Abstract

The self-assembled skin substitute (SASS) is an autologous bilayered skin substitute designed by our academic laboratory, the Laboratoire d’Organogenèse Expérimentale (LOEX) to offer definitive treatment for patients lacking donor sites (unwounded skin) to cover their burn wounds. This product shows skin-like attributes, such as an autologous dermal and epidermal layer, and is easily manipulable by the surgeon. Its development stems from the need for skin replacement in high total body surface area burned survivors presenting few donor sites for standard split-thickness skin grafting. This review aims to present the history, successes, challenges, and current therapeutic indications of this skin substitute. We review the product’s development history, before discussing current production techniques, as well as clinical use. The progression observed since the initial SASS production technique described in 1999, up to the most recent technique expresses significant advances made in the technical aspect of our product, such as the reduction of the production time. We then explore the efficacy and benefits of SASS over existing skin substitutes and discuss the outcomes of a recent study focusing on the successful treatment of 14 patients. Moreover, an ongoing cross-Canada study is further assessing the product’s safety and efficacy. The limitations and technical challenges of SASS are also discussed.

CURRENT BURN TREATMENTS

Since the 1980s, as intensive care treatment improved and skin substitutes became more readily available, survival after burn injuries significantly increased. Survival rates for very high total body surface area (TBSA) burned (> 65%) often rendered treatment futile in older patients, however recent data suggests that prediction scores are becoming too pessimistic, and that treatment should be offered even for older patients with high TBSA.1 With this increase in survival rate, the need for reconstructive treatment is becoming more urgent.

Permanent coverage can be achieved with either autografts or skin substitutes. Split-thickness skin grafts (STSG, or autograft) remain the best available treatment for low TBSA burn patients, as it eliminates the risk of graft rejection and shows high graft take (95%).2

Although meshed autografts can reach a two- or three-fold expansion ratio, and the Meek technique has a nine-fold expansion ratio, it can be insufficient in patients with a high TBSA.3 Cosmetic outcomes also become a problem when high ratios are used, especially with meshed autografts. Their thin dermal layer increases the risk of contractures impacting joint mobility, limiting pliability and elasticity, or causing discomfort. Some dermal substitutes may be helpful in the healing of burn patients, such as Integra© (Life Science Corp, NJ) and AlloDerm© (Biohorizons, AL). However, they still require autologous epidermal coverage, thus presenting the same limitations when little or no donor sites are available. Other dermal equivalents, such as MatriDerm© (Surgi-One, Canada), provide a native collagen scaffold and elastin that promote cell growth and neovascularization of the burn wound. Alternatively, Novosorb® BTM (PolyNovo, Australia) presents a synthetic matrix that is absorbed within 18 months. This synthetic product is also shelf-stable.

Cultured epithelial autografts (CEA) are an interesting option to provide coverage upon the dermal layer when healthy skin is scarce for STSG. The idea of grafting proliferating epithelial cells to treat patients lacking donor sites were put forward in the 1970s with experiments on animals.4,5 The first use in burn patients was described in 1981 by O’Connor et al.6, who grafted two severely burned patients with cultured epithelia obtained from the patient’s own keratinocytes based on Green et al’s previous work.7 Observation periods of up to 8 months showed reasonable graft take for most of the grafts. It was therefore possible to expand keratinocytes from a small biopsy and graft cultured epidermal cells on burn wounds.

The LOEX began its involvement in burn patient treatment by growing and grafting CEAs in the 1980s.8 However, despite the good level of CEA graft take, major limitations remained, including handling difficulties and low graft take when applied on a site lacking dermis.3 In this context, surgeons have chosen later to mainly graft the CEAs on skin donor sites to stimulate their healing and allow faster re-harvesting. In parallel, some products used today such as RECELL ® (AVITA Medical, CA) allow point-of-care preparation of autologous epidermal suspension that can be used on partial thickness burns. While this treatment can be used to complement meshed autografts, it remains a limited treatment for full-thickness burns.

Alongside the development of CEA, our laboratory developed a new tissue-engineered skin substitute that includes both the dermal and epidermal layers using a novel method that we developed: the self-assembly approach. The objective was to produce a biomimetic skin substitute that resembles native tissue to the highest degree by minimizing the use of exogenous extracellular matrix components and omitting biomaterials altogether. The production of this tissue-engineered skin substitute is based on the cells’ in vitro ability to produce and organize a three-dimensional tissue by a process resembling tissue development in vivo.

