Abstract

Purpose:

Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR T) therapy is capable of eliciting durable responses in patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) lymphomas. However, most treated patients relapse. Patterns of failure after CAR T have not been previously characterized, and may provide insights into the mechanisms of resistance guiding future treatment strategies.

Methods and Materials:

This is a retrospective analysis of patients with R/R large B-cell lymphoma who were treated with anti-CD19 CAR T at a National Cancer Institute-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center between 2015 and 2019. Pre- and posttreatment positron emission/computed tomography scans were analyzed to assess the progression of existing (local failures) versus new, nonoverlapping lesions (de novo failures) and identify lesions at a high risk for progression.

Results:

A total of 469 pretreatment lesions in 63 patients were identified. At a median follow-up of 12.6 months, 36 patients (57%) recurred. Most (n = 31; 86%) had a component of local failure, and 13 patients (36%) exhibited strictly local failures. Even when progressing, 84% of recurrent patients continued to have a subset of pretreatment lesions maintain positron emission/computed tomography resolution. Lesions at a high risk for local failure included those with a diameter ≥5 cm (odds ratio [OR], 2.34; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.55–3.55; P < .001), maximum standardized uptake value ≥10 (OR, 2.08; 95% CI, 1.38–3.12; P < .001), or those that were extranodal (OR, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.10–2.04; P = .01). In the 69 patients eligible for survival analysis, those with any lesion ≥5 cm (n = 46; 67%) experienced inferior progression-free survival (hazard ratio, 2.41; 95% CI, 1.15–5.04; P = .02) and overall survival (hazard ratio, 3.36; 95% CI, 1.17–9.96; P = .02).

Conclusions:

Most patients who recur after CAR T experience a component of local progression. Furthermore, lesions with high-risk features, particularly large size, were associated with inferior treatment efficacy and patient survival. Taken together, these observations suggest that lesion-specific resistance may contribute to CAR T treatment failure. Locally directed therapies to high-risk lesions, such as radiation therapy, may be a viable strategy to prevent CAR T failures in select patients.

Introduction

Anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR T) therapies are approved as the standard of care for patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) large B-cell lymphoma (LBCL) after 2 lines of prior therapy. Initially described in single-institution studies,1,2 the CD19 CAR T therapies axicabtagene ciloleucel and tisagenlecleucel were approved for the treatment of R/R LBCL after the pivotal multicenter ZUMA-13 and JULIET4 trials, respectively. Although the patient characteristics differed between the 2 trials, each study demonstrated the potential for CD19 CAR T therapy to elicit a complete and durable response in roughly 40% of heavily pretreated patients4 with approximately half of patients alive at 2 years.5,6 A similar rate of durable remission has since been reported for patients receiving CAR T therapy outside of clinical trials.7–9

Despite the significant improvement in both response rates and survival, more than half of patients will ultimately develop a recurrence after CAR T, at which point treatment options are limited and prognosis is poor.10,11 Although studies have evaluated the relationship of patient characteristics with treatment outcomes,9,12 little is known about lesion-specific risk factors predisposing to CAR T treatment failure.13 In this study, we describe the anatomic recurrence patterns after CAR T therapy. First, we characterize the contribution of local failure (ie, relapses of lesions present before CAR T therapy) versus de novo failure (ie, relapses at new, distant sites not involved before CAR T therapy). Second, we identify lesion characteristics at a high risk of local failure. Finally, we determine whether individual lesions within a patient can predict overall treatment response. These results provide insights into the role of individual lesions contributing to CAR T resistance, and address the potential of incorporating additional local therapies, such as radiation therapy, to improve the overall efficacy of CAR T.

Methods and Materials

Study design and participants

Patients with LBCL, including diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, transformed follicular lymphoma, and primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma, who received axicabtagene ciloleucel or tisagenlecleucel at our center between May 2015 and March 2019 were identified and their records underwent a retrospective review. Data were closed in October 2019 to ensure a 6-month minimum of data maturation. Baseline patient and disease characteristics, previous treatment regimens, and CAR T related toxicities were collected with a prospectively managed patient registry. This study was approved by our institutional review board.

Per our institutional protocol, patients received a positron emission tomography (PET)/computed tomography (CT) scan before CAR T infusion with repeat imaging 1-, 3-, and 6-months after treatment, followed by every 3 to 6 months thereafter or until progression. Patients with a pretreatment PET/CT ≥60 days before CAR T infusion (n = 5) and those with radiographic evidence of diffuse bone marrow involvement (n = 2) were excluded from the analysis to reasonably compare pre- and posttreatment imaging, as well as accurately report the anatomic recurrence patterns and lesion-specific outcomes. Furthermore, those who received bridging radiation therapy (n = 13) were excluded for concern that focal therapy would alter the local failure rates and potentially the patterns of recurrence.

Each patient’s baseline PET/CT scan was analyzed to identify all pretreatment disease sites, defined as a hypermetabolic lesion on a PET scan that was anatomically distinct from other nearby hypermetabolic disease on corresponding CT scans. Therefore, a conglomerate of matted lymph nodes with no indistinguishable anatomic planes were characterized as a single clustered lesion (Fig. E1A) analogous to principles used in involved-site radiation therapy.14,15 Lesions were characterized by their location (nodal vs extranodal), size (diameter in cm; metabolic volume in cm3), metabolic activity (maximum standardized uptake value [SUVmax]), and the presence/absence of necrosis. Necrosis was defined as a hypermetabolic rim encapsulating a nonmetabolic core on PET scans with a corresponding attenuation of >10 Hounsfield units on CT scans (Fig. E1B).16,17

Standardized uptake value analysis

Baseline PET/CT scans were analyzed using Mirada (Mirada Medical, Oxford, United Kingdom) to identify the SUVmax and metabolic volume of each pretreatment lesion. To account for interstudy PET variation, each lesion was contoured using an SUV threshold of 2 standard deviations greater than the mean SUV of the liver18,19 and subjectively corrected when appropriate to exclude normal physiological uptake. For patients where an SUV threshold was unable to be determined (ie, owing to diffuse liver metastases), a SUV threshold of 2.5 was used.

