Abstract

The reactivity of alkali–manganese(II) and alkali trifluoroacetates towards amorphous SiO2 (a-SiO2) was studied in the solid-state. K4Mn2(tfa)8, Cs3Mn2(tfa)7(tfaH), KH(tfa)2, and CsH(tfa)2 (tfa = CF3COO−) were thermally decomposed under vacuum in fused quartz tubes. Three new bimetallic fluorotrifluoroacetates of formulas K4Mn3(tfa)9F, Cs4Mn3(tfa)9F, and K2Mn(tfa)3F were discovered upon thermolysis at 175 °C. K4Mn3(tfa)9F and Cs4Mn3(tfa)9F feature a triangular-bridged metal cluster of formula [Mn3(μ3-F)(μ2-tfa)6(tfa)3]4−. In the case of K2Mn(tfa)3F, fluoride serves as an inverse coordination center for the tetrahedral metal cluster K2Mn2(μ4-F). Fluorotrifluoroacetates may be regarded as intermediates in the transformation of bimetallic trifluoroacetates to fluoroperovskites KMnF3, CsMnF3, and Cs2MnF4, which crystallized between 250 and 600 °C. Decomposition of these trifluoroacetates also yielded alkali hexafluorosilicates K2SiF6 and Cs2SiF6 as a result of the fluorination of fused quartz. The ability to fluorinate fused quartz was observed for monometallic alkali trifluoroacetates as well. Hexafluorosilicates and heptafluorosilicates K3SiF7 and Cs3SiF7 were obtained upon thermolysis of KH(tfa)2 and CsH(tfa)2 between 200 and 400 °C. This ability was exploited to synthesize fluorosilicates under air by simply reacting alkali trifluoroacetates with a-SiO2 powder.

Graphical Abstract

The reactivity of alkali–manganese(II) and alkali trifluoroacetates towards amorphous SiO2 was studied in the solid-state with an eye towards the synthesis of alkali fluorosilicates.

Introduction

For a number of years our group has been working on the synthesis, crystal-chemistry, and reactivity of bimetallic trifluoroacetates.1–5 We have established that the trifluoroacetato ligand (tfa = CF3COO−) can bridge atoms with dissimilar electronic and geometric requirements and that this ability can be exploited to synthesize bimetallic trifluoroacetates featuring alkali–manganese(II),1, 5 alkaline-earth–manganese(II),2 and alkali–alkaline-earth pairs.4 K2Mn2(tfa)6(tfaH)2(H2O), CsMn(tfa)3, K2Mn(tfa)4, Cs3Mn2(tfa)7(tfaH), Ca3–xMnx(tfa)6(H2O)4, and RbCa(tfa)3 are some examples of this family of solid-state materials. These solids can be prepared as single-phase polycrystalline materials, which is advantageous to establish reactivity patterns. On this basis, we have extensively studied the thermal decomposition of bimetallic trifluoroacetates under inert atmosphere. Taking K2Mn2(tfa)6(tfaH)2(H2O) and CsMn(tfa)3 as examples, we have demonstrated that these solids serve as self-fluorinating single-source precursors to the corresponding fluoroperovskites KMnF3 and CsMnF3.1 Likewise, thermolysis of K2Mn(tfa)4 and Cs3Mn2(tfa)7(tfaH) provides synthetic access to layered fluoroperovskites K2MnF4 and Cs2MnF4, respectively.5

More recently, we began studying the thermal decomposition of bimetallic trifluoroacetates in fused quartz sealed tubes. Our main goal was to probe the ability of these solids to fluorinate amorphous SiO2 (a-SiO2), which could eventually open up a new solid-state route to ternary and quaternary fluorosilicates. Additionally, we sought to capture decomposition transients to shed light on the transformation of an organic–inorganic hybrid into a fully inorganic solid. Results from these studies are presented herein in two distinct sections. The first section is devoted to the thermolysis of bimetallic trifluoroacetates K2Mn(tfa)4 and Cs3Mn2(tfa)7(tfaH) in the 175–600 °C temperature range. Single-crystal and powder X-ray diffraction were used to identify thermal decomposition products; hexafluorosilicates K2SiF6 and Cs2SiF6 were among these products. This observation prompted us to investigate the reactivity of alkali trifluoroacetates KH(tfa)2 and CsH(tfa)2 towards a-SiO2. We were motivated by the fact that, although alkali trifluoroacetates have been used as trifluoromethylating agents,6–10 they have not been considered as reagents for the solid-state synthesis of fluorosilicates. Fluorosilicates M2SiF6 (M = Li–Cs) and M′3SiF7 (M′ = K–Cs) are extensively used as hosts for Mn4+ downconverting red phosphors.11–19 Typically, these materials are synthesized through solution-phase routes that use aqueous HF as the fluorine source;20 alternatively, HF is generated in situ by dissolving MHF2 in H3PO421 or NH4F in HCl.15, 22 In either approach, the presence of HF imposes stringent requirements to synthetic procedures and equipment. Thus, the second section of this article focuses on probing the reactivity of KH(tfa)2 and CsH(tfa)2 towards a-SiO2; specifically, on their ability to act as mild fluorinating agents. KH(tfa)2 and CsH(tfa)2 were decomposed in fused quartz tubes at temperatures ranging between 200 and 400 °C. Thermolysis experiments were also carried out under air in the presence of commercially available a-SiO2 powder. Powder X-ray diffraction was used to identify decomposition products. Results presented in this article are discussed from the standpoint of streamlining the solid-state synthesis of fluorosilicates.

Experimental

Synthesis of Bi- and Monometallic Trifluoroacetates.

All experiments were carried out under nitrogen atmosphere using standard Schlenk techniques. K2CO3 (99%), Cs2CO3 (99.9%), MnCO3 (99.9%), amorphous SiO2 (99.8%, surface area 175–225 m2 g−1), and anhydrous CF3COOH (99%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used as received. Double-distilled water was used throughout. Polycrystalline bi- and monometallic trifluoroacetates were synthesized via solvent evaporation.5, 23 The procedure for the preparation of phase-pure K4Mn2(tfa)8 and Cs3Mn2(tfa)7(tfaH) is described in detail elsewhere.5 Monometallic trifluoroacetates KH(tfa)2 and CsH(tfa)2 were synthesized by dissolving the corresponding metal carbonate (1 mmol) in a mixture of 3 mL of tfaH and 3 mL of double-distilled water in a 50 mL two-neck round-bottom flask. A colorless transparent solution was thus obtained. The flask containing the reaction mixture was immersed in a sand bath and solvent evaporation took place at 65 °C for 48 h under a constant flow of dry nitrogen (140 mL min−1). The resulting white solids were stored in a nitrogen-filled glove box.