IN VITRO ASSAYS

Production

In 1999, Michel et al.9 published the first results that were obtained using the self-assembly approach for the production of human tissue-engineered skin. They successfully obtained a bilamellar skin substitute featuring a dermis with relevant thickness, a completely differentiated epidermis, and integrated pilosebaceous units, all from human origin and without any exogenous material. Briefly, human keratinocytes and fibroblasts were sourced from the skin removed during cosmetic procedures and were enzymatically separated from their extracellular matrix. Fibroblasts were grown for 35 days in the presence of ascorbic acid to form a dermal sheet. The authors chose to superimpose 4 mature sheets and cultured them for an additional week to form a thick dermal layer. Furthermore, hair follicles in anagen phase were inserted in the dermal equivalent, with the addition of another fibroblast sheet to surround the base. This dermis with hair follicles was left to mature for 1 week before seeding keratinocytes on the top layer and culturing for another 8 days. Following this step, the skin substitute was elevated at the air-liquid interface for 21 days to ensure complete epidermal differentiation. Immunostaining against basement membrane and epidermal differentiation markers showed histologically relevant distribution of type IV collagen, type VII collagen, laminin-V, keratin (K) 10, transglutaminase, and filaggrin. Macroscopically, these tissue-engineered constructs showed a skin-mimetic appearance and texture, while being robust enough for easy manipulation. Seventy-eight days were necessary to obtain this fully formed hairy tissue-engineered skin substitute. These new results showed that it was possible to tissue-engineer a skin equivalent that could be used for drug permeation studies, but also eventually find its way into relevant clinical uses because it was possible to produce completely autologous tissue-engineered skin, also called self-assembled skin substitute (SASS). However, some limitations remained in this model, one of them being manufacturing times.

Laplante et al.10 succeeded in shortening the in vitro production time to 56 days by culturing fibroblast sheets for only 28 days and reducing epidermal differentiation time to 14 days. He did not add skin appendages. In addition, there were only 2 superimposed dermal sheets left to adhere to instead of 4, which reduced the work required while maintaining the manipulability of the skin substitute. These parameters are still chosen when these substitutes are used to study pathophysiological phenomena in vitro (Figure 1). Interestingly, the authors’ experiments demonstrated the wound-healing capabilities of this construct by inducing a wound using a punch biopsy and measuring the rate of re-epithelialization. Immunostaining for K1/K10, filaggrin, loricrin, desmosomes, hemidesmosomes, laminin V, and collagen IV was used to follow the migration of keratinocytes and the formation of a dermo-epidermal junction. These results have brought forward a new in vitro, fully human, and reproducible model to analyze the effects of exogenous factors on the rate of re-epithelialization during wound healing. These characteristics eliminated the issues associated with less clinically relevant models using xenogeneic and synthetic matrices in vitro or models exhibiting scabs during wound healing in vivo. It also favored the identification of a new re-epithelialization process allowing faster wound closure.

Figure 1.

Microscopic aspect of tissue-engineered skin. On the left, Masson’s trichrome stain of skin substitutes displaying two distinct layers; a dermis, and a multilayer epidermis including a stratum corneum. On the right, the basement membrane of the skin construct, between the epidermis, and dermis, can be seen in red with laminin-V immunostaining. Nuclei are stained in blue using DAPI. Colors can be seen on the electronic version of the article.

Pouliot et al.11 developed the first protocol used for in vivo assays. Unlike the initial technique of Michel et al.9, the SASS destined for clinical use includes 3 dermal sheets and differentiated epidermis, omitting the hair shafts, and an additional basal fibroblast sheet. The production time was 71 days to obtain a skin substitute exhibiting a completely differentiated epidermis. Their contributions will be discussed in more detail later in this review.

Although the results described above seemed promising, the delay in the production protocol meant that only burn victims requiring a long hospitalization could be grafted with the SASS. Thus, several teams have started working on solutions to shorten production times, while maintaining the great structural stability offered by the self-assembled tissue-engineered skin substitute. One such team was Gauvin et al.12 who focused on the need for epidermal differentiation to maintain tissue integrity. Their results showed that it is imperative to wait for the complete differentiation of keratinocytes and the production of a thick stratum corneum to reduce tissue contraction. The least contracting tissues followed a fibroblast maturation of 28 days, a 3-layer dermal stacking, and a keratinocyte differentiation protocol of at least 10 days which cumulates to a 52-day production time. Additionally, no differences were observed between fibroblast culture methods when comparing the use of small metal weights, a small frame, or a large frame to produce larger substitutes and facilitate tissue manipulation. These results showed that the production of the dermal component remains the step to optimize to reduce the production time.

In the same vein, Beaudoin-Cloutier et al.13 have taken a unique approach to circumvent the clinical limitation imposed by production delays. They chose to pre-produce a fully human non-immunogenic decellularized matrix (DM) that can be seeded with patient fibroblasts and layered with keratinocytes (SASS-DM). By eliminating the matrix production by the autologous fibroblasts, they were able to reduce production time to 24 days. Decellularization was achieved by 2 cycles of osmotic shock, rinsing, dehydration, and DM storage at −20°C. Finally, the DM was thawed, seeded with autologous fibroblasts, and cultured for 7 days before keratinocyte seeding. The epidermal component was produced as previously described by Gauvin et al12. It is important to note that no dermal sheet stacking step was necessary since the DM was initially cultured until the desired final thickness. Histology, mechanical properties and in vivo performance (discussed later) were comparable to tissue-engineered skin substitutes produced using the original method. The simplicity and efficiency of this process make the SASS-DM a suitable alternative to the original SASS production technique and can be considered a skin substitute model relevant to clinical testing. Unfortunately, more in-depth preclinical studies with SASS-DM are required before initiating clinical trials.