Treatment response and recurrence patterns

The response of each individual pretreatment lesion was evaluated by comparing subsequent PET/CT scans to pretreatment images. Treatment responses were assessed according to the International Working Group Response Criteria for Malignant Lymphoma.20 CAR T failure was defined at the first radiographic evidence of progressive disease. Baseline imaging was compared with imaging at the time of treatment failure to characterize each pretreatment lesion’s response, and determine whether the patient experienced a local failure, de novo failure, or both.

At the time of overall disease progression, we evaluated the individual treatment response of each pretreatment lesion. Local failure was ascribed to any lesion with Deauville 4 or 5 at the time of treatment failure, and local control was ascribed to any lesion that resolved with treatment on PET/CT scans (defined as Deauville 1–3). We made this decision given that any residual disease at the time of treatment failure could potentially contribute to overall disease progression. The threshold of using Deauville 1 to 3 in the post-CAR T setting was based on the ZUMA-1 trial demonstrating that patients with a Lugano complete response (defined as Deauville 1–3) after CAR T-cell therapy have superior outcomes compared with those with partial response.3

Statistical methods

To identify lesion-specific risk factors associated with local failure, lesion-level univariate and multivariable analyses were performed using generalized estimating equations (GEEs) with an exchangeable correlation structure.21 This was necessary to account for the potential correlation of outcomes between multiple lesions within the same patient. Subsequently, sensitivity analyses were conducted using alternative covariance structures to acknowledge the potential various degrees of dependence between lesions within a patient. The multivariable model included variables that were clinically relevant and significantly associated with recurrence in the univariate analysis. The final model included the following attributes: nodal versus extranodal, presence/absence of necrosis, SUVmax ≥10, and diameter ≥5 cm. An SUVmax ≥10 was chosen based on the previously reported LBCL literature,22 and further supported by our univariate analysis.

Survival analyses were performed for time-to-event analyses. Each was calculated using a Kaplan-Meier analysis and compared with a log-rank test from the date of CAR T infusion. Patient-level survival analyses were performed to estimate progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS), as well as compare whether the presence of pretreatment lesion characteristics predicted for treatment efficacy and clinical outcomes. The subset of patients without posttreatment PET/CT scans were excluded from the patterns of recurrence and local failure analysis, but were included in the PFS and OS analyses.

