Abstract

Escherichia coli strain RDEC-1 causes a diarrheagenic infection in rabbits with AF/R1 fimbriae, which have been identified as an important colonization factor in RDEC-1 adherence leading to disease. The AF/R1-mediated RDEC-1 adherence model has been used as a model systems for E. coli diarrheal diseases. In this study, RDEC-1 adhered specifically to small intestinal brush borders, with both sialic acid and β-galactosyl residues apparently involved. The AF/R1-mediated adherence activity of [14C]-labeled RDEC-1 was analyzed quantitatively by using 24-well plates coated with purified brush borders and purified microvilli. Two microvillus membrane proteins (130 and 140 kDa) were individually isolated, and chicken antibody raised to each protein inhibited bacterial adherence. These same two proteins, previously shown to be recognized by AF/R1, were individually digested with trypsin, and the amino acid sequences of peptides were determined by reversed-phase capillary liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS). This LC-MS analysis indicated that these proteins are subunits of the rabbit sucrase-isomaltase protein (SI) complex. Guinea pig serum raised to purified rabbit SI complex inhibited bacterial adherence to microvilli. Additionally, as determined by high-performance thin-layer chromatography and autoradiography, RDEC-1 adhered selectively, via AF/R1 fimbriae, to a glycolipid tentatively identified as galactosylceramide (Galβ1-1Cer) in the lipid extract of rabbit small intestinal brush borders. RDEC-1 adherence to Galβ1-1Cer was partially inhibited in the presence of galactose. These combined results indicate that the endogenous receptor molecule for AF/R1 fimbriae of RDEC-1 is each individual component of the SI complex, although binding to glycolipid may be responsible for an additional adherence mechanism.

Adherence of pathogenic bacteria to receptors on the surface of epithelial cells has been recognized as an important early event in colonization of bacteria (18). In many cases, the adhesion of Escherichia coli and other gram-negative bacteria takes place through the binding of bacterial fimbriae to specific receptors on the host cell surface, via adhesin-receptor interactions (1, 2, 7, 11, 13, 24). The specificity, the affinity, and the concentrations of the interacting molecules and the presence of nutritional and inhibitory components will determine the degree of success of the bacterial colonization. Most bacterial receptor molecules have been reported to be glycoproteins and glycolipids (11, 26, 39, 40).

The first stage in pathogenesis of both enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC) and enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) infections is the fimbria-mediated adherence of the bacteria to intestinal brush borders, which then allows the production of disease through later stages involving additional virulence determinants (11, 15, 19). With EPEC, intestinal microvilli are effaced and the host cell cytoskeleton is dramatically rearranged to form pedestals on which the bacteria are intimately associated (15, 19). Although there is evidence that fimbria-mediated attachment of ETEC can cause a degree of intestinal cell dysfunction (37), secretory diarrhea is induced through the production of enterotoxins (11). The EPEC strain RDEC-1 causes diarrhea in rabbits without invading the intestinal epithelium, similar to ETEC infection in humans (2, 8, 9). RDEC-1 expresses AF/R1 (for adherence factor/rabbit 1) fimbriae, which have been identified as being important in RDEC-1 adherence to intestinal brush borders and subsequent diarrhea (2, 10). A previous study identified a rabbit ileal microvillus membrane sialoglycoprotein complex with subunits of 130 and 140 kDa as a receptor(s) for AF/R1 fimbriae (35). However, detailed biochemical information as well as the identity of this host receptor for the AF/R1 fimbrial adhesin has been lacking.

In this study, we identified endogeneous AF/R1 fimbrial glycoprotein and glycolipid receptor molecules in rabbit small intestine by qualitative and quantitative adherence of RDEC-1 to rabbit brush borders and microvilli. The AF/R1-mediated binding to brush borders was diminished by pretreatment of brush borders with glycolytic enzymes, indicating the importance of galactose and sialic acid moieties present on both N- and O-linked oligosaccharides. We also determined amino acid sequences from tryptic peptides of the 130- and 140-kDa subunits of the ileal microvillus membrane by reversed-phase liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analysis, which provided the identity tandem mass spectrometry of the proteins as sucrase and isomaltase, respectively. The blocking effect of antibody raised specifically to each of the two subunits was examined. In addition, the ability of guinea pig sera raised to purified rabbit sucrase-isomaltase (SI) to block AF/R1-mediated RDEC-1 microvillus adherence was tested.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Media and reagents.

Bacteriological medium components were purchased from Difco (Detroit, Mich.), and all other reagents were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, Mo.). Glycolipid and phospholipid standards were purchased from Sigma, Matreya (Pleasant Gap, Pa.), and Accurate Chemicals (Westbury, N.Y.). All thin-layer chromatography solvents were purchased from T. J. Baker (Phillipsburg, N.J.). Guinea pig anti-rabbit SI serum was generously provided by C. Pothoulakis, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, Mass.

Culture and labeling of bacteria.

Rabbit EPEC strains RDEC-1 (serotype O15:H−) and M34 (an isogenic strain of RDEC-1 lacking AF/R1 fimbriae [42]) were grown in Penassay broth (also known as antibiotic medium 3) for the visual, semiquantitative binding assay or in Penassay broth containing 100 μCi of [14C]acetic acid (Amersham, Arlington Heights, Ill.) overnight at 37°C in a shaking incubator for the quantitative adherence assays.

Preparation of rabbit intestinal brush borders.

Adult male New Zealand White rabbits weighing between 3 and 4 kg were euthenized by a lethal intravenous injection of pentabarbital (65 mg/kg). Rabbit intestinal brush borders were isolated from the duodenum, jejunum, ileum, proximal and distal colon, and cecum as described by Cheney et al. (12) with modifications. Rabbit intestinal segments were removed, and each was subdivided into 50-cm lengths, washed twice with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (0.145 M NaCl, 0.01 M Na2HPO4-NaH2PO4, pH 7.5), and flushed once with ice-cold EDTA containing 3 mM NaH2PO4, 9 mM Na2HPO4 · 7H2O, 20 mM EDTA, 1 mg of soybean trypsin inhibitor per liter, and 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (pH 7.5) (EDTA buffer). Each portion of the segment was cut into 10-cm lengths and then opened longitudinally. Intestinal epithelial cells were scraped with glass microscope slides, and the scrapings were placed into EDTA buffer. Brush borders were purified after homogenization, passage through a 20-mesh nylon screen, and differential centrifugation. Purified brush borders were suspended in a storage buffer (0.145 M NaCl, 0.01 M Na2HPO4-NaH2PO4, 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 μg of soybean trypsin inhibitor per ml, 1.25 μg of antipain per ml, 1.25 μg of pepstatin per ml, pH 7.2). The brush border preparation was stored in an ice bath if used within 48 h or stored at −70°C after addition of glycerol to a final concentration of 40%.

Preparation of microvilli.

Microvilli from rabbit small intestinal brush borders were purified as described by Bretscher and Weber (6) with slight modifications. Packed rabbit brush borders (0.5 to 1 ml) were suspended in 10 ml of PBS containing 75 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 10 mM imidazole Cl, and 0.4 mM dithiothreitol (pH. 7.2). Microvilli were isolated by rapidly passing the brush border suspension through a 21-gauge needle 15 times followed by differential centrifugation. Purified microvilli were suspended in the storage buffer and stored at −70°C.

Bacterial adherence assays. (i) Visual assay.

