Summary

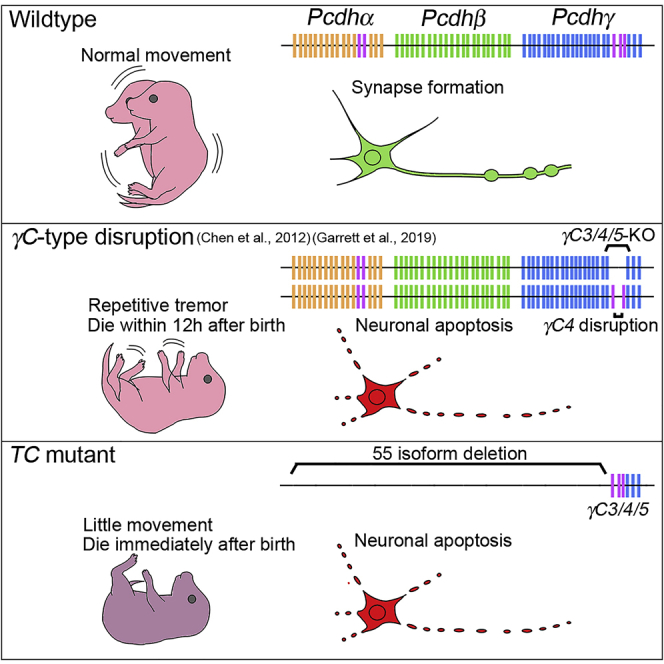

Clustered protocadherin is a family of cell-surface recognition molecules implicated in neuronal connectivity that has a diverse isoform repertoire and homophilic binding specificity. Mice have 58 isoforms, encoded by Pcdhα, β, and γ gene clusters, and mutant mice lacking all isoforms died after birth, displaying massive neuronal apoptosis and synapse loss. The current hypothesis is that the three specific γC-type isoforms, especially γC4, are essential for the phenotype, raising the question about the necessity of isoform diversity. We generated TC mutant mice that expressed the three γC-type isoforms but lacked all the other 55 isoforms. The TC mutants died immediately after birth, showing massive neuronal death, and γC3 or γC4 expression did not prevent apoptosis. Restoring the α- and β-clusters with the three γC alleles rescued the phenotype, suggesting that along with the three γC-type isoforms, other isoforms are also required for the survival of neurons and individual mice.

Subject areas: Cell biology, Developmental genetics, Neuroscience

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

55 cPcdh isoforms other than three γC were necessary for neonatal survival

-

•

TC mutants lacking 55 cPcdh isoforms except three γC exhibited massive apoptosis

-

•

Apoptosis-susceptive regions expressed γC4 and stochastic isoforms combinatorially

-

•

The expression of γC3 or γC4 did not prevent cells from apoptosis in TC mutants

Cell biology; Developmental genetics; Neuroscience

Introduction

The rule governing the connectivity of a neural circuit is pivotal in constructing the brain, and the diversity of cell-surface recognition molecules has been implicated in the regulation of this connectivity. The nervous systems of insects and vertebrates have independently evolved different types of cell-surface recognition molecules with extraordinarily diverse isoforms, namely, Dscam1 in insects1 and clustered protocadherins in vertebrates (cPcdh).2,3,4 This suggests that the utilization of the isoform diversity, not the protein species itself, is essential in constructing the brain. Mice have 58 cPcdh isoforms encoded by three gene clusters, namely, Pcdhα (14 isoforms), Pcdhβ (22 isoforms), and Pcdhγ (22 isoforms).5,6 Individual neurons express a distinct combination of cPcdh isoform subsets in a stochastic manner.7,8,9,10 cPcdh proteins form cis-dimers promiscuously, with preferences for heterologous dimers with other isoforms that increase the variety of recognition units.11,12,13 cPcdh isoforms then interact strictly homophilically in trans at the cell surface of opposing neurons, such as at synapses, creating interaction specificity.12,13,14,15,16,17 Therefore, cPcdh can create cell-surface identity for cell recognition, which leads to the hypothesis that cPcdh works as a synaptic partner-selection molecule. However, this has not been proven at the synapse level yet.

Gene knockout studies targeting each of the three cPcdh clusters have shown that cPcdh plays a role in multiple aspects of recognition events, including axonal projection, dendritic self-avoidance, dendritic arbor complexity, and synapse formation.18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31 Mice lacking all 58 isoforms (Δαβγ mice) exhibit the most severe phenotype. They die immediately after birth due to massive neuronal death and synaptic loss in the brainstem and spinal cord. Genetically blocking apoptosis in Δαβγ mice by deleting the Bax gene cannot rescue neonatal lethality, synaptic defects, or neural circuit malfunction, suggesting that Δαβγ mice have an abnormally wired neural network.32 A similar neonatal lethal phenotype is also observed in Δβγ and Δγ mice, whereas Δα, Δβ, and Δαβ mice can survive, suggesting that Pcdhγ plays a dominant role in neural network formation. However, since the phenotypic severity of neuronal death and synaptic loss increases with the number of deleted clusters (Δγ<Δβγ<Δαβγ), all three Pcdh clusters may cooperatively contribute to neuronal survival and functional neural circuit formation.22

Among the 58 isoforms, the last two isoforms in the Pcdhα cluster and the last three isoforms in the Pcdhγ cluster are distinctly categorized as C-type isoforms based on sequence homology.4 The C-type isoforms are more ubiquitously expressed (although not in all neurons) compared with the other 53 variable isoforms that are stochastically and combinatorially expressed in individual neurons.8,9,10,18,28 Interestingly, the triple γC-type isoform knockout (TCKO), which lacks γC3, γC4, and γC5 isoforms, exhibits a phenotype similar to the Pcdhγ null mutant, whereas the triple γA-type isoform knockout, which lacks γA1, γA2, and γA3 isoforms, shows no discernible abnormalities.33,34 Subsequently, it was shown that γC4 is the only responsible and sufficient isoform for the survival of both neurons and individual mice.35 CRISPR/Cas9-mediated disruption of γC4 caused neuronal apoptosis and neonatal lethality in mice, whereas the disruption of all the other γ isoforms except γC4 resulted in a grossly normal phenotype.35 This raised the question about the role and the necessity of the other 55 isoforms. Thus, in this study, we aimed to generate mutant mice that only express the three γC-type isoforms (TC for triple γC-type) but lacked all the other 55 isoforms including Pcdh α and β.

TC mutants died immediately following birth and exhibited massive apoptotic cell death in a specific brain region of the basal forebrain and in the large area of the brainstem that contains the reticular formation. On the other hand, αβ/TC compound mutants that carry the TC allele complemented with α and β alleles survived to adulthood, indicating that the three γC-type isoforms in the TC allele were functional for individual survival. In situ hybridization (ISH) showed that the wild-type brain regions where apoptotic cell death occurred in TC mutants expressed both γC3 and γC4 isoforms and the stochastic isoforms from the Pcdhα, β, and γ clusters in combination. This result suggests that the essential γC4 isoform is always expressed with the other stochastic isoforms, and this combination is necessary for the survival of neurons and individual mice.

Results

TC mutant neonates die at birth despite the expression of the three γC-type isoforms

A genetically modified TC (triple γC-type) mutant mouse, which lacked 55 cPcdh isoforms from α1 to γA12 but retained only the three C-type isoforms of Pcdhγ, was generated (Figure 1). Briefly, we introduced loxP sites upstream of α1 (loxP-α1MV)22 and downstream of γA12 (Figure 1A; loxP-γA12/C3) by homologous recombination of targeting vectors (Figure S1). A deletion allele lacking the 55 isoforms from α1 to γA12 was generated by Cre-induced meiotic recombination by crossing with mice carrying the Sycp-Cre transgene (Figures 1A and 1B). This deletion protocol also deleted the essential gene Taf7 located between the Pcdhβ- and γ-clusters, the loss of which is known to be early embryonic lethal.36 To restore the additionally deleted Taf7 gene, TC mutant mice were crossed with transgenic mice that harbor the Taf7 transgene (TGtaf7).22 All mice used in this study, including the control (+/+:TGtaf7) and mutants (TC, Δγ, and Δαβγ), carry the Taf7 transgene.

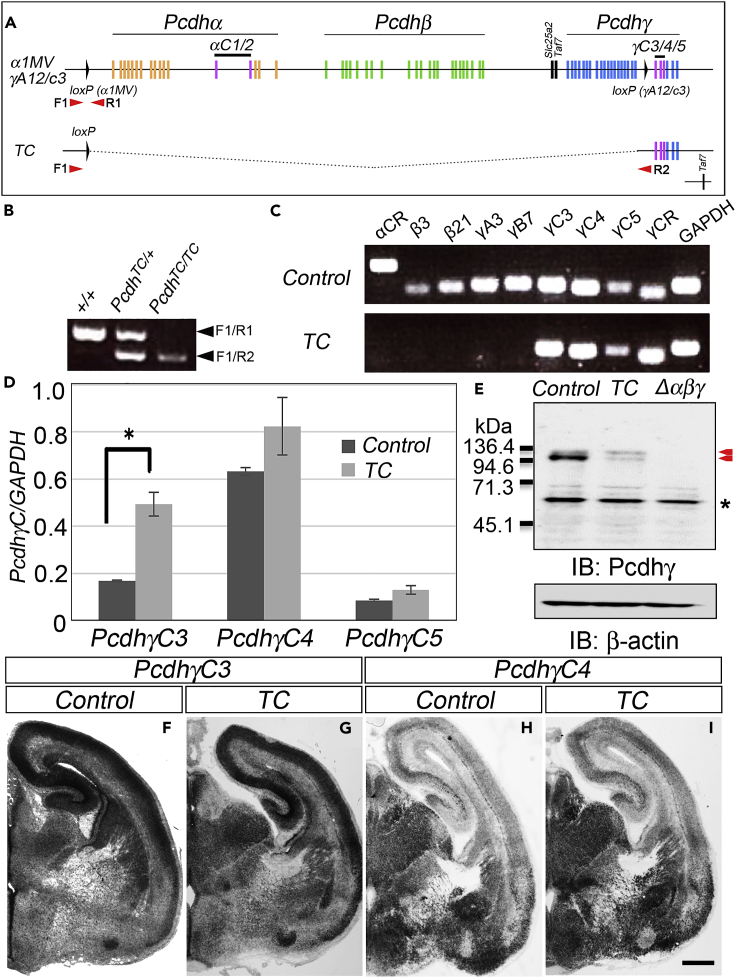

Figure 1.