Results

Patient characteristics

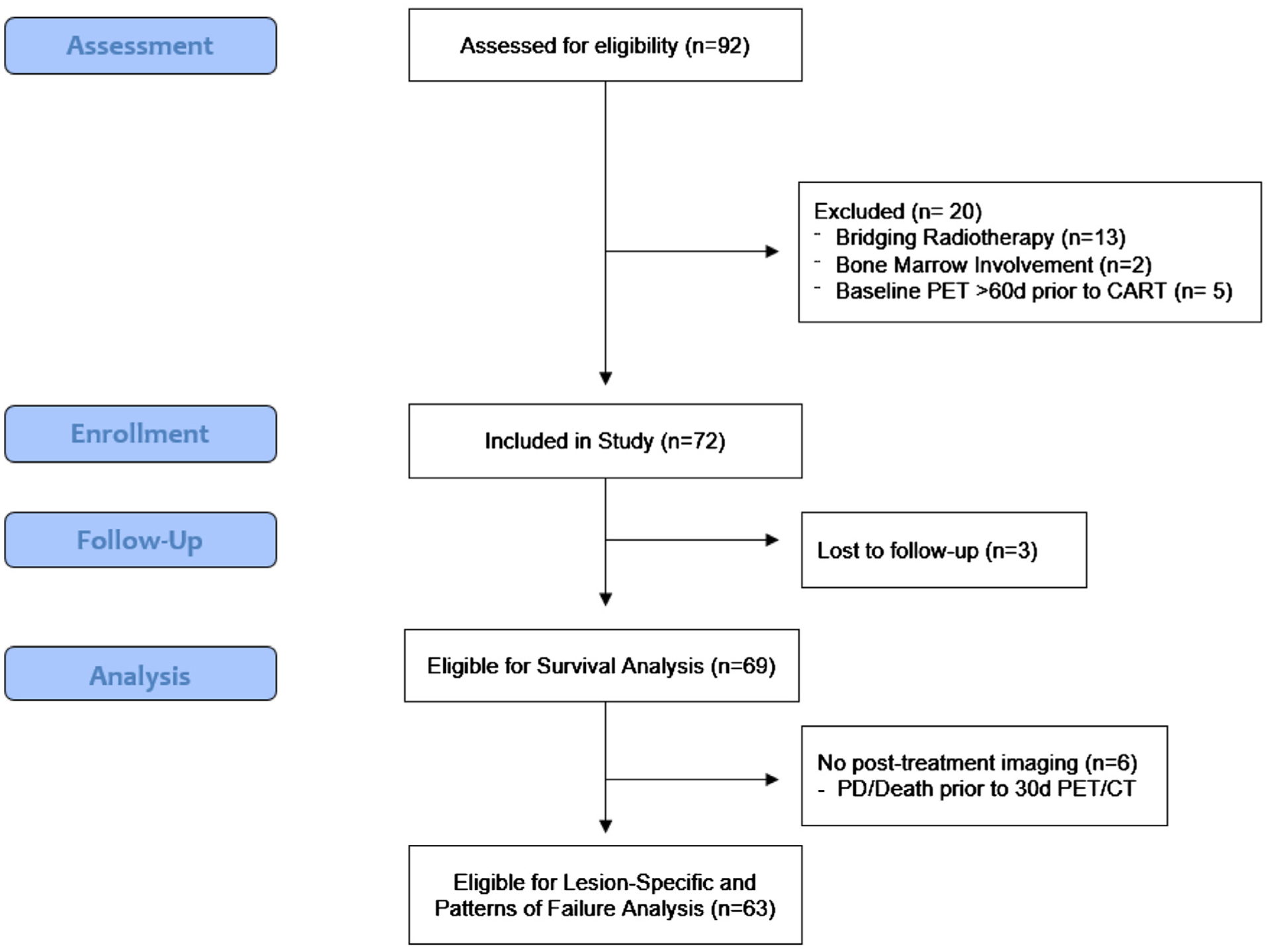

A total of 72 consecutive patients with R/R LBCL who were treated with CAR T were identified as meeting the inclusion criteria. Nine patients were not eligible for local failure and the patterns of recurrence analysis because there was no posttreatment imaging to evaluate lesion-specific treatment response and/or recurrence patterns. Of these 9 patients, 6 (8%) had disease progression or died before their 30-day PET/CT scans and 3 (4%) were lost to follow-up (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Trial profile.

Of the 63 evaluable patients, most were male (n = 46; 73%) and had diffuse LBCL (n = 43; 68%) (Table 1). The median age was 64 years (range, 28–76 years) with a median metabolic tumor volume of 213 cm3 (range, 0.7–4084.8 cm3). At the time of CAR T, 30 patients (48%) had strictly nodal disease, 10 (16%) had strictly extranodal disease, and 23 (37%) had involvement of both. The median time from baseline PET/CT imaging to CAR T infusion was 9 days (interquartile range, 7–28 days).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Patient characteristics | ||

|---|---|---|

| Patients, n (%) | 63 | 100% |

| Age, y, median (range) | 64 | (28–76) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 46 | 73% |

| Female | 17 | 27% |

| Histology, n (%) | ||

| Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma | 43 | 68% |

| Transformed follicular lymphoma | 18 | 29% |

| Primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma | 2 | 3% |

| Cell of origin, n (%) | ||

| Activated B-cell | 23 | 37% |

| Germinal center B-cell | 33 | 52% |

| Unknown | 7 | 11% |

| Stage at apheresis, n (%) | ||

| I/II | 14 | 22% |

| III/IV | 49 | 77% |

| Double hit, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 15 | 24% |

| No | 38 | 60% |

| Unknown | 10 | 16% |

| Type of recurrence, n (%) | ||

| Primary refractory | 22 | 33% |

| Refractory | 27 | 43% |

| Relapsed | 14 | 22% |

| Prior autologous stem cell transplantation, n (%) | 17 | 27% |

| Prior allogeneic stem cell transplantation, n (%) | 1 | 2% |

| Bridging therapy, n (%) | ||

| Chemotherapy | 18 | 29% |

| Targeted agents | 3 | 5% |

| Steroids alone | 24 | 38% |

| None | 18 | 29% |

| No. of pretreatment lesions, median (range) | 5 | (1–30) |

| Tumor metabolic volume, cm3, median (range) | 186.6 | (0.7–4084.6) |

| Time from pretreatment PET to CAR T infusion, d, median (interquartile range) | 9 | (7–28) |

| CAR T agent, n (%) | ||

| Axicabtagene ciloleucel | 61 | 97% |

| Tisagenlecleucel | 2 | 3% |

| Disease distribution at infusion, n (%) | ||

| Nodal only | 30 | 48% |

| Nodal + extranodal | 23 | 37% |

| Extranodal only | 10 | 16% |

Abbreviations: CAR T = chimeric antigen receptor T-cell; PET = positron emission tomography.

Patterns of failure

At a median follow-up of 12.6 months (range, 1.4–46.4 months), 27 patients (43%) continued to demonstrate a durable response with no evidence of disease. Of the 36 patients with progression, 31 (86%) had some component of local failure, with 18 patients (50%) experiencing concurrent local and de novo recurrences and 13 (36%) having strictly local failures (Fig. E2). The remaining 5 patients (14%) demonstrated only de novo failure at the time of disease progression.

In the 36 patients with recurrence, 5 (14%), 18 (50%), and 11 (30%) patients progressed at 30 days, 3 months, and 6 months after treatment imaging, respectively. Therefore, the vast majority of patients (n = 34; 94%) experienced treatment failure by the 6-month imaging, and all patients progressed by 12 months. One patient (4%) had CD-19 negative disease at the time of relapse diagnosed by flow cytometry; however, CD-19 status at the time of recurrence was not obtained in 10 patients (28%). Most patients (n = 29; 81%) underwent subsequent salvage therapies, including 5 patients who received a second course of CAR T. However, OS after CAR T progression was dismal, with a median and 12-month OS of 7.4 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 4.2–10.7 months) and 33%, respectively. In comparison, all patients who experienced a durable response continue to be alive at the time of the most recent follow-up.

Lesion-specific risk factors predicting lesion outcomes

Pretreatment PET/CT scans identified a total of 469 individual lesions in 63 patients with a median of 5 lesions per patient (range, 1–30) (Fig. E3A). Most of the lesions were nodal (n = 341; 73%), roughly a third were clustered (n = 168; 36%), and few (n = 21; 5%) were necrotic (Table 2) with a median metabolic volume of 12.3 cm3 and median SUVmax of 11.4. There were no differences in the patterns of failure between patients with ≤5 pretreatment lesions compared with those with >5 lesions (Fig. E3B).

Table 2.

