Abstract

Malignant rhabdoid tumor (MRT) is a highly aggressive pediatric malignancy with no effective therapy. Therefore, it is necessary to identify a target for the development of novel molecule-targeting therapeutic agents. In this study, we report the importance of the runt-related transcription factor 1 (RUNX1) and RUNX1–Baculoviral IAP (inhibitor of apoptosis) Repeat-Containing 5 (BIRC5/survivin) axis in the proliferation of MRT cells, as it can be used as an ideal target for anti-tumor strategies. The mechanism of this reaction can be explained by the interaction of RUNX1 with the RUNX1-binding DNA sequence located in the survivin promoter and its positive regulation. Specific knockdown of RUNX1 led to decreased expression of survivin, which subsequently suppressed the proliferation of MRT cells in vitro and in vivo. We also found that our novel RUNX inhibitor, Chb-M, which switches off RUNX1 using alkylating agent-conjugated pyrrole-imidazole polyamides designed to specifically bind to consensus RUNX-binding sequences (5′-TGTGGT-3′), inhibited survivin expression in vivo. Taken together, we identified a novel interaction between RUNX1 and survivin in MRT. Therefore the negative regulation of RUNX1 activity may be a novel strategy for MRT treatment.

Keywords: malignant rhabdoid tumor, polyamide, RUNX1, survivin

INTRODUCTION

Malignant rhabdoid tumors (MRTs) are rare and highly aggressive cancers that arise in various sites, including soft tissues, central nervous system, heart, thymus, liver, kidneys, colon, pelvis, uterus, and skin. MRT is more prevalent in infants and young children, and less than 10% of infants survive four years after diagnosis despite intensive multimodal therapy (Brennan et al., 2004; 2013; 2016; Tomlinson et al., 2005). Therefore, novel therapeutic approaches for MRT are required. MRT is driven by the loss of the SWI/SNF (switch/sucrose non-fermenting) related, matrix associated, actin dependent regulator of chromatin, subfamily b, member 1 (SMARCB1, also known as INI1 or BAF47). Most reports of new therapeutic strategies for MRT have suggested a relationship between SMARCB1 and the SWI/SNF complex, which is a multi-subunit chromatin-remodeling complex that contains SMARCB1 as a core component (Kuwahara et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2009; Weissmiller et al., 2019). The SWI/SNF complex interacts with the runt-related transcription factor (RUNX)-1, a member of the RUNX family (Bakshi et al., 2010). Thus, we hypothesized that RUNX1 is a potential therapeutic target for MRT. RUNX1 is a member of the RUNX family transcription factors (RUNX1, RUNX2, and RUNX3). They play essential roles in hematopoiesis, osteogenesis, neurogenesis, and as tumor suppressors in the development of leukemia (Ito et al., 2015; Sood et al., 2017). Meanwhile, we and other groups have found that RUNX1 is also strongly required for the development of some types of leukemia and malignant tumors, and inhibition of the RUNX cluster can be a new therapeutic strategy for acute myeloid leukemia (Ben-Ami et al., 2013; Goyama et al., 2013; Hyde et al., 2015; Janes, 2011; Kamikubo, 2018; Kamikubo et al., 2010; Morita et al., 2018). Furthermore, we have developed an original inhibitor, Chb-M’, which is a chlorambucil-conjugated pyrrole-imidazole (PI) polyamide designed to target the RUNX core DNA consensus sequence (5′-TGTGGT-3′) (Bando and Sugiyama, 2006; Minoshima et al., 2009; Morita et al., 2017a), and suppressed the proliferation of tumors in various cancer cell lines (Mitsuda et al., 2018; Morita et al., 2017a; 2017b; 2017c).

Baculoviral IAP (inhibitor of apoptosis) repeat containing 5 (BIRC5/survivin) is the smallest member of the inhibitor of apoptosis gene family (Kasof and Gomes, 2001; LaCasse et al., 1998; Rothe et al., 1995). Survivin protein is highly expressed during embryonic and fetal periods, but undetectable in normal terminally differentiated adult tissues (Kasof and Gomes, 2001). However, growing evidence shows that survivin is highly expressed and plays a central role in tumor cell proliferation in human cancers (Adida et al., 1998). Therefore, survivin can serve as a universal tumor antigen and has the potential to trigger immune effector responses; however, its role in MRT remains ambiguous. In this report, we reveal the importance of survivin in MRT and show that suppression of survivin via regulation of RUNX1 activity may be a novel strategy for MRT therapy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines

MP-MRT-AN, KP-MRT-RY, and KP-MRT-YM cells were established, as previously described (Katsumi et al., 2011; Kuroda et al., 2005; Misawa et al., 2004). Cells were maintained in the Roswell Park Memorial Institute-1640 medium containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin, as previously reported (Daifu et al., 2021). Cells were cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2.

Cell proliferation assay

Cell proliferation assays were performed as previously described (Mitsuda et al., 2018). To evaluate cell proliferation, 1 × 105 cells were seeded into a 6-well plate. After seeding, cells were treated with 3 μM doxycycline every other day. The cells were stained with trypan blue and counted using a Countess II Automated Cell Counter (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA).

Short hairpin RNA (shRNA) interference

shRNAs were designed as previously described (Mitsuda et al., 2018). In this study, specific shRNAs targeting human RUNX1 and survivin were designed and subcloned into pENTR4-H1tetOx1, CS-RfA-ETBsd, and CS-RfA-ETV vectors (RIKEN BRC). A non-targeting control shRNA was designed against luciferase (sh_Luc). The target sequences are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of target sequences used for short hairpin RNA (shRNA)-mediated knockdown experiments in this study

| Target sequences for shRNA knockdown experiments | 5’ → 3’ |

|---|---|

| sh_RUNX1 | AGCTTCACTCTGACCATCA |

| sh_Survivin | ACGTGTGCTGTCCGT |

| sh_Luc | CGTACGCGGAATACTTCGA |

Cell cycle analysis

Cell cycle analysis was conducted as previously described (Morita et al., 2017a). To assess the cell cycle, cells were fixed and permeabilized with fixation buffer and permeabilization wash buffer (BioLegend, USA), respectively. Then, the cells were incubated in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 3% heat-inactivated FBS, propidium iodide, and 100 mg/ml RNase A. Cells were then analyzed using flow cytometry (BD FACS Canto II flow cytometer; BD Biosciences, USA).

