Abstract

Successful parasitism of host cells by intracellular pathogens involves adherence, entry, survival, intracellular replication, and cell-to-cell spread. Our laboratory has been examining the role of early events, adherence and entry, in the pathogenesis of the facultative intracellular pathogen Legionella pneumophila. Currently, the mechanisms used by L. pneumophila to gain access to the intracellular environment are not well understood. We have recently isolated three loci, designated enh1, enh2, and enh3, that are involved in the ability of L. pneumophila to enter host cells. One of the genes present in the enh1 locus, rtxA, is homologous to repeats in structural toxin genes (RTX) found in many bacterial pathogens. RTX proteins from other bacterial species are commonly cytotoxic, and some of them have been shown to bind to β2 integrin receptors. In the current study, we demonstrate that the L. pneumophila rtxA gene is involved in adherence, cytotoxicity, and pore formation in addition to its role in entry. Furthermore, an rtxA mutant does not replicate as well as wild-type L. pneumophila in monocytes and is less virulent in mice. Thus, we conclude that the entry gene rtxA is an important virulence determinant in L. pneumophila and is likely to be critical for the production of Legionnaires' disease in humans.

Legionella pneumophila is an intracellular pathogen that causes Legionnaires' disease in humans, a potentially lethal pneumonia. The ability of L. pneumophila to enter, survive, and replicate in monocytic cells is essential for pathogenesis. Differences in the mechanisms used to enter monocytes correlate with subsequent intracellular survival and replication (13). In addition, it has recently been shown that the bacterial entry mechanism and/or factors expressed very early after entry alter intracellular trafficking (52). L. pneumophila has been shown to enter monocytes by an unusual mechanism, coiling phagocytosis (28), in addition to the conventional phagocytic mechanism observed in most other bacterial species. Although coiling phagocytosis also occurs in spirochetes (12, 47, 48), the bacterial factors and host cell components involved are not known. Complement (31, 40, 45) and antibody (30, 31) opsonization have effects on adherence of L. pneumophila to monocytes. In addition, growth conditions (14) and opsonization with complement (13) or antibodies (28) have been shown to affect the frequencies of coiling and conventional phagocytosis. However, both complement (13) and antibody (28) opsonization results in higher frequencies of conventional phagocytosis. Furthermore, conventional phagocytosis correlates with lower replication rates of L. pneumophila in monocytes (13). These data suggest that further study of the mechanisms of nonopsonic phagocytosis by monocytes is critical to obtaining a better understanding of L. pneumophila pathogenesis.

Our laboratory has recently identified three chromosomal loci, designated enh1, enh2, and enh3, that affect nonopsonic entry of L. pneumophila into monocytes (15). These loci are different from the loci that encode the type IV pilus (58) and major outer membrane protein (38) previously shown to play roles in nonopsonic adherence to and entry into monocytes, respectively. One of the genes present in the enh1 locus, designated rtxA, encodes a “repeats in structural toxin” (RTX). A cytotoxic activity previously observed in L. pneumophila (32) displayed characteristics reminiscent of RTX proteins, including a bacterial surface-associated cytotoxic activity. Since RTX proteins from Bordetella (24) are involved in adherence to host cells and colonization of host epithelium, the rtxA gene is a likely candidate for an L. pneumophila entry gene. RTX proteins from several other species, including Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans (39) and Escherichia coli (8), have the ability to bind specifically to host cells. Adherence of RTX proteins to host cells is thought to be mediated by β2 integrins (1, 39). Since complement receptors are β2 integrins, these data fit well with studies demonstrating that anti-complement receptor antibodies inhibit adherence to and entry into monocytes by L. pneumophila (40, 45), though these studies were done in the presence of complement.

In order to better characterize the role of rtxA in adherence and pathogenesis, we characterized the phenotype of an L. pneumophila strain containing an in-frame deletion in this gene. The resulting mutant strain displayed significantly reduced adherence, cytotoxicity, pore formation, intracellular replication, and virulence in mice compared to wild-type L. pneumophila.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The L. pneumophila strain used for these studies was the streptomycin-resistant variant (43) of L. pneumophila serogroup 1 strain AA100 (20). This strain has been shown to be virulent in both in vitro and in vivo models of infection (43) and was passaged no more than twice in the laboratory before use in these studies. The L. pneumophila rtxA in-frame deletion mutant strain Ψlp24 (ΔrtxA) has been described previously (15). L. pneumophila strains were grown on BCYE agar (19) for 3 days at 37°C in 5% CO2 as described previously (13). The E. coli K-12 strain Ψec47, used for propagation of R6K ori plasmids (XL1-Blue [Stratagene] lysogenized with λpir), was grown in Lennox broth (Difco Laboratories) at 37°C. When necessary, kanamycin (Sigma) was added at a concentration of 25 μg/ml, NaCl was added at 5 mg/ml, and sucrose was added at 50 mg/ml to bacterial growth media.

Cell culture.

HEp-2 cells (ATCC CCL23), established from a human epidermoid carcinoma, were grown in RPMI 1640 plus 5% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (Gibco). THP-1 (ATCC TIB202) and U-937 cells (ATCC CRL1593.2), both human monocytic cell lines, were grown in RPMI 1640 plus 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum. RAW264.7 (ATCC TIB71) and J774A.1 (ATCC TIB67), both murine cell lines, were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium plus 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum.

Molecular techniques and plasmid construction.

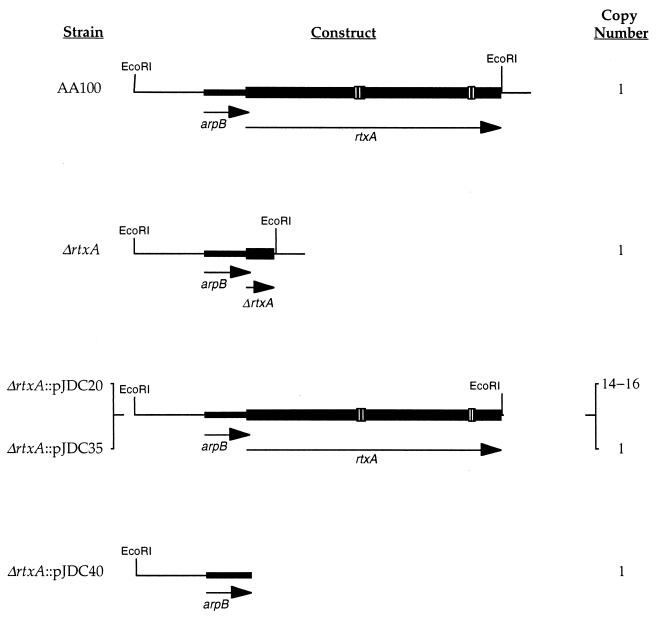

Previous studies in our laboratory demonstrated that the rtxA gene affects entry into epithelial cells (Hep-2) and monocytes (THP-1) (15). In the current study, the wild-type L. pneumophila strain AA100, the ΔrtxA mutant, and complementing strains were examined for other phenotypic characteristics that may help to determine whether rtxA plays a role in virulence. The structure of the in-frame deletion in rtxA and the constructs used for complementation are shown in Fig. 1. Both single-copy and multicopy complementation constructs were used to control for enhanced expression of rtxA due to copy number effects. To ensure physiologically normal RtxA levels for complementation, we expressed rtxA from its endogenous promoter in the same position as it is found in the L. pneumophila chromosome. Since sequence analysis of the rtxA region suggests that the gene is the second in an operon of two genes (15), we utilized complementing constructs that contain the entire operon and putative promoter (pJDC20 and pJDC35). In order to determine whether complementation is solely due to the presence of the rtxA gene on this construct, an identical construct without rtxA was also used (pJDC40). The combination of these constructs allows definitive demonstration of the activity of the rtxA gene under conditions that are as close as possible to those that naturally occur in the L. pneumophila chromosome.