TC mutants maintain normal expression of the three constitutive γC-type isoforms

(A) Genetic organization of the TC mutant allele. The genomic positions of α1MV loxP and γA12/C3 loxP insertion sites (upper diagram, see also Figure S1). TC mutants were generated by Cre-induced miotic recombination at α1MV and γA12/C3 loxP sites (lower diagram). Arrows indicate primer positions used for genotyping.

(B) PCR genotyping to distinguish between wild-type (+/+) and TC mutant alleles.

(C) RT-PCR analysis showing the expression of γC3, γC4, and γC5 but not the other isoforms in the deleted clusters. αCR and γCR indicates constant region of Pcdhα and γ, respectively.

(D) Quantitative real-time PCR showing the comparable expression of the three γC-type isoforms to control mice (+/+:TGtaf7), although an increase in γC3 expression was noted. N = 3 animals per genotype. Error bars represent SEM ∗p < 0.05 by t-test.

(E) Western blot detection of Pcdhγ isoforms in E18.5 brain lysates from TC mutants by the antibody against the constant region of Pcdhγ (anti-γCR, indicated by red arrowheads). cPcdh-null mutants (Δαβγ) did not express Pcdhγ, whereas TC mutants exhibited a large reduction but still detectable expression from the remaining γC3, γC4, and γC5 loci.

(F-I) In situ hybridization with a γC3 (F, G) or γC4 (H, I) cRNA probe on coronal sections of E18.5 control (F, H) or TC mutant (G, I) brain. Scale bar: 500 μm.

We initially examined the expression of the retained triple γC-type isoforms in TC mutants by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) (Figure 1C). We confirmed the expression of the γC isoforms and that the other isoforms in the deleted region (αCR, β3, β21, γA3, γB7) were not expressed in TC mutants (Figure 1C). Since the deletion of the genomic region 5′ upstream of the γC-type isoforms or the absence of the other 55 isoforms may affect and change the expression of the three γC-type isoforms, we conducted quantitative real-time PCR. The expression of the γC-type isoforms in TC mutants was comparable with that in control (+/+:TGtaf7); no significant change in γC4 and γC5 was observed, whereas higher expression was noted in γC3 (Student’s t test, p < 0.05; Figure 1D). We also examined the spatial expression of γC3 and γC4 mRNA by in situ hybridization (ISH). As shown in Figures 1F-1I, spatial expression patterns of γC3 and γC4 in control mice were retained and did not change in TC mutants. Both isoforms were widely expressed in the brain with more prominent expression of γC3 in the cerebral cortex and higher expression of γC4 in the thalamic region (Figures 1F-1I). The expression of the Pcdhγ protein was probed with the antibody against the constant region of Pcdhγ. The antibody detected all Pcdhγ protein isoforms in the control lysate, which were completely absent in the Δαβγ mutant. The antibody detected Pcdhγ expression in the TC mutant (Figure 1E), confirming that the three γC-type isoforms were translated into proteins. The amount of Pcdhγ protein in the TC mutant was low, which is consistent with the result of quantitative real-time PCR. The large protein reduction was due to the deleted γA- and γB-type isoforms and the remaining signal was due to the maintained expression of triple γC-type protein products (Figure 1E).

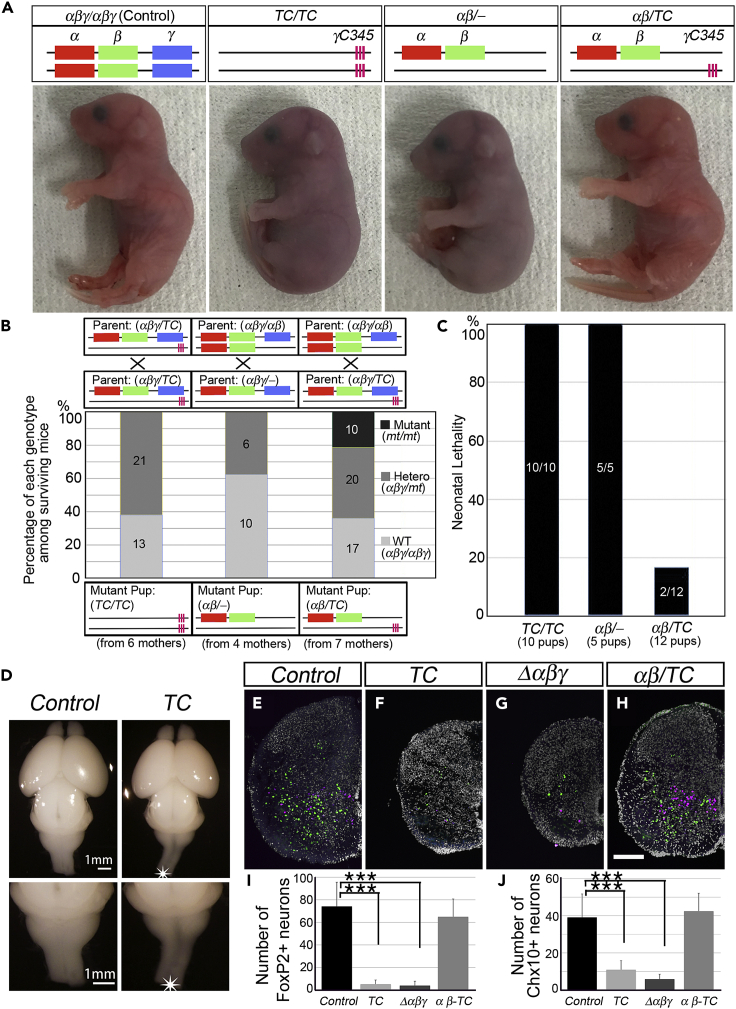

Subsequently, we examined neonatal lethality, which was the salient common phenotype among all the mutant mice that lacked the critical γC4 isoform, such as the Δγ, Δβγ, Δαβγ, TCKO mutants, and ΔγC4 mutant.22,33,35,37 TC mutant mice were born alive; however, they exhibited acromphalus, a hunched posture, shallow breathing, slight movement, and no response to any touch of physical stimuli. Due to severely impaired breathing and blood circulation, the mutants died immediately after birth despite the confirmed expression of the three γC-type isoforms (Figures 2A-2C; TC/TC, Videos S1, and S2). Their phenotype resembled that of Δαβγ and was more severe than that of Δγ mutants, which exhibited a repetitive limb tremor and died within 12 h after birth (Video S1 in Hasegawa et al.22). To confirm that the three γC-type isoforms in TC mutants were functional, we examined whether the TC allele could rescue the neonatal lethality of mutant mice that lacked the three γC-type isoforms. The mutant αβ/- mice lacking Pcdhγ (which was generated by crossing αβγ/αβ mice with αβγ/- mice and retained only a single allele of Pcdhαβ) died after birth (Figures 2A-2C; αβ/-). The behavioral defect of αβ/- mice was more severe than that of Δγ mice (αβ/αβ). The mice exhibited little movement and little response to physical stimuli and died immediately after birth (Video S3). The introduction of a single TC allele into αβ/- mutant mice, such that they harbored a single allele of Pcdhαβ and a single allele of TC (αβ/TC), rescued neonatal lethality (Figures 2A-2C; αβ/TC). The αβ/TC mice were born alive and behaved normally, providing proof of TC allele functionality (Video S4). The αβ/TC mice survived beyond 7 months and were fertile, although their body weights were less than their littermates (at 7 weeks, the body weight of three αβ/TC males was 18.5 g ± 0.5 g, whereas the average weight of the other nine males was 23.1 g ± 1.0 g; the average body weight of four αβ/TC females was 16.8 g ± 0.8 g, whereas the average weight of the other eleven females was 19.2 g ± 1.4 g). The above results clearly showed that the deletion of 55 isoforms was neonatal lethal despite maintaining the functional TC allele and also showed that the three γC-type isoforms require the other isoforms in the Pcdhα and Pcdhβ clusters for the survival of the mice.

Figure 2.

TC mutants died after birth, and neuronal loss was observed in the spinal cord

(A) Gross phenotypes of P0/E19.5 neonatal mice. Mouse genotypes are indicated at the top to represent the retained Pcdh cluster or isoform name for each allele. TC mutants (TC/TC) exhibited a hunched posture and umbilical hernia in most cases and died immediately after birth. The αβ/- mice (lacking γ-cluster) also died after birth, but the αβ/TC mice survived. See also Video S1. Response of a neonatal control mouse (αβγ/αβγ) to tail pinch, related to Figure 2, Video S2. Response of a neonatal TC mutant mouse (TC/TC) to tail pinch, related to Figure 2, Video S3. Response of a neonatal mutant mouse harboring only a single allele of α- and β-clusters (αβ/-) to tail pinch, related to Figure 2, Video S4. Response of a neonatal mutant mouse harboring a single allele of α- and β-clusters and TC allele (αβ/TC) to tail pinch, related to Figure 2.

