Abstract

TcdB from Clostridium difficile glucosylates small GTPases (Rho, Rac, and Cdc42) and is an important virulence factor in the human disease pseudomembranous colitis. In these experiments, in-frame genetic fusions between the genes for the 255 amino-terminal residues of anthrax toxin lethal factor (LFn) and the TcdB1-556 coding region were constructed, expressed, and purified from Escherichia coli. LFnTcdB1-556 was enzymatically active and glucosylated recombinant RhoA, Rac, Cdc42, and substrates from cell extracts. LFnTcdB1-556 plus anthrax toxin protective antigen intoxicated cultured mammalian cells and caused actin reorganization and mouse lethality, all similar to those caused by wild-type TcdB.

TcdB produced by Clostridium difficile is an important member of the class of large clostridial toxins (LCTs) and is a major virulence factor in pseudomembranous colitis (3). Unfortunately, TcdB, which glucosylates Rho, Rac, and Cdc42 (1), and other LCTs have not been fully utilized or thoroughly studied, since expression of recombinant forms of these toxins in Escherichia coli is difficult. Truncated forms of TcdB have been expressed in E. coli, but they are devoid of receptor binding and translocation activity and thus must be microinjected into target cells and cannot be analyzed in animal models (9). To address these problems, we have utilized a previously described (2, 6) translocation-active, yet nontoxic, form of anthrax toxin to deliver the enzymatic domain of TcdB (TcdB1-556) to the cytosol of mammalian cells. As described below, a truncated form of anthrax toxin lethal factor (LFn) was genetically fused to the enzymatic domain of TcdB and was used in combination with LF's binary partner, protective antigen (PA), to deliver the glucosylating domain to the cytosol of mammalian cells.

Construction, expression, and purification of LFnTcdB1-556.

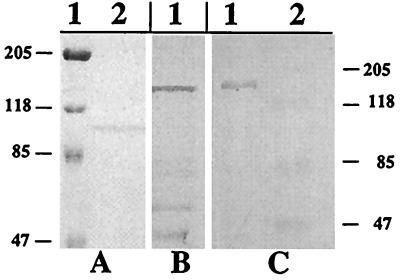

lfn was genetically fused to tcdB1-1668 (the region encoding the enzymatic region of TcdB) by cloning the fragment into the BamHI site of pABII, a derivative of pET15b, which contains the lfn gene with a 3′ multiple cloning site, to make the plasmid pLMS200. This genetic fusion resulted in joining the 3′ end of lfn at the codon TCC encoding S254, followed by sequences within the multiple cloning site which encoded the linker region and a string of residues (PGGGGGS), with the 5′ end of tcdB1-1668 at the ATG codon encoding M1. Candidate clones were transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) (Stratagene), and using the pET15b-encoded six-His tag, the fusion protein was expressed and purified according to manufacturer's instructions (Novagen, Madison, Wis.). In the purification, LFnTcdB1-556 consistently eluted in lower concentrations of imidazole (∼60 mM) compared to Ni2+ affinity isolation of LFn (elutes in ∼250 mM imidazole), suggesting preclusion of the six-His tag by the fusion. Purified LFnTcdB1-556 migrated within the predicted size range (∼94 kDa) by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) analysis and was immunoreactive to both anti-LF and anti-TcdB polyclonal antisera (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis of LFnTcdB1-556. LFnTcdB1-556 was expressed and isolated from E. coli BL-21(DE3). (A) Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE gel showing LFnTcdB1-556 eluted from a Ni2+ affinity column. Lane 1, prestained molecular weight markers; lane 2, purified LFnTcdB1-556. (B) Immunoblot of LFnTcdB1-556 obtained by using rabbit anti-TcdB antiserum. (C) Lane 1, immunoblot of LFnTcdB1-556 obtained by using rabbit anti-LF antiserum; lane 2, prestained molecular weight markers (applies to both panels B and C).

Analysis of LFnTcdB1-556 substrate specificity and cytopathic effects (CPEs).