The assay was conducted as described by Cheney et al. (12) with slight modifications. Briefly, 50 μl of rabbit brush border suspension (1 mg of protein/ml), 20 μl of bacterial suspension (109 cells/ml), and 30 μl of PBS were mixed in a glass test tube (12 by 75 mm) and incubated for 15 min at room temperature on a rotating platform. After mixing vigorously for 10 s on setting 5 with a Vortex-Genie (Scientific Industries, Bohemia, N.Y.), the bacterium-rabbit brush border mixture was washed twice with PBS (5 ml per wash) by centrifugation at 1,100 × g for 10 min. The pellet was gently resuspended in PBS, and bacterial adherence to rabbit brush borders was examined at 1,000 power in oil immersion utilizing Nomarski differential interface contrast optics (Olympus USAH2).

(ii) Twenty-four-well plate binding assay.

The assay was conducted as described by Rafiee et al. (35) with slight modification. Serially diluted rabbit small intestinal brush borders or microvilli were applied to 24-well polystyrene plates (Costar, Cambridge, Mass.) by incubating 0.3 ml/well overnight at 4°C. The wells were washed with PBS and then blocked with 0.4 ml of 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Sigma, fatty acid free) in PBS (blocking solution) for 6 h at 4°C. The blocking solution was removed, and 0.3 ml of [14C]acetic acid-labeled bacteria (2 × 105 cpm/ml; approximately 5 × 107 cells/ml) in storage buffer containing 1% BSA and 50 mM methyl α-d-mannopyranoside was added to each well. After incubation overnight at 4°C, each well was washed five times with PBS (0.5 ml per wash), and adherent bacteria were solubilized in 0.4 ml of 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) for 3 h at 37°C. Radioactivity was measured in a Beckman Rackbeta 1217 liquid scintillation counter.

Adherence to electrotransfers.

RDEC-1 direct binding to glycoproteins was tested by overlay of bacteria to electrotransfers from brush borders subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), transferred to nitrocellulose, and overlaid with bacteria. Bacteria were detected after labeling with [14C]acetate (as described above), with biotin (36), or with AF/R1 antibody (41).

SDS-PAGE.

Microvillus proteins were separated on 6% Tris-glycine SDS-polyacrylamide gels (Novex, San Diego, Calif.). and stained with Coomassie blue R-250. Gel bands containing 130- and 140-kDa proteins were excised and used to immunize chickens as well as for protein analysis by LC-MS analysis.

Preparation of chicken antibody.

Excised SDS-PAGE gel bands containing 130-and 140-kDa proteins were individually minced and emulsified with Freund's adjuvants. For the primary immunization, each chicken received intramuscularly and subcutaneously approximately 200 μg of antigen mixed with complete Freund's adjuvant, followed by booster immunizations at 3- week intervals with approximately 100 μg of antigen mixed with incomplete Freund's adjuvant. Eggs were collected after the third boost, and the Eggstract IgY Purification System (Promega, Madison, Wis.) was used to purify egg yolk antibody according to the manufacturer's specifications. After collection of eggs was initiated, chickens were boosted once, and the terminal bleed was collected 10 days after the third booster immunization.

Antibody inhibition assay.

To determine the inhibitory effect of anti-130- and anti-140-kDa-protein chicken antibodies on AF/R1 fimbria-mediated adherence of RDEC-1, microvilli (10 μg of protein/well) were immobilized overnight at 4°C on 24-well plates, and the plates were blocked for 1 h at room temperature with 1% BSA in PBS. The blocking solution was removed, and 0.3 ml of serially diluted antisera or purified egg antibody (the starting protein concentration of 0.5 mg/ml) was added to each well, followed by incubation for 1 h at room temperature. After the excess antibody was removed, each well was washed three times with PBS and blocked with 0.4 ml of the blocking solution for 6 h at 4°C. After the blocking solution was removed, 0.3 ml of [14C]acetic acid-labeled bacteria was added to each well as described for the 24-well plate binding assay.

Guinea pig serum raised to purified rabbit ileal brush border SI (generously provided by Dr. C. Pothoulakis, Boston University) was used in identical antibody inhibition assays. The antigen used for immunization was purified as a dimer by CHAPS {3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate} extraction, lectin affinity chromatography, specific elution with 0.2 M galactose-containing buffer, binding to an affinity column of Clostridium difficile toxin A, elution with buffer containing 0.5 M NaCl, and final purification by gel filtration, before being injected into guinea pigs (34).

Purification and biotin labeling of AF/R1.

AF/R1 fimbriae were prepared from static Penassay broth and harvested by centrifugation, shearing of fimbriae from bacteria with an Omnimixer homogenizer (Omni International, Warrenton, Va.), and ammonium sulfate precipitation of AF/R1 as described by McQueen et al. (31). Biotinylated AF/R1 adhesin was prepared by reacting purified AF/R1 with biotinyl-3-aminocaproic acid N-hydroxysuccinimide ester (Sigma) as previously described (21).

Enzymatic treatment of brush borders.

To remove terminal sialic acid and galactosyl residues the brush border preparations (200 μg of protein) were solubilized in 50 mM sodium acetate (pH 4.6) containing 0.1% taurodeoxycholate. Solubilized brush borders were then treated separately or sequentially with Vibrio cholerae neuraminiase (20 mU; Sigma) or E. coli β-galactosidase (2 U, Sigma) for 48 h at 37°C with end-over-end mixing. To remove the N-glycans, brush border preparations (100 μg of protein) were solubilized in 20 mM sodium phosphate–50 mM EDTA–1% SDS–1% β-mercaptoethanol (pH 7.5), denaturated at 100°C for 5 min, and allow to cool on ice for 2 min. NP-40 (1%) was then added, followed by N-glycosidase F (10 mU) from recombinant Flavobacterium meningosepticum (Glyko, Inc., Novata, Calif.), and the mixture was incubated for 48h at 37°C with end-over-end mixing. To remove the O-glycans, brush border preparations (100 μg of protein) were dried completely and resuspended in 50 mM sodium posphate (pH 5.0). The brush borders were then treated first with V. cholerae neuraminiase (20 mU; Sigma) for 48 h at 37°C and then with recombinant Streptococcus pneumoniae endo-α-N-acetylgalactosaminidase. (2 mU; Glyko, Inc.) for 48 h at 37°C (with end-over-end mixing). After treatment, all exo- and endoglycosidase activities were stopped by heating the sample at 100°C for 5 min. These samples were then tested for their ability to be bound by biotinylated AF/R1 using the 96-well plate binding assay described below.

Biotinylated AF/R1 binding assay.

Protein from each reaction mixture was diluted into 50 mM carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.6) to obtain a protein concentration ranging between 0.012 and 25 μg of protein per well (100-μl final volume) and then immobilized on 96-well Immulon IV polystyrene plates (Dynatech, Alexandria, Va.) overnight at 37°C. The wells were rinsed three times with 0.1 ml of 0.05% PBS-Tween 20 (PBS-Tween). Biotinylated AF/R1 (10 μg/ml diluted in PBS-Tween) was added and incubated at room temperature for 4 h. Unbound AF/R1 was removed by washing three times with 0.1 ml of PBS-Tween. Bound AF/R1 activity was detected by addition of 0.1 ml of horseradish peroxidase conjugated to strepavidin (1 μg/ml diluted in PBS-Tween) (Pierce) and incubation at room temperature for 1 h. The wells were rinsed three times with 0.1 ml of PBS-Tween, and the bound horseradish peroxidase-strepavidin activity was detected by using the chromogenic peroxidase substrate 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) as described by Harlow and Lane (21).

Amino acid sequence analysis. (i) Sample preparation.