(B) Percentage of each genotype among the mice surviving 1 h after natural birth or Caesarean delivery. Parent genotypes are indicated at the top, and the resulting mutant genotypes (both mutant alleles) are at the bottom. Parent combinations to generate each mutant were as follows: for TC mutant, αβγ/TC × αβγ/TC; for αβ/- mutant, αβγ/αβ × αβγ/-; and for αβ/TC mutant, αβγ/αβ × αβγ/TC. Graph legend (mt) represents either mutant allele from mated parents. Numbers in the graph indicate the number of mice examined.

(C) Percentage of neonatal lethality in mice with indicated genotype.

(D) Whole brains of E18.5 TC mutants. Note the thinner spinal cord of TC mutants compared with control mice (asterisks).

(E-H) Transverse sections of E18.5 spinal cords immunostained for FoxP2 (green) and Chx10 (magenta). Scale bar: 100 μm. (I, J) Neuron counts for FoxP2+- (I) and Chx10+- (J) neurons in the ventral spinal cord. N = 7 animals for control (+/+:TGtaf7), N = 4 for TC (TC/TC) and for Δαβγ, and N = 5 for αβ/TC mutant (five sections per animal). Data are represented as mean ± SD ∗∗∗p < 0.001 by one-way analysis of variance and Tukey’s post-hoc test.

Massive apoptotic cell death in the brainstem reticular formation in TC mutants

The lack of the three γC-type isoforms (TCKO) was neonatal lethal but also caused massive apoptotic cell death in the spinal cord33,37,38 and brainstem.22 We, therefore, examined whether apoptotic cell death also occurs in TC mutants.

The spinal cords of TC mutants were thinner, suggesting a reduction in neuronal numbers (Figures 2D-2F). Apoptosis was quantified by counting the remaining neurons of two representative neuronal types, namely, V1 inhibitory interneurons (FoxP2-expressing subsets) and V2a excitatory interneurons (Chx10-expressing subsets). The number of surviving FoxP2(+) interneurons and Chx10(+) interneurons in TC mutants was approximately 7.1 and 28.0% that of control mice, respectively, which was comparable to the reduction observed in Δαβγ mutant mice22 (Figures 2I and 2J). Mutant mice carrying a combination of one TC-allele and one αβ-allele (αβ/TC mice) exhibited a normal spinal cord diameter. There was no statistically significant difference in the number of the FoxP2(+) and Chx10(+) interneurons between the control and αβ/TC mice (Figures 2H-2J), indicating that γC3, γC4, and γC5 in the TC-allele are functional for neuronal survival.

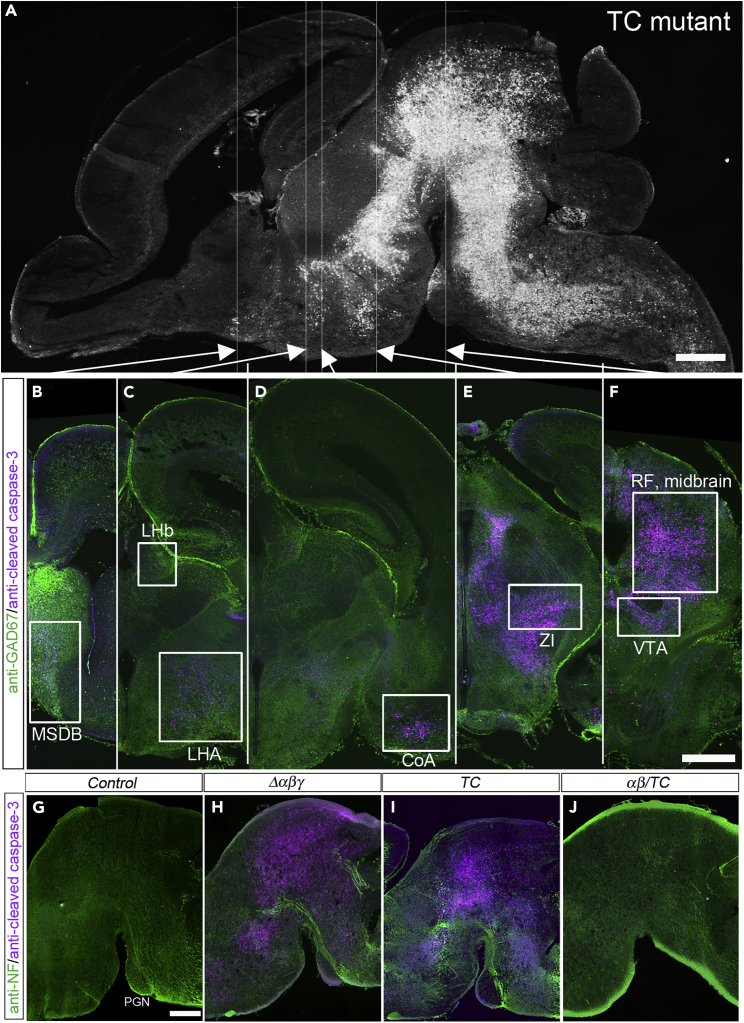

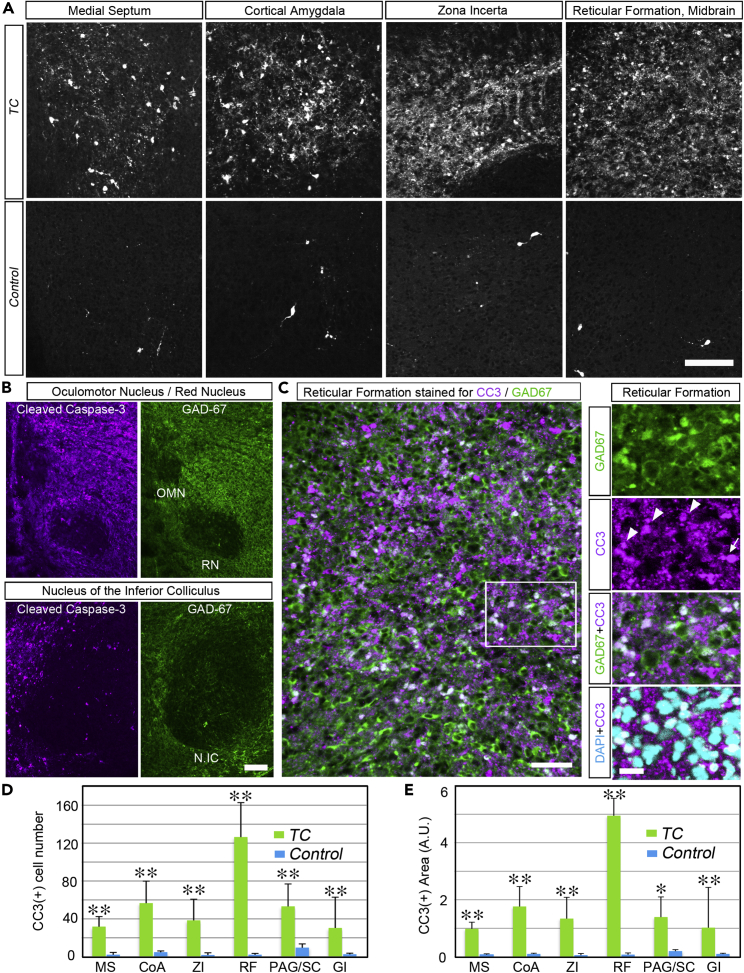

Next, we examined apoptotic cell death in the brain of an E18.5 TC mutant embryo. Figure 3A shows a sagittal section of the whole brain of a TC mutant embryo stained for cleaved-caspase-3 (CC3), a marker of apoptotic cells. Massive cell death was observed in the brainstem (midbrain, pons, medulla oblongata) (Figure 3A). Apoptotic cells were also observed in several specific nuclei in the forebrain (Figures 3B-3E, higher magnification in Figure 4A; Table 1). Examination of coronal sections revealed apoptotic cells in the medial septum-diagonal band (MSDB) (Figures 3B and 4A), lateral habenular nucleus (LHb) (Figure 3C), lateral hypothalamic area (LHA) (Figure 3C), ventral edge of the amygdala (future cortical amygdala, or cortex-amygdala transition zone, hereafter designated as cortical amygdala or CoA) (Figures 3D and 4A), zona incerta (ZI) (Figures 3E and 4A), midbrain reticular formation (Figures 3F and 4A), ventral tegmental area (VTA) (Figure 3F), the area dorsal to the aqueduct including periaqueductal gray (PAG) and superior colliculus, and in the gigantocellular nucleus (Table 1). Co-immunostaining of CC3 and the inhibitory neuronal marker GAD67 showed a correlation between the apoptotic cell death area and GAD67-enriched area. Apoptotic cells were normally observed in GAD67-enriched regions, such as the septum and ZI (Figures 3B and 3E). Conversely, brainstem nuclei with weak GAD67 expression, such as the oculomotor nucleus, red nucleus, and the nucleus of the inferior colliculus, appeared to be devoid of (or had fewer) apoptotic cells (Figure 4B). A subfraction of CC3-positive cells was also GAD67-positive, suggesting that inhibitory neurons were undergoing an apoptotic process (Figure 4C). Quantitative analysis of apoptotic cell numbers or apoptotic cell area (including the area occupied by degenerating neuronal processes) showed that apoptosis also occurred with low frequency in control mice, whereas in TC mutant mice, the frequency increased by more than 10 times (Figures 4A, 4D and 4E). Among the brain regions, the midbrain reticular formation was the most severely affected. Analysis of apoptotic cell distribution suggests that apoptosis occurred in the brainstem reticular formation-centered interconnected neural networks with enriched inhibitory connections.

