Abstract

Objective

Adolescent mental health concerns increased during COVID-19, but it is unknown whether early increases in depression and suicide risk have been sustained. We examined changes in positive screens for depression and suicide risk in a large pediatric primary care network through May 2022.

Methods

Using an observational repeated cross-sectional design, we examined changes in depression and suicide risk during the pandemic using electronic health record data from adolescents. Segmented logistic regression was used to estimate risk differences (RD) for positive depression and suicide risk screens during the early pandemic (June 2020-May 2021) and late pandemic (June 2021-May 2022) relative to before the pandemic (March 2018-February 2020). Models adjusted for seasonality and standard errors accounted for clustering by practice.

Results

Among 222,668 visits for 115,627 adolescents (mean age 15.7, 50% female), the risk of positive depression and suicide risk screens increased during the early pandemic period relative to the prepandemic period (RD, 3.8%; 95% CI, 2.9, 4.8; RD, 2.8%; 95% CI, 1.7, 3.8). Risk of depression returned to baseline during the late pandemic period, while suicide risk remained slightly elevated (RD, 0.7%; 95% CI, −0.4, 1.7; RD, 1.8%; 95% CI, 0.9%, 2.7%).

Conclusions

During the early months of the pandemic, there was an increase in positive depression and suicide risk screens, which later returned to prepandemic levels for depression but not suicide risk. Results suggest that pediatricians should continue to prioritize screening adolescents for depressive symptoms and suicide risk and connect them to treatment.

Keywords: depression, pandemic, suicide risk

What's New.

Adolescent mental health concerns have increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, but it is unknown whether early pandemic increases in depression and suicide risk among adolescents have been sustained. We found sustained increases for suicide risk but not depression.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

Adolescent mental health concerns have increased during the COVID-19 pandemic,1 , 2 with abrupt changes including physical distancing, distance learning, and family health and economic concerns disrupting daily routines and adding significant stress. Mental health concerns may be especially high for racially minoritized and lower income adolescents due to systemic racism and differential access to care.3, 4, 5 The pediatric primary care office is an ideal place to screen for depression and suicide risk due to recommendations that adolescents visit annually for a well visit.6 Both the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommend routinely screening adolescents for depression7 , 8; depression screeners often include questions about suicidality. In a prior report comparing early pandemic levels of depressive symptoms and suicide risk to prepandemic levels (prepandemic: June-December 2019; pandemic: June-December 2020), early pandemic increases in depression and suicide risk were documented among adolescents cared for in a large pediatric primary care network.2 However, it is unknown whether these increases have been sustained over time. We examined changes in depression and suicide risk during the COVID-19 pandemic through May 2022.

Methods

Study Population

Using an observational repeated cross-sectional design modeled after an interrupted time series,9 electronic health record (EHR) data from Children's Hospital of Philadelphia's (CHOP) pediatric primary care network were examined for changes in depression and suicide risk during the pandemic. The network includes 31 practices in urban, suburban, and semirural areas of Pennsylvania and New Jersey and provides care for approximately 300,000 patients.10 CHOP routinely screens for depression and suicide risk at annual well visits starting at age 12, following guidelines from the AAP's Bright Futures and the USPSTF.7 , 8 Adolescents aged 12 to 21 years who were screened for depression and suicide risk during at least one preventive care visit between March 2018 to May 2022 were included in the study population.