FIG. 1.

Structure of the rtxA region, ΔrtxA mutant, and complementing constructs. All constructs are in single copy in the L. pneumophila chromosome except pJDC20, which is present in the low-copy-number (26) plasmid pYUB289 (3, 15). The ΔrtxA mutant carries an in-frame deletion in the rtxA gene, producing a 130-amino-acid protein product, consisting of 6 amino acids from the amino terminus and 124 amino acids from the carboxy terminus. Gene designations are below the arrows on the constructs illustrating the direction of transcription of the genes. Open boxes in AA100 indicate the positions of the 9-amino-acid repeat sequences characteristic of RTX proteins.

DNA manipulations were carried out essentially as described previously (53). The construction of the ΔrtxA mutant has been described previously (15). The complementation plasmid pJDC20 (Fig. 1) carries the EcoRI fragment that contains only the enh1 locus with rtxA and putative promoter region (15). The L. pneumophila suicide plasmid pJDC35 (Fig. 1) was constructed by insertion of this same EcoRI fragment into the EcoRI site of pJDC15 (15). The L. pneumophila suicide plasmid pJDC40 (Fig. 1) was constructed by digestion of pJDC35 with SwaI and EcoRV followed by self-ligation. Both pJDC35 and pJDC40 were propagated in Ψec47 prior to transformation into L. pneumophila. These plasmids can only be maintained by integration into the L. pneumophila chromosome via homologous recombination. The presence of the appropriate integrated plasmid was confirmed by Southern and PCR analysis of chromosomal DNA from the resulting strains (data not shown) as described previously (15).

Phenotypic characterization of strains.

The presence of pili and flagella on the Δrtx mutant and wild-type L. pneumophila strains was assessed by transmission electron microscopy of negatively stained specimens as described previously (15). Ultrastructural morphology of these strains was examined as described previously (14, 15). Motility was assessed using microscopy (15). Sodium sensitivity was measured by plating dilutions of each strain on BCYE agar and BCYE agar plus 100 mM NaCl and determining colony-forming units (CFU) as described previously (11). The level of sodium sensitivity was expressed as a percentage of the titer in the presence of sodium and compared to that of the wild type. Osmotic sensitivity was measured as described previously (11). Complement sensitivity was examined by incubating 108 CFU of each strain in RPMI containing 50% complete or heat-inactivated human serum for 10 min at 37°C, followed by plating dilutions on BCYE agar to determine CFU. A particular strain was considered sensitive to complement if it displayed a significant decrease in CFU in the presence of complete serum compared to heat-inactivated serum or prior to incubation with serum. Conjugation frequencies were determined essentially as described previously (56) except that pJDC1 (15) was used as the donor plasmid and a naturally arising rifampin-resistant AA100 strain was used as the recipient. Growth rate in laboratory media was determined as described previously (11, 15).

Adherence assays.

Adherence assays were carried out by the immediate assay method described previously (13, 14). HEp-2 cells were seeded in 24-well tissue culture dishes (Falcon) at a concentration of 1.5 × 106 cells/well and allowed to adhere overnight at 37°C. After adding the bacteria, the medium was gently mixed by rocking back and forth, immediately washed five times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove nonadherent bacteria, and then lysed by incubation for 10 min in 1 ml of water followed by vigorous pipetting. Although we tested multiple multiplicities of infection (MOIs) (1, 10, and 100) in these experiments, all data shown are for an MOI of 10. Within this range, the MOI did not significantly affect the data obtained. In the case of THP-1 cells, the assays were carried out in suspension. This requires that the cells be pelleted by centrifugation at 100 × g for 1 min before each change of solution. After lysis, the number of cell-associated bacteria was determined by plating for CFU on BCYE. Adherence assays on formaldehyde-fixed cells (23) were carried out in the same manner except that the cells were fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde for 10 min, washed three times with PBS, and suspended in RPMI prior to addition of the bacteria. For formaldehyde-fixed cells, the bacteria were coincubated with the cells for 30 min (THP-1 cells) or 90 min (Hep-2 cells). Adherence levels were determined by calculating the percentage of the inoculum that became cell associated over the course of the assay [i.e., % adherence = 100 × (CFU cell associated/CFU in inoculum)]. For the wild-type bacterial strain AA100, adherence averaged approximately 0.004% to THP-1 cells and 0.06% to Hep-2 cells under these assay conditions in both formaldehyde-fixed and untreated cells. In order to correct for variation in levels of uptake between experiments, adherence is reported relative to AA100 (i.e., relative adherence = % adherence of test strain/% adherence of AA100).

Intracellular growth assays.

The 48-h growth assays were carried out in a manner similar to that described elsewhere (67). The THP-1 cells used for growth assays were seeded into 24-well tissue culture dishes at 1.5 × 106 cells/well in RPMI plus 10% serum and activated with gamma interferon and lipopolysaccharide (LPS; Difco; E. coli O127:B8) as described previously (13). THP-1 cells treated with gamma interferon and LPS were used in these assays because in our previous studies they were found to be more sensitive to differences in the levels of L. pneumophila virulence than resting monocytes (13). However, activated THP-1 cells were only used for intracellular growth assays because their increased constitutive phagocytic activity makes them a poor choice for use in adherence and entry assays, as illustrated by an increase in the uptake of noninvasive E. coli strain HB101 compared to invasive L. pneumophila strains in adherent monocytic cells (14). For 48-h growth assays, bacteria were added to the cells and incubated at 37°C for 1 h, washed multiple times with warm PBS, and suspended in fresh medium for 48 h before lysis with water. Detailed growth assays were carried out as described previously (13). In these assays the bacteria were incubated with the host cells for 5 min and then treated in the same manner as for the 48-h assays with lysis at various times after washing. Dilutions of the resulting lysates were plated on BCYE agar to determine CFU immediately after the washes and at each time point. All assays were carried out using an MOI of 10. Growth is reported as the mean number of CFU present in triplicate samples at various times divided by the number of CFU present immediately after washing (mean CFU Tx/T0). Under these experimental conditions, AA100 regularly displays between 500 and 1,000 CFU/ml in detailed growth assays and between 10,000 and 50,000 CFU/ml in 48-h growth assays at T0.

Cytotoxicity and pore formation assays.

