Abstract

A common feature of many different organisms causing bacteremia is the ability to avoid the bactericidal effects of normal human serum. In Haemophilus influenzae encapsulated strains are particularly serum resistant; however, we found that a nonencapsulated strain (R2866) isolated from the blood of an immunocompetent child with meningitis who had been successfully immunized with H. influenzae type b conjugate vaccine was serum resistant. Since serum resistance usually involves circumventing the action of the complement system, we defined the deposition of various complement components on the surfaces of this H. influenzae strain (R2866), a nonencapsulated avirulent laboratory strain (Rd), and a virulent type b encapsulated strain (Eagan). Membrane attack complex (MAC) accumulation correlated with the loss of bacterial viability; correspondingly, the rates of MAC deposition on the serum-sensitive strain Rd and the serum-resistant strains differed. Analysis of cell-associated immunoglobulin G (IgG), C1q, C3b, and C5b indicated that serum-resistant H. influenzae prevents MAC accumulation by delaying the synthesis of C3b through the classical pathway. Among the initiators of the classical pathway, IgG deposition contributes most of the C3 convertase activity necessary to start the cascade ending with MAC deposition. Despite similar IgG binding, strain R2866 delays C3 convertase activity compared to strain Rd. We conclude that strain R2866 can persist in the bloodstream, in part by inhibiting or delaying C3 deposition on the cell surface, escaping complement mediated killing.

Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae (NTHI) strains are respiratory tract commensals in a majority of the population. Disease due to NTHI in the form of otitis media, sinusitis, or bronchitis can follow colonization. Pneumonia due to NTHI can lead to bacteremia and meningitis, especially in patients with compromised immune function or inadequate innate respiratory defense mechanisms (9). In some cases, NTHI meningitis is the result of an anatomical defect near the middle ear that allows for passage of NTHI into the central nervous system. In these cases, the virulence of NTHI is assumed to play a small role, in that it is a passive introduction of bacteria into a new niche which caused disease. In fact, most invasive ntHi isolates from such patients do not have a genome structure that distinguishes them from commensal bacteria (19). However, when invasive NTHI disease occurs in an immunocompetent individual with no anatomic defects, the recovered isolate is likely to be novel: the features that allowed it to invade and persist in the bloodstream must be unique among commensal NTHI strains. This work extends the characterization of an invasive NTHI strain (R2866) isolated from the blood of an immunocompetent child with meningitis who had been immunized with the H. influenzae type b (Hib) conjugate vaccine (21).

Initial experiments indicated that strain R2866 survived in defibrinated blood from normal adult humans to the same extent as a prototypic, virulent type b strain (Eagan or Ela). Although blood survival was first used to gain insight into the age-dependent susceptibility to Hib infections (8), the blood bactericidal activity was ultimately shown to be due to antibody- and complement-mediated bacteriolysis. We reasoned that strain R2866 had unique virulence, escaping bacteriolysis, as commensal NTHI strains are reported to be serum susceptible (1, 12, 16–18, 29).

A common feature of the invasive isolates of many species is the ability to avoid the bactericidal effects of serum (10, 11, 23). Simply described, a bacterium that can survive in human blood has the potential to spread to different organs, escaping the killing mechanism of complement- and antibody-mediated opsonization. In species comprising pathogens and commensals, serum resistance is often attributed to the pathogens as an acquired trait that allowed them to cause disease in their host. In particular, serum resistance is a common feature of meningococci isolated from blood or cerebrospinal fluid (6). Hib is one such organism that fits this classification. Protected by its polyribosylribitol phosphate capsule, Hib was a common cause of bacteremia, meningitis, and other systemic diseases until the introduction of the Hib conjugate vaccines (2). In the laboratory, encapsulated strains are particularly serum resistant; however, strain R2866 survives to a similar level in normal adult human serum without the benefit of a capsule. The mechanism of resistance used by this bacterium must be different from that of the previously described encapsulated strains.

To define this mechanism, we used flow cytometry to explore the complement interactions responsible for the bactericidal activity of normal human serum with a panel of Haemophilus strains. With the recent advances in flow cytometry, fluorescence detection is sensitive enough that individual bacteria can be analyzed (27). Complement proteins on the surfaces of serum-resistant and serum-sensitive Haemophilus strains were monitored throughout the course of a kinetic bactericidal assay with complement-specific antibodies. In a kinetic assay, this results in multiple levels of data such as the order, magnitude, and rate of component binding to different bacteria. This can be described on a per-cell basis, with thousands of cells contributing to each analysis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Strain R2866, described as Int1 in reference 21, is a biotype V H. influenzae strain isolated from the blood of an immunocompetent child with signs of meningitis. This strain harbors a 54-kb plasmid encoding a β-lactamase as well as a novel bacteriophage (unpublished data). Rd KW20 is the type d capsule-deficient H. influenzae strain for which the chromosomal sequence was published (7), while strain R906 is an antibiotic-resistant derivative of Rd KW20 that is resistant to five antibiotics (15); both are avirulent in animal models and are serum sensitive. Strain Ela (Eagan) is a well-studied virulent Hib strain described in reference 25. The NTHI strains M318 and M319 are phosphorylcholine (ChoP)-positive and -negative isotypes, respectively, characterized and supplied by Jeff Weiser, University of Pennsylvania. Type a to f capsular strains are from the American Type Culture Collection (a, ATCC 9006; b, ATCC 9795; c, ATCC 9007; d, ATCC 9008; e, ATCC 8142; f, ATCC 9833). All bacteria were grown in Difco brain heart infusion broth (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, Md.) supplemented with 10 μg each of hemin, l-histidine, and β-NAD+ (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) per ml (sBHI). Difco Bacto-Agar (Becton Dickinson) was added at 15 g/liter to sBHI for solid media.

Genetic definition of capsulation status.

Export of the type b capsule of H. influenzae is not a stable genetic trait. With in vitro passage, type b strains can lose bexA present in the bridging portion of the type b capsule gene cluster (4). This results in an isolate which fails to agglutinate with anti-b antisera and is classified as nontypeable. Although the initial report (21) failed to detect intracellular or cell membrane-associated type b antigen or the surface presence of capsular type a, c, d, e, or f with a combination antiserum, the combination antiserum gives ambiguous results with reference strains (unpublished observations). To verify that strain R2866 was an NTHI strain, we examined whole-cell DNA by PCR using primers specific for each capsular type (5). In addition, whole-cell DNA was digested with EcoRI, electrophoresed in agarose, and examined for remnants of the cap b gene cluster by Southern analysis using the 18-kb cap locus from pUO38 (4) which was PCR amplified using primers flanking the BamHI site in pBR322. This fragment was labeled using a Klenow-based random hexamer labeling kit with the digoxigenin system from Boehringer Mannheim Corp. (Indianapolis, Ind.).

Normal human serum and antibodies.