Outcomes

Depressive symptoms and suicide risk were assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire-Modified (PHQ-9-M).2 , 11 , 12 The PHQ-9-M retains the 9 core items of the PHQ-9, which has been validated with adolescents, with slight modifications to increase the PHQ-9’s relevance for youth depression. The PHQ-9-M also includes an additional 4 supplemental items, 2 of which are focused on suicidality.13, 14, 15 Threshold depressive symptoms were established by a PHQ-9-M score of 11 to 27, indicating moderate-to-severe depression.16 For the primary analysis, suicide risk was assessed by a positive endorsement of either or both of the following 2 suicide risk PHQ-9-M questions: (item 9) “Thoughts that you would be better off dead, or of hurting yourself in some way?” (scored from 0 to 3, where a score of 1 or more was considered a positive endorsement); and (item 12) “Has there been a time in the past month when you have had serious thoughts about ending your life?" (scored as yes/no, where a “yes” response was considered a positive endorsement).2 We conducted several sensitivity analyses using alternative outcome definitions: 1) examining a more severe level of depressive symptoms (PHQ-9-M score of 15–27), 2) assessing suicide risk including the other supplemental suicidality item (item 13, “Have you ever, in your whole life, tried to kill yourself or made a suicide attempt?”) in addition to item 9 and item 12, and 3) assessing suicide risk using only item 12 (past-month serious suicidal thoughts).

Statistical Analysis

We examined 3 periods: March 2018 to February 2020 (prepandemic, 24 months), June 2020 to May 2021 (early pandemic, 12 months), and June 2021 to May 2022 (late pandemic, 12 months). March-May 2020 were excluded due to unusually low visit volume at the start of the pandemic. June 2021 was chosen as the split point between the early and late pandemic periods to correspond with the end of the 2020–21 academic year, during which much of the patient population was attending school remotely, and to enable inclusion of 12 months in each pandemic period. We first descriptively examined and graphed monthly proportions of positive screens in each period. Then, we conducted segmented logistic regression using Stata version 16 to estimate changes in the intercept (level) and slope (monthly trend) for positive depression and suicide risk screens during the early and late pandemic periods, relative to the prepandemic period. The model took the form: log odds (positive screen) = β0 + β1*(time in months) + β2*(pandemic period) + β3*(time in months × pandemic period) + β4*(season). Models included time in months as a continuous variable (estimating the prepandemic trend), a 3-level pandemic indicator variable (prepandemic, early pandemic, late pandemic; estimating the change in intercept), and the pandemic/time interaction term (estimating the change in trend). We accounted for seasonal variation by ensuring a consistent number of months (12 or 24) was included in each period and by including an indicator term for season in the models (coded as: winter: December-February, spring: March-May, summer: June-August, fall: September-November). Results were similar when we instead adjusted for calendar month (data not shown). Standard errors accounted for clustering by primary care practice to account for potential differences in screening practices across sites. Using Stata's “margins” package, results were translated into predicted proportions of adolescents screening positive for depression and suicide risk at the beginning and end of each pandemic period. We then calculated risk differences which compared the risk of positive depression and suicide risk screens predicted by the model in May 2021 (end of the early pandemic period) and May 2022 (end of the late pandemic period) compared to the expected risk, had the prepandemic trend continued unchanged.

Changes in depression and suicide risk were examined overall, and by sex, payor (commercial, public), and race and ethnicity (black, white, other, where “other” includes Hispanic, Asian, and other race patients). Race and ethnicity was included as a marker for exposure to racism, which might impact mental health outcomes differentially given the disproportionate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on minoritized populations.17 Categories were based on classifications in the electronic health record. Hispanic, Asian, and other race patients were collapsed into a single category for statistical analysis due to small sample sizes. Children's Hospital of Philadelphia's IRB determined this study to be exempt from review.