For LC-MS, gel bands containing 130 k- and 140-kDa proteins were divided into a number of smaller pieces, washed, and destained in 500 μl of 50% methanol overnight. The gel pieces were dehydrated in acetonitrile, rehydrated in 10 mM dithiothreitol in 0.1 M ammonium bicarbonate, and reduced at room temperature for 1 h. The dithiothreitol solution was removed, and the sample was alkylated in 50 mM iodoacetamide in 0.1 M ammonium bicarbonate at room temperature for 1 h. The reagent was removed, and the gel pieces were washed in 0.1 M ammonium bicarbonate and dehydrated in acetonitrile. The acetonitrile was removed, and the previous step was repeated. After drying by centrifugal evaporation, the gel pieces were rehydrated in 20 ng of trypsin (Promega) per μl in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate on ice for 10 min. Any excess trypsin solution was removed, and 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate was added. The sample was digested overnight at 37°C, and the peptides were extracted from the polyacrylamide in two aliquots of 50% actonitrile–5% formic acid. These extracts were combined and evaporated for LC-MS analysis.

(ii) LC-MS.

The LC-MS system consisted of a Finnigan LCQ ion trap mass spectrometer system with an electrospray ion source interfaced to a self-packed POROS 10 RC reversed-phase capillary column (30). One-microliter volumes of the extract were injected, and the peptides were eluted from the column by an acetonitrile–0.1 M acetic acid gradient. The electrospray ion source is operated at 4.5 kV with a coaxial sheath liquid flow of 70% methanol–30% water–0.125% acetic acid and a coaxial nitrogen flow adjusted as needed for optimum sensitivity. The digest was analyzed using the double-play capacity of the instrument, acquiring full-scan mass spectra to determine peptide molecular weights and product ion spectra to determine amino acid sequences in sequential scans. This mode of analysis produces approximately 150 to 200 collisionally activated dissociation (CAD) spectra of ions ranging in abundance over several orders of magnitude. The data were analyzed by selecting the 10 to 15 most abundant ions in a base peak presentation of the full-scan data. The CAD spectra of these ions were interpreted to produce the tabulated results for each digest. LC-MS analysis took place at the W.M. Keck Biomedical Mass Spectrometry Laboratory, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, under the direction of Jay Fox (30).

Extraction of rabbit intestinal brush border lipids.

One volume of the packed rabbit intestinal brush borders was suspended in 3 volumes of water, and the suspension was sonicated for 5 min in an ultrasonic bath (Branson Ultrasonic, Danbury, Conn.). Lipids were extracted with chloroform-methanol-brush border suspension (10:5:3, vol/vol/vol) overnight at room temperature on a rocking platform, followed by centrifugation at 4°C for 5 min at 800 × g. The supernatant was dried under vacuum or under nitrogen, and the extracted lipids were resuspended in chloroform-methanol (2:1, vol/vol).

High-performance thin-layer chromatography (HPTLC) overlay analysis.

The analysis was conducted on aluminum-backed silica gel 60 plates (Merck) with a solvent system of chloroform–methanol–0.25% KCl in water (5:4:1) as described elsewhere (25) with slight modifications. Briefly, samples were separated on the plates and stained with an orcinol reagent (water containing 0.1% orcinol monohydrate and 3% sulfuric acid). For the overlay with radiolabeled bacteria, the plate was soaked in 0.1% poly(iso-butyl) methacrylate (Polysciences, Warington, Pa.) in hexane, blocked with Tris–1% BSA, and overlaid with 14C-labeled bacteria (4 × 105 cpm/ml). After being washed five times with PBS, the plate was dipped in 2,5-diphenyloxazole, dried, and autoradiographed at −70°C (29).

RESULTS

Adhesion of RDEC-1 to rabbit brush borders.

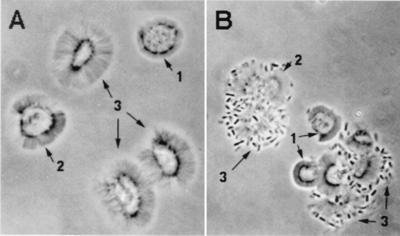

RDEC-1 bound equally to the brush borders from duodenum, jejunum, and ileum but not to brush borders from cecum, proximal colon, and distal colon (Table 1). M34 (an isogenic variant of RDEC-1 lacking AF/R1 fimbriae) did not bind to any brush border preparations. In general, more bacteria adhered to the small intestinal brush borders with long microvilli than to those with medium or short microvilli (Fig. 1). While many individual brush borders in the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum had the maximal amount of adherent bacteria, additional brush borders were seen to have fewer or no bacteria attached, as had been previously reported (12). Within the three segments of the small intestine, no differences in morphology of brush borders or in bacterial adherence properties were found. Thereafter, intestinal scrapings from the entire small intestine were used in brush border preparations.

TABLE 1.

Visually determined adherence of E. coli RDEC-1 (AF/R1+) and M34 (AF/R1−) to brush borders of different rabbit intestinal segments

| Source of brush borders | Adherencea of:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| RDEC-1 | M34 | |

| Duodenum | 4 | 0 |

| Jejunum | 4 | 0 |

| Ileum | 4 | 0 |

| Proximal colon | 0 | 0 |

| Distal colon | 0 | 0 |

| Cecum | 0 | 0 |

Score of bacterial adherence: 4, >16 bacteria per brush border; 3, 11 to 15 bacteria per brush border; 2, 6 to 10 bacteria per brush border; 1, 2 to 5 bacteria per brush border; 0, 0 to 1 bacterium per brush border.

FIG. 1.

E. coli RDEC-1 adherence to rabbit small intestinal brush borders without bacteria, (A) or with E. coli RDEC-1, scored as 4 (see Table 1) (B). 1, Brush borders with short microvilli; 2, brush borders with medium-length microvilli; 3, brush borders with long microvilli. Viewing was at 1,000 power in oil immersion with Nomarski optics.

Quantitation of E. coli adherence to brush borders and microvilli.

Quantitative adherence of E. coli to rabbit small intestinal brush borders and microvilli was examined by a 24-well plate binding assay. The degree of RDEC-1 adherence to the brush borders or microvilli was dependent on the amount of protein applied (Table 2). The level of bacterial adherence to microvilli was 2.4-fold (or more) greater than that to brush borders (Table 2). When examined with an inverted microscope, each washing step was seen to remove attached brush borders from the well (not shown). This shearing effect was not evident when plates were coated with microvilli. After long-term (3 years) storage at −70°C, microvilli retained receptor activity, but repeated freezing and thawing resulted in loss of activity. Direct binding assays by overlay of labeled bacteria for the detection for specific adherence to any particular region of nitrocellulose transfers were not successful. High background due to nonspecific binding was the result, irrespective of the blocking agent or bacterial labeling technique.

TABLE 2.

Quantitative adherence of 14C-labeled E. coli RDEC-1 (AF/R1+) and M34 (AF/R1−) to rabbit small intestinal brush borders and microvilli

| Coating material | Protein (μg)/well | cpm (mean ± SE)a

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| RDEC-1 | M34 | ||

| None (background) | 0 | 127 ± 28 | 330 ± 69 |

| Brush borders | 1 | 427 ± 99 | 257 ± 54 |

| 3 | 873 ± 72 | 333 ± 36 | |

| 10 | 1,893 ± 31 | 235 ± 54 | |

| Microvilli | 1 | 1,014 ± 295 | 255 ± 89 |

| 3 | 2,188 ± 333 | 151 ± 41 | |

| 10 | 5,047 ± 471 | 113 ± 31 | |

n = 3 individual experiments.

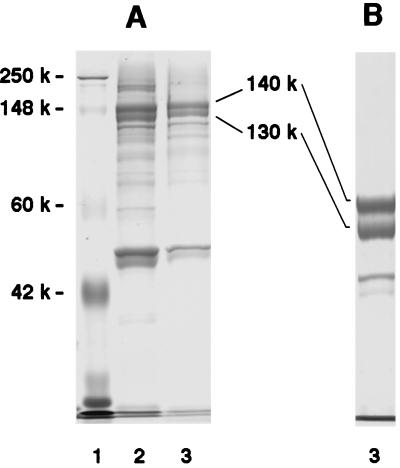

Isolation of 130- and 140-kDa glycoproteins and inhibition of binding by antibody.