Under approval of the University of Missouri Institutional Review Board, consenting adult volunteers between the ages of 20 and 33 years donated blood for collection of sera. None of the donors participate in Haemophilus research. After clotting at room temperature, the normal human sera (NHS) component was harvested aseptically and stored at −70°C until use. Goat anti-human C1q, C3, C9, and factor H and rabbit anti-human C5 and membrane attack complex (MAC) were purchased from Calbiochem (La Jolla, Calif.). All antibodies directed towards complement components are polyclonal and are thus capable of recognizing uncleaved components as well as many of the larger cleaved components. Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit and FITC-conjugated rabbit anti-goat immunoglobulins were purchased from Sigma. TEPC-15 is a mouse IgA myeloma product that reacts specifically with ChoP (Sigma). FITC conjugated anti-mouse immunoglobulin A (IgA) was also supplied by Sigma. FITC- and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-human IgG, IgA, and IgM antibodies were purchased from Chemicon (Temecula, Calif.). Michael Apicella (University of Iowa) generously supplied monoclonal antibody 3F11, specific for a site of sialylation in H. influenzae lipooligosaccharide (LOS).

Kinetic bactericidal assay.

Bacteria were grown to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.6 and resuspended in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 0.1% gelatin (PBSG) to an OD600 of 0.2 (108 CFU/ml); 0.2 ml of this solution was added to 0.8 ml of 50% serum (serum diluted in PBSG). Aliquots of this mixture were removed immediately after mixing and the mixture was incubated at 37°C; additional samples were obtained 5, 15, 30, and 45 min later. Bacterial density was estimated by serial dilution and plating on sBHI agar. Where indicated, EGTA was added to serum to yield a final concentration of 5 mM (Sigma). When using EGTA, the assay mix was supplemented with 9 mM Mg+2 to maintain the enzymatic activity of the alternate pathway (26). C-reactive protein (CRP) was depleted from serum as described elsewhere (29). Briefly, 1 ml of washed ChoP-agarose beads (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.) was resuspended in serum in a microcentrifuge tube and allowed to incubate at 4°C for 30 min with intermittent vortexing. This mixture was centrifuged, and the serum was removed and immediately used in the bactericidal assay described above.

Outer membrane protein purification and electrophoresis.

One hundred milliliters of Haemophilus cells grown to an OD600 of 0.9 in sBHI was washed once in 30 mM Tris (pH 8.0) and resuspended in 20 ml of the same solution. This volume was subjected to two rounds of French pressure cell treatment at 15,000 lb/in2 to lyse the cells. After 20 min of incubation with 2 mg of lysozyme (Sigma), the suspension was cleared of remaining cells by a low-speed centrifugation, followed by a high-speed centrifugation to pellet the cell membrane debris. Resuspension in 200 μl of water was followed by 20 min of Sarkosyl extraction (112 mM N-lauryl-sarcosine [Sigma] in 0.1 M Tris [pH 7.6] at room temperature in a final volume of 2 ml. This solution was centrifuged at 48,000 rpm in a Beckman Vti-80 rotor for 1.5 h at 20°C. The pellet was resuspended in 100 μl of water, and the protein content was quantified by the bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce). An aliquot containing 10 μg of protein was boiled and electrophoresed on a Tris-glycine–10% polyacrylamide gel under standard conditions. Transfer to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane was done using a submerged protein transfer cassette under a 250-mA current. Following exposure to serum, the transfer membranes were blotted for immunoglobulins by methods described below.

Immunoblotting.

Bacteria were harvested and diluted as described above. An inoculation in serum was made such that 0.5 ml of the bacterial stock at 108 CFU/ml was added to 0.25 ml of NHS. At various time points an aliquot (usually one-fifth to one-third of the bacterium-sera mixture) was removed and diluted in 1 ml of PBSG. This solution was centrifuged, washed again in 0.5 ml of PBSG, and brought to a final concentration of 5 × 105 CFU/μl. This solution was diluted to give a range within the initial concentration and 2.5 × 104 CFU/ml. Two microliters of each dilution was dotted onto nitrocellulose and allowed to dry. This blot was then blocked in 3% nonfat skim milk in PBS overnight at 4°C on a shaking platform. Anti-human IgG, C3, C5, C9, or C5b-9 was added in a 1:5,000 dilution in 40 ml of the 3% skim milk solution and left for 3 h at 4°C on a shaking platform. Washes were done with the blocking solution supplemented with 0.1% Tween 80 (Sigma). Horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary antibodies were added in a 1:5,000 dilution and allowed to incubate in the same fashion as the primary antibody. The blot was again washed, and detection was made with the ECL chemiluminescence detection kit from Amersham (Piscataway, N.J.). The dot intensity was quantified by spot densitometry on an IS-1000 digital imaging system. These assays were done in triplicate, and the relative intensities were averaged and plotted.

Flow cytometry.

To monitor complement evolution of bacterial surfaces during the course of the bactericidal kinetic assay, bacteria removed from the serum mixture were stained for complement components and analyzed by flow cytometry in parallel with serial dilution and plating. This allowed us to correlate bacterial death with the time course of complement deposition. At a given time point, 0.2 ml of the cell-serum mixture was removed and immediately diluted in 1 ml of PBSG. The cells were centrifuged, resuspended by pipetting in 0.2 ml of 1% p-formaldehyde (Sigma), and incubated at room temperature for 10 min to fix them for further staining. After the fixing step, the cells were again diluted in 1 ml of PBSG and centrifuged to remove excess fixing solution. The cells were resuspended in a 1:100 dilution of primary antibody (anti-C1q, -C3, -C5, -C9, or -MAC in PBSG with 0.3% bovine serum albumin [BSA] [Sigma]) and incubated on ice for 30 min. After this incubation, the cells were washed in 1 ml of PBSG with 0.3% BSA, resuspended in a 1:100 dilution of secondary antibody (FITC anti-rabbit or FITC anti-goat immunoglobulin in PBSG with 0.3% BSA), and incubated on ice for 30 min. After the second antibody incubation, the cells were washed in 1 ml of PBSG and resuspended in 1 ml of PBS. This mixture was analyzed with a Becton Dickinson FACS Vantage set at 488-nm excitation and 530-nm absorption of the fluorescein fluorochrome; 10,000 counts per run were obtained, and the geometric mean fluorescence of the gated population versus counts were plotted in two dimensions. Forward and side scatter were monitored but were not subject to gating, as all cells, dying and alive, were important in this analysis. All combinations of strains and antibodies were tested to determine background antibody binding or cross-reactivity. All of these controls proved to contribute negligible levels of fluorescence compared to the positive controls. Assessment of ChoP decoration was also done with this technique. However, the cells were not incubated in sera, as ChoP decoration is an inherent property of their LOS. Cells were incubated with the TEPC-15 antibody and detected with FITC-labeled anti-mouse IgA as described above.

LOS electrophoresis.

