Abstract

Background

Intratumoral administration of V937, a bioselected, genetically unmodified coxsackievirus A21, has previously demonstrated antitumor activity in patients with advanced melanoma as monotherapy and in combination with the programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) antibody pembrolizumab. We report results from an open-label, single-arm, phase 1b study (NCT02307149) evaluating V937 plus the cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 inhibitor ipilimumab in patients with advanced melanoma.

Methods

Adult patients (aged ≥18 years) with histologically confirmed metastatic or unresectable stage IIIB/C or IV melanoma received intratumoral V937 on days 1, 3, 5, 8, and 22 and every 3 weeks (Q3W) thereafter for up to 19 sets of injections plus intravenous ipilimumab 3 mg/kg Q3W administered for four doses starting on day 22. Imaging was performed at screening, on days 43 and 106 and every 6 weeks thereafter; response was assessed by immune-related response criteria per investigator assessment. Primary endpoints were safety in all treated patients and objective response rate (ORR) in all treated patients and in patients with disease that progressed on prior anti-PD-1 therapy.

Results

Fifty patients were enrolled and treated. ORR was 30% (95% CI 18% to 45%) among all treated patients, 47% (95% CI 23% to 72%) among patients who had not received prior anti-PD-1 therapy, and 21% (95% CI 9% to 39%) among patients who had experienced disease progression on prior anti-PD-1 therapy. Tumor regression occurred in injected and non-injected lesions. Median immune-related progression-free survival was 6.2 months (95% CI 3.5 to 9.0 months), and median overall survival was 45.1 months (95% CI 28.3 months to not reached). The most common treatment-related adverse events (AEs) were pruritus (n=25, 50%), fatigue (n=22, 44%), and diarrhea (n=16, 32%). There were no V937-related dose-limiting toxicities and no treatment-related grade 5 AEs. Treatment-related grade 3 or 4 AEs, all of which were considered related to ipilimumab, occurred in 14% of patients (most commonly dehydration, diarrhea, and hepatotoxicity in 4% each).

Conclusions

Responses associated with intratumoral V937 plus ipilimumab were robust, including in the subgroup of patients who had experienced disease progression on prior anti-PD-1 therapy. Toxicities were manageable and consistent with those of the individual monotherapies.

Keywords: Immunotherapy, Melanoma, Combined Modality Therapy, Oncolytic Viruses

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC.

Intratumoral administration of V937, a bioselected, genetically unmodified coxsackievirus A21, has previously demonstrated antitumor activity in patients with advanced melanoma as monotherapy and in combination with the programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) antibody pembrolizumab

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

We report results from an open-label, single-arm, phase 1b study evaluating intratumoral V937 (a bioselected, genetically unmodified coxsackievirus A21) plus intravenous ipilimumab (a cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 inhibitor) in patients with advanced melanoma.

Responses associated with intratumoral V937 plus ipilimumab were robust, including in the subgroup of patients who had experienced disease progression on prior anti-PD-1 therapy.

Objective response rate was 30% (95% CI 18% to 45%) among all treated patients, 47% (95% CI 23% to 72%) among patients who had not received prior anti-PD-1 therapy, and 21% (95% CI 9% to 39%) among patients who had experienced disease progression on prior anti-PD-1 therapy.

Toxicities were manageable and consistent with those of the individual monotherapies.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

In this phase 1b study, combination therapy with the oncolytic virus V937 administered intratumorally plus ipilimumab had manageable toxicity, and responses were robust and durable in patients with advanced melanoma, including patients with melanoma progression after anti-PD-1 therapy

Introduction

Oncolytic viruses are an emerging class of anticancer therapeutics that function both by killing tumor cells directly (virus-mediated oncolysis) and by inducing systemic antitumor immune responses.1 Talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC), a genetically engineered, live attenuated herpes simplex virus 1, became the first such agent to be approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of unresectable melanoma recurrent after initial surgery2 based on durable responses demonstrated in a phase 3 study.3 Coxsackievirus is a type of non-enveloped, single-stranded RNA enterovirus that typically causes asymptomatic infections or common cold-like symptoms.4 Coxsackievirus undergoes cytosolic replication without a DNA phase and is not associated with risk of insertional mutagenesis during infection.4 As such, it does not require genetic modification for safety.

The oncolytic virus V937 (previously known as Cavatak and CVA21) is a bioselected and genetically unmodified coxsackievirus A21.5 It gains cellular entry via intercellular adhesion molecule 1 and decay-accelerating factor receptors, which are overexpressed by certain cancer cells, including melanoma.6–8 In a phase 2 study of patients with advanced melanoma, intratumoral V937 monotherapy demonstrated systemic antitumor activity with reductions in the size of both injected and non-injected (eg, liver and lung) lesions.5 The unconfirmed objective response rate (ORR; complete response (CR) or partial response (PR)) was 38.6%, and the confirmed ORR was 28.1% based on immune-related Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (irRECIST); a response lasting ≥6 months was observed in 21.1% of patients. Treatment was well tolerated in the study, with no grade ≥3 treatment-related adverse events (AEs).5