Pretreatment lesion characteristics

| n | % (interquartile range) | |

|---|---|---|

| No. of pretreatment lesions | 469 | |

| Median diameter, cm | 2.6 | (1.5–4.4) |

| Median metabolic volume, cm3 | 12.3 | (3.9–42.7) |

| Median maximum standardized uptake value | 11.4 | (7.4–17.4) |

| Location | ||

| Nodal | 341 | 73% |

| Extranodal | 128 | 27% |

| Clustered | ||

| Yes | 168 | 36% |

| No | 301 | 64% |

| Necrotic | ||

| Yes | 21 | 5% |

| No | 448 | 95% |

| Diameter ≥5 cm | ||

| Yes | 93 | 20% |

| No | 376 | 80% |

| Maximum standardized uptake value ≥10 | ||

| Yes | 263 | 56% |

| No | 206 | 44% |

A total of 297 lesions were observed within the 36 patients who progressed, with a median of 5 lesions per patient (interquartile range, 3–11). In these patients, more than half of pretreatment lesions (n = 162; 55%) (Fig. E4) continued to respond to treatment with the remainder of the lesions having ongoing PET avidity (Deauville 4 or 5) at the time of patient relapse. Among patients with multiple pretreatment lesions in whom treatment failed (n = 32), most patients (n = 27; 84%) continued to have at least 1 pretreatment lesion maintain treatment response on PET imaging at the time of overall disease progression.

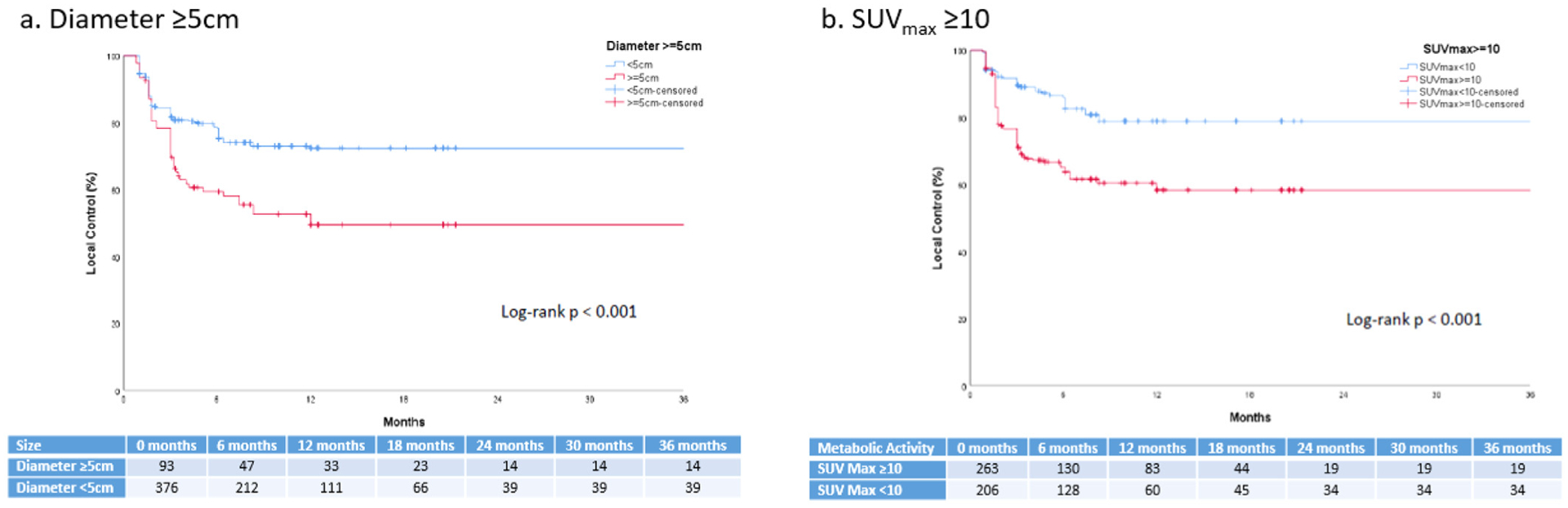

On GEE univariate analysis, lesion-specific characteristics associated with an increased risk of local failure included diameter ≥5 cm (odds ratio [OR], 2.94; 95% CI, 2.48–3•41; P < .001), SUVmax ≥10 (OR, 2.51; 95% CI, 2.09–2.92; P < .001), or extranodal disease (OR, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.01–2.86; P = •01) (Table 3). For illustrative purposes, the time-to-event outcomes of individual lesions based on diameter and SUVmax are presented in Figure 2.

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariable analyses of lesion-specific factors associated with local failure

| Variable | Generalized estimating equation exchangeable Univariate analysis | Generalized estimating equation exchangeable Multivariable analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Diameter | ||||

| ≥5 cm | 2.94 (2.48–3.41) | < .001 | 2.34 (1.55–3.55) | < .001 |

| <5 cm | Reference | Reference | ||

| SUVMax | ||||

| ≥10 | 2.51 (2.09–2.92) | < .001 | 2.08 (1.38–3.12) | < .001 |

| <10 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Necrotic | ||||

| Yes | 2.34 (1.30–3.38) | .11 | 1.30 (0.45–3.79) | .63 |

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Location | ||||

| Extranodal | 1.49 (1.01–2.86) | .01 | 1.49 (1.10–2.04) | .01 |

| Lymph node | Reference | Reference | ||

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio; SUVMax = maximum standardized uptake value.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of local control of individual pretreatment lesions by (A) diameter ≥5 cm and (B) maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) ≥10.

