Abstract

Background

An association between thrombotic events and SARS-CoV-2 infection and the adenovirus-based COVID-19 vaccines has been established, leading to concern over the risk of thrombosis after BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccination.

Objectives

To evaluate the risk of arterial thrombosis, cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT), splanchnic thrombosis, and venous thromboembolism (VTE) following BNT162b2 vaccination in New Zealand.

Methods

This was a self-controlled case series using national hospitalisation and immunisation records to calculate incidence rate ratios (IRR). The study population included individuals aged ≥12 years, unvaccinated, or vaccinated with BNT162b2, who were hospitalised with one of the thrombotic events of interest from 19 February 2021 through 19 February 2022. The risk period was 0–21 days after receiving a primary or booster dose of BNT162b2.

Results

6039 individuals were hospitalised with one of the thrombotic events examined, including 5127 with VTE, 605 with arterial thrombosis, 272 with splanchnic thrombosis, and 35 with CVT. The proportion of individuals vaccinated with at least one dose of BNT162b2 ranged from 82.7 % to 91.4 %. Compared with the control unexposed period, the IRR (95 % CI) of VTE, arterial thrombosis, splanchnic thrombosis, and CVT were 0.87 (0.76–1.00), 0.73 (0.56–0.95), 0.71 (0.43–1.16), and 0.87 (0.31–2.50) in the 21 days after BNT162b2 vaccination, respectively. There was no statistically significant increased risk of thrombosis following BNT162b2 in different ethnic groups in New Zealand.

Conclusion

The BNT162b2 vaccine was not found to be associated with thrombosis in the general population or different ethnic groups in New Zealand, providing reassurance for the safety of the BNT162b2 vaccine.

Keywords: COVID-19, mRNA vaccines, Thrombosis, Pharmacovigilance, Pharmacoepidemiology

1. Introduction

Thrombotic events have emerged as a known and serious complication of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection [1], [2], [3]. An association between thrombosis and the adenovirus based COVID-19 vaccines; ChAdOx1-S nCoV-19 (Oxford-AstraZeneca/Vaxzevria) and Ad26.COV2.S (Johnson & Johnson's Janssen/Jcovden) has also been established, including thrombotic events with and without thrombocytopenia [4], [5], [6], [7], [8]. As a result, there has been increased public and regulatory concern over the risk of thrombosis following the mRNA COVID-19 vaccines, such as the BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine (Pfizer-BioNTech/Comirnaty, hereafter BNT162b2). New Zealand's COVID-19 Vaccine and Immunisation programme began vaccinations in February 2021 and almost exclusively uses the BNT162b2 vaccine [9]. Although the Pfizer-BioNTech phase III clinical trials [10] and subsequent international observational studies [5], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15] have not found an association between the two, thrombotic events have been reported following the BNT162b2 vaccine through the New Zealand spontaneous reporting (passive surveillance) system [16] and internationally [17], [18]. Moreover, a self-controlled case series (SCCS) study in England reported an increased risk of cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT) and arterial thrombosis during the 15 to 21 days after the first dose of the BNT162b2 vaccine [6].

Rigorous post-marketing surveillance of the BNT162b2 vaccine is therefore needed to understand the risk of thrombosis following immunisation in the population, especially as concern around adverse events is a leading contributor to vaccine hesitancy [19]. It is particularly important in New Zealand, as the country has a unique demographic, consisting of three main minority ethnic groups, Māori (indigenous New Zealanders) (16.5 % of the population), Pacific peoples (Pacific islanders living in New Zealand) (8.1 % of the population), and Asian (15.1 % of the population), alongside the majority group, New Zealand Europeans (70.2 % of the population) [20]. New Zealand's Māori and Pacific peoples were not included in the Pfizer-BioNTech phase III clinical trials [10] or any subsequent international post-licensure COVID-19 vaccine studies. Furthermore, Māori and Pacific peoples are at greater risk of hospitalisation and morbidity from COVID-19 [21], [22], and persistent inequities in health experiences, access, and outcomes has been observed in these groups, including access to COVID-19 vaccinations [23], [24], [25]. Vaccine coverage has also been traditionally lower for Māori and Pacific peoples compared to other ethnic groups in New Zealand [26], [27], [28].

