Abstract

This paper presents the optimized surface morphology to enhance transferred charge between the mental and dielectric of the modelled triboelectric nanogenerator. The structured shape of the dielectric layer is a vital factor in enhancing the output performance of the triboelectric nanogenerator. In this study, flat, cone, circular and rectangular shapes are structured on the dielectric surface of TENG. Its output performance is examined by conducting a numerical study on the finite element method in COMSOL Multiphysics software. Among the above stated structured surface TENGs, the structured rectangular surface triboelectric nanogenerator produces an improved output open-circuit voltage of 26 V for an externally given 3K Pascal pulse pressure as input. Hence, the result indicates that the structured surface TENGs can make a portable self-powered healthcare device such as heart rate, respiratory rate, and blood pressure measurement.

Keywords: Charge transfer density, Electrostatics, Surface morphology, Solid mechanics, Triboelectric nanogenerator

Charge transfer density; Electrostatics; Surface morphology; Solid mechanics; Triboelectric nanogenerator.

1. Introduction

In this emerging world, some personalized health monitoring and assessment are inevitable to preserve a healthy human life. These health monitoring and assessment systems mainly operate based on the subtle human physiological signal, and the wearable sensors acquire those signals. Wearable sensors play significant roles in capturing such signals. Many researchers are used several wearable sensors. In the proposed system, triboelectric nanogenerator is used to capture such signals. The triboelectric nanogenerator-based health monitoring and assessment system render a self-powered, low-cost, and lightweight system to secure human health from latent disease. Triboelectric nanogenerator is designed with two different triboelectric characteristics polymer materials in which one gains the electrons, and another one loses the electrons while both layers are getting pressed or rubbed [1, 2]. Due to this, opposite charges are developed on the surface of the two polymer materials as per the triboelectric effect and electrostatic induction, which creates a potential difference across the electrodes [3, 4]. Two methods increase the output potential difference of the triboelectric nanogenerator. In the first method, selecting the high charge density triboelectric material from the triboelectric series increases the charge transaction between the dielectric layers. Hence the potential difference across the electrodes also increases [5]. The second method via the geometrical approach can also increase the transferred charge density between the dielectric layers by introducing the nano- or microstructure on the entire dielectric layer, which increases the surface contact between the dielectric layers. Due to this, the transferred charge density also increased [6, 7, 8]. So the potential difference across electrodes also increases [9]. The second method has been used to improve the charge transaction on modelled triboelectric nanogenerator in the proposed system. Here the four different structures are created on the polymer surface, and their output performances are compared. For comparison, the flat, cone, circular and rectangular structures are formed on the polymer surface; among the four structured surfaces, the rectangular structured polymer surface provides more output open-circuit voltage than the other structured surface. The rectangular structured polymer surface has more contact area than other structured polymer layers, whose output performance is enhanced [10]. On the contrary, the flat surface polymer layered TENG provides low output open circuit voltage due to less contact between the polymer layers [11]. Nevertheless, the cone and circular structured polymer surface TENGs provide a moderate output voltage. The following structures are created on TENG tribolayers to improve their generated output voltage are listed below. Liu et al. in 2019 introduced a low-cost self–powered ultra-sensitive pressure sensor for monitoring biological signals. It consists of two multilayered structural units, the first unit is composed of fluorinated ethylene propylene (FEP) back attached copper, and the second unit is composed of protruded microsphere structured polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) on the other fluorinated ethylene propylene (FEP) copper back connected. The sensitivity of the fabricated TENG depends on the weight percentage of the microspheres. Here by varying the weight percentage of the microsphere can get the maximum sensitivity up to 150 mv/Pa. Hence it can monitor the respiratory and pulse rate [12]. In 2018, Chen et al. developed a stretchable TENG, which comprises a micro-patterned PDMS layer and stretchable electrode; both are separated by a thin PDMS frame with an air gap of 2 mm interval. The micro-patterned PDMS improves the frictional contact area and reduces the PDMS surface's viscosity. With tight encapsulation, the entire device can protect from the influence of the external environment, such as humidity changes and energy harvest underwater. This device delivers the output current as 257.5 nA, 50.2 nA and 33.5 nA under a gentle press, stretch and bend, so it is suitable to monitor the human radial artery pulse [2]. Dhakar et al. in 2015 presented a motion sensing triboelectric nanogenerator; it has a nanopillar structured PDMS layer back attached Kapton layer coated with a gold film; the thin gold film acts as an electrode for the designed TENG. Here the Kapton delivers overall strength and robustness to the device, and the nanopillar structured PDMS layer enhances the performance of the contact electrification process. Hence for a mild touch, the designed TENG generates an open circuit voltage of 90V. This device can act as a motion and activity sensor in many applications [13]. In 2017, Ouyang et al. demonstrated a low-cost self-powered ultrasensitive pulse sensor (SUPS) with an excellent output performance, high peak signal-noise ratio and a, long-term performance etc. It carries two friction layers; the first layer is a nanostructured Kapton thin film back attached ultrathin copper layer (50 nm) and the second layer is the nanostructured ultrathin copper layer (50 nm), which acts as another tribolayer as well as electrode. To increase the structural stability, a flexible polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) layer covers the above two layers. The nanostructures on the two friction layer improve the output performance of the designed SUPS. It can act as a self-powered mobile diagnosis of cardiovascular disease [14].