LOS was prepared from Haemophilus by the hot-phenol method (3). Two milliliters of mid-log-phase culture was harvested and washed thoroughly in PBS with 0.15 mM CaCl2 and 0.5 mM MgCl2. The washed pellet was resuspended in 300 μl of water and extracted with an equal volume of 90% phenol at 68°C. After 15 min at 68°C, the mixture was cooled to 10°C and centrifuged. The aqueous layer was removed, and the phenol layer was reextracted with 300 μl of water. After repeating of the incubation and separation, the aqueous layers were combined and adjusted to 0.5 M NaCl. Ten volumes of 100% ethanol were added, and the mixture was placed at −20°C for 6 to 8 h. Centrifugation and resuspension of the pellet in 100 μl of water was followed by another precipitation step as described above with final resuspension in 50 μl of water. For electrophoresis the solution was diluted 1:1 in solubilization buffer (0.1 M Tris [pH 8.3], 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 20% sucrose, 1% β-mercaptoethanol, 0.001% bromophenol blue) and boiled for 5 min. LOS was electrophoresed on a 15% Tris-glycine gel with a 4% stacking gel. Silver staining was performed as described elsewhere (28). Alternately, the gel was blotted to PVDF (Boehringer Mannheim) by standard transfer techniques and incubated in dilute NHS (1:500) for 1 h at room temperature. Probing for C3 was performed as described in “Immunoblotting” above. Strain Rd treated with LOS was subjected to a kinetic bactericidal assay with parallel C3 analysis by flow cytometry as described above. When used in inhibition studies, 5 to 10 μl of the LOS preparation was added to 100 μl of a 108-CFU/ml mixture of strain Rd.

Sialic acid detection with antibody 3F11.

Antibody to a sialylated epitope on H. influenzae LOS (3F11) was provided by Michael Apicella, University of Iowa. Standard enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) techniques before and after neuraminidase (Boehringer Mannheim) treatment were used to quantify binding of this antibody to whole cells fixed to a ELISA plate. Alkaline phosphatase-conjugated mouse anti-IgM (Sigma) was used to detect 3F11 antibody binding.

RESULTS

Serum resistance.

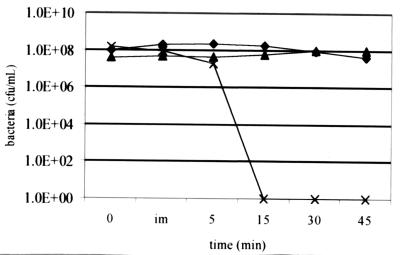

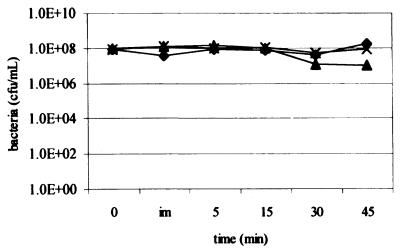

Survival in serum over time is depicted in Fig. 1. Strains R2866 and Rd are unencapsulated, while Eagan (Ela), a well-studied Hib strain, is encapsulated (see Materials and Methods). Strain R2866 shows a level of survival similar to that of Ela despite being unencapsulated. Heat inactivation of serum (55°C for 30 min) removes all bactericidal activity, as expected (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Bactericidal kinetic assay. Bacteria were inoculated in 40% serum incubated at 37°C, sampled at the times indicated, and quantitated using serial dilution and plating. im, immediate. Strains: ♦, R2866; ▴, Ela; ×, Rd.

Capsulation status.

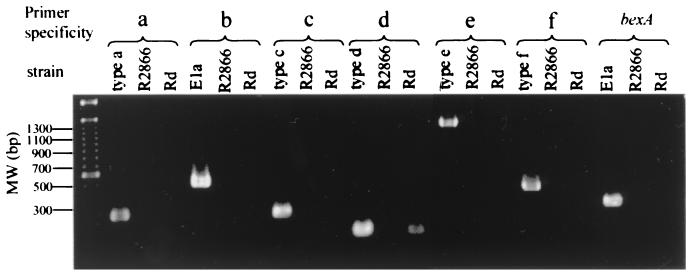

Figure 2 depicts the PCR products found with serotype-specific primers for reference H. influenzae strains and strain R2866. As can be seen, DNAs of portions of the type a, b, c, d, e, and f and bexA gene clusters is not detected in strain R2866 but are present in the reference strains.

FIG. 2.

PCR-based typing confirms nontypeable genotype of R2866. Primers specific to all five capsular types and bexA failed to amplify genes needed for capsule expression in strains R2866 and Rd (note that Rd is a derivative of a type d that has lost most of its capsule genes). The molecular size marker is the 100-bp marker from Gibco BRL (Gaithersburg, Md.).

Southern analysis of DNA harvested from strain R2866 with the cap b gene cluster did not detect homologous DNA, while strain E1a and the reference strains yielded the predicted bands (Fig. 3).

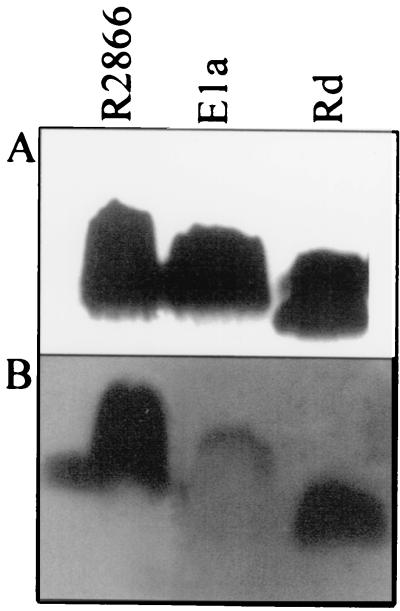

FIG. 3.

Southern blot of R2866 chromosomal DNA with a probe for capsule genes. The 18-kb capsulation locus of strain Ela (BamHI fragment of pUO38) was used as a probe against EcoRI-digested chromosomal DNAs from strains R2866, Rd, and Ela and the reference strains representing the five capsular types.

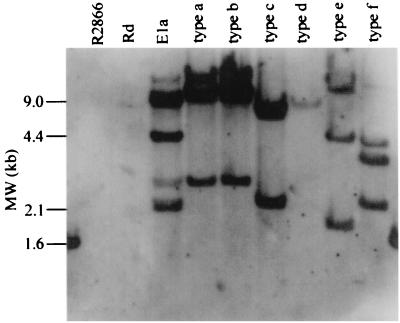

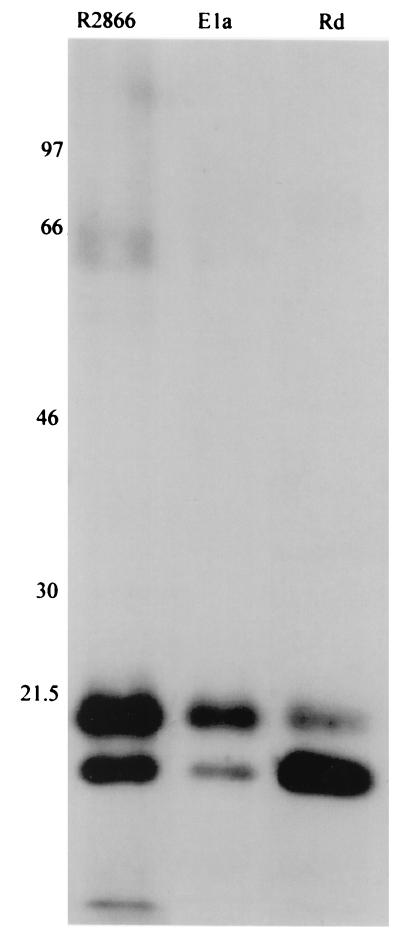

Outer membrane antigens recognized by NHS.