New Zealand is uniquely placed to carry out pharmacovigilance of COVID-19 vaccines in the real-world. Throughout the first year of vaccinations, the country had low rates of SARS-CoV-2 in the community, largely due to the government's commitment to an elimination strategy [29]. As a result, approximately 95.5 % of the total eligible population had received at least one dose of the BNT162b2 vaccine prior to the widespread community outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 from late February 2022 [30]. Given that thrombosis is also associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection, high rates of undetected infection seen in many countries throughout the pandemic can confound vaccine safety studies. New Zealand therefore provides an ideal setting to study the relationship between thrombotic events and the BNT162b2 vaccine. Given the conflicting information in the literature, the concern from the public and regulatory authorities, and the need to understand the association between thrombotic events and the BNT162b2 vaccine in the New Zealand population, we conducted a population-based self-controlled case series (SCCS) study using national electronic health records.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

We carried out an SCCS study to compare the incidence of an event of interest in an exposed risk period (e.g., post-vaccination) to all other “unexposed” periods (the control period) within individuals [31], [32], [33]. The observation period began with the start of COVID-19 vaccinations in New Zealand on 19 February 2021 through 19 February 2022. The study population comprised all individuals, aged 12 years and older, unvaccinated, or vaccinated with the BNT162b2 vaccine who were hospitalised with one of the prespecified thrombotic events during the observation period. We excluded individuals who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection 31 days prior to the event to remove any potential bias associated with the increased risk of thrombosis following COVID-19 [1]. Participants vaccinated with a COVID-19 vaccine other than the BNT162b2 vaccine were also excluded.

2.2. Prespecified events

We identified four prespecified thrombotic events for inclusion in this study: arterial thrombosis, cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT), splanchnic thrombosis, and venous thromboembolism (VTE), based on their identification as an adverse event of special interest (AESI) for the BNT162b2 vaccine COVID-19 vaccine [34]. We used International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision, Australian Modification (ICD-10-AM) diagnosis codes to identify these events (Supplementary Table S1).

2.3. Data sources

We used a de-identified dataset, prepared by the Data and Analytics team within the Ministry of Health New Zealand. Prespecified events were identified from the National Minimum Data Set (NMDS), a national collection of all public and most private hospital discharges, including coded clinical data for inpatients and day patients [35]. All New Zealand citizens (including Cook Islands, Niue, or Tokelau), residents, or individuals with a work visa that is valid for two years or more, are eligible for publicly funded health and disability services [36]. The National Health Index (NHI) number is provided to each person who uses these services. The Data and Analytics team used the NHI number to link the hospitalisation information with BNT162b2 vaccination records in the national COVID Immunisation Register (CIR), a database of all COVID-19 vaccination information in New Zealand [37]. The CIR also provides information on the mortality status of vaccinated individuals as it is linked via the NHI number to the Health Service Utilisation (HSU), which provides estimates of the New Zealand population. The Pandemic Minimum Dataset, New Zealand's national notifiable disease repository for COVID-19, was used to check if an individual tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection during the observation period.

2.4. Exposures

The BNT162b2 vaccine is normally administered as a two dose primary series (for some people the primary course can be >2 doses), with the government recommended dosing interval ranging from three to six weeks at different stages of the vaccine rollout in New Zealand [38], [39], [40]. Booster doses were offered from November 2021. These were provisionally approved by Medsafe, New Zealand's medicines and medical devices safety authority, for use six months after the primary course, however programme changes reduced this interval to four and then three months [36]. We classified an individual as exposed after receiving either a first, second, or booster dose of the vaccine within a prespecified risk window during the study observation period. Individuals who received >2 doses as their primary vaccination course were excluded from the analyses. We combined our analyses for all exposure periods as the vaccine effect was the same for each dose i.e., the risk was non dose dependent. The risk period for all events was set as 0–21 days after the first, second, and booster vaccine doses. This is in line with the approved 3-week interval between the two primary doses [39] and a generally accepted risk interval for these types of events following COVID-19 vaccination [14]. We also tested the significance of implementing multiple risk intervals (0–6, 7–13, 14–21 days).

2.5. Statistical analysis

We conducted our primary analysis using the SCCS package constructed by Weldeselassie and Farrington [39] within the R statistical package [40]. The SCCS models were fitted with a conditional Poisson regression model to estimate incidence rate ratios (IRRs) and 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) for the thrombotic events within the exposed risk period compared to the control (unexposed) periods. Since this method involves within person comparisons, time-invariant confounders such as sex, ethnicity, and underlying health conditions, are automatically adjusted for [41].We tested the significance of the time-invariant effect modifiers; ethnicity, gender, and age group on the model. We compensated for time varying confounders by adjusting for seasonality (4 seasons in the New Zealand calendar year) as the risk of a thrombotic event may follow a seasonal pattern [42], [43], [44]. Only the summer boundaries were implemented for CVT due to the scarcity of events. We also performed subgroup analyses to estimate the IRRs in different ethnic groups in New Zealand.

2.6. Sensitivity analyses

The standard SCCS model carries several assumptions, one of which is that events should arise independently within individuals [31]. This was tested using the Fleming-Harrington cumulative hazard plot. Only the first hospitalisation event was included in the model if this assumption was violated. Another assumption is that the occurrence of an event does not influence the probability of exposure [31]. To test this, we plotted a histogram of the time between vaccination and the occurrence of an event to determine whether the occurrence of a thrombotic event affected the timing of exposures e.g., results in an individual delaying or cancelling vaccination (the healthy vaccine bias). We introduced a pre-exposure risk period to compensate for any delays in vaccination and tested the significance of the event-dependent exposures on the model. We varied the length of the pre-exposure periods, between 2 and 42 days, and examined the impact on the relative incidence in both the pre-exposure and risk periods. If the event dependent exposure was not compensated for i.e., the delay in vaccination was prolonged, we implemented an extension of the SCCS method: the SCCS model for event-dependent exposures [45], [46]. This model assumes that after every event, vaccination can be delayed or cancelled in an unspecified manner. As such, only exposures preceding the event were included in this model. We applied the modified SCCS for event dependent exposures using the R function “eventdepenexp” in the R-package “SCCS” [46].