2. Sensor model

The proposed triboelectric nanogenerators have been modelled using COMSOL Multiphysics software. All the proposed TENGs operate on contact separation mode. The contact separation mode carries two different models: the dielectric to dielectric model, and the other is the conductor to dielectric model [5, 15]. Here the dielectric layer and conductor are used as a triboelectric pair; hence the designed model is comes under the dielectric to conductor model. This dielectric to conductor model produces better output performance than the dielectric to dielectric model [15]. The conductor acts as the top electrode and one of the dielectric layers, and the bottom electrode is attached back to another dielectric layer. The human wrist pulse pressure is less than 3K Pascal, which is applied externally back to the bottom electrode of the modelled TENGs [16]. It makes a deformation on the dielectric layer; this deformed dielectric layer comes in contact and is separated from the top electrode; during this process, the charge transaction takes place between the dielectric layers [17, 18]. The Gauss theorem obtains the transferred charge density by Eq. (1): on the dielectric layers [19],

| (1) |

Where ɛrp is the relative permittivity of the polymer, t1 is the thickness of the polymer; x is the distance between the polymer and conductor. The behaviour of the modelled TENG is like a parallel plate capacitor so the voltage across the two electrodes [5] is given by Eq. (2):

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

Where Ed is the polymer inside the electric field, its obtain by Eq. (3): t1 is the polymer thickness, Eair is the inside air electric field which is obtain by Eqs. (4) and (5): x is the distance between the layers, S is the metal area, ɛ0 is the vacuum permittivity, ɛr is the relative dielectric constant, σ is the tribocharge on the inner surfaces. The open-circuit voltage [10] can be obtained by Eq. (6):

| (6) |

Under the short circuit condition, the voltage difference is zero, so the amount of transferred charge (Q) [20] is specified as Eq. (7):

| (7) |

Across the load the generated current I [21]can be derived by Eq. (8):

| (8) |

Where C is the capacitance and V is the voltage between the electrodes.

3. Sensor design

To design the circular form of triboelectric nanogenerator, the polytetrafluoroethylene polymer is used as a negative layer with a dimension of 1 μm diameter and 0.18 μm thickness; from the triboelectric material series, this polytetrafluoroethylene has more negative charge compared to other negative material in the series [22, 23]. Then the aluminium is attached back to the polymer layer, which acts as an electrode whose dimension is 1μm in diameter and .02 nm in thickness. Finally, Copper is used for the positive layer, which acts as another dielectric layer as well as a conductor whose diameter is 1 μm and thickness is 0.2 μm. The two tribo layers are overlapped, and it is separated with an interval of 9.15 × 10−4. Similarly, the other structured TENGs output deformations are used to maintain the distance between the layers of respective triboelectric nanogenerators. The design parametric values for the tribo materials [24] are given in Table 1. To improve the output performance of the designed TENG, different structures are created on its dielectric layer, whose dimensions and improved output voltage values are given in Table 2.