In parallel, Larouche et al.14 decided to focus on improving the current production method of the original SASS. Indeed, since each production of SASS is carried out from the cells of a different patient, the production protocol may vary slightly depending on the functional properties of the cells (growth potential, production of extracellular matrix, or contractibility). The current clinical protocol resembles the technique described by the latter. Three new methods (SASS-2, SASS-3 & SASS-4) have been developed to adapt our culture technique to different situations. The dermal component of SASS-2 uses a filter paper frame that is embedded in a 21-day-old fibroblast sheet still attached to the bottom of the plate and folded over the frame. This process is repeated with 3 sheets that are allowed to adhere together for 7 additional days to obtain the desired dermal thickness. Keratinocytes are then seeded on top, cultured submerged for 7 days, and differentiated at the air-liquid interface for 10 days. The production time of the complete SASS-2 is 45 days. SASS-3 uses keratinocytes seeded and left for 4 days on a 17-day-old fibroblast sheet attached to the bottom of a culture plate. The tissue is then folded onto a paper frame, stacked on 2 more 21-day-old fibroblast sheets, and raised at the air-liquid interface for a 10-day epithelial differentiation period. The final production time is 31 days, but significant variance was noted between patients by the investigators. Some keratinocyte populations induced the contraction of unanchored fibroblast sheets, which was problematic. The SASS-4 method overcomes this issue by placing a paper frame in the culture plate before seeding fibroblasts and a dermal maturation lasting 24 to 31 days. Three layers of fibroblast sheets are stacked, the top one seeded with keratinocytes, and differentiated identically to SASS-3. The total production time is between 38 and 45 days. The latter technique is now preferred when producing substitutes for in vitro experiments because it limits tissue contraction and facilitates handling. In vivo assays with grafting of athymic mice showed similar histological, mechanical, and maturation properties between all production techniques, except SASS-2 which had a lower-quality basement membrane. All SASS had successful graft take and matured to a native skin appearance for the duration of the in vivo transplantation experiment (90 days).

Stem Cells

To produce tissue that will remain for the patient’s lifetime, the presence of stem cells is mandatory. Lavoie et al.15 evaluated the importance of the donor site in obtaining the greatest proportion of epithelial stem cells from a patient’s skin biopsy. They compared 3 hairy skin sites (chest, scalp, and peri-auricular) chosen for the presence of hair follicles containing a large amount of epithelial stem cells. Keratin-19 was used to identify epithelial stem cells, and they were isolated with a routine cell extraction. Interestingly, although scalp skin contained almost twice the amount of epithelial stem cells found in in situ peri-auricular skin, the latter showed much better potential for stem cell extraction and subculture results in terms of the number of K-19 positive cells. Thus, the quality of the culture depends on the choice of anatomical site, but also on the ability to successfully extract cells from the biopsies of these sites. Finally, the stem cells were present in the epidermal basal layer of the skin substitute and were not lost during the differentiation step of the epidermis.

Many other results were obtained using the self-assembled tissue-engineered skin model and a list of the articles is made in Table 1.

Table 1.

Evolution of SASS production methods

| Authors | Year | Production time | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Michel et al.9 | 1999 | 78 days | Split-thickness self-assembled bilayered substitute with differentiated epidermis and hair follicle insertions. 4 dermal layers. F+K. Ideal for topical drug permeation studies. |

| Laplante et al.10 | 2001 | 56 days | Shorter individual dermal sheet production time. 3 dermal layers produce a thicker substitute and permit wound reepithelization studies. F+K. No skin appendages. |

| Pouliot et al.11 | 2002 | 50 days/ 71 days | Self-assembled skin substitutes were transplanted on athymic mice before epidermal differentiation or were left to differentiate in vitro for 21 days at the air-liquid interface. Demonstrated that the skin construct is an ideal tissue- engineered skin substitute in preclinical models. |

| Bellemare et al.16 | 2005 | - | This model uses pathological cells (F+K) to accurately modelize scarring mechanisms. This also showed cells with varying fibrotic origins produce tissue-engineered substitutes with different phenotypes. |

| Trottier et al.17 | 2008 | Minimum 56 days | Trilayered skin substitutes were produced from differentiated adipose-derived stem cells (ASC), fibroblasts, and keratinocytes. ASCs were also shown to be an effective substitute for fibroblasts in the skin’s dermal component. F+K+ASCs. |

| Gauvin et al.12 | 2012 | Minimum 42 days | Multiple culture variables were compared. F+K. Tissue-engineered skin surface area did not affect contraction, however, keratinocyte differentiation positively correlated with lower contraction values. |

| Lavoie et al.15 | 2013 | Minimum 45 days | Tissue-engineered skins allow the preservation of stem cells in the basal layer of the epidermis. F+K. |

| Beaudoin-Cloutier et al.10 | 2015 | 31 days | A previously decellularized self-assembled matrix is used as a scaffold for subsequent skin substitute production. F+K. This eliminates the delay of matrix production by autologous fibroblasts before keratinocyte seeding. |

| Morissette-Martin et al.18 | 2015 | 24 days | This method cultured ASCs to form a thick adipocyte sheet bandage to assist normal wound healing mechanisms in vivo. No dermal or epidermal component was included in the reconstructed tissue. |

| Larouche et al.11 | 2016 | 31 days/ 38 days | 3 new methods were developed to produce SASS quicker, with the lengthier version having the advantage of displaying less contraction. Respectively, two are 2 weeks, the other 1 week quicker than the original method. |

| Molina Martins et al.19 | 2020 | 50 days | This experiment established the capability of tissue-engineered skin to respond to UV radiation in a relatively similar manner to native skin, making it a good model for UV-focused skin damage studies. |

| Kawecki et al.20 | 2021 | 41 days | This study examined the morphological differences between a 35cm2 (standard size) and 289cm2 (large size) SASS. Production time was the same, as was histology, contraction, thickness, and grafting. |

ASC, adipose stem/stromal cells; Endo, endothelial cells; F, fibroblasts; K, keratinocytes; SASS, self-assembled skin substitute.

