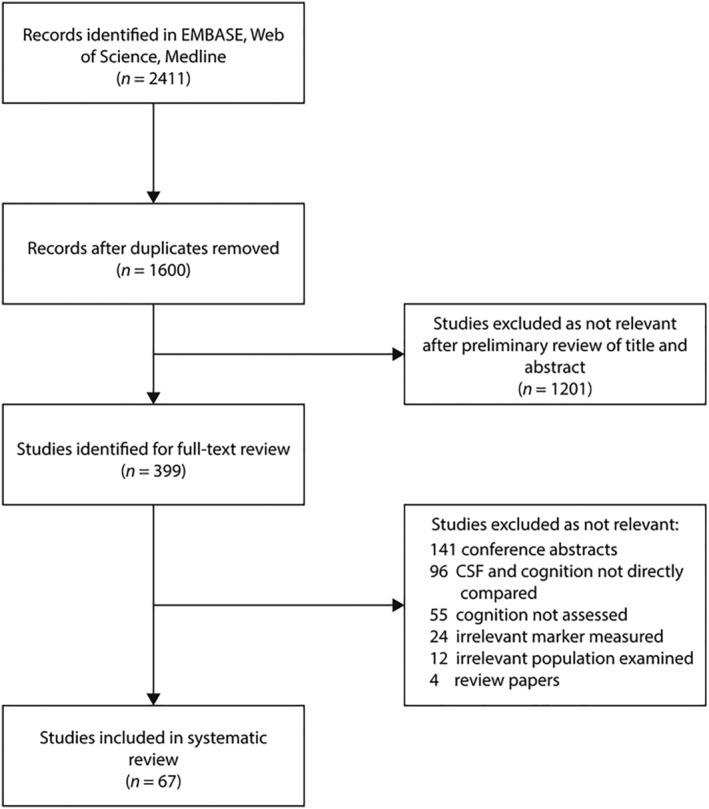

Two thousand, four hundred and eleven studies were identified. After screening studies for eligibility, 67 studies met criteria for inclusion in the systematic review (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Search process

3.2. Study characteristics

3.2.1. Sample size

Characteristics of included studies can be found in Table 1. Some cohorts were used in multiple studies. Ten studies used the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) (Galasko et al., 2019; Headley et al., 2018; Mattsson et al., 2016; Petersen et al., 2010; Portelius et al., 2015; Sun et al., 2016; Swanson et al., 2016; Wang, 2019; Wang, Zhou, & Zhang, 2018; Zetterberg et al., 2016; Zhang, Ng, et al., 2018; Zhang, Therriault, et al., 2018), five used the Amsterdam Dementia Cohort (Boiten et al., 2021; Chatterjee, Del Campo, et al., 2018; Kvartsberg, Duits, et al., 2015; Meeter, Vijverberg, et al., 2018; van Der Flier & Scheltens, 2018; van Steenoven et al., 2020), three used the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer's Prevention (Bendlin et al., 2012; Casaletto et al., 2017; Racine et al., 2016; Sager et al., 2005) and three used the Genetic Frontotemporal Dementia Initiative (GENFI—The Genetic Frontotemporal Initiative) (GENFI – The Genetic Frontotemporal Initiative, n.d.; Meeter et al., 2016; Meeter, Vijverberg, et al., 2018; van der Ende et al., 2020). The Gothenburg Mild Cognitive Impairment Study (Bjerke et al., 2009; Brinkmalm et al., 2014; Rolstad, Berg, et al., 2015; Wallin et al., 2016) was used in three studies, the Mayo Clinic Study of Ageing (Mielke, Syrjanen, Blennow, Zetterberg, Skoog, et al., 2019; Mielke, Syrjanen, Blennow, Zetterberg, Vemuri, et al., 2019; Roberts et al., 2008) in two studies, the Vanderbilt Memory and Ageing Project (Gifford et al., 2018; Jefferson et al., 2016; Osborn et al., 2019) in two studies and finally, the University of California San Diego (UCSD) Shiley‐Marcos Alzheimer's Disease Research Center (Galasko et al., 2019; Xiao et al., 2017) in two studies.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Study | CSF Marker | CSF analysis assay and brand | Population (N) | Age (years) * | Sex (N, % female) | CSF marker level (pg/mL) * : | Cognitive assessment | Adjustment factors | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Abu‐Rumeileh et al., 2018 |

NfL |

ELISA (IBL, Germany) |

AD (60) FTD (141) |

67.1 (8.7) 64.9 (9.8) |

27 (45%) 66 (46.8%) |

Median [IQR] 2160 [1614‐2878] 3293 [2120‐7596] |

BMDB, FAB |

None |

||

| Agnello et al., 2020 |

Ng Alpha‐Synuclein |

ELISA (ADx Neurosciences, Belgium) |

AD (29) |

67.8 (6.4) |

15 (51.7%) |

Median [IQR] |

MMSE |

None |

||

|

Ng: 460 [410‐647] |

α‐syn: 2844[2326.9‐3524.5] |

|||||||||

| Alcolea et al., 2017 | NfL | ELISA (UmanDiagnostics, Sweden) | FTD (249) | 67.12 (8.87) | 121 (48.4%) | 2069.39 (1833.92) | MMSE | None | ||

| Aschenbrenner et al., 2020 | NfL | ELISA (UmanDiagnostics, Sweden) |

CU Aβ + (94) CU Aβ ‐ (161) |

67.31 (8.99) 65.60 (8.47) |

40 (43%) 100 (62%) |

1356.29 (574.42) 1505.72 (703.91) |

Global, episodic memory, attention composites | Age, amyloid status | ||

| Bartos et al., 2012 | NfL | ELISA (Progen, Germany) |

AD (25) PSP, FTD, CJD, CBS, WE (13) |

73 (8) 64 (8) |

21 (84%) 4 (23%) |

N.R | MMSE (derived from ACE‐CZ), ACE‐CZ | None | ||

| Begcevic et al., 2020 |

NPTX1 NPTXR |

Mass spectrometry |

Cohort 1 (58): MCI (8) Mild AD (11) Moderate AD (24) Severe AD (15) Cohort 2 (43): MCI (6) Mild AD (8) Moderate AD (16) Severe AD (15) |

74.5 (7.8) 71.4 (8.4) 75.7 (6.4) 74.4 (9.3) 67.6 (9.2) 76.2 (8.8) 78.1 (6.9) 71.1 (9.0) |

3 (38%) 3 (27%) 13 (54%) 6 (40%) 5 (83%) 3 (38%) 6 (38%) 2 (15%) |

N.R | MMSE | None | ||

| Bendlin et al., 2012 | NfL | ELISA (in‐house) | CU with family history of AD (43) | 53.67 (7.77) | 31 (72.1%) | N.R | BVMT, COWAT, TMT‐A, TMT‐B, WAIS‐working memory index, AVLT | Age, education | ||

| Bjerke et al., 2009 | NfL | ELISA (in‐house) |

MCI‐SVD (9) MCI‐MD (15) MCI‐MCI (118) MCI‐AD (20) CU (52) |

Median {25th, 75th percentile} 68 {66, 74} 69 {65, 74} 62 {57, 68} 68 {58, 72} 66 {63, 70} |

4 (44.4%) 13 (86.7%) 65 (55.1%) 12 (60%) 30 (57.7%) |

Median {25th, 75th percentile} 424 {255, 1414} 250 {250, 406} 250 {250, 250} 250 {250, 341} 250 {250, 250} |

MMSE | None | ||

|

Boiten et al., 2021 |

NPTX2 |

ELISA (in‐house) |

AD (20) DLB (48) |

65.3 (6.0) 67.7 (6.4) |

2 (10%) 6 (13%) |

Median [95% interval] 453 [317‐696] 474 [279 – 659] |

Global, memory, attention, executive function, language, visual composites, MMSE |

Age, education |

||

| Bos et al., 2019 |

NfL Ng |

ELISA (UmanDiagnostics) Electrochemiluminescence (in‐house) |

AD (180) Aβ + (157) Aβ ‐ (23) MCI (450) Aβ + (263) Aβ ‐ (187) CU (140) Aβ + (45) Aβ ‐ (95) |

69.8 (8.8) 74.2 (7.9) 71.4 (7.1) 68.6 (8.2) 69.5 (8.1) 62.7 (7.3) |

85 (54%) 8 (34%) 145 (55%) 89 (48%) 23 (51%) 49 (52%) |

NfL 1742.2 (2893.2) 1931.9 (1934.8) 1242.3 (2556.1) 1031.2 (919.1) 983.13 (678.4) 627.4 (293.3 |

Ng 155.2 (121.4) 118.3 (136) 175.5 (217.8) 99.2 (102.9) 152.6 (149.6) 110.8 (224) |

MMSE | Age, sex, years of education, baseline diagnosis | |

| Brinkmalm et al., 2014 | SNAP‐25 | Mass spectrometry |

AD (36) CU (33) |

Median [IQR] Cohort 1: 68 [68‐79] Cohort 2: 77 [73‐82] Cohort 3: 68 [66‐70] Cohort 1: 70 [68‐74] Cohort 2: 54 [48‐63] Cohort 3: 66 [64‐68] |

