Abstract

Patient: Female, 65-year-old

Final Diagnosis: Masson tumor

Symptoms: Headache • nausea

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: —

Specialty: Neurosurgery • Oncology

Objective:

Rare disease

Background:

Masson’s tumor, also known as intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia (IPEH), is an unusual endothelial proliferation that leads to improper thrombus development due to faulty endothelial structure. Although IPEH is rare in the central nervous system, it can arise at any location in the brain. Headaches, seizures, and focal neurological symptoms ae the most common presenting symptoms. It is more common in females and it can occur at any age.

Case Report:

Herein, we present a 65-year-old female patient with a progressively enlarging right temporal lobe mass that was initially considered metastatic ovarian carcinoma. She underwent a right temporal craniotomy and the lesion was totally resected. Contrary to expectations, the pathology report was an IPEH.

Conclusions:

In this paper, we conducted a literature review of previously reported cerebral IPEH cases, with a focus on their clinical and radiological presentations, management, and especially their association with previous radiotherapy. The important point is that one-third of the cases had a history of radiation therapy to the head, and most of them had stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) on the location of the brain from which IPEH subsequently developed. The major question for which we are looking for an answer is its relationship with previous radiotherapies. We wanted to know how many of these cases were associated with radiotherapy in the same area, the time interval from radiotherapy to the onset of IPEH or symptoms, the dose of the previous radiotherapy, and, overall, if there is any cause-effect relationship between IPEH and radiotherapy.

Keywords: Brain Neoplasms, Cerebellar Neoplasms

Background

Intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia, commonly known as Masson’s tumor, is a reactive, slow-growing, nonneoplastic exuberant recanalization with papillary formations with hyaline or fibrous stalks, and anastomosing vascular channels. There is no necrosis, atypia, or increased mitotic figures, and it is frequently associated with organized thrombus in the presence of angiogenic factors, accounting for around 2% of all vascular tumors [1–4]. Pierre Mason first reported IPEH as a vegetant intravascular hemangioendothelioma in an ulcerous hemorrhoidal vein in a patient in 1923 [5]. IPEH, which was initially described by Weheb et al in 1986 [6], has been characterized as developing in a variety of places throughout the body, including in cutaneous and subcutaneous tissue; however, cerebral involvement is rare and manifests with mass effects or neurological impairments based on its anatomical location [7–10]. Although this entity is benign, IPEH is usually detected after surgical resections. There are no distinct radiological features that can differentiate it from other benign or malignant brain tumors or vascular malignancies like angiosarcoma [11,12]. It usually presents as a mass, isointense to hypointense in T1 and hyperintense in T2, with different degrees of enhancement after gadolinium injection. There may be significant peri-lesional edema and mass effect; therefore, despite its deceiving nature, intracranial IPEH can be fatal as a result of mass effect and brain herniation. Complete resection, if feasible, is the treatment of choice, but adjuvant treatment (eg, with anti-angiogenic agents) is needed if complete surgical resection is not possible [10,13–15].

Regardless of many case reports, its relationship with the previous radiotherapy has remained unclear. Therefore, we presented this case and conducted this review of the literature to determine if there is any strong epidemiological link between this disease entity and previous radiotherapies.

Case Report

A 65-year-old woman who was diagnosed with stage IV ovarian carcinoma in 2013 presented with progressive headaches that she had experienced before. Nine years previously, she had undergone chemotherapy and debulking surgery. Two years later, her brain MRI showed a left parietal brain solitary metastasis that required resection and stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) at the surgical site. Her follow-up MRI in 2016 showed 3 new lesions in the right temporal, right cerebellar peduncle, and right cerebellar hemisphere, for which she underwent whole-brain radiation and SRS (25 Gy). Her follow-up MRIs in 2019 showed stable size of all lesions, but some areas were compatible with radiation necrosis in the left frontal and bilateral parietal lobes. A further follow-up MRI in January 2021 showed that the right temporal lesion had a 17 mm x 18 mm focus of hemorrhage. The area of enhancement of the right temporal lobe had increased in size and measured 18×13×21 mm, with a possible pseudo-progression related to hemorrhage inside it. A follow-up brain MRI after 3 weeks showed absorption of bleeding and stable size of the lesion.