PRECLINICAL ASSAYS

The first in vivo study was made by Pouliot et al.11 in 2002 and was based on the work of Michel et al.9. The production time was roughly 71 days (with keratinocyte differentiation) and 50 days (without keratinocyte differentiation). The authors grafted this model onto athymic mice before any in vitro epidermal differentiation to study its post-graft fate. Shortly after grafting, the skin construct had an epidermis of about 10 to 15 cell layers and the thickness was comparable to native human skin. They showed that the reconstructed human skin, regardless of its origin (adult or newborn), continues to differentiate in vivo, while surviving the graft and retaining its histological properties throughout the duration of the experiment (6 months). Importantly, all relevant dermo-epidermal junction markers were present 21 days after grafting, with distinct lamina densa, and lamina lucida ultrastructures. Finally, the histology was similar in both the in vitro and in vivo models. These preclinical results lay the foundation for future in vitro, preclinical and clinical studies described in this review.

In 2017, Beaudoin-Cloutier et al.13 tested the new SASS-DM production method on athymic mice to compare its efficacy with the original tissue-engineered skin substitute. An impressive production time of around 24 days was achieved, which is comparable to other skin substitute models currently used in certain clinical settings21. This achievement is impressive considering that the SASS-DM presents both a dermal and an epidermal layer while providing effective permanent coverage. Interestingly, this production method is more than 2 times faster than the original method proposed by Pouliot et al.11 15 years prior. Histology, mechanical properties, and epithelial stem-cell retention were also equivalent to the original SASS grafted onto athymic mice. The survival of epithelial stem cells, possibly due to the resilient basement membrane, meant a better longevity of the epidermis and a continuous epidermis renewal. As already mentioned, more in-depth preclinical studies are however necessary before initiating clinical trials.

CLINICAL STUDIES

First Clinical Trial Evaluating the Healing Potential of SASS

The SASS engineered at the LOEX was first introduced in the clinic by Boa et al.22 on patients with venous or mixed leg ulcers refractory to usual compression therapy for more than 6 months. SASSs were simultaneously used both as a dressing and a skin substitute. Indeed, the SASSs made with the patient's cells were applied and replaced every week until complete healing of the chronic ulcerations. Six patients were recruited, each with at least two wounds on one or both lower extremities, for a total of 14 treated wounds. SASSs were applied to a clean wound bed and treatment was repeated weekly until ulcer healed or up to 6-months from the first graft, whichever came first. Some wounds have responded to this treatment in as little as 2 weeks without recurrence. Except for one patient who re-injured himself by falling, all patients healed completely from their venous ulcers within 12 weeks, with an average of 6.7 treatments per ulcer. Recurrences were rare, ranging from 0 to 3 with a total of 4 recurrences for the 14 ulcers. Although limited in its recruitment, the study showed good safety and very promising results for the use of SASS in the treatment of wounds.

Special Access Program

The use of SASS for severe burns was introduced in 2005 under Health Canada’s Special Access Program23. This study, conducted in three intensive burn-care units in the province of Quebec, treated 14 severely burned patients between 2005 and 2014. The patients had full-thickness burns covering over 50% of their bodies. The average age at the time of injury was 34 years old, ranging from 10 to 63 years old. The highest revised Baux score of surviving patients was 160, and the mean was 116. The SASS production time varied between 56 to 71 days for the first graft, a significant limitation when attempting prompt treatment. During surgery, all SASS proved to be as resistant and easy to manipulate as autografts (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Macroscopic aspect of Self-Assembly Skin substitute (SASS) with its transport box.

Graft take for SASS ranged from 85% to 100% with an average of 98%. The smallest TBSA grafted with SASS was 420 cm2 and the highest was 6295 cm2. On the other hand, 6 patients suffered a partial or total loss of autografts before being enrolled in the study. Unfortunately, the percentage of autograft loss was not included in the data. A follow-up of SASS for up to 8.4 years did not show any loss of SASS, proving the permanent nature of this treatment.

For a subset of patients, characteristics of the grafted skin were noted including skin pliability, erythema, melanin index, and skin thickness. For three of the patients, healthy skin was also measured. Shortly after SASSs grafting, some redness could be observed, but this resolved over time. Aesthetic results following SASS grafts were more interesting than autografts (Figure 3), which showed a meshed pattern. SASS graft sites were smooth and of uniform thickness. They also did not show any hypertrophic scarring, movement restriction when applied to joints, or skin tightness. These characteristics were also present in pediatric patients who underwent growth spurts without adverse effects from the SASS grafts that enlarged over time. Two patients showed contractures at the sites grafted with autografts, but not at the sites grafted with SASSs.

Figure 3.

Leg of a burn patient treated with split-thickness skin graft on the upper half of the left leg, and Self-Assembly Skin substitute (SASS) on the bottom half. Photo was taken 5 years post-injury.