Table 1.

Parametric values for triboelectric materials.

| Material | Parametric Value |

|---|---|

| Polytetrafluoroethylene |

|

| Copper |

|

| Aluminium |

|

Table 2.

TENGs surface structure dimension and its output voltage.

| S.No | Structure | Dimension | Pictorial representation | Improved output voltage in volts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Flat | Nil | 8.17 | |

| 2 | Cone | Radius = 0.08 μm Height = 0.1μm |

11.6 | |

| 3 | Circular | Radius = 0.06 μm Height = 0.08 μm |

22 | |

| 4 | Rectangular | Width = 0.08 μm Depth = 0.08 μm Height = 0.08 μm. |

|

26 |

Here the modelled rectangular structured surface TENG is shown in Figure 1 A, and the output open-circuit voltage of various structured surface triboelectric nanogenerator are shown in Figure 1 B. A single nanostructure is first created on the polymer layer as per the specified dimension. Then multiple structures are filled on the polymer with the help of array operation in the COMSOL multiphysics software. The union operation is used to merge the filled structure with the bottom polymer layer, finally which brings the filled structures and polymer into a single layer. On the other hand, the positive layer is free from nanostructures (i.e.) there is no nanostructure on the positive layer. It is a flat and smooth surface. The materials are chosen for the positive and negative layers from the material option. These nanostructures on the negative layer will improve the contact area between the positive and negative tribolayers. The transferred charge between the two opposite tribolayers is also enhanced. Due to this, an output open-circuit voltage across the terminals of the proposed triboelectric nanogenerator is also increased [25]. The physics must be given from the physics option to simulate the proposed triboelectric nanogenerator.

Figure 1.

(A) Modelled Rectangular structured surface triboelectric nanogenerator (B) The output open-circuit voltage of various structured surface triboelectric nanogenerator.

Initially, from structural mechanics, solid mechanics physics is chosen, which converts the externally applied wrist pulse into displacement. This output displacement decides the charge transaction between the tribolayers, and then the transferred charge decides the output voltage across the terminals of the proposed triboelectric nanogenerator. Finally, electrostatics physics is chosen from the AC/DC, which converts the given displacement into voltage. Then, the produced voltage is collected across the output terminals of the proposed triboelectric nanogenerator. In order to make the simulating time period very fast, the meshing is used which divides the entire structure of the triboelectric nanogenerator into small pieces and simulates each piece one by one. Hence it takes significantly less time to simulate the entire module after completing the simulation on the proposed triboelectric nanogenerator, whose output response is studied with the help of stationary study from the study option in COMSOL multiphysics software. The above five steps are essential to simulate any module in COMSOL multiphysics software [26].

4. Result and discussion

In this section, on the mechanical analysis, the amount of deformation for the externally applied pulse pressure to the flat, cone, circular and rectangular structured dielectric surface TENGs are compared. The generated output open circuit voltage for the given deformation to all the TENGs is compared in an electrical analysis.