Figure 3.

Massive apoptosis occurred in the brainstem of TC mutants

(A) A sagittal section of the whole brain of E18.5 TC mutant, immunostained for cleaved-caspase-3 (CC3) (white). Massive cell death occurred in the brainstem. CC3 was expressed not only in the soma but also in degenerating dendrites and axons. Therefore, the degenerating fiber tracts were also stained.

(B-F) Coronal sections of the brain of E18.5 TC mutant immunostained for CC3 (magenta) and GAD67 (green). Sections were arranged in rostro-caudal order from left to right. Rectangle indicates the area exhibiting apoptosis. The rostro-caudal position of each coronal section is indicated by arrows overlaid in the sagittal section in Figure A.

(G-J) Sagittal sections of E18.5 midbrains immunostained for CC3 (magenta) and neurofilament (green). When TC alleles were complemented with a single allele of Pcdhαβ (αβ/TC mutant), apoptotic neuronal death was completely suppressed (J). MSDB, medial septum-diagonal band; LHb, lateral habenular nucleus; LHA, lateral hypothalamic area; CoA, cortical amygdala; ZI, zona incerta; RF, reticular formation; VTA, ventral tegmental area. Scale bars: 500 μm in (A), 500 μm in (B-F), and 250 μm in (G-J).

Figure 4.

Enhanced rate of apoptosis in specific nuclei in TC mutants

(A) Higher magnification views of brain areas exhibiting apoptotic cell death in the coronal section of E18.5 TC mutant and control mice (+/+:TGtaf7). Sections were immunostained for CC3.

(B) Spatial correlation of apoptosis and GAD67 distribution. Paired image of the same visual field immunostained for CC3 (magenta, left) and GAD67 (green, right). Brain areas devoid of massive apoptotic cell death in TC mutants stained less for GAD67.

(C) (Left) Reticular formation of TC mutants double immunostained for CC3 (magenta) and GAD67 (green). (Right) Higher magnification views of the section indicated by the rectangle in the left image, triple stained for GAD67 (green), CC3 (magenta), and DAPI (cerulean). The arrowhead and arrow indicate GAD67(+) and GAD67(−) cells, respectively. DAPI staining was performed to show the location of the cell body.

(D) Quantification of apoptotic cell counts in the fixed region of interest (ROI) for each brain area. CC3 signal with cell somatic diameter that matched with DAPI staining was counted as a cell. Data are represented as mean ± SD. N = 5 animals per genotype. ∗∗p < 0.01 by Mann-Whitney U-test.

(E) Quantification of CC3-stained area (including soma and degenerating neuronal processes) in the fixed region of interest (ROI) for each brain area. The total area of pixels with the above-threshold intensity was measured. Data are represented as mean ± SD. N = 5 animals per genotype. ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗p < 0.05 by Mann-Whitney U-test. Scale bars: 100 μm in (A), 100 μm in (B), 50 μm in (C, left), and 20 μm in (C, right).

Table 1.

List of brain areas where massive or little apoptosis was observed in TC mutants

| Area/Nucleus | Apoptosis |

|---|---|

| Medial septum | +++ |

| Nucleus of the vertical limb of the diagonal band | +++ |

| Lateral hypothalamic area | ++++ |

| Lateral habenular nucleus | ++ |

| Cortical amygdala | ++++ |

| Zona incerta (caudal area) | ++++ |

| Precommissural nucleus | ++ |

| Periaqueductal gray | ++++ |

| Ventral tegmental area (A10) | +++ |

| Substantia nigra (A9) reticular part | ++ |

| Reticular formation, midbrain | +++++ |

| Oculomotar nucleus | void |

| Red nucleus | void |

| Superior colliculus | +++ |

| Reticular formation, pons | +++ |

| Nucleus of the inferior colliculus | void |

| Gigantocellular nucleus | +++ |

| Raphe magnus nucleus (B3) | ++ |

| Inferior olive | void |

“Void” indicates that apoptosis occurred significantly less in these regions compared with the neighboring regions where massive apoptosis was observed.

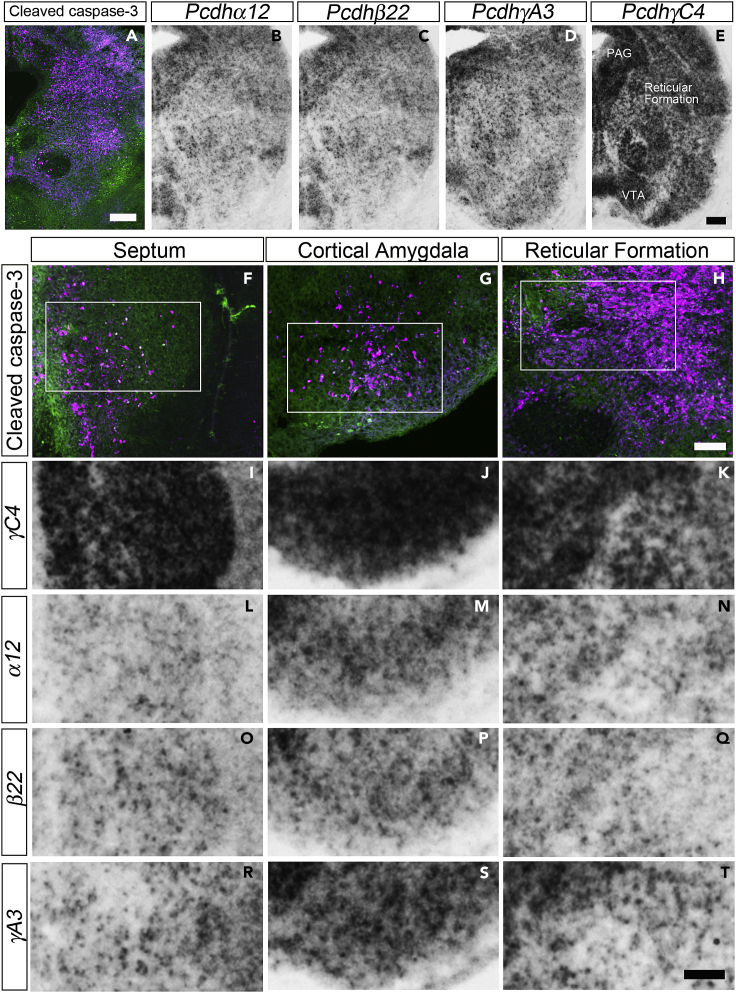

Spatially overlapping expression of cPcdh stochastic and γC4 isoforms

The viability of αβ/TC mice, in contrast to the neonatal death of TC mutants (Figures 2A-2C), suggested that the critical γC4 isoform needs to work in concert with the stochastic isoforms to exert its function. To elucidate the relationships of the spatial expression pattern of the stochastic isoforms and the γC4 isoform, we conducted ISH of representative stochastic isoforms (α12, β22, γA3) and the γC4 isoform (Figure 5). γC4 isoforms were highly expressed in the wide areas in the midbrain including PAG, midbrain reticular formation, and VTA (Figure 5E), where massive apoptosis was observed in the TC mutant (Figure 5A). Stochastic (α12, β22, γA3) isoforms were also expressed in similar areas in the midbrain of control mice, but the expression level of stochastic isoforms was generally very low and sparse (Figures 5B-5D). Figures 5F-5T show representative examples of three brain areas where apoptosis was observed in TC mutants. As clearly shown in the higher magnification view of the septum (Figures 5F, 5I, 5L, 5O, and 5R), cortical amygdala (Figures 5G, 5J, 5M, 5P, and 5S), and the reticular formation in the midbrain (Figures 5H, 5K, 5N, 5Q, and 5T), the γC4 isoform was expressed in the vast majority of cells in these regions (Figures 5I-5K), whereas the α12, β22, and γA3 isoforms were stochastically and sparsely expressed (Figures 5L-5T). This expression pattern was also observed in other brain areas, such as the LHb and the VTA (data not shown). These results clearly show that the corresponding control brain regions where massive apoptosis occurred in TC mutants not only expressed the essential γC4 but also invariably expressed the stochastic isoforms simultaneously.

Figure 5.

Nuclei susceptible to apoptosis in TC mutants exhibited the combinatorial expression of dominant γC4 and stochastic isoforms

(A) A coronal section of the midbrain of an E18.5 TC mutant at the level of the red nucleus double-stained for CC3 (magenta) and GAD67 (green). Massive apoptosis occurred at the reticular formation.

(B-E) In situ hybridization (ISH) with α12 (B), β22 (C), γA3 (D), and γC4 (E) antisense probes in the coronal sections of the midbrain of a control mouse (+/+:TGtaf7). Sections in B-E were all neighboring sections from the same brain.