Cohort 1: 6 (66.7%) Cohort 2: 7 (70%) Cohort 3: 12 (70.6%) Cohort 1: 7 (77.8%) Cohort 2: 5 (83.3%) Cohort 3: 8 (47.1%) |

N.R. | MMSE | None | ||

| Bruno et al., 2020 |

Ng Alpha‐Synuclein |

ELISA (in‐house) ELISA (Tecan Sunrise, Austria) |

CU (19) | 68.1 (7.3) | 12 (63%) |

Ng: 100.8 (91.4) |

α‐syn: 14.1 (16.1) |

BSRT | None | |

|

Casaletto et al., 2017 |

Ng |

ELISA (in‐house) |

CU with family history of dementia (132) |

64.5 (7.4) |

86 (65.2%) |

Median [IQR] 335.9 [250.6‐482.8] |

AVLT, WAIS‐III symbol digit coding, BNT, WAIS‐III digit span forwards, WAIS‐III digit span backwards. |

Sex CSF Aβ42 CSF t‐tau CSF p‐tau Hippocampal volume ApoE status Family history of AD |

||

|

Chatterjee et al., 2018 |

Contactin‐2 |

ELISA (R&D, USA) |

AD (106) CU (48) |

Cohort 1: 62 (6) Cohort 2: 62 (5) Cohort 1: 60 (7) Cohort 2: 62 (3) |

21 (58.3%) 41 (58 %) 15 (53.6%) 6 (30.6%) |

Median [IQR] 59 [42‐74] 61 [39‐78] 78 [69‐110] 65 [54‐99] |

MMSE |

None |

||

| De Vos et al., 2016 | Ng | ELISA (in‐house) |

AD (50) MCI (38) |

Median {25th, 75th percentile} 75 {68, 78} 73 {69, 79} |

27 (54%) 23 (60.5%) |

Median [IQR] 172 [141‐230] 214 [161‐256] |

MMSE |

Age Sex |

||

| De Jong et al., 2007 | NfL | ELISA (in‐house) |

EAD (37) LAD (33) DLB (18) FTD (28) |

Median [IQR] 61 [52‐69] 76 [69‐90] 72 {58‐90] 63 [43‐79] |

22 (59.4%) 20 (60.6%) 5 (27.8%) 8 (28.6%) |

Median [range] 6.1 [0.0‐40.3] 15.2 [0.0‐70.1] 10.4 [0.0‐60.4] 16.9 [0.0‐76.4] |

MMSE | None | ||

|

Delaby et al., 2020 |

NfL |

ELISA (UmanDiagnostics, Sweden) |

CU (118) AD (116) FTD (56) DLB (37) Prodromal DLB (26) PSP (12) CBS (26) |

59.4 (9.7) 70.4 (8.0) 65.8 (5.2) 76.7 (4.9) 82.2 (6.1) 70.5 (7.8) 72 (7.3) |

68 (57.6%) 71 (61.2%) 15 (26.8%) 19 (51.4%) 13 (50%) 7 (58.3%) 13 (50%) |

Median [IQR] 411 [343‐567] 940 [765‐1229] 1240 [859‐2378] 1135 [803‐1321] 934 [643‐1094] 1422 [1034‐1727] 1637 [923‐2797] |

MMSE |

None |

||

| Dhiman et al., 2020 | NfL | ELISA (UmanDiagnostics, Sweden) |

AD (28) MCI (34) CU (159) |

74.6 (7.5) 74.1 (7.6) 72.8 (5.5) |

12 (43%) 13 (38%) 84 (53%) |

2201 (626.96) 1977 (908.44) 1506 (510.59) |

MMSE |

Age Sex ApoE status |

||

| Galasko et al., 2019 |

Ng (Cohort 1) SNAP‐25 (Cohort 1) NPTX2 (Cohort 1, Cohort 2) |

ELISA (EUROIMMUN, Germany) SIMOA (home‐brew) ELISA (in‐house) |

Cohort 1 (193): AD MCI CU Cohort 2 (292): AD MCI CU |

70.7 (9.4) 74.3 (6.5) 73 (5.2) 75.1 (7.6 74.7 (7.2) 75.7 (5.5) |

19 (41%) 20 (35%) 52 (35%) 28 (42%) 44 (31%) 43 (50%) |

Ng 347.6 (235.6) 332.2 (199.9) 324.5(163.4) |

SNAP‐25 36 (15.6) 34.9(15.5) 32.1( 9.8) |

NPTX2 715.1 (426.6) 826.5 (474.4) 1075 (504.8) 10.3 (0.9) 10.6 (0.7) 10.7 (0.5). |

CVLT |

Age Sex Education ApoE status |

| Gifford et al., 2018 | NfL | ELISA (UmanDiagnostics, Sweden) |

Early MCI (9) MCI (37) CU (65) |

72 (7) 74(7) 73 (7) |

2 (22%) 13 (35%) 20 (31%) |

1145 (477) 1395 (795) 959 (466) |

PVLT | Age, sex, ethnicity, ApoE status, cognitive diagnosis | ||

| Headley et al., 2018 | Ng | Electrochemiluminescence (Meso Scale Discovery, USA) |

MCI (193) CU (111) |

75 (7) 75 (6) |

64 (33%) 55 (50%) |

494 (353) 352 (294) |

MMSE, ADAS‐Cog, ADAS‐Cog13, memory composite, executive function composite | Age, sex, years of education, ApoE status, CSF t‐tau, CSF Aβ42 | ||

| Hellwig et al., 2015 | Ng | Electrochemiluminescenc (Meso Scale Discovery, USA) |

AD (39) MCI‐AD (13) Non‐AD dementia (14) MCI‐O (29) |

Median (range) 72.5 (68‐76) 73.3 (69‐77) 65.1 (59‐71) 69.4 (61‐75) |

21 (53.9%) 8 (61.5%) 8 (57.1%) 14 (48.3%) |

N.R | MMSE | None | ||

| Hoglund et al., 2015 |

NfL Ng VILIP‐1 |

ELISA (UmanDiagnostics, Sweden) Electrochemiluminescence (Meso Scale Discovery, USA) ELISA (BioVendor R&D, Germany) |

CU Aβ‐ (43) CU Aβ+ (86) |

Total: 81.9 (3.4) | Total: 73 (56.6%) |

NfL 1847 (987.2) 1940 (1353) |

Ng 889.3 (414.5) 686.1 (322.8) |

VILIP‐1 0.13 (0.06) 0.12 (0.05) |

MMSE | N.R |

| Jia et al., 2020 |

Ng GAP‐43 SNAP‐25 Synaptotagmin‐1 |

ELISA (American Research Products, USA) ELISA (MyBiosource, USA) ELISA (Proteintech, USA) ELISA (Abbkine, China) |

Cohort 1: AD (28) Cohort 2: AD (73) |

66 (6) 65 (6) |

16 (57.1%) 42 (57.5%) |

N.R | MMSE | Age, sex, ApoE status | ||

| Kirsebom et al., 2018 | Ng | ELISA (EUROIMMUN, Germany) |

Aβ+ MCI (20) Aβ+ SCI (18) CU (36) |

66.8 (7.4) 66.7 (6.8) 61.2 (9.2) |

12 (57%) 8 (44%) 19 (52.8%) |

428 (179) 468 (217) 374 (128) |

MMSE CERAD word list test, TMT‐A, TMT‐B |

Age | ||

| Kvartsberg et al., 2015 | Ng | ELISA (in‐house) |

MCI (40) |

Median [IQR] 64 [58‐71] |

19 (48%) |

Median [IQR] 210 [83‐433] |

MMSE | Age, sex | ||

| Lee et al., 2008 | VILIP‐1 | ELISA (in‐house) |

AD (33) |

Mean ± SE 67.0 ± 1.8 |

18 (55%) |

N.R | MMSE | None | ||

| Lim et al., 2019 | NPTXR | ELISA (RayBiotech, USA) |

MCI (14) Mild AD (21) Moderate AD (43) Severe AD (30) |

72.1 (9.3) 73.7 (8.5) 77.0 (9.0) 72.8 (9.6) |

8 (57%) 6 (29%) 19 (44%) 9 (30%) |

N.R | MMSE | None | ||

| Mattsson et al., 2016 |

NfL Ng |

ELISA (UmanDiagnostics, Sweden) ELISA (in‐house) |

AD MCI CU |

74.7 (8) 74.5 (7.5) 75.7 (5.2) |

41 (44%) 62 (33%) 54 (50%) |

N.R | MMSE, ADAS‐Cog11 | Age, sex, years of education | ||

| McGuire et al., 2015 |

NfL pNfH |

ELISA (UmanDiagnostics, Sweden ELISA (BioVendor,Czech Republic) |

HAD (3) ANI (15) MNCD (15) CU (15) |

Median [IQR] 47 [38‐50] 38 [31‐40] 40 [35‐48] 44 [36‐49] |

0 (0%) 6 (40%) 3 (20%) 3 (20%) |

N.R |

WAIS‐III Digit symbol WAIS‐III Symbol search TMT‐A Story memory test Figure memory test WCST TMT‐B COWAT ANT WAIS‐III letter‐number sequencing PASAT |