Results

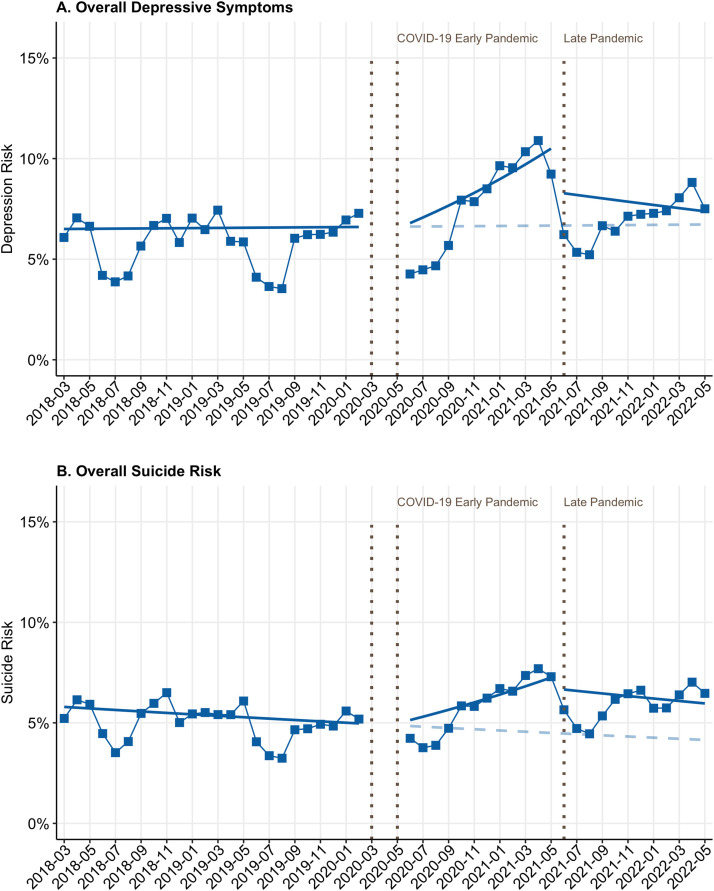

Our analysis included 222,668 visits for 115,627 unique adolescents (mean age: 15.7 years, 49.9% female, 26.6% black, 30.0% publicly insured). The proportion of all primary care visits among adolescents that were preventive visits was 38% in the prepandemic period, 51% in the early pandemic period, and 43% in the late pandemic period. The demographic composition of adolescents was similar across the 3 time periods (Table 1 ). In the prepandemic period, monthly rates of positive depression screens were stable (P value for prepandemic trend: .7) while monthly rates of suicide risk were declining slightly (P = .02) (Figure 1 ).

Table 1.

Population Characteristics at Adolescent Preventive Visits⁎

| Characteristic | Prepandemic N (%) | Early Pandemic N (%) | Late Pandemic N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total visits | 101,288 | 58,931 | 62,449 |

| Positive depression screen | 5738 (5.7) | 4520 (7.7) | 4263 (6.8) |

| Positive suicide risk screen | 4961 (4.9) | 3401 (5.8) | 3628 (5.8) |

| Age—Mean (SD) | 15.2 (2.1) | 15.2 (2.0) | 15.2 (2.1) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 50,531 (49.9) | 29,546 (50.1) | 31,109 (49.8) |

| Male | 50,750 (50.1) | 29,379 (49.9) | 31,333 (50.2) |

| Race and ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 24,641 (24.3) | 13,917 (23.6) | 14,623 (23.4) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 56,535 (55.8) | 31,873 (54.1) | 32,944 (52.8) |

| Hispanic | 6813 (6.7) | 4575 (7.8) | 4956 (7.9) |

| Asian | 4267 (4.2) | 2591 (4.4) | 3126 (5.0) |

| Other race and ethnicity | 9032 (8.9) | 5975 (10.1) | 6799 (10.9) |

| Insurance type† | |||

| Commercial | 73,709 (72.8) | 41,590 (70.6) | 43,827 (70.2) |

| Public | 26,605 (26.3) | 16,759 (28.4) | 17,856 (28.6) |

| Practice location | |||

| Urban | 26,152 (25.8) | 13,997 (23.8) | 15,304 (24.5) |

| Suburban/semirural | 75,136 (74.2) | 44,934 (76.2) | 47,145 (75.5) |

Pandemic periods were as follows: Prepandemic: March 2018–February 2020; early pandemic: June 2020–May 2021; late pandemic: June 2021–May 2022.