On GEE multivariable analysis of local failure, we observed that the lesion-specific risk factors of diameter ≥5 cm (OR, 2.34; 95% CI, 1.55–3.55; P< .001), SUVmax ≥10 (OR, 2.07; 95% CI, 1.37–3.12; P <•.001), and extranodal disease (OR, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.10–2.04; P = .01) maintained significance (Table 3). Sensitivity analyses were conducted using additional multivariable models with alternative covariance structures to account for the potential various degrees of dependence between lesions within a patient, which provided qualitatively similar results (Fig. E5).

Lesion-specific risk factors predicting patient outcomes

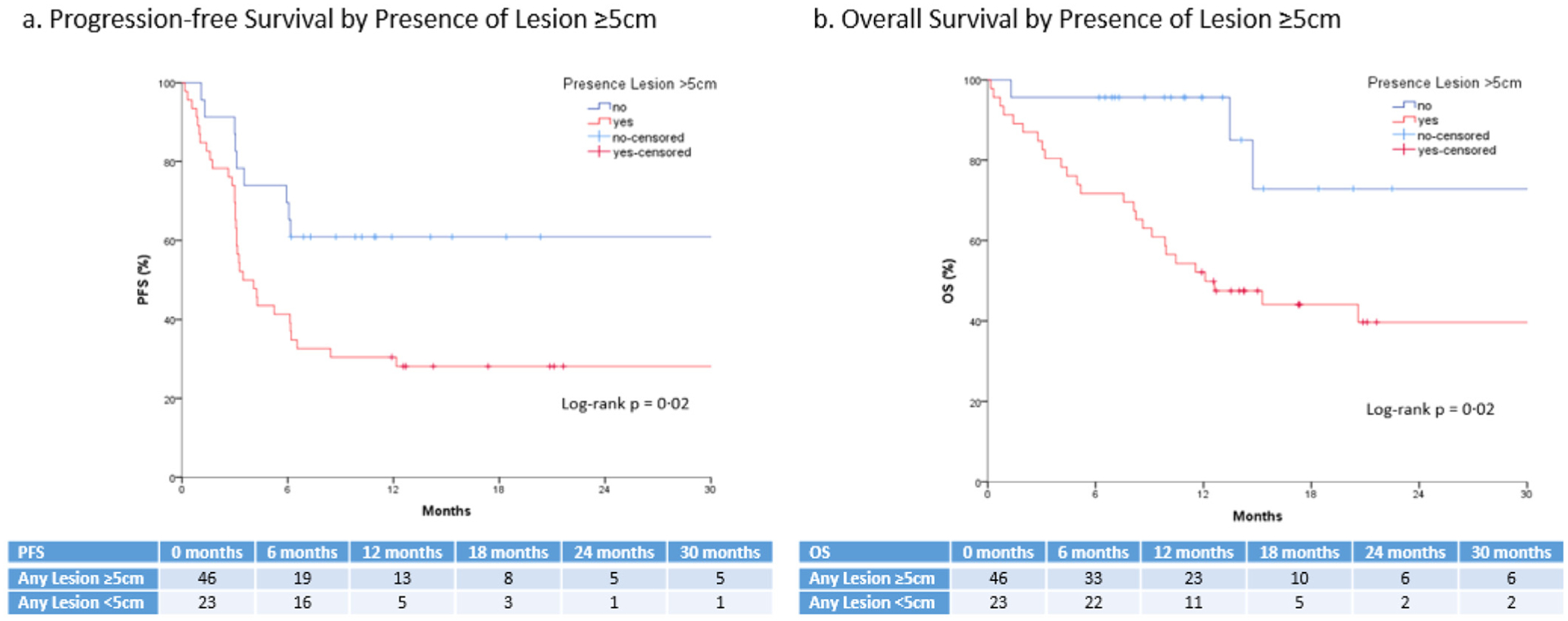

After observing a strong lesion-specific pattern of failure, we performed a patient-level analysis to determine whether the presence of particular baseline lesion characteristics translated into inferior treatment outcomes. We hypothesized that individual high-risk lesions were a dominant driver of resistance. Of note, the subset of 6 patients without post-CAR T imaging owing to progressive disease or death were included in the PFS and OS analyses, for a total of 69 patients.

Overall, our cohort experienced a 6- and 12-month PFS of 51% and 40%, respectively, and a 12- and 24-month OS of 65% and 49%, respectively. Outcomes of patients with specific lesion characteristics are presented in Table 4. Patients with any lesion ≥5 cm (n = 46; 67%) demonstrated an inferior PFS (hazard ratio [HR], 2.41; P = .02) and OS (HR, 3.36; P = .02) compared with patients with only smaller lesions (Fig. 3). We also noted that the presence of any necrotic lesion (n = 19; 28%) was associated with inferior PFS (HR, 1.89; P = .05) and OS (HR, 2.41; P = .05) compared with the absence of necrotic lesions. However, all necrotic lesions were ≥5 cm. On exploratory subgroup analysis, there was no difference in PFS (P = .35) or OS (P = .33) outcomes between patients with both bulky and necrotic disease (n = 19) compared with those with bulky disease and no necrosis (n = 27). Lastly, there were no differences in treatment response or survival when comparing the number of pretreatment lesions or the presence of any clustered or extranodal lesions (Table 4). Metabolic activity did not discriminate patients, likely because nearly all patients (n = 61; 88%) had at least 1 lesion with SUVmax ≥10.

Table 4.