None |

||

| Meeter et al., 2016 |

NfL |

ELISA (UmanDiagnostics, Sweden) |

FTD with GRN, MAPT, C9orf72 mutation (101) |

Median [IQR] 59 [56‐65] |

52 (51%) |

6762 (N.R) |

MMSE |

None |

||

|

Meeter et al., 2018 |

NfL |

ELISA (UmanDiagnostics) |

FTD with C9orf72 mutation (64) Presymptomatic carriers of C9orf72 mutation (25) |

Median [IQR] 60 [55‐66] 47 [41‐57] |

29 (45.3%) 17 (68%) |

Median [IQR] 1885 [848‐2841] 429 [336‐830] |

MMSE |

None |

||

|

Meeter et al., 2019 |

NfL |

ELISA (UmanDiagnostics, Sweden) |

svPPA (147) |

Median [IQR] 64 [58‐68] |

87 (54%) |

Median [IQR] 2326 [1628‐3593] |

BNT, ANT, letter fluency, WAIS‐III digit span forward and backwards, TMT‐A, TMT‐B, SCWT, CDT, AVLT, CVLT, CERAD word list test, Rey complex figure test |

Age, sex, laboratory |

||

|

Meeter et al., 2017 |

NfL |

ELISA (UmanDiagnostics) |

bvFTD (164) svPPA (36) nfvPPA (19) lvPPA (4) CBS (40) PSP (58) |

Median [IQR] 61 [55‐67] 62 [58‐65] 62 [52‐66] 64 [51‐69] 65 [60‐73] 66 [62‐70] |

78 (44%) 10 (53%) 10 (53%) 3 (75%) 14 (33%) 36 (56%) |

Median [IQR] 3168 [1752‐4818] 3151[1906=4802] 2345 [1956‐2957] 1731 [1181‐2472] 2664 [1715‐4158] 1907 [1474‐2755] |

MMSE, FAB |

None |

||

|

Mielke et al., 2019a |

NfL Ng |

ELISA (in‐house) ELISA (in‐house) |

Dementia MCI CU Total (777) |

Median [IQR] Total = 72.9 [64‐79.3] |

Total = 334 (43%) |

NfL (total) 520.2 [374.3‐745.4] |

Ng (total) 166.6 [132.9‐220.8] |

Global, Memory, language, attention, visuospatial composites |

Age, sex |

|

|

Mielke et al., 2019b |

NfL |

ELISA (in‐house) |

MCI CU Total (79) |

Median [IQR] Total = 76.4 [71.7‐80.7] |

Total = 27 (34%) |

Median [IQR] Total = 608.3 [429.1‐817.7] * |

Memory, language, executive function, visuospatial composites |

Age, sex, years of education |

||

| Mouton‐Liger et al., 2020 | Nrg1 | ELISA (R&D Systems, USA) |

AD (54) MCI‐AD (20) Non‐AD dementia (30) Non‐AD MCI (31) CU (27) |

69.4 (7.9) 70.2 (8.0) 68.7 (7.6) 61.5 (9.6) 62 (11.3) |

33 (61.1%) 12 (60%) 11 (36.7%) 11 (35.5%) 23 (85.2%) |

364.7 (149.2) 342.6 (161.5) 287.5 (106.5) 304.9 (113.0) 267.7 (104.2) |

MMSE | None | ||

|

Oeckl et al., 2020 |

Beta‐synuclein |

Mass spectrometry |

Cohort 1: AD (64) Cohort 2: AD (40) Cohort 3: AD (49) |

Median [IQR] 73 [68‐78] 70 [63‐74] 72 [64‐77] |

42 (65.6%) 20 (50%) 25 (51.0%) |

Median [IQR] 979 [738‐1223] 694 [532‐990] 917 [746‐1185] |

MMSE |

None |

||

| Öhrfelt et al., 2016 | Synaptotagmin | Mass spectrometry |

Cohort 1: AD (17) Cohort 2: AD (24) Cohort 1: MCI‐AD (5) Cohort 2: MCI‐AD (18) Cohort 1: CU (17) Cohort 2: CU (36) |

Median [IQR] 65 [58‐81] 68 [64‐72] 78 [73‐81] 70 [69‐78] 60 [53‐67] 62 [55‐69] |

12 (70.6%) 17 (70.8%) 4 (80%) 13 (72.2%) 10 (58.8%) 23 (63.9%) |

N.R | MMSE | None | ||

| Öhrfelt et al., 2019 | SNAP‐25 | ELISA (in‐house) |

Cohort 1: AD (17) Cohort 2: AD (24) Cohort 1: MCI‐AD (5) Cohort 2: MCI‐AD (18) Cohort 1: CU (17) Cohort 2: CU (36) |

Median [IQR] 65 [58‐81] 68 [64‐72] 78 [73‐81] 70 [69‐78] 60 [53‐67] 62 [55‐69] |

12 (70.6%) 17 (70.8%) 4 (80%) 13 (72.2%) 10 (58.8%) 23 (63.9%) |

N.R | MMSE | None | ||

| Osborn et al., 2019 | NfL | ELISA (UmanDiagnostics, Sweden) |

Early MCI (27) MCI (132) CU (174) |

73 (6) 73 (8) 72 (7) |

7 (26%) 58 (44%) 71 (41%) |

1088 (465) 1250 (712) 930 (448) |

Episodic memory composite, executive function composite, BNT, ANT, WAIS‐IV coding, DKEFS number sequencing, Hooper visual organisation test | Age, sex, ethnicity, ApoE status | ||

|

Portelius et al., 2015 |

Ng |

Electrochemiluminescence (in‐house) |

AD (95) pMCI (105) sMCI (68) CU (110) |

Median [IQR] 76 [70‐80] 75 [70‐80] 74 [70‐80] 76 [72‐78] |

42 (44%) 37 (35%) 22 (32%) 55 (50%) |

Median [IQR] 485 [349‐744] * 492 [330‐672] * 386 [190‐582] * 304 [161‐453] * |

MMSE, ADAS‐Cog |

Age, sex, education |

||

| Racine et al., 2016 | NfL | ELISA (UmanDiagnostics, Sweden) |

MCI + CU (70) |

66.26 (6.1) |

40 (57.1%) |

N.R |

CAB CPAL errors GMCT moves/sec GML errors GMR errors OCL accuracy ONB accuracy TWOB accuracy RAVLT delayed Logical memory delayed BVMT‐R delayed |

None | ||

| Rojas et al., 2018 | NfL | ELISA (UmanDiagnostics, Sweden) | PSP (50) | 67.7 (5.7) | 30 (60%) | 5929 (6196) |

RBANS Color trails 1 & 2 Letter‐number sequencing, Phonemic fluency |

Age, sex | ||

| Rolstad et al., 2015a | NfL | ELISA (in‐house) |

Dementia‐ vascular (65) Dementia‐ non‐vascular (128) MCI‐ vascular (86) MCI‐ non‐vascular (175) SCI‐ vascular (48) SCI‐ non‐vascular (120) |

68.9 (6.5) 66.4 (7.8) 67.4 (7.2) 63.9 (7.7) 65.6 (7.4) 60.6 (7.1) |

32 (49.2%) 78 (60.9%) 50 (58.1%) 60 (34.3%) 28 (58.3%) 72 (60%) |

567.5 (635.0) 569.4 (720.3) 611.2 (1110.9) 360.7 (299.6) 308.5 (158.2) 328.3 (295.8) |

Attention, learning/memory, visuospatial, language, executive function composites, | Age, sex | ||

| Rolstad et al., 2015b | NfL | ELISA (UmanDiagnostics) | CU (71) | 37.8 (14.6) | 44 (61.9%) | 254.38 (55.42) | Memory , executive function, visuospatial, speed/attention, verbal composites | Age, sex | ||

| Sancesario et al., 2020 | Ng | ELISA (EUROIMMUN, Germany) | CU (30) | 64.04 (11.83) | 18 (61%) | 336.53 (193.40) | MMSE | None | ||

| Sandelius et al., 2019 | GAP‐43 | ELISA (in‐house) |

AD (275) MCI (84) CU (43) FTD (39) DLB (27) lvPPA (10) svPPA (15) PSP (18) CBS (19) |

71.2 (9.2) 72 (8.9) 69 (9.1) |

58.2% 46.4% 69.8% |

N.R | MMSE | None | ||

|

Sanfilippo et al., 2016 |

Ng |

ELISA (in‐house) |

AD (25) MCI (50) MCI‐AD (36) CU (44) |

Median [IQR] 76 [67‐85] 71 [68‐76] 73 [71‐76] 71 [67.5‐75] |

19 (76%) 30 (60%) 22 (61%) 31 (70.5%) |

Median [IQR] 687 [474‐956] * 182 [83‐310] * 481 [326‐841] * 235.5 [171‐358] * |

MMSE, CAMCOG |

None |

||

| Santillo et al., 2019 | Ng | Electrochemiluminescence (Meso Scale Discovery, USA) | CU (20) | 25 (4) | 9 (45%) | 427 (189) | MCCB | None | ||

| Scherling et al., 2014 | NfL | ELISA (UmanDiagnostics, Sweden) |

Asymptomatic FTD mutation carriers (8) bvFTD (45) nfvPPA (18) svPPA (16) CBS (17) AD (50) PSP (22) CU (47) |

