Abstract

Background

The dismal clinical outcome of relapsed/refractory (R/R) T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) highlights the need for innovative targeted therapies. Although chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-engineered T cells have revolutionized the treatment of B cell malignancies, their clinical implementation in T-ALL is in its infancy. CD1a represents a safe target for cortical T-ALL (coT-ALL) patients, and fratricide-resistant CD1a-directed CAR T cells have been preclinically validated as an immunotherapeutic strategy for R/R coT-ALL. Nonetheless, T-ALL relapses are commonly very aggressive and hyperleukocytic, posing a challenge to recover sufficient non-leukemic effector T cells from leukapheresis in R/R T-ALL patients.

Methods

We carried out a comprehensive study using robust in vitro and in vivo assays comparing the efficacy of engineered T cells either expressing a second-generation CD1a-CAR or secreting CD1a x CD3 T cell-engaging Antibodies (CD1a-STAb).

Results

We show that CD1a-T cell engagers bind to cell surface expressed CD1a and CD3 and induce specific T cell activation. Recruitment of bystander T cells endows CD1a-STAbs with an enhanced in vitro cytotoxicity than CD1a-CAR T cells at lower effector:target ratios. CD1a-STAb T cells are as effective as CD1a-CAR T cells in cutting-edge in vivo T-ALL patient-derived xenograft models.

Conclusions

Our data suggest that CD1a-STAb T cells could be an alternative to CD1a-CAR T cells in coT-ALL patients with aggressive and hyperleukocytic relapses with limited numbers of non-leukemic effector T cells.

Keywords: immunotherapy

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Relapsed/refractory coT-acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) displays a poor outcome and CD1a has recently been proposed as a specific and safe target for chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell redirecting strategies in coT-ALL.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Secreted CD1a x CD3 T cell engaging antibodies (CD1a-STAb) show robust efficacy in vitro in recruiting bystander T cells and are as effective as CD1a-CAR T cells in in vivo cutting-edge patient-derived xenograft models.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

This study validates the efficacy of T cell redirecting strategies targeting CD1a for coT-ALL and supports the therapeutic use of CD1a-STAbs as alternative to CD1a-CAR T cells in coT-ALL patients with limited numbers of non-leukemic effector T cells.

Introduction

T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) is a hematological malignancy resulting from the transformation and accumulation of T lineage precursor cells.1 T-ALL is phenotypically and genetically very heterogeneous, with frequent genetic mutations in transcription factors and signaling pathways involved in hematopoietic homeostasis and T cell development.2 3 T-ALL accounts for around 10%–15% and 20%–25% of all acute leukemias diagnosed in children and adults, respectively, with a median age at presentation of 9 years.4 Although intensive chemotherapy regimens developed over the last two decades have allowed improved clinical management and survival rates, the 5-year event-free and overall survival rates are still low, especially in adult patients. More importantly, relapse/refractory (R/R) T-ALL remains a challenge with a particularly dismal outcome and lack of approved potentially curative options beyond hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and conventional chemotherapy, thus highlighting the need for novel targeted therapies.5 6

Immunotherapeutic strategies based on the redirection of the immune effector cells to efficiently recognize and eliminate tumor cells has revolutionized cancer treatment.7 8 In recent years, adoptive cell immunotherapies based on T cells bearing chimeric antigen receptors (CAR T) or systemic administration of bispecific T cell-engaging (TCE) antibodies have shown outstanding response rates in B cell malignancies, mainly B-ALL.9–13 However, T cell-redirecting strategies for T cell malignancies raise additional challenges such as fratricide of effector T cells and potential life-threatening T cell aplasia due to shared antigen expression between effector T cells and T cell blasts,14 15 reinforcing the need of both complex genome editing approaches of uncertain safety/efficacy and novel target antigens differentially expressed between normal T cells and T cell blasts.16–21 In this sense, we have previously identified CD1a as a surface antigen with barely expression across human cells/tissues but highly and consistently expressed in blasts from patients suffering from cortical T-ALL (coT-ALL), a major subgroup of T-ALL, thus representing a therapeutic target for R/R coT-ALL patients while preventing effector T cell fratricide and T cell aplasia. We consequently generated and characterized CD1a-directed CAR T cells for the treatment of coT-ALL with robust and specific cytotoxicity against CD1a+ T-ALL samples both in vitro and in vivo model.22

An emerging strategy which combines advantages of antibody-based and T cell-based therapies, termed Secreting T cell-redirecting Antibodies (STAb)-T immunotherapy,23 involves the use of engineered T cells secreting small-sized bispecific anti-TAA (tumor-associated antigen) x anti-CD3 antibodies, such as diabodies24–26 or tandem scFvs.27 In contrast to CAR T cell therapies, T cell recruitment is not restricted to engineered T cells when using STAb T strategies. The polyclonal recruitment by secreted TCEs of both engineered and unmodified bystander T cells present at the tumor site might boost the antitumor T cell response. In fact, several groups have shown promising therapeutic effects of STAb T cells in CD19+ B cell malignancies.28–30

Here, we report for the first time the generation of STAb T cells secreting an anti-CD1a x anti-CD3 TCE (CD1a-STAb T cells) and demonstrate their efficacy in several in vitro and in vivo cutting-edge models of coT-ALL. Our results indicate that STAb T therapy controls tumor progression similar to CD1a-CAR T therapy and exhibits slightly higher persistence of T cells in vivo. Our study suggests that CD1a-STAb T cells represent an alternative to CD1a-CAR T cells in coT-ALL, especially in R/R patients with leukapheresis products showing limited numbers of non-tumoral effector T cells.

Methods

Cell lines and culture conditions

HEK293T (CRL-3216), MOLT4 (CRL-1582, ACC 362), NALM6 (CRL-3273), and K562 (CCL-243) cell lines were purchased either from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, Maryland, USA) or the DSMZ (Braunschweig, Germany). Target cells expressing the firefly luciferase gene were either produced in house (NALM6Luc, K562Luc) or a gift from Jan Cools Laboratory (MOLT4Luc). HEK293T cells stably expressing extracellular CD1a (HEK293TCD1a) were generated in house by transduction with pCCL lentiviral vectors encoding CD1a cDNA and cell sorting with anti-CD1a antibodies. HEK293T (WT and CD1a) cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Lonza, Walkersville, Maryland, USA) supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine (Life Technologies, Paisley, UK), 10% (vol/vol) heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics (100 units/mL penicillin, 100 µg/mL streptomycin) (both from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA), referred to as DMEM complete medium. MOLT4, NALM6, and K562 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 (Lonza) supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 10% heat-inactivated FBS and antibiotics, referred to as RPMI complete medium (RCM). All the cell lines were grown at 37°C in 5% CO2 and routinely screened for mycoplasma contamination by PCR using the Mycoplasma Gel Detection Kit (Biotools, Madrid, Spain).

Vector construction

The pCDNA3.1-CD1a-scFv expression vector encoding the human kappa (κ) light chain signal peptide L1,31 followed by the NA1/34.HLK clone-derived CD1a scFv (VH–VL)22 and a C-terminal polyHis tag was synthesized by GeneArt AG (ThermoFisher Scientific, Regensburg, Germany). To generate the CD1a-TCE-encoding lentiviral transfer vector, a synthetic gene encoding the L1-CD1a-scFv flanked by MluI and AfeI was synthesized by GeneArt AG and cloned into the vector pCCL-EF1α-LiTE-T2A-EGFP (unpublished), obtaining the plasmid pCCL-EF1α-CD1a-TCE-T2A-EGFP. The lentiviral transfer vector pCCL-EF1α-CD1a-CAR-T2A-EGFP encoding the CD1a-CAR was previously described.22 pCCL lentiviral vectors encoding CD1a cDNA were obtained by blunt-XhoI and BamHI subcloning from CD1A_OHu13436C_pcDNA3.1(+) (GenScript) into blunt-BspEI and BamHI pCCL.