Apoptosis assay

Apoptotic cells were isolated using the Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit APC (eBioscience, USA), as previously reported (Morita et al., 2017a). First, 2 × 105 cells were washed in PBS, suspended in annexin-binding buffer, and mixed with 5 ml of annexin V. The reaction mixture was then incubated for 30 min. The cells were diluted, stained with propidium iodide, and analyzed using flow cytometry (BD FACS Canto II flow cytometer; BD Biosciences).

Immunoblotting

Immunoblotting was performed as previously described (Daifu et al., 2021; Morita et al., 2017a). Cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS and lysed in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 100 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1× protease inhibitor [Roche, Switzerland], and PhosSTOP [Roche]). Total cell extracts were separated via sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and electrotransferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Membranes were probed with the following primary antibodies: anti-RUNX1 (A-2; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA), anti-tripartite motif containing 24 (TRIM24) (A300-815A; Bethyl Laboratories, USA), anti-p53 (SC-126; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-Bcl-2-associated X (BAX) (N-20; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-cleaved caspase 9 (D2D4; Cell Signaling Technology, USA), anti-cleaved caspase 3 (5A1E; Cell Signaling Technology), anti-p21 (C19; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-survivin (GTX100052; GeneTex, USA), anti-poly(ADP ribose) polymerase (PARP) (46D11; Cell Signaling Technology), and anti-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (FL-335; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) antibodies. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (#7074) and anti-mouse IgG (#7076; Cell Signaling Technology) were used as secondary antibodies. Blots were visualized using Chemi-Lumi One Super (Nacalai Tesque, Japan) and ChemiDocTM XRS + Imager (Bio-Rad Laboratories, USA).

Human apoptosis array

A human apoptosis array was conducted using the Proteome Profiler Human Apoptosis Array Kit (ARY 009; R&D Systems, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were lysed in protease inhibitor-added Lysis Buffer 17. After the arrays were blocked with Array Buffer 1 for an hour, they were incubated with the protein lysate at 4°C overnight, followed by washing and incubation with Detection Antibody cocktail (biotinylated antibody cocktail) for 1 h at room temperature. After completing the above steps, arrays were detected using Chemi Reagent Mix, and signals were captured using the ChemiDocTM XRS + Imager (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Mice and xenograft mouse model

All animal studies were adequately conducted under the Regulation on Animal Experimentation at Kyoto University, based on the International Guiding Principles for Biomedical Research Involving Animals. All procedures were approved by the Kyoto University Animal Experimentation Committee (permit No. Med Kyo 14332).

NOD/Shi-scid, IL-2RγKO (NOG) mice were purchased from the Central Institute for Experimental Animals (Japan) and used at 8-12 weeks of age. Littermates were used as controls in all experiments. The mice were housed in sterile enclosures under specific pathogen-free conditions. These methods have been described in our previous study (Mitsuda et al., 2018).

Human MRT cell line-derived xenograft mouse models were created using NOG mice, as previously reported (Morita et al., 2017a). For MRT models, mice were transplanted with 1 × 106 cells/body of KP-MRT-YM cells via hypodermoclysis in the right dorsal flank. These mice were continuously administered oral doxycycline through drinking water seven days after the transplant (diluted in drinking water at 1 mg/ml in 3% sucrose).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry analysis was conducted on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sections, as previously reported (Mitsuda et al., 2018). The following antibodies were used in this study: anti-survivin (sc-17779; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-RUNX1 (A-2; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and anti-Ki67 (sc-23900; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) antibodies for xenograft experiments. Tissue section images were captured using a BZ-X700 all-in-one fluorescence microscope (Keyence, Japan).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (ChIP-qPCR)

ChIP assay was conducted using a SimpleChIPR Plus Enzymatic Chromatin IP Kit (Cell Signaling Technology), as previously reported (Mitsuda et al., 2018). The steps are summarized as follows: cells were cross-linked in 1% formaldehyde in PBS for 10 min at room temperature, followed by glycine quenching. The cell pellets were collected, lysed, and sonicated using a Q55 sonicator system (QSONICA, USA). The supernatant was diluted with the same sonication buffer and subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-RUNX1 antibody (ab23980; Abcam, UK) at 4°C overnight. The beads were then washed, and the DNA was reverse-cross-linked and purified. Following ChIP, DNA was quantified via qPCR using standard procedures in the 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, USA). The following primers were used for ChIP-qPCR: F, 5′-AGGCAGATCACTTGAGGTCAG-3′; and R, 5′-AAGCGATTCTCCTGCCTCAG-3′.

Expression plasmids

Expression plasmids were designed as described in our previous studies (Mitsuda et al., 2018; Morita et al., 2017a). The amplified cDNAs for human RUNX1 and survivin were inserted into the CSIV-TRE-RfA-UbC-KT expression vector. All PCR products were validated via DNA sequencing.

Production and transduction of lentivirus

HEK293T cells were transiently co-transfected with lentivirus vectors, such as psPAX2 and pMD2.G, using polyethyleneimine (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). Forty-eight hours after transfection, the viral supernatants were harvested and immediately used for infection. Transduced cells were sorted on an Aria III flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). These methods have been described in our previous study (Morita et al., 2017a).