The other form of event-dependence is when an event is associated with or is a death. In the standard SCCS model, deaths censor the observation period which violates the assumption that events should be independent of the observation period (event-dependent observation) [31]. Deaths caused by an event complicate the model but can provide useful information about the timing of the event. To investigate, we plotted a histogram of the data to visualise if there was event clustering at the end of the observation period and calculated the number of deaths that occurred after each event. We examined the significance of this on the SCCS model. If we observed both event dependent observations and an association between death and the events of interest (event dependent exposures), we implemented a recently proposed modification to the SCCS method [33]. This method was developed specifically to compensate for both event-dependent exposures and high-event related mortality associated with some AESI following COVID-19 vaccinations. The model assumes that all deaths are related to the events observed and uses the planned end of observation rather than the date of death as the end of the observation period.

2.7. Ethics approval

This observational study did not require informed consent since we used deidentified data to conduct our analyses. As such, we received an exemption from the Health and Disability Ethics Committee (HDEC) of New Zealand (Reference #: 11950).

3. Results

3.1. Patient demographics

The demographics of all individuals, aged 12 years or older, hospitalised with one of the prespecified thrombotic events from the 19 February 2021 through to 19 February 2022 are presented in Table 1 . A total of 6039 individuals were identified, including 5127 (84.9 %) with a hospital diagnosis of VTE, 605 (10.0 %) with arterial thrombosis, 272 (4.5 %) with splanchnic thrombosis, and 35 (0.6 %) with CVT. There were 4439 (86.6 %) of 5127 individuals diagnosed with VTE, 520 (86.0 %) of 605 individuals diagnosed with arterial thrombosis, 225 (82.7 %) of 272 diagnosed with splanchnic thrombosis and 32 (91.4 %) of 35 individuals diagnosed with CVT that received at least one dose of the BNT162b2 vaccine.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics of 6039 individuals hospitalised with a diagnosis of one of the prespecified thrombotic events, 19 February 2021 through 19 February 2022, New Zealand.

| Arterial thrombosis (%) | Cerebral venous thrombosis (%) | Splanchnic thrombosis (%) | Venous thromboembolism (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosed | 605 (10.0) | 35 (0.6) | 272 (4.5) | 5127 (84.9) | |

| Deaths | 119 (19.7) | ≤6a | 71 (26.1) | 980 (19.1) | |

| Vaccinated with ≥1 dose of the vaccine | 520 (86.0) | 32 (91.4) | 225 (82.7) | 4439 (86.6) | |

| Modal age group | 76–101 | 46–55 | 66–75 | 76–103 | |

| Sex | Male | 332 (54.9) | 15 (42.9) | 162 (59.6) | 2510 (49.0) |

| Female | 273 (45.1) | 20 (57.1) | 110 (40.4) | 2617 (51.0) | |

| Ethnicity | Māori and Pacific | 118 (19.5) | ≤6 | 57 (21.0) | 868 (16.9) |

| NZ European, Asian, and other | 457 (75.5) | 21 (60.0) | 186 (68.4) | 3942 (76.9) | |

| Unknown | 30 (5.0) | 8 (22.9) | 29 (10.7) | 317 (6.2) | |

Events with fewer than six occurrences have been suppressed for privacy reasons.

As of 19 February 2022, approximately 95.5 % of the eligible population in New Zealand (or 4,685,351 individuals), aged 12 years or older, had received at least one dose of the BNT162b2 vaccine. This equates to 86.0 % (or 490,851 individuals) of Māori, 88.2 % (or 252,881 individuals) of Pacific Peoples, 89.9 % (or 2,457,182 individuals) of NZ European and 89.9 % (or 538,175 individuals) of Asian, aged 12 years and older, having received at least one dose of the vaccine during the study period.