Cell transfection, T cell binding and activation assays

HEK293TWT cells were transfected with the appropriate expression vectors using Lipofectamine 3000 Reagent (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. After 48 hours, transiently transfected HEK293TWT cells were analyzed by flow cytometry and conditioned media were collected and stored at −20°C for western blotting, TCE binding assays and T cell activation studies. For CD1a-TCE binding assay, conditioned media from transiently transfected HEK293TWT cells were incubated with CD1a-negative and CD1a-positive cells and analyzed with an APC-conjugated anti-His mAb (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA, USA) by flow cytometry. For T cell activation assays, CD1a-negative and CD1a-positive cells were cocultured with freshly isolated T cells at a 1:1 effector:target (E:T) ratio in the presence of conditioned media from transiently transfected HEK293TWT cells. After 24 hours, T cell activation was analyzed by flow cytometry using PE-conjugated anti-CD69 mAb.

Western blotting

Samples were separated under reducing conditions on 10%–20% Tris-glycine gels (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, California, USA), transferred onto PVDF membranes (Merck Millipore, Tullagreen, Carrigtwohill, Ireland) and probed with 200 ng/mL anti-His mAb (Qiagen, Hilden Germany), followed by incubation with 1.6 µg/mL horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG, Fc specific (Sigma-Aldrich). Visualization of protein bands was performed with Pierce ECL Western Blotting substrate (Rockford, IL, USA) and ChemiDoc MP Imaging System machine (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, California, USA).

Lentivirus production and titration

CD1a, CD1a-CAR- or CD1a-TCE-encoding viral particles pseudotyped with vesicular stomatitis virus G glycoprotein were generated in HEK293T cells by using standard polyethylenimine transfection protocols and concentrated by ultracentrifugation, as previously described.22 Viral titers were consistently in the range of 1×108 transducing units/mL. Functional titers of CD1a-CAR- and CD1a-TCE-encoding lentiviruses were determined by limiting dilution in HEK293T cells and analyzed using green fluorescent protein (EGFP) expression by flow cytometry.

T cell transduction and culture conditions

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated from volunteer healthy donors’ peripheral blood (PB) or buffy coats by density-gradient centrifugation using Lymphoprep (Axis-Shield, Oslo, Norway) or Ficoll Paque Plus (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK). PBMC were plate-coated activated with 1 µg/mL anti-CD3 (OKT3) and 1 µg/mL anti-CD28 (CD28.2) mAbs (BD Biosciences) for 2 days and transduced (MOI of 10) with CD1a-CAR- or CD1a-STAb-encoding lentiviruses in the presence of 10 ng/mL interleukin (IL)-7 and 10 ng/mL IL-15 (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). As negative controls, non-transduced or GFP-transduced T cells were used (NT). T cells were expanded in RCM supplemented with IL-7 and IL-15 (10 ng/mL) (Miltenyi Biotec).22 32

Cytotoxicity assays

For cytotoxicity assays, target cells (cell lines and primary T-ALL blasts, 1×105 cells/well in a 96-well plate for cell lines and 2×105 for primary blasts) were labeled with 3 µM cell proliferation dye eFluor 670 (ThermoFisher Scientific) following manufacturer’s instructions and co-cultured with NT, CD1a-CAR, or CD1a-STAb T cells at different E:T ratios for the indicated time periods. Effector cell-mediated cytotoxicity was assessed by flow cytometry analyzing the residual alive, non-apoptotic (7-aminoactinomycin D-, AnnexinV-) eFluor 670-positive target cells in each condition. For primary T-ALL blasts, absolute counts of target cells were also determined by using Trucount absolute counting tubes (BD Biosciences).22 Additional wells with only target cells were always plated as controls. For bystander cytotoxicity assays, CD1a-CAR or CD1a-STAb T cells were co-cultured with or without non-transduced activated T cells (NT) and luciferase-expressing target cells (K562Luc or MOLT4Luc) at the indicated E:T ratios. As controls, NT cells were cultured with target cells. After 48 hours, supernatants were collected and stored at −20°C for cytokine secretion analysis, and 20 µg/mL D-luciferin (Promega) was added before bioluminescence quantification using a Victor luminometer (PerkinElmer, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). Percent-specific cytotoxicity was calculated using the formula: 100 – [(bioluminescence of each sample*100) / mean bioluminescence of NT-target cells]. Specific lysis was established as 100% of cell viability, and 100% lysis was established by adding 5% Triton X-100 into target cells. For cytotoxic studies using transwell non-contacting system, 5×104 K562Luc or MOLT4Luc cells and 1×105 NT cells were plated on bottom wells, and CD1a-CAR, CD1a-STAb or NT T cells were added at the indicated ratios into 0.4 μm-pore polycarbonate insert wells (Corning, Kennebunk, Maine, USA). Bioluminescence was quantified after 48 hours. For real-time cytotoxicity assays, the xCELLigence RTCA DP system (Acea BioSciences, San Diego, California, USA) was used. At day 0 1×104, HEK293TWT or HEK293TCD1a cells were plated in an E-Plate 16 (Acea Biosciences) and cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2. After 24 hours, NT, CD1a-CAR or CD1a-STAb T cells were added at different E:T ratios and cell index values were measured every 15 min for 80 hours using RTCA Software 2.0 (Acea Biosciences). Specific lysis was established as 100% of cell viability of target cells, and 100% lysis was established by adding 10-fold diluted (in RCM) Cytolysis Reagent (Acea Biosciences) instead of effector cells.

Cytokine secretion analysis

IFN-γ, TNFα, and IL-2 secretion was analyzed by ELISA (Diaclone, Besancon Cedex, France; BD Biosciences), following manufacturer’s instructions.

Flow cytometry

Antibodies used for flow cytometry analysis are detailed in online supplemental table S1. Cell surface expression of CD1a-CAR and cell surface-bound CD1a-TCE were detected using a biotin-SP goat anti-mouse IgG, F(ab')2 (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, Pennsylvania, USA) and PE-conjugated streptavidin (ThermoFisher Scientific). Cell acquisition was performed in a BD FACSCanto II flow cytometer using BD FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences). Analysis was performed using FlowJo V10 software (Tree Star, Ashland, Oregon, USA).

jitc-2022-005333supp001.pdf (127.6KB, pdf)

In vivo T-ALL xenograft models

Seven to twelve-week-old NOD.Cγ-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl /SzJ mice (NSG; The Jackson Laboratory, USA) were bred and housed under pathogen-free conditions. Mice were infused intravenously with 3×106 MOLT4Luc cells and 3 days later received 5×106 NT, CD1a-CAR, or CD1a-STAb T cells. Tumor growth was evaluated twice a week by bioluminescence imaging as previously described.22 32 Tumor burden and T cell persistence was evaluated by flow cytometry in PB, and bone marrow (BM) after sacrifice at week 3. For T-ALL patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models, seven-to twelve-week-old NSG mice were sublethal irradiated (2 Gy) and intravenously transplanted with 1×106 CD1a+ T-ALL PDX blasts. Two weeks later, mice were intravenously infused with 3–4×106 NT, CAR-CD1a, or STAb-CD1a T cells. Tumor burden and effector T cell persistence was followed up every 2 weeks by bleeding and by BM analysis at different time points, and subsequent flow cytometry analysis. In vivo studies were carried out at the Barcelona Biomedical Research Park (PRBB) in accordance with the guidelines of the Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee. All procedures were performed in compliance with the institutional animal care committee of the PRBB (DAAM9624).