Luciferase reporter assay

The presumptive promoter region of survivin (−1,500 to 0 bp of the transcription start site [TSS]) was cloned from the genomic DNA of KP-MRT-YM cells using the following primers: F, 5′-AGCCAATCAGCAGGACCCAGG-3′; and R, 5′-GGTCCCGCGATTCAAATCTGGC-3′, and then subcloned into the pGL4.20 (luc2/Puro) vector (Promega, USA). Both pGL4.20 inserted survivin promoter vector and pRL-CMV control vector (Toyobo B-Net, Japan) were co-transfected into HEK293T cells that stably express shRNA of sh_Luc or expression vector of RUNX1. Promoter activity was measured using the PicaGene Dual Sea Pansy Luminescence Kit (Toyobo B-Net) and ARVO X5 (Perkin Elmer, USA).

Measurement of the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50)

For IC50 evaluation, 1 × 105 cells were seeded in a 96-well plate. The cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of each compound in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and incubated for 48 h. Cell viability was assessed using the Cell Count Reagent SF (Nacalai Tesque) and Infinite 200 PRO multimode reader (TECAN). Percent inhibition curves were drawn and IC50 values of the indicated compounds were calculated based on the median-effect method.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using JMP (ver.17; JMP Statistical Discovery, USA). The statistical significance of differences between the control and experimental groups was determined using a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test. Statistical significance was set at P value < 0.05. The equality of variances in the two populations was assessed using the F-test. The results are presented as the mean ± SEM values obtained from three (in vitro assay) or six (in vivo assay) independent experiments.

Synthesis of PI polyamides

The synthesis of Chb-M’ was done as previously reported (Bando and Sugiyama, 2006; Morita et al., 2017a). Briefly, Py-Im polyamide supported by an oxime resin was formulated in a stepwise reaction using the Fmoc solid-phase protocol. The product with oxime resin was cleaved using N,N-dimethyl-1,3-propane diamine (1.0 ml) at 45°C for 3 h. The residue was dissolved in minimum amount of dichloromethane and washed with dimethyl ether to yield a 59.6 mg. To the crude compound (59.6 mg, 48.1 μmol), a solution of chlorambucil (32.6 mg, 107 μmol), benzotriazole-1-yl-oxy-tris-pyrrolidino-phosphonium hexafluorophosphate (101 mg, 195 μmol) and N,N-diisopropylethylamine (100 μl, 581 μmol) in N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF; 300 μl) was added. The reaction mixture was incubated for 1.5 h at room temperature, washed thrice with dimethyl ether and DMF, and dried in vacuo. The crude product was purified using reversed-phase flash column chromatography (water with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid/MeCN). After lyophilization, the product was obtained (30.2 mg, 19.8 μmol). Machine-assisted polyamide syntheses were performed using a PSSM-8 (Shimadzu, Japan) system with a computer-assisted operation. Flash column purifications were performed using CombiFlash Rf (Teledyne ISCO, USA) with a C18 RediSep Rf flash column. Electrospray ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry using the positive ionization mode and proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectra were recorded with a JEOL JNM ECA-600 spectrometer at 600 MHz and in parts per million (ppm) downfield relative to tetramethylsilane as an internal standard to verify the quality of the synthesized PI polyamides.

RESULTS

RUNX1 knockdown suppresses MRT cell proliferation and expression of survivin

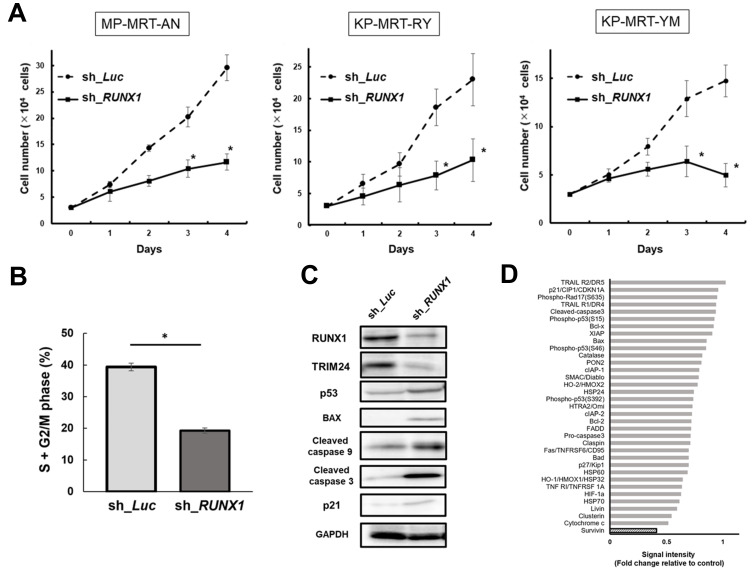

To examine the impact of depletion on RUNX1 MRT, in a previous study, we silenced RUNX1 through siRNAi; however, in this experiment, we silenced RUNX1 using several tetracycline-inducible shRNAs that targeted RUNX1 and lentivirally transduced them into MRT cells (MP-MRT-AN, KP-MRT-RY, KP-MRT-YM). Silencing RUNX1 inhibited the growth of MRT cells and induced cell cycle arrest. (Figs. 1A and 1B, Supplementary Fig. S1). To clarify the mechanism of tumor inhibition, we performed immunoblotting. As shown in Fig. 1C, the expression of TRIM24 decreased, but the expression of p53 dependent apoptosis-related proteins, such as BAX, cleaved caspase 9, and cleaved caspase 3, increased after the knockdown of RUNX1.

Fig. 1. Runt-related transcription factor 1 (RUNX1) knockdown suppresses the malignant rhabdoid tumor (MRT) cell proliferation and expression of baculoviral IAP (inhibitor of apoptosis) repeat containing 5 (BIRC5/survivin).