Serum antibody (IgG and IgM) is typically the most potent stimulator of the complement cascade. To determine if our NHS contained a lower titer of antibody to R2866, we performed immunoblotting of outer membrane proteins reacted with NHS after transfer. This blot was probed for human IgG to determine if different epitopes were recognized between these strains and to what degree of intensity (Fig. 4). The strains had similar patterns of antibody recognition, with two predominant reactive proteins. The serum-resistant strain had a greater number of faintly reactive bands than either the serum-resistant type b strain (strain Ela) or the serum-susceptible isolate (strain Rd). Analysis with secondary antibodies recognizing human IgG, IgA, and IgM showed a fainter but similar pattern, indicating that IgG is the predominant antibody responsible for recognition of these proteins (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Outer membrane proteins show similar affinities to human serum immunoglobulins. Outer membrane proteins of strains R2866, Ela, and Rd were electrophoresed in a Tris-glycine–10% polyacrylamide gel and transferred to PVDF. After incubation in NHS for 1 h, the blot was probed for human IgG binding. Approximate molecular masses in kilodaltons are indicated.

NHS kills via the classical pathway.

Having shown apparent equality in antibody-mediated complement initiation, we next determined the necessity of the classical arm (initiated through Clq, usually by antibody) versus the alternate arm (initiated through LOS-mediated C3 cleavage). The classical arm requires calcium as a cofactor of the enzymatic activity that ultimately leads to the C3 convertase function. Treatment of serum with EGTA will deplete calcium levels, and subsequent supplementation with magnesium will ensure proper alternative pathway function. Figure 5 demonstrates a near-complete loss of bactericidal activity upon EGTA treatment. Given similar antibody affinities but a difference in killing, other components of the complement system were analyzed to define the strategy used by R2866 to become serum resistant.

FIG. 5.

EGTA treatment of sera. Bactericidal kinetic assay as in Fig. 1 except that the serum was treated with 5 mM EGTA and contained 9 mM MgCl2. im, immediate. strains: ♦, R2866; ▴, Ela; ×, Rd.

Serum resistance is due to less C3 binding.

Initially, immunoblots were used to characterize the difference in complement component binding between these strains. Throughout the course of the bactericidal assay, bacteria were removed from the serum mixture, dotted on nitrocellulose, and probed for complement components. This analysis indicated that the presence of MAC correlated with bacterial death. It also suggested that the amount of C5 per cell correlated with MAC levels; however, C3 appeared to be equal in Rd and R2866, implying that the serum resistance of R2866 lay in a differential C5 activation and not C3 activation (data not shown).

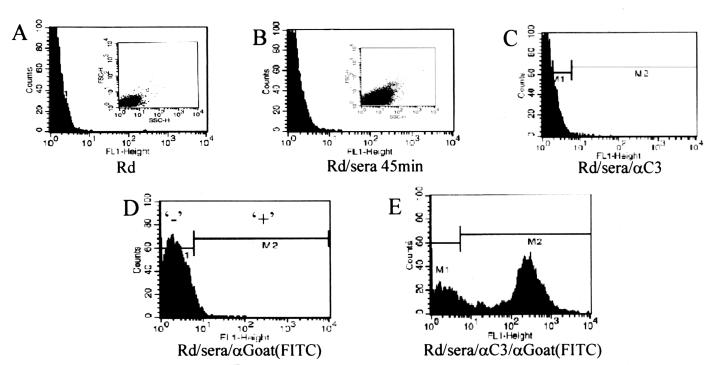

Flow cytometry was employed to verify these results while allowing a more detailed examination of the complement cascade during the bactericidal reaction. Throughout the course of the bactericidal kinetic reaction (such as that shown in Fig. 1) with strain Rd, aliquots were removed, fixed, and stained with antibodies to various complement components. Cells were scored as positive for complement binding if they were more fluorescent than cells treated in the same fashion without the primary antibody (Fig. 6). Forward- and side-scatter analysis suggested cell membrane distortion upon serum exposure (Fig. 6A and B), but it did not vary from strain to strain or throughout time (data not shown). As expected, those cells that scatter more light bound more complement proteins, but gating was not performed using light scatter, as fluorescence intensity, not light scatter, is the intended indicator of complement binding. Figure 7 describes two facets of the complement cascade during the bactericidal reaction with the three strains: the percentage of cells in the population that bound enough complement to be detectable and the geometric mean fluorescence of those positive cells. Gating was performed as shown in Fig. 6D, as cells within this gate cannot be considered positive for complement binding. The cells scored negative by gating include 95% of the population with nonspecific binding. Any fluorescence outside this gate is considered positive for complement binding. Within the population of an individual strain, considerable differences in complement binding exist, depending on which component is measured. With gating as described, the expected increase in percent positive cells occurred faster in Rd than in R2866 for some complement components. In some cases, complement binding was present in a large majority of the population of serum-resistant strains but at much lower values per cell than for strain Rd. In contrast, some cells showed high complement deposition; however, they made up a very small percentage of the population. Given the phase-variable nature of Haemophilus surface structures, these outliers are not unexpected (29). The use of the geometric mean (mean fluorescence of a population measured on a logarithmic scale) prevents these outliers from inappropriately skewing the true population average. Each geometric mean plotted in Fig. 7B, D, F, H, and J is calculated from 10,000 individual data points, each hypothetically representing one bacterium. The true number contributing to each mean can be calculated by figuring the percent positive (Fig. 7A, C, E, G, and I) out of the total count of 10,000. In general, the populations of positive cells show distributions similar to that seen in Fig. 6E.

FIG. 6.

Flow cytometry analysis of C3 deposition on strain Rd. y axis, counts per channel; x axis, fluorescence channel; insets, forward scatter versus side scatter. (A) Rd, no serum, no antibody; (B) Rd incubated in serum for 45 min, no antibody; (C) same as panel B with goat anti-C3 (αC3) only; (D) Same as panel B with anti-goat (FITC conjugated) only; (E) Same as panel B with anti-C3 and anti-goat (FITC conjugated).