Presence of lesion-specific risk factors on progression-free and overall survival

| Patients n (%) | 12-month progression-free survival | HR (95% CI) | P-value | 12-month overall survival | HR (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size | |||||||

| Any lesion ≥5 cm | 46 (67) | 30.4% | 2.41 (1.15–5.04) | .02 | 52.2% | 3.36 (1.17–9.96) | .02 |

| All lesions <5 cm | 23 (33) | 60.9% | 95.7% | ||||

| Necrosis | |||||||

| Any necrotic lesion | 19 (28) | 26.3% | 1.89 (0.99–3.60) | .05 | 47.4% | 2.11 (1.01–4.40) | .05 |

| No necrotic lesions | 50 (72) | 45.6% | 71.7% | ||||

| Extranodal | |||||||

| Any extranodal lesion | 38 (55) | 41.9% | 0.95 (0.52–1.74) | .86 | 63.6% | 1.00 (0.49–2.06) | .99 |

| No clustered lesions | 31 (45) | 38.7% | 66.2% | ||||

| Metabolic activity | |||||||

| Any lesion with SUVMax ≥10 | 61 (88) | 40.7% | 1.16 (0.46–2.96) | .75 | 62.1% | 1.99 (0.47–8.42) | .35 |

| All lesions with SUVMax < 10 | 8 (12) | 37.5% | 85.7% | ||||

| Lesions per patient | |||||||

| ≥6 lesions | 31 (45) | 38.2% | 1.25 (0.68–2.28) | .48 | 56.6% | 1.58 (0.77–3.24) | .21 |

| ≤5 lesions | 38 (55) | 42.1% | 71.9% |

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio; SUVMax = maximum standardized uptake value.

Fig. 3.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of progression-free and overall survival by presence of lesion-specific risk factors.

Discussion

In this study, we report the anatomic patterns of recurrence for patients with R/R LBCL after CAR T, as well as identify lesion-specific risk factors associated with both local progression and overall treatment outcomes. The overwhelming majority of patients who progress after CAR T demonstrate some component of local failure with over a third of patients exhibiting purely local failures. Lesions at a high risk for local failure can be predicted using features present on routine PET/CT imaging, including high metabolic activity (SUVmax ≥10), size (diameter ≥5 cm), or location (extranodal disease). Furthermore, the presence of particular high-risk lesions, specifically large lesions, is associated with inferior treatment outcomes and survival. We also observed that in patients who recur, there were almost always (84%) discordant lesion response to CAR T-cell therapy, with some lesions remaining in remission while others progress, which suggests that CAR T resistance may occur at the level of individual lesions.

The combined observations that local progression is a dominant feature of treatment failure, the risk of progression for individual lesions can be predicted, and the presence of individual high-risk lesions is associated with inferior treatment efficacy provide a rationale for considering the inclusion of locally directed treatment, such as radiation therapy, to high-risk lesions in patients undergoing CAR T.

Despite the significant improvement in outcomes provided by anti-CD19 CAR T, most patients with lymphoma eventually relapse, at which point treatment options are limited and survival is extremely poor. In our cohort, patients who progressed after CAR T declare early recurrence, with nearly all recurrences occurring by the time of 6-month imaging, supporting previous evidence that early treatment response serves as an effective surrogate for ultimate treatment efficacy. Identifying risk factors may help elucidate mechanisms of failure and select patients who may benefit from treatment escalation.5 Although early data demonstrate that patients with a high tumor burden experience inferior outcomes after CAR T cell therapy, our data suggest that this relationship further extends to the level of individual lesions, with larger pretreatment lesions portending to a higher risk of treatment failure.9,12,23 By characterizing anatomic recurrence patterns and then subsequently identifying lesion-specific characteristics predisposing for local failure, this study aimed to potentially use baseline imaging to identify high-risk patients for focal supplemental therapy.

Most relapsing lesions occur locally; thus, consideration may be given to combining CAR T with a local treatment. The manufacture of autologous CAR T-cells takes nearly 3 to 4 weeks. This latency period, where the disease would otherwise continue to proliferate unabated, presents a potential window for supplemental treatment (ie, bridging therapy). By understanding which patients, and thus which individual lesions, are most likely to progress, clinicians may begin to incorporate local therapies to control high-risk lesions. Previous reports have described the feasibility of radiation therapy as a bridging strategy for patients receiving CAR T, and found no evidence of substantive toxicity induced by the addition of radiation.24–26 However, the optimal sequence and timing of combining CAR T and radiation therapy remains unknown. Although some institutions have proposed bridging radiation therapy, salvage radiation therapy after CAR T progression has also been shown to be safe and feasible.27

In our patients whose disease progressed, half of all pretreatment lesions continue to maintain a durable metabolic response to CAR T therapy. In those with ≥2 lesions, 84% had at least 1 lesion maintain metabolic resolution with CAR T. These observations indicate there may be substantial lesion-specific variation in sensitivity and resistance even within the same patient. Lesion-specific mechanisms of resistance may include expansion of resistant clones, but may also be influenced by immunosuppressive tumor microenvironments. This may include metabolic derangements, such as hypoxia and acidosis that are known to be highly immunosuppressive in preclinical models.28 This is consistent with our observation of SUVmax, indicating an underlying metabolic abnormality, being risk factors for local failure. Alternative mechanisms may include physical barriers to immune infiltration, such as poor perfusion, elevated intratumoral pressure, or changes in tumor stroma. Regardless of the mechanism, the rationale for local therapy remains.

Radiation therapy has been commonly used in the treatment for patients with high-risk LBCL to complement modern immunochemotherapy regimens, such as rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and prednisolone (R-CHOP). When treated with R-CHOP alone, patients with advanced stage LBCL have been shown to experience a similar frequency and distribution of recurrences compared with our cohort of patients who received CAR T therapy (Fig. E6).29 Furthermore, those with lesions ≥5 cm also demonstrated inferior rates of local control and PFS prompting the consideration of radiation therapy. This approach has been considered for patients with bulky disease (defined as ≥7.5 cm) after R-CHOP based on prospective trials suggesting improved event-free survival30 and OS31 with consolidative radiation therapy. In contrast to the immunochemotherapy setting where subsequent lines of salvage therapies are available, there remains minimal treatment options available after CAR T progression, which further emphasizes the need to identify therapeutic strategies to improve outcomes in select high-risk patients.