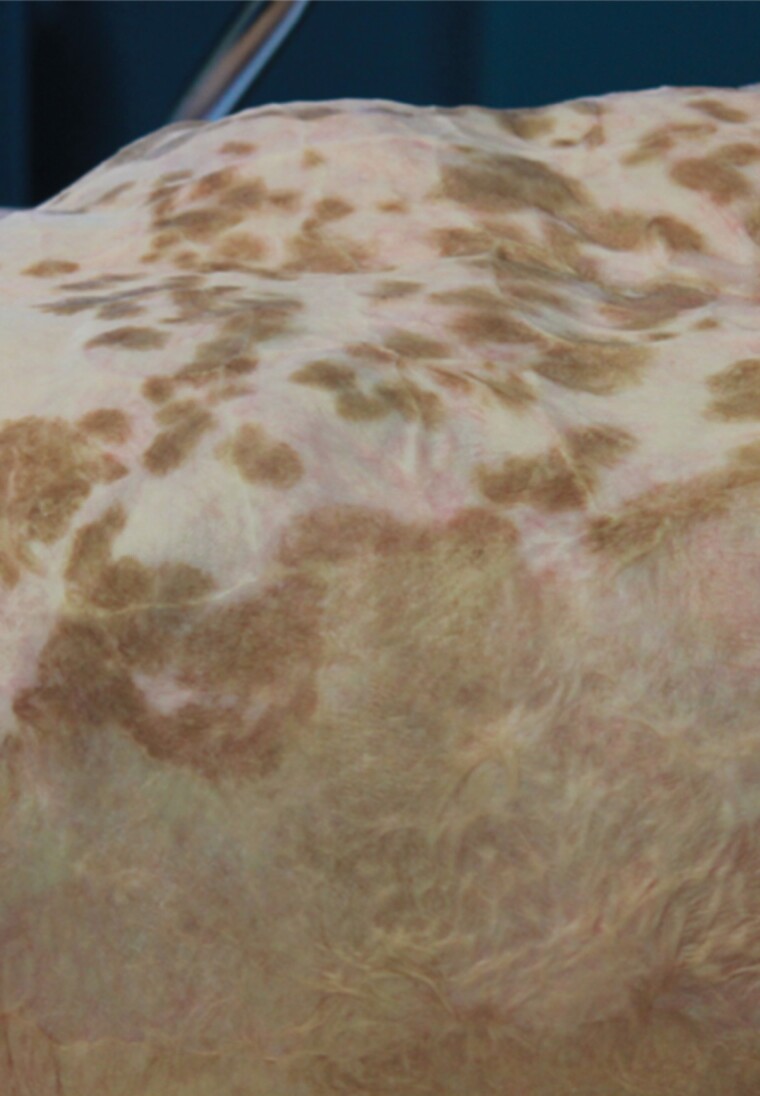

Macroscopic aspects were evaluated in 5 representative patients, approximately 2 weeks after grafting. The site grafted with SASSs showed adherent and uniform skin-like tissue. In some cases, pigmented spots appeared spontaneously after several months and enlarged over time (Figure 4). One patient with a Fitzpatrick skin phototype 4 had larger spots compared to lighter skin phototypes.

Figure 4.

Abdomen of a patient grafted with Self-Assembly Skin substitute (SASS) (upper half) and split-thickness skin graft (lower half). Benign hyperpigmentation spots can be seen on the SASS grafted area.

Nine of the patients described above were the subjects of a single-center retrospective study conducted by Efanov et al.24 independently of the investigators in charge of the SASS production. This study primarily assessed scarring and patient-reported outcomes. The mean follow-up period was 29.5 months. Compared to autografts, patients were more satisfied with the SASS on the household questionnaire created by the investigators. On average, when treated with SASS, functional abilities were near perfect and psychological well-being was moderate. The Vancouver Scar Scale scores were significantly better in SASS-treated sites compared to autografts, SASS grafted sites showing pliability and thickness similar to native skin. The pigmentation and vascularization were between one and two, demonstrating that, with time, the esthetic issues associated with the SASS graft were markedly reduced.

Incisional biopsies confirmed normal healing processes beyond the 1-year follow-up. Another encouraging factor is the absence of proliferative lesions. The mild hyperpigmentation findings in all four patients undergoing biopsy were mildly concerning but did not present any malignant criteria. They warrant further long-term evaluation.

When published in 2018, the evaluation of the patients treated according to the Special Access Program (SAP)23 concluded that SASSs could be an interesting solution for the treatment of severe burns. However, further studies with an exhaustive comparison of results with the autograft method were needed to better assess the efficacy and safety of SASSs.

Ongoing Clinical Trial

There is an ongoing prospective study involving SASSs to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the product. Seventeen patients will be recruited from Canadian burn units and will be evaluated for 36 months following grafting with SASS. A comparison between STSG and SASS as well as quality of life assessments will be performed.

One of the patients included in the aforementioned trial was the subject of a case study.25 An 8-year-old boy suffered an unwitnessed flame burn involving 86% of his TBSA. His scalp and parts of his lower legs were spared. Integra © was used initially but had to be replaced by Novosorb© BTM (PolyNovo, Melbourne, Australia) due to infection. SASS was produced from a 1 × 3 cm biopsy harvested 10 days after the burn. The SASS was received approximately 8 weeks later and grafted onto the BTM 2.5 months post-admission. Seven days after grafting, SASS graft take was 99.5% with few minor open seams and no additional surgery was required. The patient was discharged 10 months after admission without signs of hypertrophic scarring. At the 1-year follow-up, the Vancouver Scar Scale was rated at 2/10, which is consistent with mature scars characteristics.