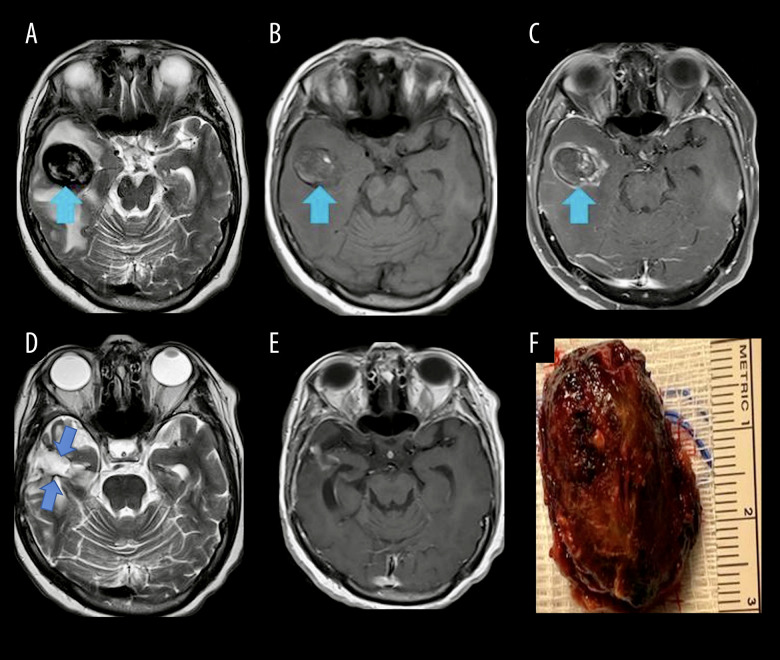

She presented with headache, nausea, and vomiting 6 months later. Her brain MRI showed a significant increase in the size of the right temporal lesion and peri-lesional edema, with a significant midline shift (Figure 1A–1C). The enhancing part of the lesion was a 38×3×21-mm mass (blue arrow), which was much larger than on the previous MRI (Figure 1A). The patient was taken to surgery based on a probable preoperative diagnosis of recurrent metastatic disease. A right temporal craniotomy was performed. The dura was incised and, using the navigation system, the tumor was localized at the depth of 1 cm and we were able to reach the lesion. It was hard and well-defined and we could easily define and separate it from the surrounding swollen brain. Intraoperatively, it looked like a metastatic tumor and the lesion was totally resected grossly (Figure 1D–1F). Interestingly, the pathology was reported as intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia (Figures 2A–2C, 3A, 3B).

Figure 1.

(A) Preoperative brain MRI, T2, showing mixed hyper- and hypointense mass (blue arrow) and surrounding brain edema. (B) Preoperative brain MRI, T1 without contrast, showing the hypointense mass (blue arrow). (C) Preoperative brain MRI, T1 after contrast injection, showing the heterogeneously enhancing mass (blue arrow). (D) Follow-up postoperative brain MRI 12 months after surgery, T2, showing the empty space of resected lesion (double blue arrow). (E) Follow-up postoperative brain MRI, 12 months after surgery, T1 after contrast injection, showing no residual mass. (F) Macroscopic photo of the lesion after gross total resection.

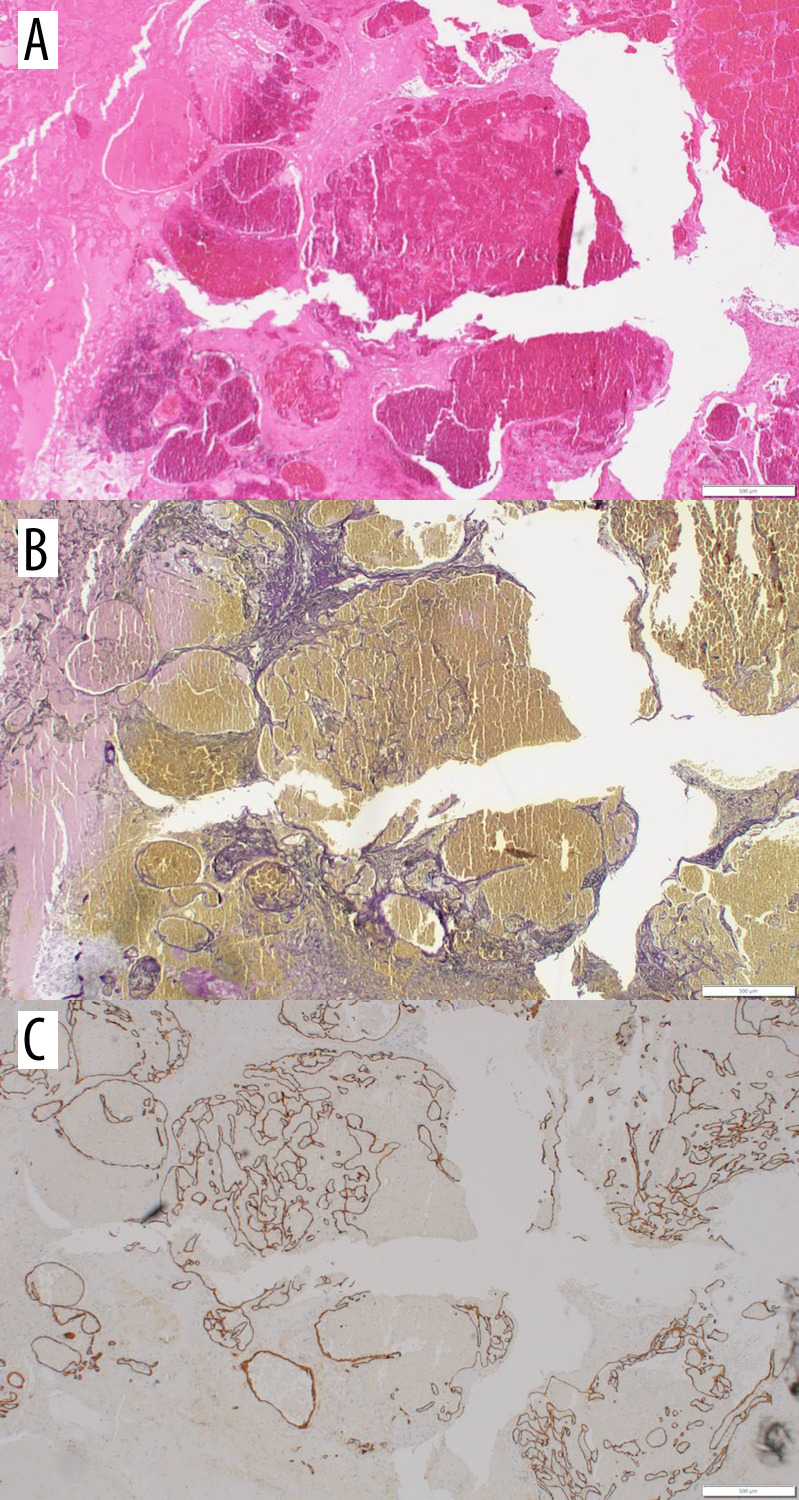

Figure 2.