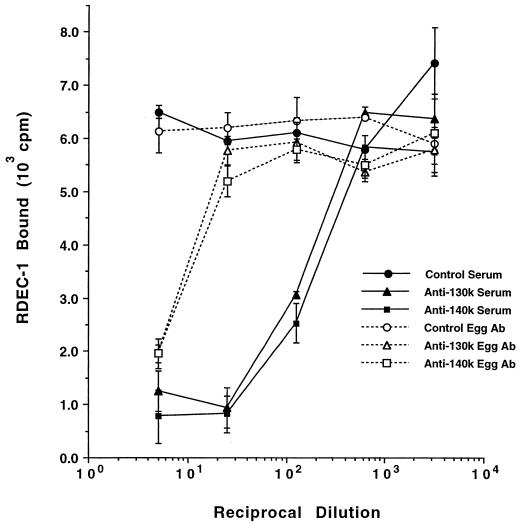

Rafiee et al. (35) previously identified two sialoglycoproteins of 130 and 140 kDa that were recognized by AF/R1 fimbriae. These bands were separated on 6% SDS-PAGE gels and excised for antiserum production and for protein sequencing (see below), with each preparation shown not to be cross-contaminated with the other (see below and Tables 3 and 4). To determine whether chicken antibodies raised to the 130- and 140-kDa microvillus membrane proteins (Fig. 2) interfere with the AF/R1 fimbria-mediated RDEC-1 adherence to microvilli, microvillius-coated 24-well plates (10 μg/well) were preincubated with the serially diluted antibody. Both anti-130- and anti-140-kDa-protein chicken sera inhibited the RDEC-1 adherence to the microvilli, while the preimmune sera did not (Fig. 3). Anti-130- and anti-140-kDa protein purified egg antibody also blocked the RDEC-1 adherence to the microvilli, while purified egg antibody from nonimmune chicken eggs did not.

TABLE 3.

Peptide sequences from the 140-kDa microvillus protein

| Peptide no. | Measured molecular mass (M + H+, Da) | Peptide sequence determined by CADa | Positionb | Peptide sequence from database - (calculated molecular mass [M + H+], Da) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 709.8 | XGXHXR | 786–791 | IGLHLR (708.5) |

| 2 | 737.0 | SFXXTR | 582–587 | SFILTR (736.4) |

| 3 | 815.0 | HYXNXR | 686–691 | HYLNIR (815.4) |

| 4 | 1,165.0 | FRHDXXYWK | 248–255 | FRHDLKYWK (1,164.6) |

| 5 | 1,238.1 | WNYNSXDVVK | 359–368 | WNYNSLDVVK (1,237.6) |

| 6 | 1,487.0 | YVXXXDPAXSXNR | 421–433 | YVIILDPAISINR (1,486.8) |

| 7 | 1,504.0 | TXC∗MoDSVQYWGK | 542–553 | TLC∗MoDSVQYWGK (1,503.6) |

| 8 | 1,510.1 | VQWDDQTFXESEK | 928–939 | VQWDDQTFLESEK (1,509.7) |

| 9 | 1,624.7 | XTC∗YPDADXATQEK | 940–953 | ITC∗YPDADIATQEK (1,624.7) |

| 10 | 1,810.6 | XPSEYMoYGFGEHVHK | 232–246 | LPSEYMoYGFGEHVHK (1,809.8) |

| 11 | 1,873.3 | GGYXXPXQQPAVTTTASR | 792–809 | GGYIIPIQQPAVTTTASR (1,873.0) |

| 12 | 1,986.2 | XNC∗XPEQSPTQAXC∗AQR | 74–90 | INC∗IPEQSPTQAIC∗AQR (1,986.0) |

| 13 | 2,154.4 | VAYNTGXPDFVQDXHDHGQK | 402–420 | VAYNTGLPDFVQDLHDHGQK (2,153.0) |

| 14 | 2,208.1 | GC∗NDNTXNYPPYXPDXVDK | 518–536 | GC∗NDNTLNYPPYIPDIVDK (2,208.0) |

| 15 | 2,515.8 | XXFDSSXGPXVYSDQYXQXSTR | 210–231 | ILFDSSIGPLVYSDQYLQISTR (2,515.3) |

| 16 | 2,608.0 | STPTXFGNDXNNVXXTTESQTANR | 133–156 | STPTLFGNDINNVLLTTESQTANR (2,606.3) |

X, I or L (which cannot be distinguished by low-energy CAD); Mo, oxidized M; C∗, carbamidomethyl-modified C.

Amino acids in the sequence of isomaltase (peptides 1 to 16).

TABLE 4.

Peptide sequences from the 130-kDa protein

| Peptide no. | Measured molecular mass (M + H+, Da) | Peptide sequence determined by CADa | Positionb | Peptide sequence from database (calculated molecular mass [M + H+], Da) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 724.6 | TTFXSR | 692–697 | TTFLSR (724.4) |

| 2 | 728.6 | NVXNXR | 574–579 | NVLNIR (728.4) |

| 3 | 845.8 | TDGXHFR | 421–427 | TDGLHFR (845.4) |

| 4 | 879.7 | XYDVEXK | 55–61 | LYDVEIK (879.5) |

| 5 | 977.9 | TTXTSTXXK | 743–751 | TTLTSTLLK (977.6) |

| 6 | 1,003.6 | EXPQFVDR | 270–277 | ELPQFVDR (1,003.5) |

| 7 | 1,029.5 | NHNXQFTR | 550–557 | NHNIQFTR (1,029.5) |

| 8 | 1,335.2 | GGHXXPC∗QEPAR | 680–691 | GGHILPC∗QEPAR (1,334.7) |

| 9 | 1,354.0 | XTXPSEPXTNXR | 1–12 | ITLPSEPITNLR (1,353.8) |

| 10 | 1,397.7 | QXDFTXDENFR | 259–269 | QLDFTIDENFR (1,397.7) |

| 11 | 1,449.7 | EXXDFYNNYMK | 370–380 | EILDFYNNYMK (1,449.7) |

| 12 | 1,465.7 | EXXDFYNNYMoK | 370–380 | EILDFYNNYMoK (1,465.7) |

| 13 | 1,589.4 | DXNWHTWGMoFTR | 118–129 | DLNWHTWGMoFTR (1,579.7) |

| 14 | 1,609.3 | WFDYHTGEDXGXR | 649–661 | WFDYHTGEDIGIR (1,608.7) |

| 15 | 1,826.1 | NTEXNYPPYFPEXTK | 405–419 | NTELNYPPYFPELTK (1,825.9) |

| 16 | 2,060.4 | XPSEYXYGFGEAEHTAFK | 99–116 | LPSEYIYGFGEAEHTAFK (2,059.0) |

| 17 | 2,226.7 | YEVPVPXXPATPTSTQENR | 35–54 | YEVPVPLIPATPTSTQENR (2,227.1) |

| 18 | 1,351.8 | XNNXDTGFGSGTR | 917–929 | LNNLDTGFGSGTR (1,351.7) |

| 19 | 1,526.2 | TTVYCNAXAXGGER | 788–801 | TTVYCNAIALGGER (1,524.7) |

| 20 | 1,628.8 | AQXXHDAFNXASAQK | 653–667 | AQIIHDAFNLASAQK (1,626.9) |

| 21 | 1,720.2 | ESAXXFDPXVSSISNK | 355–370 | ESALLFDPLVSSISNK (1,719.9) |

XdI or L (which cannot be distinguished by low-energy CAD); Mo, oxidized M; C∗, carbamidomethyl-modified C.