Excluding 2322 visits with self-pay, other, or missing insurance information.

Figure 1.

Depression and suicide risk screening outcomes by month. Points reflect percentages of visits where adolescents screened positive for depression/suicidality. Solid lines reflect slopes/intercepts for pre-, early-, and late pandemic periods. Blue dashed lines present counterfactual scenario in which prepandemic trend continued. Vertical dashed lines note the start of the early and late pandemic. Blank area indicates where data were removed.

Depression

Female, non-Hispanic black, and publicly insured adolescents had the highest risk of depressive symptoms in the prepandemic period (Table 2A ). Adjusting for seasonality, the risk of positive depression screens at the end of the early pandemic period was greater than would be expected based on the prepandemic level and trend (Table 1; risk difference (RD), 3.8%; 95% CI, 2.9%, 4.8%). By the end of the late pandemic period, the risk of positive depression screens had returned to prepandemic levels (Table 2A, Figure 1A; RD, 0.7%; 95% CI, −0.4%, 1.7%). This pattern was observed across all demographic subgroups (Table 2A); however, the risk difference during the early pandemic period was largest in magnitude among female adolescents (RD, 6.1%; 95% CI, 4.7%, 7.5%). Patterns were similar for more severe depressive symptoms (PHQ-9-M score of ≥15, Supplemental Table 1).

Table 2A.

Positive Depression Screens at Preventive Visits During the COVID-19 Pandemic†

| Early Pandemic Period |

Late Pandemic Period |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model-Based % Screening Positive in May 2021‡ | Expected % Screening Positive in May 2021 If Prepandemic Trend Continued§ | Risk Difference (95% CI)║ | Model-Based % Screening Positive in May 2022‡ | Expected % Screening Positive in May 2022 If Prepandemic Trend Continued§ | Risk Difference (95% CI)║ | |

| Overall | 10.5 | 6.7 | 3.8 (2.9, 4.8)* | 7.4 | 6.7 | 0.7 (−0.4, 1.7) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 15.5 | 9.4 | 6.1 (4.7, 7.5)* | 11.2 | 9.7 | 1.5 (−0.1, 3.1) |

| Male | 5.5 | 4.1 | 1.4 (0.5, 2.4)* | 3.5 | 3.9 | −0.4 (−1.8, 0.8) |

| Payor | ||||||

| Commercial | 9.1 | 5.4 | 3.7 (2.6, 4.7)* | 6.2 | 5.4 | 0.8 (−0.4, 2.1) |

| Public | 13.6 | 9.7 | 3.9 (2.5, 5.3)* | 10.1 | 9.9 | 0.2 (−1.9, 2.3) |

| Race and ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 9.1 | 5.6 | 3.5 (2.2, 4.7)* | 6.2 | 5.7 | 0.5 (−0.9, 1.8) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 12.7 | 8.7 | 4.0 (2.4, 5.7)* | 9.4 | 8.9 | 0.5 (−2.1, 3.1) |

| Other race and ethnicity¶ | 10.6 | 6.8 | 3.8 (2.2, 5.4)* | 7.8 | 6.8 | 1.0 (−1.2, 3.3) |

P < .05.

Prepandemic was defined as March 2018–February 2020. Data from March through May of 2020 were excluded due to low visit volume. The early pandemic period is June 2020–May 2021. The late pandemic period is June 2021–May 2022.

Estimated using logistic regression and marginal standardization. This represents the predicted percentage of adolescents screening positive for depression at the end of the early and late pandemic periods, adjusting for seasonality.

This represents the predicted percentage of adolescents who would have screened positive for depression at each time point, had the prepandemic trend continued.

Risk differences for the early and late pandemic periods represent the difference between the percentage of adolescents estimated by the model to have screened positive at each time point and the percentage that would have screened positive, had the prepandemic trend continued unchanged.