The standard lactate dehydrogenase release cytotoxicity assay (5, 9) was used in these studies. The procedure used was essentially as recommended by the manufacturer of the CytoTox96 non radioactive cytotoxicity assay system (Promega). Serial dilutions were made of each bacterial strain at MOIs of 500, 250, 100, and 10 in a final volume of 100 μl for each assay using 2 × 104 THP-1 or 2.5 × 103 Hep-2 cells. Appropriate numbers of cells for CytoTox96 assays were determined as suggested by the manufacturer (Promega). The cells were incubated with the bacteria for 4 h at 37°C with 5% CO2. Cytotoxicity readings were taken using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay plate reader at 450 nm. Percent cytotoxicity was calculated as recommended by the manufacturer and corrected for small differences in the inocula used.

Formation of pores in host cells was assayed by ethidium bromide and acridine orange staining exactly as described previously (37, 67) using THP-1, U-937, RAW264.7, J774A.1, and Hep-2 cells. Stained coverslips were examined using a Nikon TE300 inverted microscope with fluorescein isothiocyanate and tetramethyl rhodamine isothiocyanate filters. Dual images of multiple fields were captured using an Optronics charge-coupled device video camera and analyzed as described previously (67). Pore formation is expressed as the percentage of acridine orange-stained cells that also stain with ethidium bromide, resulting from incorporation of this dye into chromosomal DNA due to increased permeability of the host cell. All cells are stained with acridine orange since, unlike ethidium bromide, acridine orange readily crosses the membranes of eukaryotic cells.

Mouse infections and examination for pathology.

In order to examine the virulence of the different L. pneumophila strains in mice, we used methods described previously (6, 10, 13). A/J mice were infected by intratracheal inoculation with 106 bacteria. The mice were harvested 1, 4, 24, and 48 h after infection, and bacteria in the lungs were quantitated as described previously (6, 10, 13). Data represent the mean CFU and standard deviation per gram of lung from 12 mice in each experimental group. All preparations were suspended in PBS prior to inoculation.

Histopathology examination was conducted essentially as described previously (10, 43). Lungs were fixed by immersion in 10% neutral phosphate-buffered formalin, processed routinely, embedded in paraffin, cut at 5 μm, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. L. pneumophila in sections was detected through the use of Warthin-Starry silver stain (36, 43). Each section was assigned a number code to allow blinded examination by light microscopy.

Statistical analyses.

All in vitro experiments were carried out in triplicate and repeated three times. The experiments in vivo were carried out using 12 mice per experimental group. The significance of the results was analyzed using analysis of variance. Values of P of <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

rtxA affects adherence to monocytes and epithelial cells.

The entry mechanism used by L. pneumophila may be the result of interaction of the host cell with the bacteria at the level of adherence, entry, or a combination of these two events. The rtxA gene has previously been shown to have a twofold effect on entry into monocytes (THP-1) and epithelial (HEp-2) cells, but adherence and other phenotypic characteristics potentially related to virulence have not been examined (15). The sodium, osmotic, and complement sensitivity of the ΔrtxA mutant was not significantly different from that of wild-type L. pneumophila (data not shown). Furthermore, there were no differences in the presence of pili, presence of flagella, ultrastructure, conjugation frequency, or motility of the ΔrtxA mutant compared to wild-type bacteria (data not shown). The lack of any other obvious phenotype in vitro suggests that the primary defect in the ΔrtxA mutant is in its ability to enter host cells.

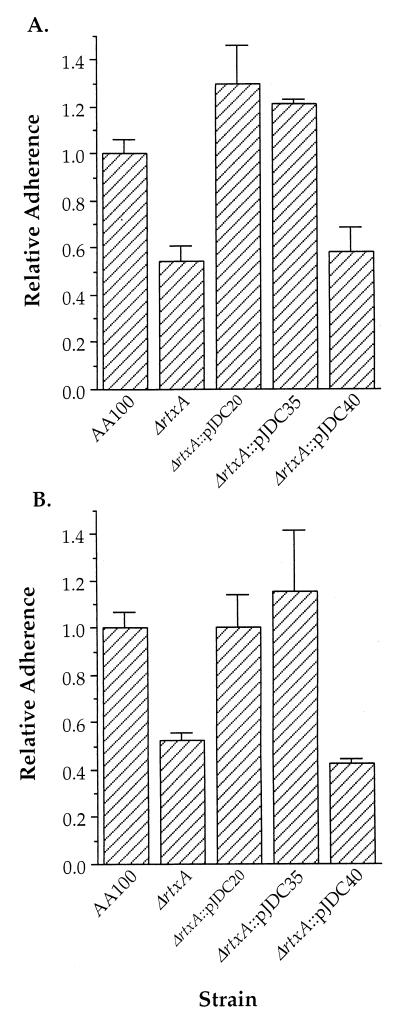

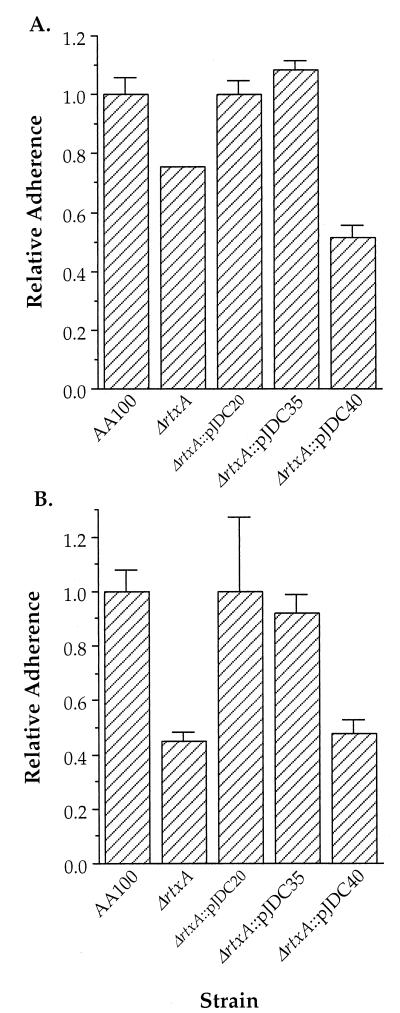

In order to ascertain the role of adherence in rtxA-mediated entry, we examined the adherence of the rtxA mutant to epithelial and monocytic cells (Fig. 2). Adherence to both cell types was reduced by approximately 50% in the rtxA mutant compared to wild-type L. pneumophila. In contrast, levels of adherence similar to wild-type levels were observed in the rtxA mutant carrying a complementing construct containing the complete rtxA gene. However, the rtxA mutation could not be complemented by the same construct containing the putative promoter region and complete arpB gene in the absence of rtxA. All strains were tested for sensitivity to assay conditions such as osmotic lysis, culture medium, and serum. No significant differences were observed between the ΔrtxA and wild-type strains. These data suggests that the rtxA gene is involved in adherence of L. pneumophila to epithelial and monocytic cells.

FIG. 2.

Ability of AA100, the ΔrtxA mutant (ΔrtxA), and complemented clones to adhere to HEp-2 epithelial cells (A) and THP-1 monocytic cells (B). Data points and error bars represent the means of triplicate samples from a representative experiment and their standard deviations, respectively. All experiments were performed at least three times.