FIG. 7.

Flow cytometry analysis of the complement cascade on H. influenzae strains R2866, Ela, and Rd. (A, C, E, G, and I) Percentage of cells in population in the positive gate (Fig. 4D); (B, D, F, H, and J) geometric mean of cells gated positive. im, immediate; time is in minutes. Strains: ♦, R2866; ▴, Ela; ×, Rd.

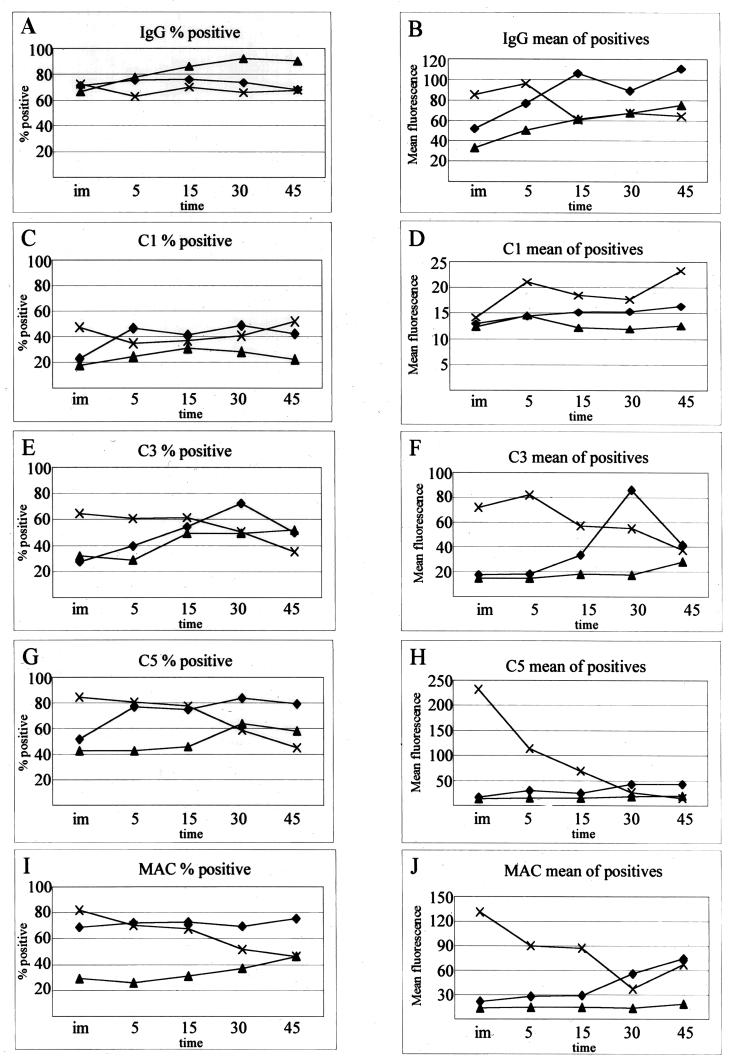

Both serum-resistant strains bound less complement than strain Rd (Fig. 7), with the accumulation of MAC corresponding with cell death in both unencapsulated strains (Fig. 8). Complement component deposition is barely detectable throughout the assay with strain Ela, rarely reaching levels above background. Strain R2866 delays significant MAC accumulation until 30 and 45 min after mixing with sera and shows no appreciable decline in viability until MAC accumulation (30 and 45 min of incubation).

FIG. 8.

Complement deposition and cell death over time with strains R2866 (A) and Rd (B). CFU per milliliter are from Fig. 1. geometric mean fluorescence of the positive gated population are from Fig. 7. im, immediate; time is in minutes.

Flow cytometry analysis accurately describes a number of facets of the complement cascade. Figure 8 shows data from Fig. 7 and 1 in a strain-by-strain comparison. With strain R2866 the complement cascade appears to occur in the predicted order, with cell death preceded by accumulation of C3b, then C5b (the polyclonal antibodies used will not distinguish between cleaved and uncleaved products; however, all cell bound components are cleaved), and finally MAC. The rate of complement component accumulation on strain Rd is very high, with all five measured components being present immediately after mixing. This rapid accumulation of complement components results in a higher rate of death of strain Rd. The deposition of complement component on strain Rd decreases after 15 mins of incubation when cells are dying or are dead.

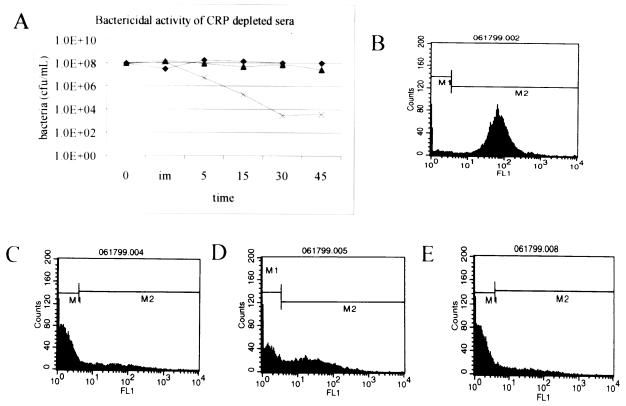

ChoP is not the primary target of NHS.

Unlike the immunoblot analysis, flow cytometry indicated a difference in C3 binding between strain R2866 and Rd. This difference is not explained by a large difference in IgG binding (Fig. 4 and 7B) or C1 binding (Fig. 7D). An alternative initiator of the classical pathway, CRP, has been described by others (29). The presence of ChoP epitopes on the LOS of Haemophilus has been proposed to make them more susceptible to CRP-initiated complement attack. If this phenomenon was solely responsible for serum resistance in strain R2866, removal of CRP from serum should prevent the serum-sensitive strain from dying and have no effect on the serum-resistant strains. Removal of CRP from serum decreased the rate of killing of strain Rd but did not completely remove the bactericidal activity from serum (Fig. 9A). This finding eliminates ChoP decoration of LOS as the sole mechanism responsible for serum resistance in R2866. Flow cytometric analysis of ChoP epitopes shows that strain R2866, as used in these assays, constitutes a heterogeneous population with respect to ChoP decoration compared to constitutive ChoP-positive (M318) and ChoP-negative (M319) strains (Fig. 9B to F). Despite a small amount of detectable ChoP, strain Rd is the most susceptible to killing by CRP-depleted sera.

FIG. 9.

ChoP decoration of LOS is not responsible for the serum resistance of strain R2866. (A) Same as Fig. 1 except that the serum was depleted of CRP; (B) M318 ChoP positive; (C) M319 (M318 isotype) ChoP negative; (D) R2866; (E) Rd.

LOS is not responsible for serum resistance.