However, the clinical benefit of incorporating local therapy with CAR T remains unproven. Half of patients who relapse experienced both local and de novo disease progression at the time of overall treatment failure, with a few patients exhibiting strictly de novo failures. For patients with current local and de novo recurrence, whether the residual local failure was the source for distant spread or microscopic disease had already disseminated by the time of CAR T infusion is unknown. The former could theoretically benefit from local therapy, but the latter would require either an alternate or escalated systemic option. Further prospective studies are warranted to determine the degree to which local and de novo disease progression influence one another, whether the addition of local therapy improves patient outcomes and if so, what is the proper sequence of treatments and the proper patient/lesion(s) selection required to optimize clinical efficacy.

Limitations

Limitations of this study include the retrospective design, variation in timing between baseline PET/CT to CAR T infusion, and limited sample size. Notably, we treated local failure as a binary outcome in our primary GEE univariate and multivariate analyses rather than a time-to-progression outcome as seen in Kaplan-Meier survival analyses. The reason is that among patients treated with CAR T cell therapy, the most important clinical outcome is whether or not the patient attains a durable remission, which is binary. Indeed, if patients relapse after CAR T therapy, the recurrence is almost always within the first 6 months; therefore, the time-to-progression is of lesser clinical importance.

Furthermore, the lesion-specific Kaplan-Meier curves assume that each pretreatment lesion within a patient responds independently to CAR T therapy. Therefore, we presented the data using a GEE exchangeable correlation structure to account for the variable number of pretreatment lesions per patient and the potential correlation of lesions within the same patient disproportionately influencing the ultimate outcomes of the study. We also conducted sensitivity analyses using several multivariable models with different correlation structures assumptions, each demonstrating relatively consistent conclusions. To avoid overfitting, we used parameters previously reported in the literature when available (ie, SUVmax ≥10). Some radiographic features (ie, necrosis) are highly correlated with size. Given the current patient numbers in this study, disentangling the importance of these risk factors was not possible. Potential competing risks when performing these lesion-based analyses is necessary to consider. We excluded 6 patients from our lesion-specific local failure or patterns of failure analysis because they either progressed or died before posttreatment imaging. Among the remaining 63 patients, none experienced death before lymphoma progression; therefore, we argue that the lesion-level analyses were not subject to competing risks in this cohort.

If CAR T therapy is used as front-line therapy for patients with high-risk LBCL, as seen in the ongoing ZUMA-12 trial (NCT03761056), or is introduced into the treatment of solid tumors, whether patients will continue to experience similar recurrence patterns is unknown. A comprehensive, lesion-based risk prediction model may be able to improve patient-level prognostication and will need to be pursued in future research. Lastly, although we propose the idea of integrating bridging radiation to high-risk lesions, the extent to which this would change clinical outcomes in a systemic disease is currently unknown and future prospective trials are needed before adoption into widespread clinical practice.

Conclusion

Despite the success of CAR T in the treatment of R/R LBCL, most patients will ultimately develop progressive disease after treatment. With recurrence, the disease tends to progress early and at known pretreatment disease site(s). Of the pretreatment lesions, those that are large (≥5 cm), hypermetabolically active (SUVmax ≥10), and/or extranodal are most likely to progress locally. In patients who recurred, roughly half of all lesions continue to maintain a metabolic response to treatment, suggesting that a substantial component of CAR T resistance may occur at the level of individual lesions even within the same patient.

Furthermore, the presence of large lesions may also translate into both inferior treatment responses and OS. Future local bridging treatments, such as radiation therapy, to high-risk sites have been previously shown to be safe, and may improve outcomes in select patients, but warrant additional study in a prospective manner.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments—

The authors thank all patients for their contributions to make this project possible.

Disclosures:

J.C.C. is on the advisory board for Kite/Gilead, Novartis, Bayer, and Genentech and on the Speaker Bureau for Genentech. B.D.S. is a consultant for Celgene/June, Adaptive, Kite/Gilead, Novartis, Pharmacyclics, Spectrum/Acroteca, and Astrazeneca and has received research funding from Jazz and Incyte. A.L. is on the scientific advisory board for EUSA Pharma US LLC. M.D. has received research funding from Celgene, Novartis, and Atara, as well as other financial support from Novartis, Precision Biosciences, Celyad, Bellicum, and GlaxoSmithKline, and holds stock options from Precision Biosciences, Adaptive Biotechnologies, and Anixa Biosciences. C.B. is a scientific advisor for Kite/Gilead and part of the speaker’s bureau for Novartis. T.N. has received research support to the institution from Novartis and Karyopharm. F.L.L. is a consultant for Cellular Biomedicine Group, Inc, as well as a scientific advisor for Kite/Gilead, Novartis, BMS/Celgene, Allogene, Wugen, Calibr, and GammaDelta Therapeutics, and has received research funding from Kite/Gilead. M.D.J. is a consultant/advisor for Kite/Gilead and Novartis. All other authors report no conflicts of interest.

F.L.L.’s effort was partially funded by the National Cancer Institute/National Institutes of Health (K23-CA201594), and this work was supported by National Cancer Institute/National Institutes of Health grant P30-CA076292. Otherwise, there was no external funding provided for this study.

Footnotes

Research data are stored in an institutional repository and will be shared upon request to the corresponding author.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2021.06.038.