3.2. Association between thrombotic events and the BNT162b2 vaccine

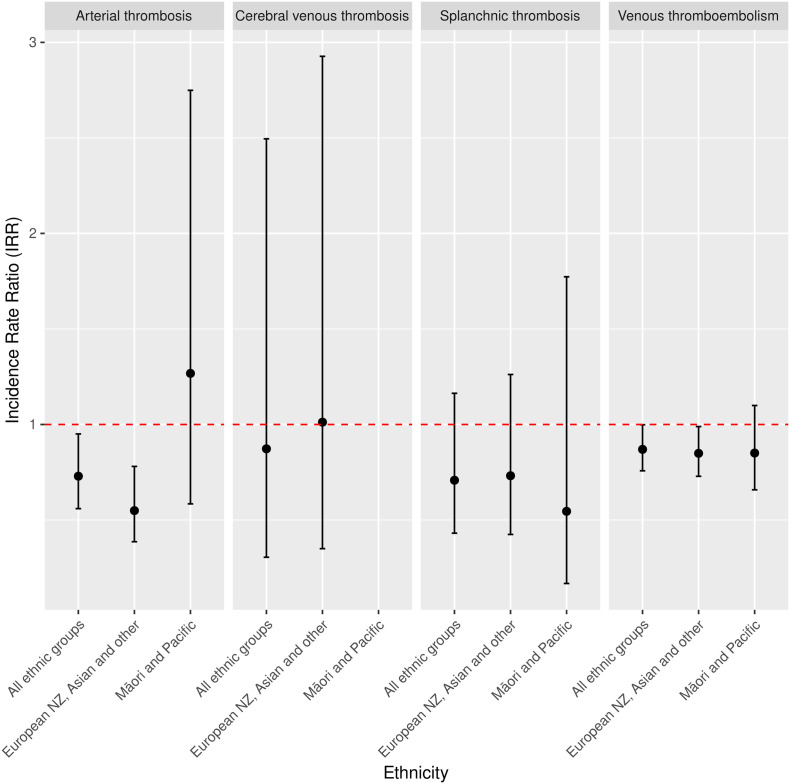

Compared with the control, non-exposure period, the IRR (95 % CI) of VTE, arterial thrombosis, splanchnic thrombosis, and CVT were 0.87 (0.76–1.00), 0.73 (0.56–0.95), 0.71 (0.43–1.16), and 0.87 (0.31–2.50), respectively, in the 21 days following either the first, second or booster dose of the BNT162b2 vaccine in the general New Zealand population (Table 2 and Fig. 1 ). The IRR (95 % CI) of VTE, arterial thrombosis, and splanchnic thrombosis in the Māori and Pacific subgroup were 0.85(0.66–1.10), 1.27 (0.58–2.75), and 0.55 (0.17–1.77), respectively. The IRR (95 % CI) of CVT could not be calculated in this subgroup as there were too few events observed. The IRR (95 % CI) of VTE, arterial thrombosis, splanchnic thrombosis and CVT in the New Zealand European, Asian, and other subgroup were 0.85 (0.73–0.99), 0.55 (0.39–0.78), 0.73 (0.42–1.26), and 1.10 (0.35–2.93).

Table 2.

Incidence rate ratios (95 % confidence intervals) of the prespecified thrombotic events in the 0–21-day risk period after exposure to the first, second or booster dose of the BNT162b2 vaccine in the general population and different ethnic groups in New Zealand, 19 February 2021 through 19 February 2022.

| Outcome | No. of events | Incidence rate ratioa (95 % CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arterial thrombosis | |||

| General population (all groups) | Baseline | 605 | |

| 0–21 days | 65 | 0.73 (0.56 to 0.95) | |

| Māori and Pacific | Baseline | 118 | |

| 0–21 days | 8 | 1.27 (0.58 to 2.75) | |

| European NZ, Asian, and other | Baseline | 662 | |

| 0–21 days | 54 | 0.55 (0.39 to 0.78) | |

| Cerebral venous thrombosis | |||

| General population (all groups) | Baseline | 35 | |

| 0–21 days | ≤6b | 0.87 (0.31 to 2.50) | |

| Māori and Pacific | Baseline | ≤6 | |

| 0–21 days | –c | – | |

| European NZ, Asian, and other | Baseline | 21 | |

| 0–21 days | ≤6 | 1.01 (0.35 to 2.93) | |

| Splanchnic thrombosis | |||

| General population (all groups) | Baseline | 272 | |

| 0–21 days | 26 | 0.71 (0.43 to 1.16) | |

| Māori and Pacific | Baseline | 57 | |

| 0–21 days | ≤6 | 0.55 (0.17 to 1.77) | |

| European NZ, Asian, and other | Baseline | 215 | |

| 0–21 days | 23 | 0.73 (0.42 to 1.26) | |

| Venous thromboembolism | |||

| General population (all groups) | Baseline | 5127 | |

| 0–21 days | 641 | 0.87 (0.76 to 1.00) | |

| Māori and Pacific | Baseline | 1113 | |

| 0–21 days | 107 | 0.85 (0.66 to 1.10) | |

| European NZ, Asian, and other | Baseline | 4259 | |

| 0–21 days | 534 | 0.85 (0.73 to 0.99) | |

Note: Only the first event experienced by an individual is included.

IRRs were calculated using Poisson regression and adjusted for seasonality.

Events with fewer than six occurrences have been suppressed for privacy reasons.

The IRR was not calculated as there were too few events observed.

Fig. 1.