Although adherence assays are carried out quickly to prevent the possibility of intracellular killing by the host cell, we initially felt that it was possible that some portion of the difference in adherence observed is due to effects on survival after internalization. In order to test this possibility, we examined the adherence of the rtxA mutant to formaldehyde-fixed epithelial and monocytic cells (Fig. 3), in which internalization cannot occur. Similar differences were observed between the rtxA mutant and wild-type L. pneumophila strains. Both assay methods result in nearly all bacteria remaining extracellular (99.7 to 99.9%), where they are killed by gentamicin (data not shown). Thus, both assay methods are sufficient to allow evaluation of the role of rtxA in adherence, and killing subsequent to uptake does not contribute significantly to the data obtained. This information suggests that the preferred assay for adherence of L. pneumophila would be the immediate assay, since it results in nearly all bacteria remaining extracellular and is unlikely to have aberrant affects on the host cell.

FIG. 3.

Ability of AA100, the ΔrtxA mutant (ΔrtxA), and complemented clones to adhere to formaldehyde-fixed HEp-2 epithelial cells (A) and THP-1 monocytic cells (B). Data points and error bars represent the means of triplicate samples from a representative experiment and their standard deviations, respectively. All experiments were performed at least three times.

rtxA affects cytotoxicity and pore formation caused by L. pneumophila.

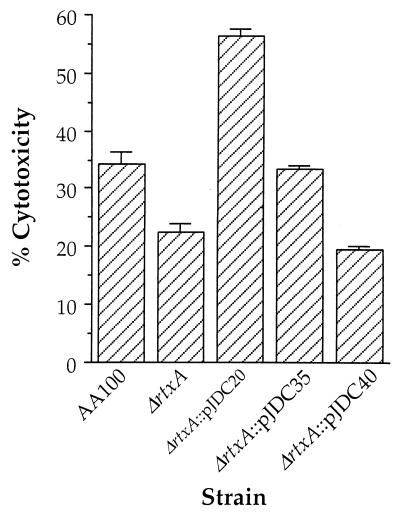

One common characteristic of RTX proteins from other bacterial species is their involvement in pore-forming cytotoxicity for eukaryotic cells (62). Genes involved in pore-forming cytotoxicity have recently been associated with the ability of L. pneumophila to replicate intracellularly (37, 61). Thus, the rtxA gene is a potential mediator of the cytotoxicity and/or pore formation associated with L. pneumophila infection. When we examined the role of rtxA in cytotoxicity, we found that the ΔrtxA mutant displayed less cytotoxicity for monocytic cells than the wild type (Fig. 4). The level of cytotoxicity observed in wild-type L. pneumophila (∼35%) was less than that observed previously (∼65%) using a similar assay (37). These differences are likely due to differences in the cell lines (bone marrow-derived murine macrophages versus THP-1 human monocytes) and bacterial strains (Lp02 versus AA100) used. No cytotoxicity was observed for the epithelial cell line HEp-2 with the wild-type or rtxA mutant strain (data not shown). These data suggest that the cytotoxicity of L. pneumophila is at least somewhat specific for monocytes. However, the fact that rtxA affects cytotoxicity is not necessarily directly related to the pore formation previously observed during L. pneumophila infection of monocytes.

FIG. 4.

Cytotoxicity of AA100, the ΔrtxA mutant (ΔrtxA), and ΔrtxA transformed with pJDC20, pJDC35, and pJDC40 for human monocytic cell line THP-1. Data points and error bars represent the means of triplicate samples from a representative experiment and their standard deviations, respectively. All experiments were performed at least three times.

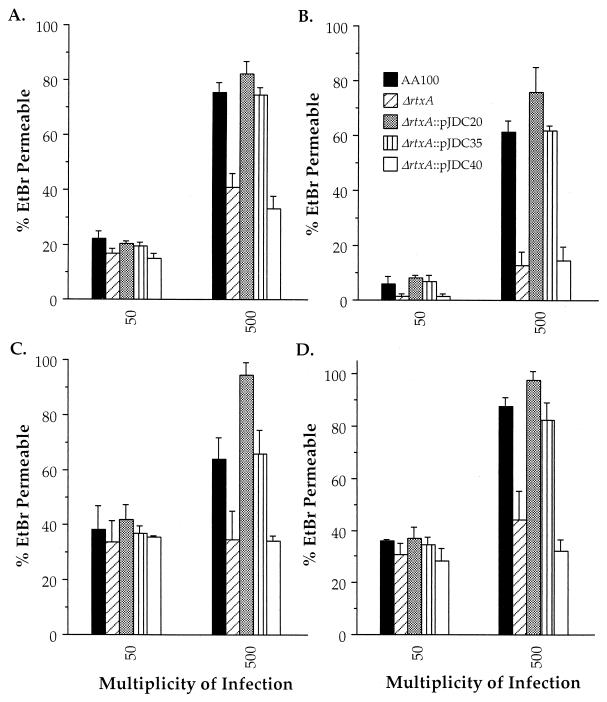

In order to determine the role of rtxA in pore formation, we compared the pore-forming ability of wild-type L. pneumophila with that of the rtxA mutant and complemented clones in four different monocytic cell lines (Fig. 5). We utilized both human and murine cells for these assays to determine whether the pore-forming activity was species specific, as is sometimes observed with RTX proteins from other bacterial species (4, 25, 50, 57, 59, 60). Our data indicate that rtxA is involved in a pore-forming activity that occurs in both murine and human monocytes. Although the level of pore formation varies in different cell types, pore formation is consistently reduced in the rtxA mutant compared to the wild type and correlates with increased bacteria-per-cell ratios. The smallest difference is observed in RAW264.7 cells, a mouse macrophage cell line, though this difference is still significant (P = 0.043). No pore formation was observed in HEp-2 cells with wild-type L. pneumophila or the rtxA mutant (data not shown). These data indicate that the L. pneumophila rtxA gene is involved in a cytotoxic and pore-forming activity affecting both human and murine monocytic cells but not HEp-2 cells.

FIG. 5.

Pore formation by AA100, the ΔrtxA mutant (ΔrtxA), and ΔrtxA transformed with pJDC20, pJDC35, and pJDC40 for THP-1 (A), U-937 (B), RAW264.7 (C), and J774.1 (D) cells. Data points and error bars represent the means of triplicate samples from a representative experiment and their standard deviations, respectively. All experiments were performed at least three times. EtBr, ethidium bromide.