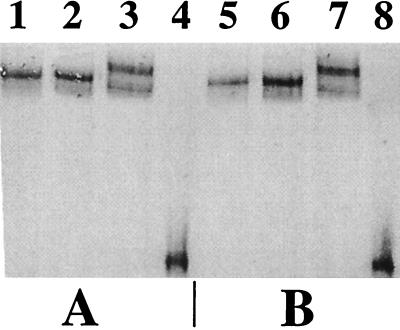

To determine the substrate specificity of LFnTcdB1-556, recombinant Rho, Rac, and Cdc42, as well as cell lysates, were used as targets. Recombinant clones of Rho, Rac, and Cdc42 (a generous gift of Alan Hall) were expressed and purified as glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusions from pGEX2-T according to the manufacturer's instructions (Amersham Pharmacia, Piscataway, N.J.). Chinese hamster ovary (CHO)-K1 (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va.) cell extracts were prepared using a previously described method (5). For the glucosylation assay, CHO cell extracts (2 mg/ml) or GST-RhoA, GST-Rac, and GST-Cdc42 (350-μg/ml concentrations of each) were added to a glucosylation mixture containing 50 mM HEPES, 100 mM KCl, 1 mM MnCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 100 μg of bovine serum albumin/ml, 35 μM [14C]UDP-glucose (308 Ci/mol; ICN Pharmaceuticals Inc., Irvine, Calif.), and 10 μg of TcdB/ml or 15 μg of LFnTcdB1-556/ml in a final reaction mixture volume of 20 μl. The reaction mixture was incubated for 2 h at 37°C, resolved by SDS-PAGE on a 15% acrylamide gel, and imaged on a Packard electronic autoradiograph instant imager (Packard Instrument Company, Meriden, Conn.) similarly to previously described methods (4, 5). As shown in Fig. 2, LFnTcdB1-556 is able to glucosylate recombinant forms of each of the Rho proteins and substrates from cell extracts. The glucosylation profiles for LFnTcdB1-556 and wild-type TcdB were similar, indicating that the fusion maintained substrate specificity similar to that of TcdB. PA and LFn alone did not glucosylate Rho, Rac, Cdc42, or substrates from cell extracts (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

LFnTcdB1-556 (A) and TcdB (B) in vitro glucosylation of Rho proteins and CHO cell lysates. LFnTcdB1-556 and TcdB glucosylation activities were compared using GST fusions of Rho, Rac, and Cdc42 and cell lysates as targets. Lane 1, LFnTcdB1-556 plus GST-Cdc42; lane 2, LFnTcdB1-556 plus GST-Rac; lane 3, LFnTcdB1-556 plus GST-RhoA; lane 4, LFnTcdB1-556 plus CHO cell lysates; lane 5, TcdB plus GST-Cdc42; lane 6, TcdB plus GST-Rac; lane 7, TcdB plus GST-RhoA; lane 8, TcdB plus CHO cell lysates.

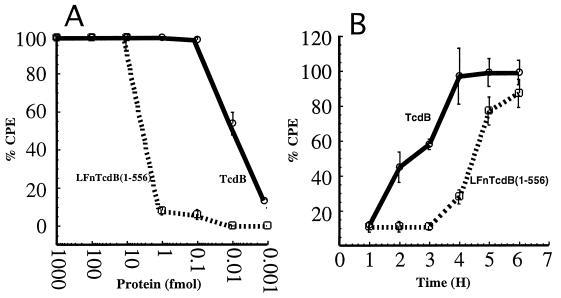

Studies on LFnTcdB1-556 effects on cultured mammalian cells were carried out on CHO cells which were maintained in Ham's F-12 medium (Gibco BRL, Rockville, Md.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. In this assay, PA was maintained at a fixed amount of 30 pmol and dilutions of LFnTcdB1-556 from 0.001 to 1,000 fmol were added to the CHO cells. The cells were incubated for 12 h, and CPEs were determined by visualization. As shown in Fig. 3A, as little as 10 fmol of LFnTcdB1-556 was able to cause CPE, an amount that is approximately 100-fold more than TcdB. Furthermore, the time course of LFnTcdB1-556 CPE was found to be significantly slower than that of TcdB (Fig. 3B). Increased doses of PA plus LFnTcdB1-556 did not dramatically change the time course, suggesting that the system was at saturation (data not shown). Based on the dose assay, we calculated the fusion to have a 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) of 10 fmol when incubated with 30 pmol of PA. PA did not appear to be a limiting factor in these assays, since a 10-fold increase in PA did not change the TCID50 of LFnTcdB1-556.

FIG. 3.

Dose-curve response and time course for LFnTcdB1-556 CPEs. CHO cells were treated with LFnTcdB1-556 and a TcdB control to determine the rate and dose of LFnTcdB1-556 intoxication. (A) Dose-curve comparison for CPE induced by LFnTcdB1-556 plus PA and TcdB. (B) Time course of CPE for LFnTcdB1-556 (100 fmol) plus PA (30 pmol) and TcdB (100 fmol).