Oncolytic viruses have been shown to alter the tumor microenvironment (eg, increased CD8+ T cells and programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression, reduced suppressor T cells),9 10 which provides the rationale for combination therapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors. In a phase 1b study of patients with advanced melanoma, the combination of intratumoral V937 plus the programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) antibody pembrolizumab resulted in a confirmed ORR of 47% per irRECIST and a response lasting ≥12 months in 74% of patients.11 No dose-limiting toxicity (DLT) occurred, and no new safety signals were identified. Other combinations of V937 with immune checkpoint inhibitors may have the potential to result in improved outcomes. Here, we report results from the phase 1b Melanoma Intra-Tumoral Cavatak and Ipilimumab (MITCI) study (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT02307149), which evaluated the combination of V937 plus the cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 antibody ipilimumab in patients with metastatic or unresectable stage IIIB/C or IV melanoma. At the time this study opened in 2015, the use of PD-1 inhibitors was just beginning to transform the care of patients with advanced melanoma, and the concept of anti–PD-1-refractory melanoma was not established. This trial was modified to include a cohort of patients with melanoma progression after anti-PD-1 therapy when there was greater appreciation that anti–PD-1-refractory melanoma represented a significant proportion of patients and for whom prognosis is poor12 and responses to second-line therapies are infrequent.13 14

Methods

Study design and patients

MITCI was an open-label, single-arm, phase 1b study. Eligible patients were adults (aged ≥18 years) with histologically confirmed metastatic or unresectable stage IIIB/C or IV melanoma per American Joint Committee on Cancer 7th edition, an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 or 1, ≥1 cutaneous or subcutaneous tumor (0.5–5.0 cm in longest diameter) or a palpable lymph node amenable to intratumoral injection, and ≤3 visceral metastases (excluding pulmonary lesions) with no lesions >3.0 cm. A protocol amendment was implemented approximately 2.5 years after study initiation requiring patients to have disease that progressed, per RECIST v1.1, on prior anti-PD-1 therapy. Exclusion criteria included prior treatment with chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or immunotherapy within 28 days before initiation of study treatment, previous receipt of V937 or ipilimumab, and untreated brain metastases. A complete list of inclusion and exclusion criteria can be found in the study protocol (see online supplemental file 2).

jitc-2022-005224supp002.pdf (1.1MB, pdf)

Treatment

All patients were treated with the combination of V937 plus ipilimumab. On days 1, 3, 5, 8, and 22 and every 3 weeks thereafter, patients received intratumoral V937 at a maximum total dose of 3×108 TCID50 (50% tissue culture infectious dose) in a volume of up to 4.0 mL. At each injection visit, multiple lesions were injected, starting with the largest lesion(s), using a volume of 2.0 mL for tumors >25 mm in diameter, 1.0 mL for tumors 15 to 25 mm in diameter, and 0.5 mL for tumors 5 to <15 mm in diameter. Injected lesions that decreased to <5 mm in diameter were injected with 0.1 mL of V937 until complete resolution.

Patients with clinical benefit continued treatment with V937 up to a maximum of 19 sets of injections or until confirmed disease progression, CR, or unacceptable toxicity. V937 dose modifications were not permitted. Patients who stopped treatment with V937 could receive any remaining planned ipilimumab doses as clinically indicated.

Ipilimumab was administered intravenously at 3 mg/kg on days 22, 43, 64, and 85, which is the standard dose and schedule for this agent.15 Patients who discontinued or delayed ipilimumab dosing could continue to receive planned V937 doses.

Assessments and endpoints

Safety was assessed based on the occurrence of DLTs and AEs. DLTs were defined as any grade ≥3 V937-related toxicities with onset on or before day 85; an exception was that lymphopenia was not considered a DLT. If a DLT occurred in two of the first six patients treated, the study was to be terminated. If no DLTs occurred or if the proportion of DLTs was <30% of the patients enrolled, study accrual was to continue. The accumulated safety data after 6, 12, and 18 patients had been treated and followed through at least day 85 were reviewed by the sponsor and investigators to identify the rate of DLTs and determine whether enrollment should be continued from a safety perspective. AEs were reported from the time of initiation of study treatment through 30 days after cessation of study treatment and were graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, V.4.03.

Disease status was assessed at screening, on days 43 and 106, and every 6 weeks thereafter by CT or MRI scans. Responses were based on immune-related response criteria16 17 per investigator assessment.

The primary endpoints were safety in all treated patients and ORR (best response of CR or PR) in all treated patients and in patients with disease that progressed on prior anti-PD-1 therapy assessed using immune-related response criteria (modified WHO criteria). Secondary endpoints included time to initial response (TTR), durable response rate (DRR; defined as the percentage of patients with best response of CR or PR lasting ≥6 months), response of injected and non-injected melanoma lesions, progression-free survival (PFS), and overall survival (OS). The disease control rate (best response of CR, PR, or stable disease (<50% decrease to <25% increase in index lesion and new measurable lesions)) was also reported.

Statistical analyses

A sample size of 26 patients with disease that progressed on prior anti-PD-1 therapy was estimated to provide 90% power to test the null hypothesis (11% ORR) versus the alternative hypothesis (31% ORR) for the primary efficacy endpoint using a one-sided test at a significance level of 0.10. The ORR threshold of 11% was selected based on a previous study of ipilimumab in patients with advanced melanoma.18

Safety and efficacy analyses were conducted in all patients who received ≥1 dose of study treatment (V937 and/or ipilimumab). Data were analyzed separately for patients with disease that progressed on prior anti-PD-1 therapy and patients who were not previously treated with anti-PD-1 therapy. Two-sided exact 95% CIs were provided for ORR and DRR. PFS and OS were analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method. Best per cent change from baseline in target injected and non-injected lesions were analyzed using a double waterfall plot.

Results

Patients

The study was conducted between May 5, 2015 and November 5, 2019, at 11 sites in the USA. At the cut-off date (February 21, 2020), 50 patients were enrolled and received ≥1 dose of study treatment. Patient demographics and baseline characteristics are shown in table 1 for all treated patients and based on previous receipt of anti-PD-1 therapy. Most patients (62%) were men, and median age was 64.5 years. The majority of patients (72%) had stage IV disease, with a median baseline tumor burden of 1479 mm2 (range: 209–18 218 mm2). BRAF mutations were detected in 34% of the population. Most patients (80%) had received previous systemic therapy (≥3 lines in 32%). Patients with disease that progressed on prior anti-PD-1 therapy (60%) had disease that was more heavily pretreated with systemic therapy than patients who were not previously treated with anti-PD-1 therapy (34%) (≥3 lines in 45% vs 6%, respectively).