(A) Routine hematoxylin and eosin stain showed mainly hemorrhage and reactive glial tissue. (B) Elastic histochemical stain. Elastic stain highlighted network of vascular channels. (C) CD34 immunohistochemical stain (endothelial marker). CD34 showed thin vascular channels lined by endothelium.

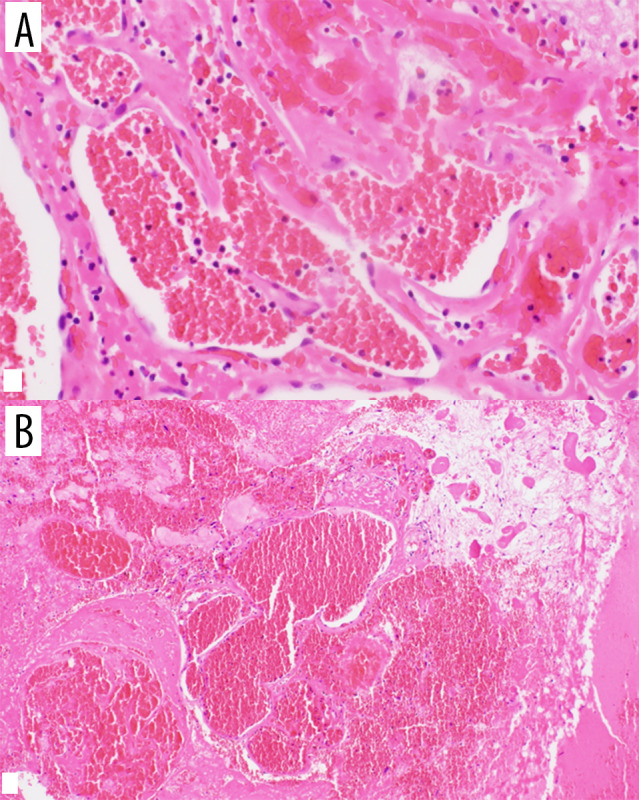

Figure 3.

(A) 40-power magnification and (B) 20-power magnification of H&E staining of our case.

Postoperatively, the patient recovered very well and, considering the benign nature and gross total resection of the lesion, no further treatment was recommended. She received follow-up MRIs at 3, 6, and 12 months, which did not show any evidence of recurrence, and she has remained clinically asymptomatic. Table 1 summarizes previously reported cases of IPEH, and 44 cases have been reported before our case.

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical, radiological, and result of treatment for 45 previously published cases of IPEH, including our current case.

| Author | Age, sex | Clinical sign | Brain site | Imaging findings | History of RT/dose (gray)/interval between RT and IPEH appearance (years) | Surgical resection | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lesley WS et al [28], 2000 | 46 y, F | Dysphagia, otalgia, head and neck pain | Right posterior inferior-PICA aneurysm (type 2) | MRI: enhanced T1 hypointense, T2 hyperintense mass MRA: faint vascular lesion |

No | Complete | No recurrence at 1 year |

|

| |||||||

| Stoffman MR et al [29], 2003 | 54 y, F | Dysarthria, dysphagia | Meckle’s cave (type 1) | MRI: extradural hemorrhagic lesion CT: unenhanced temporal mass with hyperdense blood |

No | Subtotal | Residual tumor at 10 mo |

|

| |||||||

| Du Plessis DG et al [30], 2003 | 6 y, F | Skull bump | Parietal, frontal lobes (extravascular) | MRI: subcortical enhancing lesion | No | Complete | No recurrence at 1 year |

|

| |||||||

| Lee W et al [31], 2004 | 46 y, M | Dizziness, hypoesthesia of upper limb | Giant V4 aneurysm (type 2) | MRI: T1 isointense, T2 hypointense mass MRA: no obvious flow signal within the lesion |

No | No surgery | Asymptomatic at 2 years |

|

| |||||||

| Cagli S et al [1], 2004 | 16 y, F | Diplopia, ptosis | Cavernous sinus (type 1) | MRI: enhanced T1 hyperintense lesion | No | Subtotal | Small residual mass at 3 years |

| 18 y, F | Diplopia | Cavernous sinus (type 1) Parietal lobe (type 2) | MRI: enhanced T1 isointense, T2 hyperintense lesion | No No No |

Subtotal Total Total |

Evidence of residual mass at 3 years | |

| 24 y, F | Headache, seizure | Cavernous sinus, | MRI: enhanced T1 isointense, T2 hyperintense lesion | No recurrence at 2 years | |||

| 28 y, F | Diplopia, ptosis | Meckle’s cave (type 1) | MRI: enhanced T1 isointense, T2 hyperintense lesion | No evidence of residual mass at 2 years | |||

|

| |||||||

| Zhang R et al [19], 2005 | 49 y, F | Facial paralysis, hearing loss | Petrous, jugular regions (type 1) | MRI: T1 and T2 hyperintense mass CT: hypodense lesion |