Amino acids in the sequences of sucrase (peptides 1 to 17) and aminopeptidase N (18 to 21).

FIG. 2.

SDS-PAGE analysis of rabbit small intestinal brush borders and microvilli. (A) 10% Tris-glycine gel. (B) 6% Tris-glycine gel. Lanes: 1, molecular weight standards; 2, brush borders; 3, microvilli.

FIG. 3.

Inhibition of [14C]-labeled E. coli RDEC-1 adherence to rabbit small intestinal brush border microvilli by chicken serum and purified egg antibodies to the two major microvillus membrane proteins (130 and 140 kDa). Error bars indicate standard errors.

Preliminary carbohydrate characterization of the AF/R1 receptor.

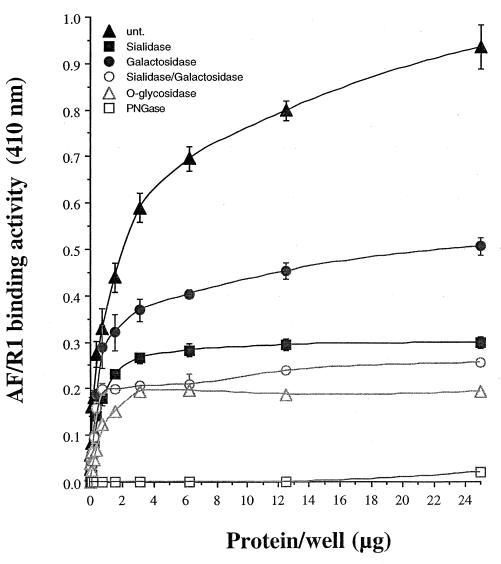

The 96-well plate binding assay was used to determine the effects of removing carbohydrate moieties from glycoproteins in the brush border preparations susceptible to being recognized by AF/R1 (Fig. 4). The untreated preparation demonstrated that the binding activity of biotinylated AF/R1 is dependent on the amount of protein applied and that the binding is saturable. When N- and O-glycans were removed, the binding activity was reduced to 8.2 and 30.9% of that of the untreated control, respectively. In addition, to identitify monosaccharides present on the reducing terminus of the glycans implicated in the recognition by AF/R1, specific exoglycosidases were used to remove terminal sialic acid (NeuAc) and β-galactosyl (Galβ) residues. Treatment of the intestinal brush border preparations with sialidase or β-galactosidase reduced the binding to 42.7 and 60.4%, respectively. Sequential treatment of brush border preparations with sialidase followed by β-galactosidase significantly decreased the AF/R1 binding activity to 36.5% of that of the untreated control. These results indicate that the receptors present in the intestinal brush border preparations contain both NeuAc and Galβ residues implicated in the recognition. There appears be a greater number of NeuAc than Galβ residues present on AF/R1 receptor molecules. After sequential sialidase and β-galactosidase treatment, it appears that some of the carbohydrate sequence NeuAc-Galβ is present on the putative receptor. In order to promote the accessibility of the Galβ(1-3)GalNAc sequence commonly found in the O-glycans to the endo-α-N-acetylgalactosaminidase, we first removed the sialic acid residues present on this carbohydrate sequence. The binding was decreased to 30.9% of that of the untreated control corresponding to the treatment by the neuraminidase alone (42.7%).

FIG. 4.

Effect of enzymatic treatment of rabbit intestinal brush borders on binding by biotinylated AF/R1. Intestinal brush border glycoproteins were subjected to treatment with N-glycosidase F from F. meningosepticum (PNGase), endo-α-N-acetylgalactosaminidase from S. pneumoniae (O-glycosidase), neuraminidase from V. cholerae (sialidase), β-galactosidase from E. coli (galactosidase), neuraminidase and β-galactosidase sequentially (sialidase/galactosidase) or remained untreated (unt.), as described in Materials and Methods. The results shown are the means ± standard errors (n = 2) for untreated and enzymatically treated intestinal brush border preparations.

Amino acid sequence analysis of the protein receptors.

The molecular masses and amino acid sequence of peptides from the tryptic digest of the 140-kDa band (Fig. 2) are shown in Table 3. Database searches using Sequest identified the peptides derived from the 140-kDa band in the sequence of rabbit isomaltase, a subunit of rabbit SI National Center for Biotechnology nonredundant (NCBInr) 03.21.98 accession number 135040; calculated molecular mass, 210.1 kDa). All of the peptides detected originated in the amino-terminal-most 1,000 amino acid residues of SI. The molecular masses and amino acid sequences of peptides from the tryptic digest of the 130-kDa band (Fig. 2) are shown in Table 4. Database searches using Sequest identified peptides 1 to 17 from the sequence of sucrase, the other subunit of rabbit SI (Table 4). All of the peptides in this digest originated in the carboxy-terminal-most 1,000 amino acids. The SI complex is expressed almost exclusively on the luminal side of small intestinal villus enterocytes and after synthesis is cleaved into two subunits, isomaltase (approximately 140 kDa, 1,006 amino acids) and sucrase (approximately 120 kDa, 820 amino acids) (23, 34). Therefore, the 130- and 140-kDa proteins represent the complementary pieces of rabbit SI. Database searches using Sequest identified peptides 18 to 21 in Table 4, also present in the 130-kDa band, as derived from rabbit aminopeptidase N (NCBInr accession number 1352929, calculated molecular mass, 108.8 kDa; 961 amino acids [17, 43]). However, there were fewer peptides identified 4 versus 16 and 17 for aminopeptidase, isomaltase, and sucrase, respectively), and the abundance of the peptides derived from this protein was significantly less than that of those from the rabbit SI (data not shown). The proteins in each respective band were fully resolved, as no cross-contamination (peptides from one protein found in the other band) was observed.

Blocking effect of guinea pig anti-rabbit SI antibody.

The effect of guinea pig anti-rabbit SI serum on the AF/R1 fimbria-mediated RDEC-1 adherence to microvilli was tested using the 24-well plate assay. The AF/R1 fimbria-mediated RDEC-1 adherence to microvilli was inhibited at up to a 1:625 dilution of the guinea pig anti-rabbit SI antibody (Table 5). Preimmune guinea pig serum at a 1:25 dilution did not inhibit the adherence.

TABLE 5.

Inhibition of 14C-labeled E. coli RDEC-1 (AF/R1) adherence to rabbit small intestinal brush border microvilli by guinea pig anti-rabbit SI

| Serum | Dilution | RDEC-1 bound (cpm, mean ± SE [n = 3]) |

|---|---|---|

| Guinea pig anti-rabbit SI | 1:25 | 2,419 ± 105 |

| 1:125 | 4,140 ± 7 | |

| 1:625 | 7,474 ± 138 | |

| 1:3,125 | 11,228 ± 357 | |

| Preimmune guinea pig serum | 1:25 | 11,417 ± 605 |

| Negative control | 493 ± 1 |

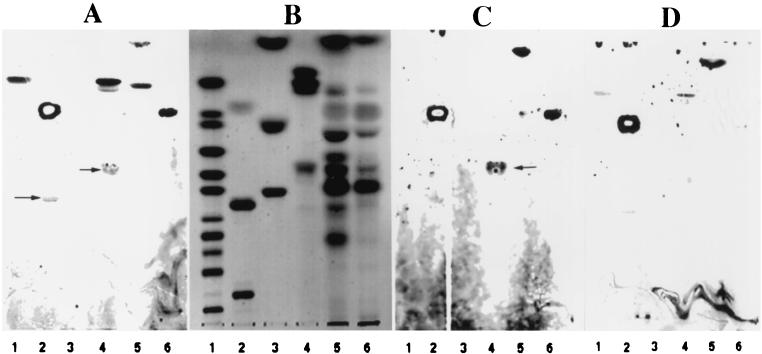

Analysis of AF/R1 glycolipid receptors.