Thermal Decomposition of Trifluoroacetates.

Thermolysis of trifluoroacetates was carried out in three different experimental configurations; these are depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Experimental configurations used for thermolysis of bi- and monometallic trifluoroacetates. The tube furnace is 22 × 1′′ (length × diameter). The chamber of the box furnace is 4 × 5 × 7′′ (width × length × depth).

Setup I.

Bimetallic (≈70–80 mg) and monometallic trifluoroacetates (≈120–150 mg) were first decomposed in setup I (Figure 1a). Polycrystalline samples were loaded into a fused quartz tube (length ≈120 mm, outer diameter ≈10 mm, wall thickness ≈1.0 mm). The tube was sealed under vacuum (≈45–60 mTorr), placed in a tube furnace at 100 °C, heated to a predefined target temperature (175–600 °C), and allowed to dwell at that temperature for a given time (2–12 h). A heating rate of 150 °C h−1 was employed in all cases except in experiments conducted at 175 °C, which were aimed at isolating single crystals of decomposition intermediates; in those experiments the heating rate was set to 6 °C h−1. Once the dwelling time was completed, the furnace was allowed to cool to 100 °C, the quartz tube was opened under air, and products were stored in a nitrogen-filled glove box. Off-white to brown powders were obtained.

Setup II.

Bimetallic trifluoroacetates (≈70–80 mg) were decomposed in setup II (Figure 1b). This experimental configuration differs from setup I in that the trifluoroacetate sample is not in direct contact with fused quartz. Polycrystalline samples were loaded into a closed-one-end alumina tube (length ≈70 mm, outer diameter ≈6.4 mm, wall thickness ≈1.0 mm). This tube was placed within a second alumina tube (length ≈70 mm, outer diameter ≈8.5 mm, wall thickness ≈1.0 mm). The open end of the tube containing the sample faced the closed end of the wider tube. Ceramic wool was used to fill the gap between the closed end of the tube containing the sample and the open end of the wider tube (≈2 mm). The whole assembly was placed in a fused quartz tube (length ≈120 mm, outer diameter ≈10 mm, wall thickness ≈1.0 mm) and sealed under vacuum (≈45–60 mTorr). Thermolysis was then carried out as in setup I. Off-white to brown powders were obtained.

Setup III.

Monometallic trifluoroacetates were decomposed in setup III (Figure 1c). This experimental configuration differs from setups I and II in that (i) trifluoroacetates are decomposed in the presence of amorphous SiO2 (alkali:Si molar ratio = 2:1), and (ii) thermolysis is carried out under air. KH(tfa)2:a-SiO2 (≈100 mg) and CsH(tfa)2:a-SiO2 (≈160 mg) mixtures were prepared in a nitrogen-filled glove box. These were transferred to 5 mL alumina crucibles, which were subsequently covered with alumina disks. Crucibles were placed in a box furnace at 100 °C, heated to a predefined target temperature (300–400 °C), and allowed to dwell at that temperature for a given time (6–12 h). A heating rate of 10 °C min−1 was employed in all experiments. Once the dwelling time was completed, the furnace was allowed to cool to 100 °C and crucibles were removed from the furnace. Ash grey powders were obtained. Dwelling temperatures were selected based on thermal analyses conducted under inert atmosphere which showed that K4Mn2(tfa)8 and Cs3Mn2(tfa)7(tfaH) decompose between 150 and 275 °C (see Figure S1 in the ESI and Figure 4 in reference 5). In the case of KH(tfa)2 and CsH(tfa)2, decomposition has been shown to take place between 150 and 250 °C.24, 25

Single-Crystal X-ray Diffraction (SCXRD).

SCXRD analysis was carried out to establish the crystal structures of intermediates formed upon thermolysis of K4Mn2(tfa)8 and Cs3Mn2(tfa)7(tfaH) at 175 °C in setups I and II. Colorless crystals of K4Mn3(tfa)9F (0.48 × 0.32 × 0.25 mm), Cs4Mn3(tfa)9F (0.05 × 0.05 × 0.02 mm), and K2Mn(tfa)3F (0.21 × 0.11 × 0.11 mm) were selected for structure determination and mounted in Paratone N oil. Diffraction data were collected using a Bruker X8 Apex diffractometer. X-ray intensities were measured at 100 K using Mo Kα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å). Frames were integrated using Bruker SAINT. Experimental data were corrected for Lorentz, polarization, and absorption effects; for the latter, the multiscan method was employed using Bruker SADABS.26 Structure solution was accomplished using a dual-space approach as implemented in SHELXT27 and difference Fourier maps as embedded in SHELXL-2014/728 running under ShelXle.29 VESTA was used to visualize crystal structures.30 Table 1 summarizes crystal data for K4Mn3(tfa)9F and K2Mn(tfa)3F. Cs4Mn3(tfa)9F was found to be isostructural to its potassium counterpart, except for positional disorder of some cesium atoms and trifluoroacetate ligands. Full details on data collection and structure refinement are given in the ESI (Tables S1–S10 and Figures S2–S4). Crystal data were deposited in the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre with numbers 2184179 (K4Mn3(tfa)9F), 2201197 (Cs4Mn3(tfa)9F), and 2184129 (K2Mn(tfa)3F).

Table 1.

Crystal and Structural Determination Data of K4Mn3(tfa)9F and K2Mn(tfa)3F

| Chemical formula | K4Mn3(tfa)9F | K2Mn(tfa)3F |

| Formula weight (g) | 1357.47 | 491.20 |

| Crystal system | Monoclinic | Orthorhombic |

| Space group | P21/n | Pbcn |

| a, b, c (Å) | 17.5481 (9), 13.7303 (7), 19.5024 (9) | 12.4013 (10), 14.4480 (12), 7.3981 (6) |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 109.993 (2), 90 | 90, 90, 90 |

| Volume (Å3) | 4415.7 (4) | 1325.55 (19) |

| Z | 4 | 4 |

| R[F2 > 2σ(F2)] | 3.5% | 10.3% |

| wR(F2) | 7.7% | 25.2% |

| S | 1.01 | 1.27 |

Powder X-ray Diffraction (PXRD).

Powder XRD patterns were collected using a Bruker D2Phaser diffractometer operated at 30 kV and 10 mA. Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å) was employed. A nickel filter was used to remove Cu Kβ. Diffractograms were collected in the 10−60° 2θ range using a step size of 0.012° and a step time of 0.4 s, unless otherwise noted.