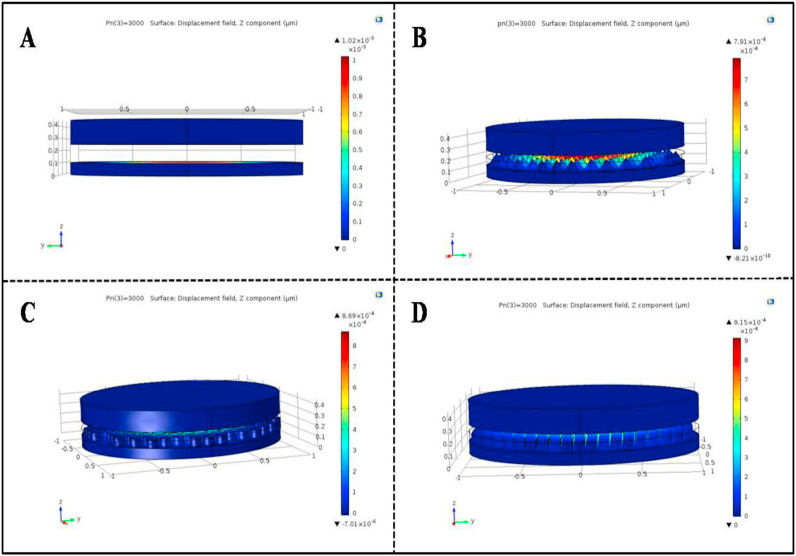

4.1. Solid mechanics

For the structural analysis, the solid mechanics interface is suitable in COMSOL Multiphysics software, which performs the analysis and yields the results based on the solution of Navier's equation [27]. Moreover, it is an excellent tool for stress versus strain analysis on any modelled structure. It has vast module study capabilities such as static, eigenfrequency, time-dependent, frequency response, buckling, parametric studies, etc. The proposed triboelectric nanogenerators are designed in 3D as per the above-mentioned dimension and parametric values. In flat-surfaced TENG, due to the absence of nanostructures on the polymer layer, it has more possibilities to stick the layers on one another; hence the contact separation operation doesn't take place properly even its subjected to an external pulse pressure so the induced voltage at the output terminals is very low compared to the structured TENG [28]. Whereas in the cone structured TENG, whose top surface of the polymer layers is fully filled with cones, each cone has a 0.08μm radius and 0.1μm height dimension. The cone structured TENG provides improved contact and separation operation than flat structured TENG. However, in the case of cylindrical structured TENG, the cylinder shape is filled on the entire top surface of the polymer layer. Each cylinder has a 0.06μm radius and 0.08μm height dimension and whose operating performance is higher than the cone structured TENG. But in the rectangular structured TENG, the top surface of the polymer layers are fully filled with a rectangular shape with the dimension of 0.08μm width, 0.08μm depth and 0.08μm height, which provides better operating performance than the other surface structured TENGs because it has more contact area between the tribolayers due to this whose output open-circuit voltage also high compared to others [29]. Hence concluded that the rectangular structured polymer surface-based TENG is suitable to harvest the human wrist pulse signal, which provides enhanced output compared to the other structured TENGs [30]. For simulating those TENGs whose circumference are fixed constantly by using the fixed constraint option in the solid mechanics interface, which provides stability to the modelled TENGs. For applying the external pulse pressure to the modelled TENGs, the boundary load option in the solid mechanic is used. This modelled triboelectric nanogenerator is placed on the vata nadi position of the human wrist. The human wrist pulse pressure is in the range of less than 3K Pascal, which acts on the bottom of the modelled TENGs. The vata nadi pulse pressure lies within the wrist pulse pressure; hence the wrist pulse pressure is used as an input parameter for simulating the modelled TENGs. The abnormality of the vata nadi is the main cause of inducing blood pressure. Hence the vata nadi position is used to measure blood pressure [31]. The applied pulse pressure produces the deformation on the flat structured TENG in the range of 1.02 × 10−3 μm; similarly, the cone, cylindrical and rectangular structured TENGs produce the deformation in the range of 7.91 × 10−4, 8.69 × 10−4 and 9.15 × 10−4 μm respectively for the given same input pulse pressure. Figure 2 (A-D) shows the COMSOL simulated pictorial representation of various structured TENGs. The overall deformation of various structured TENGs for the given 3 KPa of input pulse pressure is tabulated as shown in Table 3, and its graphical representation is shown in Figure 3. Here the normal meshing simulates the modelled TENGs, which takes less time to compute. The stationary study is used after completing the computation to view the output response. Table 4 shows the variation in deformation of the modelled TENGs to the gradual increase in input pulse pressure from 500 Pa to 3 KPa. Figure 4 shows the linear characteristics between the increase in wrist pulse pressure and a corresponding increase in deformation of different structured surface TENGs. This deformed bottom dielectric layer makes contact and separation with the top dielectric layer based on the wrist pulse signal. Due to this charge, transactions occur between the dielectric layers [7, 32].

Figure 2.

Structural view and deformation of different modelled triboelectric nanogenerators (A) Flat surfaced TENGs (B) Cone structured TENG (C) Circular structured TENG (D) Rectangular structured TENGs.