No | Subtotal | No follow-up available |

|

| |||||||

| Ohshima T et al [32], 2005 | 41 y, F | Diplopia | Middle cranial fossa (type 1) | No | Subtotal | No recurrence at 2 years | |

|

| |||||||

| Crocker M et al [14], 2007 | 43 y, F | Headache | Parietal lobe (type 1) | MRI: enhanced T1 mass MRA: AVM in vermis |

Yes/SRS 22.5 Gy, 20 Gy/4 | Total | Resection 7 years after radiation therapy, no recurrence at 1 year |

|

| |||||||

| Witt P et al [33], 2008 | 23 y, M | Generalized tonic-clonic seizure | Frontal lobe (extravascular) | MRI: Non-enhanced T1 and T2 hypointense lesion MRA: no evidence of vascular abnormality or neoplasm CT: hemorrhagic lesion |

No | Total | No follow-up available |

|

| |||||||

| Mann P et al [34], 2008–2016 | 4 y, F | Parietal lobe (extravascular) | MRI: Subdural lesion with extra-axial fluid | Yes/WBRT 54.7 Gy, 1-year-interval | |||

| 70 y, F | Temporal lobe | MRI: enhanced T1 mass with significant edema | Yes/WBRT 61.6 Gy/15 | ||||

| 44 y, M 44 y, M |

Cerebellum Cerebral (extravascular) |

MRI: Large enhancing T1 lesion | No Yes/SRS 38.0 Gy/10 |

||||

| 31 y, F | Frontal lobe (type 2) | MRI: nodular mass and multifocal calcifications secondary to previous radiation therapy | Yes/External beam/17 | ||||

| 63 y, M | Occipital lobe (extravascular) | MRI: lesion containing blood products | Yes/WBRT 30 Gy, SRS/3 Yes/External beam (for prior ependymoma & glioblastoma)/12 |

||||

| 33 y, M | Cerebellum (type 2) | MRI: Large enhancing T1 lesion | |||||

| 57 y, M | Language disturbance, tunnel vision, headache | Parietal lobe (extravascular) | CT: normal | No | |||

|

| |||||||

| Shih C-S et al [7], 2012 | 2 d, M | Proptosis | Cerebellum, suprasellar, orbit (type 2) | MRI: enhanced T1 isointense, T2 hyperintense mass | No | Subtotal | Sudden death after 15 mo |

|

| |||||||

| Karam- chandani J et al [4], 2012 | 44 y, M | Headache, disorientation | Temporal lobe (extravascular) | MRI & MRA: posteroinferior AVM CT: hemorrhagic lesion |

Yes/SRS 25 Gy in a min dose of 22.8 Gy and max dose of 49.8 Gy/4 | Total Total Total Partial |

Resection was performed 4 years after radiation therapy, no recurrence after 30 mo |

| 57 y, M | Vomiting, weakness, headache | Cerebellar (extravascular) | MRI: hemorrhagic mass | Yes/SRS dose unknown/4 | Resection was performed 3 years after radiation therapy, no recurrence after 20 mo | ||

| 67 y, M | Temporal lobe (extravascular) | MRI: enhancing mass of the cavernous sinus | Yes/SRS 20 Gy/4 Yes/SRS |

No recurrence 15 mo after resection | |||

| 73 y, M | Cavernous sinus (extravascular/ intratumoral) | MRI: heterogeneous enhancing mass | 25 Gy/2-month-interval | No follow-up available | |||

|

| |||||||

| Park KK et al [35], 2012 | 10 y, F | Frontal lobe | MRI: enhanced T1 hypointense, T2 hyperintense mass | No | Complete | No recurrence at 8 mo | |

|

| |||||||

| Taiwo F et al [36], 2013 | 72 y, M | Dizziness, lethargy | Frontal lobe (extravascular) | MRI: hemorrhagic lesion CT: enhancing hyperdense mass |

No | Subtotal | No residual mass At 2 weeks |

|

| |||||||

| Miller TR et al [37], 2013 | 39 y, F | Syncope | Petrous apex (type 1) | MRI: enhanced T1 hypointense, T2 hyperintense mass | No | Total | Unremarkable course at 3 mo |

| 56 y, F | Sinus infection | Clivus (type 1) | MRI: enhanced T2 hyperintense mass | No | Biopsy | Asymptomatic at 2 years | |

| 73 y, M | Seizure, aphasia | Frontal lobe (type 2) | MRI: enhancing mass CT: hyperdense mass |

Yes/SRS following AVM | Total | No evidence of residual mass at 6 mo | |

|

| |||||||

| Ginat DT et al [38], 2014 | 72 y, F | Cerebellar dysfunction | Cerebellar (extravascular) | MRI: enhancing lesion CT: hyperattenuating mass |

Yes/External beam 5400 cGy/1 | Total | No follow-up available |

|

| |||||||

| Shah HC et al [39], 2014 | 3 mo, M | Swollen scalp | Parietal lobe (type 1) | MRI: T1 isointense, T2 hyperintense mass | No | Total | No recurrence at 1 year |

|

| |||||||

| Sim SY et al [16], 2015 | 11 y, M | Sight-impaired | Parasellar (type 1) | MRI: enhanced T1 isointense, T2 hyperintense mass CT: hyperdense mass |