Results and Discussion

Section I. Reactivity of Bimetallic Trifluoroacetates K4Mn2(tfa)8 and Cs3Mn2(tfa)7(tfaH).

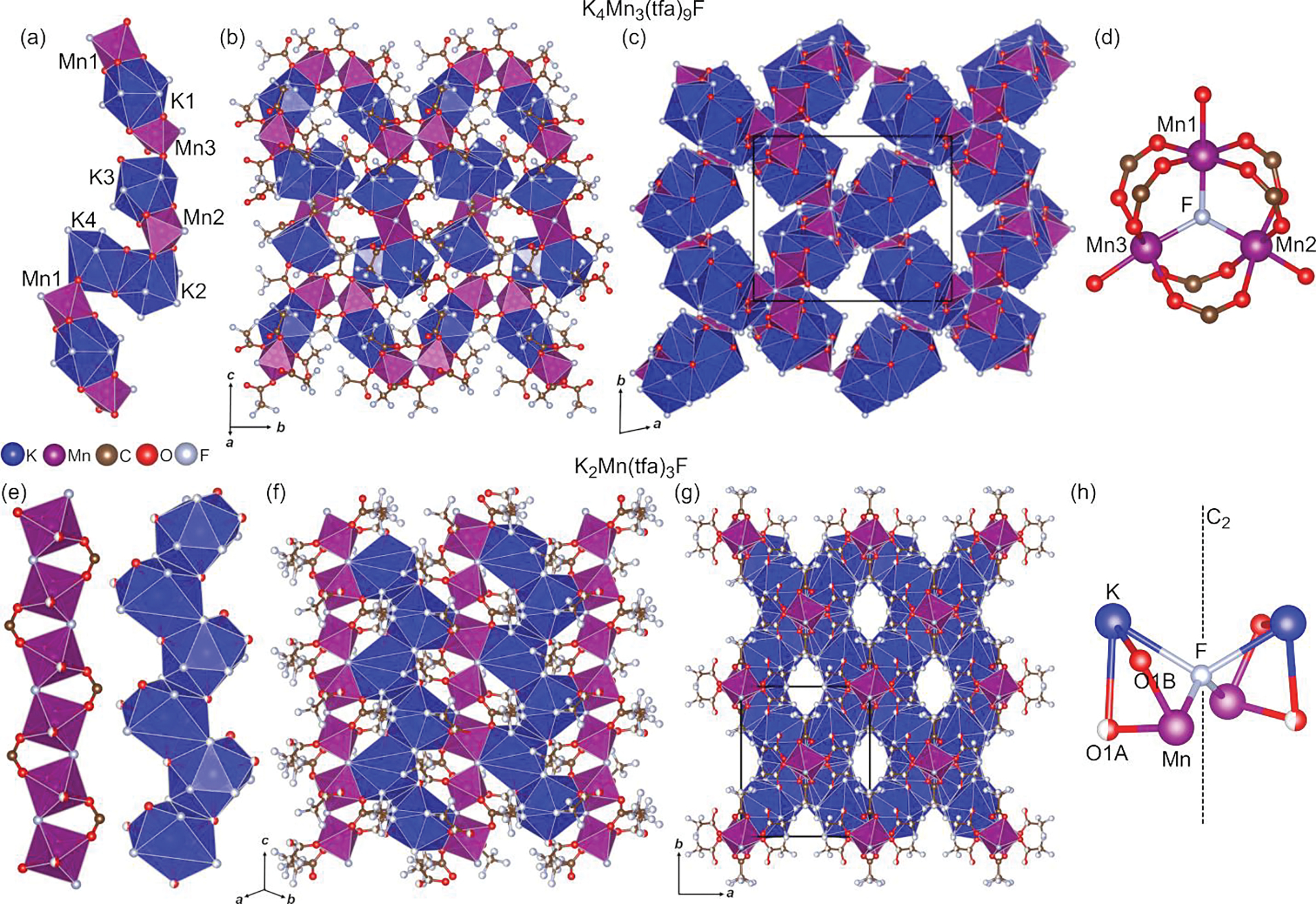

Bimetallic trifluoroacetates K4Mn2(tfa)8 and Cs3Mn2(tfa)7(tfaH) were thermally decomposed at 175, 250, 450, and 600 °C for 2 h in setups I and II. Crystalline phases obtained after each thermolysis experiment are summarized in Table 2. We begin our discussion of these results with the crystal structures of K4Mn3(tfa)9F and K2Mn(tfa)3F, which were obtained at 175 °C in setups I and II, respectively. Crystal structures are shown in Figure 2. K4Mn3(tfa)9F crystallizes in the monoclinic P21/n space group and its building block consists of chains featuring corner-, edge-, and face-sharing MnO5F and K(O,F)10,11 polyhedra (Figure 2a). These chains run along the c axis and form layers that extend in the bc plane (Figure 2b). Stacking these layers along the a axis results in the observed three-dimensional structure in which each chain is connected to three adjacent chains (Figure 2c). An interesting structural feature of K4Mn3(tfa)9F is the presence of a triangular-bridged cluster of Mn2+ cations that may be described as [Mn3(μ3-F)(μ2-tfa)6(tfa)3]4− (Figure 2d). A fluoride ion connects three MnO5F octahedra by bridging Mn2+ in a trigonal planar geometry (∠Mn1–μ3-F–Mn2 = 119.2°, ∠Mn2–μ3-F–Mn3 = 122.1°, ∠Mn3–μ3-F–Mn1 = 118.7°, Mn–F = 2.11–2.13 Å). Six trifluoroacetato ligands sitting above and below the plane of the Mn3(μ3-F) core bridge metal ions in pairs. The remaining three trifluoroacetato ligands complete the coordination sphere of manganese. The [Mn3(μ3-F)(μ2-tfa)6(tfa)3]4− cluster was also encountered in fluorotrifluoroacetates Cs4Mn3(tfa)9F and Na4Mn3(tfa)9F, which are isostructural to K4Mn3(tfa)9F. Cs4Mn3(tfa)9F was obtained upon thermal decomposition of Cs3Mn2(tfa)7(tfaH) at 175 °C. Na4Mn3(tfa)9F was synthesized in the course of exploratory thermolysis experiments conducted using a bimetallic sodium manganese trifluoroacetate previously reported by our group (see ESI, Tables S11–S14 and Figure S5).1 It is worth mentioning that triangular-bridged clusters of formula M3(μ3-F)(tfa)6L3 (M = Mg, Fe, Mn, Co, Ni, Zn; L = tfa, tfaH, OCH3, py, H2O) have been observed in fluorotrifluoroacetate crystals grown from solution at room temperature.31–35 Altogether, these observations point to the relevance of these clusters as building blocks. Further, the fact that they are encountered both at room temperature and at 175 °C suggests their potential as synthons for the preparation of organic–inorganic hybrid materials. Another structurally interesting hybrid of formula K2Mn(tfa)3F was discovered upon thermolysis of K4Mn2(tfa)8 at 175 °C in setup II. K2Mn(tfa)3F crystallizes in the orthorhombic Pbcn space group and can be visualized as chains built of corner-sharing MnO4F2 octahedra and edge-sharing K(O,F)12 polyhedra (Figure 2e). These chains run along the c axis and are connected to each other through face-sharing polyhedra (Figure 2f). This connectivity results in layers that extend in the (110) and (10) planes. The observed three-dimensional structure of the hybrid results from the assembly of these two sets of layers (Figure 2g). Void channels that run parallel to the c axis are observed in K2Mn(tfa)3F; the presence of micropores in mono- and bimetallic haloacetates is not uncommon.1, 23, 36, 37 An unusual structural motif we observe in K2Mn(tfa)3F is a K2Mn2(μ4-F) cluster in which fluoride bridges two K+ and two Mn2+ cations (Figure 2h). The bridging fluoride sits on a C2 axis and the four metal ions are arranged in a highly distorted tetrahedral geometry (∠K–μ4-F–K = 116.9°, ∠Mn–μ4-F–Mn = 121.0°, ∠K–μ4-F–Mn = 94.1°, K–F = 2.72 Å, Mn–F = 2.13 Å). Although μ4-F is known to serve as an inverse coordination center in tetrahedral metal–organic complexes,38 a comprehensive search shows that fluorotrifluoroacetates featuring μ4-F metal clusters have not been reported neither in the literature nor in the Cambridge Structural Database. Attempts to isolate Cs2Mn(tfa)3F by decomposing Cs3Mn2(tfa)7(tfaH) in setup II were unsuccessful; Cs4Mn3(tfa)9F was invariably obtained.