(F-T) Magnified view of the three representative brain areas showing massive apoptosis: septum (F, I, L, O, R), cortical amygdala (G, J, M, P, S), and reticular formation in the midbrain (H, K, N, Q, T). (F-H) Double immunostaining for CC3 (magenta) and GAD67 (green). Rectangles are approximate visual fields of images in (I-T). (I-T) ISH of γC4 (I-K), α12 (L-N), β22 (O-Q), and γA3 (R-T) antisense probes in the coronal sections of E18.5 control brain corresponding to the rectangular area in (F-H). ISH signal clearly showed the dominant expression of γC4 in the vast majority of cells and the sparse expression of α12, β22, and γA3 stochastic isoforms. Scale bars: 200 μm in (A), 200 μm in (B-E), 100 μm in (F-H), and 100 μm in (I-T).

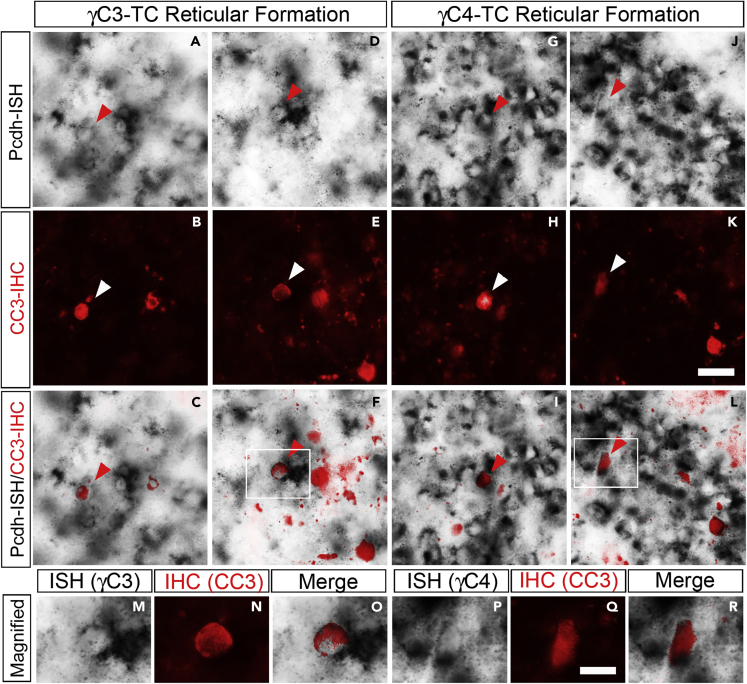

Finally, we examined whether apoptotic cells expressed the γC-type isoforms. For this purpose, we conducted dual immunohistochemistry (IHC) for CC3 and ISH for γC3 or γC4 mRNAs. The spatial expression pattern of the γC-type isoforms in the TC mutant did not change and was the same as that in control mice (Figures 1F-1I). Figure 6 shows a higher magnification view of the ISH signal in the midbrain reticular formation for γC3 (Figures 6A and 6D) and γC4 (Figures 6G and 6J). The density of γC3-expressing cells was a little low compared with γC4, but quite a few cells expressed γC3 (Figures 6A and 6D). As the cells positive for CC3 were undergoing an apoptotic process, the mRNAs in these cells were potentially in the process of degradation. However, we found cells expressing both γC3 and CC3 (Figures 6C and 6F, higher magnification in 6M−6O) and cells expressing both γC4 and CC3 (Figures 6I and 6L, higher magnification in 6P-6R). This result suggests that the expression of either γC3 or γC4 did not ensure cell viability in the TC mutant.

Figure 6.

Expression of γC3 or γC4 did not protect cells from apoptosis in TC mutants

(A-L) Dual staining for in situ hybridization (ISH) for γC-type isoforms (gray scale) (A, D, G, J) and immunostaining for CC3 (red) (B, E, H, K) of the brain sections of the reticular formation of an E18.5 TC mutant. (C, F, I, L) Merged images of CC3 signals overlaid on ISH signals. Both γC3-expressing cells (A-F, arrowheads) and γC4-expressing cells (G-L, arrowheads) were undergoing apoptosis.

(M-R) Magnified view of γC3-expressing cells (M−O) in the rectangular area in (F), and γC4-expressing cells (P-R) in the rectangular area in (L), expressing the apoptotic marker CC3. Scale bars: 20 μm in (A-L) and 10 μm in (M-R).

Discussion

We examined the phenotype of TC mutant mice lacking 55 cPcdh isoforms except the essential three γC-type isoforms. The mice died immediately after birth and exhibited massive neuronal death despite the presence of the functional TC allele. This finding suggests that the three γC-type isoforms were not sufficient to rescue the neuronal defects of clustered Pcdh-null mice (Δαβγ), and other cPcdh isoforms are also required for the survival of neurons and individual mice.

Apoptosis was also observed in control mice in the same brain regions as TC, albeit the frequency of apoptotic cells was very low in control (Figures 4A and 4C). This suggests that apoptotic cell death is a normal developmental process that occurs during neural network wiring. Massive apoptosis occurs in the absence of cPcdh (Δαβγ mouse),22 suggesting that the default strategy of neural network formation in the brainstem and spinal cord is to exclude inappropriate cells by apoptosis and that cPcdh provides the survival signal. PcdhγC4 has been shown to be essential for the survival signal.33,35 However, in TC mutants, the expression of PcdhγC4 did not ensure neuronal survival. At least the following three explanations are possible.

The first possibility is that PcdhγC4 is nonfunctional in TC mutants due to the failure in cell surface trafficking, It has been shown that certain cPcdh isoforms including PcdhγC4, the stochastic isoforms in Pcdhα (α1-12) and PcdhαC1, cannot translocate to the cell surface by themselves (when expressed alone). PcdhγC4 requires another carrier isoform to form a cis-dimer to enable its translocation to the cell surface.11,12,17 TC mutants express both γC3 and γC5 isoforms as potential carriers. However, γC5 expression was low at the prenatal stage, and the expression of γC3 was, to our surprise, rather sparse compared to γC4 in the apoptotic brain regions. Therefore, in TC mutants, the remaining γC3 and γC5 may not be enough for γC4 cell surface expression. This must be addressed in the future.

A second possibility is that the deleted isoforms in TC (Pcdhα1 to PcdhγA12) are also critical for the survival of neurons and individual mice. Although the γC4 appeared as the only critical isoform, requirement of other isoforms has also been reported. The severity of apoptosis in the Δγ mutant was augmented by the additional deletion of Pcdhα and/or Pcdhβ, suggesting the contribution of α- and β-isoforms.22,39 Ing-Esteves et al., reported dose- (allele number) dependent effects of Pcdhα and Pcdhγ cluster deletions on retinal survival.39 We also observed the allele number-dependent effects of Pcdhα and Pcdhβ clusters on neonatal survival; the Δγ mutant (αβ/αβ) exhibited repetitive limb tremor and died within 12 h, while the αβ/- mutant exhibited little movement and died immediately after birth. The requirement of γC4 might be attributable to it being the most dominantly expressed isoform in the apoptotic brain areas. The simultaneous loss of a bunch of other stochastic isoforms with low expression may also cause the lowering of the survival signal below the required threshold.

A third possibility is that the cis-dimer of PcdhγC4 and another isoform acts as the functional unit and exerts its antiapoptotic signal. A disadvantageous feature of γC4 is that it alone cannot be transported to the cell surface and requires another isoform (forming a cis-heterodimer) for its cell surface delivery. Therefore, the generation of the survival signal of γC4 is linked to the diversity of cell-surface recognition ability. Our expression study at E18 indicated that the essential γC4 isoform is always expressed with other stochastic isoforms, which is consistent with the above idea. The defect observed in TC mutants supports that the γC4 requires other isoforms (included in deleted 55 isoforms). Whether there is a specific carrier isoform, or in fact 55 isoform variety is required, awaits further study.

Neuronal types whose survival depends on cPcdh have been reported in many brain areas, such as spinal cord interneurons, brainstem neurons, cortical interneurons, retinal neurons.22,32,34,38,39,40 Here, we mapped the cPcdh-dependent neurons in the forebrain and midbrain at E18. The cell death areas include the MSDB, LHb, LHA, cortex-amygdala transition zone, ZI, VTA, PAG, and midbrain reticular formation, which were directly connected according to the previous studies.41,42,43,44,45 Therefore, apoptotic cell death area appeared as a directly connected single mass of neural network. This suggests that the apoptotic cell death in TC mutants was correlated with network organization and may be correlated with its activity.

GABAergic interneurons are a major apoptotic cell type found in the Δγ mutant. There exists a correlation between the severity of neuronal loss (reduction volume of the tissue) and abundance of GABAergic neurons (GAD2 expression).22,34,37,38,40 We also found that the spatial distribution of CC3-positive apoptotic cells in the E18 TC mutant closely resembles that described in published ISH data for GAD1/GAD2 (available on Allen Brain Atlas; https://portal.brain-map.org).46 The distribution of CC3-positive cells in TC mutants also resembles (although not exactly) the staining pattern of acetylcholine esterase (AChE) in the coronal plane of the E15/16 mouse brain (as reported in the mouse brain atlas by Jacobowitz and Abbott47). These correlations suggest that the cell death area is enriched with GABAergic neurons and generally receives cholinergic input.