(A) Growth curves of MP-MRT-AN, KP-MRT-RY, and KP-MRT-YM cells lentivirally-transduced with control (sh_Luc) or RUNX1 shRNA (sh_RUNX1) in the presence of 3 μM doxycycline (n = 3). (B) RUNX1 depletion-mediated change in the number of cells with S + G2/M phase DNA content. KP-MRT-YM cells transduced with control (sh_Luc) or RUNX1 shRNAs (sh_RUNX1) were cultured in the presence of 3 mM of doxycycline. After 48 h treatment, cells were harvested and subjected to flow cytometric analysis (n = 3). Data are represented as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, by two-tailed Student’s t-test. (C) Immunoblotting of RUNX1, tripartite motif containing 24 (TRIM24), p53, apoptosis related proteins (Bcl-2-associated X [BAX], cleaved caspase 9, and cleaved caspase 3), p21, and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) in KP-MRT-YM cells lentivirally-transduced with control (sh_Luc) or RUNX1 shRNA (sh_RUNX1). Cells were incubated with 3 mM of doxycycline for 48 h before being lysed for protein extraction. (D) Relative densitometric quantification of human apoptosis array spots in RUNX1-depleted MP-MRT-AN cells compared to the control. Cells were treated with 3 μM doxycycline for 48 h and lysed for the human apoptosis array.

Next, to clarify the anti-tumor efficacy of silencing RUNX1 we performed an in vivo assay using a xenograft mouse model of human MRT cell lines that conditionally knocked down RUNX1 using shRNA. We monitored the size of tumors and found that RUNX1 depletion efficiently controlled MRT growth. We also confirmed the downregulation of RUNX1 in tumor samples resected from in vivo model mice (Supplementary Fig. S2). To support the clinical data and clarify the association between RUNX1 expression levels and prognosis in patients with MRT, we used MRT cohort data to conduct a survival analysis. The data were extracted from the TARGET Rhabdoid Tumor Subproject (https://ocg.cancer.gov/programs/target/projects/kidney-tumors), and the patients were classified as RUNX1 low (n = 34) or RUNX1 high (n = 23) based on their RUNX1 expression levels. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S3, the results of the survival analysis demonstrated that patients with high RUNX1 expression had a poorer prognosis than those with low RUNX1 expression. To reveal the impact of the molecular mechanisms of RUNX1 on the oncogenesis of MRT cells, we conducted a human apoptosis array in MP-MRT-AN cells transduced with shRNA targeting RUNX1 or control luciferase and measured the relative expression levels of 35 apoptosis-related proteins in these samples. As shown in Fig. 1D and Supplementary Fig. S4, RUNX1 knockdown markedly decreased survivin levels.

Therefore, we hypothesized that suppression of survivin leads to inhibition of MRT cell proliferation.

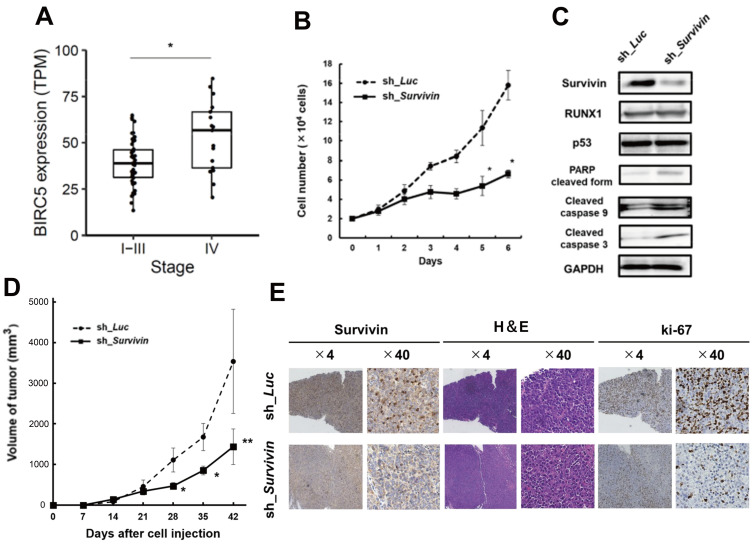

Survivin knockdown inhibits tumor growth of MRT cells in vitro and in vivo

To confirm our hypothesis, we first assessed whether survivin was correlated with the clinical data of MRT using clinical data. We extracted data in the above-mentioned manner to explore the association between BIRC5 (survivin) expression levels and the stages of cancer in patients with MRT. We classified the patients into stages I-III (n = 47) and IV (n = 17). As shown in Fig. 2A, the results demonstrated that BIRC5 gene expression levels were significantly higher in patients with stage IV MRT than in those with stage I- III MRT.

Fig. 2. Survivin knockdown inhibits the proliferation of MRT cells in vitro and in vivo.

(A) Boxplots of BIRC5 (survivin) in MRT stage I-III versus stage IV. The bottom and top of the box represent the first and third quartiles, respectively; the band inside the box represents the median. *P = 0.00663 by Mann–Whitney U test. TPM, transcripts per million. (B) Growth curves of MP-MRT-AN cells lentivirally-transduced with control (sh_Luc) or survivin shRNA (sh_Survivin) in the presence of 3 μM doxycycline (n = 3). (C) Immunoblotting of survivin, RUNX1, p53, apoptosis related proteins (poly(ADP ribose) polymerase [PARP], cleaved caspase 9, and cleaved caspase 3), and GAPDH in KP-MRT-YM cells with control (sh_Luc) or survivin shRNA (sh_Survivin). Cells were incubated with 3 mM of doxycycline for 48 h before being lysed for protein extraction. (D) Anti-tumor effects were examined by changes in the volume of xenograft tumor cells that knocked down survivin by shRNA (n = 6) or transduced control (n = 6). Data are represented as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, by two-tailed Student’s t-test. (E) Representative microscopic images of tumor histology. Results obtained from staining and immunohistochemical staining with anti-human survivin antibody, H&E, and ki-67 are shown (original magnification ×4 and ×40 [insets]).