Incidence rate ratios (95 % CI) of the prespecified thrombotic events in the 0–21 days after exposure to the first, second or third dose of the BNT162b2 vaccine in the general population (all ethnic groups) and different ethnic groups in New Zealand, 19 February 2021 through 19 February 2022. Note: The IRR of CVT in the Māori and Pacific subgroup was not calculated as there were too few events observed.

3.3. Sensitivity analyses

Table 3 presents the significance (p-value) of the effect modifiers (ethnicity, gender, and age), seasonal effect and the effect of the SCCS assumptions on the analysis. Each of the effect modifiers returned non-significant effects for all outcomes. There was a seasonal effect present for all thrombotic events except CVT. The number of thrombotic events observed in each season is outlined in Supplementary Table S2. For all outcomes, the lowest proportion of events were diagnosed in a hospital setting during the summer months in New Zealand (November 2021 through February 2022).

Table 3.

The significance (p-value) of the effect modifiers, seasonal effect and SCCS assumptions on the analyses, and the final model configurations utilised to calculate the incidence rate ratios for each thrombotic event.

| Arterial thrombosis | Cerebral venous thrombosis | Splanchnic thrombosis | Venous thromboembolism | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seasonal effect | 0.010 | 0.897 | 0.003 | <0.001 |

| Dose dependence | 0.512 | 0.346 | 0.650 | 0.049 |

| Age effect modifier | 0.077 | 0.319 | 0.137 | 0.470 |

| Ethnicity effect modifier | 0.879 | 0.295 | 0.504 | 0.639 |

| Gender effect modifier | 0.107 | 0.428 | 0.230 | 0.493 |

| Event dependent exposure | <0.001 | 0.075 | 0.010 | <0.001 |

| Event dependent count | <0.001 | 0.067 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Event dependent impact | 0.160 | –a | 0.329 | <0.001 |

| Final model implemented | Event dependent exposure modelb | Standard SCCS model | Event dependent exposure model | Adaption to the event dependent exposure model for high event-related mortalityc |

There was a clustering of events (event dependent events) for all outcomes (Supplementary Fig. S1). As such, only the first hospitalisation event was included in the analysis. For all events except CVT, the event dependent exposures observed had a significant effect on the model (Table 3). There was a decrease in the number of events immediately before vaccination, indicating the presence of event dependent exposures (Supplementary Fig. S2a–d). The event dependent exposures observed for these events were not fully compensated for by implementing a pre-exposure period (2–42 days) (Supplementary Fig. S3a–d). We therefore implemented an extension to the standard SCCS model previously described [45], [46], for VTE, arterial thrombosis, and splanchnic thrombosis. We also observed a significant association between the number of deaths and the occurrence of VTE (Supplementary Fig. S4) and implemented an adaption to the event dependent exposure model that accounts for high-event related mortality [33]. The final SCCS model used for each event of interest is presented in Table 3.

4. Discussion

This nationwide SCCS study did not find evidence of a significantly increased risk of arterial thrombosis, CVT, splanchnic thrombosis, or VTE in the 21 days following the first, second, or booster dose of the BNT162b2 vaccine during the first year of COVID-19 vaccinations in New Zealand (19 February 2021 through 19 February 2022). We also observed no increased risk of developing a thrombotic event following vaccination across different ethnic groups in the country, including Māori (indigenous New Zealanders) and Pacific peoples. We observed a large reduction in events prior to and following vaccination, highlighting the presence of the healthy vaccine effect in our study [47].

These findings are consistent with other population based post-market studies that observed no increased risk of developing thromboembolic events following receipt of the BNT162b2 vaccine [5], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15]. Conversely, a SCCS study based in the United Kingdom (UK) by Hippisley-Cox, et al found an increased risk of CVT and arterial thrombosis 15–21 days after a first dose of the BNT162b2 vaccine [6]. However, the IRR for arterial thrombosis was low (1.06) and confidence intervals near 1.00 (1.01 to 1.10). Additionally, the confidence intervals for CVT were wide (1.39 to 9.29) due to the small number of events (6 events) observed in the study, limiting the conclusions that can be made from that study. Furthermore, only vaccinated participants (first dose only) were included and the study used a pre-risk period of 28 days to compensate for event-dependent exposures observed. Our findings suggest that due to the often-serious nature of these thrombotic events, the delay in vaccination can be prolonged and high-event mortality is sometimes observed. This can introduce bias and we implemented a modified SCCS method that was proposed specifically for COVID-19 vaccine safety studies, to account for both delays in vaccination and high-event related mortalities [33].