PERSPECTIVES

Manufacturing Logistics

At this time, early excision is favored in the treatment of severe burns26,27. Time to coverage is an important factor for recovery of function, and early definitive coverage would reduce the need for repeated surgery28. Thus, an effective skin substitute would be histologically similar to native human skin, mechanically strong, non-immunogenic, inexpensive, and readily available. Such an ideal substitute is not available. The SASS described in this review manages to achieve all of the above, except for the issues related to production delays and production costs. Studies have been undertaken to fill the gap, many of them successfully eliminating some nonessential tissue-engineering steps, reducing maturation times, or using previously produced biomimetic extracellular matrices as allogenic natural scaffolds. The SASS intended for clinical use in the case series of Germain et al.23 took an average of 46.2 days to produce. New techniques from Beaudoin-Cloutier et al. and Larouche et al. reduced this period to 31 days in certain cases. These results can be further improved with additional efforts focused on optimizing culture techniques and many studies are underway to propose solutions to this current issue. It should however be noted that these times exclude two steps: the extraction and expansion of cells from the patient biopsy. Adding these times further lengthens the production time for the first graft by approximately 2 weeks.

SASS Size

Although SASS remains an impressive novel therapeutic treatment for severe burns, many patients experience lasting discoloration at the intersection of graft sites. Recently, Kawecki et al.20 studied the potential of increasing the surface area of each reconstructed skin graft to diminish the number of junctions and reduce the aesthetic impact of these discolorations. Their work tested a new 289cm2 L-SASS against the standard 35cm2 SASS in an in vitro model and an in vivo athymic mouse model. Both sizes had a 41-day culture period before being evaluated for tissue contraction, thickness, biological skin markers, cost of production, and graft take. No statistical difference was observed on all of these endpoints, with the exception of production cost. Here, the L-SASS model benefits from significantly reduced labor and material costs. Importantly, L-SASS remains manipulable by the surgical team and shows no hypertrophic scarring or contractures when tested in in vivo preclinical studies.

Skin Pigmentation

Following grafting, an uneven distribution of melanin has been observed in some patients, particularly those with higher Fitzpatrick phototypes. SASS production does not resort to the addition of melanocytes to the model and therefore shows suboptimal results when it comes to matching the patient’s original skin tone. One of the reasons for this omission is the time necessary to produce enough melanocytes (native skin contains 1000–1500 melanocytes/mm2) to produce homogenous and precise pigmentation in the reconstructed skin model. As explained above, the time between a burn and its final coverage deeply influences prognosis. Goyer et al.29 aimed to determine the minimal concentration of melanocytes needed to produce tissue-engineered skin substitutes matching the patient’s phototype and showing an even distribution. Their work established a concentration of 200 evenly distributed melanocytes/mm2 as the minimum quantity of melanin-producing cells necessary to achieve the criteria listed above. They also showed that the melanin produced in these melanocyte-enriched substitutes conferred protection against UV radiation and that their reconstructed skin model had similar histological and surgical attributes to regular SASS. However, the culture conditions require adaptations to be suitable for clinical applications.

Clinical Trials

Current results from the SASS’s Special Access study and clinical trial have revealed very encouraging clinical opportunities. From chronic ulcers to extensively burned patients, this skin substitute shows great versatility and histological attributes. However, these clinical studies suffer from small sample sizes, especially for patients with high Fitzpatrick phototypes, raising the possibility of ethnicity as an aesthetic concern hindering the widespread use of SASSs. It is important to note that to properly assess the safety and efficacy of a therapy, a larger, and more diverse population sample should be reached before establishing the SASS as a therapeutic option to complement the autograft gold standard for the treatment of burn patients.

Additionally, although recent clinical advances address many questions regarding the effectiveness of SASS, knowledge gaps remain, particularly when assessing cost-benefit ratios. These uncertainties continue to be a widespread obstacle to reaching the market for the tissue-engineering industry which suffers from high operating costs. Further economic studies should be conducted with the aim of clearly defining the pathologies and categories of patients who benefit more efficiently from tissue-engineering therapies compared to gold-standard practices.

CONCLUSION

Severe burns remain a clinical dilemma requiring more evidence-based therapies to complement or replace the skin autograft gold standard, a life-saving therapy but associated with scarring complications. Current evidence tends to show that there is a reduction in mortality and morbidity in severely burned patients treated with skin substitutes29. We believe that such treatments could be offered to patients with high TBSA burns or patients lacking donor sites. The current study will focus more on this potential indication for SASS to complement the data obtained from the patients enrolled in the special access program. Production times for skin substitutes vary and are always a limiting factor in such autologous treatments since it relies on the efficiency of cell extraction and amplification, a step dependent on the capacity of the patient cells to proliferate in vitro.30,31

In the literature, short production times of engineered skin (24–26 days) have been achieved in studies using an artificial dermis based on human plasma. This method, however, does not provide the inherent mechanical properties of collagen fibers31, one of the many beneficial attributes present within the SASS. There are currently two commercially available dermo-epidermal skin substitutes: Apligraf© (Organogenesis Inc) and Orcel© (Forticell Bioscience Inc). The former is indicated for diabetic or venous ulcers, and the latter for hand reconstruction and donor sites in burn patients24. They both contain allogeneic neonatal keratinocytes and a bovine collagen matrix and are therefore used as dressings and not as a permanent grafts. Other autologous bilayered skin substitutes have been described and reviewed by Cortez et al.32 Interestingly, SASS is one of the few autologous skin substitutes that provide a niche for stem cells and allow long-term persistence after grafting on burn patients.