Table 3.

Overall deformation of different TENGs at 3KPa of applied wrist pulse pressure.

| S.No | Different TENG | Input Pulse Pressure (kPa) | Output Deformation Range (μm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Flat surfaced TENG | 3 | 1.02 × 10−3 |

| 2 | Cone structured TENG | 3 | 7.91 × 10−4 |

| 3 | Circular structured TENG | 3 | 8.69 × 10−4 |

| 4 | Rectangular structured TENG | 3 | 9.15 × 10−4 |

Figure 3.

Deformation of different TENGs at 3 KPa of applied wrist pulse pressure.

Table 4.

Deformation on different TENGs at various ranges of wrist pulse pressures.

| Input pulse pressure (Pa) | Output Deformation in μm |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flat surfaced TENG | Cone structured TENG | Circular structured TENG | Rectangular structured TENG | |

| 500 | 1.17 × 10−4 | 1.32 × 10−4 | 1.45 × 10−4 | 1.53 × 10−4 |

| 1000 | 3.41 × 10−4 | 2.64 × 10−4 | 2.90 × 10−4 | 3.05 × 10−4 |

| 1500 | 5.12 × 10−4 | 3.95 × 10−4 | 4.34 × 10−4 | 4.58 × 10−4 |

| 2000 | 6.82 × 10−4 | 5.27 × 10−4 | 5.79 × 10−4 | 6.65 × 10−4 |

| 2500 | 9.02 × 10−4 | 6.12 × 10−4 | 7.98 × 10−4 | 8.05 × 10−4 |

| 3000 | 1.02 × 10−3 | 7.91 × 10−4 | 8.69 × 10−4 | 9.15 × 10−4 |

Figure 4.

Deformation versus a different range of wrist pulse pressure signal on different structured TENGs.