It has been shown that synchronized rhythmic activity, which is distinct from the activity of a mature circuit, occurs at many sites in the developing nervous system.48 This activity has been extensively studied in the spinal cord; a wave of the synchronized rhythmic activity is propagated over the entire network, driven by both GABAergic and cholinergic inputs, and has been considered a general necessary program of neural circuit wiring.48,49,50,51,52,53 Massive apoptosis in the developing spinal cord of Pcdh-deficient mice (such as TC and Δαβγ) occurred after the cessation of synchronized rhythmic activity.22,53 The close spatial correlation of apoptotic cell distribution in TC mutants with that of GABAergic neurons and AChE and the temporal correlation of the onset of apoptosis and the cessation of a synchronized rhythmic activity suggest that embryonic rhythmic activity may be a prerequisite for the cPcdh-mediated survival signal. Determining whether synchronized neuronal activity plays a role in cell surface trafficking of cPcdh, which generates the survival signal, or whether the activity of the network whose wiring is regulated by cPcdh itself governs neuronal survival, requires further study. Taken together, the γC-type isoforms appeared to regulate neuronal survival by cooperating with other cPcdh isoforms, the molecular mechanism of which should be clarified in the future.

Limitations of the study

In this study, we have shown that the three PcdhγC-type isoforms (γC3, γC4, γC5) were insufficient to prevent neuronal apoptosis and neonatal death of TC mutant mice. This result suggests that the critical γC4 isoform requires other Pcdh isoforms to play a role in the survival of neurons and mice. However, the molecular mechanisms are still unclear. The cell surface expression of γC4 isoform, the actual entity of cis-dimer/multimer Pcdh complex, and the downstream signaling cascade need to be clarified in the future. The differential role of γC4 and other stochastic isoforms will be elucidated in the future by re-introducing stochastic isoforms to the TC allele.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Anti-cleaved-caspase-3 | Cell Signaling Technology | #9661; RRID:AB_2341188 |

| Anti-GAD67 | Millipore | #MAB5406; RRID:AB_2278725 |

| Anti-Chx10 | Santa Cruz | #sc-21690; discontinued |

| Anti-FoxP2 | Sigma-Aldrich | #HPA000382; RRID:AB_1078908 |

| Anti-pan axonal-neurofilament (SMI312) | Covance | #SMI312; discontinued |

| Guinea pig anti-PcdhγCR antibody | produced by CBSN, Hasegawa et al. (2016) | N/A |

| Anti-β-actin | Sigma-Aldrich | #A5441; RRID:AB_476744 |

| Anti-digoxigenin-AP Fab fragments antibody | Sigma-Aldrich | #11093274910; RRID:AB_2734716 |

| Goat anti-mouse IgG Alexa Fluor Plus 488 | ThermoFisher | #A32723; RRID:AB_2633275 |

| Goat anti-rabbit IgG Alexa Fluor Plus 594 | ThermoFisher | #A32740; RRID:AB_2762824 |

| Donkey anti-goat IgG Alexa Fluor 594 | ThermoFisher | #A11058; RRID:AB_2534105 |

| Donkey anti-rabbit IgG Alexa Fluor 488 | ThermoFisher | #A21206; RRID:AB_2535792 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| TRIzol reagent | ThermoFisher | Cat#15596018 |

| DNaseI (RNase-free) | TaKaRa Bio, Inc. | Cat#2270A |

| Superscript III reverse transcriptase | ThermoFisher | Cat#18080093 |

| SYBR Premix Ex Taq | TaKaRa Bio, Inc. | Cat#RR420A, discontinued |

| ECL Select | Cytiva | Cat#RPN2235 |

| Diethyl pyrocarbonate | Nacalai Tesque, Inc. | Cat#12311-86 |

| Ribonuclease inhibitor (porcine liver) | TaKaRa Bio, Inc. | Cat#2311A |

| T7 RNA polymerase | Promega | Cat#PR-P2075 |

| T3 RNA polymerase | Promega | Cat#PR-P2083 |

| DIG RNA labeling mix | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#11277073910 |

| ProtectRNA RNase inhibitor | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#R-7397 |

| Formamide, deionized, nuclease and protease tested | Nacalai Tesque, Inc. | Cat#16345-65 |

| 4-Nitro blue tetrazolium chloride | Roche | Cat#11383213001 |

| 5-Bromo-4-chloro-3-indoyl-phosphate | Roche | Cat#11383221001 |

| Paraformaldehyde | Nacalai Tesque, Inc. | Cat#02890-45 |

| Low melting temperature gelatin | Nippi | Cat#MAX-F |

| Tissue-Tek O.C.T. compound | Sakura Finetek | N/A |

| Immunoselect antifading mounting medium | Dianova | Cat#SCR-038447 |

| Proteinase K | Nacalai Tesque, Inc. | Cat#29442-85 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Mouse: C57BL/6 PcdhabgTC/+:TGTaf7 | This study | RIKEN BRC, RBRC09813 |

| Mouse: C57BL/6 Pcdhabgdel/+:TGTaf7 | Hasegawa et al. (2016) | RIKEN BRC, RBRC04820 |

| Mouse: C57BL/6 Pcdhgdel/+:TGTaf7 | Hasegawa et al. (2016) | RIKEN BRC, RBRC04821 |

| Mouse: C57BL/6 TGTaf7 | Hasegawa et al. (2016) | RIKEN BRC, RBRC04822 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| For Southern blot probe A, B sequence, see Table S1 | This study | N/A |

| For genotyping PcdhabgTC allele, see Table S1 | This study | N/A |

| For genotyping TGTaf7 allele, see Table S1 | This study | N/A |

| For RT-PCR/real-time RT-PCR, see Table S1 | This study | N/A |

| For amplifying in situ hybridization RNA probes, see Table S1 | This study | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| ImageJ ver1.53 | NIH | N/A |

| PRISM 7.05 | GraphPad | N/A |

| Other | ||

| ImageQuant LAS-4000 | Cytiva | LAS-4000 |

| ABI 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System | Applied Biosystems | 7900HT |

| Leica CM3050 cryostat | Leica | CM3050 |

| DS-Qi1Mc digital camera | Nikon | DS-Qi1Mc |

| BIOREVO BZ-9000 All-in-one Fluorescence Microscope | Keyence Corp. | BZ-9000 |

| Dragonfly | Andor, Oxford Instruments, Belfast, Northern Ireland | https://andor.oxinst.com/products/dragonfly-confocal-microscope-system |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Takeshi Yagi (yagi@fbs.osaka-u.ac.jp).

Material availability

TC mutant mouse lines generated in this study have been deposited to RIKEN BRC (https://web.brc.riken.jp/en/)54 (strain: B6; TT2-Pcdh<dla1-gA12>/B6-Tg(Taf7): RBRC09813).

Experimental model and subject details

Animals

All animal procedures were performed according to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the Science Council of Japan and were approved by the Animal Experiment Committee of Osaka University and the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of RIKEN Kobe Branch. Adult (beyond 2 months old) male and female PcdhTC/+:TGTaf7, Pcdhabgdel/+:TGTaf7 (Hasegawa et al.22), Pcdhgdel/+:TGTaf7 (Hasegawa et al.22), and Pcdh+/+:TGTaf (Hasegawa et al.22) mice in a C57BL/6 background were used and maintained in the animal facility of Osaka University. Mice were housed in groups under a 12 h:12 h light:dark cycle. Control mice (+/+:TGtaf7) were the littermates of heterozygous breeding for each genotype. All mouse strains used in this study were deposited in RIKEN BRC, Japan.

Method details

Generation of TC mutant mice

We introduced loxP sites upstream of α1 (loxP-α1MV)22 and downstream of γA12 (loxP-γA12/C3; Figures 1A and S1A). Recombinant embryonic stem (ES) cell clones carrying the mutant allele were screened using Southern hybridization (Figure S1, Table S1). The mouse carrying the loxP-γA12/C3 allele was generated and is maintained at RIKEN BRC (PcdhγA12/C3 (α1MV ES): Accession No. CDB1149K: https://large.riken.jp/distribution/mutant-list.html). A deletion allele lacking 55 isoforms from α1 to γA12 (TC-allele) was generated by Cre-induced meiotic recombination by crossing with mice carrying Sycp-Cre transgene. The initially produced mutants contained an additional deletion of the Taf7 gene located between the Pcdhβ and Pcdhγ clusters, the deletion of which is early embryonic lethal.36 To rescue the Taf7 gene, the mutants were crossed with a TGtaf7 mouse line containing Taf7 transgene.22 Genotyping of the TC allele was performed with primers listed in Table S1: α1-232F and Pcdhα1R1 primers for wild-type allele (721 bp product), and α1-232F and gA12C3intron4846R primers for TC allele (553 bp product). Δγ and Δαβγ mutant mice, both rescued with Taf7 transgene, were generated, and described in detail in our previous study.22 We performed all experiments using TC mutant, Δγ, Δαβγ, and control (+/+:TGtaf7) mice.22

RT-PCR, real-time qRT-PCR, and immunoblot analysis

The primer sequences used for RT-PCR and real-time qRT-PCR are listed in Table S1. Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen), and cDNA was synthesized with the Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). The PCR reactions were performed in GC buffer I (TaKaRa, Japan). Quantitative RT-PCR analysis was conducted with SYBR Premix Ex Taq (TaKaRa Bio, Inc., Japan) using ABI 7900HT (Applied Biosystems). Immunoblot analysis was performed as follows. Mouse brains were homogenized in 0.32 M sucrose containing 1 mM EDTA and 1 mM PMSF. The homogenate was spun at 800 × g for 10 min, and the collected supernatant was spun at 20,000 × g for 30 min to obtain the pellet fraction. The pellet fraction was lysed with SDS sampling buffer (60 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.7, 2% SDS, 2% 2-mercaptoethanol, and 5% glycerol), and the proteins were separated by 7.5% SDS-PAGE. After the proteins were blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes, the membranes were reacted with the following antibodies: guinea pig anti-PcdhγCR antibody (produced by CBSN) and anti-β-actin (Sigma).