Statistical analysis

Results of experiments are expressed as mean or mean±SE of the mean (SEM). Statistical tests indicated in figure legends were performed using Prism V.6 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, California, USA). Significance was considered only when p values were less than 0.05 (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001).

Results

The CD1a-TCE binds to cell surface expressed CD1a and CD3 and induces specific T cell activation

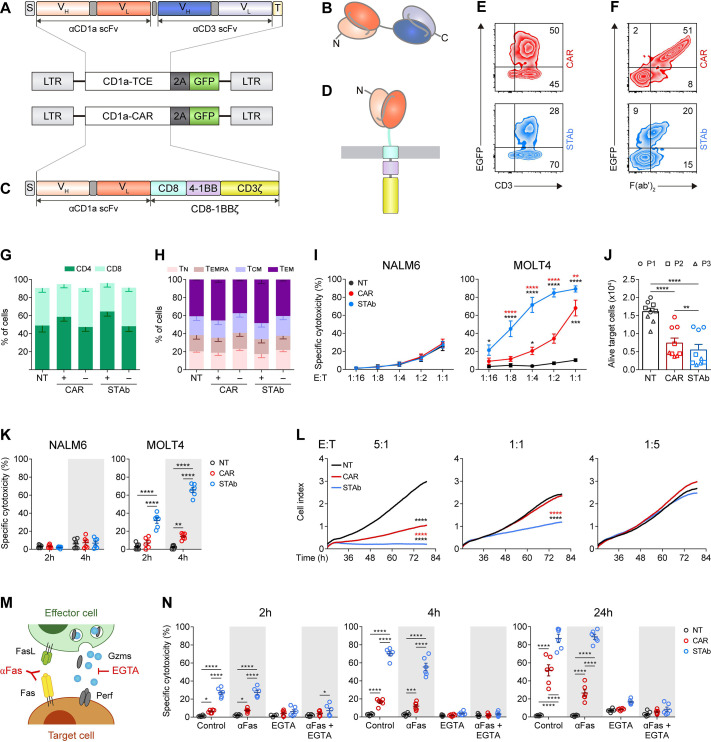

To generate a small-sized Fc-free CD1a-directed TCE, the NA1/34.HLK scFv and the OKT3 scFv were fused in tandem via a G4S peptide linker27 and cloned under the control of the EF1α promoter in a T2A-based bicistronic lentiviral vector (pCCL-EF1α-CD1a-TCE-T2A-EGFP, figure 1A, B). The vector encoding an anti-CD1a second-generation (4-1BB-based) CAR (pCCL-EF1α-CD1a-CAR-T2A-EGFP, figure 1C, D) has been described previously.22 The CD1a-TCE was efficiently secreted by transfected HEK293TWT cells with the expected molecular weight of 58 kDa (online supplemental figure S1A). Binding assays using CD1a-CD3- K562 cells, CD1a+CD3- MOLT4 cells, and CD1a-CD3+ primary PB lymphocytes (online supplemental figure S2) demonstrated the bispecificity of the secreted CD1a-TCE (online supplemental figure S1B). To study the biological activity of the secreted CD1a-TCE on T cell activation, primary T cells were co-cultured with K562 or MOLT4 cells in the presence of cell-free conditioned medium (CM) derived from non-transfected (NT) or transiently transfected (CD1a-CAR or CD1a-TCE) HEK293TWT cells. High expression of CD69 was detected only when T cells were co-cultured with CD1a-positive cells in the presence of CD1a-TCE CM. T cell activation was not detected when CM from NT or CD1a-CAR-transfected HEK293TWT cells were used (online supplemental figure S1C).

Figure 1.

Comparative in vitro study of engineered CD1a-STAb and CD1a-CAR T cells. (A, B) Schematic diagrams showing the genetic (A) and domain structure (B) of the CD1a-TCE bearing a signal peptide from the human κ light chain signal peptide (S, gray box), the anti-CD1a scFv gene (orange boxes), the anti-CD3 scFv gene (blue boxes), and the Myc and his tags (light yellow box). (C, D) Schematic diagrams showing the genetic (C) and domain structure (D) of the CD1a-CAR bearing the CD8a signal peptide (S, gray box), the anti-CD1a scFv gene (orange boxes), followed by the human CD8 transmembrane domain and the human 4-1BB and CD3ζ endodomains. CD1a-TCE and CD1a-CAR constructs were cloned into a pCCL lentiviral-based backbone containing a T2A-enhanced green fluorescent protein (GFP) cassette (A, C). (E, F) Percentage of reporter GFP (E) and F(ab')2 (F) expression in CD1a-CAR and CD1a-STAb T cells. One representative transduction out of four independent transductions performed is shown. Numbers represent the percentage of cells staining positive for the indicated marker. (G, H) Percentages of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (G) and percentages of naïve (TN), effector memory re-expressing CD45RA (TEMRA), central memory (TCM), and effector (TEM) T cells (H) among non-transduced (NT), or CD1a-CAR and CD1a-STAb transduced T cells. (I) Specific cytotoxicity of NT, CD1a-CAR or CD1a-STAb T cells toward CD1a negative (NALM6) or CD1a positive (MOLT4) cells at the indicated E:T ratios after 24 hours. (J) Alive primary cells from three different coT-ALL patients (P1, P2, P3) after 24 hours co-culture at a 1:1 E:T ratio with NT, CD1a-CAR or CD1a-STAb T cells. (K) Specific cytotoxicity of NT, CD1a-CAR or CD1a-STAb T cells toward NALM6 or MOLT4 cells at 1:4 E:T ratio after 2 and 4 hours. (L) Real-time cell cytotoxicity assay with HEK293TCD1a target cells co-cultured with NT, CD1a-CAR or CD1a-STAb T cells at the indicated E:T ratios. Cell index values were determined every 15 min for 80 hours using an impedance-based method. Data from (G–L) is shown as mean±SEM of at least three independent experiments by triplicates (n=9). (M) Cartoon depicting target cell death induction by FasL and perforin/granzymes, and how these pathways can be blocked using anti-Fas mAb or EGTA, respectively. (N) Cytotoxicity of MOLT4 cells at 2 and 4 hours (E:T ratio 1:1) and at 24 hours (E:T ratio 1:4) in the presence or absence of anti-Fas mAb or EGTA. Plots show mean±SEM of two independent experiments with triplicates (n=6). Statistical significance was calculated by one-way (L) or two-way (G–K, N) ANOVA test corrected with a Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001). ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; ANOVA, analysis of variance; CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; E:T, effector:target; STAb, secreting T cell-redirecting antibodies.

jitc-2022-005333supp002.pdf (290.5KB, pdf)

jitc-2022-005333supp003.pdf (211.3KB, pdf)

Generation of human primary CD1a-STAb T cells

We next transduced primary T cells with CD1a-CAR- or CD1a-TCE-encoding lentiviruses. Transduction efficiencies were determined by flow cytometry after 4–8 days according to the percentage of GFP+CD3+ cells (figure 1E). CD1a-CAR surface expression as well as CD1a-TCE decoration in CD1a-STAb T cells were successfully detected using a polyclonal anti-F(ab')2 antibody (figure 1F) recognizing the scFv domains of both CD1a-CAR and CD1a-TCE constructs. Transduction efficiencies were 40%–50% and 20%–30% for CD1a-CAR- and CD1a-TCE-transduced T cells, respectively. While in CD1a-CAR-transduced T cells the expression of EGFP and F(ab')2 mainly identifies a single transduced population (figure 1F, upper panel), in CD1a-TCE-transduced T cells several subpopulations are distinguished: transduced/decorated T cells (GFP+F(ab')2 +), non-transduced/decorated T cells (GFP-F(ab')2 +), and transduced/non-decorated T cells (GFP+F(ab')2 -) (figure 1F, lower panel). Transduced CD1a-CAR T cells and CD1a-STAb T cells exhibited a similar proportion of CD4+ and CD8+ cells (figure 1G). The relative distribution of naïve, central memory, effector memory, and effector T cell subsets was similar in NT, CD1a-CAR+/– and CD1a-STAb+/– T cells, with the most prevalent subset being effector memory T cells (figure 1H).