“Other race and ethnicity” patients include Hispanic, Asian, and other race patients.

Suicide Risk

As with depression, non-Hispanic black, female, and publicly insured adolescents had the highest risk of screening positive for suicidality in the prepandemic period (Table 2B ). The risk of positive suicide screens at the end of the early pandemic period was greater than would be expected relative to the prepandemic level and trend (Figure 1B, Table 2B; RD, 2.8%; 95% CI, 1.7%, 3.8%). However, unlike depression, suicide risk remained above the expected prepandemic levels by the end of the late pandemic period (RD, 1.8%; 95% CI, 0.9%, 2.7%). These patterns were seen for all demographic subgroups except non-Hispanic black adolescents, for whom suicide risk was not significantly elevated relative to the prepandemic trend during either pandemic period. In sensitivity analyses that 1) included the lifetime suicide attempt item from the suicide risk measure or 2) examined past-month serious suicidal thoughts alone, patterns were similar (Supplemental Tables 2–3).

Table 2B.

Positive Suicide Risk Screens at Preventive Visits During the COVID-19 Pandemic†

| Early Pandemic Period |

Late Pandemic Period |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model-Based % Screening Positive in May 2021‡ | Expected % Screening Positive in May 2021 If Prepandemic Trend Continued§ | Risk Difference (95% CI)║ | Model-Based % Screening Positive in May 2022‡ | Expected % Screening Positive in May 2022 If Prepandemic Trend Continued§ | Risk Difference (95% CI)║ | |

| Overall | 7.3 | 4.5 | 2.8 (1.7, 3.8)* | 6.0 | 4.2 | 1.8 (0.9, 2.7)* |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 10.6 | 6.4 | 4.2 (2.9, 5.5)* | 8.3 | 6.1 | 2.2 (0.9, 3.6)* |

| Male | 3.9 | 2.7 | 1.2 (0.2, 2.3)* | 3.5 | 2.3 | 1.2 (0.2, 2.2)* |

| Payor | ||||||

| Commercial | 6.2 | 3.6 | 2.6 (1.6, 3.6)* | 4.7 | 3.3 | 1.4 (0.5, 2.4)* |

| Public | 9.5 | 6.7 | 2.8 (0.8, 4.7)* | 8.7 | 6.4 | 2.3 (0.3, 4.2)* |

| Race and ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 5.7 | 3.3 | 2.4 (1.3, 3.4)* | 4.8 | 2.9 | 1.9 (1.0, 2.7)* |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 8.7 | 7.6 | 1.0 (−0.4, 2.4) | 8.1 | 7.9 | 0.2 (−1.3, 1.8) |

| Other race and ethnicity¶ | 9.0 | 4.0 | 5.0 (3.1, 6.9)* | 6.2 | 3.3 | 2.9 (0.8, 5.0)* |

P < .05.

Prepandemic was defined as March 2018–February 2020. Data from March through May of 2020 were excluded due to low visit volume. The early pandemic period is June 2020–May 2021. The late pandemic period is June 2021–May 2022.

Estimated using logistic regression and marginal standardization. This represents the predicted percentage of adolescents screening positive for suicide risk at the start and end of the early and late pandemic periods, adjusting for seasonality.

This represents the predicted percentage of adolescents who would have screened positive for suicide risk at each time point, had the prepandemic trend continued.

Risk differences for the early and late pandemic periods represent the difference between the percentage of adolescents estimated by the model to have screened positive at each time point and the percentage that would have screened positive, had the prepandemic trend continued unchanged.

“Other race and ethnicity” patients include Hispanic, Asian, and other race patients.