Next, we examined cell proliferation using the shRNA-mediated survivin conditional knockdown system. As shown in Fig. 2B and Supplementary Fig. S1B, knockdown of survivin led to significant growth suppression compared with that in the control. Additionally, as shown in Fig. 2C, the immunoblot experiment indicated that survivin silencing induced apoptosis-related proteins, such as cleaved PARP, cleaved caspase 9, and cleaved caspase 3, but did not change the expression of RUNX1 and p53.

To clarify the anti-tumor efficacy of survivin silencing in vitro, we performed an in vivo assay using a xenograft mouse model of human MRT cell lines that conditionally knocked down survivin using shRNA. As shown in Fig. 2D and Supplementary Fig. S2C, we monitored the size of the tumors and revealed that survivin depletion efficiently inhibited the proliferation of MRT. Moreover, we confirmed that survivin was downregulated in in vivo samples resected from the tumor (Fig. 2E).

Therefore, these results suggest that RUNX1 regulates survivin expression in MRT cells.

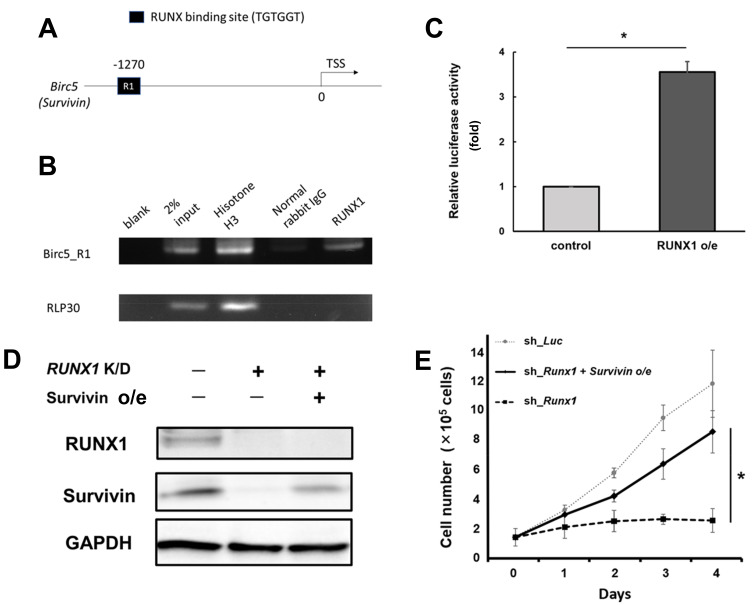

RUNX1 directly transactivates survivin expression

To establish whether survivin expression is regulated by RUNX1, we conducted a ChIP assay. As shown in Figs. 3A and 3B, we confirmed that RUNX1 binds to the promoter region of survivin (−1,500 to 0 bp of the TSS of survivin). In addition, the luciferase reporter assay demonstrated the activity of the survivin promoter, which showed a statistically significant increase in RUNX1 expression (P < 0.05, by two-tailed Student’s t-test) (Fig. 3C). These data suggested that RUNX1 directly controls survivin promoter expression. Additionally, as shown in Figs. 3D and 3E, additive expression of survivin restored the progression of RUNX1-knocked MRT cells against RUNX1-depletion-mediated growth inhibition. In summary, these results indicate that RUNX1 directly controls survivin expression in MRT cells.

Fig. 3. RUNX1 directly transactivates survivin expression.

(A) Proximal regulatory region (−1,500 to 0 bp relative to the transcription start site [TSS]) of Survivin. (B) Result of the chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis of KP-MRT-YM cells using anti-RUNX1, an isotype-matched control IgG, and anti-Histone H3 antibodies. ChIP products were amplified via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to determine the abundance of the indicated amplicons. (C) Luciferase reporter assay with survivin promoter. HEK293T cells were stably-transduced with the lentivirus expressing RUNX1 (RUNX1 o/e) or control, together with the reporter vector expressing luciferase gene under survivin promoter. Cells were incubated with 3 μM doxycycline for 48 h, and the luciferase activity was monitored with a luminometer. Result was normalized to that of the control sample (n = 3). (D) Immunoblotting of RUNX1, survivin, and GAPDH in non-depleted and RUNX1-depleted (RUNX1 K/D) MP-MRT-AN cells transduced with or without lentivirus expressing survivin (Survivin o/e). Cells were treated with 3 μM doxycycline for 48 h and lysed for immunoblotting. (E) Restoring survivin expression in RUNX1-depleted MP-ART-AN cells reverts RUNX1-depletion-mediated growth inhibition. The indicated cells were cultured in the presence of 3 μM doxycycline (n = 3). Data are represented as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, by two-tailed Student’s t-test.

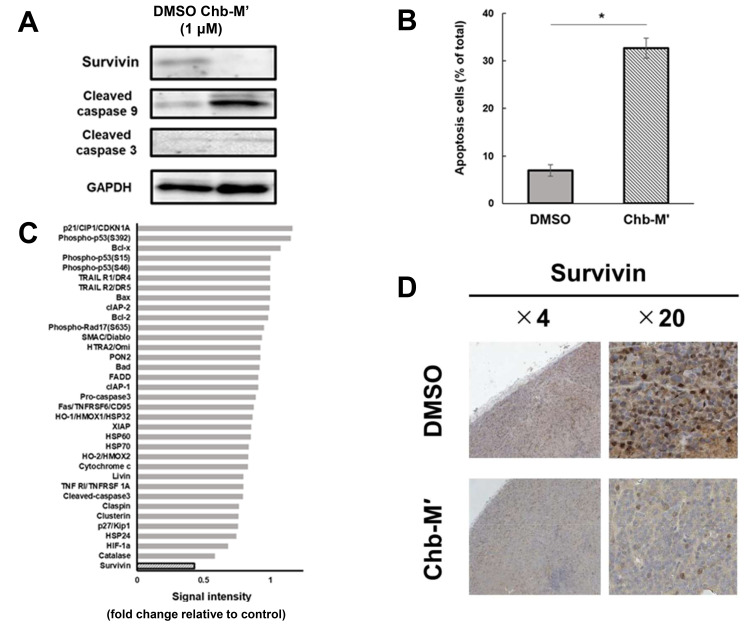

Chb-M’ suppresses survivin expression and apoptosis in MRT cells in vitro and in vivo