54 (10) 61 (8) 70 (7) 63 (7) 68 (8) 66 (9) 68 (7) 66 (11) |

4 (100%) 13 (28.9%) 7 (38.9%) 10 (62.5%) 11 (64.7%) 22 (44%) 11 (50%) 21 (44.7%) |

MMSE, Rey‐Osterrieth figure, FDS, BDS, TMT, Stroop task, BNT, ANT, CVLT, phonemic fluency | None | |||

| Schindler et al., 2019 |

Ng SNAP‐25 VILIP‐1 |

SIMOA (Millipore, USA) SIMOA (Millipore, USA) SIMOA (Millipore, USA) |

Carriers of mutations in PSEN1, PSEN2, or APP (235) Mutation non‐carriers (145) |

38.4 (10.4) 38.8 (12.1) |

127 (54%) 89 (61%) |

Ng 2269 (1189) 1572 (741) |

SNAP‐25 4.6 (1.9) 3.7 (1.3) |

VILIP‐1 173.4 (77.9) 132.9 (50.2) |

DIAN cognitive composite | Age, sex, education, ApoE status |

| Sjögren et al., 2001 | NfL | ELISA (in‐house) |

AD (22) SVD (9) CU (20) |

64.4 (7.7) 70.1 (6.3) 66.4 (9.9) |

7 (31.8%) 9 (100%) 15 (75%) |

569 (308) 1977 (1436) 156 (66) |

MMSE | None | ||

| Sjögren et al., 2000 | NfL | ELISA (in‐house) |

FTD (18) AD (21) |

62.4 (10) 73.4 (3.2) |

7 (38.9%) 14 (66.7%) |

1442 (1183) 1006 (727) |

MMSE | None | ||

| Skillback et al., 2014 | NfL | ELISA (UmanDiagnostics, Sweden) |

EAD (223) AD (1194) FTD (146) DLB (114) VaD (465) MIX (517) PDD (45) Dementia NOS (437) |

59 (4) 76 (6) 68 (9) 73 (7) 76 (8) 78 (7) 70 (8) 74 (9) |

Total = 54.4% |

448 (415) 667 (664) 1220 (1026) 622 (1217) 1059 (1207) 928 (1056) 503 (374) 807 (1237) |

MMSE | Age, sex | ||

| Sun et al., 2016 | Ng | Electrochemiluminescence (Meso Scale Discovery, USA) |

ApoE ε4 carriers: AD (67) MCI (102) CU (27) |

75 (8) 74 (8) 76 (5) |

42 (44%) 64 (33%) 55 (50%) |

N.R | MMSE | None | ||

| Swanson et al., 2016 |

NPTX2 |

Mass spectrometry |

AD (64) MCI (135) CU (86) |

74.98 (7.57) 74.69 (7.35) 75.70 (5.54) |

29 (45.3%) 44 (32.6%) 42 (48.8%) |

Mean ± SE 10.31 ± 0.09 10.62 ± 0.06 10.70 ± 0.08 |

MMSE, ADAS‐Cog, memory composite |

Age, sex, education, ApoE status |

||

| Teitsdottir et al., 2020 | NfL | ELISA (UmanDiagnostics, Sweden) |

AD CSF profile (28) SCI (2) MCI (9) AD (16) DLB (1) Non‐AD CSF profile SCI (10) MCI (13) DLB (1) |

Median (range) 70 (51‐84) 67 (46‐80) |

11 (39.3%) 8 (80%) |

Median (range) 2500 (1200 – 4500) 1900 (900 – 6500) |

Verbal episodic memory composite | Age, education | ||

| Van Der Ende et al., 2020 |

NPTX2 |

ELISA (in‐house) |

Symptomatic genetic FTD (54) Presymptomatic genetic FTD (106) |

Median [IQR] 63 [56‐69] 45 [34‐56] |

22 (40.7%) 59 (55.7%) |

Median [IQR] 643 [301‐872] 1003 [624‐1358] |

MMSE, TMT‐B, phonemic verbal fluency |

Age, sex, years of education, study site |

||

| Van Steenoven et al., 2020 |

NPTX2 NPTXR |

Mass spectrometry Mass spectrometry |

Cohort 1: DLB (20) Cohort 2: DLB (17) Cohort 3: DLB (48) |

65.3 (5.8) 66.9 (7.5) 67.8 (6.3) |

3 (15%) 4 (24%) 6 (12%) |

N.R | MMSE | Cohort | ||

|

Wang et al., 2019 |

Ng |

Electrochemiluminescence (Meso Scale Discovery, USA) |

AD (81) MCI (171) CU (99) |

74.6 (7.8) 74.2 (7.6) 75.5 (5.3) |

37 (45.7%) 58 (33.9%) 49 (49.5%) |

Median [IQR] 471 [347‐675] 455 [267‐657] 324 [191‐468] |

MMSE |

None |

||

| Wang et al., 2018 | SNAP‐25 | ELISA (Erenna, USA) |

AD (16) MCI (75) CU (55) |

73.4 (6.8) 74.3 (6.5) 76 (5) |

10 (62.5%) 21 (28%) 24 (43.6%) |

N.R | MMSE | None | ||

|

Wellington et al., 2016 |

Ng |

Electrochemiluminescence (in‐house) |

AD (100) Genetic AD (2) bvFTD (20) svFTD (21) LBD (13) PSP (46) CU (19) |

Median [IQR] 63 [57‐68] 43, 47 61 [57‐69] 69 [61‐73] 68 [66‐76] 70 [66‐72] 61 [50‐64] |

59 (59%) 2 (100%) 8 (40%) 10 (48%) 2 (15%) 19 (41%) 11 (58%) |

Median [IQR] 463 [275‐669] 252, 1162 150 [120‐317] 244 [138‐426] 120 [120‐304] 188 [120‐302] 196 [120‐297] |

MMSE |

None |

||

|

Xiao et al., 2017 |

NPTX2 |

ELISA (in‐house) |

AD (30) |

Mean ± SE 72.24 ± 10.15 |

16 (53.3%) |

Mean ± SE 716.12 ± 388.22 |

MMSE, DSS, BNT, phonemic verbal fluency, semantic verbal fluency, Wisconsin card sorting task, visual reproduction test, block design, CDT, CVLT |