To determine if any other features of LOS were responsible for serum resistance, we compared the LOS of R2866 on the basis of size, complement reactivity, and its ability to block the serum susceptibility of strain Rd. SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis has been used to characterize LOS differences in various H. influenzae strains (3). Purified LOSs from strains R2866 and Ela showed no striking differences in size or pattern after SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, while strain Rd had an LOS of greater mobility. After electrophoresis, the LOS was transferred to a membrane and exposed to serum, followed by washes and blotting with anti-C3 antibody. The LOSs of strains Rd and R2866 show similar amounts of C3 deposition on the membrane; Ela shows markedly less C3 accumulation (Fig. 10). Purified LOS from strain R2866 or strain Rd added to the kinetic bactericidal assay did not prevent the death of strain Rd (data not shown).

FIG. 10.

Complement reactivity of LOS. (A) LOS after electrophoresis and silver staining on a Tris-glycine–15% polyacrylamide gel. (B) Same as panel A except that after electrophoresis the LOS was transferred to PVDF and reacted with NHS, followed by probing with anti-human C3.

Serum-resistant R2866 does not have surface sialic acid.

Sialylation is one mechanism whereby Haemophilus and Neisseria strains make their LOSs less reactive to complement (12, 22). We tested the reactivity of a monoclonal antibody (3F11) that recognizes a site of sialylation on Haemophilus LOS (Michael Apicella, personal communication). This antibody did not react with strain R2866 before or after neuraminidase treatment (data not shown) but did react in an ELISA format with strain Rd. These data indicate that sialylation of LOS of R2866 does not appear to play a role in the serum resistance of that isolate.

Factor H binding does not account for the difference in serum resistance.

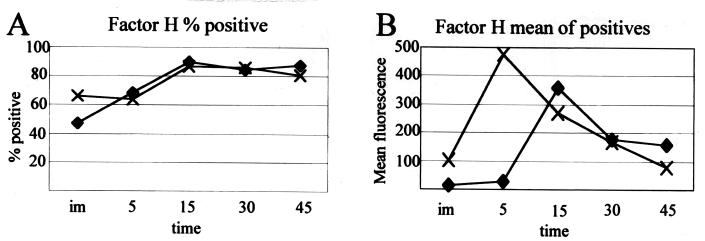

Figure 11 shows factor H binding on strains R2866 and Rd over time. Factor H binding has been attributed to serum resistance in certain strains of Neisseria (24). Factor H catalyzes the degradation of C3b into C3bi and destroys the alternative pathway C3 convertase, C3bBb. Serum-resistant Neisseria strains that bind factor H were shown to have a reduced amount of C3 bound compared to isogenic controls that do not bind factor H. Factor H binds to strains R2866 and Rd in a similar manner over time. The serum resistance of strain R2866 is not explained by factor H binding, as strain Rd appears to have equivalent binding.

FIG. 11.

Flow cytometry analysis of factor H binding on strains R2866 and Rd. (A) Percentage of the population positive for factor H binding over time; (B) geometric mean fluorescence of the positive cells counted in panel A. im, immediate; time is in minutes. Strains: ♦, R2866; ×, Rd.

DISCUSSION

We have described how an unusual pathogen circumvents a first-line defense mechanism of blood, the complement cascade. The ability to delay C3b binding and subsequent MAC accumulation enhances the ability of H. influenzae R2866 to survive in the bloodstream. By inhibition of the cascade at this early step, bacteriolysis and opsonization will be slow to occur, permitting this pathogen to replicate and seed a “privileged site.” The majority of adults have antibodies to a number of Haemophilus outer membrane constituents that are bactericidal (1). Although an extensive survey has not been reported, most investigators have commented on the near-uniform sensitivity of NTHI strains (1, 12, 16–18, 29) to NHS, particularly at a serum concentration of 40%.

The evolution of various complement components on the surface of R2866 (assessed by flow cytometry) suggests that the cascade occurs in the predicted order IgG, C1q, C3, C5, and C5b-9 (MAC). It is hard to assess the kinetics of binding of each component in one timed assay. The phenotype that we wished to correlate was a difference in complement binding and cell death. MAC accumulation correlated with cell death, and the rate of MAC deposition on the avirulent strain Rd was higher than those on serum-resistant strains. This indicates that the serum-resistant strains prevent MAC accumulation (and subsequent cell death) in a manner different from that of Rd. Analysis of cell-bound C1q, C3b, and C5b levels indicated that strain R2866 decreases MAC accumulation by delaying C3b binding or reactivity. Complement cascade inhibition appears to be global, in a fashion similar to the mechanism of capsule, in that less of all complement components are bound to strain R2866 in comparison to the serum-sensitive strain Rd. However, complement accumulation does occur on the strain R2866, albeit slowly, leading to MAC accumulation, whereas in this assay appreciable MAC accumulation does not occur on the Hib strain (strain Ela).

Flow cytometry was utilized to verify bacterium-complement interaction, as it offers the following advantages over immunoblots: (i) it allows for individual-cell analysis, while ignoring noncell sources of fluorescence (e.g., membrane fragments from dying cells); (ii) it does not rely on spot densitometry to retrieve a crude number (pixel intensity) that can be analyzed only in a relative fashion; and (iii) it is easily reproduced, ignoring variables such as dot size, bacterial density per dot, enzymatic conversion of signal, and length of exposure to film (if using chemiluminescence). The dynamics of complement binding were assessed over time by observing the mean levels of complement binding in the population, which are a representation of the overall copy number of complement components per cell. C3 and C5 bound in greater amounts than did MAC and C1. C1 binding was consistently low on serum-resistant strains but was also relatively low on strain Rd compared to the other components. This information, along with the EGTA results, indicates that an another calcium-dependent initiator of the complement cascade is active, or the C1q-antibody complex is the highly reactive initiator of the cascade in this system (at least on strain Rd). Strain Rd accumulated large amounts of C5, larger than those of C3, which is surprising considering the abundance and reactivity of C3 in serum. This could be due to differential shedding of membrane components or possibly higher affinity of the antibodies used for detection of C5 compared to those used for detection of C3. It is unlikely that the washing steps account for this difference, as C3 forms a covalent bond with the bacterial surface whereas C5 does not. One mechanism reported to effect less C3 binding is the expression of fimbriae (also called pili) by H. influenzae (16). In that report a fimbriated Hib strain bound significantly more C3 in a dot blot assay. This mechanism is not likely to operate here, as the strains used in this report are phenotypically afimbriate (strain Ela [25]) or lack a complete fimbrial gene cluster (strains R2866 [unpublished data] and strain Rd [7]).