Yes/Chemo RT 50’4 Gy/ (RT as an adjuvant therapy) | Total | No recurrence at 13 years |

|

| |||||||

| Salaud C et al [40], 2017 | 56 y, F | Dizziness, aphasia, headache | Temporal lobe (type 1) | MRI: enhanced T1 hypointense, T2 hyperintense mass CT: hypodense mass |

No | Complete | No recurrence at 5 years |

|

| |||||||

| Charalambous LT et al [41], 2017 | 22 y, M | Headache, inattention | Pineal gland (type 1) | MRI: enhanced hyperdense mass | No | Total | No recurrence after 2nd surgery at 3 years |

|

| |||||||

| Bagga V et al [42], 2017 | 24 y, M | Headache, confusion | Frontal lobe (type 1) | MRI and CT: small enhancing lesion | No | Subtotal | No follow-up available |

|

| |||||||

| Barritt AW et al [43], 2017 | 59 y, F | Epilepsy, hallucination | Temporal lobe | MRI: midline shift | Yes/Gamma knife radiosurgery 25 Gy/15 | Subtotal | No recurrence at 18 mo |

|

| |||||||

| Prat GP et al [3], 2018 | 51 y, F | Hydrocephalus, diplopia | Cavernous sinus (type 1) | MRI: enhancing mass | Yes/RT 54 Gy/ (RT as an Adjuvant therapy) | Subtotal | Residual mass at 3 mo |

|

| |||||||

| Sankey EW et al [44], 2019 | 32 y, F | Aphasia | Parietal, frontal lobes | MRI: enhanced lesion within hemorrhage | No | Total | No follow-up available |

|

| |||||||

| Mezmezian MB et al [45], 2020 | 59 y, F | Headache, vertigo | Petrous apex, clivus | MRI: enhanced T1 hypointense, T2 hyperintense mass CT: lytic lesion |

No | Partial | No recurrence at 30 mo |

|

| |||||||

| Retzlaff AA et al [46], 2020 | 28 y, F | Visual aura, headache, hydrocephalus | Pineal region | MRI: non-enhanced T1 hypointense, T2 hyperintense mass | No | Total | No residual lesion at 9 mo |

|

| |||||||

| Gajaria PK et al [47], 2021 | 45 y, M | Headache, low sharp sight | Cavernous sinus | MRI: enhanced T1 hyperintense mass | No | Complete | Symptom free at 8 mo |

|

| |||||||

| Manoranjan B et al [48], 2021 | 79 y, F | Dizziness, incontinence | Ventricle | No | |||

|

| |||||||

| Goyal-Honavar A et al [49], 2022 | 31 y, F | Headache, ophthalmoplegia | Cavernoussinus | MRI: enhanced T2 hyperintense mass with a component in the sella | Yes/SRS 13 Gy, 2.8 Gy/5 | Partial | Recurrence at 8 mo |

|

| |||||||

| Present case | 65 y, F | Headache, nausea, vomiting | Right temporal lobe | MRI; T1 Hypo and T2 Hyperintense large mass with gadolinium enhancement and significant brain edema and mass effect | Yes/SRS 25 GY/5 |

Complete | 12 mo follow-up, no recurrence |

AVM – arteriovenous malformation; Chemo – chemotherapy; CT – computed tomography; d – days old; F – female; M – male; mo – months old; mo – months; MRA – magnetic resonance angiography; MRI – magnetic resonance imaging; PICA – posterior inferior cerebellar artery; RT – radiotherapy; SRS – stereotactic radiosurgery; T1 – T1-weighted; T2 – T2-weighted; y – years old.

Discussion

Intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia (IPEH), also called Masson’s tumor, is a rare benign vascular lesion that consists of a hyperplastic monolayer of endothelial cells covering a bundle of hyalinized papillary vegetation [1,8,15,16]. IPEH is quite uncommon intracranially [1,8,9,17–19]; however, extracranial IPEH has recently been discovered in a variety of locations, including the limbs, mostly the feet and hands, the orbits, lips, and salivary glands. It can also be identified in vital organs such as the heart, lung, liver, and kidney, posing a life-threatening hazard to the patient.

IPEH seems to be more common in women than in men (57% female versus 43% male in the current literature review) and it is not limited to any age group (Table 1). According to reports, the number of men with IPEH is increasing. As a result, the findings support the idea that IPEH is gender-neutral. IPEH has been shown to be congenital in some studies. Shih et al [7] described a 2-day-old boy who had IPEH. On the other hand, no established inheritance pattern exists. The pathogenesis of IPEH is not fully understood. It can be primary or a complication of previous external beam radiotherapy or stereotactic radiosurgery (eg, using a gamma knife for treatment of arteriovenous malformation) [14]. In the current review of literature, 31% of patients with IPEH had a history of previous external beam radiotherapy or stereotactic radiosurgery. The average time interval between radiotherapy and onset of IPEH was 7.5 years (range, 2 months to 15 years) in these published cases. In 2 cases, radiotherapy was used as adjuvant therapy after resection of the lesion. In our presented case, radiosurgery was performed about 5 years before the presentation. There have been many reports on the long-term effect of radiotherapy on the CNS. Atherosclerotic changes, radiation necrosis, and development of vascular abnormalities, including cavernoma or aneurysms, are among the reported complications.