None |

||

|

Zetterberg et al., 2016 |

NfL |

ELISA (UmanDiagnostics, Sweden) |

AD (95) pMCI (101) sMCI (91) CU (110) |

Median [IQR] 76 [69‐80] 74 [69‐80] 74 [71‐80] |

42 (44.2%) 37 (36.6%) 26 (28.6%) |

Median [IQR] 1479 [1134‐1842] 1336 [1061‐1693] 1182 [923‐1687] |

MMSE, ADAS‐Cog |

Age, sex, education |

||

| Zhang et al., 2018a | VILIP‐1 | ELISA (Erenna, USA) |

AD (18) sMCI (24 pMCI (47) CU (32) |

74.3 (6.79) 76.7 (5.34) 73.1 (6.86) 76 (5.66) |

11 (61.1%) 7 (29.2%) 14 (29.8%) 13 (40.6%) |

189.7 (70.43) 146 (51.93) 184.3 (64.44) 133.0 (37.9) |

MMSE | Age, sex, education | ||

| Zhang et al., 2018b | SNAP‐25 | ELISA (Erenna USA) |

AD (18) sMCI (22) pMCI (47) CU (52) |

74.3 (7) 76 (5.1) 73.1 (6.6) 76.2 (5.1) |

11 (61.1%) 7 (31.8%) 14 (29.8%) 22 (42.3%) |

N.R | MMSE1 | Age, sex, education | ||

Age and CSF levels presented as mean (SD) unless otherwise specified

ACE‐CZ, Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination‐ Czech Version; AD, Alzheimer’s Disease; ADAS‐Cog, Alzheimer Disease Assessment Scale cognitive subscale; ALS, Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis; ANI, Asymptomatic Neurocognitive Impairment; ANT, Animal Naming Test; ApoE, Apolipoprotein E; AVLT, Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test; Aβ‐, Amyloid beta negative; Aβ+, Amyloid beta positive; BMDB, Brief Mental Deterioration Battery; BNT, Boston Naming Test; BSRT, Buschke Selective Reminding Test; bvFTD, Behaviour Variant FTD; BVMT‐R, Brief Visuospatial Memory Test‐ Revised; BVMT, Brief Visuospatial Memory Test; CAMCOG, Cambridge Cognitive Examination; CBS, Corticobasal Syndrome; CDT, Clock Drawing Test; CERAD, Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease; CJD, Creutzfeldt‐Jacob Disease; COWAT, Controlled Oral Word Association Test; CPAL, Continuous Paired Associate Learning; CU, Cognitive unimpaired; CVLT, California Verbal Learning Test; DIAN, Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network; DKEFS, Delis‐Kaplan Executive Function System; DLB, Dementia with Lewy Bodies; DSB, Digit Span Backwards; DSF, Digit Span Forwards; DSS, Digit Symbol Substitution; EAD, Early onset Alzheimer’s Disease; FAB, Frontal Assessment Battery; FTD, Frontotemporal Dementia; GMCT, Groton Maze Times Chase Test; GML, Groton Maze Learning Test; GMR, Groton Maze Learning Test delayed recall; HAD, HIV‐Associated Dementia; lvPPA, logopenic variant Primary Progressive Aphasia; MCCB, MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery; MCI‐AD, Mild Cognitive Impairment due to Alzheimer’s Disease; MCI‐o, Mild Cognitive Impairment not due to Alzheimer’s Disease; MCI, Mild Cognitive Impairment; MIX, Mixed Dementia; MMSE, Mini Mental State Examination; MNCD, Mild Neurocognitive Disorder; MND, Motor Neuron Disease; MSA, Multiple System Atrophy; NfL, Neurofilament‐Light; nfvPPA, non‐fluent variant Primary Progressive Aphasia; Ng, Neurogranin; NOS, Not Otherwise Specified; OCL, One‐Card Learning; ONB, One‐Back Memory; PASAT, Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test; PCA, Posterior Cortical Atrophy; PD, Parkinson’s Disease; PDD, Parkinson’s Disease Dementia; pDLB, Prodromal Dementia with Lewy Bodies; pMCI, progressive MCI; pNfH, Phosphorylated Neurofilament Heavy; PSP, Progressive Supranuclear Palsy; PVLT, Philadelphia Verbal Learning Test; RBANS, Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status; SCWT, Stroop Color Word Test; sMCI, stable MCI; SVD, Small Vessel Disease; svPPA, Semantic Variant Primary Progressive Aphasia; TMT‐ B, Trail Making Test B; TMT‐A, Trail Making Test A; TWOB, Two‐Back Memory; VaD, Vascular Dementia; WAIS, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale; WCST, Wisconsin Card Sorting Test; WE, Wernicke’s Encephalopathy

Sample sizes of included studies ranged from 19 to 770. Only one of the included studies conducted a power analysis (Xiao et al., 2017), although others acknowledged a possible lack of power.

3.2.2. Sociodemographic factors

Participants with AD were aged between 62 and 77 years, those with FTD were aged between 59 and 72 years and MCI participants' age ranged from 62 to 76 years. The age ranges of participants are within the typical range for the detection of dementia/MCI‐related cognitive decline. Those with an ‘other’ form of dementia were aged between 39.5 and 76.7 years. CU participants' age varied widely (between 37.8 and 81.9) due to the nature of the healthy ageing groups; some findings were taken from studies investigating neurodegenerative diseases with age‐matched controls, while few focused solely on CU younger participants. Most studies included a mix of both males and females.

3.2.3. Group status and dementia definitions

As reported in Table 1, 46 studies included participants with AD or MCI, 15 examined those with an FTD‐related syndrome, 39 examined controls or CU samples and 9 studies included those with an ‘other’ dementia. All studies used validated criteria for diagnosing dementia, MCI or identifying the absence of dementia. In AD, most studies used the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS‐ADRDA) (McKhann et al., 1984) criteria to diagnose probable AD and others used the updated National Institute on Ageing/Alzheimer's Association (NIA‐AA) criteria (Jack et al., 2018). One study used The International Working Group 2 (IWG‐2) (Dubois et al., 2014) criteria, and in five, diagnoses were made by clinicians (which were supplemented with CSF marker information in two). To confirm familial AD, one study used autopsy and medical records matched with NINCDS‐ADRDA criteria, while another used autopsy records and the Kawas Dementia Questionnaire (Kawas et al., 1994). Studies with MCI patients used established criteria proposed by the IWG‐2 (Winblad et al., 2004), NIA‐AA criteria (Albert et al., 2011) or criteria proposed by Petersen and colleagues (Petersen, 2004). Two studies used criteria for early MCI proposed by Aisen and colleagues (Aisen et al., 2010) which defines early MCI as a milder episodic memory impairment relative to ‘late MCI’. All FTD studies used established criteria for the relevant subsyndrome, which were appropriate for the time of publication (Armstrong et al., 2013; Gorno‐Tempini et al., 2011; Litvan et al., 1996; Neary et al., 1998; Rascovsky et al., 2011). Most CU studies ruled out dementia or cognitive impairment if participants had a Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) of 0 or did not meet DSM‐III‐R criteria.

3.2.4. Adjustment factors

As seen in Table 1, adjustment factors varied between studies. Thirty‐four studies did not adjust for any covariates. One study conducted a partial correlation and adjusted for multiple cohorts (van Steenoven et al., 2020). Studies using regression techniques most often controlled for age, sex and years of education. Nine studies controlled for ApoE e4 status, and two controlled for ethnicity.

3.2.5. Cognitive assessments

A number of tools were used to assess neuropsychological performance (Table 1). Including composite measures as single tests, there were 37 different cognitive tests analysed across all 67 studies. The most commonly used test was the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) (Folstein et al., 1975), which was employed in 48 studies. The main domains assessed were global cognition, visuospatial abilities, language, attention, general executive functions and memory (working, episodic and semantic).

3.2.6. Risk of bias

Risk of bias ratings is provided in the supporting information Table S2. Twenty studies were rated as ‘Good’, 45 rated as ‘Fair’ and 3 as ‘Poor’.

3.2.7. CSF markers

As reported in Table 1, most studies assayed multiple markers. Thirty‐one studies examined NfL, 22 examined Ng and 24 studies examined a different marker of interest. A description of each marker can be found in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Summary of CSF markers from included studies

| CSF marker | Function | Localization |

|---|---|---|

| Alpha‐Synuclein | Regulation of synaptic vesicle trafficking | Pre‐synaptic |

| Beta‐Synuclein | Unknown | Pre‐synaptic |

| Contactin‐2 |

Axonal guidance Axonal fasciculation |

Pre‐synaptic Axonal |

| GAP‐43 |

Axonal outgrowth Synaptic plasticity |

Pre‐synaptic |

| NfH | Neuronal structure | Axonal |

| NfL | Neuronal structure | Axonal |

| Ng |

Calmodulin‐binding LTP signalling |

Post‐synaptic |

| NPTX1 |

Synaptic plasticity Facilitates excitatory synapse formation |

Pre‐synaptic |

| NPTX2 |

Synaptic plasticity Facilitates excitatory synapse formation |

Pre‐synaptic |

| NPTXR |

Synaptic plasticity Facilitates excitatory synapse formation |

Trans‐synaptic |

| Nrg1 | Synaptic plasticity | Pre‐synaptic |

| SNAP‐25 | SNARE | Pre‐synaptic |

| Synaptotagmin | Calcium sensor | Pre‐synaptic |

| VILIP‐1 | Calcium sensor | Neuronal |

Abbreviations: CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; GAP‐43, growth‐associated protein 43; NfH, neurofilament‐heavy; NfL, neurofilament‐light; Ng, neurogranin; NPTX1, neuronal pentraxin I; NPTX2, neuronal pentraxin 2; NPTXR, neuronal pentraxin receptor; Nrg1, neuregulin‐1; SNAP‐25, synaptosomal‐associated protein 25; VILIP‐1, visinin‐like protein‐1.