Table 2.

Crystalline Products of the Solid-State Thermolysis of Bimetallic Trifluoroacetates

| Precursor | Setup | Dwelling Temperature and Time | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 175 °C, 2 h | 250 °C, 2 h | 450 °C, 2 h | 600 °C, 2 h | ||

| K4Mn2(tfa)8 | I | K4Mn3(tfa)9F | KMnF3 | KMnF3 K2SiF6 Unindexed phase(s) |

KMnF3 K2SiF6 |

| II | K2Mn(tfa)3F | KMnF3 | KMnF3 K2SiF6 |

KMnF3 K2SiF6 |

|

| Cs3Mn2(tfa)7(tfaH) | I | Cs4Mn3(tfa)9F | CsMnF3 Cs2MnF4 Cs2SiF6 |

Cs2SiF6 MnF2 |

Cs2SiF6

MnF2 |

| II | Cs4Mn3(tfa)9F | CsMnF3 Cs2MnF4 Cs2SiF6 |

CsMnF3 Cs2SiF6 MnF2 |

CsMnF3 Cs2SiF6 |

|

Figure 2.

Crystal structures of K4Mn3(tfa)9F (a‒d) and K2Mn(tfa)3F (e‒h). Building blocks (a, e), layers (b, f), and extended perspectives (c, g) are shown for each structure. (d) and (h) depict the coordination of bridging atoms μ3-F and μ4-F, respectively. Atom splitting in disordered positions is omitted for clarity; only major occupancy sites are shown. Unit cells in (c) and (g) are depicted with solid black lines. Only the polyhedral framework is shown in (c).

As shown in Table 2 and as it will be discussed below, thermolysis of K4Mn2(tfa)8 and Cs3Mn2(tfa)7(tfaH) at or above 250 °C led to the formation of fluoroperovskite phases KMnF3, CsMnF3, and Cs2MnF4. Fluorotrifluoroacetates K4Mn3(tfa)9F, Cs4Mn3(tfa)9F, and K2Mn(tfa)3F isolated at 175 °C could therefore be regarded as intermediates in the transformation of bimetallic trifluoroacetates to fluoroperovskites. This conjecture results from compositional and structural considerations. From a compositional standpoint, organooxygen (from carboxylate groups) and organofluorine (from trifluoromethyl groups) are partially displaced from the coordination sphere of metal atoms upon going from trifluoroacetates to fluorotrifluoroacetates. As an example, manganese atoms in K4Mn2(tfa)8 are solely coordinated by organooxygen.5 By contrast, MnO5F and MnO4F2 octahedra present in K4Mn3(tfa)9F and K2Mn(tfa)3F, respectively, feature organooxygen and fluoride as ligands. The stepwise replacement of trifluoroacetato ligands by fluoride anions has been observed in the thermolysis of Fe(tfa)3.39 From a structural standpoint, the connectivity of metal atoms in K4Mn3(tfa)9F and K2Mn(tfa)3F may be regarded as intermediate between that observed in bimetallic trifluoroacetates and fluoroperovskites. For clarity, the crystal structure of cubic KMnF3 is shown in Figure 3. Continuing with the example of manganese atoms, no Mn–organofluorine–Mn bridges are present in K4Mn2(tfa)8.5 However, Mn–fluoride–Mn bridges are encountered in K4Mn3(tfa)9F and K2Mn(tfa)3F; these bridges build the framework of MnF6 octahedra in KMnF3 (Figure 3a). Additionally, K–fluoride–K and K–fluoride–Mn bridges are observed in the case of K2Mn(tfa)3F; such bridges are present in KMnF3. From this perspective, the presence of a K2Mn2(μ4-F) cluster in K2Mn(tfa)3F may be visualized as an intermediate towards the formation of the K4Mn2(μ6-F) core in KMnF3 (Figure 3b). Similar compositional and structural relationships can be established between Cs3Mn2(tfa)7(tfaH), Cs4Mn3(tfa)9F, hexagonal CsMnF3, and tetragonal Cs2MnF4.

Figure 3.

Crystal structure of cubic KMnF3. Unit cell (a) and local coordination of the μ6-F atom (b) are shown.