Discussion

During the early months of the pandemic, there was an increase in positive depression and suicide risk screens overall and among most demographic subgroups. This increase coincides with the state of emergency that was declared in March of 2020,18 which resulted in increased stress and uncertainty for many adolescents in the following months. In addition, national events including the murder of George Floyd and the 2020 US presidential election led to social and political turmoil over this period. Also, as of June 2021, over 140,000 children and adolescents in the United States had lost a primary or secondary caregiver to COVID-19, with greater proportional losses among black, Hispanic, and American Indian/Alaskan Native youth.19 COVID-19 has also had documented disparate morbidity and mortality among African American/black and Hispanic populations.20 This might be an additional stressor for adolescents navigating the illnesses and the deaths of family, friends, and community members.

The return of depression rates to prepandemic levels by the end of 2021 aligns temporally with the return to in-person school for much of the study population. The return to in-person learning was markedly delayed for children in underserved and marginalized communities due to the disproportionate impact of both the COVID-19 pandemic and resource strains on minoritized school districts.21 However, we lacked individual-level data on school opening status and acknowledge that resource differences in marginalized communities might contribute to persisting disparities.22 In contrast, suicide risk remained elevated through the late pandemic period, although not as high as in the peak of the early pandemic period. This period coincided with subsequent surges of SARS-COV2 variants and additional, temporary school closures during the Omicron wave.

Prior to the pandemic, rates of adolescent depression and suicidality rose nationally over the past 2 decades,23, 24, 25 potentially due to a complex set of factors such as declining sleep duration, digital media, online bullying, and economic and political upheaval.23 , 26 , 27 In the 2 years directly preceding the pandemic, the proportion of adolescents screening positive for depression was relatively stable in our network, while suicide risk was declining. Though depression and suicide risk did not remain elevated with respect to prepandemic trends among non-Hispanic black adolescents in our study, the higher baseline rates among these adolescents deserves focused attention.28 , 29 Persistent disparities in suicide risk between black and white adolescents warrant equity-focused exploration of drivers and targeted mitigation. Results point to the need for developing and implementing effective suicide prevention interventions for minoritized youth, with a particular emphasis on ensuring that these interventions are acceptable and available to adolescents and families from minoritized populations. Pediatric health care providers can continue to advocate for expanded funding support for pediatric mental health care, universal precautions in trauma-informed care, and ongoing training and hiring practices to support minoritized youth.

The sustained increase in positive suicide risk screens during the pandemic is especially concerning. Given both the concerningly high risk of suicidality in racially minoritized and publicly insured adolescents and the sustained increases during the pandemic among white and commercially insured adolescents, adolescents will benefit from pediatricians continuing to routinely screen patients for both depressive symptoms and suicide risk and connecting them to treatment options. For primary care practices without routine screening procedures, incorporating the PHQ-9-M or another screener with embedded suicide risk questions may be beneficial, since adolescents may endorse suicide risk in the absence of threshold depressive symptoms. Connecting patients to treatment options through referrals is important. However, emerging data indicate that access to behavioral health declined in many parts of the country during the pandemic.30 As such, practice-based strategies including conducting brief interventions and counseling in the primary care office at the time of the visit may be important strategies to implement when risk is identified and as continued advocacy efforts strive to increase access to behavioral health providers.15 , 31 , 32

A strength of our study is that the CHOP primary care network has a large and diverse population of adolescents. However, there are several limitations to note. First, research has found that adolescents are less likely to attend primary care visits than younger children, and thus may be missed in our study population.33 In addition to lower adolescent visits overall, there may also be disparities in visits by race and ethnicity, where racially and ethnically minoritized adolescents in underserved areas may be less likely to present for care.4 Our study population may reflect adolescents who are more easily able to access well-visit appointments. In addition, the proportion of all visits that were preventive varied across study periods, which might have biased results if access to care or other barriers changed across the population over time. Also, a limitation of the PHQ-9-M is that it screens for depressive symptoms instead of diagnosis. In addition, the relatively small sample size limited examination of Asian, Hispanic, and other race adolescents separately. Additionally, adolescents who have severe mental health concerns may also not be seen at primary care and go straight to the emergency department for treatment. Finally, there are inherent limitations to EHR data. We are unable to examine more nuanced reasons for the observed trends without more detailed individual-level data, such as language preference, gender identity, and qualitative data that involves adolescents reporting on their experiences during the pandemic. We also lacked information on contextual factors that may have varied between pandemic periods (eg, socioeconomic status, family composition).