STAb-CD1a T cells induce a more potent and rapid cytotoxic responses than CAR-CD1a T cells

To test the ability of CD1a-CAR and CD1a-STAb T cells to kill CD1a+ T-ALL cells, several cytotoxicity assays were conducted. First, we studied the killing capacity of non-transduced (NT), CD1a-CAR, and CD1a-STAb transduced T cells at different E:T ratios after 24 hour co-culture with CD1a– (NALM6) or CD1a+ (MOLT4) cells (online supplemental figure S2). CD1a-STAb T cells were able to significantly eliminate CD1a+ cells even at a 1:16 E:T ratio and induce ~90% cytotoxicity at a 1:1 E:T ratio. In contrast, CD1a-CAR T cells only exhibited significant cytotoxicity at high E:T ratios (figure 1I). Similar results were obtained using primary T-ALL samples in 24 hour assays, where co-culture with CD1a-STAb T cells induced a slight increase in target cell death compared with CD1a-CAR T cells (figure 1J, online supplemental figure S2). In short-time co-culture systems with CD1a– or CD1a+ target cells at a 1:4 E:T ratio, CD1a-STAb T cells killed, in clear contrast to CD1a-CAR T cells, a significant proportion of leukemic cells after 2 hours (35%) and 4 hours (70%) (figure 1K). Next, using an impedance-based real-time cytotoxicity assay, CD1a-STAb T cells mediated a rapid reduction of CD1a+ target cell viability (online supplemental figure S3A), whereas CD1a-CAR T cells showed a significantly lower cytotoxic effect that required higher E:T ratios (figure 1L). Target cells cultured alone (online supplemental figure S3B) revealed similar viability kinetics to the co-culture of NT cells with CD1a+ cells as well as the co-culture of NT, CD1a-CAR or CD1a-STAb T cells with CD1a– cells (online supplemental figure S3C).

jitc-2022-005333supp004.pdf (1.5MB, pdf)

After 24 hour co-culture at a 1:1 E:T ratio, TNFα was significantly increased only in co-cultures of CD1a+ target cells with CD1a-STAb T cells. However, IL-2 secretion was significantly higher in co-cultures of CD1a+ target cells with CD1a-CAR T cells (online supplemental figure S3D). IFNγ levels were similar in co-cultures of CD1a-CAR or CD1a-STAb T cells with MOLT4 and primary T-ALL cells (online supplemental figure S3D), revealing different proinflammatory cytokine profiles depending on whether the CD1a-specific interaction was triggered by CAR or STAb T cells.

CD1a-STAb T cells eliminate T-ALL cells through the granular exocytosis pathway

To determine the effector mechanisms involved in CD1a-CAR and CD1a-STAb killing of T-ALL cells, we used the Ca2+-chelating agent EGTA to inhibit granular exocytosis and/or a blocking anti-Fas mAb18 33 (figure 1M). In control (untreated) conditions, CD1a-STAb T cells induce higher cytotoxicity than CD1a-CAR-T cells on MOLT4 cells at the different time points tested (2, 4, and 24 hours). The cytotoxic action of both CD1a-CAR and CD1a-STAb T cells was completely ablated on EGTA treatment, indicating their dependence on the granular exocytosis pathway to induce target cell death (figure 1N). However, Fas blockage did not diminish lysis levels, showing no influence in the cytotoxic process (figure 1N). These data suggest that CD1a-directed CAR and STAb T cells follow a different kinetic profile but share the same cytolytic effector mechanisms.

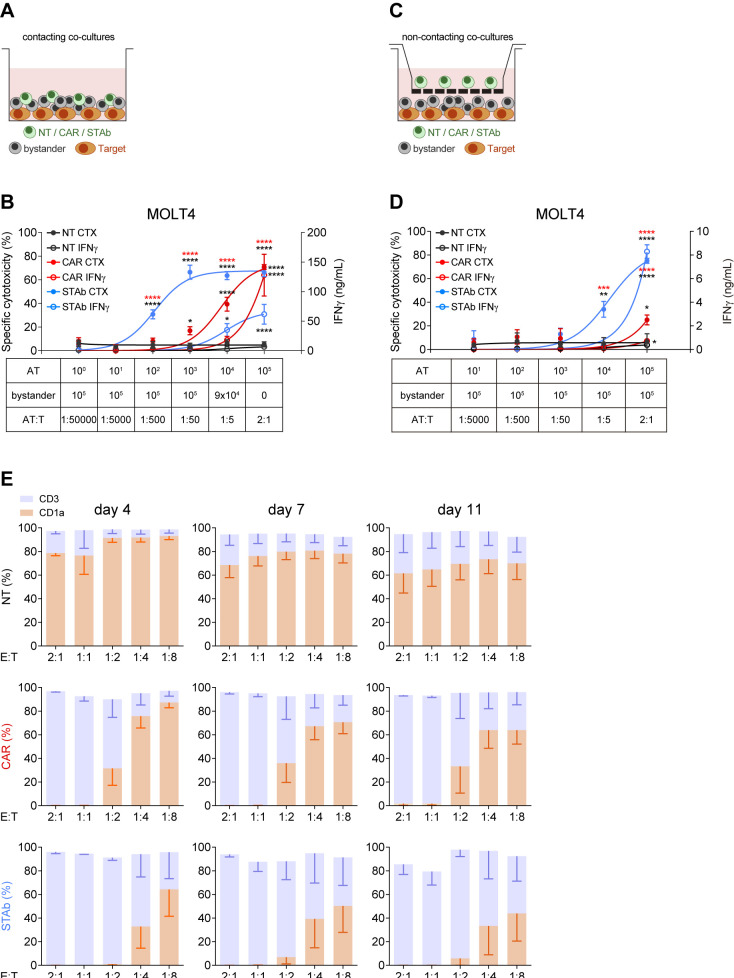

Recruitment of bystander T cells provides STAb-CD1a T cells with greater in vitro tumor cell killing efficiency than CD1a-CAR T cells

To study the ability of CD1a-STAb T cells to recruit non-engineered bystander T cells, direct contacting co-culture systems were performed (figure 2A). Keeping a constant number of 5×104 CD1a+ MOLT4Luc cells, decreasing numbers of activated effector T cells (AT: NT, CD1a-CAR or CD1a-STAb T cells) were added to the culture, resulting in different AT:Target ratios (from 1:50 000 to 2:1). Increasing numbers of NT bystander T cells were added to maintain a constant 2:1 E(AT+bystander):T ratio (figure 2C). The bystander recruitment ability of CD1a-STAb T cells was demonstrated by their enhanced specific cytotoxicity achieved at an E:T ratio as low as 1:50 after 48 hour co-culture with MOLT4Luc cells. In contrast, CD1a-CAR T cell-mediated cytotoxicity against CD1a+ cells only reached that shown by CD1a-STAb T cells at the highest E:T ratio (2:1), with significantly reduced cytotoxicity across lower E:T ratios.