Another interesting finding was the decrease in cell-associated complement components, namely, C5b and MAC, at the later time points. This was predominant in strain Rd (Fig. 7F, H, and J) and occurred to some extent in strain R2866 (Fig. 7F). Those bacteria on which this phenomenon is occurring are dying or dead, as flow cytometry will not distinguish between intact dead cells and viable cells as long as their sizes remain similar. These data suggest that complement-mediated cell death is not immediately associated with bacteriolysis. Light scatter analysis suggests membrane distortion upon serum exposure; however, it did not correlate with time in serum or cell death. Given the small size of H. influenzae, accurate analysis by light scatter is probably not possible at this time. When Haemophilus is stressed or is dying it sheds its membrane as blebs (20). Membrane blebbing could explain why surface-bound complement levels appear lower on dying cells. The flow cytometer will not detect these blebs as configured for this experiment. Thus, the fluorescence associated with the membrane of serum-sensitive bacteria is lost. This phenomenon was not detected in immunoblotting, where cell-bound complement components increase and remain at maximal levels throughout the course of the analysis. Immunoblotting detects all particles capable of being centrifuged to the bottom of the reaction tube, cells and debris included. In this case it would appear that the shed complement components are present in each dot in the blot. Whether membrane shedding is used as a bacterial defense mechanism is unknown. It is not clear whether some components are shed more readily than others, although it would seem that C5 and MAC have a higher propensity to be shed from the cell than C3. However, the amount of C3 bound to the cell is increased on both unencapsulated strains as determined by immunoblotting, whereas by flow cytometry they are not. This may imply that R2866 can preferentially shed or degrade C3 to prevent C5 and MAC accumulation.

Strategies to avoid the complement cascade have been described for a number of gram-negative organisms, including H. influenzae (10, 12, 14, 20, 22, 24, 29). Capsule-mediated serum resistance is well described for H. influenzae and other species but cannot be used to describe the serum resistance of R2866. Strain R2866 lacks the capsule-specific DNA for type a, b, c, d, e, and f capsules. In addition, its chromosomal DNA does not hybridize with the capsule fragment from pU038. These data and those previously published (21) indicate that strain R2866 does not produce capsular polysaccharide and cannot evade the complement cascade by that mechanism. Surface proteins on some bacteria, such as the porin protein on Neisseria gonorrhoeae, may interfere with the complement cascade by binding inhibitors of the complement cascade normally present in serum, such as factor H (24). Factor H binding was addressed to examine whether it could explain the difference in C3b binding in strains R2866 and Rd. If strain R2866 uses factor H to prevent C3b binding to its cell surface, it should bind factor H early and to a greater extent than strain Rd. Figure 11 shows that factor H binding does occur on Haemophilus but on both strains. Not only is factor H present on both strains, but its binding occurs at similar rates and to similar magnitudes. Flow cytometric analysis of this factor allowed us to reproduce the exact assay for serum killing to determine if factor H binding was different at each time point. Factor H may play a role in reducing C3 binding in both of these strains, but it does not appear to account for the difference in serum resistance in strains R2866 and Rd.

Decoration of LOS with various epitopes that thwart the bactericidal effect of serum is also a well-established mechanism in gram-negative organisms such as Neisseria. Neisseria can decorate its LOS molecules with sialic acid that limits the binding of complement components (22). Recently, sialic acid was reported to play a role in Haemophilus serum resistance (12). We examined Haemophilus survival in 40% serum, but none of the strains studied by Hood et al. (12) showed appreciable survival in 40% serum; they primarily used an assay with 1.25% serum. We also tested the reactivity of a monoclonal antibody (3F11) that recognizes an epitope capable of sialylation in H. influenzae LOS (Michael Apicella, personal communication). This antibody did not react with strain R2866 before or after neuraminidase treatment. Thus, for sialic acid to play a role in strain R2866, it must be in an undescribed configuration.

In H. influenzae the lic locus encodes a choline kinase that appears to influence the levels of ChoP found on bacterial surfaces (29). This locus rapidly turns translation of genes involved in ChoP decoration of LOS on and off, by varying a repeat sequence near its promoter region. Strains that downregulate the lic locus have low levels of ChoP on their surface and are more serum resistant than those with an upregulated lic locus. This change in serum resistance has not been correlated with particular disease isolates but is involved in nasopharyngeal colonization. We have shown by colony blotting (data not shown) and flow cytometry that all of these isolates are decorated with ChoP. Variation in the expression of ChoP in these populations exists; however, our results (with serum depletion of CRP) indicate that differences in ChoP decoration are not responsible for the high-level serum resistance seen in strain R2866.

The difference in complement component accumulation between strain R2866 and the serum-sensitive strain Rd is large. We sought to determine if a global change in LOS or another outer membrane factor contributed to the difference. Since all components seem to be inhibited, it did not seem likely that a specific protein factor was responsible. In other systems protein factors inhibit a particular step that prevents the cascade from progressing to MAC accumulation. Decoration with specific epitopes, as described above, is one method. Others include increasing surface polysaccharide chain length, which either can change outer membrane fluidity, preventing MAC insertion, or can displace the site of MAC formation away from the outer membrane (13). Haemophilus, like Neisseria, does not have long O-polysaccharide side chains like the enteric bacteria and thus does not use these shielding mechanisms.

Serum resistance has also been attributed to another group of invasive nontypeable Haemophilus strains. The Brazilian purpuric fever (BPF) strains were shown to be more serum resistant than non-BPF clone strains of Haemophilus aegyptius (23). That study also concluded that the classical arm of the complement cascade was responsible for initiation of the bactericidal mechanism, but the authors did not present data to explain the difference between their isolates. They also showed that C3 from mouse serum bound both isolates, but they did not mention a difference in the level of binding or if it occurred in a kinetic fashion that could explain a difference in serum resistance as we have done. In fact, the BPF strains may share a common mechanism of serum resistance with strain R2866; however, a controlled experiment comparing both strains in identical assays should be done. A shared mechanism would imply an interesting relationship between these ecologically isolated species.

We suspect that the eventual death of strain R2866 is initiated by cross-reactive antibodies; thus, the resistance mechanism is likely to be an active process leading to inhibition of immunglobulin binding or complement initiation. Indeed, prolonged exposure to this organism will result in high-titer bactericidal antibodies, as is the case with the authors of this paper. It is likely that our overabundance of strain-specific IgG overcomes the mechanism used to thwart the process in normal adult human sera. However, the corollary lay in children with little exposure to diverse populations of nontypeable Haemophilus. H. influenzae with this unique virulence trait may pose a larger threat to Hib-immunized children in the same fashion that type b strains did for so many years. R2866 was isolated from the blood of an immunocompetent, anatomically intact child immunized with the polyribosylribitol phosphate conjugate vaccine, which cannot offer protection from invasive NTHI. The ability of this nontypeable strain to devise an alternate strategy to become invasive is significant, and further work to define genetic elements responsible for this serum resistance is under way in our lab.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jeffrey Weiser, Department of Microbiology, University of Pennsylvania, for supplying information on ChoP decoration as well as strains M318 and M319 used in this study. We also thank Michael Apicella, University of Iowa, for supplying us with the antibody 3F11 along with information regarding its use to detect sialylation in Haemophilus, and Louise Barnett for assistance with the FACS Vantage.