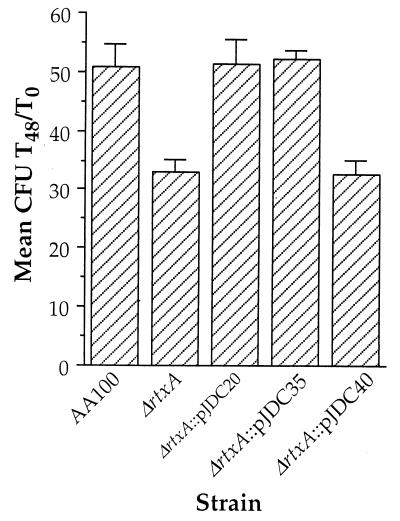

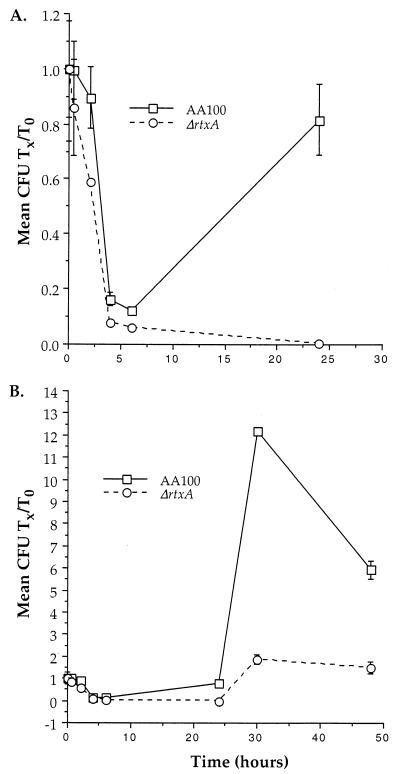

Optimal intracellular survival and replication require rtxA.

Since pore formation is thought to be involved in the intracellular survival of L. pneumophila (37, 61), the activities that are associated with rtxA may also affect intracellular viability. In order to elucidate whether rtxA plays an important role early during intracellular infection, we compared the ability of the ΔrtxA mutant to survive and replicate in monocytes. Although the ΔrtxA mutant replicates like the wild type in BYE broth (data not shown), growth in monocytes is significantly lower during the first 48 h of growth (Fig. 6). In order to examine the intracellular viability of L. pneumophila at very early time points during intracellular growth, we used a 5-min coincubation with host cells. This procedure allowed detailed examination of the kinetics of intracellular growth from 5 min to 48 h (Fig. 7). These data demonstrate that the ΔrtxA mutant appears to be killed more efficiently in monocytes during the first 2.5 h after uptake. The apparent difference between the fold increase observed in Fig. 6 and 7 is due to the different time zero used (1 h as opposed to 5 min) along with the rapid intracellular killing observed at early time points during intracellular growth. Taking these two factors into consideration, the data are consistent with AA100 increasing from approximately 0.1 to 6 (60-fold) and ΔrtxA increasing from approximately 0.05 to 2 (40-fold) over 48 h. The early intracellular killing of the ΔrtxA mutant suggests that the effects of rtxA on entry affect intracellular viability. This early defect in intracellular survival leads to continuously lower intracellular replication, even at time points as late as 48 h.

FIG. 6.

Growth of AA100, the ΔrtxA mutant (ΔrtxA), and ΔrtxA transformed with pJDC20, pJDC35, and pJDC40 in THP-1 cells over 48 h. Data points and error bars represent the mean number of CFU present at 48 h/number of CFU present at time zero (mean CFU Tx/T0) of triplicate samples from a representative experiment and their standard deviations, respectively. All experiments were performed at least three times.

FIG. 7.

Growth of AA100 and the ΔrtxA mutant (ΔrtxA) in THP-1 monocytic cells during the first 24 (A) and 48 (B) h after entry. Data points and error bars represent the means of triplicate samples from a representative experiment and their standard deviations, respectively. Many of the error bars are not visible because they overlap the symbols. All experiments were performed at least three times.

rtxA affects virulence.

Since the differences between the ΔrtxA and wild-type strains are relatively small in these in vitro assays, we wished to determine whether these small differences in phenotype significantly affect the ability of L. pneumophila to cause disease. In order to elucidate whether the phenotypic effects observed in vitro correlate with changes in virulence, we compared the ability of the wild-type, ΔrtxA mutant, and complemented strains to infect mice (Table 1). Although the initial of bacteria found in the lung 1 h after infection is similar for all strains, the CFU for the ΔrtxA mutant decrease over time. By 24 h after infection, there is a 10-fold difference in CFU between the ΔrtxA mutant and the wild type, whereas there was no significant difference between the single-copy complemented strain (ΔrtxA::pJDC35) and the wild type at any time point. This corresponds well with our observation that the ΔrtxA mutant displays reduced intracellular survival in monocytes. Interestingly, the CFU for the ΔrtxA mutant containing the multicopy plasmid pJDC20 increase more quickly than for the wild type, suggesting that the increased copy number of this region enhances the ability of L. pneumophila to survive and/or replicate in mouse lungs.

TABLE 1.

Replication of L. pneumophila in lungs after intratracheal inoculationa

| Time after infection (h) | Mean bacteria (CFU/g of lung) ± SD

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA100 | ΔrtxA | ΔrtxA::pJDC20 | ΔrtxA::pJDC35 | ΔrtxA::pJDC40 | |

| 1 | 4.1 (± 0.3) × 104 | 4.9 (± 0.3) × 104 | 8.4 (± 0.2) × 104 | 2.4 (± 0.3) × 104 | 3.5 (± 0.2) × 104 |

| 4 | 6.5 (± 0.3) × 104 | 6.1 (± 0.2) × 104 | 1.9 (± 0.2) × 105* | 5.9 (± 0.3) × 104 | 3.1 (± 0.2) × 104 |

| 24 | 8.3 (± 0.4) × 104 | 5.8 (± 0.3) × 103* | 2.6 (± 0.4) × 106* | 6.4 (± 0.3) × 104 | 8.4 (± 0.3) × 103* |

| 48 | 1.9 (± 0.2) × 105 | 1.6 (± 0.2) × 102* | 1.2 (± 0.3) × 107* | 8.1 (± 0.3) × 104 | 1.2 (± 0.4) × 103* |

An inoculum of 106 bacteria was used for all experimental groups. Data represent the means ± standard deviations of duplicate platings from 12 mice. ∗, significantly different (P < 0.05) from wild-type L. pneumophila (AA100).

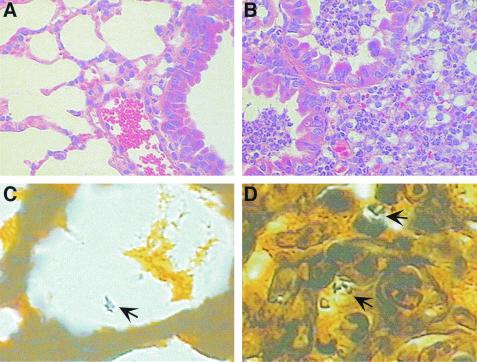

Throughout the course of these experiments, the animals were monitored for signs of disease. At 1 h after infection, no mice displayed any adverse symptoms. However, by 48 h all of the mice infected with the wild type (AA100) and ΔrtxA::pJDC20 mutant and the majority of the mice infected with the ΔrtxA::pJDC35 mutant displayed malaise and ruffled fur, whereas only one mouse infected with the ΔrtxA mutant showed malaise. Histopathologic examination of lungs from mice infected with these strains (Fig. 8) confirmed the disease state of the mice in each group and showed characteristics similar to those found in previous studies on L. pneumophila infections in mice (10). Lung tissue from mice infected with wild-type AA100, ΔrtxA::pJDC20, and ΔrtxA::pJDC35 strains displayed lesions consisting of lobular areas of parenchymal consolidation characterized by severe suppurative inflammation together with peribronchial and perivascular interstitial edema. Infiltration by mixed inflammatory cells, primarily polymorphonuclear neutrophils, was also observed. Large clusters of leukocytic exudate mixed with necrotic cellular debris and red blood cells are present in bronchiolar lumena and extend to the surrounding alveolar air spaces. However, the respiratory mucosa remain intact. Silver stain sections from mice infected with the wild-type strain display small clusters of apparently intracellular rod-shaped organisms in mononuclear inflammatory cells present within affected alveolar lumena (Fig. 8). In contrast, lung tissues from mice infected with the ΔrtxA and ΔrtxA::pJDC40 mutant are negative for lesions, and bacteria are often extracellular and less abundant throughout the sections. These data indicate that the rtxA gene is a key virulence determinant and that the mechanism of entry used is likely to be critical to L. pneumophila pathogenesis.