Neonatal lethality assay

The survival or lethality of P0/E19.5 mice was judged as follows. The survival of P0 pups within 1 h after natural birth was judged by breathing, blood circulation, body color, behavior, and response to tail pinch. As the TC mutants died immediately after birth, some mothers abandoned efforts to nurse the other healthy littermates. To exclude the effect of negligence by the mother, we also examined the survival or lethality of E19.5 mice delivered by Cesarean section, similarly judged by breathing, blood circulation, body color, behavior, and response to tail pinch, at 1 hour after resuscitation. Responses to tail pinch of all pups were video recorded.

IHC

Embryonic day 16-18 mouse embryos were transcardially perfused with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS. After decapitation and removal of the dorsal cranium to expose the brain, the heads were post-fixed overnight at 4 °C. The brains were then removed, and after cryoprotection in 30% sucrose, they were embedded in O.C.T. compound (Sakura Finetek Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and quickly frozen in isopentane cooled with liquid nitrogen. Cryosections of 20-μm thickness were cut on a cryostat (Leica CM3050, Germany). IHC was performed with the following antibodies: anti-CC3 (Cell Signaling Technology); anti-GAD67 (Millipore); anti-Chx10 (Santa Cruz); anti-FoxP2 (Sigma), and anti-pan axonal-neurofilament (SMI312, Covance). Secondary antibodies conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 or 594 were obtained from Molecular Probes.

ISH, dual ISH-IHC staining

For ISH, fresh-frozen specimens were used. Briefly, whole brains of E18.5 embryos were dissected out, embedded in 1:2 mixture of 5% fish gelatin in PBS and O.C.T. compound, and immediately frozen in isopentane cooled with liquid nitrogen. After cutting cryosections of 30-μm thickness, sections were post-fixed with 4% PFA for 10 min, acetylated, and hybridized with digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled antisense probes (1-1.5 μg/mL) to each cPcdh isoform mRNA at 72 °C overnight. The probe signals were detected using alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-DIG antibodies with nitroblue tetrazolium and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate as a chromogenic substrate. For the dual staining of ISH and IHC, perfusion-fixed brains with 4% PFA were used. Cryosections of 30-μm thickness were similarly processed and hybridized with DIG-labeled antisense probes. After washing out the probes, sections were incubated with anti-CC3 antibodies and alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-DIG antibodies. The alkaline phosphatase color reaction was conducted, followed by the reaction of the Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody to detect the CC3 antibody.

Imaging and data analysis

Bright field images were captured using the BX51 microscope (Olympus) equipped with DS-Qi1Mc digital camera (Nikon). Fluorescent images were captured using the BX51 microscope with DS-Qi1Mc, using the BZ9000 microscope (Keyence Corp., Japan), or using the Dragonfly confocal laser microscope (Oxford Instruments, UK). Quantification of FoxP2- or Chx10-neuron counts in the spinal cord was performed as previously described.22 Briefly, five cryosections of 20 μm thickness with a 320 μm interval were collected from the lumbar spinal cord (L3-L6 level) per animal, and the number of FoxP2(+) or Chx10(+) cells were counted for each hemicord section. For the quantification of CC3-stained neuronal counts and areas, a ROI of 625 μm × 625 μm field size was set for each brain region in the brain hemisphere. An Alexa 594-detected CC3 image and a DAPI-stained nucleus image on the same z-plane were taken for each brain region with the Dragonfly confocal laser microscope. Images were then processed with ImageJ 1.53 software for background subtraction and for thresholding the images. To count cell numbers, particles of the same size as nucleus that were double-positive for CC3 and DAPI staining were counted. To quantify CC3-positive areas, the total area of pixels with above-threshold intensity was measured. Particles corresponding to staining noise were excluded by setting the threshold for particle size. Statistical analysis was conducted using Prism 7.05 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA).

Quantification and statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using Prism 7.05 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). The data are expressed as the mean ± SD. For the analysis in Figures 2I and 2J, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s post-hoc test was applied. For the analysis in Figures 4D and 4E, Mann–Whitney U–test was applied. p Values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. The details for each experiment including the number of animals are specified in the figure legends.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Sonoko Hasegawa, Yukinori Inoue, and Yoshito Sakaij for their assistance with the animal models. This work was supported by the MEXT Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (A) from JSPS (No. 18H04016) to T.Y., Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas “Integrated analysis and regulation of cellular diversity” (No. 20H05035) to T.Y., Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Transformative Research Areas (A) “Adaptive Circuit Census” (22H05498) to T.Y. from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, and Culture of Japan, and in part by the Planned Collaborative Project and the Cooperative Study Program of the National Institute for Physiological Sciences, Japan.

Author contributions

H.Ko., K.T., and T.Y., project design and conceptualization. H.Ko. and T.Y., co-writing-original draft. K.T., data collection and analysis in the spinal cord. H.Ko., data collection and analysis in the brainstem. M.S., M.H., Ta.H., Te.H., H.Ki., and T.A., resources. T.Y., supervision and funding acquisition.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: January 20, 2023

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2022.105766.

Supplemental information

Data and code availability

-

•

All data are available in the manuscript or supplemental information.

-

•

All codes are available in the supplemental information.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