Moreover, intracranial IPEH can occur in combination with pre-existing vascular malformations, aneurysms, phlebectasia, lymphangiomas, thrombi, and angiokeratomas, without any history of radiotherapy [17,20]. Anti-angiogenic factors like angiostatin, thrombospondins (TSP), and endostatin, as well as hormonal variables, should be considered in the pathogenesis of IPEH [21]. Overall, according to reports, there are 3 types of IPEH [22]:

A pure (primary) form that takes up residence in a normal blood vessel (usually a vein);

A mixed (secondary) form that occurs in the presence of a prior cerebral varix, such as an AVM or hemangioma, which can result in intraventricular or intracerebral hemorrhage; and

A rare extravascular form, which arises in an organized hematoma.

In the current case, the patient had a history of ovarian cancer and had a small enhancing lesion in her right temporal lobe in 2016 and underwent radiosurgery (up to 25 Gy) and whole-brain radiation therapy for multiple other lesions. She developed a small right temporal hemorrhage in January 2021 and a subsequent progressively enlarging mass in June 2021, which was finally resected, and pathology showed IPEH, not ovarian cancer. Therefore, in our case, IPEH developed in an organized clot, but the process may have been initiated by previous radiotherapy or focused radiosurgery by forming a cavernous malformation. Cavernomas are characterized by frequent micro-bleeding and subsequent micro-clot formation, and her IPEH developed inside this clot.

IPEH can develop in the base of the skull, the skull’s intravascular space, or the brain parenchyma. Depending on the location of the mass, they can present with increased intracranial pressure, compression of surrounding neurovascular structures, intracranial hemorrhage, and cranial nerve palsy [1,7,16,23]. In some cases, such as the presented case, it can manifest with a large mass, edema, and midline shift, which, if not treated in time, can lead to brain herniation and death.

Histologically, an IPEH is a solid pinky or red mass with vascularization [8]. IPEHs have no necrosis, atypia, increased mitotic figures, or any other obvious invasive behavior, which is one of their histopathological hallmarks [3]. Diaz-Flores et al [24] proposed that intussusceptive angiogenesis (IA) plays a key role in the histogenesis of IPEH. In another comparable investigation, they discovered that the creation of myriad pillars, especially in veins, is the cornerstone of IPEH. Akdur et al [25] examined IPEH histomorphological and immunohistochemical factors such as CD31, CD34, CD105, ki-67 staining, FVIII, and type IV collagen, in which CD31 and CD34 were found to be the most sensitive variables.

The differential diagnosis includes angiosarcoma, which is characterized by numerous irregularly shaped anastomosing vascular channels lined by atypical endothelial cells with a highly infiltrative architecture and poor demarcation. Compared to Masson tumors, angiosarcoma is typically covered by multilayers of plump endothelial cells with pleomorphism and mitotic activities [1–4,7–19,26].

Radiographically, it is difficult to differentiate an IPEH from a malignancy. There is no definite image characteristic for IPEH, which can appear as isointense to hypointense on T1, and hyperintense on T2, with varying degrees of contrast enhancement. It can cause severe peri-lesional edema and swelling of the brain, even with a significant mass effect. Overall, in most cases, it appears to be a malignant tumor on imaging, but it is not. Masson’s tumor can even be mistaken for a metastatic tumor clinically and radiographically, as it was in our case. However, it lacks critical malignant characteristics such as infiltration, necrosis, and nuclear pleomorphism on pathologic examinations. Therefore, clinical and radiological criteria are not sufficient for making a diagnosis, and pathological examination is necessary for a definite diagnosis.

IPEH can be treated with complete surgical removal; however, this may not be possible in all intracranial lesions, especially deeply seated lesions. The major challenge in the resection of these lesions is their location when in eloquent areas, avoiding damage to the surrounding swollen brain, and not causing more neurological deficits. Intraoperative neuronavigation and neuromonitoring will help to localize the lesion and minimize complications. Regardless of resection of the lesion, peri-lesional edema can persist or even worsen after the surgery. Therefore, dexamethasone should be continued postoperatively for a couple of days and tapered off slowly to treat brain edema. Perioperative seizure should be also prevented by antiseizure medications.

Small and deeply seated lesions in the highly eloquent areas of the brain and brain stem should not be treated surgically, as the morbidity and mortality may be worse that that caused by the lesion itself. Hence, gamma knife radiosurgery, chemotherapy, and stereotactic radiation have all been advised in circumstances where the risks of surgery and total resection as a primary treatment for the lesion outweigh the advantages [10,27]. Embolization before surgery has also been recommended in some cases to reduce bleeding during the procedure [8,19], although in our case the lesion was very well-circumscribed and bleeding was minimal. In cases of subtotal resection, anti-angiogenesis agents may be considered and patients should be closely monitored and followed by MRI [26].

Despite its benign histological characteristics, IPEH has a high non-neoplastic proliferation rate and a well-documented proclivity for recurrence after subtotal or even total resection [3]. Therefore, we should monitor these patients with an interval follow-up MRI and check for recurrence after removing the mass. In our case, we performed 3-, 6-, and 12-month follow-up MRIs; we found no evidence of recurrence, and the patient remained clinically well. Based on these findings, more prospective and multicenter studies are required to prove the relationship between radiation therapy and IPEH development.