FIG. 8.

Histopathologic examination of mouse lungs 48 h after infection with wild-type (B and D) and the rtxA mutant (A and C) L. pneumophila strains. Lung sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (A and B) or Warthin-Starry silver stain (C and D). (B) Characteristic example of a mouse lung infected with wild-type L. pneumophila, displaying severe peribronchial pneumonia with leukocytic exudate, necrotic debris, and red blood cells within two small bronchioles. (A) In striking contrast, lungs infected with the ΔrtxA mutant displayed characteristics similar to those of normal healthy mouse lungs, with clear bronchioles and alveoli showing very little or no inflammatory infiltrate. Silver-stained sections (C and D) allowed visualization of bacteria (arrows). Magnification: (A and B) ×400, (C and D) ×1,000.

DISCUSSION

Monocytes utilize a number of relatively nonspecific mechanisms to phagocytose particles, including LPS- (54), surfactant- (51), Fc- (7, 18, 29, 44), complement- (18, 45, 51, 55), and mannose-mediated (33) mechanisms. In addition, pathogens can trigger specific mechanisms to enter monocytes (16, 46, 49). However, little is known about the effects of different entry mechanisms on subsequent intracellular viability of pathogens. We are interested in determining the effects of different entry mechanisms on the pathogenesis of L. pneumophila. Through the identification of the L. pneumophila genes involved in entry and characterization of their role in the establishment of a preferred intracellular niche and production of disease, we hope to improve our understanding of the importance of different entry mechanisms. This information is likely to lead to novel methods for prevention of the disease process prior to invasion, the first step in pathogenesis, before an infection can become well established. The rtxA gene was initially identified because of its role in entry (15). However, in the current study we demonstrate that this gene also affects a number of other phenotypic characteristics potentially associated with pathogenesis, including virulence in mice. Further studies are necessary to determine whether the observed phenotypic effects on adherence, entry, cytotoxicity, pore formation, intracellular growth, and virulence are due to the direct involvement of rtxA or indirect effects on other bacterial factors.

Although the rtxA gene affects adherence to epithelial cells, it is more critical for adherence to monocytes. This observation may provide some insight into the potential host cell receptors involved. The β2 integrin receptor has been shown to be a receptor for RTX proteins from other bacteria (1, 39). Thus, if RtxA binds to a similar receptor, our results may be explained by the fact that epithelial cells normally express much lower levels of β2 integrins than monocytic cells (21, 42). Although the current study does not examine the receptors involved, this model fits well with previous data demonstrating a role for complement receptors in adherence and entry (40, 45). The absence of observable pore formation and cytotoxicity in HEp-2 cells may also be due to the potential involvement of β2 integrins in these events. It is intriguing to speculate that the lack of rtxA cytotoxicity for epithelial cells may help to explain the histopathological observation of the maintenance of an intact respiratory mucosa in the presence of a severe inflammatory response. This pathologic observation is consistent with previous studies on L. pneumophila infections in guinea pigs (34, 64). However, many additional experiments are necessary to clearly demonstrate that the RtxA is involved in a mechanism of entry that occurs via β2 integrins. The ΔrtxA mutant isolated in the current studies should greatly facilitate further research into the role of host cell receptors and signaling pathways in L. pneumophila adherence and entry mechanisms.

It is possible that all of the other phenotypic characteristics that are associated with the ΔrtxA mutation are related to adherence and/or entry. Hypothetically, the mechanism of entry triggered by rtxA could result in signaling events that affect intracellular trafficking. These effects may be responsible for the ability of L. pneumophila to inhibit lysosomal fusion (27, 52). Thus, the role of rtxA in intracellular survival may be explained through effects on trafficking. Examination of the intracellular trafficking of the ΔrtxA mutant after uptake into monocytes should allow us to obtain a better understanding of the role of the rtxA gene in pathogenesis. It has been shown that L. pneumophila replicates primarily within monocytes during disease (17, 22, 41, 65). Although the phenotypic effects of ΔrtxA in vitro were relatively small, the effects in vivo were quite obvious. These data suggest that subtle defects in the ability of L. pneumophila to enter, survive, and replicate in monocytes may dramatically affect the ability to survive in vivo. This is not surprising, considering that all of the components of the host immune system are available in vivo to combat infections. This phenomenon is particularly likely in immune cells such as monocytes, in which proper lymphokine modulation is important for the prevention of intracellular infections. In the absence of a complete understanding of the factors involved in the proper modulation of the bactericidal activity of monocytes, we cannot duplicate these conditions in vitro. These data suggest that it is important to carefully examine potential virulence determinants in vitro for subtle defects and underscore the importance of virulence studies in animal models, where the selection for optimal pathogen-host cell interactions may be more stringent.