Conclusions

Early in the pandemic, there was an increase in depression and suicide risk overall and among many demographic subgroups. Suicide risk remained elevated longer-term compared to prepandemic trends in the overall population and among most demographic subgroups. The sustained increase in suicide risk speaks to the need for routine screening for depression and suicide risk in primary care, referral to behavioral health treatment, and advocacy to build access to behavioral health care.

Acknowledgments

Financial Disclosure: The other authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Role of Funder/Sponsor: The funders and/or sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the article; or decision to submit the article for publication.

Financial Statement: Funding for this study was provided by the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia Possibilities Project.

Authorship Statement: Dr Stephanie Mayne conceptualized the design of the study, contributed to the interpretation of the data, drafted the manuscript, and led the review and revision of the manuscript.

Chloe Hannan drafted the manuscript, performed all data analyses, contributed to the interpretation of the data, and led the review and revision of the manuscript.

Dr Alexander Fiks conceptualized the design of the study and reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Mary Kate Kelly, Maura Powell, and Dr Molly Davis, Dr Jami Young, Dr Alisa Stephens-Shields, Dr George Dalembert, Dr Katie McPeak, Dr Brian Jenssen all provided substantial contributions to the conception, design, execution, and interpretation of the work, and revised the manuscript.

All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2022.12.006.

Appendix. supplementary data

References

- 1.Jones EAK, Mitra AK, Bhuiyan AR. Impact of COVID-19 on mental health in adolescents: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:2470. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18052470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mayne SL, Hannan C, Davis M, et al. COVID-19 and adolescent depression and suicide risk screening outcomes. Pediatrics. 2021;148 doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-051507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Assari S, Gibbons FX, Simons R. Depression among black youth; interaction of class and place. Brain Sci. 2018;8:108. doi: 10.3390/brainsci8060108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alegria M, Vallas M, Pumariega AJ. Racial and ethnic disparities in pediatric mental health. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2010;19:759–774. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abrams AH, Badolato GM, Boyle MD, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in pediatric mental health-related emergency department visits. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2022;38:e214–e218. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000002221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Academy of Pediatrics. Recommendations for Preventive Pediatric Health Care. 2021. Updated March 2021. Available at: https://downloads.aap.org/AAP/PDF/periodicity_schedule.pdf. Accessed March 9, 2022.

- 7.American Academy of Pediatrics. Addressing Mental Health Concerns in Pediatrics: A Practical Resource Toolkit for Clinicians, 2nd ed. Available at: https://publications.aap.org/toolkits/pages/Mental-Health-Toolkit. Accessed March 3, 2022.

- 8.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Depression in Children and Adolescents: Screening. 2016. Available at:https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/document/RecommendationStatementFinal/depression-in-children-and-adolescents-screening. Accessed March 9, 2022.