K4Mn2(tfa)8 and Cs3Mn2(tfa)7(tfaH) were also decomposed at 250, 450, and 600 °C for 2 h in setups I and II. PXRD patterns of the decomposition products are given in Figures 4 and 5. Thermolysis of K4Mn2(tfa)8 at 250 °C in setup I led to cubic KMnF3 (PDF No. 01-073-9430) as the sole crystalline product (Figure 4a). The formation of K2SiF6 (PDF No. 01-075-0694) was observed upon increasing the decomposition temperature to 450 °C while keeping the dwelling time constant. Under these conditions, KMnF3 and K2SiF6 coexisted with one or multiple crystalline phases (X) whose diffraction maxima could not be indexed (Figure 4b). Finally, only KMnF3 and K2SiF6 were identified as crystalline products upon thermolysis at 600 °C (Figure 4c). Similar results were obtained in setup II except that (i) no crystalline phases other than KMnF3 and K2SiF6 were observed at 450 °C, and (ii) the fraction of K2SiF6 relative to KMnF3 at 600 °C was significantly lower than that observed in setup I (Figure 4d–f). In the case of Cs3Mn2(tfa)7(tfaH), CsMnF3 (PDF No. 01-075-2034), Cs2MnF4, and Cs2SiF6 (PDF No. 01-073-6564) were observed as crystalline products upon decomposition at 250 °C in setup I (Figure 5a). A tentative crystal structure of layered perovskite Cs2MnF4 was proposed by us in a recent article;5 the corresponding reflection list is given in the ESI (Table S15). The hygroscopic nature of this phase complicated collection and indexing of diffraction data;5 as a result, the presence of trace amounts of additional phases cannot be discarded. Increasing the decomposition temperature from 250 to 450 °C while keeping the dwelling time constant yielded Cs2SiF6 and MnF2 (PDF No. 01-070-2499) as products (Figure 5b); CsMnF3 was not observed under these conditions. Further increasing the temperature to 600 °C did not result in significant changes (Figure 5c). Similar results were obtained at 250 and 450 °C in setup II, except that for the latter temperature a very small fraction of hexagonal CsMnF3 coexisted with Cs2SiF6 and MnF2 (Figure 5d and 5e). At 600 °C, by contrast, hexagonal CsMnF3 was the major phase and coexisted with a minor fraction of Cs2SiF6; no MnF2 was observed under these conditions (Figure 5f). As mentioned in the Introduction, our goal was to establish reactivity patterns towards a-SiO2. Results presented in this paragraph, however, provide a starting point to formulate some hypotheses for future mechanistic studies aimed at elucidating fluorinating species, reaction pathways, and transients. The formation of alkali hexafluorosilicates was observed for both compounds and in both setups, implying that byproducts from trifluoroacetate thermolysis reacted with the quartz tube (or with the ceramic wool, which contains a-SiO2) to form a silicon-containing gas such as SiF4. Two pathways may be envisioned for the formation of this species. The first pathway involves fluorination of a-SiO2 by difluorocarbene (equation (1));40, 41 CF2 has been proposed as a byproduct of trifluoroacetate thermolysis.4, 42, 43 The second pathway involves etching of a-SiO2 by gaseous hydrogen fluoride (equation (2)).44, 45 HF may be formed upon hydrolysis of trifluoroacetic anhydride.

| (1) |

| (2) |

(CF3CO)2O has been identified as a byproduct of trifluoroacetate thermolysis4, 43, 46–48 and the presence of residual water cannot be ruled out under our experimental conditions. Both fluorination pathways may be operating if water is present since hydrolysis of (CF3CO)2O leads to the formation of trifluoroacetic acid which in turns produces difluorocarbene.44, 45 Another result that deserves further investigation is whether alkali hexafluorosilicates form through reaction of fluoroperovskites with SiF4. The presence of MnF2 following the decomposition of Cs3Mn2(tfa)7(tfaH) suggests this reaction may be

| (3) |

occurring (equation (3)). At the same time, the fact that MnF2 was not detected in the decomposition of K4Mn2(tfa)8 raises the question of the dependence of the mechanism by which alkali hexafluorosilicates form on the alkali metal. Hypotheses regarding reaction pathways and transients should be considered with the caveat that decomposition reactions were not sequential because reaction mixtures were allowed to dwell for 2 h at each temperature. Future mechanistic studies should obviously employ a different experimental design.

Figure 4.

PXRD patterns of the products resulting from thermolysis of bimetallic trifluoroacetate K4Mn2(tfa)8 in setups I (a‒c) and II (d‒f) at three different temperatures.

Figure 5.

PXRD patterns of the products resulting from thermolysis of bimetallic trifluoroacetate Cs3Mn2(tfa)7(tfaH) in setups I (a‒c) and II (d‒f) at three different temperatures. Patterns shown in (a) and (d) were collected with a step time of 1.4 s.

Section II. Reactivity of Monometallic Trifluoroacetates KH(tfa)2 and CsH(tfa)2.