Table 1.

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics*

| Characteristic | All treated patients N=50 |

Progressed on prior anti-PD-1 therapy n=33 |

No prior anti-PD-1 therapy n=17 |

| Age, median (range), year | 64.5 (28‒88) | 65.0 (28‒84) | 64.0 (35‒88) |

| Sex | |||

| Men | 31 (62) | 22 (67) | 9 (53) |

| Women | 19 (38) | 11 (33) | 8 (47) |

| White | 50 (100) | 33 (100) | 17 (100) |

| ECOG PS | |||

| 0 | 34 (68) | 21 (64) | 13 (76) |

| 1 | 16 (32) | 12 (36) | 4 (24) |

| Stage | |||

| III | 14 (28) | 7 (21) | 7 (41) |

| IVM1a | 7 (14) | 4 (12) | 3 (18) |

| IVM1b | 6 (12) | 4 (12) | 2 (12) |

| IVM1c(1)† | 12 (24) | 11 (33) | 1 (6) |

| IVM1c(2)‡ | 11 (22) | 7 (21) | 4 (24) |

| Baseline tumor burden, median (range), mm2 | 1479 (209‒18,218) | 1425 (225‒18,218) | 2750 (209‒7348) |

| BRAF mutation status | |||

| Mutant | 17 (34) | 12 (36) | 5 (29) |

| Wild-type | 26 (52) | 18 (55) | 8 (47) |

| Unknown | 7 (14) | 3 (9) | 4 (24) |

| Received any prior systemic therapy | 40 (80) | 33 (100) | 7 (41) |

| 1 line | 16 (32) | 10 (30) | 6 (35) |

| 2 lines | 8 (16) | 8 (24) | 0 |

| ≥3 lines | 16 (32) | 15 (45) | 1 (6) |

| Select prior pharmacologic therapy§ | |||

| Chemotherapy | 8 (16) | 7 (21) | 1 (6) |

| Hormone therapy | 1 (2) | 1 (3) | 0 |

| Immunotherapy | 29 (58) | 27 (82) | 2 (12) |

| Targeted therapy | 4 (8) | 4 (12) | 0 |

*Data are presented as n (%), unless otherwise noted.

†Metastases to all other visceral metastases with a normal lactate dehydrogenase.

‡Any distant metastases with an elevated lactate dehydrogenase.

§Patients could have been counted in more than one row.

anti-PD-1, anti-programmed death 1; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status.

The median numbers of intratumoral V937 injections and ipilimumab infusions were 9 (range: 5‒19) and 4 (range: 1‒4), respectively. The median cumulative dose of V937 administered was 1.5×109 (range: 4.31×108 to 5.54×109) TCID50. All patients had stopped study treatment as of the cut-off date (online supplemental figure S1); 60% of patients had discontinued because of disease progression and 22% had completed the study.

jitc-2022-005224supp001.pdf (34KB, pdf)

Safety

Treatment-related AEs, as assessed by the investigator, are summarized in table 2. No DLTs or treatment-related grade 5 AEs occurred in the overall population.

Table 2.

Treatment-related AEs*†

| All treated patients, N=50 | Progressed on prior anti-PD-1 therapy, n=33 | No prior anti-PD-1 therapy, n=17 | |

| Treatment-related AEs | 47 (94) | 30 (91) | 17 (100) |

| Grade ≥3 V937-related AEs | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Grade 3 or 4 ipilimumab-related AEsठ| 7 (14) | 4 (12) | 3 (18) |

| Treatment-related AEs occurring in ≥10% of all treated patients | Any grade | Grade 3 or 4 | Any grade | Grade 3 or 4 | Any grade | Grade 3 or 4 |

| Pruritus | 25 (50) | 1 (2) | 17 (52) | 0 | 8 (47) | 1 (6) |

| Fatigue | 22 (44) | 1 (2) | 15 (45) | 0 | 7 (41) | 1 (6) |

| Diarrhea | 16 (32) | 2 (4) | 13 (39) | 2 (6) | 3 (18) | 0 |

| Nausea | 11 (22) | 0 | 9 (27) | 0 | 2 (12) | 0 |

| Rash | 10 (20) | 0 | 5 (15) | 0 | 5 (29) | 0 |

| Pyrexia | 8 (16) | 0 | 5 (15) | 0 | 3 (18) | 0 |

| Chills | 7 (14) | 0 | 6 (18) | 0 | 1 (6) | 0 |

| Influenza-like illness | 7 (14) | 0 | 6 (18) | 0 | 1 (6) | 0 |

| Decreased appetite | 6 (12) | 0 | 5 (15) | 0 | 1 (6) | 0 |

| Injection site reaction | 6 (12) | 0 | 3 (9) | 0 | 3 (18) | 0 |

| Transaminase increase | 6 (12) | 0 | 5 (15) | 0 | 1 (6) | 0 |

| Headache | 5 (10) | 0 | 5 (15) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Injection site pain | 5 (10) | 0 | 2 (6) | 0 | 3 (18) | 0 |

*Data are presented as n (%).

†Treatment-related AEs were those events with a V937 or ipilimumab relationship of possibly, probably, or definitely.

‡There were no grade 5 treatment-related AEs.