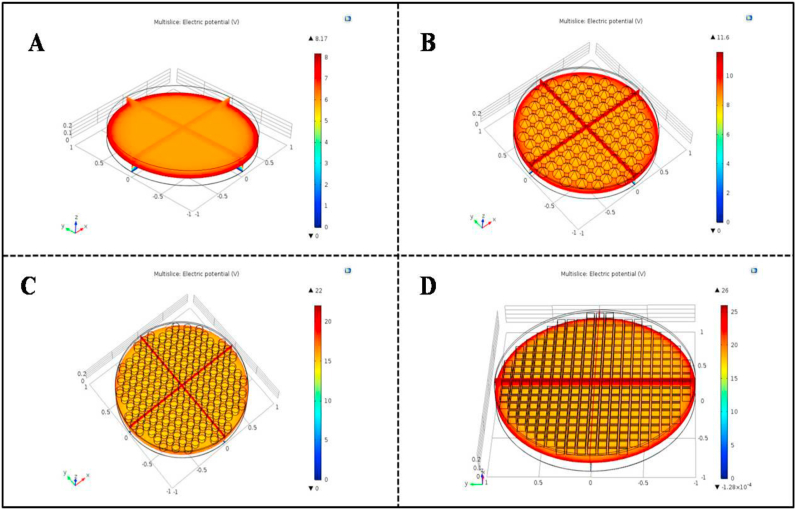

5. Electrostatics

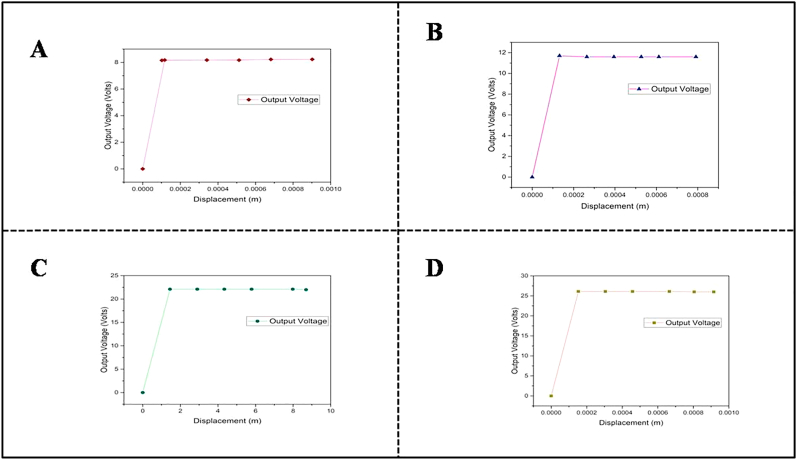

An electrostatic interface is used to compute the potential difference across the modelled TENGs output terminals, which performs the computation based on the solution of Gauss’ law [33]. Here the surface charge density value for the polytetrafluoroethylene is given as 8 × 10−6, and for the Copper, the value is given as 5 × 10−5 by using the surface charge density option in this interface, which is an essential one. In this interface, the previous interface deformed output values are used to maintain the overlapped interval between the tribolayers of the TENGs. The given overlapped interval between the tribolayers is converted into a voltage, and the converted voltage is collected across the terminals of two tribolayers. For the flat-surfaced TENG, the overlapped interval is maintained as 1.02 × 10−3 μm similarly, for the cone, cylindrical and rectangular structured surface TENGs, the overlapped interval is maintained as 7.91 × 10−4, 8.69 × 10−4 and 9.15 × 10−4 μm respectively. While simulating the modelled triboelectric nanogenerators, it creates a contact between the tribolayers on the specified interval and separates the tribolayers based on the pulse pressure. During the presence of pulse pressure, the contact operation takes place, and during the absence of pulse pressure, the separation operation will occur. In contact operation, the charge gets transferred between the tribolayers, while in separation operation, the potential difference exists between the electrodes of the modelled TENGs [34]. Hence the given deformation is converted into potential difference, which is obtained between the electrode and ground terminal of each modelled TENGs by using the float potential option in the same interface as shown in Figure 5 (A-D). Here the top layer act as an electrode and the bottom electrode is grounded using the ground option. Finally, coarse meshing is used in this interface for simulating the modelled TENGs, which makes fast computation. After completing the computation to view the output response of the modelled TENGs, the stationary study is used. Table 5 shows the different TENGs maximum generated output open-circuit voltage. Figure 6 shows the graphical representation between the maximum generated output open-circuit voltages versus overall deformation of the different TENGs. Table 6 shows the different TENGs output open-circuit voltage at various displacement ranges, and its graphical representation is shown in Figure 7 (A-D).

Figure 5.

Structural view and output potential difference of different modelled triboelectric nanogenerator (A) Flat surfaced TENGs (B) Cone structured TENG (C) Circular structured TENG (D) Rectangular structured TENGs.

Table 5.

The output open-circuit voltage of different TENGs.

| S. No | Different TENG | Input Displacement (μm) | Output open-circuit voltage (volts) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Flat surfaced TENG | 1.02 × 10−3 | 8.17 |

| 2 | Cone structured TENG | 7.91 × 10−4 | 11.6 |

| 3 | Circular structure TENG | 8.69 × 10−4 | 22 |

| 4 | Rectangular structured TENG | 9.15 × 10−4 | 26 |

Figure 6.

The output open-circuit voltage of various TENGs for the given overall displacement.

Table 6.

Different TENGs output open-circuit voltage at various ranges of displacement.

| Flat surfaced TENG | Cone structured TENG | Circular structured TENG | Rectangular structured TENG | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input displacement (μm) | Output voltage (Volts) | Input displacement (μm) | Output voltage (Volts) | Input displacement (μm) | Output voltage (Volts) | Input displacement (μm) | Output voltage (Volts) |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1.17 × 10−4 | 8.18 | 1.32 × 10−4 | 11.7 | 1.45 × 10−4 | 22.1 | 1.53 × 10−4 | 26.1 |

| 3.41 × 10−4 | 8.18 | 2.64 × 10−4 | 11.6 | 2.90 × 10−4 | 22.1 | 3.05 × 10−4 | 26.1 |

| 5.12 × 10−4 | 8.17 | 3.95 × 10−4 | 11.6 | 4.34 × 10−4 | 22.1 | 4.58 × 10−4 | 26.1 |

| 6.82 × 10−4 | 8.23 | 5.27 × 10−4 | 11.6 | 5.79 × 10−4 | 22.1 | 6.65 × 10−4 | 26.1 |

| 9.02 × 10−4 | 8.23 | 6.12 × 10−4 | 11.6 | 7.98 × 10−4 | 22.1 | 8.05 × 10−4 | 26 |

| 1.02 × 10−3 | 8.16 | 7.91 × 10−4 | 11.6 | 8.69 × 10−4 | 22 | 9.15 × 10−4 | 26 |

Figure 7.