A number of immunoassay methods were used to measure CSF analytes. Enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) were the most common immunoassay method, followed by electrochemiluminescence and mass‐spectrometry based methods. Two studies used SIMOA assays. Of the included 67 studies, only 29 reported the intra‐assay coefficient of variability (CV) (Abu‐Rumeileh et al., 2018; Bartos et al., 2011; Bendlin et al., 2012; Bjerke et al., 2009; Brinkmalm et al., 2014; Casaletto et al., 2017; Chatterjee, Del Campo, et al., 2018; Dhiman et al., 2020; Gifford et al., 2018; Hellwig et al., 2015; Hoglund et al., 2017; Kirsebom et al., 2018; Kvartsberg, Duits, et al., 2015; Lim et al., 2019; Meeter et al., 2016; Meeter, Gendron, et al., 2018; Meeter et al., 2019; Meeter, Vijverberg, et al., 2018; Mielke, Syrjanen, Blennow, Zetterberg, Vemuri, et al., 2019; Öhrfelt et al., 2019; Osborn et al., 2019; Rolstad, Jakobsson, et al., 2015; Sandelius et al., 2019; Skillback et al., 2014; Teitsdottir et al., 2020; van der Ende et al., 2020; Wellington et al., 2016; Zetterberg et al., 2016) and only 22 reported inter‐assay CVs (Abu‐Rumeileh et al., 2018; Bartos et al., 2011; Bjerke et al., 2009; Brinkmalm et al., 2014; Chatterjee, Del Campo, et al., 2018; Dhiman et al., 2020; Hellwig et al., 2015; Hoglund et al., 2017; Kvartsberg et al., 2015; Meeter et al., 2016; Meeter, Gendron, et al., 2018; Meeter et al., 2019; Meeter, Vijverberg, et al., 2018; Mielke, Syrjanen, Blennow, Zetterberg, Skoog, et al., 2019; Mielke, Syrjanen, Blennow, Zetterberg, Vemuri, et al., 2019; Mouton‐Liger et al., 2020; Rolstad, Jakobsson, et al., 2015; Sandelius et al., 2019; Singh et al., 2016; Teitsdottir et al., 2020; van der Ende et al., 2020); therefore, the repeatability and technical heterogeneity of results was not reported in the majority of studies.

3.3. Main outcome: Associations between CSF markers and neuropsychological performance

3.3.1. Papers on CSF NfL

In total, 31 studies examined the relationship between CSF NfL levels and neuropsychological performance. All studies analysed CSF NfL using ELISAs.

As reported in Table 3, a significant association between CSF NfL and neuropsychological performance was consistently reported in AD samples. Most studies found significant moderate‐to‐weak relationships with MMSE scores (Abu‐Rumeileh et al., 2018; Bos et al., 2019; Delaby et al., 2020; Sjogren et al., 2000; Skillback et al., 2014; Zetterberg et al., 2016), while others showed no relationship (Bartos et al., 2011; de Jong et al., 2007; Rolstad, Berg, et al., 2015). However, sample sizes were relatively small in two of these studies. Only two studies included early‐onset Alzheimer's (EAD) samples, and both reported no significant associations with MMSE scores (de Jong et al., 2007; Skillback et al., 2014).

TABLE 3.

Summary of results

| Study | CSF marker | Population (N) | Cognitive assessment and direction of relationship ( ‐positive relationship, ‐positive relationship,  ‐ negative, * non‐significant; non‐adjusted results reported where available) ‐ negative, * non‐significant; non‐adjusted results reported where available) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abu‐Rumeileh et al. (2018) | NfL | AD (60) | MMSE |

|

|

FTD (141) |

BMDB |

|

||

| FAB |

|

|||

| MMSE | * | |||

| Agnello et al. (2020) | Ng | AD (29) | MMSE |

|

| Alpha‐synuclein | AD (29) | MMSE | * | |

| Alcolea et al. (2017) | NfL | FTD (249) | MMSE |

|

| Aschenbrenner et al. (2020) | NfL |

CU Aβ + (94) CU Aβ‐ (161) |

Global cognition composite | * |

| Episodic memory composite |

|

|||

| Attention composite | * | |||

| Bartos et al. (2011) | NfL | AD (25) | MMSE (derived from ACE‐CZ) | * |

| ACE‐CZ | * | |||

| PSP, FTD, CJD, CBS, WE (13) | MMSE (derived from ACE‐CZ) | * | ||

| ACE‐CZ | * | |||

| Begcevic et al. (2018) | NPTX1 |

Cohort 1 (58): MCI (8) Mild AD (11) Moderate AD (24) Severe AD (15) |

MMSE | * |

|

Cohort 2 (43): MCI (6) Mild AD (8) Moderate AD (16) Severe AD (15) |

MMSE | * | ||

| NPTXR |

Cohort 1 (58): MCI (8) Mild AD (11) Moderate AD (24) Severe AD (15) |

MMSE | * | |

|

Cohort 2 (43): MCI (6) Mild AD (8) Moderate AD (16) Severe AD (15) |

MMSE | * | ||

| Bendlin et al. (2012) | NfL | CU with family history of AD (43) | BVMT | * |

| COWAT | * | |||

| TMT‐A | * | |||

| TMT‐B | * | |||

| WAIS‐working memory index | * | |||

| AVLT | * | |||

| Bjerke et al. (2009) | NfL |

MCI‐SVD (9) MCI‐MD (15) MCI‐MCI (118) MCI‐AD (20) CU (52) |

MMSE | * |

| Boiten et al. (2021) | NPTX2 | AD (20) | Global composite | * |

| Memory composite | * | |||

| Attention composite | * | |||

| Executive function composite | * | |||

| Language composite | * | |||

| Visuospatial composite | * | |||

| MMSE | * | |||

| DLB (48) | Global composite |

|

||

| Memory composite | * | |||

| Attention composite |

|

|||

| Executive function composite | * | |||

| Language composite | * | |||

| Visuospatial composite | * | |||

| MMSE | * | |||

| Bos et al. (2019) | NfL | Total Aβ + (465) | MMSE |

|

| Total Aβ‐ (305) | * | |||

| AD (180) |

|

|||

| MCI (450) | * | |||

| CU (140) | * | |||

| Ng |

Total Aβ + (465) Total Aβ‐ (305) |

MMSE |

* |

|

| AD (180) |

|

|||

| MCI (450) | * | |||

| CU (140) | * | |||

| Brinkmalm et al. (2014) | SNAP‐25 | AD (36) | MMSE |

|

| CU (33) | MMSE | * | ||

| Bruno et al. (2020) | Alpha‐Synuclein | CU (19) | BSRT | * |

| Ng | CU (19) | BSRT | * | |

| Casaletto et al. (2017) | Ng | CU with family history of dementia (132) | AVLT |

|

| WAIS‐III symbol digit coding |

|

|||

| BNT | * | |||

| WAIS‐III DSF | * | |||

| WAIS‐III DSB | * | |||

| Chatterjee, Del Campo, et al. (2018) | Contactin‐2 | Total sample (154) | MMSE |