The effects of rtxA on adherence may be directly responsible for the defect in the persistence of the ΔrtxA mutant in mouse lungs. However, it is equally possible that the rtxA gene has dual functions, adherence and pore formation, both of which may be important for the pathogenesis of L. pneumophila. Proper intracellular trafficking, cytotoxicity, and prevention of lysosomal fusion by L. pneumophila are thought to be due to a pore-forming activity involving a type IV secretion apparatus (37, 52, 61, 63). Since RTX proteins are known to cause pore formation in host cells (62), it is possible that the rtxA gene product is responsible for this activity. Our observation of a pore-forming activity that requires the presence of the rtxA gene supports this hypothesis. However, it is unlikely that rtxA is solely responsible for the cytotoxicity associated with the dot/icm complex, since an rtxA mutation only partially reduces cytotoxicity (∼37% reduction), whereas dot/icm mutations more significantly reduce cytotoxicity (∼62% reduction) (37). Furthermore, additional cytotoxic (2, 35) and hemolytic (35, 66) proteins are known to be produced by L. pneumophila. It should be possible to construct a conditional mutant to modulate the rtxA phenotype in order to determine whether this gene has dual functions or whether its effects on entry are sufficient to cause the other phenotypic effects observed. However, the rtxA gene is clearly involved in adherence to and entry into monocytes and is critical for the ability of L. pneumophila to survive and replicate in vivo.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by AI40165 from the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ambagala T C, Ambagala A P N, Srikumaran S. The leukotoxin of Pasteurella haemolytica binds to β2 integrins on bovine leukocytes. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;179:161–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb08722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arroyo J, Hurley M C, Wolf M, McClain M S, Eisenstein B I, Engleberg N C. Shuttle mutagenesis of Legionella pneumophila: identification of a gene associated with host cell cytopathicity. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4075–4080. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.9.4075-4080.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balasubramanian V, Pavelka M S, Jr, Bardarov S S, Martin J, Weisbrod T R, McAdam R A, Bloom B R, Jacobs W R., Jr Allelic exchange in Mycobacterium tuberculosis with long linear recombination substrates. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:273–279. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.1.273-279.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baluyut C S, Simonson R R, Bemrick W J, Maheswaran S K. Interaction of Pasteurella haemolytica with bovine neutrophils: identification and partial characterization of a cytotoxin. Am J Vet Res. 1981;42:1920–1926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Behl C, Davis J B, Lesley R, Schubert D. Hydrogen peroxide mediates amyloid beta protein toxicity. Cell. 1994;77:817–827. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90131-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bermudez L E, Petrofsky M, Kolonoski P, Young L S. An animal model of Mycobacterium avium complex disseminated infection after colonization of the intestinal tract. J Infect Dis. 1992;165:75–79. doi: 10.1093/infdis/165.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bermudez L E, Young L S, Enkel H. Interaction of Mycobacterium avium complex with human macrophages: roles of membrane receptors and serum proteins. Infect Immun. 1991;59:1697–1702. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.5.1697-1702.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boehm D F, Welch R A, Snyder I S. Domains of Escherichia coli hemolysin (HlyA) involved in binding of calcium and erythrocyte membranes. Infect Immun. 1990;58:1959–1964. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.6.1959-1964.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brander C, Wyss-Coray T, Mauri D, Bettens F, Pichler W J. Carrier-mediated uptake and presentation of a major histocompatibility complex class I-restricted peptide. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:3217–3223. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830231226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brieland J, Freeman P, Kunkel R, Chrisp C, Hurley M, Fantone J, Engleberg C. Replicative Legionella pneumophila lung infections in intratracheally inoculated A/J mice: a murine model of human Legionnaires' disease. Am J Pathol. 1994;145:1537–1546. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Byrne B, Swanson M S. Expression of Legionella pneumophila virulence traits in response to growth conditions. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3029–3034. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.7.3029-3034.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng X, Cirillo J D, Duhamel G E. Coiling phagocytosis is the predominant mechanism for uptake of Serpulina pilosicoli by human monocytes. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1999;473:207–214. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-4143-1_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cirillo J D, Cirillo S L G, Yan L, Bermudez L E, Falkow S, Tompkins L S. Intracellular growth in Acanthamoeba castellanii affects monocyte entry mechanisms and enhances virulence of Legionella pneumophila. Infect Immun. 1999;67:4427–4434. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.9.4427-4434.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cirillo J D, Falkow S, Tompkins L S. Growth of Legionella pneumophila in Acanthamoeba castellanii enhances invasion. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3254–3261. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.8.3254-3261.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cirillo S L G, Lum J, Cirillo J D. Identification of novel loci involved in entry by Legionella pneumophila. Microbiology. 2000;146:1345–1359. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-6-1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daughaday C C, Brandt W E, McCown J M, Russell P K. Evidence for two mechanisms of dengue virus infection of adherent human monocytes: trypsin-sensitive virus receptors and trypsin-resistant immune complex receptors. Infect Immun. 1981;32:469–473. doi: 10.1128/iai.32.2.469-473.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis G S, Winn W C, Jr, Gump D W, Beaty H N. The kinetics of early inflammatory events during experimental pneumonia due to Legionella pneumophila in guinea pigs. J Infect Dis. 1983;148:823–825. doi: 10.1093/infdis/148.5.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dromer F, Perronne C, Barge J, Vilde J L, Yeni P. Role of IgG and complement component C5 in the initial course of experimental cryptococcosis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1989;78:412–417. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Edelstein P H. Improved semiselective medium for isolation of Legionella pneumophila from contaminated clinical and environmental specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1981;14:298–303. doi: 10.1128/jcm.14.3.298-303.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Engleberg N C, Drutz D J, Eisenstein B I. Cloning and expression of Legionella pneumophila antigens in Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1984;44:222–227. doi: 10.1128/iai.44.2.222-227.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fischer E, Appay M D, Cook J, Kazatchkine M D. Characterization of the human glomerular C3 receptor as the C3b/C4b complement type one (CR1) receptor. J Immunol. 1986;136:1373–1377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fraser D W, Tsai T R, Orenstein W, Parkin W E, Beecham H J, Sharrar R G, Harris J, Mallison G F, Martin S M, McDade J E, Shepard C C, Brachman P S the Field Investigation Team. Legionnaires' disease: description of an epidemic of pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 1977;297:1189–1196. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197712012972201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giannasca K T, Giannasca P J, Neutra M R. Adherence of Salmonella typhimurium to Caco-2 cells: identification of a glycoconjugate receptor. Infect Immun. 1996;64:135–145. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.1.135-145.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goodwin M S, Weiss A A. Adenylate cyclase toxin is critical for colonization and pertussis toxin is critical for lethal infection by Bordetella pertussis in infant mice. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3445–3447. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.10.3445-3447.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Himmel M E, Yates M D, Lauerman L H, Squire P G. Purification and partial characterization of a macrophage cytotoxin from Pasteurella haemolytica. Am J Vet Res. 1982;43:764–767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hiszczynska-Sawicka E, Kur J. Effect of Escherichia coli IHF mutations on plasmid p15A copy number. Plasmid. 1997;38:174–179. doi: 10.1006/plas.1997.1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horwitz M A. The Legionnaires' disease bacterium (Legionella pneumophila) inhibits phagosome-lysosome fusion in human monocytes. J Exp Med. 1983;158:2108–2126. doi: 10.1084/jem.158.6.2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horwitz M A. Phagocytosis of the Legionnaires' disease bacterium (Legionella pneumophila) occurs by a novel mechanism: engulfment within a pseudopod coil. Cell. 1984;36:27–33. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Horwitz M A, Silverstein S C. Interaction of the Legionnaires' disease bacterium (Legionella pneumophila) with human phagocytes. I. L. pneumophila resists killing by polymorphonuclear leukocytes, antibody, and complement. J Exp Med. 1981;153:386–397. doi: 10.1084/jem.153.2.386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Horwitz M A, Silverstein S C. Interaction of the Legionnaires' disease bacterium (Legionella pneumophila) with human phagocytes. II. Antibody promotes binding of L. pneumophila to monocytes but does not inhibit intracellular multiplication. J Exp Med. 1981;153:398–406. doi: 10.1084/jem.153.2.398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Husmann L K, Johnson W. Adherence of Legionella pneumophila to guinea pig peritoneal macrophages, J774 mouse macrophages, and undifferentiated U937 human monocytes: role of Fc and complement receptors. Infect Immun. 