New Zealand provides a unique setting and population to study the safety of the BNT162b2 vaccine. Firstly, the country had limited to no COVID-19 cases for the first two years of the pandemic due to the government's effective execution of an elimination strategy [29]. This coincides with our study period and allowed us to have confidence in the pharmacovigilance of the BNT162b2 vaccine since there were minimal cases of COVID-19 in the community. Therefore, it is unlikely that any adverse events observed following immunisation were a result of infection. Secondly, New Zealand has had high vaccination coverage and at the time of this study, approximately 95.5 % of the eligible population had received at least one dose of the BNT162b2 vaccine. Thirdly, we used a large and complete dataset which included information on all public and some private hospital discharges, which was linked to data on all participants who received a first, second, or booster dose of the BNT162b2 vaccine in New Zealand. Notably, during the study period, the adult formulation of the BNT162b2 vaccine was made freely available to all individuals in New Zealand aged 12 years and over as a primary vaccination course, and for individuals aged 18 years or older as a primary course and as a booster, regardless of whether they were eligible for publicly funded health and disability services.

The use of the SCCS method also has its advantages compared to a standard cohort or case-controlled methods in that it involves within-person comparisons which allows for controlling fixed characteristics such as sex, ethnicity, and underlying health conditions. We also adjusted for seasonality to account for any variation for the risk of thrombosis at different times of the year [42], [43], [44]. We carried out robust sensitivity analyses to assess the assumptions of the SCCS method and accounted for both thrombotic event-dependent exposures and high-event mortality observed in our models. We included unvaccinated individuals as these cases can provide information on the timing of events, as the absence of vaccination may indicate cancellation of vaccination. Failure to consider the magnitude of the healthy vaccine effect or the association between the occurrence of an event and death would have led to bias in the estimation of the baseline risk, and a subsequent increased risk of thrombotic events after vaccination compared to this baseline period. Finally, an important strength of our study was the ability to understand the safety of the BNT162b2 vaccine in all population subgroups in New Zealand. Our finding of no increased risk across different ethnic groups including Māori and Pacific peoples, can provide reassurance to the public and policy makers on the safety of the vaccine, especially as these groups were not represented in the BNT162b2 vaccine phase III clinical trials [10].

Our study is subject to several limitations. Firstly, we relied on hospital diagnosis codes to define our outcome measures and assessment of clinical records was not conducted to validate the diagnoses or codes used. Secondly, we were limited in the length of our study period. Although we followed individuals for a full year, extremely rare conditions such as CVT are difficult to detect, especially in New Zealand which has a relatively small population size (approximately 5.1 million people) [48]. Furthermore, the effects of any seasonal variation in the model may not have been fully adjusted for as this was based on a one-year cycle. Thirdly, our study used hospital discharge information only, including coded clinical data for inpatients and outpatients. Although many of the thrombotic events evaluated in this study can be serious and involve hospitalisation, some events, for example deep vein thrombosis (DVT), are typically treated in the primary care setting. As such, diagnoses made in primary care are not be included in our analyses and the incidence rates for certain events could be underestimated.

5. Conclusion

There was no observed association between the BNT162b2 vaccine and arterial thrombosis, CVT, splanchnic thrombosis, and VTE, requiring hospitalisation, during the 21 days following immunisation in the general population or in different ethnic groups in New Zealand. Therefore, this study provides reassurances on thrombotic safety of the BNT162b2 vaccine in both an international and New Zealand specific context. Further studies, with substantial population sizes are needed to assess the risk of CVT, which is an extremely rare event.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of the National Immunisation Programme within Health New Zealand (Te Whatu Ora), the Ministry of Health New Zealand (Manatū Hauora) and Medsafe with this study. The research was supported and critically reviewed by Janelle Duncan and Dr Christian Marchello of the National Immunisation Programme and Dr Susan Kenyon of the Clinical Risk Management branch within Medsafe. Equity consultation and review was provided by the Equity group within the National Immunisation Programme. Dr Laura Young and members of the COVID-19 Vaccine Independent Safety Monitoring Board provided expert advice. Open access funding was provided by the National Immunisation Programme 2022/23 Budget from the Ministry of Health, New Zealand.

Funding

The work reported in this publication was undertaken by the Vaccine Safety Surveillance and Research Group during the COVID-19 Vaccine and Immunisation programme within the Ministry of Health New Zealand. Funding for this programme was provided by the New Zealand government. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2022.12.012.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are not able to be made publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions outlined by New Zealand Legislation.

References

- 1.Ho F.K., Man K.K., Toshner M., et al. Thromboembolic risk in hospitalized and nonhospitalized COVID-19 patients: a self-controlled case series analysis of a nationwide cohort. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2021;96(10):2587–2597. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2021.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malas M.B., Naazie I.N., Elsayed N., et al. Thromboembolism risk of COVID-19 is high and associated with a higher risk of mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;29 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moschonas I.C., Tselepis A.D. SARS-CoV-2 infection and thrombotic complications: a narrative review. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis. 2021;52(1):111–123. doi: 10.1007/s11239-020-02374-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andrews N.J., Stowe J., Ramsay M.E., Miller E. Risk of venous thrombotic events and thrombocytopenia in sequential time periods after ChAdOx1 and BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccines: a national cohort study in England. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2022;13 doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simpson C.R., Shi T., Vasileiou E., et al. First-dose ChAdOx1 and BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccines and thrombocytopenic, thromboembolic and hemorrhagic events in Scotland. Nat. Med. 2021;27(7):1290–1297. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01408-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hippisley-Cox J., Patone M., Mei X.W., et al. Risk of thrombocytopenia and thromboembolism after covid-19 vaccination and SARS-CoV-2 positive testing: self-controlled case series study. BMJ. 2021;374 doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Medsafe New Zealand Data Sheet. Vaxzevria. Version 040422. 2021. https://www.medsafe.govt.nz/profs/Datasheet/c/Covid19VaccineAstraZenecainj.pdf Available from: Accessed Feburary 24 2022]