§The most common grade 3 and 4 treatment-related AEs were dehydration, diarrhea, and hepatotoxicity (two patients (4%) each).

AE, adverse event; anti-PD-1, antiprogrammed death 1.

Thirty-seven patients (74%) experienced ≥1 investigator-assessed V937-related AE; no patients had grade 3 or 4 V937-related AEs. Although attribution of toxicity to an individual component of a combination therapy is difficult, two patients (4%) discontinued V937 because of grade 2 pruritus (assessed by investigator as probably related to V937 and possibly related to ipilimumab) and grade 2 adrenal insufficiency (assessed by investigator as possibly related to V937 and probably related to ipilimumab). One patient (2%) had treatment with V937 interrupted because of an investigator-assessed V937-related AE (grade 1 fever). Six patients had an injection site reaction, which was deemed related to V937 treatment, and five patients had V937-related injection site pain.

Forty-two patients (84%) experienced ≥1 investigator-assessed ipilimumab-related AE. Seven patients (14%) had grade 3 or 4 ipilimumab-related AEs; these patients experienced dehydration, diarrhea, and hepatotoxicity (two patients (4%) each), hyperglycemia, hypokalemia, hyponatremia, colitis, fatigue, and pruritus (one patient (2% each)). Three patients (6%) discontinued ipilimumab because of grade 3 hepatotoxicity, grade 1 or 2 transaminitis, and grade 3 diarrhea (all investigator-assessed as related to ipilimumab). Eleven patients (22%) had treatment with ipilimumab interrupted because of investigator-assessed ipilimumab-related AEs, the most common of which was grade 1 or 2 diarrhea in 3 patients (6%).

Two patients (4%) died because of events (central nervous system hemorrhage (duration: 11 days), hepatic failure (duration: 29 days)) that were unrelated to treatment. Safety results were generally consistent regardless of prior receipt of anti-PD-1 therapy (table 2).

Efficacy

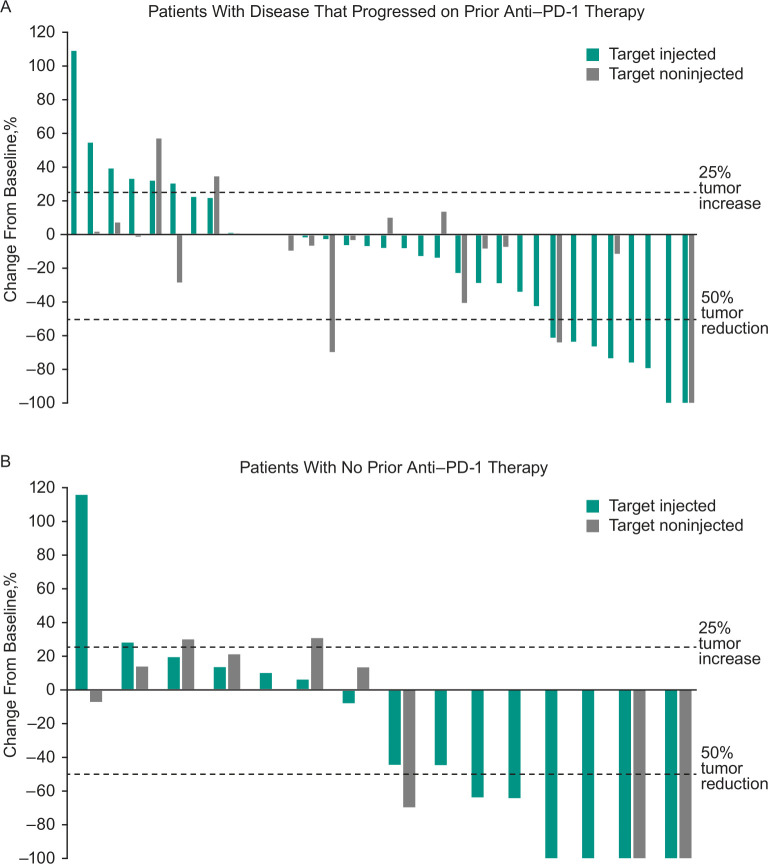

Across all treated patients, ORR based on investigator assessment per immune-related response criteria was 30% (95% CI 18% to 45%), with five patients experiencing CR and 10 patients experiencing PR (table 3). An additional 17 patients had stable disease for a disease control rate (CR, PR, or SD) of 64%. ORR was 21% (95% CI 9% to 39%) in patients who progressed on prior anti-PD-1 therapy and 47% (95% CI 23% to 72%) in patients with no prior anti-PD-1 therapy. In all treated patients, median TTR was 3.4 months (range: 0.7–5.1 months) among the 15 responders. Median duration of response was 8.8 months (95% CI 5.9 to 8.8 months), and the DRR (ie, the rate of CR or PR lasting ≥6 months) was 14% (95% CI 6% to 27%). Reductions from baseline in tumor burden were observed in most patients. Reductions in tumor size were observed in both target injected and non-injected lesions in patients who progressed on prior anti-PD-1 therapy and in patients with no prior anti-PD-1 therapy (figure 1).

Table 3.