Figure 2.

STAb-CD1a T cells display enhanced tumor cell killing by recruiting bystander T cells. (A, B) Schematic representation of the direct contact (A) and the non-contacting Transwell (B) co-culture systems used to study the ability of secreted CD1a-STAb to induce bystander T cell cytotoxicity. (C) Decreasing numbers of activated effector T (AT) cells (NT, CD1a-CAR or CD1a-STAb) were co-cultured with 5×104 MOLT4Luc target cells and increasing numbers of NT T cells from the same donor (bystander T cells), resulting in the indicated AT:T ratios but maintaining a constant 2:1 effector (AT+bystander):Target ratio. (D) 5×104 MOLT4Luc cells and 1×105 bystander T cells were plated in the bottom well and decreasing numbers (from 1×105 to 1 x 101) of activated T (AT) cells (NT, CD1a-CAR or CD1a-STAb) in the upper well. After 48 hours, the percentage of specific cytotoxicity was calculated by adding D-luciferin to detect bioluminescence, and IFNγ secretion was determined by ELISA (C, D). (E) MOLT4 cells were co-cultured with NT, CD1a-CAR or CD1a-STAb T cells at the indicated E:T ratios, and the expression of CD3 and CD1a was analyzed by flow cytometry after 4 and 11 days to assess potential leukemia escape. Data represent mean±SEM of at least three independent experiments by triplicates. Significance was calculated by a two-way ANOVA test corrected with a Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001). ANOVA, analysis of variance; E:T, effector:target; NT, non-transduced; CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; STAb, secreting T cell-redirecting antibodies.

Interestingly, the levels of IFNγ secretion by CD1a-CAR T cells were higher than in CD1a-STAb T cells at the highest E:T condition (figure 2C), but these levels rapidly decreased at lower E:T ratios, indicating that the bystander effect mediated from CD1a-STAb T cells offers equal or superior cytotoxicity capacity than CD1a-CAR T cells without an enhanced cytokine release. No cytotoxicity, bystander effect or IFNγ secretion were detected after 48 hours direct co-culture of activated effector cells with CD1a– (K562Luc) cells (online supplemental figure S3E).

To further demonstrate the bystander effect of CD1a-STAb T cells, similar co-cultures were performed in a non-contacting transwell system (figure 2B). Keeping a constant number of 5×104 MOLT4Luc cells and 1×105 non-engineered bystander T cells both plated in the bottom well, decreasing numbers (from 1×105 to 1 x 101) of AT (NT, CD1a-CAR or CD1a-STAb T cells) were plated in the insert upper well of the transwell system. After 48 hours, cell killing was only detected when CD1a-STAb T cells were present, indicating that secreted CD1a-TCEs effectively redirected non-engineered bystander T cells toward CD1a+ target cells in the bottom wells (figure 2D). IFNγ secretion was also dependent on the presence of CD1a-STAb T cells in the transwell system (figure 2D). In contrast, no cytotoxicity or IFNγ secretion were detected in the presence of CD1a-CAR T cells, or when the target cells were CD1a– (online supplemental figure S3F).

In addition, we studied whether cortical T-ALL cells were able to escape from immune control by co-culturing either NT, CD1a-CAR or CD1a-STAb T cells with MOLT4 cells at low E:T ratios. After 4 days coculture, CD1a-STAb T cells completely eliminated leukemic cells at 2:1, 1:1 and 1:2 E:T ratios; even after 11 days, leukemic cell numbers were restrained below 10% of total cells (figure 2E). In contrast, CD1a-CAR T cells were not able to control MOLT4 growth below the 1:1 E:T ratio. No cell surface CD1a down-modulation was detected when MOLT4 cells were co-cultured with CD1a-CAR or CD1a-STAb T cells (online supplemental figure S3G).

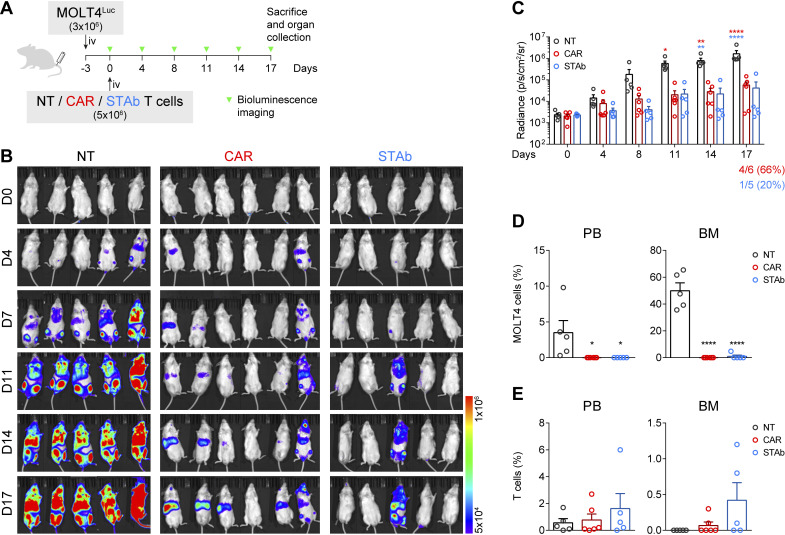

CD1a-STAb T cells are as effective as CD1a-CAR T cells in short-term in vivo T-ALL models

The antitumor effect of CD1a-STAb T cells was evaluated in a coT-ALL xenograft model. 3×106 MOLT4Luc cells were intravenously injected in NSG mice, followed by intravenously administration of 5×106 NT, CD1a-CAR, or CD1a-STAb T cells 3 days later (figure 3A). BLI of the mice was done twice per week at the indicated time points to assess leukemia progression (figure 3A). While all NT-treated mice showed unrestricted leukemia development, both the CD1a-CAR- and CD1a-STAb-treated groups were equally able to control disease progression, as evidenced by BLI (figure 3B, C). Even though bioluminescence analysis showed some tumor burden in 4/6 mice in the CD1a-CAR group and only in 1/5 in the CD1a-STAb group, flow cytometry analysis of PB and BM at sacrifice revealed complete control of the disease in both CD1a-CAR-treated and CD1a-STAb-treated mice (figure 3D). Regarding T cell persistence, we observed similar levels across all treatments in all tissues analyzed, with a non-statistically significant tendency for higher persistence in the CD1a-STAb group (figure 3E).

Figure 3.

CD1a-STAb T cells control the progression of coT-ALL cells in vivo. (A) Experimental design of in vivo cytotoxicity in NSG mice intravenously engrafted with MOLT4Luc cells followed by infusion of NT, CD1a-CAR, or CD1a-STAb T cells. (B, C) Bioluminescence images monitoring disease progression (B) and total RADIANCE quantification at the indicated time points (C). (D) Percentage of MOLT4 cells, identified as HLA-ABC+CD45+CD1a+CD3– by flow cytometry, in peripheral blood (PB) and bone marrow (BM) at sacrifice. (E) Percentage of T cells, identified as HLA-ABC+CD45+CD1a–CD3+ by flow cytometry, in PB, BM and spleen at sacrifice. Plots from (C), D), E) show mean±SEM of at least 5 mice per group. Statistical significance was calculated by an one-way ANOVA test corrected with a Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001). ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; ANOVA, analysis of variance; NT, non-transduced; CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; STAb, secreting T cell-redirecting antibodies.