Different TENGs output open-circuit voltage at various ranges of given displacement (A) Flat surfaced TENGs (B) Cone structured TENG (C) Circular structured TENG (D) Rectangular structured TENGs.

6. Conclusion

Thus the different structured TENGs are designed and simulated using COMSOL Multiphysics Software. The finite element method compares their output open-circuit voltage and deformation on the dielectric layer. Among the different structured surface TENGs, the rectangular structured surface TENG produced more output open-circuit voltage than the other structured surface TENGs. Hence, the structured rectangular surface is an optimized surface morphology that improves response in harvesting the nadi signal for blood pressure measurement. Moreover the designed TENGs are suitable only for biological signal harvesting due its size constraints. In summary the surface structured TENGs work as self-powered monitor for human respiratory rate, muscle movement, gait and CO2 Concentration.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Karthikeyan V: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Vivekanandan S: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of interest's statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

References

- 1.Yang W., et al. 2013. Harvesting Energy from the Natural Vibration of Human Walking; pp. 11317–11324. no. 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen X., et al. Waterproof and stretchable triboelectric nanogenerator for biomechanical energy harvesting and self-powered sensing. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2018;112(20):1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Venugopal K., Panchatcharam P., Chandrasekhar A., Shanmugasundaram V. 2021. Comprehensive Review on Triboelectric Nanogenerator Based Wrist Pulse Measurement: Sensor Fabrication and Diagnosis of Arterial Pressure. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cui X., et al. Pulse sensor based on single-electrode triboelectric nanogenerator. Sensors Actuators, A Phys. 2018;280:326–331. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen H., Xu Y., Zhang J., Wu W., Song G. 2018. Theoretical System of Contact-Mode Triboelectric Nanogenerators for High Energy Conversion Efficiency. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang S., Lin L., Wang Z.L. 2012. Nanoscale Triboelectric-E Ff Ect-Enabled Energy Conversion for Sustainably Powering Portable Electronics. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rasel M.S.U., Park J.Y. A sandpaper assisted micro-structured polydimethylsiloxane fabrication for human skin based triboelectric energy harvesting application. Appl. Energy. 2017;206:150–158. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang H.S., et al. Performance-enhanced triboelectric nanogenerator enabled by wafer-scale nanogrates of multistep pattern downscaling. Nano Energy. 2017;35:415–423. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang H., Yao L., Quan L., Zheng X. 2020. Theories for Triboelectric Nanogenerators : A Comprehensive Review; pp. 610–625. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim S.M., Ha J., Kim J.B. Morphology effect on the transferred charges in triboelectric nanogenerators: numerical study using a finite element method. Integrated Ferroelectrics Int. J. 2017;183(1):19–25. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fan F., Lin L., Zhu G., Wu W., Zhang R., Wang Z.L. 2012. Transparent Triboelectric Nanogenerators and Self-Powered Pressure Sensors Based on Micropatterned Plastic Films. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Z., Zhao Z., Zeng X., Fu X., Hu Y. Expandable microsphere-based triboelectric nanogenerators as ultrasensitive pressure sensors for respiratory and pulse monitoring. Nano Energy. 2019;59:295–301. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dhakar L., Tay F.E.H., Lee C. Skin based flexible triboelectric nanogenerators with motion sensing capability. Proc. - IEEE Int. Conf. Micro Electro Mech. Syst. (MEMS) 2015:106–109. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ouyang H., et al. Self-powered pulse sensor for antidiastole of cardiovascular disease. Adv. Mater. 2017;29(40):1–10. doi: 10.1002/adma.201703456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen G.R., Huang Y.F., Chen Y.Y., Wu C.Y., Tsai Y.C. A flexible triboelectric nanogenerator integrated with an artificial petal micro/nanostructure surface. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2019;58 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shu Y., Li C., Wang Z., Mi W., Li Y., Ren T. 2015. A Pressure Sensing System for Heart Rate Monitoring with Polymer-Based Pressure Sensors and an Anti-interference Post Processing Circuit; pp. 3224–3235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu G., et al. 2012. Triboelectric-Generator-Driven Pulse Electrodeposition for Micropatterning. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu W., et al. Integrated charge excitation triboelectric nanogenerator. Nat. Commun. 2019;10(1):1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09464-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou Y.S., et al. 2014. Manipulating Nanoscale Contact Electri Fi Cation by an Applied Electric Field. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nanogenerator T.T., et al. 2014. Topographically-Designed Triboelectric Nanogenerator via Block Copolymer Self-Assembly. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song W., et al. 2016. A Nanopillar Arrayed Triboelectric Nanogenerator as a Self-Powered Sensitive Sensor for a Sleep Monitoring System. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mathew A.A., Chandrasekhar A., Vivekanandan S. A review on real-time implantable and wearable health monitoring sensors based on triboelectric nanogenerator approach. Nano Energy. November 2020;80 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang N., Tao C., Fan X., Chen J. Progress in triboelectric nanogenerators as self-powered smart sensors. J. Mater. Res. 2017;32(9):1628–1646. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang J., et al. Eardrum-inspired active sensors for self-powered cardiovascular system characterization and throat-attached anti-interference voice recognition. Adv. Mater. 2015;27(8):1316–1326. doi: 10.1002/adma.201404794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Venugopal K., Shanmugasundaram V. 2022. Effective Modeling and Numerical Simulation of Triboelectric Nanogenerator for Blood Pressure Measurement Based on Wrist Pulse Signal Using Comsol Multiphysics Software. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sathya S., Muruganand S., Manikandan N., Karuppasamy K. Design of capacitance based on interdigitated electrode for BioMEMS sensor application. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2019;101:206–213. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parthasarathy P., Vivekanandan S. Modelling And Identification Of Suitable Matrix For Uric Acid Biosensor Using Comsol Multiphysics. BioNanoScience. 2020;9(4):3598–3604. [Google Scholar]