Immune-related responses*

| All treated patients N=50 |

Progressed on prior anti-PD-1 therapy n=33 |

No prior anti-PD-1 therapy n=17 |

|

| Objective response rate, % (95% CI) | 30 (18 to 45) | 21 (9 to 39) | 47 (23 to 72) |

| Complete response, n (%) | 5 (10) | 2 (6) | 3 (18) |

| Partial response, n (%) | 10 (20) | 5 (15) | 5 (29) |

| Stable disease, n (%) | 17 (34) | 15 (45) | 2 (12) |

| Progressive disease, n (%) | 16 (32) | 11 (33) | 5 (29) |

| Not evaluable, n (%) | 2 (4) | 0 | 2 (12) |

| Time to initial response, median (range), mo | 3.4 (0.7‒5.1) | 3.5 (3.2‒5.1) | 3.4 (0.7‒3.4) |

| Disease control rate†, n (%) | 32 (64) | 22 (67) | 10 (59) |

| Durable response rate‡, % (95% CI) | 14 (6 to 27) | 12 (3 to 28) | 18 (4 to 43) |

| Duration of response | |||

| Median (95% CI), months | 8.8 (5.9 to 8.8) | 8.8 (5.9 to 8.8) | NR (4.9 to NR) |

| ≥6 months, % | 81 | 80 | 86 |

*Data analyzed in the safety analysis set; responses are based on investigator assessment per immune-related response criteria.

†Complete response+partial response+stable disease.

‡Response lasting ≥6 months.

anti-PD-1, antiprogrammed death 1; NR, not reached.

Figure 1.

Best percentage change from baseline in target injected and non-injected lesions among (A) patients who had progressed on prior anti-PD-1 therapy and (B) patients with no prior anti-PD-1 therapy. Data include patients with ≥1 postbaseline tumor assessment after start of study treatment. anti-PD-1, antiprogrammed cell death 1.

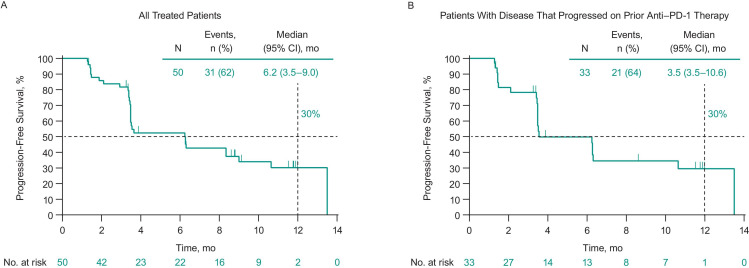

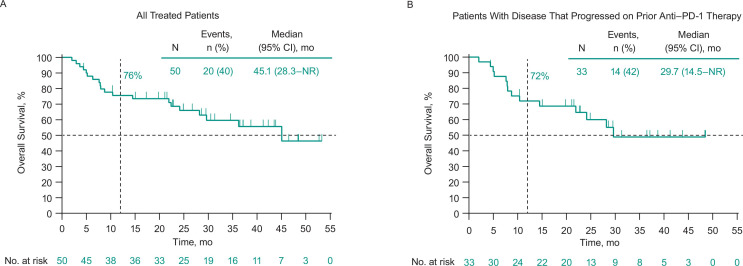

Thirty-one patients (62%) experienced disease progression or death. Median PFS in all treated patients was 6.2 months (95% CI 3.5 to 9.0 months), and the 6-month and 1-year PFS rates were 52% and 30%, respectively (figure 2A). Twenty patients (40%) died. Median OS was 45.1 months (95% CI 28.3 months to not reached), and the 6-month and 1-year OS rates were 88% and 76%, respectively (figure 3A).

Figure 2.

Progression-free survival based on investigator assessment per immune-related response criteria among (A) all treated patients and (B) patients who had progressed on prior anti-PD-1 therapy. Median progression-free survival was 8.3 months (95% CI 3.4 months to not reached) in patients with no prior anti-PD-1 therapy. anti-PD-1, antiprogrammed death 1.

Figure 3.

Overall survival among (A) all treated patients and (B) patients who had progressed on prior anti-PD-1 therapy. Median overall survival was 45.1 months (95% CI 22.4 months to not reached) in patients with no prior anti-PD-1 therapy. anti-PD-1, antiprogrammed death 1; NR, not reached.

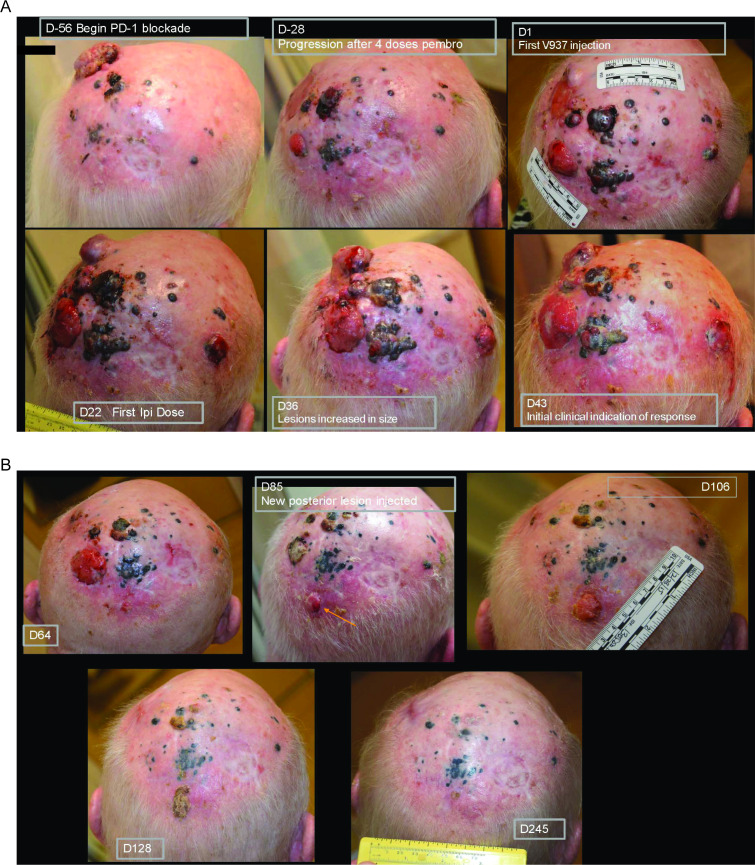

In patients with disease that progressed on prior anti-PD-1 therapy, ORR was 21% (95% CI 9% to 39%; table 3). Median PFS in these patients was 3.5 months (95% CI 3.5 to 10.6 months), and the 6-month and 1-year PFS rates were 50% and 30%, respectively (figure 2B). Median OS was 29.7 months (95% CI 14.5 to not reached), and the 6-month and 1-year OS rates were 88% and 72%, respectively (figure 3B). Photos from a representative patient with disease that progressed on prior anti-PD-1 therapy but experienced a durable response in our study are shown in figure 4.