- 8.European Medicines Agency Jcvden (previously COVID-19 vaccine Janssen) : EPAR- Product Information. 2022. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/jcovden-previously-covid-19-vaccine-janssen-epar-product-information_en.pdf Available from: [Accessed June 17 2022]

- 9.Ministry of Health New Zealand COVID-19: Vaccines. 2022. https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/diseases-and-conditions/covid-19-novel-coronavirus/covid-19-vaccines Available from: Accessed January 24 2022]

- 10.Polack F.P., Thomas S.J., Kitchin N., et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;383(27):2603–2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abbattista M., Martinelli I., Peyvandi F. Comparison of adverse drug reactions among four COVID-19 vaccines in Europe using the EudraVigilance database: thrombosis at unusual sites. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2021;19(10):2554–2558. doi: 10.1111/jth.15493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hviid A., Hansen J.V., Thiesson E.M., Wohlfahrt J. Association of AZD1222 and BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccination with thromboembolic and thrombocytopenic events in frontline personnel: a retrospective cohort study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2022;175(4):541–546. doi: 10.7326/M21-2452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barda N., Dagan N., Ben-Shlomo Y., et al. Safety of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine in a nationwide setting. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021;385(12):1078–1090. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2110475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klein N.P., Lewis N., Goddard K., et al. Surveillance for adverse events after COVID-19 mRNA vaccination. JAMA. 2021;326(14):1390–1399. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.15072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Houghton D.E., Wysokinski W., Casanegra A.I., et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism after COVID-19 vaccination. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2022;20(7):1638–1644. doi: 10.1111/jth.15725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Medsafe COVID-19. Safety Monitoring. Overview of Vaccine Reports. Safety Report #43- 30 April 2022. 2022. https://www.medsafe.govt.nz/COVID-19/safety-report-43.asp Available from: Acessed 6 June 2022.]

- 17.Alhashim A., Hadhiah K. Extensive cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST) after the first dose of Pfizer-BioNTech BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine without thrombotic thrombocytopenia syndrome (TTS) in a healthy woman. Am. J. Case Reports. 2022;23:e934741–e934744. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.934744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tobaiqy M., MacLure K., Elkout H., Stewart D. Thrombotic adverse events reported for moderna, Pfizer and Oxford-AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccines: comparison of occurrence and clinical outcomes in the EudraVigilance database. Vaccines. 2021;9(11):1326. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9111326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prickett K.C., Habibi H., Carr P.A. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and acceptance in a cohort of diverse new zealanders. Lancet Reg. Health West Pac. 2021;14 doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2021.100241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.StatsNZ Taturanga Aotearoa. New Zealand's population reflects growing diversity. 2019. https://www.stats.govt.nz/news/new-zealands-population-reflects-growing-diversity Available from: [Accessed 5 April 2022]

- 21.Steyn N., Binny R.N., Hannah K., et al. medRxiv; 2021. Māori and Pacific People in New Zealand Have Higher Risk of Hospitalisation for COVID-19. p. 2020.12. 25.20248427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steyn N., Binny R.N., Hannah K., et al. Estimated inequities in COVID-19 infection fatality rates by ethnicity for aotearoa New Zealand. N. Z. Med. J. 2020;133(1521):28–39. doi: 10.1101/2020.04.20.20073437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Graham R., Masters-Awatere B. Experiences of Māori of aotearoa New Zealand's public health system: a systematic review of two decades of published qualitative research. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health. 2020;44(3):193–200. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Whitehead J., Scott N., Atatoa-Carr P., Lawrenson R. Will access to COVID-19 vaccine in aotearoa be equitable for priority populations? N. Z. Med. J. 2021;134(1535):25–34. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyab168.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marriott L., Sim D. Indicators of inequality for Maori and Pacific people. J. N. Z. Stud. 2015;20:24–50. 10.3316. [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Hallahan J., McNicholas A., Galloway Y., et al. Delivering a safe and effective strain-specific vaccine to control an epidemic of group B meningococcal disease. N. Z. Med. J. 2009:122. http://www.nzma.org.nz/journal/122-1291/3505/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paterson J., Schluter P., Percival T., Carter S. Immunisation of a cohort Pacific children living in New Zealand over the first 2 years of life. Vaccine. 2006;24(22):4883–4889. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pointon L., Howe A.S., Hobbs M., et al. Evidence of suboptimal maternal vaccination coverage in pregnant New Zealand women and increasing inequity over time: a nationwide retrospective cohort study. Vaccine. 2022;40(14):2150–2160. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.02.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baker M.G., Wilson N., Anglemyer A. Successful elimination of Covid-19 transmission in New Zealand. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;383(8) doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2025203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ministry of Health New Zealand COVID-19 Cases: Current Cases. 2022. https://www.health.govt.nz/covid-19-novel-coronavirus/covid-19-data-and-statistics/covid-19-current-cases Available from: [Accessed June 17 2022]