- 28.J. Ahn et al., “Morphology-controllable wrinkled hierarchical structure and its application to superhydrophobic triboelectric nanogenerator,” Nano Energy, vol. 85, no. February, p. 105978, 2021, doi: 10.1016/j.nanoen.2021.105978.

- 29.Min G., Manjakkal L., Mulvihill D.M., Dahiya R.S. Triboelectric nanogenerator with enhanced performance via an optimized low permittivity substrate. IEEE Sensor. J. 2020;20(13):6856–6862. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mathew A.A., Vivekanandan S. Design and simulation of single-electrode mode triboelectric nanogenerator-based pulse sensor for healthcare applications using COMSOL multiphysics. Energy Technol. 2022:1–12. 2101130. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Menon M., Shukla A. Journal of ayurveda and integrative medicine understanding hypertension in the light of ayurveda. J. Ayurveda Integr. Med. 2017;(–6):1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaim.2017.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li R., et al. Smart wearable sensors based on triboelectric nanogenerator for personal healthcare monitoring. Micromachines. 2021;12(4):1–10. doi: 10.3390/mi12040352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Balavalad K.B., Mudhol B., Sheeparamatti B.G., Balavalad P.B. Comparative Analysis on Design and Simulation of Perforated Mems Capacitive Pressure Sensor. International Journal of Engineering Research & Technology (IJERT) 2015;4(7):329–333. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khandelwal G., Chandrasekhar A., Maria Joseph Raj N.P., Kim S.J. Metal–organic framework: a novel material for triboelectric nanogenerator–based self-powered sensors and systems. Adv. Energy Mater. 2019;9(14):1–8. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.