Figure 4.

Photos of a representative patient who had progressed on prior anti-PD-1 therapy but experienced a complete response after treatment with intratumoral V937 plus ipilimumab. This patient was resistant to pembrolizumab and had an area of isolated progression (day −28). He was subsequently started on combination therapy with intratumoral V937 plus ipilimumab. After an initial increase in lesion size (day 36), a durable response was achieved. On day 85, a new lesion developed while on therapy (see orange arrow). As injections were no longer needed at the other sites, the new lesion was injected starting on day 85 and then completely regressed. anti-PD-1, antiprogrammed death 1; D, day.

Discussion

In this phase 1b study, combination therapy with the oncolytic virus V937 administered intratumorally plus ipilimumab had manageable toxicity, and responses were robust and durable in patients with advanced melanoma, including patients with melanoma progression after anti-PD-1 therapy. Responses seen in non-injected metastases provide evidence of probable systemic immune activation.

The safety profile of intratumoral V937 plus ipilimumab in our study was consistent with that anticipated for the individual treatment components. In previous studies of patients with advanced melanoma, the most common treatment-related AEs were injection site pain, fatigue, and chills with intratumoral V937 monotherapy5 and pruritus, diarrhea, rash, and fatigue with ipilimumab monotherapy.19 20 Notably, the rates of V937 injection site pain and injection site reactions in the current analysis were lower than a prior report of intratumoral V937 monotherapy in patients with melanoma.5

Ipilimumab-related AEs are well characterized and generally tolerated with prompt detection and appropriate management.21 Importantly, no grade ≥3 V937-related AEs occurred with intratumoral V937 monotherapy in a phase 2 study5 or in combination with ipilimumab in our study. The rate of grade 3–5 ipilimumab-related AEs was lower with combination therapy in our study (14%) than with ipilimumab monotherapy in phase 3 studies (20%–27%),19 20 possibly due to differences in trial designs and patient populations. Taken together, these data suggest good tolerability with no added toxicity from combination therapy. The safety profile was similar irrespective of whether patients had received prior anti-PD-1 therapy.

Few patients with advanced melanoma respond to standard second-line therapies after progression on anti-PD-1 therapy. In our study, combination therapy resulted in an ORR of 21% in this subgroup of patients, which is higher than the rates reported with ipilimumab monotherapy in this population (10%–13%).13 14 No comparable data exist for intratumoral V937 monotherapy because the only other study that has been published did not include any patients who previously received PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitors.5 Efficacy was also observed in the subgroup of patients who were not previously treated with anti-PD-1 therapy; as expected, ORR was higher in patients who were not previously treated with anti-PD-1 therapy than in patients with disease that progressed on prior anti-PD-1 therapy. The ORR was 47% in patients who were not previously treated with anti-PD-1 therapy, which compares favorably with the ORRs of intratumoral V937 monotherapy (28%)5 and ipilimumab monotherapy (12%)19 in this population and suggests at least an additive benefit with the combination.

In our study, we observed responses in both injected and non-injected melanoma lesions (non-injected lesions were not a study entry requirement). The antitumor activity of V937 in non-injected lesions (lung and liver metastases) has been reported in a previous phase 2 study of intratumoral V937 monotherapy in patients with advanced melanoma,5 but it is not possible to determine in the current study whether this effect was attributable to V937 and/or ipilimumab given that all patients received both agents.

Our results are similar to those observed with the oncolytic virus T-VEC. In a phase 2 study, intratumoral T-VEC plus ipilimumab was associated with an ORR of 39% in patients with advanced melanoma, compared with 18% with ipilimumab monotherapy, and no additional safety concerns were observed with the combination.22 Although differences in study designs and patient populations between that study and ours preclude direct comparisons (eg, only 27% received prior anticancer therapy (<3% PD-1 inhibitors) in the T-VEC study versus 80% in our study (66% PD-1 inhibitors)), the overall conclusions are similar and supportive of combination therapy.3 22

Limitations of our study include the relatively small sample size and lack of a control group. Although prior studies have reported associations between biomarkers including PD-1, PD-L1, tumor mutation burden, and other inflammatory gene expression signatures and response during immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in patients with melanoma,23 24 biomarkers were not evaluated in this study, and thus, their potential relationship with responses could not be assessed. In addition, all participants were white and from the USA, potentially limiting the generalizability of the results.

In conclusion, combination therapy with intratumoral V937 plus ipilimumab had manageable toxicities that were consistent with those of the individual monotherapies. Responses were robust, including in the subset of patients with disease that progressed on prior anti-PD-1 therapy.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the patients and their families and caregivers for participating in this study, along with all investigators and site personnel. Medical writing assistance was provided by Michael S McNamara, MS, and Erin Bekes, PhD, of ICON plc (Blue Bell, Pennsylvania, USA). This assistance was funded by Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co, Inc, Rahway, New Jersey, USA.