In order to examine the carbohydrate binding specificity of AF/R1 as well as to identify any AF/R1 fimbrial glycolipid receptors of rabbit small intestinal brush borders, lipid fractions were purified from brush borders by extraction with chloroform-methanol-water (5:4:1). Rabbit brush border lipid extracts and a variety of commercially available glycolipids and phospholipids were separated by HPTLC and detected by orcinol staining (Fig. 5B). Bacterial overlay and autoradiography were carried out to identify lipids with AF/R1 fimbrial receptor activities (Fig. 5A, C, and D). Both RDEC-1 and M34 bound to several commercially available standard lipids separated on HPTLC plates, including asialo-GM1 (Fig. 5, lanes 2), phosphatidylethanolamine (Fig. 5, lanes 2), and phosphatidylserine (Fig. 5, lanes 4). Neither bacterium bound to other commercially available lipids tested in this experiments, including cholesterol (Fig. 5, lanes 3), lactosylceramide (Fig. 5, lanes 1), trihexosylceramide (Fig. 5, lanes 1), globoside (Fig. 5, lanes 1), Forssman glycolipid (Fig. 5, lanes 1), gangliosides GM1 and GM2 (Fig. 5, lanes 1), ganglioside GM3 (Fig. 5, lanes 2), GD1a, GD1b, GD2, and GT1b, sulfatide (Fig. 5, lanes 2), and GD3 and GQ1b (data not shown). RDEC-1, but not M34, bound to the commercially available type I galactosylceramide (Galβ1-1Cer) (Fig. 5, lanes 1 and 4), which contains hydroxylated fatty acids, but not to type II galactosylceramide (Fig. 5, lanes 4), which contain nonhydroxylated fatty acids (33). RDEC-1 bound to the band in the small intestinal brush border lipid extract (Fig. 5, lanes 5) which has a mobility identical to that of the commercially available type I galactosylceramide (Fig. 5, lanes 1 and 4). When RDEC-1 was overlaid in the presence of 0.5 M galactose, RDEC-1 adherence to the commercially available type I galactosylceramide and the band in the small intestinal lipid extract was inhibited, while the adherence to asialo-GM1, phosphatidylethanolamine, and phosphatidylserine was not.

FIG. 5.

HPTLC overlay analysis of E. coli RDEC-1 (AF/R1+) and M34 (AF/R1−) adherence to separated lipids. Quadruplicate chromatograms were stained with orcinol (B) or overlaid with 14C-labeled RDEC-1 (A and D) or M43 (C) Panel D is identical to panel A except that the incubation solution contained 0.5 M galactose. Lanes 1 (standard glycolipids), from top to bottom, type I GalCer, CDH (two bands), CTH, globoside, Forssman glycolipid, GM2, GM1, GD3, GD1a, and GT1b. Lanes 2 (standard lipids), from top to bottom, phosphatidylethanolamine, asialo-GM1, and GD2. Lanes 3 (standard lipids), from top to bottom, cholesterol, sulfatide, and GM3. Lanes 4 (standard lipids), from top to bottom, type II GalCer, type I GalCer, and phosphatidylserine. Lanes 5, lipid extract from rabbit small intestinal brush borders. Lanes 6, lipid extract from rabbit large intestinal brush borders. Arrows indicate locations of asialo-GM1 (lane 2) and phosphatidylserine (lane 4).

DISCUSSION

Endogenous AF/R1 fimbrial receptors present in rabbit small intestine were evaluated using semiquantitative and quantitative assays of adherence of RDEC-1 to the rabbit intestinal brush borders and microvilli. As examined by the visual adherence assay, RDEC-1 adhered to the rabbit ileal brush borders, while M34 lacking AF/R1 fimbriae did not. This indicated that RDEC-1 adherence to rabbit ileal brush borders is mediated by AF/R1 fimbriae, confirming previous findings of Cheney et al. (12). RDEC-1 adhered equally to the brush borders from duodenum, jejunum, and ileum, demonstrating that the entire small intestine contains receptors for AF/R1 fimbriae, but not cecum, proximal colon, or distal colon.

Chicken serum and purified egg antibody against the two major microvillus membrane proteins (130 and 140 kDa) inhibited RDEC-1 adherence to microvilli. This result is consistent with evidence that the same two proteins act as the receptor molecules for AF/R1-mediated adherence, as previously demonstrated by Rafiee et al. (35). The LC-MS amino acid sequence analysis with database searches and a subsequent inhibition experiment with guinea pig anti-rabbit SI antibody indicated that these two proteins are the subunits of rabbit intestinal SI. SI is a major intrinsic glycoprotein of the rabbit intestinal brush border membrane and plays a key role in the final digestion of glycogen and starch (23). The fact that a membrane-bound enzyme SI serves as a receptor for RDEC-1 AF/R1 fimbriae may explain several findings in previous and present experiments. RDEC-1 has been found to adhere to the brush borders of adult rabbits but not to those of baby rabbits (12, 13). This finding was due to the demonstration that no SI appears to be present in the baby intestine, as mRNA of SI is expressed only in the intestines of adult rabbits (4, 27). In this study, we observed that the numbers of bacteria that adhered to the individual brush borders with the same morphology differed from 0 to over 25 per brush border. The morphologic quality of brush borders as seen under the 1,000 power oil immersion with Nomarski optics had no relationship to the quality of microvilli in terms of the maximum adherence (data not shown). These findings may be explained by the digestion of SI by pancreatic enzymes (elastase in particular) and release from the brush border membrane (23). In that case, little or no SI will be left on the brush border membrane if the membrane had contact with the pancreatic enzymes, although the morphology of microvilli appears normal.

Glycosylation of each SI subunit is assumed initially from the difference between the mass as determined from SDS-PAGE and the mass as deduced from the DNA sequence. This is reflected in the fact that the molecular mass of isomaltase is 140 kDa and the mass as deduced is 114,717 Da, while the molecular mass of sucrase is 130 kDa and the DNA-deduced mass is 95,311 Da (23, 38). In fact, both subunits of SI are glycosylated with both N- and O-linked oligosaccharides (14, 32). Removal of either sialic acid or galactose resulted in greatly diminished adherence to brush borders, as did the removal of either O- or, particularly, N-linked oligosaccharides. SI is also known to serve as the receptor for the diarrheagenic C. difficile toxin A. Rabbit SI has been demonstrated to be a glycoprotein containing oligosaccharides with terminal galactose residues by blocking of toxin binding by the α-galactose specific lectin Bandeirea simplicifolia as well as inhibition by pretreatment of rabbit brush borders by α-galactosidase (16, 34). There are clear protein sequence homologies between the sucrase and isomaltase portions of SI, particularly between SI amino acids 70 to 860 (isomaltase portion) and 959 to 1750 (sucrase portion), which appear to be a result of partial gene duplication (23). With the similarities between the two subunits on the protein level and the simultaneous glycosylation processing of the pro-SI in the Golgi apparatus prior to cleavage into individual subunits (32), it is likely that similar oligosaccharide side chains are attached to both sucrase and isomaltase. This may explain why chicken antibody raised to each individual SI subunit (with no cross-contamination) equally inhibits AF/R1 adherence to microvilli. The rabbit SI complex as purified by Pothoulakis et al. (34) differed from the AF/R1 receptor complex as purified by Rafiee et al. (35); in the former case the SI complex was detergent soluble, but in the latter case the AF/R1 receptor complex was not. Future studies will be designed to resolve this seeming discrepancy.