- 9.Bernal JL, Cummins S, Gasparrini A. Interrupted time series regression for the evaluation of public health interventions: a tutorial. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46:348–355. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fiks AG, Grundmeier RW, Margolis B, et al. Comparative effectiveness research using the electronic medical record: an emerging area of investigation in pediatric primary care. J Pediatr. 2012;160:719–724. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.01.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis M, Rio V, Farley AM, et al. Identifying adolescent suicide risk via depression screening in pediatric primary care: an electronic health record review. Psychiatr Serv. 2021;72:163–168. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202000207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farley AM, Gallop RJ, Brooks ES, et al. Identification and management of adolescent depression in a large pediatric care network. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2020;41:85–94. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aggarwal S, Taljard L, Wilson Z, et al. Evaluation of modified patient health questionnaire-9 teen in South African adolescents. Indian J Psychol Med. 2017;39:143–145. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.203124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nandakumar AL, Vande Voort JL, Nakonezny PA, et al. Psychometric properties of the patient health questionnaire-9 modified for major depressive disorder in adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2019;29:34–40. doi: 10.1089/cap.2018.0112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.GLAD-PC Toolkit Committee . Guidelines for Adolescent Depression in Primary Care. The REACH Institute; New York, NY: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richardson LP, McCauley E, Grossman DC, et al. Evaluation of the patient health questionnaire-9 item for detecting major depression among adolescents. Pediatrics. 2010;126:1117–1123. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pierce JB, Harrington K, McCabe ME, et al. Racial/ethnic minority and neighborhood disadvantage leads to disproportionate mortality burden and years of potential life lost due to COVID-19 in Chicago, Illinois. Health Place. 2021;68 doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2021.102540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.COVID-19 Disaster Declarations. Available at: https://www.fema.gov/disaster/coronavirus/disaster-declarations. Accessed January 14, 2022.

- 19.Hillis SD, Blenkinsop A, Villaveces A, et al. COVID-19-associated orphanhood and caregiver death in the United States. Pediatrics. 2021 doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-053760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mackey K, Ayers CK, Kondo KK, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in COVID-19-related infections, hospitalizations, and deaths: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:362–373. doi: 10.7326/M20-6306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights . Education in a Pandemic: The Disparate Impacts of COVID-19 on America’s Students. Department of Education; Washington, D.C.: 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams DR, Collins C. Racial residential segregation: a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Rep. 2001;116:404–416. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.5.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keyes KM, Gary D, O'Malley PM, et al. Recent increases in depressive symptoms among US adolescents: trends from 1991 to 2018. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2019;54:987–996. doi: 10.1007/s00127-019-01697-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burstein B, Agostino H, Greenfield B. Suicidal attempts and ideation among children and adolescents in US emergency departments, 2007-2015. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173:598–600. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.0464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Twenge JM, Cooper AB, Joiner TE, et al. Age, period, and cohort trends in mood disorder indicators and suicide-related outcomes in a nationally representative dataset, 2005-2017. J Abnorm Psychol. 2019;128:185–199. doi: 10.1037/abn0000410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaur N, Hamilton AD, Chen Q, et al. Age, period, and cohort effects of internalizing symptoms among US students and the influence of self-reported frequency of attaining 7 or more hours of sleep: results from the monitoring the future survey 1991-2019. Am J Epidemiol. 2022;191:1081–1091. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwac010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Twenge JM, Campbell WK. Associations between screen time and lower psychological well-being among children and adolescents: evidence from a population-based study. Prev Med Rep. 2018;12:271–283. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2018.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davis M, Jones JD, So A, et al. Adolescent depression screening in primary care: who is screened and who is at risk? J Affect Disord. 2022;299:318–325. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Congressional Black Caucus Emergency Taskforce on Black Youth . Suicide and Mental Health. Ring the Alarm: The Crisis of Black Youth Suicide in America. Congressional Black Caucus Emergency Taskforce on Black Youth Suicide and Mental Health; Washington, D.C: 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services . Medicaid & CHIP and the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; Baltimore, MD: 2021. Preliminary Medicaid & CHIP Data Snapshot. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sisler SM, Schapiro NA, Nakaishi M, et al. Suicide assessment and treatment in pediatric primary care settings. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs. 2020;33:187–200. doi: 10.1111/jcap.12282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McDanal R, Parisi D, Opara I, et al. Effects of brief interventions on internalizing symptoms and substance use in youth: a systematic review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2022;25:339–355. doi: 10.1007/s10567-021-00372-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rand CM, Goldstein NPN. Patterns of primary care physician visits for US adolescents in 2014: implications for vaccination. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(2S):S72–S78. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2018.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.