References

- 1.Hattori D., Millard S.S., Wojtowicz W.M., Zipursky S.L. Dscam-mediated cell recognition regulates neural circuit formation. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2008;24:597–620. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.24.110707.175250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kohmura N., Senzaki K., Hamada S., Kai N., Yasuda R., Watanabe M., Ishii H., Yasuda M., Mishina M., Yagi T. Diversity revealed by a novel family of cadherins expressed in neurons at a synaptic complex. Neuron. 1998;20:1137–1151. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80495-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mountoufaris G., Canzio D., Nwakeze C.L., Chen W.V., Maniatis T. Writing, reading, and translating the clustered protocadherin cell surface recognition code for neural circuit assembly. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2018;34:471–493. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100616-060701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu Q., Maniatis T. A striking organization of a large family of human neural cadherin-like cell adhesion genes. Cell. 1999;97:779–790. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80789-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yagi T. Molecular codes for neuronal individuality and cell assembly in the brain. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2012;5:45. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2012.00045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zipursky S.L., Sanes J.R. Chemoaffinity revisited: dscams, protocadherins, and neural circuit assembly. Cell. 2010;143:343–353. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Almenar-Queralt A., Merkurjev D., Kim H.S., Navarro M., Ma Q., Chaves R.S., Allegue C., Driscoll S.P., Chen A.G., Kohlnhofer B., et al. Chromatin establishes an immature version of neuronal protocadherin selection during the naïve-to-primed conversion of pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Genet. 2019;51:1691–1701. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0526-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Esumi S., Kakazu N., Taguchi Y., Hirayama T., Sasaki A., Hirabayashi T., Koide T., Kitsukawa T., Hamada S., Yagi T. Monoallelic yet combinatorial expression of variable exons of the protocadherin-α gene cluster in single neurons. Nat. Genet. 2005;37:171–176. doi: 10.1038/ng1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirano K., Kaneko R., Izawa T., Kawaguchi M., Kitsukawa T., Yagi T. Single-neuron diversity generated by protocadherin-β cluster in mouse central and peripheral nervous systems. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2012;5:90. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2012.00090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaneko R., Kato H., Kawamura Y., Esumi S., Hirayama T., Hirabayashi T., Yagi T. Allelic gene regulation of Pcdh-α and Pcdh-γ clusters involving both monoallelic and biallelic expression in single Purkinje cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:30551–30560. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605677200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodman K.M., Rubinstein R., Dan H., Bahna F., Mannepalli S., Ahlsén G., Aye Thu C., Sampogna R.V., Maniatis T., Honig B., Shapiro L. Protocadherin cis-dimer architecture and recognition unit diversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:E9829–E9837. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1713449114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goodman K.M., Katsamba P.S., Rubinstein R., Ahlsén G., Bahna F., Mannepalli S., Dan H., Sampogna R.V., Shapiro L., Honig B. How clustered protocadherin binding specificity is tuned for neuronal self-/nonself-recognition. Elife. 2022;11:e72416. doi: 10.7554/eLife.72416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schreiner D., Weiner J.A. Combinatorial homophilic interaction between γ-protocadherin multimers greatly expands the molecular diversity of cell adhesion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:14893–14898. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004526107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brasch J., Goodman K.M., Noble A.J., Rapp M., Mannepalli S., Bahna F., Dandey V.P., Bepler T., Berger B., Maniatis T., et al. Visualization of clustered protocadherin neuronal self-recognition complexes. Nature. 2019;569:280–283. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1089-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nicoludis J.M., Lau S.Y., Schärfe C.P.I., Marks D.S., Weihofen W.A., Gaudet R. Structure and sequence analyses of clustered protocadherins reveal antiparallel interactions that mediate homophilic specificity. Structure. 2015;23:2087–2098. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2015.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rubinstein R., Thu C.A., Goodman K.M., Wolcott H.N., Bahna F., Mannepalli S., Ahlsen G., Chevee M., Halim A., Clausen H., et al. Molecular logic of neuronal self-recognition through protocadherin domain interactions. Cell. 2015;163:629–642. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thu C.A., Chen W.V., Rubinstein R., Chevee M., Wolcott H.N., Felsovalyi K.O., Tapia J.C., Shapiro L., Honig B., Maniatis T. Single-cell identity generated by combinatorial homophilic interactions between α, β, and γ protocadherins. Cell. 2014;158:1045–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen W.V., Nwakeze C.L., Denny C.A., O’Keeffe S., Rieger M.A., Mountoufaris G., Kirner A., Dougherty J.D., Hen R., Wu Q., Maniatis T. Pcdhαc2 is required for axonal tiling and assembly of serotonergic circuitries in mice. Science. 2017;356:406–411. doi: 10.1126/science.aal3231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garrett A.M., Weiner J.A. Control of CNS synapse development by γ-protocadherin-mediated astrocyte-neuron contact. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:11723–11731. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2818-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garrett A.M., Schreiner D., Lobas M.A., Weiner J.A. γ-protocadherins control cortical dendrite arborization by regulating the activity of a FAK/PKC/MARCKS signaling pathway. Neuron. 2012;74:269–276. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hasegawa S., Hamada S., Kumode Y., Esumi S., Katori S., Fukuda E., Uchiyama Y., Hirabayashi T., Mombaerts P., Yagi T. The protocadherin-α family is involved in axonal coalescence of olfactory sensory neurons into glomeruli of the olfactory bulb in mouse. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2008;38:66–79. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2008.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hasegawa S., Kumagai M., Hagihara M., Nishimaru H., Hirano K., Kaneko R., Okayama A., Hirayama T., Sanbo M., Hirabayashi M., et al. Distinct and cooperative functions for the protocadherin-α, -β and -γ clusters in neuronal survival and axon targeting. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2016;9:155. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2016.00155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katori S., Noguchi-Katori Y., Okayama A., Kawamura Y., Luo W., Sakimura K., Hirabayashi T., Iwasato T., Yagi T. Protocadherin-αC2 is required for diffuse projections of serotonergic axons. Sci. Rep. 2017;7 doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-16120-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kostadinov D., Sanes J.R. Protocadherin-dependent dendritic self-avoidance regulates neural connectivity and circuit function. Elife. 2015;4 doi: 10.7554/eLife.08964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.LaMassa N., Sverdlov H., Mambetalieva A., Shapiro S., Bucaro M., Fernandez-Monreal M., Phillips G.R. Gamma-protocadherin localization at the synapse is associated with parameters of synaptic maturation. J. Comp. Neurol. 2021;529:2407–2417. doi: 10.1002/cne.25102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Molumby M.J., Keeler A.B., Weiner J.A. Homophilic protocadherin cell-cell interactions promote dendrite complexity. Cell Rep. 2016;15:1037–1050. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.03.093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Molumby M.J., Anderson R.M., Newbold D.J., Koblesky N.K., Garrett A.M., Schreiner D., Radley J.J., Weiner J.A. γ-Protocadherins interact with neuroligin-1 and negatively regulate dendritic spine morphogenesis. Cell Rep. 2017;18:2702–2714. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.02.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mountoufaris G., Chen W.V., Hirabayashi Y., O’Keeffe S., Chevee M., Nwakeze C.L., Polleux F., Maniatis T. Multicluster Pcdh diversity is required for mouse olfactory neural circuit assembly. Science. 2017;356:411–414. doi: 10.1126/science.aai8801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prasad T., Weiner J.A. Direct and indirect regulation of spinal cord Ia afferent terminal formation by the γ-protocadherins. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2011;4:54. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2011.00054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tarusawa E., Sanbo M., Okayama A., Miyashita T., Kitsukawa T., Hirayama T., Hirabayashi T., Hasegawa S., Kaneko R., Toyoda S., et al. Establishment of high reciprocal connectivity between clonal cortical neurons is regulated by the Dnmt3b DNA methyltransferase and clustered protocadherins. BMC Biol. 2016;14:103. doi: 10.1186/s12915-016-0326-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weiner J.A., Wang X., Tapia J.C., Sanes J.R. Gamma protocadherins are required for synaptic development in the spinal cord. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:8–14. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407931101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hasegawa S., Kobayashi H., Kumagai M., Nishimaru H., Tarusawa E., Kanda H., Sanbo M., Yoshimura Y., Hirabayashi M., Hirabayashi T., Yagi T. Clustered protocadherins are required for building functional neural circuits. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2017;10:114. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2017.00114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen W.V., Alvarez F.J., Lefebvre J.L., Friedman B., Nwakeze C., Geiman E., Smith C., Thu C.A., Tapia J.C., Tasic B., et al. Functional significance of isoform diversification in the protocadherin gamma gene cluster. Neuron. 2012;75:402–409. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.06.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mancia Leon W.R., Spatazza J., Rakela B., ChatterJee A., Pande V., Maniatis T., Hasenstaub A.R., Stryker M.P., Alvarez-Buylla A. Clustered gamma-protocadherins regulate cortical interneuron programmed cell death. Elife. 2020;9 doi: 10.7554/eLife.55374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garrett A.M., Bosch P.J., Steffen D.M., Fuller L.C., Marcucci C.G., Koch A.A., Bais P., Weiner J.A., Burgess R.W. CRISPR/Cas9 interrogation of the mouse Pcdhg gene cluster reveals a crucial isoform-specific role for Pcdhgc4. PLoS Genet. 2019;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gegonne A., Tai X., Zhang J., Wu G., Zhu J., Yoshimoto A., Hanson J., Cultraro C., Chen Q.-R., Guinter T., et al. The general transcription factor TAF7 is essential for embryonic development but not essential for the survival or differentiation of mature T cells. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012;32:1984–1997. doi: 10.1128/MCB.06305-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang X., Weiner J.A., Levi S., Craig A.M., Bradley A., Sanes J.R. Gamma protocadherins are required for survival of spinal interneurons. Neuron. 2002;36:843–854. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01090-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prasad T., Wang X., Gray P.A., Weiner J.A. A differential developmental pattern of spinal interneuron apoptosis during synaptogenesis: insights from genetic analyses of the protocadherin-γ gene cluster. Development. 2008;135:4153–4164. doi: 10.1242/dev.026807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ing-Esteves S., Kostadinov D., Marocha J., Sing A.D., Joseph K.S., Laboulaye M.A., Sanes J.R., Lefebvre J.L. Combinatorial effects of alpha- and gamma-protocadherins on neuronal survival and dendritic self-avoidance. J. Neurosci. 2018;38:2713–2729. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3035-17.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carriere C.H., Wang W.X., Sing A.D., Fekete A., Jones B.E., Yee Y., Ellegood J., Maganti H., Awofala L., Marocha J., et al. The γ-protocadherins regulate the survival of GABAergic interneurons during developmental cell death. J. Neurosci. 2020;40:8652–8668. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1636-20.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Agostinelli L.J., Geerling J.C., Scammell T.E. Basal forebrain subcortical projections. Brain Struct. Funct. 2019;224:1097–1117. doi: 10.1007/s00429-018-01820-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cádiz-Moretti B., Abellán-Álvaro M., Pardo-Bellver C., Martínez-García F., Lanuza E. Afferent and efferent connections of the cortex-amygdala transition zone in mice. Front. Neuroanat. 2016;10:125. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2016.00125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Namboodiri V.M.K., Rodriguez-Romaguera J., Stuber G.D. The habenula. Curr. Biol. 2016;26:R873–R877. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.08.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stamatakis A.M., Van Swieten M., Basiri M.L., Blair G.A., Kantak P., Stuber G.D. Lateral hypothalamic area glutamatergic neurons and their projections to the lateral habenula regulate feeding and reward. J. Neurosci. 2016;36:302–311. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1202-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang X., Chou X.L., Zhang L.I., Tao H.W. Zona incerta: an integrative node for global behavioral modulation. Trends Neurosci. 2020;43:82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2019.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Allen Institute for Brain Science Developing Mouse Brain Atlas. https://developingmouse.brain-map.org/

- 47.Jacobowitz D.M., Abbott L.C. CRC Press; 1997. Chemoarchitectonic Atlas of the Developing Mouse Brain. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ben-Ari Y. Developing networks play a similar melody. Trends Neurosci. 2001;24:353–360. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01813-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Czarnecki A., Le Corronc H., Rigato C., Le Bras B., Couraud F., Scain A.-L., Allain A.-E., Mouffle C., Bullier E., Mangin J.-M., et al. Acetylcholine controls GABA-glutamate-and glycine-dependent giant depolarizing potentials that govern spontaneous motoneuron activity at the onset of synaptogenesis in the mouse embryonic spinal cord. J. Neurosci. 2014;34:6389–6404. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2664-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Garaschuk O., Linn J., Eilers J., Konnerth A. Large-scale oscillatory calcium waves in the immature cortex. Nat. Neurosci. 2000;3:452–459. doi: 10.1038/74823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hanson M.G., Landmesser L.T. Characterization of the circuits that generate spontaneous episodes of activity in the early embryonic mouse spinal cord. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:587–600. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-02-00587.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Myers C.P., Lewcock J.W., Hanson M.G., Gosgnach S., Aimone J.B., Gage F.H., Lee K.-F., Landmesser L.T., Pfaff S.L. Cholinergic input is required during embryonic development to mediate proper assembly of spinal locomotor circuits. Neuron. 2005;46:37–49. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yvert B., Branchereau P., Meyrand P. Multiple spontaneous rhythmic activity patterns generated by the embryonic mouse spinal cord occur within a specific developmental time window. J. Neurophysiol. 2004;91:2101–2109. doi: 10.1152/jn.01095.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.RIKEN BioResource Research Center. https://web.brc.riken.jp/en/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

-

•

All data are available in the manuscript or supplemental information.

-

•

All codes are available in the supplemental information.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.