The observation that bimetallic trifluoroacetates reacted with the quartz tube prompted us to investigate the reactivity of monometallic alkali trifluoroacetates KH(tfa)2 and CsH(tfa)2 towards a-SiO2. Specifically, we were interested in establishing whether these solids could be used as reagents for the solid-state synthesis of fluorosilicates. KH(tfa)2 and CsH(tfa)2 crystallize in the monoclinic space group C2/c and are isostructural (see ESI, Tables S16–S19 and Figures S6 and S7).49 These solids were decomposed in setups I and III to probe their reactivity towards a-SiO2 first in vacuum and then under air. Thermal decomposition was carried out at temperatures between 200 and 400 °C for 6 to 12 h. Crystalline phases obtained after each thermolysis experiment are summarized in Table 3. PXRD patterns of the decomposition products are given in Figure 6. Owing to the hygroscopic nature of some of the products, diffraction patterns were collected immediately after opening the quartz tube (setup I) or after removing the alumina crucible from the box furnace (setup III), unless noted otherwise. Thermolysis of KH(tfa)2 at 200 °C for 12 h in a sealed quartz tube resulted in the formation of K2SiF6 (PDF No. 01-075-0694) as the sole crystalline product (Figure 6a). Increasing the decomposition temperature to 300 °C led to the appearance of K3SiF7 (PDF No. 01-073-1396); at 400 °C, this was the only crystalline phase observed. As expected, increasing temperature stabilized K3SiF7 relative to K2SiF6.50–52 Analysis of the decomposition products of CsH(tfa)2 was significantly more challenging due to the extremely hygroscopic nature of Cs3SiF7.53 Unlike K3SiF7, which decomposed after several hours under our experimental conditions (≈20–25% relative humidity), Cs3SiF7 decomposed within minutes. X-ray analysis of the products resulting from thermolysis of CsH(tfa)2 at 200 °C for 6 h was not possible because the powder turned into a liquid right after opening the quartz tube. Increasing the decomposition temperature to 300 °C allowed us to observe the coexistence of Cs2SiF6 (PDF No. 01-073-6564) and Cs3SiF7 (PDF No. 01-071-0997, Figure 6b). Collection of a diffraction pattern of the same sample after 30 min of air exposure showed that Cs3SiF7 had already decomposed, leaving Cs2SiF6 as the only crystalline phase. Only maxima arising from Cs2SiF6 were observed in the products obtained upon thermolysis at 400 °C. Altogether, results from thermolysis experiments conducted in setup I established the ability of KH(tfa)2 and CsH(tfa)2 to fluorinate quartz under vacuum and yield ternary fluorosilicates. We then decided to probe whether this reactivity pattern was maintained under air. To this end, mixtures of KH(tfa)2:a-SiO2 and CsH(tfa)2:a-SiO2 (2:1 molar ratio) were decomposed in setup III. Thermolysis of KH(tfa)2 was carried out at 300 and 400 °C for 12 h. Both K2SiF6 and K3SiF7 could be accessed in this temperature range (Figure 6c). CsH(tfa)2 was decomposed at 400 °C for 6 h in an attempt to obtain phase pure Cs2SiF6. However, a mixture of Cs2SiF6 and Cs3SiF7 was obtained (Figure 6d); as expected, the latter phase decomposed within minutes. The most significant outcome of these experiments was that alkali trifluoroacetates were able to fluorinate a-SiO2 in an experimental setup similar to that used for routine solid-state reactions. Further, control experiments performed in setup III using KF as a reagent showed that no reaction occurred with a-SiO2 (see ESI, Figure S8a). Likewise, CsF was much less reactive towards a-SiO2 than its trifluoroacetate counterpart (see ESI, Figure S8b), demonstrating that the strong fluorinating ability of KH(tfa)2 and CsH(tfa)2 stems from the trifluoroacetato ligands. This distinct reactivity of alkali trifluoroacetates could be exploited to design all-solid-state routes to alkali fluorosilicates as an alternative to currently used solution-based syntheses, which typically entail using aqueous HF.20, 54 Tuning the stoichiometry of the reaction mixture and reaction conditions (mass, heating rate, and dwelling temperature and time) should enable the preparation of single-phase fluorosilicates using trifluoroacetates as a metal and fluorine source.

Table 3.

Crystalline Products of the Solid-State Thermolysis of Monometallic Trifluoroacetatesa

| Precursor | Setup | Dwelling Temperature and Time | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 200 °C, 12 h | 300 °C, 12 h | 400 °C, 12 h | ||

| KH(tfa)2 | I | K2SiF6 |

K2SiF6 K3SiF7 |

K3SiF7 |

| III | K2SiF6 K3SiF7 |

K2SiF6 K3SiF7 |

||

| CsH(tfa)2 | I | 300 °C, 6 h | 400 °C, 6 h | |

| Cs2SiF6 Cs3SiF7 |

Cs2SiF6 | |||

| III | Cs2SiF6 Cs3SiF7 |

|||

Under a relative humidity of 20–25%.

Figure 6.

PXRD patterns of the products resulting from thermolysis of monometallic trifluoroacetates KH(tfa)2 and CsH(tfa)2 in setups I (a, b) and III (c, d).

Conclusions

The reactivity of alkali–manganese(II) and alkali trifluoroacetates towards a-SiO2 was probed in a number of experimental configurations. Three new bimetallic fluorotrifluoroacetates were discovered upon thermolysis of K4Mn2(tfa)8 and Cs3Mn2(tfa)7(tfaH) under vacuum. K4Mn3(tfa)9F, Cs4Mn3(tfa)9F, and K2Mn(tfa)3F may be regarded as intermediates in the transformation of the bimetallic trifluoroacetates to ternary fluoroperovskites. Decomposition of bimetallic trifluoroacetates also yielded alkali hexafluorosilicates K2SiF6 and Cs2SiF6 as a result of the fluorination of a-SiO2. This reactivity pattern was exploited to create a straightforward all-solid-state route to hexa- and heptafluorosilicates via thermal decomposition of monometallic trifluoroacetates KH(tfa)2 and CsH(tfa)2 under air. These findings enlarge the library of fluorinated organic–inorganic hybrid materials and the toolbox of synthetic routes to fluorosilicates.

Future research avenues include (1) expanding the proposed solid-state route to more compositionally complex targets such as quaternary fluorosilicates,55 (2) developing the chemistry to incorporate optically relevant dopants such as Mn4+ during the thermal decomposition stage, and (3) understanding the mechanistic aspects of the formation of fluorosilicates from metal trifluoroacetates (i.e., fluorinating species, phase equilibria, and kinetics).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the financial support of the National Science Foundation (DMR-2003118) and of the Michigan Space Grant Consortium (Grant NNX15AJ20H). They are also grateful for the support of Wayne State University through a Thomas C. Rumble Graduate Fellowship and for the use of the X-ray core in the Lumigen Instrument Center (National Institutes of Health supplement grant 3R01EB027103-02S1 and National Science Foundation grant MRI-1427926).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: (1) thermal analyses of bimetallic trifluoroacetates, (2) crystal structures of bimetallic fluorotrifluoroacetates, (3) reflection list of Cs2MnF4, (4) crystal structure of KH(tfa)2, and (5) control experiments using KF and CsF. See DOI:10.1039/x0xx00000x10.1039/x0xx00000x.