We previously reported that the RUNX inhibitor, Chb-M’, inhibits the proliferation of various tumor cell lines (Mitsuda et al., 2018; Morita et al., 2017a; 2017b; 2017c). Here, we investigated whether the inhibitory effects of Chb-M’ on MRT cells were mediated by the RUNX1–survivin axis. By immunoblotting the MRT cells after Chb-M addition, we found decreased expression of survivin and increased expression of apoptosis-related proteins (Fig. 4A). In the apoptosis assay, the number of apoptotic cells increased after Chb-M addition compared to that after DMSO addition (Fig. 4B). These data suggest that Chb-M’ can induce apoptotic cell death in the MRT cell line. Next, a human apoptosis array was conducted, and we found that the level of survivin was markedly decreased in the MRT cell line treated with Chb-M’ (Fig. 4C, Supplementary Fig. S5).

Fig. 4. Chb-M’ induces the suppression of survivin and apoptosis in MRT cells in vitro and in vivo.

(A) Downregulation of survivin in Chb-M’-treated KP-MRT-YM cells. Cells were treated with Chb-M’ or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; control). Forty-eight hours after treatment, cell lysates were prepared and subjected to immunoblotting. (B) Quantification of apoptotic cells. Apoptotic cells were defined as Annexin V+/7-AAD−cells (n = 3). Data are represented as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, by two-tailed Student’s t-test. (C) Relative densitometric quantification of human apoptosis array spots in Chb-M’-treated MRT cells compared to the control. Cells were treated with DMSO or 1 μM Chb-M’ for 48 h and lysed for human apoptosis array. (D) Representative microscopic images of tumor histology. These tumors were extracted from MRT model mice treated with Chb-M’ (n = 6) or DMSO as control (n = 6). Results obtained from staining and immunohistochemical staining with anti-human survivin antibody are shown (original magnification ×4 and ×20 [insets]).

In the in vivo assay using silenced survivin cells, the expression of survivin was suppressed in the in vivo samples treated with Chb-M’ (Fig. 4D).

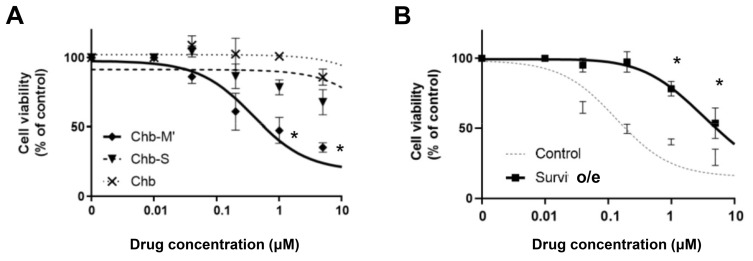

These results show that the efficacy of Chb-M’ in MRT cells is based on survivin downregulation via RUNX1 inhibition. To validate our hypothesis, we performed cell viability assays. The IC50 of Chb-M’ was lower, that is, it was more effective than chlorambucil (Chb) or Chb-S in MRT cells (Fig. 5A). Chb-S is a Chb-conjugated PI polyamide designed to target the 5′-WGGCCW-3′ sequence as a negative control for Chb-M. In comparison, survivin-overexpressing MRT cell lines showed resistance to the administration of Chb-M’ (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5. RUNX inhibition by Chb-M’ can be a novel therapeutic strategy for MRT.

(A) Dose-response curves of Chb, Chb-S, and Chb-M’ in KP-MRT-YM cells. Cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of pyrrole-imidazole (PI) polyamides or Chb. Forty-eight hours after treatment, cell viability was examined using a water-soluble tetrazolium salt (WST) assay (n = 3). (B) Dose-response curves of Chb-M’ in KP-MRT-YM cells transduced with either the lentivirus expressing survivin or control. The cells were simultaneously treated with 3 μM doxycycline and various concentrations of Chb-M. Forty-eight hours after treatment, cell viability was examined using a WST assay (n = 3). Data are represented as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, two-tailed Student’s t-test.

We also found that the anti-tumor effect of Chb-M’ is expected to be the same as that of YM155 (Nakahara et al., 2007), a novel small-molecule inhibitor of survivin, in MRT cell lines (Supplementary Fig. S6).

These data suggest that RUNX suppression through Chb-M can be a new therapeutic strategy for MRT.

DISCUSSION

We have previously shown that cluster regulation of RUNX (CROX) can be used as a therapeutic approach for various types of cancer, including leukemia, lung cancer, and gastric cancer (Mitsuda et al., 2018; Morita et al., 2017a; 2017b; 2017c). We also detected RUNX2 in human MRT cell lines. Since RUNX3 is usually considered to act as a tumor suppressor (Chang et al., 2010; Ito et al., 2008), we focused on the relationship between MRT and RUNX1.

First, we demonstrated that silencing RUNX1 drastically inhibited tumor growth in human MRT cell lines. We then indicated that survivin is downregulated in RUNX1-depleted MRT cells and hypothesized that suppression of survivin induces inhibition of MRT cell proliferation.