The authors of the SASS are actively developing production strategies with the aim of reducing the time from biopsy harvest to grafting. One study described a significant reduction in the production time using a decellularized self-assembled dermal matrix. This strategy uses non-autologous cells to create the dermal matrix, the most time-consuming step, achieving a production time with autologous cells of four and a half weeks. However, the clinical evaluation of this new model remains to be done. Finally, an allogenic version of this SASS would greatly reduce production times, but logistical and immunologic limitations remain to be addressed.

In conclusion, although limited by some logistical and clinical shortcomings, SASS remains a highly innovative, effective, and safe fully human, and autologous skin substitute. It presents itself as a readily available therapy for clinical applications and with all relevant histological and physiological evidence to support its therapeutic claims in severe burns. With a well-advanced clinical trial, support and oversight from federal agencies, and the undeniable benefits offered by the SASS, traditional burn care protocols may soon find themselves in a new era of wound coverage guidelines.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Authors would like to thank all the people (students, especially Emilie Attiogbe for the histology figures, postdoctoral fellows, research staff, collaborators at the LOEX, Drs. Bartha M. Knoppers, Jason Guertin, and their groups on regulatory, economic, legal, and social issues as well as clinical investigators and burn unit staff throughout Canada) who worked on this project as well as grant agencies that provided the essential financial support necessary to achieve the translation from fundamental to clinical research.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate: This study is in accordance with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association for experiments involving humans. Informed consent was obtained from all patients shown in this article.

Authors’ Contributions: Jason Dagher: Writing – original draft, review & editing. Charles Arcand: Writing – original draft, review & editing. François A Auger: Supervision. Lucie Germain: Writing: review & editing. Véronique J Moulin: Writing: review & editing, supervision, project administration.

Funding: Fondation des Pompiers du Québec pour les Grands Brûlés (FPQGB), Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR), Fonds de Recherche du Québec – Santé (FRQS), the Quebec Cell, Tissue and Gene Therapy Network - ThéCell (a thematic network supported by the FRQS), the Stem Cell Network. LG is the holder of the Canada Research Chair on Stem Cells and Tissue Engineering, and the Research Chair on Tissue-Engineered Organs and Translational Medicine of the Fondation de l’Université Laval.

Supplement sponsorship: This article appears as part of the supplement “Skin Regeneration and Wound Healing in Burn Patients: Are We There Yet?,” sponsored by Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals.

Conflict of interest statement. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Jason Dagher, Centre de Recherche en Organogénèse Expérimentale de l’Université Laval (LOEX), Québec, Canada; Centre de Recherche du CHU de Québec-Université Laval, Québec, Canada; Département de chirurgie, Faculté de Médecine, Université Laval, Québec, Canada.

Charles Arcand, Centre de Recherche en Organogénèse Expérimentale de l’Université Laval (LOEX), Québec, Canada; Centre de Recherche du CHU de Québec-Université Laval, Québec, Canada; Département de chirurgie, Faculté de Médecine, Université Laval, Québec, Canada.

François A Auger, Centre de Recherche en Organogénèse Expérimentale de l’Université Laval (LOEX), Québec, Canada; Centre de Recherche du CHU de Québec-Université Laval, Québec, Canada; Département de chirurgie, Faculté de Médecine, Université Laval, Québec, Canada.

Lucie Germain, Centre de Recherche en Organogénèse Expérimentale de l’Université Laval (LOEX), Québec, Canada; Centre de Recherche du CHU de Québec-Université Laval, Québec, Canada; Département de chirurgie, Faculté de Médecine, Université Laval, Québec, Canada.

Véronique J Moulin, Centre de Recherche en Organogénèse Expérimentale de l’Université Laval (LOEX), Québec, Canada; Centre de Recherche du CHU de Québec-Université Laval, Québec, Canada; Département de chirurgie, Faculté de Médecine, Université Laval, Québec, Canada.