1992;60:5212–5218. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.12.5212-5218.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Husmann L K, Johnson W. Cytotoxicity of extracellular Legionella pneumophila. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2111–2114. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.5.2111-2114.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kang B K, Schlesinger L S. Characterization of mannose receptor-dependent phagocytosis mediated by Mycobacterium tuberculosis lipoarabinomannan. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2769–2777. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.2769-2777.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katz S M, Hashemi S. Electron microscopic examination of the inflammatory response to Legionella pneumophila in guinea pigs. Lab Investig. 1982;46:24–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Keen M G, Hoffman P S. Characterization of a Legionella pneumophila extracellular protease exhibiting hemolytic and cytotoxic activities. Infect Immun. 1989;57:732–738. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.3.732-738.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kerr D A. Improved Warthin-Starry method of staining spirochetes in tissue section. Am J Clin Pathol. 1938;8:63–67. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kirby J E, Vogel J P, Andrews H L, Isberg I I. Evidence for pore forming ability by Legionella pneumophila. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:323–336. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krinos C, High A S, Rodgers F G. Role of the 25 kDa major outer membrane protein of Legionella pneumophila in attachment to U-937 cells and its potential as a virulence factor in chick embryos. J Appl Microbiol. 1999;86:237–244. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1999.00667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lally E T, Kieba I R, Sato A, Green C L, Rosenbloom J, Korostoff J, Wang J F, Shenker B J, Ortlepp S, Robinson M K, Billings P C. RTX toxins recognize a β2 integrin on the surface of human target cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:30463–30469. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.48.30463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marra A, Horwitz M A, Shuman H A. The HL-60 model for the interaction of human macrophages with the Legionnaires' disease bacterium. J Immunol. 1990;144:2738–2744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McDade J E, Shepard C C, Fraser D W, Tsai T R, Redus M A, Dowdle W R The Laboratory Investigation Team. Legionnaires' disease: isolation of a bacterium and demonstration of its role in other respiratory disease. N Engl J Med. 1977;297:1197–1203. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197712012972202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miyaguchi M, Uda H, Sakai S, Kubo T, Matsunaga T. Immunohistochemical studies of complement receptor (CR1) in cases with normal sinus mucosa and chronic sinusitis. Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1988;244:350–354. doi: 10.1007/BF00497463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moffat J F, Edelstein P H, Regula D P, Jr, Cirillo J D, Tompkins L S. Effects of an isogenic Zn-metalloprotease-deficient mutant of Legionella pneumophila in a guinea-pig model. Mol Microbiol. 1994;12:693–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nash T W, Libby D M, Horwitz M A. Interaction between the Legionnaires' disease bacterium (Legionella pneumophila) and human alveolar macrophages. J Clin Investig. 1984;74:771–782. doi: 10.1172/JCI111493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Payne N R, Horwitz M A. Phagocytosis of Legionella pneumophila is mediated by human monocyte complement receptors. J Exp Med. 1987;166:1377–1389. doi: 10.1084/jem.166.5.1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pearson R D, Romito R, Symes P H, Harcus J L. Interaction of Leishmania donovani promastigotes with human monocyte-derived macrophages: parasite entry, intracellular survival, and multiplication. Infect Immun. 1981;32:1249–1253. doi: 10.1128/iai.32.3.1249-1253.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rittig M G, Jacoda J C, Wilske B, Murgia R, Cinco M, Repp R, Burmester G R, Krause A. Coiling phagocytosis discriminates between different spirochetes and is enhanced by phorbol myristate acetate and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Infect Immun. 1998;66:627–635. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.2.627-635.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rittig M G, Krause A, Häupl T, Schaible U E, Modolell M, Kramer M D, Lütjen-Drecoll E, Simon M M, Burmester G R. Coiling phagocytosis is the preferential phagocytic mechanism for Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 1992;60:4205–4212. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.10.4205-4212.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Robledo S, Wozencraft A, Valencia A Z, Saravia N. Human monocyte infection by Leishmania (Viannia) panamensis: role of complement receptors and correlation of susceptibility in vitro with clinical phenotype. J Immunol. 1994;152:1265–1276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rosendal S, Devenish J, MacInnes J I, Lumsden J H, Watson S, Xun H. Evaluation of heat-sensitive, neutrophil-toxic, and hemolytic activity of Haemophilus (Actinobacillus) pleuropneumoniae. Am J Vet Res. 1988;49:1053–1058. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rosseau S, Guenther A, Seeger W, Lohmeyer J. Phagocytosis of viable Candida albicans by alveolar macrophages: lack of opsonin function of surfactant protein A. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:421–428. doi: 10.1093/infdis/175.2.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roy C R, Berger K H, Isberg R R. Legionella pneumophila DotA protein is required for early phagosome trafficking decisions that occur within minutes of bacterial uptake. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:663–674. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schiff D E, Kline L, Soldau K, Lee J D, Pugin J, Tobias P S, Ulevitch R J. Phagocytosis of gram-negative bacteria by a unique CD14-dependent mechanism. J Leukocyte Biol. 1997;62:786–794. doi: 10.1002/jlb.62.6.786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schlesinger L S, Horwitz M A. Phenolic glycolipid-1 of Mycobacterium leprae binds complement component C3 in serum and mediates phagocytosis by human monocytes. J Exp Med. 1991;174:1031–1038. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.5.1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Segal G, Purcell M, Shuman H A. Host cell killing and bacterial conjugation require overlapping sets of genes within a 22-kb region of the Legionella pneumophila genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:1669–1674. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shewen P E, Wilkie B N. Cytotoxin of Pasteurella haemolytica acting on bovine leukocytes. Infect Immun. 1982;35:91–94. doi: 10.1128/iai.35.1.91-94.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stone B J, Abu Kwaik Y. Expression of multiple pili by Legionella pneumophila: identification and characterization of a type IV pilin gene and its role in adherence to mammalian and protozoan cells. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1768–1775. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.4.1768-1775.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Taichman N S, Simpson D L, Sakurada S, Cranfield M, DiRienzo J, Slots J. Comparative studies on the biology of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans leukotoxin in primates. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1987;2:97–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1987.tb00270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tsai C C, Shenker B J, DiRienzo J M, Malamud D, Taichman N S. Extraction and isolation of a leukotoxin from Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans with polymyxin B. Infect Immun. 1984;43:700–705. doi: 10.1128/iai.43.2.700-705.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vogel J P, Andrews H L, Wong S K, Isberg R R. Conjugative transfer by the virulence system of Legionella pneumophila. Science. 1998;279:873–876. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5352.873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Welch R A. Pore-forming cytolysin of gram-negative bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:521–528. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wiater L A, Dunn K, Maxfield F R, Shuman H A. Early events in phagosome establishment are required for intracellular survival of Legionella pneumophila. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4450–4460. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.9.4450-4460.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Winn W C, Jr, Davis G S, Gump D W, Craighead J E, Beaty H N. Legionnaires' pneumonia after intratracheal inoculation of guinea pigs and rats. Lab Investig. 1982;47:568–578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Winn W C, Jr, Myerowitz R L. The pathology of Legionella pneumonias: a review of 74 cases and the literature. Hum Pathol. 1981;12:401–422. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(81)80021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wintermeyer E, Rdest U, Ludwig B, Debes A, Hacker J. Characterization of legiolysin (lly), responsible for haemolytic activity, colour production and fluorescence of Legionella pneumophila. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:1135–1143. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zuckman D M, Hung J B, Roy C R. Pore-forming activity is not sufficient for Legionella pneumophila phagosome trafficking and intracellular growth. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:990–1001. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]