Survivin is a member of the IAP family. It plays an important role in the regulation of cell division and inhibition of apoptosis (Kasof and Gomes, 2001; LaCasse et al., 1998; Rothe et al., 1995). However, only a few studies have investigated the functions of IAPs in MRT or the relationship between RUNX and survivin (Lim et al., 2010).

Herein, we revealed that survivin-specific knockdown inhibits the proliferation of MRT cells in vitro and in vivo, and that RUNX1 directly transactivates survivin expression. These results indicate that the RUNX1–survivin axis may be a novel therapeutic target for MRT. This was further confirmed by our data that Chb-M efficacy in MRT cells is based on the suppression of survivin expression via regulation of RUNX1 inhibition.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated the novel role of the RUNX1–survivin axis in MRT. To validate the excellent in vivo tolerability and marked anti-tumor potency of Chb-M’ in mice, further investigation of this drug in clinical trials is needed to ensure the anti-tumor efficacy of the CROX strategy for the treatment of MRT.

Supplemental Materials

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Molecules and Cells website (www.molcells.org).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the Platform Project for Supporting Drug Discovery and Life Science Research (Basis for Supporting Innovative Drug Discovery and Life Science Research [BINDS]; 19am0101101j0003), Basic Science and Platform Technology Program for Innovative Biological Medicine from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED; 15am0301005h0002), Grant from the International Joint Usage/Research Center, the Institute of Medical Science, the University of Tokyo, and a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from KAKENHI (17H03597). We would like to thank Dr. H. Miyoshi (RIKEN BRC) for kindly providing the lentiviral vector encoding CSIV-TRE-RfA-UbC-KT for this study.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.M. performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. T.M., T.K., and M.N. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. K.U., H.H., H.K., T.D., A.I., E.H., K.F., S.T. (Saho Takasaki), S.T. (Sunao Tanaka), Y.M., H.M., M.H., T.R.K., T.N., Y.I., J.T., and S.A. participated in discussions and interpretation of data and results and commented on the research direction. Y.K., T.I., and H.H. established and characterized the human MRT cell lines. H.S. synthesized and designed the PI polyamides. Y.K. designed and initiated the study, supervised the research, and approved the final submission.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- Adida C., Crotty P.L., McGrath J., Berrebi D., Diebold J., Altieri D.C. Developmentally regulated expression of the novel cancer anti-apoptosis gene survivin in human and mouse differentiation. Am. J. Pathol. 1998;152:43–49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakshi R., Hassan M.Q., Pratap J., Lian J.B., Montecino M.A., van Wijnen A.J., Stein J.L., Imbalzano A.N., Stein G.S. The human SWI/SNF complex associates with RUNX1 to control transcription of hematopoietic target genes. J. Cell. Physiol. 2010;225:569–576. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bando T., Sugiyama H. Synthesis and biological properties of sequence-specific DNA-alkylating pyrrole−imidazole polyamides. Acc. Chem. Res. 2006;39:935–944. doi: 10.1021/ar030287f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ami O., Friedman D., Leshkowitz D., Goldenberg D., Orlovsky K., Pencovich N., Lotem J., Tanay A., Groner Y. Addiction of t(8;21) and inv(16) acute myeloid leukemia to native RUNX1. Cell Rep. 2013;4:1131–1143. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan B., De Salvo G.L., Orbach D., De Paoli A., Kelsey A., Mudry P., Francotte N., Van Noesel M., Bisogno G., Casanova M., et al. Outcome of extracranial malignant rhabdoid tumours in children registered in the European Paediatric Soft Tissue Sarcoma Study Group Non-Rhabdomyosarcoma Soft Tissue Sarcoma 2005 Study-EpSSG NRSTS 2005. Eur. J. Cancer. 2016;60:69–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan B., Stiller C., Bourdeaut F. Extracranial rhabdoid tumours: what we have learned so far and future directions. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:e329–e336. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70088-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan B.M., Foot A.B., Stiller C., Kelsey A., Vujanic G., Grundy R. United Kingdom Children's Cancer Study Group (UKCCSG), author Where to next with extracranial rhabdoid tumours in children. Eur. J. Cancer. 2004;40:624–626. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2003.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang T.L., Ito K., Ko T.K., Liu Q., Salto-Tellez M., Yeoh K.G., Fukamachi H., Ito Y. Claudin-1 has tumor suppressive activity and is a direct target of RUNX3 in gastric epithelial cells. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:255–265. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daifu T., Mikami M., Hiramatsu H., Iwai A., Umeda K., Noura M., Kubota H., Masuda T., Furuichi K., Takasaki S., et al. Suppression of malignant rhabdoid tumors through Chb-M'-mediated RUNX1 inhibition. Pediatr. Blood Cancer. 2021;68:e28789. doi: 10.1002/pbc.28789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyama S., Schibler J., Cunningham L., Zhang Y., Rao Y., Nishimoto N., Nakagawa M., Olsson A., Wunderlich M., Link K.A., et al. Transcription factor RUNX1 promotes survival of acute myeloid leukemia cells. J. Clin. Invest. 2013;123:3876–3888. doi: 10.1172/JCI68557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde R.K., Zhao L., Alemu L., Liu P.P. Runx1 is required for hematopoietic defects and leukemogenesis in Cbfb-MYH11 knock-in mice. Leukemia. 2015;29:1771–1778. doi: 10.1038/leu.2015.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K., Lim A.C., Salto-Tellez M., Motoda L., Osato M., Chuang L.S., Lee C.W., Voon D.C., Koo J.K., Wang H., et al. RUNX3 attenuates beta-catenin/T cell factors in intestinal tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:226–237. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito Y., Bae S.C., Chuang L.S. The RUNX family: developmental regulators in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2015;15:81–95. doi: 10.1038/nrc3877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janes K.A. RUNX1 and its understudied role in breast cancer. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:3461–3465. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.20.18029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamikubo Y. Genetic compensation of RUNX family transcription factors in leukemia. Cancer Sci. 2018;109:2358–2363. doi: 10.1111/cas.13664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamikubo Y., Zhao L., Wunderlich M., Corpora T., Hyde R.K., Paul T.A., Kundu M., Garrett L., Compton S., Huang G., et al. Accelerated leukemogenesis by truncated CBF beta-SMMHC defective in high-affinity binding with RUNX1. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:455–468. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasof G.M., Gomes B.C. Livin, a novel inhibitor of apoptosis protein family member. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:3238–3246. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003670200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsumi Y., Iehara T., Miyachi M., Yagyu S., Tsubai-Shimizu S., Kikuchi K., Tamura S., Kuwahara Y., Tsuchiya K., Kuroda H., et al. Sensitivity of malignant rhabdoid tumor cell lines to PD 0332991 is inversely correlated with p16 expression. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011;413:62–68. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.08.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda H., Moritake H., Sawada K., Kuwahara Y., Imoto I., Inazawa J., Sugimoto T. Establishment of a cell line from a malignant rhabdoid tumor of the liver lacking the function of two tumor suppressor genes, hSNF5/INI1 and p16. Cancer Genet. Cytogenet. 2005;158:172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2004.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwahara Y., Wei D., Durand J., Weissman B.E. SNF5 reexpression in malignant rhabdoid tumors regulates transcription of target genes by recruitment of SWI/SNF complexes and RNAPII to the transcription start site of their promoters. Mol. Cancer Res. 2013;11:251–260. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-12-0390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaCasse E.C., Baird S., Korneluk R.G., MacKenzie A.E. The inhibitors of apoptosis (IAPs) and their emerging role in cancer. Oncogene. 1998;17:3247–3259. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim M., Zhong C., Yang S., Bell A.M., Cohen M.B., Roy-Burman P. Runx2 regulates survivin expression in prostate cancer cells. Lab Invest. 2010;90:222–233. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2009.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minoshima M., Bando T., Shinohara K., Sugiyama H. Molecular design of sequence specific DNA alkylating agents. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. (Oxf.) ( 2009;53:69–70. doi: 10.1093/nass/nrp035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misawa A., Hosoi H., Imoto I., Iehara T., Sugimoto T., Inazawa J. Translocation (1;22)(p36;q11.2) with concurrent del(22)(q11.2) resulted in homozygous deletion of SNF5/INI1 in a newly established cell line derived from extrarenal rhabdoid tumor. J. Hum. Genet. 2004;49:586–589. doi: 10.1007/s10038-004-0191-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsuda Y., Morita K., Kashiwazaki G., Taniguchi J., Bando T., Obara M., Hirata M., Kataoka T.R., Muto M., Kaneda Y., et al. RUNX1 positively regulates the ErbB2/HER2 signaling pathway through modulating SOS1 expression in gastric cancer cells. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:6423. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-24969-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita K., Maeda S., Suzuki K., Kiyose H., Taniguchi J., Liu P.P., Sugiyama H., Adachi S., Kamikubo Y. Paradoxical enhancement of leukemogenesis in acute myeloid leukemia with moderately attenuated RUNX1 expressions. Blood Adv. 2017b;1:1440–1451. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2017007591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita K., Noura M., Tokushige C., Maeda S., Kiyose H., Kashiwazaki G., Taniguchi J., Bando T., Yoshida K., Ozaki T., et al. Autonomous feedback loop of RUNX1-p53-CBFB in acute myeloid leukemia cells. Sci. Rep. 2017c;7:16604. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-16799-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita K., Suzuki K., Maeda S., Matsuo A., Mitsuda Y., Tokushige C., Kashiwazaki G., Taniguchi J., Maeda R., Noura M., et al. Genetic regulation of the RUNX transcription factor family has antitumor effects. J. Clin. Invest. 2017a;127:2815–2828. doi: 10.1172/JCI91788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita K., Tokushige C., Maeda S., Kiyose H., Noura M., Iwai A., Yamada M., Kashiwazaki G., Taniguchi J., Bando T., et al. RUNX transcription factors potentially control E-selectin expression in the bone marrow vascular niche in mice. Blood Adv. 2018;2:509–515. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2017009324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakahara T., Kita A., Yamanaka K., Mori M., Amino N., Takeuchi M., Tominaga F., Hatakeyama S., Kinoyama I., Matsuhisa A., et al. YM155, a novel small-molecule survivin suppressant, induces regression of established human hormone-refractory prostate tumor xenografts. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8014–8021. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothe M., Pan M.G., Henzel W.J., Ayres T.M., Goeddel D.V. The TNFR2-TRAF signaling complex contains two novel proteins related to baculoviral inhibitor of apoptosis proteins. Cell. 1995;83:1243–1252. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90149-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sood R., Kamikubo Y., Liu P. Role of RUNX1 in hematological malignancies. Blood. 2017;129:2070–2082. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-10-687830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson G.E., Breslow N.E., Dome J., Guthrie K.A., Norkool P., Li S., Thomas P.R., Perlman E., Beckwith J.B., D'Angio G.J., et al. Rhabdoid tumor of the kidney in the National Wilms' Tumor Study: age at diagnosis as a prognostic factor. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005;23:7641–7645. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.8110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Sansam C.G., Thom C.S., Metzger D., Evans J.A., Nguyen P.T., Roberts C.W. Oncogenesis caused by loss of the SNF5 tumor suppressor is dependent on activity of BRG1, the ATPase of the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex. Cancer Res. 2009;69:8094–8101. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissmiller A.M., Wang J., Lorey S.L., Howard G.C., Martinez E., Liu Q., Tansey W.P. Inhibition of MYC by the SMARCB1 tumor suppressor. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:2014. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10022-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.