Footnotes

Contributors: BDC: conception, design or planning of the study; analysis of the data; acquisition of the data; interpretation of the results; drafting of the manuscript; reviewing or revising the manuscript for important intellectual content; provision of study materials/patients; approval of the final submitted version; accountable for all aspects of the work; guarantor. JR: acquisition of the data; interpretation of the results; drafting of the manuscript; reviewing or revising the manuscript for important intellectual content; approval of the final submitted version; accountable for all aspects of the work. JRH: acquisition of the data; interpretation of the results; drafting of the manuscript; approval of the final submitted version; accountable for all aspects of the work. GAD: acquisition of the data; interpretation of the results; reviewing or revising the manuscript for important intellectual content; approval of the final submitted version; accountable for all aspects of the work. MF: analysis of the data; acquisition of the data; interpretation of the data; reviewing or revising the manuscript for important intellectual content; approval of the final submitted version; accountable for all aspects of the work. LF: acquisition of the data; interpretation of the data; reviewing or revising the manuscript for important intellectual content; approval of the final submitted version; accountable for all aspects of the work. KAM: analysis of the data; acquisition of the data; reviewing or revising the manuscript for important intellectual content; approval of the final submitted version; accountable for all aspects of the work. SH: interpretation of the results; reviewing or revising the manuscript for important intellectual content; provision of study materials/patients; approval of the final submitted version; accountable for all aspects of the work. MG: acquisition of the data; reviewing or revising the manuscript for important intellectual content; administrative, logistical or technical support; approval of the final submitted version; accountable for all aspects of the work. YZ: analysis of the data; interpretation of the results; reviewing or revising the manuscript for important intellectual content; approval of the final submitted version; accountable for all aspects of the work. AL: conception, design or planning of the study; reviewing or revising the manuscript for important intellectual content; approval of the final submitted version; accountable for all aspects of the work. RHIA: conception, design or planning of the study; analysis of the data; interpretation of the results; drafting of the manuscript; reviewing or revising the manuscript for important intellectual content; approval of the final submitted version; accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: Funding for this research was provided by Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co, Inc, Rahway, New Jersey, USA.