|

| AD (106) | MMSE | * | ||

| CU (48) | MMSE | * | ||

| De Vos et al. (2016) | Ng | AD (50) | MMSE | * |

| MCI (38) | MMSE | * | ||

| De de Jong et al. (2007) | NfL | EAD (37) | MMSE | * |

| AD (33) | MMSE | * | ||

| DLB (18) | MMSE | * | ||

| FTD (28) | MMSE | * | ||

| Delaby et al. (2020) | NfL | CU (118) | MMSE |

|

| AD (116) | MMSE |

|

||

| FTD (56) | MMSE |

|

||

| DLB (37) | MMSE | * | ||

| pDLB (26) | MMSE |

|

||

| PSP (12) | MMSE | * | ||

| CBS (26) | MMSE | * | ||

| Dhiman et al. (2020) | NfL |

Total sample (221) AD (28) MCI (34) CU (159) |

MMSE |

|

| Galasko et al. (2019) | Ng | Total AD, MCI, CU (193) |

CVLT immediate recall CVLT delayed recall |

|

| Aβ/tau+ |

CVLT immediate recall CVLT delayed recall |

|

||

| Aβ/tau‐ |

CVLT immediate recall CVLT delayed recall |

|

||

| NPTX2 | Total AD, MCI, CU (193) |

CVLT immediate recall CVLT delayed recall |

|

|

| Aβ/tau+ |

CVLT immediate recall CVLT delayed recall |

|

||

| Aβ/tau‐ |

CVLT immediate recall CVLT delayed recall |

* |

||

| SNAP‐25 | Total AD, MCI, CU (193) |

CVLT immediate recall CVLT delayed recall |

*

|

|

| Aβ/tau+ |

CVLT immediate recall CVLT delayed recall |

*

|

||

| Aβ/tau‐ |

CVLT immediate recall CVLT delayed recall |

* * |

||

| Gifford et al. (2018) | NfL |

Early MCI (9) MCI (37) CU (65) |

PVLT List Total learning |

* |

| Short delay free recall | * | |||

| Short delay cued recall | * | |||

| Long delay free recall | * | |||

| Long delay cued recall |

|

|||

| Discrimination | * | |||

| CU (65) |

PVLT List Total learning |

|

||

| Short delay free recall |

|

|||

| Short delay cued recall |

|

|||

| Long delay free recall |

|

|||

| Long delay cued recall |

|

|||

| Discrimination |

|

|||

| Headley et al. (2018) | Ng |

MCI (193) |

Memory composite |

|

| Executive function composite |

|

|||

| CU (111) | Memory composite | * | ||

| Executive function composite | * | |||

| Total (304) | MMSE |

|

||

| ADAS‐cog |

|

|||

| ADAS‐Cog13 |

|

|||

| Memory composite |

|

|||

| Executive function composite | * | |||

| Hellwig et al. (2015) | Ng | AD + MCI‐AD (53) | MMSE | * |

| Non‐AD dementia + MCI‐o (43) | MMSE | * | ||

| Hoglund et al. (2017) |

NfL |

CU Aβ‐ (43) | MMSE | * |

| CU Aβ + (86) | MMSE | * | ||

| Ng | CU Aβ‐ (43) | MMSE | * | |

| CU Aβ + (86) | MMSE | * | ||

| VILIP‐1 | CU Aβ‐ (43) | MMSE | * | |

| CU Aβ + (86) | MMSE | * | ||

| Jia et al. (2020) | Ng |

Discovery cohort AD (28) |

MMSE |

|

| Validation cohort (73) |

|

|||

| GAP‐43 |

Discovery cohort AD (28) |

MMSE |

|

|

| Validation cohort (73) |

|

|||

| SNAP‐25 |

Discovery cohort AD (28) |

MMSE |

|

|

| Validation cohort (73) |

|

|||

| Synaptotagmin‐1 |

Discovery cohort AD (28) |

MMSE |

|

|

| Validation cohort (73) |

|

|||

| Kirsebom et al. (2018) | Ng |

Aβ + MCI (20) Aβ + SCI (18) CU (36) |

MMSE | * |

| CERAD word list test | * | |||

| TMT‐A | * | |||

| TMT‐B | * | |||

| Kvartsberg, Duits, et al. (2015) | Ng | MCI (40) | MMSE | * |

| Lee et al. (2008) | VILIP‐1 | AD (33) | MMSE |

|

| Lim et al. (2019) | NPTXR |

MCI (14) Mild AD (21) Moderate AD (43) Severe AD (30) |

MMSE |

|

| Mattsson et al. (2016) |

NfL |

Aβ + AD, MCI, CU (262) | MMSE | * |

| ADAS‐Cog11 |

|

|||

| Aβ‐ AD, MCI, CU (127) | MMSE |

|

||

| ADAS‐Cog11 |

|

|||

| Ng | Aβ + AD, MCI, CU (262) | MMSE | * | |

| ADAS‐Cog11 | * | |||

| Aβ‐ AD, MCI, CU (127) | MMSE | * | ||

| ADAS‐Cog11 | * | |||

| McGuire et al. (2015) | NfL |

HAD (3) ANI (15) MNCD (15) CU (15) |

WAIS‐III digit symbol | * |

| WAIS‐III symbol search | * | |||

| TMT‐A | * | |||

| Story memory test | * | |||

| Figure memory test | * | |||

| WCST | * | |||

| TMT‐B | * | |||

| COWAT | * | |||

| ANT | * | |||

| WAIS‐III letter‐number sequencing | * | |||

| PASAT | * | |||

| pNfH |

HAD (3) ANI (15) MNCD (15) CU (15) |

WAIS‐III digit symbol |

|

|

| WAIS‐III symbol search |

|

|||

| TMT‐A |

|

|||

| Story memory test |

|

|||

| Figure memory test |

|

|||

| WCST | * | |||

| TMT‐B | * | |||

| COWAT | * | |||

| ANT | * | |||

| WAIS‐III letter‐number sequencing | * | |||

| PASAT | * | |||

| Meeter et al. (2016) | NfL | FTD with GRN, MAPT, C9orf72 mutation (101) | MMSE | * |

| Meeter, Gendron, et al. (2018) | NfL | FTD with C9orf72 mutation (64) | MMSE |

|

| Presymptomatic carriers of C9orf72 mutation (25) | MMSE | * | ||

| Total (89) | MMSE |

|

||

| Meeter et al. (2019) | NfL | svPPA (147) | BNT |

|

| ANT | * | |||

| Letter fluency | * | |||

| WAIS‐III DSF | * | |||

| WAIS‐III DSB | * | |||

| TMT‐A |

|

|||

| TMT‐B |

|

|||

| SCWT | * | |||

| CDT | * | |||

| AVLT | * | |||

| CVLT | * | |||

| CERAD word list test | * | |||

| Rey complex figure test | * | |||

| Meeter, Vijverberg, et al. (2018) | NfL | bvFTD (164) | MMSE | * |

| FAB |

|

|||

| svPPA (36) | MMSE | * | ||

| FAB | * | |||

| nfvPPA (19) | MMSE | * | ||

| FAB | * | |||

| lvPPA (4) | MMSE | * | ||

| FAB | * | |||

| CBS (40) | MMSE |

|

||

| FAB | * | |||

| PSP (58) | MMSE | * | ||

| FAB | * | |||

| Total sample (including FTD‐MND; | MMSE |

|

||

| FAB |

|

|||

| Mielke, Syrjanen, Blennow, Zetterberg, Skoog, et al. (2019) | NfL |

Dementia (7) MCI (83) |

Global composite | * |

| Memory composite |

|

|||

| Language composite | * | |||

| Attention composite | * | |||

| Visuospatial composite | * | |||

|

CU (687) |

Global composite |

|

||

| Memory composite |

|

|||

| Language composite |

|

|||

| Attention composite |

|

|||

| Visuospatial composite |

|

|||

| Total (777) | Global composite |

|

||

| Memory composite |

|

|||

| Language composite |

|

|||

| Attention composite |

|

|||

| Visuospatial composite |

|

|||

| Ng |

Dementia (7) MCI (83) |

Global composite | * | |

| Memory composite |

|

|||

| Language composite | * | |||

| Attention composite |

|

|||

| Visuospatial composite | * | |||

| CU (687) | Global composite | * | ||

| Memory composite | * | |||

| Language composite | * | |||

| Attention function composite | * | |||

| Visuospatial composite | * | |||

| Total (777) | Global composite |

|

||

| Memory composite |

|

|||

| Language composite |

|

|||

| Attention composite | * | |||

| Visuospatial composite |

|

|||

| Mielke, Syrjanen, Blennow, Zetterberg, Vemuri, et al. (2019) | NfL |

MCI (15) CU (64) Total (79) |

Global composite | * |

| Memory composite | * | |||

| Language composite | * | |||

| Attention composite | * | |||

| Visuospatial composite | * | |||

| Mouton‐Liger et al. (2020) | Nrg1 | AD (54) | MMSE |

|

| MCI‐AD (20) | MMSE |

|

||

|

Total: AD (54) MCI‐AD (20) Non‐AD dementia (30) Non‐AD MCI (31) CU (27) |

MMSE |

|

||

| Oeckl et al. (2020) | Beta‐synuclein | Cohort 1: AD (64) | MMSE |

|

| Cohort 2: AD (40) | MMSE | * | ||

| Cohort 3: AD (49) | MMSE | * | ||

| Öhrfelt et al. (2016) | Synaptotagmin | Cohort 1: AD (17) | MMSE | * |

| Cohort 2: AD (24) | MMSE | * | ||

| Cohort 1: MCI‐AD (5) | MMSE | * | ||

| Cohort 2: MCI‐AD (18) | MMSE | * | ||

| Cohort 1: CU (17) | MMSE | * | ||

| Cohort 2: CU (36) | MMSE | * | ||

| Öhrfelt et al. (2019) | SNAP‐25 | Cohort 1: AD (17) | MMSE | * |

| Cohort 2: AD (24) | MMSE | * | ||

| Cohort 1: MCI‐AD (5) | MMSE | * | ||

| Cohort 2: MCI‐AD (18) | MMSE | * | ||

| Cohort 1: CU (17) | MMSE | * | ||

| Cohort 2: CU (36) | MMSE | * | ||

| Osborn et al. (2019) | NfL |

Early MCI (27) MCI (132) |

Episodic memory composite | * |

| Executive function composite | * | |||

| BNT | * | |||

| ANT |

|

|||

| WAIS‐IV coding | * | |||

| DKEFS number sequencing | * | |||

| Hooper visual organisation test | * | |||

| CU (174) | Episodic memory composite |

|

||

| Executive function composite | * | |||

| BNT | * | |||

| ANT | * | |||

| WAIS‐IV coding | * | |||

| DKEFS number sequencing | * | |||

| Hooper visual organisation test | * | |||

| Total (333) | Episodic memory composite |

|

||

| Executive function composite | * | |||

| BNT | * | |||

| ANT |

|

|||

| WAIS‐IV coding | * | |||

| DKEFS number sequencing | * | |||

| Hooper visual organisation test | * | |||

| Portelius et al. (2015) | Ng | AD (95) | MMSE | * |

| ADAS‐cog | * | |||

|

pMCI (105) |

MMSE | * | ||

| ADAS‐cog | * | |||

|

sMCI (68) |

MMSE | * | ||

| ADAS‐cog | * | |||

| CU (110) | MMSE | * | ||

| ADAS‐cog | * | |||

| Racine et al. (2016) | NfL |

MCI + CU (70) |

CPAL errors‐ visual memory |

|

| GMCT moves/sec ‐speed of visual processing |

|

|||

| GML errors | * | |||

| GMR errors | * | |||

| OCL accuracy | * | |||

| ONB accuracy | * | |||

| TWOB accuracy | * | |||

| AVLT delayed |

|

|||

| Logical memory delayed |

|

|||

| BVMT‐R delayed |

|

|||

| Rojas et al. (2018) | NfL | PSP (50) | RBANS | * |

| Colour trails 1 | * | |||

| Colour trails 2 |

|

|||

| Letter‐number sequencing |

|

|||

| Phonemic fluency | * | |||

| Rolstad, Berg, et al. (2015) | NfL | Dementia‐ vascular (65) | Attention composite | * |