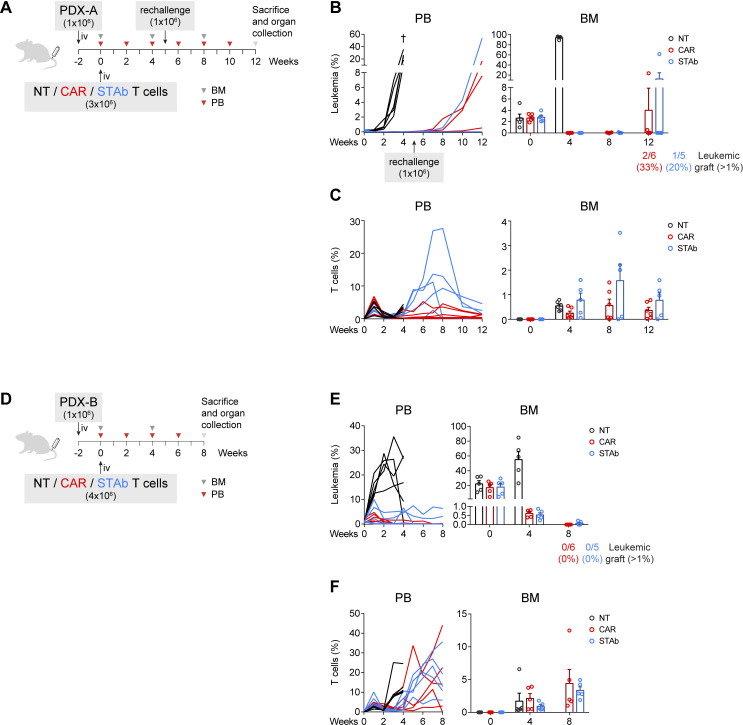

CD1a-STAb and CD1a-CAR T cells are effective in eliminating primary T-ALL in long-term in vivo models

The effectiveness of CD1a-STAb T cells and CD1a-CAR T cells were also compared side-by-side against primary samples in vivo. Two independent CD1a+ coT-ALL PDX models with different aggressiveness were used. We intravenouslyinjected 1×106 leukemic blasts for both models in NSG mice, and 2 weeks later, after confirming leukemic engraftment in the BM, 3×106 (PDX-A) or 4×106 (PDX-B) effector T cells were intravenously injected (figure 4A, D). In the PDX-A model we tested the efficacy of both T cell-redirecting strategies in a setting with relatively low tumor burden, around 2% blasts in the BM at the time of T cells transfer. Both CD1a-CAR and CD1a-STAb T cells were able to ablate leukemic graft in PB and BM in contrast to NT-treated mice, which showed uncontrolled leukemia progression and had to be sacrificed by week 4. To evaluate the effectiveness of the remaining effector cells in the CAR and STAb groups, mice were re-challenged with 1×106 PDX-A cells to simulate a relapse in week 5 and followed up until week 12. In the CD1a-CAR group 2/6 (33%) and 1/6 (17%) mice showed significant leukemic graft (>1% blasts) in PB and BM, respectively, whereas in the CD1a-STAb group only 1/5 (20%) mice did (figure 4B). Of note, leukemia relapses in independent mice correlated with decreased numbers of effector T cells in the PB and BM compartments (figure 4C).

Figure 4.

CD1a-STAb and CD1a-CAR T cells are effective in eliminating primary coT-ALL in long-term in vivo models. (A, D) Experimental design of in vivo cytotoxicity in NSG mice receiving intravenous coT-ALL patient-derived xenograft (PDX-A in a and PDX-B in D) cells (1×106) followed by NT, CD1a-CAR or CD1a-STAb T cells 2 weeks later (3×106 in a and 4×106 in D). In (A), disease-free mice were rechallenged with further 1×106 PDX-A cells on week 5. (B, C) Percentage of leukemic (B) and T cells (C) in PB and BM at the indicated time points in the PDX-A model. (E, F) Percentage of leukemic (E) and T cells (F) in PB and BM at the indicated time points in the PDX-B model. Numbers of mice with leukemic graft at endpoint, determined as >1% blasts, are indicated. Leukemic blasts were identified by flow cytometry as HLA-ABC+CD45+CD1a+CD3– and CD34+ (PDX-A) or CD38+ (PDX-B), and T cells as HLA-ABC+CD45+CD1a–CD3+. BM plots from B, C) and E, F) show mean±SEM of at least 5 mice per group. ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; BM, bone marrow; PB, peripheral blood; NT, non-transduced; CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; STAb, secreting T cell-redirecting antibodies.

In a second PDX model (PDX-B), with higher tumor burden at the time of T cell transfer (engraftment of ~20% in BM), we assessed the effectiveness of CD1a-STAb T cells in a more aggressive, highly active disease setting. Because of its higher aggressiveness (higher leukemic graft at week 0), mice were injected with 4×106 rather than 3×106 effector T cells. Although CD1a-CAR T cells were slightly more effective than CD1a-STAb T cells in achieving minimal residual disease negative in this aggressive PDX-B, both CD1a-CAR- and CD1a-STAb treatments were similarly effective and able to reduce leukemic burden in the BM to~0.5% by week 4 and further down (<0.02%) by week 8 (figure 4E). Similar T cell persistence levels were observed in CAR- or STAb-treated mice (figure 4F). Taken together, both strategies show robust anti-leukemic activity in long-term cutting-edge in vivo models, and slight differences in the efficacy might be attributed to differential persistence of CD1a-CAR and CD1a-STAb T cells in independent mice.

Discussion

The development of safer and efficacious immunotherapies for T-ALL remains challenging because the shared expression of target antigens between CAR T cells and T-ALL blasts leads to either CAR T cell fratricide or immunodeficiency, but also because of potential T-ALL blast contamination during the manufacturing process.15 We report the first CD1a x CD3 TCE immunotherapy strategy for the treatment of CD1a+ coT-ALL. We have engineered T cells to express soluble CD1a x CD3 TCEs which successfully bind to cell surface expressed CD1a and CD3, resulting in the specific activation of the T cells. In contrast to membrane-anchored CD1a-CAR-transduced T cells, flow cytometry analysis several subpopulations in the CD1a-TCE-transduced T cell preparation, transduced and decorated T cells (GFP+F(ab')2 +), non-transduced but decorated T cells (GFP-F(ab')2 +) and transduced but non-decorated T cells (GFP+F(ab')2 -), thus confirming the secretion of functional CD1a x CD3 TCE and their ability to decorate surrounding bystander T cells. In vitro short-term and long-term co-culture assays revealed that CD1a-STAb T cells induce a more potent and rapid cytotoxic responses than CD1a-CAR T cells. Mechanistically, the CD1a-specific interaction triggered by either CAR or STAb T cells resulted in different proinflammatory cytokine profile whereas both CD1a-CAR and CD1a-STAb T cells use the granular exocytosis pathway as a common cytolytic effector mechanism. Both contacting and non-contacting co-culture systems confirmed the bystander recruitment ability of CD1a-STAb T cells, a major biological feature providing STAb-CD1a T cells with greater in vitro tumor cell killing efficiency than CD1a-CAR T cells. Interestingly, the bystander effect mediated from CD1a-STAb T cells offers equal or superior cytotoxicity capacity than CD1a-CAR T cells without an enhanced IFNγ release, thus reducing potential cytokine release-associated side effects and offering a safer therapeutic profile than CD1a-CAR T cells. Finally, CD1a-STAb T cells are as effective as CD1a-CAR T cells in cutting-edge in vivo T-ALL cell line and PDX models. Although similar T cell persistence levels were observed in CAR- or STAb-treated mice, leukemia relapses correlated with decreased numbers of effector T cells in the PB and BM. Our data suggest that CD1a-STAb T cells could be an alternative to CD1a-CAR T cells for treating coT-ALL patients.