Carbohydrates in the forms of glycoproteins and glycolipids have been reported to play an important role in the binding of gram-negative bacteria to receptors on host epithelial cells (11, 25, 26, 28, 33, 39). In our effort to find additional potential receptors for AF/R1 fimbriae in the rabbit intestinal brush borders, we have extracted lipids from the brush borders. As previously reported (5, 22), the major lipids of rabbit small intestinal brush borders, including cholesterol, phosphocholine, phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylserine (phospholipids), and monohexosyloceramide (glycolipids), were well represented in our HPTLC chromatogram. When the AF/R1-mediated adherence of RDEC-1 to commercially available lipid standards was examined by HPTLC overlay assay, both RDEC-1 and M34 adhered to asialo-GM1, phosphatidylethanolamine, and phosphatidylserine. RDEC-1 adhered to bovine type I galactosylceramide, while M34 did not, indicating that the adherence is AF/R1 specific. The RDEC-1 adhesion to asialo-GM1 is likely not biologically relevant, since the small intestinal brush borders did not contain the glycolipid as shown in this study and as previously reported (5, 22). In addition, the adherence to phosphatidylethanolamine and phosphatidylserine is not mediated by AF/R1 fimbriae, since M34 lacking the fimbriae also bound to those two phospholipids. Interestingly, those two phospholipids may serve as receptors for M34, which is able to infect rabbit large intestine (42), although M34 causes less severe diarrhea than RDEC-1.

The AF/R1 fimbrial glycolipid putative receptor in the rabbit small intestinal brush borders is tentatively identified as type I galactosylceramide (Galβ1-1Cer). This conclusion was made on the basis of the following evidence: (i) RDEC-1 adhered to the commercially available bovine type I galactosylceramide and to the monhexosylceramide band in the lipid extract of small intestinal brush borders, while M34 lacking AF/R1 fimbriae did not adhere to these two glycolipids; (ii) RDEC-1 adherence to the two glycolipids was partially inhibited in the presence of 0.5 M galactose; (iii) the monohexosylceramide in the extract migrated a distance similar to that of the bovine type I galactosylceramide on the HPTLC plate; and (iv) rabbit small intestine does not contain glucosylceramide (monohexosylceramide) that migrates similarly to type I glactosylceramide on the thin-layer chromatograph (3). A slight difference in migration of type I galactosylceramide in bovine brain and in rabbit small intestinal brush borders can be explained by the different fatty acid chains in the ceramide (5).

We have demonstrated that both a glycoprotein complex and a glycolipid are present in rabbit small intestinal brush borders and may serve as receptor molecules for E. coli AF/R1 fimbriae. The presence of the multiple putative receptors for a single fimbria can be supported by similar findings with two porcine ETEC fimbriae, 987P, and K88ab. Khan et al. (28) identified three receptors (type I galactosylceramide, sulfatide, and glycoproteins) for 987P fimbriae, and Grange et al. (20) identified transferrin, Billey et al. (3) identified mucin-type sialoglycoproteins of 210 and 240 kDa, and Payne et al. (33) found type I galactosylceramide and other β-linked glycolipids as receptors for K88ab fimbriae. Karlsson's model for bacterial adherence to glycoconjugate receptors on eukaryotic host cell membranes postulates that bacterial tropism is typically mediated by a specific first-step adhesin-receptor interaction and that a second-step receptor with low affinity is used to strengthen the adhesion (26). For AF/R1 fimbria-mediated adhesion to rabbit brush border membranes, the first-step interaction may be characterized by the binding of AF/R1 fimbriae to the 130- and 140-kDa microvillus proteins, whereas second-step interactions may involve binding of AF/R1 to type I galactosylceramide. The interactions of bacterial surface adhesins other than AF/R1 fimbriae with intestinal phosphatidylethanolamine and phosphatidylserine could further strength the adhesion.

Future studies will focus on the purification and additional biochemical characterization of these receptor molecules as well as elucidate relevant in vivo binding events. The identification of proteolytic fragments of rabbit SI with receptor binding activity as well as the characterization of the oligosaccharide moities present on these fragments is planned. Purification and structural verification of the identity of the glycolipid migrating at the galactosylceramide mobility will also be undertaken. By characterizing the molecular mediators of AF/R1-mediated adherence, a better understanding of the subsequent development of the attaching-effacing lesion and EPEC disease should result. Ultimately, it is hoped that these and similar studies will lead to development of practical means to inhibit diarrheagenic E. coli fimbria-mediated attachment in vivo.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

C. Pothoulakis, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, Mass., kindly provided guinea pig anti-rabbit SI. Marcia Wolf, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, generously supplied E. coli strain M34. We thank Ruby Singh, Elyose Fleming, Ester Oh, Jeffrey Anderson, and John Barringer, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, for their technical assistance. We thank E. Boedeker, University of Maryland, Baltimore, and Hakon Leffler, Lund University, Lund, Sweden for valuable suggestions.