This work was supported in part by grants from the University of Missouri Research Board and grants AI44002 and T32 AI07276 from the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson P, Johnston R B, Jr, Smith D H. Human serum activities against Hemophilus influenzae, type b. J Clin Invest. 1972;51:31–38. doi: 10.1172/JCI106793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anonymous. Progress toward eliminating Haemophilus influenzae type b disease among infants and children—United States, 1987–1997. JAMA. 1999;281:409–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Apicella M A, Griffiss J M, Schneider H. Isolation and characterization of lipopolysaccharides, lipooligosaccharides, and lipid A. Methods Enzymol. 1994;235:242–252. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)35145-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brophy L N, Kroll J S, Ferguson D J, Moxon E R. Capsulation gene loss and ‘rescue’ mutations during the Cap+ to Cap− transition in Haemophilus influenzae type b. J Gen Microbiol. 1991;137:2571–2576. doi: 10.1099/00221287-137-11-2571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Falla T J, Crook D W, Brophy L N, Maskell D, Kroll J S, Moxon E R. PCR for capsular typing of Haemophilus influenzae. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2382–2386. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.10.2382-2386.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Figueroa J E, Densen P. Infectious diseases associated with complement deficiencies. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1991;4:359–395. doi: 10.1128/cmr.4.3.359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fleischmann R D, Adams M D, White O, Clayton R A, Kirkness E R, Kerlavage A R, Bult C J, Tomb J F, Doughtery B A, Merrick J M, et al. Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Science. 1995;269:496–512. doi: 10.1126/science.7542800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fothergill L D, Wright J. Influenzal meningitis: the relation of age incidence to the bactericidal power of blood against the causal organism. J Immunol. 1933;24:273–284. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foxwell A R, Kyd J M, Cripps A W. Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae: pathogenesis and prevention. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:294–308. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.2.294-308.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoe N P, Nakashima K, Lukomski S, Grigsby D, Liu M, Kordari P, Dou S J, Pan X, Vuopio-Varkila J, Salmelinna S, McGeer A, Low D E, Schwartz B, Schuchat A, Naidich S, DeLorenzo D, Fu Y X, Musser J M. Rapid selection of complement-inhibiting protein variants in group A Streptococcus epidemic waves. Nat Med. 1999;5:924–929. doi: 10.1038/11369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hol C, Verduin C M, Van Dijke E, Verhoef J, Fleer A, van Dijk H. Complement resistance is a virulence factor of Branhamella (Morexella) catarrhalis. FEMS Microbiol Immunol. 1995;11:207–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1995.tb00118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hood D W, Makepeace K, Deadman M E, Rest R F, Thibault P, Martin A, Richards J C, Moxon E R. Sialic acid in the lipopolysaccharide of Haemophilus influenzae: strain distribution, influence on serum resistance and structural characterization. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:679–692. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joiner K A. Studies on the mechanism of bacterial resistance to complement-mediated killing on the mechanism of action of bactericidal antibody. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1985;121:99–133. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-45604-6_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joiner K A. Complement evasion by bacteria and parasites. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1988;42:201–230. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.42.100188.001221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Michaelka J, Goodgal S H. Genetic and physical map of the chromosome of Hemophilus influenzae. J Mol Biol. 1969;28:407–421. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(69)90115-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miyazaki S, Masumoto T, Furuya N, Tateda K, Yamaguchi K. The pathogenic role of fimbriae of Haemophilus influenzae type b in murine bacteraemia and meningitis. J Med Microbiol. 1999;48:383–388. doi: 10.1099/00222615-48-4-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Musher D M, Goree A, Baughn R E, Birdsall H H. Immunoglobulin A from bronchopulmonary secretions blocks bactericidal and opsonizing effects of antibody to nontypable Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 1984;45:36–40. doi: 10.1128/iai.45.1.36-40.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Musher D M, Hague-Park M, Baughn R E, Wallace R J, Jr, Cowley B. Opsonizing and bactericidal effects of normal human serum on nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 1983;39:297–304. doi: 10.1128/iai.39.1.297-304.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Musser J M, Barenkamp S J, Granoff D M, Selander R K. Genetic relationships of serologically nontypeable and serotype b strains of Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 1986;52:183–191. doi: 10.1128/iai.52.1.183-191.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mustafa M M, Ramilo O, Syrogiannopoulos G A, Olsen K D, McCracken G H, Jr, Hansen E J. Induction of meningeal inflammation by outer membrane vesicles of Haemophilus influenzae type b. J Infect Dis. 1989;159:917–922. doi: 10.1093/infdis/159.5.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nizet V, Colina K F, Almquist J R, Reubens C E, Smith A L. A virulent nonencapsulated Haemophilus influenzae. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:180–186. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.1.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parsons N J, Andrade J R, Patel P V, Cole J A, Smith H. Sialylation of lipopolysaccharide and loss of absorption of bactericidal antibody during conversion of gonococci to serum resistance by cytidine 5′-monophospho-N-acetyl neuraminic acid. Microb Pathog. 1989;7:63–72. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(89)90112-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Porto M H, Noel G J, Edelson P J The Brazilian Purpuric Fever Study Group. Resistance to serum bactericidal activity distinguishes Brazilian purpuric fever (BPF) case strains of Haemophilus influenzae biogroup Aegyptius (H. aegyptius) from non-BPF Strains. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:792–794. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.4.792-794.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ram S, McQuillen D P, Gulati S, Elkins C, Pangburn M K, Rice P A. Binding of complement factor H to loop 5 of porin protein 1A: a molecular mechanism of serum resistance of nonsialylated Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Exp Med. 1998;188:671–680. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.4.671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith A L, Smith D H, Averill D R, Jr, Marino J, Moxon E R. Production of Haemophilus influenzae b meningitis in infant rats by intraperitoneal inoculation. Infect Immun. 1973;8:278–290. doi: 10.1128/iai.8.2.278-290.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Snyderman R, Pike M C. Interaction of complex polysaccharides with the complement system: effect of calcium depletion on terminal component consumption. Infect Immun. 1975;11:273–279. doi: 10.1128/iai.11.2.273-279.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomas J C, Desrosiers M, St.-Pierre Y, Lirette P, Bisaillon J G, Beudet R, Villemur R. Quantitative flow cytometric detection of specific microorganisms in soil samples using rRNA targeted fluorescent probes and ethidium bromide. Cytometry. 1997;27:224–232. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0320(19970301)27:3<224::aid-cyto3>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsai C M, Frasch C E. A sensitive silver stain for detecting lipopolysaccharides in polyacrylamide gels. Anal Biochem. 1982;119:115–119. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(82)90673-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weiser J N, Pan N, McGowan K L, Musher D, Martin A, Richards J. Phosphorylcholine in the lipopolysaccharide of Haemophilus influenzae contributes to persistence in the respiratory tract and sensitivity to serum killing mediated by C-reactive protein. J Exp Med. 1998;187:631–640. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.4.631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]