REFERENCES

- 1. Roberts G, Lloyd M, Parker Met al. The Baux score is dead. Long live the Baux score: a 27-year retrospective cohort study of mortality at a regional burns service. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2012;72:251–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Archer SB, Henke A, Greenhalgh DG, Warden GD. The use of sheet autografts to cover extensive burns in patients. J Burn Care Rehabil 1998;19:33–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Menon S, Li Z, Harvey JG, Holland AJA. The use of the Meek technique in conjunction with cultured epithelial autograft in the management of major paediatric burns. Burns 2013;39:674–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yuspa SH, Morgan DL, Walker RJ, Bates RR. The growth of fetal mouse skin in cell culture and transplantation to F1 mice. J Invest Dermatol 1970;55:379–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Igel HJ, Freeman AE, Boeckman CRet al. A new method for covering large surface area wounds with autografts: II. surgical application of tissue culture expanded rabbit-skin autografts. Arch Surg 1974;108:724–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. O’Connor N, Mulliken J, Banks-Schlegel Set al. Grafting of burns with cultured epithelium prepared from autologous epidermal cells. Lancet 1981;317:75–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Green H, Kehinde O, Thomas J. Growth of cultured human epidermal cells into multiple epithelia suitable for grafting. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1979;76:5665–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Auger AA. The role of cultured autologous human epithelium in large burn wound treatment. Transplantation 1988;5:21–4. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Michel M, L’Heureux N, Pouliot R, Xu W, Auger FA, Germain L. Characterization of a new tissue-engineered human skin equivalent with hair. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim 1999;35:318–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Laplante A, Germain L, Auger FA, MoulinV.. Mechanisms of wound reepithelialization: hints from a tissue-engineered reconstructed skin to long-standing questions. Faseb J 2001;15:2377–2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pouliot R, Larouche D, Auger FAet al. Reconstructed human skin produced in vitro and grafted on athymic mice. Transplantation 2002;73:1751–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gauvin R, Larouche D, Marcoux H, Guignard R, Auger FA, Germain L. Minimal contraction for tissue-engineered skin substitutes when matured at the air-liquid interface. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 2013;7:452–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Beaudoin Cloutier C, Guignard R, Bernard Get al. Production of a bilayered self-assembled skin substitute using a tissue-engineered acellular dermal matrix. Tissue Eng Part C Methods 2015;21:1297–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Larouche D, Cantin-Warren L, Desgagne Met al. Improved methods to produce tissue-engineered skin substitutes suitable for the permanent closure of full-thickness skin injuries. Biores Open Access 2016;5:320–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lavoie A, Fugere C, Fradette Jet al. Considerations in the choice of a skin donor site for harvesting keratinocytes containing a high proportion of stem cells for culture in vitro. Burns 2011;37:440–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bellemare J, Roberge CJ, Bergeron D, Lopez-Vallé CA, Roy M, Moulin VJ. Epidermis promotes dermal fibrosis: role in the pathogenesis of hypertrophic scars. J Pathol 2005;206:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Trottier V, Marceau-Fortier G, Germain L, Vincent C, Fradette J. IFATS collection: using human adipose-derived stem/stromal cells for the production of new skin substitutes. Stem Cells 2008;26:2713–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Morissette Martin P, Maux A, Laterreur Vet al. Enhancing repair of full-thickness excisional wounds in a murine model: impact of tissue-engineered biological dressings featuring human differentiated adipocytes. Acta Biomater 2015;22:39–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Martins RM, Alves GAD, Martins SSet al. Apple Extract (Malus sp.) and rutin as photochemopreventive agents: evaluation of ultraviolet b-induced alterations on skin biopsies and tissue-engineered skin. Rejuvenation Res 2020;23:465–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kawecki F, Mayrand D, Ayoub Aet al. Biofabrication and preclinical evaluation of a large-sized human self-assembled skin substitute. Biomed Mater 2021;16:025023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sanon, S., Hart D.A., and Tredget E.E., Chapter 2 - Molecular and Cellular Biology of Wound Healing and Skin Regeneration, in Skin Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine, Albanna M.Z. and Holmes Iv J.H., Editors. 2016, Academic Press: Boston. p. 19–47. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Boa O, Cloutier CB, Genest Het al. Prospective study on the treatment of lower-extremity chronic venous and mixed ulcers using tissue-engineered skin substitute made by the self-assembly approach. Adv Skin Wound Care 2013;26:400–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Germain L, Larouche D, Nedelec Bet al. Autologous bilayered self-assembled skin substitutes (SASSs) as permanent grafts: a case series of 14 severely burned patients indicating clinical effectiveness. Eur Cell Mater 2018;36:128–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Efanov JI, Tchiloemba B, Duong Aet al. Use of bilaminar grafts as life-saving interventions for severe burns: a single-center experience. Burns 2018;44:1336–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kelly C, Wallace D, Moulin Vet al. Surviving an extensive burn injury using advanced skin replacement technologies. J Burn Care Res 2021;42:1288–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Xiao-Wu W, Herndon DN, Spies M, Sanford AP, Wolf SE. Effects of delayed wound excision and grafting in severely burned children. Arch Surg 2002;137:1049–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kennedy P, Brammah S, Wills E. Burns, biofilm and a new appraisal of burn wound sepsis. Burns 2010;36:49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Omar MT, Hassan AA. Evaluation of hand function after early excision and skin grafting of burns versus delayed skin grafting: a randomized clinical trial. Burns 2011;37:707–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Goyer B, Pereira U, Magne Bet al. Impact of ultraviolet radiation on dermal and epidermal DNA damage in a human pigmented bilayered skin substitute. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 2019;13:2300–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Boyce ST, Kagan RJ, Greenhalgh DGet al. Cultured skin substitutes reduce requirements for harvesting of skin autograft for closure of excised, full-thickness burns. J Trauma 2006;60:821–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Llames SG, Del Rio M, Larcher Fet al. Human plasma as a dermal scaffold for the generation of a completely autologous bioengineered skin. Transplantation 2004;77:350–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cortez Ghio S, Larouche D, Doucet EJ, Germain L. The role of cultured autologous bilayered skin substitutes as epithelial stem cell niches after grafting: a systematic review of clinical studies. Burns Open 2021;5:56–66. [Google Scholar]