This study was supported by Department of Veterans Affairs Research Service/Department of Defense Research Award WR13 Tab 46D (to Y.S.K. and F.J.C.) and by USPHS grant DK17938 (to Y.S.K.). The W.M. Keck Biomedical Mass Spectrometry Laboratory is funded by a grant from the W.M. Keck Foundation, and the University of Virginia Biomedical Research Facility is funded by a grant from the University of Virginia Pratt Committee.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beachey E H. Bacterial adherence; adhesin receptor interactions mediating the attachment of bacteria to mucosal surfaces. J Infect Dis. 1981;143:325–345. doi: 10.1093/infdis/143.3.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berendson R, Cheney C P, Boedeker E C. Species-specific binding of purified pili from the Escherichia coli RDEC-1 to rabbit intestinal mucosa. Gastroenterology. 1983;85:837–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Billey L O, Erickson A K, Francis D H. Multiple receptors on porcine intestinal epithelial cells for the three variants of Escherichia coli K88 fimbrial adhesin. Vet Microbiol. 1997;59:203–212. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(97)00193-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boll W, Schmid-Chanda T, Semenza G, Mantei N. Messenger RNAs expressed in intestine of adult but not baby rabbits. Isolation of cognate cDNAs and characterization of a novel brush border protein with esterase and phospholipase activity. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:12901–12911. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breimer M E, Hansson G C, Karlsson K A, Leffler H. Blood group type glycosphingolipids from the small intestine of different animals analysed by mass spectrometry and thin-layer chromatography. A note on species diversity. J Biochem. 1981;90:589–609. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a133513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bretscher A, Weber K. Purification of microvilli and an analysis of the protein components of the microfilament core bundle. Exp Cell Res. 1978;116:397–407. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(78)90463-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burrows M R, Sellwood R, Gibbons R A. Haemagglutinating and adhesive properties associated with the K99 antigen of bovine strains of Escherichia coli. J Gen Microbiol. 1976;96:269–275. doi: 10.1099/00221287-96-2-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cantey J R. The rabbit model of Escherichia coli (strain RDEC-1) diarrhea. In: Boedeker E C, editor. Attachment of organisms to the gut mucosa. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press, Inc.; 1981. pp. 39–47. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cantey J R, Blake R K. Diarrhea due to Escherichia coli in the rabbit: a novel mechanism. J Infect Dis. 1977;135:454–462. doi: 10.1093/infdis/135.3.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cantey J R, Blake R K, Williford J R, Moseley S L. Characterization of the Escherichia coli AF/R1 pilus operon: novel genes necessary for transcriptional regulation and for pilus-mediated adherence. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2292–2298. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.5.2292-2298.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cassels F J, Wolf M W. Colonization factors of diarrheagenic E. coli and their intestinal receptors. J Ind Microbiol. 1995;15:214–226. doi: 10.1007/BF01569828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheney C P, Boedeker E C, Formal S B. Quantitation of the adherence of an enteropathogenic Escherichia coli to isolated rabbit intestinal brush borders. Infect Immun. 1979;26:736–743. doi: 10.1128/iai.26.2.736-743.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheney C P, Schad P A, Formal S B, Boedeker E C. Species specificity of in vitro Escherichia coli adherence to host intestinal cell membranes and its correlation with in vivo colonization and infectivity. Infect Immun. 1980;28:1019–1027. doi: 10.1128/iai.28.3.1019-1027.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cogoli A, Semenza G. A probable oxocarbonium ion in the reaction mechanism of small intestinal sucrase and isomaltase. J Biol Chem. 1975;250:7802–7809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donnenberg M S. Interactions between enteropathogenic Escherichia coli and epithelial cells. J Infect Dis. 1999;28:451–455. doi: 10.1086/515159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eglow R, Pothoulakis C, Itazkowitz S, Israel E J, OiKeane C J, Gong D, Gao N, Xu Y L, Walker W A, LaMont J T. Diminished Clostridium difficile toxin A sensitivity in new born rabbit ileum is associated with decreased toxin A receptor. J Clin Invest. 1992;90:822–829. doi: 10.1172/JCI115957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feracci H, Maroux S, Bonicel J, Desnuelle P. The amino acid sequence of the hydrophobic anchor of rabbit intestinal brush border aminopeptidase N. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1982;684:133–136. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(82)90057-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Finlay B B, Falkow S. Common themes in microbial pathogenicity. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53:210–230. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.2.210-230.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goosney D L, de Grado M, Finlay B B. Putting E. coli on a pedestal: a unique system to study signal transduction and the actin cytoskeleton. Trends Cell Biol. 1999;9:11–14. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(98)01418-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grange P A, Mouricout M A. Transferrin associated with the porcine specific for K88ab fimbriae of Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1996;64:606–610. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.2.606-610.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harlow E, Lane D. Antibodies: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hauser H, Howell K, Dawson R M C, Bowyer D E. Rabbit small intestinal brush border membrane preparation and lipid composition. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1980;602:567–577. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(80)90335-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hunziker W, Spiess W, Semenza G, Lodish H F. The sucrase-isomaltase complex: primary structure, membrane-orientation, and evolution of a stalked, intrinsic brush border protein. Cell. 1986;46:227–234. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90739-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Isaacson R E, Fusco P E, Brinton C C, Moon H W. In vitro adhesion of Escherichia coli to porcine small intestinal epithelial cells: pili as adhesive factors. Infect Immun. 1978;21:392–397. doi: 10.1128/iai.21.2.392-397.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karlsson K-A, Stromberg N. Overlay and solid-phase analysis of glycolipid receptors for bacteria and virus. Methods Enzymol. 1987;138:220–232. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)38019-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karlsson K A. Animal glycosphingolipids as membrane attachment sites for bacteria. Annu Rev Biochem. 1989;58:309–350. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.58.070189.001521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keller P, Zwicker E, Mantei N, Semenza G. The levels of lactase and of sucrase-isomaltase along the rabbit small intestine are regulated both at the mRNA level and post-translationally. FEBS Lett. 1992;313:265–269. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)81206-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khan A S, Johnston N C, Goldfine H, Schifferli D M. Porcine 987P glycolipid receptors on intestinal brush borders and their cognate bacterial ligands. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3688–3693. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.9.3688-3693.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krivan H C, Nilsson B, Lingwood C A, Ryu H. Chlamydia trachomatis and Chlamydia pneumoniae bind specifically to phosphatidylethanolamine in HeLa cells and to GalNAc β1-4Gal β1-4Glc sequences found in asialo-GM1 and asialo-GM2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;175:1082–1089. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)91676-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mandal A, Naaby-Hansen S, Wolkowicz M J, Klotz K, Shetty J, Reteif J D, Coonrod S A, Kinter M, Sherman N, Cesar F, Flickinger C J, Herr J C. FSP95, a testis-specific 95-kilodalton fibrous sheath antigen that undergoes tyrosine phosphorylation in capacitated human spermatozoa. Biol Reprod. 1999;61:1184–1197. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod61.5.1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McQueen C E, Boedeker E C, Le M, Hamada Y, Brown W R. Mucosal immune response to RDEC-1 infection: study of lamina propria antibody-producing cells and biliary antibody. Infect Immun. 1992;60:206–212. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.1.206-212.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Naim H Y, Joberty G, Alfalah M, Jacob R. Temporal association of the N- and O-linked glycosylation events and their implication in the polarized sorting of intestinal brush border sucrase-isomaltase, aminopeptidase N, and dipeptidyl peptidase IV. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:17961–17967. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.25.17961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Payne D, O'Reilly M, Williamson D. The K88 fimbrial adhesin of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli binds to β1-linked galactosyl residues in glycosphingolipids. Infect Immun. 1993;61:3673–3677. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.9.3673-3677.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pothoulakis C, Gilbert R J, Cladaras C, Castagliuolo I, Semenza G, Hitti Y, Monterief J S, Linevsky J, Kelly C P, Nikulasson S, Desai H P, Wilkins T D, LaMont J T. Rabbit sucrase-isomaltase contains a functional intestinal receptor for Clostridium difficile toxin A. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:641–649. doi: 10.1172/JCI118835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rafiee P, Leffler H, Byrd J C, Cassels F J, Boedeker E C, Kim Y S. A sialoglycoprotein complex linked to the microvillus cytoskeleton acts as a receptor for pilus (AF/R1) mediated adhesion of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (RDEC-1) in rabbit small intestine. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:1021–1029. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.4.1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ruhl S, Sandberg A L, Cole M F, Cisar J O. Recognition of immunoglobulin A1 by oral actinomyces and streptococcal lectins. Infect Immun. 1996;64:5421–5424. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.5421-5424.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schlager T A, Wanke C A, Guerrant R L. Net fluid secretion and impaired villous function induced by colonization of the small intestine by nontoxigenic colonizing Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1990;58:1337–1343. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.5.1337-1343.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sjöström H, Norén O, Christiansen L A, Wacker H, Spiess M, Bigler-Meier B, Rickli E E, Semenza G. N-Terminal sequences of pig intestinal sucrase-isomaltase and pro-sucrase-isomaltase. FEBS Lett. 1982;148:321–325. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(82)80833-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Warner L, Kim Y S. Intestinal receptors for microbial attachment. In: Farthing M J G, Kensch G T, editors. Enteric infection: mechanisms, manifestations and management. New York, N.Y: Raven Press; 1989. pp. 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wennerås C, Holmgren J, McConnell M M, Svennerholm A-M. The binding of bacteria carrying CFAs and putative CFAs to rabbit intestinal brush border membranes. In: Wädstrom T, Mäkelä P H, Svennerholm A-M, Wolf-Watz H, editors. Molecular pathogenesis of gastrointestinal infections. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1991. pp. 327–330. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wennerås C, Holmgren J, Svennerholm A M. The binding of colonization factor antigens of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli to intestinal cell membrane proteins. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1990;54:107–112. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(90)90266-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wolf M K, Andrews G P, Fritz D L, Sjogren R W, Jr, Boedeker E C. Characterization of the plasmid from Escherichia coli RDEC-1 that mediates expression of adhesin AF/R1 and evidence that AF/R1 pili promote but are not essential for enteropathogenic disease. Infect Immun. 1988;56:1846–1857. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.8.1846-1857.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang X-F, Milhiet P E, Gaudoux F, Crine P, Boileau G. Complete sequence of rabbit kidney aminopeptidase N and mRNA localization in rabbit kidney by in situ hybridization. Biochem Cell Biol. 1993;71:278–287. doi: 10.1139/o93-042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]