References

- 1.Schuster SJ, Svoboda J, Chong EA, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells in refractory B-cell lymphomas. N Engl J Med 2017;377:2545–2554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kochenderfer JN, Dudley ME, Kassim SH, et al. Chemotherapy-refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and indolent B-cell malignancies can be effectively treated with autologous T cells expressing an anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:540–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neelapu SS, Locke FL, Bartlett NL, et al. Axicabtagene ciloleucel CAR T-cell therapy in refractory large B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2017;377:2531–2544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schuster SJ, Bishop MR, Tam CS, et al. Tisagenlecleucel in adult relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2019;380:45–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Locke FL, Ghobadi A, Jacobson CA, et al. Long-term safety and activity of axicabtagene ciloleucel in refractory large B-cell lymphoma (ZUMA-1): A single-arm, multicentre, phase 1–2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2019;20:31–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schuster SJ, Bishop MR, Tam CS, et al. Long-term follow-up of tisagenlecleucel in adult patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: Updated analysis of Juliet study. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2019;25:S20–S21. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nastoupil LJ, Jain MD, Spiegel JY, et al. Axicabtagene ciloleucel (axi-cel) CD19 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy for relapsed/refractory large B-cell lymphoma: Real world experience. Blood 2018;132:91. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jacobson CA, Hunter B, Armand P, et al. Axicabtagene ciloleucel in the real world: Outcomes and predictors of response, resistance and toxicity. Blood 2018;132:92. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nastoupil LJ, Jain MD, Feng L, et al. Standard-of-care axicabtagene ciloleucel for relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma: Results from the US Lymphoma CAR T Consortium. J Clin Oncol 2020. JCO1902104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spiegel JY, Dahiya S, Jain MD, et al. Outcomes in large B-cell lymphoma progressing after axicabtagene ciloleucel (axi-cel): Results from the U.S. Lymphoma CAR-T Consortium. J Clin Oncol 2019;37:7517. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chow VA, Gopal AK, Maloney DG, et al. Outcomes of patients with large B-cell lymphomas and progressive disease following CD19-specific CAR T-cell therapy. Am J Hematol 2019;94:E209–E213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dean E, Lu H, Lazaryan A, et al. Association of high baseline metabolic tumor volume with response following axicabtagene ciloleucel in refractory large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2019;37:7562. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Byrne M, Oluwole OO, Savani B, Majhail NS, Hill BT, Locke FL. Understanding and managing large B cell lymphoma relapses after chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2019;25:e344–e351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Specht L, Yahalom J, Illidge T, et al. Modern radiation therapy for Hodgkin lymphoma: Field and dose guidelines from the international lymphoma radiation oncology group (ILROG). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2014;89:854–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wirth A, Mikhaeel NG, Pauline Aleman BM, et al. Involved site radiation therapy in adult lymphomas: An overview of International Lymphoma Radiation Oncology Group guidelines. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2020;107:909–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adams HJA, de Klerk JMH, Fijnheer R, Dubois SV, Nievelstein RAJ, Kwee TC. Prognostic value of tumor necrosis at CT in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Eur J Radiol 2015;84:372–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hopper KD, Diehl LF, Cole BA, Lynch JC, Meilstrup JW, McCauslin MA. The significance of necrotic mediastinal lymph nodes on CT in patients with newly diagnosed Hodgkin disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1990;155:267–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Im HJ, Bradshaw T, Solaiyappan M, Cho SY. Current methods to define metabolic tumor volume in positron emission tomography: Which one is better? Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2018;52:5–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Venkat P, Oliver JA, Jin W, et al. Prognostic value of 18F-FDG PET/CT metabolic tumor volume for complete pathologic response and clinical outcomes after neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy for locally advanced esophageal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:150. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheson BD, Pfistner B, Juweid ME, et al. Revised response criteria for malignant lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:579–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanley JA, Negassa A, Edwardes MD, Forrester JE. Statistical analysis of correlated data using generalized estimating equations: an orientation. Am J Epidemiol 2003;157:364–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schoder H, Noy A, Gonen M, et al. Intensity of 18-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in positron emission tomography distinguishes between indolent and aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:4643–4651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Locke FL, Ghobadi A, Lekakis LJ, et al. Outcomes by prior lines of therapy (LoT) in ZUMA-1, the pivotal phase 2 study of axicabtagene ciloleucel (Axi-Cel) in patients (Pts) with refractory large B cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:3039. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sim AJ, Jain MD, Figura NB, et al. Radiation therapy as a bridging strategy for CAR T cell therapy with axicabtagene ciloleucel in diffuse large B-Cell lymphoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2019;105:1012–1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pinnix CC, Gunther JR, Dabaja BS, et al. Bridging therapy prior to axicabtagene ciloleucel for relapsed/refractory large B-cell lymphoma. Blood Adv 2020;4:2871–2883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wright CM, LaRiviere MJ, Baron JA, et al. Bridging radiation therapy before commercial chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy for relapsed or refractory aggressive B-cell lymphoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2020;108:178–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Imber BS, Sadelain M, DeSelm C, et al. Early experience using salvage radiotherapy for relapsed/refractory non-Hodgkin lymphomas after CD19 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy. Br J Haematol 2020;190:45–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Damgaci S, Ibrahim-Hashim A, Enriquez-Navas PM, Pilon-Thomas S, Guvenis A, Gillies RJ. Hypoxia and acidosis: Immune suppressors and therapeutic targets. Immunology 2018;154:354–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shi Z, Das S, Okwan-Duodu D, et al. Patterns of failure in advanced stage diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients after complete response to R-CHOP immunochemotherapy and the emerging role of consolidative radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2013;86:569–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pfreundschuh M, Murawski N, Ziepert M, et al. Radiotherapy (RT) to bulky (B) and extralymphatic (E) disease in combination with 6 × R-CHOP-14 or R-CHOP-21 in young good-prognosis DLBCL patients: Results of the 2 × 2 randomized UNFOLDER trial of the DSHNHL/GLA. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:7574. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Held G, Murawski N, Ziepert M, et al. Role of radiotherapy to bulky disease in elderly patients with aggressive B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:1112–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.