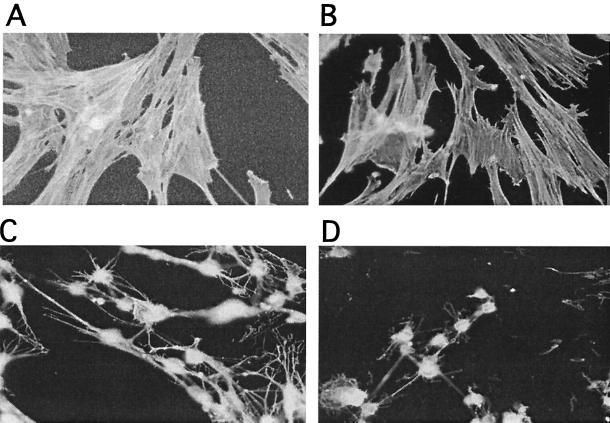

For actin staining studies, human fetal lung fibroblasts (GM05387; NIGMS Human Genetic Mutant Cell Repository, Camden, N.J.) between passages 8 and 21 were grown in complete medium (minimum essential medium with high glucose [Gibco BRL], 200 U of penicillin/ml, and 200 μg of streptomycin/ml). To determine if PA plus LFnTcdB1-556 induces actin condensation similar to that induced by TcdB, the human fibroblasts were treated with 2 TCID50s of LFnTcdB1-556 plus PA. Additionally, controls of TcdB, PA alone, and LFnTcdB1-556 in the absence of PA were tested. Following the initial CPE, the cells were fixed and stained with rhodamine phalloidin as previously described (7) and analyzed using an AX-70 microscope equipped with epifluorescence optics (Olympus America, Inc., Melville, N.Y.). As can be seen in Fig. 4, the actin condensation profiles of PA, LFnTcdB1-556, and TcdB are almost identical.

FIG. 4.

Actin organization in LFnTcdB1-556-treated human fibroblast. Human fibroblasts were treated as follows and were stained with rhodamine phalloidin. (A) Phosphate-buffered saline control; (B) PA plus LFn control; (C) TcdB; (D) LFnTcdB1-556 plus PA.

Curiously, TcdB is 1,000-fold more cytotoxic than TcdA (a second LCT produced by C. difficile), yet both toxins have similar lethal doses (8). In light of this, it seems possible that the cytotoxic or enzymatic domain may not necessarily be the region which confers lethality. Whether the glucosylation domain contributes to lethality has not been determined. Taking advantage of the fact that the PA-LFn system works in both tissue culture and animal models, we tested TcdB1-556 for lethality in BALB/c mice. Test mice (four/group) were injected intravenously with either 1, 10, 100, or 1,000 TCID50s of PA plus LFnTcdB1-556. Control mice were also injected with PA (30 pmol), LFnTcdB1-556 (200 pmol), or a combination of PA (30 pmol) plus LFn (200 pmol). Control mice were not affected by PA or the fusion alone; however, 100% lethality occurred in mice injected with 1,000 TCID50s of PA plus LFnTcdB1-556. These results demonstrate, for the first time, that the glucosylation domain is sufficient for the lethal activity of TcdB.

At approximately 556 residues, the TcdB glucosylating domain is still larger than some full-length bacterial toxins, such as diphtheria toxin (∼58 kDa), making the study of the region in context with the full-length toxin exceptionally difficult. For these reasons, and to simplify as well as expand the studies on TcdB, we took advantage of the anthrax toxin-derived delivery system, PA-LFn. As we have reported, LFnTcdB1-556 plus PA functions much like TcdB and has enzymatic, cytopathic, and lethal effects similar to those of the wild-type toxin. The PA-LFnTcdB1-556 system should provide a useful tool for rapid mutagenesis and in vivo analysis of the TcdB glucosylating domain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aktories K. Rho proteins: targets for bacterial toxins. Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:282–288. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01067-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arora N, Leppla S H. Residues 1-254 of anthrax toxin lethal factor are sufficient to cause cellular uptake of fused polypeptides. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:3334–3341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baldacini O, Girardot R, Green G A, Rihn B, Monteil H. Comparative study of immunological properties and cytotoxic effects of Clostridium difficile toxin B and Clostridium sordellii toxin L. Toxicon. 1992;30:129–140. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(92)90466-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hofmann F, Busch C, Aktories K. Chimeric clostridial cytotoxins: identification of the N-terminal region involved in protein substrate recognition. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1076–1081. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.3.1076-1081.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Just I, Fritz G, Aktories K, Giry M, Popoff M R, Boquet P, Hegenbarth S, von Eichel-Streiber C. Clostridium difficile toxin B acts on the GTP-binding protein Rho. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:10706–10712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milne J C, Blanke S R, Hanna P C, Collier R J. Protective antigen-binding domain of anthrax lethal factor mediates translocation of a heterologous protein fused to its amino- or carboxy-terminus. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:661–666. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parizi M, Howard E W, Tomasek J J. Regulation of LPA-promoted myofibroblast contraction: role of Rho, myosin light chain kinase, and myosin light chain phosphatase. Exp Cell Res. 2000;254:210–220. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.von Eichel-Streiber C, Harperath U, Bosse D, Hadding U. Purification of two high molecular weight toxins of Clostridium difficile which are antigenically related. Microb Pathog. 1987;2:307–318. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(87)90073-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.von Eichel-Streiber C, Meyer zu Heringdorf D, Habermann E, Sartingen S. Closing in on the toxic domain through analysis of a variant Clostridium difficile cytotoxin B. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:313–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17020313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]