- 31.Whitaker H.J., Farrington C.P., Spiessens B., Musonda P. Tutorial in biostatistics: the self-controlled case series method. Stat. Med. 2006;25(10):1768–1797. doi: 10.1002/sim.2302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Farrington C. Relative incidence estimation from case series for vaccine safety evaluation. Biometrics. 1995;51(1):228–235. doi: 10.2307/2533328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ghebremichael-Weldeselassie Y., Jabagi M.J., Botton J., et al. A modified self-controlled case series method for event-dependent exposures and high event-related mortality, with application to COVID-19 vaccine safety. Stat. Med. 2022 doi: 10.1002/sim.9325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brighton Collaboration Safety Platform for Emergency VACcines (SPEAC). Priority List of Adverse Events of Special Interest: COVID-19. V2.0. 2020. https://brightoncollaboration.us/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/SPEAC_D2.3_V2.0_COVID-19_20200525_public.pdf Available from: Accessed 10 February 2022]

- 35.Ministry of Health New Zealand Health Statistics. National Minimum Dataset (hospital events) 2021. https://www.health.govt.nz/nz-health-statistics/national-collections-and-surveys/collections/national-minimum-dataset-hospital-events Available from: Accessed March, 2 2022]

- 36.Ministry of Health New Zealand NZ Health System. Guide to eligibility for publicly funded health services. 2022. https://www.health.govt.nz/new-zealand-health-system/eligibility-publicly-funded-health-services/guide-eligibility-publicly-funded-health-services Available from: [Accessed March, 2 2022]

- 37.Ministry of Health New Zealand COVID-19 Vaccines- Your Privacy- COVID Immunisation Register (CIR) privacy statement. 2021. https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/diseases-and-conditions/covid-19-novel-coronavirus/covid-19-vaccines/covid-19-vaccine-and-your-privacy/covid-immunisation-register-cir-privacy-statement Available from: Acessed 6 June 2022.]

- 38.COVID-19 GOVT NZ Time between doses of COVID-19 Vaccine extended- media release 12 Aug 2021. 2021. https://covid19.govt.nz/news-and-data/latest-news/time-between-doses-of-covid-19-vaccine-extended Available from: Acessed 6 June 2022.]

- 39.COVID-19 GOVT NZ Get your second dose. 2022. https://covid19.govt.nz/covid-19-vaccines/how-to-get-a-covid-19-vaccination/getting-your-second-dose Available from: [Accessed 11 March 2022]

- 40.COVID-19 GOVT NZ Latest news- Booster vaccine available from end of November – statement released 15 Nov 2021. 2021. https://covid19.govt.nz/news-and-data/latest-news/booster-vaccine-available-from-end-of-november Available from: Accessed [February 16, 2022]

- 41.Farrington C., Whitaker H. Semiparametric analysis of case series data. J. R. Stat. Soc.: Ser. C: Appl. Stat. 2006;55(5):553–594. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9876.2006.00554.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Salehi G., Sarraf P., Fatehi F. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis may follow a seasonal pattern. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2016;25(12):2838–2843. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2016.07.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gallerani M., Boari B., De Toma D., et al. Seasonal variation in the occurrence of deep vein thrombosis. Medical Science Monitor. 2004;10(5):CR191–CR196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lindqvist P., Epstein E., Olsson H. Does an active sun exposure habit lower the risk of venous thrombotic events? AD-lightful hypothesis. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2009;7(4):605–610. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Farrington C.P., Whitaker H.J., Hocine M.N. Case series analysis for censored, perturbed, or curtailed post-event exposures. Biostatistics. 2009;10(1):3–16. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxn013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Farrington P., Whitaker H., Weldeselassie Y.G. 2018. Self-controlled Case Series Studies:A Modelling Guide With R. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Remschmidt C., Wichmann O., Harder T. Frequency and impact of confounding by indication and healthy vaccinee bias in observational studies assessing influenza vaccine effectiveness: a systematic review. BMC Infect. Dis. 2015;15(1):1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-1154-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.StatsNZ Taturanga Aotearoa. Population. 2022. https://www.stats.govt.nz/topics/population Available from: [Accessed 5 April 2022]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not able to be made publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions outlined by New Zealand Legislation.