Conclusions

IPEH is a non-cancerous vascular lesion that is difficult to diagnose before surgery. Despite its rarity, the possibility of Masson’s tumor should be considered in patients who have had a spontaneous hemorrhage without a history of any abnormalities such as cancer, and it also should be considered in the differential diagnosis of cerebral lesions with radiographic characteristics resembling vascular lesions. It has been associated with prior radiotherapy, which can be either radiosurgery or only external beam radiation. When feasible, IPEH can be cured by total surgical excision with the minimal risk of recurrence and this is the criterion standard treatment. Nevertheless, the probability of local progression with incomplete removal necessitates adjuvant therapy such as radiation, anti-angiogenesis agents, chemotherapy, and finally, regular follow-up imaging.

Footnotes

Declaration of Figures’ Authenticity

All figures submitted have been created by the authors who confirm that the images are original with no duplication and have not been previously published in whole or in part.

References:

- 1.Cagli S, Oktar N, Dalbasti T, et al. Intravascular papillary endothelial hyper-plasia of the central nervous system – four case reports. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2004;44(6):302–10. doi: 10.2176/nmc.44.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Enzinger F, Enzinger WS. Weiss’s soft tissue tumors. Shock. 2008;30(6):754. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prat GP, Jimenez MS, Caro PC, et al. Case report and review of the literature. World Neurosurgery. 2018;114:194–203. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karamchandani J, Vogel H, Fischbein N, et al. Extravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia mimicking neoplasm after radiosurgery: Case report. Neurosurgery. 2012;70(4):E1043–48. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e31822e81f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Masson P. Hemangioendotheliome vegetant intravasculaire. Bull Soc Anat (Paris) 1923;93:517. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wehbé MA, Otto NR. Intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia in the hand. J Hand Surg. 1986;11(2):275–79. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(86)80070-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shih C-S, Burgett R, Bonnin J, Boaz J, Ho CY. Intracranial Masson tumor: Case report and literature review. J Neurooncol. 2012;108(1):211–17. doi: 10.1007/s11060-012-0799-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Avellino AM, Grant GA, Harris AB, et al. Recurrent intracranial Masson’s vegetant intravascular hemangioendothelioma: Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 1999;91(2):308–12. doi: 10.3171/jns.1999.91.2.0308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baylor JE, Antonelli PJ, Rojiani A, Mancuso AA. Facial palsy from Masson’s vegetant intravascular hemangioendothelioma. Ear Nose Throat J. 1998;77(5):408–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kristof RA, Van Roost D, Wolf HK, Schramm J. Intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia of the sellar region: Report of three cases and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 1997;86(3):558–63. doi: 10.3171/jns.1997.86.3.0558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hashimoto H, Daimaru Y, Enjoji M. Intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia. A clinicopathologic study of 91 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 1983;5(6):539–46. doi: 10.1097/00000372-198312000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salyer WR, Salyer DC. Intravascular angiomatosis: Development and distinction from angiosarcoma. Cancer. 1975;36(3):995–1001. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197509)36:3<995::aid-cncr2820360323>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee W, Hui F, Sitoh Y. Intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia in an intracranial thrombosed aneurysm: 3T magnetic resonance imaging and angiographical features. Singapore Med J. 2004;45:330–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crocker M, Desouza R, Epaliyanage P, et al. Masson’s tumour in the right parietal lobe after stereotactic radiosurgery for cerebellar AVM: Case report and review. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2007;109(9):811–15. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duong D, Scoones D, Bates D, Sengupta R. Multiple intracerebral intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1997;139(9):883–86. doi: 10.1007/BF01411407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sim SY, Lim YC, Won KS, Cho KG. Thirteen-year follow-up of parasellar intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia successfully treated by surgical excision: case report. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2015;15(4):384–91. doi: 10.3171/2014.9.PEDS13518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lesley WS, Kupsky WJ, Guthikonda M. Intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia arising within a posteroinferior cerebellar artery aneurysm: Case report and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 2000;47(4):961–66. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200010000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stoffman MR, Kim JH. Masson’s vegetant hemangioendothelioma: Case report and literature review. J Neurooncol. 2003;61(1):17–22. doi: 10.1023/a:1021248504923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang R, Zhou L-F, Mao Y, Wang Y. Papillary endothelial hyperplasia (Masson tumor) of the petrous and jugulare region: Case report and literature review. Surg Neurol. 2005;64(1):55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2004.08.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Requena L, Sangueza OP. Cutaneous vascular proliferations. Part II. Hyperplasias and benign neoplasms. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37(6):887–922. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)70065-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsoitis G, Milios G, Mandinaos C, et al. [Vegetant intravascular hemangioendothelioma of the skin (cutaneous intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia)] Ann Dermatol Venerol. 1991;118(11):866–68. [in French. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Znati K, Daoudi A, Chbani L, et al. [Intravascular papillary endothelial hyper-plasia of the ankle: a case report] Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2009;54(6):600–2. doi: 10.1016/j.anplas.2009.02.005. [in French] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hagiwara A, Inoue Y, Shakudo M, et al. Intracranial papillary endothelial hyperplasia: Occurrence of a case after surgery and radiosurgery. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1999;23(5):781–85. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199909000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Díaz-Flores L, Gutiérrez R, González-Gómez M, et al. Myriad pillars formed by intussusceptive angiogenesis as the basis of intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia (IPEH). IPEH is intussusceptive angiogenesis made a lesion. Histol Histopathol. 