Notes and references

- 1.Dhanapala BD; Munasinghe HN; Suescun L; Rabuffetti FA, Bimetallic Trifluoroacetates as Single-Source Precursors for Alkali–Manganese Fluoroperovskites. Inorganic Chemistry 2017, 56, 13311–13320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dhanapala BD; Mannino NA; Mendoza LM; Dissanayake KT; Martin PD; Suescun L; Rabuffetti FA, Synthesis of Bimetallic Trifluoroacetates Through a Crystallochemical Investigation of Their Monometallic Counterparts: The Case of (A, A′)(CF3COO)2·nH2O (A, A′ = Mg, Ca, Sr, Ba, Mn). Dalton Transactions 2017, 46, 1420–1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Munárriz J; Rabuffetti FA; Contreras-García J, Building Fluorinated Hybrid Crystals: Understanding the Role of Noncovalent Interactions. Crystal Growth & Design 2018, 18, 6901–6910. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Szlag RG; Suescun L; Dhanapala BD; Rabuffetti FA, Rubidium–Alkaline-Earth Trifluoroacetate Hybrids as Self-Fluorinating Single-Source Precursors to Mixed-Metal Fluorides. Inorganic Chemistry 2019, 58, 3041–3049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Munasinghe HN; Suescun L; Dhanapala BD; Rabuffetti FA, Bimetallic Trifluoroacetates as Precursors to Layered Perovskites A2MnF4 (A = K, Rb, and Cs). Inorganic Chemistry 2020, 59, 17268–17275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kiyohide M; Etsuko T; Midori A; Kiyosi K, A Convenient Trifluoromethylation of Aromatic Halides with Sodium Trifluoroacetate. Chemistry Letters 1981, 10, 1719–1720. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang Y; Cai C, Sodium Trifluoroacetate: An Efficient Precursor for the Trifluoromethylation of Aldehydes. Tetrahedron Letters 2005, 46, 3161–3164. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen M; Buchwald SL, Rapid and Efficient Trifluoromethylation of Aromatic and Heteroaromatic Compounds Using Potassium Trifluoroacetate Enabled by a Flow System. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2013, 52, 11628–11631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bogdanov VP; Dmitrieva VA; Ioutsi VA; Belov NM; Goryunkov AA, Alkali Metal Trifluoroacetates for the Nucleophilic Trifluoromethylation of Fullerenes. Journal of Fluorine Chemistry 2019, 226, 109344. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bogdanov VP; Dmitrieva VA; Rybalchenko AV; Yankova TS; Kosaya MP; Romanova NA; Belov NM; Borisova NE; Troyanov SI; Goryunkov AA, Para-C60(CF2)(CF3)R: A Family of Chiral Electron Accepting Compounds Accessible Through a Facile One-Pot Synthesis. European Journal of Organic Chemistry 2021, 2021, 5147–5150. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adachi S; Takahashi T, Direct Synthesis and Properties of K2SiF6:Mn4+ Phosphor by Wet Chemical Etching of Si Wafer. Journal of Applied Physics 2008, 104, 023512. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adachi S; Abe H; Kasa R; Arai T, Synthesis and Properties of Hetero-Dialkaline Hexafluorosilicate Red Phosphor KNaSiF6:Mn4+. Journal of The Electrochemical Society 2011, 159, J34–J37. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nguyen H-D; Lin CC; Fang M-H; Liu R-S, Synthesis of Na2SiF6:Mn4+ Red Phosphors for White LED Applications by Co-Precipitation. Journal of Materials Chemistry C 2014, 2, 10268–10272. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jin Y; Fang M-H; Grinberg M; Mahlik S; Lesniewski T; Brik MG; Luo G-Y; Lin JG; Liu R-S, Narrow Red Emission Band Fluoride Phosphor KNaSiF6:Mn4+ for Warm White Light-Emitting Diodes. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2016, 8, 11194–11203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luo X; Hou Z; Zhou T; Xie R-J, A Universal HF-Free Synthetic Method to Highly Efficient Narrow-Band Red-Emitting A2XF6:Mn4+ (A = K, Na, Rb, Cs; X = Si, Ge, Ti) Phosphors. Journal of the American Ceramic Society 2020, 103, 1018–1026. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhong X; Deng D; Wang T; Li Y; Yu Y; Qiang J; Liao S; Huang Y; Long J, High Water Resistance and Luminescent Thermal Stability of LiyNa(2–y)SiF6:Mn4+ Red-Emitting Phosphor Induced by Codoping of Li+. Inorganic Chemistry 2022, 61, 5484–5494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim M; Park WB; Bang B; Kim CH; Sohn K-S, A Novel Mn4+-Activated Red Phosphor for Use in Light Emitting Diodes, K3SiF7:Mn4+. Journal of the American Ceramic Society 2017, 100, 1044–1050. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim M; Park WB; Lee J-W; Lee J; Kim CH; Singh SP; Sohn K-S, Rb3SiF7:Mn4+ and Rb2CsSiF7:Mn4+ Red-Emitting Phosphors with a Faster Decay Rate. Chemistry of Materials 2018, 30, 6936–6944. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jang S; Park JK; Kim M; Sohn K-S; Kim CH; Chang H, New Red-Emitting Phosphor RbxK3−xSiF7:Mn4+ (x = 0, 1, 2, 3): DFT Predictions and Synthesis. RSC Advances 2019, 9, 39589–39594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim YH; Ha J; Im WB, Towards Green Synthesis of Mn4+-Doped Fluoride Phosphors: A Review. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2021, 11, 181–195. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang L; Zhu Y; Zhang X; Zou R; Pan F; Wang J; Wu M, HF-Free Hydrothermal Route for Synthesis of Highly Efficient Narrow-Band Red Emitting Phosphor K2Si1–xF6:xMn4+ for Warm White Light-Emitting Diodes. Chemistry of Materials 2016, 28, 1495–1502. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hou Z; Tang X; Luo X; Zhou T; Zhang L; Xie R-J, A Green Synthetic Route to the Highly Efficient K2SiF6:Mn4+ Narrow-Band Red Phosphor for Warm White Light-Emitting Diodes. Journal of Materials Chemistry C 2018, 6, 2741–2746. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dissanayake KT; Mendoza LM; Martin PD; Suescun L; Rabuffetti FA, Open-Framework Structures of Anhydrous Sr(CF3COO)2 and Ba(CF3COO)2. Inorganic Chemistry 2016, 55, 170–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dallenbach R; Tissot P, Properties of Molten Alkali Metal Trifluoroacetates. Part I. Study of the Binary System CF3COOK−CF3COONa. Journal of Thermal Analysis 1977, 11, 61–69. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dallenbach R; Tissot P, Properties of Molten Alkali Metal Trifluoroacetates. Part II. Thermal Properties and Kinetics of Thermal Decomposition. Journal of Thermal Analysis 1981, 20, 409–417. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krause L; Herbst-Irmer R; Sheldrick GM; Stalke D, Comparison of Silver and Molybdenum Microfocus X-ray Sources for Single-Crystal Structure Determination. Journal of Applied Crystallography 2015, 48, 3–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sheldrick G, Crystal Structure Refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallographica Section C 2015, 71, 3–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sheldrick GM SHELXL 2014/7: Program for Crystal Structure Solution, University of Gottingen: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hubschle CB; Sheldrick GM; Dittrich B, ShelXle: a Qt Graphical User Interface for SHELXL. Journal of Applied Crystallography 2011, 44, 1281–1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Momma K; Izumi F, VESTA 3 for Three-Dimensional Visualization of Crystal, Volumetric and Morphology Data. Journal of Applied Crystallography 2011, 44, 1272–1276. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tereshchenko DS; Morozov I; Boltalin AI; Kemnitz E; Troyanov SI, Trinuclear Co(II) and Ni(II) Complexes with Tridentate Fluorine, [M3(μ3-F)(CF3COO)6(CF3COOH)3]−: Synthesis and Crystal Structure. Zhurnal Neorganicheskoj Khimii 2004, 49, 919–928. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Noack J; Fritz C; Flügel C; Hemmann F; Gläsel H-J; Kahle O; Dreyer C; Bauer M; Kemnitz E, Metal Fluoride-Based Transparent Nanocomposites with Low Refractive Indices. Dalton Transactions 2013, 42, 5706–5710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tereshchenko DS; Morozov IV; Boltalin AI; Karpova EV; Glazunova TY; Troyanov SI, Alkali Metal and Ammonium Fluoro(trifluoroacetato)metallates M′[M′′3(μ3-F)(CF3COO)6(CF3COOH)3], where M′ = Li, Na, K, NH4, Rb, or Cs and M′′ = Ni or Co. Synthesis and Crystal Structures. Crystallography Reports 2013, 58, 68–77. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morozov IV; Karpova EV; Glazunova TY; Boltalin AI; Zakharov MA; Tereshchenko DS; Fedorova AA; Troyanov SI, Trifluoroacetate Complexes of 3d Elements: Specific Features of Syntheses and Structures. Russian Journal of Coordination Chemistry 2016, 42, 647–661. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Glazunova TY; Tereshchenko DS; Buzoverov ME; Karpova EV; Lermontova EK, Synthesis and Crystal Structures of New Potassium Fluorotrifluoroacetatometallates: Kn[M3(μ3-F)(CF3COO)6L3]L’ (M = Co, Ni; L = CF3COO–, CF3COOH, H2O; L’ = CF3COOH, H2O; n = 1, 2). Russian Journal of Coordination Chemistry 2021, 47, 347–355. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dissanayake KT; Amarasinghe DK; Suescun L; Rabuffetti FA, Accessing Mixed-Halide Upconverters Using Heterohaloacetate Precursors. Chemistry of Materials 2019, 31, 6262–6267. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dhanapala BD; Munasinghe HN; Dissanayake KT; Suescun L; Rabuffetti FA, Expanding the Synthetic Toolbox to Access Pristine and Rare-Earth-Doped BaFBr Nanocrystals. Dalton Transactions 2021, 50, 16092–16098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haiduc I, Inverse Coordination – An Emerging New Chemical Concept. II. Halogens as Coordination Centers. Coordination Chemistry Reviews 2017, 348, 71–91. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wörle M; Guntlin CP; Gyr L; Sougrati MT; Lambert C-H; Kravchyk KV; Zenobi R; Kovalenko MV, Structural Evolution of Iron(III) Trifluoroacetate upon Thermal Decomposition: Chains, Layers, and Rings. Chemistry of Materials 2020, 32, 2482–2488. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Birchall JM; Haszeldine RN; Roberts DW, Cyclopropane Chemistry. Part II. Cyclopropanes as Sources of Difluorocarbene. Journal of the Chemical Society, Perkin Transactions 1 1973, 0, 1071–1078. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barela MJ; Anderson HM; Oehrlein GS, Role of C2F4, CF2, and Ions in C4F8∕Ar Plasma Discharges Under Active Oxide Etch Conditions in an Inductively Coupled GEC Cell Reactor. Journal of Vacuum Science & Technology A 2005, 23, 408–416. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Farjas J; Camps J; Roura P; Ricart S; Puig T; Obradors X, The Thermal Decomposition of Barium Trifluoroacetate. Thermochimica Acta 2012, 544, 77–83. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mosiadz M; Juda KL; Hopkins SC; Soloducho J; Glowacki BA, An In-Depth in situ IR Study of the Thermal Decomposition of Yttrium Trifluoroacetate Hydrate. Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry 2012, 107, 681–691. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Blake PG; Pritchard H, The Thermal Decomposition of Trifluoroacetic Acid. Journal of the Chemical Society B: Physical Organic 1967, 0, 282–286. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jollie DM; Harrison PG, An in situ IR Study of the Thermal Decomposition of Trifluoroacetic Acid. Journal of the Chemical Society, Perkin Transactions 2 1997, 8, 1571–1576. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rillings KW; Roberts JE, A Thermal Study of the Trifluoroacetates and Pentafluoropropionates of Praseodymium, Samarium and Erbium. Thermochimica Acta 1974, 10, 269–277. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eloussifi H; Farjas J; Roura P; Camps J; Dammak M; Ricart S; Puig T; Obradors X, Evolution of Yttrium Trifluoroacetate During Thermal Decomposition. Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry 2012, 108, 589–596. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Opata YA; Grivel JC, Synthesis and Thermal Decomposition Study of Dysprosium Trifluoroacetate. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis 2018, 132, 40–46. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Golič L; Speakman JC, The Crystal Structures of the Acid Salts of Some Monobasic Acids. Part X. Potassium, Rubidium, and Cæsium Hydrogen Di-Trifluoroacetates. Journal of the Chemical Society 1965, 0, 2530–2542. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Deadmore DL; Bradley WF, The Crystal Structure of K3SiF7. Acta Crystallographica 1962, 15, 186–189. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kolditz L; Wilde W; Bentrup U, Zur Bildung der Phase K3SiF7 Durch Thermische Zersetzung von K2[SiF6]. Zeitschrift für Chemie 1983, 23, 246–247. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vanetsev A; Põdder P; Oja M; Khaidukov NM; Makhov VN; Nagirnyi V; Romet I; Vielhauer S; Mändar H; Kirm M, Microwave-Hydrothermal Synthesis and Investigation of Mn-Doped K2SiF6 Microsize Powder as a Red Phosphor for Warm White LEDs. Journal of Luminescence 2021, 239, 118389. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hofmann B; Hoppe R, Zur Kenntnis des (NH4)3SiF7-Typs. Neue Metallfluoride A3MF7 mit M = Si, Ti, Cr, Mn, Ni und A = Rb, Cs. Zeitschrift für Anorganische und Allgemeine Chemie 1979, 458, 151–162. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Singh VS; Moharil SV, Synthesis and Characterization of K2SiF6 Hexafluorosilicate. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2021, 1104, 012004. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stoll C; Seibald M; Baumann D; Bandemehr J; Kraus F; Huppertz H, KLiSiF6 and CsLiSiF6 – A Structure Investigation. European Journal of Inorganic Chemistry 2021, 2021, 62–70. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.