STAb T cells represent a next-generation T cell-redirecting immunotherapy for B-ALL30 and coT-ALL, being easily applicable to other cancers for which a suitable immunotherapy target is available.23 A major advantage for STAb T cells over CAR T cells lies in the fact that an effective treatment with STAb T cells might require lower T cell doses, which could be of particular relevance when an adequate number of mature effector T cells cannot be engineered due to either the lymphopenic status of many multi-treated patients or manufacturing constrains in patients with aggressive and hyperleukocytic relapses.29 30 In this regard, a reduction in the therapeutically effective effector T cell dose to be transferred into the patients may increase the number of patients benefiting from STAb T cell therapy, and significantly reduce the manufacturing costs.

Immune and phenotypic escape mechanisms to anti-CD19 immunotherapies have been experimentally and clinically demonstrated in B-ALL, and commonly lead to CD19-resistant leukemias with dismal prognosis.34–40 Our previous work in B-ALL showed that CD19-STAb T cell therapy could prevent CD19 downregulation and subsequent tumor escape more efficiently and at lower E:T ratios than CD19-CAR T cells.30 41 In contrast, loss of CD1a expression was not detected on cell surface of target cells co-cultured with either CD1a-CAR or CD1a-STAb T cells. These differences may be attributable to the impact that the density and biology of the targeted antigen plays on T cell activation.42 In addition, it is worth mentioning that cell fate plasticity and transcription factor-mediated lineage conversion have been extensively reported for the B cell but not the T cell compartment.43 44 The absence of evident immune escape to either CD1a-CAR or CD1a-STAb T cells may explain the very similar efficacy in controlling leukemia progression in multiple in vivo models despite the apparently more potent and rapid in vitro cytotoxic responses of CD1a-STAb T cells. In summary, CD1a-STAb T therapy could be an alternative to CD1a-CAR T in T-ALL, especially in R/R patients with leukapheresis products showing limited numbers of non-tumoral effector T cells.

jitc-2022-005333supp005.pdf (994.7KB, pdf)

Footnotes

AJ-R and NT contributed equally.

Contributors: Conception and design of the study: AJ-R, NT, PM, LA-V, DSM; acquisition of data: AJ-R, NT, AM-M, VMD, MG-P, OH, AA, PP, DSM; analysis and interpretation of data: AJ-R, NT, MLT, PM, LA-V, DSM; writing original draft: AJ-R, NT, PM, LA-V, DSM; review and editing: all authors; guarantors: PM, LA-V, DSM.

Funding: Research in LA-V laboratory is funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (PID2020-117323RB-100 and PDC2021-121711-100), and the Carlos III Health Institute (DTS20/00089), with European Regional Development Fund (FEDER) cofinancing; the Spanish Association Against Cancer (AECC PROYE19084ALVA) and the CRIS Cancer Foundation (FCRIS-2018-0042 and FCRIS-2021-0090). Research in PM laboratory is supported by CERCA/Generalitat de Catalunya and Fundació Josep Carreras-Obra Social la Caixa for core support; 'la Caixa' Foundation under the agreement LCF/PR/HR19/52160011; the European Research Council grant (ERC-PoC-957466); the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (PID2019-108160RB-I00); and the ISCIII-RICORS within the Next Generation EU program (plan de Recuperación, Transformación y Resilencia). MLT is supported by Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (PID2019-105623RB-I00) and the Spanish Association Against Cancer (CICPF18030TORI). PP is supported by Carlos III Health Institute (PI21-01834), with FEDER cofinancing and Fundación Ramón Areces. NT was supported by an FPU PhD fellowship from Spain's Ministerio de Universidades (FPU19/00039). OH was supported by an industrial PhD fellowship from the Comunidad de Madrid (IND2020/BMD-17668). LD-A was supported by a Rio Hortega fellowship from the Carlos III Health Institute (CM20/00004). VMD is supported by the Torres Quevedo subprogram of the State Research Agency of the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (Ref. PTQ2020-011056). DSM is partially founded by a Sara Borrell fellowship from Carlos III Health Institute (CD19/00013).

Competing interests: LA-V is cofounder of Leadartis, a spin-off focused on unrelated interest. PM is cofounder of OneChain Immunotherapeutics, a spin-off company from the Josep Carreras Leukemia Research Institute. VMC is current employee of One Chain Immunotherapeutics.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

All samples were obtained after written informed consent from the donors and all studies were performed according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Committees of the hospitals and research centers involved (HCB/2019/0450, HCB/2018/0030).