Competing interests: BDC: data safety monitoring board for Merck; institutional funding from Bristol Myers Squibb and Viralytics; honoraria from Cullinan Oncology, Nektar Therapeutics, and Clinigen. JR: none. JRH: institutional funding from Merck, BMS, Takara, and Amgen; advisory boards for BMS/Nektar Therapeutics. GAD: none. MF: advisory boards for Merck, Bristol Myers Squibb, Novartis, Nektar, Sanofi, and Array Biopharma. LF: none. KAM: consultant for ImaginAb, Oncosec, Werewolf, Xilio, Instil, IOvance, and Checkmate Pharmaceuticals; institutional funding from Merck, BMS, Roche, BioNTech, Checkmate Pharmaceuticals, IO Biotech, Regeneron, and Agenus. SH: none. MG: consultant/independent contractor (contracted directly by Viralytics). YZ and AL: employees of Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co, Inc, Rahway, New Jersey, USA and stockholders in Merck & Co, Inc, Rahway, New Jersey, USA. RHIA: institutional research funding from Viralytics; in the past 3 years, employee of Seven and Eight Biopharmaceuticals Inc.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request. Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co, Inc, Rahway, New Jersey, USA (MSD) is committed to providing qualified scientific researchers access to anonymized data and clinical study reports from the company’s clinical trials for the purpose of conducting legitimate scientific research. MSD is also obligated to protect the rights and privacy of trial participants and, as such, has a procedure in place for evaluating and fulfilling requests for sharing company clinical trial data with qualified external scientific researchers. The MSD data sharing website (available at: http://engagezone.msd.com/ds_documentation.php) outlines the process and requirements for submitting a data request. Applications will be promptly assessed for completeness and policy compliance. Feasible requests will be reviewed by a committee of MSD subject matter experts to assess the scientific validity of the request and the qualifications of the requestors. In line with data privacy legislation, submitters of approved requests must enter into a standard data-sharing agreement with MSD before data access is granted. Data will be made available for request after product approval in the US and EU or after product development is discontinued. There are circumstances that may prevent MSD from sharing requested data, including country-specific or region-specific regulations. If the request is declined, it will be communicated to the investigator. Access to genetic or exploratory biomarker data requires a detailed, hypothesis-driven statistical analysis plan that is collaboratively developed by the requestor and MSD subject matter experts; after approval of the statistical analysis plan and execution of a data-sharing agreement, MSD will either perform the proposed analyses and share the results with the requestor or will construct biomarker covariates and add them to a file with clinical data that is uploaded to an analysis portal so that the requestor can perform the proposed analyses.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This was a multicenter study. The study protocol and amendments were approved by institutional review boards or independent ethics committees at each study site. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.Macedo N, Miller DM, Haq R, et al. Clinical landscape of oncolytic virus research in 2020. J Immunother Cancer 2020;8:e001486. 10.1136/jitc-2020-001486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Imlygic® (talimogene laherparepvec) . Full prescribing information. BioVex, Inc., a subsidiary of Amgen Inc., Thousand Oaks, CA; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andtbacka RHI, Kaufman HL, Collichio F, et al. Talimogene laherparepvec improves durable response rate in patients with advanced melanoma. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:2780–8. 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.3377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaufman HL, Kohlhapp FJ, Zloza A. Oncolytic viruses: a new class of immunotherapy drugs. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2015;14:642–62. 10.1038/nrd4663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andtbacka RHI, Curti B, Daniels GA, et al. Clinical responses of oncolytic coxsackievirus A21 (V937) in patients with unresectable melanoma. J Clin Oncol 2021;39:3829–38. 10.1200/JCO.20.03246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kageshita T, Yoshii A, Kimura T, et al. Clinical relevance of ICAM-1 expression in primary lesions and serum of patients with malignant melanoma. Cancer Res 1993;53:4927–32 10.1016/0923-1811(93)90825-A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shafren DR, Dorahy DJ, Ingham RA, et al. Coxsackievirus A21 binds to decay-accelerating factor but requires intercellular adhesion molecule 1 for cell entry. J Virol 1997;71:4736–43. 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4736-4743.1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shafren DR, Au GG, Nguyen T, et al. Systemic therapy of malignant human melanoma tumors by a common cold-producing enterovirus, coxsackievirus A21. Clin Cancer Res 2004;10:53–60. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-0690-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaufman HL, Kim DW, DeRaffele G, et al. Local and distant immunity induced by intralesional vaccination with an oncolytic herpes virus encoding GM-CSF in patients with stage IIIC and IV melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol 2010;17:718–30. 10.1245/s10434-009-0809-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ribas A, Dummer R, Puzanov I, et al. Oncolytic virotherapy promotes intratumoral T cell infiltration and improves anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. Cell 2017;170:1109–19. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.08.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silk AW, O'Day SJ, Kaufman HL, et al. Intratumoral oncolytic virus V937 in combination with pembrolizumab in patients with advanced melanoma: updated results from the phase 1b CAPRA study. In: American Association for Cancer Research (AACR). Virtual, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gellrich FF, Schmitz M, Beissert S, et al. Anti-Pd-1 and novel combinations in the treatment of melanoma-an update. J Clin Med 2020;9:223. 10.3390/jcm9010223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bowyer S, Prithviraj P, Lorigan P, et al. Efficacy and toxicity of treatment with the anti-CTLA-4 antibody ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma after prior anti-PD-1 therapy. Br J Cancer 2016;114:1084–9. 10.1038/bjc.2016.107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pires da Silva I, Ahmed T, Reijers ILM, et al. Ipilimumab alone or ipilimumab plus anti-PD-1 therapy in patients with metastatic melanoma resistant to anti-PD-(L)1 monotherapy: a multicentre, retrospective, cohort study. Lancet Oncol 2021;22:836–47. 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00097-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yervoy® (ipilimumab) . Full prescribing information. Bristol Myers Squib, Princeton, NJ; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolchok JD, Hoos A, O'Day S, et al. Guidelines for the evaluation of immune therapy activity in solid tumors: immune-related response criteria. Clin Cancer Res 2009;15:7412–20. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoos A, Eggermont AMM, Janetzki S, et al. Improved endpoints for cancer immunotherapy trials. J Natl Cancer Inst 2010;102:1388–97. 10.1093/jnci/djq310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hodi FS, Chesney J, Pavlick AC, et al. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab versus ipilimumab alone in patients with advanced melanoma: 2-year overall survival outcomes in a multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:1558–68. 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30366-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robert C, Schachter J, Long GV, et al. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med 2015;372:2521–32. 10.1056/NEJMoa1503093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab or monotherapy in untreated melanoma. N Engl J Med 2015;373:23–34. 10.1056/NEJMoa1504030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Madden KM, Hoffner B. Ipilimumab-based therapy: consensus statement from the faculty of the melanoma nursing initiative on managing adverse events with ipilimumab monotherapy and combination therapy with nivolumab. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2017;21:30–41. 10.1188/17.CJON.S4.30-41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chesney J, Puzanov I, Collichio F, et al. Randomized, open-label phase II study evaluating the efficacy and safety of talimogene laherparepvec in combination with ipilimumab versus ipilimumab alone in patients with advanced, unresectable melanoma. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:1658–67. 10.1200/JCO.2017.73.7379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hodi FS, Wolchok JD, Schadendorf D, et al. TMB and inflammatory gene expression associated with clinical outcomes following immunotherapy in advanced melanoma. Cancer Immunol Res 2021;9:1202–13. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-20-0983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morrison C, Pabla S, Conroy JM, et al. Predicting response to checkpoint inhibitors in melanoma beyond PD-L1 and mutational burden. J Immunother Cancer 2018;6:32. 10.1186/s40425-018-0344-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

jitc-2022-005224supp002.pdf (1.1MB, pdf)

jitc-2022-005224supp001.pdf (34KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request. Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co, Inc, Rahway, New Jersey, USA (MSD) is committed to providing qualified scientific researchers access to anonymized data and clinical study reports from the company’s clinical trials for the purpose of conducting legitimate scientific research. MSD is also obligated to protect the rights and privacy of trial participants and, as such, has a procedure in place for evaluating and fulfilling requests for sharing company clinical trial data with qualified external scientific researchers. The MSD data sharing website (available at: http://engagezone.msd.com/ds_documentation.php) outlines the process and requirements for submitting a data request. Applications will be promptly assessed for completeness and policy compliance. Feasible requests will be reviewed by a committee of MSD subject matter experts to assess the scientific validity of the request and the qualifications of the requestors. In line with data privacy legislation, submitters of approved requests must enter into a standard data-sharing agreement with MSD before data access is granted. Data will be made available for request after product approval in the US and EU or after product development is discontinued. There are circumstances that may prevent MSD from sharing requested data, including country-specific or region-specific regulations. If the request is declined, it will be communicated to the investigator. Access to genetic or exploratory biomarker data requires a detailed, hypothesis-driven statistical analysis plan that is collaboratively developed by the requestor and MSD subject matter experts; after approval of the statistical analysis plan and execution of a data-sharing agreement, MSD will either perform the proposed analyses and share the results with the requestor or will construct biomarker covariates and add them to a file with clinical data that is uploaded to an analysis portal so that the requestor can perform the proposed analyses.