| Learning/memory composite | * | |||

| Visuospatial composite | * | |||

| Language composite | * | |||

| Executive function composite | * | |||

| Dementia‐ non‐vascular (128) | Attention composite | * | ||

| Learning/memory composite | * | |||

| Visuospatial composite | * | |||

| Language composite |

|

|||

| Executive function composite | * | |||

| MCI‐ vascular (86) | Attention composite |

|

||

| Learning/memory composite | * | |||

| Visuospatial composite | * | |||

| Language composite | * | |||

| Executive function composite |

|

|||

| MCI‐ non‐vascular (175) | Attention composite | * | ||

| Learning/memory composite |

|

|||

| Visuospatial composite | * | |||

| Language composite | * | |||

| Executive function composite | * | |||

| SCI‐ vascular (48) | Attention composite |

|

||

| Learning/memory composite | * | |||

| Visuospatial composite |

|

|||

| Language composite | * | |||

| Executive function composite |

|

|||

| SCI‐ non‐vascular (120) | Attention composite | * | ||

| Learning/memory composite | * | |||

| Visuospatial composite | * | |||

| Language composite | * | |||

| Executive function composite | * | |||

| Rolstad, Jakobsson, et al. (2015) | NfL | CU (71) | Memory composite | * |

| Executive functions composite | * | |||

| Visuospatial composite | * | |||

| Attention composite | * | |||

| Verbal functions composite | * | |||

| Sancesario et al. (2020) | Ng | CU (30) | MMSE | * |

| Sandelius et al. (2019) | GAP‐43 | AD (275) | MMSE | * |

| MCI (84) | MMSE | * | ||

| CU (43) | MMSE | * | ||

| FTD (39) | MMSE | * | ||

| DLB (27) | MMSE | * | ||

| lvPPA (10) | MMSE | * | ||

| svPPA (15) | MMSE | * | ||

| PSP (18) | MMSE | * | ||

| CBS (19) | MMSE | * | ||

| Total sample (662; CU, MCI, AD, ALS, FTD, PD, PD‐MCI, PD‐dementia, DLB, lvPPA, svPPA, PSP, CBS, PCA) | MMSE |

|

||

| Sanfilippo et al. (2016) | Ng | AD (25) | MMSE |

|

| CAMCOG | * | |||

| MCI (50) | MMSE | * | ||

| CAMCOG | * | |||

| MCI‐AD (36) | MMSE | * | ||

| CAMCOG | * | |||

| CU (44) | MMSE | * | ||

| CAMCOG | * | |||

| Santillo et al. (2019) | Ng | CU (20) | MCCB | * |

| Scherling et al. (2014) | NfL |

Total: Asymptomatic FTD mutation carriers (8) bvFTD (45) nfvPPA (18) svPPA (16) CBS (17) AD (50) PSP (22) CU (47) |

MMSE | * |

| Rey‐Osterrieth figure | * | |||

| DSF | * | |||

| DSB |

|

|||

| TMT | * | |||

| Stroop colour naming task |

|

|||

| BNT |

|

|||

| ANT |

|

|||

| CVLT |

|

|||

| Phonemic fluency |

|

|||

| bvFTD (45) | MMSE |

|

||

| Rey‐Osterrieth figure | * | |||

| DSF | * | |||

| DSB |

|

|||

| TMT | * | |||

| Stroop colour naming task |

|

|||

| BNT | * | |||

| ANT |

|

|||

| CVLT |

|

|||

| Phonemic fluency |

|

|||

| nfvPPA (18) | MMSE | * | ||

| Rey‐Osterrieth figure | * | |||

| DSF | * | |||

| DSB | * | |||

| TMT | * | |||

| Stroop colour naming task | * | |||

| BNT |

|

|||

| ANT | * | |||

| CVLT | * | |||

| Phonemic fluency | * | |||

| Schindler et al. (2019) | Ng | Carriers of mutations in PSEN1, PSEN2, or APP (235) | DIAN cognitive composite |

|

| Mutation non‐carriers (145) | DIAN cognitive composite | * | ||

| SNAP‐25 | Carriers of mutations in PSEN1, PSEN2, or APP (235) | DIAN cognitive composite |

|

|

| Mutation non‐carriers (145) | DIAN cognitive composite | * | ||

| VILIP‐1 | Carriers of mutations in PSEN1, PSEN2, or APP (235) | DIAN cognitive composite |

|

|

| Mutation non‐carriers (145) | DIAN cognitive composite | * | ||

| Sjogren et al. (2001) | NfL | Insignificant white matter changes (61; AD, SVD, CU) | MMSE |

|

| Extensive white matter changes (14; AD, SVD, CU) | MMSE | * | ||

| Sjogren et al. (2000) | NfL | FTD (18) | MMSE |

|

| AD (21) | MMSE |

|

||

| Skillback et al. (2014) | NfL | EAD (223) | MMSE | * |

| AD (1194) | MMSE |

|

||

| FTD (146) | MMSE | * | ||

| DLB (114) | MMSE | * | ||

| VaD (465) | MMSE | * | ||

| MIX (517) | MMSE |

|

||

| PDD (45) | MMSE | * | ||

| Dementia NOS (437) | MMSE | * | ||

| Total (3103) | MMSE |

|

||

| Sun et al. (2016) | Ng |

ApoE ε4 carriers: AD (67) MCI (102) CU (27) |

MMSE |

|

| Swanson et al. (2016) | NPTX2 |

Total: AD (64) MCI (135) CU (86) |

MMSE |

|

| ADAS‐Cog11 |

|

|||

| Memory composite |

|

|||

| Teitsdottir et al. (2020) | NfL |

AD CSF profile (28): SCI (2) MCI (9) AD (16) DLB (1) |

Verbal episodic memory composite |

|

|

Non‐AD CSF profile (14): SCI (10) MCI (13) DLB (1) |

Verbal episodic memory composite | * | ||

| van der Ende et al., (2020) | NPTX2 |

Symptomatic genetic FTD (54) |

MMSE |

|

| TMT‐B |

|

|||

| Phonemic verbal fluency | * | |||

| Presymptomatic genetic FTD (106) | MMSE | * | ||

| TMT‐B | * | |||

| Phonemic verbal fluency | * | |||

| van Steenoven et al. (2020) | NPTX2 | DLB (85) | MMSE |

|

| NPTXR | DLB (85) | MMSE |

|

|

| Wang (2019) | Ng | AD (81) | MMSE | * |

| MCI (171) | MMSE | * | ||

| CU (99) | MMSE | * | ||

| Total (351) | MMSE |

|

||

| Wang, Zhou, and Zhang (2018) | SNAP‐25 |

AD (16) MCI (75) CU (55) |

MMSE |

|

| Wellington et al. (2016) | Ng | AD (100) | MMSE | * |

| bvFTD (20) | MMSE | * | ||

| svFTD (21) | MMSE | * | ||

| DLB (13) | MMSE | * | ||

| PSP (46) | MMSE | * | ||

| CU (19) | MMSE | * | ||

| Total (including PD, MSA, mood disorders) | MMSE |

|

||

| AD‐like biomarker profile (151) | MMSE | * | ||

| Non‐AD‐like biomarker (109) | MMSE | * | ||

| Xiao et al. (2017) | NPTX2 | AD (30) | MMSE | * |

| DSS |

|

|||

| BNT | * | |||

| Phonemic verbal fluency |

|

|||

| Semantic verbal fluency |

|

|||

| WCST |

|

|||

| Visual reproduction test |

|

|||

| Block design |

|

|||

| CDT | * | |||

| CVLT |

|

|||

| Zetterberg et al. (2016) | NfL | AD (95) | MMSE |

|

| ADAS‐cog |

|

|||

| pMCI (101) | MMSE | * | ||

| ADAS‐cog | * | |||

| sMCI (91) | MMSE | * | ||

| ADAS‐cog |

|

|||

| CU (110) | MMSE | * | ||

| ADAS‐cog | * | |||

| Zhang, Ng, et al. (2018) | VILIP‐1 | Aβ + AD, MCI, CU (83) | MMSE |

|

| Aβ‐ MCI, CU (38) | MMSE | * | ||

| Zhang, Therriault, et al. (2018) | SNAP‐25 | AD (18) | MMSE | * |

| ADAS‐cog | * | |||

| sMCI (22) | MMSE | * | ||

| ADAS‐cog | * | |||

| pMCI (47) | MMSE | * | ||

| ADAS‐cog | * | |||

| CU (52) | MMSE | * | ||

| ADAS‐cog | * | |||