References

- 1. Karrman K, Johansson B. Pediatric T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2017;56:89–116. 10.1002/gcc.22416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Belver L, Ferrando A. The genetics and mechanisms of T cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nat Rev Cancer 2016;16:494–507. 10.1038/nrc.2016.63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Liu Y, Easton J, Shao Y, et al. The genomic landscape of pediatric and young adult T-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet 2017;49:1211–8. 10.1038/ng.3909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hunger SP, Mullighan CG. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia in children. N Engl J Med 2015;373:1541–52. 10.1056/NEJMra1400972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Litzow MR, Ferrando AA. How I treat T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia in adults. Blood 2015;126:833–41. 10.1182/blood-2014-10-551895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pocock R, Farah N, Richardson SE, et al. Current and emerging therapeutic approaches for T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Br J Haematol 2021;194:28–43. 10.1111/bjh.17310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Waldman AD, Fritz JM, Lenardo MJ. A guide to cancer immunotherapy: from T cell basic science to clinical practice. Nat Rev Immunol 2020;20:651–68. 10.1038/s41577-020-0306-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Couzin-Frankel J. Breakthrough of the year 2013. Cancer immunotherapy. Science 2013;342:1432–3. 10.1126/science.342.6165.1432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Maude SL, Frey N, Shaw PA, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells for sustained remissions in leukemia. N Engl J Med 2014;371:1507–17. 10.1056/NEJMoa1407222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brentjens RJ, Davila ML, Riviere I, et al. CD19-targeted T cells rapidly induce molecular remissions in adults with chemotherapy-refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Sci Transl Med 2013;5:177ra38. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gardner RA, Finney O, Annesley C, et al. Intent-To-Treat leukemia remission by CD19 CAR T cells of defined formulation and dose in children and young adults. Blood 2017;129:3322–31. 10.1182/blood-2017-02-769208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fry TJ, Shah NN, Orentas RJ, et al. CD22-targeted CAR T cells induce remission in B-ALL that is naive or resistant to CD19-targeted CAR immunotherapy. Nat Med 2018;24:20–8. 10.1038/nm.4441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ortíz-Maldonado V, Rives S, Castellà M, et al. CART19-BE-01: A Multicenter Trial of ARI-0001 Cell Therapy in Patients with CD19+ Relapsed/Refractory Malignancies. Mol Ther 2021;29:636–44. 10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.09.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Scherer LD, Brenner MK, Mamonkin M. Chimeric antigen receptors for T-cell malignancies. Front Oncol 2019;9:126. 10.3389/fonc.2019.00126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Alcantara M, Tesio M, June CH, et al. Car T-cells for T-cell malignancies: challenges in distinguishing between therapeutic, normal, and neoplastic T-cells. Leukemia 2018;32:2307–15. 10.1038/s41375-018-0285-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gomes-Silva D, Srinivasan M, Sharma S, et al. CD7-edited T cells expressing a CD7-specific CAR for the therapy of T-cell malignancies. Blood 2017;130:285–96. 10.1182/blood-2017-01-761320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Png YT, Vinanica N, Kamiya T, et al. Blockade of CD7 expression in T cells for effective chimeric antigen receptor targeting of T-cell malignancies. Blood Adv 2017;1:2348–60. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2017009928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mamonkin M, Rouce RH, Tashiro H, et al. A T-cell-directed chimeric antigen receptor for the selective treatment of T-cell malignancies. Blood 2015;126:983–92. 10.1182/blood-2015-02-629527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rasaiyaah J, Georgiadis C, Preece R, et al. TCRαβ/CD3 disruption enables CD3-specific antileukemic T cell immunotherapy. JCI Insight 2018;3:e99442. 10.1172/jci.insight.99442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Maciocia PM, Wawrzyniecka PA, Philip B, et al. Targeting the T cell receptor β-chain constant region for immunotherapy of T cell malignancies. Nat Med 2017;23:1416–23. 10.1038/nm.4444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pan J, Tan Y, Wang G, et al. Donor-Derived CD7 chimeric antigen receptor T cells for T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: first-in-human, phase I trial. J Clin Oncol 2021;39:3340–51. 10.1200/JCO.21.00389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sánchez-Martínez D, Baroni ML, Gutierrez-Agüera F, et al. Fratricide-resistant CD1a-specific CAR T cells for the treatment of cortical T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 2019;133:2291–304. 10.1182/blood-2018-10-882944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Blanco B, Compte M, Lykkemark S, et al. T Cell-Redirecting Strategies to 'STAb' Tumors: Beyond CARs and Bispecific Antibodies. Trends Immunol 2019;40:243–57. 10.1016/j.it.2019.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Blanco B, Holliger P, Vile RG, et al. Induction of human T lymphocyte cytotoxicity and inhibition of tumor growth by tumor-specific diabody-based molecules secreted from gene-modified bystander cells. J Immunol 2003;171:1070–7. 10.4049/jimmunol.171.2.1070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Compte M, Blanco B, Serrano F, et al. Inhibition of tumor growth in vivo by in situ secretion of bispecific anti-CEA X anti-CD3 diabodies from lentivirally transduced human lymphocytes. Cancer Gene Ther 2007;14:380–8. 10.1038/sj.cgt.7701021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mølgaard K, Compte M, Nuñez-Prado N, et al. Balanced secretion of anti-CEA × anti-CD3 diabody chains using the 2A self-cleaving peptide maximizes diabody assembly and tumor-specific cytotoxicity. Gene Ther 2017;24:208–14. 10.1038/gt.2017.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Compte M, Alvarez-Cienfuegos A, Nuñez-Prado N, et al. Functional comparison of single-chain and two-chain anti-CD3-based bispecific antibodies in gene immunotherapy applications. Oncoimmunology 2014;3:e28810. 10.4161/onci.28810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Velasquez MP, Torres D, Iwahori K, et al. T cells expressing CD19-specific Engager molecules for the immunotherapy of CD19-positive malignancies. Sci Rep 2016;6:27130. 10.1038/srep27130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Liu X, Barrett DM, Jiang S, et al. Improved anti-leukemia activities of adoptively transferred T cells expressing bispecific T-cell engager in mice. Blood Cancer J 2016;6:e430. 10.1038/bcj.2016.38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Blanco B, Ramírez-Fernández Ángel, Bueno C, et al. Overcoming CAR-mediated CD19 downmodulation and leukemia relapse with T lymphocytes secreting anti-CD19 T-cell Engagers. Cancer Immunol Res 2022;10:498–511. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-21-0853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Haryadi R, Ho S, Kok YJ, et al. Optimization of heavy chain and light chain signal peptides for high level expression of therapeutic antibodies in CHO cells. PLoS One 2015;10:e0116878. 10.1371/journal.pone.0116878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sánchez-Martínez D, Gutiérrez-Agüera F, Romecin P, et al. Enforced sialyl-Lewis-X (SLex) display in E-selectin ligands by exofucosylation is dispensable for CD19-CAR T-cell activity and bone marrow homing. Clin Transl Med 2021;11:e280. 10.1002/ctm2.280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sánchez-Martínez D, Azaceta G, Muntasell A, et al. Human NK cells activated by EBV+ lymphoblastoid cells overcome anti-apoptotic mechanisms of drug resistance in haematological cancer cells. Oncoimmunology 2015;4:e991613. 10.4161/2162402X.2014.991613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bagashev A, Sotillo E, Tang C-HA, et al. Cd19 alterations emerging after CD19-Directed immunotherapy cause retention of the misfolded protein in the endoplasmic reticulum. Mol Cell Biol 2018;38:e00383–18. 10.1128/MCB.00383-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Braig F, Brandt A, Goebeler M, et al. Resistance to anti-CD19/CD3 bite in acute lymphoblastic leukemia may be mediated by disrupted CD19 membrane trafficking. Blood 2017;129:100–4. 10.1182/blood-2016-05-718395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fischer J, Paret C, El Malki K, et al. Cd19 isoforms enabling resistance to CART-19 immunotherapy are expressed in B-ALL patients at initial diagnosis. J Immunother 2017;40:187–95. 10.1097/CJI.0000000000000169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gardner R, Wu D, Cherian S, et al. Acquisition of a CD19-negative myeloid phenotype allows immune escape of MLL-rearranged B-ALL from CD19 CAR-T-cell therapy. Blood 2016;127:2406–10. 10.1182/blood-2015-08-665547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jacoby E, Nguyen SM, Fountaine TJ, et al. CD19 CAR immune pressure induces B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia lineage switch exposing inherent leukaemic plasticity. Nat Commun 2016;7:12320. 10.1038/ncomms12320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Orlando EJ, Han X, Tribouley C, et al. Genetic mechanisms of target antigen loss in CAR19 therapy of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Med 2018;24:1504–6. 10.1038/s41591-018-0146-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sotillo E, Barrett DM, Black KL, et al. Convergence of acquired mutations and alternative splicing of CD19 enables resistance to CART-19 immunotherapy. Cancer Discov 2015;5:1282–95. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-1020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ramírez-Fernández Ángel, Aguilar-Sopeña Óscar, Díez-Alonso L, et al. Synapse topology and downmodulation events determine the functional outcome of anti-CD19 T cell-redirecting strategies. Oncoimmunology 2022;11:2054106. 10.1080/2162402X.2022.2054106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Majzner RG, Mackall CL. Tumor antigen escape from CAR T-cell therapy. Cancer Discov 2018;8:1219–26. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-0442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Laiosa CV, Stadtfeld M, Graf T. Determinants of lymphoid-myeloid lineage diversification. Annu Rev Immunol 2006;24:705–38. 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Graf T, Enver T. Forcing cells to change lineages. Nature 2009;462:587–94. 10.1038/nature08533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

jitc-2022-005333supp001.pdf (127.6KB, pdf)

jitc-2022-005333supp002.pdf (290.5KB, pdf)

jitc-2022-005333supp003.pdf (211.3KB, pdf)

jitc-2022-005333supp004.pdf (1.5MB, pdf)

jitc-2022-005333supp005.pdf (994.7KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request.