2021;36(2):217–28. doi: 10.14670/HH-18-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akdur NC, Donmez M, Gozel S, et al. Intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia: Histomorphological and immunohistochemical features. Diagn Pathol. 2013;8(1):167. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-8-167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lakka SS, Rao JS. Antiangiogenic therapy in brain tumors. Expert Rev Neurother. 2008;8(10):1457–73. doi: 10.1586/14737175.8.10.1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller TR, Mohan S, Tondon R, et al. Intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia of the skull base and intracranial compartment. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2013;115(10):2264–67. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2013.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lesley WS, Kupsky WJ, Guthikonda M. Intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia arising within a posteroinferior cerebellar artery aneurysm: Case report and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 2000;47(4):961–65. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200010000-00033. ; discussion 966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stoffman MR, Kim JH. Masson’s vegetant hemangioendothelioma: Case report and literature review. J Neurooncol. 2003;61(1):17–22. doi: 10.1023/a:1021248504923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.du Plessis DG, Balamurali G, Smith ET, et al. Papillary endothelial hyperplasia associated with cortical dysplasia. Acta Neuropathol. 2003;105(3):303–8. doi: 10.1007/s00401-002-0643-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee W, Hui F, Sitoh YY. Intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia in an intracranial thrombosed aneurysm: 3T magnetic resonance imaging and angiographical features. Singapore Med J. 2004;45(7):330–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ohshima T, Ogura K, Nakayashiki N, Tachibana E. Intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia at the superior orbital fissure: Report of a case successfully treated with gamma knife radiosurgery. Surg Neurol. 2005;64(3):266–69. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2004.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Witt P, Gault J, Kleinschmidt‐DeMasters BK. 23‐year‐old hispanic male with new onset seizures. Brain Pathology. 2008;18(4):594. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2008.00208.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mann P, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK. CNS Masson tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40(1):81–93. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park KK, Won YS, Yang JY, et al. Intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia (Masson tumor) of the skull: Case report and literature review. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2012;52(1):52. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2012.52.1.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taiwo F, Cowley P, Shieff C, et al. A case of florid intracerebral reaction to haematoma mimicking a tumour. Br J Neurosurg. 2013;27(1):100–1. doi: 10.3109/02688697.2012.701675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller TR, Mohan S, Tondon R, et al. Intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia of the skull base and intracranial compartment. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2013;115(10):2264–67. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2013.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ginat DT, Walcott BP, Mordes D, et al. Intracranial organizing hematoma with papillary endothelial hyperplasia features after resection and involved field radiotherapy for cerebellar juvenile pilocytic astrocytoma. Clin Imaging. 2014;38(3):322–25. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shah HC, Mittal DH, Shah JK. Intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia (Masson’s tumor) of the scalp with intracranial extension. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2014;9(3):260–62. doi: 10.4103/1817-1745.147584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Salaud C, Loussouarn D, Buffenoir K, Riem T. Masson’s tumor revealed by an intracerebral hematoma. Case report and a review of the literature. Neurochirurgie. 2017;63(4):327–29. doi: 10.1016/j.neuchi.2016.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Charalambous LT, Penumaka A, Komisarow JM, et al. Masson’s tumor of the pineal region: Case report. J Neurosurg. 2017;128(6):1725–30. doi: 10.3171/2017.2.JNS162350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bagga V, Kailaya-Vasan A, Wharton SB, Patel U. Intracerebral Masson’s tumor – slow-filling vascular lesion demonstrated by indocyanine green video angiography. World Neurosurg. 2017;101:812. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.03.075. e15–e19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barritt AW, Merve A, Epaliyanage P, Aram J. Intracranial papillary endothelial hyperplasia (Masson’s tumour) following gamma knife radiosurgery for temporal lobe epilepsy. Pract Neurol. 2017;17(3):214–17. doi: 10.1136/practneurol-2016-001573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sankey EW, Hynes JS, Komisarow JM, et al. Masson’s tumor presenting as a left frontal intraparenchymal hemorrhage resulting in severe expressive aphasia during pregnancy: Case report. J Neurosurg. 2019;134(1):189–96. doi: 10.3171/2019.8.JNS191767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mezmezian MB, Arakaki N, Fallaza Moya S, et al. Petroclival intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia with psammoma body‐like structures. Neuropathology. 2020;40(3):268–74. doi: 10.1111/neup.12629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Retzlaff AA, Arispe K, Cochran EJ, Zwagerman NT. Intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia of the pineal region: A case report and review of the literature. World Neurosurg. 2020;133:308–13. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gajaria PK, Shenoy AS, Baste BD, Goel NA. Intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia of the cavernous sinus – a rare occurrence. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2021;64(3):541–44. doi: 10.4103/IJPM.IJPM_499_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Manoranjan B, Mann JA, Joseph JT, Kelly JJ. Intraventricular Masson tumor: Case report and systematic review of primary intracranial intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia. J Neurosurg Sci. 2022;66(5):420–24. doi: 10.23736/S0390-5616.21.05372-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goyal-Honavar A, Balakrishnan R, Chacko G, Chacko AG. Radiation-induced intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia in a cavernous sinus hemangioma. Neurol India. 2022;70(1):359–62. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.338715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]